Abstract

Sulfur mustard (SM) is a highly toxic blistering agent thought to mediate its action, in part, by activating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the skin and disrupting components of the basement membrane zone (BMZ). Type IV collagenases (MMP-9) degrade type IV collagen in the skin, a major component of the BMZ at the dermal-epidermal junction. In the present studies, a type IV collagenase inhibitor, N-hydroxy-3-phenyl-2-(4-phenylbenzenesulfonamido) propanamide (BiPS), was tested for its ability to protect the skin against injury induced by SM in the mouse ear vesicant model. SM induced inflammation, epidermal hyperplasia and microblistering at the dermal/epidermal junction of mouse ears 24–168 h post-exposure. This was associated with upregulation of MMP-9 mRNA and protein in the skin. Dual immunofluorescence labeling showed increases in MMP-9 in the epidermis and in the adjacent dermal matrix of the SM injured skin, as well as breakdown of type IV collagen in the basement membrane. Pretreatment of the skin with BiPS reduced signs of SM-induced cutaneous toxicity; expression of MMP-9 mRNA and protein was also downregulated in the skin by BiPS. Following BiPS pretreatment, type IV collagen appeared intact and was similar to control skin. These results demonstrate that inhibiting type IV collagenases in the skin improves basement membrane integrity after exposure to SM. BiPS may hold promise as a potential protective agent to mitigate SM induced skin injury.

Keywords: sulfur mustard, basement membrane, type IV collagen, MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor

Introduction

Sulfur mustard (bis-2-chloroethylsulfide, SM), a highly toxic bifunctional alkylating agent known to target the skin, has been used in chemical warfare. SM can rapidly penetrate the skin causing inflammation and extensive blistering after a latent period of 2–24 h, depending on the dose and time of exposure. Wound healing following exposure to SM is often delayed (Graham and Schoneboom, 2013). Blisters induced by SM are thought to originate at the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) in the basement membrane (BM); many of the characteristics of these blisters are similar to blisters observed in human genetic skin blistering diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa (Uitto et al., 1997; Chang et al., 2018a). Damage to basal keratinocytes is a characteristic of cutaneous injury induced by SM. Disruption of BM components that attach basal keratinocytes to the BMZ can lead to epidermal-dermal separation resulting in blister formation (Petrali and Oglesby-Megee, 1997; Monteiro-Riviere et al., 1999). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) regulate the degradation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and BM proteins during cutaneous injury, inflammation, and wound healing (Martins et al., 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2015). However, overexpression of MMPs can exacerbate tissue damage induced by SM leading to delayed wound repair (Gerecke et al., 2009; Malaviya et al., 2010; Reiss et al., 2010; Shakarjian et al., 2010; Benson et al., 2011; Gordon et al., 2016). In earlier studies we demonstrated that preferential expression of MMP-9 in SM injured skin is an important mediator of blister formation; this suggests that targeting MMP-9 may be an effective therapeutic approach for mitigating SM-induced skin damage (Shakarjian et al., 2006).

Type IV collagen represents ~50% of basement membrane proteins and is crucial for basement membrane stability. Unlike fibrillar collagens types I, II, III, and V, Type IV collagen forms a continuous network structure and assembles with laminin polymers into a functional basement membrane (Yurchenco and Furthmayr, 1984; Kalluri, 2003; Mak and Mei, 2017). Multiple diseases are associated with the degradation of collagen IV including epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, Alport syndrome and Goodpastur’s syndrome (Hudson et al., 2003; Abreu-Velez and Howard, 2012). Infiltrating inflammatory cells and resident skin cells are known to secrete MMP-9 during injury. MMP-9 released following SM exposure can efficiently degrade type IV collagen, laminin, and their receptors within the ECM to remodel the basement membrane (Zeng et al., 1999; Ortega and Werb, 2002; Tanjore and Kalluri, 2006; Veidal et al., 2011; Sand et al., 2013; Rousselle and Scoazec, 2020).

MMP-9 has been of interest as a potential target to mitigate diseases affecting the BM as well as SM injury. Levels of MMP-9 are raised in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) blisters, and treatment with minocycline, an antibiotic that is also an MMP inhibitor, partly improves this syndrome (Leung et al., 2015; Rashidghamat and McGrath, 2017). In mouse models of Alport syndrome, treatment with MMP inhibitors, such as MMI270, attenuate MMP-mediated ECM degradation and provide protection against glomerular basement membrane (GBM) degradation (Gratton et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2006; Zeisberg et al., 2006). Several in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that MMP inhibitors can reduce SM-induced toxicity. For example, doxycycline, which is also an MMP inhibitor, showed anti-inflammatory effects and protection against SM-induced toxicity in models of pulmonary and ocular injury (Guignabert et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2010; Horwitz et al., 2014). Treatment of HEK keratinocytes with doxycycline has also been reported to reduce SM-induced IL-8 production; in contrast, doxycycline does not protect against SM-induced decreases in viability in HaCaT cells (Nicholson et al., 2004; Lindsay et al., 2008) and has no effect on microvesication in SM exposed human skin explants (Schultz et al 2004). However, Ilomastat, a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor, has shown partial suppression of microvesication in the human skin explants exposed to SM (Schultz et al., 2004).

In the present studies, we evaluated a selective MMP-9 inhibitor, N-hydroxy-3-phenyl-2-(4-phenylbenzenesulfonamido) propanamide (BiPS), for its ability to mitigate SM-induced skin injury in the mouse ear vesicant model (see Fig 1 for the structure of BiPS). BiPS was found to suppress both skin inflammation and degradation of the BMZ. These data suggest that collagenase inhibitors may be effective countermeasures for vesicant-induced cutaneous injury.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of BiPS.

BiPS [(2R)-[(4-biphenylylsulfonyl)amino]-N-hydroxy-3-phenylpropionamide] is an MMP-9 inhibitor.

Materials and methods

Animal treatments

Male CD1 mice (25–35 g, Charles River Laboratories, Portage, MI) were treated with SM at Battelle Biomedical Research Center (West Jefferson, OH, USA) as previously described (Chang et al., 2013). All animals received humane care in compliance with the institution’s guidelines, as outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health. Animal protocols were approved by the Battelle Memorial Institute animal care and use committee. Briefly, anesthetized mice were treated topically with 5 μl of a solution of 97.5 mM SM diluted in methylene chloride on the ventral (inner) side of the right ear. The left ear served as a control and received only the vehicle. For time-course studies, mice were sacrificed 24, 72 and 168 h post SM exposure and punch biopsies (8 mm in diameter) of control and treated ear skin collected. Punch biopsies were weighed and either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70° C for RNA analysis or fixed in neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for histologic analysis. In some experiments, mice were treated topically at the site of SM exposure with 20 μl of a 25 mM solution of BiPS (MMP-2/MMP-9 Inhibitor II, Calbiochem, SanDiego, CA) in ethanol. Control treatments consisted of 20 μl ethanol. In all experiments, pre-treatment of mice with BiPS occurred at 15 min prior to exposure to SM.

