Abstract

Alternatives to blood for use in transfusion medicine have been investigated for decades. An ideal alternative should improve oxygen (O2)-carrying capacity and O2 delivery and support microvascular blood flow. Previous studies have shown that large-molecular diameter hemoglobin (Hb)-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) based on polymerized bovine Hb (PolybHb) reduce the toxicity and vasoconstriction of first-generation HBOCs by increasing blood and plasma viscosity and preserving microvascular perfusion. The objective of this study was to examine the impact of PolybHb concentration and therefore O2-carrying capacity and solution viscosity on resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock in rats. PolybHb was diafiltered on a 500-kDa tangential flow filtration (TFF) module to remove low-molecular weight (MW) PolybHb molecules from the final product. Rats were hemorrhaged and maintained in hypovolemic shock for 30 min before transfusion of PolybHb at 10 g/dL (PHB10), 5 g/dL (PHB5), or 2.5 g/dL (PHB2.5) concentration, to restore blood pressure to 90% of the animal’s baseline blood pressure. Resuscitation restored blood pressure and cardiac function in a PolybHb concentration-dependent manner. Parameters indicative of the heart’s metabolic activity indicated that the two higher PolybHb concentrations better restored coronary O2 delivery compared with the low concentration evaluated. Markers of organ damage and inflammation were highest for PHB10, whereas PHB5 and PHB2.5 showed similar expression of these markers. These studies indicate that a concentration of ~5 g/dL of PolybHb may be near the optimal concentration to restore cardiac function, preserve organ function, and mitigate the toxicity of PolybHb during resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Large-molecular diameter polymerized bovine hemoglobin avoided vasoconstriction and impairment of cardiac function during resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock that was seen with previous hemoglobin-based O2 carriers by increasing blood viscosity in a concentration-dependent manner. Supplementation of O2-carrying capacity played a smaller role in maintaining cardiac function than increased blood and plasma viscosity.

Keywords: blood substitutes, blood viscosity, cardiac function, hemorrhagic shock, rheology

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhage is the leading cause of potentially salvageable trauma-related deaths (17). In conjunction with hemostasis, survival of severe hemorrhage requires the restoration of blood volume (BV) to ensure proper cardiac function and tissue perfusion, which reinstates oxygen (O2) delivery (Do2) to tissues. Current fluid resuscitation strategies for class IV hemorrhages (any hemorrhage where >40% of blood volume is lost) are aggressive, necessitating implementation of a massive transfusion protocol (MTP; 1). MTP end points consider both physiological and laboratory criteria [mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and total hemoglobin (Hb) concentration] to minimize the volume transfused (2). Currently, patients are exposed to blood products from multiple donors due to blood component therapy and the large volume infused during MTP, increasing the risk of disease transmission and transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM; 28, 28a). Aggressive transfusion of crystalloids can cause fluid overload, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), increasing morbidity and mortality (25, 30). Furthermore, crystalloids ineffectively restore microcirculatory blood flow after resuscitation from trauma and decrease blood O2-carrying capacity by diluting the remaining red blood cells (RBCs) in the circulation (9).

Under normal conditions, only 25% of the O2 delivered to tissues is extracted (19). During severe hemorrhagic shock (HS), regulatory mechanisms increase O2 extraction (V̇o2) and prioritize oxygenation of vital organs by redistributing blood flow to these tissues. As HS reduces O2-carrying capacity and cardiac output (CO), limited O2 delivery compromises tissue oxygenation. The primary determinant of O2 delivery is the total Hb concentration in the blood; if total Hb falls below a critical total Hb concentration, known as the “transfusion trigger,” then tissue O2 demands will likely exceed O2 delivery, which indicates that a blood transfusion is needed (1). Typically, in healthy subjects, the transfusion trigger is equal to a total Hb concentration of 7 g/dL or less, but more liberal transfusion triggers are applied to actively bleeding subjects (15, 20, 27). Limited infusion of crystalloids is recommended (14a), but when blood is not available, crystalloids are infused more freely to restore BV and maintain blood pressure and blood flow, at the cost of diluting the remaining RBCs in the circulation. Diluted blood has low O2-carrying capacity and low blood viscosity, which prevents the restoration of microvascular blood flow during resuscitation from HS (7). Therefore, supplementing O2-carrying capacity and restoring blood viscosity during fluid resuscitation are essential to improve recovery and overall survival. Prehospital RBC transfusion in subjects suffering from hemorrhage improves survival compared with prehospital crystalloid infusion, emphasizing the importance of rapid restoration of O2-carrying capacity and blood viscosity (18). One method to restore O2-carrying capacity and blood viscosity with minimal logistical constraints compared with blood is to use Hb-based O2 carriers (HBOCs), specifically large-molecular diameter and high-viscosity HBOCs.

HBOCs have been proposed as alternatives to blood, when blood is not available or logistic constraints limit blood availability, such as on the battlefield and in emergency scenarios. HBOCs are not limited by blood type compatibility, they are nonimmunogenic, and they can be easily stored for long periods under ambient environmental conditions without degradation of O2-carrying capacity or other biophysical properties, whereas blood degrades in days under similar conditions. Previous small-molecular diameter HBOCs caused significant side effects upon transfusion that prevented their clinical acceptance. A new generation of HBOCs, based on polymerized Hb (PolyHb) with significantly larger molecular diameter, have shown promising results (5). Preclinical testing of the larger-molecular diameter PolyHb suggests that these PolyHbs prevent the side effects observed with small-molecular diameter HBOCs (14).

Additionally, the larger-molecular diameter PolyHbs have high viscosity, which improves microvascular perfusion after hemorrhagic shock via endothelial mechanotransduction and the production of endothelial-derived nitric oxide (NO; 10, 11). By increasing O2-carrying capacity and restoring blood viscosity, larger-molecular diameter PolyHbs recover microvascular blood flow and tissue oxygenation (14, 24, 34). The objective of this study was to examine the balance between O2-carrying capacity and blood viscosity on resuscitation from HS with large-molecular diameter PolyHbs. To achieve this objective, rats were subjected to a severe hemorrhage, followed by a hypovolemic shock, and resuscitated following the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines, which recommend maintenance of hemodynamic stability during resuscitation to a set blood pressure (1). In this study, rats were resuscitated with large-molecular diameter polymerized bovine Hb (PolybHb) at different concentrations. The animals’ hemodynamics, cardiac function, and blood chemistry were monitored during the protocol, and heme and iron metabolism, markers of stress, organ function, and organ damage were studied at the end of the protocol.

