Abstract

Background:

Population-based estimates of prevalence of anxiety and comorbid depression are lacking. Therefore, we estimated the prevalence and risk factors for postpartum anxiety and comorbid depressive symptoms in a population-based sample of women.

Methods:

Using multinomial logistic regression, we examined the prevalence and risk factors for postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms using 2009–2010 data from the Illinois and Maryland Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, a population-based survey of mothers who gave birth to live infants. Survey participants are asked validated screening questions on anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Results:

Among 4451 postpartum women, 18.0% reported postpartum anxiety symptoms, of whom 35% reported postpartum depressive symptoms (6.3% overall). In the multivariable model, higher numbers of stressors during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] range: 1.3–9.7) and delivering an infant at ≤ 27 weeks gestation (aOR range: 2.0–5.7) were associated with postpartum anxiety and postpartum depressive symptoms, experienced individually or together. Smoking throughout pregnancy was associated with postpartum anxiety symptoms only (aOR = 2.3) and comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms (aOR = 2.9).

Conclusions:

Given the possible adverse effects of postpartum anxiety and comorbid depression on maternal health and infant development, clinicians should be aware of the substantial prevalence, comorbidity, and risk factors for both conditions and facilitate identification, referral, and/or treatment.

Introduction

Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum anxiety are less well studied than those for postpartum depression.1,2 Prevalence estimates of postpartum anxiety from community-and hospital-based samples of mostly higher educated, white women are as high as 17% to 20%,3–5 while one nationally representative study from 2001–2002 estimates the prevalence at 12%.6 Other studies have examined the prevalence of specific types of anxiety, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)7 and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD),8 with reported prevalence estimates at 9% for PTSD and 11% for OCD symptoms. Mothers with postpartum anxiety have higher stress, lower sense of competence, and less social support than healthy controls.9 Most, but not all, studies on the effects of antenatal anxiety on infant and child development show delayed mental and physical development in infants and lower academic achievement in children and adolescents.10

We found only one 10-year-old population-based study on the prevalence of postpartum anxiety6 and no population- based estimates of the prevalence of comorbid postpartum anxiety and depression. In a nationally representative sample of men and women, approximately half of those with anxiety had comorbid depression and one third of adults with depression had comorbid anxiety.11 Smaller studies among postpartum women show that a third of women with major depressive episode have comorbid anxiety12 and 10%–50% of women with anxiety symptoms experience comorbid depressive symptoms.13 Assessing comorbidity is important because adults with comorbid anxiety and depression may experience more severe symptoms than adults with a single condition, and comorbidity may influence the treatment chosen.14,15

Professional organizations strongly encourage screening for postpartum depression16,17; however, prenatal and postpartum anxiety is less commonly the focus of clinicians and researchers.18 Not screening for anxiety symptoms may underestimate the prevalence of mental health disorders postpartum and the need for mental health services19 and put mothers and their infants at increased risk of adverse outcomes. Larger, population-based studies are needed to understand the current prevalence of postpartum anxiety and comorbid depression and their associated risk factors. Therefore, we used population-based data from women delivering live infants in Maryland and Illinois to examine the burden, risk factors, and infant outcomes associated with anxiety and comorbid depression among postpartum women.

Materials and Methods

We examined the prevalence and risk factors for postpartum anxiety and comorbid depressive symptoms from the 2009 and 2010 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS; www.cdc.gov/PRAMS). PRAMS is an annual population-based, self-reported survey of postpartum women that assesses maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy. PRAMS is conducted in 40 states and New York City through health departments in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A stratified sample of mothers who delivered live infants was selected from each state’s birth certificate records. Selected women were mailed a standardized questionnaire 2–4 months after delivery. After three mailings, nonresponders were contacted up to 15 times by phone for an interview. To be included in the sample, questionnaires must have been completed within 9 months of delivery. Each participant provided written informed consent. The CDC institutional review board approved the PRAMS protocol. Survey and birth certificate data were linked and weighted for sample design, nonresponse, and noncoverage. Data from states with response rates > 65% can be reported.

Postpartum anxiety symptoms was based on responses to two statements: “I have felt restless or fidgety” and “I have felt panicky.” Categorical responses were based on the frequency of experiencing these feelings since the woman’s new baby was born. Responses and their associated numerical values included “never” (1), “rarely” (2), “sometimes” (3), “often” (4) or “always” (5). When the sum of the responses totaled ≥ 6, a woman was considered to have postpartum anxiety symptoms. The sensitivity and specificity of this algorithm for postpartum anxiety compared to a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) is 75% and 77%, respectively.20 Postpartum depressive symptoms was derived from responses to three statements: “I have felt down, depressed or sad,” “I have felt hopeless,” and “I have felt slowed down physically.” Categorical responses were similar to those for postpartum anxiety symptoms. When the sum of the responses totaled ≥ 10, the woman was considered to have postpartum depressive symptoms. The sensitivity and specificity of this algorithm for postpartum depression compared to the SCID is 57% and 87%, respectively, and compares favorably to other depression screeners.20

For 2009 and 2010, states could choose to include the two optional questions on postpartum anxiety symptoms, while the three questions on postpartum depressive symptoms were answered by all states’ PRAMS participants. Illinois, Maryland, and Louisiana included questions on postpartum anxiety. However, the response rate in Louisiana was < 65% for these years. Therefore, information included in this report is from Illinois and Maryland.

