Abstract

Introduction

Diverse sex development (dsd) is an umbrella term for different congenital conditions with incongruence of chromosomal, gonadal, and phenotypic sex characteristics. These are accompanied by various uncertainties concerning health-related, medical, psychosocial, and legal issues that raise controversial discussion.

Aim

The aim of this exploratory study was to investigate 3 questions: What are the most controversial and disputed issues in the context of intersex/dsd? Which issues are associated with the biggest knowledge gaps? Which issues involve the greatest difficulty or uncertainty in decision-making? A further aim was to investigate whether the group of persons concerned, the parents of intersex children, and the group of experts in the field had differing views regarding these questions.

Methods

A self-developed questionnaire was distributed among persons concerned, parents of children with intersex/dsd, and experts in the field. It contained open and multiple-choice questions. The answers from 29 participants were entered into data analysis. A mixed-method approach was applied. Quantitative data were analysed descriptively. Qualitative data were analysed according to the principles of qualitative content analysis.

Main Outcome Measure

Participants answered questions on the most controversial and disputed issues, issues associated with the biggest knowledge gaps, and issues associated with the most difficulty or uncertainty in decision-making.

Results

The findings indicate that controversial issues and uncertainties mainly revolve around surgical interventions but also around the question of how to adequately consider the consent of minors and how to deal with intersex in the family. Significant differences were found between persons concerned and parents vs academic experts in the field regarding the perceptions of procedure of diagnostic investigation and/or treatment in adulthood, on legal questions concerning marriage/registered civil partnerships, and on lack of psychosocial counseling close to place of residence.

Conclusion

The necessity of irreversible gonadal and genital surgery in early childhood is still a matter of strong controversy. To ensure the improvement in well-being of intersex persons, including a sexual health perspective, the positive acceptance of bodily variance is an important prerequisite. Psychosocial support regarding one-time decisions as well as ongoing and changing issues of everyday life appears to be an important means in reaching overall quality of life.

Lampalzer U, Briken P, Schweizer K. Dealing With Uncertainty and Lack of Knowledge in Diverse Sex Development: Controversies on Early Surgery and Questions of Consent—A Pilot Study. Sex Med 2020;8:472–489.

Key Words: Ambiguous Genitalia, Disorders of Sex Development (DSD), Diverse Sex Development (dsd), Genital Surgery, Health Care, Intersex, Surgery

Introduction

Congenital conditions with chromosomal, gonadal, hormonal, or genital characteristics that “do not correspond to the given standard for male or female categories of sexual or reproductive anatomy”1 are medically referred to as disorders of sex development, an umbrella term introduced in 2005 at the International Consensus Conference on Intersex in Chicago.2 As this term is highly controversial and often criticized because of its pathologizing connotation, terms such as intersex, variations of sex characteristics, or diverse sex development (dsd) are used as alternatives.3 The authors of this article follow the latter proposal, using intersex/dsd as an umbrella term and referring to the specific medical condition names if they are known.

Even today, the birth of a child with an intersex condition or dsd still leads to a variety of challenges and uncertainties concerning, for example, early genital surgery and the child's gender development. Well-established knowledge, such as on gender development and long-term outcomes of current treatment methods, is rare. Studies show that there is a great need to improve the education of and information for medical staff and psychological experts concerning the subject of dsd4 and to support parents in their decision-making processes while providing them with understandable information.5, 6, 7, 8 The lack of knowledge also opens up much room for debate about what might be right or wrong. Some of the arguments are based on assumptions rather than on empirical findings. This provides a breeding ground for controversy. In addition, the general paradigm shift in medicine toward a participation- and information-oriented approach is also entering the field of dsd, taking into account the need to better acknowledge ethical and human rights issues such as protecting children's rights to an open (ie, autonomous, self-determined) future and body integrity.9

Political projects in the context of intersex/dsd in Germany, where the study reported was conducted, have been dealing with 2 judicial processes: One initiative aimed at introducing a third gender category in personal status law and another focuses on forbidding unnecessary medical, sex-assigning surgery.

The aim of this study was to identify the most controversial issues in current debates about intersex, as we do not know which issues the individuals involved through personal experience are most concerned about and which may probably cause the most distress and need for psychosocial counseling. There are several topics that have continuously caused controversial discussions in the past. We will summarize them in the following sections.

Medical and Health-Related Issues

Since the 1990s, John Money's “optimal gender policy” from the 1950s of making intersex invisible via sex-reassignment surgery and then raising the child in the corresponding gender has been widely criticized and has proven to have caused a great deal of harm to the persons concerned.10,11

The Consensus Statement of 2006 proposes the cautious handling of cosmetic surgeries.2,12 However, statistics show that the number of surgeries has not declined as much as one would expect against the background of the Consensus Statement and new country-specific recommendations and guidelines that have been developed for physicians, esp. (pediatric) endocrinologists, andrologists, gynaecologists, (paediatric) surgeons, and urologists.13, 14, 15 Views on what is medically necessary and what is cosmetic differ. For example, there is a controversy as to whether surgical interventions in children can be justified in cases of hypospadias to ensure that the child can urinate standing up.1 Early genital surgery is a highly contentious issue, not least because the questions associated with it can be discussed from ethical, psychological, cultural, and medical perspectives.16

Other controversies concerning medical issues relate to the question of whether congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) plays a special role within intersex/dsd conditions.17 Some voices among CAH parents and self-help groups do not speak against early surgery, namely separation of the urethra from the vagina, in contrast to the case in connection with other intersex/dsd conditions.1,18 However, there are also studies that indicate the dissatisfaction of CAH patients with such genital surgeries in infancy,19,20 and the arguments for an open future and for body integrity stand against early medically unnecessary interventions.

Furthermore, there is a controversial debate concerning the question of risks of degeneration and tumour, mainly in association with gonadectomies in partial (PAIS) and complete androgen insensitivity syndromes (CAIS). On the one hand, results concerning tumour risk vary widely, and on the other hand, there are different views on what risks are tolerable without intervening.1,21,22 There are no noninvasive imaging or biochemical screening methods yet that allow the in situ detection of carcinoma, which are preinvasive cancer lesions. Hence, guidelines for decision-making and providing full information to patients are the most well-founded basis for managing the risk of germ cell tumourigenesis in intersex/dsd conditions, although not fully clear-cut. In cases with lower risk, the decisions have to be made regarding if and when to perform a biopsy in cases. In cases with the highest risk, decisions have to be made concerning whether and when to perform prophylactic gonadectomy.22

The timing of surgical interventions is a critical subject of controversy. Some opt for early surgeries because better results are assumed concerning, for instance, cosmetic outcome and postoperative complications; others advocate delaying surgery.15,18,23, 24, 25, 26 In addition to that, there is no complete clarity on how good outcomes of surgeries performed on persons with intersex/dsd are defined regarding functionality, integrity of the body, or satisfaction with the results, that is to say which criteria to apply. Gender-binary thinking also often influences the kind of hormone-replacement therapy that is given. However, this does not necessarily provide the best outcome for every patient.1,27,28

Finally, there is a debate on how much medicine should be involved in the management of intersex/dsd conditions in general. Calls for depathologization stand in contrast to the central role of medicine in the field of intersex/dsd.29, 30, 31

So far, new forms of management such as the effect of regular psychosocial support in addition to medical counseling and the impact of medical treatments and surgical (non-)interventions are underresearched. Standardized data collection is still at the very beginning.32

Psychosocial Issues

At the level of treatments and decision-making, the lack of adequate psychosocial support is widely criticized. Matters of financing, ensuring care near the home, and the implementation of multidisciplinary competence centers present ample cause for discussion.1,4,33 How true, informed consent according to the demanded “full consent policy” can be obtained, for example, concerning the gender in which the child is brought up as well as medical interventions, is one issue that is controversially debated in this field, particularly in the case of underage children/minors.1,34

