Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, about 22 nucleotides, non-coding RNAs which regulate a wide range of gene expression during post-transcriptional stage. They are released into intra- and extracellular microenvironments and play vital roles in different physiological and pathological pathways. Due to easy accessibility, detection of extracellular miRNAs in body fluids, e.g. serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and follicular fluid, has been explored in recent years. Since miRNAs are stable at unsuitable conditions, scientists have been investigating to use them as biomarkers in different fields of medicines. It goes without saying that experienced biomarkers would be required in reproductive medicine as well. Biomarkers can help clinicians and embryologists to diagnose disorders and assess the embryo quality via molecular pattern which is more reliable than nowadays routine methods. Follicular fluid as a noninvasive fluid in assisted reproductive techniques (ART) has attracted researchers as a rich pool for biomarkers, and miRNAs are not exception. Although miRNA biomarkers in reproduction field are located on their initial stage and there is a long path to move forward, several meticulous studies have been performed and discovered their associations with various conditions. In this regard, we summarize the reported miRNAs in follicular fluid and their correlations with female infertility and ART success rate, while subsequent investigations are required.

Keywords: MicroRNAs, Biomarkers, Reproductive medicine, Follicular fluid, Assisted reproductive techniques

Introduction

Female reproductive cycles consist of several different processes [1]. The spatiotemporal pattern of gene expression is involved in different compartments of ovary including oocyte, surrounding cumulus, granulosa, theca cells, and also follicular fluid [2]. MiRNAs are one of the important molecules that play vital roles in regulation of gene expression [3]. Studies have indicated that miRNAs in follicular fluid alter during various stages of follicle development and are significantly involved in oocyte maturation [1]. For instance, in a study by Sohel et al., follicular fluid miRNAs could be taken up by granulosa cells and altering endogenous miRNA and mRNA expression [4]. Moreover, their protective effects against stress conditions of oocytes have been proved in animal models [5].

On the other hand, assessment of oocyte quality and developmental competence of regarded embryo by morphological criteria is not a strong and reliable indicator [4, 6]. Moreover, the current genetic screening methods of embryos are invasive and cannot be performed for all cases. Thus, evaluation of oocytes and embryos quality by molecular biomarkers would increase the success chance in ART [7]. Follicular fluid is an important pool for biomarkers to predict the quality of oocytes and embryos, and recent studies have been shifted to find these biomarkers in follicular fluid microenvironment [8–10]. Since extracellular miRNAs are highly stable and can be protected by RNase activities due to coating with membrane envelopes, such as microvesicles and exosomes, they have been noticed as a new field of reliable biomarkers [11].

Identification of miRNAs in follicular fluid has also opened new doors in understanding their roles in different signaling pathways, especially in female reproductive disorders, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and premature ovarian failure (POF). Thus, the study on follicular fluid miRNAs can help us to find stable biomarkers for embryo quality, diagnosis of several diseases, and also in the long run miRNA targeting therapy. In this review we are supposed to highlight the detected follicular fluid miRNAs in relation to women reproductive potential.

Search method

The PubMed and Google Scholar databases were used in searching for the following keywords: “Follicular fluid” AND (“microRNA” OR “miRNA” OR “miR”) with/without (“assisted reproductive techniques” OR “ART” OR “outcome” OR “fertilization” OR “oocyte” OR “embryo” OR “endometriosis” OR “PCOS” OR “poly cystic ovarian syndrome” OR “POF” OR “poor responder”). Published articles in English language, until January 2020, were extracted, and those that were performed on follicular fluids of humans were included to review.

MiRNAs’ biogenesis

MiRNAs, as small non-coding RNAs, were first discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans with the name Lin4 in the 1990s and revolutionized the molecular biology field [12, 13].

They are encoded by intergenic regions and introns which are referred as Junk DNA [13, 14]. MiRNAs consist of 18–24 nucleotides that are produced by a large primary transcript of 1–3 kb, as pri-miRNAs. They are processed to precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) with a 70-nucleotide length, by a class 2 RNase III, Drosha. The pre-miRNAs are transferred to cytoplasm by exportin-5 (EXP-5) with Ran-GTPase. They are processed to mature miRNAs by Dicer RNase in cytoplasm. The final ~ 22 bp miRNA/miRNA* are separated from each other to 2 one-strand miRNAs, one guide strand which will be incorporated to Argonaute (AGO) protein of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and the other strand, passenger strand, will be degraded in cytoplasm [15]. The mature miRNAs can interact not only with 3'UTR region of targeted mRNAs but also 5'UTR, gene promoters, and coding sequences [13, 16]. Capable to degrade or translationally repress the target mRNA [17, 18], they can activate gene expression in some situations as well [19, 20].

MiRNAs can be placed in intra- and extracellular microenvironments [15]. Nowadays, several extracellular miRNAs and their targets have been discovered in body fluids, such as serum [21, 22], plasma [23, 24], saliva [25, 26], seminal plasma [27, 28], peritoneal fluid [29, 30], urine [31, 32], cerebrospinal fluid [33, 34], and follicular fluid [35–37]. Releasing miRNAs to body fluids can be performed by apoptotic bodies [38–41], microvesicles [42–46], exosomes [47–51], and AGO proteins and high density lipoproteins (HDL) [15, 52–55]. Exactly as other fluids, follicular fluid contains numerous miRNAs that can change during different physiological and pathological stages [56]. Since miRNAs are stable for a long time and in unfavorable conditions, they have been noticed as biomarkers in different diseases [57]. Due to the fact that follicular fluid is a rich source for various molecules that can be associated with different reproductive disorders and quality of oocytes and embryos, miRNA profiling in follicular fluid has been extended in recent years.

However, it is important to note that despite the good potential for being as biomarker, miRNA isolation from body fluids has been a challenge for scientists. Principally, there are 2 main strategies for isolating miRNAs from follicular fluids: only miRNAs encapsulated within extracellular vesicles (EV-miRNAs) or total extracellular miRNAs from supernatant. EV-miRNAs can be extracted by traditional methods (e.g., ultracentrifugation and density gradient) or commercial kits [58], followed by RNA extraction. MiRNA isolation from supernatant can be performed by reagents (e.g., TRIzol phase separation) or commercial kits [59]. Studies demonstrated that different extraction methods can make a large bias on yield of miRNAs extracted from the same sample [59–61]. Thus, it is important to introduce one as a gold standard method for follicular fluid miRNA extraction, and scientists follow it for the future studies.

MiRNAs in follicular fluid

Follicular fluid provides the communication between the cells within the follicle via plenty of molecules that are received from the surrounded microenvironment [62]. MiRNAs are one of those important molecules that are released and received by follicle compartments and play crucial roles in oocyte growth [3]. Recently, scientists attempted to discover their roles in different physiological and pathological situations alongside several productive studies that have been performed. Hereunder, we elucidated a brief summary of discovered follicular fluid miRNAs that play roles in normal folliculogenesis.

