Keywords: arterial stiffness, cardiovascular, IPA, microbiota

Abstract

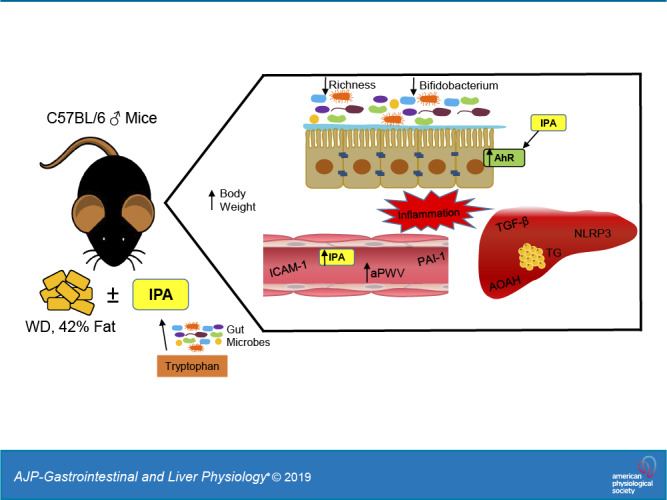

Emerging evidence suggests that intestinal microbes regulate host physiology and cardiometabolic health, although the mechanism(s) by which they do so is unclear. Indoles are a group of compounds produced from bacterial metabolism of the amino acid tryptophan. In light of recent data suggesting broad physiological effects of indoles on host physiology, we examined whether indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) would protect mice from the cardiometabolic consequences of a Western diet. Male C57BL/6J mice were fed either a standard diet (SD) or Western diet (WD) for 5 mo and received normal autoclaved drinking water or water supplemented with IPA (0.1 mg/mL; SD + IPA and WD + IPA). WD feeding led to increased liver triglycerides and makers of inflammation, with no effect of IPA. At 5 mo, arterial stiffness was significantly higher in WD and WD + IPA compared with SD (WD: 485.7 ± 6.7 and WD + IPA: 492.8 ± 8.6 vs. SD: 436.9 ± 7.0 cm/s, P < 0.05) but not SD + IPA (SD + IPA: 468.1 ± 6.6 vs. WD groups, P > 0.05). Supplementation with IPA in the SD + IPA group significantly increased glucose AUC compared with SD mice (SD + IPA: 1,763.3 ± 92.0 vs. SD: 1,397.6 ± 64.0, P < 0.05), and no significant differences were observed among either the WD or WD + IPA groups (WD: 1,623.5 ± 77.3 and WD + IPA: 1,658.4 ± 88.4, P > 0.05). Gut microbiota changes were driven by WD feeding, whereas IPA supplementation drove differences in SD-fed mice. In conclusion, supplementation with IPA did not improve cardiometabolic outcomes in WD-fed mice and may have worsened some parameters in SD-fed mice, suggesting that IPA is not a critical signal mediating WD-induced cardiometabolic dysfunction downstream of the gut microbiota.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The gut microbiota has been shown to mediate host health. Emerging data implicate gut microbial metabolites of tryptophan metabolism as potential important mediators. We examined the effects of indole-3-propionic acid in Western diet-fed mice and found no beneficial cardiometabolic effects. Our data do not support the supposition that indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) mediates beneficial metabolic effects downstream of the gut microbiota and may be potentially deleterious in higher circulating levels.

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian gastrointestinal tract contains trillions of microorganisms collectively referred to as the gut microbiota (39). Although these microorganisms play a critical role in maintaining host physiology and health, deleterious changes to the gut microbiota have been linked to disease processes (15). For example, compositional changes to the gut microbiota following high-fat or Western diet (high fat and sugar) have been implicated in the development of several cardiometabolic consequences, including glucose intolerance, arterial stiffness, hepatic steatosis, and systemic inflammation (9, 13, 19).

The mechanisms by which the gut microbiota influences physiological and disease processes are not completely understood, although recent studies suggest that cross-talk between the gut microbiota and metabolic tissues can be mediated by the autonomic nervous system (24) or by microbially derived signals that enter the general circulation. These latter signals include bacterial components (e.g., lipopolysaccharide) and products of microbial metabolism, such as short-chain fatty acids derived from microbial fermentation of carbohydrates (29) and trimethylamine (TMA), produced by bacterial metabolism of carnitine and choline (28, 44).

Recently, microbial metabolites of the essential aromatic amino acid tryptophan have also been suggested as mediators of host-microbiota cross-talk. Whereas the majority of dietary tryptophan is absorbed in the small intestine and metabolized by the liver (22), it has been estimated that ∼4–6% of dietary tryptophan is metabolized by gut microbes (20, 23, 48). Microbial metabolism of tryptophan produces the organic compound indole and various indole derivatives, including indoleacrylic acid (IA), indole-3-aldehyde (I3A), and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), all of which can elicit various physiological effects via binding primarily to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (2, 25, 49). Recent data indicate that these tryptophan metabolites regulate intestinal homeostasis, and impaired indole-AhR activity may compromise cardiometabolic function (3, 31, 38, 47). IPA in particular has garnered attention as a potential protective factor against intestinal and metabolic dysfunction. For example, circulating IPA is reduced in patients with colitis and may serve as a marker of disease remission (3). In a large cohort of individuals in Finland (45), IPA was inversely related to type 2 diabetes incidence. Experimentally, IPA has been shown to mitigate weight gain and improve glucose homeostasis in Sprague-Dawley rats, as well as reduce dysbiosis and metabolic endotoxemia following a high-fat diet (1, 30, 50). Additionally, IPA elicits protection in cell culture and isolated tissue models via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and chemical chaperone activity (27, 36).

Despite accumulating data suggesting beneficial effects of IPA, little is known regarding its ability to modulate the cardiometabolic consequences of a Western diet. Recent evidence from our laboratory indicates that the gut microbiota is a key regulatory factor in obesity-related cardiometabolic function (9, 10), although the mechanisms underlying this effect are unclear. Thus, in the present study we sought to determine whether IPA is a potential mediator of microbe-host crosstalk by examining if IPA supplementation protects experimental mice from the broad cardiometabolic consequences of a Western diet. We also assessed circulating and colonic indole and tryptophan concentrations in cohorts of genetically obese mice and lean and overweight/obese humans.

METHODS

Experimental design.

Male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and acclimated for 2 wk with ad libitum access to a standard diet (SD; TD.08485; Harlan Laboratories) consisting of 13% fat, 67.9% carbohydrate, and 19.1% protein calories. Mice were cohoused two per cage in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Once acclimated, 4- to 5-mo-old mice were randomly assigned to a standard diet (SD; n = 24) or Western diet (WD; n = 24) (TD.88137; Harlan Laboratories) consisting of 42.0% fat (61.8% saturated, 27.3% monounsaturated, 4.7% polyunsaturated), 42.7% carbohydrate (80% sucrose), and 15.2% protein calories with ad libitum access. Mice were then randomly assigned to receive normal drinking water or drinking water supplemented with indole-3-propionic acid (IPA; no. 57400; Sigma-Aldrich) at 0.1 mg/mL (3), resulting in the following groups: 1) SD receiving normal drinking water, 2) WD receiving normal drinking water, 3) SD + IPA, and 4) WD + IPA (n = 12 mice/group). Mice remained on assigned diets and treatments for a 5-mo duration. The dose of IPA administration (0.1 mg/ml) was chosen based on previous data demonstrating beneficial effects of IPA-supplemented drinking water on murine intestinal homeostasis (3). Supplemented IPA drinking water was changed twice per week, and the stability of IPA in water was confirmed with HPLC before the study was started. Body weight and food intake were recorded weekly. Fluid intake was tracked and recorded twice per week.

Arterial stiffness.

Aortic pulse-wave velocity (aPWV) was measured at 0, 2, and 5 mo using a Doppler Flow Velocity System (Indus Instruments, Webster, TX) via methods described previously by our laboratory (9, 10, 33). aPWV (in cm/s) was calculated as aPWV = (distance between the 2 probes)/(Δtimeabdominal − Δtimetransverse).

Glucose tolerance test.