At the level of families and their social environment, openness vs secrecy provides cause for controversial debate. Studies indicate that, contrary to many parents’ fears, openness does not necessarily result in discrimination and that openness can be a big relief for parents. However, the right to privacy and decision-making of the child might speak against openness.35,36 Secrecy, in the context of intersex conditions, means that persons concerned hide this information about themselves because of shame or fear of rejection or stigmatization.35 Privacy, however, means that persons concerned are in a state of being free to not show certain aspects of themselves to other people. Thus, secrecy is associated with constraints, whereas privacy is associated with individual liberties.37

Naming and speaking about intersex/dsd is also a crucial issue associated with the matter of language. At the Consensus Conference in Chicago,∗ the term DSD—as an abbreviation of “disorders of sex development”—was agreed upon.38 However, this term is often criticized because of its stigmatizing and pathologizing connotation.39 Activists came to favour the term intersex. No term has yet been found that seems to be accepted by all people involved.40,41

Finally, at the level of everyday life, the aspect of parental decision-making regarding the gender allocation of their interchild is a crucial problematic issue. It is important to consider that besides dichotomization and pathologization of intergenderal or nonbinary identities, the denial that there is an inability to predict gender identity in adulthood has been a large problem within psychosocial and sex research and care [cf.42, 43, 44].

A review of psychosocial health-care literature from 2007 to 2017 comes to the conclusion that psychosocial input should be increased and medicalization decreased because meaningful dialogue over time is still too rare; parents too often are only provided poor communication and get far from enough support in the hospital setting; nonsurgical pathways for children still need to be established; “normalizing” surgery does not necessarily reduce parental stress and stigmatization but might even create or increase it; and people need to learn to talk about dsd-related experiences to enhance psychosocial well-being.45

Legal Issues

Other controversies concerning intersex/dsd revolve around legal issues. Activists and researchers have in many ways raised awareness of the violations of human rights resulting from the treatment practices of the “optimal gender policy”. Outside the domain of medicine, it is widely discussed whether enough is being done to prevent such violations of human rights in the future, for instance, whether laws prohibiting medically unnecessary surgeries should be passed and how the existing laws should be enforced and human rights upheld.1,46,47

Moreover, the question of how intersex should be dealt with regarding the legal recording of a person's sex category is a matter of contention. The questions that are debated refer to the naming of a third sex category, the possibility of leaving the legal recording of a person's sex category open, and the decision-making bodies determining a person's sex category—such as medical staff or the persons concerned themselves—and the elimination of the legal recording of a person's sex category35,48

Previous studies, as described previously, mainly focused either on several of these issues at once (eg, from a more general human rights, psychosocial, historical, or sociocultural perspective) or on only one of these controversial issues (eg, from a rather specialized medical view). They did not point out which issue is associated with the highest explosiveness and/or the most insecurity or lack of knowledge. However, this might be important to know, for example, in the context of psychosocial counseling, scientific discussions, or psychotherapy to address these issues adequately. The degree of sensitivity that is needed is probably particularly high.

The research presented is part of the project “intersex-kontrovers” within the Hamburg Open Online University, a cooperative digital meta-university/institution of the 6 public universities of Hamburg aiming at creating open educational resources. Part of the project was the conceptualization of a weblog named “intersex-kontrovers” (cf. https://intersex-kontrovers.blogs.uni-hamburg.de). Through a participatory process, the blog aims at giving information on the issues that require particularly high sensitivity when dealing with them. Based on existing empirical findings and further research, the intention of the blog is to provide information concerning current controversies in intersex management. The project is conducted at the University Clinic of Hamburg-Eppendorf. The blog targets a broad group of users by involving and addressing medical students, parents, experts of experience/persons concerned, and experts in the field (eg, medical doctors and psychologists). Accompanying research is also part of the “intersex-kontrovers” project.

Exploring the significance of individual controversial issues, the purpose of this exploratory study was to examine (Q1) what the most controversial and disputed issues in the context of intersex/dsd are, (Q2) which issues involve the greatest difficulty or uncertainty in decision-making, and (Q3) which issues are associated with the biggest knowledge gaps. Furthermore, the aim was to investigate whether the group of persons concerned and parents of children with intersex/dsd, on the one hand, and the group of experts in the field, on the other, had different views regarding these questions.

Material and methods

Data Collection

Data collection took place between June 2016 and February 2018. A questionnaire was distributed at the annual meeting of the support groups for intersex/dsd persons and for parents of children with intersex/dsd of the association “Intersexuelle Menschen e.V.” (in English: “Intersex People”) in July 2016. Both before and after this, participants were also recruited via personal e-mail contact, personal contact at conferences (eg, at the University of Surrey at the symposium “After the Recognition of Intersex Human Rights” on the 23rd and 24th of September 2016), professional e-mail distribution lists, and experts in the field. Thus, the aim was to ensure that different perspectives were included and that all potential participants were familiar with the current debates on intersex/dsd management. Participants gave their written informed consent to participate, as well as permission to use their data in an anonymous or pseudonymous form for research purposes and publication. No reimbursement was offered to the participants. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee.

Participants

The data and responses of one participant were excluded from the final data set, as only one question on the questionnaire had been answered by this participant. The final sample then included 29 individuals. 13 of 29 individuals self-identified as women, 6 of 29 self-identified as men, 1 of 29 (one person with an intersex/dsd condition) self-identified as man and woman at the same time, 6 of 29 (3 persons with an intersex/dsd condition, 2 parents, and one expert) self-identified as “other”, eg, “hermaphrodite” or “as my own self”, and 3 of 29 (one person with an intersex/dsd condition and 2 experts) did not specify. 20 of the 29 participants were female and 9 were male according to their birth certificate (Table 1). Participants were recruited through direct contact, mail, or e-mail. In the paper-pencil version, the questionnaire was given to them directly, or they received it from support groups to which it was sent in return envelopes by mail. Alternatively, they were contacted via the e-mail distribution list of a support group to which the questionnaire had been sent.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Characteristics | Total (N = 29) | Adults with intersex/diverse sex development (dsd) conditions (n = 6) | Parents of children with intersex/dsd conditions (n = 5) | Experts in the field (eg, psychologists, medical doctors) (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y); Mdn (range) | 47.9; 46.5 (31–80) | 50.8; 45.5 (42–68) | 45.2; 48.0 (38–50) | 47.6; 47.0 (31–80) |

| Gender (n/N) | ||||

| Female | ||||

| Gender identity | 13/29 | 1/6 | 2/5 | 10/18 |

| Gender role | 15/29 | 2/6 | 2/5 | 11/18 |

| Gender of birth certificate | 20/29 | 5/6 | 4/5 | 11/18 |

| Male | ||||

| Gender identity | 6/29 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 5/18 |

| Gender role | 8/29 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 6/18 |

| Gender of birth certificate | 9/29 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 7/18 |

| Male and female | ||||

| Gender identity | 1/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 0/18 |

| Gender role | 1/29 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 0/18 |

| Other | ||||

| Gender identity | 6/29 | 3/6 | 2/5 | 1/18 |

| Gender role | 3/29 | 2/6 | 1/5 | 0/18 |

| No specification | ||||

| Gender identity | 3/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 2/18 |

| Gender role | 2/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 1/18 |

| Education (n/N) | ||||

| No school-leaving qualification | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/5 | 0/18 |

| Completion of 9 or 10 years of schooling (corresponding to German “Hauptschulabschluss” or “Realschulabchsluss”) | 1/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 0/18 |

| High-school examination qualifying for university entrance or university of applied sciences entrance | 4/29 | 4/6 | 0/5 | 0/18 |

| University degree | 23/29 | 1/6 | 4/5 | 18/18 |

| No specification | 1/29 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 0/18 |

| Personal experience with… (n/N) | ||||

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 10/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 9/18 |

| Disturbances of the androgenbiosynthesis (eg, 17 beta hydroxysteroid deficiency, 5 alpha reductase deficiency) | 7/29 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 5/18 |

| Gonadal dysgenesis | 9/29 | 3/6 | 1/5 | 5/18 |

| Klinefelter syndrome | 8/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 7/18 |

| Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome/androgen insensitivity syndrome | 13/29 | 2/6 | 3/5 | 8/18 |

| Ovotesticular dsd | 5/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 4/18 |

| Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome | 10/29 | 2/6 | 1/5 | 7/18 |

| Turner syndrome | 7/29 | 1/6 | 1/5 | 5/18 |

| Unknown intersex/dsd condition | 7/29 | 1/6 | 2/5 | 4/18 |

| I cannot answer this question. | 5/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 4/18 |

| I do not want to answer this question. | 1/29 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 0/18 |

| Another intersex/dsd condition | 4/29 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 3/18 |

