Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of the study was to provide national prevalence, patterns, and correlates of marijuana use in the past month and past 2–12 months among women of reproductive age by pregnancy status.

STUDY DESIGN:

Data from 2007–2012 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, a cross-sectional nationally representative survey, identified pregnant (n = 4971) and nonpregnant (n = 88,402) women 18–44 years of age. Women self-reported marijuana use in the past month and past 2–12 months (use in the past year but not in the past month). χ2 statistics and adjusted prevalence ratios were estimated using a weighting variable to account for the complex survey design and probability of sampling.

RESULTS:

Among pregnant women and nonpregnant women, respectively, 3.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.2–4.7) and 7.6% (95% CI, 7.3–7.9) used marijuana in the past month and 7.0% (95% CI, 6.0–8.2) and 6.4% (95% CI, 6.2–6.6) used in the past 2–12 months. Among past-year marijuana users (n = 17,934), use almost daily was reported by 16.2% of pregnant and 12.8% of nonpregnant women; and 18.1% of pregnant and 11.4% of nonpregnant women met criteria for abuse and/or dependence. Approximately 70% of both pregnant and nonpregnant women believe there is slight or no risk of harm from using marijuana once or twice a week. Smokers of tobacco, alcohol users, and other illicit drug users were 2–3 times more likely to use marijuana in the past year than respective nonusers, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

CONCLUSION:

More than 1 in 10 pregnant and nonpregnant women reported using marijuana in the past 12 months. A considerable percentage of women who used marijuana in the past year were daily users, met abuse and/or dependence criteria, and were polysubstance users. Comprehensive screening, treatment for use of multiple substances, and additional research and patient education on the possible harms of marijuana use are needed for all women of reproductive age.

Keywords: correlates, dependence, marijuana, pregnant, prevalence

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit substance under federal law among individuals older than 12 years of age in the United States.1 Some studies have reported associations between marijuana use and adverse birth outcomes such as low birthweight and preterm birth,2–4 whereas other studies have not.5–7 As of July 2014, 23 states and the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana in either medical and/or recreational form.8 Higher rates of marijuana use in the general population have been documented in states with legalized medical marijuana.9 Therefore, it is important to examine marijuana use prevalence and characteristics of pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age who use marijuana.

The most recent national estimates of marijuana use among women of reproductive age, 18–44 years of age, were published in 2009 using data from 2002–200610 and 2002–2007.11 Both studies examined the prevalence of past-month marijuana use among pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Past-month marijuana use was highest among nonpregnant women without children (7.3%10 and 10.9%11), followed by postpartum women and nonpregnant women with children (range, 3.8–5.3%, dependent on the child’s age) and pregnant women (range, 1.4–4.6%, dependent on trimester).10,11 However, national prevalence estimates have not been updated with more recent data. Furthermore, the prevalence of use prior to the past month, which may be reflective of preconception use among pregnant women has not been examined.

Additionally, frequency of use, marijuana abuse and/or dependence, and use of other substances in addition to marijuana are unknown. Thus, the objective of this study was to provide national prevalence estimates of marijuana use in the past month and in the past 2–12 months among women of reproductive age by pregnancy status, using data from 2007–2012. Additionally, we sought to describe correlates of marijuana use, prevalence of marijuana abuse and/or dependence, frequency of use, and women’s attitudes toward use by pregnancy status.

Materials and Methods

Data source and sample

We used combined public use data from the 2007–2012 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). The NSDUH is a cross-sectional survey designed to estimate prevalence and correlates of substance use in US household populations aged 12 years or older. The NSDUH samples the civilian, noninstitutionalized population using multistage area probability sampling. Within each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, census tracts and area segments were used to randomly sample households.12–16

The NSDUH uses a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing conducted by an interviewer and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing, which is designed to provide respondents a private and confidential means of responding to questions regarding illicit drug use and other sensitive behaviors.12–16 Weighted interview response rates for 2007–2012 ranged from 73.0% to 75.5%, with an overall response rate of 74.3%.12–16 Detailed information about the sampling and survey methodology can be found elsewhere.12–16

Our analyses used deidentifiable public-use data; thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Review Board deemed the study as research not involving human subjects and exempt from review. The combined 2007–2012 data yielded 93,878 female respondents aged 18–44 years. Of these, 93,373 women (99.5%) reported data on pregnancy status at the time of interview, and all of them had complete information on recent use of marijuana use.

Measures

Marijuana use

The NSDUH captured marijuana use including hashish, a form of marijuana, regardless of consumption method, with 2 questions: “Have you ever, even once, used marijuana or hashish?” and, if yes, “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” Individuals were defined as past-month users (respondents who used marijuana in the past month), users in past 2–12 months (respondents who used in the past year but not the past month), and nonusers in the past year (respondents who did not use any marijuana in the past 12 months). Nonusers in the past year included women who never used marijuana and those who used marijuana previously but not in the past year.

The NSDUH also assesses whether a respondent meets marijuana abuse or dependence criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) in the past year.17 DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse is met if 1 or more of the following is exhibited during a 12-month period: failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home; frequent use of substances in which it is physically hazardous; frequent or recurrent legal problems; and continued use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems.

