Abstract.

Quality of care is essential for improving health outcomes, but heterogeneity in theoretical frameworks and metrics can limit studies’ generalizability and comparability. This research aimed to compare definitions of care quality across research articles that incorporate data from Service Provision Assessment (SPA) surveys. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines, we used a keyword search in PubMed. Each author reviewed abstracts, then full texts, for inclusion criteria, and peer-reviewed publications of empirical analysis using SPA data. The search yielded 3,250 unique abstracts, and 34 publications were included in the final analysis. We extracted details on the SPA dataset(s) used, theoretical framework applied, and how care quality was operationalized. The 34 included articles used SPA data from 14 surveys in nine countries (all in sub-Saharan Africa plus Haiti). One-third of these articles (n = 13) included no theoretical or conceptual framework for care quality. Among those articles referencing a framework, the most common was the Donabedian model (n = 7). Studies operationalized quality constructs in extremely different ways. Few articles included outcomes as a quality construct, and the operationalization of structure varied widely. A key asset of SPA surveys, owing to the standardized structure and use of harmonized data collection instruments, is the potential for cross-survey comparisons. However, this is limited by the lack of a common framework for measuring and reporting quality in the existing literature using SPA data. Service Provision Assessment surveys offer unique and valuable insights, and a common framework and approach would substantially strengthen the body of knowledge on quality of care in low-resource settings.

INTRODUCTION

Quality of care is necessary for improving health outcomes.1 Low-quality health systems may be responsible for up to 8.6 million deaths annually in low- and middle-income countries; that is, these deaths could have been averted with utilization of high-quality care.2 Improvements in population health will require high-quality health care over the lifespan, as global life expectancy increases and is accompanied by a growing burden of chronic noncommunicable disease.3,4 This is particularly true in the context of universal health coverage.5,6

The definition of “quality of care” has evolved over several decades. A seminal definition of healthcare quality was developed by Avedis Donabedian (1966) and is a widely used model for measuring care quality as a function of structure, process, and outcomes.7 In the 1990s, Judith Bruce and Anrudh Jain introduced a framework for assessing family planning care quality that focused on the client perspective.8 Subsequent definitions and frameworks for identifying and measuring elements of quality have also been expanded and refined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the WHO,9 including IOM’s quality of care framework that identifies six domains of healthcare quality10 and WHO’s framework for quality of maternal and newborn care.11 Definitions are not merely semantic; they serve as the foundation for conceptual frameworks, which in turn can inform research by identifying variables of interest, formulating hypotheses for the connections between these, and devising ways to operationalize variables during data collection and analysis.12–14

One approach to measuring care quality in global health is the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) survey, which is administered by the Demographic and Health Surveys program. Service Provision Assessment surveys systematically collect information about health facilities in participating countries,15 are nationally representative, and have been conducted in 12 countries since 2004 (20 surveys have been conducted in total). (Before 2004, SPA surveys were focused on specific constructs only, such as HIV care or maternal and child health.) A key strength of SPA surveys is the use of standardized data collection tools, which enables multi- and cross-country analyses,16 and the comprehensive collection of information from several sources: health facility infrastructure, health workers, availability of specific health services, components of clinical care (as directly observed by data collectors), and client opinions of services received. Service Provision Assessment surveys have four overarching aims: to describe service availability, to describe readiness to provide services (infrastructure, resources, and support systems), to assess whether standards of care (quality and content) are followed during service delivery, and whether clients and providers are satisfied.15

The objective of this analysis was to examine how care quality has been studied using SPA data. Measurement of quality is important for the global community and is a key objective of SPA surveys. There have been other systematic reviews of quality of care measurement using SPA data, but these have been narrowly topic-specific (e.g., maternal and child health care or family planning only17–19). We took a broader approach in conducting a systematic review of the literature to collate all information on how SPA data have been used to study quality of care, including theoretical frameworks and definitions used and how these have been operationalized. Although there are a number of existing health facility assessment tools,20 SPA surveys include a broad capture of data elements reflecting different aspects of care quality (including facility assessments, interviews with health workers, observations of care delivery and counseling practices, and exit interview with clients) across multiple types of health services and are publicly available and widely used, so constituted the tool of interest here.

METHODS

Literature search.