METHODS

Synthesis of PolybHb.

PolybHb was synthesized in the low-O2 affinity [tense (T)] quaternary state at a 35:1 molar ratio of glutaraldehyde to bovine Hb, filtered through a 0.2-µm tangential flow filtration (TFF) module to remove molecules larger than 0.2 µm in size, and then subjected to diafiltration on a 500-kDa TFF module using a modified lactated Ringer solution to remove molecules <500 kDa in size as previously described in the literature (34). PolybHb concentration was adjusted to 10 g/dL, and PolybHb was frozen and stored at −80°C until use. The 35:1 T-state PolybHb used in this study had the following biophysical properties: methemoglobin (metHb) level, 3.6%; P50 (Po2 at which Hb is 50% saturated with O2), 35 mmHg; cooperativity coefficient, 1; hydrodynamic diameter, 69 nm; and viscosity, 12.4 cP.

Viscosity and colloid osmotic pressure of PolybHb.

PolybHb viscosity was measured using a computerized cone-plate rheometer at 37°C (Discovery HR-2; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). Colloidal osmotic pressure (COP) was measured using a 30-kDa cutoff filter at 22°C (colloid osmometer model 4420; Wescor, Logan, UT).

Animal preparation.

Studies were performed in male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN), weighing 200–250 g. Animal handling and care followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of California San Diego, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (Drägerwerk AG, Lübeck, Germany) in room air and instrumented with a left femoral artery and a left jugular vein catheter and a left ventricular (LV) pressure-volume (P-V) conductance catheter introduced through the right carotid artery. The LV P-V measurements were completed using the closed-chest method as previously described (23). Animals were placed on a heating pad at 37°C in the supine position and allowed to freely breathe from a nose cone delivering anesthesia. After surgical preparation, anesthesia was reduced and constantly monitored to decrease isoflurane cardiosuppression.

Inclusion criteria.

Animals were suitable for experiments if 1) MAP was >85 mmHg at baseline, 2) stroke volume (SV) was >90 µL at baseline, 3) systemic Hb was >12 g/dL at baseline, and 4) animals survived the shock period. Additionally, the Grubbs’ method was used to assess closeness for all measured parameters at baseline and shock. Animals that were statistically significantly different from others at baseline or shock were replicated to maintain the per-group number of animals.

Cardiac function.

A 2-F conductance catheter (SPR-858; Millar Instruments, TX) was used to monitor LV P-V loops. Pressure and volume signals were acquired continuously (MPVS300, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX; and PowerLab 8/30, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). LV volume was measured in conductance units [relative volume units (RVUs)] and converted to absolute blood volume at the end of the experiment using calibrated cuvettes and blood collected from the experiment. Parallel LV volume was calibrated via intravenous injection of 40 µL of 15% (wt/vol) NaCl (23). Indexes of cardiac function and O2 delivery were calculated as previously described (33).

Systemic hemodynamic parameters.

MAP and heart rate (HR) were recorded continuously from the femoral artery (PowerLab 8/30; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Hematocrit (Hct) was measured via centrifugation from arterial blood collected into heparinized capillary tubes. Total and plasma Hb content was measured spectrophotometrically (B-Hemoglobin; HemoCue, Stockholm, Sweden). Arterial and venous blood samples were collected in heparinized glass capillary tubes (65 µL) and immediately analyzed for pH and partial pressures of O2 and carbon dioxide (Po2, and Pco2, Siemens 248; Siemens, Munich, Germany).

Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation protocol.

Animals were allowed to rest for 30 min after surgical instrumentation before baseline measurements were taken. Anesthetized rats were then hemorrhaged by withdrawing 50% of the animal’s blood volume (BV, estimated as 7% of body weight), via the femoral catheter over 30 min. Hypovolemia was maintained for 30 min, and no additional blood was removed during this period. Resuscitation was implemented by infusion of room temperature PolybHb through the jugular vein catheter using a syringe pump at a flow of 300 µL/min, until the animal recovered to 90% of its baseline MAP. If the animal’s MAP fell below 80% of its MAP at baseline, additional PolybHb was infused. This resuscitation phase lasted for 1 h. The volume transfused was calculated on the basis of the time the syringe pump was infusing test solutions. The percent resuscitation was calculated as the ratio of the volume infused relative to the animal’s total BV.

Experimental groups.

Following HS, rats were randomly resuscitated with PolybHb at 10, 5, or 2.5 g/dL. PolybHb was diluted to 5 and 2.5 g/dL with the modified lactated Ringer solution that was used during generation of the 10 g/dL stock solution, described previously in the literature (34). PolybHb concentrations were measured using a B-Hemoglobin (HemoCue). Biophysical properties of 10, 5, and 2.5 g/dL PolybHb are presented in Table 1. Twenty-one (n = 21) animals were entered into the HS-resuscitation study. Animals were randomly assigned to the following groups based on the concentration of PolybHb transfused during resuscitation: PHB10 (PolybHb concentration, 10 g/dL; n = 7), PHB5 (PolybHb concentration, 5 g/dL; n = 7), and PHB2.5 (PolybHb concentration, 2.5 g/dL; n = 7).

Table 1.

Biophysical properties of PolybHb and blood following the hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation protocol

| Infusion Solution Parameters |

Blood Parameters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolybHb viscosity, cP | PolybHb COP, mmHg | Whole blood viscosity, cP | Plasma viscosity, cP | |

| Baseline | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.08 ± 0.02 | ||

| Shock | 2.8 ± 0.1* | 0.96 ± 0.01 | ||

| PHB2.5 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1* | 1.38 ± 0.04*§ |

| PHB5 | 3.8 ± 0.1† | 1.5 ± 0.1† | 2.8 ± 0.1* | 1.66 ± 0.03*§† |

| PHB10 | 11.4 ± 0.3†‡ | 5.6 ± 0.2†‡ | 3.4 ± 0.1§†‡ | 2.19 ± 0.07*§†‡ |

Values are means ± SE. Polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) viscosity and colloidal osmotic pressure (COP) were measured in quadruplicate; blood viscosity, plasma viscosity, and COP were measured in n = 4 animals. Baseline and shock viscosity measurements were taken from blood drawn during the hemorrhage. Viscosity was measured at 316 s−1 at 37°C; COP was measured at 22°C.

