Background: Standard testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) requires a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab but is limited by modest sensitivity, the need for health care human resources and personal protective equipment, and the potential for transmission in transit to or at the testing center. An urgent need exists for innovative testing strategies to expedite identification of cases and facilitate mass testing.

Objective: To determine the detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 using a novel, self-administered kit for saliva collection compared with standard swab testing.

Methods: We prospectively enrolled consecutive, asymptomatic, high-risk persons and those with mild symptoms suggestive of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a centralized testing center in Ottawa, Canada. Eligible adults provided 1 saliva specimen using a self-collection kit (OMNIgene•ORAL, OM-505 [DNA Genotek]) concurrent with their standard swab test. These kits are designed for self-collection without expert assistance and can preserve viral material at room temperature for transport and analysis (1). Total nucleic acid extraction and polymerase chain reaction analysis for SARS-CoV-2 were done at the Eastern Ontario Regional Laboratory in Ottawa for swabs and at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg for saliva. Outcomes were reported for detection of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope (E) gene with a cycle threshold value less than 37. The Supplement (available at Annals.org) provides additional methodological details.

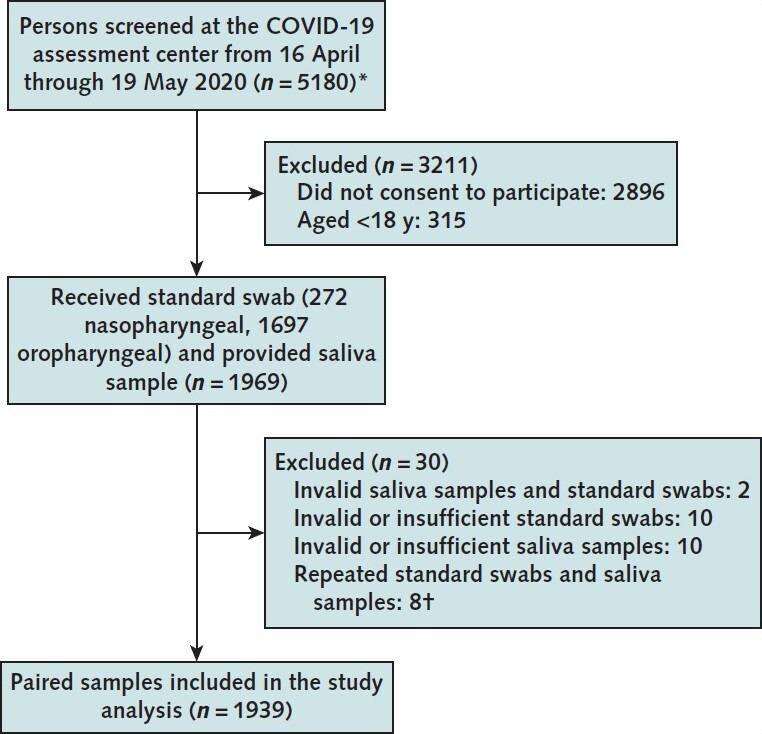

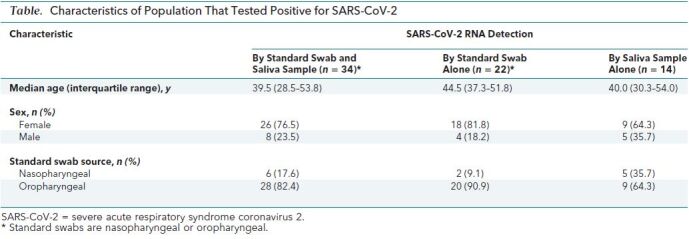

Findings: Of the 1939 paired swab and saliva samples analyzed (Figure), SARS-CoV-2 E gene was detected in 70 samples (Table), 80.0% with swabs and 68.6% with saliva. Thirty-four participants (48.6%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on both swab and saliva samples. Discordant test results were seen in 22 participants (31.4%) who tested positive with swab alone and in 14 (20%) who tested positive with saliva alone. Swabs were obtained from the nasopharynx in 35.7% of participants who tested positive with saliva alone, compared with 9.1% of participants who tested positive with swab alone.