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines, we used a keyword search for articles published since 2004 (the date of the first comprehensive, i.e., not topic-specific, SPA survey) in PubMed (see search details in Supplemental Appendix 1). The search was conducted in January 2018. No language restriction was applied. All results were exported to Covidence software, and duplicates were removed.

Article selection.

Each author reviewed abstracts and deemed whether the abstract should be excluded. The criterion for exclusion was if an article clearly did not use SPA data for an empirical analysis that was published as a peer-reviewed article. The first 10% of titles and abstracts were screened by both authors, to attain inter-rater reliability; after this, the authors screened independently. Next, for non-excluded abstracts, full texts were retrieved for these publications. Each author reviewed a portion of these full texts (using the same exclusion criterion); 10% of full texts were screened by both authors before independent screening. Non-English language publications were translated using Google Translate.

Data extraction.

C. M. extracted data from the eligible full-text publications based on a predefined data extraction form. Covidence software was used for data extraction. Data elements extracted were details on the SPA dataset(s) used in the article, theoretical framework applied, and how care quality was operationalized.

Data analysis.

Informed by the Donabedian framework, the variables used to operationalize care quality in each article were classified as relating to the constructs of structure, process, or outcomes. Within structure, six key domains were then identified: infrastructure; staffing; service availability; supplies, medicines, and equipment; monitoring; and protocols and guides. The specific variables or data elements referenced in every included article were mapped to each of these domains, plus the domains within process and outcomes. These were tallied, and counts were compared across constructs and domains.

RESULTS

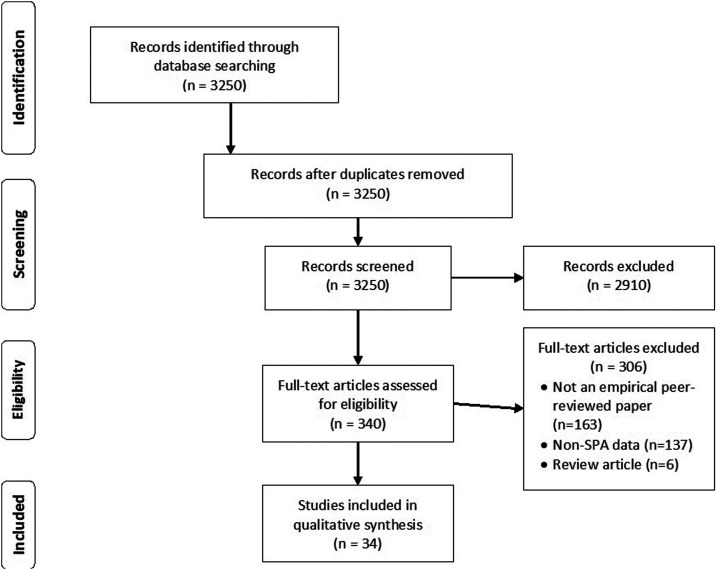

The search strategy yielded 3,250 unique abstracts to review; after screening abstracts, 2,910 were excluded and 340 were selected for full-text screening (Figure 1). Ultimately, 34 studies were included in this analysis (a list of all included studies is included in Supplemental Appendix 2). The reasons for exclusion during full-text screening were not being a peer-reviewed empirical article or not including any data or empirics (n = 163), including non-SPA data (n = 137), and being a review article or meta-analysis (n = 6).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis diagram for article selection process.

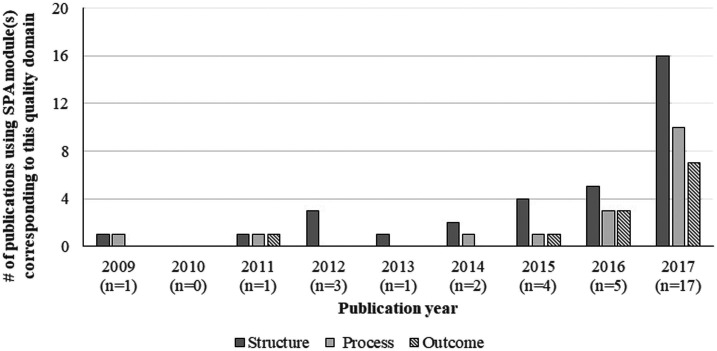

The number of publications using SPA data to explore quality of care has increased dramatically over time (Figure 2). There is also increasing use of multiple SPA modules: health facility and provider interviews (corresponding to structure aspects of quality), service observation (process aspects of quality), and client exit interview (contributed to process and outcome aspects of quality). All but one included article used the facility interview dataset, 21 used the provider interview dataset, 18 used at least one observation dataset, and 12 used the exit interview dataset.

