Abstract

Purpose:

To explore the influences of the neighborhood environment on physical activity (PA) among people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a community with limited resources.

Methods:

Participants were adults with T2DM and their family members or friends who help in the management of T2DM and who were living in a low-income African American (AA) community. Healthcare providers working in the neighborhood were also included. Using an emergent design, qualitative data were collected through seven focus group discussions (N=63) and 13 in-depth interviews. Verbatim transcriptions were analyzed via thematic coding to explore contextual factors that limit PA, and to explore meaning around neighborhood features that promote or discourage PA.

Results:

Levels of PA were strongly limited by neighborhood insecurity and a lack of recreational facilities in the neighborhood. People with T2DM and physical/mobility disabilities were more affected by the neighborhood environment than those without disabilities, particularly due to perceived safety concerns and social stigma. Despite socio-economic inequalities within neighborhoods, participants showed resilience and made efforts to overcome social-environmental barriers to PA, applied various coping strategies and received social support.

Conclusions:

Results suggested that in an underserved neighborhood, individual barriers to physical activity were amplified by neighborhood-level factors like crime, especially among individuals who have T2DM and disabilities. Socio-economic inequalities should be addressed further to improve management of T2DM and its complications.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Physical activity, African American, Low-income neighborhood, Deprivation amplification

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death and affects approximately 30.3 million US adults.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common form of diabetes, and accounts for 90 to 95% of diagnosed cases.1 While individual factors, such as race, family history, and age, are major risk factors,1 contextual factors, such as the neighborhood environment, also fundamentally influence T2DM development and progression.2–4 Unhealthy behaviors, including lack of physical activity (PA) and poor eating habits, can also impact normal blood glucose maintenance and lead to complications.5

Place of residence is fundamental to disease occurrence and progression,6 constraining health behaviors and disease management.7 Within a residential area, social meanings are attached to neighborhood features and residents adapt to the neighborhood context.8 Therefore, to address health inequalities, the neighborhood context and dynamics between individuals and their environments need to be understood more deeply.

Low-income African American (AA) communities are characterized by food insecurity, neighborhood violence, and unsafe public spaces as well as high incidence and poor management of T2DM.9–11 Among neighborhood features affecting T2DM management in these communities, contextual factors influencing PA have been relatively neglected compared to the food environment or healthcare system. Further, most research on PA and neighborhood environments has used a quantitative approach,12,13 often failing to provide insight into the context and its social dynamics.

In this study, the concept of deprivation amplification was adopted as the theoretical lens through which to qualitatively explore how place promotes or constrains the use of PA in T2DM management. Developed by Macintyre and colleagues, the concept posits that individual deprivation is amplified by area-level deprivation.14,15 Macintyre suggests that the residents of deprived neighborhoods tend to have poorer access to health-promoting neighborhood features (i.e., exercise facilities or healthy food) and have easier access to health-damaging features (i.e., fast food outlets or crime).15 This framework emphasizes the importance of social meanings and local perception of neighborhoods on health (over the actual presence or absence of resources).14

Drawing on deprivation amplification as a conceptual lens, the current study sought to understand how individuals living with T2DM perceive meaning around neighborhood features that promote or discourage physical activity, and how these features interact with the environment. The primary aim was to explore the influences of the neighborhood environment on PA among people living with T2DM in an underserved community. Because people with T2DM often have physical/mobility disabilities that affect how they interact with their neighborhoods, a secondary objective was to understand how experiences may differ for people with both T2DM and physical disabilities.

METHODS

Research design

This study was conducted in conjunction with a qualitative parent study aimed to inform the development of a mobile health (mHealth) app that could promote T2DM self-management.16,17 Unlike that research, the current study adopted an emergent design and expanded the focus to include neighborhood influences on PA and on T2DM care. An emergent design allows a study design to evolve and develop as the research proceeds; thus, offers flexibility in revising and modifying the research questions and methods during the research process.18,19 Taking advantage of an emergent design, we sought to identify and more thoroughly explore the themes that came up early in data collection, resulting in an examination of their structural impact on T2DM care. A total of 71 adults participated, and data were collected through seven focus group discussions and 13 individual in-depth interviews.

Study community

The setting of the parent study, Southwest Baltimore, is a low-income AA community with high age-adjusted mortality rates for diabetes.20 To maximize recruitment, Union Square, Franklin Square, and Mount Clare were included in Southwest Baltimore, and we expanded to adjacent neighborhoods, targeting the Poppleton and Hollins Market neighborhoods.

