Abstract

In this article, we adopt a radical approach for next generation ultra-low-power sensor design by embracing the evolutionary success of animals with extraordinary sensory information processing capabilities that allow them to survive in extreme and resource constrained environments. Stochastic resonance (SR) is one of those astounding phenomena, where noise, which is considered detrimental for electronic circuits and communication systems, plays a constructive role in the detection of weak signals. Here, we show SR in a photodetector based on monolayer MoS2 for detecting ultra-low-intensity subthreshold optical signals from a distant light emitting diode (LED). We demonstrate that weak periodic LED signals, which are otherwise undetectable, can be detected by a MoS2 photodetector in the presence of a finite and optimum amount of white Gaussian noise at a frugal energy expenditure of few tens of nano-Joules. The concept of SR is generic in nature and can be extended beyond photodetector to any other sensors.

Subject terms: Two-dimensional materials, Optical sensors

Here, the authors take advantage of stochastic resonance in a photodetector based on monolayer MoS2 for measuring otherwise undetectable, ultra-low-intensity, subthreshold optical signals from a distant light emitting diode in the presence of a finite and optimum amount of white Gaussian noise.

Introduction

Stochastic resonance (SR) is a remarkable phenomenon that shows the constructive role of noise in information processing contrary to the conventional wisdom that noise is a nuisance. In SR, a sensory system embedded in a noisy environment can detect weak time-variant signals when the noise intensity reaches some finite and appropriate level. Over the last three decades, SR has been discovered and demonstrated in a wide variety of geological, biological, and physical systems on almost every possible scale, highlighting its importance in both natural and artificial designs1–12. The concept of SR was first proposed in the context of a periodic recurrence of the Earth’s ice ages3 and was subsequently taken up and applied in sensory neurobiology for explaining animal behaviors leading to evolutionary success. For example, the electroreceptors located in the rostrum of paddlefish use SR to detect their feed zooplankton Daphnia, which predominantly dwell near river beds, where poor light and turbid water limit vision5. In behavioral experiments, it was shown that with optimal amount of noise a paddlefish is able to capture more distant plankton than without noise, whereas excessive noise led to almost no feeding. A similar behavioral SR was observed in the escape response of crickets from a predator wasp6. At the cellular level, SR is observed in the mechanoreceptor neurons located in the tail fans of crayfish when avoiding an approaching predator4 and at the most fundamental molecular level, SR plays a critical role in regulating the signal transduction by ion channels13. SR has already found application in medical care to restore the sensitivity of dysfunctional organs responsible for hearing14, tactile15 or visual sensations16 or for the balance control17 by means of applying the right amount of noise. The first demonstration of SR in electronic devices was based on a noise-driven Schmitt trigger circuit10. SR has now been observed in a wide variety of physical systems including bi-stable ring lasers9, optical heterodyning18, electronic paramagnetic resonance19, superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUID)7, and tunnel diodes8, among others. While there are some reports of experimental demonstration of SR in field-effect transistors (FETs) based on carbon nanotubes20–22, GaAs nanowires23–26, and organic semiconductors27, the strength of SR is yet to be exploited in solid-state sensors.

While some areas of science, especially sensory neurobiology, have invested significantly in research related to SR, sadly SR has remained largely unrecognized by the device community. This is not entirely surprising since the conventional approaches for improving the detection limit of various solid-state sensors continue to be extremely successful, inhibiting any radical ideas like SR from flourishing. There is no dispute that lock-in amplifiers, oscillators, low noise amplifiers, etc., will persist to advance and remain relevant and essential for electronic system design. However, these traditional approaches remain power hungry, area inefficient, and resource extensive. Fortunately, new technologies invoke new challenges, which foster new scientific discoveries and often rekindle older concepts that have been either abandoned or overlooked. Such is the case for SR with the emergence of the era of Internet of Things (IoT), one of the fastest-growing technologies which will rely on ~200 billion smart sensors by the end of the year 2020. These devices will bridge the physical world with the world of computing to revolutionize all aspects of human life, including healthcare, entertainment, home automation, wearables, telemetry, security, infrastructure, agriculture, and so on and so forth. However, the biggest challenges towards the realization of this IoT vision is the energy, and resource efficiency of these tens of billions of sensors. Most of these devices will be deployed at remote, inaccessible, and resource-constrained locations, where unlimited electrical energy is unavailable. While SR based sensors are unlikely to replace all conventional sensors, the energy benefits of SR can no longer be ignored in the context of rapidly evolving IoT technology.

In this article, we exploit SR for detecting ultra-low-intensity and otherwise undetectable optical signals from a distant light-emitting diode (LED) using a monolayer MoS2 based photodetector with unprecedented energy efficiency. We demonstrate that the detection of subthreshold LED illumination is possible by adding a finite and optimum amount of white Gaussian noise. The noise can be either in the source of the weak periodic signal or externally added through an on-chip noise generator. We also show that the concept of SR can be exploited to extend the detection limit of state-of-the-art commercial photodetectors such as Si photodiodes. Finally, we show that subthreshold signal detection can be achieved at the frugal energy expenditure of few nano-Joules by the MoS2 photodetector and a few micro-Joules by the Si photodiode, emphasizing the energy benefits of SR. While our exhibition of SR primarily involves photodetectors, the concept of SR is generic in nature and can be extended to any sensors. SR-based sensors can mark a paradigm shift from conventional approaches by harnessing the constructive role of noise in the detection of subthreshold signals.

Results

Monolayer MoS2 synthesis, characterization, and device fabrication

MoS2 is a layered two-dimensional (2D) semiconductor that belongs to the family of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) with the general formula of MX2, where M represents the transition metal (Mo, W, etc.) and X represents chalcogen (S, Se, Te, etc.)28–30. These materials exhibit strong intra-layer covalent bonding and weak van der Waals (vdW) interlayer coupling that allows separation of monolayers from their respective bulk crystal with unprecedented electronic and optoelectronic properties, making them attractive for the next generations of advanced sensors. For example, monolayer TMDCs are direct bandgap semiconductors, fostering enhanced light-matter interaction and thereby enabling photonic devices31. Furthermore, the atomically thin body nature of TMDCs allows for superior electrostatic control of charge carriers, which is critical for achieving low power operation32. While most of the preliminary device studies are performed on micromechanically exfoliated single-crystal flakes, transitioning to technology requires manufacturable solutions. Therefore, the present study uses large-area growth of monolayer MoS2 film using a scalable bottom-up synthesis technique, namely the metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), on a sapphire substrate at 1000 °C. Higher growth temperatures, hydride chalcogen precursors, and epitaxial growth offer better crystallinity33, reduced carbon contamination34, and hence higher device performance in terms of ON current and carrier mobility, as we shall demonstrate and discuss later.

