Abstract

Objectives

To improve understanding of transition from viral infection to viral clearance, and antibody response in pediatric patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Study design

This retrospective analysis of children tested for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunoglobulin G antibody at a quaternary-care, free-standing pediatric hospital between March 13, 2020, and June 21, 2020, included 6369 patients who underwent PCR testing and 215 patients who underwent antibody testing. During the initial study period, testing focused primarily on symptomatic children; the later study period included asymptomatic patients who underwent testing as preadmission or preprocedural screening. We report the proportion of positive and negative tests, time to viral clearance, and time to seropositivity.

Results

The rate of positivity varied over time due to viral circulation in the community and transition from targeted testing of symptomatic patients to more universal screening of hospitalized patients. Median duration of viral shedding (RT-PCR positivity) was 19.5 days and time from RT-PCR positivity to negativity was 25 days. Of note, patients aged 6 through 15 years demonstrated a longer time of RT-PCR positivity to negativity, compared with patients aged 16 through 22 years (median 32 vs 18 days, P = .015). Median time to seropositivity, by chemiluminescent testing, from RT-PCR positivity was 18 days, whereas median time to reach adequate levels of neutralizing antibodies (defined as comparable with 160 titer by plaque reduction neutralization testing) was 36 days.

Conclusions

The majority of patients demonstrated a prolonged period of viral shedding after infection with SARS CoV-2. It is unknown whether this correlates with persistent infectivity. Only 17 of 33 patients demonstrated adequate neutralizing antibodies during the time frame of specimen collection. It remains unknown whether immunoglobulin G antibody against spike structured proteins correlates with immunity, and how long antibodies and potential protection persist.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19, children, age, sex

Abbreviations: ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IgG, Immunoglobulin G; max, Maximum; min, Minimum; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; RBD, Receptor binding domain; RT, Reverse transcription; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

See related article, p 45

In December 2019, a series of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases caused by a novel strain of coronavirus, believed to have originated from bats, was described in Wuhan, Hubei province of China.1 The pathogen demonstrated a significant degree of genetic homology to the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus from the 2002-2004 outbreak. The virus strain was designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the disease was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, after the number of affected cases had increased significantly and the disease was observed in more than 100 countries.2

SARS-CoV-2 has similar structural proteins present in other coronaviruses, consisting of spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) components.3 , 4 Of these glycoproteins, virus–cell fusion of SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by the trimeric structure of the 2 functional subunits of the S protein, namely S1 and S2, after binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).5 Antibodies formed against the receptor binding domain (RBD) on the S1 subunit have the potential to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by disabling virus-ACE2 binding and endocytosis.6 , 7 In addition, the competitive RBD binding capacity of these antibodies vs ACE2 correlates with neutralizing activity.6

Dong et al8 reported epidemiologic results on 728 children with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from China. The authors found that the median age was 7 years, >90% of the cases had a disease spectrum ranging from asymptomatic to moderate disease, and the proportion of severe and critical cases increased with age.8 Subsequently, similar findings have been reported from Europe, the Middle East, and the US.9, 10, 11, 12

Although there are emerging data regarding timing of viral clearance and immunologic response in adults with COVID-19,13 there are few data in the pediatric population. Furthermore, knowledge of factors affecting time-to-seropositivity is lacking in both pediatric and adult patients.14 We report viral and antibody test results from our pediatric patient population to contribute to a better understanding of timing of viral clearance and antibody production in children with COVID-19.

