Abstract

Faecal-oral transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is yet to be validated, but it is a critical issue and additional research is needed to elucidate the risks of the novel coronavirus in sanitation systems. This is the first study that investigates the potential health risks of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage to wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) workers. A quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) is applied for three COVID-19 scenarios (moderate, aggressive and extreme) to study the effects of different stages of the pandemic in terms of percentage of infected population on the probability of infection to WWTP workers. A dose-response model for SARS-CoV-1 (as a surrogate pathogen) is assumed in the QMRA for SARS-CoV-2 using an exponential model with k = 4.1 × 102. Literature data are incorporated to inform assumptions for calculating the viral load, develop the model, and derive a tolerable infection risk. Results reveal that estimates of viral RNA in sewage at the entrance of WWTPs ranged from 4.14 × 101 to 5.23 × 103 GC·mL−1 (viable virus concentration from 0.04 to 5.23 PFU·mL−1, respectively). In addition, estimated risks for the aggressive and extreme scenarios (2.6 × 10−3 and 1.3 × 10−2, respectively) were likely to be above the derived tolerable infection risk for SARS-CoV-2 of 5.5 × 10−4 pppy, thus reinforcing the concern of sewage systems as a possible transmission pathway of SARS-CoV-2. These findings are helpful as an early health warning tool and in prioritizing upcoming risk management strategies, such as Emergency Response Plans (ERPs) for water and sanitation operators during the COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Keywords: Quantitative microbial risk assessment, Novel coronavirus, Wastewater treatment plants, Sewage, Sanitation, Emergency response plans

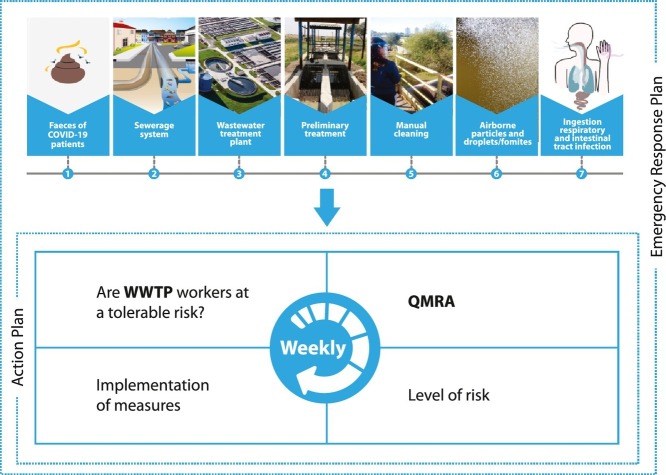

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The primary mechanism of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission is via respiratory droplets that people cough, sneeze or exhale (ECDPC, 2020; Kumar et al., 2020; Domingo et al., 2020). The virus can survive on different surfaces from several hours up to a few days (Joonaki et al., 2020), and although its persistence in waters is possible (Gwenzi, 2020), the stability of its infectivity is not fully understood. Human viruses do not replicate in the environment and the transport of SARS-CoV-2 via the water cycle potentializes its occurrence and persistence in human wastewater catchments, and enhances the possibility of coming in contact with people, most likely via aerosols and airborne particles (Haas, 2020; McLellan et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2020; La Rosa et al., 2020). An increasing number of articles on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in faeces of COVID-19 patients, by reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain (RT-qPCR), have been published and were recently reviewed by Kitajima et al. (2020), Foladori et al. (2020) and Gwenzi (2020). Although most literature on the virus detection in stool samples has identified only the viral genetic material (RNA), which does not necessarily mean viability, a few articles have indicated that the virus may remain viable, infectious and/or able to replicate in stool under certain conditions (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a; Xiao et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020b). The lack of studies and analyses of material with high concentrations of live virus (such as when performing virus propagation, virus isolation or neutralization assays), are likely due to the need for highly skilled staff and procedures equivalent to Biosafety Level 3 (containment laboratory with inward directional airflow) (CDC, 2020a; WHO, 2020).

In light of the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 to remain viable in conditions that would facilitate infection due to transmission via faecal-oral, it is necessary to further investigate under which conditions SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted through this route, as recently suggested by several authors (Yeo et al., 2020; Heller et al., 2020; Kitajima et al., 2020; Gwenzi, 2020; Foladori et al., 2020; Eslami and Jalili, 2020; Qu et al., 2020). The possibility of faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has many implications, especially in regions with poor sanitation infrastructure, considering the possible entering of SARS-CoV-2 into the sewage and wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). After the first SARS global outbreak of 2003, very little information was available on the presence of SARS-CoV in sewage, with the exception to the study by Wang et al. (2005), which reported that SARS-CoV could be excreted through the stool/urine of infected patients into the sewage system and remain infectious for 2 days at 20 °C, but for 14 days at 4 °C, thus demonstrating the sewage system as possible route of transmission. More, the persistence of two surrogate coronaviruses (transmissible gastroenteritis and mouse hepatitis) has already been reported by Casanova et al. (2009) – the two viruses remained infectious in pasteurized settled sewage for days to weeks, with great influence of temperature.

In the current COVID-19 pandemic, Medema et al. (2020) published the first report of detection of SARS-CoV-2 in WWTPs, by analyzing (using RT-PCR) sewage samples from seven different cities and from an airport in the Netherlands, during a period before and after the first COVID case reported in that country. The authors showed that no SARS-CoV-2 was detected in samples collected three weeks before the first COVID-19 case; meanwhile, the first virus fragment was detected in sewage at five sites, one week after the first COVID-19 case. More recently, F.Q. Wu et al. (2020) and Y. Wu et al. (2020) quantified viral titer of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage from a major urban treatment facility in Massachusetts (USA) and suggested approximately 100 viral particles per mL of sewage. In Queensland (Australia), SARS-CoV-2 RNA tested positive (RT-qPCR) in two out of nine sewage samples, and quantitative estimation were 3–4 orders of magnitude lower than in Wu's investigation (Ahmed et al., 2020). A reasonable assumption for this discrepancy is the much higher number of COVID-19 infected people in the former region and/or different faeces dilution rates along the sewer networks. Corroborating, Foladori et al. (2020) reported that concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage entering a WWTP may vary from 2 copies.100 mL−1 to 3 × 103 copies·mL−1.

