Abstract

Inflammation is a major determinant for the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). NF-κB is a master transcription factor upregulated in CKD that promotes inflammation and regulates apoptosis and vascular remodeling. We aimed to modulate this pathway for CKD therapy in a swine model of CKD using a peptide inhibitor of the NF-κB p50 subunit (p50i) fused to a protein carrier [elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)] and equipped with a cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1). We hypothesized that intrarenal SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy would inhibit NF-κB-driven inflammation and induce renal recovery. CKD was induced in 14 pigs. After 6 wk, pigs received single intrarenal SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy (10 mg/kg) or placebo (n = 7 each). Renal hemodynamics were quantified in vivo using multidetector computed tomography before and 8 wk after treatment. Pigs were then euthanized. Ex vivo experiments were performed to quantify renal activation of NF-κB, expression of downstream mediators of NF-κB signaling, renal microvascular density, inflammation, and fibrosis. Fourteen weeks of CKD stimulated NF-κB signaling and downstream mediators (e.g., TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and IL-6) accompanying loss of renal function, inflammation, fibrosis, and microvascular rarefaction versus controls. All of these were improved after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy, accompanied by reduced circulating inflammatory cytokines as well, which were evident up to 8 wk after treatment. Current treatments for CKD are largely ineffective. Our study shows the feasibility of a new treatment to induce renal recovery by offsetting inflammation at a molecular level. It also supports the therapeutic potential of targeted inhibition of the NF-κB pathway using novel drug delivery technology in a translational model of CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, imaging, inflammation, microcirculation, NF-κB

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a complex and progressive disorder. Its course is characterized by low patient awareness during early stages that usually allows for a silent but relentless unfolding. Consequently, loss of renal function and higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality universally grow in parallel throughout CKD stages. Considering the increasing prevalence (in the United States and worldwide) and staggering health-related annual costs (45), novel therapies and early strategies to ameliorate the progression and consequences of CKD are direly needed. This need is emphasized by the fact that there is no definitive treatment for CKD, and management is focused on controlling risk factors to slow its progression (43).

A prominent pathological feature of CKD, irrespective of the etiology, is renal and systemic inflammation, which contributes to disease progression as well as cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (50, 61). Although at early stages inflammation is considered part of the compensatory mechanisms in response to injury, if left unopposed, it can progress, spread, and favor the development of fibrosis and irreversible loss of function. The kidney is not exempt from this sequence of events, since inflammation develops early and even before the deterioration of renal function and initiation of parenchymal injury. Furthermore, it is possible that the kidney is not only a target of inflammatory factors but also a source of cytokines that may further exacerbate the inflammatory milieu and compromise the renal microenvironment in a harmful positive feedback.

Our previous studies using a novel swine model of CKD mimicked the systemic and renal inflammation that is observed in patients throughout the course of CKD. Renal infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages is significant in this model and pairs with a substantial loss of renal function, microvascular rarefaction, and fibrosis (15). A major proinflammatory factor that we have shown to be involved in this process is NF-κB. This is a master transcription factor that, upon activation via a ubiquitin-mediated degradation of its natural inhibitor (IκB), translocates into the cell nucleus and induces transcription of several promoters of inflammation, apoptosis, and vascular remodeling. The primary NF-κB complex is composed of two major subunits, p50 and p65. After IκB degradation and phosphorylation of the p50/p65 complex, a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) on the p50 subunit is exposed and mediates the nuclear translocation of the activated transcription factor.

A peptide inhibitor of the nuclear translocation process was previously described [p50i (35)]. This peptide is a mimetic of the p50 NLS and, when fused to a cell-penetrating peptide, was capable of blocking NF-κB nuclear translocation, thus inhibiting its ability to activate transcription. Furthermore, our laboratory specializes in therapeutic strategies using kidney-targeted synthetic polymeric drug delivery vectors derived from human elastin, called elastin-like polypeptides (ELP) (14, 16, 27). Using the ELP drug delivery technology, a therapeutic protein was constructed that contains an NH2-terminal SynB1 cell-penetrating peptide, a 61-kDa ELP core, and a single copy of the p50i NF-κB inhibitory peptide [SynB1-ELP-p50i (53, 54)]. We (26) have previously shown that SynB1-ELP-p50i was capable of entering the cell cytoplasm of macrophages and endothelial cells grown in culture, was able to block NF-κB nuclear translocation induced by proinflammatory stimuli in these cells, and showed anti-inflammatory efficacy in vivo in a rat model of preeclampsia. Thus, the present study aimed to define whether targeting inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB pathway could improve renal recovery in CKD and tested the hypothesis that SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy in CKD would inhibit NF-κB activity and, consequently, blunt renal inflammation and improve renal injury. We also investigated the potential interactions between NF-κB inhibition and microvascular rarefaction.

METHODS

Experimental design and in vivo experiments.

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Twenty-one juvenile pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) were studied for a total of 14 wk. We induced CKD in 14 pigs through induction of bilateral renal artery stenosis and feeding with a high-cholesterol diet (15% lard and 2% cholesterol, Envigo) that was initiated immediately after induction of the stenosis and maintained for 14 wk, as previously described (15). Blood pressure was measured continuously by telemetry (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN), as previously described (11, 14), and directly at each in vivo study. An additional seven pigs underwent sham surgery, were fed a normal diet, and served as normal controls.

Six weeks after the induction of CKD, pigs were anesthetized with intramuscular telazol and xylazine, intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia was maintained with a ketamine-xylazine mixture in normal saline via an ear cannula. Renal hemodynamics were quantified in vivo using contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography (CT). Time-density curves were plotted to calculate renal blood flow (RBF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and total and regional perfusion, as previously shown and validated (14, 15, 17, 21, 32). The cortical and medullary volume of each kidney was quantified and renal vascular resistance was calculated as previously described (14, 15, 17, 21, 32). Following quantification of renal function at 6 wk, a single intrarenal administration of SynB1-ELP-p50i (10 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected through a balloon lumen into the kidney over 2 min. The balloon was inflated at 5 atm to minimize backflow and spillover of the drug/placebo. Renal hemodynamics were again quantified 8 wk posttreatment.