Methods

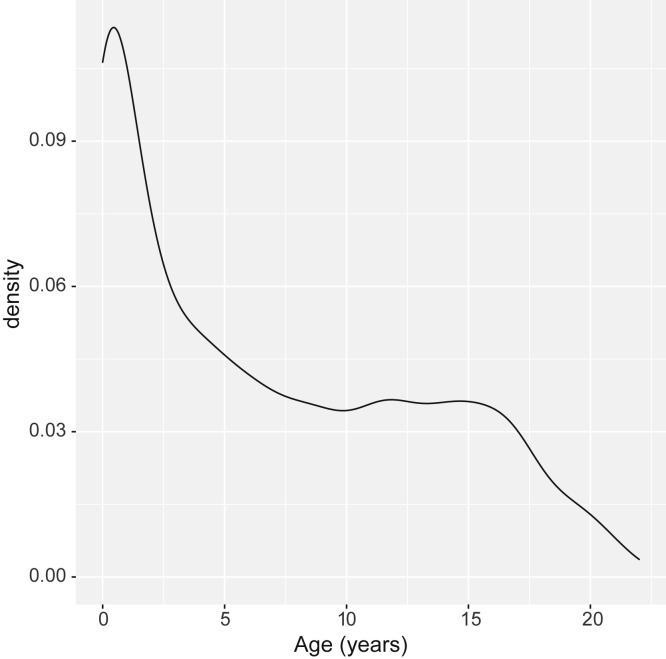

From March 13, 2020, to June 21, 2020, all patients seeking care at the Children's National Hospital, Washington, DC, who were aged ≤22 years and were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were included in the study. Data were extracted from our laboratory information systems data warehouse (Sunquest Information Systems Database, Tucson, Arizona and Vertica Analytics Platform, Cambridge, Massachusetts) using Viewics Analytics Platform (Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana) with Structured Query Language queries. Extracts were merged into comma-separated value files and imported into RStudio IDE (Boston, Massachusetts). In addition to the RT-PCR results, qualitative and quantitative serologic test results, age, and sex also were included in the data extracts. Age stratification was defined as 0 through 5 years, 6 through 15 years, and 16 through 22 years (Figure 1 [available at www.jpeds.com] shows kernel density estimate of age).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of the patients who underwent molecular and serology testing.

Virus Detection

Nasopharyngeal samples were collected from patients. Samples were transferred to the laboratory in viral transport medium as recommended by the manufacturer or in liquid Amies medium as validated by the laboratory. For detection of the virus by RT-PCR, 4 systems were used due to high testing volume, which were GenMark ePlex SARS-CoV-2 Test (GenMark, Diagnostics, Carlsbad, California), DiaSorin Molecular Simplexa COVID-19 Direct Assay System (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy), Cepheid Xpert Xpress-SARS-CoV-2 (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California), and Seegene Allplex 2019-nCoV RT-PCR Assay (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea). All were validated in our laboratory and considered equivalent for patient testing. Viral clearance was deemed as RT-PCR negativity.

The GenMark ePlex SARS-CoV-2 Test is an automated qualitative nucleic acid test that aids in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and diagnosis of COVID-19 using The True Sample-to-Answer Solution ePlex instrument. The test is based on nucleic acid amplification technology and each test cartridge includes all reagents needed to extract, amplify, and detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal swab samples.15

The DiaSorin Molecular Simplexa COVID-19 Direct Assay System is a real-time RT-PCR system that enables the direct amplification of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs. Fluorescent probes are used together with corresponding forward and reverse primers to amplify SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA and internal control RNA. The assay targets 2 different regions of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, ORF1ab, and S gene. The S gene encodes the spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 and is also targeted to specifically detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2. The ORF1ab region encodes well-conserved nonstructural proteins and therefore is less susceptible to recombination. An RNA internal control is used to detect RT-PCR failure and/or inhibition.15

The Cepheid Xpert Xpress-SARS-CoV-2 is a real-time RT-PCR assay designed to detect SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids from upper respiratory samples. Specific molecular targets include the E and N2 genes. The GeneXpert platform uses a closed cartridge system that does not require separate extraction or processing steps before introduction of the sample and can yield rapid results within 30 minutes. Each cartridge contains internal sample processing and probe check controls.15

The Seegene Allplex 2019-nCoV RT-PCR Assay detects SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids in upper respiratory samples. The probes are designed to target the E, N, and RdRp (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) genes. A separate nucleic acid extraction step is required before amplification via real-time PCR. High-throughput analysis is enabled through use of 96-well plates. Internal positive and negative controls are used to confirm the validity of each PCR run.15