In month 5 on diet/treatment and 2 wk before termination, mice were food fasted for 6 h, and blood glucose was determined from tail-vein blood using AlphaTRAK 2 glucose meters (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). After baseline glucose readings (time point “0”), mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 2 g/kg glucose, and blood glucose levels were measured at 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min postinjection.

Intestinal permeability.

At month 5 on diet/treatment and 1 wk before termination, mice were water-fasted for 12 h during the dark cycle before oral gavage with a 125 mg/ml FITC-dextran (4,000 mol wt, no. 46944; Sigma-Aldrich) solution diluted in sterile 1× PBS for a goal dose of 600 mg/kg body wt of FITC-dextran. Food was removed immediately after oral gavage, and blood was collected 4 h later via tail bleed for quantification of serum FITC-dextran concentration. Serum samples were diluted 1:2 in 1× PBS, and fluorescence was measured on a spectrophotometer at 485/20 (excitation) and 528/20 (emission). Serum concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve of known FITC-dextran concentrations prepared in control serum from untreated mice.

Animal termination and tissue collection.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by exsanguination via cardiac puncture. Blood was collected in a 0.5 M EDTA-coated (no. 15575020; Invitrogen) syringe. Based on the volume of blood collected, 2% EDTA was added, and plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 2,000 rcf for 10 min at 4°C and immediately flash-frozen. The liver was then removed and flash-frozen. The gastrointestinal tract was excised and colon length recorded. Cecum and adipose tissue (subcutaneous, epididymal, and mesenteric depots) were isolated and weighed. Sections of colon were obtained 0.25 cm away from the cecum.

Circulating analytes.

Plasma levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10) were measured via ELISA (no. M1000B; R & D Systems), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, standards, kit control, and samples were plated in duplicate, and sample values were calculated from a standard curve (R2 = 0.98). Plasma levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) were determined using a mouse premixed multi-analyte kit (no. LXSAMSM; R & D Systems), following the manufacturer’s protocol and analyzed using the Luminex 100/200 instrument. Briefly, standards and samples were plated in duplicate, and samples were calculated from the standard curves (R2 = 1.00).

Liver triglycerides and tissue gene expression.

For triglyceride quantification, liver was first digested with ethanolic potassium hydroxide. Liver triglycerides were quantified using a colorimetric assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (no. 10010303; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). A separate portion of liver and the proximal colon were used for total RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For real-time PCR, reverse transcription was performed using 0.5 µg of DNase-treated RNA, SuperScript II RNase H, and random hexamers. PCR reactions were performed in 96-well plates using transcribed cDNA and iQ-SYBR Green master mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Primer sequences are provided in Table 1. PCR efficiency was between 90 and 105% for all primer and probe sets and linear over five orders of magnitude. The specificity of products generated for each set of primers was examined for each amplicon using a melting curve and gel electrophoresis. Reactions were run in duplicate, and data were calculated as the change in cycle threshold (ΔCT) for the target gene relative to the ΔCT for β2-microglobulin (reference gene) similar to the methods used by Battson et al. (7). Fold change differences were calculated by .

Table 1.

Sequence of quantitative PCR primers for liver tissue

| Target Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| B2M | S: CGGTCGCTTCAGTCGTCAG AS: ATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTCTCC |

| AOAH | S: TGAACCAAGAAATAGCAGGCG AS: GGGTGTGTGGTACTGGTATCT |

| IL-1β | S: TCTTTGAAGTTGACGGACCC AS: TGAGTGATACTGCCTGCCTG |

| NLRP3 | S: AGCCTTCCAGGATCCTCTTC AS: CTTGGGCAGTTTCTTTC |

| TGFβ | S: TGGACACACAGTACAGCAAGG AS: GTAGTAGACGATGGGCAGTGG |

| IL-33 | S: AGCTCTCCACCGGGGCTCAC AS: CCTCGCGTGCTGCTGAACT |

| AhR | S: GCCTGTGACTCAGCACCTAA AS: TTGATTTGCGTGTGCTTCGG |

| Occludin | S: AGCCTTCTGCTTCATCGCTT AS: ACCATGATGCCCAGGATAGC |

| IL-10Rα | S: AGTGGCTTTGGCAGTGGTAA AS: GATCCCACTGTCCGTGTTGT |

AhR; aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AOAH, acyloxyacyl hydrolase; AS, antisense; B2M, β2-microglobulin; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-33, interleukin 33; IL-10R, interleukin 10 receptor-αNLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3; S, sense; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β1.

Plasma and colon indole quantification, instrumentation, and sample preparation.

Human plasma samples were collected in previous clinical research studies (34, 43) from lean, overweight, and obese human subjects. Briefly, 33 human subjects (BMI range = 17.3, age range = 45, sex = 20 female/14 male) were included for indole quantification. Plasma and colon indole concentrations were determined from archived samples following previously described methods (3).

For the current analysis, plasma protein was precipitated by combining plasma and 50% methanol with a labeled internal standard (indole-3-propionic-2,2-d2 acid, no. D-7686; CDN Isotopes) at a 0.05 µg/mL final concentration. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min at 19°C. Standards were prepared with blank plasma, and protein was precipitated with internal standard in the same manner as described above. Sample plasma IPA concentrations were determined from the standard curve generated by TargetLynx software. The standard curve had an R2 of 0.977. Samples and standards were run in duplicate. Tandem UPLC-MS-MS instrumentation included a Waters Acquity ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) instrument equipped with an Acquity UPLC BEH (ethylene bridged hybrid) Amide column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm column model no. 186004801) and a Waters XEVO electrospray ionization (Z-Spray ESI) triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (XEVO-TQD, QCA1088). Samples were separated on the Amide column at 3-µl aliquots at a 0.4 mL/min flow rate at 40°C, with a linear gradient of 20% to 100% Eluent A [100% acetonitrile with 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid] for 4 min, whereas Eluent B was 100% water with 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. The retention time of indole-3-propionic acid was 0.86 min. The analyte was detected and quantified using the peak area in comparison to the peak area of the standards.

Microbiota characterization.

Fecal DNA was extracted using the FastDNA Kit (no. 116540400; MP Biomedicals), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplification of the V4 16S rRNA region via qPCR was completed following the Earth Microbiome Project protocol utilizing the 515F-806R primer set (17) containing a unique 12-bp error-correcting barcode included on the forward primer. Cycling conditions using the Bio-Rad CFX96 thermal cycler were as follows: 94°C for 3 min and then 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 50°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by 72°C for 10 min. Negative DNA extraction controls, no template PCR controls, and the Zymo mock community were included on the plates. Paired-end sequencing libraries of the V4 region were then constructed by purifying amplicons using AmPure beads and quantifying and pooling equimolar ratios of each sample. The pooled library was quantified and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq at the Next-Generation Sequencing Facility at Colorado State University.

Forward and reverse sequence reads were imported into QIIME2 version 2019.1 for analysis. Briefly, the sequence reads were demultiplexed, concatenated, and trimmed to 250 base pairs for the forward reads and 155 base pairs for the reverse reads. Reads were binned into ASVs using the DADA2 pipeline (14). Taxonomic assignments were made using GreenGenes version 13.8. Sequences were filtered to remove any undesired mitochondrial or chloroplast DNA from the data set. Resulting feature tables and taxonomy files were imported into MyPhyloDB version 1.2.0 (35).

α-Diversity was analyzed using phylogenetic and nonphylogenetic measures. α-Diversity was calculated using Faiths and Shannon metrics through the QIIME2 diversity plugin. β-Diversity was determined by Bray Curtis distance measurements and visualized by palmitoyl-CoA in MyPhyloDB. Differences in taxa among treatments were analyzed by univariate ANCOVA analysis, and the multivariate EdgeR was run using the DiffAbund function in MyPhyloDB. LEfSe was applied to examine which features contribute the most to differences among treatments. LEfSe analysis was performed at http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/, utilizing the default settings.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. For comparisons between more than two groups, statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA (SPSS for Windows, Release 25.0.0.1; SPSS, Chicago, IL). When a significant main effect was observed, a Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to determine specific pairwise differences. For comparisons between lean and obese mice or humans, an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bivariate relations between variables of interest were determined using a Pearson correlation coefficient (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA). Microbial community nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine statistical significance of α-diversity measures, and NMDS of Bray-Curtis distances was tested for significance using PERMANOVA with 1,000 iterations. ANCOVA with post hoc Tukey’s HSD adjusted for multiple comparisons was the univariate statistic used for identifying significantly different taxa abundances between treatment groups, and the multivariate negative binomial GLM with FDR < 0.1 was used to determine which taxa contribute significantly to differences between groups.