DSM-IV criteria for dependence is met if 3 or more of the following are exhibited during a 12-month period: tolerance; withdrawal symptoms; use of substance in larger amounts or over a longer period; persistent desire to cut down or control substance use; involvement in chronic behavior to obtain the substance; reduction or abandonment of social, occupational or recreational activities; or use of substance, regardless of persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by the substance.17

Pregnancy and sociodemographic characteristics

Women self-reported their pregnancy status and trimester of pregnancy at the time of the interview. Demographic variables included the following: self-reported age in years (18–25, 26–34, or 35–44); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African-American, Hispanic, and other); education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, or college or more); employment (full time, part time, unemployed, and other [ie, disabled, keeping house full time, in school/training, or retired]); annual family income (<$20,000, $20,000–49,999, $50,000–74,999, or ≥$75,000); marital status (married; widowed, divorced, or separated; or never been married); and health insurance (private insurance; public insurance: Medicaid, Medicare, TRICARE, CHAMPUS, CHAMPVA, the Veterans Affairs, or military health insurance; or uninsured).

Other substance use

Smoking tobacco in the past year was defined as nonsmokers (respondents who did not smoke tobacco in the past year), tobacco smokers in the past 2–12 months (respondents who smoked tobacco in the past year but not the past month), and past-month tobacco smokers. Alcohol use in the past month was categorized as heavy use (drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on each of ≥5 days in the past 30 days); binge but not heavy (drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days); past-month use but not binge or heavy; and no use. Other illicit drug use included hallucinogens, heroin, cocaine, inhalants, and any psychotherapeutics.

Pattern of marijuana use and attitudes toward use

The NSDUH asks respondents their age of initiation of marijuana use and frequency of use in the past 12 months, which was categorized to match previous NSDUH reports (1–11, 12–49, 50–99, 100–299, and ≥300 days).18 Respondents were also asked about their method of obtaining their last used marijuana, the source of last bought marijuana, and difficulty of buying marijuana. Additionally, respondents were asked about the perceived risk of harm (physical and other ways) when they smoke marijuana once a month and once or twice a week (response options: great, moderate, slight, and no risk).

Statistical analyses

Prevalence of marijuana use in the past month and past 2–12 months was estimated by pregnancy status and by trimester among pregnant women. χ2 tests were conducted to assess the differential distribution of sociodemographic characteristics by marijuana use status among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Among past-year users of marijuana (ie, past month and past 2–12 months combined), χ2 tests were also conducted to assess differential distributions of patterns and attitudes toward use of marijuana by pregnancy status.

Separate multivariable general linear models with Poisson distribution were used to estimate the adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) of using marijuana in the past year among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, respectively. We first ran adjusted prevalence ratio models including sociodemographic variables of interest. We next examined the independent associations between past-year marijuana use and past-year tobacco smoking status, alcohol use in the past month, and other illicit drug use in the past year by fitting models adjusted for sociodemographic variables.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and included a weighting variable to account for the complex survey design and probability of sampling.