P < 0.05 vs. Baseline;

P < 0.05 vs. Shock;

P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5;

P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

Markers of organ function, damage, and inflammation.

Aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), IL-6, IL-10, and bilirubin levels were determined in serum samples using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (KA1625 and KT-6104, Abnova Corp., Taiwan; BMS625 and BMS629, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA; ab235627, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) was determined in the urine using an ELISA kit (ERLCN2; Thermo Fisher). Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were measured using colorimetric detection kits (KB02-H2 and K024-H5; Arbor Assays Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). Liver, lung, and spleen chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) were measured on whole tissue homogenates by ELISA (ERCXCL1; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and corrected for protein concentration using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Thermo Fisher). Positive CD45 neutrophils were quantified in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid collected by instilling sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the lung. The percentage fraction of neutrophils in BAL fluid was determined by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Neutrophils were identified by their typical appearance in the forward/side scatter and their expression of CD45 (554875; BD Biosciences). Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was determined from lung tissue homogenates by ELISA (E4581; Biovision, Milpitas, CA).

Preparation and immunoprecipitation of rat tissue extracts for ferritin.

Rat tissues were frozen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Lysis buffer containing 1% deionized Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium azide in 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5, with Chelex 100 and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (0.25 mM) was added to the homogenized tissue, which was vortexed, sonicated for 1 min, and incubated on ice for 30 min, vortexing every 5–10 min. Aliquots were taken, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was analyzed for total protein (BCA, Pierce) and ferritin. The remaining suspension of homogenized tissue was incubated at 70°C for 10 min, cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was discarded. The total amount of ferritin in each extract was calculated using the results of an ELISA kit (cat. no. MCA-155; Serotec, Oxford, UK). Saturating amounts of immune serum against rat tissue ferritin were then added to the extracts.

Epinephrine/norepinephrine.

Catecholamine plasma concentrations were determined using commercially available ELISA kits for catecholamines (Catecholamines ELISA kit, ref. no. BA-E-6600; ImmuSmol, France). All ELISA samples were run in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE, or as box-and-whisker plots. The values are presented as absolute values and relative to the baseline. A ratio of 1.0 signifies no change from baseline, whereas lower or higher ratios are indicative of changes proportionally lower or higher compared with baseline, respectively. Before experiments were initiated, sample size was determined on the basis of power calculations using α = 0.05 and a power of 1 − β = 0.9 to detect differences in primary end points (MAP, contractility, and %resuscitation) >10%. Statistically significant changes between solutions and time points were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc analyses using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test when appropriate. All statistics were calculated using the Python Library StatsModels (version 0.9.0; 26). Results were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Biophysical properties of PolybHb.

Viscosity and COP of PolybHb were both highly concentration dependent, as described in Table 1. Dilution of PolybHb from 10 g/dL to 5 g/dL substantially decreased viscosity, but additional dilution to 2.5 g/dL had a smaller impact on viscosity. COP decreased with a trend similar to that of viscosity.

Systemic hemodynamics.

All animals survived the entire experimental protocol, and there were no statistically significant differences between groups at baseline or shock. All animals had similar blood pressure at baseline and at the end of shock (Fig. 1A). Blood pressure was restored similarly for all groups 10 min into resuscitation, but 60 min after resuscitation only PHB10 and PHB5 remained within the blood pressure target, whereas PHB2.5’s blood pressure was below the target range (76% of baseline), despite continued infusion of PHB2.5. However, all groups were significantly improved from shock. Shock induced bradycardia for all groups, and heart rate did not recover for any groups during resuscitation (Fig. 1B). CO slightly decreased from baseline during shock and was not restored to baseline levels after transfusion; however, CO recovered proportionally to PolybHb concentration (Fig. 2A). Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) did not significantly change from baseline during shock, but trended slightly higher. SVR further increased during resuscitation, but these changes were still not statistically significant from baseline (Fig. 2B). During resuscitation, however, systemic vascular hinderance (SVH), the contribution of blood vessel diameter to SVR, or the SVR independent of blood viscosity, decreased proportional to the concentration of PolybHb. This indicates that vasoconstriction was inversely proportional to PolybHb concentration infused and circulating in the plasma (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

High concentration of polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) sustains central hemodynamics compared with low concentration. A: mean arterial pressure (MAP) decreases during shock and is partially recovered during resuscitation. B: heart rate (HR) decreases during shock and does not fully recover in the 1-h resuscitation. Here, n = 7 animals per group. BL, Baseline; bpm, beats/min; PHB2.5, PHB5, and PHB10, 2.5, 5, and 10 g/dL PolybHb, respectively; R10 and R60, 10 and 60 min after beginning of resuscitation, respectively; SH, Shock. *P < 0.05 vs. Baseline.

Fig. 2.

Central hemodynamics following transfusion of high-concentration polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb). A: cardiac output (CO) recovers close to baseline values following 10 g/dL PolybHb (PHB10) transfusion. Average baseline CO was 69.5 mL/min. B: systemic vascular resistance (SVR) increases following resuscitation. Average baseline SVR was 11,000 dyn·s·cm−5. C: the high viscosity of PHB10 decreases systemic vascular hinderance (SVH) compared with 2.5 g/dL PolybHb (PHB2.5). Here, n = 7 animals per group. BL, Baseline; PHB5, 5 g/dL PolybHb; R10 and R60, 10 and 60 min after beginning of resuscitation, respectively; SH, Shock.

Cardiac mechanoenergetics.

