Abstract

Each community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership may incur “ripple effects” – impacts that happen outside the scope of planned projects. We used brainstorming and interviewing to create a roadmap that incorporated input from nine CBPR participants and five community/academic partners to retrospectively assess the ripple effects observed after five years of participatory research in one urban community. The resulting roadmap reflected a range of community impacts which we then divided into four key areas: impacts in the community (i.e., strategies, programs, and policies implemented by community partners), impacts on the CBPR team, impacts on individuals (participants and community members), and contributions to the field and the university. Our approach focused on observing what happened in the community that was directly or indirectly related to our partnership, process, products, and relationships. Much of the impact we observed reflected the synergy of sharing our research and community voice with responsive partners and stakeholders.

Introduction

Building and sustaining strong, collaborative partnerships between universities and communities is a key goal of academic community engagement programs. Research on partnership outcomes is evolving (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2010), but the field of community-based participatory research (CBPR) still suffers from gaps in evaluating outcomes (Wallerstein et al., 2010). Continued work is needed to document the link between CBPR efforts and action taken to affect community change (Cook, 2007). Reviews of CBPR outcomes have generally focused on the outcomes of planned interventions and the rigor of research methodology rather than on the planned and unplanned impact of CBPR partnerships that unfold over time (Viswanathan et al., 2004).

The impacts of CBPR initiatives may be assessed using traditional or participatory program evaluation methods that focus on planned short-, medium-, and long-term impacts and outcomes (Scarinci, Johnson, Hardy, Marron, & Partridge, 2009). However, because CBPR involves many strategies (e. g., developing partnerships, capacity building, collaboration, outreach, dissemination, action planning), each partnership or initiative may incur a series of “ripple effects” whereby a range of impacts occurs outside of the scope of planned projects. Examples of these impacts accruing from CBPR projects include growth in shared knowledge, research capacity, partnership, and connectedness within communities; improved understanding of academic and community priorities; creation of community and academic products, best-practice guidelines, and grant proposals; policy changes; advocacy; health-related community trainings; funding for local initiatives; further research; and changes in administrative data collection (Clements-Nolle & Bachrach, 2010; Hardy, Hulen, Shaw, Mundell, & Evans, 2017; Jones, Koegel, & Wells, 2008; Themba-Nixon, Minkler, & Freudenberg, 2010).

CBPR is an iterative process and its impacts may extend beyond the aims of a particular project. Rather than assessing the impact of isolated projects, we sought to identify what happened in the community that was directly or indirectly facilitated by our partnership, process, products, and relationships since we began working together. As noted by Jagosh et al. (2015), in describing their approach to evaluating CBPR: “unplanned outcomes can sometimes have a greater influence on the determinants of health for a community than the more narrowly focussed outcome goals of projects” that create ripple effects over time (p. 3). We present our attempt to assess these “ripple effects” over five years of conducting participatory research in one urban community.

Engaging Richmond Background and Key Partnership

In 2011, the Center on Society and Health (CSH) at Virginia Commonwealth University received an award from the National Institutes of Health to use CBPR to engage the Richmond, Virginia, community as a partner in ranking local social and environmental contributors to health outcomes and disparities. The goals were to identify locally important contributors to health outcomes and disparities; build community capacity to assess and address community needs; and develop longer-term, bidirectional relationships of trust and collaboration between the community and the university as part of the latter’s larger program of clinical and translational research. We began with the most fundamental task of community-based research – identifying which “community” we would work with and learning as much as possible about it. To aid in selecting a community to partner with, we developed a “Community Decision Matrix” to document (a) the needs and assets of candidate communities, (b) potential community partners, (c) existing community engagement efforts, and (d) specific challenges and assets that might affect our ability to form a strong partnership. We completed the matrix for two communities near the university that were of greatest interest. A strong deciding factor was the availability of community partners with shared values, such as community-based organizations and coalitions, to facilitate entrée and support the integration of CBPR activities and findings into local initiatives. As part of this process, we conducted informational interviews with stakeholders to review existing community engagement and research initiatives. We identified the East End community, and we chose Richmond Promise Neighborhood (RPN) as a partner based on the shared values of resident-led community change, its strong relationships with community leaders, and its active multi-sector collaboration.

RPN is a coalition-building collaborative that was launched in April 2009 in the East End neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia by a group of service providers and local funders inspired by the U. S. Department of Education’s national Promise Neighborhood initiative. RPN is a cradle-to-career initiative that works to end generational poverty and improve children’s success in school by providing neighborhood families with the same opportunities found in neighborhoods with greater resources. While RPN is not a national Promise Neighborhood site (it did not receive federal funding), its work aligns with the national model. In 2011, with a coalition of about 20 organizations (nonprofits and local foundations) at the table, RPN had also begun recruiting and developing relationships with community residents. The coalition wanted to convene and connect a fully inclusive community of service providers and residents. It also needed to produce a community needs assessment to provide critical baseline data, set direction, and track progress. Thus, Virginia Commonwealth University launched its CBPR program at an ideal time to leverage and build upon relationships RPN had already developed to deliver an inclusive and community-driven needs assessment.

We recruited potential CBPR team members by regularly attending meetings with community leaders hosted by RPN, contacting community-based organizations, and convening meetings in easily accessible community locations. We held several interest meetings for potential team members to answer questions about the project. Those who chose to join became part of our team, and we began weekly meetings. The team was named Engaging Richmond (ER). At the start, the team consisted of a diverse group of adult community residents, service providers, and university researchers and graduate students. Table 1 shows the number of ER members over the course of the partnership, organized by the role each member took when they first joined. Some members changed roles: for example, two community members were later hired as full-time university staff.

Table 1.

Number and Initial Role of Engaging Richmond Team Members

| Initial Role | Number |

|---|---|

| Community members (mostly from the East End community) | 20 |

| Faculty/staff/students | 8 |

| Community service providers | 2 |

| Total | 30 |

Local residents who have participated in ER have been well matched with East End demographics such as race (predominantly African American) and educational attainment. Although many of the original team members have left and others have joined, ER continued regular weekly meetings and team building for over five years. ER engaged in regular co-training activities based on the expertise of the groups: academic partners shared knowledge related to research methods, while community partners shared boots-on-the-ground expertise about their own community.

CBPR’s basic principle of “equitable partnership” between the community and academic partners in all stages of the research process (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005) can help to build trust and facilitate communication while providing opportunities for capacity building. Successful CBPR requires many basic principles to be met, including clearly communicated goals, sufficient knowledge of the community, relationship development, self-determination, partnership, recognition of diversity, mobilization of community assets, flexibility, and long-term commitment (McCloskey et al., 2011). Community-based research allows for, and requires, research and knowledge to be grounded in different types of expertise and institutional arrangements and to move toward different ideas of social change (O’Connor, 2001). Essential to ER’s success was team members and community partners accepting that they were engaging in CBPR, recognizing the enormity of this multi-method process, and being involved in each step, from selecting the topic or issue of interest to implementing action plans.