Results

Prevalence of marijuana use

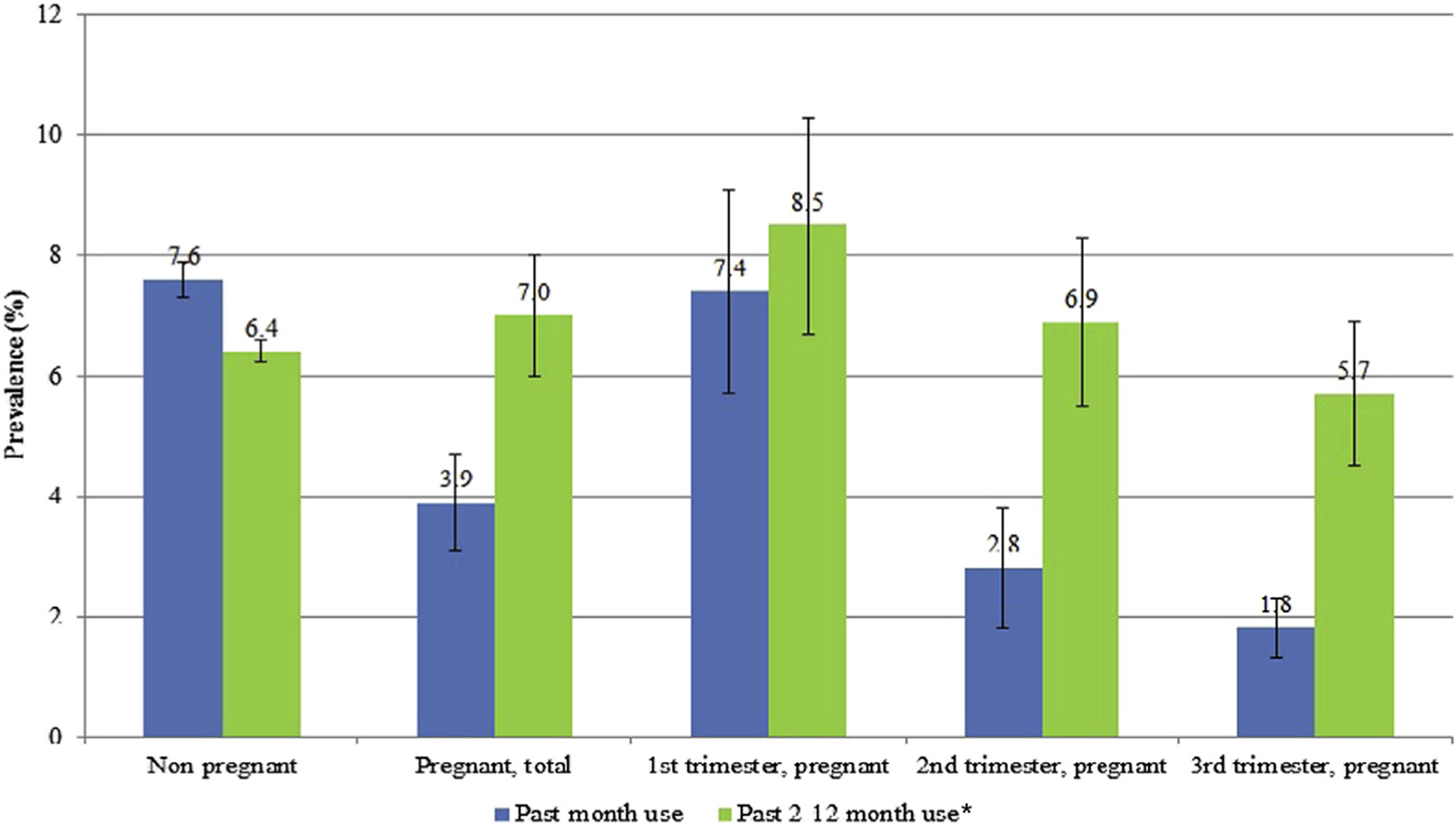

Among pregnant women, 3.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.2–4.7) used marijuana in the past-month and 7.0% (95% CI, 6.0–8.2) used it in the past 2–12 months (Figure 1), totaling 10.9% in the past year. Among pregnant women, past-month use was highest among those in their first trimester (7.4%, 95% CI, 5.7–9.5) and lowest among those in their third trimester (1.8%, 95% CI, 1.3–2.5). Among nonpregnant women, 7.6% (95% CI, 7.3–7.9) used marijuana in the past month and 6.4% (95% CI, 6.2–6.6]) used marijuana in the past 2–12 months, totaling 14.0% in the past year.

FIGURE 1. Prevalence of marijuana use among women of reproductive age.

National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2007–2012 (N = 93,373).

Asterisk indicates past 2–12 month use defined as use in the past year but not in the past month.

Ko. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Characteristics of pregnant and nonpregnant women by marijuana use

Among both pregnant and nonpregnant women, a higher percentage of women who used marijuana in the past month and past 2–12 months, compared with nonusers, were 18–25 years of age, unemployed, earned less than $20,000 annually, and never married (Table 1). Among both pregnant and nonpregnant women, past-month users were more likely to be uninsured than nonusers.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of pregnant and nonpregnant marijuana users

| Pregnant (n = 4971) | Nonpregnant (n = 88,402) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Past-month users % (95% CI) (n = 265) | Past 2–12 month usersa % (95% CI) (n = 520) | Nonusers in past year % (95% CI) (n = 4186) | Past-month users % (95% CI) (n = 9514) | Past 2–12 month users % (95% CI) (n = 7635) | Nonusers in past year % (95% CI) (n = 71,253) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–25 | 66.7 (55.4–76.4) | 65.2 (56.7–72.7) | 35.0 (32.8–37.2) | 54.8 (53.0–56.6) | 53.1 (51.3–54.8) | 25.6 (25.1–26.1) |

| 26–34 | 29.1 (20.0–40.2) | 25.6 (18.8–33.7) | 52.3 (49.7–54.9) | 27.4 (25.6–29.3) | 28.2 (26.6–29.9) | 32.5 (31.9–33.2) |

| 35–44 | 4.2 (0.9–16.7) | 9.2 (4.9–16.6) | 12.7 (11.3–14.4) | 17.8 (16.3–19.4) | 18.7 (17.0–20.5) | 41.9 (41.2–42.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 55.1 (44.6–65.2) | 55.9 (49.1–62.4) | 59.5 (57.1–61.8) | 67.9 (66.3–69.4) | 68.1 (66.6–69.6) | 59.0 (58.4–59.7) |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 29.4 (20.7–39.9) | 19.9 (15.1–25.8) | 12.6 (11.2–14.1) | 15.5 (14.1–17.0) | 12.9 (11.8–14.2) | 13.8 (13.4–14.2) |

| Hispanic | 13.1 (7.3–22.1) | 16.6 (11.6–23.2) | 19.5 (17.5–21.5) | 11.6 (10.5–12.8) | 13.0 (11.8–14.3) | 18.7 (18.1–19.2) |

| Other | 2.5 (1.6–3.9) | 7.5 (4.7–12.0) | 8.5 (7.0–10.3) | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 6.0 (5.1–7.0) | 8.5 (8.1–9.0) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 22.3 (16.1–29.9) | 19.8 (15.4–25.0) | 15.3 (14.1–16.6) | 14.5 (13.4–15.8) | 26.1 (24.3–28.0) | 12.6 (12.2–13.0) |

| High school | 39.9 (29.6–51.2) | 40.7 (35.4–46.2) | 25.7 (23.7–27.7) | 30.1 (28.7–31.5) | 35.7 (33.7–37.8) | 26.6 (26.1–27.1) |

