Abstract

The Sol–gel method is successfully used to prepare high specific surface area TiO2 (HSTiO2). Then, the photodeposition method is used to composite silver particles with HSTiO2. X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller, and UV–vis spectroscopy are used to characterize the Ag/HSTiO2 nanocomposites. It can be concluded that the prepared TiO2 has a large specific surface area, reaching 125.5 m2 g–1. Additionally, the addition of silver particles successfully broadens the photoresponse range from the UV region to the visible light region. In order to evaluate the photocatalytic activity of Ag/HSTiO2, we conducted the methyl orange degradation test. The results showed that the photocatalytic activity of the sample is significantly higher than that of pure TiO2.

1. Introduction

For the past few years, economic development and industrialization lead the rapid improvement of people’s living standards.1−4 At the same time, they also expose serious environmental pollution problems, leading to environmental degradation, threatening human health and impeding sustainable development.5−8 However, the development of science and technology results from the improvement of the semiconductor photocatalytic technology, which becomes a hot spot in research and can effectively solve these problems.9

Semiconductors such as ZnO and TiO2 are widely used in the field of photocatalysis.3,10−12 TiO2 as a photocatalytic semiconductor exhibits the following advantages. First, TiO2 is safe and nontoxic, so it is not harmful to the human body. Second, TiO2 is widely present in the earth’s crust. Third, TiO2 is cheap and the production cost is low. It is worth noting that the disadvantages of TiO2 are also obvious. For example, TiO2 can absorb most of the ultraviolet light, but it can only absorb a small part of visible light, and its photogenerated electrons can easily reorganize. In order to solve these problems and improve the photocatalytic activity of TiO2, researchers came up with the following strategies: combination of metal or nonmetallic elements to TiO2 and other semiconductors, increasing the specific surface area of TiO2 to expose more active sites, alternatively. These methods can synergistically increase the photocatalytic activity of TiO2.

The deposition of precious metals such as Au, Pt, and Ag on the surface of TiO2 can reduce the recombination rate of h+/e– and transfer photogenerated electrons.1,13−15 Compared with many other precious metals, for example, Au and Pt, Ag have the characteristics of relatively low price and excellent performance, which are widely used in the synthesis of composite catalysts. It is worth noting that Ag nanoparticles are very easy to aggregate during the photocatalyst catalyzing reaction and will lose activity after several reactions.16,17 Therefore, researchers load Ag nanoparticles onto the surface of the semiconductor TiO2 to form composite materials. This strategy can effectively broaden the spectral response range of TiO2 from the ultraviolet region expanding to the visible region. Moreover, the strategy can also prevent the agglomeration of Ag nanoparticles that also synergistically improves photocatalytic activity. There are some reported methods for preparing Ag/TiO2 composites, and related experiments have confirmed that Ag/TiO2 composites have higher degradation activity than pure TiO2.18−20 However, these methods have the following problems: First, the energy consumption of the preparation process is large. Second, the preparation process is more complex and fewer products are obtained. Third, cycle stability is poor and the product is difficult to reuse.

