Abstract

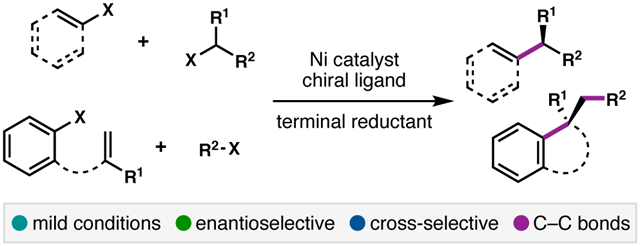

Nickel-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling reactions have emerged as powerful methods to join two electrophiles. These reactions have proven particularly useful for the coupling of sec-alkyl electrophiles to form stereogenic centers; however, the development of enantioselective variants remains challenging. In this Perspective, we summarize the progress that has been made toward Ni-catalyzed enantioselective reductive cross-coupling reactions.

Graphical Abstract

I. Introduction

Transition metal catalysis has unlocked new modes of reactivity that have redefined the synthetic strategies used for the preparation of enantioenriched molecules. Cross-couplings constitute one subset of transition metal-catalyzed reactions and canonically refer to the coupling of an organic electrophile (typically an organic halide or pseudohalide) with an organometallic reagent. The use of C(sp3) coupling partners has traditionally been limited by slow oxidative addition or transmetalation, as well as decomposition via rapid β-hydride elimination in the presence of palladium or other precious metals.1 Employing base metal catalysts, such as nickel, for sec-alkyl cross-couplings can circumvent these challenges.2

Recently, Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling (RCC) reactions, which join two electrophiles in the presence of a terminal reductant, have emerged as promising methods for the enantioselective coupling of C(sp3) electrophiles.3 RCC reactions typically proceed under less basic conditions at ambient temperatures (between 0 and 40 °C), which allows broad functional group tolerance and avoids racemization of newly formed stereocenters. Given that halide electrophiles are often used as precursors to the organometallic coupling partners for canonical cross-coupling reactions, and the wide commercial availability of the halogenated building blocks, the direct use of these electrophiles in RCCs is appealing.4 RCC reactions can be particularly advantageous for intramolecular C─C bond formation, because they obviate the need to install both an electrophile and an organometallic functional group in the same starting material.5

Several challenges exist that hinder development of reductive cross-coupling reactions. Most methods require a stoichiometric amount of heterogeneous metal dust as a terminal reductant, which renders them sensitive to stir rates, in addition to metal purity and mesh size.6,7a The generation of metal salt byproducts, as well as the common use of amide solvents, reduces the sustainability of RCCs and can introduce reproducibility issues.8,9 Although RCCs are widely used by medicinal chemists, advances in reductant and solvent choices will be required for application of this technology in process chemistry.8,10,11

In this Perspective, we discuss the development of enantioselective RCCs catalyzed by nickel that employ a terminal reducing agent. Related reactions that are stereospecific,3e that utilize photoredox co-catalysis,12,13 or that involve 1,2-addition to polar π-systems (e.g. the Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi coupling)14 have been reviewed elsewhere.

II. Historical Context for RCC Reactions

Seminal reports by Semmelhack,15 Kende,16 and Kumada17 demonstrated the ability of nickel to mediate the reductive homocoupling of C(sp2) halide electrophiles to form biaryl products (Scheme 1).18 However, extension of this reactivity from homocoupling to the cross-coupling of distinct partners remained elusive for several decades, due to the challenges associated with achieving cross-selectivity.19 When employing two electrophilic coupling partners, a large excess of the less-reactive electrophile can be one way to outcompete the homocoupling process. A more efficient strategy is to sequence the reactions of the two electrophiles, such as by leveraging the different rates of oxidative addition of a C(sp2) or C(sp3) electrophile to different Ni species in the catalytic cycle.20,21 If the two electrophiles react selectively with distinct oxidation states of the Ni catalyst, then sequential oxidative addition events can afford the desired cross-coupled product and minimize homocoupled dimers.22 Thus, optimization campaigns for these reactions often focus on how reaction parameters affect the distribution of the desired cross-coupled product to homodimers and reduction products.

Scheme 1.

Seminal reports of Ni-mediated reductive homocoupling.

Much effort has focused on the Ni-catalyzed cross-selective couplings of sec-alkyl electrophiles. In 2007, Durandetti and coworkers reported the Ni-catalyzed reductive C(sp2)–C(sp3) cross-coupling of α-chloroesters and aryl iodides using Mn0 as a terminal reductant (Scheme 2a).23 Weix and coworkers followed in 2010 with the RCC of a sec-alkyl bromide and an aryl iodide, also utilizing a Ni(II) catalyst and bipyridinebased ligand (Scheme 2b).24 Over the last decade, ongoing research has greatly expanded the scope of RCC reactions that use Mn0 or Zn0 as the terminal reductant to include many different sec-alkyl electrophiles, including those generated in situ from olefins.25,26

Scheme 2.

First reports of Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of C(sp2) and C(sp3) electrophiles with metal reductants.

III. Mechanistic Considerations

Before the last decade, all examples of Ni-catalyzed asymmetric cross-couplings fell into the category of redox-neutral transformations. Extensive methods development and mechanistic investigations by Fu and coworkers on the enantioconvergent cross-coupling of sec-alkyl electrophiles have demonstrated the feasibility of generating an alkyl radical through halide abstraction by a Ni(I) complex and engaging this species in enantioselective catalysis.27,28 Our group and others hypothesized that mechanistic similarities with enantioconvergent redox-neutral couplings could be leveraged toward the development of enantioselective RCC reactions.