Figure. Study flow diagram.

Standard swab and saliva sample collection during the study period. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

* Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 y, provision of informed consent, and being high-risk asymptomatic or having mild symptoms of COVID-19. Patients were screened before entry by a physician. Those with severe symptoms were redirected to an emergency department for formal clinical evaluation.

† Eight participants were tested twice at the testing center (for both standard swab and saliva sample). Two tested positive on their initial oropharyngeal swab and negative on a saliva sample. These participants' results remained positive on an oropharyngeal swab and negative on a saliva sample on repeated testing (5 d and 8 d later). One participant tested positive on the initial oropharyngeal swab and negative on the saliva sample. This participant tested negative on both specimens 7 d later. The remaining 6 participants tested negative on initial and repeated testing for both specimens.

Table. Characteristics of Population That Tested Positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Discussion: Our study found that standard diagnostic methods of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs detected more COVID-19 cases than saliva testing among patients who were asymptomatic but at high risk or who were mildly symptomatic. Salivary detection of SARS-CoV-2 has been proposed as an alternative to standard swab diagnostic methods. Saliva testing presents potential advantages: Collection does not require trained staff or personal protective equipment, can be done outside testing centers, and may be better tolerated in challenging or pediatric populations.

Because of RNA instability, use of raw saliva necessitates rapid transportation to a laboratory for extraction of viral material and polymerase chain reaction analysis. This study is unique in that it used a novel collection kit containing a preservative and viricidal fluid, allowing for safe and stable storage and transport of the samples. Our findings add to those of previous studies, which have focused on salivary tests of symptomatic or hospitalized patients (2); these studies have suggested that saliva tests may be more sensitive. By design, we included asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic persons to simulate mass screening for COVID-19.

Our study has important limitations. First, evaluating the performance of a novel diagnostic test in the absence of a true gold standard reference is challenging. The reported false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–based testing for SARS-CoV-2 using swabs is approximately 38% at symptom onset and as high as 100% shortly after exposure (3). In our study, 20% of COVID-19 cases were detected by saliva alone, further supporting the notion that standard swab testing may be an unreliable reference standard. Second, nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabbing was done according to swab availability at the testing center even though nasopharyngeal swabs are preferred in symptomatic persons and those later in the illness course (4), which may have affected our results. Analyses of the influence of swab site on study results were not done because of limited sample size. Third, analysis of swab and saliva samples was split between 2 laboratories to accommodate the demand for testing resources in a pandemic. The potential effect of assay differences was mitigated by a targeted evaluation of the E gene, a widely accepted and sensitive target gene for SARS-CoV-2 (5). Finally, more than half of eligible patients declined participation.

Nonetheless, our study shows the feasibility of a simple, safe collection tool for salivary detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the setting of a COVID-19 testing center. Despite a lower estimated rate of detection relative to swab testing, saliva testing may be of particular benefit for remote, vulnerable, or challenging populations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 28 August 2020

References

- 1.Wasserman JK, Rourke R, Purgina B, et al. HPV DNA in saliva from patients with SCC of the head and neck is specific for p16-positive oropharyngeal tumours. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46:3. [PMID: 28061890] doi:10.1186/s40463-016-0179-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Czumbel LM, Kiss S, Farkas N, et al. Saliva as a candidate for COVID-19 diagnostic testing: a meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:465. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, et al. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:262-267. [PMID: 32422057] doi:10.7326/M20-1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Patel MR, Carroll D, Ussery E, et al. Performance of oropharyngeal swab testing compared to nasopharyngeal swab testing for diagnosis of COVID-19 —United States, January-February 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: 32548635] doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [PMID: 31992387] doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.