6 of 29 of the resulting participants were adults with intersex/dsd conditions, 5 of 29 were parents of children with intersex/dsd conditions, 18 of 29 were experts in the field, that is, psychologists, psychotherapists, medical doctors, scientists, a legal expert, and researchers (Table 1). The age range of the participants was from 31 to 80 years, with a median of 46.5 years and a mean age of 47.9 years (standard deviation = 12.7). Most of the participants had a university degree (10/29) or a doctoral degree (8/29). Most participants lived in a city of more than 1,000,000 inhabitants (11/29) or in a city of 100,000 to 1,000,000 inhabitants (10/29).

CAIS (13/29), PAIS (10/29), and CAH (10/29) were the intersex/dsd conditions with which the highest number of participants had personal experience.

Measures

A questionnaire was developed that was suitable to be answered by German-speaking persons concerned, parents of children with intersex/dsd conditions, and experts in the field. The main part contained 8 open questions (qualitative part) and 3 multiple-choice questions (quantitative part) about requirements for a website on intersex/dsd and about challenges, conflicts, and insecurities in the context of intersex/dsd; the sociodemographic section included 9 questions, for instance, on gender role, gender identity, size of hometown, and education. The selection and construction of questions was based on current research literature. Answering the questionnaire took about 20 to 30 minutes. For the purpose of this study, the following single items and open questions were developed and then analyzed.

Most Controversial Issues (Q1)

In the quantitative part of the questionnaire, participants were asked which issues regarding intersex/dsd they considered most explosive and controversial. They could choose 7 out of 27 answer options which addressed medical topics (eg, “finding an individual hormone therapy with testosterone, oestrogen, gestagen, or combination therapies” and “procedure of diagnostic investigation and/or treatment after birth”) and legal and psychosocial topics (eg, “dealing with intersex/dsd in the family and one's social surroundings” and “lack of qualified counselling and advice options”) and the answer option “other” to name a topic that was not listed.

In the qualitative part of the questionnaire, participants were asked which issues regarding intersex/dsd they considered to be associated with the most conflicts.

Issues Associated With the Most Difficulty and Uncertainty in Decision-making (Q2)

In the quantitative part of the questionnaire, participants were asked which 3 subjects of consultation they considered to be most urgent. They could choose out of 9 answer options which addressed “family and partnership” (eg, “partnership and sexuality”), “gender development” (eg, “information about somato-sexual development”), “medicine and health” (eg, “questions regarding health and healthcare”), and “legal topics” (eg, “change of civil status”), and also the answer option “other” to name a topic that was not listed.

In the qualitative part of the questionnaire, participants were asked which decisions regarding intersex/dsd they considered to be the most difficult. Furthermore, they were asked to indicate—against the background of their own personal experience—which decisions concerning intersex/dsd they considered most help is needed.

Issues Associated With the Biggest Knowledge Gaps (Q3)

In the qualitative part of the questionnaire, participants were asked which issues regarding intersex/dsd they considered to be associated with the most need for further research and thus the biggest presumed knowledge gaps.

Data Analysis

Owing to the exploratory nature of the study and to extend the study's possible results, a mixed-method design was considered most appropriate for examining the research questions.49 Quantitative data were analysed descriptively. Statistical analyses were performed by means of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Because of the small sample size and figures of less than 5 in one or 2 of the cells in the 2 by 2 tables, group differences in the nominal data were analyzed by means of Fisher's exact test. As Fisher's exact test does not require a certain sample size, it is appropriate for small sample sizes and can be used for group comparisons. In terms of content, it makes sense to differentiate between persons who are directly affected (parents and intersex persons) and persons who represent a professional standpoint (experts in the field) to come to know if perceptions, needs, and perspectives correspond or diverge.

Qualitative data, in the form of answers to open-ended questions, were analyzed separately according to the principles of Mayring's qualitative content analysis.50 Categories and subcategories were built inductively, that is, via generalizations directly from the text without being based on previously defined theoretical concepts. The categories were built by the first author and, for cross-validation, discussed with the last author in a triangulation process and adjusted, for instance, refined or integrated into another category, if required. This approach was chosen because it is suitable for mixed-method approaches and allows the meaning units, that is, the statements that relate to the same central meaning, making up the qualitative categories and subcategories to be displayed in a quantitative manner.

Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately. Finally, the results were converged to answer the research questions. For the purpose of publications, the open answers, which were all given in German, were translated into English by the first author. Back-and-forth translation was performed for those answers where translation was ambiguous and possibly misleading.

Results

For each of the research questions, the results of the quantitative part are presented first followed by the results of the qualitative part, except for research question Q3, which had no quantitative part.

Most Controversial Issues (Q1)

Results of the study show that issues surrounding surgical interventions that are not life-sustaining treatments are regarded as the most controversial and most disputed issue in the context of intersex/dsd.