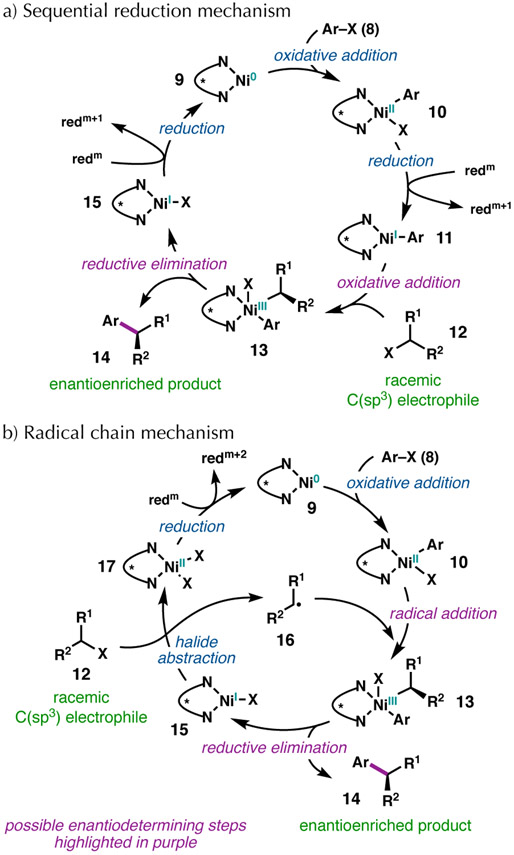

Investigations of Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-couplings have been conducted by several groups and can be organized into two limiting possibilities that are referred to as 1) the sequential reduction mechanism and 2) the radical chain mechanism (Figure 1).29,30 In a sequential reduction mechanism, it is proposed that the C(sp2) electrophile (shown as aryl halide 8 for clarity) undergoes oxidative addition to a Ni(0) species (9) to afford Ni(II)–aryl complex 10,31 which is then reduced by a metal reductant to 11 (Figure 1a).32,33 The Ni(I)–aryl complex (11) can then effect halide abstraction from a racemic sec-alkyl electrophile (12)34 to generate a prochiral radical that undergoes recombination with the metal center to give a Ni(III) intermediate (13).35 Subsequent reductive elimination affords the enantioenriched product (14) and Ni(I)–halide complex 15, which can be reduced to regenerate the Ni(0) catalyst (9) and close the catalytic cycle.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanistic hypotheses.

The second proposed mechanism involves a radical chain process (Figure 1b).36 The C(sp2) electrophile (8) undergoes oxidative addition to Ni(0) complex 9. The resulting Ni(II) intermediate (10) then combines with a cage-escaped sec-alkyl radical (16) to give Ni(III) complex 13,37 which upon reductive elimination gives the enantioenriched product (14) and Ni(I)-halide 15.27 The resulting Ni(I)–halide species (15) can abstract a halide from the C(sp3) electrophile (12) to generate long-lived sec-alkyl radical 16.38 Finally, the Ni(II)–dihalide species (17) can be reduced, regenerating the Ni(0) catalyst (9) to close the catalytic cycle.

A major difference between the sequential reduction and radical chain mechanisms is the lifetime of the alkyl radical generated by halide abstraction, which either reacts via a radical rebound process in the solvent cage (sequential reduction mechanism) or is long-lived and escapes the cage (radical chain reaction mechanism). Experimental and computational data support each mechanism in different systems, suggesting that the mechanism of Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-couplings varies with different substrates, ligands, and reaction conditions.21 It is also possible that similar mechanisms are operative where the C(sp2) electrophile oxidatively adds to a Ni(I) complex, and the cycle does not proceed through reduction of the catalyst to Ni(0).7,26d,39 In any of these scenarios, the enantiodetermining step could be radical addition to a Ni(II) complex to form a single diastereomer of a Ni(III) complex, followed by facile reductive elimination.28b Alternatively, if radical addition to Ni(II) is reversible, then reductive elimination from the Ni(III) species could be the enantiodetermining step.13a,35

IV. Ni-Catalyzed Enantioconvergent RCC Reactions of C(sp2) and C(sp3) Electrophiles

In 2013, our laboratory reported the first highly enantioselective Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling (Scheme 3).40 In this reaction, racemic benzylic chlorides were cross-coupled with acyl chlorides using a Ni(II) pre-catalyst, a chiral bis(oxazoline) (BOX) ligand (L1), and Mn0 as the terminal reductant. High enantioselectivity but low reactivity was observed in THF, whereas DMA provided higher reactivity, but also more homocoupling sideproduct formation. A mixed solvent system of DMA and THF provided the optimal balance of reactivity and selectivity. Importantly, we found that the addition of dimethylbenzoic acid (DMBA) suppressed homocoupling of the C(sp3) electrophile. A variety of functional groups were tolerated on both coupling partners, providing the products in high yield and enantiomeric excess (ee).

Scheme 3.

First report of enantioconvergent RCC.

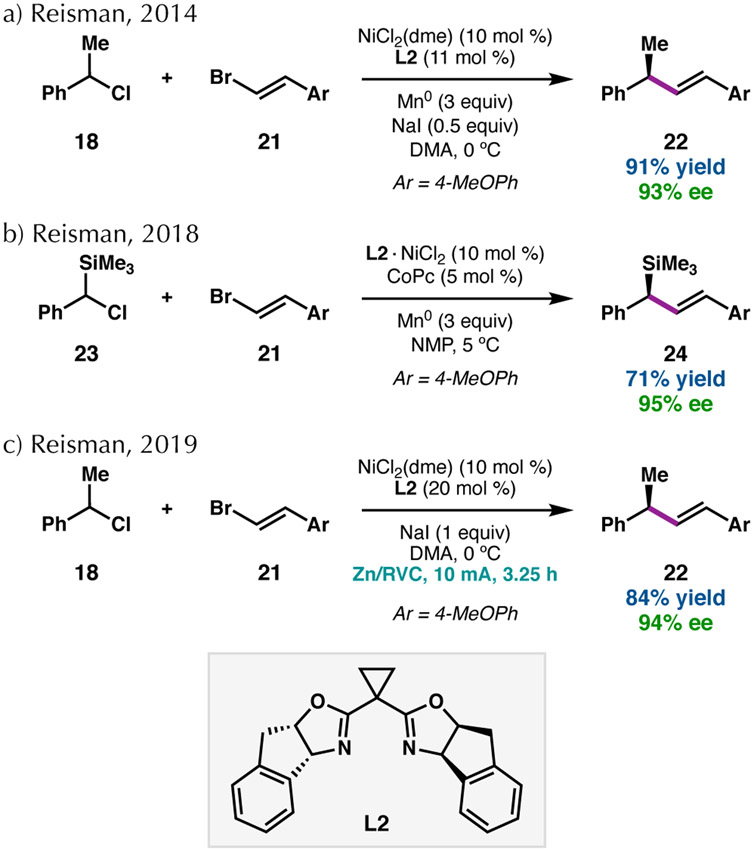

In 2014, we reported a related reaction, in which alkenyl bromides undergo Ni-catalyzed enantioselective RCC with benzylic chlorides (Scheme 4a).41 Chiral BOX L2 was identified as the optimal ligand for this reaction, giving the products bearing allylic stereocenters in excellent ee when the reaction was conducted in DMA. NaI was determined to be an important additive in the reaction, improving the yield of 22 and decreasing the formation of the dibenzyl homodimer. NaI has been suggested to enhance reactivity in reductive cross-couplings through acceleration of electron transfer between Mn0 and Ni or by in situ formation of iodide electrophiles.42 In 2018, this mode of reactivity was extended to chloro(arylmethyl)silanes, allowing access to enantioenriched allylic silanes (Scheme 4b).43 Co-catalysis with cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc) was required for efficient coupling of these bulky silyl electrophiles, presumably to facilitate radical generation.44

Scheme 4.

