Abstract

In nursing homes, discussions between family members and staff regarding the end of life for residents with cognitive impairment are crucial to the choice of treatment and care consistent with residents' wishes. However, family members experience burden in such discussions, and communication with staff remains inadequate. The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study was to elucidate the meaning of continuous end-of-life discussion for family members. Data were collected using semistructured individual interviews. Thirteen family members of residents from 3 nursing homes in Kyoto, Japan, participated in the study. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis, which focused on both explicit and implicit meanings. Four themes emerged regarding the experience of end-of-life discussion: “the end of life soaking in,” “hardship of making the decision to end my family member's life,” “wavering thoughts about decisions made and actions taken,” and “feeling a sense of participation about the care.” Family members had come to accept the deaths of residents through continuous discussion and experienced strong conflict in facing the death of their family members. Moreover, staff members should understand family members' beliefs and the burden they experience in facing residents' death.

KEY WORDS: end of life, family, Japan, nursing home, qualitative research

As the global population ages, the number of elderly people who die in nursing homes (NHs) will increase.1-4 Japan faces the highest rate of population aging in the world, and the government introduced the end-of-life (EOL) care bonus for NHs, which is a financial incentive and framework of quality preservation for EOL care among NH residents.5 Nursing home residents experience difficulty in making decisions regarding EOL care because of cognitive impairment.6 Advance care planning (ACP) is a communication process pertaining to EOL care and occurs among residents, family members, and staff members before the onset of residents' cognitive impairment; it is important to ensure that EOL care is consistent with residents' wishes.7 However, the optimum time for the introduction of ACP remains unclear because predicting cognitive impairment in dementia is difficult.8 Consequently, ACP often occurs too late, and proxy decision makers, mainly residents' family members, are forced to make medical decisions on behalf of residents without any knowledge of their wishes.8,9

The guidelines10,11 recommend sufficient dialogue with family members regarding EOL care to reduce family hardship and conflict in proxy decision making and ensure that the best decisions are made when residents' intentions are unclear. Family members can struggle with their choices when discussion regarding EOL care with staff members is insufficient12; in addition, mutual understanding between family and staff through EOL discussion is a crucial factor that enables NHs to provide EOL care.13 Family members for whom EOL discussion is insufficient tend to regret their decisions, resulting in increased grief after residents' deaths.14 Moreover, previous studies have shown that communication between family members and care teams improves family satisfaction and reduces anxiety regarding EOL care.15-17

While continuous EOL discussion between family members and staff seems to be beneficial to both residents and family members, and this is recommended as a means of achieving desirable EOL for residents and their families,18 family members experience considerable burden in discussions regarding EOL issues.19 In particular, when residents have severe dementia, discussion regarding EOL issues, including “do not attempt resuscitation” (DNAR) orders, causes psychological anguish to family members.20 Moreover, communication between family members and staff remains insufficient because of various factors, including dementia and family members' reluctance.14 Therefore, NH staff members should not only provide adequate information regarding EOL but also address family members' anguish and burden during these discussions.

It is beneficial to understand the meaning of family members' experiences of continuous EOL discussion to reduce their burden and anguish. This would allow NH staff members to consider the extent of family members' pain and determine the type of care required. However, previous studies have focused mainly on staff members' or residents' experiences; thus, little is known about what the experience of such discussion means to family members. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clarify the meaning of continuous EOL discussion for family members and present suggestions regarding the provision of the best care for residents and their family members.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study involving individual interviews with NH residents' family members.

Sample

The inclusion criteria for family members of NH residents were as follows: (1) declining cognitive function in the resident, (2) deep engagement in the care of the resident before NH admission (based on medical certificates and nursing summaries, we judged this to be the case if the family member substantially engaged in the resident's daily care such as preparing their meals, changing their clothes, etc.), (3) playing a main role in proxy decision making regarding the treatment schedule and where to live throughout preadmission and postadmission to the NH, (4) resident living in an NH that provides EOL care, and (5) agreement not to initiate hospitalization during their study participation. The exclusion criterion was employment involving the management of nursing care or proxy decision making (eg, working as a long-term care support specialist or attorney).