Antibody Detection

Antibody detection was performed from serum or plasma samples, collected in appropriate separator tubes, using DiaSorin Liaison XL SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) S1/S2 assay (DiaSorin). We validated the analytical and clinical performance of this assay with similar outcomes as other researchers who previously reported satisfactory results.16 , 17 The test is based on chemiluminescent detection of antibodies against S1 and S2 glycoproteins of the virus using magnetic beads. Seropositivity was defined at presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies ≥15 absorbance units per milliliter (AU/mL), as recommended by the manufacturer. In addition to the qualitative results, quantitative test results also were included to reflect the amount of circulating IgG antibodies in patient samples at the time of blood draw. As demonstrated by the manufacturer, antibody results ≥80 AU/mL were comparable to a titer of 160 by plaque reduction neutralization testing (Liaison SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG [REF 311450]). According to these criteria, results were grouped as “adequate for neutralization” and “not adequate for neutralization,” based on the 80 AU/mL threshold. In addition to routine testing ordered by clinical providers (n = 194), we retrieved available leftover serum or plasma samples from patients who underwent RT-PCR testing but were not tested for antibodies (n = 19). Serologic testing also was performed on these samples and their results were included in the present study.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Survival (version 3.2-3) and SurvMiner (version 0.4.7) packages were used for nonparametric estimation of time to event function. Interval censoring was present since timing of symptom onset was not included as a variable (left censoring) and patients were tested at the discretion of the healthcare provider and exact event times could not be obtained (right censoring). Follow-up time for patients included RT-PCR positivity duration (censored time), initial RT-PCR positivity to RT-PCR negativity (event time), initial RT-PCR positivity to seronegativity (censored time), and initial RT-PCR positivity to seropositivity (event time). These time points were used in event probability estimates using the Kaplan–Meier method and Peto & Peto modification of the Gehan–Wilcoxon test for comparison of groups.

Statistical significance was defined at a P value of <.05. Bonferroni adjustments were made to P values for pairwise comparisons. Results were expressed in mean ± SD, median and first and third IQRs or minimum (min) and maximum (max), and with 95% CI, as appropriate.

This project was undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at Children's National Hospital and therefore does not constitute human research. As such, it was not under the oversight of the institutional review board. This manuscript was evaluated and approved by the institutional publication review committee.

Results

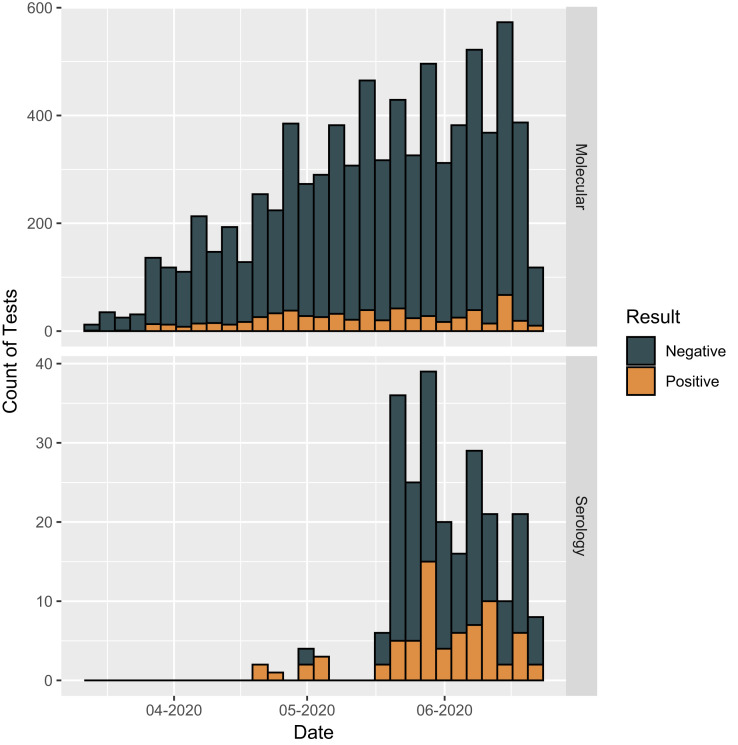

The total number of RT-PCR tests performed over the 100-day period was 7958, with 641 positive test results (Figure 2 ). Figure 3 shows the number of patients at each stage of the study; 592 patients tested positive with a median test of 1 per patient (max = 6). For the 5777 patients who tested negative, the median per patient was 1 (min = 1, max = 15). A total of 238 serologic tests were performed with 69 positive test results. Overall, 58 patients tested positive with a median per patient test of 1 (max = 2) and 157 patients tested negative with a median test per patient of 1 (max = 5).

Figure 2.

Number of molecular (RT-PCR) and serologic tests performed during the study period.

Figure 3.

Participant flow in the study.