Quantitative Part

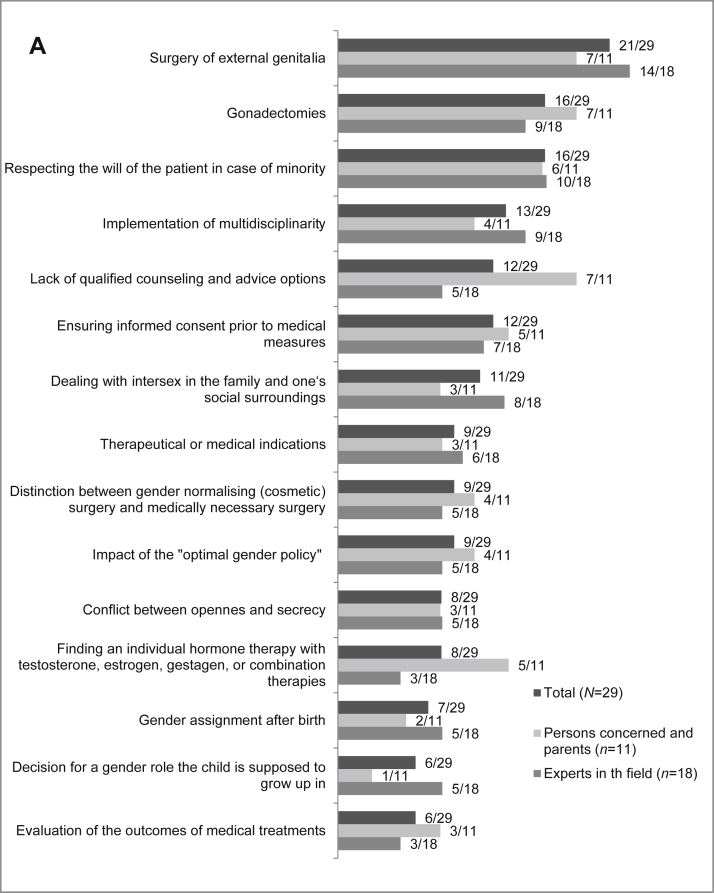

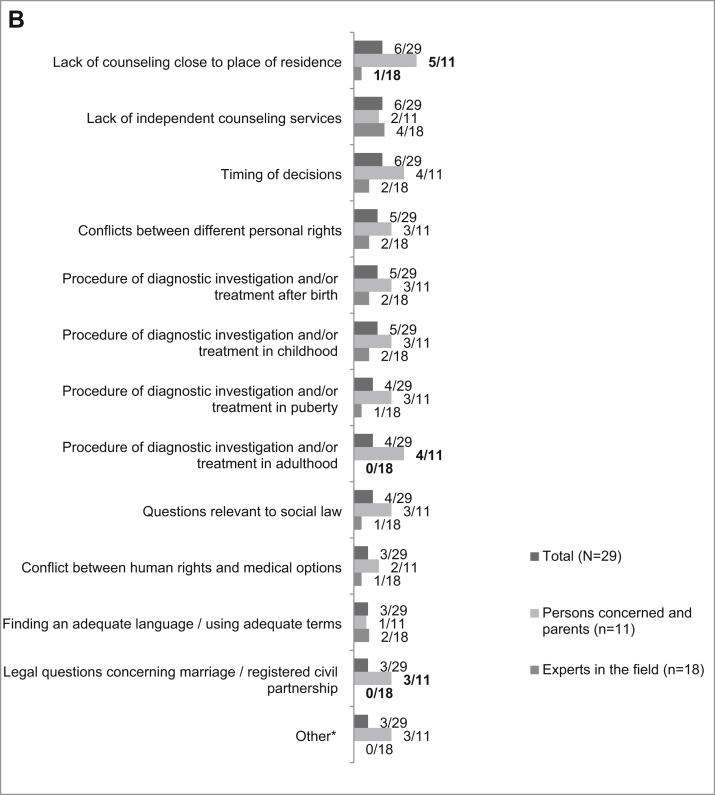

In the quantitative part of the questionnaire, the response that was given most often was “Surgery of external genitalia”, followed by “Gonadectomies” and “Respecting the will of the patient in case of minority” (Figure 1A). The proportion of the group of persons concerned and parents and the proportion of experts in the field were quite similar in this respect.

Figure 1.

Panel A shows the most frequently named controversial issues. Panel B shows controversial issues and significant differences. Significant differences in bold letters. ∗The following answers were given: transition (a parent); depends on the hospital (“…after birth”)—depends on the diagnosis/medical doctor (“…in childhood”)—depends on the diagnosis medical doctor (“…in puberty”)—usually lacking (multidisciplinarity)—does that exist? (timing) (a parent); lack of information on adoptions + own parenting (a person concerned).

However, some answers were significantly more often chosen by the group of persons concerned and parents than by experts in the field. The proportion of participants from the group consisting of persons concerned and parents who considered “Procedure of diagnostic investigation and/or treatment in adulthood” to be one of the most controversial issues was 4 out of 11, whereas none of the group consisting of experts in the field considered this to be one of the most controversial issues (P = .014). Between these groups, there was also a significant difference in the proportion who considered “Legal questions concerning marriage/registered civil partnership” to be one of the most controversial issues (P = .045). The figures were 3 out of 11 individuals in the group of persons concerned and parents and zero in the group of experts in the field. Furthermore, the proportion of persons concerned and parents who considered “Lack of counseling close to place of residence” to be one of the most controversial issues was significantly different from the proportion of experts in the field who considered this to be one of the most controversial issues (P = .018). The figures were 5 out of 11 individuals in the group of persons concerned and parents and one out of 18 in the group of experts in the field (Figure 1B).

While all participants seem to agree that irreversible surgical interventions and coping with minority status are highly sensitive and explosive issues, experts in the field tend to underestimate the importance of long-term services of psychosocial and medical care for persons concerned and their parents.

Qualitative Part

Concerning the most controversial and disputed issues, the results of the quantitative part of the questionnaire are corroborated by the results of the qualitative part (Table 2). Here the subcategories the participants regarded as being associated with the most conflict were “Surgical interventions” and “Decision-making for children”. Showing the search for pros and cons, the subcategory “Surgical interventions” included statements such as “surgery yes/no/which one” (a parent), “sex-reassignment surgery” (a parent), “surgical interventions like gonadectomies justified by ‘risk of degeneration’—though reliable/meaningful statistical investigations are lacking” (a parent), and “surgery on genitalia of children and youths” (a person concerned). Showing clear, deep ethical concerns, the subcategory “Decision-making for children” mainly contained statements such as “surgical interventions that are not medically necessary on children who are incapable of giving consent” (a parent) and also answers such as “informed consent, parents decide for their children” (an expert in the field), “self-determination” (an expert in the field), and “physical integrity” (an expert in the field).

Table 2.

Qualitative part: System of categories and number of coded text passages

| Group of participants categories and subcategories | Persons concerned | Parents | Experts in the field | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question: Which issues regarding intersex/dsd do you consider to be associated with the most conflicts? | ||||

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 18 | ||

| 1 Ethics | ||||

| 1.1 State or other controls | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.2 Decision-making for children | 1 | 2 | 7 | 10 |

| 1.3 Participation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.4 Trust (eg, “misinformation”) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 (Medical) treatment | ||||

| 2.1 CAH | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.2 Surgical interventions | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 |

| 2.3 Timing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2.4 Treatment practices | 1 | 0 | 7 | 8 |

| 3 Psyche and social environment | ||||

| 3.1 Closest reference persons (eg, “overweighting the issue intersex in the everyday life of a family with an intersex child”) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 3.2 Gender identity/role | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 3.3 Openness (eg, “taboo vs openness”) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 Society | ||||

| 4.1 General public (eg, “public perception”) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 4.2 Norms/law | 5 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| 5 Residual category | ||||

| 5.1 Lack of knowledge | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 5.2 Life-span perspective (eg, “development in puberty”) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 5.3 Political correctness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 11 | 43 | 70 |

| Question: Which decisions regarding intersex/dsd do you consider to be most difficult? | ||||

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 18 | ||

| 1 Development | ||||

| 1.1 Attitude of the parents (eg, “aptitude to withstand the ‘atypical’”) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 1.2 Choice of partner | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.3 Identity (eg, “gender of rearing”) | 3 | 2 | 12 | 17 |

| 1.4 Normality vs specificity (eg, “What are ‘normal’ difficulties and what is caused by the diagnosis?”) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 Medical treatment | ||||

| 2.1 Choice of physician | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2.2 Cost issues | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.3 Decisions on treatment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 2.4 Hormone therapy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 2.5 Education of the patient | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2.6 Surgery | 1 | 3 | 9 | 13 |

| 3 Social environment | ||||

| 3.1 Education | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3.2 Openness | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3.3 Stigma (ie, “Processing that something is ‘wrong’ with the child—enduring, recognizing, observing, respecting, appreciating, accepting”) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 Residual category | ||||

| 4.1 Abortion | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4.2 Nondecision (ie, “Is the decision to not decide anything a good decision?”) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4.3 Openness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 16 | 32 | 56 |

| Question: In the case of which decisions concerning intersex/dsd is—against the background of your own personal experience—most help needed? | ||||

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 17 | ||

| 1 Dealing with intersex in everyday life | ||||

| 1.1 Acceptance | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 1.2 Gender (eg, “in deciding which gender identity is livable”) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| 1.3 Self-esteem (eg, “to withstand adjustment pressure”) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 1.4 Sexuality | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 1.5 Talking about diverse sex development | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 Life-span perspective | ||||

| 2.1 Birth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.2 Choice of partner | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.3 Diagnosis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2.4 Early childhood | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 2.5 Puberty | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 Medical and psychosocial issues | ||||

| 3.1 Interventions and treatment | 5 | 3 | 6 | 14 |

| 3.2 Medical care services (eg, “navigation through the health care system”) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 Residual category | ||||

| 4.1 Juridical issues | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4.2 Timing (ie, “when postponing decisions”) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 10 | 5 | 28 | 43 |

| Question: Which issues regarding intersex/dsd do you consider to be associated with the most research and knowledge gaps? | ||||