RNA isolation and Real-Time PCR analysis

Analysis of RNA from punch biopsies was previously described (Chang et al., 2018b). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol according to the manufacturer instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For RT-PCR analysis, mRNA was transcribed into cDNA using a superscript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen), a minus reverse transcriptase reaction was included as a control. RT-PCR was performed with a TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Assay-by-Design, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using Assay by Design Primer/Probe sets for MMP-9 (Accession number: Z27231; Forward Primer: ACCAGGATAAACTGTATGGCTTCTG; Reverse Primer: ACAGCTCTCCTGCCGAGTTG; Probe Sequence: TACCCGAGTGGACGCG;) and for hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) (Accession number: NM_013556; Forward Primer: CAGTACAGCCCCAAAATGGTTAA; Reverse Primer: AACACTTCGAGAGGTCCTTTTCAC; Probe Sequence: CAGCAAGCTTGCAACC). Expression of HGPRT mRNA served as an endogenous control. Samples were analyzed on an ABI 7900 PCR system (Applied Biosystems) in technical triplicate and normalized to HGPRT. The untreated control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and treated samples were calculated relative to untreated controls. Expression of mRNA was reported as a fold change (mean ± SEM, n = 10).

Histology

Paraffin embedded tissues sections were cut into 7 μM sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and then scanned on an Olympus VS120 Virtual Scanning Microscope (Olympus Co., Waltham, MA). For skin thickness measurements, three random sites from each tissue section within the wound area were analyzed. Dermal thickness was assessed as the distance from the DEJ to the cartilage. The mean dermal thickness (MDT) was calculated and analyzed for significance at p<0.05 using the unpaired Student’s t test (n = 7–10 per group). The relative mean dermal edema thickness (RDET) percentage was also calculated [(MDT of treated – MDT of unexposed vehicle control) / MDT of unexposed vehicle control x 100].

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Unstained tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and immersed in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). To unmask epitopes, tissue sections were either heated in a microwave oven or incubated with Trypsin Enzymatic Antigen Tissue Retrieval solution (Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA) for 10 min at 37° C. Sections were then blocked with 5–10% normal donkey serum (NDS), washed, and incubated overnight at 4° C with goat anti-collagen IV α−1 antibody (COL4 α1, catalog number NBP1–26549, Novus Biologicals, LLC, Centennial, CO) diluted 1:50 in PBS/0.05% Tween-20/1.5 % NDS) and/or a rabbit anti-MMP-9 (catalog number ab19016, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) diluted 1:500 in PBS/0.05% Tween-20/1.5 % NDS). After washing, tissue sections were stained with either donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) or donkey anti-rabbit Dylight 549 (Jackson Immunos, PA), respectively, for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Tissue sections were mounted in ProLong Gold with DAPI anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and coverslips applied to cure overnight. Confocal images were collected using a Zeiss 510 LSM Confocal Microscope.

Statistical analysis

Expression of mRNA and mean dermal thickness were analyzed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test or non-paired student t test comparing naïve unexposed controls to SM exposed samples; a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

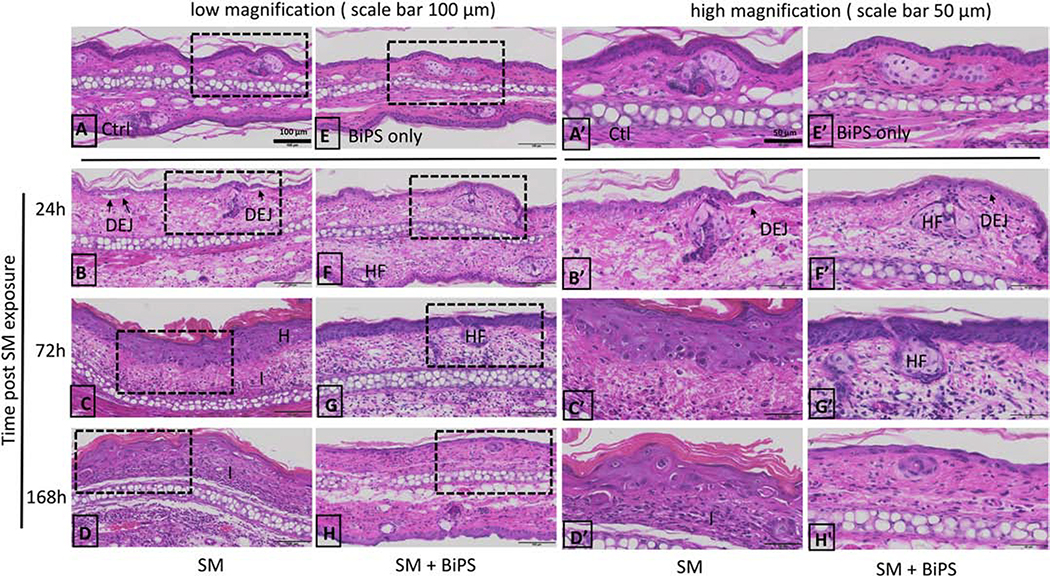

Effects of SM on mouse ear skin

In control tissue, the epidermis of the ventral (inner surface) and dorsal (outer surface) ear skin was 1–2 cells thick, a thin stratum corneum was also evident (Fig. 2A). Hair follicles and sebaceous glands were scattered throughout the dermis. The ventral and dorsal ear skin was separated by auricular cartilage. The tissue contained an uninterrupted DEJ between the epidermis and dermis in both the ventral and dorsal sides of the ear (Fig. 2A). Twenty-four hours post SM exposure, the formation of microvesicles was apparent with separation of the epidermis and the dermis (indicated by arrows in Fig. 2B). Epidermal edema, an influx of inflammatory cells, and hyperplasia with a thickening stratum corneum was also evident (Fig 2C). Tissue injury persisted up to 168 h post SM (Fig. 2D). Representative images of the ventral, SM treated ear skin, at a higher magnification showed morphological changes of the superficial region of damaged skin (Fig 2A’–2D’). At 24 h post SM exposure, skin damage was apparent with pyknotic basal cells (shrunken and dark), intracellular epidermal edema, inflammatory cells, and the formation of microvesicles/microblisters at the DEJ (shown in a higher magnification, Fig 2B’). Hyperplasia with disorganized hypertrophic basal cells, hyperkeratosis with thickening of the stratum corneum, and clusters of inflammatory cells in the dermis was prevalent 72–168 h post SM (shown in a higher magnification, Fig 2C’ and 2D’).

