Abstract.

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) is a rare type of leishmaniasis characterized by diffuse skin lesions. In Brazil, Leishmania (L.) amazonensis is the main etiological agent of this clinical form. The state of Maranhão has the highest prevalence of this disease in the country, as well as a high rate of HIV infection. Here, we report the first case of DCL/HIV of Brazil. A 46-year-old man from the Amazonian area of Maranhão state presented atypical lesion in the left upper limb and dissemination of diffuse erythematous nodules over his entire body. Histopathological examination confirmed the presence of intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania, and a polymerase chain reaction and molecular identification by restriction fragment profile identified L. (L.) amazonensis as the causative agent of the disease. The patient was also diagnosed with HIV virus after the leishmaniasis diagnosis. The initial treatments for leishmaniasis were liposomal amphotericin B (AmB-L) (4 mg/kg) for 10 days and prophylactic use of Glucantime® (10 mg/Sb+5/kg) for 2 months. After unsuccessful initial treatments, he was treated with a combination of AmB-L (4 mg/kg) alternated with pentamidine (4 mg/kg) for 10 days but failed in the first therapeutic cycle. Subsequently, he had a good response to treatment with pentamidine (4 mg/kg).

INTRODUCTION

In Brazil, Leishmania (L.) amazonensis is the main etiological agent of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL), a rare pathology associated with a defective immune response from the host against the parasite.1 Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by hematogenous dissemination of parasites, resulting in a massive dermal impairment with the emergence of diffuse infiltration and lesions with erythematous, nodular and/or tumoral aspect.2 In addition, patients with DCL have Th2 cellular immune response to the parasite and exhibit poor response to treatment and resistance to chemotherapy.3,4

The wide distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in Brazil occurs in a heterogeneous manner, highlighting the Northeast as the second region with the highest rate of new cases.5 The state of Maranhão is endemic to the disease, having a high incidence in the country, with 1,251 cases in 2018.6 The state also has the largest number of DCL cases in the country according to the latest retrospective study.7 Regarding HIV/CL coinfection in Maranhão, the Ministry of Health recorded between 2008 and 2017 a total of 120 cases, with a predominance of association with the localized cutaneous form (93.3%), with no information about the association between HIV/DCL.8

We described the first case of a patient with coinfection between HIV and L. amazonensis in Brazil, presenting atypical manifestations of CL.

CASE REPORT

We report a 46-year-old man, resident in the municipality of Maranhãozinho–Maranhão State, Brazil, who presented, in 2017, a painless, high-edge, ulcerated lesion in the left upper limb (LUL). Histopathological biopsy suggested the diagnosis of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Initially, the patient was referred to a chemotherapy regimen with meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®) (10 mg/Sb+5/kg), presenting a good therapeutic response. However, because of poor adherence to the treatment, there was no complete and satisfactory remission of the clinical signs. The patient returned after the evolution of the initial lesion, observing an enlargement and presence of pruritus. In addition, dissemination of diffuse erythematous nodules was observed on the face, torso, ear lobes, and upper and lower limbs. Moreover, the patient also reported pain in these regions when touched. During this period, the patient maintained only secondary infection treatment.