These findings and other recent review papers (Collivignarelli et al., 2020; Gwenzi, 2020) show that, despite the lack of knowledge on the persistence of viable SARS-CoV-2 in sewage, estimates of its viral load and infectivity are under careful scrutiny by health authorities, sanitation operators, and the scientific community in response to the urgent warrant for research in this area. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for anticipated risk assessment and sanitation interventions in preventing this possible route of transmission and consequences for public health, considering a future confirmation and validation of the virus infectivity hypothesis in such environment (Heller et al., 2020). This is particularly important in less developed countries, where the occupational exposure for workers in WWTPs may warrant additional concern since the protocols of personal and collective protective equipment (PPE and CPE) use is not as stringent as it is in the developed countries.

Quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) is a useful tool that has been used for almost 40 years to estimate human health risks associated with exposures to pathogens in different environmental matrices (Haas et al., 2014). QMRA has been applied to assess health risks associated with bioaerosols (Carducci et al., 2018), drinking water (Petterson and Ashbolt, 2016), reclaimed water (Zaneti et al., 2012a, Zaneti et al., 2012b, Zaneti et al., 2013), recreational waters (Girardi et al., 2019; Gularte et al., 2019), irrigation water (Ezzat, 2020), and sewage (Kozak et al., 2020). Recent publications have encouraged the application of QMRA based on previous studies of relevant respiratory viruses, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, to assess the likelihood of adverse effects of SARS-CoV-2 associated with sewage exposure (Haas, 2020; Kitajima et al., 2020). Zhang et al. (2020b) conducted a QMRA of SARS-CoV-2 in a South China Seafood Market where health risks associated with aerosol transmission were evaluated. The estimated median risk of infection after 1 h of exposure in the market was 2.23 × 10−5. Another QMRA considered bioaerosol exposure to adenoviruses at a WWTP (Carducci et al., 2018). The authors estimated higher average risks associated with exposure to sewage influent and biological oxidation tanks (15.64% and 12.73%, respectively, for an exposure of 3 min). A limitation of conducting a QMRA of SARS-CoV-2 is the lack of dose-response information for this particular coronavirus, thus requiring data related to infectivity of similar viruses be assumed (Kitajima et al., 2020). Nevertheless, research studies - such as this present QMRA - are important for informing appropriate decisions during this pandemic. According to Kitajima et al. (2020), QMRA can be used to identify surface disinfection benchmarks for SARS-CoV-2, as well as the best technologies and disinfectants for achieving these targets. Such information will lead to effective health risk mitigation by reducing exposure. Further, according to Pecson et al. (2020), QMRA studies can identify unique characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 that may identify concerns regarding existing regulations and approaches to public health protection.

The focus of this work is to estimate these health risks by incorporating data from the literature, assuming different COVID-19 pandemic exposure scenarios, and by applying a QMRA at WWTPs. The objective of the risk assessment model was to estimate the dose of SARS-CoV-2 to which workers of WWTPs are exposed while performing their work activities.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Rationale

QMRA consists of four basic steps: (i) hazard identification; (ii) exposure assessment; (iii) effect assessment (dose-response relationship); and (iv) risk characterization. In occupational settings, these stages should take into account the worker's activity and identify the transmission chain, routes of exposure, and matrices involved (Carducci et al., 2016).

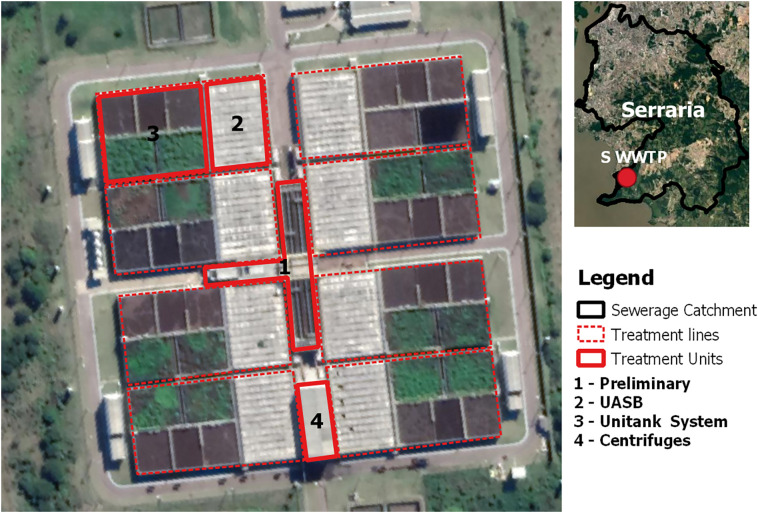

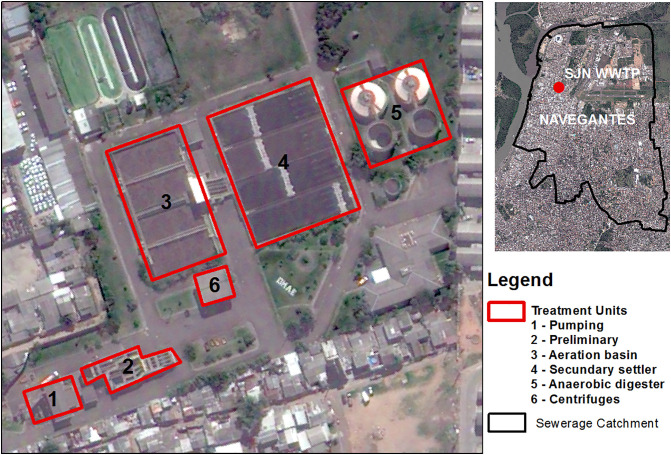

2.2. Site description

We performed the QMRA with information from two WWTPs from Porto Alegre (South Brazil) - São João Navegantes (SJN-WWTP) and Serraria (S-WWTP). The sewage treatment process at the S-WWTPs starts with manual (coarse) and automatic (fine) screening, followed by the grit removal. Then, the biological treatment includes an anaerobic stage by the UASB reactor and an aerobic stage through the Unitank® System. The sludge generated in the Unitank® system returns to the UASB reactor and is dehydrated through centrifuges. The treatment process at the SJN-WWTP includes the same preliminary and final stages, but the biological treatment stage is performed by activated sludge and secondary settling instead of the UASB and Unitank® equipment. The effluent of both WWTPs is then disposed in the Guaíba Lake. Schematic illustrations of the WWTPs are shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 .