After 14 wk of observation and completion of in vivo experiments, pigs were euthanized (phenobarbital overdose under anesthesia), and kidneys were harvested and prepared for ex vivo morphometric analysis (quantification of renal fibrosis and microvascular remodeling), protein and mRNA expression (immunohistochemistry, immunoblot analysis, and RT-PCR) of inflammatory, fibrotic, and angiogenic factors, and microvascular density quantification using micro-CT. Blood and urine were also collected to assess serum creatinine and circulating proinflammatory cytokines [TNF-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)] using ELISA and following the vendor’s instructions.

In vivo experiments: renal function.

Renal hemodynamics and filtration were quantified in vivo in all pigs using multidetector CT (SOMATOM Sensation 64, Siemens Medical Solutions) after 6, 10, and 14 wk of observation. Manually traced regions of interest from each kidney and each region were selected and time-density curves were generated using ANALYZE (Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Time-density curves were plotted to calculate RBF, GFR, and total and regional perfusion, as previously shown and validated (14, 15, 17, 18, 21, 32, 34). The cortical and medullary volume of each kidney was quantified as previously described (14, 15, 17, 21, 32).

Ex vivo experiments: renal microvascular density and architecture.

Following euthanasia, kidneys were perfused with heparinized saline followed by a polymer contrast agent (Microfil MV122, Flow Tech, Carver, MA). After 72 h of fixation in formalin, samples were scanned using a micro-CT (SkyScan 1076, Bruker Biospin) at 0.3° increments at a resolution of 9 μm. ANALYZE was used to generate three-dimensional reconstructions and to quantify cortical and medullary microvascular density of microvessels between 0 and 500 μm, as previously described (10, 14, 15, 18).

Renal mRNA and protein expression.

For mRNA expression, cDNA was produced from the renal tissue lysate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PureLink RNA Mini Kit, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and PCR was performed to quantify mRNA expression of downstream mediators of canonical and noncanonical mediators of NF-κB signaling [IκB kinase-α (IKKα), MAP3K7/transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), and NF-κB subunit 2 (NFκB2)], TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 relative to GADPH or β-actin using the method, as previously shown (31). Commercially available primers for pigs made by ThermoFisher Scientific and Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) were used: TNF-α (qSscCIP0035447, Bio-Rad), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/MCP-1 (qSscCEP0032767, Bio-Rad), IL-6 (qSscCEP0035848, Bio-Rad), IL-10 (Ss03382372_u1, ThermoFisher Scientific), CHUK/IKKα (Ss03390001_m1, ThermoFisher Scientific), NFκB2 (Ss06883748_g1, ThermoFisher Scientific), MAP3K7/TAK1 (Ss01105673_m1, ThermoFisher Scientific), GAPDH (Ss03375629_u1, ThermoFisher Scientific), and β-actin (Ss03376563_uH, ThermoFisher Scientific). Results are expressed relative to controls and expressed as fold changes.

For renal protein expression, standard Western blot analysis was performed using renal tissue homogenates [mainly the cortex, as previously described (14–16)] and commercially available antibodies to quantify expression of phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB (ab86299, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, 1:1,000), proinflammatory TNF-α (ab6671, Abcam, 1:300) and its receptor (ab19139, Abcam, 1:500), IL-6 (ab6672, Abcam, 1:500), MCP-1 (mbs2027425, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, 1:500), profibrotic TGF-β (ab92486, Abcam,1:500), and proangiogenic VEGF (ab53465, Abcam, 1:500) and its receptor Flk-1 (ab45010, Abcam, 1:500). Protein expression was quantified relative to β-actin (1:1,000, sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), except for p-NF-κB, which was expressed as the p-NF-κB-to-IκB ratio. Five normal, six CKD, and six CKD SynB1-ELP-p50i samples were used in each gel.

Inflammatory and antiangiogenic factors.

Plasma from the inferior vena cava (below the kidneys) was collected to measure circulating proinflammatory cytokines [TNF-α (mbs2019932, MyBioSource), MCP-1 (mbs454447, MyBioSource), and IL-6 (mbs2021271, MyBioSource)] using ELISA and following the vendor’s instructions. Finally, renal concentrations of IL-1 (mbs703956, MyBioSource), antiangiogenic endostatin (mbs740247, MyBioSource), and angiostatin (mbs7204780, MyBioSource) were quantified using ELISA following the vendor’s instructions. Kidney homogenate samples were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to lyse cells and tissue while preventing protein degradation.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded midhilar 5-µm kidney sections from each animal were used to perform immunohistochemistry, as previously described (15), and costained with a nuclear marker [DAPI or deep red anthraquinone 5 (DRAQ5)] and an antibody against NF-κB (1:100, LS-C290611, LSBio) to determine the nuclear expression of NF-κB suggestive of translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus using specific image analysis software (Nikon Elements), as previously described (40). Regions of interest (15–20 regions of interest/slide from each group) were randomly selected and manually traced over individual cells to quantify mean colocalized fluorescence intensity of NF-κB by means of confocal microscopy to quantify nuclear, or active, NF-κB. Furthermore, renal expression of TNF-α receptors (AB19139, Abcam, 1:100) was quantified in paraffin-embedded midhilar 5-µm kidney slides from each animal (n = 7 per group) using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Renal morphology and morphometric analysis.

Midhilar paraffin-embedded 5-µm kidney sections from each pig were stained with trichrome (13, 15), and morphometric analysis was performed using ImageJ to quantify renal fibrosis and the microvascular media-to-lumen ratio, as previously described (9, 55).

Statistical analysis.

Power analysis of prior renal hemodynamics data revealed that a minimal n = 6 per group was sufficient to detect a difference of 11% among groups at 80% power with an α = 0.05 Results are expressed as means ± SE. Treatment groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s or Fisher tests (as indicated in the figures) for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was accepted when P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

General characteristics.

