Highlights

-

•

The Covid-19 pandemic has affected the peer-to-peer accommodation sector.

-

•

We examine host perceptions of and responses to the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

•

We identify five host types according to their response to the pandemic.

-

•

We offer a continuum of different categories of host pandemic responses.

-

•

The continuum may be of theoretical and practical value to stakeholders.

Keywords: P2P accommodation, Covid-19, Crisis, Hosts, Perceptions, Responses

Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought international tourism at a standstill. Peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation, in particular, has been greatly affected with platforms being heavily criticised for lacking a strategic response to users’ needs. Drawing from semi-structured interviews with P2P accommodation hosts, this study aims to explore: a) their perceptions of the short-term impacts of the pandemic on their hosting practice, b) their responses to the pandemic and c) their perceptions of the long-term impacts of the pandemic on the P2P accommodation sector. The study offers a continuum of host pandemic responses which illustrates different types of hosts in relation to their market perspective and intention to continue hosting on P2P platforms. The continuum carries theoretical implications as it offers insights to academics exploring crisis impacts on P2P accommodation. It is also of practical value to platforms and practitioners as it may lead to improved crisis management strategies.

1. Introduction

The tourism and hospitality industry is no stranger to pandemics, having been impacted by SARS in the early 2000s and MERS more recently (Jamal and Budke, 2020). Nonetheless, the emergence and rapid spread of a new coronavirus (Covid-19) has had unprecedented effects on the global tourism and hospitality market. Initially detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan in early December (Yang et al., 2020), Covid-19 spread rapidly and by May 2020 there were over 3.85 million reported cases of infected people and 270,000 reported deaths worldwide (World Hospitality Organisation, 2020). As a result, governments around the world imposed strict restrictions prohibiting travel while closing their borders, bringing international travel at a standstill. Specifically, airlines have grounded their fleet and suspended operations (Sahin, 2020). Likewise, the international hospitality and leisure industry has been experiencing tremendous economic problems as hotels in most countries were forced to shut down due to governments’ lock-down response to the pandemic. For example, 70 % of hotel employees have been laid off or furloughed, leading to a $2.4 billion loss in weekly wages and 3.9 million hospitality-supported jobs being lost (American Hospitality and Lodging Association, 2020). Unsurprisingly, with a 50 % reduction in revenues (Oxford Economics, 2020), 2020 was named the worst year for hospitality in terms of occupancy rates since the 1933 Great Depression (CBRE, 2020).

Although crises in general have long-lasting adverse effects on travel patterns, tourist demand and destination image (Chew and Jahari, 2014; Chien and Law, 2003; Corbet et al., 2019), the tourism and hospitality industry has proven to be resilient in the past. Indeed, in most cases destinations recover (Seabra et al., 2020) particularly when crisis management strategies are in place (Alonso-Almeida and Bremser, 2013). For instance, after SARS in China, travel bounced back relatively quickly to normal levels (Dombey, 2004). Nonetheless, the unparalleled situation brought about by Covid-19 has led to concerns over the future of global tourism and hospitality industry, which is one of the worst-affect industries by the pandemic (Tidey, 2020). Specifically, scholars estimate that the effects of Covid-19 on tourist risk perceptions and destination marketing will be long-lasting even after the pandemic is controlled (e.g. Ying et al., 2020), especially on the operational aspects of the industry. For instance, hospitality companies have issued announcements that their cleaning protocols will be revised. In this context, a range of practices such as the use of germ-zapping robots, the removal of breakfast buffets, a 24 -h gap between check-out and check-in time and even the issuance of a ‘clean and safe’ certificate has been suggested by hospitality associations and international hotel chains (Bagnera et al., 2020).

The peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation sector has attempted to follow suit, with platforms such as Airbnb and Booking.com responding to the effects of Covid-19 in numerous ways. For example, the platforms have sought to establish a new, optional cleaning protocol for properties which requires a 24 -h waiting time between bookings as well as the use of specific cleaning products to eliminate possible coronavirus transmissions (Wood, 2020). In addition, the platforms have issued a refund policy which, nonetheless, angered a large majority of guests as they discovered that refunds are partial, dependent on the host and/or given in the form of travel credit (Shuk, 2020; Webster, 2020). Concerns from P2P accommodation hosts have also been voiced as many struggled financially during the pandemic due to the loss of reservations (Johnson and Davis, 2020). In relation to this point, hosts on P2P accommodation platforms expressed that they felt largely unsupported as many local governments deemed P2P accommodation as non-essential business (Evans, 2020), granting them no financial support and leaving the companies to foot the bill. Airbnb, for instance, announced its intentions to provide more than $250 million to support its host community. Likewise, Booking.com has asked financial aid from the Dutch government to pay the salaries of its Netherlands based staff (Sharma, 2020). Even so, the platforms have been criticised heavily for demonstrating a lack of strategic thinking in response to Covid-19 (Carpenter, 2020). With Airbnb being forced to lay off 25 % of its staff while observing its value depreciate from $31 billion in March 2020 to $18 billion in May 2020 (Evans, 2020) and Booking.com informing employees that lay-offs are probable (Stevens, 2020), it is not surprising that some media reports are suggesting that the pandemic might signal the end of P2P accommodation.

Drawing from the perspectives of P2P accommodation hosts, this study aims to explore in-depth the perceived impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on host practice specifically and P2P accommodation in general. More precisely, we examine P2P accommodation hosts’ perceptions of the short-term and long-term impacts of the pandemic as well as their associated responses. Overall, the study offers several contributions. First, it advances existing knowledge on the pandemic-tourism nexus which has mostly concentrated on destination-level and sectoral-based analyses (Gössling et al., 2020). While there are past studies examining the impacts of and responses to pandemics in hospitality (e.g. Alan et al., 2006; Henderson and Ng, 2004), these tend to overlook the perspectives of micro-level stakeholders. By drawing from accommodation service providers, this study thus responds to this gap in the literature. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the associated impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the increasingly popular P2P accommodation sector (Farmaki and Kladou, 2020). Given that health, safety and cleanliness are considered key elements in hospitality decision-making (Zemke et al., 2015), findings from this study will therefore shed light on the ongoing discourse on P2P hosts’ practices which have been argued to shift to more institutionalised hospitality services (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020). Third, the increase in infectious diseases across the world (Jamal and Budke, 2020) will likely preoccupy hospitality practitioners in the foreseeable future. To this end, this study contributes insights that may lead to improved health crisis management strategies in hospitality.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. First, the literature on the effects of pandemics on hospitality is reviewed before considering the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the P2P accommodation sector. Then, the methodology guiding this study is explained and justified before the findings are presented and discussed. Last, the theoretical and practical implications emerging from this study are drawn as conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Impacts of pandemics on hospitality

The threat of pandemic emergence has increased in the 21st century (Hall et al., 2020) as a result of various reasons including: the growing mobility of the population, urbanisation, the industrialisation of food production processes and the expansion of global transport networks which contributes to the transmission of pathogens (Connolly et al., 2020; Hall, 2020). The outbreak of diseases like SARS, MERS, the Ebola and Zika viruses and more recently Covid-19 stands as evidence of the growing pandemic threat. In this context, the global tourism industry has been identified as a contributor to the spread of diseases (Nicolaides et al., 2019) as the more people travel, the more likely it is for a disease to spread internationally. On the other hand, the industry was also recognised as being highly susceptible to pandemics, incurring significant economic costs (Kuo et al., 2008) as pandemics negatively influence tourist demand and destination perceptions (Novelli et al., 2018). One sector of the tourism industry that is regarded as highly impacted by pandemics is hospitality, given its vulnerability to health-related crises (McKinsey and Company, 2020c).