| Some college | 27.1 (17.7–39.1) | 25.3 (20.3–31.0) | 24.9 (23.0–27.1) | 35.6 (34.1–37.1) | 27.2 (25.7–28.8) | 29.6 (29.0–30.2) |

| College or more | 10.7 (4.4–23.8) | 14.3 (9.8–20.4) | 34.0 (31.4–36.8) | 19.8 (18.4–21.3) | 11.0 (9.8–12.3) | 31.2 (30.6–31.8) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Full time | 35.7 (26.5–46.2) | 35.1 (29.6–41.0) | 41.8 (39.4–44.3) | 42.2 (40.6–43.9) | 46.1 (44.0–48.2) | 51.1 (50.5–51.8) |

| Part time | 20.6 (14.2–29.1) | 20.4 (15.5–26.2) | 17.1 (14.9–19.6) | 27.6 (26.1–29.2) | 26.3 (24.7–28.0) | 19.9 (19.5–20.4) |

| Other | 27.0 (19.6–36.0) | 30.0 (23.7–37.1) | 35.6 (33.3–38.0) | 19.8 (18.6–21.0) | 17.6 (16.1–19.1) | 22.9 (22.4–23.3) |

| Unemployed | 16.6 (11.1–24.1) | 14.6 (9.8–21.0) | 5.5 (4.6–6.5) | 10.4 (9.5–11.4) | 10.1 (8.8–11.5) | 6.1 (5.8–6.4) |

| Income | ||||||

| ≥$75,000 | 12.0 (7.0–19.7) | 10.4 (7.4–14.4) | 30.6 (28.3–33.1) | 19.9 (18.3–21.6) | 24.1 (22.3–26.0) | 29.4 (28.7–30.2) |

| $50,000–74,999 | 13.2 (6.8–24.1) | 14.5 (10.0–20.6) | 17.9 (16.2–19.7) | 13.8 (12.6–15.2) | 14.7 (13.5–16.1) | 17.7 (17.2–18.1) |

| $20,000–49,999 | 34.2 (25.1–44.5) | 39.7 (33.4–46.5) | 30.2 (27.8–32.7) | 33.5 (31.9–35.1) | 33.5 (31.9–35.2) | 32.3 (31.8–32.9) |

| <$20,000 | 40.7 (31.4–50.7) | 35.4 (29.5–41.7) | 21.3 (19.4–23.4) | 32.8 (31.0–34.6) | 27.7 (26.3–29.2) | 20.6 (20.1–21.2) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 19.2 (11.7–29.8) | 22.1 (16.3–29.3) | 66.1 (63.8–68.3) | 18.6 (17.1–20.1) | 20.0 (18.2–21.8) | 49.9 (49.2–50.6) |

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 10.4 (4.4–22.7) | 13.8 (9.5–19.7) | 5.9 (5.0–7.0) | 10.4 (9.3–11.6) | 10.6 (9.2–12.2) | 12.1 (11.7–12.6) |

| Never married | 70.4 (58.2–80.3) | 64.1 (57.2–70.5) | 27.9 (26.0–30.1) | 71.1 (69.4–72.7) | 69.4 (67.6–71.1) | 38.0 (37.3–38.6) |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Uninsured | 23.9 (15.3–35.3) | 8.1 (5.4–12.0) | 10.1 (8.7–11.8) | 25.1 (23.7–26.5) | 21.4 (19.9–22.9) | 20.0 (19.5–20.6) |

| Public | 44.3 (35.4–53.6) | 58.4 (52.2–64.3) | 34.9 (32.9–36.9) | 20.7 (19.4–22.1) | 16.9 (15.4–18.4) | 16.1 (15.6–16.6) |

| Private | 31.8 (22.0–43.6) | 33.6 (27.6–40.1) | 55.0 (52.6–57.4) | 54.2 (52.6–55.8) | 61.8 (59.6–63.9) | 63.9 (63.2–64.6) |

| Tobacco smoking in past year | ||||||

| Smoker in past mo | 60.0 (50.0–69.3) | 35.9 (30.3–42.1) | 11.8 (10.4–13.2) | 66.0 (64.2–67.7) | 48.1 (46.3–50.0) | 22.8 (22.4–23.2) |

| Smoker in past 2–12 mos | 17.3 (11.2–25.7) | 32.1 (26.1–38.6) | 10.2 (8.9–11.7) | 8.1 (7.3–9.0) | 12.6 (11.6–13.8) | 4.1 (3.9–4.4) |

| Nonsmoker | 22.7 (15.4–32.2) | 32.0 (25.6–39.2) | 78.0 (76.2e80.0) | 26.0 (24.4–27.6) | 39.2 (37.4–41.1) | 73.1 (72.6–73.5) |

| Alcohol use in past monthb | ||||||

| Heavy use | 7.2 (3.7–13.5) | 2.2 (0.9–5.4) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 22.4 (21.0–23.9) | 15.6 (14.3–17.1) | 3.4 (3.2–3.7) |

| Binge but not heavy | 16.9 (10.3–26.5) | 6.8 (3.7–12.1) | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | 39.1 (37.4–40.7) | 37.4 (35.3–39.4) | 17.3 (16.9–17.6) |