For the first time, Da Silveira et al. discovered follicular fluid miRNAs in equines that were detected in exosomes and microvesicles in 2012 [35]. In the following year, the first report of miRNAs in human follicular fluid was submitted by Sang and colleagues [63]. Identified miRNAs were associated with endocrine and metabolic pathways. They reported that miR-520c-3p, miR-320, miR-132, and miR-222 were able to increase estradiol secretion, while miR-24 regulated estradiol by decreasing the concentration. MiR-483-5p, miR-193b, and miR-24 were also capable of affecting progesterone concentration by declining the secretion. To prove their regulatory roles in estradiol and progesterone secretion, they transfected the above mentioned miRNAs inhibitors to KGN cell line. As it was expected, miRNA inhibitors acted in opposite patterns of reported functions. They also noted that steroidogenesis roles of miR-193b, miR-222, and miR-520c-3p were triggered by targeting the estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1). Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is a tumor suppressor and insulin regulator, was another target of miRNA-222. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tumor growth factor-1 (TGF-1), two important pathways in cell proliferation and metabolism, were targeted by miR-1290, miR-574-3p, and miR-24 in follicular fluid. Immune system involvement (interleukin-8 (IL-8), IL-10, IL-37, and IL-12B) by miR-320, miR-146a, miR-483-5p, and miR-191 was also mentioned in the report [63]. Thus, a broad spectrum of miRNA roles in human follicular fluid was introduced by Sang and colleagues (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of follicular fluid miRNAs in relation with factors in serum/plasma.

| miRNA(s) | Target(s) in serum/plasma | Correlation | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-520c-3p, miR-320, miR-132, miR-222; miR-24 | Estradiol | Positively; negatively | [63] |

| miR-483-5p, miR-193b, miR-24 | Progesterone | Negatively | [63] |

| miR-199b-5p | AMH in PCOS | Positively | [68] |

| miR-93-3p | CRP in PCOS | Positively | [68] |

| miR-382-5p; miR-381-3p | FAI in PCOS; normal | Positively | [68] |

| miR-302c-3p | LDL cholesterol in PCOS | Positively | [56] |

| miR-29a-3p | DHEAS | Positively | [56] |

| miR-151-3p, miR-21, miR-93; miR-518f-3p | Free and total testosterone | Negatively; positively | [56, 82] |

| miR-320a, miR-518f-3p | FSH in PCOS | Negatively | [56] |

| miR-320a | Fasting glucose | Negatively | [56] |

| miR-24-3p, miR-320a; miR-145 | E2 in normal | Negatively; positively | [56, 77] |

| miR-486 | E2 in PCOS | Negatively | [84] |

| miR-15a, miR-145 | LH | Negatively | [77] |

| miR0182 | TSH in normal | Positively | [77] |

| miR-182 | FSH and fasting plasma glucose | Negatively | [77] |

| miR-146a | Insulin in PCOS | Positively | [84] |

| miR-155 | IL-6 in PCOS | Negatively | [84] |

Continuous research on follicular fluid miRNAs resulted in discovering more about their critical roles in reproductive physiology, as well as their main source of secretion to follicular fluid. For instance, detection of miR-508-3p in follicular fluid (but not plasma) proved that it was secreted by intra-follicular cells. However, it was unclear whether the follicular fluid-specific miRNAs were secreted by oocytes or follicular somatic cells and would act in paracrine or autocrine manner [64]. To answer this question, Battaglia and colleagues compared the follicular fluid miRNAs with miRNA profile within the oocytes to investigate whether they were originated from oocytes or other follicular cells. They identified 267 miRNAs in follicular fluid by TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA). Since 158 of them were expressed only in follicular fluids (were not detected in oocytes), it could be concluded that they were secreted by somatic cells of the follicles. Moreover, targeting 1099 mRNAs by follicular fluid miRNAs revealed the critical roles of miRNAs in folliculogenesis. Detected miRNAs were mostly related to endogenous stimuli response, apoptotic processes, cell differentiation, development, and intracellular signaling transduction. Signaling pathways were associated with cellular response to stress (e.g., p53, interleukin, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), FAS, and p38 MAPK), embryo development (e.g., angiogenesis, EGFR, WNT, and notch), and oocyte maturation (e.g., gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor, RAS, TGF-β, and phosphoinositide 3 (PI3) kinase) [65]. It is evident that these pathways are highly important in ovaries and dysregulation of each signaling can cause a disruption in follicle growth.

Another evidence for follicular fluid miRNA regulatory roles in follicle development is that their expression patterns are being altered in different stages, from immature to mature oocyte [2, 7, 66]. For instance, Moreno et al. analyzed the miRNA profile in follicular fluids of metaphase II (MII), metaphase I (MI), and germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes. They found 13 differentially expressed miRNAs, when compared GV with MII. Of them, miR-451 and miR-563 had the highest levels in follicular fluids of GV and MII oocytes, respectively. GnRH signaling was the most frequently involved pathway, revealing that follicular fluid miRNAs are one of the key factors in follicle development through this crucial signaling pathway. Seven miRNAs were also detected to be different in follicular fluids of MI in comparison with MII. Beyond these 7 miRNAs, miR-451 that was higher in GV (when compared with MII) was also stayed at a high level in MI. MiR-574-5p was the highly expressed miRNA in MII follicular fluid. PI3K/AKT, focal adhesions, and ECM-receptor interaction were the involved signaling pathways [67]. Scalici and colleagues also reported that miR-320a level was positively correlated with number of MII oocytes in pooled follicular fluids (> 2 vs. ≤ 2) [8] and indicates that it may have a role in triggering oocyte maturation.

To sum up, studies on follicular fluid miRNAs introduced a wide spectrum of miRNAs that are involved in important reproductive signaling pathways and may have potential for being a biomarker for different physiological and/or pathological situations.

Follicular fluid miRNAs and ART outcome

Since molecular profile alteration in follicular fluid can directly influence oocyte developmental competence, from fertilization to embryo implantation, researchers attempt to investigate the factors related to each stage of development. Finding these factors as biomarkers, especially in follicular fluid, can help embryologists to assess and predict the ART outcome by molecular pattern which will be more reliable than a mere morphological analysis. In this regard, several meticulous studies have been performed that we summarized in the following.

To detect fertilization-related miRNAs in follicular fluid, Machtinger and colleagues divided mature oocytes to normally, abnormally, and failed fertilized groups. Among discovered miRNAs, 58 miRNAs were detected only in normal, 2 in abnormal, and 5 in failed groups. That is to say, many normal fertilization correspondence miRNAs were not expressed in follicular fluids of abnormal and failed fertilized oocytes. Analysis showed that miR-16-1-3p, miR-1244, miR-206, and miR-202-5p were significantly and positively correlated with normal fertilization when compared with failed fertilized group. On the other hand, miR-16-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-425-3p, and miR-454-5p expression levels seemed to be associated with abnormal fertilization, as were upregulated in regarded group when compared with normal [10]. In another study, Martinez and colleagues detected 12 EV-miRNAs to be differentially expressed in follicular fluids of failed and successfully fertilized oocytes. Among them, miR-122 was under-expressed in follicular fluids of oocytes with failing fertilization. With and without regard to categorizing the groups by body mass index (BMI), age, smoking, total motile sperm count, etc., miR-130b and miR-92a were upregulated in follicular fluids of unfertilized oocytes when compared with fertilized ones. Analysis showed that the 2 miRNAs were involved in TGF-β, p53, FOXO, cell cycle, oocyte meiosis, mTOR, notch, and estrogen signaling pathways [9] (Table 2). Although the last two studies were conducted by the same team, miR-1244 and miR-206 that were reported by Machtinger et al. could not be detected by Martinez and colleagues, which may be due to the different EV and miRNA isolation methods (commercial kit in the first and ultra-centrifuge in the last study) or different sample sizes. Thus, it requires more research to prove their potential for being as biomarker.

