On Sept 19, 2011, global leaders met at the UN in New York, USA, to set an international agenda on non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which cause three-quarters of global deaths. This was only the second time in history that the UN General Assembly had met to discuss a health issue (the first was for HIV/AIDS in 2001). In 2015, Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 set the ambitious target for countries to reduce their risk of premature mortality from NCDs by a third relative to 2015 levels by 2030. The Lancet NCD Countdown 2030, published on Sept 3, reveals that, among high-income countries, only Denmark, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, and South Korea are on track to meet this target for both men and women if they maintain or surpass their 2010–16 average rates of decline. We know how to reduce the risk of NCDs—for the most part through a combination of effective tobacco and alcohol control, and well understood health interventions for hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. But addressing the broader determinants of NCDs is difficult without more robust fiscal measures. Although NCDs have received plenty of political attention, action has clearly been inadequate.

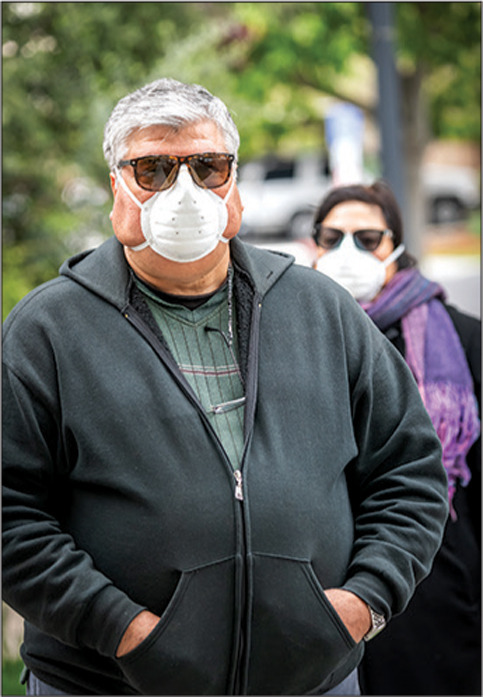

A modelling study published in The Lancet Global Health suggests that, worldwide, one in five people are at an increased risk of severe COVID-19 should they become infected, mostly as a result of underlying NCDs. The enormous efforts to deal with COVID-19 have also disrupted the regular care often required by patients with NCDs. WHO completed a rapid assessment survey in May, 2020, and found that 75% of countries reported interruptions to NCD services. Among the most hard hit were public health campaigns and NCD surveillance efforts. Excess deaths from the disruption caused by COVID-19 might make any gains against the virus a pyrrhic victory. COVID-19 and NCDs form a dangerous relationship, experienced as a syndemic that is exacerbating social and economic inequalities. The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: bridging a gap in universal health care for the poorest billion, will be published later this month and will explore the relation between poverty and NCDs in more detail. COVID-19 also provides a new lens through which to view NCDs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries have seen the value of stronger tobacco and alcohol controls, an important step towards reducing NCDs. But others have struggled to balance public health measures against predatory commerce and economic recovery. Botswana, India, Russia, South Africa, and Spain have all restricted tobacco products during the pandemic. But the tactics of Big Tobacco have been at play: on Aug 17, South Africa lifted its ban after two legal challenges from the tobacco industry.

There have been national responses to safeguard and improve nutrition. Initially, in Costa Rica, the government kept school canteens open amid school closures, but later decided to distribute food baskets containing fresh and perishable food to families. In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson found new energy to tackle obesity after his own experience of COVID-19. But in total opposition to this plan, in August, the UK launched a scheme to encourage people to eat in restaurants and fast-food outlets in order to help businesses. Dubai loosened laws governing alcohol sales to encourage the economy. For many people, lockdowns exacerbated an obesogenic environment in which access to nutritious food and physical activity were made more difficult.

COVID-19 is a pandemic that must highlight the high burden that NCDs place on health resources. It should act as a catalyst for governments to implement stricter tobacco, alcohol, and sugar controls, as well as focused investment in improving physical activity and healthy diets. COVID-19 has shown that many of the tools required for fighting a pandemic are also those required to fight NCDs: disease surveillance, a strong civil society, robust public health, clear communication, and equitable access to resilient universal health-care systems. COVID-19 could provide new insights into interactions between the immune system and NCDs, and potentially change the way we understand and treat these diseases. It might also generate new long-term disabilities that will add to the NCD burden. 2020 has shown the crucial relation between communicable diseases and NCDs. Both inflict an unacceptable toll on human life. COVID-19 must stimulate far greater political action to overcome inertia around NCDs.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on Sept 8, 2020

© 2020 Juanmonino