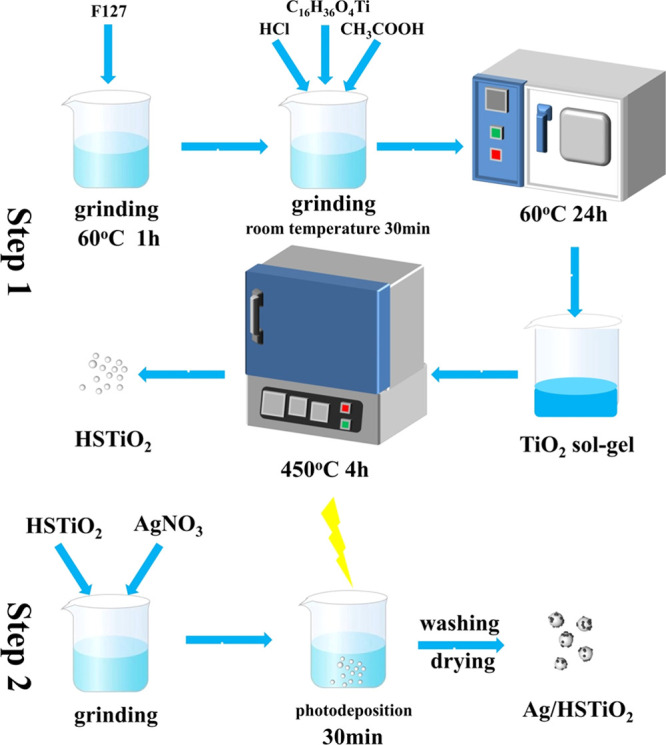

In order to solve the abovementioned problems, we have studied a preparation method. In the first place, the high specific surface area TiO2 (HSTiO2) has been prepared by a sol–gel method. The HSTiO2 has a widened bandgap because of the quantum size effect, thereby improving its photocatalytic performance. In the second place, the Ag nanoparticles are deposited on HSTiO2 by photodeposition, which is simple for preparation with high recycling efficiency. (By adding different quantities of silver nitrate, the mass ratio of AgNO3 to HSTiO2 is 5, 10, 15, and 20%; we name these four samples 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2, respectively.) At last, the effects of the photocatalytic reaction mechanism and different contents of Ag on photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange are analyzed. The synthesizing process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation procedure of Ag/HSTiO2 composites.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Ag/HSTiO2 Composite Photocatalyst

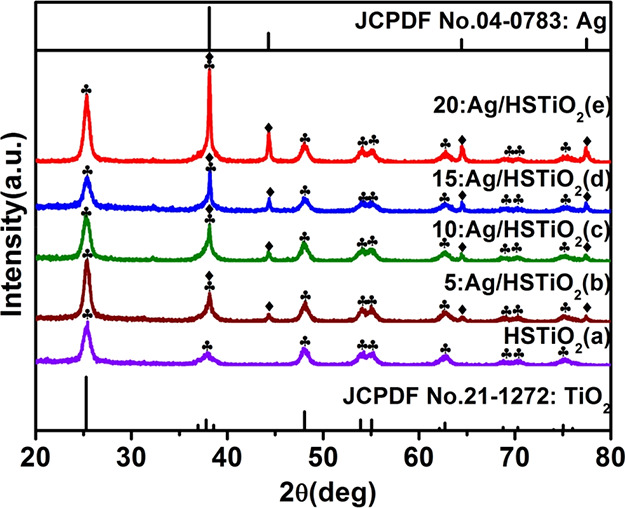

The XRD pattern of the prepared sample is given in Figure 2 to facilitate the study of the phase structure of the sample. Figure 2a shows the diffraction pattern of HSTiO2. By comparison with the TiO2 standard card (JCPDS card no. 21-1272), it is found that all the diffraction peaks of Figure 2a are consistent with the anatase of TiO2. Figure 2b–e are diffraction patterns of 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2 and 20:Ag/HSTiO2, respectively. All the diffraction peaks of the patterns are well-consistent with the TiO2 (JCPDS card no. 21-1272) and Ag (JCPDS card no. 04-0783). It is fully proved that these four samples are composite structures of Ag and TiO2 and have no other impurities.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of HSTiO2 (a), 5:Ag/HSTiO2 (b), 10:Ag/HSTiO2 (c), 15:Ag/HSTiO2 (d), and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 (e).

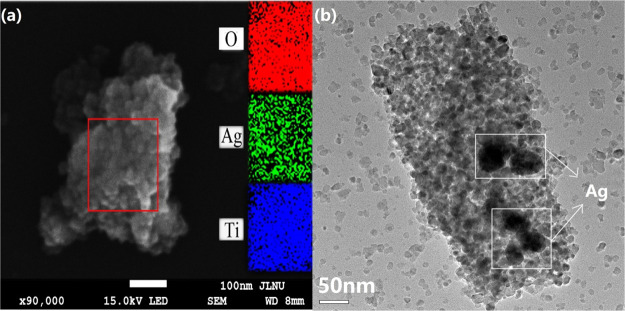

In order to study the morphology of the prepared 15:Ag/HSTiO2 composite photocatalyst, we provided its scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image. As can be seen from Figure 3a, Ag particles adhere to TiO2 and are tightly bonded to TiO2. The EDS images reveal a uniform distribution of O, Ag, and Ti elements in the area under study and the inset area colored red, green, and blue, respectively,represents them. Figure 3b is the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of 15:Ag/HSTiO2. It can be seen from Figure 3b that on the 50 nm scale, it can be clearly observed that the round silver particles are composited to the HSTiO2. It is well-known that the photocatalytic activity of photocatalysts is related to the lifetime of photogenerated electrons and holes.21 The structure in which Ag particles are combined with TiO2 is advantageous for prolonging the lifetime of photogenerated electrons, thereby increasing photocatalytic activity. The following work will confirm this result.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM image and EDS mapping of 15:Ag/HSTiO2. (b) TEM image of 15:Ag/HSTiO2.