Enantioconvergent RCCs of alkenyl bromides.

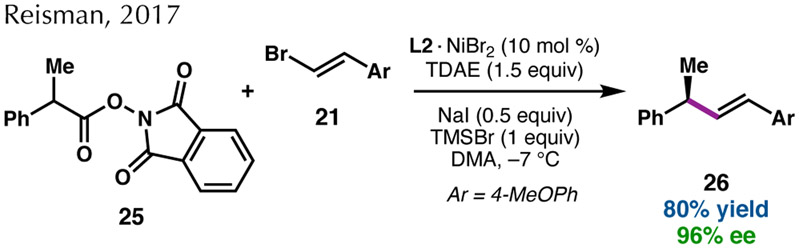

While attempts to render reductive couplings more sustainable and scalable have been reported for racemic coupling reactions, comparable asymmetric efforts are few in number.8,10,11 We have demonstrated that Ni-catalyzed enantioselective reductive alkenylation reactions, such as that between 18 and 21 to give 22, can be driven electrochemically (Scheme 4c).45 In addition, for the Ni-catalyzed asymmetric reductive alkenylation of N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHP) esters,46,47 the best results were obtained with the organic reductant tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE);8,48 Mn0 and Zn0 as the terminal reductants provided significantly lower yield (Scheme 5).49 The coupling of NHP esters was advantageous for improving the scope of electron-rich benzylic systems, where the corresponding benzylic chlorides were unstable. In the NHP ester couplings, a significant amount of (E)-1-(2-chlorovinyl)-4-methoxybenzene was observed when using a chloride-containing precatalyst or TMSCl as an additive, presumably due to a Ni-catalyzed halide exchange process.50 This alkenyl chloride was inert in the cross-coupling reaction; thus, it was necessary to eliminate all sources of chloride in the catalyst and additives to improve the yield.

Scheme 5.

Enantioconvergent reductive decarboxylative cross-coupling.

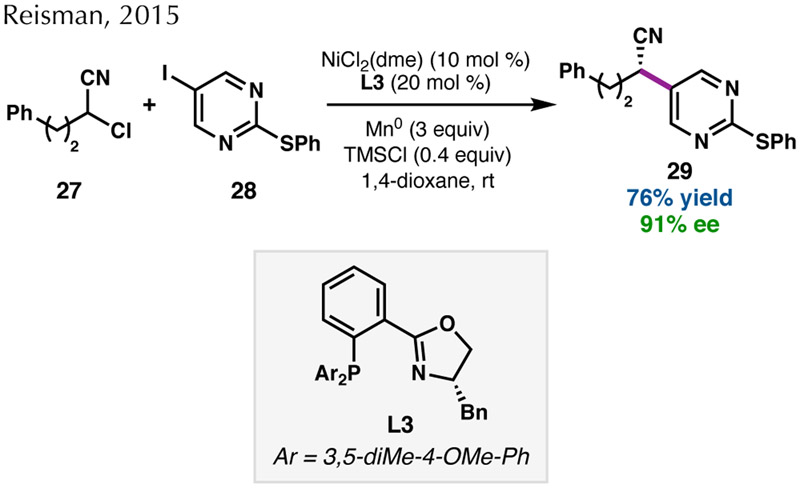

Despite early success with activated C(sp3) coupling partners, variation of the C(sp2) electrophile necessitated chiral ligands outside of the BOX family. In 2015, we published a Ni-catalyzed asymmetric RCC of α-chloronitriles and (hetero)aryl iodides (Scheme 6).51 This reaction required a phosphinooxazoline (PHOX) ligand (L3) and provided high yields and enantioselectivities of the secondary nitrile products when TMSCl was used as an additive.38,52 In the case of diarylalkane formation, the development of a new bioxazoline (BiOX) ligand bearing secondary alkyl substituents with long alkyl chains (L4) was required to obtain good yield and enantioselectivity (Scheme 7a).53 Interestingly, the coupling of either α-chloronitriles or benzylic chlorides with (hetero)aryl iodides worked optimally under similar reaction conditions, but required a different ligand. This highlights the importance of tuning the ligand properties when investigating new electrophile combinations in enantioselective RCC reactions.

Scheme 6.

Enantioconvergent RCC of α-chloronitriles.

Scheme 7.

Enantioconvergent RCCs with a novel BiOX ligand.

Contemporaneously to our development of the diarylakane formation in Scheme 7a, the Doyle and Sigman groups published an enantioselective reductive cross-coupling of racemic styrenyl-derived aziridines and aryl iodides, invoking a similar stereoconvergent mechanism (Scheme 7b).54 Using L4, developed by our lab, 2-arylphenethylamine products were formed with high levels of enantioselectivity. Multivariate analysis of the effect of chiral BiOX ligands on the reaction revealed that ligand polarizability influences the enantioselectivity, suggesting the presence of noncovalent interactions, such as dispersion forces or CH–π interactions, in the selectivity-determining transition state.

BiOX ligand L4 has recently enabled the enantioconvergent RCC of α-chloroesters and aryl iodides (Scheme 7c).55 Photoredox catalyst 1,2,3,5-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene (4CzIPN) was proposed to turn over the Ni catalyst when Hantzsch ester (HEH) was employed as a soluble terminal reductant. Thus, strategic use of photoredox co-catalysts may preclude the generation of stoichiometric metal waste by Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-couplings.

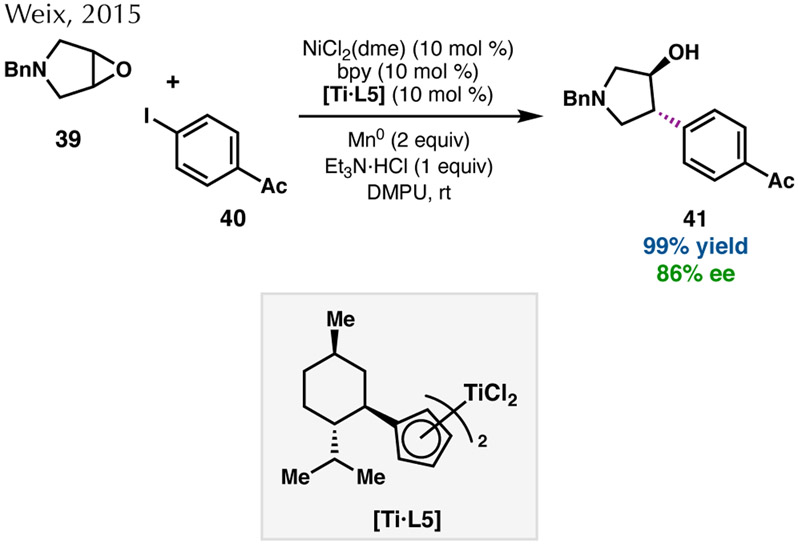

Expanding the scope of alkyl electrophiles for Ni-catalyzed asymmetric RCC reactions, the Weix group published the enantioselective cross-coupling of meso-epoxides and aryl halides (Scheme 8).56,57 A chiral titanocene catalyst ([Ti·L5]) proposed to generate a β-titanoxy carbon radical from a meso- epoxide, which can be intercepted by a Ni(II)–Ar complex arising from an aryl halide. Reductive elimination from the resulting Ni(III) species then gives enantioenriched trans-β-arylcycloalkanols in excellent yields. In this transformation, the enantioselectivity is determined in the epoxide-opening step by the chiral titanocene catalyst.56