| Use but not binge or heavy | 16.6 (10.3–25.7) | 11.3 (7.5–16.8) | 5.3 (4.3–6.4) | 25.4 (23.9–26.9) | 29.3 (27.5–31.1) | 33.4 (32.8–34.0) |

| Did not use | 59.2 (49.0–68.7) | 79.7 (73.0–85.1) | 92.8 (91.5–93.9) | 13.2 (12.1–14.4) | 17.7 (16.3–19.1) | 45.9 (45.3–46.6) |

| Other illicit drug use in past yearc | ||||||

| User in past month | 17.2 (9.7–28.6) | 3.8 (2.2–6.6) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 24.7 (23.2–26.1) | 10.7 (9.6–11.8) | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) |

| User in past 2–12 months | 36.2 (26.0–47.8) | 22.8 (18.0–28.6) | 3.8 (3.0–4.7) | 22.9 (21.7–24.2) | 19.2 (17.8–20.6) | 3.8 (3.5–4.0) |

| Nonuser | 46.6 (36.6–57.0) | 73.4 (67.2–78.6) | 95.5 (94.5–96.3) | 52.5 (50.9–54.0) | 70.2 (68.6–71.7) | 94.1 (93.8–94.4) |

National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2007–2012 (N = 93,373).

CI, confidence interval.

Past 2–12 month use defined as use in the past year but not in the past month;

Binge alcohol use is defined as drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days; heavy alcohol use is defined as drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on each of ≥5 days in the past 30 days (all heavy alcohol users are also binge alcohol users);

Other illicit drugs include hallucinogens, heroin, cocaine, inhalants, and any psychotherapeutic agents.

Ko. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Among pregnant women, a higher percentage of past-month users were non-Hispanic African American (29.4%) compared with nonusers (12.6%). Among pregnant women, a higher percentage of past-month (44.3%) and past 2–12 month users (58.4%) had public insurance compared with nonusers (34.9%).

Among nonpregnant women, a higher percentage of past-month (67.9%) and past 2–12 month users (68.1%) were non-Hispanic white compared with nonusers (59.0%). Among both pregnant and nonpregnant women, a higher percentage of women who used marijuana in the past month and in the past 2–12 months, compared with nonusers, were tobacco smokers in the past month, heavy or binge drinkers in the past month, and users of other illicit drugs in the past month or in the past 2–12 months.

Correlates of past-year marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women

Among pregnant women, women with annual household incomes less than $50,000 were almost twice as likely to be past-year marijuana users compared with women with annual incomes greater than $75,000 (Table 2, P < .05). Pregnant divorced, separated, widowed, or never-married women were greater than 4 times as likely to be past-year marijuana users than married women.

TABLE 2.

Sociodemographic correlates of past-year pregnant and nonpregnant marijuana users

| Characteristic | Pregnant (n = 4971) aPR (95% CI)a | Nonpregnant (n = 88,402) aPR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Study year | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0)b |

| Age, y | ||

| 18–25 | 1.48 (0.8–2.6) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7)b |

| 26–34 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4)b |

| 35–44 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)b |

| Hispanic | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)b |

| Other | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.6 (0.5–0.6)b |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) |

| High school | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)b |

| Some college | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)b |

| College | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Part time | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)b |

| Other | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9)b |

| Unemployed | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3)b |

| Income | ||

| ≥$75,000 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| $50,000–74,999 | 1.5 (1.0–2.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| $20,000–49,999 | 1.7 (1.1–2.6)b | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| <$20,000 | 1.7 (1.0–2.7)b | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)b |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 4.5 (2.7–7.5)b | 2.0 (1.8–2.3)b |

| Never married | 4.2 (2.8–6.3)b | 2.6 (2.4–2.8)b |

| Health insurance | ||

| Uninsured | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2)b |

| Public | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

| Private | 1.0 | 1.0 |

National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2007–2012.

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

General linear models with Poisson distribution adjusted for all characteristics listed in table;

P < .05.

Ko. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Among nonpregnant women, 18–25 year olds (aPR, 1.5) and 26–34 year olds (aPR, 2.2) compared with 35–44 year olds, women with high school (aPR, 1.1) or some college education (aPR, 1.2) compared with college-educated, employed part time (aPR, 1.1), or unemployed (aPR, 1.2) compared with full-time employed women, women with annual household incomes less than $20,000 (aPR, 1.1) compared with greater than $75,000, divorced, separated, or widowed (aPR, 2.0) and never married (aPR, 2.6) women compared with married, and publicly insured or uninsured (aPR, 1.1) compared with privately insured women, were more likely to be past-year marijuana users. Among nonpregnant women, non-Hispanic African American women (aPR, 0.7), Hispanic women (aPR, 0.6), or women of other race/ethnicity (aPR, 0.6) were less likely to be past-year users than non-Hispanic white women.