ER was initially tasked with conducting research for a community health equity report. We set out to identify and rank locally important social and environmental contributors to health outcomes and disparities within the geographic area of interest. Our research plan for this project included focus groups, key informant interviews, and a Photo-Voice project (Kramer et al., 2010). We collaboratively collected, coded, and analyzed the data using a grounded approach (Woolf, Zimmerman, Haley, & Krist, 2016), and we identified three community priorities using a specialized rubric that included a series of ranking steps. Specifically, the most salient topics raised during the focus groups were evaluated based on whether the team considered them to be (a) actionable (e.g., policies, programs, education), (b) important (e.g., impact, concern, vulnerable populations), (c) fundable, and (d) of interest to community partners. We utilized a modified nominal group technique (National Association of County and City Health Officials, n.d.), in which each member of the CBPR team proposed a topic to prioritize and each proposed topic was discussed by the group before voting on the top three priorities.

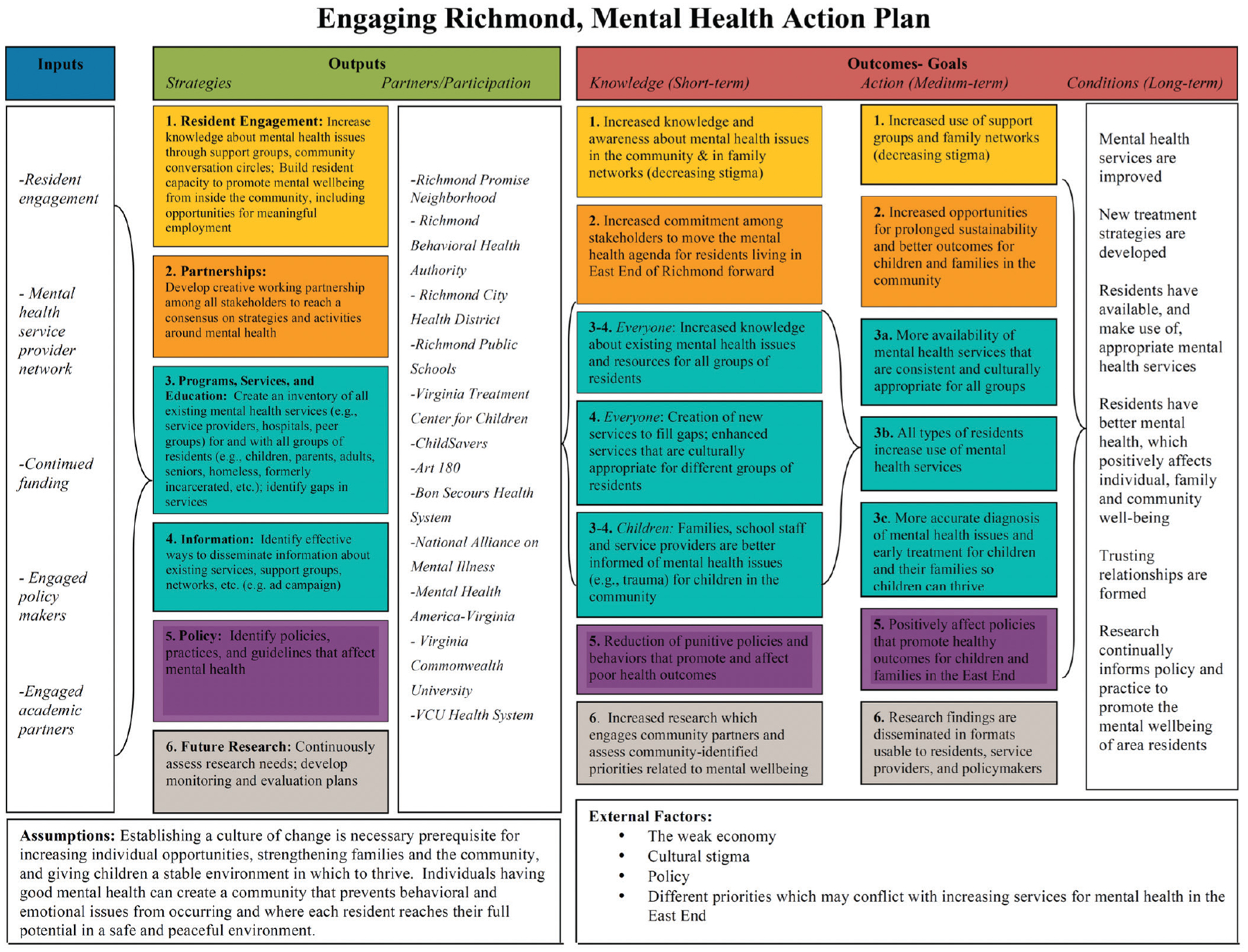

The next phase of our work involved developing action plans, adapted from a logic model framework, in these priority areas. Community action plans have been defined as “a road map for creating community change by specifying what will be done, who will do it and how it will be done” (Mizoguchi, Luluquisen, Witt, & Maker, 2004, p. 86). The team produced action plans for mental health, parental involvement, and workforce development. The plans focused on inputs, outputs (including strategies and partnerships), and short-, medium-, and long-term outcome goals for the community that could be addressed by ER, community organizations, and other local stakeholders. In addition, each plan included action elements related to resident engagement, partnership, programs, information, policy, and future research. One such action plan is shown in Figure 1. We wanted the work to be embedded within the community, with responsibility for action distributed across appropriate actors. To support this aim, our partners at RPN formally adopted the action plans in multi-sector collaborative work groups called action teams. The health and wellness action team adopted the mental health action plan, and the early childhood action team adopted the parental engagement action plan.

Figure 1.

Mental Health Action Plan

Community action continued in parallel with ER’s research. ER focused on sustaining our CBPR efforts by pursuing additional funding and attending to emerging community concerns. After assessing community needs and priorities in our first year of partnership, subsequent research focused on topics related to the original priorities and additional research areas raised by the community, partners, and other investigators. In the five-year period 2012–17, ER led or collaborated on projects related to public housing redevelopment, early childhood education, the consequences of firearms violence, engaging parents in planning afterschool programs for middle school, the relationship between education and health, civic engagement, chronic disease, and asthma.

With so much field work to keep the CBPR team occupied, along with much parallel and collaborative work being undertaken by and with our community partners, we have struggled to formally evaluate the impact of the community–university partnership. Much of our collaborative research has lacked the components that are typically the focus of program evaluations (e.g., theory of change or program objectives). Although ER has conducted limited evaluations (e.g., measuring group dynamics and conducting post-project interviews), this article reports our first effort to evaluate the indirect or unplanned impacts of our work. The purpose of this article is to document the impacts of our partnership and to better understand how the strategies utilized over the course of CBPR work with community partners can ripple out to participants and the community in myriad ways.