RESULTS

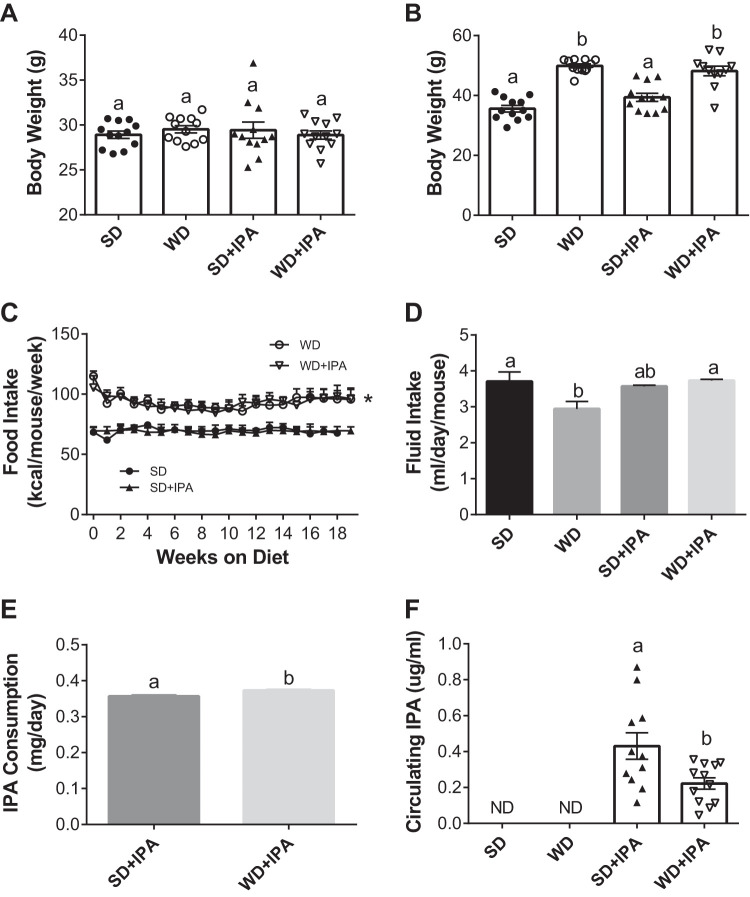

At baseline, before diet or treatment interventions, mice had similar body weights (Fig. 1A). Mice fed a WD gained significantly more weight than SD-fed mice during the 5-mo intervention, which was unaffected by IPA supplementation (Fig. 2B). Food intake was similar among SD-fed mice for the duration of the intervention but significantly greater in WD-fed mice, irrespective of IPA supplementation (Fig. 1C). Average fluid intake over 5 mo, measured twice per week, was lower in WD mice and similar among the other three groups (Fig. 1D). In line with similar average fluid intakes in both IPA-supplemented groups, SD + IPA and WD + IPA consumed similar levels of IPA (0.357 ± 0.003 and 0.373 ± 0.003 mg·day−1·mouse−1), although the small difference was statistically significant (Fig. 1E). We next sought to measure circulating levels of IPA given that ingestion of bioactive molecules may not reflect circulating levels. Plasma levels of IPA in the SD and WD groups did not exceed background levels in the plasma matrix used to generate the standard curve (Fig. 1F). However, plasma IPA was detected in both IPA supplemented groups, and a roughly twofold greater level was detected in SD + IPA compared with WD + IPA mice (Fig. 1F). Metabolic characteristics and tissue weights are shown in Table 2. Generally, fat mass differed by dietary group, whereby WD-fed mice exhibited greater fat mass relative to SD-fed mice. No difference was observed in colon lengths and cecum weight among groups.

Fig. 1.

Western diet (WD) feeding increases body weight, with no effect of indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) supplementation. Body weight of animals at baseline before diet and treatment interventions (A), body weight of animals fed a standard diet (SD) or WD with or without IPA at 5 mo (B), food intake over the 5-mo feeding and treatment period (C), average fluid intake over the course of the 5-mo feeding and treatment period (D), estimated average IPA consumption over the course of the study (E), and circulating IPA levels (F). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 11–12 mice/group. a,bP < 0.05, data with different superscript letters are significantly different. *P < 0.05 at all time points for WD-fed animals vs. SD-fed animals.

Fig. 2.

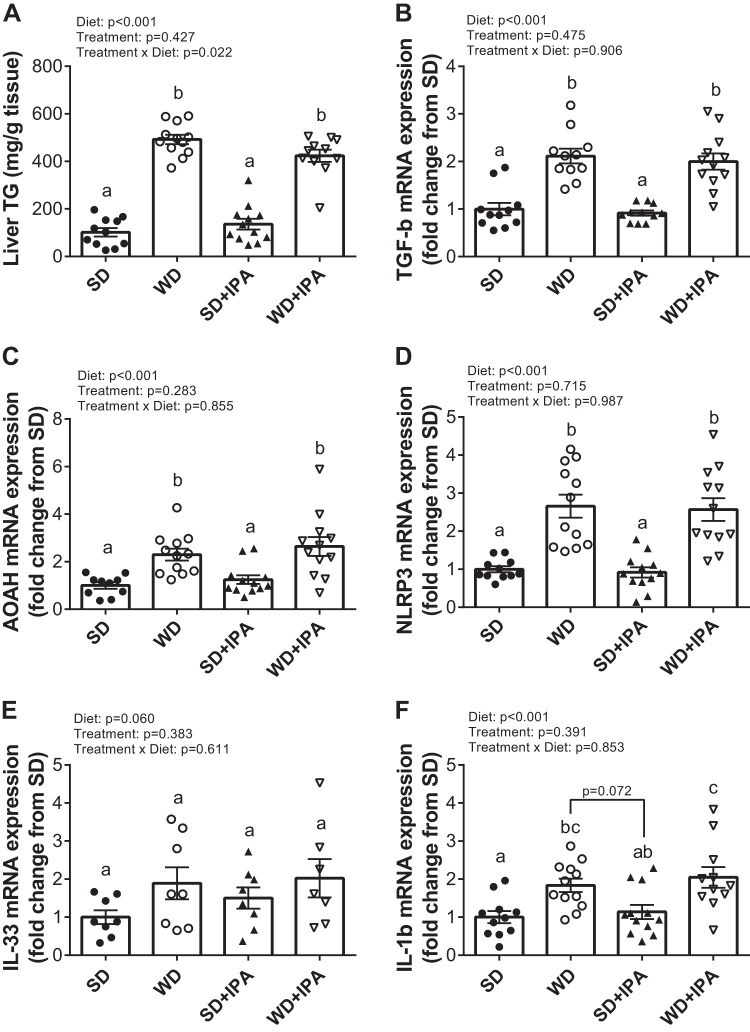

Western Diet (WD) feeding increases liver triglycerides and markers of inflammation. A: liver triglycerides expressed as mg/g of tissue and liver expression of the following genes: TGF-b (B), acyloxyacyl hydrolase (AOAH; C), NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3; D), IL-33 (E), and IL-1β (F). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 10–12 mice/group. a,b,cP < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different.

Table 2.