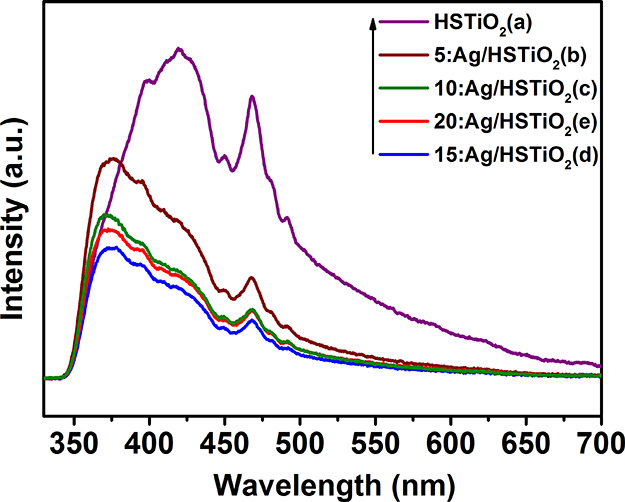

Figure 4 shows the PL spectra of HSTiO2, 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2. The emission intensity of HSTiO2 is higher than that of other samples, which means more carrier recombination in HSTiO2 samples. The emission intensity of the other samples is lower than that of HSTiO2; this shows that the combination of HSTiO2 and Ag nanoparticles can effectively reduce the recombination rate of electron–hole pairs. Ag nanoparticles can effectively transfer photogenerated electrons. It can be seen from Figure 4 that the PL peak intensity of 15:Ag/HSTiO2 is lower than that of other samples, indicating that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has the lowest photogenerated electron and hole recombination rate.

Figure 4.

PL spectra of HSTiO2 (a), 5:Ag/HSTiO2 (b), 10:Ag/HSTiO2 (c), 15:Ag/HSTiO2 (d), and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 (e).

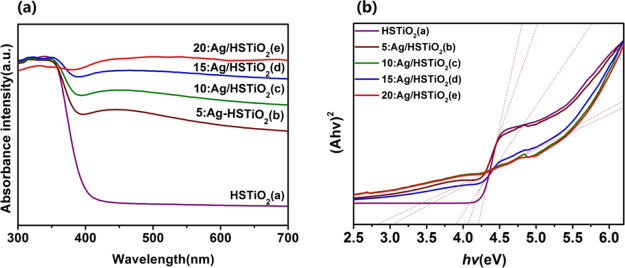

In order to explore the light absorption capacity of different samples, we give the UV–vis absorption spectra. As can be seen from Figure 5a, HSTiO2 displays an intrinsic absorption peak in the ultraviolet region. Ag/HSTiO2 samples have an absorption peak from the ultraviolet region to the visible range. Additionally, the absorption peak of Ag/HSTiO2 samples in the ultraviolet region is consistent with the position of the intrinsic absorption peak of TiO2 in the ultraviolet region. As the Ag content increases, the light absorption of the Ag/HSTiO2 composite photocatalyst increases in the visible range. It can be concluded that Ag/HSTiO2 has a wider light absorption region than HSTiO2 and can sufficiently absorb visible light, thereby producing higher photocatalytic activity.

Figure 5.

(a) UV–visible absorption spectra of HSTiO2, 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2. (b) Plots of (Ahν)2 vs photo energy (hν) for 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 composites.

Because TiO2 is an indirect bandgap material, the bandgap energy can be estimated from the intercept of the tangent line between (Ahν)2 and the photo energy (hν) diagram. As shown in Figure 5b, the bandgap of HSTiO2 is found to be 4.2 eV. The bandgaps of the materials 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 are 4.1, 3.8, 3.0 and 2.8 eV, respectively. Additionally, the bandgap gradually decreases with the increase in Ag combination. Therefore, it can be speculated that HSTiO2 of composite silver has better photocatalytic activity than HSTiO2.

