Abstract

The first step of the kynurenine pathway for L-tryptophan (L-Trp) degradation is catalyzed by heme-dependent dioxygenases, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. In this work, we employed stopped-flow optical absorption spectroscopy to study the kinetic behavior of the Michaelis complex of Cupriavidus metallidurans TDO (cmTDO) to improve our understanding of oxygen activation and initial oxidation of L-Trp. On the basis of the stopped-flow results, rapid freeze-quench (RFQ) experiments were performed to capture and characterize this intermediate by Mössbauer spectroscopy. By incorporating the chlorite dismutase−chlorite system to produce high concentrations of solubilized O2, we were able to capture the Michaelis complex of cmTDO in a nearly quantitative yield. The RFQ−Mössbauer results confirmed the identity of the Michaelis complex as an O2-bound ferrous species. They revealed remarkable similarities between the electronic properties of the Michaelis complex and those of the O2 adduct of myoglobin. We also found that the decay of this reactive intermediate is the rate-limiting step of the catalytic reaction. An inverse α-secondary substrate kinetic isotope effect was observed with a kH/kD of 0.87 ± 0.03 when (indole-d5)-L-Trp was employed as the substrate. This work provides an important piece of spectroscopic evidence of the chemical identity of the Michaelis complex of bacterial TDO.

Graphical Abstract

The utilization of heme for dioxygen activation and insertion of oxygen into organic substrates is prevalent in nature, with the best-known example being the heme-dependent monooxygenation reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes.1–3 However, hemoproteins rarely exhibit dioxygenase activity as their native biological function; such dioxygenation reactions are frequently catalyzed by nonheme metal-containing enzymes.4−9

Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) is the first functionally defined heme-dependent dioxygenase.10–12 It employs a b-type ferrous heme to catalyze the oxidative cleavage of the indole ring of L-tryptophan (L-Trp), converting it to N-formylkynurenine (NFK) (Scheme 1). In mammals, TDO is primarily a hepatic enzyme that participates in the first and rate-limiting step of the kynurenine pathway, which is the primary route of L-Trp catabolism.13−20 In addition to mammals, TDO is present in other organisms such as insects and bacteria.12,19,21–23 An isozyme of TDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), is found in nonhepatic tissues in mammals.24,25 Compared to TDO, IDO exhibits a broader substrate specificity, allowing for a collection of indoleamine derivatives as substrates.3,26−29 Although the sequences of the two heme-dependent dioxygenases are only ∼10% identical, they exhibit similar active-site architectures.23,30−32

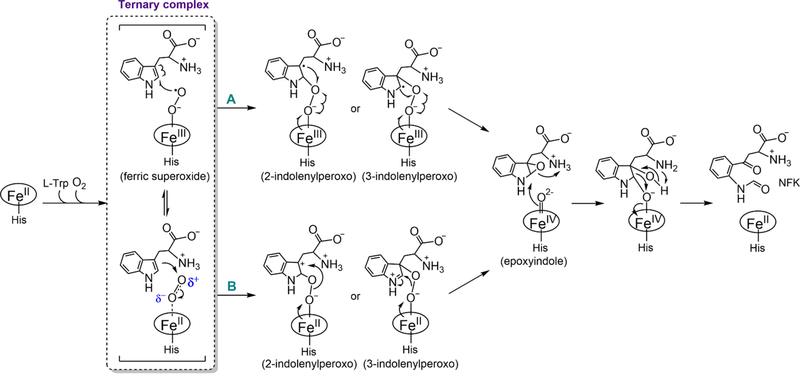

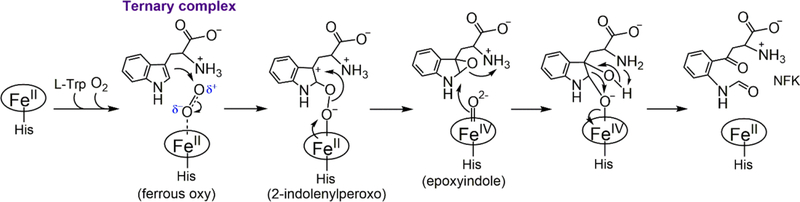

Scheme 1.

Proposed Catalytic Mechanism for IDO and TDO

During the past decade, TDO and IDO have attracted significant attention because of their physiological roles in immune regulation. They are among the checkpoint proteins that orchestrate the ultimate amplitude and quality of immune responses.33,34 A growing body of evidence has established the link between IDO/TDO upregulation and immunosuppression in cancer and other diseases.35–44 A recently published survey of human tumor cell lines revealed that 16% of tumor cell lines exhibit enhanced expression of IDO, 19% show enhanced expression of TDO, and 15% show enhanced expression of both TDO and IDO.45 These findings make elucidation of the catalytic mechanisms of TDO and IDO beneficial for inhibitor design and drug discovery.

A working mechanism of TDO is shown in Scheme 1 (adapted and modified from refs 46−53). A ternary complex [Fe(II)-O2-L-Trp] comprised of the ferrous enzyme, the primary substrate (L-Trp), and the secondary substrate (O2) is believed to be the starting point of the chemical steps. In this complex, the ferrous heme is directly coordinated by O2 with L-Trp binding at an adjacent binding pocket.53 During the past few decades, the scientific community has held the assumption that TDO and IDO share a common catalytic mechanism in their reactions.2,3,49,52 However, on the basis of the reported differences in the biochemical and catalytic behavior of these isozymes, recent publications from the Raven group raised concerns regarding this long-standing assumption.47,48 The center of this controversy is whether the ternary complexes of the two isozymes take the same route to form a Compound II-like ferryl intermediate. In IDO, resonance Raman studies revealed that the Fe(II)−oxy moiety of the ternary complex exhibits spectroscopic features of a ferric superoxide species.52 Therefore, it is proposed that the terminal oxygen atom of heme-bound O2 initiates a direct radical addition to C2 or C3 of L-Trp without deprotonation of the indole moiety (route A in Scheme 1).52,54

Whether the same mechanism is employed by TDO remains unclear. A recent crystallographic study revealed the structure of the ternary complex of human TDO.53 Notably, the Fe−O− O bond angle of the heme-bound dioxygen moiety is determined to be ∼150°, significantly larger than that expected for a typical ferrous heme-bound neutral dioxygen.53 This observation indicated that the heme-bound O2 in human TDO adopts a superoxide configuration, similar to the scenario for IDO. Therefore, the catalytic mechanism of TDO is proposed to resemble that of IDO.53

An alternative mechanism, i.e., electrophilic addition to C2 or C3 of L-Trp (route B in Scheme 1), is also plausible for TDO,47,49 as supported by computational and experimental evidence from bacterial TDOs.48,50,51,55 These computational and experimental pieces of evidence cast doubt on the presumed mechanistic uniformity among TDOs from different sources.

To provide mechanistic insight into the catalytic reaction of TDO, we characterized the chemical properties of the ternary complex of Cupriavidus metallidurans TDO (cmTDO). We performed rapid kinetic studies to identify reactive intermediates formed during O2-dependent reactions of cmTDO. In combination with sequential mixing techniques, the chlorite dismutase (Cld)−chlorite system56 was employed to expand the upper limit of the O2 concentration in solution. The kinetic information obtained from these studies was then used to guide the rapid freeze-quench (RFQ) spectroscopic characterization of the reactive intermediates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

L-Trp (99%) and sodium chlorite (80%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 57Fe-enriched iron(III) oxide (95% enriched) was purchased from Science Engineering and Education Co. (Edina, MN). The iron(III) oxide powder was dissolved in 37% hydrochloric acid while being heated. Excess hydrochloric acid was neutralized via incremental additions of a 1 M NaOH solution. The resulting 57Fe(III) solution (bright yellow color) was degassed and converted to a 57Fe(II) solution (colorless) via incremental additions of a 100 mM sodium ascorbate solution under anaerobic conditions.

