Abstract

Characterization of dynamic cerebral autoregulation has focused primarily on adjustments in cerebrovascular resistance in response to blood pressure (BP) alterations. However, the role of vascular compliance in dynamic autoregulatory processes remains elusive. The present study examined changes in cerebrovascular compliance and resistance during standing-induced transient BP reductions in nine young, healthy adults (3 women). Brachial artery BP (Finometer) and middle cerebral artery blood velocity (BV; Multigon) waveforms were collected. Beginning 20 beats before standing and continuing 40 beats after standing, individual BP and BV waveforms of every second heartbeat were extracted and input into a four-element modified Windkessel model to calculate indexes of cerebrovascular resistance (Ri) and compliance (Ci). Standing elicited a transient reduction in mean BP of 20 ± 9 mmHg. In all participants, a large increase in Ci (165 ± 84%; P < 0.001 vs. seated baseline) occurred 2 ± 2 beats following standing. Reductions in Ri occurred 11 ± 3 beats after standing (Ci vs. Ri delay: P < 0.001). The increase in Ci contributed to maintained systolic BV before the decrease in Ri. The present results demonstrate rapid, large but transient increases in Ci that precede reductions in Ri, in response to standing-induced reductions in BP. Therefore, Ci represents a discreet component of cerebrovascular responses during acute decreases in BP and, consequently, dynamic autoregulation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Historically, dynamic cerebral autoregulation has been characterized by adjustments in cerebrovascular resistance following systematic changes in blood pressure. However, with the use of Windkessel modeling approaches, this study revealed rapid and large increases in cerebrovascular compliance that preceded reductions in cerebrovascular resistance following standing-induced blood pressure reductions. Importantly, the rapid cerebrovascular compliance response contributed to preservation of systolic blood velocity during the transient hypotensive phase. These results broaden our understanding of dynamic cerebral autoregulation.

Keywords: cerebral autoregulation, cerebrovascular compliance, cerebrovascular resistance, modified Windkessel model, transcranial Doppler ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

During periods of transient blood pressure (BP) alterations, cerebrovascular adjustments underlie the autoregulatory response that defends cerebral perfusion (1). To date, characterization of autoregulation has focused primarily on alterations in cerebrovascular resistance achieved by adjustments in vessel diameter through myogenic, metabolic, and/or neural mechanisms. Indeed, impairments in cerebral autoregulation accompany abnormal cerebrovascular resistance responses to deviations in BP (1, 4, 21). However, solely focusing on cerebrovascular resistance conceals the contribution of broader mechanical features of the cerebral circulation to dynamic cerebral blood flow regulation.

In contrast to vascular resistance, which reflects changes in vessel diameter, vascular compliance represents the dynamic distension and recoiling action of the vasculature during oscillatory changes in BP between systole and diastole, respectively. Vascular compliance relies on the elastic properties of the vascular wall and forms a fundamental property of oscillatory blood flow control (31). Importantly, our previous study of the forearm vascular bed identified changes in vascular compliance, independent of alterations in vascular resistance, during maneuvers affecting myogenic and/or neural regulation of the circulation (31). These data illustrate that vascular compliance and resistance represent independent but complementary means of regulating blood flow (31). Here we address how cerebrovascular compliance and resistance contribute to cerebral autoregulatory responses.

Compliance of an arterial vascular bed can be examined noninvasively with Windkessel models using concurrent measures of BP and blood flow and known mathematical relationships between their individual harmonics (13, 30–33). Previous investigations applying Windkessel models to the cerebral vascular bed have proposed that compliance contributes to cerebrovascular flow dynamics (9, 26, 27, 34). These earlier approaches compared characteristic resistance-based models of cerebral autoregulation to Windkessel models as predictors of cerebral blood velocity (BV) changes during transient increases and decreases in BP; Windkessel models incorporating measures of vascular resistance and compliance explained greater variation in BV (9, 26, 27) than single-resistance models (9, 26). However, these studies did not examine within-cardiac cycle cerebrovascular compliance or how these changes might relate temporally to changes in vascular resistance during alterations in BP.

Hypotensive models of dynamic cerebral autoregulation, including sit-to-stand (19) and thigh-cuff (4) protocols, are consistently associated with increased amplitude of the oscillatory cerebral BV waveforms during the period of decreased BP. Importantly, the increased amplitude of the BV waveforms appears to result from sustained systolic but decreased diastolic BV components. Moreover, whereas myogenic, metabolic, and neurally mediated alterations in vascular resistance are expected to be associated with slight delays due to signaling and transduction events, increased pulsatility of BV can be observed immediately upon standing (19) or thigh-cuff release (4). These observations suggest a rapid increase in cerebrovascular compliance, which contrasts with the expected low- to very-low-frequency dominance of resistance-based models (10). Therefore, the cerebrovascular response to reductions in perfusion pressure may involve diverging patterns in vascular compliance and resistance metrics.

Therefore, this research tested the hypothesis that cerebrovascular processes induced by reductions in BP involve increases in cerebrovascular compliance contributing to the preservation of systolic BV. The present study employed a Windkessel modeling approach to quantify within-beat changes in cerebrovascular compliance and resistance during transient reductions in BP induced by a sit-to-stand model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

The Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at Western University approved the study. This study adhered to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, except for registration in a database. Each participant provided informed, written consent following verbal and written explanations of study procedures.

Participants.

Nine (3 women) young, healthy adults (24 ± 4 yr, 176 ± 10 cm, and 68 ± 10 kg) participated in the current investigation. Participants were normotensive, free of cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors, free of respiratory disease or illness, not diagnosed with neurological disorders or major psychiatric conditions, and not currently taking medications known to affect blood pressure or autonomic function. Female participants were not on oral contraceptives, and we did not control for menstrual cycle in the present study.