Table 2.

List of follicular fluid miRNAs in relation with ART outcome

| miRNA(s) | Alteration | Correlated with | Target pathway(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7c, miR-122; miR-542-3p, miR-92a, miR-29a, miR-130b, miR-31-3p, miR-192, miR-210, miR-22, miR-503, miR-98 | ↓; ↑ | Failed fertilization | ErbB, MAPK, TGF-β, AMPK, etc. | [9] |

| miR-130b, miR-92a | ↑ | Unfertilized oocyte | TGF-β, p53, FOXO, mTOR, notch, etc. | [9] |

| miR-16-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-425-3p, miR-454-5p; miR-16-1-3p, miR-1244, miR-206, miR-202-5p | ↑ | Abnormal; normal fertilized oocyte | TGF-β, WNT, MAPK, etc. | [10] |

| miR-382-5p, miR-127-3p, miR-425-3p | ↑ | Fertilization rate | - | [68] |

| miR-214, miR-454; miR-766-3p, miR-132-3p, miR-16-5p;, miR-197, miR-320a | ↑ | Top quality day 3 embryo | ErbB, mTOR, TGF-β, p53, etc.; MAPK; WNT | [9, 10, 69] |

| miR-888 | ↓ | Top quality day 3 embryo | ErbB, mTOR, TGF-β, p53, etc. | [9] |

| miR-663b | ↓ | Day 3 embryo quality, viable blastocyst, expanded blastocyst | MAPK, WNT, TGF-β | [10, 71] |

| let-7b | ↓ | Blastocyst formation, expanded blastocyst | TGF-β | [8] |

| miR-451 | ↓ | Diminished fertilization and embryo quality in endometriosis | WNT | [89] |

| miR-29a | ↑ | Clinical pregnancy | - | [8] |

The last investigation on fertilization related miRNAs was performed by Butler and colleagues. Since the results demonstrated that the levels of miR-382-5p, miR-127-3p, and miR-425-3p in follicular fluids were associated with fertilization rate in normal women, they introduced them as candidates for fertilization biomarkers [68] (Table 2). However, their direct effects through signaling pathways were not clear, and more investigations are required to be done.

Besides fertilization related miRNAs, several miRNAs were also detected to have correlation with embryo quality. For instance, Feng et al. reported that higher levels of miR-197 and miR-320a in human follicular fluid were associated with day 3 embryo quality. They also injected miR-320a inhibitor into mice MII oocyte. The result demonstrated the impairment of oocyte competence for embryo development and concluded that miR-320a plays a vital role in embryo quality [69]. Based on the research that was performed by Martinez and colleagues, 7 EV-miRNAs in follicular fluids were correlated with quality of day 3 embryos. Among them, miR-214 and miR-454 were upregulated, while miR-888 was downregulated in follicular fluids of oocytes that were developed to top quality embryos. Further, they found that ErbB, mTOR, TGF-β, unsaturated fatty acid biogenesis, p53, and gap junction were the most common signaling pathways [9] (Table 2). In contrast to the positive correlation of miR-454 with top quality embryo [9], another study had reported a negative association of mentioned miRNA with normal fertilization [10]. It seems unreasonable that an miRNA that has a negative effect on normal fertilization plays a positive role in embryo quality. This controversy may imply sperm potential on fertilization and embryo development which was hidden in the studies. Thus, at the time of finding biomarkers, the more consistently equivalent inclusion and exclusion criteria for semen parameters are required to avoid sperm’s defective effects on ART outcome. Nevertheless, it may be due to the different methods that were used for miRNA isolation and represents the need of introducing a gold standard method for follicular fluid miRNA isolation. Thus, controversial problems may be solved by these considerations, and practical application of miRNAs as biomarkers would be more reliable.

Ongoing studies on biomarker investigation for embryo quality resulted in introducing more associated miRNAs. For instance, Machtinger et al. proved that miR-132-3p, miR-766-3p, and miR-16-5p expression levels were positively correlated, while miR-663b was negatively correlated with day 3 embryo quality. In silico IPA analysis revealed that the mentioned miRNAs were involved in MAPK signaling pathway [10] that plays an important role in cell proliferation, especially during embryogenesis [70]. In another study, Fu and colleagues confirmed miR-663b correlation with embryo quality [71]. Their results demonstrated that miR-663b expression level in follicular fluid was significantly and inversely related to viable blastocyst and also top quality blastocyst when compared with nonviable and low quality ones. They finally introduced miR-663b as a biomarker for prediction of IVF outcome [71]. Another biomarker candidate relating to blastocyst formation is let-7b that was introduced by Scalici and colleagues. They reported an inversely correlation between let-7b in follicular fluid and blastulation and expanded blastocyst rates. With the high sensitivity and specificity, they suggested let-7b as an intra-follicular biomarker to predict the potential of blastocyst development [8] (Table 2). Interestingly, the study on animal model indicated that let-7b was decreased in ovaries of non-pregnant in comparison with pregnant goats [72], which may indicate the existing correlation between mentioned miRNA and blastocyst potential for development and implantation to uterus. Thus, to conclude, miR-663b and let-7b approval by two distinguished studies may provide them as reliable biomarkers for embryo quality. However, it has to be noticed that in all studies, embryo quality assessment was performed by morphological criteria, while genetic abnormalities of embryos were not investigated. Since the main reason of biomarker requirement is to represent molecular profile of embryos that could be more trustworthy than common morphological criteria, we recommend to evaluate reported miRNA correlations with chromosomal abnormalities of embryos to introduce more reliable biomarkers that would be more safe to use in ART.

On the other hand, because the main goal of ART outcome is pregnancy, it is important to have biomarkers for estimating the final success chance of couples in ART. Based on our research, only one study assessed the follicular fluid miRNA correlation with pregnancy which demonstrated that the level of miR-29a in follicular fluid was in a positive relation with clinical pregnancy [8] (Table 2). Although the sensitivity was high (83.3%), the specificity was low (53.5%). Since miR-29a was also detected in rat uterus and upregulated during implantation [73], it can be concluded that the mentioned miRNA may have an impact on pregnancy from both uterus and follicle side. But due to the low specificity of miR-29a in human follicular fluid, and lack of sufficient studies on pregnancy correlated miRNAs in follicular fluid, future studies are required to discover more specific biomarker.

Follicular fluid miRNAs and ovarian-related disorders

PCOS, poor ovarian response, and endometriosis are the most prevalent female reproductive disorders that are diagnosed by conventional clinical methods. However, their definition and diagnostic criteria are not stable and have been changed over the years [74, 75]. Thus, using biomarkers in combination with current medical examinations can help the more accurate diagnosis [76]. In this respect, scientists attempt to find biomarkers related to different disorders in body fluids to increase the diagnosis efficiency. In the following we highlighted the reported miRNAs in follicular fluid that were correlated with ovarian-related diseases.