Protein Preparation

The methods for plasmid construction and overexpression of His-tagged full-length cmTDO were reported previously.57,58 The cmTDO protein was purified using a Ni-NTA affinity column on an ÄKTA FPLC system, followed by a Sephadex G-25 gel filtration column for the purpose of salt removal and buffer exchange. Ferrous cmTDO was prepared by dithionite reduction of the ferric enzyme under anaerobic conditions. 57Fe-enriched cmTDO was obtained by overexpressing cmTDO in a metal-depleted LB medium supplemented with 57Fe(II).57,59 Spectroscopic characterization and kinetic analysis of cmTDO were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer with 10% (w/w) glycerol (pH 7.4). The overexpression plasmid of Dechloromonas aromatica Cld was a gift from J. M. Bollinger (The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA) and J. Dubois (Montana State University, Bozeman, MT). Cld catalyzes the degradation of chlorite, generating O2 as a product. Previous studies showed that the Cld−chlorite system can achieve in situ evolution of a >5 mM “pulse” of O2 within 1 ms at the easily accessible Cld concentration of 50 μM.56

Rapid Kinetic Studies

Transient kinetics of TDO measurements were performed at 4 °C using an Applied Photophysics (Leatherhead, U.K.) SX20 stopped-flow spectrometer equipped with a photodiode array detector. The sample handling unit of the SX20 spectrometer was housed in an anaerobic chamber from COY Laboratory Products (Grass Lake, MI). The experimental data were analyzed by the ProK software package obtained from Applied Photophysics.

RFQ Sample Preparation

RFQ−Mössbauer samples were prepared using an Update Instruments (Madison, WI) model 1000 chemical/freeze-quench apparatus. The reservoirs of the reagents were submerged in a cold water bath with an ice slurry. After being rapidly mixed, the reaction mixture was sprayed and frozen in cold liquid ethane (approximately −130 °C) or isopentane (approximately −140 °C) at different time points. The samples were further packed into Mössbauer cups in a custom isopentane bath maintained at approximately −120 °C. Excess liquid ethane or isopentane was vacuumed off after sample packing. The RFQ−Mössbauer samples were stored in a liquid nitrogen dewar before spectroscopic analysis.

Mössbauer Spectroscopy

57Fe Mössbauer spectra were recorded with a Janis Research dewar operating at temperatures between 4.2 and 100 K in a constant acceleration mode in transmission geometry. The experimental data were analyzed using the software SpinCount (written by M.P.H.). Isomer shifts are reported relative to Fe metal at 298 K.

Steady-State Kinetic Assays

Steady-state kinetic assays were performed as described previously.58 The catalytic activity of cmTDO was determined at a saturating amount (i.e., 2 mM) of L-Trp and (indole-d5)-L-Trp to determine the kinetic isotope effect.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Stopped-Flow Ultraviolet−Visible (UV−vis) Study in the Absence of L-Trp

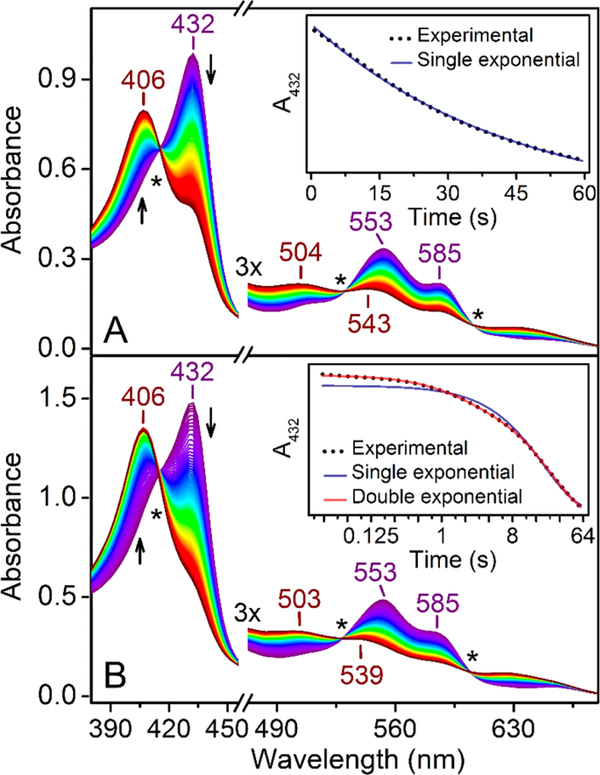

Figure 1A shows the time-resolved UV−vis spectra of ferrous cmTDO upon stopped-flow mixing with an O2-saturated buffered solution. The observation of isosbestic points at 415, 531, and 607 nm (marked with asterisks in the figure) suggests a single-phase transition from ferrous TDO (Soret band at 432 nm; visible bands at 553 and 585 nm) to ferric TDO (Soret band at 406 nm; visible bands at 504 and 543 nm). It is evident that no oxy−ferrous species accumulated during this process. Kinetic analysis of the spectral change at 432 nm reveals that the experimental data can be satisfactorily fit by a single-exponential equation, yielding an apparent rate constant of 0.023 ± 0.001 s−1 (Figure 1A, inset). These observations are consistent with previous reports on TDOs from other bacteria, such as Pseudomonas fluorescens TDO (pfTDO) and Xanthomonas campestris TDO (xcTDO), which demonstrated that in the absence of L-Trp, the ferrous heme does not form a stable adduct with O2.48,60

Figure 1.

Time-resolved (0−60 s) UV−vis spectra of ferrous cmTDO upon stopped-flow mixing with O2. (A) For the single-mixing stopped-flow experiment, an O2-saturated solution was mixed with an anaerobic ferrous cmTDO solution. The concentration of TDO after mixing was 15 μM. (B) For the sequential-mixing stopped-flow experiment, in the first mix, Cld (5 μM) was combined with chlorite (20 mM) to generate a burst of O2 at 10 mM; in the second mix, the O2-enriched solution was combined with an anaerobic ferrous TDO solution. There was a 50 ms delay between the first mix and the second mix to ensure a complete production of O2 from chlorite. The data were collected immediately after the second mix. The concentration of TDO after mixing was 100 μM, and the concentration of O2 in the final reaction mixture was 5 mM. Notably, the concentration of TDO was increased compared to that of the single-mixing experiment to minimize the spectral contribution from Cld, which also contains heme. In panel B, the light path of the stopped-flow UV−vis measurement was reduced from 10 to 2 mm to maintain linearity of detector response. In both sets of plots, the arrows indicate the trends of the changes in the spectra, and the asterisks indicate the isosbestic points (i.e., 415, 531, and 607 nm) identified on the spectra. The insets show the time-resolved absorption change at 432 nm and corresponding exponential fittings. The X-axis of the inset of panel B is plotted on a log 2 scale for a better comparison between the two fitting results.

Notably, under similar reaction conditions, the formation of an oxy−ferrous species was captured in both human IDO and human TDO.48,52 This comparison not only reveals differences in the reactivity of the heme moiety between TDO and IDO but also underlines important variations in the chemical properties between bacterial TDOs and human TDO despite the high degree of structural similarity of their active sites.

Next, we studied the reaction between ferrous TDO and O2 at an elevated O2 concentration by employing the Cld− chlorite system. Previous work from the Bollinger group demonstrated that this means of in situ O2 evolution allows for a >5 mM “pulse” of O2 to be generated in a very short period of time (i.e., within a number of milliseconds).56 Figure 1B shows the time-resolved UV−vis spectra of a sequential-mixing stopped-flow experiment involving the Cld−chlorite system. First, Cld was mixed with chlorite to generate an O2-enriched solution; after a 50 ms delay, this O2-enriched solution was mixed with an anaerobic solution containing ferrous cmTDO. The concentration of O2 in the final reaction mixture was 5 mM. The spectral changes caused by the reaction between ferrous cmTDO and 5 mM O2 strongly resemble those observed in Figure 1A and show a more rapid and complete conversion from ferrous to ferric TDO. There seems to be no noticeable spectral evidence for the accumulation of an oxy− ferrous species.