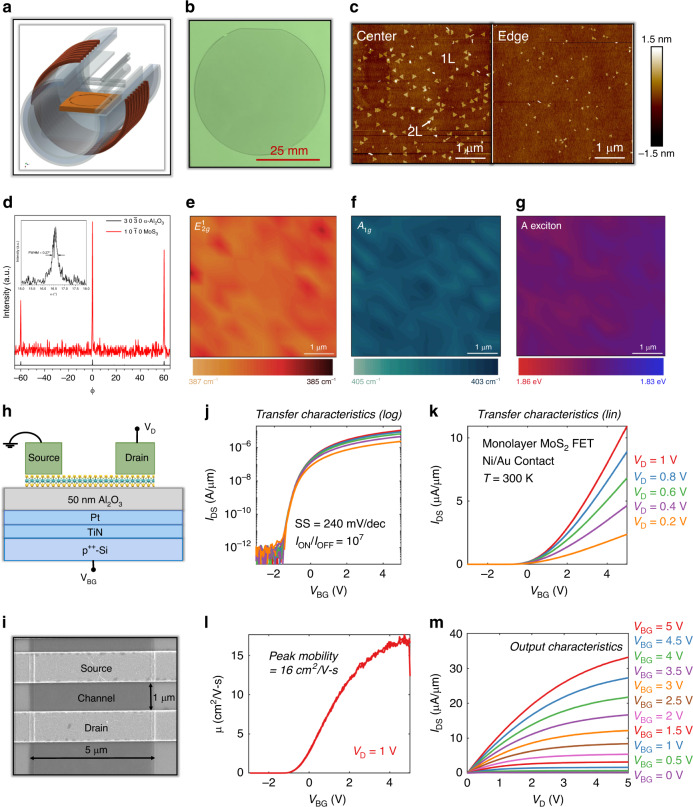

A schematic of the cold-wall horizontal reactor setup is shown in Fig. 1a. Molybdenum hexacarbonyl, Mo(CO)6, and H2S were introduced into the growth zone in a H2 carrier gas at 1000 °C for 18 min to obtain a coalesced monolayer MoS2 film on a 2-inch sapphire substrate as shown in Fig. 1b. Surface coverage, film morphology, and thickness were measured using an atomic force microscope (AFM) at the center and edge of the wafer as shown in Fig. 1c. As is evident, the bilayer density was found to be higher at the center than the edges. The crystalline quality was assessed using in-plane X-ray diffraction35. The φ-scan in Fig. 1d establishes the epitaxial relation between MoS2 and sapphire as (100) MoS2 ‖ (100) α-Al2O3. In addition, the inset shows a narrow full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of 0.27°, which emphasizes the high crystalline quality of these monolayer films. Following the synthesis, the MoS2 film was transferred from the growth substrate to the device fabrication substrate using the PMMA-assisted wet transfer process36. We have used atomic layer deposition (ALD) grown 50 nm Al2O3 (εox ~ 9) on Pt/TiN/p++-Si for the device fabrication. The transferred film quality was assessed using Raman spectroscopy and photoluminescence (PL) maps, as shown in Fig. 1e–g. The (Fig. 1e) and A1g (Fig. 1f) peak positions vary <5% over the entire map and the peak separation of 18 cm−1 corresponds to monolayer MoS237. The uniform and intense PL peak observed at 1.84 eV (Fig. 1g) is attributed to the indirect to direct bandgap transition at the K point in the Brillouin zone in monolayers and is severely suppressed in multilayers of MoS238,39.

Fig. 1. Monolayer MoS2 synthesis, characterization, and device fabrication.

a Schematic of cold-wall horizontal reactor setup. b Coalesced monolayer MoS2 film grown on a 2-inch sapphire substrate using MOCVD at 1000 °C with Mo(CO)6 and H2S as precursors. c AFM images at the center and edge of the wafer showing uniform surface coverage, film morphology, and thickness. d In-plane X-ray diffraction showing the epitaxial relation between MoS2 and sapphire as (100) MoS2 ‖ (100) α-Al2O3. The inset shows a narrow full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of 0.27°, which emphasizes the high crystalline quality of these monolayer films. Raman map of (e) and (f) A1g peaks show <5% variation and the peak separation of 18 cm−1 confirms monolayer MoS2. g Photoluminescence (PL) map shows an intense peak at 1.84 eV, which is attributed to the indirect to direct bandgap transition in monolayers and is severely suppressed in multilayers of MoS2. h Schematic and i SEM image of monolayer MoS2 FET. j Logarithmic scale and k linear scale transfer characteristics of monolayer MoS2 FET measured at different drain biases (VD). l Mobility plot and m output characteristics measured at different back gate biases (VBG).

After ensuring the high quality and uniformity of the film, we fabricated monolayer MoS2 FET based photodetectors as shown using the schematic and scanning electron microscope (SEM) image in Fig. 1h and i, respectively. The devices have 1 μm channel length, 5 μm channel width, 40 nm Ni/ 30 nm Au as the source/drain contacts, and 50 nm Al2O3 as the back-gate dielectric. The use of thin and high-k dielectric material such as Al2O3 compared to conventional 300 nm of SiO2 allows supply voltage scaling due to better electrostatic gate control and aids the ultra-low-power operation of the photodetector. Further details on the synthesis, film transfer, characterization, device fabrication, and electrical measurements of monolayer MoS2 photodetector are provided in the “Method” section. Figure 1j and k show the transfer characteristics, i.e. source to drain current (IDS) as a function of the back gate voltage (VBG) for the monolayer MoS2 FET measured at different drain biases (VD) in the logarithmic and linear scales, respectively. The MoS2 FET exhibits unipolar n-type transport owing to the phenomenon of metal Fermi level pinning close to the conduction band facilitating electron injection, which is consistent with all other previous reports40,41. The device shows excellent ON/OFF current ratio in excess of 107, subthreshold slope (SS) of less than 294 mV/decade, none to minimal drain induced barrier lowering (DIBL)42, absence of any gate hysteresis even under ambient measurements, low gate leakage, and low contact resistance, thus indicating high quality of the gate dielectric, semiconducting MoS2 channel, and dielectric and contact interfaces (see Supplementary Note 1). Combined, the device exhibits low voltage operation under 5 V for both the back-gate bias and drain bias. The threshold voltage (VTH) was found to be ~0.2 V and the field-effect mobility (μFE) value was found to be ~16 cm2 V−1 s−1 extracted from the peak transconductance, as shown in Fig. 1l. The μFE value is comparable to exfoliated single-crystal monolayer MoS2. This is also reflected in the output characteristics (i.e., IDS versus VD for different VBG) of the MoS2 FET, with the ON current reaching as high as ~35 μA/μm at VD = 5 V for an inversion charge carrier density of ~5 × 1012 cm−2, as shown in Fig. 1m. We also measured the transfer characteristics of 10 devices across the entire substrate and found consistent device performance, confirming uniform wafer-scale growth of high-quality monolayer MoS2.

