Abstract

Chickpea being a winter season crop often experiences heat stress during reproductive phase. For chickpea production, terminal heat stress is one of the major constraints. Plants have built up numerous mechanisms to combat the heat stress. We considered the photosynthetic pigments for heat tolerance. Therefore, in order to investigate the heat tolerance in relation to photosynthetic pigments, a field trial was carried out having 4 contrasting genotypes namely BG 240 and JG 14 (relatively heat tolerant), SBD 377 (moderately tolerant) and ICC 1882 (relatively heat sensitive). Heat stress was imposed by altering the sowing date i.e. normal (18th November) and late sown (18th December). Under delayed sown condition, heat stress was faced by crop starting from flowering stage to crop maturity. Under heat stress condition, heat tolerant genotypes BG 240 and JG 14 maintained higher level of membrane stability, RWC (%), osmolytes, dry matter partitioning, grain yield, heat tolerance index and had higher values of zeaxanthin, quantum yield of PS II (Fv/Fm ratio), non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), photosynthetic rate, level of photosynthetic pigments (chlorophylls and carotenoids) and lower level of violaxanthin, and lipid peroxidation as compared to heat sensitive one (ICC 1882). In addition to this, Fv/Fm ratio and NPQ exhibited positive relationship with heat tolerance which suggested the involvement of xanthophyll cycle pigments in chickpea heat tolerance.

Keywords: Chickpea, Heat tolerance, Photosynthetic pigments, Non-photochemical quenching, Zeaxanthin

Introduction

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) is an imperative pulse crop, rich in protein by virtue of N2 fixation. Seeds of chickpea have 23% protein, 64% carbohydrates, 5% fat, 6% crude fiber, 6% soluble sugar, and 3% ash (Williams and Singh 1987). It is extensively grown in the world covering over 50 countries of Asia, Africa, Europe, Australia, North America and South America. Globally after common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), chickpea is the second most important food legume crop (Dixit et al. 2019). India contributes a major share to the global chickpea area (70%) and production (67%) and continues to be the biggest chickpea-producing nation. However, being a cool season crop, it is vulnerable to high temperatures (≥ 35 °C), especially at the reproductive stage (Young et al. 2004; Devasirvatham et al. 2012a, b). In India, due to delay in harvest of previous crops such as sugarcane, rice and maize, late sown chickpea gets exposed to high temperature of the summer, during grain filling, results in poor grain yield. Furthermore, the area of chickpea under late-sown conditions is increasing particularly in northern and central India. According to an estimate, in north India, chickpea grain yield in Uttar Pradesh decreased by 53 kg ha–1 and 301 kg ha–1 in Haryana per 1 °C increase in seasonal temperature (Kalra et al. 2008). Heat stress directly affects photosynthesis including photosystem II in chickpea (Srinivasan et al. 1996). The rate of photosynthesis has a negative linear association with temperature. Peak photosynthetic rate is recorded at suboptimal temperatures (22 °C) in chickpea and transpiration efficiency (photosynthesis/transpiration) of chickpea decreases with increasing temperature (Devasirvatham et al. 2012b). Short periods of high temperature (> 35 °C) during early flowering and pod development stage of chickpea cause significant reduction in pod, seed- set and yield (Wang et al. 2006).

To combat the detrimental effects of heat stress, plants have developed several mechanisms which ultimately lead to morphological, physiological, and biochemical alterations (Lamaoui et al. 2018). Our interest was to consider the photosynthetic pigments for heat tolerance. Leaf carotenoids protect photosynthetic machinery and improve heat tolerance by scavenging ROS, quenching triplet chlorophyll and dissipating excess energy via zeaxanthin-mediated NPQ under heat stress (Xiong et al. 2012; Esteban et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2015; Trojak and Skowron 2017). Therefore, during the present study, an attempt was made to gain insight into the photosynthetic pigments modulated mechanism of heat tolerance in chickpea.

Materials and methods

An experiment was conducted in factorial randomized block design with three replicates at IARI research farm, New Delhi for two consecutive years using 4 selected contrasting genotypes namely BG 240 and JG 14 (relatively high temperature tolerant), SBD 377 (moderately tolerant) and ICC 1882 (relatively high temperature sensitive) which were selected from a set of 56 genotypes based on yield indices after screening them for heat tolerance. Their seeds were obtained from Division of Genetics, IARI, New Delhi. High temperature was imposed during reproductive/terminal phase of crop by altering the sowing dates i.e. normal sowing (18th November) and one month late to normal sown (18th December). Daily weather data were recorded for the entire crop duration. During the present study, the physiological observations were recorded at flowering and podding stages while biomass and yield traits at harvest.

Photosynthetic rate

Observations on leaf photosynthesis were recorded on fully developed 4th leaf from the top by using LI-COR portable photosynthesis system (IRGA LI-6400 model, LI-COR, Nebaraska, USA) between 10.00 AM and 11.30 AM during clear day by providing artificial light source 1000 µmol m−2 s−1. The rate of photosynthesis (µmol CO2 m−2 s−1) and stomatal conductance (mmol H2O m−2 s−1) were recorded by operating the Infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) in the closed mode.