Cardiac indexes depicting the relationship between O2 consumption and mechanical work of the left ventricle myocardium [such as stroke work (SW), the work performed per volume ejected (SW/SV), and internal energy utilization (IEU)], are presented in Fig. 3. Shock significantly impaired IEU and SW/SV, and during resuscitation, cardiac mechanoenergetics were recovered depending on the concentration of PolybHb transfused. SW was restored to baseline for all groups by the end of the protocol but followed a concentration-dependent trend (Fig. 3A). The energy required to eject an equivalent volume of blood (SW/SV) increased during resuscitation for all groups (Fig. 3B), but SW/SV was lower for PHB2.5 compared with PHB10. Furthermore, SW/SV was also significantly higher for PHB10 at the end of resuscitation than during shock, whereas it was not significantly different between those time points for the other groups. Late into the resuscitation, PHB10 and PHB5 both maintained SW/SV at baseline levels, but SW/SV decreased for PHB2.5. IEU, a measure of the heart’s metabolism, recovered to baseline values and was significantly higher during resuscitation than during shock for PHB10 and PHB5, but IEU never recovered for PHB2.5 (Fig. 3C). Additionally, PHB2.5 had significantly lower IEU compared with PHB10 throughout resuscitation.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac mechanoenergetics following polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) transfusion. A: stroke work (SW) recovers to baseline levels. Average baseline SW was 17,637 mmHg·µL. B: stroke work per volume ejected (SW/SV) is elevated with 10 and 5 g/dL PolybHb (PHB10 and PHB5, respectively), indicating better recovery of cardiac function and more pressure generation. Average baseline SW/SV was 101 mmHg. C: internal energy utilization (IEU) of the heart, an indicator of the heart’s potential energy, is increased after transfusion of PHB10 relative to 2.5 g/dL PolybHb (PHB2.5). Average baseline IEU was 8,619 mmHg·µL. Here, n = 7 animals per group. BL, Baseline; R10 and R60, 10 and 60 min after beginning of resuscitation, respectively; SH, Shock. *P < 0.05 vs. Baseline, †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5.

Hematology.

A summary of hematological changes is given in Table 2. To achieve and maintain the blood pressure goal, significantly more PHB2.5 was transfused than PHB10 and PHB5 (Fig. 4). Despite the different volumes given to all groups, hematocrit between the groups was similar at all time points. The total and plasma Hb was significantly higher for PHB10 compared with PHB5 and with PHB2.5, because of the higher concentration of PolybHb infused. Resuscitation with PHB10 and PHB5 resulted in a significantly higher blood and plasma viscosity compared with PHB2.5 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Hematological parameters during the protocol

| Baseline | Shock | Resuscitation 10 min |

Resuscitation 60 min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 g/dL | 5 g/dL | 10 g/dL | 2.5 g/dL | 5 g/dL | 10 g/dL | |||

| Hct, % | 43 ± 1 | 28 ± 1* | 26 ± 1* | 27 ± 1* | 26 ± 1* | 22 ± 1* | 22 ± 1* | 20 ± 1*†‡ |

| Total Hb, g/dL | 13.6 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1* | 9.0 ± 0.2* | 9.5 ± 0.1* | 9.7 ± 0.2* | 8.9 ± 0.2* | 9.5 ± 0.1* | 10.6 ± 0.2*†‡ |

| Plasma Hb, g/dL | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2† | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.3† | 5.2 ± 0.4†‡ | ||

Values are means ± SE; n = 7 animals per group. Plasma Hb data are not compared with baseline.

P < 0.05 vs. Baseline;

P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5;

P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

Fig. 4.

Volume requirements to resuscitate rats from hemorrhagic shock, as percentage of total blood volume (BV). Significantly higher volume of polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) at 2.5 g/dL concentration (PHB2.5) is required to reach the mean arterial pressure target. Total blood volume is estimated as 7% of the animal’s body weight. Here, n = 7 animals per group. PHB5 and PHB10, 5 and 10 g/dL PolybHb, respectively; R10, R20, R30, R45, and R60, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min after beginning of resuscitation, respectively. †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5.

Blood chemistry.

HS induced acidosis, increased arterial Po2, and decreased arterial Pco2 compared with baseline (Table 3). Acidosis was not fully resolved by resuscitation with any of the PolybHb concentrations. The base excess, which describes the acid-base balance, significantly decreased during shock. Acid-base balance never fully recovered to baseline, and all groups remained slightly acidic during resuscitation.

Table 3.

Blood gases recover to near baseline values for all groups

| Baseline | Shock | Resuscitation 10 min |

Resuscitation 60 min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 g/dL | 5 g/dL | 10 g/dL | 2.5 g/dL | 5 g/dL | 10 g/dL | |||

| pH | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.29 ± 0.01* | 7.28 ± 0.01* | 7.32 ± 0.02* | 7.33 ± 0.01* | 7.33 ± 0.01* | 7.35 ± 0.01* | 7.33 ± 0.01* |

| Pco2, mmHg | 42.8 ± 1.1 | 36.4 ± 0.8* | 38.7 ± 0.8 | 40.4 ± 2.2 | 38.1 ± 1.2 | 42.4 ± 1.5 | 42.9 ± 1.9 | 43.0 ± 1.1 |

| Po2, mmHg | 86 ± 2 | 110 ± 2* | 98 ± 4 | 103 ± 5 | 98 ± 4 | 82 ± 5 | 91 ± 5 | 85 ± 6 |

| Base excess | 1.9 ± 0.3 | −8.4 ± 0.6* | −8.1 ± 0.9* | −5.4 ± 0.9* | −6.8 ± 0.7* | −3.3 ± 1.0* | −1.9 ± 0.7* | −3.2 ± 0.8* |

Values are means ± SE; n = 7 animals per group.

P < 0.05 vs. Baseline.

O2 delivery and extraction.

O2 delivery (Do2) decreased during shock and did not fully recover during resuscitation (Fig. 5A). There were no significant differences in Do2 between groups. Late into resuscitation, Do2 was highest for PHB10 and was approximately 1.24 times and 1.31 times greater than Do2 for PHB5 and PHB2.5, respectively. Animals maintained a similar degree of O2 extraction (V̇o2) throughout the experiment, but V̇o2 remained higher for PHB10 after resuscitation, whereas V̇o2 decreased slightly for PHB5 and PHB2.5 during resuscitation (Fig. 5B). All groups had very similar V̇o2-to-Do2 ratios, indicating that the low-affinity PolybHb facilitates O2 off-loading independently of the concentration of PolybHb (Fig. 5C). When broken down into the O2-carrying components (RBCs and PolybHb), the Do2 and V̇o2 by PolybHb were determined by the plasma concentration of PolybHb (Fig. 5, D–I). However, a significantly higher fraction of the total O2 extracted was derived from RBCs compared with PolybHb, and the ratio of V̇o2 to Do2 was significantly higher for RBCs than for PolybHb, suggesting that PolybHb acts as an intermediary of O2 off-loading to tissues.