Demonstration of SR in monolayer MoS2 FET

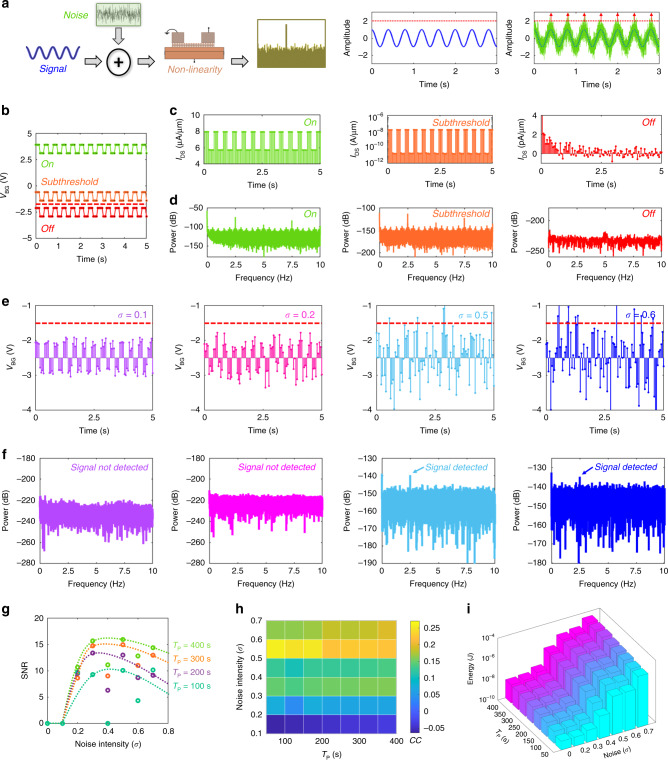

Figure 2a explains the basic concept of SR that requires three essential components: (i) a nonlinear thresholding device; (ii) a weak coherent input (such as a periodic signal) which is below the detection threshold of the device; and (iii) a source of noise either inherent to the device or added externally to the coherent input. Before moving on to SR in MoS2 photodetector, first, we illustrate the concept of SR using a monolayer MoS2 FET. Figure 2b shows a 2.5 Hz periodic input signal of amplitude 0.4 V applied to the back gate at different operating regimes: ON-state (VBG = 3.5 V), subthreshold (VBG = −1 V), and OFF-state (VBG = −2.5 V). Figure 2c and d, respectively, show IDS and the corresponding power spectral density (PSD) obtained using fast Fourier transforms (FFTs). The current sampling was done at 20 Hz for ~100 s. As expected, IDS follows the VBG waveform in the ON state owing to linear device operation and the corresponding PSD shows a sharp peak at 2.5 Hz, which is the input signal frequency. In the subthreshold regime, the output current waveform is distorted since the device characteristics exhibit nonlinearity owing to the exponential dependence of IDS on VBG. The corresponding PSD of IDS, however, detects the input signal at 2.5 Hz. Finally, in the OFF state (VBG < −1.5 V), IDS is obscured by the noise floor and correspondingly peaks are absent in the PSD.

Fig. 2. Demonstration of stochastic resonance (SR) in monolayer MoS2 field-effect transistor (FET).

a Schematic showing the basic concept of SR with three essential components: a nonlinear thresholding device, a weak coherent input such as a periodic signal, and a source of noise. When the noise intensity reaches some finite and appropriate level, the system can detect the weak time-variant signal, which otherwise lies below the detection threshold of the sensor. b A 2.5 Hz square wave of amplitude 0.4 V is applied to the back-gate of the monolayer MoS2 FET at different operating regimes: ON-state (VBG = 3.5 V), subthreshold (VBG = −1 V), and OFF-state (VBG = −2.5 V). c Output current (IDS) and d corresponding PSD plots obtained using the FFT. Current sampling was done at 20 Hz for ~100 s. In the ON-state and subthreshold regime the signal is detected, whereas, in the OFF-state, IDS is obscured by the noise floor and corresponding peaks are absent in the PSD. e In order to detect the signal in the OFF-state, Gaussian noise of different standard deviations (σ) are superimposed on the square wave centered at VBG = −2.5 V. f PSD of measured IDS. The current sampling was done at 20 Hz for ~400 s. The signal is detected for an optimum amount of Gaussian noise, confirming SR in MoS2 FET. g SNR as a function of σ for various total sampling time (TP). h Color map of the correlation coefficient (CC) between IDS and VBG. i Energy consumption as a function of σ for various TP. Clearly, optimum signal detection can be achieved with energy as frugal as 10–100 nJ corresponding to σ = 0.5 V.

In order to detect the periodic signal in the OFF state, Gaussian noise with different values of standard deviation (σ) was added to the periodic input signal (VBG), as shown in Fig. 2e. Figure 2f shows the corresponding PSD of IDS. Current sampling was done at 20 Hz for ~400 s. Remarkably, in the presence of an optimum amount of Gaussian noise, the PSD data exhibits a peak at the input signal frequency of 2.5 Hz. Figure 2g shows the SNR as a function of σ for various total sampling time (TP). The histograms of VBG distribution for the bi-level square wave input signal shown in the Supplementary Note 2 help in explaining the nonmonotonic trend in the SNR. For very low variance Gaussian noise (σ < 0.2 V), none of the two signal levels crosses the detection threshold (VBG = −1.5 V), whereas, for very high variance Gaussian noise (σ > 0.6 V), both signal levels cross the detection threshold and obscures the periodicity of the signal. However, for appropriate noise variance, mostly one of the two signal levels cross the detection threshold allowing the signal frequency to be detected and as such the PSD exhibits a peak at 2.5 Hz. Note that the SNR can be increased by increasing the TP since it allows the subthreshold signal to cross the detection threshold a greater number of times. A similar observation is made in Fig. 2h showing the colormap of the correlation coefficient (CC) between IDS and VBG. Finally, Fig. 2i shows the energy consumption by the MoS2 FET for detecting the weak period signal as a function of σ for different TP calculated based on E = IDSVDTp. Clearly, optimum signal detection can be achieved with energy as frugal as 10–100 nJ corresponding to σ = 0.5 V.

To elucidate some key aspects of SR, we have used the Virtual Source (VS) model43–45, described in Supplementary Note 3, for fitting the monolayer MoS2 FET characteristics. In the VS model, both the subthreshold and the above threshold FET characteristics are captured through a single semi-empirical and phenomenological relationship that describes the transition in channel charge from weak to strong inversion. The model parameters were obtained from experimentally measured device characteristics. First, we show that while noise with optimum standard deviation yields maximum enhancement in the SNR, noise with any finite non-zero standard deviation can achieve the same SNR when averaged over longer period. This is because the tail of any Gaussian distribution with finite standard deviation extends to infinity. Therefore, there is always a finite probability that the on-signal will cross the threshold even when the standard deviation of noise is small. By sampling the signal over a longer time, one ensures enough threshold crossing events at the signal frequency, which then adds up in the PSD to enhance the SNR. Supplementary Note 4 shows the simulated PSD of IDS in response to a 2.5 Hz periodic input signal of amplitude 0.2 V with Gaussian noise of different standard deviations (σ) applied to the back gate in the OFF-state (VBG = −2.5 V) for an averaging period that ranges from 103 s to 107 s and the corresponding SNR values. As expected, no peaks are observed for σ = 0 V, i.e., without noise even if the sampling is done for an infinitely long period of time. For small σ (σ = 0.2 V), the peak appears after sampling for 107 s, whereas, for optimum σ (σ = 0.5 V), the peak appears after 103 s. These simulation results indicate that the SR induced enhancement of SNR can be achieved using any finite value of σ at the expense of increased latency. Finally, Supplementary Note 5 shows that the signal frequency does not impose any limitation on the exploitation of SR for the detection of weak periodic signals. In fact, an earlier work has explored THz wave detection by GaAs nanowire-based FETs using SR46.