Figure 2.

Publication trends over time, 2009–2017 (n = 34).

The Kenya 2010 SPA dataset was most commonly used (in over half of the included articles), and approximately 30% of articles used Tanzania 2006, Namibia 2009, Rwanda 2007, or Uganda 2007 (see Supplemental Appendix 3 for per-survey counts). There are some SPA surveys that did not appear in our search results (i.e., Bangladesh 2014 and Nepal 2015). Just over half (56%, n = 19) of the included publications used just one SPA dataset, whereas the remaining 44% (n = 15) used more than one; this exact pattern held even among the most recent articles (published in 2016 and 2017: 12 were single-survey articles and 10 were multicountry articles).

One-third of the included articles (n = 13, 38%) were informed by no theoretical or conceptual framework for care quality. Among those articles referencing a framework (n = 21), the most common was the Donabedian model (used by seven studies); an additional 12 studies used alternative existing frameworks, such as the WHO quality of care framework for maternal and newborn care,11 the Primary Health Care Performance Initiative Framework,21 and WHO “building blocks” of health systems framework22; and two defined their own framework. Because the Donabedian framework was the most common in these articles and is broadly applicable (not service-specific), we use it to organize and report on quality constructs from all articles in this review.

Most articles used quality-related measures relating to structure (n = 29) and/or process (n = 24), although far fewer (n = 11) included measures related to outcomes (Table 1). (Although SPA surveys do not capture outcomes as defined by the Donabedian framework, i.e., changes in health status, they include data on patient experience, which is how outcomes are characterized in this analysis.) Only nine articles included variables that captured all three constructs; the rest mentioned only one (n = 12) or two (n = 13).

Table 1.

Use of domains and variables within each of the main constructs of care quality (structure, process, and outcomes) among articles included in this systematic review

| Domain | Variable | Number of studies including this variable (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Structure (n = 30) | ||

| Infrastructure | Water | 16 |

| Ambulance/transport/referral | 14 | |

| Telephone/communication | 13 | |

| Electricity/light | 13 | |

| Infection control/waste or sharps disposal | 13 | |

| Soap/gloves | 11 | |

| Toilet/latrine | 9 | |

| Privacy | 7 | |

| Waiting area/room | 6 | |

| Cleanliness | 5 | |

| Adequate storage | 1 | |

| Other* | 4 | |

| Staffing | Recently trained staff | 15 |

| Availability of trained personnel | 10 | |

| Number of personnel | 5 | |

| Years of experience | 2 | |

| Other† | 6 | |

| Service availability | Service-specific availability | 14 |

| Times/days services are available | 11 | |

| Supplies, equipment, medicines | Item availability (medicines and supplies) | 23 |

| Inventory or stock ledger maintained | 5 | |

| Product organization: by expiration date | 4 | |

| Product storage: protected | 4 | |

| Other‡ | 3 | |

| Monitoring | Recent supervisory supervision visit | 10 |

| Management meetings held/system for reviewing management issues | 10 | |

| QA/monitoring system in place | 9 | |

| Client feedback system in place | 8 | |

| Use HMIS/other database | 7 | |

| Client cards used | 2 | |

| Protocols, guides | Guidelines/protocols available/visible | 12 |

| Visual/teaching aids available/used | 6 | |

| Process (n = 24) | ||

| Specific clinical or care procedures implemented | 24 | |

| Use of recordkeeping | 5 | |

| Service duration (minutes) | 4 | |

| Use of gloves, or handwashing | 4 | |

| Ensured privacy or assured confidentiality | 3 | |

| Wait time duration (minutes) | 2 | |

| Outcomes (n = 11) | ||

| Client-reported problems | n = 8 | |

| Client-reported satisfaction with care | 5 | |

| Client-reported intention to return | 2 | |

| Client-reported intention to recommend to friends/family | 1 | |

| Other§ | n = 3 | |

Examples of “other” infrastructure: specific person/system for infrastructure repair/maintenance, functioning incinerator, and number of beds.

Examples of “other” staffing: providers have opportunity for promotion, providers have written job description, providers have received incentives (monetary or nonmonetary), and providers know opportunities for promotion.