Fig. 5.

Parameters of O2 transport. Rows represent the O2 transported by different elements of the blood, and each column represents a different parameter of oxygen transport. A–C: O2 transported by the whole blood. D–F: O2 transported by the red blood cells (RBCs). G–I: O2 transported by the polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb). Here, n = 7 animals per group. BL, Baseline; PHB2.5, PHB5, and PHB10, 2.5, 5, and 10 g/dL PolybHb, respectively; PolyHb, polymerized hemoglobin; R10 and R60, 10 and 60 min after beginning of resuscitation, respectively; SH, Shock. *P < 0.05 vs. Baseline, †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5, ‡P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

Markers of organ function, damage, and inflammation.

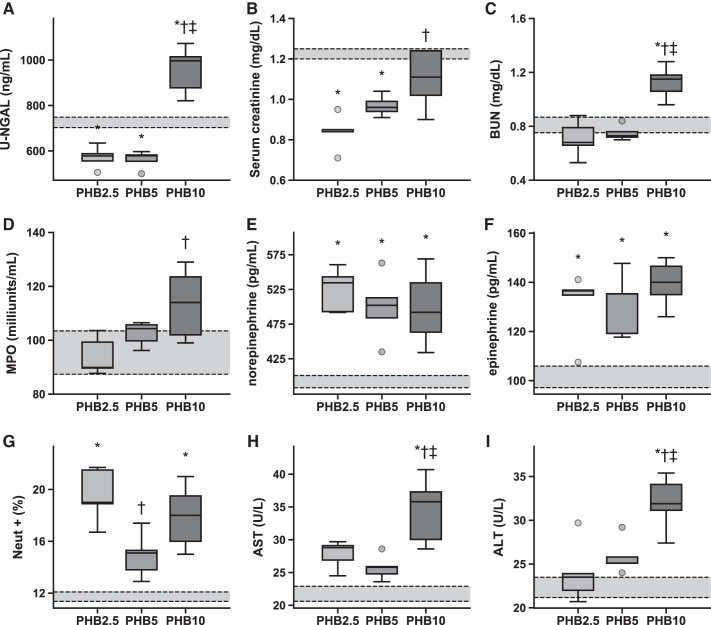

In general, markers of vital organ damage and inflammation increased with the concentration of PolybHb infused during resuscitation (Fig. 6). A marker of acute kidney damage [urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (u-NGAL)] was significantly higher for PHB10 compared with PHB5 and PHB2.5, as were molecules normally cleared by the kidneys, such as serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Similarly, liver enzymes associated with liver damage, such as aspartate and alanine aminotransferases, showed higher plasma concentrations for PHB10 compared with PHB5 and PHB2.5. Catecholamine levels were similar for all groups. Markers of systemic and lung inflammation decreased with PolybHb concentration. Systemic inflammatory markers decreased with the concentration of PolybHb transfused (Fig. 7). Inflammatory markers of organs in the reticuloendothelial system were similar for PHB10 and PHB2.5 and were significantly higher than for PHB5. Markers of iron transport postresuscitation all increased in a PolybHb concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8), as expected.

Fig. 6.

Markers of organ damage and function. A–C: kidney markers. D and G: lung markers. E and F: systemic markers. H and I: liver markers. Here, n = 7 animals per group. The average ± SE of these markers in unbled sham animals (n = 4) is indicated by the gray box surrounded with black dashed lines. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Neut +, positive CD45 neutrophils; PHB2.5, PHB5, and PHB10, 2.5, 5, and 10 g/dL polymerized bovine hemoglobin, respectively; u-NGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham, †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5, ‡P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

Fig. 7.

Markers of organ neutrophil recruitment and inflammation. A: neutrophil recruitment in lungs is dependent on the polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) concentration transfused. B–D: neutrophil recruitment in the spleen, in the liver, and systemically appears lowest for 5 g/dL PolybHb (PHB5). E and F: the inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses appear to be equal and PolybHb concentration dependent. Here, n = 7 animals per group. The average ± SE of these markers in unbled sham animals (n = 4) is indicated by the gray box surrounded with black dashed lines. PHB2.5 and PHB10, 2.5 and 10 g/dL PolybHb, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham, †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5, ‡P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

Fig. 8.

Markers of iron transport. A: plasma iron transport appears to be independent of the polymerized bovine hemoglobin (PolybHb) concentration transfused. B–E: markers of iron transport in the liver and spleen are dependent on the concentration of PolybHb transfused. F: heme metabolism is dependent on the concentration of PolybHb transfused. Here, n = 7 animals per group. The average ± SE of these markers in unbled sham animals (n = 4) is indicated by the gray box surrounded with black dashed lines. PHB2.5, PHB5, and PHB10, 2.5, 5, and 10 g/dL PolybHb, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham, †P < 0.05 vs. PHB2.5, ‡P < 0.05 vs. PHB5.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of this study is that resuscitation from HS with high concentrations of PolybHb (PHB10 and PHB5) restored cardiac function and O2 delivery in a manner superior to that of the low concentration of PolybHb (PHB2.5). PolybHb improved CO, SW, and the heart’s IEU as a function of the Hb concentration. Markers of organ function, organ damage, and inflammation, in general, also changed proportionally to the concentration of PolybHb. Therefore, the outcome of resuscitation from HS appears to be dependent on PolybHb concentration. These results demonstrate that higher concentrations of PolybHb are effective in recovering intravascular volume, as a lower transfusion volume was necessary to restore MAP and cardiac function with PHB10. The low concentration of PolybHb (PHB2.5) had low intravascular retention, as confirmed by the larger transfusion volume needed to resuscitate compared with PHB10 and PHB5 and their similar final hematocrit levels after resuscitation. As the main differences between the resuscitation fluids were their O2-carrying capacity and viscosity, the physiological mechanisms related to these two properties likely determined the recovery from HS.