Experimental protocol.

Before testing, participants fasted for at least 4 h and abstained from caffeine and alcohol consumption and vigorous physical activity for 12 h. Participants completed a detailed medical history questionnaire, and anthropometric measurements were recorded. Participants voided their bladder before commencement of testing to minimize the effect of bladder distension on blood pressure (12).

Participants were instrumented with a single-lead electrocardiogram (ADInstruments Bio Amp FE132, Bella Vista, New South Wales, Australia) for continuous measurement of heart rate (HR). Finger photoplethysmography (Finometer, Finapres Medical Systems, Enschede, The Netherlands) collected continuous finger arterial BP from the left or right hand. Brachial artery BP waves were reconstructed from finger arterial BP waves (6). End-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressures (; n = 7) were monitored with a respiratory gas analyzer (ML206, ADInstruments, Bella Vista, New South Wales, Australia). Two participants did not wear a face mask, which prevented measurement of . Participants wore a headband device that supported a 2-MHz pulsed wave transducer (Neurovision TOC2M, Multigon Industries, Elmsford, CA) for insonation of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and collection of cerebral BV as the instantaneous peak velocity. Data were sampled at 1,000 Hz with an online data acquisition and analysis system (LabChart 8, PowerLab, ADInstruments, Bella Vista, New South Wales, Australia) and stored for subsequent offline analysis.

Data were collected during a sit-to-stand protocol. Participants were fitted with a sling to maintain their hand with the finger photoplethysmograph cuff in a fixed position at heart level. The study began after stabilization of all cardiovascular and cerebrovascular variables for at least 5 min in a seated posture. During data acquisition, participants rested in the seated position for 3 min then stood upright. To reach a fully upright position required ~2–3 s. Following 3 min of standing, participants returned to a seated position guided by researchers to avoid rotational head movement during the transition. Upon resuming the seated position, 3 min of sitting was performed before subsequent stand(s). The sit-to-stand protocol was performed twice to evaluate reproducibility between stands. A third trial was performed in the case of disturbances in the BP or transcranial Doppler (TCD) signal with standing (n = 2). Sitting and standing occurred voluntarily without the use of hands during spontaneous breathing and poikilocapnic conditions.

Data analysis.

Data analysis began 20 heartbeats before the initiation of standing and continued for 40 beats following the initiation of standing. From the first beat (i.e., 20 heartbeats before standing), every second beat thereafter was selected so that a total of 10 beats of sitting and 20 beats of standing were analyzed. Before input of data into the model, the BP waveform was shifted back in time to match the foot of its corresponding BV waveform, accounting for temporal delays between pressure pulse arrival at the MCA and brachial artery (32). For each beat selected, cerebrovascular compliance and resistance were calculated using the four-element lumped parameter modified Windkessel model as reported earlier in our laboratory (32) and described in more detail below. Because the modeled outcomes reflect BV and not true flow (no values of MCA cross-sectional area were available in the current study), we report the primary outcomes as indexes of cerebrovascular compliance (Ci) and resistance (Ri). In addition, the corresponding mean BP, systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), pulse pressure (PP), mean BV, systolic BV, and diastolic BV were obtained for each selected beat. Seated baseline Ci was determined as the average of the 10 beats of sitting. Subsequently, the change (∆) in Ci was calculated as the difference between peak Ci (single beat, maximum value) and seated baseline Ci. Additionally, the percent change in Ci was determined by dividing ∆Ci by seated baseline Ci and multiplying by 100. In contrast, ∆Ri, indexes of BP (i.e., mean BP, SBP, DBP, PP) and BV (i.e., mean BV, diastolic BV) were calculated as the difference between the nadir value (single beat, minimum value) and the average of seated baseline values. was averaged during seated baseline and standing. Determination of the number or beats or seconds to the start of change in BP, Ci, and Ri as well as the peak or nadir values occurred from the initiation of standing. Two investigators determined the number of beats to the start of change in BP, Ci, and Ri (M. E. Moir and S. A. Klassen). An intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated to evaluate interrater reliability. A strong agreement between the two investigators was observed (ICC = 0.96, P < 0.001) and a single investigator’s selection was used for analysis. The Ci of each extracted beat was correlated with corresponding PP, SBP, and DBP. Similarly, ∆Ci was correlated with ∆PP, ∆SBP, and ∆DBP. Additionally, seated baseline Ci was correlated with peak Ci.

Four-element lumped parameter modified Windkessel model.

The four-element lumped parameter modified Windkessel model has been described in detail previously (32). Briefly, four mechanical properties influence the relationship between oscillatory pressure and flow waveforms in a vascular bed: resistance to the steady component of flow, compliance, viscoelasticity, and inertia (32). Known mathematical relationships between individual harmonics of pressure and flow waveforms (32) permit the computation of these properties of a vascular bed using corresponding BP and flow waveforms measured at the entrance to that vascular bed. First, the quotient of mean BP and mean flow over the cardiac cycle determines resistance. Initial values of compliance, viscoelasticity, and inertia are prescribed to the harmonics of the waveforms and the model predicts a flow waveform (i.e., reassembles the harmonics into a complex waveform). Up to 1,000 iterations of modified values in compliance, viscoelasticity, and inertia are performed to determine the minimal error in the agreement between the model-predicted flow waveform and measured flow waveform. The process ends upon reaching minimal error, and the values of compliance, viscoelasticity, and inertia are representative of the corresponding properties of the vascular bed. In the present study, we focus on the values (indexes) of resistance (Ri) and compliance (Ci). Analysis was performed using custom written software (Matlab, MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Statistical analysis.

Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Nonparametric tests were used where appropriate as outlined below. A two-tailed Student’s paired t test assessed the difference between peak Ci and seated baseline Ci. To evaluate the delay between changes in Ci and Ri, a two-tailed Student’s paired t test assessed the difference in the beat number corresponding to the increase and decrease of Ci and Ri, respectively. A two-tailed Student’s paired t test assessed differences in between seated baseline and standing. Spearman’s rank order correlations evaluated the relationship between hemodynamic variables (i.e., PP, SBP, DBP) and Ci for each beat analyzed (i.e., a total of 30 beats). Additionally, Spearman’s rank order correlations assessed the relationship between the change in hemodynamic variables (i.e., ∆PP, ∆SBP, ∆DBP) and ∆Ci. A Pearson product-moment correlation evaluated the relationship between seated baseline Ci and peak Ci. Bland-Altman methods (3) and ICC assessed the agreement of seated baseline Ci and ∆Ci between stand 1 and stand 2. With the Bland-Altman analysis, fixed and proportional bias were evaluated using a two-tailed Student’s paired t test (between variables from stand 1 and stand 2) and linear regression (differences regressed against means), respectively. Data are reported as means ± SD. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated. P ≤ 0.05 defined statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and SigmaPlot 12.5 (for Bland-Altman analysis; Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

