Highlights

-

•

The outbreak of COVID-19 significantly affected italy with severe health, social and economic consequences.

-

•

The strictness and timing of escalating and de-escalating containment and prevention measures played a major role on health and non-health outcomes.

-

•

Technological interventions are far from having any impact on the outcomes considered due to delayed implementation.

-

•

The production of evidence-based interventions is relevant for reducing uncertainty around the interventions, thereby maximising the resource and investment allocations.

-

•

Our findings are relevant not only for italy but for all countries worldwide.

Keywords: Health policy, Healthcare, Health technology, Pandemic

Abstract

Background

Italy was the first Western country to experience a major coronavirus outbreak and consequently faced large-scale health and socio-economic challenges. The Italian government enforced a wide set of homogeneous interventions nationally, despite the differing incidences of the virus throughout the country.

Objective

The paper aims to analyse the policies implemented by the government and their impact on health and non-health outcomes considering both scaling-up and scaling-down interventions.

Methods

To categorise the policy interventions, we rely on the comparative and conceptual framework developed by Moy et al. (2020). We investigate the impact of policies on the daily reported number of deaths, case fatality rate, confirmation rate, intensive care unit saturation, and financial and job market indicators across the three major geographical areas of Italy (North, Centre, and South). Qualitative and quantitative data are gathered from mixed sources: Italian national and regional institutions, National Health Research and international organisations. Our analysis contributes to the literature on the COVID-19 pandemic by comparing policy interventions and their outcomes.

Results

Our findings suggest that the strictness and timing of containment and prevention measures played a prominent role in tackling the pandemic, both from a health and economic perspective. Technological interventions played a marginal role due to the inadequacy of protocols and the delay of their implementation.

Conclusions

Future government interventions should be informed by evidence-based decision making to balance, the benefits arising from the timing and stringency of the interventions against the adverse social and economic cost, both in the short and long term.

Introduction

The novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) has been declared a global pandemic by the WHO, with 216 countries registering coronavirus outbreaks. Governments have put in place various interventions to respond to the rapid growth of infection and death [1] which have had considerable negative impacts on society. With no COVID-19 vaccine available, countries have been relying on non-pharmaceutical public health interventions [2]. Mitigation and containment strategies were targeted to flatten the contagion curve and reduce the rate of transmission, and to ensure the sustainability of health care systems in dealing with limited ICU capacity and equipment. The international experience suggests that technologies such as contact tracing, drones and robots have played a crucial role in the fight against the virus in some countries, however the experience is mixed and their overall effectiveness is still uncertain [3].

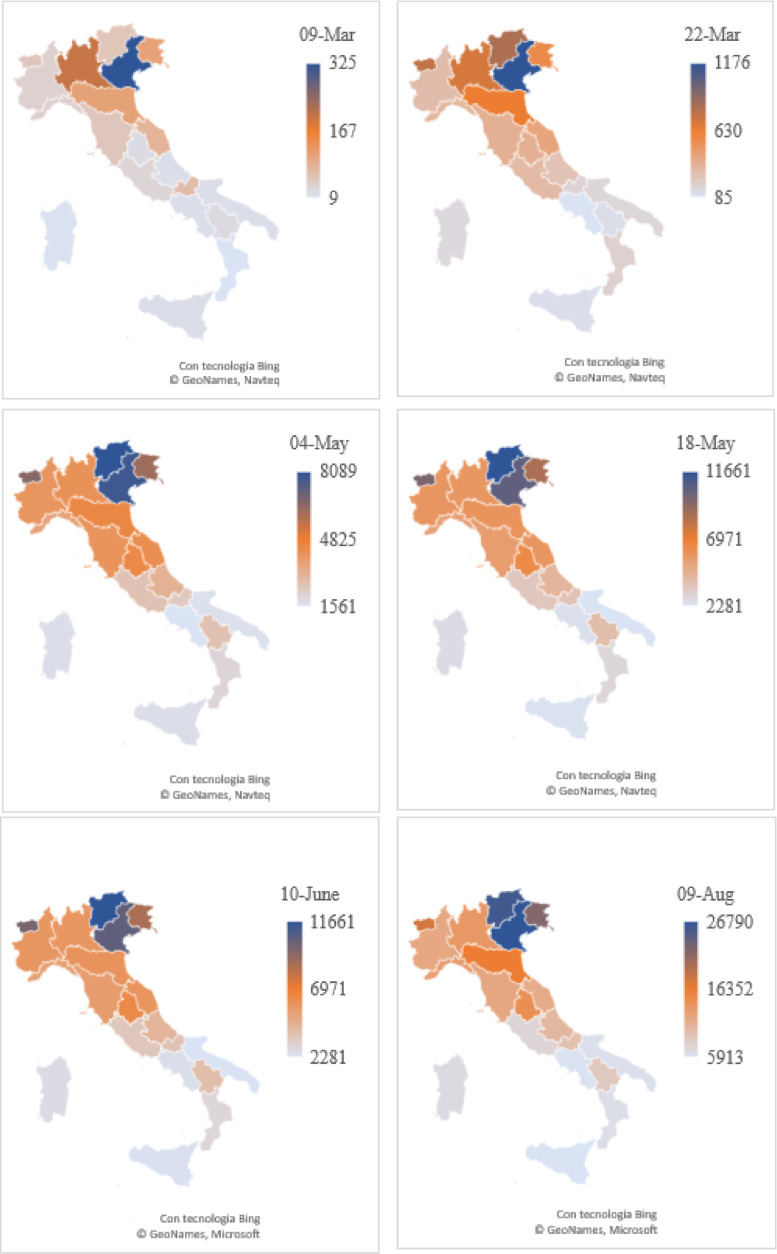

Italy was the first Western country to experience the COVID-19 emergency with a spiral of infections and deaths placing the country at the top of the international rankings, overtaking China on 19th March 2020. The COVID-19 burden has challenged the cost and sustainability of regional healthcare systems and the concomitant safety of healthcare professionals, requiring a + 3.6% GDP increase in public health expenditure compared to the previous year for hospital reorganisation, community infrastructure, health personnel recruiting and equipment supply [4]. The incidence of the virus has been particularly severe in Northern regions, moderate in Central regions and mild in the Southern regions of Italy [5]. The Italian government implemented a wide range of measures to balance the complex trade-offs between ethical, public health, legal and economic problems. In the early phase of the epidemic, the Italian government applied targeted measures to the most affected areas. As of 9th March 2020, the policy interventions were extended homogeneously to all the regions despite the varied severity of the spread. The national exit strategy plan announced at the end of April began on 4th May 2020 with the gradual relaxation of containment measures carried out in three different phases.

This paper aims to investigate and assess policy interventions implemented in Italy and the impact on health and non-health outcomes. The literature offers different measures providing a systematic cross-country tracking of COVID-19 policies [1], [6], [7], [8]. Our analysis considers a set of interventions with targeted objectives in the escalation and de-escalation phases across Italian regions from 22nd January 2020 to 9nd August 2020.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we present an overview of the health profile of the population and health care system of Italy. Section 3 presents the analysis of COVID-19 epidemiological trends at national and regional levels. In Section 4, we describe and analyse scaling-up and scaling-down policies implemented in Italy based on a comparative conceptual framework [8]. This section considers various interventions such as measures to contain the spread of the virus, policies for prevention and cure, interventions for economic stimulus, and the introduction of new health technology. Section 5 gives an overview of the response of the health care system. In Section 6, we discuss the long-term challenges and spillover effects arising from the pandemic and associated government interventions. The final section presents the implications of our results for policy and draws conclusions.

Country description

It is important to understand Italy's demographic and epidemiological features to recognise the factors associated with COVID-19. With a population of over 60 million and a surface area of over 300,000 km2, Italy is one of the largest and most populous countries in Europe. It is a highly developed country [9], with the eighth largest economy in the world. The government is a parliamentary republic, with a multi-level governance system across twenty administrative regions and 107 provinces and metropolitan cities.

The Italian Constitution recognises health as a fundamental individual and collective right and stipulates that care should be guaranteed to disadvantaged people [10], [11]. This is reflected in the Italian healthcare system (Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, or SSN), established in 1978 to provide universal coverage to all citizens, EU nationals, and legal residents. Further, emergency and basic services are provided for undocumented immigrants. Since 1993, health policies and constitutional reform have driven a decentralisation of the SSN [12]. The decentralisation is reflected in the financing, provision, and governance of the twenty regional health systems (see in Table A1 in the appendix). Regional models range from integrated model to a quasi-market in Lombardy [13]. Italian healthcare expenditure amounts to 8.8% of GDP, on par with OECD average [14]. The general budget is pooled nationally and distributed to the regions. In 2018, government compulsory healthcare expenditure per capita was USD 2545 (PPP), below the OECD average of USD 3994 [14]. Across regions the healthcare expenditure per capita is heterogeneous, ranging from USD 2483 in Campania to USD 3251 in Friuli Venezia Giulia [15]. National government financing accounted for 74.2% of total health spending in 2018, while out-of-pocket payments for 23.1% and voluntary schemes for the remaining 2.7% [14].

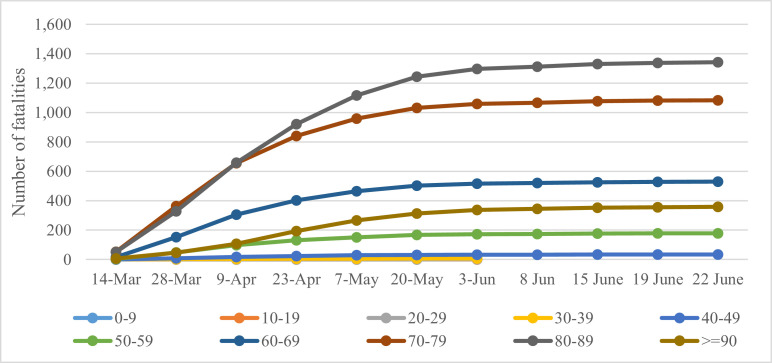

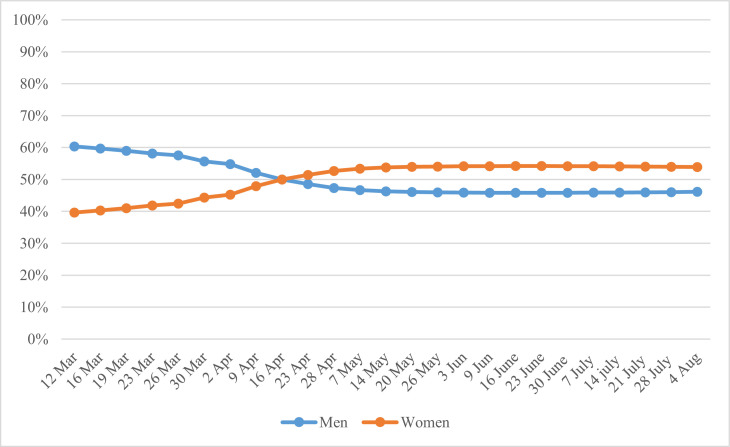

Arguably, having one of the best healthcare systems worldwide [16], [17], Italy has the second highest life expectancy at birth (83.6 years) amongst European countries, and the eighth highest in the world [18], [19]. As a result, its population (median age 46.3 years, 22% over 65 years) is the oldest in Europe and the second oldest in the world [20], [21]. Italy's longevity is associated with high morbidity rates, with 40% of the total population having a chronic condition, and nearly 21% being affected by multi-chronic conditions [18], [22]. Behavioural risk factors such as diet, tobacco smoking, high body mass index, alcohol consumption and low physical activity levels contribute to the Italian population burden of disease [23]. Empirical data confirms that age and morbidity are factors associated with COVID-19 mortality [24] (see Table A2 in the appendix). Amongst the deaths recorded in the sample period, 96.% are older than 60 years, and 96% had at least one underlying comorbidity/condition [25] (See Fig. A1 in the appendix). In the early stages of the pandemic, the incidence was higher amongst men, however, in April, the distribution evened out (see Fig. A2 in the appendix), limiting the role sex plays in the incidence of mortality arising from the diseases. As of 21st July 2020, 54% of confirmed cases were female (See Fig. A2 in the appendix). In considering the impact on life years lost arising from non-pharmaceutical interventions, we calculate the difference between the life expectancy of the Italian population (83.6 years) [19] and the median age of a death (80 years) pre-lockdown [26] of 3.6 years (end of the first quarter) and compared it to the difference between the life expectancy of the Italian population (83.6 years) and the median age of a death (82 years) post-lockdown of 1.6 years (at the end of the second quarter)(27). This result suggests that the years of life lost are diminishing due to the lockdown.