Numerous studies examining the effects of pandemics on hospitality may be found in the literature (e.g. Alan et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Chien and Law, 2003; Kim et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2010). This pool of work illustrates the adverse effect of a pandemic on hotel occupancy rates, revenues and stock performance, reminding us of the importance of sanitation and hygiene within the sector (Naumov et al., 2020). Evidently, pertinent studies highlight the significance of response mechanisms of hospitality businesses to epidemics (Henderson and Ng, 2004; Kim et al., 2005) whilst identifying customers’ self-protective behaviours as equally important (Chuo, 2014). In this context, hospitality businesses’ reactions to pandemics through risk assessment, formal planning and integrated, contingency plans have been noted as particularly critical for the recovery of the sector (Jayawardena et al., 2008). Likewise, support from national governments through assistance programmes was identified as a key factor contributing to sector recovery (Chien and Law, 2003). Equally, human resource strategies were acknowledged as important in crisis management efforts during pandemics, with Leung and Lam (2004) suggesting unpaid leave and involuntary separation as common immediate solutions by hotels.

In this context, pandemic-related studies indicate that travel behaviour tends to return to normal as soon as the situation is controlled by authorities. Drawing from the SARS experience, several studies point out to the risk-taking behaviours of travellers (e.g. Lau et al., 2004) whilst reporting that travel resumes to normalcy as soon as the situation allows it (Dombey, 2004; Zeng et al., 2005). While much of the previously noted pandemics were short-lived (Gössling et al., 2020), the newly emergent Covid-19 virus though is anticipated to have long-lasting effects on the tourism and hospitality industry (Ying et al., 2020). Although there are instances of tourists demonstrating irresponsible behaviours during the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g. Guy, 2020), in most cases travel behaviour has been greatly affected as many individuals will opt for domestic holidays in 2020 (Euronews, 2020). As a result of increasing fears among the general public, industry stakeholders have expressed plans to improve hygiene standards. For instance, hotel companies have announced revisions in their cleaning protocols and food and beverage offerings (Bagnera et al., 2020) with robotics adoption emerging as a preferred option to minimise human contact (Zeng et al., 2020). Whilst the traditional hospitality industry seems willing and capable of adjusting its operations, concerns have been raised over the future of the P2P accommodation sector and, specifically, the ability of hosts to follow suit.

2.2. Impacts of Covid-19 on P2P accommodation

P2P accommodation has emerged as a disruptor on the traditional hospitality sector due to their growing popularity (Sigala, 2017). Referring to online networking platforms through which individuals can rent out for a short period of time their under-utilised property space (Belk, 2014), P2P accommodation has grown immensely as a result of the numerous benefits it may offers to travellers and property owners. For travellers (guests), it offers a convenient, value-for-money accommodation option (Stors and Kagermeier, 2015; Tussyadiah, 2016) that is generally regarded as more authentic and localised than hotel stays (Mody et al., 2019a,b; Paulauskaite et al., 2017) offering a ‘home away from home’ feeling (Liang et al., 2018). For property owners (hosts), P2P accommodation offers opportunities for entrepreneurship (Zhang et al., 2019) and additional income (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020; Guttentag, 2015) that improves individuals’ standard of living (Lutz and Newlands, 2018). Similarly, through hosting individuals have the opportunity to engage in social interaction (Moon et al., 2019) and share experiences, particularly when hosts rent rooms in their homes (Farmaki and Stergiou, 2019). In addition, it has been argued that through P2P exchanges hosts receive gratification for providing a good hospitality service (Lampinen and Cheshire, 2016). These economic and social benefits drive P2P accommodation users to engage with platforms either as hosts or guests.

In recent years changes have been observed in the P2P accommodation sector as the growth of certain platforms (i.e. Airbnb) and the competition among hosts has led to the adoption of professional hospitality standards (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020; Farmaki et al., 2020). The professionalisation turn in P2P accommodation was also encouraged by the decision of platforms like Airbnb to open up their space to professional accommodation providers such as boutique hotels and attract people who would never thought of staying in a P2P accommodation before like business travellers (Guttentag and Smith, 2017). For example, Airbnb introduced new search tools for business travellers allowing more customised search results. Likewise, the platform launched a ‘superhost’ and ‘superguest’ badge that resemble hotel loyalty schemes and award benefits (i.e. discounts) to dedicated users (Liang et al., 2017). Another recent addition of the platform was ‘Airbnb Plus’ which refers to an elite selection of properties that have “exceptional hosts” and ‘Airbnb Luxe’ that includes luxury properties that come with the services of a dedicated concierge (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020). In this context, P2P accommodation hosts started to offer services such as airport pick-ups, meals and concierge service that resemble those of hotels (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020) in a bid to reach superhost status and improve their search results and profitability.

Evidently, while the provision of a clean, functionable property and quality tangibles (Farmaki et al., 2020; Moon et al., 2019) continues to be a key prerequisite for guest satisfaction (Priporas et al., 2017), the recent changes in the P2P accommodation sector point towards increasing guest expectations (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020). Several studies identify cleanliness and tidiness as key factors for P2P accommodation guest satisfaction (Lyu et al., 2019; Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017) alongside other elements such as location, amenities and facilities (Cheng and Jin, 2019). Nonetheless, there is a growing number of studies that highlight the increasing demand for host friendliness, responsiveness and hospitableness (Chen and Jin, 2019; Gunter, 2018; Mody et al., 2019a,b; Xie and Mao, 2017) in addition to hotel-like products and services. Hence, what influences the guest experience and drives demand for P2P accommodation is a combination of tangible elements as well as intangible practices, reflecting host attitudes and personality (Sthapit and Jiménez-Barreto, 2018; Zhu et al., 2020) that denote the quality of the overall service offered (Ju et al., 2019). As such, it is not surprising that a hybrid form of service is emerging in the hospitality industry combining home feeling with professional hospitality service provisions (Farmaki et al., 2020)

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, nonetheless, has challenged P2P accommodation host practices, revealing the sector’s vulnerability to pandemics. According to industry analysts, hotels will have an advantage over P2P accommodation rentals in the post-Covid era primarily due to the lack of standardisation in P2P accommodation host practices which, in turn, may make the public wary regarding the hygiene of their properties and the fairness of their terms (Glusac, 2020). Although the morality of hosts in maintaining responsible behaviours and hosting practices was previously noted (Farmaki et al., 2019), it was especially highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic and in relation to practices such as cancellation of bookings. Also, while many hosts offered their properties for free to Covid-19 responders and health workers (GTP, 2020), others driven by economic motives defied lockdown laws and advertised their properties as ‘Covid-19 retreats’ (Criddle, 2020). Another hosting aspect that is impacted by the pandemic is the interaction with the guest which represents an essential element of the experience (Farmaki and Stergiou, 2019), yet is compromised by the social distancing guidelines imposed by national governments as a measure to combat the spread of the Covid-19 virus. Indeed, the pandemic led individuals and accommodation providers to engage in protective behaviours. Although hosts were urged to follow prevention measures (Jamal and Budke, 2020), cost-benefit evaluations tamper hosts’ decision to engage in protective behaviour (Cahyanto et al., 2016). In this context, the perceptions of hosts and their responses to the Covid-19 pandemic emerge as significant in determining the future of the sector.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection process

Given the purpose of the research, a qualitative approach to research was regarded as more appropriate. Qualitative research may provide thick descriptions of people’s perceptions and, hence, reveal new understandings of a phenomenon (Ezzy, 2002). In particular, from May to June 2020 semi-structured interviews were performed with P2P accommodation hosts from the following countries: Croatia, Cyprus, Greece and Spain. Located in the Mediterranean basin that has been greatly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, these countries represent suitable contexts for examining hospitality issues as they are popular tourist destinations with an abundance of P2P accommodation properties. Nonetheless, each country has witnessed different experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic and showed varying responses. For example, Greece has been commended for its timely measures against the pandemic which led to a relatively low number of infected cases and deaths whereas Spain witnessed a national tragedy, with Covid-19 related deaths exceeding 28,000 cases (Pappas, 2020). Such differences in experience are likely to shape host perceptions of and reactions to the impacts of the pandemic.