Chlorophylls and carotenoids content

Chlorophyll and carotenoids content were measured as per the method described by Hiscox and Israelstam (1979). The procedure for estimation of chlorophyll content in plants is based on the absorption of light by chlorophyll extracts prepared by incubating the leaf tissues in DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). DMSO makes plasmalemma permeable thus, causing the leaching of the pigments. The absorbance of the known volume of solution containing known quantity of leaf tissue at two respective wavelengths (663 and 645) was determined for chlorophyll content and at 480 nm for total carotenoid contents. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and total chlorophyll content were estimated using the formula given by Arnon (1949) while carotenoids content was determined by following the formula given by Lichtenthaler and Welburn (1983). Thirty mg fresh leaf samples were added to the test tubes containing 4 ml DMSO. Tubes were kept in dark for 4 h at 65 °C. Then the samples were taken out cooled at room temperature and the absorbance was recorded at 663, 645 and 480 nm using DMSO as blank and was expressed as mg g−1 dry wt.

where A663 Absorbance at 663 nm, A645 Absorbance at 645 nm, A480 Absorbance at 480 nm, W Weight of the sample in g, V Volume of the solvent used (ml).

Photosynthetic pigments profiling using thin layer chromatography (TLC)

Separation of pigments by TLC was done according to the method described by Pocock et al. (2004) with minor modifications.

Extraction of leaf pigments

Fresh leaves (4 g) were grinded in a mortar with the help of pestle using 20 ml acetone, 3 ml petroleum ether and little quantity of calcium carbonate. The homogenate was filtered through whatman filter paper No. 1. Then this filtrate was transferred to a separating funnel and 5% NaCl and 5 ml petroleum ether were added to it. The mixture in a separating funnel was shaken carefully and was partitioned using separating funnel. The upper layer was collected and washed three to four times with double distilled water. The final extract was evaporated in a cool and dark place and the volume was made up to 2 ml using acetone.

Application of extract to the TLC plate

The TLC plates were kept in the oven for 3–4 h at 90–100 °C in order to remove any traces of moisture present in it. Then a TLC plate was taken from oven and a line was drawn on the plate with pencil (1.5 cm above bottom) and the extract was applied on it. The spot was dried thoroughly. Then the plate was kept in the TLC chamber consisting of petroleum ether, acetone and distilled water based solvent system as described elsewhere (Pocock et al. 2004) with little modifications. The chromatogram was removed when the solvent went 15 cm above from the origin and it was immediately photographed. For the identification of the different photosynthetic pigments, bands of pigments from TLC plate were scratched and eluted using acetone by centrifuging at 3000 g for 10 min. Then the spectra of each band were drawn with the help of UV–Visible spectrophotometer. Thus, based on photosynthetic pigments standards (Sigma Chem Pvt Ltd), the spectra and Rf values, photosynthetic pigments were identified.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were performed using the Junior-PAM fluorometer (Heinz Walz, Germany). The leaf clips were attached on the flag leaves 20 min prior to the measurements to provide dark adaptation. After that, samples were illuminated to take light adapted records on chlorophyll fluorescence. The maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm), and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) were estimated according to Demmig-Adams et al. (1996).

Relative water content

Relative water content was estimated using the method of Weatherly (1950). Leaf related water content (RWC) was estimated using fully expanded third or fourth leaf from the top by recording the turgid weight of 0.5 g fresh leaf sample by keeping in distilled water for 4 h, followed by drying in hot air oven at 70 °C until constant dry weight was attained. RWC (%) was calculated by using the following formula:

where FW fresh weight (g), TW turgid weight (g), DW dry weight (g).

Membrane stability index (MSI)

For estimating membrane stability, conductivity tests were carried out by using the method as described earlier (Blum and Ebercon 1981). 100 mg leaf tissue of fully expanded fourth leaf from the top was weighed in three replicates and placed in a test tube containing 10 ml of double distilled de-ionized water. These tubes were incubated at 40 °C for half an hour in a water bath. Then initial electrical conductivity (C1) of this solution was measured with the help of conductivity meter. These test tubes were kept in boiling water at 100 °C for 10 min and cooled at room temperature and final electrical conductivity (C2) was measured again. Percent conductivity was used to calculate membrane stability index using following formula:

where C1 is initial electrical conductivity (µS) at test temperature (40 °C), C2 is final electrical conductivity (µS) at 100 °C.

Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was estimated as the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, using the method of Heath and Packer (1968). Leaf samples (0.5 g) were homogenized in 10 ml 0.1% trichloro-acetic acid (TCA). Then homogenate was centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 g. To 1.0 ml aliquot of the supernatant, 4.0 ml of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in 20% TCA was added. The mixture was heated at 95 ºC for 30 min in the water bath and then cooled under room temperature. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min, the absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 532 nm. The TBARS content was calculated according to its extinction coefficient, i.e., 155 mM−1 cm−1. The values for non-specific absorbance at 600 nm were subtracted (Heath and Packer 1968).

Post harvest observations

Post harvest observations viz. plant height, root length, number of main branches per plant, secondary branches per plant, pod number per plant, pod weight per plant, seed number per plant, grain yield per hectare, total dry matter (TDM) per hectare and 1000 seed weight were recorded at harvest.