Demographic, pregnancy, and infant characteristics examined in the analysis were based on mother’s self-report from the PRAMS questionnaire and the birth certificate. Characteristics from the PRAMS questionnaire were household income, Medicaid coverage during pregnancy and/or delivery, prepregnancy alcoholic drinks per week, whether the pregnancy was planned, prenatal smoking status, maternal diabetes (preexisting, gestational, or none), and infant length of stay in the hospital. PRAMS also inquired about 13 stressful life events occurring during pregnancy (such as divorce and marital discord, inability to pay bills and job loss, family illness or death, experiencing violence or homelessness, and partner’s drug use or other legal problems). Based on previous research,21 we examined both cumulative number of events and dichotomous categories of stress (emotional, financial, partner-related, and traumatic). Characteristics from the birth certificate included maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, parity, marital status, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), state of residence, maternal hypertension (preexisting, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, and none), whether the delivery was vaginal or cesarean, year of infant birth, gestational age at birth, and small (< 10th percentile) or large (> 90th percentile) for gestational age. We examined differences in infant length of hospital stay stratified by the mode of delivery (vaginal or cesarean).

We examined overall prevalence of postpartum anxiety symptoms, comorbid postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms, and postpartum depressive symptoms only. We categorized women into one of four groups based on their anxiety and depressive symptoms: (1) postpartum anxiety symptoms only; (2) postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms; (3) postpartum depressive symptoms only; and (4) neither condition. We used Wilcoxon rank-sum test to assess differences in mean anxiety and depressive symptoms scores by category. By maternal mental health status, we examined demographic characteristics, pregnancy-related complications, and infant outcomes that may be associated with maternal mental health based on previously published literature. We used chi-square tests and multivariable multinomial logistic regression to examine differences in characteristics between the four groups. Initially, we included all variables in the multivariable model hypothesized to be causally related to maternal mental health status. To conserve power to detect associations, variables that were not statistically associated with anxiety and/or depressive symptoms and that did not confound point estimates of other variables in the model were excluded from the final multivariable model. In sensitivity analyses, we examined whether similar associations existed when postpartum anxiety symptoms was defined as ≥ 8 and postpartum depressive symptoms was defined as ≥ 12.

In Illinois and Maryland in 2009 and 2010, 4639 women were surveyed and 96% (n = 4451) had information on postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms. Of the 4451 women, 95% (n = 4250) had information on demographic and health variables and were included in the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted in SUDAAN (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for sampling design and appropriate weights were used to generate population estimates.

Results

On average, women in this sample completed the questionnaire 4 months after their infant’s birth (range: 3–9 months). In this sample, 18.0 (95% confidence interval [CI]:16.5–19.6) reported postpartum anxiety symptoms compared to 9.0% (95% CI: 7.9–10.1) reporting postpartum depressive symptoms. Overall, 6.3% (95% CI: 5.4–7.3) reported both postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms (Table 1). Of the women reporting postpartum anxiety symptoms, 35% reported comorbid depressive symptoms. Of women reporting postpartum depressive symptoms, 64% reported comorbid anxiety symptoms. The average depressive symptom score among women reporting postpartum anxiety symptoms was 8.7 (standard error [SE] 0.13), compared to 5.3 (SE 0.04) among women not reporting anxiety symptoms (p-value < 0.001). The average anxiety score among women reporting postpartum depressive symptoms was 6.4 (SE 0.12), compared to 3.4 (SE 0.03) among women not reporting postpartum depressive symptoms (p < 0.001). Women reporting anxiety and depressive symptoms had higher mean anxiety scores (mean = 7.5, SE 0.07) than women with anxiety symptoms only (mean = 6.5, SE = 0.04) and higher mean depressive scores (mean = 11.6, SE 0.08) than women with depressive symptoms only (mean = 10.8, SE = 0.09; p < 0.001 for both comparisons).

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics by Postpartum Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Illinois and Maryland, 2009–2010

| Postpartum anxiety symptoms only | Postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms | Postpartum depressive symptoms only | No anxiety or depressive symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 506) | (n = 327) | (n = 181) | (n = 3440) | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Total | 11.7 | (10.5–13.0) | 6.3 | (5.4–7.3) | 2.7 | (2.1–3.3) | 79.3 | (77.7–80.9) |

| Age, yearsa | ||||||||

| < 25 | 12.0 | (9.7–14.7) | 7.9 | (6.1–10.3) | 2.6 | (1.7–4.1) | 77.5 | (74.1–80.5) |

| 25–34 | 11.8 | (10.2–13.7) | 6.2 | (5.0–7.6) | 2.6 | (1.9–3.6) | 79.3 | (77.1–81.4) |

| ≥ 35 | 10.7 | (8.5–13.4) | 3.9 | (2.7–5.5) | 2.9 | (2.0–4.1) | 82.5 | (79.5–85.2) |

| Marital statusa | ||||||||

| Married | 11.2 | (9.8–12.9) | 4.8 | (3.9–6.0) | 2.2 | (1.7–3.0) | 81.7 | (79.8–83.5) |

| Other | 12.4 | (10.4–14.7) | 8.6 | (7.0–10.6) | 3.3 | (2.4–4.6) | 75.7 | (72.8–78.3) |

| Education, yearsa | ||||||||

| < 12 | 13.5 | (10.4–17.3) | 6.0 | (4.0–8.9) | 3.6 | (2.2–5.7) | 76.9 | (72.5–80.8) |

| 12 | 12.8 | (10.3–15.7) | 9.0 | (6.9–11.7) | 2.0 | (1.2–3.3) | 76.2 | (72.6–79.5) |