Body weights of pigs in all groups were similar at the conclusion of the study. Mean arterial pressure was similarly elevated in CKD and CKD SynB1-ELP-p50i pigs before treatment at 6 wk (Table 1). The degree of renal artery stenosis remained unchanged throughout the 14 wk of observation in both CKD groups.

Table 1.

General characteristics of each group at 6 wk (before treatment) and at 14 wk (8 wk posttreatment)

| Normal | CKD | CKD SynB1-ELP-p50i | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | |||

| Body weight, kg | 46.5 ± 5.0 | 48.2 ± 3.5 | 47.5 ± 4.3 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 100 ± 2.3 | 120.9 ± 5.8* | 121.2 ± 10.0* |

| Renal artery stenosis, % | 0 | 73.7 ± 4.2* | 76.1 ± 4.6* |

| Cortical perfusion, mL·min−1·g−1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2* | 3.8 ± 0.1* |

| Medullary perfusion, mL·min−1·g−1 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.2* | 2.7 ± 0.2* |

| Renal vascular resistance, mmHg·mL−1·min−1 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.05* | 0.26 ± 0.04* |

| Cortical volume, cm3 | 188.3 ± 11.6 | 135.8 ± 13.6* | 127.6 ± 9.5* |

| Medullary volume, cm3 | 60.2 ± 3.4 | 47.4 ± 2.1* | 43.1 ± 2.8* |

| 8 wk posttreatment | |||

| Body weight, kg | 63.3 ± 4.5 | 65.6 ± 5.3 | 64.0 ± 5.1 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 103 ± 1.6 | 126.5 ± 7.8* | 120.0 ± 8.8* |

| Cortical perfusion, mL·min−1·g−1 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2* | 4.6 ± 0.4† |

| Medullary perfusion, mL·min−1·g−1 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.3* | 3.9 ± 0.7† |

| Renal vascular resistance, mmHg·mL−1·min−1 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.01*† |

| Cortical volume, cm3 | 187.3 ± 10.8 | 141.2 ± 6.0* | 147.0 ± 7.8*†‡ |

| Medullary volume, cm3 | 60.0 ± 3.2 | 49.2 ± 2.0* | 39.8 ± 6.3†‡ |

Values are expressed as means ± SE; n = 7/group. Renal volume is presented as the sum of cortical or medullary area for both kidneys. CKD, chronic kidney disease; SynB1-ELP-p50i, peptide inhibitor of the NF-κB p50 subunit (p50i) fused to the protein carrier elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) and equipped with a cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1).

P < 0.05 vs. normal;

P < 0.05 vs. untreated CKD at 14 wk;

P < 0.05 vs. 6 wk (before treatment).

Pre- and posttreatment multidetector CT-derived quantification of renal hemodynamics in vivo.

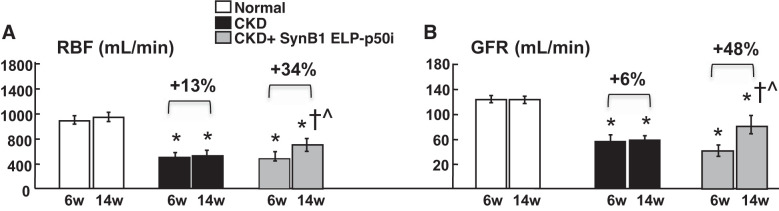

By the time of treatment at 6 wk, CKD and CKD SynB1-ELP-p50i pigs showed a similarly significant loss of RBF (−44.7% and −47.6%, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. normal) and GFR (−46.5% and −54.2%, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. normal; Fig. 1, A and B) prior to therapy with placebo or SynB1-ELP-p50i, respectively, accompanied by significant reductions in renal volume, regional perfusion, and elevated renal vascular resistance (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Renal blood flow (RBF; A) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR; B) in normal, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CKD cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1)-elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)-p50 inhibitor (p50i)-treated groups at 6 and 14 wk (n = 7/group). Both RBF and GFR were dramatically reduced in all CKD animals at 6 wk (w) and remained blunted in CKD after 14 wk. However, a single intrarenal SynB1-ELP-p50i administration induced a significant recovery of renal hemodynamics. *P < 0.05 vs. normal; †P < 0.05 vs. CKD; ^P < 0.05 vs. 6 wk (by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

At 14 wk (8 wk after treatment), CKD SynB1-ELP-p50i pigs showed a significant improvement of RBF (+33.6% vs. 6 wk, P < 0.05) and GFR (+48.6% vs. 6 wk, P < 0.05) compared with untreated CKD (+13.1% in RBF and +5.7% in GFR vs. 6 wk, P = nonsignificant) and associated with lower (albeit still higher than normal) serum creatinine compared with untreated CKD (144.7 ± 9.7 vs. 189.9 ± 22.8 SI units, P < 0.05 vs. normal for both), suggesting long-term stable recovery. Hypertension after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy was unchanged, but renal vascular resistance was improved (Table 1), driven by the significant recovery of RBF compared with 6 wk. The persistent loss of renal hemodynamics, sustained hypertension, and elevated serum creatinine and renal vascular resistance in untreated CKD throughout the 14 wk implies sustained renal injury.

Renal and systemic inflammatory activity (protein and mRNA expression).

