Abstract.

COVID-19 is a pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, primarily affecting the respiratory tract. Pulmonary complications of COVID-19 may include acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary embolism. Pneumothorax has been recently reported in association with COVID-19. We report a case of COVID-19 pneumonia with bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax with no known underlying lung disease or risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviridae is a family of RNA viruses that has captured the attention of epidemiologists, microbiologists, clinicians, and policymakers worldwide. SARS-CoV-2 has caused a massive impact on the global economy and everyday life, and an unprecedented burden on the healthcare system. This infection has a broad spectrum of presentations that can range from asymptomatic disease to fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome. Although most cases are mild, up to 5% of the cases can develop severe illness leading to multi-organ damage.1

Spontaneous pneumothorax is a rare complication of COVID-19. Most of the reported cases of pneumothorax associated with COVID-19 lack traditional risk factors or underlying predisposing lung disease.2–16 To date, one case of COVID-19–associated spontaneous bilateral pneumothorax in COVID-19 has been described to the best of our knowledge.12

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old man, not known to have any chronic medical condition, presented with a fever and dry cough for 7 days. He was a nonsmoker, with a height of 161 cm, weight of 61 kg, and a body mass index of 23.5. He had no known exposure to animals, birds, sick contacts, or toxic fumes. Initial physical examination, including chest examination, was unremarkable. Chest X-ray showed prominent broncho-vascular markings bilaterally without evidence of consolidation. COVID-19 PCR from nasopharyngeal swab was positive. The patient was labeled as mild COVID-19 pneumonia and was observed in a quarantine facility.

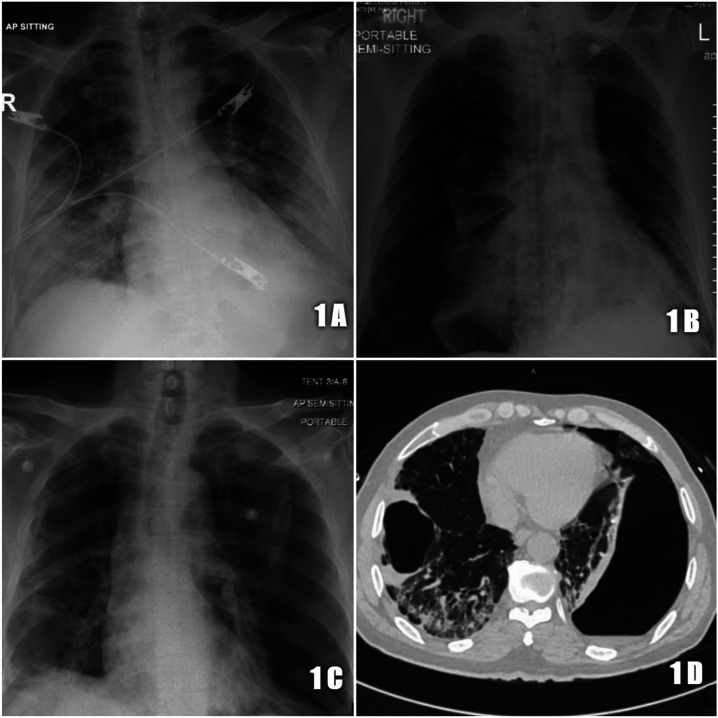

Five days from his initial presentation, the patient developed breathing difficulty with desaturation to 85% on room air. Chest examination revealed bilateral crackles. A chest X-ray showed bilateral lung infiltrates (Figure 1A). His laboratory results showed deranged liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase 197 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 132 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase 81 U/L), lymphopenia (0.8 × 103/µL), high D-dimers (1.47 mg/L), and raised inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 133.1 mg/L and ferritin 8,382.0 µg/L). The patient required 15 L of oxygen via a non-rebreather face mask and was cared for in the intensive care unit as a case of severe COVID-19 pneumonia. He received COVID-19 pneumonia treatment with azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, ceftriaxone, and lopinavir–ritonavir based on local management guidelines. During his intensive care unit stay, the patient was kept in an awake prone position and received tocilizumab and convalescent plasma. At no point during his stay he required the use of continuous positive airway pressure or bi-level positive airway pressure. His oxygen requirements decreased over the next 5 days, and he was transferred to the medical ward.

Figure 1.

(A) Chest X-ray depicting bilateral lung infiltrates, (B) chest X-ray depicting right pneumothorax with right lung collapse and tracheal deviation to the left, (C) chest X-ray depicting bilateral pneumothorax with left > right and tracheal deviation to the right, and (D) chest CT depicting bilateral bullae, ground-glass appearance, and large left pneumothorax with underlying collapsed lung.

On day 12 of the initial presentation, he developed sudden shortness of breath and chest pain, with desaturation. Examination showed decreased air entry on the right lung with a left-deviated trachea. Urgent chest X-ray showed a significant right-sided pneumothorax (Figure 1B). A right-sided chest tube was inserted and connected to an underwater seal, and his symptoms improved. Post-procedure chest X-ray showed a significant reduction in the right pneumothorax with adequate right lung expansion.