Fig. A1.

Deaths distribution by age corrected for the age, (14th March 2020–23rd June 2020).

data provided by ISS [27].

Fig. A2.

Incidence per gender, (12th March 2020–4th August 2020)

data provided by ISS [27].

COVID-19 epidemiological trends

In Italy, COVID-19 data is made available by different institutions at national and regional levels. The inconsistency of data between different administrative levels has been a major issue (see Table A3 in the Appendix). The Italian government started to publish data on 24th February 2020, with a reasonable degree of transparency, but only a moderate level of accessibility. Important data such as ICU survival rates, hospitalised patients’ outcomes, number and occupation of new beds introduced since the emergency are still missing (see Table A3 in the appendix).

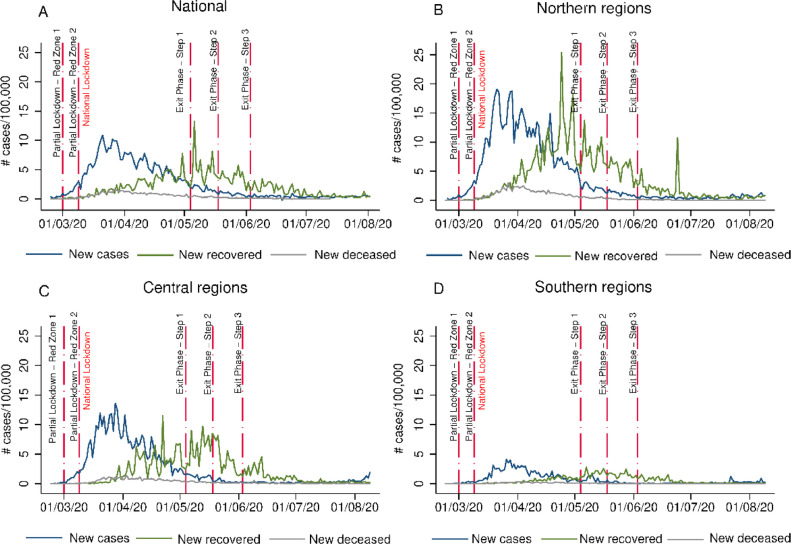

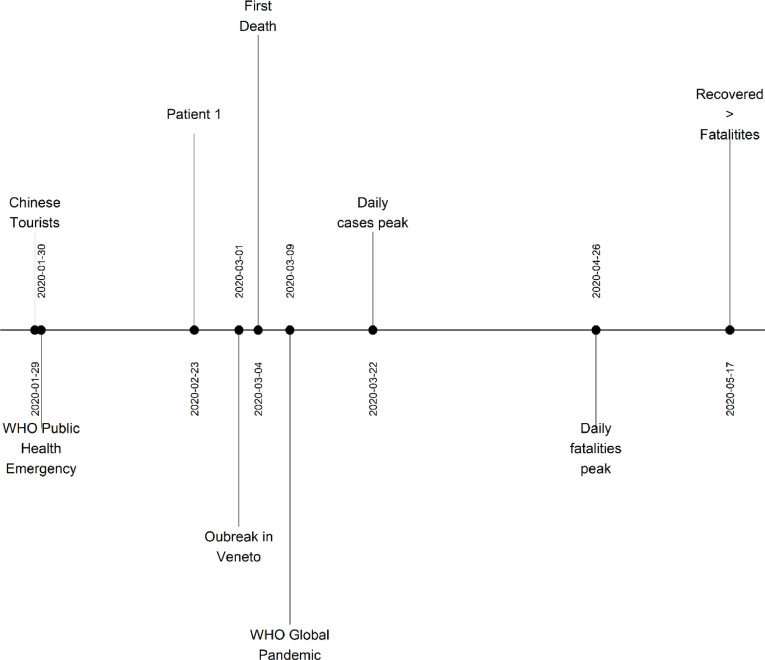

This section describes the epidemiological trend of COVID-19 throughout the country. COVID-19 appeared in Italy in late January 2020, when two Chinese tourists tested positive. One month later, patient 1 was detected in Lombardy. In the following days, Lombardy and Veneto became the two initial clusters of infection, experiencing a rapid escalation of cases. Increased surveillance, through contact tracing and testing of both symptomatic and asymptomatic persons exposed to positive cases, revealed that the virus had already been spreading in many municipalities of Southern Lombardy since January 2020 [28]. The contagious nature of COVID-19 caused cases to rapidly spread throughout the country [28]. Nationally, the peak of contagion occurred on 21st March 2020, with approximately 11 cases per 100,000 population (Fig. 1 ) and the peak of deaths was recorded a week later. On 26th April 2020, the number of daily new cases was exceeded by the number of recoveries, almost two months since national lockdown measures were implemented. On the same day, the government announced the national exit strategy plan to gradually lift the lockdown measures. The main epidemiological milestones of COVID-19 are reported in Roadmap 1 .

Fig. 1.

Distribution of epidemiological trend: daily variation of cases, recovered and deceases per 100,000 population at the national level and geographical area level (Northern, Central, Southern Regions).

Ministry of Health [35].

Roadmap 1.

Epidemiological milestones.

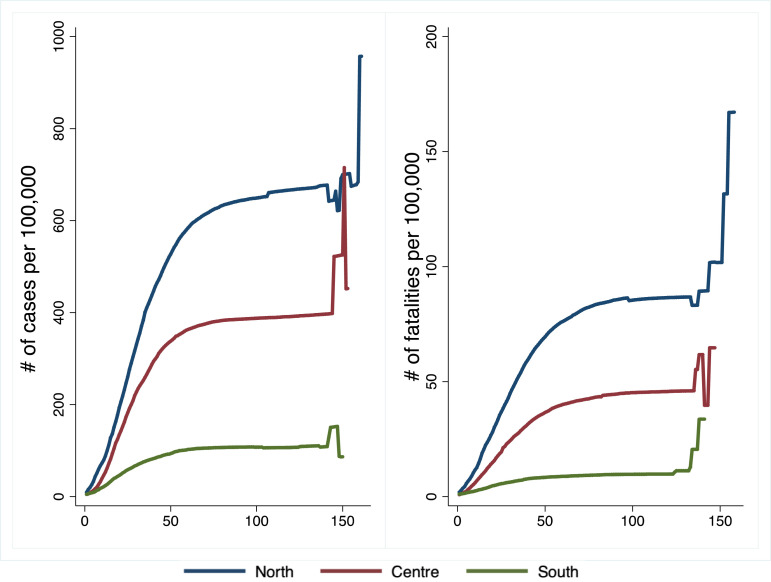

To compare the epidemiological figures at the regional level, we used the day each region's 50th case was confirmed as the start of that region's outbreak. Similarly, for the numbers of deaths, we used the day the 10th fatality was recorded. We arbitrary set these starting points to reduce potential bias of the testing strategy and deaths recording at the beginning of the outbreak. Fig. A3 in the appendix shows the distribution of COVID-19 cases and fatalities in Italy. Lombardy was the most affected region followed by Veneto, Emilia Romagna and Piemonte. To compensate for the likely underestimation of cases due to the classification method and the testing strategy, the Italian Bureau of Statistics (ISTAT) compared the excess deaths recorded in the first four months of 2020 with the average number of deaths across all causes in the first four months of 2015–2019 [29]. This empirical analysis covers a sample of Italian municipalities (87% in March, 92% in April and 93.1% in May). As a result, the integrated surveillance indicates that 54% of excess mortality registered in March, 82% in April and 8.5% in May 2020 can be attributed to COVID-19. The unexplained number of deaths might be attributed to three main causes: i) the higher mortality associated with the cases that were not tested; ii) indirect mortality in untested patients who died from organ dysfunctions possibly caused by COVID-19; and iii) indirect mortality due to strains on the healthcare system in the most affected areas [29].

Fig. A3.

Comparison of the epidemiological trends: 1) Panel A: cases from the first 50th; 2) Panel B: deaths from the first 10th (Northern, Central, Southern Regions), (24th February 2020–2nd August 2020).

Note: Northern regions: Piedmont, Aosta Valley, Lombardy, P.A. Bolzano, P.A. Trento, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Emilia-Romagna; Central regions: Tuscany, Marche, Umbria, Lazio, Abruzzo. Southern regions: Molise, Campania, Basilicata, Apulia, Calabria, Sicily, Sardinia. Source: Personal elaboration on Ministry of Health data.

data provided by Ministry of Health [35].

Policy and technology interventions: a conceptual framework

The Italian government declared a state of emergency on 31st January 2020. As the first Western country to experience a major outbreak of COVID-19, Italy was faced with escalating crisis in a period of extreme uncertainty. In the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine, the only measures to contain the spread of the virus are case isolation, contact tracing and lockdown measures. The decentralised nature of the Italian health care system combined with the heterogeneous epidemiological incidence at the regional level created the need for a diverse set of policies responsive to emerging patterns, rather than a one-size fits all approach. The policy interventions [8] are categorised as follows:

-

1

Policy interventions to contain the spread of the virus (behaviour, containment, mitigation) (see Roadmap 2 and Table A4 in the appendix);

-

2

Policy interventions for prevention and cure (treatments, health monitoring) (see Roadmap 3 and Table A5 in the appendix);

-

3

Technological interventions for testing, tracing and treating (see Roadmap 3 and Table A6 in the appendix)

-

4

Economic impact policy interventions (see Roadmap 4 and Table A7 in the appendix);

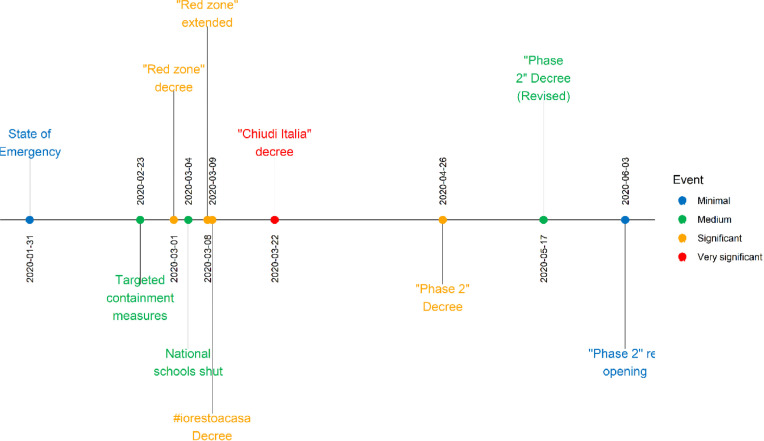

Roadmap 2.

Policy interventions to contain the spread of the virus.

Note: classification is based on Table A4 in the appendix. The significance gradient ranges from no restriction to enforced lockdown.