Purposive sampling was used to select participants. Purposive sampling is a sampling technique where participants are selected based on specific pre-selected criteria (Etikan et al., 2016). Therefore, at the first instance, we selected P2P accommodation hosts purposively according to the following criteria: a) participants had to be active hosts on P2P accommodation platforms and b) participants had to be available and willing to participate in the study as well as be able to describe their perceptions (Bernard, 2002). The rationale of purposive sampling rests on the fact that the researchers, based on their a-priori theoretical understanding of the topic, assume that certain individuals may have important perspectives on the phenomenon in question (Robinson, 2014). In so doing, the researcher(s) from each country posted an open call on various social media platforms and P2P accommodation forums inviting members to participate in the research whilst ensuring their anonymity and data confidentiality. In order to minimise self-selection bias (Bethlehem, 2010), the researchers tried to ensure that the sample from each country was diverse enough (Ritchie et al., 2014) in terms of gender, age and host type.

Data collection came to an end when no new information was observed in the data (Fusch and Ness, 2015) and the researchers were confident that data saturation was reached (Glaser and Strauss, 2017) in accordance to the leading questions and, thus, ensuring that adequate evidence for each theme was obtained to reach conclusions (Saunders et al., 2018). Overall, 45 interviews were conducted with P2P accommodation hosts. The profile of the participants may be seen in Table 1 . The type of property of each participant was categorised according to the P2P accommodation host typology of Farmaki and Kaniadakis (2020) which includes: hosts sharing a room in their house, hosts with 1 or 2 listings renting the entire property and hosts renting an entire property that manage multiple listings (their own and of others).

Table 1.

Profile of Participants.

| Participant No. | Gender | Location | Type of Property (No.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Serres, Greece | entire property (1) |

| 2 | M | Artemida, Greece | entire property (2) |

| 3 | M | Aegina/Athens, Greece | multiple properties (5) |

| 4 | F | Athens, Greece | entire property (1) |

| 5 | M | Mykonos/Halkidiki, Greece | multiple properties (11) |

| 6 | F | Crete, Greece | entire property (1) |

| 7 | F | Athens, Greece | entire property (1) |

| 8 | F | Athens, Greece | shared property (2) |

| 9 | M | Corfu, Greece | multiple properties (40) |

| 10 | F | Pieria, Greece | multiple properties (14) |

| 11 | F | Sevilla, Spain | multiple properties (6) |

| 12 | F | Leon, Spain | entire property (1) |

| 13 | M | Tenerife, Spain | entire property (1) |

| 14 | F | Tarragona, Spain | multiple properties (7) |

| 15 | M | Sevilla, Spain | entire property (2) |

| 16 | F | Barcelona, Spain | multiple properties (5) |

| 17 | M | Barcelona, Spain | shared property (1) |

| 18 | F | Sevilla, Spain | entire property (1) |

| 19 | M | Sevilla, Spain | shared property (2) |

| 20 | M | Barcelona, Spain | shared property (2) |

| 21 | M | Zadar, Croatia | entire property (1) |

| 22 | M | Šibenik, Croatia | entire property (2) |

| 23 | F | Karlovac, Croatia | multiple properties (3) |

| 24 | F | Korčula, Croatia | entire property (2) |

| 25 | F | Dubrovnik, Croatia | multiple properties (7) |

| 26 | F | Zagreb, Croatia | multiple properties (4) |

| 27 | M | Makarska, Croatia | entire property (2) |

| 28 | M | Split, Croatia | entire property (2) |

| 29 | M | Brač, Croatia | multiple properties (4) |

| 30 | M | Split, Croatia | multiple properties (3) |

| 31 | F | Šibenik, Croatia | entire property (2) |

| 32 | F | Hvar, Croatia | entire property (1) |

| 33 | F | Zagreb, Croatia | entire property (1) |

| 34 | F | Limassol, Cyprus | entire property (1) |

| 35 | F | Protaras, Cyprus | entire property (2) |

| 36 | F | Limassol, Cyprus | multiple properties (4) |

| 37 | M | Larnaca, Cyprus | entire property (1) |

| 38 | M | Paphos, Cyprus | entire property (1) |

| 39 | F | Paralimni, Cyprus | entire property (1) |

| 40 | F | Paphos, Cyprus | multiple properties (6) |

| 41 | M | Paphos, Cyprus | multiple properties (7) |

| 42 | M | Larnaca, Cyprus | shared property (1) |

| 43 | M | Protaras, Cyprus | shared property (1) |

| 44 | M | Protaras, Cyprus | multiple properties (30) |

| 45 | M | Paralimni, Cyprus | entire property (2) |

Due to the lockdown measures imposed across Europe at the time of the data collection, the interviews were conducted over Skype or Zoom, in accordance to the participants’ date and time preference. Before each interview, the researcher(s) explained to the participants the purpose of the study and the ethical implications involved and obtained their signed consent to being recorded. The interviews lasted approximately 30−45 min each and were conducted in the local language of the researcher(s) before being translated into English. Each interview proceeded from a number of ‘grand tour’ questions (McCracken, 1988) seeking to establish the hosting profile of the participants before moving into the topic of: a) hosting motives in order to understand the drivers for engaging in P2P accommodation, b) impacts of the pandemic on host practices and their related responses and c) host perceptions of the long-term impacts of the pandemic on their hosting and P2P accommodation in general. Table 2 illustrates the questions asked.

Table 2.

Interview Protocol.

| Interview Question | Probing Question |

|---|---|

| How many years have you been a host on P2P accommodation platforms? | |

| What drove you to hosting on P2P accommodation platforms? | |

| In which platforms do you advertise your property(ies)? | Which is your favourite and why? |

| How many properties do you manage? | |

| Do you use a management app to synchronise your listings in different platforms? | Which one? |

| Would you say you have been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic? | If so, how? |

| What are the short-term economic impacts of the pandemic on your hosting activity? | |

| How has your hosting practice and operational activity changed as a result of the pandemic? | |

| Have you received petitions of cancellations of bookings asking for 100 % refund pushed by the platforms? | |

| Have you received phone calls from ‘customers service’ to encourage you to cancel bookings? | |

| Which measures are you planning to take to ensure a good level of hygiene is provided in your property(ies)? | Have you received any requests or enquiries from guests asking about hygiene? |

| Have the platforms (e.g. Airbnb) been supportive in terms of the impacts hosts have incurred as a result of the pandemic? | If so, in what ways? |

| Did you receive any support from the government as a result of the pandemic? | |

| What do you think the long-term economic impacts of covid-19 will be? | |

| How do you foresee your hosting practice evolving in the near future as a result of the pandemic? | |

| Do you plan to move to a long-term rental mode? | |

| In your opinion, how has the pandemic changed the P2P accommodation sector? | Any long-term threats or even opportunities emerging from this situation? |

3.2. Data analysis

The translated transcripts were checked by each researcher for accuracy and then imported to the NVivo software to be analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Data analysis was conducted by two researchers who employed the three coding rounds prescribed by Gioia et al. (2013). In more detail, during the first coding round the researchers ‘adhered faithfully to informant terms’ (Gioia et al., 2013: 20) by reading the transcripts line by line without imposing restrictions on the text to be analyzed (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Then, the transcripts were analysed more closely with the researchers identifying key topics in a “theory-driven” manner (Braun and Clarke, 2006:88).