Interestingly, the time-resolved absorbance change at 432 nm cannot be satisfactorily fit by a single-exponential equation; a double-exponential function is required (Figure 1B, inset). The corresponding apparent rate constants of the double-exponential fitting were determined to be 0.66 ± 0.01 and 0.040 ± 0.001 s−1. On the basis of the isosbestic points shown in Figure 1B, we postulate that the double-exponential kinetics does not involve an intermediate and thus does not result from a biphasic sequential reaction model; instead, it is most likely caused by the heterogeneity of the heme cofactor in cmTDO. X-ray crystallographic studies showed that TDO adopts a “dimer of dimers” quaternary structure.31,32 Quantitative electron paramagnetic resonance and Mössbauer spectroscopic characterizations revealed the presence of two inequivalent heme species in both the Fe(II) and Fe(III) states of cmTDO, consistent with the “dimer of dimers” quaternary structure that dictates the electronic properties of the heme cofactor.59 Therefore, the double-exponential kinetics observed in this study may correspond to two distinct Fe(II)-to-Fe(III) transition processes originating from the heterogeneity of the heme cofactor. It is not clear why such a phenomenon was not observed at a lower O2 concentration. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular basis for the different reactivities of the two inequivalent hemes toward molecular oxygen.

Stopped-Flow UV−vis Study in the Presence of L-Trp

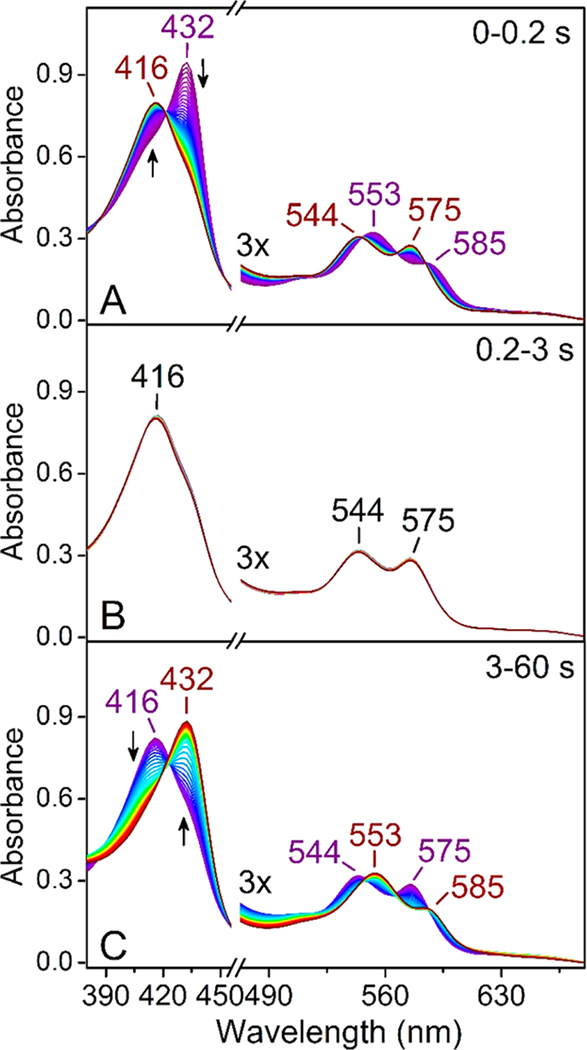

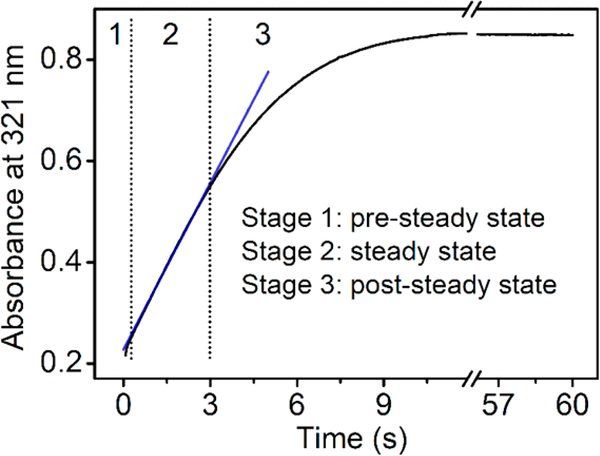

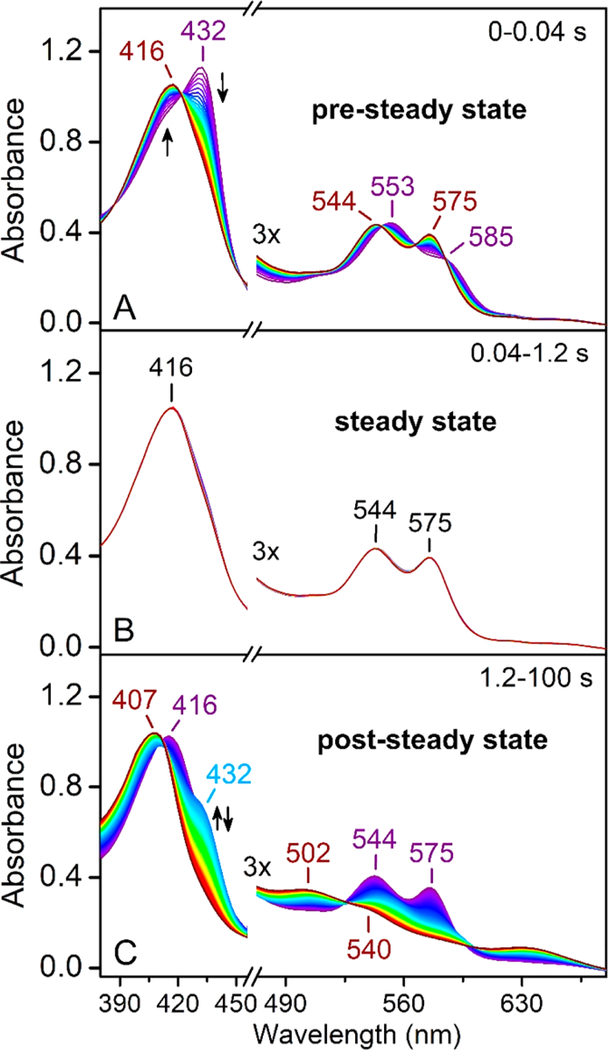

The catalytic event of ferrous cmTDO in the presence of L-Trp and O2 was characterized by stopped-flow UV−vis spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 2, the course of the catalytic event can be divided into three distinct stages. Upon rapid mixing of ferrous cmTDO and a solution containing both substrates, a catalytic intermediate with a Soret band at 416 nm was formed within 0.2 s (Figure 2A). This intermediate was assigned as the catalytic ternary complex of cmTDO based on the similarity of its spectral characteristics to those of the ternary complexes captured in other TDOs.48,52,60 In the next stage (0.2−3 s), the UV−vis spectra remained unaltered (Figure 2B), suggesting that a steady state was established in the reaction system. During this stage, Michaelis−Menten kinetics was observed, as indicated by the linear plot of product formation at 321 nm (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Time-resolved (0−60 s) UV−vis spectra of ferrous cmTDO upon stopped-flow mixing with an O2-saturated solution containing L-Trp. The final concentration of TDO after mixing was 15 μM. The final concentration of L-Trp was 2.5 mM. The final concentration of O2 in the reaction mixture was ∼1 mM. The time course of the reaction can be divided into three distinct stages: (A) 0−0.2 s, (B) 0.2−3 s, and (C) 3−60 s. The arrows indicate the trends of the changes in the spectra.