Among pregnant women, past-month (aPR, 3.2) and past 2–12 month tobacco smokers (aPR, 3.4) were more likely than nonsmokers to be past-year marijuana users. Heavy (aPR, 1.8), binge (aPR, 1.9), and users of alcohol in the past month (aPR, 1.9) were more likely to be past-year marijuana users than women who did not drink alcohol (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Substance use correlates of past-year pregnant and nonpregnant marijuana users

| Characteristic | Pregnant (n = 4971) aPR (95% CI)a | Nonpregnant (n = 88,402) aPR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco smoking in past year | ||

| Smoker in past month | 3.2 (2.3–4.4)b | 2.3 (2.2–2.5)b |

| Smoker in past 2–12 mosc | 3.4 (2.4–4.6)b | 2.3 (2.1–2.5)b |

| Nonsmoker | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Alcohol use in past mod | ||

| Heavy alcohol use | 1.8 (1.1–2.9)b | 3.3 (3.0–3.6)b |

| Binge but not heavy use | 1.9 (1.3–2.7)b | 2.9 (2.6–3.1)b |

| Past month use but not binge or heavy | 1.9 (1.4–2.7)b | 2.1 (1.9–2.3)b |

| Did not use alcohol in past mo | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Other illicit drug use in past yeare | ||

| User in past month | 2.7 (2.0–3.7)b | 2.7 (2.4–2.9)b |

| User in past 2–12 mosc | 2.9 (2.3–3.7)b | 2.5 (2.4–2.7)b |

| Nonuser | 1.0 | 1.0 |

National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2007–2012.

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In addition to variables listed in table, general linear models with Poisson distribution adjusted for year, age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, marital status, and health insurance;

P < .05;

Defined as use in the past year but not the past month;

Binge alcohol use is defined as drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days; heavy alcohol use is defined as drinking ≥5 drinks on the same occasion on each of ≥5 days in the past 30 days (all heavy alcohol users are also binge alcohol users);

Other illicit drugs include hallucinogens, heroin, cocaine, inhalants, and any psychotherapeutics.

Ko. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Additionally, pregnant women who used other illicit drugs in the past month (aPR, 2.7) or past 2–12 months (aPR, 2.9) were more likely to be past-year marijuana users than women who did not. Similar associations were seen among nonpregnant women, although the strength of the associations were slightly weaker for tobacco use (past month: aPR, 2.3; past 2–12 months: aPR, 2.3) and slightly stronger for alcohol use (heavy: aPR, 3.3; binge: aPR, 2.9; any: aPR, 2.1) compared with the associations among pregnant women.

Patterns and attitudes toward marijuana use among past-year users

Among past-year marijuana users, the prevalence of women of reproductive age who met DSM-IV criteria for marijuana abuse and/or dependence differed among pregnant (18.1%) and nonpregnant (11.4%) women (P < .05; Table 4). A greater percentage of pregnant (36.0%) than nonpregnant (27.0%) past-year marijuana users reported the initiation of marijuana use at 14 years of age or younger (P < .05). A greater percentage of pregnant (31.4%) than nonpregnant (20.1%) past-year users used marijuana 100–299 days or about twice a week (P < .05). Another 16.2% of pregnant women and 12.8% of nonpregnant past-year users reported using marijuana almost daily (≥300 days in the past year, P < .05). Pregnant and nonpregnant women most commonly obtained marijuana by receiving it for free/sharing with others, and more than 75% of the last purchased marijuana was from a friend. Approximately 92% of both pregnant and nonpregnant past-year users reported that it is fairly or very easy to acquire marijuana. Almost 70% of both pregnant and nonpregnant past-year marijuana users perceived a slight or no risk of harm from using marijuana once a month or once or twice in 1 week.

TABLE 4.

Patterns and attitudes regarding marijuana use among past-year users

| Characteristic | Pregnant % (95% CI) (n = 785) | Nonpregnant % (95% CI) (n = 17,149) |

|---|---|---|

| PATTERNS OF USE | ||

| Meet DSM-IV criteria for marijuana abuse or dependencea | ||

| Yes | 18.1 (14.0–23.1) | 11.4 (10.7–12.1) |

| No | 81.9 (77.0–86.0) | 88.6 (87.9–89.3) |

| Age of initiation of marijuana use, ya | ||

| 14 or younger | 36.0 (30.7–41.7) | 27.0 (25.9–28.1) |

| 15–17 | 37.3 (32.6–42.2) | 41.5 (40.1–42.8) |

| 18 or older | 26.7 (22.0–32.0) | 31.6 (30.3–32.9) |

| Frequency of marijuana use in past 12 mos, da,b | ||

| 1–11 | 24.2 (21.1–27.6) | 38.9 (37.7–40.2) |

| 12–49 | 19.6 (15.6–24.3) | 19.1 (18.3–20.0) |

| 50–99 | 8.7 (5.9–12.5) | 9.1 (8.4–9.9) |

| 100–299 | 31.4 (26.3–36.9) | 20.1 (19.1–21.1) |

| ≥300 | 16.2 (12.3–21.1) | 12.8 (11.9–13.6) |

| Method of obtaining last used marijuanaa | ||

| Bought | 43.8 (38.5–49.2) | 33.0 (31.9–34.1) |

| Received for free/shared | 51.6 (46.1–57.1) | 63.1 (62.1–64.2) |

| Traded/grew it | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) |

| Method unspecified | 3.9 (1.6–9.2) | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) |