| > 12 | 10.8 | (9.3–12.5) | 5.4 | (4.4–6.7) | 2.6 | (1.9–3.4) | 81.2 | (79.2–83.1) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||||

| White | 12.1 | (10.4–13.9) | 6.0 | (4.8–7.4) | 2.7 | (2.0–3.7) | 79.2 | (76.9–81.3) |

| Black | 14.2 | (11.4–17.5) | 8.9 | (6.7–11.7) | 2.1 | (1.3–3.5) | 74.7 | (70.8–78.3) |

| Hispanic | 7.7 | (5.6–10.4) | 4.0 | (2.6–6.2) | 3.1 | (2.0–4.9) | 85.2 | (81.8–88.0) |

| Other | 12.6 | (8.5–18.2) | 6.9 | (4.1–11.5) | 1.4 | (0.5–4.3) | 79.0 | (72.6–84.3) |

| Incomea | ||||||||

| < $10,000 | 14.6 | (11.5–18.4) | 9.9 | (7.3–13.3) | 4.0 | (2.6–6.2) | 71.5 | (66.8–75.7) |

| $10,000–$14,999 | 11.4 | (7.5–16.8) | 7.5 | (4.6–12.0) | 4.2 | (2.2–7.9) | 77.0 | (70.6–82.4) |

| $15,000–$49,999 | 10.3 | (8.2–12.8) | 7.3 | (5.6–9.6) | 1.8 | (1.1–2.9) | 80.6 | (77.5–83.4) |

| $50,000 + | 10.9 | (9.2–13.0) | 4.4 | (3.3–5.8) | 2.7 | (1.9–3.7) | 82.0 | (79.6–84.2) |

| Prepregnancy BMIa | ||||||||

| Underweight | 11.2 | (7.8–15.8) | 9.9 | (6.6–14.5) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.7) | 78.0 | (72.3–82.8) |

| Normal weight | 11.6 | (9.9–13.5) | 6.4 | (5.1–7.9) | 2.3 | (1.6–3.1) | 79.8 | (77.5–82.0) |

| Overweight | 11.7 | (8.6–15.7) | 4.9 | (3.1–7.8) | 3.1 | (1.7–5.6) | 80.3 | (75.6–84.2) |

| Obese | 12.6 | (10.1–15.6) | 6.2 | (4.5–8.4) | 4.1 | (2.8–5.9) | 77.2 | (73.6–80.4) |

| Prepregnancy alcoholic drinks/weeka | ||||||||

| None | 11.1 | (9.8–12.6) | 5.8 | (4.8–6.9) | 2.2 | (1.7–2.9) | 80.9 | (79.1–82.6) |

| 1–6 | 13.3 | (10.8–16.4 | 7.5 | (5.5–10.1 | 3.5 | (2.3–5.3 | 75.6 | (71.9–79.0 |

| ≥7 | 13.9 | (7.7–23.8) | 11.3 | (5.8–20.7) | 7.5 | (3.5–15.3) | 67.4 | (56.1–76.9) |

| Medicaid covereda,b | ||||||||

| Medicaid | 13.7 | (11.7–15.9) | 7.5 | (6.0–9.2) | 2.8 | (2.0–3.9) | 76.1 | (73.5–78.5) |

| Non-Medicaid | 10.1 | (8.7–11.8 | 5.4 | (4.3–6.7 | 2.6 | (1.9–3.5 | 81.9 | (79.8–83.8 |

| Planned pregnancya | ||||||||

| Yes | 10.1 | (8.6–11.7) | 4.8 | (3.8–6.0) | 2.2 | (1.6–3.0) | 83.0 | (80.9–84.8) |

| No | 13.7 | (11.8–16.0 | 8.3 | (6.8–10.2 | 3.1 | (2.2–4.1 | 74.9 | (72.2–77.4) |

| No. of stressful life events during pregnancya | ||||||||

| None | 8.8 | (6.9–11.0) | 2.3 | (1.4–3.6) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.9) | 87.9 | (85.4–90.1) |

| 1–2 | 10.7 | (9.0–12.7) | 4.7 | (3.6–6.2) | 2.5 | (1.8–3.6) | 82.1 | (79.7–84.3) |

| 3–5 | 15.9 | (13.2–19.2) | 10.2 | (7.9–13.0) | 4.1 | (2.8–5.9) | 69.8 | (65.9–73.4) |

| 6–13 | 16.1 | (10.7–23.4) | 21.4 | (15.4–28.9) | 5.8 | (3.1–10.5) | 56.7 | (48.3–64.8) |

| Smoking status during pregnancya | ||||||||

| Smoker | 21.6 | (16.8–27.4) | 17.3 | (12.9–22.9) | 4.1 | (2.3–7.1) | 57.0 | (50.6–63.2) |

| Quit | 13.6 | (9.9–18.4) | 8.8 | (5.8–13.0) | 3.3 | (1.8–6.1) | 74.3 | (68.6–79.3) |

| Nonsmoker | 10.3 | (9.1–11.7) | 4.7 | (3.8–5.7) | 2.4 | (1.9–3.1) | 82.6 | (80.9–84.2) |

| Statea | ||||||||

| Illinois | 10.4 | (8.8–12.2) | 5.3 | (4.2–6.7) | 2.3 | (1.6–3.2) | 82.0 | (79.8–84.0) |

| Maryland | 13.3 | (11.5–15.4) | 7.5 | (6.2–9.2) | 3.1 | (2.3–4.1) | 76.1 | (73.6–78.4) |

Chi square p-value < 0.05.