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the S-WWTP.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the SJN-WWTP.

The WWTP workers perform routine activities such as manual cleaning of coarse screens, sewage sampling, chemical analysis, plant inspection, and sludge dehydration supervision. Treatment units are not covered or equipped with collective protective equipment (CPP) such as splash barriers, but it is mandatory for WWTP workers to wear goggles and gloves as personal protective equipment (PPE).

2.3. Hazard identification and exposure assessment

SARS-CoV-2 was considered and chosen for this risk assessment for its primary route to sewage from faeces (Heller et al., 2020), especially in cities that are affected by COVID-19, and potential human ingestion infecting both the intestinal and respiratory tracts. Although SARS-CoV-2 is a new virus and there are needs to be a better understanding of the occurrence of intact viral particles in sewage, the present QMRA takes a conservative approach to be protective of human health and assumes infectious (viable) SARS-CoV-2 in sewage for estimating the risk of infection, by using literature data and an adjustment factor (AF) described below. The use of conservative or worst-case estimates are advisable in QMRA when assumptions are used, such as in the present work, for a safer approach (WHO, 2016). The concentration of viable SARS-CoV-2 in sewage (VC) was calculated using Eq. (1). This method assumes a typical stool weight (SW) of 200 g·d−1 (F.Q. Wu et al., 2020; Y. Wu et al., 2020), then multiplies this assumption by the virus concentration in stool of COVID-19 patients (VS) by the AF and by the fraction of the population (FP) served by the WWTP with COVID-19 and having RNA viral in stool during the illness (48% - Cheung et al., 2020). The product is then divided by the flow rate of the WWTP (WF). There are, to the best of our knowledge, seven published studies on the quantification of SARS-CoV-2 load and viral RNA cycle threshold (Ct) values in the faeces of patients testing positive for COVID-19 until August 2020 (Cheung et al., 2020; Lescure et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wölfel et al., 2020; F.Q. Wu et al., 2020; Y. Wu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020c). The results are reported using GC per g of stool or GC per mL of stool and thus, to change units from #/mL to #/g, we used the density of wet human faeces of 1.075 g·mL−1 (Penn et al., 2018), which resulted in viral loads ranging from 5.4 × 103 to 6.6 × 107 GC·g−1. Then, to calculate VS (in PFU·mL−1), we assumed an average between the minimum and maximum value of 3.3 × 107 GC·g−1. The value used for AF was 10−3, assuming that 103 GC corresponds to one (1) plaque forming unit - PFU (Aslan et al., 2011; Mcbride et al., 2013; Carducci et al., 2016). This AF aims to simulate the environmental conditions of the virus in the sewage with those observed in clinical studies that determined the dose-response curves. It is known, for instance, that the dilution effect, the presence of surfactants and disinfectants in the sewage, and other factors regarding virus transformation along the sewer network, may reduce viral infectivity of the SARS-CoV-2 of the sewage at the entrance of WWTPs (Foladori et al., 2020; Chan et al., 2020).

| (1) |

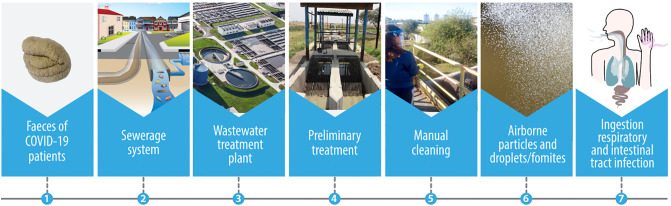

The exposure scenario (Fig. 3 ) was based on the proposed framework for faecal-oral hypothesis raised by Heller et al. (2020) and considered the event of accidental ingestion of sewage by WWTPs workers while performing routine activities. The hazardous exposures were identified by a systematic on-site survey of SJN-WWTP and S-WWTP and their treatment processes and operations. Through interviews with WWTP workers and monitoring of their activities, we identified that during manual cleaning of coarse screening, when a fork is used to remove wastes, exposure of workers to ingestion of droplets is a major hazardous event, especially in windy weather conditions, when there is intense contact of sewage droplets and airborne particles with their faces, particularly if they are not wearing a face shield and mask. Screening is the first sewage treatment stage and no reduction in viral particles and/or viral viability of sewage entering the WWTP is expected at this treatment point. The volume ingested considered data reported by Westrell et al. (2004) of 1 mL for worker exposed to the pre-aeration process. The frequency of exposure was considered to be a single event, since the focus of this study is to assess the risks during COVID-19 outbreaks, rather than estimating annual risks.

Fig. 3.

Faecal-oral exposure route of accidental ingestion of sewage by WWTP workers.

A range of three different scenarios were approached, classified according to the total number of COVID-19 infected people, from lowest to highest, as follows: i. moderate, using local data (Porto Alegre, Brazil); ii. aggressive, using data from Madrid (Spain); and iii. extreme, using data from New York City (USA). The evaluation of these three scenarios was divided in 6 types of exposure, three for each WWTP, carried out to study the effect of different stages of the pandemic in terms of percentage of infected population. For estimating total infected population, we used data of COVID-19 infected and recovered people and deaths from April/2020, and accounted for the under-reported cases according to Russell et al. (2020) for New York City and Madrid, and according to UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020a, UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020b for Porto Alegre. The specific values used and sources are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

QMRA calculations.

| Type of exposure | COVID-19 infected population in the WWTP contribution area | COVID-19 infected population having RNA viral in stoolf in the WWTP contribution area | SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral load in sewage, GC·mL−1 | Viable SARS-CoV-2 concentration in sewage, PFU·mL−1 | Dose (d), PFU | Risk of infection (P) | Tolerable infection risk pppy for SARS-CoV-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - SARS-CoV-2/SJN-WWTPa/Extremec | 36,977 | 17,749 | 4.44 × 103 | 4.44 | 4.44 | 1.1E-02 | 5.5E-04 |

| 2 - SARS-CoV-2/S-WWTPb/Extremec | 187,522 | 90,011 | 5.23 × 103 | 5.23 | 5.23 | 1.3E-02 | |

| 3 - SARS-CoV-2/SJN-WWTPa/Aggressived | 7615 | 3655 | 9.14 × 102 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 2.2E-03 | |

| 4 - SARS-CoV-2/S-WWTPb/Aggressived | 38,620 | 18,538 | 1.08 × 103 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 2.6E-03 | |

| 5 - SARS-CoV-2/SJN-WWTPa/Moderatee | 345 | 165 | 4.14 × 101 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.0E-04 | |

| 6 - SARS-CoV-2/S-WWTPb/Moderatee | 1748 | 839 | 4.87 × 101 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.2E-04 |

Sewage flow rate of 306 L·s−1, corresponding to 11.22% of the total population in Porto Alegre (Brazil).