Figure 3.

Time-resolved (0−60 s) change in the optical absorbance at 321 nm. The blue line is a linear fit of the experimental data during the steady state (0.2−3 s) of the reaction. See the legend of Figure 2 for experimental details.

In the last stage (3−60 s), a transition from the ternary complex to ferrous TDO occurred (Figure 2C). This transition was triggered by a disruption of the steady state in the reaction system, due to product inhibition known for TDO,61 which slowed the reaction when the concentration of the product increased in the reaction system (Figure 3). The mechanism of product inhibition in cmTDO remains unclear and requires further study. We postulate that the product NFK may bind at a site different from the active site and regulate the catalytic activity of cmTDO allosterically.

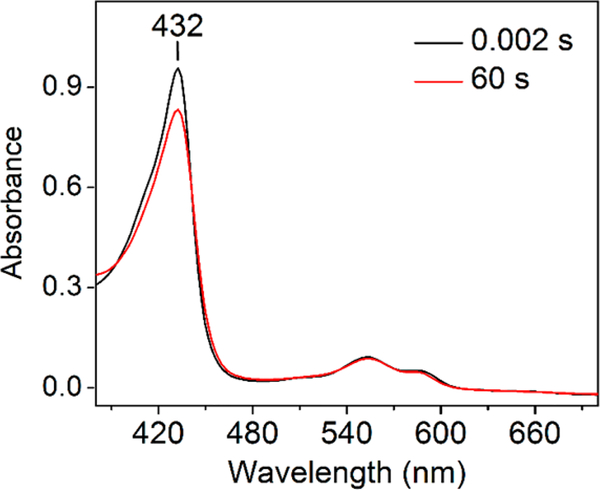

Notably, the stopped-flow UV−vis spectrum of the ferrous TDO species at the very beginning of the reaction (t = 0.002 s) is slightly different from the spectrum of the ferrous TDO species at the end of the reaction (t = 60 s). The former exhibited a higher extinction coefficient of the heme Soret band at 432 nm (Figure 4). The observed spectral variance originated from a difference in the chemical identities of these two ferrous species. The ferrous species at the beginning of the reaction was primarily substrate-free, whereas the ferrous species at the end of the reaction was bound with L-Trp. Our previous work showed that the binding of L-Trp to cmTDO induces a decrease in the extinction coefficient of the heme Soret band.58 The substrate-bound ferrous species at the end of the reaction was catalytically unproductive as a result of the binding of the product NFK. This is evident from Figure 3, which shows that the catalytic reaction was completely halted at 60 s, due to product inhibition.

Figure 4.

Spectral comparison between two ferrous TDO species captured in the stopped-flow reaction of cmTDO. See the legend of Figure 2 for experimental details.

Subsequently, we studied the dioxygenation reaction at an elevated O2 concentration. Figure 5 shows the time-resolved UV−vis spectra of cmTDO in a sequential-mixing stopped-flow experiment. First, Cld was mixed with a buffered solution containing chlorite and L-Trp to generate an O2-enriched solution; after a 50 ms delay, this O2-enriched solution containing L-Trp was mixed with an anaerobic solution of ferrous cmTDO. The concentration of O2 in the final reaction mixture was 5 mM. As shown in Figure 5, the course of the catalytic event can be divided into three distinct stages, similar to the results shown in Figure 2. The increase in the O2 concentration significantly shortened the duration of the pre-steady state from 0.2 to 0.04 s (Figure 5A). This observation suggests that the rate of formation of the catalytic ternary complex was dependent on the concentration of O2, consistent with previous studies of pfTDO.60 After the short pre-steady state, the reaction entered into the steady state with the ternary complex being the dominating species in the reaction system (Figure 5B). During this stage (0.04−1.2 s), the UV−vis spectra remained unperturbed. In the last stage of the reaction (1.2−100 s), the reaction shifted out of the steady state due to product inhibition, similar to the results observed in Figure 2C. In this stage, a gradual conversion of the ternary complex to ferrous cmTDO was observed (Figure 5C). The newly formed ferrous enzyme is believed to be catalytically unproductive, as previously discussed in Figure 2C. The newly formed ferrous enzyme was gradually oxidized to the ferric state after exposure to a very high concentration (∼5 mM) of O2 present in the reaction system (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Time-resolved (0−100 s) UV−vis spectra of cmTDO in a sequential-mixing stopped-flow experiment. In the first mix, Cld (5 μM) was combined with a buffered solution containing chlorite (20 mM) and L-Trp (10 mM) to generate a burst of O2 at 10 mM; in the second mix, the O2-enriched solution containing L-Trp was combined with an anaerobic ferrous TDO solution. There was a 50 ms delay between the first mix and the second mix to ensure a complete production of O2 from chlorite. Data collection was initiated immediately after the second mix. The final concentration of cmTDO after mixing was 15 μM. The final concentration of L-Trp was 2.5 mM. The final concentration of O2 was 5 mM. The time course of the reaction can be divided into three distinct stages: (A) 0−0.04 s, (B) 0.04−1.2 s, and (C) 1.2−100 s. The arrows indicate the trends of the changes in the spectra. Notably, the absorbance at 432 nm first increased but then decreased in panel C. A control experiment was performed to assess the spectral contribution of Cld. The control experiment used the same sequential-mixing setup as described above, but with the anaerobic ferrous cmTDO solution replaced by an anaerobic buffer. The time-resolved UV−vis spectra of the control experiment showed that the spectral contribution of Cld was minimal (Figure S1).

RFQ−Mössbauer Spectroscopic Characterization of the Catalytic Ternary Complex of cmTDO

Our stopped-flow results show that the ternary complex of cmTDO was the dominant species during the steady state of the catalytic reaction, revealing a wide time window for capturing this intermediate via RFQ techniques. The incorporation of the Cld−chlorite system allowed for the production of O2 at concentrations higher than the solubility of O2 (∼2 mM for an O2-saturated buffer),56 thereby generating excess O2.