Medicaid coverage during prenatal care and/or delivery.

CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

Statistically significant differences in prevalence of postpartum anxiety and/or depressive symptoms were found for all demographic characteristics (Table 1). Women with the highest prevalence of postpartum anxiety symptoms only smoked throughout pregnancy (21.6%) and experienced 6–13 (16.1%) or 3–5 (15.9%) stressors during pregnancy. Women with the highest prevalence of comorbid postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms smoked throughout pregnancy (21.4%), experienced 6–13 stressors during pregnancy (17.3%) and drank ≥ 7 drinks per week prepregnancy (11.3%). While women with the highest prevalence of postpartum depressive symptoms only were those who drank ≥ 7 drinks per day before pregnancy (7.5%), those experiencing 6–13 stressors during pregnancy (5.8%) and women with annual household incomes between $10,000 and $14,999 (4.2%).

Statistically significant associations between postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms were found for gestational age at birth, infant birth weight, mode of delivery, and length of infant stay in the hospital (Table 2). Women with the highest prevalence of postpartum anxiety symptoms only were those with pre-existing diabetes (21.4%) and those whose infants stayed in the hospital > 14 days, whether delivered by cesarean delivery (19.0%) or vaginally (17.2%). Women with the highest prevalence of postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms were women who delivered their infants at ≤ 27 weeks gestation (22.7%) and whose infants stayed in the hospital ≤ 2 days (10.3%) or > 14 days (9.8%), when delivered by cesarean. Women with the highest prevalence of postpartum depressive symptoms only delivered infants at ≤ 27 weeks gestation (9.3%), had infants that stayed in the hospital > 14 days (7.1%) if delivered vaginally, and had small for gestational age infants (5.5%).

Table 2.

Pregnancy and Infant Outcomes by Maternal Postpartum Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Illinois and Maryland, 2009–2010

| Postpartum anxiety symptoms only | Postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms | Postpartum depressive symptoms only | No anxiety or depressive symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=506) | (n = 327) | (n = 181) | (n = 3440) | |||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Total | 11.7 | (10.5–13.0) | 6.3 | (5.4–7.3) | 2.7 | (2.1–3.3) | 79.3 | (77.7–80.9) |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Pre-existing diabetes | 21.4 | (12.7–33.8) | 5.4 | (1.9–14.1) | 3.0 | (0.8–11.0) | 70.2 | (57.5–80.4) |

| Gestational diabetes | 10.3 | (7.1–14.9) | 8.1 | (5.0–12.7) | 2.8 | (1.4–5.3) | 78.8 | (73.0–83.6) |

| None | 11.5 | (10.3–13.0) | 6.1 | (5.2–7.2) | 2.6 | (2.1–3.3) | 79.7 | (78.0–81.3) |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Hypertensiona | 15.2 | (10.5–21.5) | 6.5 | (3.7–11.2) | 3.9 | (2.1–7.4) | 74.3 | (67.4–80.2) |

| None | 11.5 | (10.2–12.8) | 6.3 | (5.4–7.4) | 2.6 | (2.1–3.3) | 80.0 | (78.0–81.2) |

| Gestational age at birth, weeksb | ||||||||

| ≤ 27 | 15.2 | (9.3–23.9) | 22.7 | (15.4–32.0) | 9.3 | (5.2–16.1) | 52.8 | (41.9–63.6) |

| 28–33 | 15.7 | (11.0–21.8) | 6.4 | (4.2–9.8) | 4.8 | (2.9–7.9) | 73.1 | (66.6–78.7) |

| 34–36 | 11.1 | (7.6–15.8) | 9.4 | (6.1–14.1) | 3.7 | (2.0–6.8) | 75.8 | (69.8–80.9) |

| ≥ 37 | 11.6 | (10.3–13.1) | 5.9 | (5.0–7.0) | 2.5 | (1.9–3.2) | 80.0 | (78.2–81.6) |

| Infant birth weightb | ||||||||

| Small for gestational age | 9.7 | (6.7–13.7) | 6.5 | (4.2–9.9) | 5.5 | (3.4–8.8) | 78.4 | (73.2–82.7) |

| Normal weight | 11.9 | (10.6–13.5) | 6.8 | (5.7–8.0) | 2.5 | (1.9–3.2) | 78.8 | (77.0–80.6) |

| Large for gestational age | 11.4 | (8.0–16.0) | 2.8 | (1.4–5.7) | 1.7 | (0.8–3.8) | 84.0 | (79.1–88.0) |

| Mode of deliveryb | ||||||||

| Cesarean | 11.6 | (9.7–13.8) | 8.4 | (6.7–10.4) | 3.3 | (2.4–4.6) | 76.7 | (73.9–79.3) |

| Vaginal | 11.7 | (10.2–13.4) | 5.2 | (4.2–6.4) | 2.3 | (1.7–3.1) | 80.7 | (78.7–82.6) |

| Infant length of stay in hospital, days | ||||||||

| Mothers with a vaginal deliveryb | ||||||||

| < 1–2 | 11.6 | (9.9–13.6) | 4.3 | (3.3–5.5) | 2.2 | (1.6–3.2) | 81.9 | (79.6–83.9) |

| 3–5 | 12.8 | (9.2–17.6) | 9.1 | (5.9–13.6) | 2.1 | (1.0–4.6) | 76.0 | (70.2–81.0) |

| 6–14 | 8.5 | (4.1–16.9) | 9.5 | (4.6–18.5) | 1.4 | (0.6–3.2) | 80.6 | (70.5–87.9) |