Detection limit for monolayer MoS2 photodetector

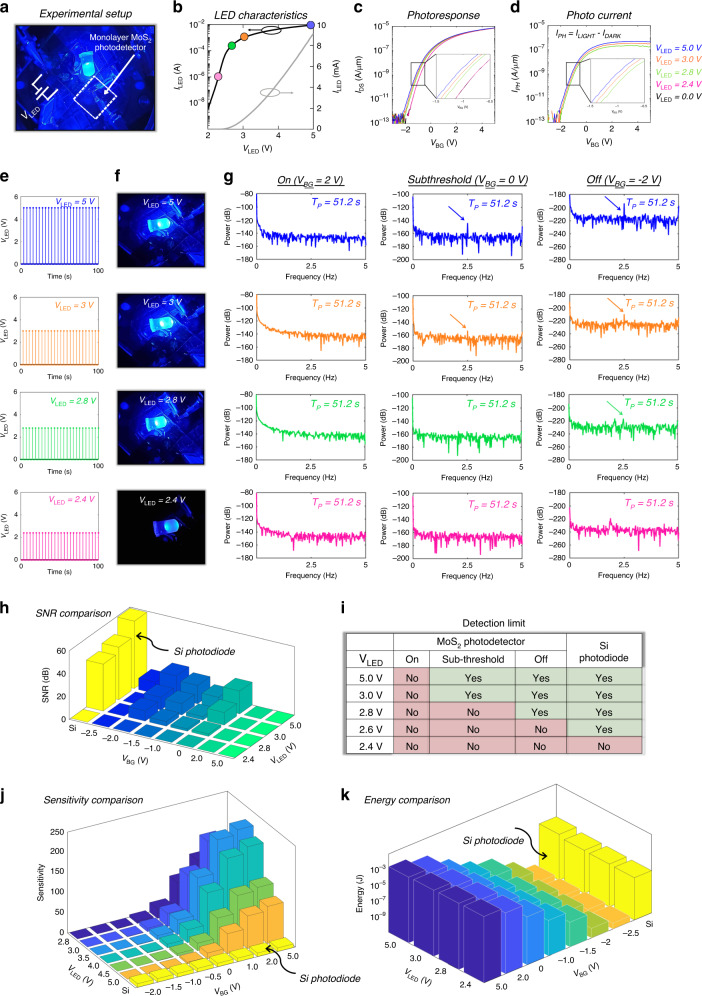

Figure 3a shows the experimental set-up used for the demonstration of SR, consisting of a monolayer MoS2 photodetector and a blue LED spaced ~1 cm away from the photodetector. Note that monolayer MoS2 is a direct bandgap (EG = 1.84 eV) semiconductor with high quantum yield30, which makes it attractive for photonic device applications47–49. While most of the studies reporting the optical response of monolayer MoS2 are based on LASER excitation, we have used an LED source to mimic ultra-low-intensity realistic light sources. Figure 3b shows the current (ILED) versus voltage (VLED) characteristics of the LED. Figure 3c and d, respectively, show the output current (IDS) and extracted photocurrent (IPH) in the MoS2 photodetector under different LED illuminations. In order to determine the sensitivity and detection threshold for the MoS2 photodetector, we applied 2.5 Hz periodic LED signals of different amplitudes, as shown in Fig. 3e. The snapshots of the glowing LED at the corresponding VLED biases are shown in Fig. 3f. The LED intensity drops linearly for 5 V > VLED > 2.8 V and exponentially for VLED < 2.8 V in accordance with the output characteristics of the LED, as indicated using the colored circles in Fig. 3b. Figure 3g shows the corresponding PSD plots obtained from the FFT of the output current (IDS) measured in the monolayer MoS2 photodetector for a total duration of TP = 51.2 s in the ON-state (VBG = 2 V), subthreshold (VBG = 0 V), and OFF-state (VBG = −2 V). In all cases, current sampling was done at 10 Hz. Peaks observed in the PSD at 2.5 Hz are indications of successful detection of the periodic LED signal by the MoS2 photodetector. Figure 3h shows the extracted SNR in different detection regimes for various LED illuminations and Fig. 3i summarizes the detection limit for the blue light by the MoS2 photodetector. For comparison, we have also included the results obtained from the same experiments performed on a commercial Si photodiode in Supplementary Note 6.

Fig. 3. Detection limit of monolayer MoS2 photodetector.

a Experimental setup showing the photodetector chip based on monolayer MoS2 FET placed at a distance of ~1 cm from a blue LED. b Current (ILED) versus voltage (VLED) characteristics of the LED. c Transfer characteristics of the MoS2 FET under dark and illumination corresponding to different VLEG. d The extracted photocurrents (IPH). e 2.5 Hz periodic signals of different amplitudes applied to the LED and f corresponding snapshots of the glowing LED. The LED intensity drops linearly for 5 V > VLED > 2.8 V and exponentially for VLED < 2.8 V in accordance with the output characteristics of the LED, as indicated using the colored circles in (b). g PSD plots obtained from FFT of IDS for a total duration of TP = 51.2 s in different operation regimes in response to periodic LED signals in (e). Peaks observed in the PSD at 2.5 Hz are indications of successful detection of the LED signal. h Extracted SNR in different detection regimes for various LED illuminations. For comparison, we have also included the results obtained from the same experiments performed on a commercial Si photodiode in Supplementary Note 6. i Table summarizing the detection limit for the blue light by MoS2 photodetector and Si photodiode. j Sensitivity of the MoS2 photodetector in different detection regimes. The sensitivity (S) of a photodetector is defined as the ratio of photocurrent (IPH) to the luminous flux (Lϕ). The rated sensitivity of the Si photodiode (S = 9 nA/lx) and its photoresponse to different VLED were used for calibrating Lϕ, which were subsequently used to calculate the sensitivity of MoS2 photodetector. k Comparison of energy expenditure for the Si photodiode and MoS2 photodetector for detection of above threshold signals. The MoS2 photodetector offers orders of magnitude higher energy efficiency when operated in the subthreshold regime, owing to significantly lower dark current.