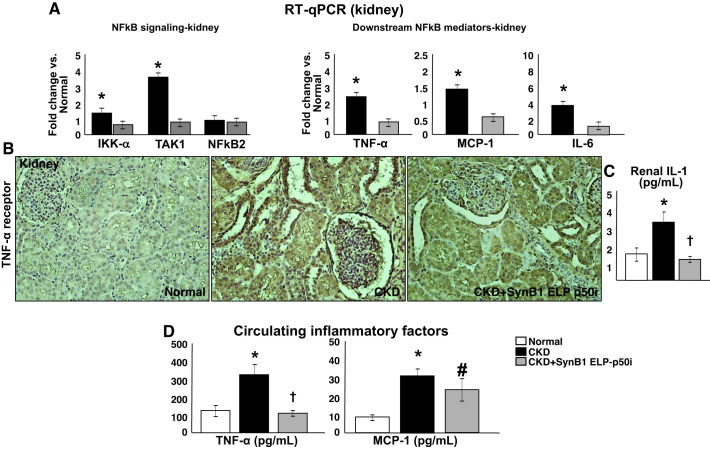

Renal expression of NF-κB was significantly increased in CKD compared with normal controls. The increased expression was observed at both cytoplasmic and nuclear levels, with a higher preference for tubular cells of the renal cortex (proximal and distal) and, to a lesser extent, renal vessels (smooth muscle and endothelial cells). Notably, SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy in CKD reduced both cytoplasmic and mainly nuclear expression of NF-κB (Fig. 2, A and B), which was accompanied by improved mRNA and protein expressions of factors involved in canonical and noncanonical mediators of NF-κB signaling (IKKα, TAK1, and NFκB2) and of downstream mediators (TNF-α, TNF-α receptor, IL-6, and MCP-1) as well as decreased renal concentration of IL-1, overall suggesting attenuated renal inflammatory activity (Fig. 3, A–D). Furthermore, SynB1-ELP-p50i also reduced circulating TNFα and MCP-1, suggesting a reduction of systemic inflammation and that the kidney is likely both a target and a source of inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Representative protein expression of phosphorylated (p-)NF-κB and quantification of nuclear and cytoplasmic expression from normal, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CKD cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1)-elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)-p50 inhibitor (p50i)-treated pigs after 14 wk of observation. A: Western blots (3 bands, n = 7/group); B: renal cross-sections. Renal protein expression of NF-κB was increased in CKD and reduced after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy. Furthermore, costaining of NF-κB (in red) with nuclear deep red anthraquinone 5 (DRAQ5; in blue) showed increased nuclear NF-κB immunoreactivity in cortical tubular (proximal and distal) cells in untreated CKD that was significantly reduced after SynB1-ELP-p50i treatement, indicating reduced nuclear translocation of NF-κB and, thus, blunted activity of this transcription factor after treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. normal; †P < 0.05 vs. CKD (n = 7/group; by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of mRNA expression (A: fold change vs. normal) of downstream mediators of canonical and noncanonical NF-κB signaling [IκB kinase-α (IKKα), MAP3K7/transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), and NF-κΒ subunit 2 (NFκB2), TNF-α, IL-6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and renal expression of TNFα receptor (B: immunohistochemistry), availability of IL-1 (C: ELISA), and circulating TNF-α and MCP-1 (D) from normal, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CKD cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1)-elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)-p50 inhibitor (p50i)-treated pigs after 14 wk of observation. Improved NF-κB activity after intrarenal SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy were accompanied by improved renal mRNA expression of downstream mediators of NF-κB and reduced renal and circulating inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that SynB1-ELP-p50i improved renal and systemic inflammation and that the kidney may be a source of inflammatory factors as well. *P < 0.05 vs. normal; †P < 0.05 vs. CKD; #P = 0.07 vs. CKD (n = 7/group, by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

Renal microvascular architecture and angiogenic factors (expression and availability).

Renal microvascular density (all microvessels < 500 µm in diameter) was reduced in both the cortex (more severe) and medulla of CKD kidneys compared with normal, associated with an increased media-to-lumen ratio and decreased protein expression of VEGF (Fig. 4, A–C). Notably, SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy in CKD significantly improved renal microvascular density compared with untreated CKD, accompanied by improved expression of VEGF and Flk-1 (Fig. 4, A–C), suggesting ameliorated microvascular regression and remodeling. This interpretation is further supported by a reduction in the renal concentration of angiostatin and endostatin, which in the context of improved VEGF/Flk-1, may suggest vascular protection and possibly a compensatory neovascularization as well (Fig. 4, A–C).

Fig. 4.

A and B: representative microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) reconstructions of the renal microvasculature and quantification of microvascular (MV) density in the cortex and medulla and MV media-to-lumen ratio. C and D: representative renal protein expression and quantification (3 bands, n = 7/group) of VEGF and its specific receptor Flk-1as well as quantification of renal concentrations of angiostatin and endostatin (ELISA) from normal, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CKD cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1)-elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)-p50 inhibitor (p50i)-treated pigs after 14 wk of observation. MV density and media-to-lumen ratio in CKD were significantly improved by SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy compared with placebo, accompanied by augmented expression of renal VEGF and Flk-1 and reduced renal concentrations of angiostatin and endostatin, indicating improved MV remodeling, repair, and, possibly, neovascularization. *P < 0.05 vs. normal; †P < 0.05 vs. CKD; #P = 0.063 vs. CKD (n = 7/group, by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

Quantification of renal fibrosis and morphometric analysis.

Renal fibrosis was significant in CKD pigs after 14 wk, as previously described (15, 27). The accumulation of fibrotic tissue was observed at the tubulointerstitial level and also within the glomerulus, disclosed by the presence of focal segmental and whole glomerulosclerosis. These changes were accompanied by significantly increased renal expression of TGF-β (in a context of increased renal inflammatory activity as well). Notably, renal fibrosis and TGF-β expression were significantly attenuated after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy, with a more powerful recovery at the tubulointerstitial and perivascular levels (Fig. 5). The reduction of renal fibrosis after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy was also accompanied by a substantial improvement in the media-to-lumen ratio of both small and large microvessels compared with untreated CKD (Fig. 4), suggesting a protective effect on the preexisting renal microvasculature.

Fig. 5.