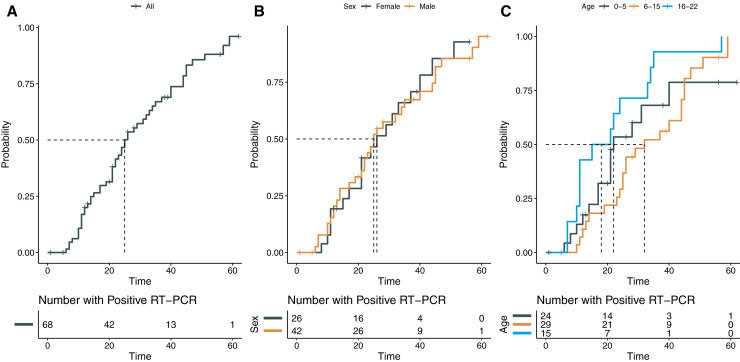

Sixty-eight patients had more than 1 molecular detection test performed. The median duration of viral shedding (RT-PCR positivity) was 19.5 days (IQR = 12-39), with 10 patients demonstrating a duration greater than 30 days (max = 62 days). The median time from RT-PCR positivity to RT-PCR negativity was 25 days (95% CI 22-34) (Figure 4, A). No difference was found between female patients (median = 26 days) and male patients (median = 25 days) for time to RT-PCR negativity (χ2 = 0, P = 1) (Figure 4, B); however, statistical significance was found between age groups (χ2 = 7.4, P = .02). Patients aged 6 through 15 years had longer time to achieve RT-PCR negativity (median = 32 days) compared with those 16 through 22 years of age (median = 18 days) (P = .015) (Figure 4, C). Patients in the 0- through 5-year age group had a median of 22 days to RT-PCR negativity, but pairwise comparisons of this group with other groups were not significant (vs 6 through 15 years: P = .76; vs 16 through 22 years: P = .52). After adjustment for sex, time to RT-PCR negativity was found to be longer only for female patients (n = 10, median = 44 days) in the 6- through 15-year age group because male patients (n = 19) in this age cohort demonstrated a median period of 25.5 days (P = .02). Comparisons of time to RT-PCR negativity for male patients aged 6-15 years with other groups were not significant (all P > .05).

Figure 4.

Time-to-event curves for RT-PCR positivity to negativity.

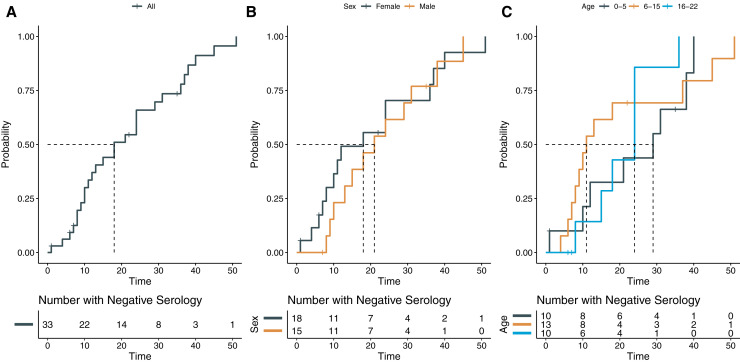

The median time from RT-PCR positivity to seropositivity (ie, antibody detection) was 18 days (95% CI 12-31) (Figure 5, A). No difference in time to seropositivity was found between female patients (median = 18 days) and male patients (median = 21 days) (χ2 = 0.8, P = .4) (Figure 5, B). The median number of days for seroconversion from initial RT-PCR positivity was 29 days for the 0- through 5-year age group, 11 days for the 6- through 15-year age group, and 24 days for the 16- through 22-year age group and overall comparison of age groups did not demonstrate a significant difference (χ2 = 1.6, P = .4) (Figure 5, C). After adjustment for sex, the various age groups also did not demonstrate significant differences in time to seropositivity (χ2 = 0.6, P = .7). Only 17 of 33 patients demonstrated antibody levels ≥80 AU/mL, adequate levels of neutralizing antibodies as defined by the manufacturer, the median time to reach such a level in the 17 patients in this study was 36 days (95% CI 18-not available) (Figure 6, A). No significance was found for sex (χ2 = 1.1, P = .3) (Figure 6, B), age (χ2 = 0.9, P = .6), or age stratified for sex (χ2 = 1.7, P = .4) (Figure 6, C).

Figure 5.

Time-to-event curves for RT-PCR positivity to seropositivity (Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody ≥15 AU/mL).

Figure 6.