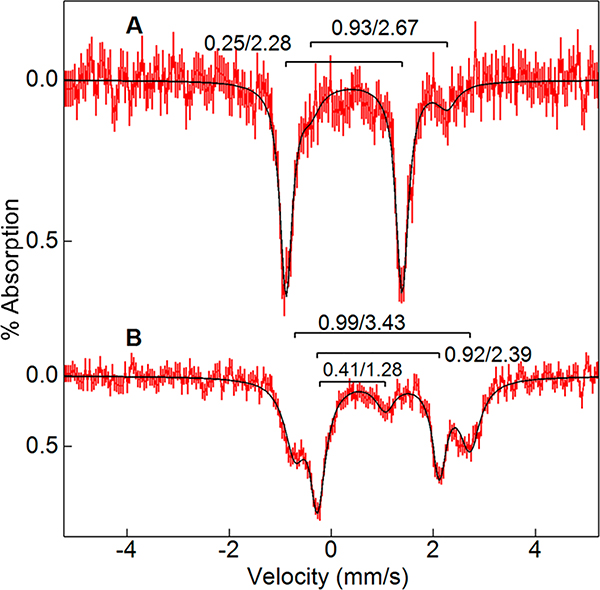

Our previous Mössbauer spectroscopic studies of ferrous cmTDO showed that there are two major heme species in approximately equal amounts.59 The two heme species represent a “dimer of dimer” quaternary structure of cmTDO. Figure 6 shows the representative Mössbauer spectra of a double-mixing RFQ experiment, which aimed to capture the ternary complex of cmTDO. Similar to the stopped-flow setup, a solution containing L-Trp and chlorite was mixed with an equal volume of a second solution containing Cld; after a 50 ms pause to ensure a complete production of O2 from chlorite, the mixture was further mixed with an anaerobic 57Fe-ferrous TDO solution and then freeze-quenched in liquid ethane. At a delay time of 40 ms after the second mix, the Mössbauer data recorded at 100 K showed a nearly quantitative conversion of ferrous heme to a single S = 0 species, which corresponds to the catalytic ternary complex. The Mössbauer spectrum of the 40 ms sample was fitted with parameters δ = 0.25 mm/s and ΔEQ = 2.28 mm/s (∼85% of Fe) for the S = 0 species (Figure 6A). A minor Fe(II) species [δ = 0.93 mm/s, and ΔEQ = 2.67 mm/s (∼15% of Fe)] was also present in the sample (Figure 6A). The parameters of the S = 0 species are similar to those of oxy−ferrous heme complexes characterized in other heme-dependent proteins. For example, the O2 adduct of myoglobin has values of δ = 0.27 mm/s and ΔEQ = 2.31 mm/s.62 The minor Fe(II) species in the RFQ−Mössbauer sample is assigned as the adduct of ferrous TDO and L-Trp at a spin state of S = 2, based on the similarity of its Mössbauer parameters to those reported for the adduct of ferrous TDO and L-Trp.59 Notably, the adduct of ferrous TDO and L-Trp is comprised of two inequivalent heme species with slightly different ΔEQ values, due to the “dimer of dimers” quaternary structure of cmTDO.59 These two inequivalent heme species were not resolved on the spectrum of this RFQ−Mössbauer sample due to their small amounts in the sample. Therefore, the parameters of the minor Fe(II) species shown in Figure 6A represent averages of the parameters of the two inequivalent heme species.

Figure 6.

Mössbauer spectra of 57Fe-enriched cmTDO in a sequential-mixing RFQ experiment. In the first mix, Cld (100 μM) was combined with a buffered solution containing chlorite (20 mM) and L-Trp (25 mM) in a 1:1 ratio to generate a burst of O2; in the second mix, the O2-enriched solution containing L-Trp was combined with an anaerobic 57Fe-enriched ferrous TDO solution (2.1 mM) in a 2:1 ratio. There was a 50 ms pause between the first mix and the second mix to ensure a complete production of O2 from chlorite. The reaction was quenched (A) 40 ms and (B) 7 s following the second mix. The final concentration of TDO after mixing is 0.7 mM. The final concentration of L-Trp is 8.3 mM. The final concentration of O2 is 6.7 mM. The Mössbauer data were collected at 100 K. The doublet parameters of the simulations are indicated as δ/ΔEQ, both in millimeters per second. The spectra are displayed for equal areas.

At a much longer delay time of 7 s, the S = 0 species vanished (Figure 6B). The spectrum of Fe(II) cmTDO bound with L-Trp returned with a minor amount of Fe(III) cmTDO (16%, δ = 0.41 mm/s, and ΔEQ = 1.28 mm/s). The Fe(II) cmTDO in this sample was composed of two species in equal amounts (42%, δ = 0.92 mm/s, and ΔEQ = 2.39 mm/s; 42%, δ = 0.99 mm/s, and ΔEQ = 3.43 mm/s), corresponding to the two inequivalent heme species for the adduct of ferrous TDO and L-Trp.59

Notably, the RFQ−Mössbauer experiments employed a concentration of cmTDO in the low millimolar range, much higher than that used in the stopped-flow UV−vis experiments. Therefore, the onset of product inhibition in the RFQ−Mössbauer experiments would occur at a much earlier time window, because a bolus of the product NFK can be generated within tens or hundreds of milliseconds at such a high enzyme concentration. Therefore, the substrate-bound Fe(II) species in Figure 6B was catalytically unproductive, due to the binding of the product NFK. Compared to the stopped-flow data shown in Figures 2C and 5C, the catalytically unproductive species in Figure 6B was generated within a much shorter time window. The rapid generation of this catalytically unproductive species was caused by the early onset of product inhibition in the RFQ−Mössbauer sample.

The origin of the Fe(III) species in Figure 6B is unknown. Because this species was not present in the RFQ−Mössbauer sample collected an earlier time point (i.e., 40 ms as shown in Figure 6A), we postulate that it is an oxidation product of ferrous TDO, generated due to (1) a halt of the catalytic reaction caused by product inhibition and (2) the high concentration of O2 in the reaction system.

The RFQ experiment was repeated except that 57Fe-ferrous TDO was combined with L-Trp under an anaerobic condition prior to being mixed with O2. The preformation of the binary complex of ferrous TDO and L-Trp in this set of RFQ samples can significantly accelerate the formation of the catalytic ternary complex. At delay times of 3, 40, and 250 ms, the same S = 0 species was again observed in a nearly quantitative yield (Figure S2).

These results demonstrate that both heme species in the “dimer of dimers” structure of cmTDO underwent reactions to generate the ternary complex. The electronic properties of the ternary complex of cmTDO are closely aligned with those of oxy-myoglobin. Notably, the electronic properties of oxymyoglobin can be described as an Fe(II) center having partial delocalization of the dπ electrons onto the oxygen.62 The iron− oxygen interaction is highly covalent, so the iron valence is neither 2 nor 3, which also means the oxy is neither truly O2 nor superoxo.

Kinetic Isotope Effect

The presence of the ternary complex as the dominant species during the steady state of cmTDO suggests that the decay of this reactive intermediate is the rate-limiting step of the catalytic reaction. To provide further experimental support for this finding, we studied the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) in cmTDO using (indole-d5)-L-Trp as the substrate. Our activity assays revealed a KIE value (kH/kD) of 0.87 ± 0.03 (Figure S3), which is much more significant than the value previously reported for rat TDO (i.e., 0.96).63

This observed KIE represents an inverse α-secondary KIE, which is a secondary KIE (2° KIE) where the isotopic substitution occurs α to the reaction site. The α−2° KIE involves a rate difference for isotopic substitution of a bond (denoted as the “isotopic bond”) that is not broken in the rate-determining step. The rate difference arises from a vibrational change on the isotopic bond caused by the chemical transition in the rate-determining step. The magnitude of the vibrational change is determined by the difference in the vibrational energy of the isotopic bond between the starting state and the transition state. In general, a lower vibration energy in the transition state compared to the starting state is expected to yield a normal kinetic isotope effect. In contrast, a higher vibrational energy in the transition state compared to the starting state is expected to yield an inverse kinetic isotope effect.64,65 An inverse α−2° KIE for a C−H bond (i.e., the carbon is the reaction site, and the isotopic substitution occurs at the hydrogen) is typically observed when the carbon atom in the C−H bond undergoes a hybridization change from sp2 to sp3 during the rate-determining step. The vibrational shift in the C−H bond caused by a hybridization change from sp2 to sp3 is dominated by the vibrational change in the out-of-plane bending mode. The wavenumber for the out-of-plane bending mode at the sp2 hybridization state (the starting state) (i.e., 800 cm−1) is lower than that at the sp3 hybridization state (the final state) (i.e., 1340 cm−1). The wavenumber for the out-of-plane bending mode in the transition state is typically located between those in the starting state and the final state and thus is higher than that in the starting state. Accordingly, the vibrational energy in the transition state is higher than that in the starting state, corresponding to an inverse kinetic isotope effect. The magnitude of an inverse α−2° KIE usually ranges from 0.8 to 0.9, depending upon the transition-state structure.66