A and B: representative renal cross-sections stained with trichrome, morphometric analysis, and renal protein expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β from normal, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CKD cell-penetrating peptide (SynB1)-elastin-like polypeptide (ELP)-p50 inhibitor (p50i)-treated pigs after 14 wk of observation. Renal fibrosis in CKD was ameliorated by SynB1-ELP-p50i, mainly evident at tubulointerstitial and perivascular levels. This was associated with improved renal expression of profibrotic TGF-β. *P < 0.05 vs. normal; †P < 0.05 vs. CKD (n = 7/group, by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

DISCUSSION

The present study supports the translational potential of a novel treatment for CKD. Using a highly translational swine model of CKD, we show the therapeutic efficacy of a new anti-inflammatory compound fused to a nonimmunogenic and species-independent protein carrier (4, 14, 16) equipped with a cell-penetrating peptide that enhanced targeted delivery. We showed that the construct could efficiently penetrate renal cells to inhibit NF-κB activity, blocking transcription of proinflammatory factors, reducing renal and systemic inflammation and renal injury, and improving renal function. Notably, the effects were sustained, as a single administration induced a significant recovery that was present 8 wk after intrarenal therapy. The novelty and significance of the present study is propelled by the limited therapeutic options available for patients with CKD, thus opening a new avenue for application of drug delivery technologies to possibly design new treatments for this progressive disorder.

The development of inflammation in CKD is a universal cause-effect pathological component. Indeed, recent studies have supported the key role of inflammation in the transition from acute kidney injury to CKD, disclosing that even a single episode of acute kidney injury can lead to CKD via multiple intricate mechanisms affecting several types of cells that participate in the progression of renal injury (46). The etiology of CKD may be diverse, but it has been postulated that common pathways, notably inflammation, activate and define the kidney microenvironment, progression of injury, and clinical outcome (5). The pivotal role of inflammation in CKD was highlighted by the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study, which showed in 3,430 patients the association of a proinflammatory milieu with rapid loss of kidney function (1). Furthermore, CKD is associated with up to a 3.5-fold increased risk for cardiovascular disease (3). However, there is a still a lack of targeted treatments for inflammation in CKD, and no drug has been shown to halt the progression toward CKD (46).

Renal and systemic inflammation are major features of our swine model of CKD. We demonstrated that the insults used to induce CKD (renal artery stenosis and diet-induced dyslipidemia) are powerful stimuli for inflammation (7, 12, 15). Proinflammatory factors such as NF-κB are upregulated in the kidney and are associated with the production and release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-1 and IL-6 (30, 60). Thus, this model presents an inflammatory milieu that may mirror the human CKD counterpart and offers an opportunity to define the feasibility of potential treatments.

The present study aimed to determine whether targeting inflammation at a molecular level might improve recovery in CKD. We chose NF-κB based on the potential central role this factor may have in CKD pathophysiology. The NF-κB p50 subunit is crucial for the translocation process and initiation of the inflammatory process (41). That was the rationale for selecting the p50 subunit as our molecular target. We (26) recently determined the efficacy of the SynB1-ELP-p50i construct in vitro and observed that NF-κB activity was reduced in endothelial cells and macrophages, evident by its reduced transduction into the nucleus after treatment with SynB1-ELP-p50i and proinflammatory stimulation. Thus, here, we extended that study by determining whether the construct could reproduce those effects in vivo in the swine model. NF-κB is a master transcription factor that is constitutively expressed in renal cells and is inactive in the cell cytoplasm in association with the inhibitor IκB. Previous studies in vivo and in vitro have shown enhanced NF-κB activation in intrinsic glomerular cells such as podocytes and mesangial, tubular, and endothelial cells (44). However, a variety of insults may lead to the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, proteolytic degradation and dissociation of IκB from NF-κB, thus activating and entering the nucleus to stimulate a battery of genes that participate in inflammation, apoptosis, and vascular remodeling, among other processes (19, 44, 48). We observed that 14 wk of CKD increased expression of NF-κB in the kidneys and was very dense throughout the renal compartments, at both cytoplasmic and nuclear levels, indicating high activation of this factor. This increase was associated with increased renal mRNA expression of downstream mediators of NF-κB such as TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6. Indeed, TNF-α is both an upstream and downstream mediator of NF-κB (29), indicating a feedback mechanism and a favorable microenvironment for the progression of renal inflammation. NF-κB is a powerful stimulus for renal production of MCP-1, which is a key player in attracting inflammatory cells to the kidneys and is expressed by several renal cells like podocytes and mesangial cells (52, 59). Similarly, NF-κB is an upstream inducer for IL-6, which is produced from activated mesangial cells and serves as a powerful stimulus for leukocyte infiltration and MCP-1 release (20) and can activate and be activated by IL-1 (33, 36), indicating a heavy interaction of these factors in the development of renal inflammation. We observed high expression of NF-κB in renal proximal and distal tubular cells of the renal cortex and to a lesser extent in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. This is not unusual, since it has been shown that CKD can cause diffuse activation of NF-κB signaling throughout the different tubular segments rather than one specific segment or renal compartment (23, 25, 39). It is possible that a part of the renal cells expressing NF-κB includes renal macrophages as well, as we showed in this model (15, 27). Interestingly, increased circulating TNF-α and MCP-1 accompanied upregulation of renal NF-κB, proinflammatory TNF-α and its receptor, IL-1, and IL-6. These data indicate that renal cells may not only be targets but also may serve as a source for production of cytokines and contribute to increase inflammation in CKD. This notion is further supported by the reduction of cytoplasmic and, mainly, nuclear expression of NF-κB after SynB1-ELP-p50i, which was observed mainly in tubular cells. Tubules are the main component of the renal parenchyma and receive the brunt of the early injury in renal disease, as tubulointerstitial alterations contribute to diminishing renal function (37). Thus, it is possible that the blockade of NF-κB activity at the tubular level in the renal cortex had a beneficial effect at the glomerular level in our study, which may serve to explain the significant recovery of GFR and play a role in the overall decrease in parenchymal injury (e.g., microvascular rarefaction and fibrosis) after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy. Furthermore, these effects after SynB1-ELP-p50i in CKD were accompanied by reduced renal mRNA and protein expression of downstream mediators of NF-κB signaling and reduced circulating inflammatory cytokines (measured in blood collected from the inferior venal cava below the kidneys) compared with untreated pigs. Without claiming a fully abolished NF-κB pathway, these data indicate efficient inhibition of renal NF-κB after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy, supporting a reduction of renal inflammatory activity and possibly systemic inflammation.