| > 14 | 17.2 | (9.5–29.1) | 6.5 | (3.8–10.9) | 7.1 | (2.7–17.2) | 69.3 | (57.6–78.9) |

| Mothers with a cesarean deliveryb | ||||||||

| < 1–2 | 9.9 | (6.2–15.4) | 10.3 | (6.5–15.8) | 2.4 | (1.1–5.2) | 77.5 | (70.8–83.1) |

| 3–5 | 12.0 | (9.6–14.9) | 8.2 | (6.1–10.8) | 3.7 | (2.5–5.4) | 76.2 | (72.6–79.5) |

| 6–14 | 9.6 | (5.0–17.7) | 2.8 | (1.4–5.6) | 3.0 | (0.8–10.0) | 84.6 | (75.9–90.5) |

| > 14 | 19.0 | (13.0–27.0) | 9.8 | (6.5–14.7) | 3.5 | (1.9–6.6) | 67.6 | (59.7–74.6) |

Includes pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia.

Chi square p-value < 0.05.

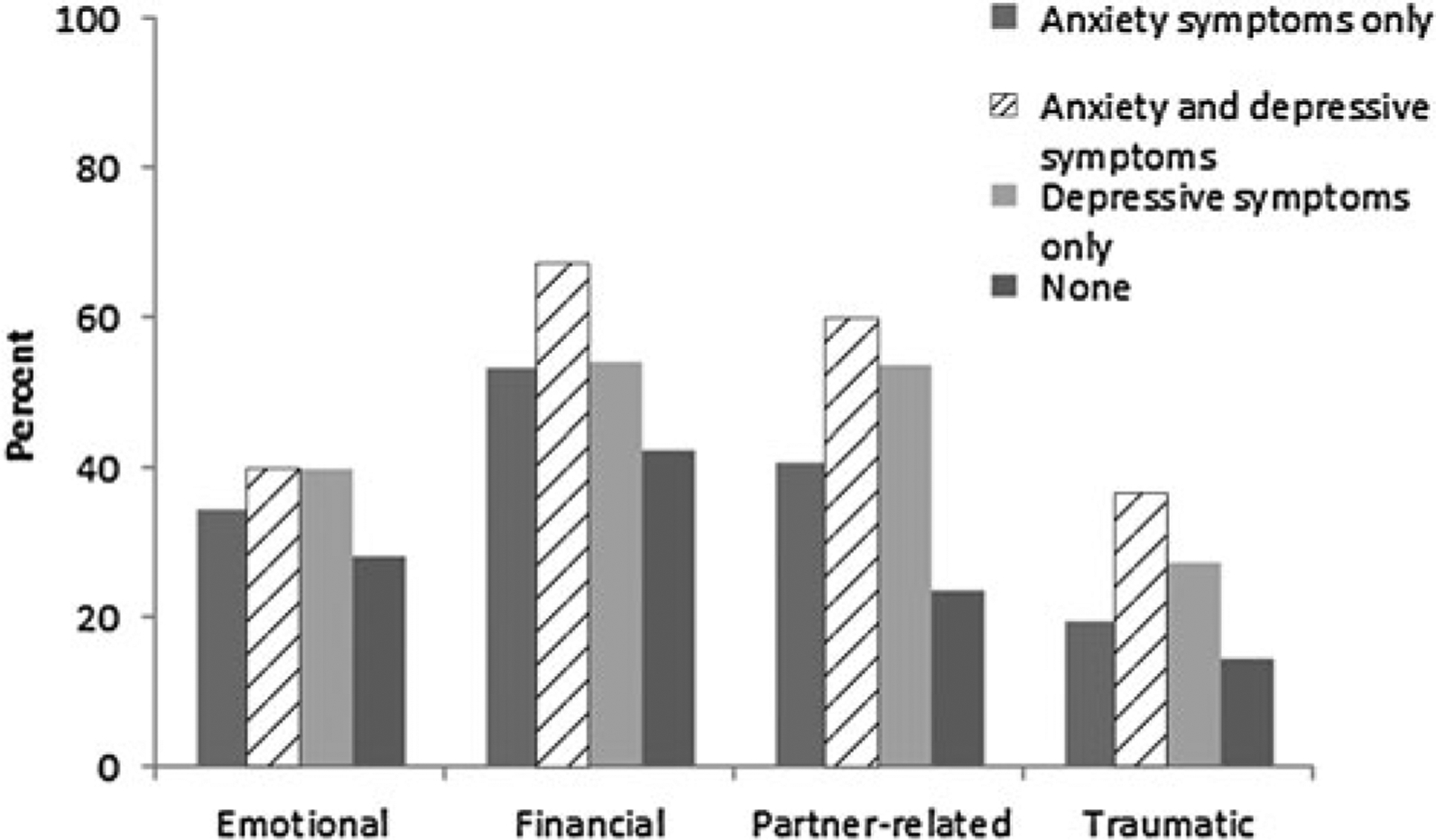

We found that prevalence of type of stressor (emotional, financial, partner-related, and traumatic) varied by women’s anxiety and/or depressive symptoms (Fig. 1). Women with postpartum anxiety and comorbid depressive symptoms had the highest prevalence of financial (67.0%), partner-related (59.7%), and traumatic (36.4%) stressful life events during pregnancy. Women with comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms (39.9%) and depressive symptoms only (39.9%) had similarly high prevalence of emotional stressful life events. Women with anxiety symptoms only had intermediary levels of prevalence for emotional (34.5%), partner-related (40.5%), and traumatic (19.5%) stressful life events.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of women reporting types of prenatal stressful life events by postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Maryland and Illinois, 2009–2010. *Chi square p-value < 0.05.