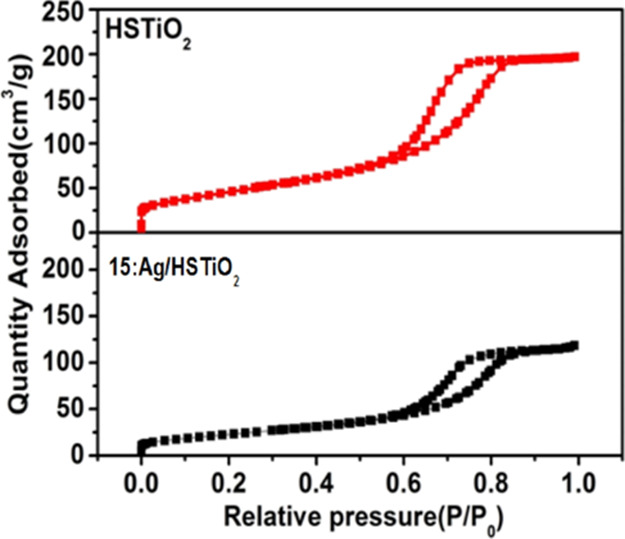

The results of Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area values for HSTiO2 and 15:Ag/HSTiO2 and matched case–control data set are listed in Table 1. The specific surface area values of HSTiO2 and 15:Ag/HSTiO2 are 125.5 and 86.8 m2 g–1, respectively. The results indicate that HSTiO2 and 15:Ag/HSTiO2 prepared in our work possess high specific surface area. Figure 6 shows the N2 adsorption–desorption curves of HSTiO2 and 15:Ag/HSTiO2. Figure 6 displays type IV adsorption–desorption isotherms of the 15:Ag/HSTiO2 sample, which are typical characteristics of mesoporous materials.

Table 1. Specific Surface Area of TiO2, Ag/TiO2, HSTiO2, and 15:Ag/HSTiO2.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption–desorption curves of HSTiO2 and 15:Ag/HSTiO2.

2.2. Photocatalytic Activity

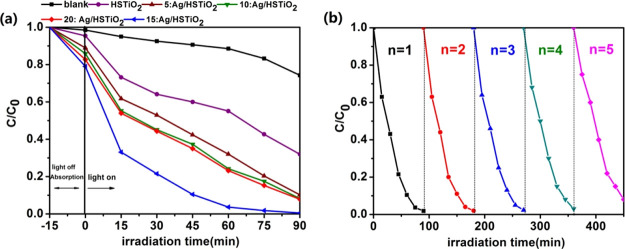

To evaluate the photocatalytic activity of different samples, we perform an experiment to degrade methyl orange under the full spectrum. The solution is allowed to reach absorption–desorption equilibrium in a dark room for 15 min.

It can be concluded from the Figure 7a that with the moderate increase in Ag content, the photocatalytic activity of Ag/HSTiO2 increases gradually, and 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has the strongest photocatalytic activity. However, excessive Ag nanoparticles obscure light, which causes scattering of light and reduces the optical receiving capacity of HSTiO2. This results in weaker photocatalytic activity of 20:Ag/HSTiO2 than 15:Ag/HSTiO2. In Wang et al. work, they prepared Ag-doped Bi5O7I composites with different Ag contents to degrade methyl orange.27 Their results also indicate that the excessive Ag would decline the photocatalytic activity of the photocatalytic semiconductor, which is consistent with our observation.

Figure 7.

(a) Photodegradation performance of methyl orange composites under the full spectrum and (b) recycling tests of 15:Ag/HSTiO2 for methyl orange photodegradation.

Table 2 is the comparison between the catalytic efficiency of our prepared catalyst and the results reported in other literature. From Table 2, we know that the catalytic rate of the catalyst we prepared is significantly higher than that reported in other literature.