On day 17, the patient developed severe acute shortness of breath. Examination showed decreased air entry in the bilateral lung with deviation of the trachea to the right. Urgent chest X-ray showed a significant left-sided pneumothorax, and another chest tube was inserted on the left side (Figure 1C). High-resolution computed tomography (CT) chest showed multiple bilateral bullae in the lungs complicated by the pneumothorax because of rupture (Figure 1D). The alpha-1 antitrypsin level was normal (187.9 mg/dL), and tuberculosis workup, including sputum culture and acid-fast bacilli smear, was negative. The right-sided chest tube was removed after 6 days of insertion and near-complete resolution of the pneumothorax on the ipsilateral side on chest X-ray. The patient continues to receive hospital care at present with near-complete expansion of the left lung.

DISCUSSION

An outbreak of pneumonia with an indeterminate source surfaced in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, later known as COVID-19. COVID-19 has a lower mortality rate in comparison to the other Coronaviridae, such as SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, yet higher infectivity.17

Known risk factors for the development of primary spontaneous pneumothorax include male gender, tall stature, thin body habitus, and age-group 10–30 years.18 Secondary causes include infections, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and trauma.19 Severe alveolar and airway inflammatory damage from the release of cytokines in COVID-19 can lead to weakening of the bronchial walls. Edema, vascular congestion, and microthrombi may contribute to the rupture of preexisting bullae.20 Rupture of these bullae can lead to pneumothorax.

Bullous lung disease is characterized by the development of bullae in otherwise normal lung parenchyma.21 Risk factors for the development of bullae include smoking history, pulmonary sarcoidosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, alpha-1 anti-chymotrypsin deficiency, Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, inhaled fiberglass exposure, and marijuana smoking.20,22 The underlying pathophysiology for bullae formation involves inflammatory damage to the bronchiole, leading to trapping of air. Interaction of mechanical forces on the weakened tissue may lead to bullae formation.21,23

Although our patient was a male, he was never smoker, with unrevealing screening for risk factors of bullae formation and pneumothorax. The bullous changes could represent an undiagnosed underlying pulmonary disease, which became apparent after the inflammatory changes and excessive mechanical forces introduced by the SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading to a unilateral spontaneous pneumothorax, followed by bilateral pneumothorax.

Review of the literature shows 18 case reports describing COVID-19 patients with spontaneous pneumothorax. Eight of these patients were managed conservatively, whereas 10 required chest tube insertion. Two of the patients required thoracoscopy and bleb resection. One patient developed tension pneumothorax and required emergency needle decompression. Only four cases were smokers. Three cases were on invasive mechanical ventilation. Three had underlying lung disease. One case had bilateral pneumothorax, whereas the rest had unilateral involvement. Twelve patients had a favorable clinical course, whereas six patients passed away, resulting in a mortality rate of 33% based on the available literature (Table 1).2–16 Our case is the second reported bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax in the literature to the best of our knowledge.

Table 1.

Literature review of COVID-19–associated pneumothorax

| Serial number | Author/published year/country | Number of cases | Age (years) | Gender | Comorbidities | Diagnosis | Treatment/intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Lyu R, et al., April 2020, Wuhan, China | 1 | 38 | Male | Smoker | Left pneumothorax | Conservative | Recovered and discharged |

| 2. | Rohailla S, et al., May 2020, Toronto, Canada | 1 | 26 | Male | Nil | Right pneumothorax | Chest tube | Recovered and discharged |

| 3. | Agridag B, et al., May 2020, Istanbul, Turkey | 1 | 82 | Female | Nil | Left pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema | Chest tube | Recovered and discharged |

| 4. | Aydın S, et al., May 2020, Afyonkarahisar, Turkey | 1 | 24 | Male | Nil | Left pneumothorax | Chest tube | Recovered and discharged |

| 5. | Wang W, et al., May 2020, Wuhan, China | 1 | 62 | Male | Nil | Right pneumothorax | Conservative | Recovered and discharged |

| 6. | Poggiali E, et al., June 2020, Piacenza, Italy | 1 | 87 | Male | Smoker + chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Left pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema | Chest tube | Recurrence and expired |

| 7. | Flower L, et al., May 2020, London, United Kingdom | 1 | 36 | Male | Smoker + asthma | Left pneumothorax | Needle decompression + chest tube | Recovered and discharged |

| 8. | Sun R, et al., March 2020, Wuhan, China | 1 | 38 | Male | Nil | Left pneumothorax | Conservative | Recovered |

| 9. | Wang J, et al., March 2020, Guangzhou, China | 1 | 36 | Male | Nil | Pneumomediastinum | Conservative | Expired |

| 10. | Lei P, et al., April 2020, Guiyang, China | 1 | 64 | Male | Nil | Pneumomediastinum | Conservative | Recovered |