Examples of “other” supplies and equipment: proper final sterilization process used for medical equipment, medication stocking frequency, and staff knowledge of processing time for equipment.

Examples of “other” outcomes: correct use of treatment and client knowledge after care.

Structure.

Among the 30 articles that considered structure as a quality construct, the most common domains were supplies/medicines, staffing, infrastructure, and availability of services (Table 1). Articles commonly used the WHO Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) methodology for reporting structure elements23; the “readiness” component of SARA measures include information about inputs required for general readiness and for providing specific types of services (availability of clinical guidelines, diagnostic tools, medicines, and trained health workers). Across all articles, 30 structure variables were mentioned. At most, articles discussed 24 structure variables; the average number was eight and the median was 6. Articles about antenatal care and primary health care incorporated (on average and median) slightly more structure variables than articles on other types of services, but there was vast heterogeneity in all service types (Supplemental Appendix 4).

Certain aspects of infrastructure were mentioned much more commonly than others. More than two-thirds of studies reporting on infrastructure discussed availability of water, infection control/safe disposal measures, and an ambulance, whereas fewer than 40% discussed cleanliness, privacy for clients, or availability of a client waiting area.

Within supplies/medicines, the presence of specific items was the most common representation (availability of equipment and/or consumables [medicines, vaccines] was mentioned by 23 articles), but only four articles mentioned whether the products were well-stored (organized by expiration date) and four mentioned whether storage was protective from the elements or damage. Within the same service type, articles analyzed availability of very different supplies and medicines (Supplemental Appendix Table 4); for example, only two articles on child health care included data about medicine availability: one assessed availability of antibiotics and the other included medicines ranging from antibiotics to oral rehydration salts to deworming tablets. Among articles about quality of antenatal care (n = 10), all but three included availability of iron and/or folic acid tablets, but only four included antimalarial medications.

Training of staff was much more commonly mentioned than availability of staff (e.g., round-the-clock clinician availability) or number of personnel overall. Most articles that discussed monitoring mentioned supportive supervision visits (n = 10) and systems for reviewing management issues (including management meetings) (n = 10), but fewer mentioned approaches for eliciting client feedback (n = 9) or use of Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) or other data systems (n = 7).

PROCESS

There were 24 articles that included process in their operationalization of care quality (Table 1). All used variables that captured clinical care components; these were specific to the type of visit (family planning consultation, antenatal care, childbirth, or sick child care). Different articles, even about the same type of health service, reported on process to a very different extent and using different indicators. In each category of care type, between 20% and 33% of included articles mentioned two or fewer care activities (see Supplemental Appendix Tables 5–8 for details on all activities included, by service type and per article).

Antenatal care.

There were 10 articles that used SPA data to investigate quality of antenatal care services, and nine of them included variables on specific care activities. Across the included articles, 26 different care activities were identified. The most commonly reported activities were testing for anemia (n = 8), testing for urine protein (n = 8), testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (n = 6), measuring blood pressure (n = 7), and measuring weight (n = 6). Only two articles included all five of these common activities. Many components of the WHO essential practice guidelines for antenatal care24—including discussing pregnancy history, asking about danger signs, examining for signs of anemia, and counseling on family planning—were reported by three or fewer articles.

Childbirth.

Among the 12 articles that analyzed quality of childbirth care using SPA data, 11 included information about specific care activities; these 11 articles identified a total of 24 unique childbirth care activities. Encouraging immediate breastfeeding (n = 7), conducting uterine massage after delivery of the placenta (n = 6), ensuring skin-to-skin contact after birth (n = 6), and giving oxytocin within 1 minute of delivery (n = 6) were the most frequently assessed activities, but only two articles included all four of these commonly reported activities. Again, many of the WHO essential practices for childbirth24 were largely omitted, such as giving the baby vitamin K (n = 2), providing antibiotic eye drops or ointment (n = 2), and conducting a vaginal examination (n = 3).

Pediatrics.

There were six articles about sick child care, and five of these included information about specific care processes. In total, these five articles identified 24 specific care activities. The most frequently reported activities were taking child’s temperature (n = 3) and asking about the child’s vaccination history (n = 3). Few articles included the WHO’s Integrated Management of Childhood Illness–recommended counseling activities, such as counseling on feeding habits and illness symptoms (n = 2), or informing the caretaker of the child’s diagnosis (n = 2). Most activities were only included once across the five studies (felt for fever, checked for dehydration, and asked about child’s vitamin A status), and only one article reported most of these activities (n = 20).