In the multivariable model, higher numbers of stressors during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] range: 1.3–9.7) and delivering an infant at ≤ 27 weeks gestation (aOR range: 2.0–5.7) were associated with all three mental health categories (Table 3). Women reporting postpartum anxiety symptoms only were more likely to be smokers (aOR = 2.3), Medicaid beneficiaries (aOR = 1.7), and have pre-existing diabetes (aOR = 2.0); they were less likely to have household incomes from $15,000 to under $50,000 (aOR = 0.6). Women reporting postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms were more likely to smoke throughout pregnancy (aOR = 2.9) and to have had a cesarean delivery (aOR = 1.9). Women more likely to report postpartum depressive symptoms only were overweight and obese (aOR = 1.7), drank ≥ 7 alcoholic drinks per week before pregnancy (aOR = 3.2), and had small for gestational age infants (aOR = 2.1). Similar associations were seen in a sensitivity analysis when we defined postpartum anxiety symptoms as a score ≥ 8 and postpartum depressive symptoms as a score ≥ 12.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Associations Between Maternal Demographic and Pregnancy Characteristics and Postpartum Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, Illinois and Maryland, 2009–2010

| Postpartum anxiety symptoms only | Postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms | Postpartum depressive symptoms only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aORa | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Income | ||||||

| < $10,000 and $10,000–$14,999 | 0.7 | (0.4–1.1) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.3) | 1.1 | (0.5–2.4) |

| $15,000–$49,999 | 0.6 | (0.4–0.8) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.9) | 0.5 | (0.3–1.0) |

| $50,000 + | 1 | s | 1 | 1 | ||

| Missing | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.3) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.7) |

| Prepregnancy BMI | ||||||

| Underweight | 1.0 | (0.7–1.6) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.7) | 0.4 | (0.2–1.3) |

| Normal weight | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Overweight and obese | 1.0 | (0.8–1.4) | 0.7 | (0.5–1.1) | 1.7 | (1.0–2.8) |

| Missing | 0.7 | (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 | (0.3–1.8) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.6) |

| Prepregnancy alcoholic drinks/week | ||||||

| 1–6 | 1.3 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.9–2.1) | 1.6 | (1.0–2.7) |

| ≥7 | 1.1 | (0.5–2.3) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.4) | 3.2 | (1.2–8.5) |

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Medicaid coveredb | ||||||

| Medicaid | 1.7 | (1.1–2.5) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) |

| Non-Medicaid | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| No. of stressful life events during pregnancy | ||||||

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1–2 | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 2.0 | (1.1–3.6) | 2.9 | (1.4–6.3) |

| 3–5 | 2.2 | (1.5–3.1) | 4.8 | (2.6–8.7) | 5.5 | (2.4–12.8) |

| 6–13 | 2.0 | (1.1–3.7) | 9.7 | (4.6–20.8) | 8.1 | (2.8–24.0) |

| Smoking status during pregnancy | ||||||

| Nonsmoker and quit | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Smoker | 2.3 | (1.6–3.4) | 2.9 | (1.8–4.8) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.7) |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Pre-existing diabetes | 2.0 | (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 | (0.3–2.7) | 1.0 | (0.2–4.3) |

| Gestational diabetes | 1.0 | (0.6–1.5) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.4) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) |

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | ||||||

| ≤ 27 | 2.0 | (1.0–3.7) | 5.7 | (3.1–10.5) | 4.3 | (1.8–10.4) |

| 28–33 | 1.2 | (0.7–2.0) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.5) | 1.4 | (0.7–2.8) |

| 34–36 | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 1.6 | (0.9–2.7) | 1.5 | (0.7–3.2) |

| ≥ 37 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Infant birthweight | ||||||

| Small for gestational age | 0.6 | (0.4–1.0) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.4) | 2.1 | (1.1–3.8) |

| Normal weight and large for gestational age | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Cesarean | 1.0 | (0.8–1.3) | 1.9 | (1.3–2.7) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.3) |

| Vaginal | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

Odds ratios are adjusted for all variables presented in the table and state of residence.

Medicaid coverage during prenatal care and/or delivery.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

In this population-based sample of postpartum women from Maryland and Illinois, we found that 18% of women reported experiencing postpartum anxiety symptoms since the birth of their child, and one third of them reported comorbid depressive symptoms. The 6.3% of women experiencing comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms were those with the highest mean anxiety and depressive symptoms. A higher number of stressors during pregnancy, delivering an infant at ≤ 27 weeks gestation and smoking throughout pregnancy were associated with reporting postpartum anxiety, alone or with comorbid depressive symptoms. Other characteristics differed by type of symptoms reported (anxious or depressive) and report of one or both types of symptoms.