Inhibition of NF-κB activity after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy not only led to significant attenuation of chronic inflammation but also improved renal hemodynamics. A marked improvement of RBF and GFR was observed 8 wk after treatment, showing significant recovery compared with CKD placebo after this single intervention. Bilateral renovascular disease and high cholesterol feeding were still ongoing; thus, the injurious stimulus was present but the impact of progressive inflammation was offset by this targeted treatment. Inflammatory cytokines are powerful sources of reactive oxygen species, and sustained inflammation can induce endothelial dysfunction and lead to vasoconstriction (24). However, the prolonged recovery after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy argues against a sole hemodynamic effect, and it is likely that attenuation of chronic inflammation after treatment may have also reduced the structural damage of the renal parenchyma that this model displays (15).

We also observed significant protection of the renal microvascular architecture, with a more powerful effect in the cortex than in the medulla (where microvascular rarefaction was also more severe) and a substantial reduction in microvascular remodeling. NF-κB participates in microvascular remodeling and may serve as a pro- or antiangiogenic factor (38, 47, 51). Pro- and antiangiogenic factors, in turn, target the same signaling molecules toward angiogenic balance. A recent study (2) has shown that angiogenic inhibitors enhance NF-κB, whereas blockade of the NF-κB pathway abolishes the antiangiogenic force in endothelial cells. The improved renal microvascular architecture after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy was associated with improved renal expression of VEGF and Flk-1 compared with untreated CKD and a similarly reduced presence of antiangiogenic endostatin and angiostatin, which are powerful inhibitors of angiogenesis and may promote apoptosis (22) via direct effects on endothelial cells (28). The relative imbalance toward augmented VEGF may indicate a more favorable microvascular environment reflected in the reduced microvascular rarefaction and remodeling. Furthermore, NF-κB inhibition itself may have prevented microvascular loss by reducing apoptosis of endothelial cells (49, 58). Although we cannot rule out that neovascularization may have occurred, we speculate that modulation of the inflammatory milieu in the kidney, and specifically inhibition of NF-κB, may have reduced microvascular regression and remodeling, resulting in a significant protective effect on the existing vasculature, reflected by a marked recovery of RBF and GFR in CKD-treated pigs.

Limitations.

Unlike our recent work using drug delivery technologies to enhance delivery of VEGF (27), in which CKD recovery was sustained and also progressive, the present study suggests that targeting inflammation via NF-κB inhibition may require adjustments in the therapeutic scheme, possibly with additional doses to prolong recovery, which will be addressed in future studies. Similarly, future studies will focus on the specific cells that are targeted as well as whether a specific receptor for the carrier of the p50i peptide is present and defines cell binding. It is possible that the improvements observed 8 wk after SynB1-ELP-p50i therapy represent a halt or slowdown of the progression of CKD in this model compared with untreated CKD. Considering that the model may represent an early stage of the disease, additional time points of assessment as well as therapeutic attempts at more advanced stages of CKD or with additional insults (e.g., aging and metabolic syndrome traits) may serve to further define the efficacy and additional mechanisms underlying the potential long-term effects of our strategy.

Conclusions and perspectives.

We (8) have previously shown that interfering with the NF-κB signaling cascade by targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway may be beneficial for the kidney. However, based on the wide variety of activities of this pathway beyond NF-κB signaling, modulation of several pathways involved in cellular function may occur and lead to further, nonspecific tissue damage [e.g., increased oxidized lipids and fibrosis (6, 57)]. We believe that the present study is a step forward and offers a novel intervention by specifically targeting NF-κB signaling to offset inflammation. Within the complex pathophysiology of CKD, inflammation is a major component and plays a role in the progression and mortality of CKD. Hence, our results are of conceptual significance, showing that counteracting inflammation in CKD leads to recovery of renal hemodynamics, preserves renal microvascular integrity, and reduces renal fibrosis in a highly translational model of CKD. Timely recognition and early therapeutic attempts in CKD could slow progression, prevent complications, and reduce cardiovascular risk (42, 56). The data presented in this study support the translational potential of targeting inflammation at a molecular level using a novel inhibitor of NF-κB that is directed to the kidney using drug delivery technology.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL095638, P01HL51971, P20GM104357, and R01HL121527 and by American Heart Association Grants IPA34170267, PRE34380314, and PRE34380274.