To maximise analytical integrity and ensure the robustness of findings, each researcher undertook an initial round of open coding separately before converging the first set of findings in a process called triangulation. Flick (2000) posited that investigator triangulation is an effective method to balance subjective research interpretations due to the collective comparison of coding schemes. Hence, in this study researcher triangulation ensured that interviewees’ perceptions of the pandemic as pertaining to their hosting practice were objectively interpreted. Subsequently, a second round of coding was undertaken whereby emerging topics were grouped into interrelated themes by copying, re-organising and comparing thematic categories whilst refining the data under each theme to identify sub-categories (Goulding, 1999). In this way, thematic categories were expanded and clarified. Last, a third round of coding was used to combine sub-categories with the themes initially identified. In this way, relationships were validated and thematic categories were refined and further developed (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) to enhance elaboration on key issues (Hennink et al., 2010).

The following steps were undertaken to ensure reliability in data analysis. First, we ensured interpretative and evaluative rigor (Kitto et al., 2008) was maintained. For instance, in addition to participant validation of the data collected, the transcripts were read and compared by both researchers involved in the analytical process through investigator triangulation (Golafshani, 2003); thus, minimising researcher bias. Second, in completing the abstraction process, we grouped concepts and/or overlapping categories according to similarities and differences between categories which were discussed between the key researchers following the separate round of coding as proposed by Bryman and Burgess (1994). Taking Thomas and Harden (2008), as part of thematic synthesis the independent researcher identification of themes was followed by discussion among the researchers of overlaps and divergencies until agreement was reached. In so doing, the researchers followed a thorough process of record-keeping to maximise the consistency of the data interpretation and to clearly demonstrate the decision trail of grouped concepts (Noble and Smith, 2015); thus maximising transparency. Also, we ensured the coding process reflected the richness of the data collected (Moretti et al., 2011); as such, we included thick verbatim descriptions of the interviewees’ accounts to support key findings.

4. Findings and discussion

4.1. Motives to host on P2P accommodation

At the first instance, we asked participants to describe the reasons that led them to host on P2P accommodation platforms. Understanding host motives was important not only to set the background and identify differences between hosts but also to gain a better insight of their perceptions of the pandemic impacts and associated responses. Indeed, Farmaki et al. (2019) posited that P2P accommodation host behaviours are likely to be influenced by hosting motives.

Some participants argued that they host for the social benefits (Farmaki and Stergiou, 2019) emerging from the interaction with the guest and the enjoyment of hosting people in their house. For these hosts, continuous bookings are not necessarily a concern as they view hosting more as a hobby or a temporary arrangement as a result of personal life changes (i.e. children moving away from home) from which they get personal gratification. Generally, though, financial gains emerged as the primary motive for hosting in line with extant literature (e.g. Guttentag, 2015). Around a third of the participants claimed that P2P accommodation was their first source of income. As the discussion progressed, it became obvious that many of those hosts emerged as ‘professionals’ in the P2P accommodation domain (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020), often managing multiple listings that are not just their own but also the properties of others. For these hosts, P2P accommodation has proven to be a lucrative employment option (Zhang et al., 2019) that is simultaneously flexible. For example, a participant argued that managing P2P accommodation properties offers her a good work-life balance, stating that “this job does not distract me from my baby” [P35, Cyprus]. In their majority, ‘professional’ hosts seem to have started hosting using a 1 or 2 personal properties and then used their profits to acquire additional ones to expand their business. Within this type of hosts, we also identified participants that were previously involved in long-term renting; yet, they decided to switch to short-term rentals via P2P accommodation platforms as their popularity grew, allowing them to earn more money. A few participants, though, stated that they continue to manage long-term rentals alongside P2P accommodation properties “depending on the type and location of the property and demand” [P10, Greece]. In addition, for some ‘professional’ hosts, the transition to P2P accommodation came about as a result of negative experiences with tenants. In the words of a participant:

“[(the tenant) left without telling me anything…left the apartment in very bad conditions…the deposit didn’t cover all the damage. So, I thought I had to control the apartment closer” [P14, Spain].

Further on, we asked the participants to state which platforms they use to advertise their properties, explaining which is their favourite. Although several participants, especially professional hosts, seem to use various platforms (e.g. Expedia, Lastminute, Splendia, Homeaway, MrBnB, Wimdu and other local ones) for greater exposure, Airbnb and Booking.com emerge as the most popular. Some participants seemed to prefer Booking.com as they claim it offers more reservations or a higher quality clientele; nonetheless, the majority identified Airbnb as their favourite, citing numerous reasons for their choice. For instance, participants stated that Airbnb is more user friendly, popular and flexible to use whilst commands lower commission fees than Booking.com. Participants also added that Airbnb is more “pro-people” [P14, Spain] and “host-oriented” [P28, Croatia] as it allows hosts to review guests as well while laying down their own house rules. Regardless, hosts on both Airbnb and Booking.com commented on the ease of using the features of platforms to synchronise calendars across platforms, which also explains why most hosts do not use a channel management app.

4.2. Short-term impacts of the pandemic on hosts

Following, we asked participants to elaborate on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on their hosting practice. Unsurprisingly, all the participants stated that they have been directly and negatively affected by the measures undertaken by governments to control the spread of the pandemic. Indeed, many participants are based in tourist destinations, with a large proportion of their bookings coming from foreigners who at the time of the pandemic were unable to fly (Sahin, 2020). Specifically, hosts argued that they not only saw their bookings cancelled but also requests to book their properties ceased, illustrating similar pandemic effects as in mainstream hospitality (e.g. Chien and Law, 2003; Kim et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2010). With the exception of a few participants who said that they had booking requests from locals who wished to stay in their properties (i.e. healthcare workers distancing from their families, people stranded in the country), hosting for most was basically put on hold. In fact, some participants claimed to have closed their property on the platforms to ensure it is not available for bookings during the pandemic, fearing contagion or platform collapse. The following extracts reflect such sentiments:

“If I host someone in my apartment who is not very careful, I can get the virus from this person. The host is always risking to get the virus by hosting” [P17, Spain].

“My parents live downstairs, they are old and vulnerable. Also, I see there are problems with Airbnb as it has fired employees…so I changed the limit of the money that Airbnb can transfer as I was afraid the platform would collapse” [P7, Greece].

Even so, ‘professional’ hosts seemed to have experienced the greatest impact as hosting represents their main source of income. While hosts in general expressed difficulty in paying their mortgages/rents and covering maintenance costs as a result of the loss of bookings, ‘professional’ hosts in particular found themselves in a dire economic situation. For example, participants expressed difficulty in “paying rent to property owners” [P44, Cyprus] or even covering the salaries of employees such as cleaners, indicating that the pandemic has had an effect on other actors as well. As a participant put it:

“I have no job and I cannot pay the lady who is cleaning our properties. I feel very sad about this situation…the unemployment office pays only about 60 % of your original salary…if my husband doesn’t work, we are near to bankruptcy…” [P35, Cyprus].

In order to try to adapt their hosting activity to the pandemic, participants reported different strategies. For example, to boost demand they claimed that they will “lower prices…to attract new guests this year” [P30, Croatia] although a few participants said they might “raise prices…to recover the lost profit” [P18, Spain]. Other practices participants are contemplating on adopting include: targeting domestic tourists, introducing self-check in to minimise human context, offering antiseptic gels to guests, disinfect the apartments, invest in buying ozone machines for better cleaning and allow 24 h between bookings. These practices seem to be in line with those suggested within the mainstream hospitality industry (Bagnera et al., 2020). In this context, some participants commented on how they previously maintained “high levels of hygiene” [P31, Croatia] with some, though, acknowledging that such practices may not have been adopted by everyone and even suggesting “some kind of certification of cleaning so that it is not done by individuals or the hosts themselves” [P6, Greece].