As expected, the SNR decreases monotonically with the decreasing LED signal intensity for both the Si photodiode and the MoS2 photodetector, irrespective of the biasing regime for the latter. However, a closer look reveals a non-monotonic trend in the SNR for the MoS2 photodetector as a function of VBG for any given LED intensity. This can be explained using the phototransduction mechanism and current transport in monolayer MoS2. Under the illumination of the blue LED (450–500 nm), electron-hole pairs are generated in the MoS2 channel since the incident photon energy exceeds ∼1.84 eV, the optical band gap of the monolayer MoS2. The photoexcited carriers constitute the photocurrent that adds to the channel dark current due to drift under the applied drain bias. In the ON-state, the device dark current obscures the photocurrent generated in response to even the brightest LED signal, i.e., VLED = 5 V, limiting signal detection and reducing the SNR to zero. By operating the device in the subthreshold, the dark current can be reduced exponentially, allowing the detection of low-intensity LED signals, e.g. down to VLED = 3 V. However, as VLED is further reduced, the light intensity from the LED drops exponentially and so does the photocurrent generated in the device, making it difficult to detect the LED signal even in the subthreshold regime. We found that the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector can be extended to VLED = 2.6 V by operating the device in the OFF-state. However, for VLED < 2.6 V, the LED signal is beyond the detection limit irrespective of the operating regime of the MoS2 photodetector.

For a given LED intensity, it is expected that the photocurrent generation in monolayer MoS2 should be constant irrespective of the applied gate bias, as is found in the case of Si photodiode. However, that is clearly not the case according to Fig. 3d, which shows a monotonic decrease in the photocurrent with negative gate biases. This can be explained using carrier trapping at the interface between Al2O3 and MoS2 similar to the SiO2 and MoS2 interface as reported in the literature50. These interface trap states originate from the dangling Al−O bonds at the surface. Photocarriers trapped in these donor-like interface states follow a Fermi−Dirac distribution, with the Fermi level being determined by the equilibrium Fermi level of the MoS2 channel51–53. For larger negative VBG, more trap states become available for carrier capture, leading to a decrease in photocurrent and SNR. Supplementary Note 7 shows the sweep rate-dependent hysteresis in MoS2 FET in dark and under illumination, which highlights the trap-assisted phototransduction mechanism in the subthreshold regime. We also investigated light-enhanced gate leakage in Supplementary Note 8 and found no significant contribution due to the same in the phototransduction mechanism in the monolayer MoS2 photodetector. Nevertheless, the above experiments established VLED > 2.6 V as a detection limit for the MoS2 photodetector.

In comparison, the detection threshold for the Si photodiode was found to be VLED > 2.4 V, below which the reverse dark current dominates, limiting the detection of low-intensity blue light from the distant LED. The rated reverse dark current for the Si photodiode was found to be 2 nA (typical), and 30 nA (maximum). The Si photodiode used in our experiment had a noise floor of ~10 nA. Note that the noise floor of commercially available Si photodiode is almost 4 orders of magnitude higher than what we can achieve in our FET based MoS2 photodetector (noise floor with mean ~3.4 pA and standard deviation of ~4.2 pA). Figure 3j shows the sensitivity of the MoS2 photodetector in different detection regimes. The sensitivity (S) of a photodetector is defined as the ratio of photocurrent (IPH) to the luminous flux (Lϕ). The rated sensitivity of the Si photodiode (S = 9 nA/lx) and its photoresponse to different VLED were used for calibrating Lϕ, which were subsequently used to calculate the sensitivity of the MoS2 photodetector in different detection regimes. As shown in Fig. 3j, while the sensitivity of the MoS2 photodetector exceeds the sensitivity of the Si photodiode in the ON-state, signal detection is comparatively easier using the Si photodiode owing to its low dark current. Similarly, the sensitivity of the MoS2 photodetector is significantly smaller than the Si photodiode in the subthreshold and OFF-state, but signal detection is still possible using the MoS2 photodetector owing to orders of magnitude lower dark current. Finally, Fig. 3k shows the comparison of energy expenditure for the Si photodiode and the MoS2 photodetector for detection of above-threshold signals. The MoS2 photodetector offers orders of magnitude higher energy efficiency when operated in the subthreshold regime, owing to significantly lower dark current. For example, for detecting VLED = 2.8 V, the energy consumed by the MoS2 photodetector is ~470 pJ at VBG = −2 V, compared to 2.8 µJ by the Si photodiode.

Demonstration of SR in monolayer MoS2 photodetector

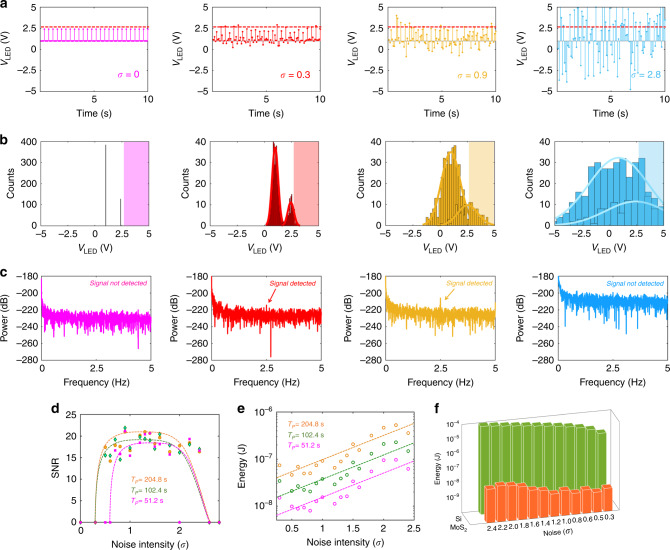

In this section, we will seek to extend the detection limit for the MoS2 photodetector by exploiting SR. Figure 4a shows a 2.5 Hz periodic and subthreshold LED signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V with various amount of Gaussian noise added to it. Figure 4b shows the corresponding histogram of the LED voltage distribution. Note that each histogram shows two Gaussian curves of the same variance but different means, i.e. one centered at VLED = 1 V (LED OFF) and the other one centered at VLED = 2.4 V (Dim LED), marking the level difference between the two states of the LED signal. Figure 4c shows the corresponding PSD obtained using the FFT of the output current (IDS) response from the MoS2 photodetector biased in the OFF-state (VBG = −2 V). The current sampling was done at 10 Hz for ~204.8 s. Clearly, in the presence of a finite and appropriate amount of noise, the subthreshold LED signal is detected.

Fig. 4. Demonstration of SR in monolayer MoS2 photodetector.

a White Gaussian noise of different standard deviations (σ) superimposed on 2.5 Hz periodic and subthreshold LED signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V and b corresponding histogram of the LED voltage distribution. Each histogram shows two Gaussian curves of the same variance but different means, one centered at VLED = 1 V (LED OFF) and the other one centered at VLED = 2.4 V (Dim LED), marking the level difference between the two states of the LED signal. c PSD plots obtained from the FFT of the output current (IDS) measured in the monolayer MoS2 photodetector for a total duration of TP = 204.8 s in response to the LED signals in (a). The MoS2 photodetector was biased in the OFF-state (VBG = −2 V). In the presence of a finite and appropriate amount of noise, the subthreshold LED signal is detected. (see Supplementary video files 1–3 for real-time observation of SR in the MoS2 photodetector). d SNR as a function of σ for different sampling time TP. For very low variance Gaussian noise (σ < 0.2 V), the signal hardly crosses the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, i.e., VLED = 2.6 V. As σ increases, a larger fraction of the LED signal corresponding to the 2.4 V level crosses the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, increasing the SNR. For even larger variances, the SNR starts to decrease since the tail of the Gaussian distribution centered at VLED = 1 V will also start to cross the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, obscuring the periodicity of the VLED = 2.4 V signal. The SNR curves in this instance show the typical SR response found in biological species such as paddlefish, crayfish, etc. e Energy consumption by the MoS2 photodetector is plotted as a function of σ for different TP. Since the MoS2 photodetector was operated in the deep OFF-state (VBG = −2 V) to minimize the dark current, the operating power budget is drastically reduced, making the signal detection extremely energy efficient. For comparison, refer to Supplementary Note 9 for the exploitation of SR using the Si photodiode (see Supplementary video files 4–6 for real-time observation of SR in the Si photodiode). f The energy consumption by the Si photodiode for detecting subthreshold optical signal, exploiting SR, is found to be in the range of a few micro-Joules, which is 1000X higher compared to the MoS2 photodetector for sampling time TP = 100 s.