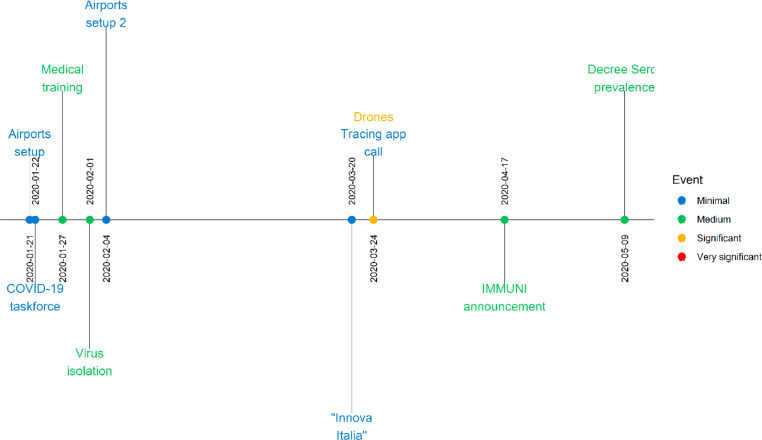

Roadmap 3.

Policies for prevention and care & technological interventions.

Note: classification is based on Table A5 & A6 in the appendix. For prevention and cure the significance gradient ranges form no interventions to all resources devoted to the public healthcare system. For technology the invasiveness gradient ranges from no interventions to centralised GPS contact tracing.

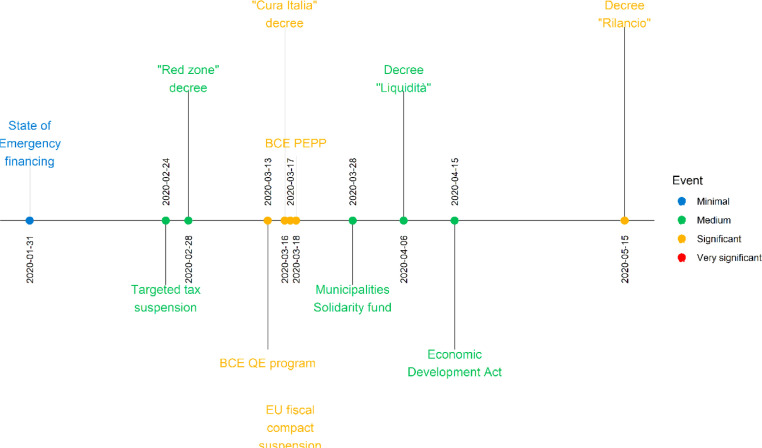

Roadmap 4.

Economic Policies.

Note: classification is based on Table A7 in the appendix. The significant gradient ranges from no changes to the status quo to strong public intervention in the financial and economic system.

Each policy categorisation has its own spectrum of escalating and de-escalating measures. The escalation implies the implementation of stricter or more invasive policy intervention, while the de-escalation implies the opposite. Scaling-up and scaling-down interventions are ranked on an ordinal scale gradient that ranges from 0 to 4, where policies are classified as none (0); minimum (1); mediuam (2); significant (3); very significant (4) based on their significance and invasiveness. Therefore, the upper extreme of the gradient gathers the implementation of all the other measures that belong to the lower levels of the spectrum. For instance, referring to the policy interventions to contain the spread of the virus, the significance gradient ranges from no restriction to enforced lockdown (Table A4 in the appendix). Looking at the technology interventions, the gradient measures the invasiveness ranging from no interventions to centralised GPS contact tracing (Table A6 in the appendix).

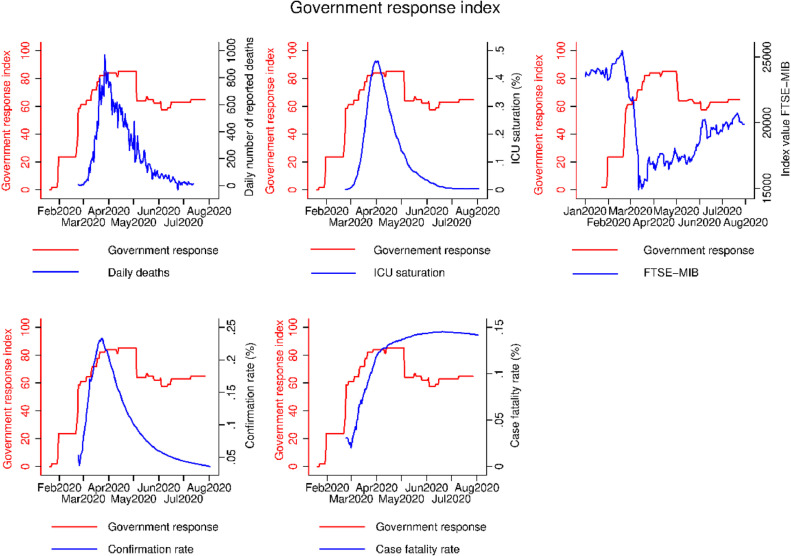

The comparative and conceptual framework [8] uses a systematic approach to categorise policies targeted to specific objectives. It is a tool to assess the impact of policies on different sets of health and non-health related outcomes. We focus our evaluation on the following outcomes: daily reported number of deaths; case fatality rate; confirmation rate; ICU saturation; FTSE MIB index value; and unemployment rate. Despite death data might be biased as mentioned above, daily reported number of deaths and case fatality rate are selected to represent epidemiological outcomes. Such outcomes are preferred to the confirmed cases indicators as the number of fatalities is less likely to be underestimated due to the country testing strategy [1]. Furthermore, the case fatality rate provides an estimate of the daily severity of the disease over time. ICU saturation reflects the response capacity of the healthcare system. The confirmation rate shows the testing strategy variation over time, ceteris paribus.1 The financial and economic indicators reflect the investors’ expectations of the Italian economy. The unemployment rate provides a measure on how the containment measures impact the job market and the productivity nationally. We break down the analysis at regional level for all of the outcomes except for the FTSE MIB Index Value and unemployment rate, which are at national level. The analysis does not include other relevant health and non-health outcomes due to data availability or inconsistency during the period considered (i.e. length of stay in hospital, readmission rate, ICU death rate and survival rate, public and private health care expenditure, public and private bed and personnel repurposing, public and private service provision, domestic violence, mental health demand). As a robustness check, the outcomes considered are compared with the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker that includes the response, stringency, containment and health and economic support indices [1].

We report an overview of the policy categorisation considering their major impact on some outcomes of interest. Amongst the four policy categories mentioned above, categories 2 and 3 are combined as there is an overlap between the preventive measures and the technology development and utilisation.

Policy interventions to contain the spread of the virus (behaviour, containment, and mitigation)

Prior to 9th March 2020, the major government interventions targeted the most affected regions, while minor containment policies were implemented in the rest of the country. With the Decree implemented on 9th March 2020, the government extended the lockdown and social distancing interventions homogeneously throughout the country. On 4th May 2020, the national exit strategy began, and from 17th May 2020, a change in strategy passed responsibility to individual regions under the overall supervision of the Ministry of Health.

Policy interventions for prevention and cure & technological interventions for testing, tracing and treating

In the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine, the introduction of health resources and technology plays a fundamental role in preventing the spread of the virus. Roadmap 3 reports the principal interventions adopted by the Italian government relative to the triple Ts strategy: testing, tracing and treatment. Technological solutions using geolocation tools have been used with success to control the spread of the virus in China, Singapore and South Korea [30]. The effectiveness of such technologies relies on wide adoption, however, one possible barrier to this is the perceived invasiveness and potential breaches of privacy [31], [32].

During the outbreak, the Ministry of Health issued national guidelines for testing. The testing criteria were updated at later stages (see Table A8 in the appendix), adopting WHO and European Commission recommendations. The strictness of the criteria reflected the necessity to ration the supply of swabs, reagents and laboratory capacity. Despite the national guidelines, a homogeneous testing strategy has not been consistently applied over time, across regions, neither in terms of number nor modality [5] (see Fig. A4 in the appendix). Amongst the three most affected regions, Lombardy ran fewer tests than Veneto and Emilia Romagna. As for the testing modality, Veneto and Emilia Romagna implemented a proactive strategy, treating positive patients with mild symptoms at home. Moreover, drive-through tests were introduced under the national surveillance program to monitor positive patients at the end of the quarantine [33], [34]. Lombardy took a more conservative approach, hospitalising patients with severe symptoms [35]. The testing strategy failed to protect the medical workforce, especially in the early phase of the pandemic. On 21st July 2020, the National Health Research Institute (ISS) reported 29,790 cases and 90 deaths amongst medical personnel [25]. Similarly, the surveillance strategy did not prevent the spread of COVID contagion amongst the elderly residents in home care facilities [36].

Fig. A4.

Number of tests per 100,000 inhabitants at regional level.

data provided by Ministry of Health [35].

In line with the European standards, the Italian government chose IMMUNI, a Bluetooth-based app, downloadable on a voluntary basis. It was released in four pilot regions (Abruzzo, Liguria, Marche and Puglia) on 8th June 2020. Drones and robots have been deployed to support public health initiatives. The operation of drones by local police to verify compliance with lockdown rules was short-lived due to a lack of guidelines for proper use. At the time of writing this paper, the use of robots is limited to telepresence, either allowing doctors to monitor patients remotely (thereby saving time and reducing the consumption of personal protective equipment (PPE)) or facilitating remote communications between hospitalised patients and their relatives. Despite the huge expansion of the digital health sector in Italy (with 7% increase, i.e. 1.39 billion Euro), digital health strategies are decentralised, resulting in inconsistent utilisation across different regions [37].

Economic impact policy interventions

The COVID-19 pandemic and the related lockdown measures have led to unprecedented economic costs around the world. The pandemic is a global shock that has affected the international economy, from financial markets where asset prices have decreased and volatility has increased characterising both the impact and future uncertainty involved with the pandemic [38], to the impacts on the supply-chain [39]. Decision-making necessary to prevent an economic collapse in such a context involves a trade-off between public health and economic prosperity [40], [41]. Using some micro and macro indicators, this section shows that Italy has suffered substantial economic losses. Roadmap 4 describes the principal economic interventions implemented by the Italian government and the European Central Bank.

In Italy, most business activities remained open even after the lockdown implemented on 9th March 2020. The non-essential activities were shut down on the 23rd March. Although there is a perceived trade-off between the health benefits and economic impact of the lockdown measures, the public health argument outweighed the economic one.

To prevent the economic collapse of the country, Italy has implemented several fiscal policies. The two most significant policies were the “Cura Italia” decree implemented on 16th March 2020 and the “Decreto Liquidità” implemented on the 8th April 2020. The “Cura Italia” brought an immediate tax boost of 16 billion Euro to help most affected sectors, strengthen the healthcare system and provide unemployment benefits. The “Cura Italia” decree was reinforced when the Council of Ministers approved the “Decreto Liquidità” (Decree-law of 8th April 2020, n. 23), allocating a total of 563 billion Euro to assist businesses by offering loan guarantees and a certain targeted tax relief. For instance, it provided 100 billion Euro as credit for small and medium enterprises, and injecting liquidity into the banking system. Furthermore, the Decree earmarks 200 billion Euro to support exporting enterprises located in Italy to access liquidity. The State and the Export credit agency cover respectively 10% and 90% of the guarantee to support enterprises financial obligations [42].