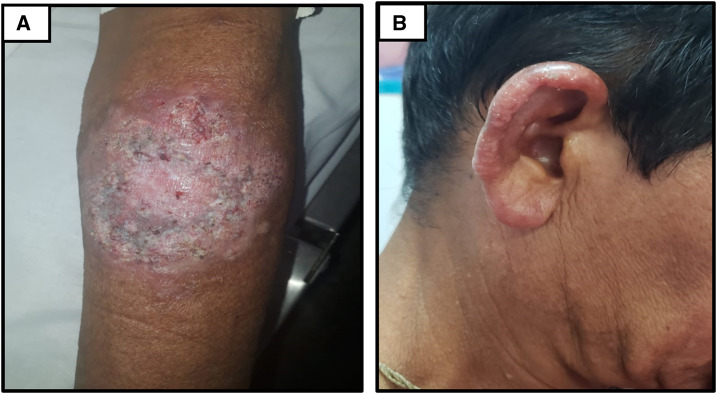

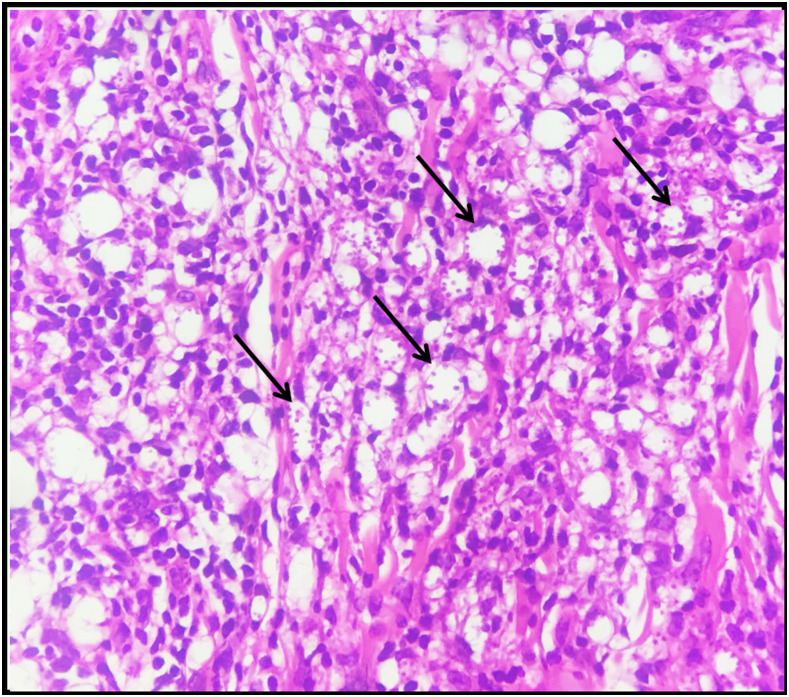

In January 2019, he was diagnosed with HIV with a viral load (VL) of 6,198 copies/mL and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 27 cell/mm.3 After 2 months, the patient was admitted in the Infectious Diseases Reference Service, in a general regular condition. During physical examination, the ulcerated lesion in his LUL showed a verrucous appearance (Figure 1A), in addition to bilateral ear infiltration and disseminated erythematous nodules (Figure 1B). Blood tests showed a leukocyte count of 3,340 mm3, of which 70.7% were neutrophils; in addition, erythrocytes and platelet count were 3,860 mm3 and 157,000 mm3, respectively. Besides, it was performed as a smear examination for leprosy in a dermal smear with negative result. Histopathological examination was consistent for diffuse granulomatous dermatitis, a typical feature of DCL, observing acanthosis, spongiosis, and exocytosis of inflammatory cells in the epidermis. The dermis showed moderate chronic lymphocytic and histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate with the formation of loose granulomas and presence of large multinucleated cells. Inside the histiocytic cells, oval structures suggestive of intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania were also noted (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Patient with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. Ulcerated lesion in the left upper limb with a verrucous appearance (A), and ear infiltration and disseminated erythematous nodules (B). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of skin biopsy showing lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate (×400). Macrophages with intracytoplasmic amastigote forms (arrows). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