Table 2. Comparison of the catalytic rate of 15:Ag/HSTiO2 and from other literature.

| photocatalyst | pollutant | degradation time (min) | degradation efficiency (%) | light source | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15:Ag/HSTiO2 | methyl orange | 90 | 99.995 | 500W Xenon lamp | in this work |

| SiO2–TiO2 | methyl orange | 120 | 92.9 | 20W UV lamp | (28) |

| Ag–TiO2 | methyl orange | 120 | 65.4 | UV light (200-400 nm) | (29) |

| GO/TiO2 | methyl orange | 240 | 85.4 | 48W ultraviolet light | (30) |

Photocatalyst recycling capacity is also an important indicator in practical applications. After five rounds of cycle experiments, it is found that the degradation ability of the 15:Ag/HSTiO2 composite photocatalyst does not decrease significantly, which proved that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has good recyclability.

2.3. Photocatalytic Mechanism

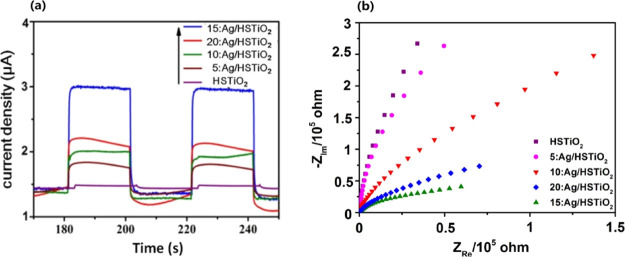

Photocurrent tests of HSTiO2, 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 are shown in Figure 8a. By comparing the photocurrent time–curve curves of different samples in the dark and visible light in the switching cycle mode, it can be concluded that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has the highest photocurrent intensity compared with other samples, which proves that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has highest electron–hole separation efficiency. Figure 8b shows that the 15:Ag/HSTiO2 electrode exhibits a more depressed semicircle at high frequency than other sample electrodes, thus manifesting a faster charge carrier transfer rate over 15:Ag/HSTiO2 than in other samples. It is indicated that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has the highest catalytic activity than other samples, which is in agreement with the experimental results of dye degradation.

Figure 8.

(a) Photocurrent response curves of HSTiO2, 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, 15:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20:Ag/HSTiO2 and (b) electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots of samples.

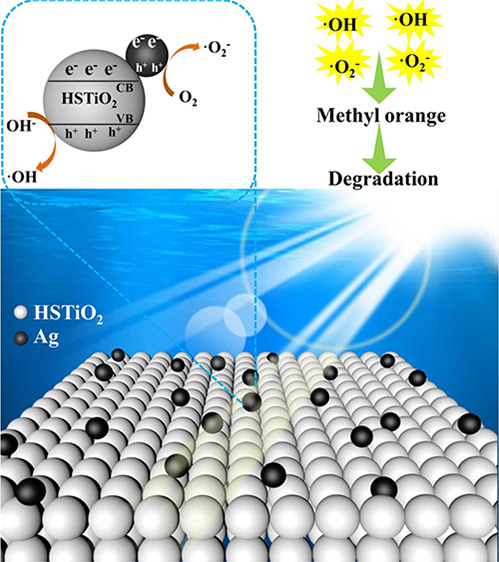

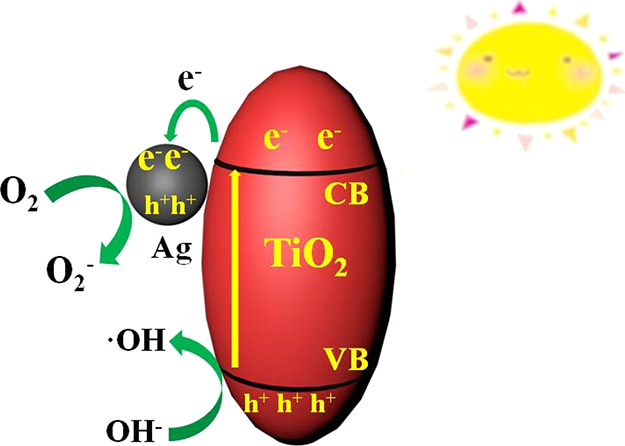

Figure 9 shows the mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange by the Ag/HSTiO2 composite photocatalyst. Under light irradiation conditions, the valence band (VB) electrons (e–) of the TiO2 are excited onto the conduction band (CB) while producing a hole (h+) in the valence band. The electrons on the titanium dioxide conduction band are rapidly transferred to the silver, and the silver has a good electron storage capacity, which effectively prolongs the lifetime of the photogenerated electrons. Photogenerated electrons react with oxygen adsorbed on the surface of the silver to form superoxide radicals, and holes in the valence band of titanium dioxide can absorb electrons on the hydroxyl group and generate hydroxyl radicals. The resulting active substances superoxide radicals (•O2–), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and photogenerated holes (h+) can degrade methyl orange.