| 11. | López V, et al., June 2020, Madrid, Spain | 3 | 84 | Female | Hypertension, prosthetic heart valve, chronic kidney disease, and congestive cardiac failure | Right hydro-pneumothorax | Conservative | Expired |

| 67 | Male | Nil | Bilateral pneumothorax + pneumomediastinum | Chest tube | Expired | |||

| 73 | Male | Epithelioma, obstructive sleep apnea | Pneumomediastinum | Conservative | Expired | |||

| 12. | Aiolfi A, et al., April 2020, Milan, Italy | 2 | 56 | Male | Smoker | Left pneumothorax | Chest tube thoracoscopy: bleb resection + pleurodesis | Recovered |

| 70 | Male | Nil | Left pneumothorax | Chest tube thoracoscopy: bleb resection + pleural scratch | Recovered | |||

| 13. | Kolani S, et al., May 2020, Fez, Morocco | 1 | 23 | Female | Nil | Pneumomediastinum | Conservative | Recovered |

| 14. | Mohan V, et al., May 2020, New Jersey | 1 | 49 | Male | Hypertension and diabetes mellitus | Pneumomediastinum | Conservative | Recovered |

| 15. | Xiang C, et al., May 2020, Wuhan, China | 1 | 67 | Male | CAD/COPD | Pneumothorax + subcutaneous emphysema | Chest tube | Expired |

CAD = coronary artery disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

CONCLUSION

Acute deterioration in COVID-19 patients may be due to primary disease or pulmonary embolism; however, pneumothorax is another important differential. Pneumothorax is infrequently associated with COVID-19 pneumonia. COVID-19–related spontaneous pneumothorax in an otherwise healthy individual may be an underdiagnosed entity. This association could be secondary to underlying undiagnosed bullous lung disease and rupture. However, further research is needed in this area.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Kamran Mushtaq, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department, for his guidance. Publication charges for this article were waived due to the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan J, 2020. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. JAMA 323: 1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyu R, Li X, 2020. Diagnosis and treatment of severe COVID-19 complicated with spontaneous pneumothorax: a case report. Adv Ultrasound Diagn Ther 4: 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohailla S, Ahmed N, Gough K, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with spontaneous pneumothorax. CMAJ 192: E510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ucpinar BA, Sahin C, Yanc U, 2020. Spontaneous pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema in COVID-19 patient: case report. J Infect Public Health 13: 887–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aydın S, Öz G, Dumanlı A, Balcı A, Gencer A, 2020. A case of spontaneous pneumothorax in COVID-19 pneumonia. J Surg Res 3: 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Gao R, Zheng Y, Jiang L, 2020. COVID-19 with spontaneous pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. J Travel Med, 10.1093/jtm/taaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poggiali E, et al. 2017. COVID-19, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumothorax: a frightening triad. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flower L, Carter JPL, Lopez JR, Henry AM, 2020. Tension pneumothorax in a patient with COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 13: e235861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun R, Liu H, Wang X, 2020. Mediastinal emphysema, giant bulla, and pneumothorax developed during the course of COVID-19 pneumonia. Korean J Radiol 21: 541–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Su X, Zhang T, Zheng C, 2020. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a probable unusual complication of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Korean J Radiol 21: 627–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei P, Mao J, Wang P, 2020. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia and the possible underlying mechanism. Korean J Radiol 21: 929–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vega JML, Gordo MLP, Tascón AD, Vélez SO, 2020. Pneumomediastinum and spontaneous pneumothorax as an extrapulmonary complication of COVID-19 disease. Emerg Radiol, 10.1007/s10140-020-01806-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiolfi A, Biraghi T, Montisci A, Bonitta G, Micheletto G, Donatelli F, Cirri S, Bona D, 2020. Management of persistent pneumothorax with thoracoscopy and blebs resection in COVID-19 patients. Ann Thorac Surg, 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolani S, Nawfal H, Haloua M, Lamrani YA, Boubbou M, Serraj M, Aamara B, Maaroufi M, Alami B, 2020. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum occurring in the SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases 21: e00806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohan V, Tauseen RA, 2020. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 13: e236519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang C, Wu G, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia with subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal emphysema, and pneumothorax: a case report. Medicine 99: e20208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkinson B, Petersen E, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 shedding and infectivity. Lancet 395: 1339–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta D, 2000. Epidemiology of pneumothorax in England. Thorax 55: 666–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahn S, Heffner J, 2000. Spontaneous pneumothorax. New Engl J Med 342: 868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg C, Carey K, 2013. Bullous lung disease. West J Emerg Med 14 450–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grippi M, Elias J, Fishman J, Kotloff R, Pack A, Senior R, n.d. Fishman’s Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, 5th edition. Mcgrawhill, Chapter 52, pp 789–791. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M, 2000. Large lung bullae in marijuana smokers. Thorax 55: 340–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurenzi G, Turino G, Fishman A, 1962. Bullous disease of the lung. Am J Med 32: 361–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]