According to recent statistics in the study community, three-fourths of the population was AA, and the estimated median household income was far below that of Baltimore and the US.20–22 The age-adjusted mortality rate for diabetes was higher than in Baltimore overall.20,21 The percentage of land covered by green spaces with tree canopy, vegetation, and parkland was less than that of Baltimore, while the percentage of land covered by pavement was slightly higher than Baltimore overall.20,21 Moreover, crime rates were high. Both non-fatal shootings and homicide rates were higher than in Baltimore overall20,21 (See Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Statistics related to neighborhood characteristics

| Neighborhood characteristics | Southwest Baltimore | Poppleton/The Terraces/Hollins Market | Baltimore City |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (% African American) | 74.3 | 79.4 | 62.8 |

| Median household income ($)1 | 24,946 | 17,228 | 41,819 |

| Age-adjusted mortality for diabetes (per 10,000 residents) | 4.4 | 6.4 | 3.0 |

| Land covered by green spaces (%) | 15.7 | 14.9 | 33.1 |

| Land covered by pavement (%) | 30.3 | 30.3 | 25.3 |

| Non-fatal shooting rate (per 10,000 residents) | 21.8 | 14.2 | 6.9 |

| Homicide rate (per 10,000 residents) | 8.2 | 7.1 | 3.9 |

| Vacant buildings (per 10,000 housings) | 2478 | 717 | 562 |

Source: Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore City 2017 Neighborhood Health Profile: Southwest Baltimore. Baltimore, MD; 2017; Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore City 2017 Neighborhood Health Profile: Poppleton/The Terraces/Hollins Market. Baltimore, MD; 2017.

The estimated median household income in the US is $61,372.

Phase I: Parent study

From February 2016 to June 2017, seven focus group discussions (N=63) and four in-depth interviews were conducted with 67 total participants. Data collection focused on the social facilitators and barriers of managing T2DM, and suggestions for developing a smartphone application to assist in T2DM management.16,17 A purposive sampling strategy was employed to include people living with T2DM, their family members or friends (hereafter, T2DM participants). These T2DM participants were recruited through flyers placed at neighborhood community centers, businesses, markets, and healthcare centers, and through word of mouth at community centers and local events. Eligibility criteria included (1) having T2DM or being a caregiver or close friend of someone with T2DM (i.e. someone involved in their diabetes management); (2) self-identifying as AA; (3) being ≥18 years old, and (4) self-identifying as a study community resident. Most T2DM participants took part in one of the six focus group discussions, with four individuals participating twice (N=54). All except one participant was AA and 63% of participants were female. Using a semi-structured discussion guide, a moderator asked about experiences with and facilitators/barriers to T2DM self-management either from a first-person perspective or from that of family members or close friends. Also, participants discussed useful features of a smartphone app that would help overcome challenges to T2DM self-management. Healthcare providers involved with T2DM management were recruited through snowball sampling from the main hospital in the neighborhood. Physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, and a pharmacist who work with T2DM patients in the study community participated in another focus group discussion (N=9) to solicit professional perspectives on the same topic. Additionally, four in-depth interviews with providers were conducted to gain more information on neighborhood influences on T2DM (See Table 2 for participant demographic information).

Table 2.

Study Participant Demographic Information (N=71)

| Data collection type | Participant characteristics | Total N | Female N | African American N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Parent study | ||||||

| Focus group discussions | T2DM participants (People living with type 2 diabetes mellitus or close family and friends) in 6 focus group discussions | 54 | 34 | 53 | ||

| Providers (1 focus group discussion) | 9 | 4 | 5 | |||

| In-depth interviews | Providers | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Phase II: Sub-study | ||||||

| In-depth interviews | T2DM participants | 8 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Providers | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Total participant number | Phase I | 67 | 41 | 59 | ||

| Phase II | ||||||

| 9 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| Phase II participants also in Phase I | 5 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Total | 71 | 43 | 61 | |||

For the focus group discussions and in-depth interviews, we used semi-structured guides to explore the experience of living with T2DM and the facilitators/barriers of managing T2DM within the neighborhood. We also inquired about coping strategies of T2DM management related to PA. After each data collection, notetakers and interviewers immediately expanded field notes that included their reflections, perspectives, and interpretations.