Studies on finding a biomarker related to PCOS demonstrated that a variety of miRNAs are dysregulated in serum, plasma, ovarian granulosa cells, and follicular fluids of patients [77–79]. For instance, initially Sang et al. compared the follicular fluid miRNAs of PCOS with normal women [63]. Among the miRNAs they detected in both supernatant and microvesicles, miR-320 and miR-132, which positively correlated with estradiol concentration, were significantly reduced in PCOS follicular fluids. Based on bioinformatics analysis, the high mobility group AT-hook2 (HMGA2) and Ras-related protein Rab-5B (RAB5B) that had reported to play roles in PCOS etiology [80] were targets of miR-132 and miR-320, receptively [63]. The following year, Roth et al. reported differentially expressed miRNAs in follicular fluids of PCOS in comparison with donor group (the PCOS group was older than the control). However, they could not detect the differential expression of miRNA-320 and miRNA-132 that were reported in the previous study (may be due to the different ethnics of patients or distinguished methods that were used by two studies). Roth and colleagues found 29 miRNAs with different expression levels, and among them, 10 miRNAs showed the largest difference. Of them, 5 miRNAs (miR-9, miR-135a, miR-34c-5p, miR-32, and miR-18b) were significantly increased in the PCOS group. Insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), synaptogamin 1 (SYT1), and IL-8 (inflammation and insulin regulation pathways) were targeted by the miRNAs [81]. In another experimental case-control study, follicular fluid miRNAs of normo- and hyper-androgenic PCOS were monitored alongside normal ovarian reserve women. The results demonstrated that 3, 11, and 53 miRNAs were expressed only in follicular fluids of normal, hyper-androgenic PCOS, and normo-androgenic PCOS, respectively. Among the detected miRNAs, they chose 12 miRNAs for further analysis, based on previous reports of associations with PCOS, specificity, or largest differential expression levels. Results demonstrated that miR-29a, miR-574-3p, miR-24-3p, and miR-151-3p were distinguished miRNAs between healthy and PCOS women (reduced in both normo- and hyper-androgenic PCOS). Between hyper- and normo-androgenic PCOS, miR-518f-3p was the highly differentiated in expression, upregulated in hyper-androgenic group, and the level was correlated with serum-free testosterone. Conversely, miR-151-3p was negatively associated with serum-free and total testosterone. They finally evaluated the diagnostic value of every detected miRNAs and suggested miR-151-3p as a diagnostic marker for PCOS [56]. In the same year, Scalici et al., who introduced let-7b as a blastulation potential biomarker with inversely correlation, also reported that let-7b and miR-140 were downregulated and miR-30a was upregulated in follicular fluids of PCOS when compared with the normal group. Due to the high specificity and sensitivity, they suggested the combination of the 3 mentioned miRNAs as PCOS biomarkers [8]. In two separate studies, we also evaluated the miRNAs in PCOS follicular fluids. In one study, miR-182 correlated with levels of FSH, estradiol (E2), fasting plasma glucose, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) in serum and upregulated in PCOS follicular fluids when compared with the normal group. Signaling pathway analysis revealed that PI3 K-AKT, FOXO, and AMPK were targeted by the mentioned miRNA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis also showed high sensitivity and specificity of miR-182 as a marker for PCOS disorder [77]. In another study, we analyzed the expression levels of miR-21 and miR-93 in follicular fluids of normo- and hyper-androgenic PCOS in comparison with normal women. The above mentioned miRNAs were downregulated in follicular fluids of hyper-androgenic PCOS when compared with normo-androgenic group and also in PCOS (normo- and hyper-androgenic groups) in comparison with controls. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that important folliculogenesis signaling pathways, e.g., TGF-β, MAPK, WNT, insulin, and neurotrophin pathways, were involved by these miRNAs. As a predictive marker for distinction of PCOS from normal women, miR-21 had high specificity and sensitivity, and the combination of miR-93 and miR-21 increased the specificity but slightly decreased the sensitivity [82]. Xue et al. also performed Illumina deep sequencing on RNAs extracted from follicular fluids of PCOS and control women. They reported 263 differentially expressed miRNAs between the groups. Among the detected miRNAs, 86 miRNAs were downregulated, while 177 miRNAs were upregulated. Further, they detected 7 miRNAs which were reportedly correlated with PCOS, but their roles were unclear. Beyond these 7 miRNAs, 6 miRNAs were significantly upregulated in PCOS follicular fluids, while miR-105-3p was downregulated when compared with the normal group. Based on KEGG analysis, mTOR, TGF-β, insulin, MAPK, GnRH, and metabolic and oocyte maturation pathways were involved by these miRNAs [83] (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of detected follicular fluid miRNAs in correlation with infertility disorders

| miRNA(s) | Difference | Target pathway(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15a-5p | Young POR > normal | BAD and BCL2 | [87] |

| miR-483-5p | Young POR < normal | AKT, S6K1, and mTOR | [87] |

| miR-518f-3p | HA PCOS > NA PCOS | - | [56] |

| miR-151–3p | HA PCOS < NA PCOS | - | [56] |

| let-7b, miR-140; miR-29a, miR-574-3p, miR-24-3p, miR-151-3p; miR-320, miR-132; miR-105-3p; miR-486, miR-155, miR-146a | PCOS < normal | TGF-β and ERα; -; -; mTOR, TGF-β, MAPK, etc.; - | [8, 56, 63, 83, 84] |

| miR-30a; miR-182; miR-9, miR-135a, miR-34c-5p, miR-32, miR-18b; miR-125a-5p, miR-99a-3p, miR-200b-3p, miR-200a-3p, miR-29c-3p, miR-10b-3p; miR-370, miR-320 | PCOS > normal | -; PI3 K-Akt, FOXO, AMPK; IRS2, IL-8, SYT1; mTOR, TGF-β, MAPK, GnRH, etc. | [8, 77, 81, 83, 84] |

|

miR-21, miR-93 miR-222 |

HA PCOS < NA PCOS HA, NA PCOS < normal |

TGF-β, MAPK, WNT, insulin, neurotrophins | [82] |

| miR-203, miR-143, miR-191, miR-133, miR-29c, miR-766, miR-720 | Endometriosis > normal | - | [89] |

| miR-378, miR-223, miR-21, miR-145, miR-628, miR-23a, miR-1260, miR-663, miR-125a, miR-451, miR-542 | Endometriosis < normal | - | [89] |

Recently, in a careful prospective cohort study, follicular fluid miRNAs of 30 normal and 29 anovulatory PCOS with age and weight matched, but significant difference in ovarian reserve (antral follicle count (AFC) and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)) and androgen levels was analyzed. Among 176 detected miRNAs, 29 miRNAs had significant differences between the groups (with this manner, 12 of them were implicated in inflammatory, 12 in reproductive, and 6 in benign pelvic disease signaling pathways). MiR-425-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-93-3p, miR-199b-5p, miR-361-3p, miR-381-3p, and miR-382-5p were the top 7 miRNAs. MiR-382-5p was associated with free androgen index (FAI) of PCOS, while in the normal group, miR-381-3p was correlated with FAI [68] (Table 1). The two distinguished FAI-related miRNAs in PCOS and normal women indicate that the biomarker can be different depending on different situations and disorders, also for a unique factor. In this respect, recommended miRNAs for different considerations or aspects (e.g., ART outcome, estradiol, AMH, and testosterone) may not be applicable for all conditions such as endometriosis, PCOS, and normal women. Thus, future analyses are required to evaluate reported miRNA correlations with mentioned factors in different groups.