Scheme 8.

Enantioconvergent RCC with Ni/Ti co-catalysis.

V. Ni-Catalyzed Enantioselective RCC Reactions of Olefins

Recently, olefins have been employed in enantioselective Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-couplings to forge two C─C bonds and a stereogenic center in one reaction. These dicarbofunctionalizations are advantageous in cases where alkyl (pseudo)halide electrophiles are unstable or require multiple steps to prepare, since the C(sp3) electrophilic fragment is generated directly from an alkene and a C(sp2) halide. Most of the methods to date involve an initial intramolecular addition of a C(sp2) electrophile to an alkene. This represents a potential enantiodetermining step that distinguishes these reactions from non-conjunctive RCCs; in-depth mechanistic investigations will be instructive for future reaction development.

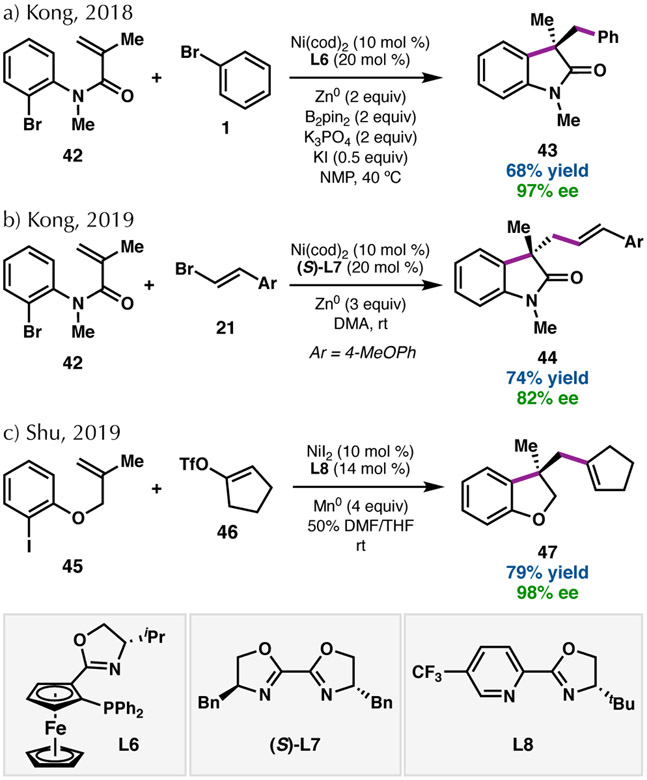

In 2018, Kong and coworkers disclosed the enantioselective 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of activated alkenes to access heterocycles bearing an all-carbon quaternary center (Scheme 9a).58 This 1,2-diarylation required both Zn and B2pin2 as terminal reductants, as well as an iodide source (KI) to improve the yield. A phosphinoferrocenyloxazoline ligand (L6) induced high levels of enantioselectivity of the products, which featured various arene substitution and tolerance of a few sterically bulky groups at the benzylic position. Similar olefin substrates were found to undergo asymmetric 1,2-arylalkenylation with alkenyl bromide coupling partners (Scheme 9b).59 In this case, chiral BiOX L7 could be used in the absence of additives to provide oxindoles in good ee.

Scheme 9.

Enantioselective RCCs of olefins and C(sp2) electrophiles.

In 2019, Shu and coworkers published a related reductive transformation able to couple unactivated olefins with alkenyl triflates (Scheme 9c).60 Making use of a pyridyloxazoline ligand (PyOx, L8), Mn0 as the stoichiometric reductant, and each electrophile in an equimolar amount, this reaction gives heterocyclic products in moderate to good yield and excellent ee. While this transformation successfully coupled a range of aryl substituents on the alkene partner, only 1,1-disubstitution of the alkene was tolerated.

Key to these processes is the ability of the catalyst to sequentially engage the olefin and cross-coupling partner. In a redox-neutral system, Fu and coworkers demonstrated that intermediate organonickel species can rapidly undergo olefin insertion to form a five-membered ring that is able to capture an electrophile in an enantioselective fashion.61 The reductive two-component couplings are thought to proceed via analogous mechanisms.58,60 Oxidative addition of the aryl halide (42 or 45) followed by reduction is proposed to access a Ni(I)–aryl species. This intermediate can undergo migratory insertion of the pendant alkene, which may be the enantiodetermining step. The Ni(I)–alkyl species resulting from this 5-exo-trig cyclization is then poised to undergo oxidative addition of the C(sp2) coupling partner (1 or 46) to furnish final product 43 or 47, respectively, with high levels of enantioselectivity.

C(sp3) electrophiles have also shown competence in olefin RCCs. Wang and coworkers reported the reductive 1,2-arylalkylation and 1,2-arylbenzylation of unactivated olefins to form enantioenriched benzene-fused cyclic products (Scheme 10a,b).62 While chiral BiOX ligand L7 was required for primary bromides,62a the coupling of benzylic chlorides was optimal with PyOx L9.62b These reactions are notable for their ability to form indane products; however, the corresponding tetralins are inaccessible, and tetrahydroisoquinolines were formed with significantly reduced ee, indicating the difficulty of 6-exo-trig cyclization. These limitations highlight an opportunity for development to access products featuring other ring sizes.

Scheme 10.

Enantioselective RCCs of olefins and C(sp3) electrophiles.

Soon after, the Wang group demonstrated the ability to couple styrene-tethered acyl chlorides and C(sp3) electrophiles (Scheme 10c).63 The reaction, which proceeds with Mn0 as terminal reductant, was found to tolerate groups of varying steric bulk at the benzylic position of 54. Competent coupling partners included primary and secondary alkyl iodides and benzyl chloride. Although the heterocyclic products were available in moderate to good yields with PyOx L9, morpholino-substituted PyOx L10 was necessary to obtain good levels of enantioselectivity.