Time-to-event curves for RT-PCR positivity to reach neutralizing antibody levels (Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody ≥80 AU/mL).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that IgG class antibodies directed against S1 and S2 glycoproteins could be detected in blood samples of children before viral clearance. Previous studies revealed that antibodies bound to the RBD epitope of SARS-CoV-2's S1 glycoprotein are able of disrupting the virus-ACE2 interaction, thus blocking viral entry into human cells and demonstrating neutralizing capacity.6 Although the RBD is located on the S1 subunit, the S2 subunit plays a crucial role in membrane fusion of the virus by conformation changes.18 , 19 It was previously hypothesized for SARS-CoV-1 that multiple antibodies targeting different epitopes might act synergistically.20 , 21 As noted earlier, the antibody detection assay used in this study does not only measure antibodies targeting RBD but also includes all antibodies to epitopes on S1 and S2 glycoproteins. We propose that this assay design may be beneficial in assessing antibody response in individuals with a polyclonal immune response to both S1 and S2 antigens with synergistic antiviral activity.

Most of the SARS-CoV-2 literature related to viral kinetics focuses on adults with moderate to severe COVID-19. Han et al22 observed 12 children with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 and reported gradual viral load decrease in nasopharyngeal samples from 100% to 55% positivity over 3 weeks, a finding that is comparable with our median period of 25 days for achieving nasopharyngeal RT-PCR negativity. Fafi-Kremer et al23 reported immunologic responses of 160 healthcare workers with mild or subclinical COVID-19 and demonstrated that even mild cases were usually, but not always, characterized by formation of neutralizing antibodies, with an increase in neutralization activity over time. The authors reported that the variables associated with high neutralizing activity in a multivariate model included time from symptom onset to blood sampling, high body mass index, and male sex.23 We demonstrated that female patients from 6 through 15 years had a longer period to viral clearance compared with other groups. This may be due to the age-dependent expression of ACE2 in the nasal epithelium, as demonstrated by Bunyavanich et al,24 where ACE2 gene expression was found to be significantly greater in older children (10 through 17 years) compared with younger children (<10 years). Furthermore, it was suggested that gonadal hormones play a role in ACE2 expression and function.25 Taken together, increased duration of SARS-CoV-2 in the nasopharyngeal area could be an effect of hormonal changes in adolescent female patients in this age group. As noted by Chun et al,26 different sections of the airway feature variable expression of ACE2, and prolonged presence of the viral genome in the upper respiratory tract may not correlate with the severity of COVID-19.

A strength of our study was the inclusion of patients from multiple pediatric age groups with sequential PCR testing, which permitted comparison between age groups and sexes. One patient demonstrated RT-PCR positivity 62 days after the initial positive test result. Results of serial testing in pediatric patients have been reported rarely to date. In a case series of 50 children, only 4 had repeat testing performed, and 1 patient demonstrated continued positivity 27 days after initial RT-PCR positivity.27 In the adult population, retrospective evaluation of 191 adult patients from Wuhan reported the longest duration of viral shedding to be 37 days, with a median of 20 days.28 It should be noted that detection of viral particles by molecular testing may not correlate with viable virus and transmissibility.29

For COVID-19, antibody competition with ACE2, the intended target of SARS-CoV-2, and binding affinity of the antibody for RBD are critical to neutralization of the virus.6 We demonstrated that the virus can be detected in nasopharyngeal samples with low levels of circulating antibody but becomes undetectable when levels reach neutralizing levels. This suggests that quantitative antibody results may be more useful for clinical management of patient. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted an Emergency Use Authorization to multiple virus detection and serologic tests for diagnosis and management of COVID-19.15 However, serologic assays for SARS-CoV-2 are still in early phases of development. As of July 26, 2020, no commercial assay was cleared by FDA for quantitative reporting of the results.15 In the present study, we showed that time to reach a quantitative result corresponding to a plaque reduction neutralizing antibody titer of 160 was associated with time to viral clearance. This titer cut point also has been recommended by the FDA to identify potential convalescent plasma donors. However, it has been observed in the setting of other viral infections that seropositivity or antibody response may not correlate to immunity to the virus and that disease progression or reinfection is still possible. Tang et al30 reported that humoral immunity mounted against SARS-CoV-2 gradually decreased over time and disappeared due to the lack of peripheral memory B-lymphocyte response in most individuals.

This study has a number of limitations, which include its retrospective nature and timing of virus detection and antibody testing being at the discretion of the ordering provider rather than at defined time intervals. We have not included symptom onset in our analysis because this project was solely based on laboratory data evaluation. In addition, the serologic assay used in the study had 94.3% positive and 100% negative agreement with a comparative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Given the low optimal positive agreement, some false-negative test results are expected.