Supplementary video file 1 shows the real-time recording of the blue LED subjected to a 2.5 Hz periodic signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V and the corresponding PSD of IDS. No peak appears at 2.5 Hz in the PSD, indicating that the photodetector is unable to detect the LED signal. Supplementary video file 2 shows the real-time recording of the blue LED subjected to a random signal with Gaussian noise of standard deviation 0.3 V added to a constant LED signal of VLED = 2.4 V and corresponding PSD of IDS. Even in this case, no peak is observed in the PSD, which is consistent with the random nature of the LED signal. These two videos ensure that neither the weak periodic LED signal nor the noisy LED signal can generate an identifiable response in the MoS2 photodetector. However, Supplementary video file 3 shows that when random Gaussian noise of standard deviation 0.3 V is added to the 2.5 Hz periodic LED signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V, the PSD of IDS starts to show a distinguishable peak at 2.5 Hz, the strength of which increases as the sampling continues. These videos provide direct evidence of SR in the MoS2 photodetector, or, in other words, the constructive role of noise in the detection of the weak periodic signals.

Figure 4d shows the SNR as a function of the variance of the Gaussian noise added to the 2.5 Hz LED signal. For very low variance Gaussian noise (σ < 0.2 V), the signal hardly crosses the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, i.e., VLED = 2.6 V, as can be seen from the histogram in Fig. 4b. As the variance of the noise increases, a larger fraction of the LED signal corresponding to the 2.4 V level crosses the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, enhancing the SNR. For even larger variances, the SNR starts to decrease since the tail of the Gaussian distribution centered at VLED = 1 V will also start to cross the detection threshold of the MoS2 photodetector, obscuring the periodicity of the VLED = 2.4 V signal. The SNR curves show the typical SR response found in biological species such as paddlefish, crayfish, etc. Note that irrespective of the nature of the periodic signal and its background, the SNR can be increased by increasing the total sampling time (TP) for the appropriate noise variance. Finally, Fig. 4e shows the energy consumption by the device for detecting the weak periodic LED signal. Since the MoS2 photodetector was operated in the deep OFF-state (VBG = −2 V) to minimize the dark current, the operating power budget is drastically reduced, making the signal detection extremely energy efficient. In the present case, the energy dissipation was as frugal as few nano-Joules.

In Supplementary Note 9, we exploit SR for extending the detection limit of a commercially available Si photodiode. Supplementary video file 4 shows the real-time recording of the blue LED subjected to a 2.5 Hz periodic signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V and the corresponding PSD of the reverse bias current (IPD) measured in the Si photodiode, which is placed at ~1 cm from the LED. No peak appears at 2.5 Hz in the PSD, indicating that the Si photodiode is unable to detect the LED signal. Supplementary video file 5 shows the real-time recording of the blue LED subjected to a random signal with Gaussian noise of standard deviation 0.4 V added to a constant LED signal of VLED = 2.4 V and corresponding PSD of IPD. Even in this case, no peak is observed in the PSD, which is consistent with the random nature of the LED signal. These two videos ensure that neither the weak periodic LED signal nor the noisy LED signal can generate an identifiable response in the Si photodiode. However, Supplementary video file 6 shows that when random Gaussian noise of standard deviation 0.4 V is added to the 2.5 Hz periodic LED signal of amplitude VLED = 2.4 V, the PSD of IDS starts to show a distinguishable peak at 2.5 Hz, the strength of which increases as the sampling continues. These videos provide direct evidence of SR in the Si photodiode. The energy consumption by the Si photodiode for detecting subthreshold optical signal, exploiting SR, is found to be in the range of a few micro-Joules, which is ~1000× higher compared to that of the MoS2 photodetector. This is due to the fact that the reverse dark current in Si photodiode is orders of magnitude higher than the subthreshold conduction current of the MoS2 FET.

Note that in the above experimental demonstration of SR in the MoS2 photodetector, the white Gaussian noise was added to the original LED driving voltage to bring the signal randomly above the detection limit of the MoS2 photodetector. Therefore, it may appear that the noise has to be in the nature of the signal, which may restrict the use of SR in many real-life applications. This is not true. Supplementary Note 10 shows that noise can be added externally to aid the subthreshold signal detection. The experimental setup consisted of the MoS2 photodetector and two blue LEDs, one of which is used as the source of the weak periodic signal (referred to as the “Signal” LED) and the other one as the source of the white Gaussian noise (referred to as the “Noisy” LED). Supplementary video file 7 shows the real-time recording of a 2.5 Hz periodic signal alternating between VLED = 1.0 V and VLED = 2.6 V applied to the “Signal” LED and the corresponding PSD of IDS. No peak appears at 2.5 Hz in the PSD, indicating that the MoS2 photodetector is unable to detect the LED signal. Supplementary video file 8 shows the real-time recording of the “Noisy” LED subjected to white Gaussian noise of standard deviation 0.1 V and mean of VLED = 2.5 V and the corresponding PSD of IDS. As expected, no peak is observed in the PSD due to the random nature of the “Noisy” LED signal. Interestingly, Supplementary video file 9 shows that a peak appears at 2.5 Hz when the “Signal” LED operates in the presence of the “Noisy” LED. Clearly, the weak periodic signal from the “Signal” LED is detected by the MoS2 photodetector only in the presence of the “Noisy” LED and the enhancement in the signal to noise ratio (SNR) increases with increasing sampling time. This experiment conclusively proves that the noise does not need to be in the source of the signal and can be added and adjusted using a separate source that can be integrated with the photodetector. This certainly comes with an energy overhead, although miniscule, in the range of several hundreds of nano-Joules, since the “Noisy” LED must be powered separately. Nevertheless, the above demonstration expands the scope of SR and makes it even more appealing for numerous real-life applications.