Fig. 2. Structural alterations in mouse ear skin following SM exposure.

H&E stained histological sections of control mouse ear skin and SM-treated mouse ear skin. Images shown in Panels A-H are at low magnification (scale bar = 100 μm). Images shown in Panels A’-H’ are high magnification (scale bar = 50 μm); Panels A’-H’ show images from the dashed boxed area of images panels A-H. Tissues were collected 24 h, 72 h and 168 h post-SM exposure. Panels A and A’, control mouse ear skin (Ctl); panels B-D and B’-D’, mouse ear skin treated with SM; E and E’, mouse ear skin treated with BiPS alone without SM exposure (BiPS only); panels F-H and F’-H’, mouse ear skin treated with BiPS and SM; panels. DEJ: dermal-epidermal junction; H: hyperplasia; HF: hair follicles; I: inflammatory cell infiltration. Black arrows indicate separation of DEJ in damaged skin 24 h post SM exposure. All images of the mouse ear skin were oriented with the ventral (inner, treated side) surface at the top.

Effects of BiPS on SM-induced injury in mouse ear skin

Initially, we examined the effects of BiPS on SM-induced skin edema as measured by changes in dermal thickness. On the ventral surface of ear skin, where SM was applied, the mean dermal thickness (MDT) increased from 65 μm in control skin to 135–166 μm in SM treated skin 24–72 h post exposure (Fig. 3A). The mean dermal thickness (MDT) of the dorsal surface of ear skin also increased from 87 μm in control ears to 213–289 μm in SM treated ears 24–72 h post exposure (Fig. 3B). To correct for edema induced by vehicles, the relative dermal edema thickness percentage (RDET%), which represents increases in skin thickness following SM-exposure relative to vehicle control, was calculated. Edema in the dorsal, non-treated surface of the ear was 2–3 times greater than in the ventral, SM treated surface of the ears (Table 1). Vehicle-induced edema was not observed or was insignificant. As observed in MDT, edema as reflected by RDET%, increased with time culminating in a 231% increase in the dorsal skin at 168 h post exposure (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Effects of SM and BiPS on skin thickness.

Mean dermal thickness of the ventral (inner surface) ear skin (panel A) and dorsal (outer surface) ear skin (panel B) were measured in control mice and in mice 24 h, 72 h, and 168 h post SM exposure. Control skin (blue bar), SM exposed skin (red bars), BiPS + SM treated skin (green bars), and skin treated with BiPS alone (purple bars). Data was analyzed for statistical significance using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test or non-pair student t-test. Dermal thickness was presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 8–10). *, p < 0.05 when compared to naïve control samples; †, p < 0.05 when compared to SM exposed skin.

Table 1.

Effects of BiPS on the relative dermal edema thickness following SM-induced injury. Relative dermal edema thickness (RDET%) was used as an edema index in this study. RDET% was calculated to correct for vehicle-induced edema. The RDET% of the BiPS + SM samples showed statistically significant reduction in edema by > 50%, when compared to SM exposed only samples.

| Time post SM exposure | RDET% |

RDET% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventral (inner car) skin |

Dorsal (outer car) skin |

|||

| SM | BiPS + SM | SM | BiPS + SM | |

| 24 h | 118.9 | 50.8 | 144.4 | 45.1 |

| 72 h | 156.3 | 92.3 | 217.2 | 182.3 |

| 168 h | 108.6 | 93.3 | 231.3 | 86.8 |

BiPS pre-treatment decreased SM-induced dermal thickening by approximately one third in the ventral skin surface at 24 h and 72 h post treatment (Fig. 3A). The decrease in edema was also apparent in the dorsal skin at 24 h post SM exposure (Fig. 3B). By 168 h post SM exposure, BiPS caused a substantial reduction of RDET% in the dorsal skin, from 231% to 86% (Table 1). BiPS was also found to attenuate structural damage caused by SM (Fig. 2, panels F–H and panels F’–H’). Mouse ears treated with BiPS alone were similar to naïve unexposed control tissue (Fig. 2E and 2E’). Fewer microblisters were evident in the DEJ of the BiPS + SM treated skin when compared to SM treated skin 24 h post exposure (Fig. 2F and 2F’). Basal cells also appeared more organized and hair follicles were prevalent in BiPS treated skin 72–168 h BiPS + SM post exposure when compared to SM treated skin (Fig. 2 G–H and G’–H’). A significant reduction in epidermal hyperplasia was also evident in the SM + BiPS treated skin (Fig. 2 H and 2H’).

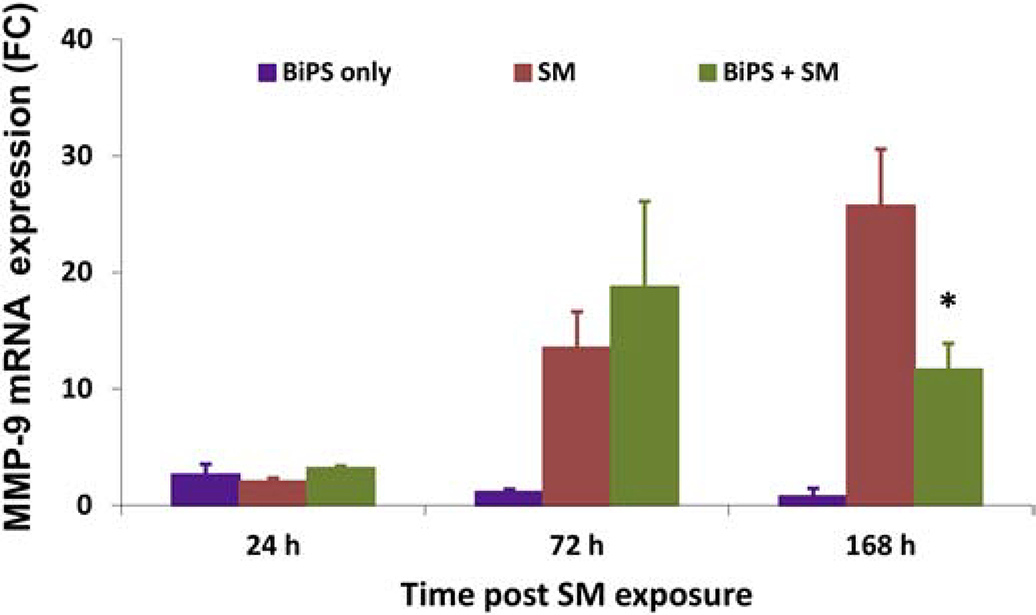

Effect of SM on MMP-9 mRNA expression in mouse ear skin

Treatment of mouse ear skin with SM resulted in increased mRNA expression of MMP-9; this response was time related continuing for at least 168 hr post exposure (Fig. 4). Pre-treatment of mouse ear skin with BiPS downregulated MMP-9 mRNA expression by approximately 50% at 168 h post SM exposure (Fig 4).