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 18 | ||

| 1 Medical science | ||||

| 1.1 Cerebral gender differences | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.2 Diagnostics | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 1.3 Etiology | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1.4 Fertility | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1.5 Progress (ie, “How can we move forward in medicine?”) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1.6 Risk of degeneration | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 Quality of care | ||||

| 2.1 Effect of psychosocial support | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2.2 Influencing factors on outcome | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2.3 Long-term outcome | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 |

| 2.4 Care of older patients | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 Society and gender | ||||

| 3.1 Dealing with intersex/dsd | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 3.2 Education | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 3.3 Gender development (eg, “development and prognosis for the development of the psychological gender”) | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 3.4 Historical appraisal (ie, “intersex in the Nazi period”) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 Residual category | ||||

| 4.1 Advantages (ie, “How does a system/the society ‘benefit’ from variance/variation/diversity?”) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.2 Hypospadias | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.3 Puberty | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8 | 14 | 25 | 47 |

CAH = congenital adrenal hyperplasia; dsd = diverse sex development.

The frequent appearance of the subcategory “Norms/law” shows that intersex/dsd conditions challenge prevailing thinking patterns and norms such as the gender binary, with statements such as “civil status” (a person concerned) and “deviation from the norm–how to deal with it” (an expert in the field).

Issues Associated with the Most Difficulty and Uncertainty in Decision-Making (Q2)

The most difficult decisions and most uncertainties in decision-making show 3 main areas of concern.

Quantitative Part

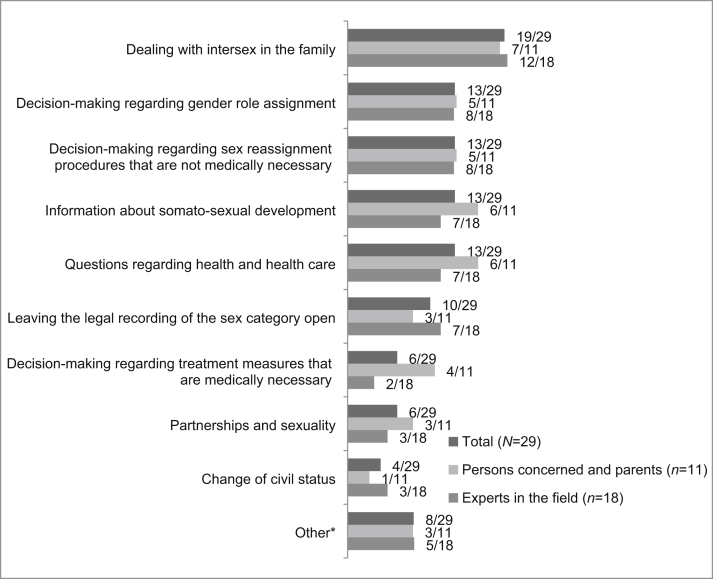

In the quantitative part of the questionnaire, “Dealing with intersex in the family” turned out to be the most urgent subject of consultation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Issues associated with the most difficulties and uncertainties in decision-making. ∗The following answers were given: additional sex category for legal recording (a parent); dealing with intersex/dsd in the social environment (a parent); actually all topics are equally important respectively other priority/depends on individuals, culture, state of knowledge, … (a parent); parenthood (reproduction/adoption) (a person concerned); self-determination (2x) (an expert in the field); counseling of persons not concerned in dealing with persons concerned (children and adults) (an expert in the field); prohibition of interventions for the purpose of making gender unambiguous and assigning gender (an expert in the field); cannot limit myself to 3 answers. All are important. (an expert in the field).

There were no significant differences between the group consisting of persons concerned and parents on the one hand and the group consisting of experts in the field on the other.

Qualitative Part

In the qualitative part (Table 2), the subcategories “Identity” and “Surgery” played an important role in the answers to the question about most difficult decisions. The complex issue of identity was underlined by responses such as “Gender assignment” (an expert in the field), “Parents decide about the social role” (a person concerned), “Self-discovery” (a person concerned), and “Letting children develop as they are” (an expert in the field). In the context of surgery, questions of decision-making and timing were main ones brought up.

The subcategory “Interventions and treatment” was of significant relevance in the responses concerning decisions for which most help is needed. Gonadectomies was one topic of major concern in this subcategory. Answers in this subcategory were, for example, “How high is the risk of degeneration of the gonads for persons with CAIS? Does a gonadectomy ‘have to be’ carried out, and if so, when?” (a parent); “all irreversible measures” (a person concerned); “prescription: and monitoring the hormone levels” (a person concerned); “medical care of treated intersex people in adulthood” (a person concerned); “surgical correction” (an expert in the field); “dealing with proposals of medical treatment” (an expert in the field); and “support of parents in treatments prior to the age when children can decide” (an expert in the field).

Issues associated with the biggest knowledge gaps (Q3)

In the qualitative part (Table 2), issues associated with the biggest knowledge gaps to a large part reflect biomedical shortcomings, namely the lack of long-term studies about outcomes of certain treatment measures, covered by the subcategory “Long-term outcome”. This subcategory included statements such as “long-term effects of treatment and non-treatment” (a parent), “prospective long-term studies on successful vs non-successful medical interventions” (an expert in the field), and “effects of treatments with surgery and hormone therapy in childhood and adolescence on the later life of the persons concerned” (a person concerned). They underline the challenge of being faced with an array of uncertainties about the future when living with intersex/dsd.

Finally, the participants were also asked which term they preferred for intersex/dsd conditions. 8 of the 29 participants preferred the term “Intergeschlechtlichkeit” (in English: intersexuality), 5 of 29 the term “Variationen der körperlichen Geschlechtsentwicklung” (in English: diverse sex development), 3 of 29 the term “Inter∗”, and 3 of 29 the term “Intersex”. Persons concerned mostly preferred the term “Intergeschlechtlichkeit” (2/6), parents the term “Inter∗” (2/5) or “Intergeschlechtlichkeit”, (2/5) and experts in the field the term “Variationen der körperlichen Geschlechtsentwicklung” (5/18).

Discussion

The study presented addressed the most controversial and disputed issues in the context of intersex/dsd, the greatest difficulty or uncertainty in decision-making, and which issues are associated with the biggest knowledge gaps.

Most Controversial Issues

Our results clarify that irreversible surgical interventions and coping with minority status are issues that are particularly sensitive and explosive. Moreover, they indicate that experts in the field do not perceive long-term services for psychosocial and medical care as important as their target group, namely persons concerned and their parents. Previous research, in part, reports similar results.4,33,45 The appearance of the subcategory “norms/law” in the qualitative part underlines that intersex/dsd confronts people with the necessity to question long-established thinking patterns. As gender-binary and dichotomous thinking is deeply rooted in society,51 the findings demonstrate that phenomena beyond these established categories cause substantial uncertainty.

Issues Associated With the Most Difficulty and Uncertainty in Decision-Making

The results concerning issues that involve the greatest difficulty or uncertainty in decision-making show that there is a special need for support with respect to everyday life issues and in coming to decisions on treatment, in particular surgical interventions and decisions on gender. This reflects empirical evidence that social support has an impact on adult well-being but that adequate psychosocial support is still lacking in the context of intersex/dsd care.4,33,52,53

Issues Associated With the Biggest Knowledge Gaps

“Long-term outcome” was associated with the biggest knowledge gaps. This reflects that knowledge concerning late effects of hormone-replacement interventions or genital surgery, for example, is still insufficient. Although advances in research on intersex/dsd have been made, there are still many challenges, for instance, how to combine psychosocial with hormonal and genetic research.9,38,54 On a side note, as a rather new controversial topic, the question of how to deal with hypospadias is also brought up. The assessment and management of hypospadias is associated with questions that are the subject of discussion, for example, classification, etiology, optimal age for surgical interventions, postoperative evaluation, risk of postoperative complications, and psychosocial impact.55,56 Some authors emphasize functional and cosmetic problems associated with untreated hypospadias, although based on a small sample size.57 More critical approaches highlight that the effect of framing is often underestimated by medical professionals and that, in favour of their child, nonmedical pathways can also be opened up for parents who have sons with hypospadias.58 The issue of hypospadias illustrates the problem of knowledge gaps that is so relevant in the more “classical” dsd conditions, such as CAIS, too.