Phase II: Sub-study

While asking participants about experiences with T2DM management and potential features of the mobile health tool, themes regarding PA and T2DM care in relation to the neighborhood emerged. To explore this topic more deeply, we used an emergent design to inform additional data collection, focusing more on individual experiences of living with T2DM. Also, based on our initial data collection we became interested in experiences of people with physical/mobility disabilities, and so further explored the experiences of PA in this subgroup. Eligibility criteria were same as in Phase I and snowball sampling was used. The study team initially contacted Phase I participants and invited them to become Phase II participants. Some Phase II participants provided referrals to people with T2DM and their family members or friends. Individual in-depth interviews were carried out by interviewers with graduate level training in qualitative research. Some interviewers had a medical background and had in-depth understandings of T2DM through this training.

From February to May 2017, nine additional in-depth interviews were conducted focusing on neighborhood resources related to T2DM generally and for people with T2DM and physical/mobility disabilities. Eight in-depth interviews were conducted with T2DM participants. Among these eight, five participants with T2DM who had physical/mobility disabilities were recruited from participants who were in the Phase I focus group discussions. One healthcare provider, a nurse, was also interviewed (Table 2).

Data analysis

All focus group discussions and in-depth interviews in Phases I and II were digitally recorded. Moderators, notetakers, and/or interviewers expanded field notes on the same day of the focus group discussion or in-depth interview, and recordings were transcribed verbatim within several days of data collection either by the research team or by a professional transcription company. Transcripts were analyzed along with field notes. Deductive codes were determined based on the neighborhood features that promoted or discouraged PA. To identify emergent themes that were not predetermined, inductive coding was performed simultaneously with deductive coding while repeatedly reading the transcripts. Based on the recurring themes identified across transcripts, two authors consolidated a list of codes. Then, a priori deductive codes were merged with the consolidated inductive codes, and were applied to all transcripts. The codebook was used to investigate common understandings and contrasting perspectives among the participants, which were integrated into the final analysis. Atlas.ti 8 (Berlin, Germany) was used to facilitate data management, organization, and analysis.

The Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the parent study (IRB#00006500) and the sub-study (IRB#00007690). Verbal informed consent was provided by all participants.