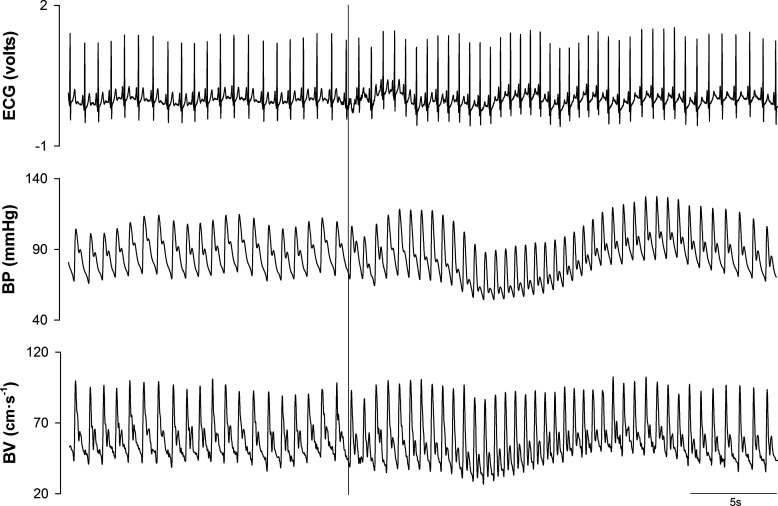

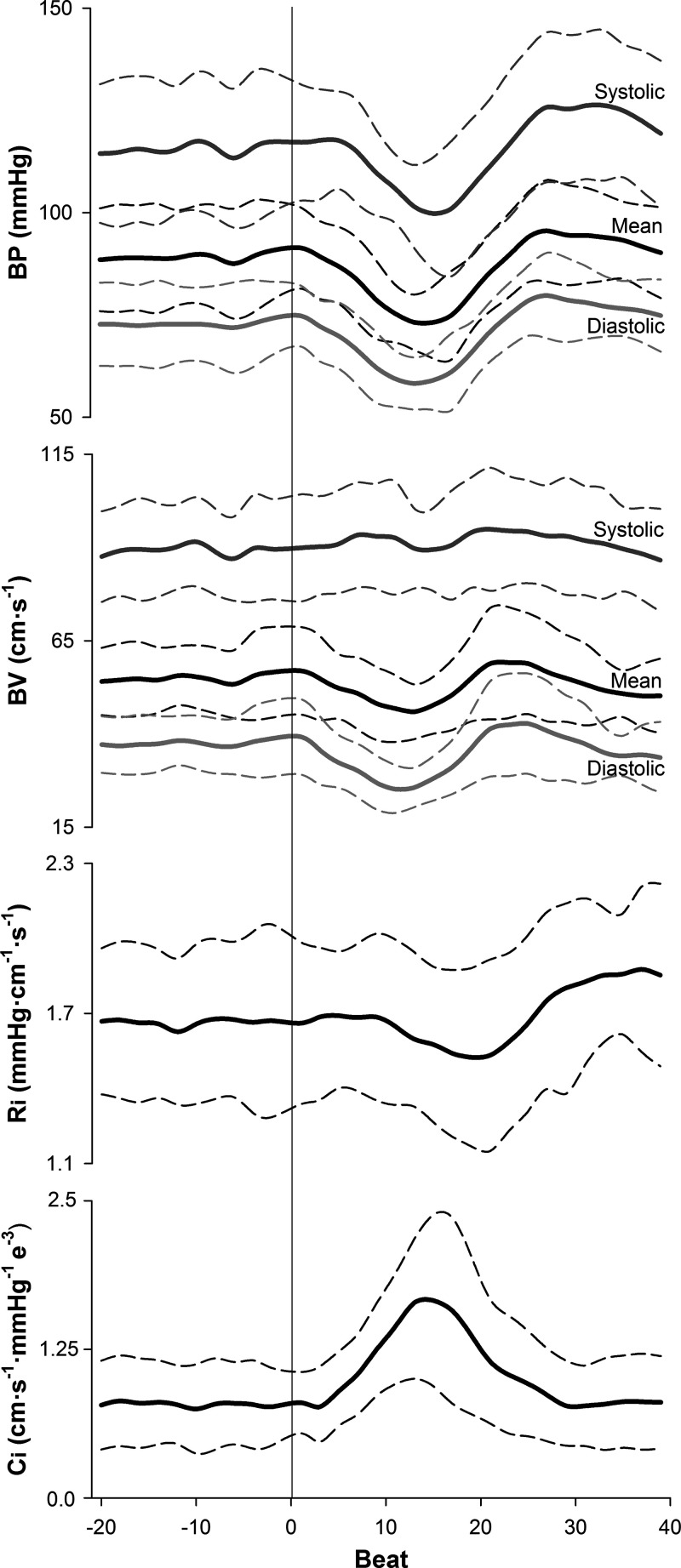

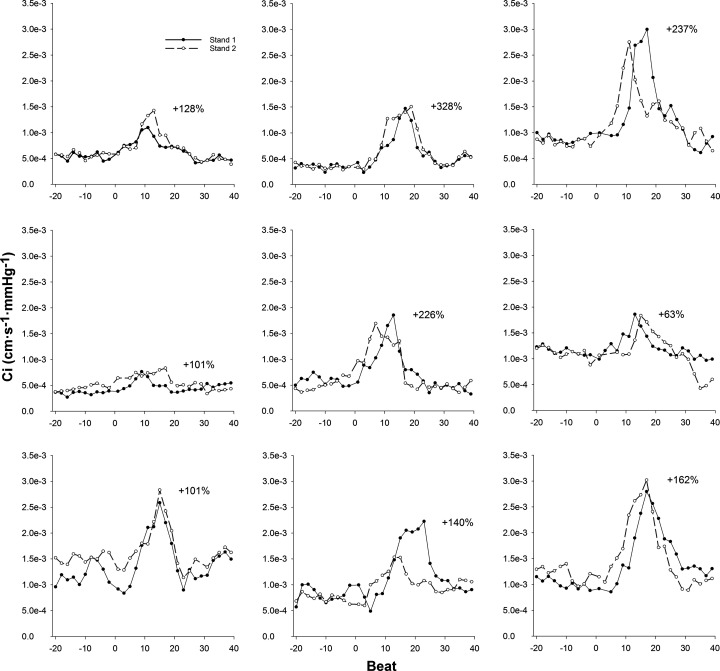

Representative data from one individual showing an ECG recording as well as brachial artery BP and MCA BV waveforms during a sit-to-stand task are presented in Fig. 1. This figure displays the selection of data that were utilized for analysis. Figure 2 presents the group averaged BP, BV, Ri, and Ci responses to standing. The sit-to-stand protocol elicited a reduction in mean BP of 20 ± 9 mmHg. One male participant exhibited BP responses (∆SBP = −56 mmHg, ∆DBP = −31 mmHg) that meet the criteria for initial orthostatic hypotension (28). BP began to fall 3 ± 2 beats after standing (3 ± 2 s) and nadir BP occurred at beat 14 ± 2 (11 ± 1 s). With standing, Ri was decreased 0.2 ± 0.1 mmHg·cm−1·s−1, with reductions initiated 11 ± 3 beats (9 ± 2 s) poststand. In contrast to the delayed decrease in Ri, Ci began to increase within 2 ± 2 beats (2 ± 1 s) from the onset of standing (P < 0.001, d = 3.7 from moment of Ri decrease). Ci increased 1.16e−3 ± 5.21e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1, and peak Ci occurred at beat 15 ± 3 (11 ± 1 s). Values of Ci for each beat analyzed during two trials of a sit-to-stand task are shown in Fig. 3 for each participant. During seated baseline, Ci was 7.87e−4 ± 3.55e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1 (range: 3.48e−4 to 1.36e−3 cm·s−1·mmHg−1). Upon standing, Ci increased by 165 ± 84% from seated baseline (range: 63% to 328%) with peak Ci being 1.95e−3 ± 7.42e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1 (range: 7.99e−4 to 2.91e−3 cm·s−1·mmHg−1; P < 0.001, d = 2.4 vs. seated baseline). After reaching its peak, Ci decreased toward seated baseline values. was unchanged during standing (39 ± 3 mmHg) compared with seated baseline (39 ± 3 mmHg; P = 0.94).

Fig. 1.

Representative data from 1 female participant, aged 19 yr, during one trial of a sit-to-stand protocol. Electrocardiogram (ECG) tracing, brachial artery blood pressure (BP), and middle cerebral artery blood velocity (BV) are shown. The vertical solid line represents the time of standing.

Fig. 2.

Group averaged brachial artery blood pressure (BP), middle cerebral artery blood velocity (BV), cerebrovascular resistance (Ri), and cerebrovascular compliance (Ci) responses during sit-to-stand task (n = 9; 6 men, 3 women). Horizontal thick solid lines represent means and horizontal thin dashed lines represent SD. The vertical solid line at beat 0 represents the time of standing.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic changes in cerebrovascular compliance (Ci) for each participant during 2 trials of a sit-to-stand protocol (n = 9; 6 men, 3 women). Standing occurs at beat 0. For each participant, the average percent change in Ci between 2 stands is reported.