The newest study of finding PCOS-related miRNAs was performed by Cirillo et al. and indicated that insulin sensitivity related miRNAs were dysregulated in follicular fluids of PCOS patients [84]. Among the miRNAs that were related to inflammation and insulin sensitivity, miR-486, miR-155, and miR-146a were downregulated, whereas miR-370 and miR-320 were upregulated in follicular fluids of PCOS patients. They reported that the mentioned miRNAs were correlated with insulin, E2, BMI, and IL-6 [84] (Table 3). In contrast to the report of upregulation of miR-320 in PCOS follicular fluids [84], Sang and colleagues noted that miR-320 was in positive correlation with estradiol concentration and downregulated in PCOS follicular fluids [63]. This controversy may be due to the different ethnics, or small sample sizes, and requires more research in larger sample size to characterize the desired miRNA relationship with PCOS disorder.

To conclude, by interpreting the studies that have been conducted on PCOS-related miRNAs, most discovered miRNAs were involved in three main signaling pathways, androgen, inflammation, and insulin sensitivity. Thus, by focusing on these pathways, future studies can find more biomarkers that may have more sensitivity and specificity for PCOS diagnosis.

Studies in discovering follicular fluid miRNAs have been developed into other ovarian-related disorders as well. For instance, since the main cause of poor ovarian response is follicular atresia [85, 86], it seems reasonable that cell cycle correlated miRNAs would be dysregulated in patients’ ovaries. Zhang and colleagues proved that B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) and BCL2-antagonist of cell death (BAD) (two important cell cycle regulatory pathways) targeted miRNAs were dysregulated in follicular fluids of the patients as well [87]. They compared miRNA profile in follicular fluids of young (25–35 years old) and old (> 40 years old) poor responders with normal ovarian reserve women. The results demonstrated that miR-15a-5p was significantly overexpressed, while miR-483-5p was downregulated in follicular fluids of young poor responders (but not old poor responders). MiR-15a-5p causes downregulation and upregulation of BCL2 and BAD, respectively. MiR-483-5p is also involved in protein kinase B (AKT), S6K1, and mTOR signaling pathways [87] (Table 3). Thus, it can be concluded that upregulation of apoptosis (like BAD) targeted miRNAs and downregulation of the proliferation (like BCL2, AKT-PI3K, mTOR) targeted miRNAs can induce cumulus and granulosa cell apoptosis, decreasing the oocyte supports during folliculogenesis and ultimately triggering the follicle atresia, the main cause of the disorder.

As with endometriosis-related miRNAs, several excellent studies have been performed and have been recently reviewed in an efficient article [88]. Based on our search, only one study was found to evaluate the miRNAs in follicular fluids of endometriosis patients which was performed by Li et al. [89]. They analyzed embryo quality related miRNAs in follicular fluids of patients with stage III/IV of endometriosis. Among candidate miRNAs, 7 miRNAs were upregulated, while 11 miRNAs were downregulated in follicular fluids of patients in comparison with normal women. Since among differentially expressed miRNAs, only the downregulation of miR-451 was significant, they decided to evaluate the function of desired miRNA in oocytes. In this respect, they injected miR-451 inhibitor to oocytes of humans and mice. The results showed that rates of fertilization and embryo formation (from 2-cell to blastocyst stage) were negatively affected in the miR-451 inhibitor injected group. Moreover, expression levels of WNT signaling pathway molecules such as CTNNB1, CDX2, and AXIN1 were reduced in the regarded group. They finally concluded that the reduction of miR-451 in follicular fluids of endometriosis patients could diminish the fertilization and embryo quality via affecting on the WNT signaling pathway [89] (Table 3). One positive contribution that is made by this study was the inspection of the endometriosis-related miRNAs among miRNAs that were correlated with embryo quality. In this case, the identified biomarker cannot only be applied for the diagnosis of disorder but also ART outcome.

All in all, several efficient miRNAs in correlation with ovarian diseases have been introduced that we summarized them in this section. However, since small populations were included in the studies, admittance of reported miRNAs as biomarkers requires investigating in larger populations, especially in varied ethnics. Thus, the expansion of ahead evaluations is required in order to incorporate applicable biomarkers in female reproductive disorders.

Conclusion and future perspectives

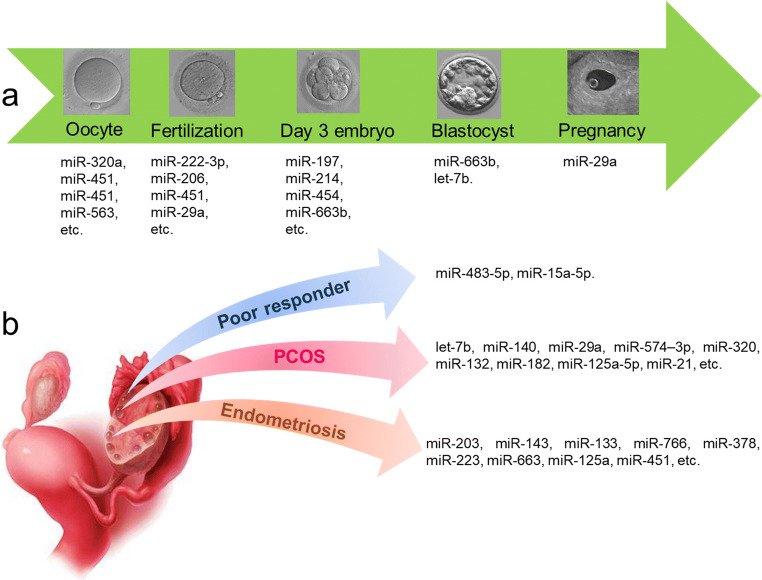

MiRNA studies, due to their crucial and mostly undiscovered roles in pathophysiology of disorders, have been spread in different fields of research. Using them as biomarkers, especially in body fluids as less or noninvasive samples, can help the better diagnosis and open new doors of therapies, miRNA targeting therapy, in the long term. Biomarker importance in ART is not only for oocyte and embryo quality assessments but also infertility disease diagnosis. Recently, follicular fluid as a rich source for biomarkers has attracted scientists’ attentions. Although miRNA biomarkers in follicular fluid with ART aspect are in their initial stages, several meticulously studies have been performed and underscored in this review (summarized in Fig. 1). In conclusion, miR-508-3p has been proved as a specific follicular fluid miRNA that is not present in plasma [64]. Since blood contamination during follicle aspiration is feasible, assessment of miR-508-3p functions in various pathways and its potential as being a follicular fluid-specific biomarker for different situations is recommended.

Fig. 1.