Harvest index

Harvest index (HI) was calculated by using the following formula:

Dry matter partitioning

At harvest, dry matter partitioning was calculated using following formula

Yield and yield indices

Yield and its attributes were recorded at harvest. Heat susceptibility index (HSI), heat tolerance index (HTI) and heat intensity index (HII) were calculated using the formula described earlier by Porch (2006).

where Ys and Yp indicate genotypic yield under stress and non-stressed conditions respectively and Xs and Xp are the mean yield of all genotypes per trial under stress and non stress condition.

Heat yield stability index (HYSI) was calculated using the following formula given by (Bouslama, and Schapaugh, 1984).

Results and discussion

Variation in weather

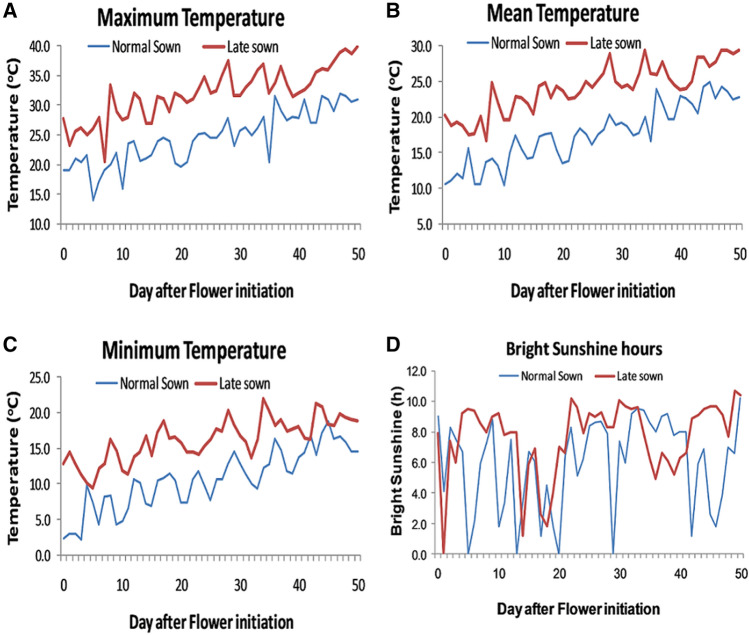

High temperature was coincided with starting from flowering stage to crop maturity under the delayed sown condition. Under timely sown condition, maximum temperature (Fig. 1a) starting from flowering stage to crop maturity was recorded between 20 and 30 °C while under delayed sown heat stress condition, maximum temperature was varying from 25 to 39.9 °C. Starting from flowering stage to crop maturity, mean temperature under timely sown condition was recorded between 10 and 22 °C whereas mean temperature under delayed sown condition was varying between 20 and 29.4 °C (Fig. 1b). Similarly, minimum temperature under timely sown condition, starting from chickpea flowering to maturity was noted in the range of 3–17.2 °C while under delayed sown heat stress condition, minimum temperature was recorded in the range of 10–22 °C (Fig. 1c). Under normal sown condition, bright sunshine hours (Fig. 1d) from flowering to maturity were recorded between 0 and 9.2 h with mean value 5.9 h while under late sown heat stress condition, bright sunshine hours were varying in the range of 0–10.7 h with mean value 7.2 h which indicates that bright sunshine hours per day were relatively higher under late sown heat stress condition than normal sown one.

Fig. 1.

Maximum, mean & minimum temperature and sunshine hours recorded from flowering stage to crop maturity under both normal and late sown conditions

Physiological responses of chickpea genotypes to high temperature

Response of contrasting chickpea genotypes to high temperature was analyzed in terms of rate of photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments and their profile, chlorophyll florescence parameters, relative water content, membrane stability index (MSI), lipid peroxidation, level of osmolytes, growth, grain yield and its attributes, harvest index, heat susceptibility and heat tolerance index. Physiological and yield performance of contrasting chickpea genotypes recorded under normal and late sown heat stress conditions are as follows:

Photosynthetic rate

Significant genotypic variations in photosynthetic rate were traced under both timely and delayed sown condition. A significant diminution in photosynthetic rate was estimated under delayed sown condition particularly at podding stage. Relatively higher reduction in photosynthetic rate were noted in sensitive genotypes (ICC 1882 and SBD 377) than the relatively heat tolerant ones (BG 240 and JG 14). Tolerant genotypes maintained relatively higher rate of photosynthesis at both flowering and podding stages under high temperature condition (Fig. 2). Our results confirmed earlier reports made on photosynthesis in chickpea under heat stress condition (Devasirvatham et al., 2012a, b; Kumar et al. 2017). In chickpea, photosynthesis including photosystem II is directly affected by heat stress (Srinivasan et al. 1996). Photochemical reactions in thylakoids and carbon metabolism in the stroma of chloroplast have been advocated as the primary sites of injury under heat stress (Wise et al. 2004). Plants grown under high temperature stress condition reduce stomatal conductance (Kaushal et al. 2013) to save the water. Consequently, CO2 uptake is reduced and photosynthetic rate decreases that results in less assimilate production for growth and yield of plants (Wahid et al. 2007).

Fig. 2.