4.3. Support (or lack of) from platforms and the government

When asked if they thought the platforms were supportive of hosts during the pandemic, the majority of participants answered negatively. As a participant put it, “Airbnb returned the full amount to all users of its services without asking the host” [P21, Croatia]. Other participants agreed, commenting how platforms “reacted spontaneously” [P25, Croatia] as the situation was new to them, leading to host resentment (Johnson and Davis, 2020). More critical participants argued that “the platforms are always pro-guests” [P11, Spain], with some participants highlighting that Airbnb especially was never supportive to hosts as their main strategy is “to grow its clientele” [P2, Greece]. This argument is in line with past studies claiming that the Airbnb is becoming guest-oriented (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020). The major controversy was related to the fact that hosts, who had a strict cancellation policy on Airbnb or non-refundable in other platforms like Booking and usually receive 50 % of the amount of the booking in case of cancellation, were forced to provide a 100 % refund. As some hosts explained, this was perceived as a betrayal of the platform since they had compromised with less bookings due to that policy to secure some funds. For example:

“Airbnb cancelled the bookings on my behalf. Airbnb didn’t respect the hosts cancellation policies. There was a kind of contract between the platforms and the hosts where each host could choose the type of cancellation policy: strict, moderated or flexible. Obviously each cancellation policy has pros and cons. For instance, if you choose a strict cancellation policy, you may not have so much demand, compared to a more open cancellation policy, but you secure part of the payment in case of cancellation” [P20, Spain].

Nonetheless, some participants felt that the platforms were communicative and did their best given the unprecedented situation. Demonstrating a more empathetic stance, a participant stated that the platforms “informed us in a timely manner of the situation affecting us, but neither could perform miracles” [P23, Croatia]. Others claimed they cancelled the bookings because they put themselves in guests’ shoes. “I would do the same [as a guest]. I’d ask for a refund, it is a superior force [pandemic] I did not expect what Airbnb would say, it is an issue of being humane” said a participant [P2, Greece]. Another host explained how he appreciates that Airbnb launched a $250 Million fund aimed to help hosts who had strict cancellation policies while pointing that Booking did not offer any help:

“Airbnb has prepared $250 million in support for paying all people 25 % of what they should have received as the cancellation fee. To put it simply, if you had a strict policy that pays you 50 % of the total price in case of cancellation, you get 25 % of that 50 %, which is ultimately 12.5 % of the total price. Although it is only a tenth of the total price, Airbnb's consideration for the hosts was appreciated. I point out that Airbnb takes only 3% commission from the hosts and Booking.com that did not help the hosts in any way takes 15 %” [P28, Croatia].

In relation to this point, participants highlighted the positive outcome of receiving at least part of the booking with some going further and suggesting amendments in platform policies such as the issuance of “a travel insurance in case of cancelling bookings” [P44, Cyprus]. One host explained how he reacted very quickly and cancelled all his bookings, which then prevented him for getting the support:

“I did a small mistake because I cancelled my bookings and return all money back to my guests at the very beginning. So, I am not allowed to get any refund out of these. Because, if my guests would cancel their stay and not me, then I would get some money back, but I did not know about this” [P38, Cyprus].

The way Airbnb announced the ‘help scheme for hosts’ was deemed misleading by some hosts. The information was not very clear and many hosts believed the help was for all hosts and not only for the hosts with strict cancellation policies. Also, hosts complained about the lack of information about the ‘superhost help scheme’ aimed at superhosts who only have one property and depend 100 % on the earnings from that property. Some superhosts who fit the requirements called Airbnb to request information and they were told they would be contacted by Airbnb but never received any communication. As a host put it, “Airbnb lied to us, they told us they were going to help us but they didn’t” [P19, Spain]. In addition, some participants pointed to platforms’ indirect ‘manipulation’ of the situation commenting that they “contacted the guest to suggest to cancel the booking under the Covid-19 protocol where the set cancellation policy is not applicable and the guest could receive 100 % refund” [P20, Spain] whilst “keeping their fee” [P16, Spain]. Such arguments confirm P2P accommodation platforms’ pro-guest mentality, as previously highlighted by Farmaki and Kaniadakis (2020). Unsurprisingly, many hosts expressed feeling marginalised from the platforms, suggesting that the platforms “don’t treat hosts as partners” [P44, Cyprus]. As such, hosts commented on how there was poor communication with the platforms as in some cases hosts had made their own arrangements with guests; thus, confirming reports of P2P accommodation platforms’ lack of strategic thinking in the pandemic (Carpenter, 2020) and support past studies that emphasise contingency plans of hospitality companies as key for their recovery (Jayawardena et al., 2008). In addition to refunds, participants stated that platforms promised to offer guests a change of dates in bookings or travel vouchers, which came after hosts expressed dissatisfaction with the refund policy (Shuk, 2020; Webster, 2020):

“Booking.com is starting to offer a change of dates or a voucher to travel in the future. But at the beginning they were just refunding everyone 100 % because of force majeure” [P11, Spain].

Nonetheless, as participants explained, in many cases these alternatives were not preferred by guests, who usually preferred the 100 % refund. Participants were also equally critical of governments, citing lack of support to hosts despite their important role in assisting the hospitality sector to recover (Chien and Law, 2003). Although ‘professional’ hosts claim to have received some money from government as part of their subsidy to companies, many participants highlighted the unregulated context in which P2P accommodation operates as limiting the potentiality of compensation from governments. In the words of a participant, “I do not think that the government would like to give to hosts any help, since some policy makers believe that they are cheating and not paying their taxes to the government”[P40, Cyprus]. In fact, several participants said that they don’t expect monetary assistance from the government.

4.4. Long-term perspectives of pandemic impacts

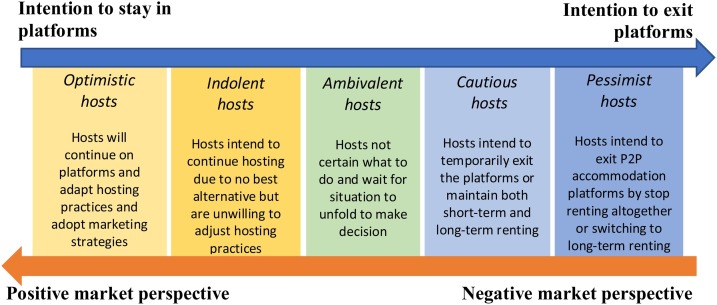

Consequently, we diverted our attention to hosts’ long-term perspectives and intentions following the pandemic. In relation to this point, participants expressed varying views leading us to categorise them accordingly. Specifically, as analysis progressed, we identified two main types of hosts in terms of their perspectives: the ‘optimistic hosts’ and ‘pessimistic hosts’ which we were able to further categorise according to their decision to exit the platforms or not. Overall, five types of hosts were identified and categorised on a continuum (Fig. 1 ) according to their long-term perspective (i.e. decision to continue hosting on P2P accommodation platforms) and level of practice adjustment.

Fig. 1.

Continuum of host pandemic responses.

4.4.1. Pessimistic hosts

On the right-hand side of the continuum, ‘pessimistic hosts’ stated that they intent to either “sell the property given the situation” [P12, Spain], “give up renting altogether” [P32, Croatia] or “switch to long-term renting” [P35, Cyprus]. For these hosts, the pandemic has exposed the vulnerable aspects of the P2P accommodation sector, threatening its existence as “the system has become weak” [P7, Greece]. Such arguments support previous research findings which postulate that the power dynamics in P2P accommodation, fostered by platforms’ favouring approach to guests, is driving hosts out of the platforms (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020; Farmaki et al., 2020). Pessimistic hosts also claimed that tourists would choose hotels over P2P accommodation in the current situation, for example: “Tourists will probably choose hotels rather than private accommodation because hotels have some standards and for private accommodation there is always a surprise factor” [P32, Cyprus].