General and metabolic characteristics

| Variable | SD | WD | SD + IPA | WD_IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cecum, mg | 284 ± 24a | 233 ± 19a | 302 ± 14a (P = 0.057 vs. WD) | 237 ± 17a (P = 0.091 vs. SD + IPA) |

| Colon length, cm | 5.8 ± 0.2a | 5.7 ± 0.1a | 5.9 ± 0.1a | 5.7 ± 0.2a |

| Epididymal fat, mg | 1,525 ± 152a | 2,409 ± 245 b,c | 2,102 ± 154a,b | 2,857 ± 156c |

| Subcutaneous fat, mg | 597 ± 42a | 1,876 ± 119b | 758 ± 86a | 1,372 ± 141c |

| Mesenteric fat, mg | 623 ± 60a | 1,189 ± 114b | 650 ± 70a | 1,220 ± 109b |

| PVAT, mg | 35 ± 4a,c | 49 ± 4a,b | 27 ± 2c | 56 ± 6b |

Values are means ± SE. IPA, indole-3-propionic acid; PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue (n = 11–12 mice/group); SD, standard diet; WD, Western diet. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

P < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different.

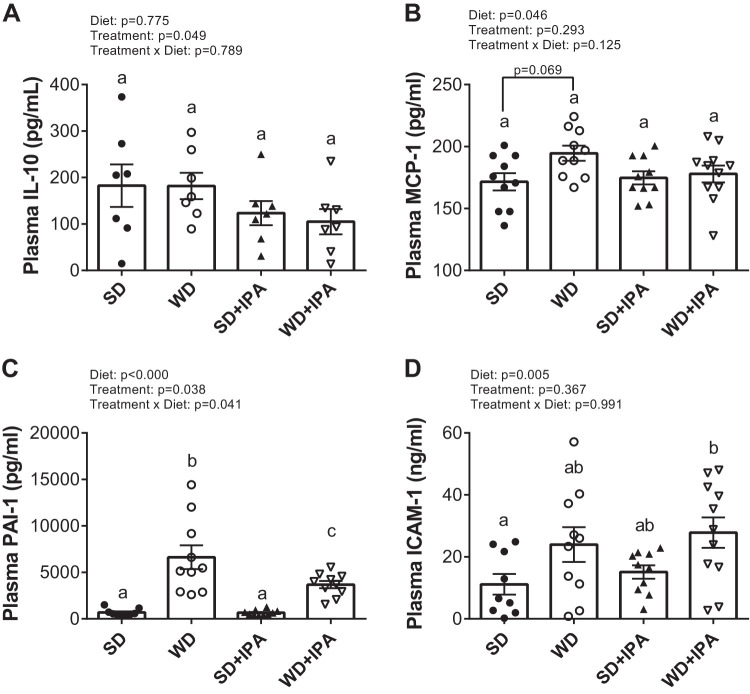

Measurement of liver triglycerides reveled significantly higher levels in WD-fed groups compared with SD-fed groups, with no effect of IPA (Fig. 2A). Similarly, hepatic expression of the inflammatory markers TGFβ, acyloxyacyl hydrolase (AOAH), and NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) were significantly increased compared with both SD-fed groups, with no effect of IPA supplementation (Fig. 2, B–D), and expression of both IL-33 and IL-1β tended to be higher in WD-fed mice relative to SD-fed mice (Fig. 2, E and F). Circulating levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were not significantly different among the four groups, although there was a significant effect of treatment, as both IPA groups displayed lower levels (Fig. 3A). A significant effect of diet was observed for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), all of which have been implicated to regulate vascular homeostasis (Fig. 3B–D).

Fig. 3.

Western Diet (WD) feeding increases circulating markers of inflammation. Plasma levels of IL-10 (A), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1; B), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1; C), and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; D). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 10–12 mice/group. a,b,cP < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different. IPA, indole-3-propionic acid; SD, standard diet.

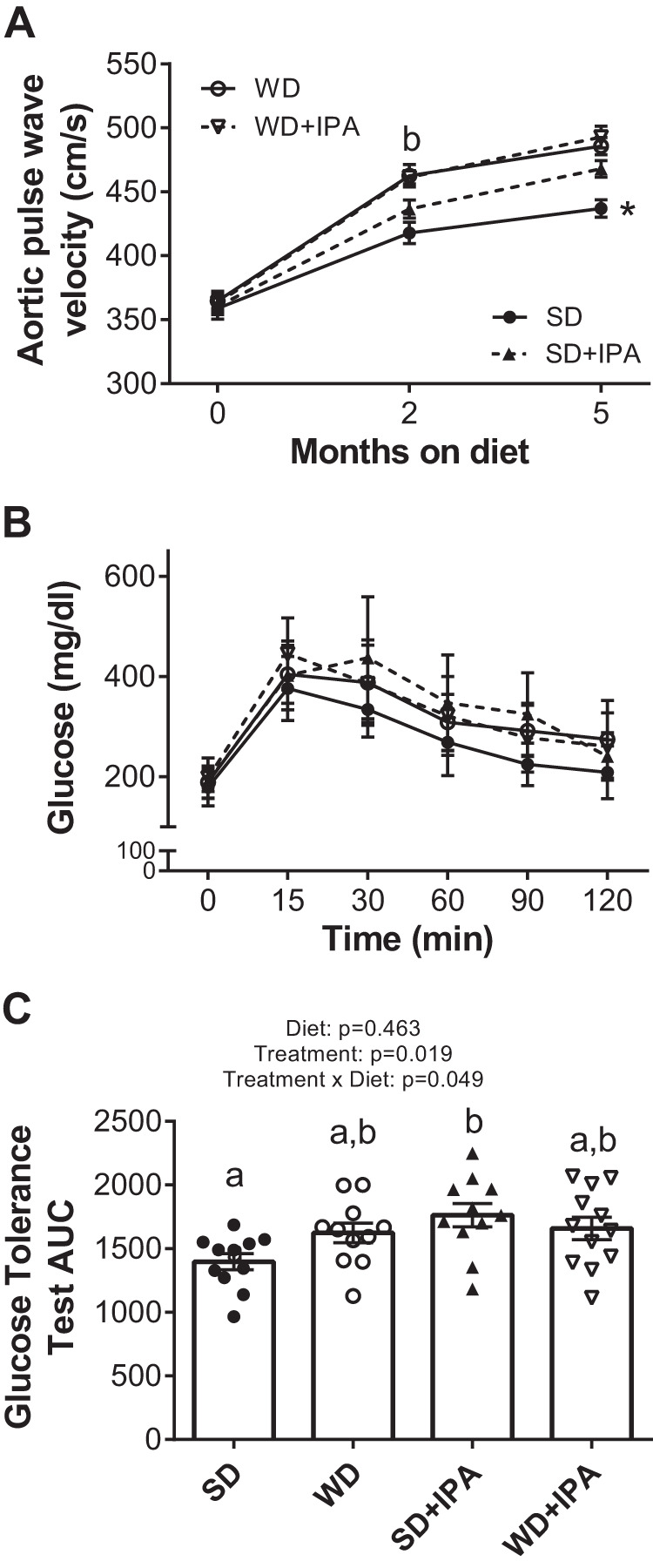

Cardiovascular risk was determined by measurement of arterial stiffness (via aPWV) given its strong predictive value for future cardiovascular events (37). aPWV was similar among all four groups at baseline (Fig. 4A). Both groups of WD-fed mice displayed a progressive increase in aPWV during the 5-mo intervention, with no effect of IPA supplementation. At both the 2-mo and 5-mo time points, WD and WD + IPA mice displayed a significantly higher aPWV compared with SD. Interestingly, at 2 mo of diet and treatment, SD + IPA mice began to separate from SD such that at 5 mo of treatment both groups of WD-fed mice and SD + IPA displayed a significantly higher aPWV compared with SD (Fig. 4A). Similar to aPWV, IPA supplementation significantly decreased glucose tolerance in SD-fed mice such that values were similar to both WD-fed groups (Fig. 4B). Specifically, are under the curve (AUC) in WD, WD + IPA, and SD + IPA was between 15 and 21% greater than SD, with only SD + IPA reaching statistical significance (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) does not affect Western diet (WD)-induced arterial stiffness but increases stiffness in standard diet (SD)-fed mice. A: arterial stiffness measured by Aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV) at baseline and 2 mo and 5 mo of feeding and treatment. B: glucose tolerance test at 5 mo. C: glucose tolerance test (GTT) area under the curve. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 11–12 mice/group. *P < 0.05 vs all other groups. a,bP < 0.05, data with different superscriptED letters are significantly different.