Effect of late sown high temperature stress condition on rate of photosynthesis (PN) in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Photosynthetic pigments

Total chlorophyll and total carotenoids contents

Similarly, total chlorophyll and total carotenoids contents exhibited the genotypic variability. Under delayed sown heat stress condition, significant reduction in total chlorophyll and carotenoids were noted and maximum reduction was recorded in ICC 1882 and SBD 377 (high temperature sensitive) genotype. Relatively heat tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) maintained higher level of total chlorophyll and total carotenoids under heat stress condition (Fig. 3) due to strong antioxidant system (Kaushal et al. 2011). In relatively sensitive genotypes, chlorophylls were diminished under heat stress due the hang-up of their synthesis and oxidation caused by reactive oxygen species (Van Hasselt and Strikwerda 1976; Kumar et al. 2017). In addition, heat stress induces impairment of chlorophyll biosynthetic reaction (Hemantaranjan et al. 2014).

Fig. 3.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on total chlorophyll (Chl) and total carotenoids (Cart.) contents in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b

Chickpea genotypes showed genotypic variations in chlorophyll a (chla) and chlorophyll b (chlb) contents. Significant reduction in chla and chlb were recorded under high temperature condition particularly at podding stage, when relatively higher temperature was faced by plants. In addition to this, maximum reduction was estimated in high temperature sensitive genotype (ICC 1882) under delayed sown heat stress condition. Heat tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) maintained higher level of chla and chlb under heat stress (Fig. 4). Reduction in chla and Chlb in sensitive genotypes under delayed sowing was due to damage in photosynthetic machinery (Xu et al. 1995; Kumar et al. 2017).

Fig. 4.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

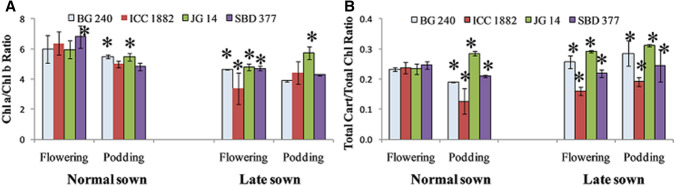

Ratio of chla: chlb and total carotenoids: total chlorophyll

Genotypic variations in chla: chlb and total chlorophyll: total carotenoids ratios were recorded. Reduction in chla: chlb and total chlorophyll: total carotenoids ratios were noted under heat stress condition and maximum reduction was obtained in heat sensitive genotype (ICC 1882). Heat tolerant genotypes showed higher level of chla: chlb and total chlorophyll: total carotenoids ratios (Fig. 5). Under heat stress, an increase in chla: chlb and decrease in total chlorophyll: total carotenoids ratios have also been recorded in heat tolerant genotypes of tomato (Camejo et al. 2005) and sugarcane (Wahid and Ghazanfar 2006).

Fig. 5.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b and total carotenoids/total chlorophyll ratio in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Photosynthetic pigments profile

Genotypic variations in photosynthetic pigment profile were noted. In general, under delayed sown heat stress condition, reductions in the density of the photosynthetic pigments were noted. Photosynthetic pigment profile obtained by using thin layer chromatography (TLC) had chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, pheophytin a and pheophytin b, ß-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin and neaxanthin. Besides this, intermediates of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b were also seen in trace quantities which were not marked on TLC plates. Further, relatively heat tolerant genotypes maintained darker bands even under delayed sown heat stress condition as compared to heat sensitive genotype (ICC 1882) (Fig. 6) probably by protecting photosynthetic machinery in general and photosystem II in particular.

Fig. 6.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on photosynthetic pigments profile in diverse set of chickpea genotypes

Carotenoids composition

Chickpea genotypes showed the genotypic variations in carotenoids (xanthophyll cycle pigments) composition. Maximum amount of the carotenoids is shared by ß-carotene and lutein. Heat tolerant genotypes showed increment in the level of carotenoids under heat stress. Under heat stress, excess accumulation of H2O2 increases the levels carotenoids, as they are continually involved in rebalancing the equilibrium (De Silva and Asaeda, 2017). Carotenoids deactivate H2O2, also quench triplet sensitizers and excited chlorophyll (Sharma et al. 2012). Carotenoids protect cellular structures in a variety of plant species under abiotic stress (Havaux 1998; Wahid and Ghazanfar 2006; Wahid 2007). In general, all the genotypes under timely sown condition had higher amount of violaxanthin while under delayed sown condition, reduction in content of violaxanthin and induction in the content of zeaxanthin were noted under delayed sown heat stress condition due to the conversion of violaxanthin into zeaxanthin and further the involvement of zeaxanthin in heat dissipation and protection of photosynthetic machinery. In general, high temperature tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) enhanced the higher level of zeaxanthin under late sown high temperature condition than the sensitive one (ICC 1882) (Fig. 7). This in turn indicated that zeaxanthin cycle operates under delayed sown heat stress condition and thus contributes in heat stress tolerance. The conversion of violaxanthin to zeaxanthin in the light-dependent xanthophyll cycle takes part in the thermal dissipation of energy (Jahns et al. 2009).