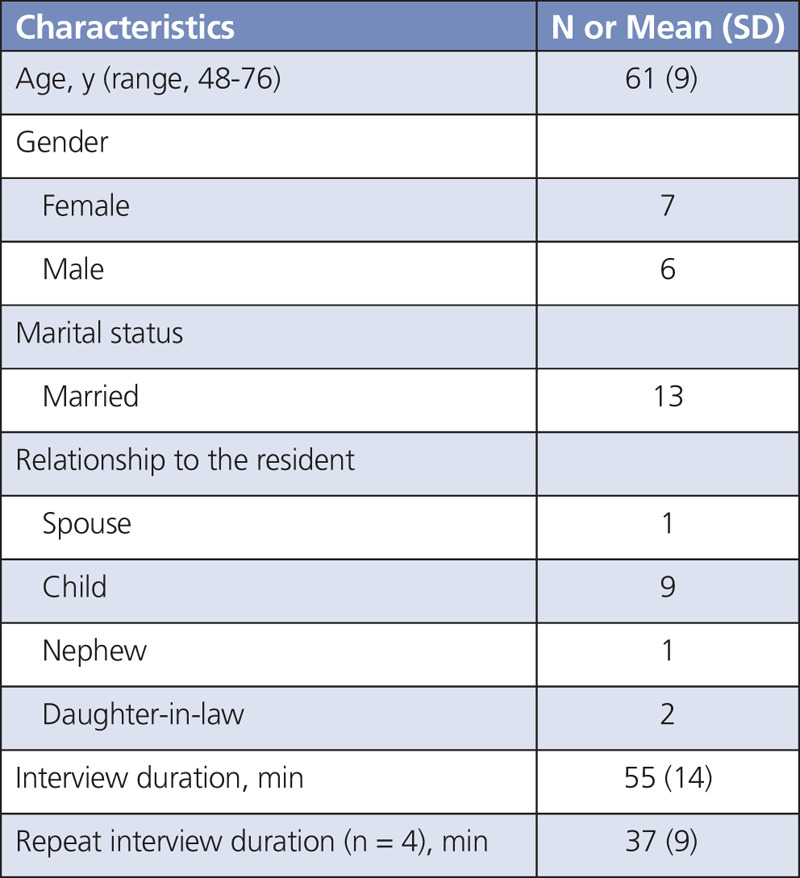

Fifteen family members of residents from 3 NHs in Kyoto participated in the study. Of the 15 interviews, 2 were excluded from the analysis because the family members were not deeply involved in the resident's care before admittance to the NH; therefore, interview data for 13 participants were analyzed. The participants' mean age was 61 years, and the average interview time was 55 minutes. Four additional interviews lasting 37 minutes, on average, were conducted with family members who were considered to have provided insufficient data in the original interviews (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 13)

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine (R0983). Before the investigation, the researcher explained the potential risks and benefits of the investigation and informed the participants that they could withdraw their participation at any point during the study.

Recruitment

The research sites were selected from NHs in Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. The administrators selected potential participants based on the inclusion criteria and initiated contact. Potential participants who expressed a willingness to participate in the research received an explanation of the details of the study from the researcher. Both verbal consent and written informed consent were obtained from all participants before the study.

Measures

Data were collected via semistructured individual interviews. Each interview lasted for approximately 60 minutes. The focus of the interview questions was as follows: (1) the resident's background from cognitive decline to NH admission, (2) experiences involving EOL discussion before and after NH admission, and (3) attitudes and perspectives regarding EOL discussions. The interviews were recorded using a voice recorder with the participants' consent. Each participant received 3000 yen for participation. Data were collected from April to August 2017.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis, which involves the systematic process of coding, examination of meaning, and provision of a description of the phenomenon through the creation of themes.21 In the first step of the analysis, the audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The researchers then read the transcriptions repeatedly and extracted “meaning units” related to family members' experience of EOL discussion, after fully understanding the context, and applied “codes” that briefly expressed the meanings. The study focused on both explicit and implicit meaning21 in the text. Thereafter, the codes were classified into groups with common meanings and placed into categories according to their similarities and differences. Categories were integrated and abstracted, and their content was described as themes. The participants' narratives were maintained as much as possible when labeling the themes to demonstrate the essential meanings of their lived experiences.

Data Management and Trustworthiness

The criteria established by Lincoln and Guba22 were used to assess the trustworthiness of the analysis. Audit trails to raw data, which provide evidence of the category, were constructed as appropriate during the analysis process to ensure dependability and confirmability. The analysis was performed under the supervision of a researcher experienced in qualitative research, and the researchers discussed any discrepancies repeatedly until consensus was reached to improve credibility. Moreover, additional interviews were conducted, with consent, if the data were judged insufficient to allow understanding of the participants' experience.