DISCLOSURES

G. L. Bidwell is owner of Leflore Technologies, LLC, a private company working to develop and commercialize ELP-based technologies in several disease areas. G. L. Bidwell and A. R. Chade are inventors with patents related to ELP technology. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.R.C. conceived and designed research; A.R.C., M.L.W., J.E.E., E.W., and G.L.B. performed experiments; A.R.C., M.L.W., and J.E.E. analyzed data; A.R.C., J.E.E., and G.L.B. interpreted results of experiments; A.R.C. prepared figures; A.R.C. drafted manuscript; A.R.C., M.L.W., J.E.E., and G.L.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.R.C., M.L.W., J.E.E., and G.L.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amdur RL, Feldman HI, Gupta J, Yang W, Kanetsky P, Shlipak M, Rahman M, Lash JP, Townsend RR, Ojo A, Roy-Chaudhury A, Go AS, Joffe M, He J, Balakrishnan VS, Kimmel PL, Kusek JW, Raj DS; CRIC Study Investigators . Inflammation and progression of CKD: the CRIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1546–1556, 2016. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13121215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aurora AB, Biyashev D, Mirochnik Y, Zaichuk TA, Sánchez-Martinez C, Renault MA, Losordo D, Volpert OV. NF-kappaB balances vascular regression and angiogenesis via chromatin remodeling and NFAT displacement. Blood 116: 475–484, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernelot Moens SJ, Verweij SL, van der Valk FM, van Capelleveen JC, Kroon J, Versloot M, Verberne HJ, Marquering HA, Duivenvoorden R, Vogt L, Stroes ES. Arterial and cellular inflammation in patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1278–1285, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidwell GL III, Mahdi F, Shao Q, Logue OC, Waller JP, Reese C, Chade AR. A kidney-selective biopolymer for targeted drug delivery. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F54–F64, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00143.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black LM, Lever JM, Traylor AM, Chen B, Yang Z, Esman SK, Jiang Y, Cutter GR, Boddu R, George JF, Agarwal A. Divergent effects of AKI to CKD models on inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1107–F1118, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00179.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosmans JL, Holvoet P, Dauwe SE, Ysebaert DK, Chapelle T, Jürgens A, Kovacic V, Van Marck EA, De Broe ME, Verpooten GA. Oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins and the outcome of renal allografts at 1 1/2 years. Kidney Int 59: 2346–2356, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chade AR, Best PJ, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Sawamura T, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Endothelin-1 receptor blockade prevents renal injury in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Kidney Int 64: 962–969, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chade AR, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Krier JD, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Effects of proteasome inhibition on the kidney in experimental hypercholesterolemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1005–1012, 2005. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chade AR, Kelsen S. Renal microvascular disease determines the responses to revascularization in experimental renovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 3: 376–383, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.951277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chade AR, Kelsen S. Reversal of renal dysfunction by targeted administration of VEGF into the stenotic kidney: a novel potential therapeutic approach. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1342–F1350, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00674.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Grande JP, Krier JD, Lerman A, Romero JC, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Distinct renal injury in early atherosclerosis and renovascular disease. Circulation 106: 1165–1171, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000027105.02327.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chade AR, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Herrmann J, Zhu X, Grande JP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention blunts renal injury in experimental renovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 958–966, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000117774.83396.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chade AR, Tullos N, Stewart NJ, Surles B. Endothelin-a receptor antagonism after renal angioplasty enhances renal recovery in renovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1071–1080, 2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chade AR, Tullos NA, Harvey TW, Mahdi F, Bidwell GL III. Renal therapeutic angiogenesis using a bioengineered polymer-stabilized vascular endothelial growth factor construct. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1741–1752, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015040346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chade AR, Williams ML, Engel J, Guise E, Harvey TW. A translational model of chronic kidney disease in swine. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F364–F373, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00063.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chade AR, Williams ML, Guise E, Vincent LJ, Harvey TW, Kuna M, Mahdi F, Bidwell GL III. Systemic biopolymer-delivered vascular endothelial growth factor promotes therapeutic angiogenesis in experimental renovascular disease. Kidney Int 93: 842–854, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chade AR, Zhu X, Lavi R, Krier JD, Pislaru S, Simari RD, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Endothelial progenitor cells restore renal function in chronic experimental renovascular disease. Circulation 119: 547–557, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chade AR, Zhu X, Mushin OP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO, Chade AR, Zhu X, Mushin OP, Napoli C, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Simvastatin promotes angiogenesis and prevents microvascular remodeling in chronic renal ischemia. FASEB J 20: 1706–1708, 2006. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5680fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Chen ZJ. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination. Curr Opin Immunol 25: 4–12, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coletta I, Soldo L, Polentarutti N, Mancini F, Guglielmotti A, Pinza M, Mantovani A, Milanese C. Selective induction of MCP-1 in human mesangial cells by the IL-6/sIL-6R complex. Exp Nephrol 8: 37–43, 2000. doi: 10.1159/000059327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daghini E, Primak AN, Chade AR, Krier JD, Zhu XY, Ritman EL, McCollough CH, Lerman LO. Assessment of renal hemodynamics and function in pigs with 64-section multidetector CT: comparison with electron-beam CT. Radiology 243: 405–412, 2007. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2432060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhanabal M, Ramchandran R, Waterman MJ, Lu H, Knebelmann B, Segal M, Sukhatme VP. Endostatin induces endothelial cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 274: 11721–11726, 1999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dizin E, Hasler U, Nlandu-Khodo S, Fila M, Roth I, Ernandez T, Doucet A, Martin PY, Feraille E, de Seigneux S. Albuminuria induces a proinflammatory and profibrotic response in cortical collecting ducts via the 24p3 receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1053–F1063, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00006.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donato AJ, Pierce GL, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. Role of NFkappaB in age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction in humans. Aging (Albany NY) 1: 678–680, 2009. doi: 10.18632/aging.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drumm K, Bauer B, Freudinger R, Gekle M. Albumin induces NF-kappaB expression in human proximal tubule-derived cells (IHKE-1). Cell Physiol Biochem 12: 187–196, 2002. doi: 10.1159/000066278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddy A, Howell JA, Chapman H. A biopolymer-delivered, maternally sequestered NF-kB inhibitory peptide for treatment of preeclampsia. Hypertension 75: 193–201, 2020. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engel JE, Williams E, Williams ML, Bidwell GL III, Chade AR. Targeted VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) therapy induces long-term renal recovery in chronic kidney disease via macrophage polarization. Hypertension 74: 1113–1123, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eriksson K, Magnusson P, Dixelius J, Claesson-Welsh L, Cross MJ. Angiostatin and endostatin inhibit endothelial cell migration in response to FGF and VEGF without interfering with specific intracellular signal transduction pathways. FEBS Lett 536: 19–24, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin Immunol 26: 253–266, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iliescu R, Chade AR. Progressive renal vascular proliferation and injury in obese Zucker rats. Microcirculation 17: 250–258, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iliescu R, Fernandez SR, Kelsen S, Maric C, Chade AR. Role of renal microcirculation in experimental renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1079–1087, 2010. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krier JD, Ritman EL, Bajzer Z, Romero JC, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Noninvasive measurement of concurrent single-kidney perfusion, glomerular filtration, and tubular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F630–F638, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.4.F630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a001651, 2009. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lerman LO, Schwartz RS, Grande JP, Sheedy PF, Romero JC. Noninvasive evaluation of a novel swine model of renal artery stenosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1455–1465, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin YZ, Yao SY, Veach RA, Torgerson TR, Hawiger J. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J Biol Chem 270: 14255–14258, 1995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2: 17023, 2017. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.López-Novoa JM, Rodríguez-Peña AB, Ortiz A, Martínez-Salgado C, López Hernández FJ. Etiopathology of chronic tubular, glomerular and renovascular nephropathies: clinical implications. J Transl Med 9: 13, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma K, Wang C, Geng Q, Fan Y, Ning J, Yang H, Dong X, Dong D, Guo Y, Wei X, Li E, Wu Y. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-delivered anginex inhibits angiogenesis and growth of HUVECs by regulating the Akt, JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Oncol Rep 35: 3505–3513, 2016. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murali NS, Ackerman AW, Croatt AJ, Cheng J, Grande JP, Sutor SL, Bram RJ, Bren GD, Badley AD, Alam J, Nath KA. Renal upregulation of HO-1 reduces albumin-driven MCP-1 production: implications for chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F837–F844, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00254.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noursadeghi M, Tsang J, Haustein T, Miller RF, Chain BM, Katz DR. Quantitative imaging assay for NF-kappaB nuclear translocation in primary human macrophages. J Immunol Methods 329: 194–200, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panzer U, Steinmetz OM, Turner JE, Meyer-Schwesinger C, von Ruffer C, Meyer TN, Zahner G, Gómez-Guerrero C, Schmid RM, Helmchen U, Moeckel GW, Wolf G, Stahl RA, Thaiss F. Resolution of renal inflammation: a new role for NF-κB1 (p50) in inflammatory kidney diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F429–F439, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90435.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plantinga LC, Tuot DS, Powe NR. Awareness of chronic kidney disease among patients and providers. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 17: 225–236, 2010. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg M. UpToDate. Overview of the Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults [1 April 1, 2020].