Fig. 4. Effects of SM on MMP-9 mRNA expression in mouse ear skin.

SM treatment is shown in red, BiPS + SM is shown in green, and BiPS alone is shown in purple. Fold changes are normalized to unexposed control samples. Fold changes were analyzed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test or non-pair student t-test. Data are expressed as fold changes over time and are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 8–10); a p value of<0.05 was considered statistically significant and marked with *, when compared to control skin.

Effects of SM on expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen protein in mouse ear skin

We next examined protein expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen in skin following SM exposure. Immunofluorescence analysis showed expression of MMP-9 increased with time after SM exposure (Fig. 5). Expression was notable in the hyperplastic epidermis and hair follicles of the ventral mouse ear skin (Fig. 5B–5D). MMP-9 was also expressed in the basal epithelium, as well as in the matrix of the superficial dermis near the DEJ of SM treated skin. Expression of MMP-9 was also observed in the dorsal ear skin, with similar expression patterns as in the ventral ear skin (Fig. 5F–5H).

Fig. 5. Confocal images of MMP-9 expression following treatment of mouse ear skin with SM.

MMP-9 was visualized using a primary antibody to MMP-9 and a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (shown in red); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue). Data on the ventral (inner) surface of mouse ear skin is shown in the top panels (panels A-D) and the dorsal (outer) surface of mouse ear skin on the lower panels (panels E-H). Images were oriented with epidermis (Epi) on top and dermis on the bottom. The basement membrane is denoted by a broken line between epidermis and dermis. Panels A and E, control mouse ear skin; panels B and F, mouse ear skin 24 h post SM exposure; panels C and G, mouse ear skin 72 h post SM exposure (MMP-9 expression indicated by arrows); panels D and H, mouse ear skin 168 h post SM exposure. All panels are presented at the same magnification, scale bar = 10 μm.

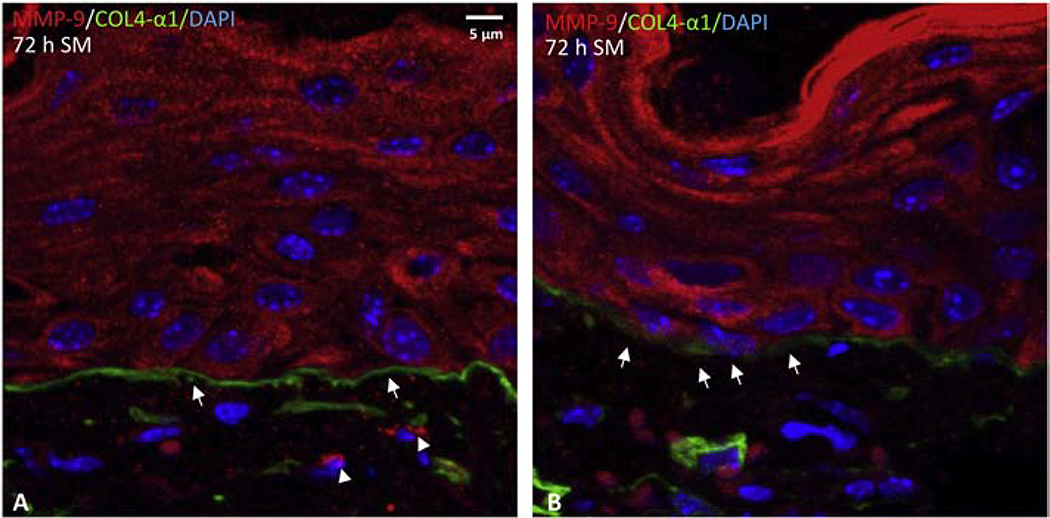

By dual antibody labeling, we next determined if MMP-9 co-localized with type IV collagen in mouse ear skin. In naïve, unexposed control skin, a continuous expression pattern of type IV collagen was observed in the basement membrane along the DEJ of mouse ear skin (Figure 6A and 6B). Conversely, there was only limited basal expression of MMP-9 (Figure 6C and 6D). Co-expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen was not observed in either the ventral or dorsal ear skin (Figure 6). Twenty-four hours after SM exposure, increased expression of MMP-9 was evident in keratinocytes, as well as in inflammatory cells and fibroblasts in the dermis near the basement membrane DEJ (Figure 7A and 7B). The expression of type IV collagen appeared disrupted with a punctate pattern in the basement membrane of the SM-exposed skin as denoted by white arrows in Figure 7A and 7B. Co-expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen was evident in the dermis adjacent to the basement membrane (white dotted circle in Figure 7A and 7B). By 72 h post SM exposure, a substantial increase of MMP-9 was evident. Expression of MMP-9 was observed throughout all layers of hyperplastic epithelium. MMP 9 was also evident in the extracellular matrix of the dermis and near the DEJ in the basement membrane (indicted by arrow heads in Figure 8A). The punctate expression of type IV collagen was often observed in the DEJ 72 h post SM exposure (Figure 8B).

Fig. 6. Expression of type IV collagen and MMP-9 in mouse ear skin.

Dual immunofluorescence labeling was used to visualize MMP-9 and type IV collagen in control skin. MMP-9 is shown in red, and type IV collagen is shown in green (indicated by arrow heads); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and are shown in blue. Both the ventral side (panels A and C) and dorsal side (panels B and D) of the tissue shows an uninterrupted pattern of type IV collagen expression in the basement membrane, as denoted by white arrow heads. Panels A and B are the same magnification, scale bar = 10 μm. Higher magnification images are shown in panels C and D, scale bar = 5 μm.

Fig. 7. Effects of SM on type IV collagen and MMP-9 expression mouse ear skin.

Dual immunofluorescence labeling was used to visualize MMP-9 and type IV collagen in skin 24 h post SM exposure (scale bar = 5 μm): MMP-9 is shown in red, and type IV collagen is shown in green; nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and are shown in blue. Note the punctate pattern of type IV collagen expression in the basement membrane (white arrows). Co-expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen appeared in the dermis adjacent to the basement membrane (white dotted circle).

Fig. 8. Effects of SM on type IV collagen and MMP-9 expression mouse ear skin.

Dual immunofluorescence was used to visualize MMP-9 and type IV collagen in skin 72 h post SM exposure (scale bars = 5 μm): MMP-9 is shown in red (indicated by arrow heads), and type IV collagen is shown in green (indicated by arrows); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and are shown in blue.