In 2019, the Diao group disclosed the first intermolecular enantioselective 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of activated alkenes, using BiOX L11 (Scheme 11a).64 Interestingly, catalytic amounts of an N-oxyl radical additive (ABNO) enabled the cross-coupling of styrenes and aryl halides to proceed with consistent and high enantioselectivities. Formation of the dibenzyl homodimer of 57 suggests the presence of an intermediate benzylic radical. In addition, stereochemical results and radical clock experiments support a mechanism involving reversible homolysis of the Ni–alkyl bond resulting from olefin migratory insertion, which may precede enantiodetermining reductive elimination.

Scheme 11.

Enantioselective reductive intermolecular cross-coupling of olefins.

In the following year, Chu and coworkers reported the intermolecular reductive coupling of olefins with (hetero)aryl bromides and perfluorinated alkyl iodides (Scheme 11b).65 Use of a pendant directing group facilitated the regiospecific reaction of unactivated alkenes. Chiral BiOX ligands were found to be uniquely effective in this three-component reaction; while previously developed L4 promoted formation of the 1,2-fluoroalkylarylated products in high yields, extending the alkyl chains of the ligand (L12) did not result in enhanced enantioselectivity. This transformation is an important advance from intramolecular olefin RCCs; the difunctionalization of olefins with distinct electrophiles will continue to be an interesting and significant extension of this intermolecular methodology.

VI. Concluding Remarks and Outlook

Efficient C─C bond construction through Ni-catalyzed enantioselective RCC reactions affords valuable enantioenriched small molecules from simple electrophile precursors. We anticipate that addressing several remaining challenges will be required for further advances in the field. The development of new ligand scaffolds will likely be crucial to enhancing the yield and ee of new reactions. Importantly, techniques such as ligand parameterization with multivariate linear regression analysis may draw connections between seemingly scattered data to reveal important trends in reactivity and stereoselectivity. In addition, transitioning away from heterogenous metal reductants may increase industrial use of reductive cross-couplings, as well as facilitate high-throughput screening for development and use of these transformations.

Activated alkyl coupling partners currently dominate the enantioselective RCCs of C(sp2) and C(sp3) electrophiles, and several limitations within this category remain. Ortho-substituted and ortho,ortho-disubstituted benzylic electrophiles exhibit low reactivity, as do those featuring sterically bulky α-substituents.40 The poor stability of electron-rich benzylic halides and α-heteroatom-substituted halides diminishes their utility.4 Unactivated and tertiary halides remain a significant challenge in enantioselective transformations. Thus, diversifying the pool of competent alkyl (pseudo)halide electrophiles is an important future focus.

To access a broader scope of C(sp3) coupling partners that can serve as alkyl radical precursors, radical generation mechanisms other than halogen abstraction should be explored. For example, using synergistic photoredox/Ni catalysis for C─H functionalization is an exciting new direction; however, it has been challenging to render these reactions enantioselective.66,67 Ultimately, the development of new methods of C(sp3) radical generation will improve the accessibility and synthetic utility of enantioselective RCCs.

Reductive olefin dicarbofunctionalization reactions offer strategic complementarity to the RCC of (pseudo)halide electrophiles. In principle, unactivated olefins can be leveraged to forge stereocenters remote from α-stabilizing groups, which would diverge from the reactivity of activated halides. An advantage of using olefin coupling partners is the ability to access all-carbon quaternary centers, which has yet to be realized in enantioconvergent RCCs. Although current methods are restricted to cyclization of five-membered rings as a strategy to effectively discriminate electrophiles, the recent development of intermolecular olefin RCCs suggests that this is not an intrinsic limitation. Further development of formally three-component couplings will rely on deeper mechanistic understanding to address challenges of electrophile differentiation.

Overall, transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions remain an invaluable tool for the synthesis of small molecules and natural products. In particular, Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-couplings have enabled the development of mild reaction conditions that give the desired products in good yields with high levels of enantioselectivity. We are confident that this field will continue to grow and revolutionize the way that carbon–carbon bonds are constructed in an enantioselective manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Fellowship support was provided by the National Science Foundation (graduate research fellowship to K. E. P., S. E. D. Grant No. DGE-1144469). S.E.R. is a Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator. Financial support from the NIH (R35GM118191-01) is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Sources

No competing financial interests have been declared.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Rudolph A; Lautens M Secondary Alkyl Halides in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48 (15), 2656–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jana R; Pathak TP; Sigman MS Advances in Transition Metal (Pd,Ni,Fe)-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions Using Alkyl-Organometallics as Reaction Partners. Chem. Rev 2011, HI (3), 1417–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Tasker SZ; Standley EA; Jamison TF Recent Advances in Homogeneous Nickel Catalysis. Nature 2014, 509 (7500), 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) For selected reviews of reductive cross-couplings, see: Knappke CEI; Grupe S; Gartner D; Corpet M; Gosmini C; Jacobi von Wangelin A Reductive Cross-Coupling Reactions between Two Electrophiles. Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20 (23), 6828–6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weix DJ Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp2 Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48 (6), 1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gu J; Wang X; Xue W; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Alkyl Halides with Other Electrophiles: Concept and Mechanistic Considerations. Org. Chem. Front 2015, 2, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang X; Dai Y; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Couplings. Top. Curr. Chem 2016, 374 (4), 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lucas EL; Jarvo ER Stereospecific and Stereoconvergent Cross-Couplings between Alkyl Electrophiles. Nat. Rev. Chem 2017, 1 (9), 0065. [Google Scholar]; (f) Richmond E; Moran J Recent Advances in Nickel Catalysis Enabled by Stoichiometric Metallic Reducing Agents. Synthesis 2018, 50 (3), 499–513. [Google Scholar]; (g) Goldfogel MJ; Huang L; Weix DJ Cross-Electrophile Coupling: Principles and New Reactions In Nickel Catalysis in Organic Synthesis; Ogoshi S, Ed.; Wiley, 2020; pp 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dombrowski AW; Gesmundo NJ; Aguirre AL; Sarris KA; Young JM; Bogdan AR; Martin MC; Gedeon S; Wang Y Expanding the Medicinal Chemist Toolbox: Comparing Seven C(Sp2)-C(Sp3) Cross-Coupling Methods by Library Synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 11 (4), 597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) For selected examples of Ni-catalyzed intramolecular RCCs, see: Yan C-S; Peng Y; Xu X-B; Wang Y-W Nickel-Mediated Inter- and Intramolecular Reductive Cross-Coupling of Unactivated Alkyl Bromides and Aryl Iodides at Room Temperature. Chem. Eur. J 2012, 18 (19), 6039–6048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xue W; Xu H; Liang Z; Qian Q; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cyclization of Alkyl Dihalides. Org. Lett 2014, 16 (19), 4984–4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Konev MO; Hanna LE; Jarvo ER Intra- and Intermolecular Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions of Benzylic Esters with Aryl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (23), 6730–6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lucas EL; Hewitt KA; Chen P-P; Castro AJ; Hong X; Jarvo ER Engaging Sulfonamides: Intramolecular Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reaction of Sulfonamides with Alkyl Chlorides. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85 (4), 1775–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sanford AB; Thane TA; McGinnis TM; Chen P-P; Hong X; Jarvo ER Nickel-Catalyzed Alkyl–Alkyl Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reaction of 1,3-Dimesylates for the Synthesis of Alkylcyclopropanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (11), 5017–5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yin J; Maguire CK; Yasuda N; Brunskill APJ; Klapars A Impact of Lead Impurities in Zinc Dust on the Selective Reduction of a Dibromoimidazole Derivative. Org. Process Res. Dev 2017, 21 (1), 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Lin Q; Diao T Mechanism of Ni-Catalyzed Reductive 1,2-Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (44), 17937–17948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Diccianni J; Lin Q; Diao T Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions and Applications in Alkene Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53 (4), 906–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Anka-Lufford LL; Huihui KMM; Gower NJ; Ackerman LKG; Weix DJ Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling with Organic Reductants in Non-Amide Solvents. Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22 (33), 11564–11567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Byrne FP; Jin S; Paggiola G; Petchey THM; Clark JH; Farmer TJ; Hunt AJ; Robert McElroy C; Sherwood J Tools and Techniques for Solvent Selection: Green Solvent Selection Guides. Sustain. Chem. Process 2016, 4 (1), 7. [Google Scholar]