4.4.2. Cautious hosts

We also identified ‘cautious hosts’ who appear to contemplate on shifting or returning to long-term rental, albeit temporarily as a reaction to the current situation and until things improve. “(Will move to long-term rental) at least for 1 or 2 years. We need to make some money, so the best solution is long-term accommodation” said a participant [P34, Cyprus]. Likewise, some ‘cautious hosts’ argued that to maximise their feeling of security, they’ll opt to rent both short-term and long-term type of properties. In the words of a participant, “we have created a website where we are going to mix long-term and short-term rental” [P15, Spain].

4.4.3. Ambivalent hosts

In the middle of the continuum, we placed hosts who claimed that it is not possible to foresee the future of the sector due to the unknown outcome of the pandemic. As such, these hosts which we labelled ‘ambivalent hosts’ stated that they will wait to see “how the situation unfolds” [P32, Cyprus] before making any decisions to continue hosting on P2P accommodation platforms or exit. As a participant explained, “I am waiting for the airports to open first and see what type of people will come…” [P4, Greece].

4.4.4. Indolent hosts

Moving towards the left-hand side of the continuum, there were ‘indolent’ hosts who stated that they will continue renting through P2P accommodation platforms due to a number of reasons. For example, several participants argued that they cannot switch to long-term renting as their properties are in touristic locations and thus “not suitable for long-term renting” [P29, Croatia]. Other participants explained that renting through P2P accommodation platforms is preferable as they can achieve higher profits than long-term renting or, in many cases, long-term renting is not possible as the rented property is attached or within the ground of the host’s house. Another key factor that seems to deter hosts from renting long-term is that “long-term renting has many problems” [P4, Greece] including damages to the property that the owner is not being compensated for, unpaid rents and in some legal contexts inability to evict unruly tenants. Even so, these hosts seemed unwilling to change their hosting practices as a result of increased hygiene and safety risks. In the words of a participant, “I don’t intent to change anything. I prefer to have it closed than go into the mentality of being a labourer of the property” [P2, Greece].

4.4.5. Optimistic hosts

On the other end of the continuum, there were participants who emerged as ‘optimistic hosts’ as they believed that the pandemic has brought opportunities that will positively transform the P2P accommodation sector. Specifically, participants claimed that the pandemic will reinforce demand for P2P accommodation as hotels run greater risk of infection and, thus, people will prefer to stay in more isolating types of accommodation with less personal contact. Such statements counteract initial estimations by media reports that the P2P accommodation sector will be negatively affected by the pandemic due to the lack of standardisation in host practices that reinforces concerns over health and safety criteria (e.g. Glusac, 2020). In the words of a participant, “there is going to be a complete shift in the way we travel. Massive tourist trip, trips for just a weekend, low cost travel, all of that is going to change” [P16, Spain]. Within this context, participants argued that “there will be a cleaning up” [P11, Spain] in the sector as the pandemic is removing the opportunists. As a participant summed it up “the image that ‘anyone rents a property in Airbnb’ will change” [P6, Greece]. In relation to this point, some participants commented on how the transition of some hosts to long-term renting will be good for the society as long-term rent will decrease. Generally, ‘optimistic hosts’ seem to plan their future hosting practices accordingly and expressed their intentions of making adjustments. For example: “I have always left one day in between bookings. Now I may even leave 2 days” [P13, Spain].

5. Conclusions and implications

Overall, three conclusions are derived from this study. First, the pandemic’s effects have been equally great on P2P accommodation as on mainstream hospitality providers (e.g. Wu et al., 2010), with hosts experiencing both losses of revenue and future booking requests. In the case of professional hosts, the effects of the pandemic extended into inability to pay for salaried staff (i.e. cleaners) and other company-related expenses. Second, with economic benefits driving individuals to host on P2P accommodation platforms (Guttentag, 2015), it is not surprising that hosts are contemplating to continue hosting on the platforms in hope that the situation will improve and they will resume making profits. Nonetheless, our study identified hosts that have decided to exit the platforms and recover by turning to long-term renting. The decision to exit the platforms seems to have been encouraged by hosts’ disappointment over the minimal support received from platforms which, according to our findings, are exhibiting a “pro-guest” mentality that victimises hosts. For instance, hosts expressed frustration over the way the platforms handled the pandemic by encouraging guests to ask for full refunds. This leads to the third finding of our study which reveals a variety in host responses with regard to the pandemic’s impacts. Specifically, we depict the different types of hosts on a continuum (Fig. 1) in accordance to their long-term market perspective and hosting practice adjustment depending on their decision to stay or exit P2P accommodation platforms. In light of these conclusions, this study carries both theoretical and practical implications.

5.1. Theoretical implications

Although the relationship between pandemics and hospitality has been previously investigated (e.g. Chen et al., 2007; Henderson and Ng, 2004), this study represents the first attempt to examine the impacts and associated responses of pandemics in a P2P accommodation context. As such, the study sheds light on P2P host practices during a pandemic by exposing the factors driving host decision-making, which does not revolve around economic benefit solely but encompasses personal aspects including ability to respond to health and safety expectations. Specifically, the study advances theoretical understanding of the pandemic-hospitality nexus which has insofar focused on destination-level and sectoral-based analyses (Gössling et al., 2020) by investigating micro-level stakeholders’ perspectives. In so doing, the study reveals a variance in perceptions and responses of hosts to pandemics which led us to categorise them along a continuum in terms of their market perspective and intention to continue hosting on P2P platforms.

On the one end of the continuum, there are ‘optimistic hosts’ that will continue hosting on platforms whilst altering their practices to comply to the emerging need for better health and safety standards. These hosts seem to understand that health and safety are regarded as key in hospitality provision (Zemke et al., 2015) and are willing to adapt their strategies, contrary to ‘indolent hosts’ who plan to continue their hosting activities without adaptation of their practices. The sentiments of ‘indolent hosts’ seem to emanate from their belief that their practices are adequately responsive to health standards or their decision to withstand the additional pressures of the platforms and guests on their practice (Buhalis et al., 2020; Farmaki et al., 2020). On the other end of the continuum, there are ‘pessimistic hosts’ who intend to cease P2P hosting altogether and turn to long-term renting as well as ‘cautious hosts’ who prefer to maintain both short-term and long-term rentals for greater safety. Additionally, we identified hosts that were ambivalent towards their future responses to the pandemic, preferring to see how the situation will unfold before making a decision.

The figure can serve as the basis for further investigation into the effects of pandemics on P2P accommodation users, primarily by illustrating the need to acknowledge existing variance in service providers’ perceptions and responses to crises. Correspondingly, the figure may enable researchers to identify specific behaviours and, thus, understand influencing factors and relationships between actors in P2P accommodation in order to articulate more targeted questions and designs within their research.

5.2. Practical implications

The study also offers practical implications. For instance, our typology of host pandemic responses (Fig. 1) can be useful to P2P accommodation platforms as it may offer some indications related to the improvement of their governance. As the figure illustrates, there are several types of hosts that depict varying responses in the midst of pandemics. As such, platforms need to adopt a more targeted approach in the development of their crisis management policies and strategies as well as their overall support measures to hosts. Otherwise platforms run the risk of losing members, especially individual hosts who tend to share their space and are often unable to meet the increasing needs of guests and/or even platform themselves (Farmaki and Kaniadakis, 2020). Considering that many users of P2P platforms seek a sharing type of property for social reasons (Farmaki and Stergiou, 2019), such a risk might prove to be unprofitable for platforms. In this context, platforms may consider establishing travel insurance features on bookings that will safeguard hosts and/or providing a range of support measures depending on varying types of hosts. Given the unregulated environment of P2P accommodation which fosters the lack of governmental support towards hosts during the pandemic, it is important that platforms step up to ensure responsibility towards all of their members. In this sense, this study could also inform policymakers in order to help them design appropriate policies to regulate the P2P accommodation market sector.