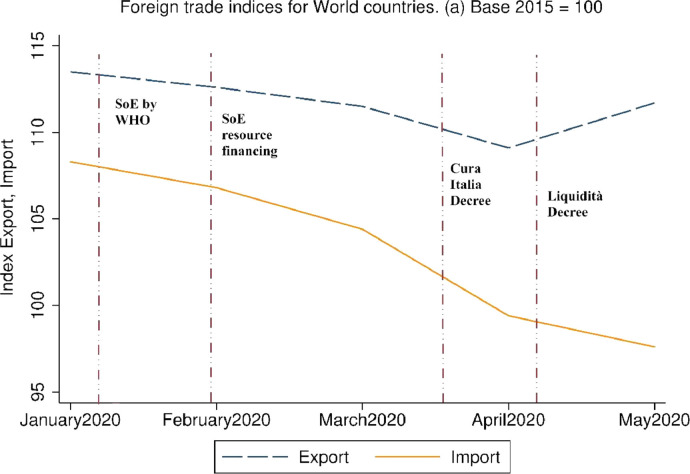

Despite the substantial fiscal stimulus, the country has experienced the biggest quarterly economic contraction since the 2008 financial crisis. According to the latest data provided by the Italian Bureau of Statistics (ISTAT) [43], the GDP in the first quarter of 2020 decreased by 5.4% in comparison to the first quarter of 2019. The overall GDP contraction estimated for 2020 is a contraction of 8.3% [44]. The crisis also impacted international trade flows. Fig. A5 in the appendix shows the monthly index of import and export in millions of Euro. In the quarter March-May 2020, despite the growth in May, the economic trend is conditioned by a sharp downturn of the previous months and is largely negative for both exports and imports (respectively −29.0% and −27.7% compared to the previous quarter December 2019-February 2020) [45]. According to the latest data provided by the Italian Bureau of Statistics (ISTAT) [45], in May 2020, exports record a marked decline on an annual basis (−30.4%), but with improvements compared to April (−41.5%), for both the non-EU area (−31.5%) and the EU (−29.4%). Compared to exports, the contraction in imports (−35.2%) is wider and summarizes the drops in purchases from both markets (−38.2% from non-EU countries, −32.9% from the EU area). In May 2020, the trade balance is estimated to increase by 199 million Euro (from +5385 million in May 2019 to +5584 million in May 2020). Net of energy products, the balance is +6603 million Euro (it was +8777 million in May 2019).

Fig. A5.

Monthly trade flows (import and export) in millions of Euro.

personal elaboration data provided by ISTAT [45].

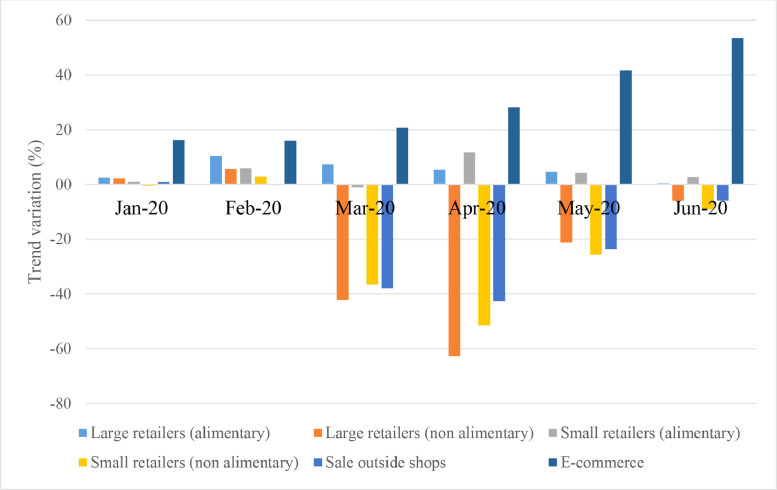

Considering the domestic market, retail sales recorded a collapse for non-alimentary goods, partly offset by a marked increase in e-commerce (see Fig. A6 in the appendix). Amongst the non-alimentary goods, the large negative variations correspond to the clothing and fur sector, followed by goods such as games, footwear and travel items. Pharmaceutical products also recorded a negative variation [46].The negative variation recorded in these sectors is likely to impact the economic fabric of the country, mainly composed by small and medium enterprises with limited investments in digitalisation directed toward to the online market.

Fig. A6.

Retail sales value trend variation compared to the previous year, by product sector.

data provided by ISTAT [46].

The perceived trade-off between public health benefits and the economic impact seemed to cover a central role in the exit phase as well. Until the 26th April 2020, the government imposed a homogenous exit strategy. As the number of cases decreased, regional governors put pressure on central government to relax some restrictions on economic activities. After 17th May 2020, the government's policy changed, leaving the exit strategy to be decided by each region. This choice implied a heterogenous re-opening of economic activities, which helped small and medium scale companies to re-start their businesses. After the lockdown, with the de-escalation measures, the government faced a crucial phase in terms of economic recovery. To invert the negative economic trend, the Italian government announced a massive fiscal and monetary stimulus on 16th May 2020. The decree “Rilancio” allocated around 155 billion Euro in five main areas with the aim of reorganising the hospital network to deal with COVID-19 emergency. Additionally, it guaranteed liquidity and support for Italian companies, aiding their stability during the emergency period and encouraging their revival at the time of recovery.

Health care system policy response

This section describes the policy implemented by the government to cope with the limited capacity of the health care system and the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. The central government is responsible for public health interventions; however, the decentralisation of the Italian healthcare system hindered the implementation of a homogeneous strategy. Regional health care systems differ widely in terms of hospital organisation (public versus private), equipment (number of beds etc.) and medical workforce [15].

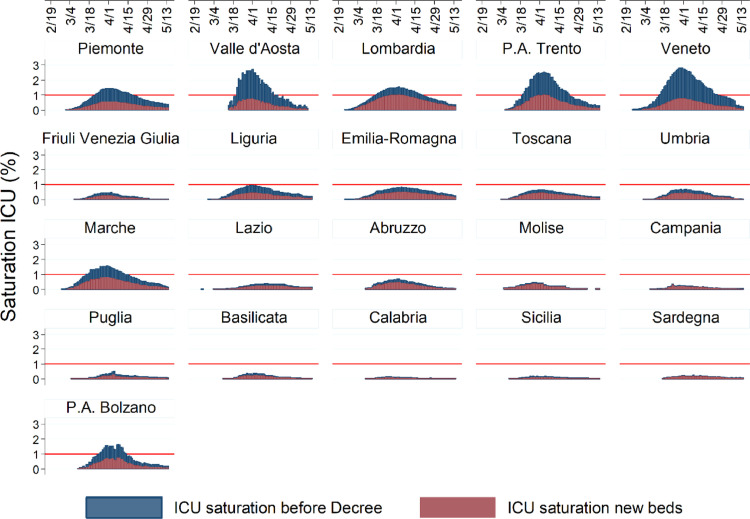

Following a decree implemented on 1st February 2020, the government facilitated the urgent increase of hospital beds in all regions by 50% in ICU and 100% in pulmonology and infectious disease wards. The measure entailed the immediate redistribution of hospitalised patients to accredited private structures to ease the pressure on the public system. The National Health System is composed of 80% public and 20% private beds, with substantial regional variations, ranging from 21.2% of public beds in Lombardy to 97.9% in Basilicata [15]. Increasing the number of ICU beds appears to have largely prevented saturation, except for Lombardy, which experienced an overloading of the system from 1st April 2020 (see Fig. A7 in the appendix). The available data does not give further information on patient outcomes. Patients’ length of stay, discharge, re-admission and mortality rate data are necessary to fully evaluate the healthcare system performance and the health policies implemented by the government [47].

Fig. A7.

Comparison of the ICU beds saturation rate with the capacity before and after the COVID-19.

Note: the red line coincides with the total saturation of the ICU capacity (100%) in the region considered. The x-axis reports the saturation rate 1 = 100%; 2 = 200%; 3 = 300%.

personal elaboration of data provided by Minsitero della Salute and Protezione Civile [49].

The overall standard national health budget increase for 2020 amounts to 1.4 billion Euro with a Decree of 17th March [4]. As part of this budget increase, the government spent 356 million Euro to implement the “Aid Distribution System”, distributing disposable and durable medical materials to each region [28]. The most common disposable materials distributed were masks (90%), gloves (4%), and diagnostic kits (2%). Durables materials included glasses (89%) and thermometers (3%). Veneto received the highest amount of materials and Molise the least. Between 24th March and 19th April 2020, the government also distributed 4532 ventilators, of which 15% went to Lombardy and 13% to Emilia Romagna. Following a decree implemented on 9th March 2020, the government committed 660 million Euro to hire 20,000 medical personnel on six-month contracts. Regions autonomously managed this hiring process, making it hard to access the relevant data [28]. On 19th May, “Decreto Rilancio” allocates 1500 million Euro to National Emergency fund and 2723 million Euro to strengthen emergency departments and community care [4].

Policy stringency and outcomes

This section has two aims. Firstly, we test whether the escalation and de-escalation stringency measures to contain the spread of the virus were justified by the underlying epidemiological trend for all the regions, using the t-test analysis. Our goal is to test whether differences in means of scaling-up and scaling-down policies are statistically significant. The daily death trend is chosen as the indication of the epidemiological trend. Secondly, we describe through a graphical analysis how the health and non-health outcomes were impacted by the policies presented in the conceptual framework. The graphical analysis aims at evaluating if differences in the levels of the policies gradient have had a detectable impact on given outcomes across different areas of the country and may be assessed over different lags of time.2

In the absence of a counterfactual scenario, we run a t-test analysis on the mean of the daily number of deaths for each region throughout the period of each single policy (see Table 2). The analysis defines whether the difference in the daily number of deaths between each containment policies implemented in the escalation and de-escalation phase is statistically significant to justify the implementation of a more or less stringent policy. Despite the death trend might be influenced by other policy interventions (such as increase of the ICU capacity and more effective preventive method), it still is more reliable compared to other epidemiological measures. The analysis covers the period 24th February to 9th August 2020. A value between 0 (no intervention) and 4 (very significant intervention) is assigned to each policy to represent its strictness (see Table 1 ). The policy classifications of Lombardy, Emilia Romagna and Veneto are displayed in three separate columns since targeted lockdown measurers were implemented before the national lockdown (see Table 2 ). Overall, the escalation measures were found to be justified by the underlying death trend. Considering the very significant intervention implemented the 22nd March in the escalation phase, the positive difference in the average daily number of deaths is significant in all the regions but Umbria and Molise (p <0.05). Applying the same rationale to the difference between the first scaling down intervention of the 4th May 2020, the observed variable is negative and statistically significant (p>0.05) for all the regions but Lazio and Campania. However, the coefficient for Lazio becomes statistically significant comparing the scaling down policy of 3rd June 2020 and the previous de-escalating measure. For all the other regions with exception of Aosta Valley, Umbria, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata and Calabria the mean difference is not statistically significant (p <0.05), comparing the last two scaling down measures. This suggests that minimal preventive measures should still be in place after the lockdown release until the number of deaths ceases.

Table 2.