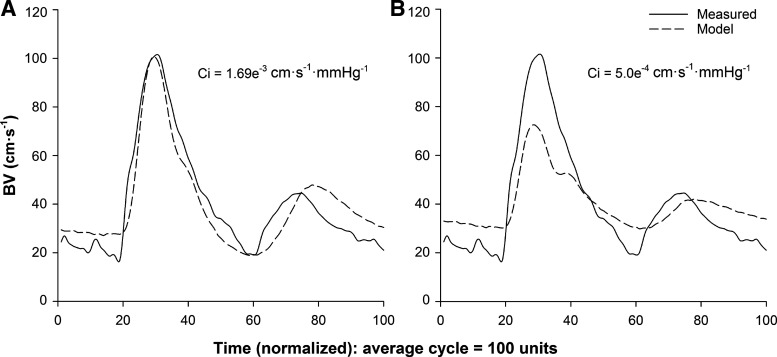

Figure 4 demonstrates the role of Ci in sustaining systolic BV during standing-induced reductions in BP from one individual. For the beat corresponding to peak Ci following the stand (Fig. 4A; beat 8, Ci = 1.69e−3 cm·s−1·mmHg−1), the value of Ci was manually adjusted to seated baseline values to mathematically prevent the increase (Fig. 4B; Ci = 5.0e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1). The observed result was a decrease in model-predicted systolic BV. This observation was representative of all participants.

Fig. 4.

Representative data from one male participant, aged 24 yr, showing the effect of changing the value of cerebrovascular compliance (Ci) on model-predicted blood velocity (BV) outcomes. A: beat corresponding to peak Ci following standing (Ci = 1.69e−3 cm·s−1·mmHg−1). B: same beat with Ci manipulated to remain at seated baseline values (Ci = 5.0e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1).

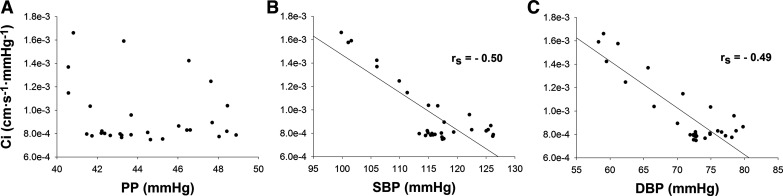

No significant correlation was observed between Ci and corresponding PP (P = 0.40; Fig. 5A). In contrast, moderate negative relationships were found between Ci and corresponding values of SBP (rs = −0.50, P = 0.005; Fig. 5B) and DBP (rs = −0.49, P = 0.007; Fig. 5C). Additionally, no significant correlations were observed between ∆Ci and corresponding ∆PP (P = 0.24), ∆SBP (P = 0.22), or ∆DBP (P = 0.87). A moderate, positive relationship was observed between seated baseline Ci and peak Ci (r = 0.77, P = 0.02).

Fig. 5.

Correlations between hemodynamic variables and cerebrovascular compliance (Ci). A: Spearman’s rank order correlation (rs) between pulse pressure (PP) and Ci (P = 0.40). B: Spearman’s rank order correlation (rs) between systolic blood pressure (SBP) and Ci (P = 0.005). C: Spearman’s rank order correlation (rs) between diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and Ci (P = 0.007).

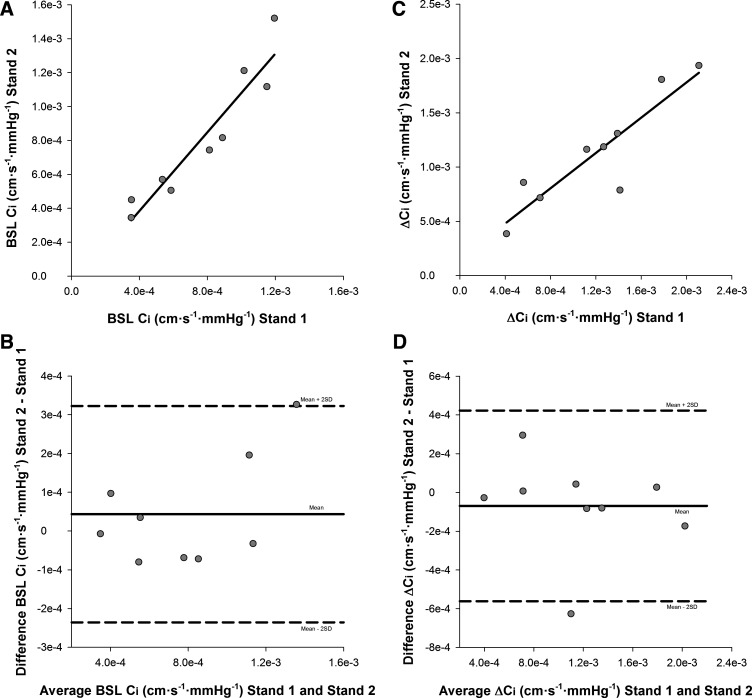

Pearson’s test of correlation showed a strong relationship between seated baseline Ci from stand 1 and stand 2 (r = 0.95, P < 0.001; Fig. 6A). Bland-Altman analysis demonstrated good agreement between baseline Ci from stand 1 (7.65e−4 ± 3.24e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1) and stand 2 (8.09e−4 ± 3.97e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1; mean difference: 4.36e−5 ± 1.40e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1, limits of agreement: −2.36e−4, 3.23e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1; Fig. 6B). Seated baseline Ci did not demonstrate fixed (P = 0.38) or proportional bias (b: 0.21, P = 0.14) across stands. ICC analysis revealed strong absolute agreement between baseline Ci from stand 1 and stand 2 [ICC = 0.96, P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.84–0.99].

Fig. 6.

Bland-Altman analysis to assess the agreement in seated baseline (BSL) cerebrovascular compliance (Ci) and the change in (∆) Ci between stand 1 and stand 2 (n = 9; 6 men, 3 women). A: Pearson’s test of correlation for BSL Ci (r = 0.95, P < 0.001). B: Bland-Altman plot of agreement displaying the difference in BSL Ci between stands as a function of the mean of BSL Ci across stands. Mean difference (solid line) and confidence limits of the mean difference (±2 SD; dashed lines) are shown. C: Pearson’s test of correlation for ∆Ci (r = 0.90; P = 0.001). D: Bland-Altman plot of agreement displaying the difference in ∆Ci between stands as a function of the mean of ∆Ci across stands. Mean difference (solid line) and confidence limits of the mean difference (±2 SD; dashed lines) are shown.