RESULTS

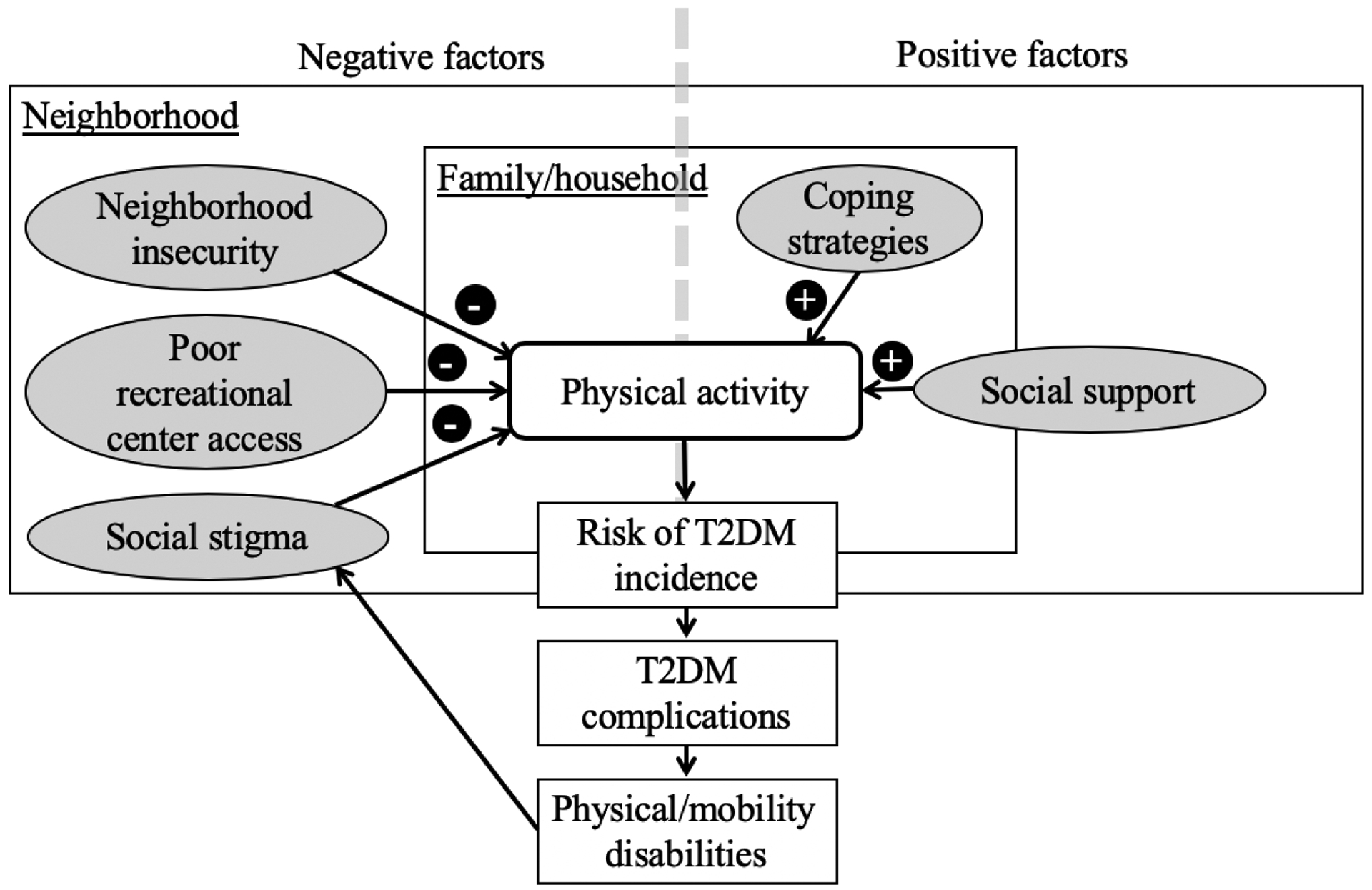

The themes presented here represent the most salient neighborhood features that emerged as affecting PA for T2DM management, providing insights into how neighborhood was perceived, navigated, and experienced by the people living with T2DM. Themes that stood out fit into three categories: 1) neighborhood features that discouraged physical activity, 2) individual coping strategies, and 3) social support (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of the effect of neighborhood environment on physical activity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management

Neighborhood insecurity and poor access to recreational facilities hinder PA

Most participants expressed knowing the importance of PA and its positive influence on T2DM management. For many participants, walking was a common way to meet their PA needs. Nonetheless, neighborhood insecurity was the most common concern, and a critical factor that hindered PA. Many T2DM participants perceived that their neighborhood was not safe, and they cited the neighborhood’s high crime rate as discouraging them from walking after dark:

“When it gets dark, I’m not saying something bad would happen, but I just don’t put myself in [that situation], yes, safety concerns, everyone usually has that.” Safety was also highlighted as an obstacle by healthcare providers: “It’s not secure enough for anyone to walk around and move and get exercise and try to improve diabetes. It’s a high crime area. People are scared to come out of their house.”

The issue of safety appeared to be even greater barrier for T2DM patients who had physical/mobility disabilities because of decreased confidence in defending themselves from potential crime. Illustrating this, one T2DM participant who was paralyzed and rehabilitated after a stroke said:

I still have that fear of [the neighborhood because] I don’t have the physical capacity to defend myself if I encounter a criminal situation. ‘Cause, being exposed to anybody in the city that has a criminal intent in their mind, you don’t know who you’re around on a daily basis and people see me walking with a cane and see me walking with a disability. Not the majority of people, but just that one percentage that could do harm to you, and you cannot defend yourself. So that was one of my greatest challenges.

Echoed by many, one participant stated “nothing at all” in the neighborhood helped with PA compared to an adjacent “mostly homeowners, pretty good neighborhood … where [in that neighborhood] people can hang out a whole lot.” With limited access to recreational spaces such as parks, gyms, recreational centers, and green spaces, some T2DM participants sought sports facilities. However, they reported a dearth of places to exercise within the neighborhood, which they described as discouraging PA. Participants explained that there were no recreational facilities except for one fitness center that was not yet open. Four participants reported using recreational facilities in distant neighborhoods, each of which was at least four miles away and inaccessible for individuals relying on public transportation. Several participants suggested that the lack of recreational centers or gyms within walking distance further compounded the problem of accessibility to exercise-related resources. The majority of T2DM participants did not have a vehicle, and one participant described transportation problems: “It would help me if I had a car – we’d go to the gym.”