RESULTS

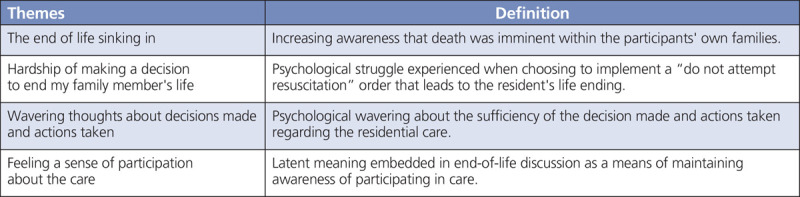

Four themes regarding the experience of EOL discussion emerged from the participants' narratives: “the end of life soaking in,” “hardship of making the decision to end my family member's life,” “continuing to stay but wavering,” and “having a sense of participation in the care.” Family members had accepted the residents' deaths through continuous EOL discussion but experienced simultaneous strong conflict in facing this reality (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Themes That Emerged From Interviews and Definitions

The End of Life Soaking in

This theme represented family members' increasing awareness that the residents had reached the EOL. All interviewees were aware of this through EOL discussion. This awareness was formed gradually and subconsciously through repeated thought about EOL care and how to spend the time that remained. “The end of life soaking in” differed from mere acceptance of death. It expressed the understanding of the fact that someday people die and that death was imminent within the participants' own families. One interviewee spoke about his growing awareness of his mother's EOL period as follows: “It has been about 4 years [since admission to the NH]. About once a year, she got sick and was admitted to the hospital. Overall, her condition was not good sometimes… It is something that has steadily been soaking in for me, and I felt that there would be [EOL] issues coming.”

In addition, some interviewees stated that the recognition of the EOL soaking in referred to not only the perception of the imminence of the resident's death but also increased awareness of their own mortality through EOL discussion. This is reflected in the statement of a resident's daughter as follows: “I knew that death would eventually come. I've accepted it, but if I did not care, I would not think about it so much. I started thinking about what I want to do with my own (EOL) care.”

Hardship of Making the Decision to End My Family Member's Life

None of the interviewees requested life-prolonging treatments, and all wanted a natural end to their family members' lives. However, they had been reluctant to decide on a DNAR order in advance within their families. This theme represented the psychological struggle experienced by family members when choosing to implement a DNAR order during EOL discussion to ensure that the resident's life would be ended. One interviewee who had not been able to discuss the implementation of a DNAR order with her father in advance described advanced medical decision making as follows: “If we had had a discussion about refraining from life-prolonging treatment while my father was healthy…I wish we had such a conversation or my father was able to state his own will, but we did not discuss it at all…in this situation, it's like I'm deciding something…in the end, will I decide to end a person's life, another's life?”

Wavering Thoughts About Decisions Made and Actions Taken

This theme represented the family members' psychological conflict regarding the choice of life-prolonging treatment during the EOL period. Family members were involved in decision making regarding daily and medical care during admission, and they felt that they were able to do what they could within the process of their own caregiving, described by a resident's son as follows: “I've been taking care of my mother during admission almost every day, and I do not have any regrets that I should have done something more…Yeah, I've done everything. I have no regrets.”

However, medical treatment and care changed as the situation changed, and several interviewees stated that they had wavered in feeling that they had done everything possible for their family members, particularly during the near-death period, described by a resident's son as follows: “I think I'll be in a flurry. I will not be able to say, like, ‘please deal with it [according to] the facility's decision,’ …maybe I will not be able to say immediately that she had been unwilling [to receive life-prolonging treatment], so please just take it away.”

These 2 contrasting narratives demonstrated that the EOL discussion process caused family members to waver in their feeling of having done everything possible.

Feeling a Sense of Participation in the Care

Many participants had endeavored to provide as much care as much as possible at home before residents' admission to NHs. They felt that it was their responsibility to provide care themselves, sacrificing their own daily lives, before NH admission. Therefore, they expressed a sense of guilt regarding residents' admission to NHs, described by a resident's son as follows: “It's something like that, like abandoning the parent's care, abandoning the parent; there seems to be that kind of prejudice, or that is a bad thing.”

After NH admission, family members had sought ways in which all family members could be at ease with using social services such as long-term care insurance. Thereafter, the sense of guilt gradually changed to one of persuasion, described by 1 resident's son as follows: “In such a care system…I do not know how I can say [it]. Well, we have reached the point where my mother is able to live with peace of mind, and I was also able to live with that without difficulty.”

Family members had fewer opportunities to be directly involved in care after NH admission. However, even after this point, they expressed a desire to be involved in their family members' care in some way, and EOL discussion allowed them to be continuously aware of “participating in the care.” One resident's son described his engagement in EOL discussion as a means of maintaining awareness that he was participating in care, as follows:

I'm not caring directly, but I think that those who have been talking about such things [EOL] can still have a sense of participation in such care…I vaguely feel that my care means reaching the end with the knowledge of participating in nursing care…Maybe for a person who was caring at home, entering the facility like this and visiting a resident evokes the same feeling.