Additionally, Pearson’s test of correlation showed a strong relationship between ∆Ci from stand 1 and stand 2 (r = 0.90, P = 0.001; Fig. 6C). Bland-Altman analysis demonstrated good agreement between ∆Ci from stand 1 (1.20e−3 ± 5.62e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1) and stand 2 (1.13e−3 ± 5.08e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1; mean difference: −6.94e−5 ± 2.46e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1, limits of agreement: −5.61e−4, 4.22e−4 cm·s−1·mmHg−1; Fig. 6D). Furthermore, ∆Ci did not demonstrate fixed (P = 0.42) or proportional bias (b: −0.11, P = 0.56) across stands. ICC analysis revealed strong absolute agreement between ∆Ci from stand 1 and stand 2 (ICC = 0.95, P < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.78–0.99).

DISCUSSION

The present study provides novel insight into the role of cerebrovascular compliance in cerebral autoregulatory processes. To our knowledge, this study reports the first observation of rapid and large but transient increases in Ci with standing-induced reductions in BP. Of note, the Ci response was distinctly different from the changes in cerebrovascular resistance, which were initiated several seconds later. In contrast to the delayed reduction in Ri, the change in Ci corresponded temporally to the transient change in BP. The outcome of the rapid Ci response was a maintenance of systolic BV throughout the period of decreased BP during the transition from sitting to standing. Therefore, rapid and transient changes in Ci appear to contribute to the autoregulatory response to reductions in BP.

Historically, cerebrovascular resistance has been considered as the fundamental component of cerebral autoregulatory responses. More recently, studies have documented that application of Windkessel models incorporating both vascular compliance and resistance, account for greater variation in MCA velocity during dynamic alterations in BP (9, 26, 27) compared with resistance (9) or BP alone (26), suggesting a quantifiable role of vascular compliance in autoregulatory control. However, these studies did not account for actions of drugs on vascular responses (9) and used low pass filtered data (9, 26, 27), which may have removed rapid compliance patterns. Nonetheless, the present results support and expand upon these previous findings, providing evidence of large, rapid increases in Ci that occur during transient reductions in BP. Furthermore, an important observation of the current study was that transient increases in Ci can precede reductions in Ri by ~7 s during the hypotensive phase evoked by standing.

The finding of diverging Ci and Ri patterns to standing-induced BP reductions suggest that vascular compliance and resistance represent distinct processes of vasomotor control. While this represents the first observation in the cerebral vascular bed, previous findings in the peripheral vasculature support this notion. For example, sympathoexcitation induced by lower body negative pressure (24), cold pressor test (7, 24), or mental stress (7) reduced brachial or radial arterial compliance while sympathoinhibition through brachial plexus blockade (15) increased radial arterial compliance; in all cases compliance changed independently of arterial diastolic diameter (i.e., resistance). Therefore, vascular compliance and resistance represent distinct but complementary means of regulating flow in the cerebral circulation.

The impact of such rapid and large changes in Ci can be observed in the preservation of systolic BV throughout the transient hypotensive period. Specifically, while mean and diastolic BV are decreased upon standing, systolic BV was maintained to seated baseline levels. This BV pattern is consistent with data that vascular compliance predominantly affects systolic flow (13, 33) while vascular resistance strongly influences mean and diastolic flow (31, 33). Based on these data, in the absence of augmented Ci with standing, systolic BV would decrease in addition to diastolic BV, leading theoretically to a larger drop in mean BV and therefore total cerebral blood flow. Indeed, when Ci is manipulated to remain at seated baseline values, a marked reduction in model-predicted systolic BV is observed in all participants. Consequently, these data broaden our understanding of dynamic cerebral autoregulation to include contributions from vascular compliance in the preservation of cerebral blood flow during transient reductions in BP.

The mechanisms mediating rapid augmentation of Ci with standing are likely complex and remain speculative. The viscoelastic properties of blood vessels produce a curvilinear relationship between pressure and volume where greater compliance is expressed at lower levels of BP (16). Thus reductions in BP during standing and subsequent relocation along the pressure-volume curve may have provided passive momentary enhancements to within-beat Ci. Furthermore, reductions in intravascular BP would affect the transmural pressure gradient across cerebral vessels that forms the basis of myogenic reactivity. Bank and colleagues (5) reported an inverse relationship between transmural pressure and brachial artery compliance. In fact, myogenic responses elicited by arm elevation produced an increase in brachial artery compliance (13, 31) while resistance remained unchanged (31). Therefore, augmentation of Ci in the present investigation may be attributed to active myogenic-mediated reductions in vascular contractile state.

Reductions in extravascular pressure upon standing are also expected, contributing passively by increasing the vessel’s ability to express its inherent compliance (17, 32). Recently, an investigation from our laboratory proposed intracranial pressure (ICP), arising from cerebral venous blood volume, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the brain tissue, influences the operating point of Ci in the supine position (32). Reductions in ICP on moving from supine to sitting postures (18, 23) have been observed, due to hydrostatic reductions in cerebral venous volume (2) and translocation of CSF from the brain to the spinal canal (20). Corresponding changes in ICP from the seated to standing postures, when head elevation above the heart remains constant, are not clear but previous data suggest further reductions are expected (18, 22). However, we expect ICP to remain reduced during standing, which contrasts with the transient nature of the Ci response, which returned to baseline levels despite maintenance of the standing position. As such, the impact of ICP on Ci remains to be resolved.