Family planning.

The nine articles about family planning care quality included eight that analyzed process, and these eight articles identified a total of 25 specific family planning care activities. The most commonly reported activities were taking client’s reproductive history, blood pressure, and weight (n = 5); asking about chronic illnesses, smoking habits, and STI symptoms (n = 5); counseling on the proper use of family planning methods (n = 4); and ensuring client privacy (n = 4). Only two articles included activities assessing providers’ adherence to clinical procedures (for injectable contraceptives or implants). Other recommended counseling practices from the Global Handbook for Family Planning Providers, such as counseling on side effects and/or when to return (n = 3), partner’s attitude toward family planning (n = 2), and method of protection against STIs/HIV (n = 2), were largely omitted.

In addition, three articles touched on issues related to privacy during the visit. Four articles included a variable related to service interaction duration, and three looked at wait time. Four looked at hygiene during the visit (providers’ handwashing and/or wearing gloves), and five included a measure of whether the provider referenced the client card or a facility register.

Outcomes.

Only 11 articles included such outcomes when measuring care quality (Table 1). The most common experiential outcome was whether the client reported specific problems relating to services that day (n = 8) and whether the client stated they were satisfied with care received (n = 5). A smaller number of articles included whether the client said they intended to return for services and whether they would recommend the care to family or friends. Other outcome measures included the patient’s knowledge after the visit and whether correct treatment was administered.

Summarizing data elements.

There was also substantial variation in methods used to create summary quality measures (Supplemental Appendix 9). One-fifth of the articles (n = 7, 20%) used principal component analysis (PCA) for quantifying quality; among these, some included only structure constructs in the PCA (n = 3), some included structure and process measures (n = 2), and some used client-reported outcomes only (n = 2). Four articles calculated means within domains and used the average of these means as an overall summary measure of quality. All other articles used simple additive indices of constructs (using binary or categorical variables).

DISCUSSION

Publicly and freely available, SPA program data enable examination of healthcare quality in low- and middle-income countries, and, through the use of standardized questionnaires, cross-country analyses, and comparisons. Accordingly, publications based on analyses of SPA data are increasing dramatically, and nearly half of these articles incorporate more than one SPA dataset.

The results of this review indicate opportunities for strengthening the use of SPA data for measuring care quality. Many articles do not use a theoretical framework, despite a rich literature on theories of quality and numerous service-specific frameworks developed by agencies such as the WHO. The use of a theoretical framework is advisable from the perspective of research rigor, reproducibility, and generalizability and also because purely empirical approaches for operationalizing care quality (e.g., PCA if it is not informed by an underlying theoretical framework) result in scores that are highly sensitive to the exact method deployed19 or the health system context,25 which limit generalizability of the results.

We found that certain SPA modules are relatively rarely used—particularly service observation and client exit interviews—and as a result, certain quality constructs (especially patient reports of the care experience, which were characterized here as “outcomes”) are often omitted from characterizations of care quality. It should be noted that patient satisfaction can be challenging to measure with high validity and reliability,26–28 and reported experience may also depend on patients’ overall expectation of the health system and care quality.29–31 Future quality of care studies, including SPA surveys, should explore ways to improve measurement of client-reported experience.

The vast heterogeneity in operationalization limits the development of a larger literature on care quality because these studies differ in their underlying approach to defining and measuring quality. A multidimensional approach to measuring healthcare quality may be necessary because of the complexity and multifaceted nature of the interaction32—for example, studies have found a low correlation between “quality” when measured as inputs (infrastructure) versus service delivery,33 as well as a weak association between service quality and patients’ satisfaction with care.34