The recovery of cardiac function in this study was proportional to PolybHb solution viscosity. Resuscitation from HS with high-viscosity solutions improves the recovery of microvascular function (11). Research focused on the microcirculation has shown that restoration of microvascular perfusion is more effective than recovery of O2-carrying capacity in restoring tissue oxygenation (8). This research has also demonstrated that recovery of systemic markers such as blood pressure, O2 saturation, or lactic acid concentration during resuscitation from HS is not indicative of effective tissue oxygenation, nor are they strong markers of focal ischemia or predictors of future multiorgan failure (6). Transfusion of PHB10 and PHB5 provided an increase of 58% and 20% in plasma viscosity relative to resuscitation with PHB2.5. The differences in viscosity may account for some of the differences observed in cardiac function, vascular hinderance, and the total volume transfused. In addition, differences in viscosity induced by PolybHb also affect the shear stress exerted by flowing blood on vascular endothelial cells, which influences vessel diameter and modulates the release of vasodilatory autacoids (prostacyclin and NO). Given the heart’s high metabolism, restoration and maintenance of coronary perfusion are essential to ensure cardiac function. The coronary microcirculation, much like the systemic microcirculation, is highly sensitive to endothelial shear stress resulting from blood flow (29); thus NO-mediated coronary vasodilation is then likely to have increased with PHB5 and PHB10, improving cardiac perfusion and O2 delivery. Although systemic arterioles are traditionally deemed to be the main regulators of systemic vascular resistance because of their smooth muscle-mediated vasomotion, large arteries also have significant amounts of smooth muscle that regulates their stiffness through vasoactive NO mechanisms (32). PHB10 and PHB5 also provided a 30% and 7% increase in whole blood viscosity relative to PHB2.5, respectively. Although microvascular wall shear stress is primarily determined by plasma viscosity, whole blood viscosity plays a larger role than plasma viscosity in the NO-regulated vasoactive mechanisms of large arteries because of the Poiseuille flow regime that decreases the contribution of the cell-free lubrication layer to wall shear stress. The changes in whole blood viscosity produced by the infusion of PHB10 and PHB5 compared with PHB2.5 (Table 1) increase shear stress in large systemic vessels, decreasing arterial stiffness, which has been shown to improve coronary blood flow (31). Combined, these viscosity-driven mechanisms decrease afterload and increase coronary O2 availability, which helps to recover CO (22).

Although traditional resuscitation fluids increase BV, they also reduce the total O2-carrying capacity of blood, whereas PolybHb increases BV and total O2-carrying capacity simultaneously, which helps sustain tissue oxygenation. As blood flow is restored to peripheral tissues during resuscitation, O2 demand increases, and the heart is challenged to perform more work. In these experiments, total O2 delivery was proportional to the concentration of PolybHb transfused. During shock, acidosis results in a rightward shift of the Hb-O2 affinity curve, thus favoring O2 extraction. The low O2 affinity of PolybHb and its presence in solution in plasma further enhance tissue O2 delivery and extraction. The low Hb-O2 affinity of PolybHb allows for facilitated release of O2 from the RBCs and brings the PolybHb-bound O2 closer to the tissue, which causes a steeper O2 gradient between blood and tissues, thus increasing the O2 flux leaving the microcirculation. This enhanced O2 extraction behavior is demonstrated with the sustained rise in V̇o2-to-Do2 ratio following resuscitation with PolybHb. Furthermore, PolybHb clearly facilitates the transfer of O2 from RBCs to the tissues. At the end of resuscitation, the PolybHb in the PHB10 group accounts for 34% of the total Do2 but only 23% of the total V̇o2 (V̇o2-to-Do2 ratio, 32%). A similar trend is observed with PHB5 and PHB2.5, where only 28% and 30%, respectively, of the O2 delivered by the PolybHb is actually off-loaded. A much higher percentage of the O2 is extracted from the RBCs, where a total of 62%, 48%, and 56% of O2 delivered by the RBCs is extracted for PHB10, PHB5, and PHB2.5, respectively. Therefore, PolybHb acts as an intermediary O2-carrying species, promoting the off-loading of O2 to tissues, apparently independent of concentration. However, the increase in total O2-carrying capacity achieved by transfusion of PolybHb appears to be less critical than the facilitated O2 off-loading and the increased viscosity, as animals still had a significant reserve of O2 available for delivery, as indicated by the V̇o2-to-Do2 ratio.

Restoration of cardiac function is critical in ensuring proper O2 delivery to peripheral tissues during resuscitation from HS. Catecholamines released during shock redistribute blood flow from peripheral tissues to vital tissues, such as the heart and brain, to sustain their metabolism (16). Thus, the heart must generate pressure to overcome vasoconstriction and restore capillary perfusion pressure to prevent hypoxia and the accumulation of by-products of anaerobic metabolism of peripheral tissues. The restoration of capillary perfusion pressure following HS depends on a number of factors that are all significantly affected by blood viscosity (8). The heart must overcome cardiac afterload and generate flow (CO) to exceed the metabolic demands of perfused tissues. In these experiments, CO recovered in proportion to the concentration of PolybHb infused, with no improvement in CO from shock for PHB2.5. The CO, and the viscosity of the blood, generate shear stress on the vascular wall, which regulates SVR. Whereas SVR was not different between groups, SVH was significantly higher for PHB10 than for PHB2.5; since PHB2.5 did not improve CO or increase viscosity, it is unlikely that SVH improved significantly from shock for this group. It was previously demonstrated in a hamster window chamber model that capillary perfusion pressure is primarily dependent on microvascular diameter (reported by SVH), not the viscosity of the solution (8). As such, SVH is a sensitive indicator of capillary perfusion pressure and thus microvascular O2 delivery. Indeed, cardiac mechanoenergetic parameters (SW, SW/SV, and IEU; Fig. 3) suggest an increase in cardiac O2 consumption for PHB10 and PHB5 compared with PHB2.5; these changes in cardiac O2 consumption are satisfied by the changes in coronary O2 delivery, as there were no significant differences in base excess between experimental groups. These data suggest that PHB10 and PHB5 improve cardiac function following resuscitation from HS.