- (10).For a recent method showcasing the utility of electrochemistry on scale, see: Perkins RJ; Hughes AJ; Weix DJ; Hansen EC Metal-Reductant-Free Electrochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Couplings of Aryl and Alkyl Bromides in Acetonitrile. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23 (8), 1746–1751. [Google Scholar]

- (11).For a recent large-scale example of heterogenous RCC, see: Nimmagadda SK; Korapati S; Dasgupta D; Malik NA; Vinodini A; Gangu AS; Kalidindi S; Maity P; Bondigela SS; Venu A; Gal-lagher WP; Aytar S; Gonzalez-Bobes F; Vaidyanathan R Devel-opment and Execution of an Ni(II)-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Substituted 2-Chloropyridine and Ethyl 3-Chloropropanoate Org. Process Res. Dev 2020. ASAP. [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Milligan JA; Phelan JP; Badir SO; Molander GA Alkyl Carbon–Carbon Bond Formation by Nickel/Photoredox Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (19), 6152–6163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang H-H; Chen H; Zhu C; Yu S A Review of Enantioselective Dual Transition Metal/Photoredox Catalysis. Sci. China Chem 2020, 63, 637–647. [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) For selected examples of enantioselective photoredox/Ni-catalyzed cross-couplings, see: Gutierrez O; Tellis JC; Primer DN; Molander GA; Kozlowski MC Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Photoredox-Generated Radicals: Uncovering a General Manifold for Stereoconvergence in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (15), 4896–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zuo Z; Cong H; Li W; Choi J; Fu GC; MacMillan DWC Enantioselective Decarboxylative Arylation of α-Amino Acids via the Merger of Photoredox and Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138 (6), 1832–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stache EE; Rovis T; Doyle AG Dual Nickel- and Photoredox-Catalyzed Enantioselective Desymmetrization of Cyclic Meso-Anhydrides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56 (13), 3679–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gandolfo E; Tang X; Roy SR; Melchiorre P Photochemical Asymmetric Nickel-Catalyzed Acyl Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (47), 16854–16858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pezzetta C; Bonifazi D; Davidson RWM Enantioselective Synthesis of N-Benzylic Heterocycles: A Nickel and Photoredox Dual Catalysis Approach. Org. Lett 2019, 21 (22), 8957–8961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Moragas T; Correa A; Martin R Metal-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling Reactions of Organic Halides with Carbonyl-Type Compounds. Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20 (27), 8242–8258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tortajada A; Julia-Hernandez F; Borjesson M; Moragas T; Martin R Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carboxylation Reactions with Carbon Dioxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57 (49), 15948–15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gil A; Fernando A; Alvarez M Role of the Nozaki–Hiyama–Takai–Kishi reaction in the Synthesis of Natural Products. Chem. Rev 2017, 117 (12), 8420–8446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Semmelhack MF; Helquist PM; Jones LD Synthesis with Zerovalent Nickel. Coupling of Aryl Halides with Bis(1,5 Cyclooctadiene)Nickel(0). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1971, 93 (22), 5908–5910. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kende AS; Liebeskind LS; Braitsch DM In Situ Generation of a Solvated Zerovalent Nickel Reagent. Biaryl Formation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16 (39), 3375–3378. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zembayashi M; Tamao K; Yoshida J; Kumada M Nickel-Phosphine Complex-Catalyzed Homo Coupling of Aryl Halides in the Presence of Zinc Powder. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 47, 4089–4092. [Google Scholar]

- (18).(a) For the first reports of metal-mediated reductive homocoupling, see: Wurtz A Sur une nouvelle classe de radicaux organiques. Ann. Chim. Phys 1855, 44, 275–312. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wurtz A Ueber eine neue Klasse organischer Radicale. Ann. Chem. Pharm 1855, 96 (3), 364–375. [Google Scholar]