These results add to a growing literature about opportunities to expand our learning from public goods datasets such as SPA. Recent reviews have identified gaps between global standards of care quality and studies using publicly available data (including SPA).17,18,35 Although disagreement and debate about how to define quality are not new nor unique to SPA data, the use of a common dataset with standardized tools offers a unique opportunity to align definitions and methods. In Table 2, we suggest ways in which care quality can more comprehensively be measured using available SPA data elements, based on gaps identified in this study. First, structural aspects of care quality should include infrastructure relevant to the patient experience.36,37 Second, many analyses use the SARA methodology for capturing structure and process; we recommend the development of a new harmonized “SARA+” approach to represent quality of the components themselves. For example, SARA measures whether essential medicines are available, but a SARA+ metric would include whether these medicines are stored appropriately; SARA includes recent training of personnel, and SARA+ would capture the average availability of these personnel. Third, quality measures using SPA data should strive to include outcomes—whether patient-reported or objectively measured.38 Service Provision Assessment surveys are a unique source of information from service observations and exit interviews and, therefore, include rare information about outcomes related to patient experience, which would enhance our understanding of care quality. We also recommend that future SPA surveys expand the exit interview module to collect more nuanced and rich data about the care experience and add more service types to the direct observation modules, beyond the maternal and child healthcare services currently included. There are challenges in designing approaches to measuring and reporting care quality, even with standardized datasets, particularly across countries—certain constructs may only be relevant in certain settings because of disease endemicity, for example. Future efforts to standardize quality measurement using SPA data should consider how to account for such geographic heterogeneity and recommend ways in which multicountry analyses might overcome this challenge.

Table 2.

Suggestions for strengthening and harmonizing measurement of care quality using Service Provision Assessment data

|

|

|

Some limitations to these findings should be noted. First, the search was only conducted in PubMed, so we may have missed articles indexed in other databases. Second, the SPA program is only one source of standardized health service quality data; SPA data were selected for this study because of their comprehensiveness and the inclusion of multiple data sources and perspectives (facility, provider, and patient), but other datasets, including from the WHO and the World Bank, should also be included for a more comprehensive understanding of the state of quality measurement in low- and middle-income countries. Third, the classification of variables into quality constructs was based on our assessment (not necessarily how the authors categorized these), which was a subjective process. We chose to use the WHO service guidelines for classifying process measures, but other frameworks might also be informative.39,40 Fourth, true “outcomes” are also not included in SPA surveys, so this analysis could only include outcomes insofar as they related to patient-reported experience. SPA surveys would be even more informative and powerful if they included information on true “outcomes” such as morbidity and mortality (whether through the SPA data collection process or through linkages with health information systems). Last, this review did not assess quality of the included studies nor compare results of these quality assessments.

CONCLUSION

Consistency in quality measurement is critical for cross-country analyses and comparisons. Future studies should seek to refine and harmonize these measures and to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of methods to summarize across structure, process, and outcome domains, including comparing different empirical approaches for summarizing quality of care measures. There may also be important distinctions across service types (e.g., sick child care, antenatal care, childbirth, or family planning services), and this area also merits further study. Service Provision Assessment surveys are an essential tool for researchers and policy-makers, and the public health community should strive to maximize the impact and global learnings from studies that use these data by developing consensus around definitions, frameworks, and operationalizations of key variables.

Supplemental appendices and tables

Acknowledgment:

We thank Bethany Myers of the UCLA Biomedical Library for her expert guidance on refining the search strategy and conducting the search.