Sewage flow rate of 1318 L·s−1, corresponding to 56.90% of the total population in Porto Alegre (Brazil).

Based on the total estimated population in New York City (United States), in April 2020 of 8,399,000 (United States Census, 2020) and its total COVID-19 active cases of 223,863 (obtained from the difference between the total positive cases of COVID-19 minus the total recovered and deaths (URL 1)). Additionally, not reported COVID-19 cases (88%) were accounted based on Russell et al. (2020), resulting in 22% of the population, in the extreme scenario, infected with COVID-19.

Based on the total estimated population in Madrid (Spain), in April 2020, of 6,642,000 (Eurostat, 2020) and its total COVID-19 active cases of 19,749 (obtained from the difference between the total positive cases of COVID-19 minus the total recovered and deaths (URL 2)). Additionally, not reported COVID-19 cases (93.5%) were accounted based on Russell et al. (2020), resulting in 4.6% of the population in the extreme scenario infected with COVID-19.

Based the total estimated population in Porto Alegre, in April 2020, of 1,483,771 (IBGE, 2020) and its total COVID-19 active cases of 3072, obtained from UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020a, UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020b, considering the under-reported COVID-19 case numbers of 93.2% (UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020a, UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020b), resulting in 0.2% of the total population, in the moderate scenario, infected with COVID-19.

Based on a 48% relation of COVID-19 infected patients having RNA viral in stool during the illness (Cheung et al., 2020).

2.4. Dose-response assessment and risk characterization

As with previously conducted QMRAs of other pathogens, often dose-response information (e.g., infectious dose) is lacking. Because there is no existing dose-response model for SARS-CoV-2, a dose-response model for SARS-CoV-1, as a surrogate pathogen, was assumed due to similarities in virus structure and epidemiological characteristics, such as their ability to infect different host species, their stability in aerosols (van Doremalen et al., 2020), and the assumptions made by Haas (2020). Watanabe et al. (2010) proposed the exponential model with k = 4.1 × 102 as a dose-response model for SARS-CoV-1 based on the available data sets for infection of transgenic mice susceptible to SARS-CoV-1 and infection of mice with murine hepatitis virus strain 1, which may be a clinically relevant model of SARS. This dose-response model was applied in the present work in the form of an exponential model (Eq. (2)) and dose was calculated as shown by Eq. (3). The risk of infection considered the estimated infectious SARS-CoV-2 in sewage (VC) calculated in Eq. (1). It is important to note, however, disadvantages in applying the SARS-CoV-1 model to address dose-response of the novel coronavirus. Although the dose-response parameters for SARS-CoV-1 were defined from pooled datasets that may represent different infection scenarios, much remains unknown about the pathogenesis and transmission mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 as evident from the number of asymptomatic cases and range of presenting symptoms associated with infection in hosts of different ages (Jin et al., 2020; Schröder, 2020). Although this introduces uncertainty in this QMRA, the greatest source of both uncertainty and variability in QMRAs come from the exposure assessment component (Haas et al., 1999).

| (2) |

| (3) |

where:

P = Probability of infection after a single exposure at the dose d;

d = Dose, as number of organisms ingested (PFU);

k = dose-response model (4.1 × 102);

I = Volume ingested (1 mL);

VC = Concentration of viable virus in sewage (PFU·mL−1).

2.5. Derivation of a tolerable infection risk benchmark

In order to provide a comparison of relative risks, a level of tolerable risk for SARS-CoV-2 was determined. WHO has used Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) as a common metric to evaluate public health priorities and to assess disease burden associated with environmental exposures, particularly for microbial hazards (WHO, 2017). DALYs attempt to combine in a single indicator the time lost because of disability or premature death from a disease compared with years of life free of disability in the absence of the disease. Thus, we used the tolerable burden of disease defined as an upper limit of 10−6 DALYs per person per year (pppy) set by WHO (2017) to define the related reference level of risk. In order to translate DALYs loss pppy into tolerable infection risk, we applied Eqs. (4), (5) developed by Mara (2008):

| (4) |

| (5) |

where:DALY loss per case of disease is equal to 2.01 × 10−3 for SARS-CoV-2, as estimated by Nurchis et al. (2020) in an observational study based on data from governmental sources obtained since the inception of the epidemic until 28 April 2020; and disease/infection ratio for SARS-CoV-2 is equal to 0.91, as determined in an epidemiological study (UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020a, UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, 2020b) that interviewed and tested 89,397 people for COVID-19 in South Brazil.

3. Results and discussion

The calculated SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral loads and viable virus concentration in the raw sewage of the SJN-WWTP and S-WWTP are provided in Table 1 . As expected, higher values were observed for the aggressive and extreme scenarios. In the considered SJN-WWTP, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration in sewage was 9.14 × 102 and 4.44 × 103 GC·mL−1 (VC of 0.91 and 4.44 PFU·mL−1, respectively), for aggressive and extreme scenarios, respectively. In the S-WWTP, these values increased to 1.08 × 103 and 5.23 × 103 GC·mL−1 (1.08 and 5.23 PFU·mL−1), respectively. This variation in values of about 18% among the WWTPs is attributed to the different flow rates of the WWTPs and the different portions of population that contribute to these plants. In the moderate (local) scenario, the total population infected by COVID-19 were at least 22 times lower than in the other conditions, and viral loads were of 4.14 × 101 and 4.87 × 101 GC·mL−1 (0.04 and 0.05 PFU·mL−1) in SJN-WWTP and S-WWTP, respectively.