The O2 delivery, plasma viscosity, and COP appear to be more important than the total volume infused during fluid resuscitation in terms of recovering pressure, cardiac function, and blood flow (Fig. 4). The volume requirements of PHB10 and PHB5 were significantly lower than that of PHB2.5, but they increased the total Hb concentration and plasma viscosity compared with PHB2.5. The ability to restore proper tissue blood flow and cardiac function at lower infusion volumes is extremely beneficial, as it limits the potential toxicity of PolybHb. In fact, transfusion of PHB2.5 could prove deleterious compared with PHB5 and PHB10 as the large resuscitation volume needed dilutes native O2-carrying capacity and can induce acute respiratory distress syndrome and edema. Additionally, lack of proper tissue perfusion resulting from the use of PHB2.5 could lead to downstream consequences, such as ischemia and multiorgan failure. The low COP of PHB2.5 likely contributed to the large transfusion volume required to recover from shock, since ~23% of the PHB2.5 that was transfused was removed from the circulation (based on difference in the theoretical hematocrit following transfusion and the measured hematocrit), statistically significantly more than the 6% and 4% that were removed by PHB5 and PHB10, respectively. Finally, large-volume infusions during resuscitation result in renal dysfunction (21) and increase the likelihood of systemic or pulmonary edema, resulting in further complications following resuscitation from HS.

In this study, some markers of kidney function (serum creatinine and BUN) indicate that PolybHb suppressed kidney function, whereas other markers indicate that PolybHb resulted in acute liver injury (ALT), acute inflammation (lung CXCL1, IL-6, and IL-10), and altered iron transport (liver L-ferritin, spleen L- and H-ferritin, and total bilirubin), in a concentration-dependent manner. Other markers of kidney (u-NGAL) and liver injury (AST), as well as markers of inflammation (spleen and liver CXCL1), did not demonstrate a clear concentration dependence. In fact, for markers that did not demonstrate a concentration dependence, these markers showed the lowest level in the PHB5 group. Furthermore, for markers that did show a concentration-dependent relationship, PHB2.5 and PHB5 expressed very similar levels of markers, often with PHB5 only showing marginally higher markers and PHB10 showing substantially higher markers. This could be an important consideration when deciding the dosage of PolybHb. However, markers of acute organ injury in this study were primarily driven by transfusion-associated toxicities, as the timescale of the study is too short to examine secondary injury caused by the different degrees of recovery experienced by the groups. On the basis of these data and the cardiac function data presented earlier, we conclude that the intermediate concentration of PolybHb (PHB5) seems to be optimal to restore cardiac function and hemodynamics to a degree comparable to that of PHB10, with similar transfused volume and with lower levels of tissue inflammatory markers and less acute tissue toxicity compared with PHB10.

Previous studies with small-molecular diameter HBOCs demonstrated deleterious changes in both the heart and microvasculature following the transfusion of high concentrations of HBOCs (3, 12, 13). These studies found that a moderate dosage of HBOCs resulted in fewer complications, as animals experienced dose-dependent vasoconstriction that limited O2 delivery and increased left ventricular afterload. Previous HBOCs contained >1% nonpolymerized Hb and possessed significantly lower average molecular diameters than the PolybHb tested in this study. The differences between our study and previous studies are likely due to the drastically different biophysical properties of previous HBOCs and the new, large molecular diameter PolybHb evaluated in this study, in addition to the removal of most of the low-molecular diameter PolybHb molecules by diafiltration on a 500-kDa TFF module. The molecular size and purity of PolybHb prevent tissue extravasation, separate PolybHb from the vascular endothelium via steric hindrance, and, finally, increase plasma viscosity. Large-molecular diameter PolybHb results in a more stable product with limited vascular smooth muscle NO consumption and increased endothelial mechanotransduction compared with previous HBOCs. The concentration-dependent increase of cardiac function observed in this study confirms that the large molecular size of PolybHb prevents vasoconstriction and hypertension. Furthermore, these data suggest that large-molecular diameter PolybHb could be transfused more liberally than previous HBOCs without passing from an ideal “therapeutic range” into a range where HBOC administration can be harmful.

Limitations.

Studies in rats cannot be directly translated to clinical scenarios, but these results suggest that high-viscosity O2 carriers improve resuscitation from HS. It is also difficult to independently assess the effects of viscosity and O2-carrying capacity following resuscitation with PolybHb. These two parameters are intrinsically linked, and modifications to the manufacturing process would ultimately result in a significantly different material, which could change the COP, vasoactivity, and/or parameters of O2 loading and off-loading. As this study was aimed at replicating ATLS guidelines, which suggest hypotonic resuscitation, differences in cardiac function between groups were not expected to be large. However, the significant differences in the volume transfused indicate the differences in efficacy between concentrations of PolybHb, and a mild dose dependence is apparent. Inverse to cardiac parameters, markers of acute organ damage suggest that low concentrations of PolybHb may be beneficial. Since this study was aimed at assessing the so-called “golden hour” of resuscitation, secondary organ injury resulting from insufficient resuscitation from HS was not examined and may provide more support for the use of PHB10 than did the acute parameters measured.

Conclusion.

This study demonstrated that PolybHb restores cardiac function and MAP in a concentration-dependent manner during resuscitation from HS. This concentration dependency was not seen in previous studies because of vasoactivity of previous HBOCs, which is significantly attenuated by the additional processing steps that result in a large-molecular diameter PolybHb. These processing steps also cause PolybHb to have high viscosity, which has been shown to be a critical determinant in restoration of microvascular perfusion during resuscitation from shock (11). Overall, the intermediate concentration of PolybHb evaluated restored cardiac function and hemodynamics to a degree comparable to that of the highest concentration and minimized tissue inflammation and injury associated with the higher PolybHb concentration. Thus, although the increased molecular size of PolybHb inhibits the pressor effects observed in previous-generation HBOCs, the molecular size does not eliminate the intrinsic toxicity of Hb-based products. Overall, large-molecular diameter PolybHb is a promising alternative to the transfusion of blood in austere environments, after mass casualty events when type O blood supply is insufficient, or where logistical constraints prevent the use of conventional blood transfusions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants T32-HL-105373, R01-HL-126945, and R01-HL-138116.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.T.W., A.F.P., and P.C. conceived and designed research; A.T.W. performed experiments; A.T.W., A.L., and C.R.M. analyzed data; A.T.W., A.L., C.R.M., and P.C. interpreted results of experiments; A.T.W. prepared figures; A.T.W., A.L., C.R.M., and P.C. drafted manuscript; A.T.W., A.L., C.R.M., C.B.-R., A.F.P., and P.C. edited and revised manuscript; A.T.W., A.L., C.R.M., C.B.-R., A.F.P., and P.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Cynthia Walser (University of California, San Diego) for surgical preparation of the animals and Joyce B. Li (University of California, San Diego) for assistance with illustrations.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) Student Course Manual (10th ed.). Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program ACS TQIP Massive Transfusion in Trauma Guidelines (Online). https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/transfusion_guildelines.ashx. 2014.