While the lack of access to spaces in which to exercise affected all participants, this appeared to be particularly relevant to individuals with both T2DM and physical/mobility disabilities, as their disabilities made them vulnerable to social discrimination. Two T2DM participants with partial lower limb amputations reported attending the league for the handicapped for exercise, located in a distant neighborhood. However, one of them explained her reservations about taking public transportation to get to recreational facilities because of stigma and hostile attitudes toward her disability.

These kids that ride mass transportation are super disrespectful—I don’t wanna get [emotionally] hurt…by ridin’ the bus. So, I deter from it. …. The kids are all over the place, they fight the adults, they disrespect, curse, just any and everything they can. And I don’t want to be in a situation.

Coping strategies adopted to engage in exercise

Many participants described using coping strategies to enhance PA while living within the constraints of an unsafe neighborhood. One T2DM participant described minimizing exposure to the neighborhood environment by exercising at home. He stated that insecurity is “just the nature of the environment in which I live, so I try to do all the exercise I can within the structure where I live.” T2DM participants perceived that going to adjacent neighborhood to walk was the most feasible way to increase PA and to manage T2DM. One participant who often traveled to safer neighborhoods to walk, explained the psychological benefits of walking:

[I walk] three or four times a week, and it might not be this [with emphasis, pointing down] neighborhood but this [pointing right] neighborhood or this [pointing left] in general… That helps tremendously because when I’m walking and talking to the people, I don’t think about my illness of diabetes. And when I come home, I don’t think about it because I think, how to cope with life in general.

Because T2DM participants with disabilities were more affected by neighborhood insecurity than those without disabilities, this even more profoundly restricted the spaces available to them to exercise. For example, some T2DM participants with physical/mobility disabilities described exercising only within and around their apartment buildings: “I use these hallways, I go up and down the hallways. I use the staircase, that’s good exercise.” Another participant explained trying to solve the problem by exercising close to his building and only going far from home if with a friend:

I try to refrain from going as far away from the (apartment) building as I can for safety reasons. … I walk around outside and the building. … I’ll enter the front of the building, exit out the rear, back and forth, I’ll do it three or four times a day.

To increase PA in a neighborhood with few recreational facilities, some participants described incorporating exercise into their routine activities. For example, some participants described trying to get off a few stops before their destination when using public transportation:

“I figured if you get off the bus two blocks away and walk up where you live at, you [are] exercising.” Several participants reported parking further away when going to the supermarket. One participant explained, “I have to learn to park a little further away. I have to push myself to get involved in some activities.” A close friend of a person living with T2DM described: “My friend is diabetic. When we go shopping, she always want me to park closer. And I’m like, ‘no, we are getting couple steps in before [going].’”

Echoing strategies described by T2DM participants, one provider reported that he often recommends home exercises to compensate for the lack of recreational facilities:

Exercise is the cornerstone to manage diabetes. Because we don’t have gyms readily available, I usually tell people to stand up after 30 minutes of TV. Stand up, walk around the house. Do squats, do sit ups in the chair. Chair exercise, static exercise, simple.

Social support from family, community organizations, or healthcare providers increases PA

Many T2DM participants identified their support systems – including partners, family members, friends, or healthcare providers – as main sources of motivation to exercise. Many T2DM participants indicated that their partners directly encouraged PA. One male participant described the support he got from his partner: “The thing that made it easier [to manage T2DM] was just having the support of my fiancée - the hundred percent support that I have from her.” Some T2DM participants reported that their children or grandchildren motivated them to be physically active. “As a 54-year-old man, I try to do as much exercise as I can. I play with my children, grandchildren, and just get out on a daily basis and move around as much as I can.”

Many T2DM participants underscored peer influence on T2DM management:

“We gotta hold each other accountable. When you make a commitment to yourself, get two or three other people and you all have each other’s support.”

Another participant cited that working out with others is more motivating than exercising alone:

I find myself when I do things [exercise] with someone, I really stick to it, but if it’s just me myself, I just lay on the couch. You need somebody to push you [because] we might not be in that mood to get out and do something.

Community organizations also have strived to improve the neighborhood environment to enable residents to be physically active. The organizations hold various community events to connect residents to each other. They organize walking groups of about five people each to build PA networks. One community organizer described:

They kind of walk and talk. They get out and walk a mile or two miles and just kind of chit-chat, so it’s so obvious you’re exercising. They tend to be upper middle-aged women and it has been a good engagement mechanism.