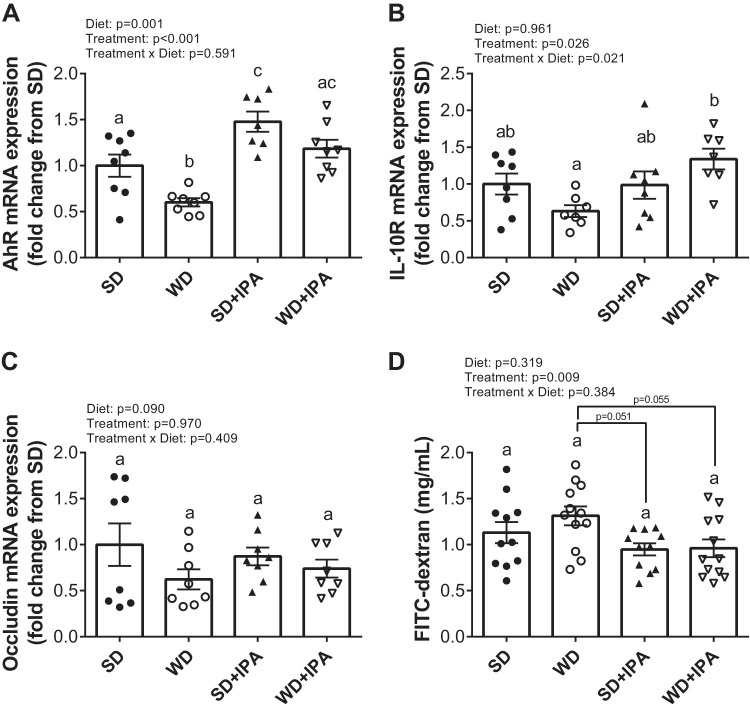

Within the colon, expression of the indole target, aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), was significantly lower in WD mice compared with all groups, and a significant treatment effect was observed, whereby both IPA groups displayed increased expression (Fig. 5A). We next measured the expression of the IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) and tight-junction protein occludin, given their importance in maintaining intestinal homeostasis (3, 21). Similar to AhR mRNA, IL-10R was reduced in WD compared with SD, and a significant treatment effect was observed such that IPA supplemented mice displayed greater expression (Fig. 5B). Similarly, occludin expression tended to be lower in WD mice, but no significant differences were observed among the four groups (Fig. 5C). We next assessed gut permeability utilizing FITC-dextran. Western diet feeding did not affect FITC levels, whereas there was a significant effect of IPA treatment, with plasma FITC levels lower in both IPA-supplemented groups (Fig. 5D). Thus, the data suggest that although IPA supplementation did not mitigate WD-induced dysfunction in the liver and vasculature, it may have offered some protection in the intestines.

Fig. 5.

Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) increases the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) receptor expression but does not alter gut barrier function. Colon expression of AhR (A), IL-10 receptor (B), and occludin (C) and intestinal permeability (D) assessed by FITC-dextran 4 h postgavage at the 5-mo feeding and treatment period (B). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 11–12 mice/group. a,b,cP < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different. SD, standard diet; WD, Western diet.

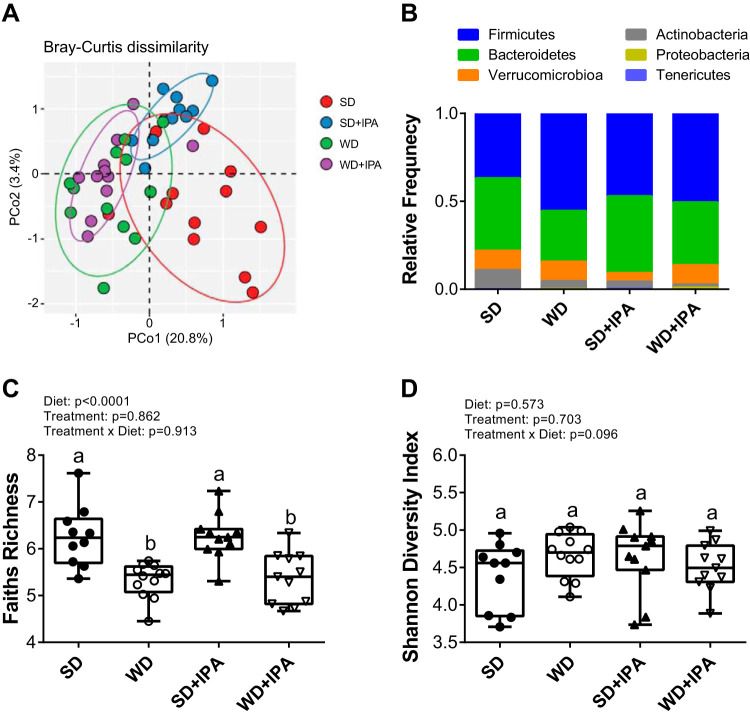

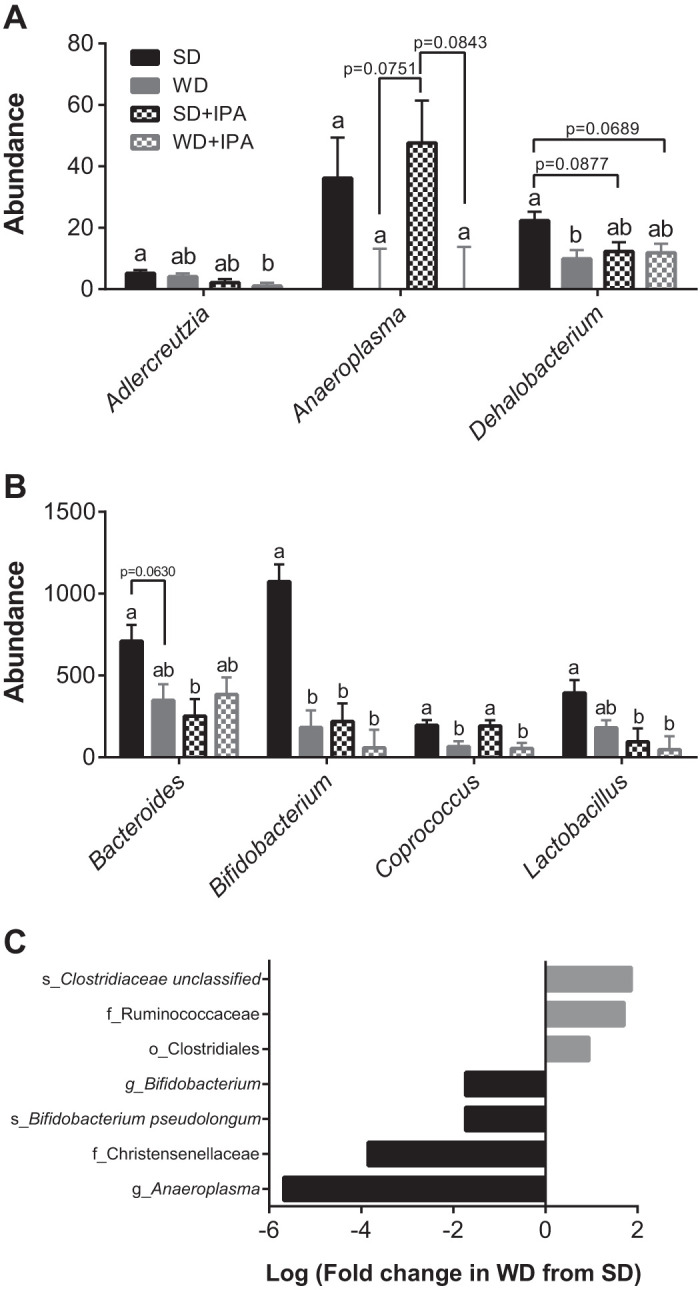

To determine whether IPA affected gut microbiota composition, we characterized the microbiota by 16s rRNA. Western diet feeding led to shifts in the gut microbiota that distinguished the two dietary groups. PCA analysis revealed a sample clustering by diet along PCo1 (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, whereas diet appeared to be the main driver among the WD and WD + IPA groups, the SD + IPA clustered separately from the SD group, suggesting that IPA supplementation drove differences among SD-fed mice. Several phylum-level taxa differed between groups, and notably, Firmicutes levels were lowest in the SD group accompanied by higher levels of actinobacteria (Fig. 6B). Richness was decreased in WD-fed mice irrespective of IPA supplementation (Fig. 6C), and diversity was not different among the four groups (Fig. 7D). Using negative binomial GLM, we found that the abundance of several bacterial taxa was altered based on diet and treatment (Fig. 7, A–C, and Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Material for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11421327.v2). In particular, Bifidobacterium was lower in both groups of WD-fed mice and SD + IPA relative to SD mice (Fig. 7C) and negatively correlated with indices of cardiometabolic dysfunction including aPWV, body weight, and liver inflammation (Supplemental Fig. S2). Similarly, Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Coprococcus also correlated with several cardiometabolic parameters (Supplemental Figs. S3–S5).