Method

Our methods resemble – in their goals and scope – several existing approaches to retrospective evaluation of program or network impacts. Ripple Effects Mapping, for example, is a participatory evaluation method that engages program and community stakeholders to retrospectively and visually map intended and unintended impacts, or the “chain of effects” of complex community collaborations (Chazdon et al., 2017). The process emerged from the Community Capitals Framework, which maps how increases in one type of capital (e.g., natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial, or built capital) affect other types (Hansen, 2017). The core elements of Ripple Effect Mapping include appreciative inquiry, a participatory approach, interactive group interviewing and reflection, and radiant thinking (mind mapping; Chazdon & Langan, 2017). Another retrospective method, outcome harvesting, examines the planned and unplanned effects of complex programs or networks, particularly in the context of exploring broad, system-wide changes. The process follows six steps, which include obtaining outcome information from reports, interviews, and other sources, and substantiating and analyzing the outcome descriptions (Wilson-Grau & Britt, 2012). The 3-“I” Model evaluates the community impact of service-learning partnerships by focusing on process across three dimensions: initiator, initiative, and impact (Clarke, 2003). These dimensions cover important aspects of impact, such as partnership development and community involvement.

Smaller initiatives, such as community–university partnerships or service-learning projects, may lack the resources to assess impacts using the methods described above, but nonetheless can benefit from a retrospective examination of the planned and unplanned impacts of their work among participants and the community. The process described here required relatively few resources to complete. We assessed impacts retrospectively based on the results of brainstorming, interviewing, and mapping the resulting data.

To begin examining the ripple effects of ER’s work, a subcommittee of three ER team members (faculty, staff, and community) reviewed the action plans to determine which outcomes had been achieved since they were created. The action plans were a convenient starting point because they documented the outcomes the team and community partners had recommended based on the community needs assessment. Then a larger group of ER members collaborated to create a visual roadmap of these outcomes, diagramming the flow of impacts from the team’s projects to subsequent actions taken by our team or others in the community, such as changes in programs or policies implemented by community agencies and local government. For example, our community assessment (output) led to subsequent actions by the team (e.g., funded and unfunded research proposals that were developed in response to identified community needs) and by community partners (e.g., development of RPN’s action teams), and to changes in community processes (e.g., relationship building). We went through several iterations of developing the roadmap with additional ER members (former and current), including both community and academic members of the team (nine total). We then interviewed five community and academic partners for input and suggestions to create a more complete ripple-effect graphic. These partners were stakeholders in community-based organizations and local agencies, as well as academic researchers we had collaborated with. Interview questions for partners are shown in Table 2 and were adapted from the Ripple Effects Mapping process (Welborn et al., 2016).

Table 2.

Questions Assessing Engaging Richmond’s Outcomes and Impacts

| Because of Engaging Richmond’s work and community engagement, are people doing anything different at your organization? In the area of mental health? Housing? Parental engagement? What actions or activities do you know of that have been taken by community or local institutions that were directly or indirectly related to Engaging Richmond’s work? Who is benefiting from Engaging Richmond’s work and how? What changes are you seeing in the community’s systems, institutions, and organizations as a result of Engaging Richmond’s work? Because of all of this work, in what ways has the community changed as a whole? How have everyday ways of thinking and doing in the community changed? What are the most significant outcomes? |

The impacts listed in this article were agreed upon by consensus of the team and, where appropriate, were verified by former members and external stakeholders. We sought stakeholders’ perspectives on how ER affected their work and other changes in the community, either directly or indirectly. We also consulted qualitative data from interviews with team members that were conducted at the end of major projects. We added this information to the map and continued to revise it. We then color-coded the boxes and arrows to reflect different strategies (outreach and resident engagement, partnerships, programs/services/education, policy, and research).

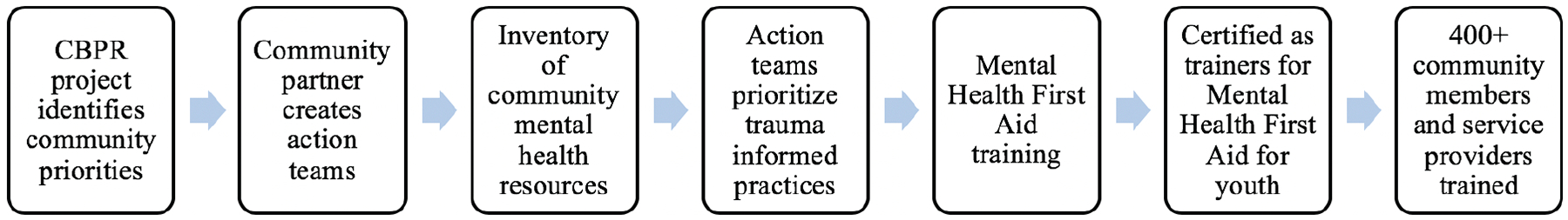

The final map is messy and imperfect but was a useful tool for exploring impacts. Although the full map is too detailed to recreate here, Figure 2 displays one pathway that follows a sequence of events that began with the team’s CBPR work to identify community priorities. Mental health, particularly the issue of stigma, was among the several top priorities. Our community partner, RPN, adopted these priorities and developed action teams linked to each one. The Health and Wellness Action Team prioritized trauma-informed practices in working with the community and provided training in Mental Health First Aid for Adults (Cleary, Horsfall, & Escott, 2015) for 20 to 25 community leaders and organizers. The region’s Community Services Board (CSB) supported its Prevention Manager in joining the RPN Health and Wellness Action Team. Upon hearing about the Mental Health First Aid Training for Adults, the CSB offered RPN a scholarship for certifying a trainer in Mental Health First Aid for Youth. A member of the ER team completed the training and is now a certified facilitator. In partnership with CSB staff, she has certified more than 400 school personnel (including truant and security officers), residents, and non-profit staff. This has produced ripple effects on the community, the ER team, and individuals. The sequence shown in Figure 2 illustrates this pathway in a simplified schematic. The full map includes additional pathways leading into and out of the boxes pictured, representing additional influences and outcomes.

Figure 2.

Impacts and Ripple Effects of ER Community–University Partnership.

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research.