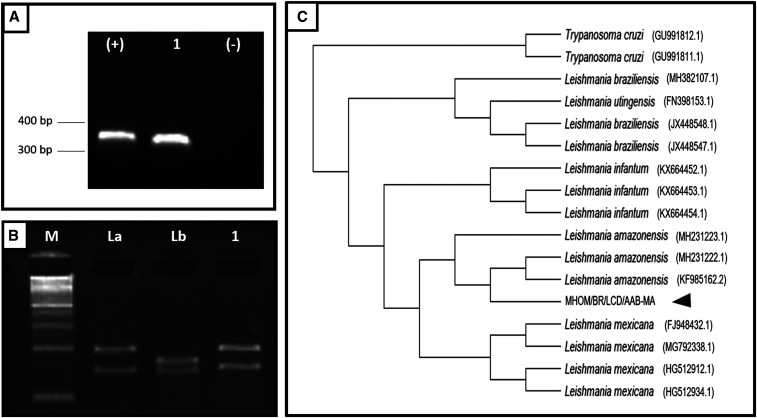

Biopsy fragments were inoculated in Schneider culture medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 20% inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco®, Waltham, MA) kept at 26°C for parasite isolation. After 3 days, the amastigote forms became promastigotes and the clinical isolate was coded as MHOM/BR/LCD/AAB-MA. Polymerase chain reaction was performed using a ribosomal RNA coding region internal transcribed spacer-1 (ITS-1)9. The obtained product was digested using the enzyme HaeIII (Promega™, Madison, WI) and alternatively sequenced on the ABI-Prism 3500 Genetic Analyzer platform (Amplied Biosystem™, Waltham, MA). Molecular identification by restriction fragment profile and bioinformatics analysis using phylogenetic interference10,11 identified L. (L.) amazonensis as the causative agent of the disease (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Molecular identification of the MHOM/BR/LCD/AAB-MA isolate. (A) ITS-1 gene amplification in 1% agarose gel. (B) Digestion of the amplified product with HaeIII and size separation in 4% agarose gel. (C) Phylogenetic tree of ITS-1 gene sequences from Leishmania species. Scale bar indicates 0.1% divergence. M = molecular weight marker (100 bp); (+) = positive control; (−) = negative control; 1 = clinical isolate; La =Leishmania amazonensis (IFLA/BR/1967/PH8); Lb = Leishmania braziliensis (MHOM/BR/1975/M2903).

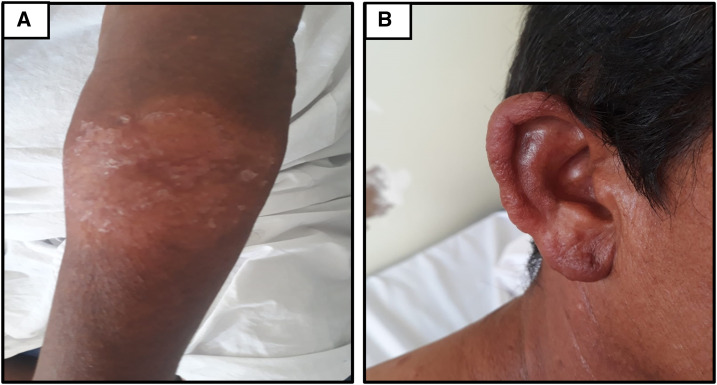

The therapeutic regimen adopted was the combination of antiretroviral, with lamivudine, tenofovir, and dolutegravir, and prophylactic therapy for pneumocystosis and toxoplasmosis, with a combination of sulfamethoxazole (800 mg/day) and trimethoprim (160 mg/day). Still, the patient received therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (AmB-L) (4 mg/kg), and after 10 days of treatment, he obtained a satisfactory therapeutic response, evolving with considerable improvement of the lesions, however, still residual (Figure 4). The patient was discharged and remained on weekly prophylactic use of Glucantime® (10 mg/Sb+5/kg) for 2 months.

Figure 4.

Healing of lesions after 10 days of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B. Residual cicatrization in the left upper limb lesion (A) and the ear (B). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

After these 2 months of discharge, under medical follow-up, the patient presented the first relapse of the disease, being readmitted for treatment for 10 days with AmB-L (4 mg/kg) alternated with pentamidine (4 mg/kg), progressing satisfactorily.

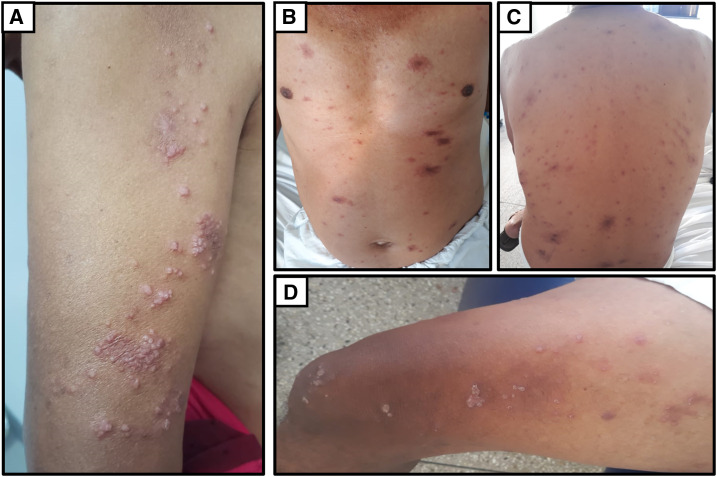

In October 2019, on his most recent return to the reference service, he presented a VL of 70 copies/mL and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte dosage of 85 cells/mm.3 The patient had a relapse with milder but diffuse lesions (Figure 5), requiring further hospitalization. The therapeutic approach adopted was with pentamidine (4 mg/kg), presenting a good response to treatment, without complaints and/or complications, and continuing with medical follow-up.

Figure 5.