Figure 9.

Photocatalytic mechanism of Ag/HSTiO2 under visible light irradiation.

3. Conclusions

We successfully prepared an Ag/HSTiO2 composite photocatalyst by the photodeposition method and the material exhibited good photocatalytic performance. Good stability and durability are maintained after five rounds of cycling experiments. It is found that 15:Ag/HSTiO2 has the highest photocatalytic activity in the composite. In summary, Ag/HSTiO2 is a good material for degrading dyes in sewage. This research can also lay the foundation for exploring more photocatalysts in the future.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Methanol (99.9%), titanium dioxide (>99.5%), silver nitrate (99%), tetrabutyl titanate (>98%), hydrochloric acid (>95%), acetic acid (>95%), and poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(propylene glycol)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) (F127) were all supplied by Shanghai Chemistry Co., Ltd. Deionized water comes from the analytical laboratory. All the abovementioned reagents are of analytical grade.

4.2. Synthesis of Samples

4.2.1. Synthesis of HSTiO2

The experimental method for obtaining HSTiO2 is as follows. First, 1.6 g of F127 is added to 30 mL of ethanol. Then, 3.5 mL of tetrabutyl titanate, 2.3 mL of acetic acid, and 0.7 mL of hydrochloric acidare added. After stirring at 60 °C until they were completely dissolved, the beaker containing the mixed solution is placed in an electric blast drying oven for 10 h, and then, the sample is calcined at 450 °C for 4 h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

4.2.2. Synthesis of Ag–HSTiO2 Composites

The method of making Ag/HSTiO2 is as follows. A total of 0.8 g of HSTiO2 and different quantities of AgNO3 (0.04, 0.08, 0.12, and 0.16 g) are added to 40 mL of methanol. The beaker is placed under a xenon lamp (500 W) for half an hour while stirring. After the reaction is completed, the solution is centrifuged in the beaker to obtain a sample; then, it is washed three times with ethanol and dried at 60 °C for 10 h.

4.3. Characterization

The pattern of the sample is obtained by X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) through a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffraction system having a high intensity CuKa radiation (40 kV, 200 mA) of 20–70° and a scanning step of 10°/min. The surface morphology is discussed by SEM (JSM-6510) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The TEM image is acquired on a JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the photocatalyst are measured at room temperature with 385 nm as the excitation wavelength and a Xe lamp as the source of excitation. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra are obtained on a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrometer using BaSO4 as a reference. The BET surface area of the samples is determined from an N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm study at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K) using a Micro-meritics TRiStarII3020.

4.4. Photocatalytic Experiments

To evaluate the photocatalytic properties of samples with different Ag contents, we use visible light irradiation (500W xenon lamp) methyl orange solution. Five 40 mL portions of methyl orange solution at a concentration of 10–4 mol/L are taken, and 0.04 g of different samples is separately dispersed in the methyl orange solution. After starting to irradiate the solution with a Xenon lamp, 4 mL of the solution is collected every 15 min to test the absorbance of the solution. The solution is stirred in a dark room for 15 min to the adsorption–desorption equilibrium. After starting the irradiation, 4 mL of the solution is collected every 15 min to test the absorbance of the solution.

4.5. Photoelectrochemical Measurement

The photoelectrochemical (PEC) measurements are performed on a CHI-760E electrochemical analyzer from Shanghai ChenHua Instruments Co., Ltd. The electrodes required for the test were prepared by following the following steps before performing the test. A total of 0.2 g of the sample is dispersed in 15 mL of acetone and uniformly spread on a 1 cm × 1 cm fluorine-doped tin oxide glass electrode, and after drying with a hairdryer, the obtained photocatalyst film is used as a working electrode. The counter electrode is the platinum, and the reference electrode is the silver/silver chloride. A Xe lamp (500W) is used as the light source for illumination.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31540035, 61308095, and 21801092), the program for the development of science and technology of Jilin province (Item no. 20180520002JH), and the Thirteenth Five-Year Program for Science and Technology of Education Department of Jilin Province (Item no. JJKH20180769KJ and JJKH20180778KJ).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01832.