Despite the uncertainties of the assumptions defined in the present work, we consider our approach appropriately protective for human health, as the viral loads obtained herein for all evaluated scenarios are in the same order of magnitude of the range reported by Foladori et al. (2020). This article reviewed the scarce studies that have quantified the SARS-CoV-2 RNA in sewage. Further, the authors report that the virus copies in sewage are largely diluted in comparison to those present in the faeces from COVID-19 patients, with a decrease in the concentration by 4–5 orders of magnitude or more. This also corroborates with our study, as we find that virus RNA concentration decreases by approximately 3, 4 and 5 orders of magnitude for extreme, aggressive and moderate scenarios, respectively, considering the viral load in faeces of 3.3 × 107 GC per g of stool (or 3.01 × 107 GC per mL of stool) assumed. Our results - including the lower decrease in the virus load observed in the extreme scenario - are explained by the population contribution to the WWTP, which depends on active cases of COVID-19 (since the whole population does not contribute to the viral load). The higher the infected population, the lower the dilution in sewage networks that serve this population.

The obtained values for the dose ranged from 0.04 to 5.23 PFU, considering the ingested volume of 1 mL. Determining exposure volumes for occupational risks in workplaces such as WWTPs is particularly challenging due to differences in skills and level of experience of workers, the wide range of activities and different levels of protection, as well as seasonal changes. Moreover, there is very little information about the ingestion route during such scenarios. It is generally recognized that accidental ingestion involves the processes of transfer of the substance from the environment into the mouth, and this must include movement of contaminated hands or objects into the mouth, or contact of contaminated hands or objects with the skin around the mouth (the peri-oral area) followed by migration of this contamination into the mouth (Christopher et al., 2006). Splashing into the mouth or onto the face are also relevant mechanisms, although probably much less important. Haas (2020) highlighted the relative importance of the so-called “fomites” in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, which consist of larger airborne particles that can deposit on surfaces, where the contained viruses persist for hours to days, and might have a pathway from hands to mouth, nose and eye. Ashbolt et al. (2005) supported that the volume ingested during operational irrigation activities (water intense activity) follow a triangular distribution of (0.1; 1; 2 – corresponding to min; mode; max, respectively), in mL. Based on that assumption, we have already carried out another risk-based study on accidental reclaimed wastewater ingestion by using the minimum value (0.1 mL) of this triangular distribution in order not to overestimate the risks (Zaneti et al., 2013; Zaneti et al., 2012a, Zaneti et al., 2012b). On the other hand, the ingestion volume adopted for the proposed exposure pathway in the present study (1 mL in a single event) arose from Westrell et al. (2004), for workers at a pre-aeration treatment stage of WWTP, corresponding to the same value of the mode of the aforementioned triangular distribution of Ashbolt et al. (2005), and thus, not over conservative. Therefore, this approach appears to satisfactorily support the viral loads and doses obtained herein.

For the extreme, aggressive and moderate scenarios, the estimated risks reached values up to 1.3 × 10−2, 2.6 × 10−3 and 1.2 × 10−4, respectively. According to Carducci et al. (2018), there are no occupational exposure limits (OELs) for microbial agents to date and thus, acceptable level of risks has not yet been defined. This can make the decision-making process for managing health risks of SARS-CoV-2 in workplaces such as WWTPs a little more complex. In the risk assessment and risk characterization of drinking water and reclaimed wastewater, risk targets are commonly determined in order to set microbial and toxicological limits and develop mitigation strategies (Dogan et al., 2020). In the present work, the derived tolerable infection risk pppy for SARS-CoV-2 was equal to 5.5 × 10−4 and thus, the estimated risks for the moderate and aggressive scenarios for both WWTPs were higher than this determined value (Table 1). The fact that the present study considered the risk of a single exposure and that it was higher than an acceptable annual risk in these two mentioned scenarios, reinforces the concern with the faecal-oral exposure route for SARS-CoV-2 – insofar as a greater number of WWTP worker exposure events are expected to take place over the course of a year. For this reason, although the estimated risks per exposure event for both WWTPs in the moderate scenario were lower than the tolerable infection risk pppy, it must not be neglected. Conversion of the calculated risk of infection related to a single event to the annual risk of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic is rather complex due to fluctuations in the evolution of the epidemiological curve (Bastos and Cajueiro, 2020; Kissler et al., 2020), and thus, leading to inaccuracies in estimating sewage viral loads and in calculating the respective risk of infection.

Since this is a novel coronavirus, there are aspects about its environmental persistence and transmission not yet known, including the impact of virus-laden wastewater aerosols in the ingestion transmission by WWTP workers due to a compromised workplace environment (Kitajima et al., 2020). Investigators have concluded that SARS-CoV-2 has similar survival capabilities as SARS-CoV-1 in aerosols that may contaminate facility surfaces and worker hands but more research is needed to better understand its survival in wastewater under different environmental conditions (Hart and Halden, 2020; Kitajima et al., 2020; Van Doremalen et al., 2020). A laboratory-based study showed the SARS-CoV-2 to be infective in aerosols for as long as 16 h (Fears et al., 2020). When considering occurrence in wastewater, Gundy et al. (2009) observed a relatively short survival time for other coronaviruses in primary and secondary wastewater with a 3-log reduction after 2–3 days. Although SARS-CoV-2 is similarly structured as other coronaviruses and may have similar environmental susceptibility, the possibility of exposure risk among WWTP workers should not be dismissed. Since there have been studies demonstrating exposure among sewage workers to rotavirus, norovirus and adenovirus via virus-laden aerosols (Carducci et al., 2018; Pasalari et al., 2019), the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 as an occupational health hazard should be addressed. Kitajima et al. (2020) reviewed epidemiological studies evaluating the possible health effects among WWTP workers associated with occupational exposures with gastrointestinal and respiratory infections as possible health outcomes.