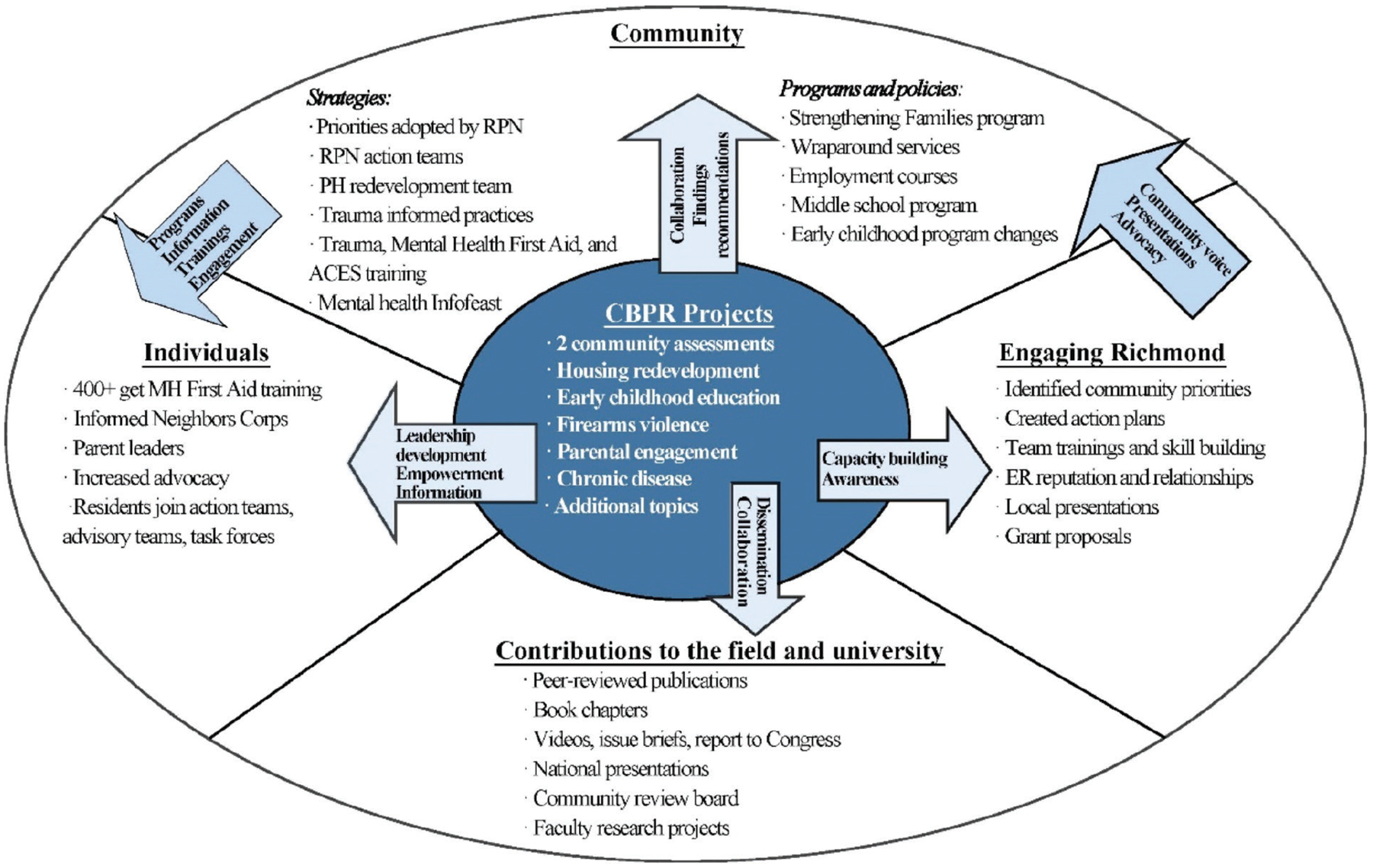

As we continued developing the roadmap, we simplified the impacts into the schematic shown in Figure 3, with CBPR projects in the center and impacts divided into four key areas: impacts on the community (i.e., strategies, programs, and policies implemented by community partners), impacts on the ER team, impacts on individuals (participants and community members), and contributions to the field and the university.

Figure 3.

Example Ripple Effect of ER Community-University Partnership: Mental Health

Note. RPN = Richmond Promise Neighborhood; ER = Engaging Richmond; PH = public health; ACES = adverse childhood experiences; MH = mental health.

Results

Impact on the Community

We divided the observed impacts of the CBPR work on the community into two broad categories: impact on the strategies and impact on the programs and policies of community partners and local agencies. Here we report the observed impacts on organizations and agencies with which we have closely collaborated.

Strategies.

The strategies identified include changes in priorities, planning, and organizational approaches to community engagement that have resulted from or been influenced by ER’s work. Many of the most significant impacts came directly from our partnerships with RPN, frequently through the work of their action teams, which met monthly to enhance cross-sector collaboration and develop shared priorities and initiatives. The action teams helped to meet the information needs identified in the needs assessment by planning trainings and educational events on priority topics.

As RPN has adopted the ER action plans for the three community priorities, mental health and parental engagement have emerged as two key drivers for the work of the action teams. Key impacts have included trainings and information-sharing initiatives, such as the Mental Health First Aid training described above. In the summer of 2015, RPN partnered with the Department of Social Services and a mental health clinical services partner agency to develop and pilot “Trauma 101” workshops for caregivers and service providers. These workshops focused on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), including their impact on brain development, behavior, and academic performance, as well as the power of resilience in combating ACEs. A series of “Trauma 101” train-the-trainer sessions was conducted in the winter of 2015. RPN now hosts regular quarterly trainings for caregivers and service providers. To attract parents and grandparents in the community, RPN created the Rebounding Strong series that combines “Trauma 101” with a focus on individual and community resilience. At the end of the sessions, the participants take a picture of what they are going to do differently and commit to a change in behavior related to past trauma. In August 2016, the state’s first community summit on ACEs was sponsored by the Department of Social Services, SCAN (Stop Child Abuse Now), and the United Way of Greater Richmond and Petersburg. Two of these three entities were RPN action team members. Overall, there has been deepened awareness about the importance of a trauma-informed approach.

RPN also shared information with the community via its quarterly Info Feasts. These community events brought together residents and service providers to share a meal and information in a bidirectional, interactive format. Each Info Feast had a “theme”; for example, two of the Info Feasts addressing community priorities identified by ER were “Powerful Parents” (information provided primarily by parents about enhancing parent engagement and parenting skills) and “Get Your Mind Right” (breaking down the stigma about mental illness and strengthening mental health and wellness).

Another example of ER impact on community engagement strategies was the development of a Public Health Redevelopment Team. The geographic area served by RPN included four public housing developments, and residents – many of whom felt they had no voice in the process – were facing the prospect of potential relocation as part of redevelopment planning. With funding from the Kresge Foundation, we partnered with RPN and the Urban Institute to convene a team of more than 35 local service provider organizations and other stakeholders responsible for services delivered to these residents. The team met monthly to identify and prioritize community health needs, review recommendations for evidence-based practices identified by the Urban Institute, and make recommendations for local developers and policymakers. Throughout the process, team members presented recommendations and evidence-based practices to additional stakeholders through individual and group meetings. After reviewing data and best practices, the group identified community priorities related to the redevelopment process and developed action plans for each priority area.

Programs and policies.

Several local programs and policies were implemented following ER’s priority setting and the creation of action plans. For example, city agencies responded to several action items identified by the Public Health Redevelopment Team, such as a plan to pilot test wraparound services for vulnerable families who were to be displaced as a result of public housing redevelopment.

RPN action teams have had an active influence on local parent engagement programs. The Early Childhood Action Team was a key supporter of the Regional Kindergarten Registration Process, which identified one day in the spring of 2011 for all schools to launch kindergarten registration. The effort was led by Smart Beginnings, a regional coalition of public and private organizations, businesses, and citizens working together to ensure that the region’s children enter school healthy, well cared-for, and ready to succeed. In 2013, the Early Childhood Action Team began supporting school staff with registration and presenting door-to-door invitations to parents and caregivers in the community to participate in the process.