Effects of BiPS on expression of MMP-9 and type IV collagen in mouse ear skin following SM exposure

MMP-9 expression was reduced in the epidermis and the extracellular matrix by BiPS in SM treated ventral ear skin (Figure 9E–9G). Type IV collagen in the DEJ of the basement membrane was similar to that observed in the naïve unexposed control skin (dotted line arrows, Figure 9A, and 9E–9G). BiPS also attenuated MMP-9 expression on the dorsal ear skin post SM treatment; a reduction in MMP-9 expression was evident in the epidermis, and dermal appendages (Figure 10E–10G). An uninterrupted expression pattern of type IV collagen was also prominent in the basement membrane from dorsal skin treated with BiPS (dotted line arrows, Figure 10E–10G).

Fig. 9. Effects of BiPS on MMP-9 and type IV collagen expression in the ventral or inner surface of mouse ear skin post SM exposure.

Confocal images of MMP-9 (shown in red), type IV collagen (shown in green) and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue). Data of the control sample are shown in panel A. Top panels show SM exposed skin after 24 h, 72 h, and 168 h (panels B-D); bottom panels show SM exposed skin treated with BiPS after 24 h, 72 h, and 168 h (panels E-G). Arrows with broken lines show uninterrupted expression pattern of type IV collagen in the basement membrane (panel A and E). Area showing punctate expression of type IV collagen in the basement membrane is indicated by larger arrow heads (panel B). Images are oriented with epidermis (Epi) on top and dermis on the bottom; shown at the same magnification (scale bar = 10 μm).

Fig. 10. Effects of BiPS on MMP-9 and type IV collagen expression in the dorsal or outer surface of mouse ear skin post SM exposure.

Confocal images of MMP-9 (shown in red), type IV collagen (shown in green) and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue). Data from control sample are shown in panel A. Top panels show SM exposed skin after 24 h, 72 h and 168 h (panels B-D); bottom panels show SM exposed skin treated with BiPS after 24 h, 72 h and 168 h (panels E-G). Arrows with broken lines show uninterrupted expression pattern of type IV collagen in the basement membrane (panel A and E). Area showing punctate expression of type IV collagen in the basement membrane is indicated by larger arrow heads (panel B). Images are oriented with epidermis (Epi) on top and dermis on the bottom; shown at the same magnification (scale bar = 10 μm).

Discussion

The precise mechanism by which exposure of skin to SM leads to blister formation are not well understood. It is generally thought that blistering is caused by the separation of the epidermis from the basement membrane due to the degradation of the anchoring components in the DEJ, particularly, extracellular matrix proteins (Papirmeister et al., 1985). This appears to be due to the release of proteases in the tissue following SM-induced injury (Higuchi et al., 1988; Woessner et al., 1990; Rikimaru et al., 1991; Cowan and Broomfield, 1993; Cowan et al., 1993; Powers et al., 2000; Cowan et al., 2002). MMPs, a class of calcium-dependent zinc-containing proteases, are required to degrade ECM proteins; they facilitate keratinocyte migration during wound repair. Eexcessive and prolonged production of MMPs can cause tissue damage leading to chronic wounds, inflammatory skin diseases, and subepidermal blistering (Woessner et al., 1990; Amano, 2016; Rousselle et al., 2019). In particular, MMP-9, once secreted and activated at the site of a skin lesion, has been shown to cleave DEJ anchoring proteins and degrade several additional ECM molecules including integrins, laminins and type IV collagen (LeBert et al., 2015; Pittayapruek et al., 2016; Hiroyasu et al., 2019). That MMP-9 is important to the process of DEJ separation is indicated by the fact that deficiencies in this enzyme prevent blister formation in a mouse model of bullous pemphigoid (Liu et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2005).

The present studies show that MMP-9 expression is elevated at sites of SM-induced epidermal erosions in the mouse ear; these data are consistent with earlier studies showing increased MMP-9 mRNA in mouse skin, weanling pig skin, and in a full-thickness human skin model following exposure to SM (Sabourin et al., 2002; Shakarjian et al., 2006; Ries et al., 2009). In a mouse model, increases in gelatinase activity and protein expression of MMP-9 (gelatinase B), but not MMP2 (gelatinase A), have also been reported to increase with time in skin following SM exposure (Shakarjian et al., 2006). Our immunohistochemistry studies also showed that MMP-9 was largely generated by basal keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts, and infiltrating inflammatory cells following exposure to SM. Thus, protease production by each of these cell types can contribute to the degradation of ECM proteins in the DEJ and basement membrane. It should be noted that in this mouse ear skin model, although SM exposure was only applied to the ventral side of mouse ear skin, increased edema and elevation of MMP-9 expression were also observed on the dorsal side of mouse ear skin. This suggests that SM can penetrate through the ear cartilage from the ventral treated side to the dorsal untreated side of mouse ear skin and cause tissue injury. Alternatively, SM may induce tissue inflammation throughout the ear skin due to the release of inflammatory mediators including cytokines, growth factors and lipids following initial injury (Dannenberg et al., 1985; Casillas et al., 1997; Sabourin et al., 2000; Gerecke et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2018b).

Of interest were our findings of focal losses of the α1 chain of type IV collagen within the epithelial DEJ and adjacent to the SM wounded sites following administration of SM. These data are consistent with earlier studies using techniques in immune electron microscopy which showed either the absence of type IV collagen or diffuse type IV staining in the DEJ following SM treatment in the mouse ear vesicant model (Monteiro-Riviere et al., 1999). Type IV collagen and MMP-9 co-localize in the matrix near the DEJ-basement membrane, which suggests MMP-9 associates with and degrades type IV collagen. This is supported by previous studies using the mouse ear vesicant model and weanling pig skin models which showed that the cleavage plane associated with blister formation is in the lamina lucida of the basement membrane; this has also been observed in human subepidermal bullous diseases (Pardo and Penneys, 1990; Smith et al., 1997; Monteiro-Riviere et al., 1999). Type IV collagen is located in the lamina densa of the basement membrane just beneath the lamina lucida. This indicates that in SM-induced blistering, MMP-9 causes degradation of type IV collagen, destabilizing the basement membrane which leads to detachment of the epidermis from the basal lamina.