Mechanistic Implications

An emerging body of evidence indicates that the assembly processes of the ternary complexes of TDO and IDO differ. IDO can use superoxide as a substrate, whereas TDO cannot.67 In TDO, especially bacterial TDOs, the binding of the primary substrate (L-Trp) is believed to precede the binding of the secondary substrate (O2).3 This notion was initially evidenced from a pioneering kinetic study by Hayaishi and co-workers.60 They showed that accumulation of the oxy−ferrous complex of pfTDO can be observed only in the presence of L-Trp, and that in the absence of L-Trp the ferrous heme does not readily bind O2. It is eventually oxidized to the ferric state by O2.60 The binding of oxygen with the ferrous heme in the presence of L-Trp was determined to be a reversible process, with the rates of forward and reverse reactions of oxygen binding determined to be 5 × 106 M−1 s−1 and 230 s−1, respectively.60 Recent spectroscopic studies of xcTDO also showed that binding of O2 to the ferrous heme occurs only in the presence of L-Trp.48 An induced-fit behavior occurs in TDO upon L-Trp binding, as revealed by the crystal structures of substrate-free and substrate-bound xcTDO32 as well as by a recent modeling study based on the crystal structure of Drosophila melanogaster TDO (dmTDO).23 L-Trp recognition can establish a complex and extensive network of substrate−enzyme interactions, which stabilizes the active-site region and completely shields it from the solvent by switching from an open conformation to a closed conformation through loop movements.32 Thus, the Trp−TDO binary complex represents an intermediate stage in the formation process of the ternary Michaelis complex of TDO. On the contrary, IDO is generally believed to bind O2 prior to L-Trp.68,69 Unlike TDO, IDO can form its oxy−ferrous adduct regardless of L-Trp.70 The rate constants for binding of O2 and CO to the heme center of ferrous IDO are not significantly perturbed by L-Trp.70 In addition, Yeh et al. showed that conversion of ferric IDO to the ferryl form via peroxide oxidation significantly facilitates L-Trp binding.71 Upon combination of this phenomenon with a previous observation that cyanide-bound ferric IDO has an affinity for L-Trp much higher than that of the ligand-free ferric enzyme,68,72 it is suggested that regardless of the heme redox state, ligand binding to the heme iron of IDO can introduce conformational changes that favor L-Trp binding.71 Moreover, since the early studies of IDO, inhibition of the dioxygenase activity at high L-Trp concentrations has been noted.24,73 A recent mechanistic study by Raven and colleagues on the substrate-inhibition effect revealed that this phenomenon can be ascribed to the sequential, ordered binding of O2 and L-Trp.69 At low concentrations of L-Trp, O2 binds first followed by the binding of L-Trp; at higher concentrations of L-Trp, the order of binding events is reversed, and L-Trp binding disfavors the subsequent O2 binding step, diminishing the catalytic activity.69 Overall, the proposed mechanisms of Michaelis complex assembly for TDO and IDO are in accordance with the results of steadystate kinetic studies. In TDO, the Km value of L-Trp is larger than the Kd value of L-Trp for the ligand-free ferrous enzyme.74 However, in IDO, the Km value of L-Trp is much smaller than the Kd value of L-Trp for the ligand-free ferrous enzyme, while the Km value of O2 is similar to the Kd value of O2 for the ligand-free ferrous enzyme.68,72,75

One exception among TDOs from different sources is human TDO. In contrast to TDOs from nonmammalian sources, an oxy−ferrous species was captured in human TDO in the absence of L-Trp.48,52 Moreover, the Km value of L-Trp in human TDO is much smaller than the Kd value of L-Trp for ligand-free ferrous human TDO,53 resembling the results from IDO instead of TDOs from nonmammalian sources. These comparisons reveal important variations in the chemical properties between human TDO and TDOs from nonmammalian sources. In terms of reactivity toward molecular oxygen, human TDO is more similar to IDO instead of TDOs from nonmammalian sources. The non-uniformity among TDOs from different sources appears to originate from subtle differences in their active-site structures. Recent crystallographic studies revealed that the orientation of the heme moiety and the positioning of specific loop structures in the active site of human TDO are slightly different from those of a bacterial TDO.53

As shown in Scheme 1, the ternary complex’s electronic structure is crucial for determining whether the catalytic pathway proceeds via electrophilic addition or superoxide attack. However, heme Fe−O2 bonding is a remarkably complex matter, and its nature has been a subject of active debate for decades on the extensively investigated model system, oxy-myoglobin/hemoglobin, in the field of bioinorganic and biophysical chemistry.76 The electronic structure of the ternary complex of TDO can be theoretically described in the following configurations: ferrous−oxy [Fe2+(S = 0)−O2(S = 0)], ferric−superoxide [Fe3+(S = 1/2)−O2−(S = 1/2)], a ferrous center antiferromagnetically coupled to 3O2 in a threecenter, four-electron bond, affording the [Fe2+(S = 1)−O2(S = 1)] species, and finally a multiconfigurational model that mixes all three other possibilities. The molecular mechanism for binding of O2 to myoglobin/hemoglobin has been extensively studied by Mössbauer spectroscopy, resonance Raman spectroscopy, nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), DFT and QM/MM calculations, and X-ray crystallography, yet there is still no consensus regarding the nature of Fe−O2 bonding.77 Our understanding leaned heavily on a recent observation of an electronic configuration shift of the Fe−O2 bonding in oxyhemoglobin through XAS investigation,78 which lends strong support to the multiconfigurational model.1,78 The contribution of the local environment to the bonding nature has also been demonstrated in model complex studies.79 Thus, the oxidation state of the heme iron in the ternary complex of cmTDO would not be a clean ferrous or ferric state. Likewise, the oxygen is neither truly O2 nor superoxo. An added complication is that the biological origin of the proteins could also have a discernible impact on the multiconfigurational character of the heme Fe−O2 bond in their respective oxy complexes.

Our stopped-flow UV−vis spectroscopic results with cmTDO demonstrate that an oxy−ferrous complex of cmTDO can be observed only when L-Trp is present, consistent with previous studies of other bacterial TDOs. On the basis of the RFQ−Mössbauer results of the ternary complex of cmTDO and the current understanding of the nature of heme Fe−O2 bonding, we propose that an electrophilic addition (route B of Scheme 1), rather than a direct radical addition (route A of Scheme 1), to the indole moiety of L-Trp is involved in the catalytic mechanism of cmTDO. It is postulated that such a catalytic mechanism may be applicable to other bacterial TDOs. Human TDO, however, may adopt a catalytic mechanism resembling that of IDO, which involves a direct radical addition to the indole moiety of L-Trp.53 This notion is consistent with a recent study in another bacterial TDO, Pseudomonas TDO (paTDO), which employed a heme-modification approach that introduces different substituents on the heme cofactor of paTDO.55 The work on paTDO suggests that the initial step of the dioxygen activation by paTDO is a direct electrophilic addition of the heme-bound O2 to the indole ring of L-Trp.

As shown in Scheme 1, the chemical step following the formation of the ternary complex of TDO comprises an sp2-tosp3 transition for C2 or C3 in the indole ring of L-Trp. Notably, this is the only chemical step that involves a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3. In view of the stopped-flow UV− vis spectroscopic results, the formation of a covalent bond between the terminal oxygen atom of O2 and the indole ring of L-Trp is the rate-limiting step of the dioxygenase reaction of cmTDO. In L-Trp, the only C−H bond that experiences a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 is the C−H bond at C2. We postulate that an electrophilic attack at C2, instead of C3, by the terminal oxygen atom of O2 occurs and results in the observed inverse α−2° KIE.

It is noteworthy that the kinetics and spectroscopic data described in this work provide support to the proposed route B but cannot definitively define the nature of the ternary complex. A more convincing conclusion about the mechanism will be drawn through capturing and characterizing additional reactive intermediates, such as the proposed carbocationic intermediate. This goal might be achieved by altering the kinetics in the crystalline lattice or through the use of carefully designed substrate analogues, which have strategically placed electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups to either disfavor or favor the hypothetical carbocationic structure drawn in our proposed mechanism (Scheme 2). Unfortunately, TDO is known to have a very low tolerance for substrate analogues due to a tight fitting of its substrate in the active site.49 The substrate specificity is one of the most prominent different behaviors between IDO and TDO. Introducing different substitution groups onto L-Trp may cause a cascade of disruptions of the catalytic event of TDO. These challenges must be mitigated in future studies.