Summary of follicular fluid miRNAs that correlated with ART outcome (a) and female reproductive disease (b)

On the other hand, some miRNA roles have been accepted by several studies. For instance, miR-663b inverse correlation with embryo quality has been approved by two distinct studies [10, 71] and thus can be suggested as a reliable candidate for embryo quality biomarker. Some miRNA functions have also been assessed from different aspects (Fig. 2). As evidenced by analyses, increased and decreased levels of miR-29a in follicular fluid have been reported to be associated with clinical pregnancy and PCOS disease, respectively [8, 56]. Although the two reported roles may be in similar respect, there are some controversies for some miRNAs such as miR-454 which has been shown to be related positively with both abnormal fertilization and top quality embryos [9, 10]. On the other hand, some reported miRNAs in one study could not be detected by other groups [63, 81]. These controversies may be due to the different applied methods for miRNA isolation and reveal the need of a standard method for follicular fluid miRNA extraction.

Fig. 2.

Follicular fluid miRNAs with multiple effects

Focus on involved pathways by miRNAs revealed that TGF-β, MAPK, mTOR, and p53 were the most common targets of detected follicular fluid miRNAs. Members of TGF-β superfamily (e.g., follistatin, activin, and BMP) are essential for different stages of follicle development, oocyte maturation, and ovulation [64, 90]. TGF-β dysregulation can result in female reproduction defects such as PCOS as well [91, 92]. Studies indicated that detected miRNAs could influence fertilization, embryo quality, and PCOS pathogenesis by targeting TGF-β pathway. MAPK signaling pathway regulates oocyte maturation via proliferation and expansion of granulosa and cumulus cells, respectively [93]. It also reduces cAMP levels in oocytes and stimulates meiosis resumption [94, 95]. Since accumulation of many immature follicles is related to PCOS pathogenesis, it seems reasonable that many reported miRNAs in PCOS patients were involved in MAPK pathway. MTOR signaling is another important pathway in female reproduction. It is involved in steroidogenesis, primordial follicle activation, oocyte maturation, and ovarian aging [96] and was targeted by reported miRNAs, especially in fertilization, embryo quality, and PCOS. P53 pathway plays a vital role in controlling cell cycle and apoptosis [97]. Interestingly, it was targeted by miRNAs that were correlated with embryo quality.

The above mentioned pathways that were frequently targeted by detected miRNAs prove the crucial roles of follicular fluid miRNAs in follicle development and female fertility potential.

Overall, practical studies have been performed, but more are required for miRNA profiling in follicular fluid, especially in endometriosis, POF, and also pregnancy chance, the main goal of ART. Exploring biomarkers is an immediate need in ART, and the research ahead may meet that need.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tesfaye D, Salilew-Wondim D, Gebremedhn S, Sohel MMH, Pandey HO, Hoelker M, Schellander K. Potential role of microRNAs in mammalian female fertility. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2017;29(1):8–23. doi: 10.1071/RD16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silveira JC, de Andrade GM, Nogueira MFG, Meirelles FV, Perecin F. Involvement of miRNAs and cell-secreted vesicles in mammalian ovarian antral follicle development. Reprod Sci. 2015;22(12):1474–1483. doi: 10.1177/1933719115574344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesfaye D, Gebremedhn S, Salilew-Wondim D, Hailay T, Hoelker M, Grosse-Brinkhaus C, Schellander K. MicroRNAs: tiny molecules with a significant role in mammalian follicular and oocyte development. Reproduction. 2018;155(3):R121–R135. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohel MMH, Hoelker M, Noferesti SS, Salilew-Wondim D, Tholen E, Looft C, Rings F, Uddin MJ, Spencer TE, Schellander K, Tesfaye D. Exosomal and non-exosomal transport of extra-cellular microRNAs in follicular fluid: implications for bovine oocyte developmental competence. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salilew-Wondim D, Gebremedhn S, Hoelker M, Tholen E, Hailay T, Tesfaye D. The role of microRNAs in mammalian fertility: from gametogenesis to embryo implantation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(2):585. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kropp J, Salih SM, Khatib H. Expression of microRNAs in bovine and human pre-implantation embryo culture media. Front Genet. 2014;5:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andronico F, Battaglia R, Ragusa M, Barbagallo D, Purrello M, di Pietro C. Extracellular vesicles in human oogenesis and implantation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2162. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scalici E, Traver S, Mullet T, Molinari N, Ferrières A, Brunet C, Belloc S, Hamamah S. Circulating microRNAs in follicular fluid, powerful tools to explore in vitro fertilization process. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24976. doi: 10.1038/srep24976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez RM, Liang L, Racowsky C, Dioni L, Mansur A, Adir M, Bollati V, Baccarelli AA, Hauser R, Machtinger R. Extracellular microRNAs profile in human follicular fluid and IVF outcomes. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17036. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35379-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machtinger R, Rodosthenous RS, Adir M, Mansour A, Racowsky C, Baccarelli AA, Hauser R. Extracellular microRNAs in follicular fluid and their potential association with oocyte fertilization and embryo quality: an exploratory study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(4):525–533. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0876-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbar T, Eisenberg I. Regulatory role of microRNAs in ovarian function. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(6):1524–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacFarlane L-A. and P. R Murphy, MicroRNA: biogenesis, function and role in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(7):537–561. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohel MH. Extracellular/circulating microRNAs: release mechanisms, functions and challenges. Achiev Life Sci. 2016;10(2):175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu W, Xu Y, Xie X, Wang T, Ko JH, Zhou T. The role of RNA structure at 5′ untranslated region in microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Rna. 2014;20(9):1369–1375. doi: 10.1261/rna.044792.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ender C, Meister G. Argonaute proteins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(11):1819–1823. doi: 10.1242/jcs.055210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broughton JP, Lovci MT, Huang JL, Yeo GW, Pasquinelli AE. Pairing beyond the seed supports microRNA targeting specificity. Mol Cell. 2016;64(2):320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasudevan S. Posttranscriptional upregulation by microRNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3(3):311–330. doi: 10.1002/wrna.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Wu X, Qian W, Cai H, Sun X, Zhang W, Tan S, Wu Z, Qian P, Ding K, Lu X, Zhang X, Yan H, Song H, Guang S, Wu Q, Lobie PE, Shan G, Zhu T. CCAR1 5′ UTR as a natural miRancer of miR-1254 overrides tamoxifen resistance. Cell Res. 2016;26(6):655–673. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geekiyanage H, Jicha GA, Nelson PT, Chan C. Blood serum miRNA: non-invasive biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 2012;235(2):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiino S, Matsuzaki J, Shimomura A, Kawauchi J, Takizawa S, Sakamoto H, Aoki Y, Yoshida M, Tamura K, Kato K, Kinoshita T, Kitagawa Y, Ochiya T. Serum miRNA–based prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(6):1817–1827. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caglar O, Cayir A. Total circulating cell-free miRNA in plasma as a predictive biomarker of the thyroid diseases. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(6):9016–9022. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell AJ, Gray WD, Hayek SS, Ko YA, Thomas S, Rooney K, Awad M, Roback JD, Quyyumi A, Searles CD. Platelets confound the measurement of extracellular miRNA in archived plasma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32651. doi: 10.1038/srep32651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks SD, Johnson J, Carney MC, Bramley H, Olympia RP, Loeffert AC, Thomas NJ. Overlapping microRNA expression in saliva and cerebrospinal fluid accurately identifies pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(1):64–72. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapado-González Ó, Majem B, Álvarez-Castro A, Díaz-Peña R, Abalo A, Suárez-Cabrera L, Gil-Moreno A, Santamaría A, López-López R, Muinelo-Romay L, Suarez-Cunqueiro MM. A novel saliva-based miRNA signature for colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):2029. doi: 10.3390/jcm8122029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelloni M, Coltrinari G, Paoli D, Pallotti F, Lombardo F, Lenzi A, Gandini L. Differential expression of miRNAs in the seminal plasma and serum of testicular cancer patients. Endocrine. 2017;57(3):518–527. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1150-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radtke A, Dieckmann KP, Grobelny F, Salzbrunn A, Oing C, Schulze W, Belge G. Expression of miRNA-371a-3p in seminal plasma and ejaculate is associated with sperm concentration. Andrology. 2019;7(4):469–474. doi: 10.1111/andr.12664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marí-Alexandre J, et al. Micro-RNA profile and proteins in peritoneal fluid from women with endometriosis: their relationship with sterility. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(4):675–684.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohzawa, Hideyuki, et al. Exosomal microRNA profiles in peritoneal fluids as a therapeutic biomarker for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. 2018;5393–5393