Note: Supplemental appendices and tables appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, The World Bank , 2018. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA, 2018. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 392: 2203–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hum RJ, Verguet S, Cheng Y-L, McGahan AM, Jha P, 2015. Are global and regional improvements in life expectancy and in child, adult and senior survival slowing? PLoS One 10: e0124479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atun R, Jaffar S, Nishtar S, Knaul FM, Barreto ML, Nyirenda M, Banatvala N, Piot P, 2013. Improving responsiveness of health systems to non-communicable diseases. Lancet 381: 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine , 2018. Crossing the Global Quality Chasm: Improving Health Care Worldwide. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerma T, Eozenou P, Evans D, Evans T, Kieny M-P, Wagstaff A, 2014. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels. PLoS Med 11: e1001731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donabedian A, 1988. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 260: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce J, 1990. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Stud Fam Plann 21: 61–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization , 2015. WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker A, 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: a New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 1192. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tunçalp Ӧ, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, Daelmans B, Mathai M, Say L, Kristensen F, 2015. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns–the WHO vision. BJOG 122: 1045–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aneshensel CS, 2012. Theory-based Data Analysis for the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGlynn EA, 1997. Six challenges in measuring the quality of health care. Health Aff 16: 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King G, Keohane RO, Verba S, 1994. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demographic and Health Surveys Program , 2019. SPA Overview. Available at: http://www.dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm. Accessed May 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alva S, Kleinau E, Pomeroy A, Rowan K, 2009. Measuring the Impact of Health Systems Strengthening: a Review of the Literature. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheffel A, Karp C, Creanga AA, 2018. Use of Service Provision Assessments and Service Availability and readiness assessments for monitoring quality of maternal and newborn health services in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 3: e001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brizuela V, Leslie HH, Sharma J, Langer A, Tunçalp Ö, 2019. Measuring quality of care for all women and newborns: how do we know if we are doing it right? A review of facility assessment tools. Lancet Glob Health 7: E624–E632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallick L, Temsah G, Wang W, 2019. Comparing summary measures of quality of care for family planning in Haiti, Malawi, and Tanzania. PLoS One 14: e0217547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickerson JW, Adams O, Attaran A, Hatcher-Roberts J, Tugwell P, 2014. Monitoring the ability to deliver care in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of health facility assessment tools. Health Policy Plan 30: 675–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veillard J, Cowling K, Bitton A, Ratcliffe H, Kimball M, Barkley S, Mercereau L, Wong E, Taylor C, Hirschhorn LR, 2017. Better measurement for performance improvement in low‐and middle‐income countries: the primary health care performance initiative (PHCPI) experience of conceptual framework development and indicator selection. Milbank Q 95: 836–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization , 2007. Everybody’s Business-Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Statistics and Information Systems , 2015. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): Reference manual v2.2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO, Health WHOR, Health WHODoR, UNICEF, Activities UNFfP , 2003. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum, and Newborn Care: a Guide for Essential Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson EF, Siddiqui A, Gutierrez H, Kanté AM, Austin J, Phillips JF, 2015. Estimation of indices of health service readiness with a principal component analysis of the Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey. BMC Health Serv Res 15: 536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunsch F, Evans DK, Macis M, Wang Q, 2018. Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality. BMJ Glob Health 3: e000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voutilainen A, Pitkäaho T, Kvist T, Vehviläinen‐Julkunen K, 2016. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs 72: 946–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM, 1995. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care 33: 392–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roder-DeWan S, Gage AD, Hirschhorn LR, Twum-Danso NAY, Liljestrand J, Asante-Shongwe K, Rodríguez V, Yahya T, Kruk ME, 2019. Expectations of healthcare quality: a cross-sectional study of internet users in 12 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med 16: e1002879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bleich SN, Özaltin E, Murray CJ, 2009. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ 87: 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowling A, Rowe G, McKee M, 2013. Patients’ experiences of their healthcare in relation to their expectations and satisfaction: a population survey. J R Soc Med 106: 143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanefeld J, Powell-Jackson T, Balabanova D, 2017. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull World Health Organ 95: 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leslie HH, Sun Z, Kruk ME, 2017. Association between infrastructure and observed quality of care in 4 healthcare services: a cross-sectional study of 4,300 facilities in 8 countries. PLoS Med 14: e1002464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond-Smith N, Sudhinaraset M, Montagu D, 2016. Clinical and perceived quality of care for maternal, neonatal and antenatal care in Kenya and Namibia: the service provision assessment. Reprod Health 13: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moxon SG, Guenther T, Gabrysch S, Enweronu-Laryea C, Ram PK, Niermeyer S, Kerber K, Tann CJ, Russell N, Kak L, 2018. Service readiness for inpatient care of small and sick newborns: what do we need and what can we measure now? J Glob Health 8: 010702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coulter A, 2017. Measuring what matters to patients. BMJ 356: j816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammed K, Nolan MB, Rajjo T, Shah ND, Prokop LJ, Varkey P, Murad MH, 2016. Creating a patient-centered health care delivery system: a systematic review of health care quality from the patient perspective. Am J Med Qual 31: 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browne K, Roseman D, Shaller D, Edgman-Levitan S, 2010. Measuring patient experience as a strategy for improving primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 29: 921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripathi V, Stanton C, Strobino D, Bartlett L, 2015. Development and validation of an index to measure the quality of facility-based labor and delivery care processes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 10: e0129491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spector JM, Lashoher A, Agrawal P, Lemer C, Dziekan G, Bahl R, Mathai M, Merialdi M, Berry W, Gawande AA, 2013. Designing the WHO safe childbirth checklist program to improve quality of care at childbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet 122: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.