Fig. 7.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on carotenoids (μg/g wt.) composition in diverse set of chickpea genotypes

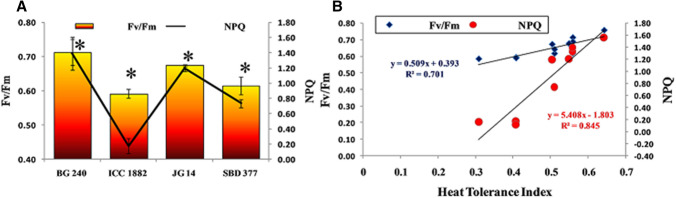

Maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) and non photochemical quenching

Significant genotypic variations were noted under delayed sown heat stress condition. Heat tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) showed the higher values of Fv/Fm under late sown heat stress condition as compared to sensitive one. In addition to this, high temperature sensitive genotype (ICC 1882) exhibited the lowest value of non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) and heat tolerant genotype maintained higher level of NPQ under delayed sown heat stress condition (Fig. 8a). Further, quantum yield (Fv/Fm) ratio and NPQ showed the significant association with heat tolerance index (Fig. 8b). Present findings in turn indicated that xanthophylls cycle pigments protected the photosynthetic machinery by inducing higher level of NPQ under late sown high temperature condition in tolerant genotypes than the sensitive one. Photosynthesis is the most heat-sensitive processes and it can be suppressed by heat stress due to the inhibition of photosystem II (PSII) activity (Havaux et al. 1991, Camejo et al. 2005). Chlorophyll fluorescence, the ratio of variable fluorescence to maximum fluorescence (Fv/Fm), has been shown to correlate with heat tolerance (Yamada et al. 1996; Efeoglu and Terzioglu 2009).

Fig. 8.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on quantum yield (Fv/Fm) and non photochemical quenching (a) and their association with Heat tolerance index (b) in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

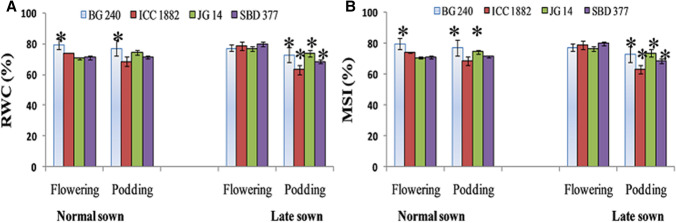

Relative water content and membrane stability index

Under normal and delayed sown conditions genotypic variations were noted in relative water content (RWC %) and membrane stability index (MSI %) at flowering and podding stage. Significant reduction in RWC (%) and MSI (%) were recorded under delayed sown heat stress condition particularly at podding stage as compared to normal sown one. Maximum reduction in RWC (%) and MSI (%) were recorded in ICC 1882 (high temperature sensitive) genotype under late sown condition (Fig. 9). Level of RWC (%) is reduced due to increase in transpiration under delayed sown heat stress condition (Tsukaguchi et al. 2003; Wahid and Close 2007). Enhancement in solute leakage indicates reduction in cell membrane thermostability (CMT) which has long been used as an indirect gauge of heat-stress tolerance in diverse plant species like soybean (Martineau et al. 1979), potato and tomato (Chen et al. 1982), wheat (Blum et al. 2001; Kumar et al 2013), maize (Ashraf and Hafeez 2004) and barley (Wahid and Shabbir 2005).

Fig. 9.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on relative water content (a) (b) and membrane stability index in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Lipid peroxidation

Chickpea genotypes showed the genotypic variations under both timely and delayed sown conditions. Lipid peroxidation activity was increased under delayed sown heat stress condition in all the genotypes. Heat tolerant sensitive genotype (ICC 1882) had the highest level of lipid peroxidation under both timely and delayed sown heat stress conditions. In contrast to this, relatively heat tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) exhibited the lower lipid peroxidation activity particularly under delayed sown heat stress conditions at podding stage (Fig. 10). Under heat stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production causes oxidative damage to crucial cellular constituents such as membrane lipids, proteins, nucleic acids, pigments, and enzymes. The ROS-induced oxidative damage comprises free radicals, containing hydroxyl radicals (OH˙), superoxide (O2−), alkoxyl radicals, and non-radicals like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and singlet oxygen (1O2). Under heat stress, increased lipid peroxidation and hydrogen peroxide levels in the leaves of heat-sensitive chickpea genotypes caused more leaf damage as compared to tolerant genotypes (Kaushal et al. 2011). Lipid peroxidation is good indicator of stress because it is associated with oxidative damage. Similarly, enhancement in lipid peroxidation was also recorded under heat stress in cotton (Mahan and Mauget 2005) and wheat (Khan et al. 2017).

Fig. 10.

Lipid peroxidation in chickpea genotypes under normal and late sown heat stress conditions. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Post harvest observations

Genotypic variations were recorded in post harvest observations under both timely and delayed sown heat stress conditions. At harvest, plant height was reduced under delayed sown condition and least height was measured in ICC 1882. However, under late sown condition, root length of all the genotypes were increased and longest root length was recorded in JG 14. Main and secondary branches were also reduced under delayed sown heat stress condition and maximum reduction particularly in secondary branches was recorded in ICC 1882 (Table 1). Leaf dry weight, root dry weight, pod weight and total dry matter were reduced under late sown high temperature condition. Heat tolerant genotypes had higher allocation of dry matter to pod as compared to heat sensitive one (Fig. 11) because of better photosynthetic activity of source improved the economic sink demand.