Mean comparison of daily reported deaths throughout the period of each single policy (two-sample t-test with unequal variances).

| Escalation | De-escalation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 2 vs 1 | 3 vs 2 | 3 vs 2 | 4 vs 3 | 3exit vs 4 | 2exit vs 3exit | 1 exit vs 2 exit |

| (Italy) | (Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna) | (Italy) | (Italy) | Italy | |||

| Piedmont | Diff=1 *95% t = 2.23 |

Diff=16.92 *95% t = 5.88 |

Diff=49.84 *95% t = 10.67 |

Diff=−33.78 *95% t=−7.33 |

Diff=−16.94 *95% t=−4.47 |

Diff= −13.0 *95% t= −4.8 |

|

| Aosta Valley | Diff=0.62 *95% t = 2.55 |

Diff=2.43 *95% t = 4.98 |

Diff=−2.73 *95% t=−6.17 |

Diff=−0.25 95% t=−1.71 |

Diff= −0.01 95% t= −0.14 |

||

| Lombardy | Diff=4.9 *95% t = 2.57 |

Diff=163.98 *95% t = 4.97 |

Diff=163.98 *95% t = 4.97 |

Diff=90.08 *95% t = 2.38 |

Diff=−165.20 *95% t=−7.26 |

Diff=−53.0 *95% t=−3.78 |

Diff= −29.74 *95% t= −5.40 |

| P.A. Trento | Diff=2.15 95% t = 1.86 |

Diff=7.17 *95% t = 5.13 |

Diff=49.84 *95% t = 10.67 |

Diff=−1.25 *95% t= −3.16 |

Diff= −0.53 *95% t= −2.53 |

||

| P.A. Bolzano | Diff=1.53 *95% t = 3.83 |

Diff=4.53 *95% t = 4.37 |

Diff=−5.37 *95% t=−5.29 |

Diff=−0.63 95% t= −1.90 |

Diff= −0.02 *95% t= −0.41 |

||

| Veneto | Diff=0.2 95% t = 1.5 |

Diff=7.74 *95% t = 5.57 |

Diff=7.74 *95% t = 5.57 |

Diff=23.92 *95% t = 11.14 |

Diff=−11.32 *95% t=−4.16 |

Diff=−12.42 *95% t=−5.13 |

Diff= −5.59 *95% t= −4.88 |

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | Diff=0.2 95% t = 1.00 |

Diff=2.95 *95% t = 13.78 |

Diff=2.77 *95% t = 3.31 |

Diff=−4.23 *95% t=−7.42 |

Diff=−0.69 95% t=−1.73 |

Diff= −0.85 *95% t= −3.66 |

|

| Liguria | Diff=0.97 *95% t = 2.16 |

Diff=10.23 *95% t = 3.50 |

Diff=13.35 *95% t = 4.17 |

Diff=−14.04 *95% t=−8.93 |

Diff=−3.36 *95% t= −3.33 |

Diff= −5.55 *95% t= −7.37 |

|

| Emilia Romagna | Diff=1.8 *95% t = 2.47 |

Diff=36.92 *95% t = 5.21 |

Diff=36.92 *95% t = 17.36 |

Diff=29.35 *95% t = 3.75 |

Diff=43.61 *95% t=−11.0 |

Diff=−14.10 *95% t= −6.48 |

Diff= −7.81 *95% t= −9.73 |

| Tuscany | Diff=5.53 *95% t = 2.70 |

Diff=13.07 *95% t = 5.8 |

Diff=−10.37 *95% t = 7.10 |

Diff= −3.87 *95% t= −3.27 |

Diff =−3.1 *95% t= −6.39 |

||

| Umbria | Diff=0.76 95% t = 1.81 |

Diff=0.58 95% t = 1.83 |

Diff=−0.96 *95% t=−3.19 |

Diff= −0.21 95% t= −1.02 |

Diff= −0.11 95% t= −1.10 |

||

| Marche | Diff=0.93 *95% t = 2.09 |

Diff=10.30 *95% t = 4.76 |

Diff=6.67 *95% t = 2.42 |

Diff=−13.75 *95% t = 7.61 |

Diff= −3.28 *95% t= −6.84 |

Diff= −0.82 *95% t= −3.25 |

|

| Lazio | Diff=0.6 95% t = 1.50 |

Diff=3.01 *95% t = 3.72 |

Diff=7.04 *95% t = 5.84 |

Diff=−2.43 95% t=−1.41 |

Diff=- 0.95 95% t= −0.61 |

Diff= −5.35 *95% t= −5.89 |

|

| Abruzzo | Diff1.69 *95% t = 3.03 |

Diff=5.48 *95% t = 7.16 |

Diff=−3.08 *95% t=−4.33 |

Diff= −2.31 *95% t= −3.78 |

Diff= −0.79 95% t= −1.21 |

||

| Molise | Diff=0.54 *95% T = 2.00 |

Diff=−0.19 95% t=−0.67 |

Diff=−0.35 *95% t=−4.32 |

Diff=0.02 95% t = 1.00 |

|||

| Campania | Diff=1.69 *95% t = 2.38 |

Diff=6.26 *95% t = 5.93 |

Diff=−5.49 95% t=−0.59 |

Diff= −1.34 95% t= −1.95 |

Diff= −0.78 *95% t= −2.55 |

||

| Apulia | Diff=0.6 *95% t = 2.45 |

Diff=1.4 95% t = 1.89 |

Diff=6.53 *95% t = 7.18 |

Diff=−6.19 *95% t=−6.21 |

Diff= −0.35 95% t= −0.50 |

Diff= −1.92 *95% T=−3.89 |

|

| Basilicata | Diff=0.58 *95% t = 5.21 |

Diff=−0.43 *95% t=−2.81 |

Diff= −0.15 95% t= −1.47 |

Diff=0.02 95% t = 1.00 |

|||

| Calabria | Diff=0.38 *95% t = 2.13 |

Diff=1.57 *95% t = 4.75 |

Diff=−1.41 *95% t=−4.04 |

Diff= −0.42 95% t= −1.83 |

Diff= −0.11 95% t=−1.46 |

||

| Sicily | Diff=0.46 *95% t = 2.14 |

Diff=5.03 *95% t = 9.36 |

Diff=−3.72 *95% t=−6.21 |

Diff=- 1.18 *95% t= −3.15 |

Diff=−0.45 *95% t= −2.9 |

||

| Sardinia | Diff=0.31 95% t = 1.48 |

Diff=2.37 *95% t = 6.01 |

Diff=−2.21 *95% t=−4.34 |

Diff=- −0.11 95% t= −0.26 |

Diff= −0.28 *95% t= −2.32 |

||

Note:.

= p<0.05. Empty cells are reported for those Regions with no cases between the interventions.

Table 1.

Classification of policies’ degree.

| Date | Degree | Definition | Italy | Lombardy | Veneto | Emilia-Romagna |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22/01/2020 | Minimal (1) | Prime Minister Conte declare "State of Emergency for 6 months" | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 23/02/2020 | Medium (2) | Decree: containment measures to be applied in affected areas of Lombardy and Veneto for positive cases, close/traced contacts, symptomatic patients | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 23/02/2020 | Medium (2) | Schools and Universities shut down in Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 01/03/2020 | Significant (3) | “Red zone” decree: the Italian government lockdown some municipalities of Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 04/03/2020 | Medium (2) | All Italian schools and University shut down until the 3rd April | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 08/03/2020 | Significant (3) | The Italian government extends the area of the "Red zone" decree to the Northern municipalities and the whole Lombardy | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 09/03/2020 | Significant (3) | Decree #iorestoacasa: total shut down, free movement limitations, no possibility to overcome cities borders. | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 22/03/2020 | Very Significant (4) | Decree “Chiudi Italia: People cannot overcome the municipalities borders with public/private transports. Lockdown extended for non-essential production activities. | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 26/04/2020 | Very Significant (4) | "Exit strategy" Decree- starting from the 4th May. Three steps phases: 1) 4 May; 2) 18 May; 3) 1 June | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 04,705/2020 | Significant (3) | Starting of Phase 2, step 1: some restrictions are eased. People can visit close relatives | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 17/05/2020 | Medium (2) | New “phase 2″ decree: from the 18th May, the reopening strategy is left to regions. The government can impose the lockdown if the epidemiological curve and the rate of transmission overcomes the threshold imposed by the Ministry of Health. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 03/06/20 | Minimal (1) | Movement between regions is allowed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

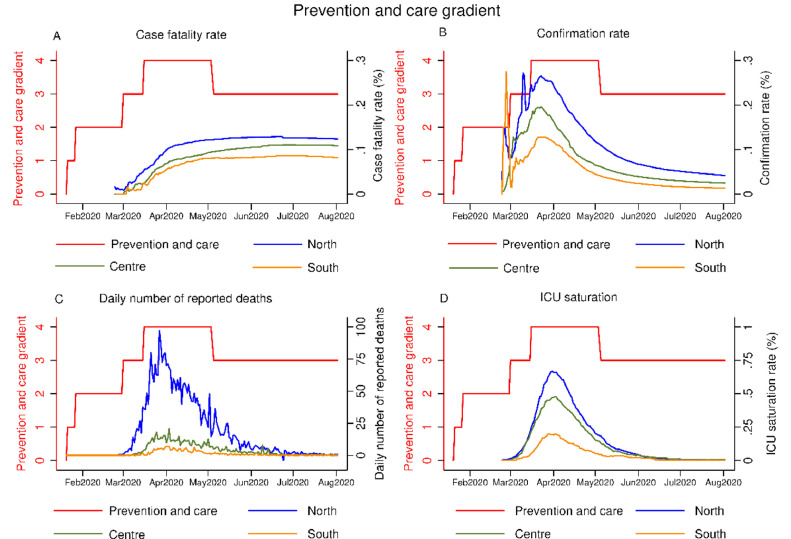

The Italian government declared the state of emergency on 31st January 2020, after the WHO announced COVID-19 as a public health emergency. However, the allocation of financial resources (5 billion Euro) was insufficient to build an effective and geographically homogeneous surveillance system before the detection of patient 1. Alongside, the less stringent policy interventions for prevention and care might have not been sufficient to counteract the increase in the daily number of deaths and the ICU saturation rate in early March, especially in the Northern and Central regions (see Fig. A8 in the appendix). As the implementation of the most stringent policy gradient on the 16th March may indicate, the trend of deaths started to decrease in late March, and the saturation rate in early April. The implementation of the aid distribution system might have increased the regions testing capacity. Considering the prevention and care policies, the graphical analysis may suggest that the enhanced testing capacity corresponds to the flattening of the case fatality rate and to a reduced confirmation rate (see Fig. A8 in the appendix).

Fig. A8.

Prevention and care interventions gradient and case fatality rate (panel A), confirmation rate (panel B), daily number of reported deaths (panel C), ICU saturation (%) (panel D) by geographical areas.

data provided by Ministry of Health [35].

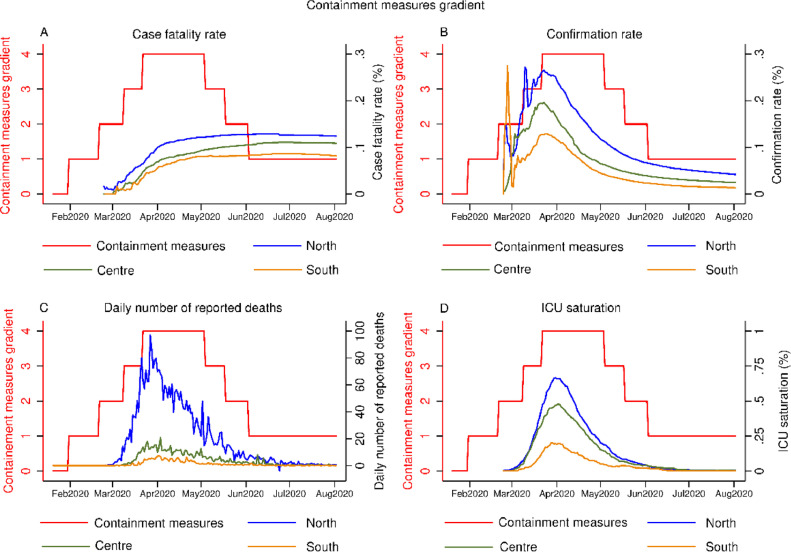

In early March 2020, significant containment interventions were required to ensure the sustainability of the Italian healthcare system, especially in Northern regions. The lockdown implemented on the 9th of March 2020, and the closure of business activities of the 22nd March 2020 coincides with a decreasing trend in daily mortality, especially in northern regions in late March (see Fig. A9 in the appendix). Faster policies escalation in the epicentre of the pandemic might have resulted in a lower peak of deaths, flattening the contagion curve (see Fig. A9 in the appendix). Despite the substantial distribution of equipment throughout the regions, the ICU wards were close to full capacity in the Northern regions. Although Northern and Central regions faced a similar increase in the saturation rate until 14th March 2020, the lockdown timing seemed to be effective in the Central and Southern regions where the severity of the contagion was mitigated, starting to flattener before than in Northern regions (see Fig. A9 in the appendix). The case fatality rate stabilisation coincides with the government's announcement of the exit strategy at the end of April 2020 (see Fig. A9 in the appendix).

Fig. A9.