The patient showed a relapse with diffuse lesions over his entire body: (A) arms, (B) chest and abdomen, (C) back and (D) thighs. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

However, the patient had a relapse again, and the therapeutic approach adopted was AmB-L (4 mg/kg) + Glucantime® (10 mg/Sb+5/kg) for 20 days. The patient was discharged and remained on weekly prophylactic use of Glucantime® (10 mg/Sb+5/kg) until now.

The patient signed the informed consent form for the publication of the case and also the images.

DISCUSSION

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is considered a rare and severe manifestation of leishmaniasis, characterized by chronic evolution with dermal impairment.11 In Brazil, this disease has a considerably lower incidence than other clinical conditions of CL, but in the state of Maranhão, its occurrence is significant.7,12,13 The state also has a high prevalence of HIV infection, and cases of coinfection in patients with visceral leishmaniasis are more frequent.14 Few cases of Leishmania/HIV coinfection in patients with DCL have been reported worldwide, with cases being found in India,15–18 Senegal,19 and Colombia,20 and there is no evidence of reports published in the literature of such cases in Brazil. Thus, this case report is referenced as the first case of a patient with DCL coinfected with HIV in Northeast Brazil.

Leishmania (L.) amazonensis was identified as the causative agent of the disease, in which the patient was probably infected in the city where he lives and also works. In addition, the city of Maranhãozinho, located in the Maranhão Legal Amazon, is a sporadic transmission area of leishmaniasis.21 According to the Ministry of Health, this etiological agent has distribution in the primary and secondary forests of the state’s Legal Amazon, and the incidence of the Bichromomyia flaviscutellata vector in the state has also been demonstrated.5

Histopathological analysis revealed a typical DCL profile, observing a granulomatous inflammatory response with lymphocytic infiltrate and a large number of vacuolated macrophages infected with amastigote forms, compatible with L. (L.) amazonensis infection.22 Regarding the clinical aspects of the patient, the lesions were heterogeneous, observed mainly in the form of disseminated erythematous nodules in various parts of the body and infiltrative plaques in the ear, similar to the diagnosed clinical form.2,7

The ulcerative nodular lesion in the LUL progressively evolved during clinical observation, ranging from a lesion with high edges to one with verrucous appearance. The onset of atypical lesions in CL patients is attributed in part to a depressed immune response, which is observed in patients with DCL.7,23,24

Patients with HIV who show low CD4 T-cell counts, such as the patient described here, can expect unusual clinical characteristics such as widespread lesions on different parts of the body as well as more severe lesions.25 In addition, HIV coinfection may amplify immune deficiency, exponentially increasing the disease severity, and may lead to refractory therapeutic regimens and also longer time to clinical resolution.26

Patients with DCL are known to be refractory to antileishmanial treatment.4,27 This fact worsens in cases of HIV coinfection, where higher rates of therapeutic failure and relapse are observed despite ongoing antiretroviral treatment.28 The first therapeutic regimen adopted in this patient was with Glucantime®; however, the treatment was interrupted because of poor adherence. The therapeutic response to antimonials in patients with Leishmania/HIV coinfection tends to be poor, with relapse rates of 14–57% of cases.25

After his return and positive diagnosis for HIV, the patient used AmB-L for 10 days, with satisfactory response and clinical remission, but had the first relapse after 2 months. Therefore, it was necessary to change the therapeutic regimen using a combination of AmB-L and pentamidine, to which the patient showed considerable improvement. These drugs are reserved for special clinical cases such as DCL.7 In addition, the use of these drugs has already demonstrated clinical cure and conversion of Montenegro intradermal reaction of 51.5% in a casuistry performed in Ethiopia.29 Despite clinical improvement, the patient relapsed and was given a pentamidine-only regimen, with no complications to date.

In conclusion, in areas of high CL and HIV-endemic conditions, particularly in the Brazilian Amazon region, it is possible to obtain reports of patients infected by both pathogens simultaneously manifesting atypical clinical signs, as occurred in this report. Thus, the health team should be aware of these cases, which require appropriate treatment and continuous clinical follow-up of the patient.