Discussion

While SR has shown evolutionary success in various natural sensors, ensuring the survival of species in resource-constrained environments, its benefits have remained largely underexplored in solid-state sensors. This is not surprising since conventional approaches have been widely successful although power hungry and resource intensive. However, with the emergence of newer technologies, such as the IoT, that demand energy-efficient sensors, deployable in remote locations without continuous source of electrical energy, the time has come to rekindle the concept of SR. Here we have demonstrated how SR can be exploited in monolayer MoS2 based photodetector to detect ultra-low intensity optical signals from a distant LED, which are otherwise below the detection threshold. We have also demonstrated the significant energy benefits of utilizing SR for photodetection. We reemphasize that SR does not need to be a standalone technology. Instead, as we have shown, SR can be used to extend the detection limit of existing state-of-the-art sensors, such as commercially available Si photodiodes. We have also demonstrated that the noise does not need to be in the nature of the signal and can be tuned and added externally. Overall, our approach differs from conventional thinking since we harness noise instead of suppressing it for detecting subthreshold signals. This can mark a paradigm shift in future high precision and ultra-low-power sensor design. Our approach is simple and generic, and can be extended to practically any sensors used in commercial or defense-related applications, where energy and resources are not abundant.

Methods

Synthesis of monolayer MoS2

Monolayer MoS2 was deposited on epi-ready 2” c-sapphire substrate by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). An inductively heated graphite susceptor equipped with wafer rotation in a cold-wall horizontal reactor was used to achieve uniform monolayer deposition (schematic in Fig. 1a) as previously described54. Molybdenum hexacarbonyl (Mo(CO)6) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) were used as precursors. Mo(CO)6, maintained at 10 °C and 950 Torr in a stainless steel bubbler, was used to deliver 0.036 sccm of the metal precursor for the growth, while 400 sccm of H2S was used for the process. MoS2 deposition was carried out at 1000 °C and 50 Torr in H2 ambient, where monolayer growth was achieved in 18 min. The substrate was first heated to 1000 °C in H2 and maintained for 10 min before the growth was initiated. After growth, the substrate was cooled in H2S to 300 °C to inhibit decomposition of the MoS2 films.

Characterization of monolayer MoS2

Surface coverage and thickness were measured using peak-force tapping mode in a Bruker Icon AFM using scanasyst AFM tips with a nominal tip radius of ∼2 nm and a spring constant of 0.4 N/m. Raman and PL measurements were performed using a HORIBA LabRAM HR Evolution Raman microscope with laser wavelengths of 532 nm. Raman spectra were collected with 1800 grooves per mm grating, while PL measurements were conducted with 300 grooves per mm grating. The Raman and PL maps were acquired over a 5 × 5 µm2 area. X-ray diffraction characterization of MoS2 films was carried out with a PANalytical MRD diffractometer with a 5-axis cradle. X-rays were generated in a standard Cu anode X-ray tube operated at 40 kV accelerating voltage and 45 mA filament current. Cu K line was filtered by a mirror with 1/4° slit and Ni filter on the primary beam side. On the diffracted beam side, an 0.27° parallel plate collimator with 0.04 rad Soller slits with PIXcell detector in open detector mode was employed. Samples' surface was ~2–4° away from the X-ray incidence plane such that diffraction caused by the (h k i 0) planes, to determine the in-plane epitaxial relation of the film with respect to a substrate, could be measured35.

Transfer of monolayer MoS2

To fabricate the MoS2 FETs, MoS2 film grown on sapphire was transferred onto alumina substrate using PMMA (polymethyl-methacrylate) assisted wet transfer process. MoS2 on sapphire substrate was spin coated with PMMA and then baked at 180 °C for 90 s. The corners of the spin-coated film were scratched using a razor blade and immersed inside 1 M NaOH solution kept at 90 °C. Capillary action causes the NaOH to be drawn into the substrate/film interface, separating the PMMA/MoS2 film from the sapphire substrate. The separated film was rinsed multiple times inside a water bath and finally transferred onto the 50 nm alumina substrate and then baked at 50 °C and 70 °C for 10 min each to remove moisture and residual PMMA, ensuring a pristine interface.

Gate dielectric fabrication

Direct replacement of thermally oxidized SiO2 with a high-κ dielectric such as Al2O3 grown via ALD is a logical choice to scale the effective oxide thickness (EOT). However, we found that Al2O3/p++-Si interface is not ideal for back-gated FET fabrication owing to higher gate leakage current, more interface trap-states, and large hysteresis, which negatively impact the performance of the device. Replacing Si with Pt, a large work function metal (5.6 eV), allows minimal hysteresis and trap state effects55. Since Pt readily forms a Pt silicide at temperatures as low as 300 °C, a 20 nm TiN diffusion barrier deposited by reactive sputtering was placed between the p++ Si and the Pt, permitting subsequent high-temperature processing56. This conductive TiN diffusion barrier allows the back-gate voltage to be applied to the substrate, thus simplifying the fabrication and measurement procedures. The polycrystalline Pt introduces very little surface roughness to the final Al2O3 surface, with a rms roughness of 0.7 nm.

Device fabrication

Back-gated FETs were fabricated using e-beam lithography. To define the channel region, the substrate was spin-coated with PMMA and baked at 180 °C for 90 s. The photoresist was then exposed to e-beam and developed using 1:1 mixture of 4-methyl-2-pentanone (MIBK) and 2 propanols (IPA). The monolayer MoS2 film was subsequently etched using sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) at 5 °C for 30 s. Next, the sample was rinsed in acetone and IPA to remove the photoresist. In order to fabricate the source/drain contacts, the substrate was again spin-coated with MMA and PMMA, followed by the e-beam lithography, developing using MIBK and IPA, and e-beam evaporation of a 40 nm Ni/30 nm Au stack. Finally, the photoresist was rinsed away by lift-off process using acetone and IPA.

Electrical measurements

Electrical measurements were performed in air inside a Lakeshore probe station using a B1500A Keysight semiconductor parameter analyzer.

Supplementary information

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge scientific discussions with Prof. Sahin K Ozdemir. The work was partially supported by Army Research Office (ARO) through Contract Number W911NF1920338. Authors also acknowledge the support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) through the Pennsylvania State University 2D Crystal Consortium–Materials Innovation Platform (2DCCMIP) under NSF cooperative agreement DMR-1539916.

Author contributions

S.D. conceived the idea, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. S.D., A.D., and A.O. performed the stochastic resonance related experiments, analyzed the data, discussed the results, agreed on their implications. A.S. fabricated the MoS2 photodetectors. T.C. and J.M.R. synthesized and characterized MoS2 monolayers. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes used for plotting the data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviews for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Akhil Dodda, Aaryan Oberoi.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18195-0.