Containment measures gradient and case fatality rate (panel A), confirmation rate (panel B), daily number of reported deaths (panel C), ICU saturation (%) (panel D) by geographical areas.

data provided by Ministry of Health [35].

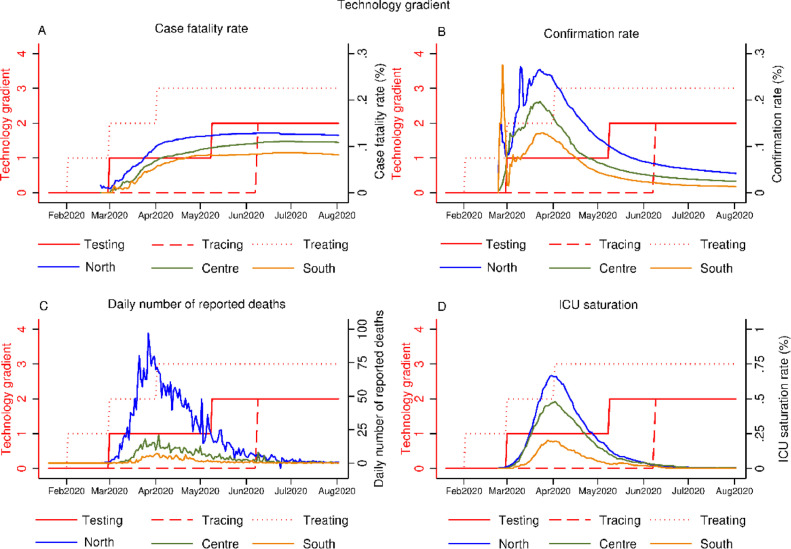

During the period considered in the analysis, the government did not invest resources for the development of tracing technology, which was instead developed for free by a private company. On 9th May 2020, at the start of the exit phase, the government launched a seroprevalence study on a sample of 150,000 individuals. However, significant technological interventions seemed to be far from having any impact on the outcomes considered (daily number of reported deaths and ICU saturation) due to delayed implementation (see Fig. A10 in the appendix). The case fatality rate flattened, and the confirmation rate decreased even though minimal technological interventions were in place (see Fig. A10 in the appendix). The impact of significant technological interventions could be better assessed if a second wave of COVID-19 (or similar diseases) were to occur in the future.

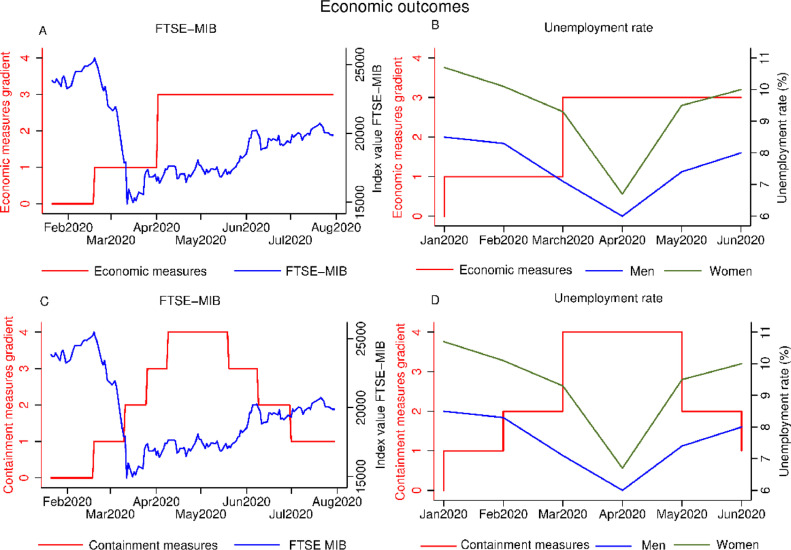

Fig. A10.

Technology intervention gradient and case fatality rate (panel A), confirmation rate (panel B), daily number of reported deaths (panel C), ICU saturation (%) (panel D).

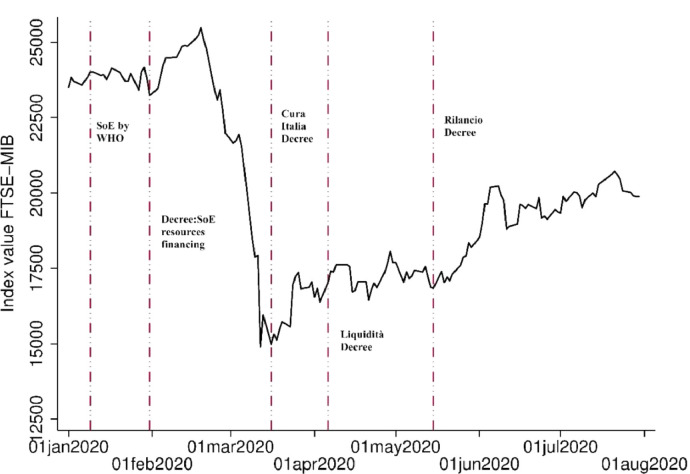

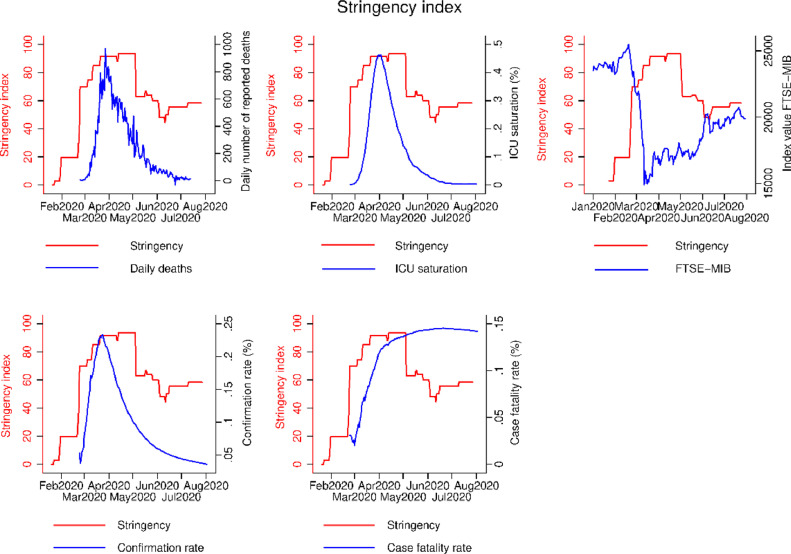

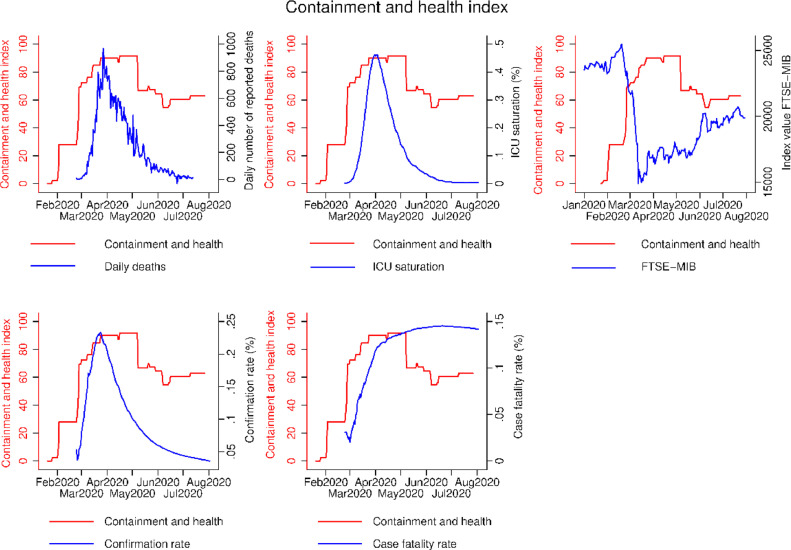

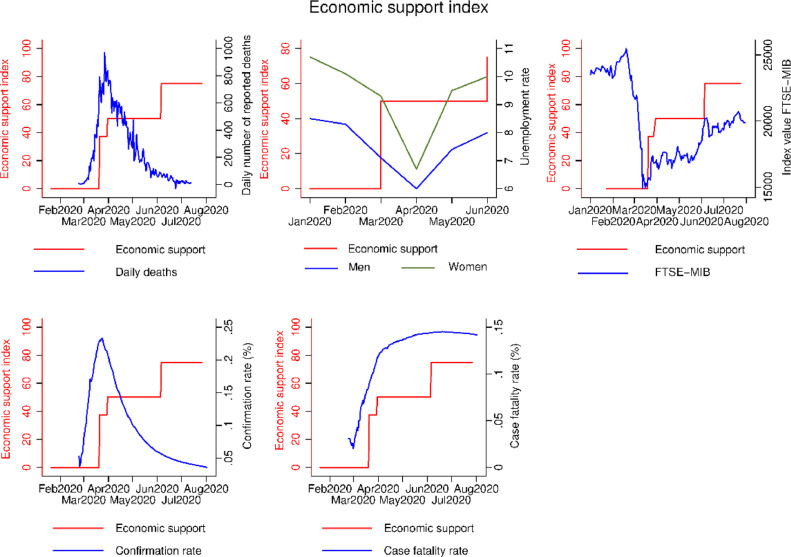

The stringency of the measures is negatively correlated with socio-economic factors. Fig. A12 in the appendix shows an inverse relationship between the stringency of the containment measures and the stock market index value. Fig. A12 in the appendix shows the daily performance of FTSE MIB and the response to major fiscal stimulus packages in Italy. The period from February to mid-March 2020 saw some of the most significant daily drops in the performance of FTSE MIB index. Following the two major decrees, “Cura Italia” and “Decreto Liquidità”, it recorded an increase. In particular, the week beginning 16th March 2020 showed an increase in FTSE MIB (see Fig. A11 in the appendix). Since 25th May 2020, the FTSE MIB index has steadily increased, in response to the stimulus and improving expectations surrounding the recovery effort associated with COVID-19. The lockdown and the subsequent closure of most activities also affected the job market although the unemployment rate did not entirely reflect the lockdown effect due to the reduction in the labour force that decreased by 5% in April 2020 compared to January 2020 decreasing [36] (see Fig. A12 in the appendix). The results displayed in this analysis are consistent with the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker indices (see Figs. A13, A14, A15 and A16 in the appendix) [1].

Fig. A12.

Economic measures gradient and index value FTSE MIB (panels A, C) and unemployment rate (panels B, D).

data provided by Ministry of Health [35].

Fig. A11.

Performance of FTSE MIB index and the response to major events.

data provided by Borsa Italiana [50].

Fig. A14.

The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT): Stringency index.

data provided by the OxCGRT [1].

COVID-19 spillover effects

In this section, we present spillover effects caused by the implementation of social distancing measures and the closure of business activities. The set of policies implemented by the government may have long term effects on mental health and stress levels due to isolation, social distancing and financial loss. During the lockdown, the suicide victims steadily increased. 25 suicides occurred in March and April 2020 from a total number of 42 since the beginning of the year, compared to 14 suicides during the same period in the previous year. More than half of the victims are entrepreneurs. This number is in line with the worsening of the overall economic sentiment in Italy [48].

COVID-19 also had a huge impact on patients’ access to health care, essential services, and education facilities. The high saturation rate in ICU due to a large number of severe COVID-19 cases caused a 23.5% decline in organ donation. As of 4th March 2020, schools and universities closed their facilities and began offering online classes. Although online schooling may represent an effective means of education provision, access is dependant on the availability of internet connection and electronic equipment (i.e. computer, laptop, tablets). With schools remaining closed during the exit strategy, and concerns for a potential second wave in Autumn, the inequality in access may persist, with potential long-term consequences.