Table 1.

Post harvest parameters recorded in chickpea varieties under normal sown and late sown heat stress conditions

| Sowing timings | Genotypes | Plant height (cm) | Root length (cm) | No. of main branches/plant | No. of secondary branches/plant | Pods/plant | Pod weight (g)/Plant | Grain yield (q/ha) | Seed no./plant | 1000 seed weight (g) | TDM (q/ha) | Harvest index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal sown | BG 240 | 44.83 | 5.90 | 3.33 | 7.00 | 26.00 | 5.46 | 24.32 | 23.00 | 197.60 | 60.05 | 40.48 |

| ICC 1882 | 40.08 | 6.95 | 3.17 | 10.50 | 29.17 | 4.84 | 21.23 | 28.83 | 142.02 | 60.69 | 34.85 | |

| JG 14 | 48.33 | 7.25 | 4.17 | 5.50 | 30.50 | 6.85 | 28.11 | 27.67 | 207.18 | 77.65 | 36.21 | |

| SBD 377 | 44.67 | 8.50 | 3.50 | 6.67 | 13.33 | 3.83 | 17.81 | 11.00 | 306.26 | 53.65 | 33.29 | |

| Mean | 44.48 | 7.15 | 3.54 | 7.42 | 24.75 | 5.25 | 22.87 | 22.63 | 213.26 | 63.01 | 36.21 | |

| Late sown high temperature | BG 240 | 43.00 | 8.00 | 2.83 | 4.50 | 11.33 | 2.98 | 13.33 | 12.67 | 206.76 | 34.98 | 38.69 |

| ICC 1882 | 36.17 | 11.83 | 2.50 | 4.17 | 17.67 | 2.21 | 8.27 | 16.33 | 97.22 | 24.96 | 33.38 | |

| JG 14 | 40.67 | 11.88 | 2.33 | 3.50 | 15.50 | 3.48 | 15.41 | 16.33 | 179.15 | 38.61 | 39.72 | |

| SBD 377 | 43.83 | 8.63 | 2.50 | 3.50 | 7.83 | 2.66 | 8.96 | 7.67 | 223.17 | 35.89 | 26.50 | |

| Mean | 40.92 | 9.89 | 2.54 | 3.92 | 13.08 | 2.83 | 11.49 | 13.25 | 176.57 | 33.61 | 34.57 | |

| CD at 5% | ||||||||||||

| Sowing (A) | 2.316 | 2.214 | 0.644 | 0.666 | 2.523 | 0.719 | 1.65 | 3.597 | 20.089 | 3.71 | N/A | |

| Genotype (B) | 3.275 | N/A | N/A | 0.941 | 3.568 | 1.017 | 2.33 | 5.088 | 28.411 | 5.25 | 3.852 | |

| A × B | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.331 | 5.046 | N/A | 3.29 | 7.195 | 40.179 | 7.42 | N/A | |

Fig. 11.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on dry matter allocation in diverse set of chickpea genotypes

Chickpea genotypes also showed the genotypic variations in grain yield and its attributes under both normal and late sown high temperature conditions. In general all the genotypes, exhibited reduction in grain yield and its attributes under late sown high temperature condition. Maximum reduction in grain yield was recorded in high temperature sensitive genotypes (ICC 1882 and SBD 377). However, relatively heat tolerant genotype maintained higher grain yield under late sown heat stress condition. JG 14 had the highest grain yield under heat stress. Heat stress reduces crop yield by influencing both source and sink for assimilates (Mendham and Salisbury 1995; Devasirvatham et al. 2012a, b). Reduction in grain length and width was found to be associated with a lessening in the average endosperm cell area observed under high night temperature (Morita et al. 2005). Plants grown under delayed sown heat stress condition, exhibit reduction in stomatal conductance for conserving water. Stomatal conductance is an important component of photosynthesis therefore, CO2 fixation and photosynthetic rate are reduced, resulting in less assimilates production for growth and yield of plants (Wahid et al. 2007).

Similarly, all genotypes showed the reduction in pods per plant, seeds per plant and test weight under delayed sown heat stress condition and maximum reduction was analyzed in test weight under heat stress condition. Heat tolerant genotypes (JG 14 and BG 240) had lower reduction in pods, seed number and test weight as compared to heat sensitive ones (ICC 1882 and SBD 377). Harvest index also showed the genotypic variability under both normal and delayed sown heat stress conditions and reduction in harvest index under delayed sown heat stress condition. Under delayed sown heat stress condition, maximum reduction in harvest index was recorded in SBD 377. However, tolerant genotype maintained the harvest index under delayed sown heat stress condition (Table 1). Diminution in harvest index by 0–65% was also recorded in peanut genotypes under heat stress (Craufurd et al. 2002).

Heat susceptibility and heat tolerance

Under delayed sown heat stress condition, heat tolerant genotypes had lower values of heat susceptibility index (HSI) and heat sensitive genotype (ICC 1882) had the highest value of HSI. In contrast, heat tolerance index (HTI) exhibited reverse trend to HSI i.e. heat tolerant genotypes (BG 240 and JG 14) had higher value of HTI while heat sensitive genotypes had the higher value of HSI as compared to tolerant ones (Fig. 12). Heat susceptibility was found responsible for yield loss in Phaseolus vulgaris (Rainey and Griffiths 2005), chickpea (Wang et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2017) and peanut (Vara Prasad et al. 1999).