Our period prevalence estimate of 18% for nonspecific postpartum anxiety symptoms in the time since their baby’s birth is difficult to compare to other studies using different sampling methods and screening and diagnostic tools. In a nationally representative study from 2001 to 2002, Vesga-Lopez et al.6 found that 12.3% of women up to 1 year postpartum had anxiety based on the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV). However, no information was provided on comorbid depression among these women. In a hospital-based sample of mostly white, educated, postpartum women from Pennsylvania, Paul et al.3 used the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and found a 17% prevalence of postpartum anxiety at the delivery hospitalization, which declined to 7% by 6 months postpartum. Stuart et al.4 found a point prevalence for nonspecific postpartum anxiety, measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory, at 9% at 14 weeks postpartum and 17% at 30 weeks postpartum in a community sample of married mothers with full-term infants born in Iowa. In a community sample of women at 8 weeks postpartum, 8.2% met the criteria for syndromal generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and 20% met the criteria for subsyndromal GAD.5 In a clinical sample of postpartum women, 11% screened positive for OCD symptoms at 2 weeks postpartum and at 6 months postpartum, the large majority of which had mild OCD symptoms.8 In an national sample of mothers 1 to 12 months postpartum, 9% met all criteria for PTSD.7 Our sample was representative of women having live births in Maryland and Illinois from 2009 to 2010 and who were 16 weeks postpartum on average at survey completion. Our sample was more diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status than the studies using community or hospital-based samples. Regardless of the differences between this study and others, prevalence estimates for postpartum anxiety symptoms are substantial, at 8% to 20%.

Six percent of women in our sample reported both postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms. Similar to the literature on adults in the general population,15 women in our sample with comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms had more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms than those screening positive for a single condition. Approximately 35% of women with postpartum anxiety symptoms also reported postpartum depressive symptoms and 64% with postpartum depressive symptoms also reported postpartum anxiety symptoms. Other studies have also found a strong correlation between depression and general anxiety4,5,22,23 or PTSD7 in postpartum women as well as the general adult population.24 In the general adult population, adults with depression are 5.1 times as likely as nondepressed adults to have a concurrent anxiety disorder and adults with a diagnosed anxiety disorder are 12 times as likely as those without to develop major depressive disorder over 12 months.24 Therefore, when a woman has a current or past history of anxiety or depression, screening for the other condition may be warranted. Clinicians who use the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to screen their patients for postpartum depression can examine three anxiety-specific questions on the EPDS to screen simultaneously for anxiety.4 Psychosocial screening instruments may also be used to screen for anxiety.25

Mothers with infants born at ≤ 27 weeks gestation had two to six times the prevalence of postpartum anxiety and/or depressive symptoms as mothers with term infants and just under half reported either anxiety or depressive symptoms. Since ours is a cross-sectional study and onset of the anxiety and depressive symptoms is unknown, temporality of the association is unknown. Based on previous literature, it is likely both a cause as well as an outcome of poor maternal mental health. Prenatal anxiety, prenatal depression, and use of antidepressants have been associated with preterm birth in some, but not all studies.26–29 Conversely, having a preterm infant may trigger anxious or depressive symptoms in mothers.30 Regardless of the temporality of the association, parents of infants with health issues should be monitored for anxiety and depression and offered supportive services. Successful interventions exist to reduce anxiety and depression among parents of infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit, many of whom are born preterm.31

A strong, dose–response relationship was found between experiencing an increased number of stressors during pregnancy and reporting comorbid postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms. Approximately 58% of women reporting postpartum anxiety with comorbid depressive symptoms experienced three or more stressors during pregnancy. The association between stressful experiences and postpartum depression is well established.2 Assessing psychosocial stressors in pregnant women, connecting those in need to social services, and teaching relaxation strategies may help mitigate stress when an adverse life event occurs.32

Smoking throughout pregnancy was associated with reporting postpartum anxiety symptoms, with approximately 39% of women who smoked throughout pregnancy reporting anxiety symptoms, with or without comorbid depressive symptoms. In the general population, adults with GAD, panic disorder, and PTSD are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to smoke.33 In our analysis, smokers were 2 to 3 times more likely to experience postpartum anxiety symptoms. Successful smoking cessation interventions exist to help adults with mental health disorders,34 including pregnant women,35 quit smoking. However, more research is needed on preventing relapse, which may be more likely among women with postpartum anxiety and depression.36

Over 20% of women with preexisting diabetes reported postpartum anxiety symptoms, and they were twice as likely to report anxiety symptoms than women with no history of diabetes. In the general adult population, independent bidirectional associations exist between depression and diabetes.37 Additionally, Kozhimannil et al.38 found an association between prepregnancy or gestational diabetes and perinatal depression in a New Jersey Medicaid population. More research is needed to examine the relationship between diabetes and perinatal anxiety.

This study has some limitations. The data are cross-sectional, self-reported, and from two states, Maryland and Illinois. Temporality of the associations is unknown. We were limited in what obstetric and pregnancy-related data were available on the survey and birth certificate, and we were unable to examine potentially associated characteristics such as emergency cesarean delivery, social support, prenatal depression and anxiety, and quality of sleep. Approximately 4% of women were missing data on anxiety and depressive symptoms, and 5% of women were excluded from the multivariable model. The sensitivity and specificity of the postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms screening questions are less than 100%, but are comparable to other validated screening instruments.20 When using cut-points for postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms with higher specificity, associations with maternal and infant characteristics remained. Additionally, we were unable to differentiate between different forms of depression or anxiety. General-izability of the findings outside of Maryland and Illinois may be limited, although in a report on postpartum depressive symptoms using 2004–2005 data, associations between maternal characteristics and postpartum depressive symptoms did not vary appreciably between the 17 states examined.39 To understand causal associations between certain characteristics and anxiety symptoms, longitudinal studies are needed.