In another example of program impact, the Peter Paul Development Center (PPDC), the community organization that houses RPN, adopted the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s Protective Factors framework for parent education and capacity building. PPDC has integrated the University of Iowa’s seven-week, evidence-based curriculum, Strengthening Families, into its two-generational program, Promise Family Network. The program recognizes the importance of social cohesion; it forges strong peer-to-peer relationships and supports healthy family environments and goals for both youth and adults. Parents have attended workshops on resilience and trauma, writing resumes, job interviewing, and credit repair.

Across projects, we have found that many significant ripple effects in the community depended on the collaboration of community partners and stakeholders, particularly those who valued the data that were collected and interpreted by the community and that meaningfully represented residents’ voices and priorities. By adopting the community priorities that ER identified through CBPR, RPN and other community partners broadened the potential ripple effects of the community–university partnership to involve numerous organizations and individuals.

Impact on Individuals

CBPR efforts can influence the participants themselves. This section focuses on the impact of ER’s work on individual CBPR team members, academic and community partners, and community residents. Studies have reported on several benefits of CBPR participation for community members, such as being listened to, becoming a more engaged member of society, empowerment (Marullo et al., 2003), and gaining new horizons (Flicker, 2008). Capacity building was a goal of the partnership, with the hope that residents would gain new skills and apply them in continued work in their communities. We promoted skill building through formal trainings as well as ongoing mentoring. CBPR team member interviews reflected satisfaction with applying newly acquired skills (Table 3), such as public speaking, networking, collecting data, and understanding the research process, as well as broader skills such as new interests, increased personal efficacy and social capital, and greater empathy. One team member described how other members built her confidence in trying out a new skill and the power of receiving positive feedback. Table 3 provides quotes illustrating additional individual outcomes, such as becoming an advocate, developing better understanding, and gaining increased agency. Ultimately, capacity building and increased attention to resident voices empowered some participants to advocate for community needs in unanticipated ways. After participating in our ER team, several members increased their civic engagement and connectedness. They took on additional roles on citizens’ advisory groups, task forces, and local advisory boards. Others became involved in the RPN action teams. Local agencies and coalitions responded by moving toward greater recognition and prioritization of resident engagement, creating additional opportunities for resident engagement and empowerment. One of the benefits of developing a “roadmap” of partnership impacts was the ability to trace the increased connectedness and civic engagement of the ER team members.

Table 3.

Quotes Illustrating the Individual Impacts of Engaging Richmond

|

Skills “Just getting those one-on-one interaction skills with people and help sharpening skills in my community …” “Public speaking was the number one thing for me, being able to feel comfortable with myself … And then having feedback from my peers saying ‘Oh [name] you did such a good job,’ or ‘wow you really came through.’” |

|

Knowledge and understanding “Now, I actually see the neighborhoods completely totally different. And I grew up in them all my life. And I just found that to be one of those WOW moments … It caused me to look a whole lot different, to have a little bit more understanding, a lot more open-mindedness.” “My skills and knowledge have increased … I certainly have learned more about people’s concerns about hypertension and diabetes and some of the barriers that they face and issues that are relevant.” “I’ve become aware of a whole lot more situations and circumstances as to why things are the way they are and how to possibly fix those in some circumstances. Things that I would not have probably cared about or given a second thought before.” |

|

Agency “I used to wonder, just like so many residents in there, about how could we go about getting more information to the community about different resources, different service providers. Why isn’t this being done, why isn’t that being done? Who do we go to? Who do we talk to? How do we got some of these materials? All these questions that I had in my head was answered just by me being part of this team.” “But when I became a part of this group it just enlightened a lot of things for me … It’s just given me a bigger voice. More like I could really help the people that’s around me.” “I can look at the bigger picture. Now I can see, I look further than helping me.” |

|

Personal growth “I never in a million years would have expected to gain what I gained from it on a team level or on a personal level.” “I’ve grown a lot through this. I know anything is possible regardless of what type of lifestyle you lived in the past. If you decide to walk the right walk, doors will open.” “I think that it has given us as residents a sense of purpose.” “It basically opened the door for me to go to the next level in my life.” |

ER spin-off projects created opportunities for additional residents to be involved in advocacy and to receive leadership training (see Figure 3). For example, the CSH and ER partnered with RPN to establish the Informed Neighbors Corps, a leadership and advocacy training program for public housing residents. This work supported the shared goals of increasing transparency about the housing redevelopment process and promoting resident leadership. Twenty participants met 18 times over the course of the project, working together to create and distribute informational materials about redevelopment and organizing a door-to-door informational campaign and neighbor-to-neighbor meetings. The impacts on participants included increased awareness of the broader redevelopment in the East End and of the redevelopment process, enthusiasm for continuing the Informed Neighbors Corps’s work beyond contracted dates, and social network growth among neighbors.

Another opportunity to enhance resident engagement resulted from ER’s interest in early childhood services and education. A city agency engaged ER as a partner in research on early childhood education services, sponsored by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. ER was responsible for collecting qualitative and quantitative data on early childhood education and engaging parents from a local public housing community to take up the topic and become leaders and advocates within their community. A group of nine parent leaders participated in leadership and advocacy training, collected data from parents and child care providers around early childhood education, and conducted a door-to-door early childhood education registration campaign. At the end of the project, they made recommendations to address challenges to accessing and enrolling in early childhood services.

For ER members and community participants in the leadership projects, being part of an ongoing community–university partnership that prioritized capacity building created opportunities for residents to take on a variety of new roles in the community. Regular ER team meetings that incorporated research and skills training provided opportunities for mentoring as well as trainings and experience necessary for understanding and conducting research, disseminating findings, public speaking, and learning about the community’s history, needs, and priorities. In addition, academic partners benefited from CBPR work. Those we interviewed described learning about community engagement through collaboration with ER. One partner noted how much she learned about engaging families in research and developing appropriate tools. Another learned the importance of gaining skills in community engagement and felt more likely to interact with and engage communities in future projects.

Impact on the ER Team

Cruz and Giles (2000) have proposed approaching the community impact of community–university partnerships by focusing on the partnership itself as a unit of analysis. This approach reflects the value of sustained partnerships and collaboration as an important impact of CBPR work. We found that building trusting relationships within partnerships and with communities, responding to emerging needs and concerns, and building infrastructure for continued engagement are not only prerequisites of CBPR but also important outcomes that affect community conditions as well as community–university relations.