- 31.Royo F, Diwan I, Tackett M, Zuñiga P, Sanchez-Mosquera P, Loizaga-Iriarte A, Ugalde-Olano A, Lacasa I, Perez A, Unda M, Carracedo A, Falcon-Perez J. Comparative miRNA analysis of urine extracellular vesicles isolated through five different methods. Cancers. 2016;8(12):112. doi: 10.3390/cancers8120112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catapano F, Domingos J, Perry M, Ricotti V, Phillips L, Servais L, Seferian A, Groot I, Krom YD, Niks EH, Verschuuren JJGM, Straub V, Voit T, Morgan J, Muntoni F. Downregulation of miRNA-29,-23 and-21 in urine of Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Epigenomics. 2018;10(7):875–889. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller M, Jäkel L, Bruinsma IB, Claassen JA, Kuiperij HB, Verbeek MM. MicroRNA-29a is a candidate biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease in cell-free cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(5):2894–2899. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akers JC, Hua W, Li H, Ramakrishnan V, Yang Z, Quan K, Zhu W, Li J, Figueroa J, Hirshman BR, Miller B, Piccioni D, Ringel F, Komotar R, Messer K, Galasko DR, Hochberg F, Mao Y, Carter BS, Chen CC. A cerebrospinal fluid microRNA signature as biomarker for glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(40):68769–68779. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Silveira JC, Veeramachaneni DN, Winger QA, Carnevale EM, Bouma GJ. Cell-secreted vesicles in equine ovarian follicular fluid contain miRNAs and proteins: a possible new form of cell communication within the ovarian follicle. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(3):71. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O'Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(30):10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Pol E, et al. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(3):676–705. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beyer C, Pisetsky DS. The role of microparticles in the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(1):21–29. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Tréguer K, Boettger T, Horrevoets AJG, Zeiher AM, Scheffer MP, Frangakis AS, Yin X, Mayr M, Braun T, Urbich C, Boon RA, Dimmeler S. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(3):249–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turiák L, Misják P, Szabó TG, Aradi B, Pálóczi K, Ozohanics O, Drahos L, Kittel Á, Falus A, Buzás EI, Vékey K. Proteomic characterization of thymocyte-derived microvesicles and apoptotic bodies in BALB/c mice. J Proteome. 2011;74(10):2025–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akao Y, Iio A, Itoh T, Noguchi S, Itoh Y, Ohtsuki Y, Naoe T. Microvesicle-mediated RNA molecule delivery system using monocytes/macrophages. Mol Ther. 2011;19(2):395–399. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaiswal R, Gong J, Sambasivam S, Combes V, Mathys JM, Davey R, Grau GER, Bebawy M. Microparticle-associated nucleic acids mediate trait dominance in cancer. FASEB J. 2012;26(1):420–429. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shantsila E, Kamphuisen P, Lip G. Circulating microparticles in cardiovascular disease: implications for atherogenesis and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2358–2368. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aharon A, et al. Microparticles bearing tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in gestational vascular complications. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(6):1047–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee Y, El Andaloussi S, Wood MJ. Exosomes and microvesicles: extracellular vesicles for genetic information transfer and gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(R1):R125–R134. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteome. 2010;73(10):1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int. 2010;78(9):838–848. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson RJ, Kalra H, Mathivanan S. ExoCarta as a resource for exosomal research. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2012;1(1):18374. doi: 10.3402/jev.v1i0.18374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng L, Sharples RA, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF. Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3(1):23743. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.23743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buck AH, Coakley G, Simbari F, McSorley HJ, Quintana JF, le Bihan T, Kumar S, Abreu-Goodger C, Lear M, Harcus Y, Ceroni A, Babayan SA, Blaxter M, Ivens A, Maizels RM. Exosomes secreted by nematode parasites transfer small RNAs to mammalian cells and modulate innate immunity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5488. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(16):7223–7233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Babin PJ, Gibbons GF. The evolution of plasma cholesterol: direct utility or a “spandrel” of hepatic lipid metabolism? Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48(2):73–91. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niculescu LS, Simionescu N, Sanda GM, Carnuta MG, Stancu CS, Popescu AC, Popescu MR, Vlad A, Dimulescu DR, Simionescu M, Sima AV. MiR-486 and miR-92a identified in circulating HDL discriminate between stable and vulnerable coronary artery disease patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabet F, Vickers KC, Cuesta Torres LF, Wiese CB, Shoucri BM, Lambert G, Catherinet C, Prado-Lourenco L, Levin MG, Thacker S, Sethupathy P, Barter PJ, Remaley AT, Rye KA. HDL-transferred microRNA-223 regulates ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sørensen AE, Wissing ML, Englund ALM, Dalgaard LT. MicroRNA species in follicular fluid associating with polycystic ovary syndrome and related intermediary phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(4):1579–1589. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hossain M, et al. Characterization and importance of microRNAs in mammalian gonadal functions. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349(3):679–690. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kenigsberg S, Wyse BA, Librach CL, da Silveira JC. Protocol for exosome Isolation from small volume of ovarian follicular fluid: Evaluation of ultracentrifugation and commercial kits. InExtracellular Vesicles 2017 (pp. 321-341). Humana Press, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Duy J, Koehler JW, Honko AN, Minogue TD. Optimized microRNA purification from TRIzol-treated plasma. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan GW, Khoo ASB, Tan LP. Evaluation of extraction kits and RT-qPCR systems adapted to high-throughput platform for circulating miRNAs. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9430. doi: 10.1038/srep09430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright K, et al. Comparison of methods for miRNA isolation and quantification from ovine plasma. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57659-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mariani G, Bellver J. Proteomics and metabolomics studies and clinical outcomes. InReproductomics 2018 Jan 1 (pp. 147-170). Academic Press.