Conclusions

These findings, along with those from previous community and hospital-based studies, suggest there is a substantial percentage of women with postpartum anxiety, many of whom experience comorbid depressive symptoms. Smokers, women experiencing stressful life events, mothers of very preterm infants, and women with preexisting diabetes may be at increased risk of anxiety with or without comorbid depression. Given the possible adverse effects of postpartum anxiety on a woman’s health, maternal functioning, and infant health and development, clinicians should be aware of the substantial prevalence and comorbidity of postpartum anxiety and depression and facilitate identification, referral, and/or treatment when services are available to ensure proper care for women screening positive.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the PRAMS Working Group: Alabama—Izza Afgan, MPH; Alaska—Kathy Perham-Hester, MS, MPH; Arkansas—Mary McGehee, PhD; Colorado—Alyson Shupe, PhD; Connecticut—Jennifer Morin, MPH; Delaware—George Yocher, MS; Florida—Avalon Adams-Thames, MPH, CHES; Georgia—Chinelo Ogbuanu, MD, MPH, PhD; Hawaii—Emily Roberson, MPH; Illinois—Theresa Sandidge, MA; Iowa—Sarah Mauch, MPH; Louisiana—Amy Zapata, MPH; Maine—Tom Patenaude, MPH; Maryland—Diana Cheng, MD; Massachusetts—Emily Lu, MPH; Michigan—Cristin Larder, MS; Minnesota—Judy Punyko, PhD, MPH; Mississippi—Brenda Hughes, MPPA; Missouri—Venkata Garikapaty, MSc, MS, PhD, MPH; Montana—JoAnn Dotson; Nebraska—Brenda Coufal; New Hampshire—David J. Laflamme, PhD, MPH; New Jersey—Lakota Kruse, MD; New Mexico—Eirian Coronado, MPH; New York State—Anne Radigan-Garcia; New York City—Candace Mulready-Ward, MPH; North Carolina—Kathleen Jones-Vessey, MS; North Dakota—Sandra Anseth; Ohio—Connie Geidenberger PhD; Oklahoma—Alicia Lincoln, MSW, MSPH; Oregon—Kenneth Rosenberg, MD, MPH; Pennsylvania—Tony Norwood; Rhode Island—Sam Viner-Brown, PhD; South Carolina—Mike Smith, MSPH; Texas—Rochelle Kingsley, MPH; Tennessee—David Law, PhD; Utah—Lynsey Gammon, MPH; Vermont—Peggy Brozicevic; Virginia—Marilyn Wenner; Washington—Linda Lohdefinck; West Virginia—Melissa Baker, MA; Wisconsin—Katherine Kvale, PhD; Wyoming—Amy Spieker, MPH; CDC PRAMS Team, Applied Sciences Branch, Division of Reproductive Health. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50:275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hara MW. Postpartum depression: what we know. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1258–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul IM, Downs DS, Schaefer EW, Beiler JS, Weisman CS. Postpartum anxiety and maternal-infant health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1218–e1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, O’Hara MW, Gorman L. Postpartum anxiety and depression: onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:420–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenzel A, Haugen EN, Jackson LC, Brendle JR. Anxiety symptoms and disorders at eight weeks postpartum. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65: 805–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck CT, Gable RK, Sakala C, Declercq ER. Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: results from a two-stage U.S. national survey. Birth. 2011;38:216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller ES, Chu C, Gollan J, Gossett DR. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms during the postpartum period. A prospective cohort. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:115–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman R, Granat A, Pariente C, Kanety H, Kuint J, Gilboa-Schechtman E. Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand SR, Brennan PA. Impact of antenatal and postpartum maternal mental illness: how are the children? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:441–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin MP, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Priest SR, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in the postpartum period: how prevalent are they and can we improve their detection? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenzel A, Haugen EN, Jackson LC, Brendle JR. Anxiety symptoms and disorders at eight weeks postpartum. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: protocol development and initial outcome data. Cogn Behav Pract. 2010;17:88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschfeld RM. The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: recognition and management in primary care. Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3: 244–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee Opinion No. 453: Screening for depression during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:394–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earls MF. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller RL, Pallant JF, Negri LM. Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Watson D, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D’Angelo D. Brief scales to detect postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012; 21:1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahluwalia IB, Merritt R, Beck LF, Rogers M. Multiple lifestyle and psychosocial risks and delivery of small for gestational age infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin MP, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Leader L, Saint K, Parker G. Maternal trait anxiety, depression and life event stress in pregnancy: relationships with infant temperament. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004; 80:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald S, Wall J, Forbes K, et al. Development of a prenatal psychosocial screening tool for post-partum depression and anxiety. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:189–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonari L, Bennett H, Einarson A, Koren G. Risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:37–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibanez G, Charles MA, Forhan A, et al. Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy and neonatal outcome: data from the EDEN mother-child cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vigod SN, Villegas L, Dennis CL, Ross LE. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review. BJOG. 2010;117:540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melnyk BM, Crean HF, Feinstein NF, Fairbanks E. Maternal anxiety and depression after a premature infant’s discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit: explanatory effects of the creating opportunities for parent empowerment program. Nurs Res. 2008;57:383–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobel CJ, Goldstein A, Barrett ES. Psychosocial stress and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:333–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cinciripini PM, Blalock JA, Minnix JA, et al. Effects of an intensive depression-focused intervention for smoking cessation in pregnancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park ER, Chang Y, Quinn V, et al. The association of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms and postpartum relapse to smoking: a longitudinal study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2383–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozhimannil KB, Pereira MA, Harlow BL. Association between diabetes and perinatal depression among low-income mothers. JAMA. 2009;301:842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prevalence of self-reported postpartum depressive symptoms—17 states, 2004–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]