Fig. 6.

Western diet (WD) feeding drives changes in the gut microbiota. Palmitoyl-CoA (PCoA) plot showing Bray-Curtis distances of mouse fecal microbiota species level communities colored by diet and treatment (A), relative abundance of taxa at the phylum level (B), Faiths Richness of mouse fecal microbiota samples (C), and Shannon Diversity index of mouse fecal microbiota samples (D). Box represents 25th to 75th percentiles. Median values are represented by box plot internal line and ranges by whiskers; n = 10–12/group. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 10–12 mice/group. a,bP < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different. SD, standard diet.

Fig. 7.

Western diet (WD) feeding and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) differentially drive changes in the gut microbiota. Abundance of significantly different genus-level taxa (A), abundance of significantly different genus-level taxa (B), and differential abundance of taxa that were significantly different in WD mice compared with standard diet (SD) mice (C); n = 10–12 mice/group. a,bP < 0.05, data with different superscripted letters are significantly different.

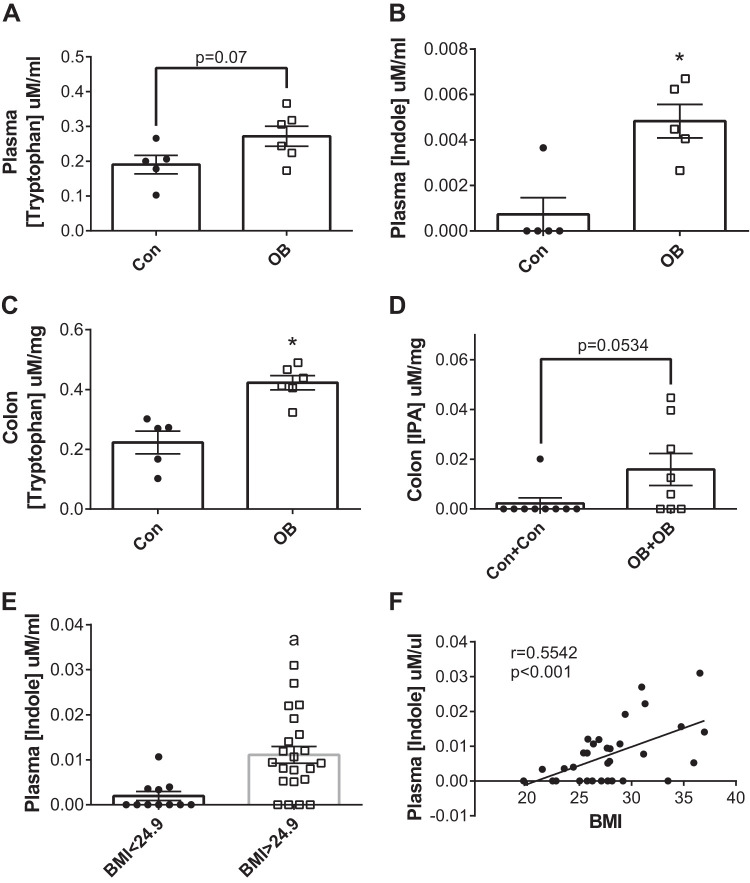

Overall, these data are at odds with recent observational and experimental data suggesting that IPA may provide metabolic benefit in models of obesity downstream of changes to the microbiota (12, 18, 31, 38) but are consistent with two studies suggesting that indoles may increase cardiometabolic risk (26, 40). To gain further insight into the relation between indoles and obesity, we examined tryptophan and its indole metabolites in recently published cohorts of lean and obese (ob/ob) mice and humans (10, 34, 43). We found that, compared with lean mice, obese mice displayed higher circulating levels of tryptophan and indole (Fig. 8, A and B) as well as higher colonic concentrations of tryptophan and IPA (Fig. 8, C and D). Similarly, in overweight and obese human subjects, plasma indole concentrations were significantly higher relative to lean human subjects (Fig. 8E), and plasma indole concentrations significantly and positively correlated with BMI (Fig. 8F).

Fig. 8.

Indoles are higher in obese mice and humans. Plasma tryptophan concentrations in lean (Con) and obese (OB) mice (A), plasma indole concentrations in lean (Con) and obese (OB) mice (B), colon tryptophan concentrations in lean (Con) and obese (OB) mice (C), and colon IPA concentrations in lean (Con) and obese (OB) mice (D), plasma indole concentrations in lean (BMI<24.9) and overweight/obese (BMI>24.9) human subjects (E), and correlation of plasma indole concentrations and BMI in human subjects (F). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–9 mice/group for mouse data, and n = 11–22 human subjects/group for human data; data in F were determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. *P < 0.05 vs. Con group.

DISCUSSION

Dietary tryptophan can be metabolized by three main pathways: one yielding serotonin, one producing kynurenine and its metabolites, and one producing indoles (2). Although some steps of the kynurenine pathway can be directed by microbial enzymes, the indole pathway is dependent solely upon microbial metabolism. In the current study, we surmised that tryptophan metabolites may be an important messenger mediating microbe-host cross-talk. Specifically, we hypothesized that IPA could mitigate WD-induced cardiometabolic impairments based on several observations. First, a substantial body of literature supports the notion that microbial metabolites may be important messengers that regulate numerous aspects of cardiometabolic function (11). Second, a Western diet is associated with reductions in Bifidobacterium (10, 16), which is capable of producing indoles from tryptophan (6). Third, accumulating evidence in humans, experimental animals, and cell culture models indicate that IPA protects from cardiometabolic dysfunction (3, 30, 50).

Contrary to our hypothesis, the primary finding of the current study is that supplementation with IPA did not protect mice from WD-induced cardiometabolic dysfunction. Specifically, in WD-fed mice, IPA supplementation did not affect body weight, liver triglycerides, aPWV, glucose tolerance, or markers of inflammation. Interestingly, IPA supplementation in SD-fed mice appeared to impair glucose tolerance and arterial stiffness relative to SD mice. Additionally, tryptophan metabolites were increased in genetically obese mice and humans compared with lean controls. Thus, in contrast to our hypothesis, our data suggest that IPA does not elicit protection from a WD and may impair cardiometabolic function SD-fed mice.

IPA failed to protect mice from an array of Western diet-induced cardiometabolic consequences, including arterial stiffness, hepatic steatosis, and glucose intolerance. These data are in disagreement with several previous studies. For example, in a cohort of healthy and diseased individuals, circulating IPA was negatively associated with ankle-brachial index, a marker of atherosclerotic risk (18). Likewise, circulating IPA was reduced in patients with colitis (3) and inversely related to type 2 diabetes incidence (45). Experimentally, IPA has been shown to attenuate weight gain and improve glucose homeostasis in Sprague-Dawley rats (1, 30, 50). Zhao et al. (50) reported that IPA supplementation protected rats from high-fat diet-induced dysbiosis, endotoxemia, and steatohepatitis. The reasons for these discrepant findings are unclear. Most previous studies administered IPA via gavage, diet, or injection, whereas in the present study IPA was supplemented in the drinking water; although Alexeev et al. (3), demonstrated that administration via drinking water produced beneficial intestinal effects in a model of colitis.