Fig. 12.

Effect of late sown condition high temperature stress on heat susceptibility index and heat tolerance index in diverse set of chickpea genotypes. Small vertical bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Star (*) on the bars shows significant difference at (p < 0.05)

Conclusion

From the present study it can be concluded that heat tolerant genotypes had higher values of zeaxanthin pigment, Fv/Fm ratio, non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), photosynthetic rate (PN), chlorophylls, total carotenoids and lower level of lipid peroxidation as compared to sensitive one under heat stress condition. Higher level of zeaxanthin and lower value violaxanthin in heat tolerant genotypes as well as association of NPQ with heat tolerance in turn indicated that zeaxanthin cycle is involved in heat tolerance in chickpea.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the IARI, New Delhi for providing necessary facility and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi for financial support (CSIR Project No.: 38(1335)/12/EMR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arnon DI. Copper enzyme polyphenoloxides in isolated chloroplast in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M, Hafeez M. Thermotolerance of pearl millet and maize at early growth stages: growth and nutrient relations. Biol Plant. 2004;48:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Blum A, Ebercon A. Cell membrane stability as a measure of drought and heat tolerance in wheat. Crop Sci. 1981;21:43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blum A, Klueva N, Nguyen HT. Wheat cellular thermotolerance is related to yield under heat stress. Euphytica. 2001;117:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bouslama M, Schapaugh WT. Stress tolerance in soybean. Part 1: evaluation of three screening techniques for heat and drought tolerance. Crop Sci. 1984;24:933–937. [Google Scholar]

- Camejo D, Rodríguez P, Morales MA, Dell’Amico JM, Torrecillas A, Alarcón JJ. High temperature effects on photosynthetic activity of two tomato cultivars with different heat susceptibility. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen THH, Shen ZY, Lee PH. Adaptability of crop plants to high temperature stress. Crop Sci. 1982;22:719–725. [Google Scholar]

- Craufurd PQ, Prasad PV, Summerfield RJ. Dry matter production and rate of change of harvest index at high temperature in peanut. Crop Sci. 2002;42:46–151. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2002.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva HCC, Asaeda T. Effects of heat stress on growth, photosynthetic pigments, oxidative damage and competitive capacity of three submerged macrophytes. J Plant Interact. 2017;12(1):228–236. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2017.1322153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW., III The role of xanthophyll cycle carotenoids in the protection of photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1(1):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Devasirvatham V, Gaur PM, Mallikarjuna N, Tokachichu RN, Trethowan RM, Tan DKY. Effect of high temperature on the reproductive development of chickpea genotypes under controlled environments. Funct Plant Biol. 2012;39:1009–1018. doi: 10.1071/FP12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasirvatham V, Tan DKY, Gaur PM, Raju TN, Trethowan RM. High temperature tolerance in chickpea and its implications for plant improvement. Crop Pasture Sci. 2012;63:419–428. doi: 10.1071/CP11218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit GP, Srivastava AK, Singh NP. Marching towards self-sufficiency in chickpea. Curr Sci. 2019;216(2):239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Efeoglu B, Terzioglu S. Photosynthetic responses of two wheat varieties to high temperature. Eur Asia J Biol Sci. 2009;3:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban R, Moran JF, Becerril JM, García-Plazaola JI. Versatility of carotenoids: an integrated view on diversity, evolution, functional roles and environmental interactions. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;119:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Greppin H, Strasser RJ. Functioning of photosystems I and II in pea leaves exposed to heat stress in the presence or absence of light: Analysis using in vivo fluorescence absorbance, oxygen and photoacoustic measurement. Planta. 1991;186(1):88–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00201502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M. Carotenoids as membrane stabilizers in chloroplasts. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts, kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemantaranjan A, Nishant Bhanu A, Singh MN, Yadav DK, Patel PK, Singh R, Katiyar D. Heat stress responses and thermotolerance. Adv Plants Agric Res. 2014;1(3):00012. doi: 10.15406/apar.2014.01.00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox JD, Israelstam GF. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Can J Bot. 1979;57:1332–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Jahns P, Latowski D, Strzalka K. Mechanism and regulation of the violaxanthin cycle: the role of antenna proteins and membrane lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra N, Chakraborty D, Sharma A, Rai HK, Jolly M, Chander S, Kumar PR, Bhadraray S, Barman D, Mittal RB, Lal M, Sehgal M. Effect of temperature on yield of some winter crops in northwest India. Curr Sci. 2008;94:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Gupta K, Bhandhari K, Kumar S, Thakur P, Nayyar H. Proline induces heat tolerance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) plants by protecting vital enzymes of carbon and antioxidative metabolism. Plant Physiol Mol Biol. 2011;17:203–213. doi: 10.1007/s12298-011-0078-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Awasthi R, Gupta K, Gaur PM, Siddique KHM, Nayyar H. Heat-stress-induced reproductive failures in chickpea (Cicer arietinum) are associated with impaired sucrose metabolism in leaves and anthers. Funct Plant Biol. 2013;40:1334–1349. doi: 10.1071/FP13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NA, Khan S, Naz N, Shah M, Irfanullah A, Sher H, Khan A. Effect of heat stress on growth, physiological and biochemical activities of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Int J Biol Sci. 2017;11(4):173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Sharma RK, Kumar P, Singh GP, Sharma JB, Gajghate R. Evaluation of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes for terminal heat tolerance through physiological traits and grain yield. Indian J Genet Plant Breed. 2013;73(4):446–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Shah D, Singh MP. Evaluation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes for heat tolerance: a physiological assessment. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2017;22(2):164–177. doi: 10.1007/s40502-017-0301-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaoui M, Jemo M, Datla R, Bekkaoui F. Heat and drought stresses in crops and approaches for their mitigation. Front Chem. 2018;6:26. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK, Welburn AR. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11:591–592. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Shao Z, Zhang M, Wang Q. Regulation of carotenoid metabolism in tomato. Mol Plant. 2015;8:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan JR, Mauget SV. Antioxidant metabolism in cotton seedlings exposed to temperature stress in the field. Crop Sci. 2005;45:2337–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau JR, Specht JE, Williams JH, Sullivan CY. Temperature tolerance in soybean. I. Evaluation of technique for assessing cellular membrane thermostability. Crop Sci. 1979;19:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mendham NJ, Salisbury PA. Physiology, crop development, growth and yield. In: Kimber DS, McGregor DI, editors. Brassica oilseeds: production and utilization. London: CABI; 1995. pp. 11–64. [Google Scholar]