- (19).For a seminal Ni-catalyzed C(sp2)–C(sp2) cross-selective coupling with a metal reductant, see: Fürstner A; Shi N A Multicomponent Redox System Accounts for the First Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi Reactions Catalytic in Chromium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118 (10), 2533–2534. [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) For the first reports of C(sp2)–C(sp3) cross-couplings with a metal reductant, see: Tollens B; Fittig R Ueber die Synthese der Kohlenwasserstoffe der Benzolreihe. Liebigs Ann. 1864, 131 (3), 303–323. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fittig R; König J Ueber das Aethyl- und Diäthylbenzol. Liebigs. Ann 1867, 144 (3), 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Everson DA; Weix DJ Cross-Electrophile Coupling: Principles of Reactivity and Selectivity. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79 (11), 4793–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Amatore C; Jutand A; Párichon J; Rollin Y Mechanism of the Nickel-Catalyzed Electrosynthesis of Ketones by Heterocoupling of Acyl and Benzyl Halides. Monatsh. Chem 2000, 131 (12), 1293–1304. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Durandetti M; Gosmini C; Perichon J Ni-Catalyzed Activation of α-Chloroesters: A Simple Method for the Synthesis of α-Arylesters and β-Hydroxyesters. Tetrahedron 2007, 63 (5), 1146–1153. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Everson DA; Shrestha R; Weix DJ Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Aryl Halides with Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (3), 920–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) For selected examples of Ni-catalyzed RCCs of C(sp2) and sec-alkyl electrophiles, see: Wu F; Lu W; Qian Q; Ren Q; Gong H Ketone Formation via Mild Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Alkyl Halides with Aryl Acid Chlorides. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 3044–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang S; Qian Q; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Aryl Halides with Secondary Alkyl Bromides and Allylic Acetate. Org. Lett 2012, 14 (13), 3352–3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wotal AC; Weix DJ Synthesis of Functionalized Dialkyl Ketones from Carboxylic Acid Derivatives and Alkyl Halides. Org. Lett 2012, 14 (6), 1476–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao Y; Weix DJ Nickel-Catalyzed Regiodivergent Opening of Epoxides with Aryl Halides: Co-Catalysis Controls Regioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (1), 48–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Molander GA; Traister KM; O’Neill BT Reductive Cross-Coupling of Nonaromatic, Heterocyclic Bromides with Aryl and Heteroaryl Bromides. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79 (12), 5771–5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Arendt KM; Doyle AG Dialkyl Ether Formation via Nickel-Catalyzed Cross Coupling of Acetals and Aryl Iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 9876–9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Molander GA; Traister KM; O’Neill BT Engaging Nonaromatic, Heterocyclic Tosylates in Reductive Cross-Coupling with Aryl and Heteroaryl Bromides. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80 (3), 2907–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Qiu C; Yao K; Zhang X; Gong H Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of α-Halocarbonyl Derivatives with Vinyl Bromides. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14 (48), 11332–11335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Gu J; Qiu C; Lu W; Qian Q; Lin K; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Vinyl Bromides with Unactivated Alkyl Halides. Synthesis 2017, 49 (8), 1867–1873. [Google Scholar]; (j) Gao M; Sun D; Gong H Ni-Catalyzed Reductive C─O Bond Arylation of Oxalates Derived from α-Hydroxy Esters with Aryl Halides. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 1645–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Martin-Montero R; Yatham VR; Yin H; Davies J; Martin R Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Deaminative Arylation at Sp3 Carbon Centers. Org. Lett 2019, 21 (8), 2947–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) For representative examples of Ni-catalyzed RCCs of olefins, see: García-Domínguez A; Li Z; Nevado C Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (20), 6835–6838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuang Y; Wang X; Anthony D; Diao T Ni-Catalyzed Two-Component Reductive Dicarbofunctionalization of Alkenes via Radical Cyclization. Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (20), 2558–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao X; Tu H-Y; Guo L; Zhu S; Qing F-L; Chu L Intermolecular Selective Carboacylation of Alkenes via Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Radical Relay. Nature Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shu W; Garcia-Dominguez A; Quir0s MT; Mondal R; Cardenas DJ; Nevado C Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Dicarbofunctionalization of Nonactivated Alkenes: Scope and Mechanistic Insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (35), 13812–13821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jin Y; Wang C Ni-catalyzed reductive arylalkylation of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 1780–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fu GC Transition-Metal Catalysis of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: A Radical Alternative to SN1 and SN2 Processes. ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3 (7), 692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).(a) Schley ND; Fu GC Nickel-Catalyzed Negishi Arylations of Propargylic Bromides: A Mechanistic Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (47), 16588–16593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yin H; Fu GC Mechanistic Investigation of Enantioconvergent Kumada Reactions of Racemic α-Bromoketones Catalyzed by a Nickel/Bis(Oxazoline) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (38), 15433–15440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Everson DA; Jones BA; Weix DJ Replacing Conventional Carbon Nucleophiles with Electrophiles: Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Alkylation of Aryl Bromides and Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (14), 6146–6159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ren Q; Jiang F; Gong H DFT Study of the Single Electron Transfer Mechanisms in Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Aryl Bromide and Alkyl Bromide. J. Organomet. Chem 2014, 770, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tsou TT; Kochi JK Mechanism of Oxidative Addition. Reaction of Nickel(0) Complexes with Aromatic Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101 (21), 6319–6332. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Amatore Christian; Jutand A Rates and Mechanism of Biphenyl Synthesis Catalyzed by Electrogenerated Coordinatively Unsaturated Nickel Complexes. Organometallics 1988, 7, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Colon I; Kelsey DR Coupling of Aryl Chlorides by Nickel and Reducing Metals. J. Org. Chem 1986, 51 (14), 2627–2637. [Google Scholar]

- (34).(a) Anderson TJ; Jones GD; Vicic DA Evidence for a NiI Active Species in the Catalytic Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 8100–8101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones GD; Martin JL; McFarland C; Allen OR; Hall RE; Haley AD; Brandon RJ; Konovalova T; Desrochers PJ; Pulay P; Vicic DA Ligand Redox Effects in the Synthesis, Electronic Structure, and Reactivity of an Alkyl-Alkyl Cross-Coupling Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 13175–13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diccianni JB; Katigbak J; Hu C; Diao T Mechanistic Characterization of (Xantphos)Ni(I)-Mediated Alkyl Bromide Activation: Oxidative Addition, Electron Transfer, or Halogen-Atom Abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (4), 1788–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lin X; Sun J; Xi Y; Lin D How Racemic Secondary Alkyl Electrophiles Proceed to Enantioselective Products in Negishi Cross-Coupling Reactions. Organometallics 2011, 30 (12), 3284–3292. [Google Scholar]