Despite the lack of protection and potential detriment of IPA supplementation in the liver and vasculature, animals supplemented with IPA tended to display improvements in the intestines, as evidenced by lower FITC-dextran levels and increased IL-10R expression. These data are consistent with previous studies showing that indoles increase tight-junction protein expression and decrease intestinal permeability (7, 20, 38). The differential effects of IPA in the intestines and periphery in the current study suggest that intestinal disruption is not required for the development of cardiometabolic dysfunction following a Western diet.

In addition to the lack of beneficial effects in mice fed a Western diet, IPA appeared to worsen arterial stiffness and glucose tolerance in mice fed a standard diet. Interestingly, circulating IPA concentrations were double in SD-fed animals compared with WD-fed animals despite similar intake and matched levels of dietary tryptophan. This variation in circulating IPA may have been due to difference in intestinal absorption between SD and WD (42) or alterations in xenobiotic metabolism caused by the WD (41). Nevertheless, it is possible that the higher circulating IPA levels in SD+IPA may have driven the metabolic dysfunction in these animals. Indeed, prolonged stimulation of AhR has been implicated to have detrimental outcomes (5). In support of these data, a tryptophan-rich diet or intracolonic infusion of indole increased circulating IPA and induced portal hypertension in rats (26). Furthermore, Pulakazhi Venu et al. (40) reported that IPA decreased vasodilation via activation of PXR and subsequent downregulation of eNOS in aortic tissue.

We have previously shown that gut dysbiosis from WD feeding drives vascular dysfunction and that levels of Bifidobacterium negatively correlate with WD-induced vascular dysfunction (9). Similarly, in the current study,16s rRNA analysis revealed that WD feeding decreased Bifidobacterium, and this reduction was related to aPWV, body weight, and liver inflammation. WD-fed animals also displayed low bacterial richness, which has been associated with increased adiposity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and an inflammatory phenotype in humans (32). PCA analysis demonstrated that Western diet feeding drove microbiota composition regardless of IPA supplementation, although in SD-fed animals, IPA caused unique compositional changes. In particular, genus-level ANCoVA showed reduced abundance of Bifidobacterium in SD + IPA. The reduction in Bifodobacterium specifically may be driving the negative cardiometabolic effects observed in this group.

Previous studies have shown that high-fat diet feeding depletes the gut microbiota of indole-3-acetate and tryptamine (31) and that humans with metabolic syndrome have impaired ability to metabolize tryptophan to indoles (38). Thus, we retrospectively examined levels of tryptophan and indoles from previously published cohorts of genetically obese (ob/ob) mice and lean and obese humans (10, 34, 43). We found that ob/ob mice had higher levels of circulating tryptophan and indole as well as higher colon concentrations of tryptophan and IPA. Additionally, in a cohort of lean, overweight, and obese humans, there was a significant positive correlation between plasma indole and BMI. These data are consistent with our findings in WD-fed animals, as well as a study by Wang et al. (46), which found that higher-fasting tryptophan was predictive of the development of diabetes, but are at odds with those by Natividad et al. (38), suggesting that humans with metabolic syndrome produce fewer AhR agonists.

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. First, although there were no significant effects of IPA supplementation on body weight or food intake, metabolic cages would have allowed us to more rigorously determine changes in activity. Second, administration of IPA via oral gavage would have allowed for more precise measurement of ingestion.

In conclusion, we found that the tryptophan-derived microbial metabolite IPA did not protect WD-fed mice from the cardiometabolic consequences of a Western diet and impaired function in standard diet-fed mice. Although IPA supplementation may have elicited modest beneficial effects in the intestines, these effects were outweighed by the broader metabolic outcomes. Thus, our results do not support the supposition that IPA mediates beneficial metabolic effects downstream of the gut microbiota.

GRANTS

This work utilized the RMACC Summit supercomputer, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (awards ACI-1532235 and ACI-1532236), the University of Colorado Boulder, and Colorado State University. The Summit supercomputer is a joint effort of the University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University (3).