Conclusions and policy implications

The outbreak of COVID-19 significantly affected Italy with severe health, social and economic consequences. This paper investigated the set of policy interventions implemented by the government and their impact on health and non-health outcomes. The classification of the policies was based on the comparative and conceptual framework on stringency and invasiveness gradient initially developed by Moy et al. [8].

Our graphical analysis results suggest that the strictness and timing of escalating and de-escalating containment and prevention measures played a major role on health outcomes such as mortality, ICU saturation, and non-health outcomes such as the financial market and trade flows. On the other hand, technological interventions exerted a marginal role due to their delay in implementation. Further empirical analysis is required to support and strengthen the graphical analysis findings.

Without a COVID-19 vaccine, containment, prevention, technological and economic measures are crucial to tackle the direct and indirect effects of the current pandemic and any possible future outbreak. The evidence on timing and stringency of the interventions, alongside transmissibility and severity of the disease, should inform future government policies with the transparency and ready availability of data essential. The production of evidence-based interventions is relevant for reducing uncertainty around the interventions, thereby maximising the resource and investment allocations. A detailed appraisal of the data management system between regions and central government is missing and represents a limitation for further studies.

The threat of future pandemics should drive the government's investments and resources to prevent and promote public health, strengthening community and territorial services, which demonstrate to be particularly successful in some regions to respond to health services organisation and delivery challenges. As far as the sustainability of the healthcare system is concerned, policymakers should focus on the elaboration of the promotion, prevention and early intervention framework to prevent suicide and lower the long-term impact on people's mental health due to isolation, social distancing and high stress levels. Mental health programs should be targeted for different population groups, prioritising those at higher risk. Moving forward governments need to identify and implement plans to mitigate the negative effects of a pandemic on vulnerable groups across society which includes elderly in the home care facilities, students, families with children and the impacted workforce.

Future research on pandemics should focus on public preference elicitation involving the multiple stakeholders in society. Understanding stakeholders’ degree of acceptability of stringent measures could improve communication and enhance compliance with government rules. Since the management of COVID-19 is a global challenge, our findings are relevant not only for Italy but for all countries and governments worldwide.

Acknowledgement

We thank Laura Clarke for assistance with editing of the manuscript.

Author Statements

Funding

None

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

None.

Footnotes

The confirmation rate synthetises the overall national testing strategy variation over time. However, it does not reflect the regional testing strategy that may vary in terms of severity of virus and target population (limited to symptomatic or extensive testing strategy)

We conduct analysis contemporaneously, as well as with 7, 14, 28 days lags and our findings are robust.

Appendix

Table A1.

Governance, financing and provision in the Italian healthcare system.

| Tier | Governance and Organisation | Financing | Provision |

|---|---|---|---|

| National |

Ministry of Health National health plan Long term goals Essential Level of Care (LEA) Set criteria of regions financing Set criteria of ASLs funding Other functions control of industrial production agriculture environmental health standards |

State-Regions Conference Distribution of available funds to regions through the National Solidarity Health Fund financed by the national value-added tax (VAT)- weighted capitation fund National earmarked corporate tax (IRAP) pooled and allocated back to the regions |

|

| Regional |

Regional Department of Health Regional Health Plan: accreditation of public and private providers, monitoring quality of care, health and social care coordination, managing ASL and Azienda Ospedaliera (AOs): geographical boundaries, and appointing their directors |

Regional Department of Health regional taxes became the sources of health care funding- allocation to ASL and hospital (DRG prospective payments) with national rates set by the Health Ministry Raised earmarked corporate tax (IRAP) at regional level A regional surcharge on the national income tax (addizionale IRPEF) |

Independent organizations (AOs, University Hospitals and Public Research Institutes under a regional planning, financial and control scheme Delivery of care |

| Local |

ASL Managing Boards Department Director Health Professionals |

Department Directors Allocation of budget to health districts |

Health Districts Public or accredited private providers under ASL control Delivery of care |

Table A2.

Leading cause of death in Italy (2017) and principal comorbidities amongst the death cohort due to Covid-19 as of 4th June 2020.

| Covid-19 related comorbidities | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Hypertension (67.6%) |

| 2 | Type 2-Diabetes (30.3%) |

| 3 | ischaemic heart disease (28%) |

| 4 | Atrial Fibrillation (22.2%) |

| 5 | Chronic renal failure (20%) |

| 6 | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (16.6%) |

| 7 | Dementia (16.1%) |

| 8 | Active cancer in the past 5 years (15.9%) |

| 9 | Hearth failure (15.7%) |

Data provided by ISS [25].

Table A3.

Description of the data provided at national and regional Level.

| Level | Organisation | Frequency | Items | Publishing modality | Publishing source | Starting period | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Protezione Civile (Ministries’ Cabinet Department) |

Daily | National, regional and provinces level:

|

Open source | Ministry of Health website | 24/02/2020 | Italian English (legend translation) |

| National | Protezione Civile (Ministries’ Cabinet Department) |

Daily | Purchased and distributed by the Government to the single regions:

|

Interactive map/ closed data | Protezione Civile website | 20/03/20 | Italian |

| National | National Health Institute | Daily | National level

|

Epicentro website (epidemiological research department of SSN), department of the National Health I0nstitute | 13/04/20 | Italian English |

|

| National | National Health Institute | Twice per week | National level

|

Epicentro website (epidemiological research department of SSN), department of the National Health Institute | 12/03/20 20/03/20 (comorbidities) |

Italian English |

|

| National | National Health Institute | Twice per week | Regional level

|

Epicentro website (epidemiological research department of SSN), department of the National Health Institute | 13/03/20 | Italian English |

|

| National | National Health Institute | National level

|

Epicentro website (epidemiological research department of SSN), department of the National Health Institute | 16/04/20 | Italian English |

||

| Regional Valle d'Aosta | Regional Government | Daily | Municipality level

|

Region website (twitter) | 9/03/20 | Italian French |

|

| Regional Piemonte | Regional Government | Daily | Municipal level

|

Region website and social media (twitter, facebook) | 21/02/20 | Italian | |

| Regional Lombardia | Regional Government | Daily | Regional level

|

Lombardia notizie- Region website and social media (twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube some content such as press conference) | 21/02/20 | Italian | |

| Regional Provence of Trento |

Regional Government | Daily | Municipalities level

|

Open data | App #TreCovid19 Region website, social media (twitter and Facebook) |

03/03/20 | Italian |

| Regional Provence of Bolzano |

Regional Government | Daily | ASL level

|

Open data Pdf (Deaths by age and sex) |

Region website, social media (Twitter and Facebook) | 15/03/20 | German Italian Ladin |

| Regional Liguria |

Regional Government | Daily | Regional level

|

Website text | Region website, social media (Twitter, Instagram and Facebook daily infographic) | 25/02/20 | Italian |

| Veneto | Regional Government | Twice per day | Province level

|

Interactive infographic | Region website, social media (few info, not systematically) | 25/02/20 | Italian |

| Emilia-Romagna | Regional Government | Daily | Regional level

|

Website text, some infographic | Region website and social media (Facebook, twitter, LinkedIn-not daily) |

26/03/20 | Italian |

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | Regional Government- Regional Protezione Civile | Daily | Municipalities

|

Open data | Region protezione civile website and social media (Facebook and Twitter- regional acts) |

27/02/20 | Italian |

| Toscana | Regional Government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic, website text, pdf | Region website, Facebook and twitter | 26/02/20 | Italian |

| Umbria | Regional Government | Daily | Municipal

|

Interactive dashboard and Open data | Region website, Facebook and twitter, No Instagram page | – | Italian |

| Marche | Regional Government | Daily | Regional

|

Regional website Twitter not systematically, no Instagram page, Facebook |

06/02/20 | Italian | |

| Lazio | Spallanzani and Regional Government |

Daily | Regional (Spallanzani)

|

Lazio Doctor per Covid19 Facebook, twitter |

01/02/20 | Italian | |

| Abruzzo | Regional Government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic, web site text | Regional website Twitter, Facebook regional acts |

05/03/20 | Italian |

| Molise | Regional Government and local | Daily | Provinces

|

Infographic | Regional website |

– | Italian |

| Campania | Regional government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic | Regional website Instagram, Facebook |

12/03/20 | Italian |

| Basilicata | Regional government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic | Regional website |

– | Italian |

| Puglia | Regional government | Daily | Regional

|

Regional website Twitter- not systematically |

02/03/20 | Italian | |

| Calabria | Regional government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic, website text | Regional website Personal account of the Regional President |

13/03/20 | Italian |

| Sicilia | Regional government | Daily | Regional

|

Infographic | Sicilia Sicura app |

03/03/20 | |

| Sardegna | Regional government | Daily | Provinces

|

Infographic | Regional website |

26/03/20 | Italian |

Table A4.

Policy Intervention to contain the spread of the virus (behaviour, containment, mitigation).

| Categorisation | Date | Degree | Definition | What penalty/Amount of fine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Interventions to contain the spread of the virus (Behaviour, containment, mitigation) Dominance: free movement restriction |

22/01/20 | Minimal (1) | Surveillance system task force | |

| 30/01/20 | Minimal (1) | 30/01/20: Ban of Air traffic from and to China | ||

| 31/01/20 | Minimal (1) | Prime Minister Conte declare "State of Emergency for 6 months" | ||

| 21/02/20 | Medium (2) | 21/02/20: The Ministry of Health imposes mandatory quarantine isolation measures and active surveillance with fiduciary home permanence for people coming back from China, positive cases, close/traced contacts, symptomatic patients | ||

| 23/02/20 | Medium (2) | 23/02/20: Decree: • containment measures to be applied in affected areas of Lombardy and Veneto for positive cases, close/traced contacts, symptomatic patients |

||

| 23/02/20 | Medium (2) | 23/02/20: Schools and Universities shut down in Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto | ||

| 25/02/20 | Medium (2) | 25/02/20: Decree: new containment measures • cultural, entertainment, tourism suspended in Emilia-Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lombardia, Veneto, Liguria e Piemonte • health preventions for prisoners |

||

| 01/03/20 | Significant (3) | 01/03/20: “Red zone” decree: • the Italian government lockdown some municipalities of Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna: free movement limitations, no possibility to overcome cities borders, only essential economic activities are open; • business and people activities limitations in Veneto, Emilia Romagna and the province of Pesaro-Urbino; • hygienic and quarantine recommendations for the whole country |

||

| 04/03/20 | Medium (2) | 04/03/20: All Italian schools and University shut down until the 3rd April (extended at a later stage) | ||

| 08/03/20 | Significant (3) | 08/03/20: The Italian government extends the area of the "Red zone" decree to the Northern municipalities and the whole Lombardy. Business restrictions are extended to the whole country |

(1) going out without any reason- 206 Euro fine - 3 months jails; (2) false declaration- up to 2 years gaol; (3) willingness ot infect people (positive people)- life sentence | |

| 09/03/20 | Significant (3) | 09/03/20 Decree #iorestoacasa: • total shut down, free movement limitations, no possibility to overcome cities borders. • Restrictions for businesses (restaurants, bars, pubs, personal care, companies should incentivise home-working) |

(1) going out without any reason- 206 Euro fine - 3 months jails; (2) false declaration- up to 2 years gaol; (3) willingness ot infect people (positive people)- life sentence | |

| 11/03/20 | Significant (3) | 11/03/20: Decree: • Businesses are suspended Exclusions: essential activities (transports, financial and insurance) and good and service supply chain, granted in compliance with hygienic standard. Bars and restaurants can continue with delivery. |

||

| 14/03/20 | Minimal (1) | Safety protocol in the workplace was signed between trade unions and trade associations- Security board for business and enterprises | ||

| 17/03/20 | European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen: external borders ban travel (but for the green leans) | |||

| 18/03/20 | Medium (2) | Extension of schools shut down | ||

| 20/03/20 | Medium (2) | Ministry of Health Act: access to public parks and gardens is prohibited. Physical activities outside can be carried 200 m home, respecting 1 metre distance from other individuals. | (1) going out without any reason- 206Euro penalty+ 3 months jails; (2) false declaration - up to 2 years gaol; (3) willingness ot infect people (positive people) life sentence | |

| 22/03/20 | Very Significant (4) | 22/03 Decree “Chiudi Italia: • People cannot overcome the municipalities borders with public/private transports. Exclusions: work, health (both urgent and to be proved); • Extension of the lockdown for non-essential production activities. Exclusions: supermarket, pharmacies, banking, postal, insurance and financial services will be carried on |