The present study demonstrated that COVID-19 outbreaks may pose increasing health risks at such workplaces and thus, specific risk management strategies need to be developed. It is highly recommended that WWTP workers that perform manual cleaning of screening use face shields and face masks. At the same time, considering that in most of the emerging countries treatment tanks are not covered in WWTPs, as well as there is no barriers to avoid splashes and sprays as in the developed countries (KDHEKS, 2020; CDC, 2020b; Nghiem et al., 2020), it is suggested reduction in circulation (frequency and duration) of workers in such areas. Meanwhile, there are research needs to evaluate experimentally bioaerosol and airborne particle risks for WWTP workers and nearby communities. To date, there is no such work available, but research evaluating SARS-CoV-2 concentration at specific points of the sewer catchment, including the WWTP, as a wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) strategy seeking to help public health authorities planning epidemic containment is underway (Daughton, 2020; F.Q. Wu et al., 2020; Y. Wu et al., 2020). Such a practice would warn public health officials of community COVID-19 infections earlier than traditional health screenings or virus testing following the onset of symptoms severe enough to warrant medical attention (Hart and Halden, 2020). This early detection could inform an infection risk reduction strategy to mitigate an outbreak, while also minimize effects such as unnecessarily long stay-at-home policies that stress populations and economies when the risks are low (Daughton, 2020).

Our understanding of the potential role of sewage in SARS-CoV-2 transmission is limited by knowledge gaps in SARS-CoV-2 viability in the wastewater environment. Nevertheless, the present findings are important to assist stakeholders and WWTP managers anticipate and reduce an imminent risk by developing risk management strategies for health protection of workers. An important tool in this context are the Emergency Response Plans (ERP), which aim to standardize response protocols and inform mitigation actions by sanitation operators when facing emergencies (Rubin, 2004; Warren et al., 2009). These can be used to minimize the risks and associated impacts arising from events, whether natural or caused by human error. Most water and sanitation operators lack information to support an ERP and would welcome guidance with the planning process. The QMRA developed in this work can be implemented as an early health warning tool in an ERP using the tolerable risk of infection derived by us as a reference to categorize risk level. From this level of risk, mitigation measures can be established that may become more restrictive in terms of workers' exposure as risk levels become higher. Dunn et al. (2014) reported that risk assessment and management have been applied for decades in many industries (including the energy utility sector) and are critical to such operations; however, in the water and sanitation sectors, these practices are relatively new. Emergency preparedness is essential to the resilience of water and wastewater utilities, as they must still provide their vital services to society despite disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sowby, 2020).

In the two WWTPs evaluated in the present study (S-WWTP and SJN-WWTP), an ERP was proposed with a QMRA informing an action plan, in which security protocols have been strengthened by requiring the use of face shields and masks and, in some cases, the use of covers or other barriers on treatment tanks to avoid exposure to sewage splashes.

4. Conclusions

-

•

The incorporation of literature data of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2, the framework of different exposure scenarios, and a dose-response model of a surrogate coronavirus, allowed the application of a QMRA of SARS-CoV-2 for workers in WWTPs that can be implemented as an early health warning tool, during the COVID-19 and future pandemics.

-

•

The QMRA, performed with the aid of a three-tiered approach, revealed that the aggressive and extreme scenarios resulted in an estimated risk of infection for workers greater than the derived tolerable infection risk for SARS-CoV-2, demonstrating the urgent need for proactive emergency preparedness.

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic impacts the activities in WWTPs at different risk levels depending on the fraction of the population infected by the SARS-CoV-2 that contributes to these plants. The development of ERPs - based on the present QMRA - are highly advisable to set conservative risk management strategies, especially to reduce WWTP workers' exposure as risk levels become higher.

-

•

Looking toward the future, studies combining SARS-CoV-2 molecular detection in sewage and viral isolation in cell culture to validate infectivity, as well as epidemiological studies, are needed to validate the present assumptions. Another urgent research need is the risk assessment for communities bordering WWTPs or for communities that simply do not have sewage collection. This is a common situation in underdeveloped countries, which may be subject to routes of exposure to the virus by direct ingestion and inhalation of bioaerosols.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors of this research paper have directly participated in the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing of the article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank DMAE (Municipal Water and Sewage Department from Porto Alegre/RS, Brazil), which allowed the use of operational data and information from WWTPs.

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajimae M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID- 19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbolt N.J., Petterson S.R., Stenstron T.A., Schonning C., Westrell T., Ottosson J. Chalmers University of Technology; Göteborg, Sweden: 2005. Microbial Risk Assessment (MRA) Tool. Report 2005:7. Urban Water. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A., Xagoraraki I., Simmons F.J., Rose J.B., Dorevitch S. Occurrence of adenovirus and other enteric viruses in limited-contact freshwater recreational areas and bathing waters. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;111:1250–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos S.B., Cajueiro D.O. Modeling and forecasting the early evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil. 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.14288 Available on line in. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carducci A., Donzelli G., Cioni L., Verani M. Quantitative microbial risk assessment in occupational settings applied to the airborne human adenovirus infection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:733–743. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carducci A., Donzelli G., Cioni L., Federigi I., Lombardi R., Verani M. Quantitative microbial risk assessment for workers exposed to bioaerosol in wastewater treatment plants aimed at the choice and setup of safety measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:1490–1502. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009;43(7):1893–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim laboratory biosafety guidelines for handling and processing specimens associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html Available in.

- CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Guidance for Reducing Health Risks to Workers Handling Human Waste or Sewage.https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/global/sanitation/workers_handlingwaste.html Available online at. [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.H., Sridhar S., Zhang R.R., Chu H., Fung A.Y.F., Chan G., Chan J.F.W., To K.K.W., Hung I.F.N., Cheng V.C.C., Yuen K.Y. Factors affecting stability and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.009. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Ka Shing, Hung Ivan F.N., Chan Pierre P.Y., Lung K.C., Tso Eugene, Liu Raymond, Ng Y.Y., et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from the Hong Kong cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Y., Semple S., Hughson G.W., Cherrie J.W. Inadvertent ingestion exposure in the workplace. 2006. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr551.pdf Available online in. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Collivignarelli M.C., Miinoa M.C., Abbàc A., Pedrazzani R., Bertanza G. SARS-CoV-2 in sewer systems and connected facilities. Process Saf. Environ. 2020;143:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2020.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C.G. Wastewater surveillance for population -wide Covid-19: the present and future. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan O.B., Meneses Y.E., Flores R.A., Wang B. Risk-based assessment and criteria specification of the microbial safety of wastewater reuse in food processing: managing Listeria monocytogenes contamination in pasteurized fluid milk. Water Res. 2020;171 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo J.L., Marquès M., Rovira J. Influence of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on COVID-19 pandemic. A review. Environ. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109861. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G., Harris L., Cook C., Prystajecky N. A comparative analysis of current microbial water quality risk assessment and management practices in British Columbia and Ontario, Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;468–469:544–552. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDPC - European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Q & A on COVID-19. 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/ Available online in.