Although questions have been raised over the future of the P2P accommodation sector as a result of the pandemic, the unprecedented situation revealed underlying opportunities which platforms may exploit (Glusac, 2020). For example, our study found that ‘optimistic hosts’ anticipate demand for P2P accommodation to grow as they are more isolated than hotels. Thus, platforms need to promote the related benefits of staying in P2P accommodation opposed to traditional accommodation whilst, simultaneously, ensuring that hosts adhere to the required health and safety standards. As such, platforms need to promote a proactive evaluation process before booking in addition to post-stay reviews by, perhaps, offering specific health certifications to hosts who fulfil a set of required criteria. Even though health and safety are core to the hospitality product (Naumov et al., 2020), cleanliness and tidiness are key factors for guest satisfaction in P2P accommodation (Lyu et al., 2019; Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017). The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of such factors further, heightening them into a prerequisite determining the future of the sector. The supportive stance of platforms is of particular importance for ‘ambivalent hosts’ who are still indecisive of their future responses. In this context, out typology may be of use to practitioners of P2P accommodation allowing them to self-identify with a specific category of host pandemic response and adopt the tactics that are most suited to their needs, preferences and capabilities.

5.3. Limitations and further research

This study drew from a European context only; hence, it is advisable that future research examines hosts’ perceptions and responses to pandemics within other cultural contexts. Similarly, as this study focused on host perspectives it may be worth if future research considers guest views in order to identify potential gaps between guest health and safety expectations and host practices. Likewise, researchers may also examine the social impacts of the pandemic on hosts sharing a room in their house as these are more likely to engage in hosting due to social motivations. Researchers may also embark on a comparative investigation in terms of the crisis management strategies adopted in P2P accommodation and mainstream hospitality to observe areas of convergence and divergence as well as best practices. Furthermore, the views of policymakers on the impacts of the pandemic, especially in terms of long-term renting, and their related responses is another area of investigation worth considering. Generally speaking, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on the global tourism and hospitality market (Gössling et al., 2020); nonetheless, the pandemic has opened Pandora’s box for P2P accommodation platforms exposing the vulnerable aspects of the sector. As such, the future of the sector remains to be seen.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Higher Education Curricula Development on the Collaborative Economy in Europe (COLECO)Grant Agreement Number: 2019-1-UK01-KA201-062118 Funder: Erasmus + Key Action 2 Strategic Partnerships for Higher Education.

References

- Alan C.B., So S., Sin L. Crisis management and recovery: how restaurants in Hong Kong responded to SARS. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006;25(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Almeida M., Bremser K. Strategic responses of the Spanish hospitality sector to the financial crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;32:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- American Hospitality and Lodging Association . 2020. Covid-19’s Impact on the Hotel Industry.https://www.ahla.com/covid-19s-impact-hotel-industry [accessed on 8 May 2020] Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnera S.M., Stewart E., Edition S. Navigating hotel operations in times of COVID-19. Boston Hospitality Rev. 2020 ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Belk R. You are what you can access: sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014;67(8):1595–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H.R. Qualitative data analysis I: text analysis. Res. Methods Anthropology. 2002:440–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bethlehem J. Selection bias in web surveys. Int. Stat. Rev. 2010;78(2):161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A., Burgess R.G. Routledge; London: 1994. Analyzing Qualitative Data. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyanto I., Pennington-Gray L., Thapa B., Srinivasan S., Villegas J., Matyas C., Kiousis S. Predicting information seeking regarding hurricane evacuation in the destination. Tour. Manag. 2016;52:264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. 2020. Airbnb Demonstrates Lack of Strategic Thinking in Response to Covid-19.https://vrmintel.com/airbnb-demonstrates-lack-of-strategic-thinking-in-response-to-covid-19/ VRMintel [accessed online 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- CBRE . 2020. Insights and Implications of Covid-19 Pandemic.https://www.cbre.com/covid-19 [accessed online on 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.H., Jang S.S., Kim W.G. The impact of the SARS outbreak on Taiwanese hotel stock performance: an event-study approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007;26(1):200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M., Jin X. What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;76:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chew E.Y.T., Jahari S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: a case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014;40:382–393. [Google Scholar]

- Chien G.C., Law R. The impact of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome on hotels: a case study of Hong Kong. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2003;22(3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0278-4319(03)00041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuo H.Y. Restaurant diners’ self-protective behavior in response to an epidemic crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014;38:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly C., Keil R., Ali S.H. Extended urbanisation and the spatialities of infectious disease: demographic change, infrastructure and governance. Urban Stud. 2020 ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., O’Connell J.F., Efthymiou M., Guiomard C., Lucey B. The impact of terrorism on European tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019;75:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Criddle C. 2020. Airbnb Hosts Defy Lockdown Laws with ‘Covid-19 Retreats’.https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52184497 BBC News [access online 5th July 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Dombey O. The effects of SARS on the Chinese tourism industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004;10(1):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan I., Musa S.A., Alkassim R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016;5(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Euronews . 2020. Taiwan Kickstarts Domestic Tourism after Containing Coronavirus Spread.https://www.euronews.com/2020/06/29/taiwan-kickstarts-domestic-tourism-after-containing-coronavirus-spread Euronews [accessed online 16th July 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. 2020. Airbnb’s Future Is Uncertain as It Continues to Struggle Through Its Covid-19 Response.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/06/can-airbnb-survive-the-coronavirus-pandemic.html CNBC [accessed online 11 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Ezzy D. Routledge; London: 2002. Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Kaniadakis A. Power dynamics in peer-to-peer accommodation: insights from Airbnb hosts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Kladou S. Why do Airbnb hosts discriminate? Examining the sources and manifestations of discrimination in host practice. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020;42:181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Stergiou D.P. Escaping loneliness through airbnb host-guest interactions. Tour. Manag. 2019;74:331–333. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Stergiou D., Kaniadakis A. Self-perceptions of Airbnb hosts’ responsibility: a moral identity perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki A., Christou P., Saveriades A. A Lefebvrian analysis of airbnb space. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020 80: ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2000;9(2):127. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch P.I., Ness L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report. 2015;20(9):1408. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia D.A., Corley K.G., Hamilton A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods. 2013;16(1):15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. Routledge; UK: 2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- Glusac E. New York Times; 2020. Hotels Vs Airbnb: Has Covid-19 Disrupted the Disrupter?https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/travel/hotels-versus-airbnb-pandemic.html [accessed online on 14 June 2020]Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Report. 2003;8(4):597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding C. University of Wolverhampton; Wolverhampton: 1999. Grounded Theory: Some Reflections on Paradigm, Procedures and Misconceptions. Working paper series, WP006/99. [Google Scholar]