5–30 days closing business (forced)- introduced 24/03 | |

| 25/03/20 | Very Significant (4) | Extension of the “Cura Italia” decree to other economic businesses. For these businesses last productive activities can be accomplished within the 28 of March | (1) going out without any reason: 4000–3000 Euro; (2) business that break shut down measures: 5–30 days forced closing business; (3) positive people break the quarantine: 1–5 gaol | |

| 01/04/20 | Significant (3) | Decree that prologue the lockdown until the 13th of April | (1) going out without any reason: 4000–3000 Euro; (2) business that break shut down measures: 5–30 days forced closing business; (3) positive people break the quarantine: 1–5 gaol | |

| 10/04/20 | Significant (3) | 10/04/20 Decree: Lockdown prolonged until the 3rd of May | (1) going out without any reason: 4000–3000 Euro; (2) business that break shut down measures: 5–30 days forced closing business; (3) positive people break the quarantine: 1–5 gaol | |

| 31/03/20 | Minimal (1) | Ministry of Interior Act: children and young people (aged 0–18) can go out - sister/brother/family adult member that share the same house (ratio n:1 adult) | ||

| 10/04/20 | Minimal (1) | 10/04/20 Decree: • Re-openings of some businesses: book shops, stationery shop, children and newborn shops. |

||

| 26/04/20 | Significant (3) | Prime Minister signed "Phase 2″ Decree- starting from the 4th May. It has three phases From the 4th May: 1) Parks reopening; 2) Free movement in the same region; 3) Free movement in different regions has to be justified by heath, work reasons; 3) Relatives visiting with personal protections; 4) sport activities is allowed at 2 m social distancing form others; 5) athletes training will be allowed for individual sports; 6) funeral ceremonies open air: 15 people maximum; 7) bar and restaurants take away; 8). re-start of activities: manufacturing, building companies, transportations respecting security and hygienic -new security guidelines From the 18th May: 1) Reopening of commercial activities, museums, libraries; 2) team sport activities allowed. From the 1st June: 1) bar, restaurant, gyms, personal care (hairdresser, barbers etc.) reopening The Ministry of health provides epidemiological threshold to Regions - specific areas can come back to lockdown above the threshold |

||

| 30/04/20 | Significant (3) | Ministry of health act: phase 2 monitoring system, diagnostic assessment, contact tracing criteria, health system capacity assessment. For each criteria a threshold is set. Over the threshold the regions have to come back to lockdown. | ||

| 4/05/20 to 18/05/20 |

(replaced) |

Exit Strategy Step 1 (replaced) | ||

| 18/05/20 to 01/06/20 |

(replaced) |

Exit Strategy Step 2: 1) reopen of commercial activities, museums, libraries; 2) team sport activities allowed (replaced) |

||

| 17/05/20 | Significant (3) | New “phase 2″ decree: • The reopening strategy is left to regions. The government can impose the lockdown if the epidemiological curve and the rate of transmission overcomes the threshold imposed by the Ministry of Health. • Protocols for religious gatherings, working place, security guidelines for workers, transports (public, aeroplane, cruise). • People must wear facemasks in closed public places and on public transport and social-distancing rules must be respected. • Schools remain closed until September |

||

| 18/05/20 to 25/05/20 |

Medium (2) | National Guideline for re-openings (not mandatory): • 18 May: Hairdressers, barbers, beauty salons and beaches are reopening |

||

| 25/05/20 to 03/06/20 | Minimal (2) | • 25 May: Swimming pools, gyms and other sports facilities | ||

| 03/06/20 to 15/06/20 | Minimal (1) | • 3 June: movements between regions | ||

| 15/06/20 | Minimal (1) | • 15 June: Theatres and cinema |

Table A5.

Policy interventions for prevention and care (treatments, vaccines, health monitoring).

| Categorisation | Date | Degree | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Interventions for prevention and care (treatments, vaccines, health monitoring) Dominance: Public healthcare system takeover. All resources devoted to the public healthcare system. |

21/01/20 | Minimal (1) | Sanitary checks for passengers at Fiumicino airport (Rome) and Milano Malpensa airport |

| 22/01/20 | Minimal (1) | Italian Health Minister implements a COVID-19 taskforce | |

| 27/01/20 | Medium (2) | Training to medical workforce to acquire skills to deal with COVID-19 emergency | |

| 27/01/20 | Minimal (1) | Hotline number "1500″ activation | |

| 01/03/20 | Significant (3) | Protezione Civile aids distribution to the regions: durable and non-durable equipment | |

| 04/03/20 | Significant (3) | Increase of 50% capacity ICU & 100% pneumology. Involve private structures | |

| 16/03/2020 | Very significant (4) | Private healthcare facilities, accredited and non-accredited, must make their healthcare personnel, premises and equipment available. | |

| 19/03/20 | Significant (3) | Medical task force (300 doctors) on voluntary bases to send in most affected areas | |

| 03/04/20 | Minimal (1) | Ministry of Health public tender: COVID-19 research (medical and policy) | |

| 27/04/20 |

Minimal (1) | Psychological support hotline number launch: 800.833.833 | |

| 28/04/20 |

Minimal (1) | Masks price is set by the government to 50cents each | |

| 04/05/20 | Significant (3) | Partial re-opening of hospitals and private accredited structures |

Table A6.

Health Technology interventions for prevention and cure (treatments, vaccines, health monitoring).

| Categorisation | Sub-category | Date | Degree | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Technology Announcement or use of health technology Categorisation is based on the size and invasiveness/extent of the technology |

Testing (Objective based criteria: confirming, exploring, expanding) | 01/03/2020 | Minimal (1) | Protezione Civile aids distribution to the regions: durable and non-durable equipment |

| 04/05/20 | Minimal (1) | Fast kits and Seroprevalence can be bought in some regions by government and private citizens | ||

| 09/05/20 | Medium (2) | 09/05/20 Decree- Seroprevalence research conducted by ISTAT and Ministry of Health to develop epidemiological studies and statistics on immunity population status | ||

| Tracing (degree of invasiveness of the technology) | 17/04/20 | Medium (2) | The government announces the agreement with Bending Spoons S.p.a for the development of the National tracing app IMMUNI | |

| 08/06/20 | Medium (2) | IMMUNI app launch: piloting study in 4 regions: Abruzzo, Puglia, Marche, Liguria | ||

| Treating (the extent of advancement of technology) | 01/02/20 | Minimal (1) | Virus isolation- Infectious Disease National Institute Spallanzani | |

| 04/02/20 | Minimal (1) | Health corridors, thermal scanner and additional medical personnel at Fiumicino airport (Rome) | ||

| 01/03/20 | Medium (2) | Protezione Civile aids distribution to the regions: distribution of advanced protective equipment (PPE) | ||

| 02/04/20 | Significant (3) | Repurposing of drugs (Idrossiclorochina for adult patients) https://www.aifa.gov.it/aggiornamento-sui-farmaci-utilizzabili-per-il-trattamento-della-malattia-covid19 |

Table A7.

Economic Impact Policy Interventions.

| Categorisation | Sub category | Date | Degree | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Impact Policy Interventions | Escalating Interventions: Based on the size and the extent of the stimulus package that is implemented as a result of the pandemic |

31/01/20 | Minimal (1) | 31/01/20 Decree: State of emergency resources 5 million Euro for financing the healthcare sector |

| 24/02/20 | Medium (2) | 24/02/20 Minister of Finance Deecree - suspension of taxpayer obligations for all residents in the outbreak areas | ||

| 28/02/20 | Medium (2) | 28/02/2020: Red zone decree a. 500 Euro per month up to three months for affected workers; b. 2.5 million Euro or Small-Medium enterprises; c. 350 million Euro for exporting companies |

||

| 13/03/20 | Significant (3) | ECB President Lagarde announces QE program: • 120 billion Euro • no cutting interest rates |

||

| 16/03/20 | Significant (3) | “Cura Italia” decree: a. 1,65 billion Euro to the healthcare system: b. 50 million Euro to purchase medical devices. c. 600 Euro per month for affected workers d. Fund of 300 million Euro for self-employees professionals e. 600/1000 Euro per month to low income families and disabled people |

||

| 17/03/20 | Significant (3) | European fiscal compact suspension | ||

| 18/03/20 | Significant (3) | ECB announces Euro 750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) | ||

| 28/03/20 | Medium (2) | Decree: Municipalities Solidarity fund 4.3 billion Euro Protezione Civile Act: food solidarity for municipalities (400 million Euro) |

||

| 06/04/20 | Medium (2) | 06/04/20 Decreto Liquidità: Credit access and fiscal measures a. VAT suspended for business that registered 33% earnings decreased, earning < 50 million Euro and 50% above this threshold; b. fiscal payments are suspended for businesses that started on April 2019, fiscal measures suspended for all the businesses that registered 33% earnings decreased with no threshold, until June in the Provinces of Bergamo, Brescia, Cremona, Lodi and Piacenza |

||

| De-escalating interventions | 15/04/20 | Medium (2) | Economic Development Ministry Act: funding for development (200,000 billion Euro): • programs of the biomedical and telemedicine sector, • strengthening of the national system of production of medical devices and • services aimed at the prevention of health emergencies |

|

| 15/05/2020 | Significant (3) | Decree “Rilancio”

|

Table A8.

Definition of the cases, testing and tracing strategy.

| Act | Criteria | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How cases are recorded | Ministry of Health Act- Circolare del Ministero della salute 9 marzo 2020 |

Cases are classified as: Probable:

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5373&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto#2 http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73669&parte=1%20&serie=null |

| Testing criteria | Ministry of Health Act- Circolare del Ministero della salute 9 marzo 2020 |

Diagnostic test should be performed if the patient presents the following symptoms

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5373&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto#2 http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73669&parte=1%20&serie=null |

| Minsitry of Health Act- Circolare del Ministero della salute del 3 aprile 2020 |

Diagnostic tests and criteria to be listed in the definition of priorities:

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5373&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto#2 http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73799&parte=1%20&serie=null |

|

| Contact tracing | Ministry of Health Act- Circolare del Ministero della salute del 20 marzo 2020 |

Contact tracing for:

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5373&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto#2 http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=73714&parte=1%20&serie=null |

| How deaths are recorded | Ministry of Health Act COVID-19: indicazioni per la compilazione della scheda di morte |

Deceased can be classified as:

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5373&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto#2 http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pagineAree_5373_11_file.pdf |

| How recovered are recorded | Ministry of Health- Technical Scientific Committee – 19th of March | Recovered are classified as: Clinically recovered:

Recovered:

Clearance

|

http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioNotizieNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=4274 |

Fig. A13.

The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT): containment and health index.

data provided by the OxCGRT [1].

Fig. A15.

The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT): economic support index.

data provided by the OxCGRT [1].

Fig. A16.

The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT): government response index.

data provided by the OxCGRT [1].

References

- 1.Hale T., Hangrist N., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., Webster S. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Version 60 Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper. 2020.

- 2.Ferguson N., Laydon D., Nedjati Gilani G., Imai N., Ainslie K., Baguelin M., et al. Report 9: impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. 2020.

- 3.Klonowska K., Bindt P. Hague Centre for Strategic Studies; 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic two waves of technological responses in the european union. [Google Scholar]