Decision-Making

The results of the study make clear that on the one hand, intersex/dsd controversies and uncertainties revolve around one-time decisions with deep impact via emotional and somatic changes that, for example, concern body image, hormone balance, sex life, gender role, and gender identity, in particular irreversible surgeries at a very young age, that is, without personal consent, with lifelong consequences such as the need for hormone-replacement therapy or loss of the capability for sexual sensation or body integrity. This can also be interpreted as a call for a consistent application of the concept of shared decision-making in the treatment of intersex/dsd.59 Shared decision-making is based on a process by which patients and health-care providers meet as equals and share responsibility for their final agreement.60 It goes along with less pronounced decisional conflict and increased patient satisfaction.61 Shared decision-making communication skills training courses for health-care providers have been developed, although their effectiveness is still underresearched and their implementation still insufficient.60,62,63 Shared decision-making tools have also been developed for dsd conditions such as CAIS and CAH, and their generalizability and applicability need to be researched.64,65

As we have to deal with controversies and knowledge gaps, matters of handling risk and uncertainty66 and ways of dealing with specific dilemmas41,67 play a crucial role. Thus, awareness of these issues should be raised. Moreover, the value, impact, and clarity of current medical guidelines2,15,18,68 and applicable law should continue to be discussed. Currently, for example, a new child-protection law is being debated in Germany questioning the legality of irreversible sex-assigning interventions without vital or functional medical need.69

Managing Everyday Life

Apart from decision-making processes, controversies and uncertainties revolve around ongoing and changing issues of everyday life, for instance, in the context of psychological and somato-sexual development, social surroundings, legal status, or romantic relationships. It should be taken into consideration what kind of support is most helpful for which concerns. Peer support with a psychosocial focus might be most effective in dealing with questions concerning how to deal with intersex in the family and with nonbinary gender identities. Studies have shown that in the health professions, norm-critical competence has been insufficiently taught in education until now and is only slowly being put into practice. First, health research practices need to acknowledge people of all genders to improve access to inclusive health care.70 Second, education in the health professions needs to promote a discussion about norm criticism combined with self-reflection to provide high-quality care to patients who do not comply with dominant societal gender norms.71 Third, health professionals need to move beyond binary gender concepts, for example, by using inclusive language and creating ambiguity, in their everyday work.72,73

When it comes to issues of medical interventions, fact-oriented decision-making aids and good knowledge transfer might be especially useful. In this context, a clear analysis of the legal situation regarding irreversible interventions in early childhood and medical indications is also of importance. Medical treatments in the context of intersex/dsd can be classified into treatments for life sustainment, treatments for maintenance/restoration of function, treatments for sex reassignment, and controversial treatments.11 In a recent review, Roen47 addresses the complex relationship between genital examination, genital surgery, and shame. Roen stresses the importance of reducing genital examination to promote psychosocial well-being, the health professional's responsibility for developing strategies to reduce shame and stigma, and the full engagement of parents in the decision-making process.

The findings are, moreover, relevant against the political and societal background in many European countries. In Germany, for instance, after being discussed on the highest political level, new legislation has introduced a third legal gender category (“divers”) after a supreme court decision from 2017 [cf.74]. Thus, social awareness of intersex/dsd is rising. Hence, in the long run, everyday life with intersex/dsd will probably change and be regarded as less exceptional and be better integrated in all kinds of social processes.

Implications

Intersex/dsd is a field that cannot be regarded only from a medical point of view, as has been done in the past. Here the fields of medicine, law, psychology, and society interact with each other. The study's results show the complexity of the issues around intersex. Interdisciplinary cooperation both in the field of care and in research is absolutely necessary to improve patient-oriented medical and psychosocial care.

The findings of the study underline previous research that indicates that parents with children with intersex/dsd are in need of different kinds of knowing: knowing what (ie, what the intersex/dsd condition is, what medication is needed, and what other support the child needs), knowing how (ie, how to cope, how to give the medication, and how to talk to the child), and knowing now (ie, what to tell other people, when to seek emergency care, and how to help the child develop knowing). Hence, parents need to develop kinds of knowing that go beyond medical information.75 Similarly, the present study shows that medical information is regarded as important but that it is far from sufficient to look only at medical issues.

As this is a pilot study, more thorough findings are necessary to understand some of the issues raised, such as “trust” or “psychosocial” needs. To find out more about the details that lie at the core of these issues—such as the need for managing shame and the fear of being misunderstood or stigmatized, as described by Roen45—based on the results of this study, the plan is to conduct qualitative research, that is, structured interviews with persons concerned, parents, medical doctors, and psychologists.

Limitations

This study was an exploratory pilot study with a small and heterogeneous sample. It remains to be examined whether the results also hold true for a larger sample size in which the proportions of the different groups of participants and gender are better balanced. In this study's group of participants, the female gender according to birth certificate and the female gender identity were overrepresented. The small sample size is to a large extent due to intersex/dsd being a rare condition, which is the reason why many studies in this field have small sample sizes. The overrepresentation of women is in a large part due to medical policies of the past which promoted “feminizing treatment”.

Moreover, most participants were experts in the field, that is, the proportions of persons concerned and parents were relatively small. The overrepresentation of experts in the field also accounted for the fact that most of the participants had a university or doctoral degree, that is, the spectrum of different education levels was rather narrow. There was also an underrepresentation of participants who lived in rural areas because the majority lived in cities of more than 100,000 inhabitants. Another limitation of the study is that all the persons concerned and parents were contacted via self-help groups. Opinions of persons concerned and parents who are not part of the support group or self-help networks who might have other perceptions concerning controversies and other needs and uncertainties are not represented in the participants of this study. The participants’ answers might have been influenced by the setting of data collection, which was different and variant (eg, at meetings, conferences, via e-mail contact), a fact that was not considered in the data analysis.

As this study was questionnaire-based, the answers are given retrospectively and perhaps do not always reflect the participants’ perceptions and weightings in concrete situations, for example, in situations of debating or decision-making on specific interventions. Furthermore, this questionnaire-based research leaves open the details such as thorough ethical considerations, particular social norms, or lack of tangible long-term studies, as well as which very specific knowledge gaps are mainly relevant, which lie at the core of the responses.

To investigate group differences, the group of persons concerned was analyzed together with parents of children with intersex/dsd as one group because of the small sample size. However, although both groups have personal experience with intersex/dsd, it does make an important difference in perspective if one is personally and physically affected or if one is affected as the parent of a child with a bodily variety. Thus, preferably both groups should also be looked at separately.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that the main controversial issues and uncertainties revolve around surgical interventions, such as genital surgery and gonadectomies. Moreover, how to adequately consider the consent of minors and how to deal with intersex/dsd in the family seems to be riddled with insecurity. Further research is needed to provide more details concerning these sensitive issues to improve medical and psychosocial care toward a holistic approach.

The findings should be read in the context of building psychosocial programs in sexual health and medicine enabling parents and patients affected to talk and communicate their questions and concerns. In the past, a culture and climate of silence and shame has suppressed an open communication process, thereby magnifying the experience of invisibility and shame. Answering the identified need for psychosocial care and help in dealing with the uncertainties and teaching people to talk with others about intersex/dsd-related experiences could be inspired by the experiences of family care programs offered in the context of care programs for families with other chronic conditions. As Roen45 points out, individual and systemic help structures might thereby also contribute to developing not only individual health care but also community-based interventions.