Pre-treatment of mouse skin with the MMP-9 inhibitor, BiPS, caused a marked reduction in SM-induced edema in mouse ear skin, as well as decreases in degradation of the BMZ. BiPS pretreatment reduced levels of COX2, which generates inflammatory mediators, and infiltration of inflammatory cells in SM skin wounds (Chang et al., 2020). These data are consistent with the notion that SM-induced skin injury and epidermal damage is mediated, at least in part, by MMP-9. We also found that BiPS reduced SM-induced MMP-9 mRNA and protein expression in the skin. A question arises as to how inhibiting MMP-9 can cause alterations in expression of MMP-9 mRNA and protein in the skin. As a direct acting enzyme inhibitor, BiPS suppresses MMP-9 activity and limits degradation of type IV collagen, laminin-332 and other components of the ECM and this contributes to its ability to suppress SM toxicity. However, ECM and collagen degradation products are known to be proinflammatory and can stimulate cells to produce proteases including MMP-9 (Bellon et al., 2004; Weathington et al., 2006; Adair-Kirk and Senior, 2008; Manicone and McGuire, 2008; Arroyo and Iruela-Arispe, 2010). These proteolytic fragments can also induce production of cytokines and chemokines, mediators that not only regulate tissue expression of proteinases such as MMP-9, but also recruit neutrophils and macrophages to sites of tissue injury which release proteases (Kessenbrock et al., 2010; Hiroyasu et al., 2019). Thus, it appears that in addition to directly inhibiting MMP-9 enzyme activity, BiPS suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators that induce MMP-9, as well as MMP-9 generated by infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages. It should be noted that, besides proteolytic fragments, many other proinflammatory mediators including prostaglandins and leukotrienes which are generated in tissues following SM-induced damage can induce mediators that regulate inflammatory cell infiltration as well as cytokine and chemokine production. MMP-9 generated as a result of these mediators may also be a target for BiPS. In addition, induction of MMP9 may stimulate its own positive feedback loop. Positive feedback regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) expression has been reported in an MMP dependent manner (Zucker et al., 2000; Huber et al., 2019). Co-culture of EMMPRIN-positive tumor cells with fibroblast cells resulted in concomitant stimulation of MMP-9 and EMMPRIN expression (Tang et al., 2004). Several studies have shown that inhibiting ADAM17 lowered EMMPRIN expression resulting in reduced MMP-9 in mustard treated corneal organ cultures (DeSantis-Rodrigues et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2016). We speculate that EMMPRIN/MMP-9 induction and feedback loop stimulation may also play a role in vesicant-induced skin injury.

Treatment with MMP inhibitors such as doxycycline and GM6001 (Ilomastat) have been previously tested in mustard tissue injury. Doxycycline is a derivative of tetracycline that has shown potent inhibitory effects against a wide range of MMPs including MMP-8 (IC50=30 μM) and MMP-1 (IC50=300 μM). Pretreatment of doxycycline administered via subcutaneous injection, showed inhibitory effect in reducing lung mustard injury (Guignabert et al., 2005). For SM-dermal studies, MMP inhibitors have shown therapeutic potentials in human skin in vitro and ex vivo models. For instance, Ilomastat, a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor, has been reported to decrease microvesication in human skin in vitro and in an ex vivo model (Schultz et al., 2004; Mol et al., 2009). In contrast, Ilomastat was not effective in a mustard hairless guinea pig skin model, possibly due to a need for a delivery system to localize the drug at the site of injury (Mol and Van den Berg, 2006). Poor performance of MMP inhibitors in cancer studies has been attributed to a lack of selectivity of MMP inhibition, poor pharmacokinetics, and in vivo instability (Fields, 2019). In the present studies, BiPS, a highly selective MMP-9 inhibitor (IC50 = 0.03 μM), was protective against SM in the mouse ear vesicant model (MEVM). BiPS was designed and synthesized with a sulfonamide moiety (Fig. 1), which contributes to an excellent pharmacokinetic profile and selective inhibition of MMP-9 (Tamura et al., 1998). In comparison to other MMP inhibitors, pretreatment of BiPS markedly reduced dermal-epidermal separation by selectively targeting MMP-9, and showed protection effect against SM induced skin injury.

In summary, SM readily induces tissue damage in the mouse ear vesicant model. This is associated with degradation of ECM components including collagen IV resulting in disruption of the BMZ. Pre-treatment of the skin with BiPS, an MMP-9 inhibitor, protects against SM-induced damage to the basement membrane and suppresses inflammation and tissue injury. These findings suggest that BiPS may hold promise as an effective countermeasures for vesicant-induced cutaneous injury.

Highlights.

SM readily induces MMP9 mediated tissue damage in the mouse ear vesicant model.

MMP9 is associated with disruption of the BMZ in SM-induced tissue injury.

BiPS, an MMP9 inhibitor, was pretreated on SM exposed mouse skin to target MMP9.

BiPS protects against BMZ damage and suppresses cutaneous injury induced by SM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert Casillas (Latham BioPharm Group, Kansas City, MO) for a critical review of the manuscript and helpful discussions. This research was supported by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD), and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), grant number U54AR055073. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the federal government. This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants P30ES005022, and T32ES007148.