| Source of last marijuana boughtb | ||

| Friend | 78.2 (68.7–85.5) | 77.5 (74.6–80.2) |

| Relative | 10.6 (5.3–20.3) | 5.6 (4.2–7.5) |

| Someone just met/did not know | 7.1 (3.6–13.4) | 13.1 (11.0–15.5) |

| Source unspecified | 4.1 (1.2–12.9) | 3.8 (2.6–5.4) |

| ATTITUDES TOWARD MARIJUANA USE | ||

| Difficulty in acquiring marijuanab | ||

| Impossible or very difficult | 4.0 (1.9–8.0) | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) |

| Fairly difficult | 4.3 (2.4–7.6) | 5.8 (5.2–6.4) |

| Fairly or very easy | 91.7 (88.4–84.2) | 91.7 (90.9–92.5) |

| Perceived risk of marijuana use once a monthb | ||

| Great risk | 8.6 (6.0–12.1) | 5.8 (5.2–6.4) |

| Moderate risk | 12.8 (10.0–16.4) | 12.7 (11.8–13.7) |

| Slight risk | 41.5 (36.0–47.2) | 40.3 (39.0–41.6) |

| No risk | 37.2 (32.1–42.5) | 41.2 (39.9–42.5) |

| Perceived risk of marijuana use once or twice a weekb | ||

| Great risk | 8.4 (6.0–11.7) | 9.3 (8.4–10.2) |

| Moderate risk | 21.1 (16.9–25.9) | 21.1 (20.2–22.1) |

| Slight risk | 38.9 (33.2–44.9) | 39.3 (38.1–40.6) |

| No risk | 31.6 (26.8–36.9) | 30.3 (29.1–31.5) |

National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2007–2012 (n = 17,934).

CI, confidence interval.

χ2 P < .05 for differential distribution of variable by pregnancy status;

Because of small cell sizes, “do not know” responses were coded as missing (n = 551 for frequency; n = 54 for difficulty; n = 34 for risk in month; n = 54 for risk in a week).

Ko. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015.

Comment

We found that 10.9% of pregnant and 14.0% of nonpregnant US women of reproductive age used marijuana in the past year during 2007–2012, among whom 3.9% of pregnant and 7.6% of nonpregnant women used it in the past month. Among past-year marijuana users, almost daily use was reported by 16.2% of pregnant and 12.8% of nonpregnant women; and 18.1% of pregnant and 11.4% of nonpregnant women met criteria for abuse and/or dependence.

Among both pregnant and nonpregnant women, tobacco smokers, alcohol users, and other illicit drug users were 2–3 times more likely to use marijuana in the past year than respective nonusers, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Our past-month prevalence estimates for nonpregnant women were within the range of that reported by Muhuri and Gfroerer10 (7.3%) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration11 (10.9%) using data from 2002–2006 and 2002–2007.

Although our point estimate for past-month marijuana use among pregnant women is higher (3.9%) than the 2.8% previously reported by Muhuri and Gfroerer, the 95% confidence intervals of both estimates overlap, and we cannot conclude that the prevalence of past-month use has increased from 2002–2006 compared with our time period of 2007–2012. In agreement with previously published prevalence estimates, we also observed that prevalence of past-month marijuana use was highest among women in their first trimester and lowest among women in their third trimester of pregnancy. An additional 6–7% of women of reproductive age reported use of marijuana in the past 2–12 months. The prevalence of past-year use among women of reproductive age is of public health importance, given that approximately half of pregnancies are unintended, and unintended pregnancies are most common among the women of younger ages and lower income,19 groups more likely to use marijuana and other substances.

Among our sample of 18–44 year old pregnant and nonpregnant women who used marijuana in the past year, almost a third reported using marijuana before the age of 14 years. Additionally, almost half of pregnant and a third of nonpregnant past-year users reported using marijuana almost daily or twice a week. Existing literature indicates that younger age at initiation and regular use of marijuana are predictive of marijuana addiction.20,21

Among past-year marijuana users, we found that 18% of pregnant and 11% of nonpregnant women had met DSM-IV criteria for marijuana abuse and/or dependence. In a national study of US adults 18 years and older who were followed up for 3 years, the probability of transitioning from marijuana use onset to dependency was 7.1% after the first year of use and 8.9% for cumulative lifetime use.22

The point estimates for abuse and/or dependence observed in our study are higher than those observed in the aforementioned study; we included women meeting criteria for abuse in addition to dependence and no 95% confidence intervals were provided for the aforementioned study. Furthermore, we found that approximately 70% of pregnant women who used marijuana in the past year reported perceptions of slight or no risk of harm associated with using marijuana once or twice a week. The high frequency of weekly use and abuse/dependence among past-year marijuana users and the low perceived health risk of marijuana use by women in our sample are of clinical concern. Further research is needed to examine the risk of maternal marijuana use on infant outcomes.