DISCUSSION

In general, EOL discussion is regarded as a process involving the establishment of consensus between medical professionals and care stakeholders. In the analysis, we extracted 4 themes regarding the experience of EOL discussion for family members of NH residents: “the end of life soaking in,” “hardship of making the decision to end my family member's life,” “wavering thoughts about decisions made and actions taken,” and “feeling a sense of participation in the care.” These findings could contribute to a deeper understanding of the various views held by family members.

Admission to an NH is a stressful event in itself for family members.23 One reason for this is the influence of Confucian morality in East Asian culture,24 within which there is an ethical philosophy that children must care for their parents. For the family members who participated in this study, NH admission was experienced as abandonment of their duty of care. Although this gradually transformed into the belief that it was not true, after NH admission, the latent guilt regarding the abandonment of duty of care might not cease completely. This could increase the desire to maintain awareness of continuing care through the act of thinking about the resident's EOL care, which leads to the continuous implementation of EOL discussion.

The implementation of EOL discussion also included implications for subconscious penetration of awareness of the EOL. This cognitive transformation was experienced as a process of accepting the end of a resident's life. Previous research showed that the role of EOL discussion was to provide updates regarding advance directives and changes in the patient's condition.25 The current findings showed that EOL discussion included not only a mere update of previous advance directives but also the recognition of a shift in the resident's condition from daily to EOL care. This could have been one of the reasons why family members continued discussions after having agreed to DNAR. The important issue is not that of making and following advance instructions but that of understanding how the family assesses their situation. It is also useful to note that family members became aware of their own deaths through EOL discussion. Considerable numbers of NHs provide EOL care and are environments in which death exists in everyday life. Family members became more aware of the reality of their own deaths by closely observing the appearance of residents, including their own family members, reaching death. In other words, the EOL included the theme of “the end of life soaking in,” which pertained to the residents and the family members themselves.

It is necessary for all involved to make decisions about EOL treatment and care.26 The family has the right to either select or withhold life-prolonging treatment, and choosing the latter means abandoning the former. It is experienced as an act that ends the life of the resident, which leads to a specific type of pain experienced only by family members.27 When considering the implementation of life-prolonging treatment, it is important to determine whether it is deemed useless to the individual. The results of this study showed that life-prolonging treatment was considered useless when families felt that they had done all that they could do. However, the family may also question themselves as to whether they could have done more, especially as the ailing member nears his/her death. Such thoughts are natural and an expression of the depth of family love.

In Confucian morality systems, people tend to be reluctant to make medical decisions and instead leave them to clinicians.28 This attitude has been conceptualized in recent studies as relational autonomy.29 This perspective recognizes that self-determination is defined in a social context (ie, ethnicity, familial positioning, etc) and that this context influences the expressions or development of autonomy. From the perspective of relational autonomy, it is important to form a consensus with all stakeholders in considering withdrawal of life-prolonging treatment at the EOL.30 Responsibility for proxy decision making should not be imposed only on family members. It is necessary for all involved to make decisions about EOL treatment and care.

Family members tend to lack information when considering the EOL; therefore, the provision of sufficient information is important.16 However, regardless of the amount of information provided, the family members' anguish about ending the resident's life will not be alleviated. Care providers should endeavor to understand the experiences and feelings of residents' families. Moreover, family members need informal EOL discussion.31 There is a need for a social infrastructure that allows for discussion regarding EOL events in the community, in addition to formal discussions with staff at facilities, to minimize the anguish experienced by families.

This study had several limitations. For example, the findings are not generalizable due to the qualitative nature of the study. In addition, because the interviews involved narratives in which participants recalled past experiences, the results are based on the participants' memories and might not reflect those experiences accurately. Furthermore, the participating facilities were selected from a limited area of Kyoto Prefecture; therefore, the influence of facility and regional characteristics cannot be ignored. In the future, surveys should be conducted in areas and facilities with different cultural characteristics and clarify differences to verify the current results.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study examined the experience of EOL discussions between family members and staff at NHs in Japan. The analysis of 13 narratives obtained via semistructured interviews and using the content analysis method revealed 4 themes regarding EOL discussion. It became clear that EOL discussion in NHs requires understanding of the anguish experienced by families, evaluation of attitudes toward EOL discussion, and provision of appropriate information. Moreover, it is necessary to develop a social foundation to support the sharing of EOL preferences between residents and family members to ensure that decisions respect their preferences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to all the residents and family members who participated in this research. We would also like to acknowledge the facility managers and Professor Keiko Tamura from Kyoto University, who kindly guided the research.