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1 HL14411 (C. L. Gentile and T. L. Weir); American Heart Association grant 18TPA34170585 (C. L. Gentile and T. L. Weir), Colorado State University Agricultural Experimental Station grant COL00766 (C. L. Gentile) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Research Dietetic Practice Group Pilot Grant (D. M. Lee).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M.L., T.L.W., and C.L.G. conceived and designed research; D.M.L., K.E.E., S.R.J.T., S.D.W., K.N.T., M.L.B., Y.W., T.L.W., and C.L.G. performed experiments; D.M.L., K.E.E., S.D.W., T.L.W., and C.L.G. analyzed data; D.M.L., S.A.J., T.L.W., and C.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; D.M.L. prepared figures; D.M.L. drafted manuscript; D.M.L., S.A.J., T.L.W., and C.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; D.M.L., K.E.E., S.R.J.T., S.D.W., K.N.T., M.L.B., Y.W., S.A.J., T.L.W., and C.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the laboratory of Sean P. Colgan (University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus) and Cheryle Beuning and Claudia Boot (Central Instrument Facility at Colorado State University) for assistance with plasma and colon IPA quantification and analysis. Additionally, we thank Michael Sumpter and Eli Moskowitz for assistance with data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abildgaard A, Elfving B, Hokland M, Wegener G, Lund S. The microbial metabolite indole-3-propionic acid improves glucose metabolism in rats, but does not affect behaviour. Arch Physiol Biochem 124: 306–312, 2018. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2017.1398262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agus A, Planchais J, Sokol H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 23: 716–724, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexeev EE, Lanis JM, Kao DJ, Campbell EL, Kelly CJ, Battista KD, Gerich ME, Jenkins BR, Walk ST, Kominsky DJ, Colgan SP. Microbiota-derived indole metabolites promote human and murine intestinal homeostasis through regulation of interleukin-10 receptor. Am J Pathol 188: 1183–1194, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson J, Burns PJ, Milroy D, Ruprecht P, Hauser T, Siegel HJ. Deploying RMACC Summit: an HPC resource for the Rocky Mountain region. Proceedings of the Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing 2017 on Sustainability, Success and Impact New Orleans, LA: July 2017, p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson P, McGuire J, Rubio C, Gradin K, Whitelaw ML, Pettersson S, Hanberg A, Poellinger L. A constitutively active dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces stomach tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9990–9995, 2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152706299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragozzini F, Ferrari A, Pacini N, Gualandris R. Indole-3-lactic acid as a tryptophan metabolite produced by Bifidobacterium spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 38: 544–546, 1979. doi: 10.1128/AEM.38.3.544-546.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansal T, Alaniz RC, Wood TK, Jayaraman A. The bacterial signal indole increases epithelial-cell tight-junction resistance and attenuates indicators of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 228–233, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906112107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battson ML, Lee DM, Jarrell DK, Hou S, Ecton KE, Phan AB, Gentile CL. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces arterial stiffness and improves endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice. J Vasc Res 54: 280–287, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000479967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battson ML, Lee DM, Jarrell DK, Hou S, Ecton KE, Weir TL, Gentile CL. Suppression of gut dysbiosis reverses Western diet-induced vascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 314: E468–E477, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00187.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battson ML, Lee DM, Li Puma LC, Ecton KE, Thomas KN, Febvre HP, Chicco AJ, Weir TL, Gentile CL. Gut microbiota regulates cardiac ischemic tolerance and aortic stiffness in obesity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317: H1210–H1220, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00346.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battson ML, Lee DM, Weir TL, Gentile CL. The gut microbiota as a novel regulator of cardiovascular function and disease. J Nutr Biochem 56: 1–15, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaumont M, Neyrinck AM, Olivares M, Rodriguez J, de Rocca Serra A, Roumain M, Bindels LB, Cani PD, Evenepoel P, Muccioli GG, Demoulin JB, Delzenne NM. The gut microbiota metabolite indole alleviates liver inflammation in mice. FASEB J 32: 6681–6693, 2018. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med 66: 343–359, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13: 581–583, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57: 1470–1481, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Knauf C, Burcelin RG, Tuohy KM, Gibson GR, Delzenne NM. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 50: 2374–2383, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, Gormley N, Gilbert JA, Smith G, Knight R. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 6: 1621–1624, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cason CA, Dolan KT, Sharma G, Tao M, Kulkarni R, Helenowski IB, Doane BM, Avram MJ, McDermott MM, Chang EB, Ozaki CK, Ho KJ. Plasma microbiome-modulated indole- and phenyl-derived metabolites associate with advanced atherosclerosis and postoperative outcomes. J Vasc Surg 68: 1552–1562.e7, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505: 559–563, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodd D, Spitzer MH, Van Treuren W, Merrill BD, Hryckowian AJ, Higginbottom SK, Le A, Cowan TM, Nolan GP, Fischbach MA, Sonnenburg JL. A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551: 648–652, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature24661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelhardt KR, Grimbacher B. IL-10 in humans: lessons from the gut, IL-10/IL-10 receptor deficiencies, and IL-10 polymorphisms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 380: 1–18, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43492-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evenepoel P, Claus D, Geypens B, Hiele M, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, Ghoos Y. Amount and fate of egg protein escaping assimilation in the small intestine of humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G935–G943, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, Xu K, Liu H, Liu G, Bai M, Peng C, Li T, Yin Y. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8: 13, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grasset E, Puel A, Charpentier J, Collet X, Christensen JE, Tercé F, Burcelin R. A specific gut microbiota dysbiosis of type 2 diabetic mice induces GLP-1 resistance through an enteric NO-dependent and gut-brain axis mechanism. Cell Metab 25: 1075–1090.e5, 2017. [Erratum in: Cell Metab 26: 278, 2017.] doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubbard TD, Murray IA, Perdew GH. Indole and tryptophan metabolism: endogenous and dietary routes to ah receptor activation. Drug Metab Dispos 43: 1522–1535, 2015. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.064246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huc T, Konop M, Onyszkiewicz M, Podsadni P, Szczepańska A, Turło J, Ufnal M. Colonic indole, gut bacteria metabolite of tryptophan, increases portal blood pressure in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R646–R655, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00111.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karbownik M, Stasiak M, Zasada K, Zygmunt A, Lewinski A. Comparison of potential protective effects of melatonin, indole-3-propionic acid, and propylthiouracil against lipid peroxidation caused by potassium bromate in the thyroid gland. J Cell Biochem 95: 131–138, 2005. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WH, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19: 576–585, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 165: 1332–1345, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konopelski P, Konop M, Gawrys-Kopczynska M, Podsadni P, Szczepanska A, Ufnal M. Indole-3-propionic acid, a tryptophan-derived bacterial metabolite, reduces weight gain in rats. Nutrients 11: 591, 2019. doi: 10.3390/nu11030591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan S, Ding Y, Saedi N, Choi M, Sridharan GV, Sherr DH, Yarmush ML, Alaniz RC, Jayaraman A, Lee K. Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites modulate inflammatory response in hepatocytes and macrophages. Cell Reports 23: 1099–1111, 2018. [Erratum in: Cell Rep 28: 3285, 2019.] doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto JM, Kennedy S, Leonard P, Li J, Burgdorf K, Grarup N, Jørgensen T, Brandslund I, Nielsen HB, Juncker AS, Bertalan M, Levenez F, Pons N, Rasmussen S, Sunagawa S, Tap J, Tims S, Zoetendal EG, Brunak S, Clément K, Doré J, Kleerebezem M, Kristiansen K, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, de Vos WM, Zucker JD, Raes J, Hansen T, Bork P, Wang J, Ehrlich SD, Pedersen O; MetaHIT consortium . Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 500: 541–546, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DM, Battson ML, Jarrell DK, Hou S, Ecton KE, Weir TL, Gentile CL. SGLT2 inhibition via dapagliflozin improves generalized vascular dysfunction and alters the gut microbiota in type 2 diabetic mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17: 62, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Litwin NS, Van Ark HJ, Hartley SC, Michell KA, Vazquez AR, Fischer EK, Melby CL, Weir TL, Wei Y, Rao S, Hildreth KL, Seals DR, Pagliassotti MJ, Johnson SA. Impact of red beetroot juice on vascular endothelial function and cardiometabolic responses to a high-fat meal in middle-aged/older adults with overweight and obesity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Curr Dev Nutr 3: nzz113, 2019. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manter DK, Korsa M, Tebbe C, Delgado JA. myPhyloDB: a local web server for the storage and analysis of metagenomic data. Database (Oxford) 2016: baw037, 2016. doi: 10.1093/database/baw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mimori S, Kawada K, Saito R, Takahashi M, Mizoi K, Okuma Y, Hosokawa M, Kanzaki T. Indole-3-propionic acid has chemical chaperone activity and suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 517: 623–628, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 121: 505–511, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Natividad JM, Agus A, Planchais J, Lamas B, Jarry AC, Martin R, Michel ML, Chong-Nguyen C, Roussel R, Straube M, Jegou S, McQuitty C, Le Gall M, da Costa G, Lecornet E, Michaudel C, Modoux M, Glodt J, Bridonneau C, Sovran B, Dupraz L, Bado A, Richard ML, Langella P, Hansel B, Launay JM, Xavier RJ, Duboc H, Sokol H. Impaired aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand production by the gut microbiota is a key factor in metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab 28: 737–749.e4, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 336: 1262–1267, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pulakazhi Venu VK, Saifeddine M, Mihara K, Tsai YC, Nieves K, Alston L, Mani S, McCoy KD, Hollenberg MD, Hirota SA. The pregnane X receptor and its microbiota-derived ligand indole 3-propionic acid regulate endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317: E350–E361, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00572.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redan BW, Buhman KK, Novotny JA, Ferruzzi MG. Altered transport and metabolism of phenolic compounds in obesity and diabetes: implications for functional food development and assessment. Adv Nutr 7: 1090–1104, 2016. doi: 10.3945/an.116.013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiering C, Wincent E, Metidji A, Iseppon A, Li Y, Potocnik AJ, Omenetti S, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR, Nebert DW, Stockinger B. Feedback control of AHR signalling regulates intestinal immunity. Nature 542: 242–245, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature21080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stull VJ, Finer E, Bergmans RS, Febvre HP, Longhurst C, Manter DK, Patz JA, Weir TL. Impact of edible cricket consumption on gut microbiota in healthy adults, a double-blind, randomized crossover trial. Sci Rep 8: 10762, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang WH, Hazen SL. Microbiome, trimethylamine N-oxide, and cardiometabolic disease. Transl Res 179: 108–115, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuomainen M, Lindström J, Lehtonen M, Auriola S, Pihlajamäki J, Peltonen M, Tuomilehto J, Uusitupa M, de Mello VD, Hanhineva K. Associations of serum indolepropionic acid, a gut microbiota metabolite, with type 2 diabetes and low-grade inflammation in high-risk individuals. Nutr Diabetes 8: 35, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41387-018-0046-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E, Lewis GD, Fox CS, Jacques PF, Fernandez C, O’Donnell CJ, Carr SA, Mootha VK, Florez JC, Souza A, Melander O, Clish CB, Gerszten RE. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med 17: 448–453, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nm.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wlodarska M, Luo C, Kolde R, d'Hennezel E, Annand JW, Heim CE, Krastel P, Schmitt EK, Omar AS, Creasey EA, Garner AL, Mohammadi S, O'Connell DJ, Abubucker S, Arthur TD, Franzosa EA, Huttenhower C, Murphy LO, Haiser HJ, Vlamakis H, Porter JA, Xavier RJ. Indoleacrylic acid produced by commensal Peptostreptococcus species suppresses inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 22: 25–37.e26, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yokoyama MT, Carlson JR. Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole. Am J Clin Nutr 32: 173–178, 1979. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, De Luca A, Giovannini G, Pieraccini G, Zecchi R, D’Angelo C, Massi-Benedetti C, Fallarino F, Carvalho A, Puccetti P, Romani L. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 39: 372–385, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao ZH, Xin FZ, Xue Y, Hu Z, Han Y, Ma F, Zhou D, Liu XL, Cui A, Liu Z, Liu Y, Gao J, Pan Q, Li Y, Fan JG. Indole-3-propionic acid inhibits gut dysbiosis and endotoxin leakage to attenuate steatohepatitis in rats. Exp Mol Med 51: 1–14, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0304-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]