Perhaps the most important finding of this study is that both pregnant and nonpregnant tobacco smokers, alcohol drinkers, and users of other illicit drugs were 2–3 times more likely to also use marijuana in the past year. The concurrent use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis during pregnancy has been documented by other studies.5,23

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the World Health Organization support universal screening for maternal substance use, including alcohol and illicit drug use.24–26 An ACOG survey reported that 97% of all obstetrician-gynecologists screen pregnant women for alcohol use27; however, it is unknown whether screening for illicit drugs is as common. Thus, single screening tools that identify multiple substances may aid substance use–cessation efforts during pregnancy. Furthermore, although evidence regarding the association between marijuana use and adverse infant outcomes is mixed,2–6 there is strong epidemio-logical evidence linking tobacco, alcohol, and some illicit drug use to poor outcomes such as low birthweight, fetal alcohol syndrome, and neonatal abstinence syndrome.28–30

The concurrent use of multiple substances is also important for preconception and interconception care among nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Thus, there is a need for comprehensive screening, assessment, and management of substance use for all women of reproductive age. In a study of first-time admissions in public and private substance abuse treatment centers, marijuana was the primary reported substance of use among 21% of pregnant women and 15% of nonpregnant women.31 However, treatment seeking for any substance use disorder is low, with only 17% of nonpregnant, 30% of pregnant, and 34% of postpartum women with drug use disorders self-reporting that they sought specialized treatment in the past year.32

There were a few study limitations. First, pregnancy status was self-reported at the time of the interview; on average, pregnant women in our sample were in their second trimester. Nonpregnant women who did not yet know that they were pregnant may have been misclassified. Furthermore, marijuana use in the past 2–12 months may not have occurred during pregnancy.

Second, marijuana and other substance use were self-reported and not validated with biological samples. Thus, our estimates may be an underestimate of the true prevalence of marijuana use among women of reproductive age. Pregnant women may be especially reluctant to disclose substance use, including marijuana use; moreover, differential reporting by state or women’s sociodemographic characteristics cannot be ruled out. However, the use of computer-assisted interviews in the NSDUH may have lessened this bias.33 Because the NSDUH samples the civilian noninstitutionalized population, results from this study are not generalizable to women of reproductive age who are incarcerated or in the military. Questions about perceived risk are not specific to risks of using marijuana during pregnancy.

Lastly, we were unable to examine state-based marijuana use because geographic information is excluded from NSDUH’s public-use data.

Strengths include the use of a nationally representative sample of women of reproductive age and the ability to examine marijuana abuse and/or dependence, frequency of use, and perceived risk of use, stratified by pregnancy status.

Findings from this study have clinical and public health implications. First, as states legalize the medical and/or recreational use of marijuana, it will be important to continuously monitor national and state trends in its use and examine its potential adverse effects on pregnancy. Second, ACOG, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the World Health Organization endorse universal perinatal substance use screening.24–26 Therefore, clinicians should be aware of the prevalence of marijuana use among their patients who are pregnant or at risk of becoming pregnant and have the training, tools, and resources to provide appropriate screening, patient education and care to women using or abusing marijuana, including comprehensive treatment for women also using other substances.

Footnotes

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings, NSDUH series H-46, HHS publication no. (SMA) 13–4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Northstone K; ALSPAC Study Team. Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome. BJOG 2002;109:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Mohandes A, Herman AA, Nabil El-Khorazaty M, Katta PS, White D, Grylack L. Prenatal care reduces the impact of illicit drug use on perinatal outcomes. J Perinatol 2003;23: 354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res 2012;71:215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Gelder MM, Reefhuis J, Caton AR, et al. Characteristics of pregnant illicit drug users and associations between cannabis use and perinatal outcome in a population-based study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;109:243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bada HS, Das A, Bauer CR, et al. Low birth weight and preterm births: etiologic fraction attributable to prenatal drug exposure. J Perinatol 2005;25:631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai A, Mark K, Terplan M. Marijuana use and pregnancy: prevalence, associated behaviors, and birth outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(Suppl 1):46S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Conference of State Legislatures. State medical marijuana laws. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx. Accessed Sept. 11, 2014.

- 9.Cerda M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;120:22–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC. Substance use among women: associations with pregnancy, parenting, and race/ethnicity. Matern Child Health J 2009;13:376–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: substance use among women during pregnancy and following childbirth. Rockville, MD; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: 2008 public use file and codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: 2009 public use file and codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: 2010 public use file and codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: 2011 public use file and codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: 2012 public use file and codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder [DSM IV], 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH series H-36, HHS publication no. SMA 09–4434). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health 2014;104(Suppl 1):S43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall W, Degenhardt L. Prevalence and correlates of cannabis use in developed and developing countries. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav 2009;34:319–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Quintero C, Perez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;115:120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW, D’Este CA, Stirling JM. Tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use during pregnancy: clustering of risks. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;134:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At-risk drinking and illicit drug use: ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. ACOG Committee opinion no. 422: Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1449–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudak ML, Tan RC. Committee on Drugs, Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics 2012;129:e540–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy. 2014; Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/pregnancy_guidelines/en/. Accessed Sept. 23, 2014. [PubMed]

- 27.Diekman ST, Floyd RL, Decoufle P, Schulkin J, Ebrahim SH, Sokol RJ. A survey of obstetrician-gynecologists on their patients’ alcohol use during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:756–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kocherlakota P Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics 2014;134:e547–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fetal alcohol syndrome—Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, and New York, 1995–1997. JAMA 2002;288:38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe JE, Arndt S. Demographic and substance abuse trends among pregnant and non-pregnant women: eleven years of treatment admission data. Matern Child Health J 2012;16: 1696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chromy JDT, Packer L, Gfroerer J. Mode effects on substance use measures: comparison of 1999 CAI and PAPI measures. In: Gfroerer LEE, Chromy J, eds. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2002. [Google Scholar]