Scheme 2.

Proposed Catalytic Mechanisms of cmTDO

CONCLUSIONS

This work describes the first Mössbauer characterization of the catalytic intermediate identified in the progression of the stopped-flow reaction of TDO. The results provide an important piece of spectroscopic evidence of the chemical identity of the ternary complex of cmTDO and shed light on the catalytic mechanism of heme-dependent dioxygenases. On the basis of the discussions, a catalytic mechanism for bacterial TDO is proposed (Scheme 2). This catalytic mechanism features electrophilic addition to C2 of L-Trp by the terminal oxygen atom of O2. This work also highlights the differences in the reactivity of the heme moiety between TDO and IDO as well as between bacterial TDOs and human TDO, despite the high degree of structural similarity in their catalytic active sites.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ian Davis for helpful discussions throughout this work, and Drs. J. Martin Bollinger and Jennifer Dubois for providing the expression system of Cld.

Funding

This work was supported in whole, or part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants GM077387 (to M.P.H.) and GM108988 (to A.L.) and National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0843537 (to A.L.). J.G. acknowledges the Molecular Basis of Disease graduate fellowship from Georgia State University as well as the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship. K.D. acknowledges fellowship support from the Southern Regional Education Board. A.L. recognizes the Lutcher Brown Endowment Fund for research support.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TDO

tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- L-Trp

L-tryptophan

- NFK

N-formylkynurenine

- cmTDO

C. metallidurans TDO

- pfTDO

P. fluorescens TDO

- xcTDO

X. campestris TDO

- dmTDO

D. melanogaster TDO

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00179.

Figures S1−S3 (PDF)

Accession Codes

Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase from C. metallidurans, UniProtKB Q1LK00.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00179

Contributor Information

Jiafeng Geng, Department of Chemistry, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia 30303, United States.

Andrew C. Weitz, Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, United States.

Kednerlin Dornevil, Department of Chemistry, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia 30303, United States; Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas 78249, United States.

Michael P. Hendrich, Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, United States.