Importantly, strong within-individual reliability was demonstrated in the current study for seated baseline Ci and the increase in Ci with standing. However, marked inter-individual variability was observed in Ci responses to standing. Nonetheless, a large and rapid increase in Ci was observed in all participants. Therefore, we speculate that augmented Ci with standing-induced BP reductions represents a fundamental response of the cerebral vasculature that may become modified by factors including aging or disease. Additionally, a major predictor of peak Ci was seated baseline Ci. Therefore, variations in baseline Ci between participants may arise from differences in inherent elasticity of the cerebral vasculature, hormonal variations across the menstrual cycle, cardiorespiratory fitness (14), and baseline hemodynamic parameters (e.g., BP, ICP).

There are methodological limitations that should be considered for the present study. First, measures of MCA cross-sectional area were not obtained and BV, rather than flow, calculated an index of cerebrovascular compliance (i.e., Ci). Based on magnetic resonance imaging methods, our determinations are that over 1 min of hypercapnic stimuli are needed to observe measurable changes in MCA cross-sectional area (11). Additional studies with higher temporal resolution are needed to establish the impact of decreased BP on MCA changes within the first minute. Nonetheless, myogenic dilation of the MCA would be expected to produce a reduction in BV if total flow stayed the same. Yet, systolic BV remained constant despite the reduced BP. Therefore, additional mechanisms must be considered. The values of Ci reported in the present study are anticipated to scale to inherent compliance of the cerebral vasculature. Second, the present investigation employed a lumped parameter model for computation of Ci, which substitutes the complex structure of an arterial vascular bed (i.e., branching structure) with a single tube that encompasses properties representing the bed as a whole (29). With this approach, we are unable to determine if changes in Ci observed with standing are uniform across the entire cerebral vascular bed or if differential responses exist at various levels of the bed (i.e., pial arteries vs. parenchymal arterioles). Third, due to access difficulties, peripheral measures of BP were used to represent MCA BP waveforms. Unfortunately, we do not know if, or how, BP waveforms change between the brachial artery and the MCA although differences in the structure of the vessel (i.e., elastin, collagen content) (25), as well as ICP may exert some impact. Nevertheless, the Windkessel model obtained good agreement between the model-predicted and measured BV waveforms, suggesting any differences in the shape of the BP waveforms between the two sites would have little impact on model results. Finally, a transient reduction in BP was employed as a stimulus in the present investigation. Given the presence of hysteresis in the cerebral circulation (8), it remains unknown whether changes in Ci also contribute to cerebrovascular responses to transient increases in BP.