It is useful to consider individuals’ motivations for becoming CBPR team members, as well as their expectations for what will be accomplished and how. From residents’ comments during team meetings and interviews, we identified a number of motivations and expectations (see Table 4). A primary motivation was the desire to engender positive change in the community. There was a strong sense of hopefulness among participants that participating in research provided an avenue to make change possible. However, the positive motivation to help their communities was often coupled with the bitter residue of past attempts at engagement that left them feeling sidelined or in the dark, with no data or benefits for them or the community. Team members hoped that this project would finally provide a sense of ownership for participants and for the community, a result many felt was achieved by the end of our first yearlong project (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Quotes Illustrating the Team Impacts of Engaging Richmond

|

Motivations “I want this team to make sure people get what they need … Families need to get somewhere.” |

|

Skepticism based on previous engagement “What happens when we give it? … We don’t get anything in return. We see this happen so many times, it makes it seem that it didn’t matter, what we gave, and our voice doesn’t matter.” |

|

Ownership “I feel a lot of ownership. I feel like the success or failure of the project is my success or failure. I feel like I want everyone to feel the same way. I want everyone to do their best, I just feel like this is our project, this is a representation of our work and this is what people see, so it has to be done and done well.” |

|

Building trust “I think there is a lot of trust. I think it has increased since we’ve been a team. I think we have a lot of respect for one another and each other’s opinions, which is why we can agree to disagree now, versus going back and forth constantly.” “I’d say it [trust] increased because as time went on we got to know each other so we know what to expect from each other.” “We all sit at the table and we all have the same reciprocity.” |

|

Experience with research and action

“We need some action and some solutions. I got frustrated, because it’s like ‘Oh my goodness, are we really going to waste this time again with the problems, what the system did, and policies?’ Okay, we know all of that.” “That’s the frustration for everybody - you don’t always see what you’re building. But as time goes on you see what you’re building. ‘Cause that’s the nature of the process and that’s why the frustration sets in.” |

|

Reputation “I think that they [service providers who participated in focus groups] were impressed with what we brought to the process … I think they were generally taken aback in a very good way that here there’s this group of people in the community that are working on research in the kind of way that we are and it’s like, ‘Where have these people been?’” |

Hopefulness at the start of the project was also tempered by a strong sense of skepticism. Issues of distrust and skepticism are common when “outside” groups enter a community to conduct research or provide interventions (Christopher, Watts, McCormick, & Young, 2008). Trust in researchers and participation in research projects are lower among African Americans than others, due both to historical injustices in research (such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study) and to current social inequities (Scharff et al., 2010). Skepticism voiced by participants at the start of the project largely reflected disappointment accumulated from previous projects that did not deliver on their promises. In other studies, African American focus group participants have expressed frustration about failure to report research results back to the community (Scharff et al., 2010) and about research that is exploitative or simply fails to meet community needs (Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007). It is important to confront these concerns and experiences and position CBPR as a framework intended to “transform this historical experience by setting new standards for community control of research, pioneering joint interpretation and use of research results, and promoting community benefit” (Hicks et al., 2012, p. 296).

Many individuals who have participated in community–university partnerships report a lack of “a baseline level of trust” (Wolff & Maurana, 2001, p. 168) due in large part to a historical lack of reciprocity from researchers and their institutions (Becker, Israel, & Allen, 2005). The potential for unequal rewards is a challenge posed by such partnerships, as faculty stand to gain funding, publications, and recognition, while rewards to community partners may be less concrete (Minkler, 2005). Often, this imbalance occurs because community members are expected to contribute to the project for little or no compensation. Much for this reason, community members on the CBPR team were paid a competitive hourly wage. Most participants conveyed a perception that trust grew over the course of the project. We believe that trust grew out of having clear group principles, being supportive of each other, listening, showing respect, sharing roles and responsibilities, becoming familiar with each other, and sharing a strong sense that we constituted a team. Providing meals and paying team members played a major part in building trust, aligned with the principle of respect for each other’s time and contributions.

Community capacity building through CBPR is important for sustaining partnerships and building infrastructure (Hacker et al., 2012). To involve all members of the CBPR team in each phase of the research, ER has engaged in methodology trainings on topics such as qualitative research (e.g., focus group facilitation, conducting interviews, and qualitative data analysis/coding), survey administration, human subjects training, best practices in recruitment, and preparing and making presentations. In addition, sustainability has required flexibility, as ER has taken up work on a variety of issues with different partners. Sustainability is made possible, in large part, by the team building processes that have been ongoing throughout ER’s existence, from developing and updating partnership principles to sharing roles and responsibilities. Another facilitator of team sustainability was the ability to hire a community member from the team to work full-time as a “boundary spanner” – to connect ER with people and opportunities from both the university and the community. As described in Weerts and Sandmann (2010), this team member focused on community problem solving, building rapport, and facilitating dialog (Hacker et al., 2012).

Impact on the Field and the University

Over the course of our five-year observation period, ER engaged in a wide range of academic activities, including developing research proposals, refining participatory methods, promoting community engagement, and collaborating with university faculty. Its work has encompassed projects originating from the team, from action plans, from partners, and from academic researchers. Some of the work focused on methodological approaches to participatory research. In one such effort, the CSH was asked to create a rapid-cycle report on proposed changes to federal food assistance eligibility. To assist in the effort, ER used participatory concept modeling to help develop an analytic model linking policy changes to potential health effects (Woolf, Braveman, & Evans, 2013). ER again used participatory concept modeling in CHS’s Education and Health Initiative, modeling the various causal pathways linking education to health outcomes (Zimmerman, Woolf, & Haley, 2015). The success of these two pilot initiatives led to a proposal to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to test a new method, called the SEED method, for involving patients and other stakeholders in the development and prioritization of research questions. ER led the implementation of a demonstration project in Richmond, Virginia, to use the SEED method to generate a stakeholder-driven research agenda on the management of diabetes and hypertension. The method built on ER’s previous experience with participatory causal modeling, involving patients, service providers, and other stakeholders in a process that generated conceptual models and research questions (Zimmerman, Cook, Haley, Woolf, & Price, 2017).

A review of investigator-initiated research projects identified 10 studies led by university faculty to which ER contributed at various stages, collaborating on proposal development, research design, development of research instruments, participant recruitment, data collection and analysis, or dissemination. ER has contributed to four peer-reviewed articles (two pending) and two book chapters (one pending), many of which focus on ER processes such as collaborative coding of qualitative data (Woolf et al., 2016), participatory modeling (Zimmerman et al., 2015), and the SEED method (Zimmerman et al., 2017). In addition, ER has contributed to more than a dozen conference presentations and posters on topics that included stakeholder engagement and leadership in the public housing redevelopment process, the SEED method, measuring civic engagement, relationship building in CBPR, strengthening early childhood programs, and the social determinants of health.

Many of ER’s action plans called for further research on some aspect of the identified priorities. Our team responded by developing a series of research proposals, some of which resulted in further funding. Examples include the previously described work on public housing redevelopment, parental engagement, and early childhood programs. Some proposals inspired by action plans were not funded. Examples include a National Institutes of Health R01 proposal to address mental health–related stigma and a foundation proposal on regional workforce development. We continue to seek new opportunities and funding to address the needs identified.

Infrastructure building in the context of CBPR partnerships has been described as “the mutual creation of guidelines and frameworks for collaboration” that become embedded within existing systems (Hacker et al., 2012, p. 352). One example of impact in this area is ER’s involvement in the creation of a Community Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University, a mechanism designed to provide community feedback to principal investigators on their research design. The work of ER, together with many other community-engaged partnerships at the university, has helped to create a cultural shift in how researchers think about partnering with community members. This shift is reflected in how faculty have approached collaborations with ER or have consulted with them through the Community Review Board, and in a change in language from “participant” to “partner” when referring to community members.