Aimin Liu, Department of Chemistry, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia 30303, United States; Department of Chemistry, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas 78249, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Huang X, and Groves JT (2018) Oxygen activation and radical transformations in heme proteins and metalloporphyrins. Chem. Rev 118, 2491–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Poulos TL (2014) Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev 114, 3919–3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sono M, Roach MP, Coulter ED, and Dawson JH (1996) Heme-containing oxygenases. Chem. Rev 96, 2841–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kal S, and Que L (2017) Dioxygen activation by nonheme iron enzymes with the 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad that generate high-valent oxoiron oxidants. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 22, 339–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wang Y, Li J, and Liu A (2017) Oxygen activation by mononuclear nonheme iron dioxygenases involved in the degradation of aromatics. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 22, 395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Maroney MJ, and Ciurli S (2014) Nonredox nickel enzymes. Chem. Rev 114, 4206–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Fetzner S (2012) Ring-cleaving dioxygenases with a cupin fold. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 78, 2505–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kovaleva EG, and Lipscomb JD (2008) Versatility of biological non-heme Fe(II) centers in oxygen activation reactions. Nat. Chem. Biol 4, 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Que L Jr., and Ho RY (1996) Dioxygen activation by enzymes with mononuclear non-heme iron active sites. Chem. Rev 96, 2607–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kotake Y, and Masayama I (1936) The intermediary metabolism of tryptophan. XVIII. The mechanism of formation of kynurenine from tryptophan. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem 243, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hayaishi O, Rothberg S, Mehler AH, and Saito Y (1957) Studies on oxygenases; enzymatic formation of kynurenine from tryptophan. J. Biol. Chem 229, 889–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tanaka T, and Knox WE (1959) The nature and mechanism of the tryptophan pyrrolase (peroxidase-oxidase) reaction of Pseudomonas and rat liver. J. Biol. Chem 234, 1162–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Stone TW, and Darlington LG (2002) Endogenous kynurenines as targets for drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 1, 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Schwarcz R (2004) The kynurenine pathway of tryptophan degradation as a drug target. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 4, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Guillemin GJ, Meininger V, and Brew BJ (2006) Implications for the kynurenine pathway and quinolinic acid in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener. Dis 2, 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Guillemin GJ, and Brew BJ (2002) Implications of the kynurenine pathway and quinolinic acid in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Rep. 7, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Knox WE, Yip A, and Reshef L (1970) L-tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (tryptophan pyrrolase). Methods Enzymol. 17, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Knox WE, and Mehler AH (1950) The conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine in liver. I. The coupled tryptophan peroxidase-oxidase system forming formylkynurenine. J. Biol. Chem 187, 419–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kurnasov O, Goral V, Colabroy K, Gerdes S, Anantha S, Osterman A, and Begley TP (2003) NAD biosynthesis: identification of the tryptophan to quinolinate pathway in bacteria. Chem. Biol 10, 1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Magni G, Amici A, Emanuelli M, Raffaelli N, and Ruggieri S (2006) Enzymology of NAD+ synthesis. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol 73, 135–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Paglino A, Lombardo F, Arca B, Rizzi M, and Rossi F (2008) Purification and biochemical characterization of a recombinant Anopheles gambiae tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase expressed in Escherichia coli. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 38, 871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Colabroy KL, and Begley TP (2005) Tryptophan catabolism: identification and characterization of a new degradative pathway. J. Bacteriol 187, 7866–7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Huang W, Gong Z, Li J, and Ding JP (2013) Crystal structure of Drosophila melanogaster tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase reveals insights into substrate recognition and catalytic mechanism. J. Struct. Biol 181, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yamamoto S, and Hayaishi O (1967) Tryptophan pyrrolase of rabbit intestine. D- and L-tryptophan-cleaving enzyme or enzymes. J. Biol. Chem 242, 5260–5266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Higuchi K, and Hayaishi O (1967) Enzymic formation of Dkynurenine from D-tryptophan. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 120, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hirata F, and Hayaishi O (1972) New degradative routes of 5-hydroxytryptophan and serotonin by intestinal tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 47, 1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Shimizu T, Nomiyama S, Hirata F, and Hayaishi O (1978) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem 253, 4700–4706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Hayaishi O (1976) Properties and function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biochem 79, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Takikawa O (2005) Biochemical and medical aspects of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-initiated L-tryptophan metabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 338, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Sugimoto H, Oda S, Otsuki T, Hino T, Yoshida T, and Shiro Y (2006) Crystal structure of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: catalytic mechanism of O2 incorporation by a hemecontaining dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 2611–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhang Y, Kang SA, Mukherjee T, Bale S, Crane BR, Begley TP, and Ealick SE (2007) Crystal structure and mechanism of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, a heme enzyme involved in tryptophan catabolism and in quinolinate biosynthesis. Biochemistry 46, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Forouhar F, Anderson JL, Mowat CG, Vorobiev SM, Hussain A, Abashidze M, Bruckmann C, Thackray SJ, Seetharaman J, Tucker T, Xiao R, Ma LC, Zhao L, Acton TB, Montelione GT, Chapman SK, and Tong L (2007) Molecular insights into substrate recognition and catalysis by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 473–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Platten M, von Knebel Doeberitz N, Oezen I, Wick W, and Ochs K (2015) Cancer immunotherapy by targeting IDO1/TDO and their downstream effectors. Front. Immunol 5, 673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Prendergast GC, Malachowski WJ, Mondal A, Scherle P, and Muller AJ (2018) IDO/TDO Inhibition in Cancer In Oncoimmunology: A Practical Guide for Cancer Immunotherapy (Zitvogel L, and Kroemer G, Eds.) pp 289–307, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Muller AJ, and Prendergast GC (2007) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in immune suppression and cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Mellor AL, and Munn DH (2004) IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 762–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Munn DH, and Mellor AL (2007) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J. Clin. Invest 117, 1147–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mellor AL, and Munn DH (2001) Extinguishing maternal immune responses during pregnancy: implications for immunosuppression. Semin. Immunol 13, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Grohmann U, Fallarino F, and Puccetti P (2003) Tolerance, DCs and tryptophan: much ado about IDO. Trends Immunol. 24, 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Platten M, Wick W, and Van den Eynde BJ (2012) Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res. 72, 5435–5440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lob S, Konigsrainer A, Rammensee HG, Opelz G, and Terness P (2009) Inhibitors of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase for cancer therapy: can we see the wood for the trees? Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).King NJC, and Thomas SR (2007) Molecules in focus: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 39, 2167–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Katz JB, Muller AJ, and Prendergast GC (2008) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in T-cell tolerance and tumoral immune escape. Immunol. Rev 222, 206–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ, and Ruas JL (2017) Kynurenines: Tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science 357, eaaf9794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Pilotte L, Larrieu P, Stroobant V, Colau D, Dolusic E, Frederick R, De Plaen E, Uyttenhove C, Wouters J, Masereel B, and Van den Eynde BJ (2012) Reversal of tumoral immune resistance by inhibition of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 2497–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Shin I, Ambler BR, Wherritt D, Griffith WP, Maldonado AC, Altman RA, and Liu A (2018) Stepwise O-atom transfer in heme-based tryptophan dioxygenase: Role of substrate ammonium in epoxide ring opening. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 4372–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Raven EL (2017) A short history of heme dioxygenases: rise, fall and rise again. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 22, 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Basran J, Booth ES, Lee M, Handa S, and Raven EL (2016) Analysis of reaction intermediates in tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase: a comparison with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry 55, 6743–6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Geng J, and Liu A (2014) Heme-dependent dioxygenases in tryptophan oxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 544, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Chung LW, Li X, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, and Morokuma K (2008) Density functional theory study on a missing piece in understanding of heme chemistry: the reaction mechanism for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 12299–12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Chung LW, Li X, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, and Morokuma K (2010) ONIOM study on a missing piece in our understanding of heme chemistry: bacterial tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase with dual oxidants. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 11993–12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lewis-Ballester A, Batabyal D, Egawa T, Lu C, Lin Y, Marti MA, Capece L, Estrin DA, and Yeh SR (2009) Evidence for a ferryl intermediate in a heme-based dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 17371–17376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Lewis-Ballester A, Forouhar F, Kim SM, Lew S, Wang Y, Karkashon S, Seetharaman J, Batabyal D, Chiang BY, Hussain M, Correia MA, Yeh SR, and Tong L (2016) Molecular basis for catalysis and substrate-mediated cellular stabilization of human tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Sci. Rep 6, 35169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Capece L, Lewis-Ballester A, Yeh SR, Estrin DA, and Marti MA (2012) Complete reaction mechanism of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase as revealed by QM/MM simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 1401–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Makino R, Obayashi E, Hori H, Iizuka T, Mashima K, Shiro Y, and Ishimura Y (2015) Initial O2 insertion step of the tryptophan dioxygenase reaction proposed by a heme-modification study. Biochemistry 54, 3604–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Dassama LMK, Yosca TH, Conner DA, Lee MH, Blanc B, Streit BR, Green MT, DuBois JL, Krebs C, and Bollinger JM (2012) O2-evolving chlorite dismutase as a tool for studying O2-utilizing enzymes. Biochemistry 51, 1607–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Fu R, Gupta R, Geng J, Dornevil K, Wang S, Zhang Y, Hendrich MP, and Liu A (2011) Enzyme reactivation by hydrogen peroxide in heme-based tryptophan dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 286, 26541–26554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Geng J, Dornevil K, and Liu A (2012) Chemical rescue of the distal histidine mutants of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 12209–12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Gupta R, Fu R, Liu AM, and Hendrich MP (2010) EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopy show inequivalent hemes in tryptophan dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 1098–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Ishimura Y, Nozaki M, and Hayaishi O (1970) The oxygenated form of L-tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase as reaction intermediate. J. Biol. Chem 245, 3593–3602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Cho-Chung YS, and Pitot HC (1967) Feedback control of rat liver tryptophan pyrrolase. I. End-product inhibition of tryptophan pyrrolase activity. J. Biol. Chem 242, 1192–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Debrunner PG (1989) Mössbauer spectroscopy of iron porphyrins In Iron Porphyrins, Physical Bioinorganic Chemistry Series (Lever ABP, and Gray HB, Eds.) pp 137–234, VCH Publishers, Inc., New York. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Leeds JM, Brown PJ, Mcgeehan GM, Brown FK, and Wiseman JS (1993) Isotope effects and alternative substrate reactivities for tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 268, 17781–17786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Westaway KC (2006) Using kinetic isotope effects to determine the structure of the transition states of SN2 reactions. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem 41, 217–273. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Simmons EM, and Hartwig JF (2012) On the interpretation of deuterium kinetic isotope effects in C-H bond functionalizations by transition-metal complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 51, 3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Anslyn EV, and Dougherty DA (2006) Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, University Science Books, Sausalito, CA. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Ohnishi T, Hirata F, and Hayaish O (1977) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Potassium superoxide as substrate. J. Biol. Chem 252, 4643–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Lu CY, Lin Y, and Yeh SR (2010) Spectroscopic studies of ligand and substrate binding to human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry 49, 5028–5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Efimov I, Basran J, Sun X, Chauhan N, Chapman SK, Mowat CG, and Raven EL (2012) The mechanism of substrate inhibition in human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 3034–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Taniguchi T, Sono M, Hirata F, Hayaishi O, Tamura M, Hayashi K, Iizuka T, and Ishimura Y (1979) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Kinetic studies on the binding of superoxide anion and molecular oxygen to enzyme. J. Biol. Chem 254, 3288–3294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Lu CY, and Yeh SR (2011) Ferryl derivatives of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 286, 21220–21230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Lu CY, Lin Y, and Yeh SR (2009) Inhibitory substrate binding site of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 12866–12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Sono M, Taniguchi T, Watanabe Y, and Hayaishi O (1980) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Equilibrium studies of the tryptophan binding to the ferric, ferrous, and CO-bound enzymes. J. Biol. Chem 255, 1339–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Thackray SJ, Bruckmann C, Anderson JLR, Campbell LP, Xiao R, Zhao L, Mowat CG, Forouhar F, Tong L, and Chapman SK (2008) Histidine 55 of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase is not an active site base but regulates catalysis by controlling substrate binding. Biochemistry 47, 10677–10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Chauhan N, Basran J, Efimov I, Svistunenko DA, Seward HE, Moody PC, and Raven EL (2008) The role of serine 167 in human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: a comparison with tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry 47, 4761–4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Ohta T, Shibata T, Kobayashi Y, Yoda Y, Ogura T, Neya S, Suzuki A, Seto M, and Yamamoto Y (2018) A nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopic study of oxy myoglobins reconstituted with chemically modified heme cofactors: Insights into the Fe−O2 bonding and internal dynamics of the protein. Biochemistry 57, 6649–6652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Chen H, Ikeda-Saito M, and Shaik S (2008) Nature of the Fe−O2 bonding in oxy-myoglobin: Effect of the protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 14778–14790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Wilson SA, Green E, Mathews II, Benfatto M, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, and Sarangi R (2013) X-ray absorption spectroscopic investigation of the electronic structure differences in solution and crystalline oxyhemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110, 16333–16338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Wilson SA, Kroll T, Decreau RA, Hocking RK, Lundberg M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, and Solomon EI (2013) Iron L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy of oxy-picket fence porphyrin: experimental insight into Fe-O2 bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 1124–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.