Footnotes

This research was supported through a contract with the Yumi Memorial Foundation for Home Health Care. The foundation was not involved in the management of the research, including planning, data management, analysis, or the publication of results. This manuscript is a part of a revised master's thesis.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.US National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: with special feature on mortality. 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30702833. Accessed August 2, 2019. [PubMed]

- 2.Kalseth J, Theisen OM. Trends in place of death: the role of demographic and epidemiological shifts in end-of-life care policy. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):964–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black H Waugh C Munoz-Arroyo R, et al. Predictors of place of death in south West Scotland 2000-2010: retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(8):764–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasch B, Blum K, Gude P, Bausewein C. Place of death: trends over the course of a decade: a population-based study of death certificates from the years 2001 and 2011. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(29–30):496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishiguchi S, Sugaya N, Sakamaki K, Mizushima S. End-of-life care bonus promoting end-of-life care in nursing homes: an 11-year retrospective longitudinal prefecture-wide study in Japan. Biosci Trends. 2017;11(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bollig G, Gjengedal E, Rosland JH. They know!—do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliat Med. 2016;30(5):456–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rietjens JAC Sudore RL Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mignani V, Ingravallo F, Mariani E, Chattat R. Perspectives of older people living in long-term care facilities and of their family members toward advance care planning discussions: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gjerberg E, Lillemoen L, Førde R, Pedersen R. End-of-life care communications and shared decision-making in Norwegian nursing homes—experiences and perspectives of patients and relatives. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare. Jinsei no saishuudankai ni okeru iryou no ketteipurosesu ni kansuru gaidorain [Guidelines for the process of medical decision making on the end stage of life]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-10802000-Iseikyoku-Shidouka/0000197701.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 11.The Japan Gerontological Society. Koureishakea no ishiketteipurosesu ni kansuru gaidorain. [Guidelines for the decision-making process of elderly people]. https://www.jpn-geriat-soc.or.jp/proposal/pdf/jgs_ahn_gl_2012.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2019.

- 12.Nasu K, Fukahori H. Family members' experiences with frail older adults living and dying in nursing homes. Japan Acad Gerontol Nurs. 2014;19(1):34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright AA Zhang B Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towsley GL, Hirschman KB, Madden C. Conversations about end of life: perspectives of nursing home residents, family, and staff. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(5):421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saini G Sampson EL Davis S, et al. An ethnographic study of strategies to support discussions with family members on end-of-life care for people with advanced dementia in nursing homes. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thoresen L, Lillemoen L. “I just think that we should be informed” a qualitative study of family involvement in advance care planning in nursing homes. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahner JC Beunders AJM van der Heide A, et al. Interventions guiding advance care planning conversations: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):227–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord K, Livingston G, Cooper C. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to and interventions for proxy decision-making by family carers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(8):1301–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livingston G Leavey G Manela M, et al. Making decisions for people with dementia who lack capacity: qualitative study of family members in UK. BMJ. 2010;341:c4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonella S, Basso I, De Marinis MG, Campagna S, Di Giulio P. Good end-of-life care in nursing home according to the family members' perspective: a systematic review of qualitative findings. Palliat Med. 2019;33(6):589–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mojtaba V, Jacqueline J, Hannele T, Sherrill S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;6(5):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln and Guba's Evaluative Criteria. 2006. http://www.qualres.org/HomeLinc-3684.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 23.Kwon SH, Tae YS. Nursing home placement: the process of decision making and adaptation among adult children caregivers of demented parents in Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2012;6(4):143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(2):116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong JH, Kwon JH, Kim IK, Ko JH, Kang YJ, Kim HK. Adopting advance directives reinforces patient participation in end-of-life care discussion. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(2):753–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goossens B, Sevenants A, Declercq A, Van Audenhove C. ‘We DECide optimized’—training nursing home staff in shared decision-making skills for advance care planning conversations in dementia care: protocol of a pretest-posttest cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonella S, Basso I, De Marinis MG, Campagna S, Di Giulio P. Good end-of-life care in nursing home according to the family carers' perspective: a systematic review of qualitative findings. Palliat Med. 2019;33(6):589–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwok C, Koo FK. Participation in treatment decision-making among Chinese-Australian women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gómez-Vírseda C, de Maeseneer Y, Gastmans C. Relational autonomy: what does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Killackey T, Peter E, Maciver J, Mohammed S. Advance care planning with chronically ill patients: a relational autonomy approach. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(2):360–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson C, Bamford C, Exley C, Emmett C, Hughes J, Robinson L. Planning for tomorrow whilst living for today: the views of people with dementia and their families on advance care planning. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013. Dec;25(12):2011–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]