- GTP . 2020. Airbnb Hosts Provide Housing to Covid-19 Responders.https://news.gtp.gr/2020/03/30/airbnb-hosts-provide-housing-covid-19-responders/ Greek Travel Pages [accessed 5th July 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Gunter U. What makes an Airbnb host a superhost? Empirical evidence from San Francisco and the Bay Area. Tour. Manag. 2018;66:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag D. Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015;18(12):1192–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag D.A., Smith S.L. Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotels: substitution and comparative performance expectations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017;64:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Guy J. 2020. Spanish Island Closes Party Strip After Rowdy Tourists Flout Coronavirus Laws.https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/majorca-travel-incidents-scli-intl/index.html CNN Travel [accessed online 16th July 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M. Biological invasion, biosecurity, tourism, and globalisation. In: Timothy D., editor. Handbook of Globalisation and Tourism. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham, UK: 2020. pp. 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.C., Ng A. Responding to crisis: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and hotels in Singapore. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004;6(6):411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M., Hutter I., Bailey A. Sage; London: 2010. Qualitative Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal T., Budke C. Tourism in a world with pandemics: local-global responsibility and action. J. Tour. Futures. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena C., Tew P.J., Lu Z., Tolomiczenko G., Gellatly J. SARS: lessons in strategic planning for hoteliers and destination marketers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2008;20(3):332–346. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C., Davis J. NBC Los Angeles; 2020. Airbnb Hosts Struggle with Loss of Reservations, Income Due to Pandemic.https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/airbnb-hosts-struggle-with-loss-of-reservations-income-due-to-pandemic/2357744/ [accessed online 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Ju Y., Back K.J., Choi Y., Lee J.S. Exploring Airbnb service quality attributes and their asymmetric effects on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;77:342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.S., Chun H., Lee H. The effects of SARS on the Korean hotel industry and measures to overcome the crisis: a case study of six Korean five-star hotels. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2005;10(4):369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Kitto S.C., Chesters J., Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med. J. Aust. 2008;188(4):243–246. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H.I., Chen C.C., Tseng W.C., Ju L.F., Huang B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 2008;29(5):917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampinen A., Cheshire C. Hosting via airbnb: motivations and financial assurances in monetized network hospitality. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2016:1669–1680. May. [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.T., Yang X., Tsui H., Pang E., Kim J.H. SARS preventive and risk behaviours of Hong Kong air travellers. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004;132(4):727–736. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P., Lam T. Crisis management during the SARS threat: a case study of the metropole hotel in Hong Kong. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2004;3(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liang S., Schuckert M., Law R., Chen C.C. Be a “Superhost”: the importance of badge systems for peer-to-peer rental accommodations. Tour. Manag. 2017;60:454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Liang L.J., Choi H.C., Joppe M. Exploring the relationship between satisfaction, trust and switching intention, repurchase intention in the context of Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018;69:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C., Newlands G. Consumer segmentation within the sharing economy: the case of Airbnb. J. Bus. Res. 2018;88:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu J., Li M., Law R. Experiencing P2P accommodations: anecdotes from Chinese customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;77:323–332. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken G. Vol. 13. Sage; UK: 1988. (The Long Interview). [Google Scholar]

- Mody M., Hanks L., Dogru T. Parallel pathways to brand loyalty: mapping the consequences of authentic consumption experiences for hotels and Airbnb. Tour. Manag. 2019;74:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mody M., Suess C., Lehto X. Going back to its roots: can hospitableness provide hotels competitive advantage over the sharing economy? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;76:286–298. [Google Scholar]

- Moon H., Miao L., Hanks L., Line N.D. Peer-to-peer interactions: perspectives of Airbnb guests and hosts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;77:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti F., van Vliet L., Bensing J., Deledda G., Mazzi M., Rimondini M. A standardized approach to qualitative content analysis of focus group discussions from different countries. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011;82(3):420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov N., Varadzhakova D., Naydenov A. Sanitation and hygiene as factors for choosing a place to stay: perceptions of the Bulgarian tourists. Anatolia. 2020:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides C., Avraam D., Cueto‐Felgueroso L., González M.C., Juanes R. Hand‐hygiene mitigation strategies against global disease spreading through the air transportation network. Risk Anal. 2019;40(4):723–740. doi: 10.1111/risa.13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble H., Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid. Nurs. 2015;18(2):34–35. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli M., Burgess L.G., Jones A., Ritchie B.W. No Ebola… still doomed’–the Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018;70:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Economics . 2020. Latest Global Outlook.https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/ [accessed online on 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Pappas T. 2020. Why Greece Succeeded As Italy, Spain Failed to Tackle Coronavirus.https://greece.greekreporter.com/2020/04/05/why-greece-succeeded-as-italy-spain-failed-to-tackle-coronavirus/ Greek Reporter [accessed online 5th July 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Paulauskaite D., Powell R., Coca‐Stefaniak J.A., Morrison A.M. Living like a local: authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017;19(6):619–628. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas C.V., Stylos N., Vedanthachari L.N., Santiwatana P. Service quality, satisfaction, and customer loyalty in Airbnb accommodation in Thailand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017;19(6):693–704. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Lewis J., Nicholls C.M., Ormston R. Sage; Los Angeles, CA: 2014. Qualitative Research Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O.C. Sampling in Interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014;11(1):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin T. Anadolu Agency; 2020. Lufthansa Applies for Short-time Work Assistance.https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/lufthansa-applies-for-short-time-work-assistance/1788026 [accessed online 15 April 2020] Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B., Sim J., Kingstone T., Baker S., Waterfield J., Bartlam B. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabra C., Reis P., Abrantes J.L. The influence of terrorism in tourism arrivals: a longitudinal approach in a Mediterranean country. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020;80 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. Silicon Canals; 2020. Book.cOm Seeks Dutch Government’s Aid to Stay Hopeful During Pandemic.https://siliconcanals.com/news/coronavirus-impact-booking-com-government-aid/ [accessed online 12 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Shuk C. The Silicon Valley Voice; 2020. Airbnb Customers Fuming Over Covid-19 Refund Policy.https://www.svvoice.com/airbnb-customers-fuming-over-covid-19-refund-policy/ [accessed online 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Sigala M. Collaborative commerce in tourism: implications for research and industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017;20(4):346–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens P. Short-term Rentalz; 2020. Booking.cOm Plans for Lay-offs after Landing $4 Billion Loan.https://shorttermrentalz.com/news/booking-com-lay-offs-loan/ [accessed online 12 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Sthapit E., Jiménez-Barreto J. Exploring tourists’ memorable hospitality experiences: an Airbnb perspective. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 2018;28:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stors N., Kagermeier A. Motives for using Airbnb in metropolitan tourism—Why do people sleep in the bed of a stranger? Reg. Newsl. Reg. Stud. Assoc. 2015;299(1):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A., Corbin J. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey A. 2020. Coronavirus in Europe: Tourism Sector ‘hardest Hit’ by Covid-19.https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/16/coronavirus-in-europe-tourism-sector-hardest-hit-by-covid-19 Euronews. [accessed online 12 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016;55:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Webster L. 2020. Booking.cOm Suspends UK Bookings After Pressure From MPs.https://www.thenational.scot/news/18394049.booking-com-suspends-uk-reservations-pressure-mps/ The National [accessed online 12 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Wood C. 2020. Airbnb Is Establishing a New Cleaning Protocol for Hosts to Limit Spread of Covid-19.https://www.businessinsider.com/airbnb-24-hours-between-rentals-limit-covid-spread-2020-4 Business Insider [accessed online on 8 May 2020] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- World Hospitality Organisation . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200331-sitrep-71-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=4360e92b_6 [accessed online on 8 May 2020]. Accessed from: [Google Scholar]

- Wu E.H., Law R., Jiang B. The impact of infectious diseases on hotel occupancy rate based on independent component analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010;29(4):751–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Mao Z. The impacts of quality and quantity attributes of Airbnb hosts on listing performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2017;29(9):2240–2260. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhang H., Chen X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying T., Wang K., Liu X., Wen J., Goh E. Rethinking game consumption in tourism: a case of the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020:1–6. [Google Scholar]