Statement of authorship

Category 1

-

(a)Conception and Design

- Ute Lampalzer; Katinka Schweizer

-

(b)Acquisition of Data

- Ute Lampalzer; Katinka Schweizer

-

(c)Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- Ute Lampalzer; Katinka Schweizer; Peer Briken

Category 2

-

(a)Drafting the Article

- Ute Lampalzer

-

(b)Revising It for Intellectual Content

- Ute Lampalzer; Katinka Schweizer; Peer Briken

Category 3

-

(a)Final Approval of the Completed Article

- Ute Lampalzer; Katinka Schweizer; Peer Briken

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants in the study as well as all cooperation partners and supporters of the project “intersex-kontrovers” within the HOOU (Hamburg Open Online Universtiy). We would also like to thank Catherine Schwerin and Elaine Balkenhol for their thoughtful language advice and corrections, as well as Alexander Redlich for his interest in this field of study and for being a supervisor in this research process.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This study was funded by Behörde für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Gleichstellung der Stadt Hamburg.

The Consensus Conference in Chicago was held in October 2005. It was a meeting of professionals working in the field of intersex/dsd and a couple of support group representatives and was hosted by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology.

References

- 1.Amnesty International . Amnesty International; London: 2017. First, do no harm – ensuring the rights of children with variations of sex characteristics in Denmark and Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee P.A., Houk C.P., Ahmed S.F. In collaboration with the participants in the International Consensus Conference of intersex organised by the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e488–e500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao L.M., Roen K. Intersex/DSD post-Chicago: new developments and challenges for psychologists. Psychol Sex. 2014;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweizer K., Lampalzer U., Handford C. Begleitmaterial zur Interministeriellen Arbeitsgruppe Inter- & Transsexualität [Supplementary material of the Interministerial Working Group “inter- & transsexuality”] Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend; Berlin: 2016. Kurzzeitbefragung zu Strukturen und Angeboten zur Beratung und Unterstützung bei Variationen der körperlichen Geschlechtsmerkmale [Short-time survey on structures and offers regarding counseling and support for persons with diverse sex development] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyse K.L., Gardner M., Marvicsin D.J. “It was an overwhelming thing”: parents’ needs after infant diagnosis with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Pediatr Nurs. 2014;29:436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crissman H.P., Warner L., Gardner M. Children with disorders of sex development: a qualitative study of early parental experience. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1687-9856-2011-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michala L., Liao L.M., Wood D. Practice changes in childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia? J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Streuli J.C., Vayena E., Cavicchia-Balmer Y. Shaping parents: impact of contrasting professional counseling on parents’ decision making for children with disorders of sex development. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1953–1960. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cools M., Nordenström A., Robeva R. Caring for individuals with a difference of sex development (DSD): a consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:415–429. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Money J., Hampson J.G., Hampson J.L. Hermaphroditism: recommendations concerning assignment of sex, change of sex and psychologic management. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1955;97:284–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweizer K., Richter-Appelt H. Behandlungspraxis gestern und heute. Vom »optimalen Geschlecht« zur individuellen Indikation [Past and present treatment practices. From the “optimal sex” to individual indication] In: Schweizer K., Richter-Appelt H., editors. Intersexualität kontrovers. Grundlagen, Erfahrungen, Positionen [Intersexuality controversial. Basics, experiences, positions] Psychosozial-Verlag; Gießen: 2012. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes I.A., Houk C., Ahmed S.F. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2:148–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creighton S.M., Michala L., Mushtaq I. Childhood surgery for ambiguous genitalia: glimpses of practice changes or more of the same? Psychol Sex. 2014;5:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klöppel U. Zentrum für transdisziplinäre Geschlechterstudien, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin; Berlin: 2016. Zur Aktualität kosmetischer Operationen “uneindeutiger” Genitalien im Kindesalter [The current relevance of cosmetic surgeries on “ambiguous” genitalia in childhood] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krege S., Eckoldt F., Richter-Unruh A. Variations of sex development: the first German interdisciplinary consensus paper. J Pediatr Urol. 2018;15:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisniewski A.B., Tishelman A.C. Psychological perspectives to early surgery in the management of disorders/differences of sex development. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31:570–574. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin-Su K., Lekarev O., Poppas D. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia patient perception for diverse sex development. Psychol Sex. 2015;5:83–101. doi: 10.1186/s13633-015-0004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie (DGU) e.V . S2k-Leitlinie. Varianten der Geschlechtsentwicklung [S2k-guideline. Diverse sex development] AWMF; Berlin: 2016. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderchirurgie (DGKCH) e.V., Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderendokrinologie und –diabetologie (DGKED) e.V. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannsen T.H., Ripa C.P.L., Carlsen E. Long-term gynecological outcomes in women with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;1:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2010/784297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brinkmann L., Schuetzmann K., Richter-Appelt H. Gender assignment and medical history of individuals with different forms of intersexuality: evaluation of medical records and the patients’ perspective. J Sex Med. 2007;4:964–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang H., Wang C., Tian Q. Gonadal tumour risk in 292 phenotypic female patients with disorders of sex development containing Y chromosome or Y-derived sequence. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;86:621–627. doi: 10.1111/cen.13255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cools M., Looijenga L.H.J., Wolffenbuttel K.P. Managing the risk of germ cell tumourigenesis in disorders of sex development patients. Endocr Dev. 2014;27:185–196. doi: 10.1159/000363642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond M., Garland J. Evidence regarding cosmetic and medically unnecessary surgery on infants. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mouriquand P.D.E., Gorduza D.B., Gay C.L. Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: if (why), when, and how? J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willihnganz-Lawson K.H., Isharwal S., Lewis J.M. Secondary vaginoplasty for disorders for sexual differentiation: is there a right time? Challenges with compliance and follow-up at a multidisciplinary center. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yankovic F., Cherian A., Steven L. Current practice in feminizing surgery for congenital adrenal hyperplasia; a specialist survey. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:1103–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewitt J., Zacharin M. Hormone replacement in disorders of sex development: current thinking. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordenström A., Röhle R., Thyen U. On behalf of the dsd-LIFE group. Hormone therapy and patient satisfaction with treatment, in a large cohort of diverse disorders of sex development. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;88:397–408. doi: 10.1111/cen.13518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffiths D.A. Shifting syndromes: sex chromosome variations and intersex classifications. Soc Stud Sci. 2018;48:125–148. doi: 10.1177/0306312718757081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klöppel U. Transcript Verlag; Bielefeld: 2010. XX0XY ungelöst. Hermaphroditismus, Sex und Gender in der deutschen Medizin. Eine historische Studie zur Intersexualität [XX0XY unresolved. Hermaphroditism, sex, and gender in German medicine. A historical study on intersex] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klöppel U. Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, ed. Geschlechtliche Vielfalt. Begrifflichkeiten, Definitionen und disziplinäre Zugänge zu Trans- und Intergeschlechtlichkeiten. Begleitforschung zur Interministeriellen Arbeitsgruppe Inter- & Transsexualität [Gender diversity. Terms, definitions, and disciplinary approaches to transgender and intersex. Supplementary material of the Interministerial Working Group “inter- & transsexuality”] Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend; Berlin: 2015. Geschlechter- und Sexualitätsnormen in medizinischen Definitionen von Intergeschlechtlichkeit [Norms of gender and sexuality in medical definitions of intersex] pp. 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flück C., Nordenström A., Ahmed S.F. Standardised data collection for clinical follow-up and assessment of outcomes in differences of sex development (DSD): recommendations from the COST action DSDnet. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181:545–564. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krämer A., Sabisch K. Koordinations- und Forschungsstelle Netzwerk Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung NRW; Essen: 2017. Intersexualität in NRW. Eine qualitative Untersuchung der Gesundheitsversorgung von zwischengeschlechtlichen Kindern in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Projektbericht [Intersex in NRW. A qualitative investigation of the health care of intersex children in North Rhine-Westphalia. Project report] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoepffner W., Bennek J., Scholz M. Zur Geschlechtsrollenwahl bei Kindern mit Varianten der Geschlechtsentwicklung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Medizin und Gesellschaft [The gender choice of children with diverse sex development in the interplay of medicine and society] pädiatrische praxis. 