- (36).For a related proposal of a radical chain mechanism involving π-allyl–Ni complexes, see: Hegedus LS; Miller LL Reaction of Pi-Allylnickel Bromide Complexes with Organic Halides. Stereochemistry and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1975, 97 (2), 459–460. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang X; Ma G; Peng Y; Pitsch CE; Moll BJ; Ly TD; Wang X; Gong H Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Electron-Rich Aryl Iodides with Tertiary Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (43), 14490–14497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Biswas S; Weix DJ Mechanism and Selectivity in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Aryl Halides with Alkyl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (43), 16192–16197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tsou TT; Kochi JK Mechanism of Biaryl Synthesis with Nickel Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101 (25), 7547–7560. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Cherney AH; Kadunce NT; Reisman SE Catalytic Asymmetric Reductive Acyl Cross-Coupling: Synthesis of Enantioenriched Acyclic α,α-Disubstituted Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 7442–7445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cherney AH; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling Between Vinyl and Benzyl Electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 14365–14368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Prinsell MR; Everson DA; Weix DJ Nickel-Catalyzed, Sodium Iodide-Promoted Reductive Dimerization of Alkyl Halides, Alkyl Pseudohalides, and Allylic Acetates. Chem. Commun 2010, 46 (31), 5743–5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hofstra JL; Cherney AH; Ordner CM; Reisman SE Synthesis of Enantioenriched Allylic Silanes via Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (1), 139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ackerman LKG; Anka-Lufford LL; Naodovic M; Weix DJ Cobalt Co-Catalysis for Cross-Electrophile Coupling: Diarylmethanes from Benzyl Mesylates and Aryl Halides. Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 1115–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).DeLano TJ; Reisman SE Enantioselective Electroreductive Coupling of Alkenyl and Benzyl Halides via Nickel Catalysis. ACS Cat. 2019, 9 (8), 6751–6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Huihui KMM; Caputo JA; Melchor Z; Olivares AM; Spiewak AM; Johnson KA; DiBenedetto TA; Kim S; Ackerman LKG; Weix DJ Decarboxylative Cross-Electrophile Coupling of N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters with Aryl Iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5016–5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ni S; Padial NM; Kingston C; Vantourout JC; Schmitt DC; Edwards JT; Kruszyk MM; Merchant RR; Mykhailiuk PK ; Sanchez BB; Yang S; Perry MA; Gallego GM; Mousseau JJ; Collins MR; Cherney RJ; Lebed PS; Chen JS; Qin T; Baran PS A Radical Approach to Anionic Chemistry: Synthesis of Ketones, Alcohols, and Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (16), 6726–6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Kuroboshi M; Tanaka M; Kishimoto S; Goto K; Mochizuki M; Tanaka H Tetrakis(dimethylamino)- ethylene (TDAE) as a Potent Organic Electron Source: Alkenylation of Aldehydes Using a Ni/Cr/TDAE Redox System. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41 (1), 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Suzuki N; Hofstra JL; Poremba KE; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters with Vinyl Bromides. Org. Lett 2017, 19 (8), 2150–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).(a) Takagi K; Hayama N; Inokawa S Synthesis of Vinyl Iodides from Vinyl Bromides and Potassium Iodide by Means of Nickel Catalyst. Chem. Lett 1978, 7 (12), 1435–1436. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsou TT; Kochi JK Nickel Catalysis in Halogen Exchange with Aryl and Vinylic Halides. J. Org. Chem 1980, 45 (10), 1930–1937. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hofstra JL; Poremba KE; Shimozono AM; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Conversion of Enol Triflates into Alkenyl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (42), 14901–14905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Kadunce NT; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling between Heteroaryl Iodides and α-Chloronitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10480–10483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).(a) Takai K; Ueda T; Hayashi T; Moriwake T Activation of Manganese Metal by a Catalytic Amount of PbCl2 and Me3SiCl. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37 (39), 7049–7052. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson KA; Biswas S; Weix DJ Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Vinyl Halides with Alkyl Halides. Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22 (22), 7399–7402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Poremba KE; Kadunce NT; Suzuki N; Cherney AH; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling to Access 1,1-Diarylalkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (16), 5684–5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Woods BP; Orlandi M; Huang C-Y; Sigman MS; Doyle AG Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Cross-Coupling of Styrenyl Aziridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (16), 5688–5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Guan H; Zhang Q; Walsh PJ; Mao J Nickel/Photoredox-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Cross-Coupling of Racemic α-Chloro Esters with Aryl Iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59 (13), 5172–5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Zhao Y; Weix DJ Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of Meso-Epoxides with Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (9), 3237–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).A related reductive cross-coupling of chiral 3,4-epoxyalcohols with aryl iodides affords 1,1-diaryldiol products with enriched ee; see: Banerjee A; Yamamoto H Nickel Catalyzed Regio-, Diastereo-, and Enantioselective Cross-Coupling of 3,4-Epoxyalcohol with Aryl Iodides. Org. Lett 2017, 19 (16), 4363–4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Wang K; Ding Z; Zhou Z; Kong W Ni-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Diarylation of Activated Alkenes by Domino Cyclization/Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (39), 12364–12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Li Y; Ding Z; Lei A; Kong W Ni-Catalyzed enantioselective reductive aryl-alkenylation of alkenes: application to the synthesis of (+)-physovenine and (+)-physostigmine. Org. Chem. Front 2019, 6 (18), 3305–3309. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Tian Z-X; Qiao J-B; Xu G-L; Pang X; Qi L; Ma W-Y; Zhao Z-Z; Duan J; Du Y-F; Su P; Liu X-Y; Shu X-Z Highly Enantioselective Cross-Electrophile Aryl-Alkenylation of Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (18), 7637–7643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Cong H; Fu GC Catalytic Enantioselective Cyclization/Cross-Coupling with Alkyl Electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (10), 3788–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).(a) Jin Y; Wang C Ni-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Arylalkylation of Unactivated Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 6722–6726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jin Y; Yang H; Wang C Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Arylbenzylation of Unactivated Alkenes. Org. Lett 2020, 22 (7), 2724–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lan Y; Wang C Nickel-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Carbo-Acylation of Alkenes. Comm. Chem. 2020, 3 (1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Anthony D; Lin Q; Baudet J; Diao T Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Diarylation of Vinylarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (10), 3198–3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Tu HY; Wang F; Hou L; Li Y; Zhu S; Zhao X; Li H; Qing FL; Chu L Enantioselective Three-Component Fluoroalkylarylation of Unactivated Olefins Through Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (21), 9604–9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).(a) For isolated examples of enantioselective photoredox/Ni-catalyzed C─H functionalization, see: Ahneman DT; y AG C─H functionalization of amines with aryl halides by nickel-photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci 2016, 7 (12), 7002–7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen Y; Gu Y; Martin R Sp3 C─H Arylation and Alkylation Enabled by the Synergy of Triplet Excited Ketones and Nickel Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (38), 12200–12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rand AW; Yin H; Xu L; Giacoboni J; Martin-Montero R; Romano C; Montgomery J; Martin R Dual Catalytic Platform for Enabling Sp3 α C─H Arylation and Alkylation of Benzamides. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (8), 4671–4676. [Google Scholar]

- (67).(a) For seminal examples of enantioselective photoredox/Ni-catalyzed C─-H functionalization, see: Cheng X; Lu H; Lu Z Enantioselective Benzylic C─H Arylation via Photoredox and Nickel Dual Catalysis. Nature Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fan P; Lan Y; Zhang C; Wang C Nickel/Photo-Cocatalyzed Asymmetric Acyl-Carbamoylation of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (5), 2180–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]