REFERENCES

- 1.Christensen SM, Belew AT, El-Sayed NM, Tafuri WL, Silveira FT, Mosser DM, 2019. Host and parasite responses in human diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. amazonensis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13: e0007152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto H, Lindoso JA, 2010. Current diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti Infec Ther 8: 419–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cáceres-Dittmar G, Tapia FJ, Sánchez MA, Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Modlin RL, Bloom BR, Convit J, 1993. Determination of the cytokine profile in American cutaneous leishmaniasis using the polymerase chain reaction. Clin Exp Immunol 91: 500–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scorza BM, Carvalho EM, Wilson ME, 2017. Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int J Mol Sci 18: 1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde , 2017. Manual de Vigilância da leishmaniose tegumentar. Brasília: ministério da Saúde. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/manual_vigilancia_leishmaniose_tegumentar.pdf. Acessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde , 2019. Casos de leishmaniose tegumentar, Brasil, Grandes Regiões e Unidades Federadas 1990 a 2018. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde. Available at: http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2019/outubro/14/LT-Casos.pdf. Acessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa JML, Uthant AA, Elkhoury AN, Bezerril ACR, Barral A, Saldanha CR, 2009. Diffuse Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (DCL) in Brazil after 60 years of your first description. GMBahia 79: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira RS, Pimentel KBA, Magalhães FJS, Nascimento GC, Santos LLL, Barros LAA, Pinheiro VCS, 2019. Occurence of cutaneous leishmaniasis/HIV co-infection in the State of Maranhão. EJCH 11: e487. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schönian G, Nasereddin A, Dinse N, Schweynoch C, Schalling HD, Presber W, Jaffe CL, 2003. PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 47: 349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP, 2009. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26: 1641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K, 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 35: 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa JML, Saldanha ACR, Silva ACDM, Serra Neto A, Galvão CES, Silva CDMP, Silva ARD, 1992. Estado atual da leishmaniose cutânea difusa (LCD) no Estado do Maranhão: II. Aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos-evolutivos. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 25: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes Costa JM, Gama M, Karinine Cunha A, Saldanha ACR, 1998. Leishmaniose cutânea difusa (LCD) no Brasil: revisão. An Bras Dermatol 73: 565–576. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho FL, Aires DLS, Segunda ZF, Azevedo CMPS, Corrêa RGCF, Aquino DMC, Caldas AJM, 2013. The epidemiological profile of HIV-positive individuals and HIV-leishmaniasis co-infection in a referral center in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 18: 1305–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooja S, Sharma B, Jindal A, Vyas N, 2014. First reported cases of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus positive patients in Jaipur District of Rajasthan, India. Trop Parasitol 4: 50‒52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khandelwal K, Bumb RA, Mehta RD, Kaushal H, Lezama-Davila C, Salotra P, Satoskar AR, 2011. A patient presenting with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) as a first indicator of HIV infection in India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85: 64–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhary RG, Bilimoria FE, Katare SK, 2008. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis: co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Indian J Dermatol Leprol 74: 641–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purohit HM, Shah AN, Amin BK, Shevkani MR, 2012. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis–a rare cutaneous presentation in na HIV-positive patient. Indian J Sex Transm Dis 33: 62–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ndiaye PB, Develoux M, Dieng MT, Huerre M, 1996. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a Senegalese patient. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 89: 282–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez C, Yoanet S, Rodríguez G, 2006. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in a patient with AIDS. Biomedica 26: 485–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde , 2018. Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana, Casos confirmados notificados no Sistema de Informação e Agravos de Notificação, Maranhão. Brasília:Ministério da Saúde. Available at: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?sinannet/cnv/ltama.def. Acessed November 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbieri CL, Brown K, Rabinovitch M, 1985. Depletion of secundary lysosomes in mouse macrophages infected with Leishmania mexicana amazonensis: a cytochemical study. Z Parasitenkd 71: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman SB, 1998. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol 139: 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Beato MJ, Moyano B, Sanchez C, Gonzalez-Beato MT, Perez-Molina JA, Miralles P, Lazaro P, 2000. Kaposi’s sarcoma- like lesions and other nodules as cutaneous involvement in AIDS-related visceral leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol 143: 1316–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvar J, Aparicio P, Aseffa A, Den Boer M, Cañavate C, Dedet JP, Gradoni L, Ter Horst R, López-Vélez R, Moreno J, 2008. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev 21: 334–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borges AS, Machado AA, Ferreira MS, de Castro Figueiredo JF, Silva GF, Cimerman S, Bacha HA, Teixeira MC, 1999. Concurrent leishmaniasis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: a study of four cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 32: 713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryceson AD, 1970. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ethiopia. II. Treatment. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 64: 369–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Griensven J, Carrillo E, López-Vélez R, Lynen L, Moreno J, 2014. Leishmaniasis in immunosuppressed individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect 20: 286–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryceson AD, 1970. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ethiopia. IV. Pathogenesis of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 64: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]