2017;88:580–588. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schabram G. Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte; Berlin: 2017. “Kein Geschlecht bin ich ja nun auch nicht.” Sichtweisen intergeschlechtlicher Menschen und ihrer Eltern zur Neuregelung des Geschlechtseintrags [“I am also not no sex.” Viewpoints of intersex persons and their parents regarding the new law of birth certificate entries] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabisch K. Geschlechtliche Uneindeutigkeit, soziale Ungleichheit? Zum Alltagserleben von intersexuellen Kindern [Sex ambiguity, social inequality? Life circumstances of intersex children] Psychosozial. 2014;37:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danon L.M., Krämer A. Between concealing and revealing intersexed bodies: parental strategies. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:1562–1574. doi: 10.1177/1049732317697100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee P.A., Nordenström A., Houk C.P. Global disorders of sex development update since 2006: perceptions, approach and care. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85:158–180. doi: 10.1159/000442975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Topp S.S. Against the quiet revolution: the rhetorical construction of intersex individuals as disordered. Sexualities. 2013;16:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis G. The power in a name: diagnostic terminology and diverse experiences. Psychol Sex. 2014;5:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundberg T. University of Oslo, Faculty of Social Sciences; Oslo: 2017. Knowing bodies: making sense of intersex/DSD a decade post- consensus. Diss. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schweizer K., Brinkmann L., Richter-Appelt H. Zum Problem der männlichen Geschlechtszuweisung bei XX-chromosomalen Personen mit Adrenogenitalem Syndrom [The problem of male sex assignment of XX-chromosomal persons with congenital adrenal hyperplasia] Z Sexualforsch. 2007;20:145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schweizer K., Brunner F., Schützmann K. Gender identity and coping in female 46,XY adults with androgen biosynthesis deficiency (intersexuality/DSD) J Couns Psychol. 2009;56:189–201. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schweizer K., Brunner F., Handford C. Gender experience and satisfaction with gender allocation in adults with diverse intersex conditions (divergences of sex development, DSD) Psychol Sex. 2014;5:56–82. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roen K. Intersex or diverse sex development: critical review of psychosocial health care research and indications for practice. J Sex Res. 2019;56:511–528. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2019.1578331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.FRA – European Agency for Fundamental Rights . European Agency for Fundamental Rights; Wien: 2015. The fundamental rights situation of intersex people. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights . Council of Europe; Straßburg: 2015. Human rights and intersex people. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Althoff N., Schabram G., Follmar-Otto . Begleitmaterial zur Interministeriellen Arbeitsgruppe “Inter- & Transsexualität” – Band 8 [Supplementary material of the Interministerial Working Group “inter- & transsexuality” - Volume 8] BMFSFJ; Berlin: 2017. Status quo und Entwicklung von Regelungsmodellen zur Anerkennung und zum Schutz von Geschlechtervielfalt [Gender diversity in justice: the status quo and development of regulatory models to acknowledge and protect gender diversity] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanson W.E., Creswell J.W., Clark V.L.P. Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52:224–235. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayring P. Beltz; Weinheim: 2010. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. 11., aktualisierte und überarbeitete Auflage. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Memmer N. Geschlechterordnung im Wandel. Ist die duale Geschlechterordnung noch zeitgemäß? [Changing gender system. Is a dual gender system still relevant?] In: Brongkoll F., Groß L., Hagen S., editors. Die Frage nach dem Geschlecht. Hermaphroditismus und Intersexualität [The question of sex. Hermaphroditism and intersex] ScienceFactory; Norderstedt: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dessens A., Guaragna-Filho G., Kyriakou A. Understanding the needs of professionals who provide psychosocial care for children and adults with disorders of sex development. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schweizer K., Brunner F., Gedrose B. Coping with diverse sex development: treatment experiences and psychosocial support during childhood and adolescence and adult well-being. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:504–519. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roen K., Pasterski V. Psychological research and intersex/DSD: recent developments and future directions. Psychol Sex. 2014;5:102–116. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snodgrass W., Macedo A., Hoebeke P. Hypospadias dilemmas: a round table. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van der Horst H.J.R., de Wall, Hypospadias L.L. All there is to know. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2864-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhandarkar K., Garriboli M. Repair of distal hypospadias: cosmetic or reconstructive? EMJ Urol. 2019;7:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roen K., Hegarty P. Shaping parents, shaping penises: how medical teams frame parents’ decisions in response to hypospadias. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23:967–981. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siminoff L.A., Sandberg D.E. Promoting shared decision making in disorders of sex development (DSD): decision aids and support tools. Horm Metab Res. 2015;47:335–339. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bieber C., Gschwendtner K., Müller N. Partizipative Entscheidungsfindung (PEF) – Patient und Arzt als Team [Shared decision-making (SDM) – patient and physician as a team] Rehabilitation. 2017;56:198–213. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-106018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shay L.A., Lafata L.E. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision-making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Müller E., Strukava A., Scholl I. Strategies to evaluate healthcare provider trainings in shared decision-making (SDM): a systematic review of evaluation studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026488. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Müller E., Diesing A., Rosahl A. Evaluation of a shared decision-making communication skills training for physicians treating patients with asthma: a mixed methods study using simulated patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:612. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4445-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chawla R., Weidler E.M., Hernandez J. Utilization of a shared decision-making tool in a female infant with congenital adrenal hyperplasia and genital ambiguity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019;32:643–646. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2018-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weidler E.M., Baratz A., Muscarella M. A shared decision-making tool for individuals with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:150844. doi: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2019.150844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tannert C., Elvers H.D., Jandrig B. The ethics of uncertainty. In the light of possible dangers, research becomes a moral duty. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:892–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lundberg T., Dønåsen I., Hegarty P. Moving intersex/DSD rights and care forward: lay understandings of common dilemmas. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2019;7:354–377. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Douglas G., Axelrad M.E., Brandt M.L. Guidelines for evaluating and managing children born with disorders of sexual development. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41:e1–e7. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120307-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schock A. 2019. EU-Parlament stärkt Rechte intergeschlechtlicher Menschen [EU Parliament strengthens the rights of intersex people]https://www.aidshilfe.de/meldung/eu-parlament-staerkt-rechte-intergeschlechtlicher-menschen Available at: Accessed February 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frohard-Dourlant H., Dobson S., Clark B.A. “I would have preferred more options”: accounting for non-binary youth in health research. Nurs Inq. 2017;24:e12150. doi: 10.1111/nin.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tengelin E., Dahlborg-Lyckhage E. Discourses with potential to disrupt traditional nursing education: nursing teachers’ talk about norm-critical competence. Nurs Inq. 2017;24:e12166. doi: 10.1111/nin.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldhammer H., Malina S., Keuroghlian A.S. Communicating with patients who have nonbinary gender identities. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:559–562. doi: 10.1370/afm.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richards C., Bouman W.P., Seal L. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:95–102. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schweizer K., Köster E.M., Richter-Appelt H. Varianten der Geschlechtsentwicklung und Personenstand. Zur “Dritten Option” für Menschen mit intergeschlechtlichen Körpern und Identitäten [Diverse sex development and civil status. On the third option for individuals with intersex bodies and identities] Psychotherapeut. 2019;64:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lundberg T., Lindström A., Roen K. From knowing nothing to knowing what, how and now: parents’ experiences of caring for their children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:520–529. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]