- Eslami H., Jalili M. The role of environmental factors to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) AMB Express. 2020;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

- Ezzat S.M. Applying quantitative microbial risk assessment model in developing appropriate standards for irrigation water. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020;16(3):353–361. doi: 10.1002/ieam.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears A.C., Klimstra W.B., Duprex P., Hartman A., Weaver S.C., Plante K.C., Mirchandani D., Plante J.A., Aguilar P.V., Fernández D., Nalca A., Totura A., Dyer D., Kearney B., Lackemeyer M., Bohannon J.K., Johnson R., Garry R.F., Reed D.S., Roy C.J. Comparative dynamic aerosol efficiencies of three emergent coronaviruses and the unusual persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosol suspensions. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.13.20063784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foladori P., Cutrupi F., Segata N., Manara S., Pinto F., Malpepi F., Bruni L., La Rosa G. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: what do we know? A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140444. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi V., Mena K.D., Albino S.M., Demoliner M., Gularte J.S., de Souza F.G., Rigotto C., Quevedo D.M., Schneider V.E., Paesi S.O., Tarwater P.M., Spilki F.R. Microbial risk assessment in recreational freshwaters from southern Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;651:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gularte J.S., Girardi V., Demoliner M., Souza F.G., Filippi M., Eisen A.K.A., Mena K.D., Quevedo D.M., Rigotto C., Barros M.P., Spilki F.R. Human mastadenovirus in water, sediment, sea surface microlayer, and bivalve mollusk from southern Brazilian beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;142:335–349. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environ. Virol. 2009;1:10–14. doi: 10.1007/s12560-008-9001-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gwenzi W. Leaving no stone unturned in light of the COVID-19 faecal-oral hypothesis? A water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) perspective targeting low-income countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas C.N. Coronavirus and environmental engineering science. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2020;37:233–234. doi: 10.1089/ees.2020.0096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas C.N., Rose J.B., Gerba C.P. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1999. Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment; pp. 330–331. [Google Scholar]

- Haas C.N., Rose J.B., Gerba C.P. 2nd ed. John Wiley; New York: 2014. Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Hart O.E., Halden R.U. Computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 surveillance by wastewater-based epidemiology locally and globally: feasibility, economy, opportunities and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller L., Mota C.R., Greco D.B. COVID-19 faecal-oral transmission: are we asking the right questions? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística 2020. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rs/porto-alegre/panorama

- Jin Y., Yang H., Ji W., Wu W., Chen S., Zhang W., Duan G. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of COVID-19. Viruses. 2020;12(4):372. doi: 10.3390/v12040372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joonaki E., Hassanpouryouzband A., Heldt C.L., Areo O. Surface chemistry can unlock drivers of surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 in a variety of environmental conditions. Chem. 2020;6:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KDHEKS Guidance for Kansas drinking water and wastewater operators regarding coronavirus (COVID-19) risks. 2020. https://www.coronavirus.kdheks.gov/DocumentCenter/View/379/Guidance-for-Kansas-Drinking-Water-and-Wastewater-Operators-Regarding-COVID-19-Risks-PDF---3-12-20 Available online in.

- Kissler S.M., Tedijanto C., Goldstein E., Grad Y.H., Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Ahmed W., Bibby K., Carducci A., Gerba C.P., Hamilton K.A., Haramoto E., Rose J.B. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: state of the knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak S., Petterson S., McAlister T., Jennison I., Bagraith S., Roiko A. Utility of QMRA to compare health risks associated with alternative urban sewer overflow management strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;262 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Taki K., Gahlot R., Sharma A., Dhangar K. A chronicle of SARS-CoV-2: part-I - epidemiology, diagnosis, prognosis, transmission and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;734:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Ferraro G.B., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescure F., Bouadma L., Nguyen D., Parisey M., Wicky P.H., Behillil S., Gaymard A., Bouscambert-Duchamp M., Donati F., Le Hingrat Q., Enouf V., Houhou-Fidouh N., Valette M., Mailles A., Lucet J.C., Mentre F., Duval X., Descamps D., Malvy D., Timsit J.F., Lina B., van der Werf S., Yazdanpanah Y. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Qian H., Hang J., Chen X., Hong L., Liang P., Li P., Xiao S., Wei J., Liu L., Kang M. Evidence for probable aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a poorly ventilated restaurant. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mara D. A numerical guide to volume 2 of the guidelines and practical advice on how to transpose them into National Standards. Third edition of the guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and Greywater in agriculture and aquaculture. Guidance note for programme managers and engineers. 2008. https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/wastewater/Volume2_v2.pdf?ua=1 Available online in:

- McBride G.B., Stott R., Miller W., Bambic D., Wuertz S. Discharge-based QMRA for estimation of public health risks from exposure to stormwater-borne pathogens in recreational waters in the United States. Water Res. 2013;47:5282–5297. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan N., Pernitsky D., Umble A. Coronavirus and the water cycle — here is what treatment professionals need to know. Wateronline. 2020. www.wateronline.com/doc/coronavirus-and-the-water-cycle-here-is-what-treatment-professionals-need-to-know-0001 Available online in.