- 44.Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ramos AM, Moreno JA, Santamaria B, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A. NF-kappaB in renal inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1254–1262, 2010. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bhave N, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, Dietrich X, Eckard A, Eggers PW, Gaipov A, Gillen D, Gipson D, Hailpern SM, Hall YN, Han Y, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Hutton D, Jacobsen SJ, Jin Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kapke A, Kovesdy CP, Lavallee D, Leslie J, McCullough K, Modi Z, Molnar MZ, Montez-Rath M, Moradi H, Morgenstern H, Mukhopadhyay P, Nallamothu B, Nguyen DV, Norris KC, O’Hare AM, Obi Y, Park C, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Potukuchi PK, Rao P, Repeck K, Rhee CM, Schrager J, Schaubel DE, Selewski DT, Shaw SF, Shi JM, Shieu M, Sim JJ, Soohoo M, Steffick D, Streja E, Sumida K, Tamura MK, Tilea A, Tong L, Wang D, Wang M, Woodside KJ, Xin X, Yin M, You AS, Zhou H, Shahinian V. US renal data system 2017 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 71, Suppl 1: A7, 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato Y, Yanagita M. Immune cells and inflammation in AKI to CKD progression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: F1501–F1512, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00195.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Si W, Xie W, Deng W, Xiao Y, Karnik SS, Xu C, Chen Q, Wang QK. Angiotensin II increases angiogenesis by NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activation of angiogenic factor AGGF1. FASEB J 32: 5051–5062, 2018. doi: 10.1096/fj.201701543RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song N, Thaiss F, Guo L. NFkappaB and kidney injury. Front Immunol 10: 815, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staiger K, Staiger H, Weigert C, Haas C, Häring HU, Kellerer M. Saturated, but not unsaturated, fatty acids induce apoptosis of human coronary artery endothelial cells via nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Diabetes 55: 3121–3126, 2006. doi: 10.2337/db06-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stenvinkel P, Heimbürger O, Paultre F, Diczfalusy U, Wang T, Berglund L, Jogestrand T. Strong association between malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 55: 1899–1911, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sui X. Inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway on endothelial cell function and angiogenesis in mice with acute cerebral infarction. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 33: 375–384, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung FL, Zhu TY, Au-Yeung KK, Siow YL, O K. Enhanced MCP-1 expression during ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by oxidative stress and NF-kappaB. Kidney Int 62: 1160–1170, 2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas EH. Optimizing the Delivery of Therapeutic Peptides Using Elastin-Like Polypeptide (Master’s thesis). Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas EH, Raucher D. A thermally targeted carrier of p50 NLS peptide inhibits cancer cell proliferation by preventing NFκB nuclear translocation. Cancer Res 70: 2659, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tullos NA, Stewart NJ, Davidovich R, Chade AR. Chronic blockade of endothelin A and B receptors using macitentan in experimental renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 584–593, 2015. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuot DS, Zhu Y, Velasquez A, Espinoza J, Mendez CD, Banerjee T, Hsu CY, Powe NR. Variation in patients’ awareness of CKD according to how they are asked. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1566–1573, 2016. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00490116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vieira O, Escargueil-Blanc I, Jürgens G, Borner C, Almeida L, Salvayre R, Nègre-Salvayre A. Oxidized LDLs alter the activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: potential role in oxidized LDL-induced apoptosis. FASEB J 14: 532–542, 2000. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Kotamraju S, Konorev E, Kalivendi S, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB during doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells and myocytes is pro-apoptotic: the role of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J 367: 729–740, 2002. doi: 10.1042/bj20020752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei M, Li Z, Xiao L, Yang Z. Effects of ROS-relative NF-κB signaling on high glucose-induced TLR4 and MCP-1 expression in podocyte injury. Mol Immunol 68, 2 Pt A: 261–271, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu XY, Chade AR, Krier JD, Daghini E, Lavi R, Guglielmotti A, Lerman A, Lerman LO. The chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 contributes to renal dysfunction in swine renovascular hypertension. J Hypertens 27: 2063–2073, 2009. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283300192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimmermann J, Herrlinger S, Pruy A, Metzger T, Wanner C. Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 55: 648–658, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]