Discussion

This article has presented CBPR impacts on communities, individuals, teams, and fields/universities. These impacts are reinforced through linkages that bridge these groups. Presenting research findings back to the community is a common component of CBPR work (Chen, Diaz, Lucas, & Rosenthal, 2010), and it was a crucial link between ER and community organizations, stakeholders, and residents. ER conducted formal presentations on the research findings of several projects, usually at organized meetings, and also shared information with the community at local events, such as information sheets and flyers containing health-related information or lists of local resources. Other examples of linking activities included ER presentations at conferences and ER team members’ contributions to community initiatives and events. Other linking activities are illustrated by the arrows in Figure 3.

Israel, Checkoway, Schulz, and Zimmerman (1994) have described three interrelated levels of empowerment for understanding community change: individual, organizational, and community empowerment. They describe an empowered community as one in which “individuals and organizations apply their skills and resources in collective efforts to meet their respective needs,” and one that can “influence decisions and changes in the larger social system” (p. 153). Many of the documented impacts of ER’s partnership could be ascribed to increased empowerment. These impacts are bidirectional, in that the partnership leads to empowerment but is also dependent upon it. We also agree with Cook’s (2007) assessment that collaboration among government, university researchers, and community partners can be an effective model for integrating research and action. In our experience, having a sustained community–university partnership strengthened the channels of communication and built relationships among residents, the university, and community partners. Indeed, much of the impact over the five years we observed reflected the synergy of sharing our research and community voice with responsive partners and stakeholders. In return, we found that community organizations and agencies were more eager to incorporate resident input into decision making and sought to engage residents earlier in these processes. Although we have presented the impacts divided into four categories, they are nonetheless inextricably linked. For example, leadership development that affects individual participants creates community capital and capacity (Goodman et al., 1998). Community capacity, as described by Goodman et al (1998), has many dimensions: citizen participation and leadership, skills and resources, social and inter-organizational networks, a sense of community, an understanding of community history, community power and values, and critical reflection. Assessing the ripple effects of CBPR exposes how research that focuses on collaboration and capacity building and facilitates community action can contribute to each of these dimensions of community capacity.

Our approach to assessing the impacts focused on observing what happened in the community that was directly or indirectly related to our CBPR partnership, process, products, and relationships. The impacts that we mapped are largely based on our impressions of what occurred and those of a limited set of informants, and not on systematic data collection, measurement, or attempts to assess causality. We relied on participants’ perceptions that certain events influenced the events or outcomes that followed. This approach is not suited to assessing certain types of impact, such as effects on health outcomes, which requires systematic, longitudinal data collection and was not within the scope of our work. Although there is a rich literature on participatory evaluation, we have not positioned our work in this context because it was not meant to serve as a program evaluation based on a planned set of outcomes for which our team was responsible. The majority of the outcomes documented through this process were unplanned and were the result of action by stakeholders outside of the ER team. While our approach limits the empirical strength of our evidence, it may have broad utility in that it provides an accessible way for partnerships that lack resources for a prospective evaluation to examine impacts in various domains, including effects in the community, and to examine the relationships and strategies that facilitated those impacts. A strength of this approach is its potential for assessing “ripple effects” that go beyond the planned aims of partnership projects.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the past and present Engaging Richmond members as well as all of our collaborators and community partners. We are grateful for the collaboration of Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health, Richmond Promise Neighborhood, Peter Paul Development Center, and the ongoing work of the Richmond Promise Neighborhood Community Action Network. Thank you to those who sat down with us for interviews and contributed to our ripple effects road map. Special thanks to the agencies and foundations that have funded our work.

Funding

Our work has been supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. CTSA ULTR00058 and UL1RR031990, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences). Projects described in this article were supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Kresge Foundation, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). All statements in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of these funders, who had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Biography

EMILY ZIMMERMAN is an Associate Professor in the Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Department of Family Medicine and Population Health, Division of Epidemiology, and Director of Community Engaged Research and Qualitative Research at VCU’s Center on Society and Health. With a background in sociology, social research, and public health, her research focuses on the factors that affect individual, family, and community well-being. Her current work focuses on social and place-based determinants of health, community engagement, and stakeholder engagement in research.

AMBER HALEY is a Ph.D. student at University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public Health. She has served as the Associate Director of the Community Engagement Core for the Center for Translational Science at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she worked to develop university-wide infrastructure to support community-engaged research. Amber has master’s-level training in epidemiology and has managed projects funded by the National Institutes of Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation.

GWEN CORLEY CREIGHTON is the Lead Consultant for Corley Creighton Associates, a strategy-and capacity-building practice that she founded in 1989. From 2011–2018 she was the Director of Richmond Promise Neighborhood (RPN) at the Peter Paul Development Center. In that role, she was the lead architect of RPN, a place-based, two-generation education collaborative initiative. Her professional career spanning over 40 years has included software training, leadership development, board development, community development, and strategic thinking and planning Gwen. holds a Master of Education with a focus on organization development and training.

CHANEL BEA is a Community Engagement Assistant at Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Center on Society and Health. She is a founding member of Engaging Richmond, a community-academic research team at the VCU Center on Society and Health. She is a current member of the Richmond Promise Neighborhood (RPN) Advisory Board, YMCA Diabetes Program Community Advisory Board, and the Maggie L. Walker Citizens Advisory Board. Through RPN, she serves as a Community Advocate; a Co-Convener of the Early Childhood Action Team; and the Advisory Board chair. Chanel is also a Leadership Metro Richmond class of 2018 member.

CHIMERE MILES is a social science research assistant at Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Center on Society and Health and a founding member of Engaging Richmond. She has volunteered with many groups and organizations in Richmond, VA, including Early Head Start, Richmond Public Schools Head Start (as the Policy Council Chairperson), the Richmond Public Schools Truancy Committee, and Richmond Promise Neighborhood. Chimere has an Associate’s Degree in Allied Health and Science, and her previous work experience includes patient care work and medical administrative duties. She serves as a Community Advocate at Peter Paul Development Center. Chimere is also a member of the Leadership Metro Richmond class of 2018.

ANDREA ROBLES manages projects related to capacity-building and civic engagement as well as the newly established National Service and Civic Research Competition for universities. She specializes in participatory research and is developing several new initiatives to incorporate this approach into Corporation for National and Community Service work. Andrea has a B.A. from New York University; an M.A. in International Development from American University; and an M.S. and Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

SARAH COOK is a Research Projects Coordinator at Vanderbilt University’s Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR). She received a Master of Public Health in Health Behavior from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2014. Prior to her current position with VICTR, she worked as a Research Epidemiologist at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center on Society and Health, where she coordinated a number of community-based participatory research projects.