BET surface areas of 5:Ag/HSTiO2, 10:Ag/HSTiO2, and 20: Ag/HSTiO2. XRD patterns of Ag/HSTiO2 after photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. Degradation performance of samples on methyl orange under dark conditions. XPS of 15:Ag/HSTiO2 and wide scan spectra Ag 3d, O 1s, and Ti 2p (PDF)

Author Contributions

# M.L. and R.G. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bae J. Y.; Jang S. G. Preparation and Characterization of CuO-TiO2 Composite Hollow Nanospheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 6363–6368. 10.1166/jnn.2019.17050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Song Y.; Wang F.; Sheng Y.; Zou H. Electrospinning synthesis of SiO2-TiO2 hybrid nanofibers with large surface area and excellent photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 488, 284–292. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M.; Negi K.; Chauhan S.; Umar A.; Kumar R.; Masuda Y.; Chauhan M. S.; Rajni Synthesis, characterization, photocatalytic and sensing properties of Mn-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 8095–8103. 10.1166/jnn.2019.16758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A. M.; Siwach R.; Kumar S.; Alhazaa A. N. Role of Fe doping in tuning photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical properties of TiO2 for photodegradation of methylene blue. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 118, 170–178. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tijani J. O.; Momoh U. O.; Salau R. B.; Bankole M. T.; Abdulkareem A. S.; Roos W. D. Synthesis and characterization of Ag2O/B2O3/TiO2 ternary nanocomposites for photocatalytic mineralization of local dyeing wastewater under artificial and natural sunlight irradiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 19942–19967. 10.1007/s11356-019-05124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungan H.; Tekin T. Effect of the sonication and coating time on the photocatalytic degradation of TiO2, TiO2-Ag, and TiO2-ZnO thin film photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2019, 207, 896. 10.1080/00986445.2019.1630395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Zhang M.; Zhang M.; Aizezi M.; Zhang Y.; Hu J.; Wu G. In-situ mineralized robust polysiloxane–Ag@ZnO on cotton for enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 217, 15–25. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Huang Y.; Dan Y.; Jiang L. P3HT/Ag/TiO2 ternary photocatalyst with significantly enhanced activity under both visible light and ultraviolet irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 488, 228–236. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L.; Feng Y.; Li H.; Chen Y.; Wen J.; Zhu J.; Bian Z. Microwave induced surface enhanced pollutant adsorption and photocatalytic degradation on Ag/TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 483, 772. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan K.; Shamshi H.; Lee-Woon J.; Jin Hyeon Y.; Haeng-Keun A.; Myung-Seob K.; In-Hwan L. Low-temperature synthesis of ZnO quantum dots for photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye under UV irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 14827–14831. [Google Scholar]