Given the significant volume of testing performed, our study provides a timeline of viral clearance and humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 in pediatric patients, with through comparisons among age groups and sexes. We demonstrated that female patients aged 6 through 15 years had longer persistence of viral genome in nasopharyngeal samples. It should be noted that presence of viral genome may not correlate with transmissibility. Antibodies were detectable in low titer preceding viral clearance. The timing of antibodies reaching titers that correlate with potentially neutralizing levels coincided with RT-PCR negativity in nasopharyngeal samples within a 24- to 25-day period after initial RT-PCR positivity. However, only approximately 50% (17/33 of patients) achieved adequate antibody level at some point during the timeframe of specimen testing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Freeman for sample collection and Celia Grant, MT (ASCP) for helping with the implementation of the serological testing.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and did not receive any funding.

Appendix

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ju B., Zhang Q., Ge J., Wang R., Sun J., Ge X. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature. 2020;584:115–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Y., Mo X., Hu Y., Qi X., Jiang F., Jiang Z. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garazzino S., Montagnani C., Dona D., Meini A., Felici E., Vergine G. Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000600. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenforde M.W., Billig Rose E., Lindsell C.J., Shapiro N.I., Files D.C., Gibbs K.W. Characteristics of adult outpatients and inpatients with COVID-19—11 academic medical centers, United States, March-May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:841–846. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6926e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soltani J., Sedighi I., Shalchi Z., Sami G., Moradveisi B., Nahidi S. Pediatric coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): an insight from west of Iran. North Clin Istanb. 2020;7:284–291. doi: 10.14744/nci.2020.90277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBiasi R.L., Song X., Delaney M., Bell M., Smith K., Pershad J. Severe coronavirus disease 2019 in children and young adults in the Washington, DC metropolitan region. J Pediatr. 2020;223:199–203.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethuraman N., Jeremiah S.S., Ryo A. Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;323:2249–2251. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorizations. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices Accessed July 26, 2020.

- 16.Tré-Hardy M., Wilmet A., Beukinga I., Dogné J.-M., Douxfils J., Blairon L. Validation of a chemiluminescent assay for specific SARS-CoV-2 antibody. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:1357–1364. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plebani M., Padoan A., Negrini D., Carpinteri B., Sciacovelli L. Diagnostic performances and thresholds: the key to harmonization in serological SARS-CoV-2 assays? Clin Chim Acta. 2020;509:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gui M., Song W., Zhou H., Xu J., Chen S., Xiang Y. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res. 2017;27:119–129. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song W., Gui M., Wang X., Xiang Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007236. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ter Meulen J., van den Brink E.N., Poon L.L., Marissen W.E., Leung C.S., Cox F. Human monoclonal antibody combination against SARS coronavirus: synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshabrawy H.A., Coughlin M.M., Baker S.C., Prabhakar B.S. Human monoclonal antibodies against highly conserved HR1 and HR2 domains of the SARS-CoV spike protein are more broadly neutralizing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han M.S., Seong M.W., Kim N., Shin S., Cho S.I., Park H. Viral RNA load in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic children with COVID-19, Seoul. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2497–2499. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fafi-Kremer S., Bruel T., Madec Y., Grant R., Tondeur L., Grzelak L. Serologic responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospital staff with mild disease in eastern France. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102915. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunyavanich S., Do A., Vicencio A. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA. 2020;323:2427–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Vignera S., Cannarella R., Condorelli R.A., Torre F., Aversa A., Calogero A.E. Sex-specific SARS-CoV-2 mortality: among hormone-modulated ACE2 expression, risk of venous thromboembolism and hypovitaminosis D. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2948. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun Y., Do A., Grishina G., Grishin A., Fang G., Rose S. Integrative study of the upper and lower airway microbiome and transcriptome in asthma. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e133707. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zachariah P., Johnson C.L., Halabi K.C., Ahn D., Sen A.I., Fischer A. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children's hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:e202430. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widders A., Broom A., Broom J. SARS-CoV-2: the viral shedding vs infectivity dilemma. Infect Dis Health. 2020;25:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang F., Quan Y., Xin Z.T., Wrammert J., Ma M.J., Lv H. Lack of peripheral memory B cell responses in recovered patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a six-year follow-up study. J Immunol. 2011;186:7264–7268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.