- Morita S, Yonermaru J, Takahashi J. Grain growth and endosperm cell size under high night temperature in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Ann Bot. 2005;95:695–701. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock T, Krol M, Huner NPA. The determination and quantification of photosynthetic pigments by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography, thin-layer chromatography, and spectrophotometry. In: Carpentier R, editor. Methods in molecular biology. Photosynthesis research protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 2004. pp. 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porch TG. Application of stress indices for heat tolerance screening of common bean. J Agron Crop Sci. 2006;192:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey KM, Griffiths PD. Inheritance of heat tolerance during reproductive development in snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2005;130(5):700–706. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot. 2012;2012:1–26. doi: 10.1155/2012/217037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, Takeda H, Senboku T. Heat tolerance in food legumes as evaluated by cell membrane thermostability and chlorophyll fluorescence techniques. Euphytica. 1996;88:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Trojak M, Skowron E. Improvement of plant heat tolerance by modification of xanthophyll cycle activity. World Sci News. 2017;70(2):51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaguchi T, Kawamitsu Y, Takeda H, Suzuki K, Egawa Y. Water status of flower buds and leaves as affected by high temperature in heat tolerant and heat-sensitive cultivars of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Plant Prod Sci. 2003;6:4–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hasselt PR, Strikwerda JT. Pigment degradation in discs of the thermophilic Cucumis sativus as affected by light, temperature, sugar application and inhibitors. Plant Physiol. 1976;37(4):253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Vara Prasad PV, Craufurd PQ, Summerfield RJ, Wheeler TR. Effects of short episodes of heat stress on flower production and fruit-set of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) J Exp Bot. 1999;51(345):777–784. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.345.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A. Physiological implications of metabolites biosynthesis in net assimilation and heat stress tolerance of sugarcane sprouts. J Plant Res. 2007;120:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s10265-006-0040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A, Close TJ. Expression of dehydrins under heat stress and their relationship with water relations of sugarcane leaves. Biol Plant. 2007;51:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A, Ghazanfar A. Possible involvement of some secondary metabolites in salt tolerance of sugarcane. J Plant Physiol. 2006;163:723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A, Shabbir A. Induction of heat stress tolerance in barley seedlings by pre-sowing seed treatment with glycinebetaine. Plant Growth Reg. 2005;46:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A, Gelani S, Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;61:199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Gan YT, Clarke F, McDonald CL. Response of chickpea yield to high temperature stress during reproductive development. Crop Sci. 2006;46:2171–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherly PE. Studies in the water relations of cotton. 1. The field measurement of water deficits in leaves. New Phytol. 1950;49:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Williams PC, Singh U. Nutritional quality and the evaluation of quality in breeding program. Wallingford: Chickpea CAB International; 1987. pp. 329–356. [Google Scholar]

- Wise RR, Olson AJ, Schrader SM, Sharkey TD. Electron transport is the functional limitation of photosynthesis in field-grown Pima cotton plants at high temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2004;27:717–724. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Wang X, Liao MA. Xanthophyll cycle and its relative enzymes. J Life Sci. 2012;6(9):980. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Paulsen AQ, Guikema JA, Paulsen GM. Functional and ultrastructural injury to photosynthesis in wheat by high temperature during maturation. Environ Exp Bot. 1995;35:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Hidaka T, Fukamachi H. Heat tolerance in leaves of tropical fruit crops as measured by chlorophyll fluorescence. Sci Hortic. 1996;67:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Young LW, Wilen RW, Bonham-Smith PC. High temperature stress of Brassica napus during flowering reduces micro-and megagametophyte fertility, induces fruit abortion, and disrupts seed production. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:485–495. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]