ALICIA AROCHE is the Community Academic Liaison and Research Associate for Community Engagement at Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Center on Society and Health. Her roles include coordinating community engagement efforts for the VCU Wright Center on Clinical and Translational Research, funded by the Clinical Translational Science Award, and serving on the Community-Based Participatory Research Team, Engaging Richmond. She previously worked as the Community Engagement Advocate and Communications Manager for Bridging Richmond, a cradle-to-career regional collaborative. She is a graduate of Virginia Commonwealth University with a master’s degree in Education.

Contributor Information

Emily B. Zimmerman, Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health

Gwen Corley Creighton, Peter Paul Development Center.

Amber Haley, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Chanel Bea, Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health.

Andrea Robles, Corporation for National and Community Service.

Alicia Aroche, Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health.

References

- Becker AB, Israel A, & Allen AJ III. (2005). Strategies and techniques for effective group Process in CBPR partnerships In Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.), Methods in community-based participatory research for health (pp. 52–72). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon S, Emery M, Hansen D, Higgins L, & Sero R (Eds.). (2017). A field guide to ripple effects mapping. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon S, & Langan S (2017). The core ingredients of ripple effects mapping In Chazdon S, Emery M, Hansen D, Higgins L, & Sero R (Eds.), A field guide to ripple effects mapping (pp. 5–20). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Chen PG, Diaz N, Lucas G, & Rosenthal MS (2010). Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(4), 372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, & Young S (2008). Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M (2003). Finding the community in service learning research: The 3-“I” model In Billig SH & Eyler J (Eds.), Deconstructing service-learning: Research exploring context participation and impacts (pp. 125–146). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Horsfall J, & Escott P (2015). The value of mental health first aid training. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(11), 924–926. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1088322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, & Bachrach AM (2010). CBPR with a hidden population: The transgender community health project a decade later In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (pp. 137–148). Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cook WK (2007). Integrating research and action: A systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 668–676. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.067645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz NI, & Giles DE (2000). Where’s the community in service-learning research? Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Fall(1), 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S (2008). Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the positive youth project. Health Education & Behavior, 35(1), 70–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Freeman C, Kass NE, Tracey P, Ross G, Bates-Hopkins B, Purnell L, et al. (2007). “You’ve got to understand community”: Community perceptions on “breaking the disconnect” between researchers and communities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 1(3), 231–240. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Speers M, McLeroy K, Fawcett S, Kegler M, Parker E, et al. (1998). Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education & Behavior, 25(3), 258–278. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Tendulkar S, Rideout C, Bhuiya N, Trinh-Shevrin C, Savage C, et al. (2012). Community capacity building and sustainability: Outcomes of community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 6(3), 349–360. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DA (2017). The origins of ripple effects mapping In Chazdon S, Emery M, Hansen D, Higgins L, & Sero R (Eds.), A field guide to ripple effects mapping (pp. 1–4). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Hulen E, Shaw K, Mundell L, & Evans C (2017). Ripple effect: An evaluation tool for increasing connectedness through community health partnerships. Action Research, 16, 299–318. doi:10.1177%2F1476750316688512 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, et al. (2012). Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 6(3), 289–299. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Checkoway B, Schulz A, & Zimmerman M (1994). Health education and community empowerment: Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 149–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (2005). Introduction to methods in community-based participatory research for health In Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.), Methods in community-based participatory research for health (pp. 3–26). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Bush P, Salsberg J, Macaulay A, Greenhalgh T, Wong G, et al. (2015). A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health, 15, Article 725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Koegel P, & Wells KB (2008). Bringing experimental design to community-partnered participatory research In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed, pp. 67–85). Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L, Schwartz P, Cheadle A, Borton JE, Wright M, Chase C, & Lindley C (2010). Promoting policy and environmental change using photovoice in the Kaiser Permanente community health initiative. Health Promotion Practice, 11(3), 332–339. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marullo S, Cooke D, Willis J, Rollins A, Burke J, Bonilla P, & Waldref V (2003). Community-based research assessments: Some principles and practices. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Michener JL, Akintobi TH, Bonham A, Cook J, et al. (2011). Principles of community engagement (2nd ed). Bethesda, MD: NIH (NIH Publication No. 11–7782) Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M (2005). Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Urban Health, 82(2, Suppl. 2), ii3–ii12. doi:10.1093%2Fjurban%2Fjti034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, & Wallerstein N (Eds.). (2010). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi N, Luluquisen M, Witt S, & Maker L (2004). A handbook for participatory community assessments: Experiences from Alameda County Oakland, CA: Alameda County Public Health Department. Retrieved from http://www.acphd.org/media/53637/prtcmty2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Association of County and City Health Officials. (n.d.). Guide to prioritization techniques. Retrieved from http://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Gudie-to-Prioritization-Techniques.pdf

- O’Connor A (2001). Poverty knowledge: Social science, social policy, and the poor in twentieth-century U.S. history Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Johnson RE, Hardy C, Marron J, & Partridge EE (2009). Planning and implementation of a participatory evaluation strategy: A viable approach in the evaluation of community-based participatory programs addressing cancer disparities. Evaluation and Program Planning, 32(3), 221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, & Edwards D (2010). More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 879–897. doi:10.1353%2F-hpu.0.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Themba-Nixon M, Minkler M, & Freudenberg N (2010). The role of CBPR in policy In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (pp. 307–322). Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence (Prepared by RTI–University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment no. 99, AHRQ Publication 04-E022–2) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved from https://www.donau-uni.ac.at/imperia/md/content/department/evidenzbasierte_medizin/abstracts_pub-likationen_gerald/community-based_participatory_re-search._assessing_the_evidence.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, & Rae R (2010). What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (pp. 371–392). Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts DJ, & Sandmann LR (2010). Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 702–727. [Google Scholar]

- Welborn R, Downey L, Hyjer Dyk P, Monroe PA, Tyler-Mackey C, & Worthy SL (2016). Turning the tide on poverty: Documenting impacts through ripple effect mapping. Community Development, 47(3), 385–402. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2016.1167099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Grau R, & Britt H (2012). Outcome harvesting. Cairo, Egypt: Ford Foundation; Retrieved from http://www.managingforimpact.org/sites/default/files/resource/wilsongrau_en_outome_harvesting_brief_revised_nov_2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, & Maurana CA (2001). Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health: A qualitative study of perspectives from communities. Academic Medicine, 76(2), 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Braveman P, & Evans BF (2013). The health implications of reduced food stamp eligibility. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University, Center on Human Needs; Retrieved from https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/media/society-health/VCUSNAP-IncomeHealth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Zimmerman E, Haley A, & Krist A (2016). Authentic engagement of patients and communities can transform research, practice, and policy. Health Affairs, 35(4), 590–594. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman EB, Cook SK, Haley AD, Woolf SH, Price SK (2017). A patient and provider research agenda on diabetes and hypertension management. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman EB, Woolf SH, & Haley A (2015). Understanding the relationship between education and health: A review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives In Kaplan R, Spittel M, & David D (Eds.), Population health: Behavioral and social science insights (pp. 347–384). Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/population-health.pdf [Google Scholar]