- 63.Sang Q, Yao Z, Wang H, Feng R, Wang H, Zhao X, Xing Q, Jin L, He L, Wu L, Wang L. Identification of microRNAs in human follicular fluid: characterization of microRNAs that govern steroidogenesis in vitro and are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):3068–3079. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santonocito M, et al. Molecular characterization of exosomes and their microRNA cargo in human follicular fluid: bioinformatic analysis reveals that exosomal microRNAs control pathways involved in follicular maturation. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(6):1751–1761. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Battaglia R, Vento ME, Borzì P, Ragusa M, Barbagallo D, Arena D, Purrello M, di Pietro C. Non-coding RNAs in the ovarian follicle. Front Genet. 2017;8:57. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mencaglia L, Cerboneschi M, Ciociola F, Ricci S, Mancioppi I, Ambrosino V, Ferrandi C, Strozzi F, Piffanelli P, Grasselli A. Characterization of microRNA in the follicular fluid of patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2019;33(3):946–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreno JM, et al. Follicular fluid and mural granulosa cells microRNA profiles vary in in vitro fertilization patients depending on their age and oocyte maturation stage. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):1037–1046. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler AE, Ramachandran V, Hayat S, Dargham SR, Cunningham TK, Benurwar M, Sathyapalan T, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Atkin SL. Expression of microRNA in follicular fluid in women with and without PCOS. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16306. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52856-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng R, Sang Q, Zhu Y, Fu W, Liu M, Xu Y, Shi H, Xu Y, Qu R, Chai R, Shao R, Jin L, He L, Sun X, Wang L. MiRNA-320 in the human follicular fluid is associated with embryo quality in vivo and affects mouse embryonic development in vitro. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8689. doi: 10.1038/srep08689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mulner-Lorillon O, Chassé H, Morales J, Bellé R, Cormier P. MAPK/ERK activity is required for the successful progression of mitosis in sea urchin embryos. Dev Biol. 2017;421(2):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fu J, Qu RG, Zhang YJ, Gu RH, Li X, Sun YJ, Wang L, Sang Q, Sun XX. Screening of miRNAs in human follicular fluid reveals an inverse relationship between microRNA-663b expression and blastocyst formation. Reprod BioMed Online. 2018;37(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X-D, Zhang YH, Ling YH, Liu Y, Cao HG, Yin ZJ, Ding JP, Zhang XR. Characterization and differential expression of microRNAs in the ovaries of pregnant and non-pregnant goats (Capra hircus) BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xia HF, Jin XH, Cao ZF, Hu Y, Ma X. Micro RNA expression and regulation in the uterus during embryo implantation in rat. FEBS J. 2014;281(7):1872–1891. doi: 10.1111/febs.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karakas SE. New biomarkers for diagnosis and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;471:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Broekmans F, Knauff EAH, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BCJM. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113(10):1210–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu T, Fang Y, Rong A, Wang J. Flexible combination of multiple diagnostic biomarkers to improve diagnostic accuracy. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0085-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Naji M, Nekoonam S, Aleyasin A, Arefian E, Mahdian R, Azizi E, Shabani Nashtaei M, Amidi F. Expression of miR-15a, miR-145, and miR-182 in granulosa-lutein cells, follicular fluid, and serum of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(1):221–231. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4570-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Long W, Zhao C, Ji C, Ding H, Cui Y, Guo X, Shen R, Liu J. Characterization of serum microRNAs profile of PCOS and identification of novel non-invasive biomarkers. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33(5):1304–1315. doi: 10.1159/000358698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen B, Xu P, Wang J, Zhang C. The role of MiRNA in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Gene. 2019 Jul 20;706:91–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Shi Y, Zhao H, Shi Y, Cao Y, Yang D, Li Z, Zhang B, Liang X, Li T, Chen J, Shen J, Zhao J, You L, Gao X, Zhu D, Zhao X, Yan Y, Qin Y, Li W, Yan J, Wang Q, Zhao J, Geng L, Ma J, Zhao Y, He G, Zhang A, Zou S, Yang A, Liu J, Li W, Li B, Wan C, Qin Y, Shi J, Yang J, Jiang H, Xu JE, Qi X, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Hao C, Ju X, Zhao D, Ren CE, Li X, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wu D, Zhang C, He L, Chen ZJ. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new risk loci for polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):1020–1025. doi: 10.1038/ng.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roth LW, McCallie B, Alvero R, Schoolcraft WB, Minjarez D, Katz-Jaffe MG. Altered microRNA and gene expression in the follicular fluid of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(3):355–362. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Naji M, Aleyasin A, Nekoonam S, Arefian E, Mahdian R, Amidi F. Differential expression of miR-93 and miR-21 in granulosa cells and follicular fluid of polycystic ovary syndrome associating with different phenotypes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14671. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue Y, Lv J, Xu P, Gu L, Cao J, Xu L, Xue K, Li Q. Identification of microRNAs and genes associated with hyperandrogenism in the follicular fluid of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(5):3913–3921. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cirillo F, Catellani C, Lazzeroni P, Sartori C, Nicoli A, Amarri S, la Sala GB, Street ME. MiRNAs regulating insulin sensitivity are dysregulated in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) ovaries and are associated with markers of inflammation and insulin sensitivity. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:879. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jirge PR. Poor ovarian reserve. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2016;9(2):63–69. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.183514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luo H, Han Y, Liu J, Zhang Y. Identification of microRNAs in granulosa cells from patients with different levels of ovarian reserve function and the potential regulatory function of miR-23a in granulosa cell apoptosis. Gene. 2019;686:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang K, Zhong W, Li WP, Chen ZJ, Zhang C. miR-15a-5p levels correlate with poor ovarian response in human follicular fluid. Reproduction. 2017;154(4):483–496. doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bjorkman S, Taylor HS. microRNAs in endometriosis: biological function and emerging biomarker candidates. Biol Reprod. 2019;100(5):1135–1146. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li X, Zhang W, Fu J, Xu Y, Gu R, Qu R, Li L, Sun Y, Sun X. MicroRNA-451 is downregulated in the follicular fluid of women with endometriosis and influences mouse and human embryonic potential. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0538-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Piotrowska H, Kempisty B, Sosinska P, Ciesiolka S, Bukowska D, Antosik P, Rybska M, Brussow KP, Nowicki M, Zabel M. The role of TGF superfamily gene expression in the regulation of folliculogenesis and oogenesis in mammals: a review. Veterinarni Medicina. 2013 Oct 1;58(10).

- 91.Raja-Khan N, Urbanek M, Rodgers RJ, Legro RS. The role of TGF-β in polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(1):20–31. doi: 10.1177/1933719113485294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li Y, Xiang Y, Song Y, Wan L, Yu G, Tan L. Dysregulated miR-142, -33b and -423 in granulosa cells target TGFBR1 and SMAD7: a possible role in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Hum Reprod. 2019;25(10):638–646. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaz014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conti M, Hsieh M, Musa Zamah A, Oh JS. Novel signaling mechanisms in the ovary during oocyte maturation and ovulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;356(1-2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Russell DL, Robker RL. Molecular mechanisms of ovulation: co-ordination through the cumulus complex. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(3):289–312. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang M, Ouyang H, Xia G. The signal pathway of gonadotrophins-induced mammalian oocyte meiotic resumption. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15(7):399–409. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guo Z, Yu Q. Role of mTOR signaling in female reproduction. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2019;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ, Strasser A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(1):104–113. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]