In conclusion, this study expands our knowledge of cerebral autoregulatory processes. While previous investigations suggested that cerebrovascular compliance contributes to the dynamic regulation of cerebral blood flow (9, 26, 27, 34), this study demonstrates rapid and large increases in Ci accompanying large reductions in BP elicited with a sit-to-stand technique. More importantly, the increase in Ci preceded reductions in Ri that are typically examined in the context of cerebral autoregulation. Despite delayed alterations in Ri, systolic BV remained elevated throughout the hypotensive period with standing. Consequently, the increase in Ci contributes to the preservation of systolic BV and therefore total cerebral blood flow before the onset of the quantifiable vasodilation. On the basis of these observations, it appears that cerebrovascular compliance provides a rapid but transient contribution to cerebral autoregulation in addition to alterations in cerebrovascular resistance.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant RGPIN-2018-06255 and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant 201503MOP-342412-MOVCEEA (to J.K.S). M.E.M is supported by an Ontario Graduate Doctoral Scholarship (OGS). S.A.K. was supported by a NSERC Doctoral Scholarship (PGS-D). J.K.S. is a Tier 1 Canadian Research Chair (CRC) in Integrative Physiology of Exercise and Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.E.M., M.Z., and J.K.S. conceived and designed research; M.E.M. and S.A.K. performed experiments; M.E.M. and S.A.K. analyzed data; M.E.M., S.A.K., M.Z., and J.K.S. interpreted results of experiments; M.E.M. prepared figures; M.E.M. and J.K.S. drafted manuscript; M.E.M., S.A.K., M.Z., and J.K.S. edited and revised manuscript; M.E.M., S.A.K., M.Z., and J.K.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Experiments were performed in the Neurovascular Research Laboratory (J.K.S.) and the Laboratory for Brain and Heart Health (J.K.S.) at the University of Western Ontario.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaslid R, Lindegaard KF, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke 20: 45–52, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alperin N, Lee SH, Sivaramakrishnan A, Hushek SG. Quantifying the effect of posture on intracranial physiology in humans by MRI flow studies. J Magn Reson Imaging 22: 591–596, 2005. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in medicine: the analysis of method comparison studies. Statistician 32: 307–317, 1983. doi: 10.2307/2987937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey DM, Jones DW, Sinnott A, Brugniaux JV, New KJ, Hodson D, Marley CJ, Smirl JD, Ogoh S, Ainslie PN. Impaired cerebral haemodynamic function associated with chronic traumatic brain injury in professional boxers. Clin Sci (Lond) 124: 177–189, 2013. doi: 10.1042/CS20120259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bank AJ, Wilson RF, Kubo SH, Holte JE, Dresing TJ, Wang H. Direct effects of smooth muscle relaxation and contraction on in vivo human brachial artery elastic properties. Circ Res 77: 1008–1016, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.77.5.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos WJW, van Goudoever J, van Montfrans GA, van den Meiracker AH, Wesseling KH. Reconstruction of brachial artery pressure from noninvasive finger pressure measurements. Circulation 94: 1870–1875, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.8.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutouyrie P, Lacolley P, Girerd X, Beck L, Safar M, Laurent S. Sympathetic activation decreases medium-sized arterial compliance in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H1368–H1376, 1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brassard P, Ferland-Dutil H, Smirl JD, Paquette M, Le Blanc O, Malenfant S, Ainslie PN. Evidence for hysteresis in the cerebral pressure-flow relationship in healthy men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H701–H704, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00790.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan GS, Ainslie PN, Willie CK, Taylor CE, Atkinson G, Jones H, Lovell NH, Tzeng YC. Contribution of arterial Windkessel in low-frequency cerebral hemodynamics during transient changes in blood pressure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 917–925, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01407.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claassen JA, Levine BD, Zhang R. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation during repeated squat-stand maneuvers. J Appl Physiol (1985) 106: 153–160, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90822.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coverdale NS, Lalande S, Perrotta A, Shoemaker JK. Heterogeneous patterns of vasoreactivity in the middle cerebral and internal carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1030–H1038, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagius J, Karhuvaara S. Sympathetic activity and blood pressure increases with bladder distension in humans. Hypertension 14: 511–517, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.14.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frances MF, Goswami R, Rachinsky M, Craen R, Kiviniemi AM, Fleischhauer A, Steinback CD, Zamir M, Shoemaker JK. Adrenergic and myogenic regulation of viscoelasticity in the vascular bed of the human forearm. Exp Physiol 96: 1129–1137, 2011. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.059188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furby HV, Warnert EA, Marley CJ, Bailey DM, Wise RG. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with increased middle cerebral arterial compliance and decreased cerebral blood flow in young healthy adults: a pulsed ASL MRI study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 271678X19865449, 2019. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19865449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grassi G, Giannattasio C, Failla M, Pesenti A, Peretti G, Marinoni E, Fraschini N, Vailati S, Mancia G. Sympathetic modulation of radial artery compliance in congestive heart failure. Hypertension 26: 348–354, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.26.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen F, Mangell P, Sonesson B, Länne T. Diameter and compliance in the human common carotid artery–variations with age and sex. Ultrasound Med Biol 21: 1–9, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(94)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu X, Alwan AA, Rubinstein EH, Bergsneider M. Reduction of compartment compliance increases venous flow pulsatility and lowers apparent vascular compliance: implications for cerebral blood flow hemodynamics. Med Eng Phys 28: 304–314, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawley JS, Petersen LG, Howden EJ, Sarma S, Cornwell WK, Zhang R, Whitworth LA, Williams MA, Levine BD. Effect of gravity and microgravity on intracranial pressure. J Physiol 595: 2115–2127, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipsitz LA, Mukai S, Hamner J, Gagnon M, Babikian V. Dynamic regulation of middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity in aging and hypertension. Stroke 31: 1897–1903, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnæs B. Body position and cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Part 1: clinical studies on the effect of rapid postural changes. J Neurosurg 44: 687–697, 1976. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.44.6.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moir ME, Klassen SA, Al-Khazraji BK, Woehrle E, Smith SO, Matushewski BJ, Kozić D, Dujić Ž, Barak OF, Shoemaker JK. Impaired dynamic cerebral autoregulation in trained breath-hold divers. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 1694–1700, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00210.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen LG, Petersen JC, Andresen M, Secher NH, Juhler M. Postural influence on intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressure in ambulatory neurosurgical patients. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R100–R104, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00302.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poca MA, Sahuquillo J, Topczewski T, Lastra R, Font ML, Corral E. Posture-induced changes in intracranial pressure: a comparative study in patients with and without a cerebrospinal fluid block at the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery 58: 899–906, 2006. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000209915.16235.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salzer DA, Medeiros PJ, Craen R, Shoemaker JK. Neurogenic-nitric oxide interactions affecting brachial artery mechanics in humans: roles of vessel distensibility vs. diameter. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1181–R1187, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90333.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzeng YC, Ainslie PN. Blood pressure regulation IX: cerebral autoregulation under blood pressure challenges. Eur J Appl Physiol 114: 545–559, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2667-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzeng YC, Chan GS, Willie CK, Ainslie PN. Determinants of human cerebral pressure-flow velocity relationships: new insights from vascular modelling and Ca2+ channel blockade. J Physiol 589: 3263–3274, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzeng YC, MacRae BA, Ainslie PN, Chan GS. Fundamental relationships between blood pressure and cerebral blood flow in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 1037–1048, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00366.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieling W, Krediet CT, van Dijk N, Linzer M, Tschakovsky ME. Initial orthostatic hypotension: review of a forgotten condition. Clin Sci (Lond) 112: 157–165, 2007. doi: 10.1042/CS20060091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zamir M. Hemo-Dynamics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamir M, Goswami R, Liu L, Salmanpour A, Shoemaker JK. Myogenic activity in autoregulation during low frequency oscillations. Auton Neurosci 159: 104–110, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamir M, Goswami R, Salzer D, Shoemaker JK. Role of vascular bed compliance in vasomotor control in human skeletal muscle. Exp Physiol 92: 841–848, 2007. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.037937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamir M, Moir ME, Klassen SA, Balestrini CS, Shoemaker JK. Cerebrovascular compliance within the rigid confines of the skull. Front Physiol 9: 940, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamir M, Norton K, Fleischhauer A, Frances MF, Goswami R, Usselman CW, Nolan RP, Shoemaker JK. Dynamic responsiveness of the vascular bed as a regulatory mechanism in vasomotor control. J Gen Physiol 134: 69–75, 2009. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang R, Behbehani K, Levine BD. Dynamic pressure-flow relationship of the cerebral circulation during acute increase in arterial pressure. J Physiol 587: 2567–2577, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]