References

- 1.Wiesenfeld K, Moss F. Stochastic resonance and the benefits of noise: from ice ages to crayfish and SQUIDs. Nature. 1995;373:33. doi: 10.1038/373033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolis C. Long-term climatic transitions and stochastic resonance. J. Stat. Phys. 1993;70:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benzi R, Sutera A, Vulpiani A. The mechanism of stochastic resonance. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 1981;14:L453. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglass JK, Wilkens L, Pantazelou E, Moss F. Noise enhancement of information transfer in crayfish mechanoreceptors by stochastic resonance. Nature. 1993;365:337. doi: 10.1038/365337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell DF, Wilkens LA, Moss F. Use of behavioural stochastic resonance by paddle fish for feeding. Nature. 1999;402:291. doi: 10.1038/46279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin JE, Miller JP. Broadband neural encoding in the cricket cereal sensory system enhanced by stochastic resonance. Nature. 1996;380:165. doi: 10.1038/380165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbs A, et al. Stochastic resonance in a superconducting loop with a Josephson junction. J. Appl. Phys. 1995;77:2582–2590. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantegna R, Spagnolo B. Stochastic resonance in a tunnel diode. Phys. Rev. E. 1994;49:R1792. doi: 10.1103/physreve.49.r1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNamara B, Wiesenfeld K, Roy R. Observation of stochastic resonance in a ring laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988;60:2626. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fauve S, Heslot F. Stochastic resonance in a bistable system. Phys. Lett. A. 1983;97:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gammaitoni L, Hänggi P, Jung P, Marchesoni F. Stochastic resonance. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1998;70:223. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freund JA, et al. Behavioral stochastic resonance: how the noise from a Daphnia swarm enhances individual prey capture by juvenile paddlefish. J. Theor. Biol. 2002;214:71–83. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezrukov SM, Vodyanoy I. Noise-induced enhancement of signal transduction across voltage-dependent ion channels. Nature. 1995;378:362–364. doi: 10.1038/378362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng F-G, Fu Q-J, Morse R. Human hearing enhanced by noise. Brain Res. 2000;869:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins, J. J., Imhoff, T. T. & Grigg, P. Noise-enhanced tactile sensation. Nature383, 770 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Simonotto E, et al. Visual perception of stochastic resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:1186. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priplata A, et al. Noise-enhanced human balance control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dykman M, et al. Noise‐enhanced optical heterodyning in an all‐optical bistable system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1995;67:308–310. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gammaitoni L, Martinelli M, Pardi L, Santucci S. Observation of stochastic resonance in bistable electron-paramagnetic-resonance systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991;67:1799. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawahara T, et al. Robust noise modulation of nonlinearity in carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;49:02BD11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakamata Y, Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Inoue K, Matsumoto K. Robust noise characteristics in carbon nanotube transistors based on stochastic resonance and their summing networks. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;50:06GE03. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee I, Liu X, Zhou C, Kosko B. Noise-enhanced detection of subthreshold signals with carbon nanotubes. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2006;5:613–627. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiguchi K, Fujiwara A. Detecting signals buried in noise via nanowire transistors using stochastic resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;101:193108. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasai S, Shiratori Y, Miura K, Nakano Y, Muramatsu T. Control of stochastic resonance response in a GaAs‐ based nanowire field‐ effect transistor. Phys. Status Solidi C. 2011;8:384–386. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiguchi K, Fujiwara A. Single-electron stochastic resonance using si nanowire transistors. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;50:06GF04. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasai S, Asai T. Stochastic resonance in Schottky wrap gate-controlled GaAs nanowire field-effect transistors and their networks. Appl. Phys. Express. 2008;1:083001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki Y, Asakawa N. Robust thresholdlike effect of internal noise on stochastic resonance in an organic field-effect transistor. Phys. Rev. E. 2018;97:012217. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.97.012217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler SZ, et al. Progress, challenges, and opportunities in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2898–2926. doi: 10.1021/nn400280c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhimanapati GR, et al. Recent advances in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano. 2015;9:11509–11539. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das S, Robinson JA, Dubey M, Terrones H, Terrone M. Beyond graphene: progress in novel two-dimensional materials and van der Waals solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2015;45:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mak KF, Lee C, Hone J, Shan J, Heinz TF. Atomically thin MoS(2): a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:136805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulman DS, Arnold AJ, Das S. Mobility Deception in Nanoscale Transistors: An Untold Contact Story. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1806020. doi: 10.1002/adma.201806020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang K, et al. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature. 2015;520:656. doi: 10.1038/nature14417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhury TH, et al. Chalcogen precursor effect on cold-wall gas-source chemical vapor deposition growth of WS2. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018;18:4357–4364. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chubarov M, Choudhury TH, Zhang X, Redwing JM. In-plane X-ray diffraction for characterization of monolayer and few-layer transition metal dichalcogenide films. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:055706. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aaa1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang F, Erb C, Runkle L, Zhang X, Alem N. Etchant-free transfer of 2D nanostructures. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:025602. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aa9c21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, et al. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: evolution of Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22:1385–1390. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sebastian A, et al. Electrochemical Polishing of Two-Dimensional Materials. ACS Nano. 2019;13:78–86. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tongay S, et al. Defects activated photoluminescence in two-dimensional semiconductors: interplay between bound, charged, and free excitons. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2657. doi: 10.1038/srep02657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das S, Chen HY, Penumatcha AV, Appenzeller J. High performance multilayer MoS2 transistors with scandium contacts. Nano Lett. 2013;13:100–105. doi: 10.1021/nl303583v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulman, D. S., Arnold, A. J. & Das, S. Contact engineering for 2D materials and devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 3037–3058 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Taur, T. & Ning, T. H. Fundamentals of Modern VLSI Devices. (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- 43.Lundstrom MS, Antoniadis DA. Compact models and the physics of nanoscale FETs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices. 2013;61:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sebastian A, Pannone A, Radhakrishnan SS, Das S. Gaussian synapses for probabilistic neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4199. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12035-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das S, Dodda A, Das S. A biomimetic 2D transistor for audiomorphic computing. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3450. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11381-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasai, S. et al. THz wave detection by gate-controlled GaAs nanowire devices. OECC 2010 Tech. Digest 530–531 (2010).

- 47.Mak KF, Shan J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics. 2016;10:216. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang QH, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kis A, Coleman JN, Strano MS. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7:699. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baugher BW, Churchill HO, Yang Y, Jarillo-Herrero P. Optoelectronic devices based on electrically tunable p-n diodes in a monolayer dichalcogenide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:262–267. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furchi MM, Polyushkin DK, Pospischil A, Mueller T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 2014;14:6165–6170. doi: 10.1021/nl502339q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Bartolomeo A, et al. Hysteresis in the transfer characteristics of MoS2 transistors. 2D Mater. 2017;5:015014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnold AJ, et al. Mimicking neurotransmitter release in chemical synapses via hysteresis engineering in MoS2 transistors. ACS Nano. 2017;11:3110–3118. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Late DJ, Liu B, Matte HS, Dravid VP, Rao CN. Hysteresis in single-layer MoS2 field effect transistors. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5635–5641. doi: 10.1021/nn301572c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xuan Y, et al. Multi-scale modeling of gas-phase reactions in metal-organic chemical vapor deposition growth of WSe2. J. Cryst. Growth. 2019;527:125247. [Google Scholar]

- 55.CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 98th Edition (Internet Version 2018) ed. Boca (CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Raton, FL, 2018).

- 56.Crider CA, Poate JM, Rowe JE, Sheng TT. Platinum silicide formation under ultrahigh-vacuum and controlled impurity ambients. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:2860–2868. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The codes used for plotting the data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.