Grant sponsor(s): ES005022, T32ES007148, and NIAMS U54AR055073

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu-Velez AM, Howard MS, 2012. Collagen IV in Normal Skin and in Pathological Processes. N Am J Med Sci 4, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM, 2008. Fragments of extracellular matrix as mediators of inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40, 1101–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano S, 2016. Characterization and mechanisms of photoageing-related changes in skin. Damages of basement membrane and dermal structures. Exp Dermatol 25 Suppl 3, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo AG, Iruela-Arispe ML, 2010. Extracellular matrix, inflammation, and the angiogenic response. Cardiovasc Res 86, 226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon G, Martiny L, Robinet A, 2004. Matrix metalloproteinases and matrikines in angiogenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 49, 203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JM, Seagrave J, Weber WM, Santistevan CD, Grotendorst GR, Schultz GS, March TH, 2011. Time course of lesion development in the hairless guinea-pig model of sulfur mustard-induced dermal injury. Wound Repair Regen 19, 348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas RP, Mitcheltree LW, Stemler FW, 1997. The mouse ear model of cutaneous sulfur mustard injury. Toxicol. Methods 7, 381–397. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y-C, Muhn S, Hahn RA, Gordon MK, Gerecke DR, 2020. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) Inhibitor Prevents Mustard Induced Microvesication and Promotes Cutaneous Wound Healing. The FASEB Journal 34, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Gordon MK, Gerecke DR, 2018a. Expression of Laminin 332 in Vesicant Skin Injury and Wound Repair. Clin Dermatol (Wilmington) 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Soriano M, Hahn RA, Casillas RP, Gordon MK, Laskin JD, Gerecke DR, 2018b. Expression of cytokines and chemokines in mouse skin treated with sulfur mustard. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 355, 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Wang JD, Svoboda KK, Casillas RP, Laskin JD, Gordon MK, Gerecke DR, 2013. Sulfur mustard induces an endoplasmic reticulum stress response in the mouse ear vesicant model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 268, 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan FM, Broomfield CA, 1993. Putative roles of inflammation in the dermatopathology of sulfur mustard. Cell Biol Toxicol 9, 201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan FM, Broomfield CA, Smith WJ, 2002. Suppression of sulfur mustard-increased IL-8 in human keratinocyte cell cultures by serine protease inhibitors: implications for toxicity and medical countermeasures. Cell Biol Toxicol 18, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan FM, Yourick JJ, Hurst CG, Broomfield CA, Smith WJ, 1993. Sulfur mustard-increased proteolysis following in vitro and in vivo exposures. Cell Biol Toxicol 9, 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg AM Jr., Pula PJ, Liu LH, Harada S, Tanaka F, Vogt RF Jr., Kajiki A, Higuchi K, 1985. Inflammatory mediators and modulators released in organ culture from rabbit skin lesions produced in vivo by sulfur mustard. I. Quantitative histopathology; PMN, basophil, and mononuclear cell survival; and unbound (serum) protein content. Am J Pathol 121, 15–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis-Rodrigues A, Chang YC, Hahn RA, Po IP, Zhou P, Lacey CJ, Pillai A, S, C.Y., Flowers RA 2nd, Gallo MA, Laskin JD, Gerecke DR, Svoboda KK, Heindel ND, Gordon MK, 2016. ADAM17 Inhibitors Attenuate Corneal Epithelial Detachment Induced by Mustard Exposure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57, 1687–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields GB, 2019. The Rebirth of Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors: Moving Beyond the Dogma. Cells 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerecke DR, Chen M, Isukapalli SS, Gordon MK, Chang YC, Tong W, Androulakis IP, Georgopoulos PG, 2009. Differential gene expression profiling of mouse skin after sulfur mustard exposure: Extended time response and inhibitor effect. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 234, 156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MK, DeSantis-Rodrigues A, Hahn R, Zhou P, Chang Y, Svoboda KK, Gerecke DR, 2016. The molecules in the corneal basement membrane zone affected by mustard exposure suggest potential therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1378, 158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MK, Desantis A, Deshmukh M, Lacey CJ, Hahn RA, Beloni J, Anumolu SS, Schlager JJ, Gallo MA, Gerecke DR, Heindel ND, Svoboda KK, Babin MC, Sinko PJ, 2010. Doxycycline hydrogels as a potential therapy for ocular vesicant injury. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 26, 407–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JS, Schoneboom BA, 2013. Historical perspective on effects and treatment of sulfur mustard injuries. Chem Biol Interact 206, 512–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Rao VH, Meehan DT, Askew C, Cosgrove D, 2005. Matrix metalloproteinase dysregulation in the stria vascularis of mice with Alport syndrome: implications for capillary basement membrane pathology. Am J Pathol 166, 1465–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignabert C, Taysse L, Calvet JH, Planus E, Delamanche S, Galiacy S, d’Ortho MP, 2005. Effect of doxycycline on sulfur mustard-induced respiratory lesions in guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289, L67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi K, Kajiki A, Nakamura M, Harada S, Pula PJ, Scott AL, Dannenberg AM Jr., 1988. Proteases released in organ culture by acute dermal inflammatory lesions produced in vivo in rabbit skin by sulfur mustard: hydrolysis of synthetic peptide substrates for trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like enzymes. Inflammation 12, 311–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroyasu S, Turner CT, Richardson KC, Granville DJ, 2019. Proteases in Pemphigoid Diseases. Front Immunol 10, 1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz V, Dachir S, Cohen M, Gutman H, Cohen L, Fishbine E, Brandeis R, Turetz J, Amir A, Gore A, Kadar T, 2014. The beneficial effects of doxycycline, an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases, on sulfur mustard-induced ocular pathologies depend on the injury stage. Curr Eye Res 39, 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Attili/Abedalkhader R, Kuper D, Hauke L, Luns B, Brand K, Weissenborn K, Lichtinghagen R, 2019. Cellular and Molecular Effects of High-Molecular-Weight Heparin on Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Expression. Int J Mol Sci 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG, 2003. Alport’s syndrome, Goodpasture’s syndrome, and type IV collagen. N Engl J Med 348, 2543–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R, 2003. Basement membranes: structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 3, 422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z, 2010. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 141, 52–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBert DC, Squirrell JM, Rindy J, Broadbridge E, Lui Y, Zakrzewska A, Eliceiri KW, Meijer AH, Huttenlocher A, 2015. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 modulates collagen matrices and wound repair. Development 142, 2136–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Kuzel P, Kurian A, Brassard A, 2015. A Case of Dominant Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Responding Well to an Old Medication. JAMA Dermatol 151, 1264–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay CD, Gentilhomme E, Mathieu JD, 2008. The use of doxycycline as a protectant against sulphur mustard in HaCaT cells. J Appl Toxicol 28, 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Li N, Diaz LA, Shipley M, Senior RM, Werb Z, 2005. Synergy between a plasminogen cascade and MMP-9 in autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest 115, 879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Shipley JM, Vu TH, Zhou X, Diaz LA, Werb Z, Senior RM, 1998. Gelatinase B-deficient mice are resistant to experimental bullous pemphigoid. J Exp Med 188, 475–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak KM, Mei R, 2017. Basement Membrane Type IV Collagen and Laminin: An Overview of Their Biology and Value as Fibrosis Biomarkers of Liver Disease. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 300, 1371–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaviya R, Sunil VR, Cervelli J, Anderson DR, Holmes WW, Conti ML, Gordon RE, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, 2010. Inflammatory effects of inhaled sulfur mustard in rat lung. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 248, 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicone AM, McGuire JK, 2008. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19, 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins VL, Caley M, O’Toole EA, 2013. Matrix metalloproteinases and epidermal wound repair. Cell Tissue Res 351, 255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol MA, van den Berg RM, Benschop HP, 2009. Involvement of caspases and transmembrane metalloproteases in sulphur mustard-induced microvesication in adult human skin in organ culture: directions for therapy. Toxicology 258, 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol MAE, Van den Berg RM, 2006. Inhibitors of matrix metalloproteases and caspases are potential countermeasures against sulfur mustard exposure of skin, Proceedings of the U.S. Army Medical Defense Bioscience Review, Hunt Valley, MD, pp. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO, Babin MC, Casillas RP, 1999. Immunohistochemical characterization of the basement membrane epitopes in bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide-induced toxicity in mouse ear skin. J Appl Toxicol 19, 313–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JD, Cowan FM, Bergeron RJ, Brimfield AA, Baskin SI, Smith WJ, 2004. Doxycycline and HBED iron chelator decrease IL-8 production by sulfur mustard exposed human keratinocytes, Proceedings of the U.S. Army Medical Defense Bioscience Review, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega N, Werb Z, 2002. New functional roles for non-collagenous domains of basement membrane collagens. J Cell Sci 115, 4201–4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papirmeister B, Gross CL, Meier HL, Petrali JP, Johnson JB, 1985. Molecular basis for mustard-induced vesication. Fundam Appl Toxicol 5, S134–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo RJ, Penneys NS, 1990. Location of basement membrane type IV collagen beneath subepidermal bullous diseases. J Cutan Pathol 17, 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrali JP, Oglesby-Megee S, 1997. Toxicity of mustard gas skin lesions. Microsc Res Tech 37, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittayapruek P, Meephansan J, Prapapan O, Komine M, Ohtsuki M, 2016. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Photoaging and Photocarcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JC, Kam CM, Ricketts KM, Casillas RP, 2000. Cutaneous protease activity in the mouse ear vesicant model. J Appl Toxicol 20 Suppl 1, S177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VH, Meehan DT, Delimont D, Nakajima M, Wada T, Gratton MA, Cosgrove D, 2006. Role for macrophage metalloelastase in glomerular basement membrane damage associated with alport syndrome. Am J Pathol 169, 32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidghamat E, McGrath JA, 2017. Novel and emerging therapies in the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Intractable Rare Dis Res 6, 6–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss MJ, Han YP, Garcia E, Goldberg M, Yu H, Garner WL, 2010. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 delays wound healing in a murine wound model. Surgery 147, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries C, Popp T, Egea V, Kehe K, Jochum M, 2009. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and release from skin fibroblasts interacting with keratinocytes: Upregulation in response to sulphur mustard. Toxicology 263, 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikimaru T, Nakamura M, Yano T, Beck G, Habicht GS, Rennie LL, Widra M, Hirshman CA, Boulay MG, Spannhake EW, et al. , 1991. Mediators, initiating the inflammatory response, released in organ culture by full-thickness human skin explants exposed to the irritant, sulfur mustard. J Invest Dermatol 96, 888–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Montmasson M, Garnier C, 2019. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol 75–76, 12–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Scoazec JY, 2020. Laminin 332 in cancer: When the extracellular matrix turns signals from cell anchorage to cell movement. Semin Cancer Biol 62, 149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin CL, Danne MM, Buxton KL, Casillas RP, Schlager JJ, 2002. Cytokine, chemokine, and matrix metalloproteinase response after sulfur mustard injury to weanling pig skin. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 16, 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin CL, Petrali JP, Casillas RP, 2000. Alterations in inflammatory cytokine gene expression in sulfur mustard-exposed mouse skin. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 14, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand JM, Larsen L, Hogaboam C, Martinez F, Han M, Rossel Larsen M, Nawrocki A, Zheng Q, Karsdal MA, Leeming DJ, 2013. MMP mediated degradation of type IV collagen alpha 1 and alpha 3 chains reflects basement membrane remodeling in experimental and clinical fibrosis--validation of two novel biomarker assays. PLoS One 8, e84934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz GS, Mol MAE, Galardy RE, Friel GE, 2004. Protease inhibitor treatment of sulfur mustard injuries in cultured human skin., Proceedings of the U.S. Army Medical Defense Bioscience Review, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, pp. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Shakarjian MP, Bhatt P, Gordon MK, Chang YC, Casbohm SL, Rudge TL, Kiser RC, Sabourin CL, Casillas RP, Ohman-Strickland P, Riley DJ, Gerecke DR, 2006. Preferential expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in mouse skin after sulfur mustard exposure. J Appl Toxicol 26, 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakarjian MP, Heck DE, Gray JP, Sinko PJ, Gordon MK, Casillas RP, Heindel ND, Gerecke DR, Laskin DL, Laskin JD, 2010. Mechanisms mediating the vesicant actions of sulfur mustard after cutaneous exposure. Toxicol Sci 114, 5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Casillas R, Graham J, Skelton HG, Stemler F, Hackley BE Jr., 1997. Histopathologic features seen with different animal models following cutaneous sulfur mustard exposure. J Dermatol Sci 14, 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura Y, Watanabe F, Nakatani T, Yasui K, Fuji M, Komurasaki T, Tsuzuki H, Maekawa R, Yoshioka T, Kawada K, Sugita K, Ohtani M, 1998. Highly selective and orally active inhibitors of type IV collagenase (MMP-9 and MMP-2): N-sulfonylamino acid derivatives. J Med Chem 41, 640–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Kesavan P, Nakada MT, Yan L, 2004. Tumor-stroma interaction: positive feedback regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) expression and matrix metalloproteinase-dependent generation of soluble EMMPRIN. Mol Cancer Res 2, 73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjore H, Kalluri R, 2006. The role of type IV collagen and basement membranes in cancer progression and metastasis. Am J Pathol 168, 715–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J, Pulkkinen L, McLean WH, 1997. Epidermolysis bullosa: a spectrum of clinical phenotypes explained by molecular heterogeneity. Mol Med Today 3, 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veidal SS, Karsdal MA, Nawrocki A, Larsen MR, Dai Y, Zheng Q, Hagglund P, Vainer B, Skjot-Arkil H, Leeming DJ, 2011. Assessment of proteolytic degradation of the basement membrane: a fragment of type IV collagen as a biochemical marker for liver fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 4, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathington NM, van Houwelingen AH, Noerager BD, Jackson PL, Kraneveld AD, Galin FS, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Blalock JE, 2006. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat Med 12, 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner JF Jr., Dannenberg AM Jr., Pula PJ, Selzer MG, Ruppert CL, Higuchi K, Kajiki A, Nakamura M, Dahms NM, Kerr JS, et al. , 1990. Extracellular collagenase, proteoglycanase and products of their activity, released in organ culture by intact dermal inflammatory lesions produced by sulfur mustard. J Invest Dermatol 95, 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Murphy G, Troeberg L, 2015. Extracellular regulation of metalloproteinases. Matrix Biol 44–46, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco PD, Furthmayr H, 1984. Self-assembly of basement membrane collagen. Biochemistry 23, 1839–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M, Khurana M, Rao VH, Cosgrove D, Rougier JP, Werner MC, Shield CF 3rd, Werb Z, Kalluri R, 2006. Stage-specific action of matrix metalloproteinases influences progressive hereditary kidney disease. PLoS Med 3, e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng ZS, Cohen AM, Guillem JG, 1999. Loss of basement membrane type IV collagen is associated with increased expression of metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9) during human colorectal tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 20, 749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Cao J, Chen WT, 2000. Critical appraisal of the use of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Oncogene 19, 6642–6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]