Local community organizers and providers had made efforts to enhance PA by organizing events (e.g. yoga and dance classes) in the park. While these events were convenient, a provider explained that these events were not well attended due to police activity:

We tried to hold Zumba classes outside and we had a really poor attendance. At one of the Zumba classes there was like police helicopters above us and then people were like ‘I’m going back.’ So I think there’s a lot of barriers.

DISCUSSION

This study highlights how engagement in PA is discouraged by poor access to health-promoting neighborhood features and easy access to health-damaging neighborhood features, ultimately exacerbating problems with T2DM management. Features of deprived neighborhoods (e.g., provision of PA facilities, lack of walkable spaces in communities and neighborhood insecurity) appeared to especially affect people with both T2DM and disabilities (due to safety concerns and stigma). Although many participants showed resilience and tried to overcome these social-environmental barriers by using coping strategies and social support, these individual-level efforts were insufficient.

Features of structural disadvantage in poor neighborhoods – e.g., insecurity, few neighborhood PA resources – are consistent with other research in the US.11,23,24 Easy access to health-damaging neighborhood features (e.g., high crime, negative perception of the neighborhood, and policing) and poor access to health-promoting features (e.g., PA resources) negatively shaped participant perceptions of the quality and social meaning of neighborhood resources, ultimately discouraging PA.14 These findings imply that the concept of deprivation amplification is applicable in our study neighborhood, and potentially would also apply to other urban, low-income, AA neighborhoods. Participants emphasized that little in their neighborhood facilitated PA and T2DM management, contrasting this with adjacent affluent walkable neighborhoods. This perception suggests the influence of relative deprivation in addition to the absolute deprivation faced by our study participants. Origins of such deprivation may harken back to residential segregation that mainly occurred in the early 20th century, leading to structural inequalities of neighborhood resources25 and delayed necessary structural improvements within the community.26 In short, residents are likely experiencing lingering influences of these inequalities over time.

One notable contribution of the current study is the finding that T2DM participants with disabilities are exposed to greater barriers to PA and how their lack of opportunities for PA are amplified to a larger degree as a result of the features of neighborhood deprivation. These barriers lead them to have more limited access to venues for PA outside of existing neighborhood resources. Many T2DM participants in our study also experienced complications related to physical decline, and therefore had fewer opportunities to be physically active than those without disabilities.

Also unique to T2DM participants with physical disabilities, the findings suggested that they felt embarrassment about disclosing their disabilities in public. Restricted social contact due to such feelings among disabled T2DM patients may discourage them from accessing recreational facilities and decrease their participation in PA.27 Participants with disabilities suggested that the space they used for PA was restricted compared to those without disabilities, but described strategies to cope with these challenges. Nonetheless, these participants described lacking confidence in defending themselves, and frequently described fear of crime. While we did not find other studies on perceived neighborhood insecurity and PA among the people with T2DM, research among the elderly shows that perceptions of neighborhood insecurity is associated with long-term functional decline.28 If the perception of neighborhood insecurity translates to fewer self-care behaviors and less access to appropriate PA resources, T2DM participants with disabilities might be especially at risk for future functional decline.

Ironically, in addition to the high crime, police activities also were reported to discourage PA, and participants indicated a certain level of fear of the police, as noted elsewhere in the literature.29,30 Police killings of unarmed AAs have been linked to depression, stress, and emotional problems among AAs.31 Residents in the study community may suffer such mental health effects. However, PA improves T2DM management not only by controlling blood glucose level and preventing or delaying diabetes complications but also by improving mental health.5 Being physically active promotes mental health by reducing anxiety and depression as well as by enhancing self-esteem and cognitive function.32–34 Thus, improving mental health through PA may ultimately contribute to improving T2DM management. This idea was supported by participants who described that walking with peers helped them to relax and deal with T2DM.

Community organizers and healthcare providers also organized events to promote PA in the neighborhood. The positive influence of social support on PA has been noted elsewhere.17,35,36 Previous research from the parent study reported that several mHealth app functions that tap into social support would be helpful for T2DM management.17 The current study extends this work by exploring the neighborhood context of people living with T2DM and physical/mobility disabilities. As social isolation plays a critical role in linking the larger social environment and individual behaviors,37 more isolated participants with physical/mobility disabilities living in underserved neighborhoods may have lower PA levels. The results indicated that these participants experienced an additional layer of vulnerability due to the social isolation and stigma around such disabilities. One goal of the parent study, facilitating socially-supported self-management behavior through a social-networking app, could potentially assist improving social support and PA.