- Singh J.; Sahu K.; Mohapatra S. Thermal annealing induced evolution of morphological, structural, optical and photocatalytic properties of Ag-TiO2 nanocomposite thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 129, 317–323. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2019.01.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truc N. T. T.; Duc D. S.; Van Thuan D.; Tahtamouni T. A.; Pham T.-D.; Hanh N. T.; Tran D. T.; Nguyen M. V.; Dang N. M.; Le Chi N. T. P.; Nguyen V. N. The advanced photocatalytic degradation of atrazine by direct Z-scheme Cu doped ZnO/g-C3N4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 489, 875–882. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Zhang D.; Gao Y.; Wu Y.; Liu Q.; Liu Q.; Zhu X. Synthesis and characterization of cubic Ag/TiO2 nanocomposites for the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solutions. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 110, 107589. 10.1016/j.inoche.2019.107589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K.; Inoue M.; Hagiwara H.; Abe T. Photocatalytic water splitting over Pt-loaded TiO2 (Pt/TiO2) catalysts prepared by the polygonal barrel-sputtering method. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 254, 7–14. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solakidou M.; Giannakas A.; Georgiou Y.; Boukos N.; Louloudi M.; Deligiannakis Y. Efficient Photocatalytic water-splitting performance by ternary CdS/Pt-N-TiO2 and CdS/Pt-N, F-TiO2: interplay between CdS photo corrosion and TiO2-dopping. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 254, 194–205. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Wang M.; Liu L.; Liang Y.; Cui W.; Zhang Z.; Yun N. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants over flower-like Bi2O2CO3 dotted with Ag@AgBr. Materials 2016, 9, 882. 10.3390/ma9110882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.; Lin S.; Liu L.; Hu J.; Cui W. Oil-in-water Self-assembled Ag@AgCl QDs Sensitized Bi2WO6 : Enhanced photocatalytic degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal., B 2015, 164, 192–203. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.08.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Zhang D.; Ming L.; Jiao Y.; Chen F. Synergistic effect of interfacial lattice Ag+ and Ag0 clusters in enhancing the photocatalytic performance of TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 19358–19364. 10.1039/c4cp02658f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebleanu D.; Gaidau C.; Voicu G.; Constantinescu C. A.; Mansilla Sánchez C.; Rojas T. C.; Carvalho S.; Calin M. The impact of photocatalytic Ag/TiO2 and Ag/N-TiO2 nanoparticles on human keratinocytes and epithelial lung cells. Toxicology 2019, 416, 30–43. 10.1016/j.tox.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Pai M. R.; Kaur G.; Divya; Satsangi V. R.; Dass S.; Shrivastav R. Efficient hydrogen generation on CuO core/AgTiO2 shell nano-hetero-structures by photocatalytic splitting of water. Renewable Energy 2019, 136, 1202–1216. 10.1016/j.renene.2018.09.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadi M. W.; Mohamed R. M. Synthesis of BaCeO3 nanoneedles and the effect of V, Ag, Au, Pt doping on the visible light hydrogen evolution in the photocatalytic water splitting reaction. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 138–145. 10.1007/s10971-019-05018-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oladipo G. O.; Akinlabi A. K.; Alayande S. O.; Msagati T. A. M.; Nyoni H. H.; Ogunyinka O. O. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of silver and zinc co-doped TiO2 nanoparticle for photodegradation of methyl orange dye in aqueous solution. Can. J. Chem. 2019, 97, 642–650. 10.1139/cjc-2018-0308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Liu C. Y.; Wei J. H.; Xiong R.; Pan C. X.; Shi J. Enhanced adsorption and visible-light-induced photocatalytic activity of hydroxyapatite modified Ag–TiO2 powders. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6390–6394. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang R.; He M.; Huang H.; Feng Q.; Ji J.; Zhan Y.; Leung D. Y. C.; Zhao W. Effect of redox state of Ag on indoor formaldehyde degradation over Ag/TiO2 catalyst at room temperature. Chemosphere 2018, 213, 235–243. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D.-H.; Yu X.; Wang C.; Liu X.-C.; Xing Y. Synthesis of natural cellulose-templated TiO2/Ag nanosponge composites and photocatalytic properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2781–2787. 10.1021/am3004363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H.; Fei Z.; Bian C.; Yu L.; Chen S.; Qian Y. Facile synthesis of high-performance photocatalysts based on Ag/TiO2 composites. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 12586–12589. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.03.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Li X.; Dong Y.; Li X.; Chu M.; Li N.; Dong Y.; Xie Z.; Lin Y.; Cai W.; Zhang C. Preparation of Ag-doped Bi5O7I composites with enhanced visible-light-induced photocatalytic performance. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 2797–2809. 10.1007/s11164-019-03763-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Han X.; Zhang W.; He H. Characterization of SiO2-TiO2 and photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 26, 3837–3839. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Zhang D.; Gao Y.; Wu Y.; Liu Q.; Zhu X. Synthesis and characterization of cubic Ag/TiO2 nanocomposites for the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in aqueous solutions. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 110, 107589. 10.1016/j.inoche.2019.107589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.; Gao Y.; Zhang J.; Xue D.; Fang H.; Tian J.; Zhou C.; Zhang C.; Li Y.; Li H.; Li H. GO/TiO2 Composites as a highly active photocatalyst for the Degradation of Methyl Orange. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 1307–1315. 10.1557/jmr.2020.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.