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 in sewage. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.20045880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghiem L.D., Morgan B., Donner E., Short M.D. The COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for the waste and wastewater services sector. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020;1:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurchis M.C., Pascucci D., Sapienza M., Villani L., D’Ambrosio F., Castrini F., Specchia M.L., Laurenti P., Damiani G. Impact of the burden of COVID-19 in Italy: results of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and productivity loss. Int. J. Env. Re. Pub. He. 2020;17:4233. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalari H., Ataei-Pirkooh A., Aminikhah M., Jafari A.J., Farzadkia M. Assessment of airborne enteric viruses emitted from wastewater treatment plant: atmospheric dispersion model, quantitative microbial risk assessment, disease burden. Environ. Pollut. 2019;253:464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecson B., Gerrity D., Bibby K., Drewes J.E., Gerba C., Gersberg R., Gonzalez R., Haas C.N., Hamilton K.A., Nelson K.L., Olivieri A., Rock C., Rosen J., Sobseyo M. Editorial perspectives: will SARS-CoV-2 reset public health requirements in the water industry? Integrating lessons of the past and emerging research. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1039/D0EW90031A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penn R., Ward B.J., Strande L., Maurer M. Review of synthetic human faeces and faecal sludge for sanitation and wastewater research. Water Res. 2018;132:222–240. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petterson S.R., Ashbolt N.J. QMRA and water safety management: review of application in drinking water systems. J. Water Health. 2016;14(4):571–589. doi: 10.2166/wh.2016.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G., Li X., Hu L., Jiang G. An imperative need for research on the role of environmental factors in transmission of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(7):3730–3732. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K. Water Environment Research Foundation; 2004. Emergency Response Plan Guidance for Wastewater Systems. (Available online at: STOCK NO. 03CTS4S) [Google Scholar]

- Russell T.W., Hellewell J., Sbbott S., Golding N., Gibbs H., Jarvis C.I., van Zandvoort K., Flasche S., Eggo R.M., Edmunds W.J., Kucharski A.J. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; 2020. Using a Delay-adjusted Case Fatality Ratio to Estimate Under-reporting.https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/global_cfr_estimates.html Available on line in. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder I. COVID-19: a risk assessment perspective. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2020;27(3):160–169. doi: 10.1021/acs.chas.0c00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowby R.B. Emergency preparedness after COVID-19: a review of policy statements in the U.S. water sector. Util. Policy. 2020;64:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2020.101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas Epicovid, epidemiologia da COVID-19 no Rio Grande do Sul. 2020. https://wp.ufpel.edu.br/covid19/files/2020/04/Covid-19vers%C3%A3o.pdf

- UFPEL – Universidade Federal de Pelotas EPICOVID19-BR divulga novos resultados sobre o coronavírus no Brasil. 2020. http://www.epidemio-ufpel.org.br/site/content/sala_imprensa/noticia_detalhe.php?noticia=3128 Available online in.

- United States Census 2020. https://www.census.gov/glossary/#term_Populationestimates

- URL 1 Live science. New York: latest updates on coronavirus. https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-new-york.html

- URL 2 COVID-19 tracker. https://www.bing.com/covid/local/madrid_spain

- Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris T.H., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. Corresp. 2020;382 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.W., Li J., Guo T., Zhen B., Kong Q., Yi B., Li Z., Song N., Jin M., Xiao W., Zhu X., Gu C., Yin J., Wei W., Yao W., Liu C., Li J., Ou G., Wang M., Fang T., Wang G., Qiu Y., Wu H., Chao F., Li J. Concentration and detection of SARS coronavirus in sewage from Xiao Tang Shan hospital and the 309th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Water Sci. Technol. 2005;52:213–221. doi: 10.2166/wst.2005.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L., Davis S., Cyr C.T. Wiley Handbook of Science and Technology for Homeland Security, Hoboken. 2009. Emergency response planning for water and/or wastewater systems. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Bartrand T.A., Weir M.H., Omura T., Haas C.N. Development of a dose-response model for SARS coronavirus. Risk Anal. 2010;30:1129–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrell T., Schönning C., Stenström T.A., Ashbolt N.J. QMRA (quantitative microbial risk assessment) and HACCP (hazard analysis and critical control points) for management of pathogens in wastewater and sewage sludge treatment and reuse. Water Sci. Technol. 2004;50:23–30. doi: 10.2166/wst.2004.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization Laboratory biosafety guidance related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/laboratory-biosafety-guidance-related-to-coronavirus-disease-2019-(covid-19) Available online in.

- WHO – World Health Organization Quantitative microbial risk assessment: application for water safety management. World Health Organization. 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246195 Available online in.

- WHO – World Health Organization Guidelines for drinking-water quality-fourth edition incorporating the first addendum. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254637/1/9789241549950-eng.pdf?ua=1 Available online in. [PubMed]

- Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., Niemeyer D., Kelly T.C.J., Vollmar P., Rothe C., Hoelscher M., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Ehmann R., Zwirglmaier K., Drosten C., Wendtner C. Virological assessment of hospitalized cases of coronavirus disease 2019. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.Q., Xiao A., Zhang J.B., Gu X.Q., Lee W.L., Kauffman K., Hanage W.P., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Moniz K., Erickson T.B., Chai P.R., Thompson J., Alm E.J. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. MedRxiv preprint. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20051540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., Yin H., Xiao Q., Tang Y., Qu X., Kuang L., Fang X., Mishra N., Lu J., Shan H., Jiang G., Huang X. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in Faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. 2020;5(5):434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Sun J., Xu Y., Li F., Huang X., Li H., Zhao J., Huang J., Zhao J. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 in feces of patient with severe COVID-19. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(8) doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y., Guo Q., Sun X., Zhao D., Shen J., Zhang H., Liu H., Xia H., Tang J., Zhang K., Gong S. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo C., Kaushal S., Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet: Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaneti R.N., Etchepare R., Rubio J. Case study: car wash water reuse – a Brazilian experience. United States Environmental Protection Agency 2012 Guidelines for Water Reuse EPA. 2012. https://www3.epa.gov/region1/npdes/merrimackstation/pdfs/ar/AR-1530.pdf Available on line in.

- Zaneti R.N., Etchepare R., Rubio J. More environmentally friendly vehicle washes: water reclamation. J. Clean. Prod. 2012;37:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaneti R.N., Etchepare R., Rubio J. Car wash wastewater treatment and water reuse – a case study. Water Sci. Technol. 2013;67:82–88. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chen C., Zhu S., Shu C., Wang C., Song J., Song Y., Zhen W., Feng Z., Wu G., Xu J., Xu W. Isolation of 2019-nCoV from a stool specimen of a laboratory confirmed case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(8):123–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ji Z., Yue Y., Liu H., Wang J. Infection risk assessment of COVID-19 through aerosol transmission: a case study of South China Seafood Market. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02895. Accepted Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Gong Y., Meng F., Bi Y., Yang P., Wang F. 2020. Virus Shedding Patterns in Nasopharyngeal and Fecal Specimens of COVID-19 Patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]