Upstream-level interventions and community-scale urban policies that help to provide places to engage in PA may complement an individual’s efforts. For example, opening a schoolyard was associated with an 84% increase in PA among low-income inner-city schoolchildren, in contrast to PA in a comparison neighborhood.38 Also, a behavioral intervention for PA and dietary education reduced weight and improved blood glucose levels among low-income adults with obesity and diabetes.39 However, the majority of PA interventions have been conducted either with specific target populations (i.e., children, students, or older adults) or in particular institutions (i.e., schools, workplaces),40–43 rather than using population-wide efforts targeting all community residents. Nonetheless, such community-wide healthy food interventions that have been implemented within specific neighborhoods have demonstrated significant dietary improvements among residents.44,45 Taken together with our findings, our study suggests that interventions and policies to improve currently available resources and services are essential to improve PA within the neighborhood.

One study limitation is that the majority of participants were recruited through a purposive sampling strategy in public spaces, potentially excluding more isolated T2DM participants. All except two of T2DM participants were AA, although only around three-fourths of neighborhood residents were AA.20,21 Due to the almost exclusive focus on AAs, the transferability of our findings may be limited. Further, because T2DM participants were predominantly female, the findings of the current study may not reflect the experiences of males. We also may not have reached saturation regarding the experiences of T2DM participants with physical disabilities. Despite these limitations, interpretation of our results through the lens of deprivation amplification provides unique insights into the local context and its social meanings as well as into the dynamics of PA for T2DM management in a low-income urban community. The current study also provides preliminary findings regarding a specific underserved group – AA adults living with T2DM and physical/mobility disabilities, who are at even higher risk of limited PA. Qualitative data collection from multiple sources enabled us to triangulate accounts among participants presenting various perspectives, and improved the credibility of the study. Moreover, the use of emergent design enriched data collection by simultaneously bringing flexibility and narrowing the focus.

IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.

This study highlights that T2DM participants living in a low-income neighborhood face not only economic stressors, but also the extra burden of living in a neighborhood lacking infrastructure that may hinder participation in PA. In addition to individual coping strategy and social support, our study suggests that interventions and policies influencing neighborhood resources are essential to improve PA. Upstream-level interventions and community-scale urban policies may lead to synergistic effects that work in combination with an individual’s existing efforts to increase PA.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the participants for taking time to share their experiences with us. We also thank all the interviewers who collected the data in the parent study and sub-study. This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR, NIH; R21NR015577) and by the Social and Behavioral Interventions Program in the Department of International Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number: R21NR015577; and the Social and Behavioral Interventions Program in the Department of International Health at Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting interests:

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Statistics About Diabetes. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Published 2018. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- 2.LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D. Place, not race: Disparities dissipate in Southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Aff. 2011;30(10). doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill J, Nielsen M, Fox MH. Understanding the social factors that contribute to diabetes: a means to informing health care and social policies for the chronically ill. Perm J. 2013;17(2):67–72. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raphael D, Anstice S, Raine K, McGannon KR, Rizvi SK, Yu V. The social determinants of the incidence and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: are we prepared to rethink our questions and redirect our research activities? Leadersh Heal Serv. 2003;16(3):10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019:S4–S6. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER. The importance of place of residence: Examining health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1682–1686. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellström E, Bremberg S. The significance of neighbourhood context to child and adolescent health and well-being: A systematic review of multilevel studies. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34:544–554. doi: 10.1080/14034940600551251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keene DE, Padilla MB. Neighborhoods, spatial stigma, and health In: Duncan DT, Kawachi I, eds. Neighborhoods and Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall MC. Diabetes in African Americans. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(962). doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.028274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Signorello LB, Schlundt DG, Cohen SS, et al. Comparing diabetes prevalence between African Americans and Whites of similar socioeconomic status. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2260–2267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smalls BL, Gregory CM, Zoller JS, Egede LE. Assessing the relationship between neighborhood factors and diabetes related health outcomes and self-care behaviors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1086-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Mujahid MS, Shen M, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1698–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, Obesity, and Diabetes — A Randomized Social Experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macintyre S Deprivation amplification revisited; or, is it always true that poorer places have poorer access to resources for healthy diets and physical activity? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4(32). doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macintyre S, Maciver S, Sooman A. Area, Class and Health: Should we be Focusing on Places or People? J Soc Policy. 1993;22(2):213–234. doi: 10.1017/S0047279400019310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zachary WW, Michlig G, Kaplan A, Nguyen N-T, Quinn CC, Surkan PJ. Participatory Design of a Social Networking App to Support Type II Diabetes Self-Management in Low-Income Minority Communities. Proc Int Symp Hum Factors Ergon Heal Care. 2017;6(1):37–43. doi: 10.1177/2327857917061010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surkan PJ, Mezzanotte KS, Sena LM, et al. Community-Driven Priorities in Smartphone Application Development: Leveraging Social Networks to Self-Manage Type 2 Diabetes in a Low-Income African American Neighborhood. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2715. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robson C Real World Research: 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore City 2017 Neighborhood Health Profile: Southwest Baltimore. Baltimore, MD; 2017. https://health.baltimorecity.gov/neighborhoods/neighborhood-health-profile-reports. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore City 2017 Neighborhood Health Profile: Poppleton/The Terraces/Hollins Market. Baltimore, MD; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontenot K, Semega J, Kollar M. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017. Washington D.C.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV., Brown DG, Erdmann CA, Bertoni AG. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and their association with insulin resistance. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):146–157. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1311–1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massey DS. Residential Segregation and Neighborhood Conditions in U.S. Metropolitan Areas In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, eds. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences 1. 1st ed. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2001:391–434. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squires GD, Kubrin CE. Privileged places: Race, uneven development and the geography of opportunity in urban America. Urban Stud. 2005;42(1):47–68. doi: 10.1080/0042098042000309694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blinde EM, McClung LR. Enhancing the physical and social self through recreational activity: Accounts of individuals with physical disabilities. Adapt Phys Act Q. 1997;14(4):327–344. doi: 10.1123/apaq.14.4.327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun VK, Cenzer IS, Kao H, Ahalt C, Williams BA. How safe is your neighborhood? Perceived neighborhood safety and functional decline in older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):541–547. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1943-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn KB, Lee JK, Renauer B, Henning KR, Stewart G. The effects of perceived phenotypic racial stereotypicality and social identity threat on racial minorities’ attitudes about police. J Soc Psychol. 2017;157(4):416–428. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2016.1215967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leger DL. Baltimore’s history of mistrust: “When police come up, everybody runs.” USA Today. April 29, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callaghan P Exercise: A neglected intervention in mental health care? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11(4):476–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox KR. Self-esteem, self-perceptions and exercise. Int J Sport Psychol. 2000;31(2):228–240. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Craft LL, Perna FM. The Benefits of Exercise for the Clinically Depressed. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(3):104–111. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v06n0301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang TS, Brown MB, Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(2):226–276. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gleeson-Kreig J Social support and physical activity in type 2 diabetes a social-ecologic approach. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(6):1037–1044. doi: 10.1177/0145721708325765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez R, Harris D. Social isolation and underclass In: Harrell AV, Peterson GE, eds. Drugs, Crime, and Social Isolation: Barriers to Urban Opportunity. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 1992:257–293. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, Watkins LT, Johnson CC, Webber LS. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: Results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn SN, Lee J, Bartlett-Prescott J, Carson L, Post L, Ward KD. Evaluation of a Behavioral Intervention With Multiple Components Among Low-Income and Uninsured Adults With Obesity and Diabetes. Am J Heal Promot. 2018;32(2):409–422. doi: 10.1177/0890117117696250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Cooper PS, Brown LM, Lusk SL. Meta-Analysis of Workplace Physical Activity Interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown T, Summerbell C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: An update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes Rev. 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.King AC, Rejeski WJ, Buchner DM. Physical activity interventions targeting older adults: A critical review and recommendations. In: American Journal of Preventive Medicine. ; 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00085-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in Small Food Stores to Change the Food Environment, Improve Diet, and Reduce Risk of Chronic Disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9(E59). doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gittelsohn J, Lee-Kwan SH, Batorsky B. Community-Based Interventions in Prepared-Food Sources: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10(E180). doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]