- 3.Ao-Ieong ES, Williams A, Jani V, Cabrales P. Cardiac function during resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock with polymerized bovine hemoglobin-based oxygen therapeutic. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 45: 686–693, 2017. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2016.1241797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buehler PW, Zhou Y, Cabrales P, Jia Y, Sun G, Harris DR, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M, Palmer AF. Synthesis, biophysical properties and pharmacokinetics of ultrahigh molecular weight tense and relaxed state polymerized bovine hemoglobins. Biomaterials 31: 3723–3735, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabrales P, Nacharaju P, Manjula BN, Tsai AG, Acharya SA, Intaglietta M. Early difference in tissue pH and microvascular hemodynamics in hemorrhagic shock resuscitation using polyethylene glycol-albumin- and hydroxyethyl starch-based plasma expanders. Shock 24: 66–73, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000167111.80753.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabrales P, Tsai AG. Plasma viscosity regulates systemic and microvascular perfusion during acute extreme anemic conditions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2445–H2452, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00394.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Microvascular pressure and functional capillary density in extreme hemodilution with low- and high-viscosity dextran and a low-viscosity Hb-based O2 carrier. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H363–H373, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01039.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Hyperosmotic-hyperoncotic versus hyperosmotic-hyperviscous: small volume resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. Shock 22: 431–437, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000140662.72907.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Is resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock limited by blood oxygen-carrying capacity or blood viscosity? Shock 27: 380–389, 2007. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239782.71516.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Increased plasma viscosity prolongs microhemodynamic conditions during small volume resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock. Resuscitation 77: 379–386, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Isovolemic exchange transfusion with increasing concentrations of low oxygen affinity hemoglobin solution limits oxygen delivery due to vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2212–H2218, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00751.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrales P, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M. Polymerized bovine hemoglobin can improve small-volume resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock in hamsters. Shock 31: 300–307, 2009. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180ff63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabrales P, Zhou Y, Harris DR, Palmer AF. Tissue oxygenation after exchange transfusion with ultrahigh-molecular-weight tense- and relaxed-state polymerized bovine hemoglobins. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1062–H1071, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01022.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Carson JL, Kleinman S. Indications and hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion in the adult. In: UpToDate, edited by Silvergleid AJ, Tirnauer JS. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson JL, Noveck H, Berlin JA, Gould SA. Mortality and morbidity in patients with very low postoperative Hb levels who decline blood transfusion. Transfusion 42: 812–818, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chernow B, Rainey TG, Lake CR. Endogenous and exogenous catecholamines in critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 10: 409–416, 1982. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198206000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geeraedts LM Jr, Kaasjager HA, van Vugt AB, Frölke JP. Exsanguination in trauma: a review of diagnostics and treatment options. Injury 40: 11–20, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyette FX, Sperry JL, Peitzman AB, Billiar TR, Daley BJ, Miller RS, Harbrecht BG, Claridge JA, Putnam T, Duane TM, Phelan HA, Brown JB. Prehospital blood product and crystalloid resuscitation in the severely injured patient: a secondary analysis of the prehospital air medical plasma trial. Ann Surg. In Press. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillman RS, Ault KA, Leporrier M, Rinder MH. Hematology in Clinical Practice (5th ed.). New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juneja D, Singh O, Dang R. Admission hyperlactatemia: causes, incidence, and impact on outcome of patients admitted in a general medical intensive care unit. J Crit Care 26: 316–320, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Rourke MF, Mancia G. Arterial stiffness. J Hypertens 17: 1–4, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 3: 1422–1434, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer AF, Zhang N, Zhou Y, Harris DR, Cabrales P. Small-volume resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock using high-molecular-weight tense-state polymerized hemoglobins. J Trauma 71: 798–807, 2011. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182028ab0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds PS, Barbee RW, Skaflen MD, Ward KR. Low-volume resuscitation cocktail extends survival after severe hemorrhagic shock. Shock 28: 45–52, 2007. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31802eb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seabold S, Perktold J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010) Austin, TX, June 28–30, 2010, p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shander A, Javidroozi M, Naqvi S, Aregbeyen O, Caylan M, Demir S, Juhl A. An update on mortality and morbidity in patients with very low postoperative hemoglobin levels who decline blood transfusion (CME). Transfusion 54: 2688–2695, 2014. doi: 10.1111/trf.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sihler KC, Napolitano LM. Complications of massive transfusion. Chest 137: 209–220, 2010. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Silvergleid AJ. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO). In: UpToDate, edited by Kleinman S, Tirnauer JS. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stepp DW, Nishikawa Y, Chilian WM. Regulation of shear stress in the canine coronary microcirculation. Circulation 100: 1555–1561, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.14.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern SA. Low-volume fluid resuscitation for presumed hemorrhagic shock: helpful or harmful? Curr Opin Crit Care 7: 422–430, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tritakis V, Tzortzis S, Ikonomidis I, Dima K, Pavlidis G, Trivilou P, Paraskevaidis I, Katsimaglis G, Parissis J, Lekakis J. Association of arterial stiffness with coronary flow reserve in revascularized coronary artery disease patients. World J Cardiol 8: 231–239, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson IB, Franklin SS, Cockcroft JR. Nitric oxide and the regulation of large artery stiffness: from physiology to pharmacology. Hypertension 44: 112–116, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000138068.03893.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams AT, Jani VP, Nemkov T, Lucas A, Yoshida T, Dunham A, D’Alessandro A, Cabrales P. Transfusion of anaerobically or conventionally stored blood after hemorrhagic shock. Shock 53: 352–362, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Jia Y, Buehler PW, Chen G, Cabrales P, Palmer AF. Synthesis, biophysical properties, and oxygenation potential of variable molecular weight glutaraldehyde-polymerized bovine hemoglobins with low and high oxygen affinity. Biotechnol Prog 27: 1172–1184, 2011. doi: 10.1002/btpr.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]