Abstract

(1) Background: RNA viruses and especially coronaviruses could act inside host cells not only by building their own proteins, but also by perturbing the cell metabolism. We show the possibility of miRNA-like inhibitions by the SARS-CoV-2 concerning for example the hemoglobin and type I interferons syntheses, hence highly perturbing oxygen distribution in vital organs and immune response as described by clinicians; (2) Hypothesis: We hypothesize that short RNA sequences (about 20 nucleotides in length) from the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome can inhibit the translation of human proteins involved in oxygen metabolism, olfactory perception and immune system. (3) Methods: We compare RNA subsequences of SARS-CoV-2 protein S and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase genes to mRNA sequences of beta-globin and type I interferons; (4) Results: RNA subsequences longer than eight nucleotides from SARS-CoV-2 genome could hybridize subsequences of the mRNA of beta-globin and of type I interferons; (5) Conclusions: Beyond viral protein production, COVID-19 might affect vital processes like host oxygen transport and immune response.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, microRNA-like inhibition, Oxygen metabolism, Beta-globin translation inhibition, Type I interferons translation inhibition

Introduction

Viruses act in host cells by reproducing their own proteins for reconstituting their capsid, duplicating their genome [1] and leaving non-coding RNA or DNA remnants in host genomes [2]. Moreover, RNA viruses can also form complexes with existing mRNAs and/or proteins of host cells. Thereby they might prevent protein function, behave like microRNAs [3], [4], [5], [6] or ribosomal RNAs [6], [7], [8], inhibiting or favoring the translation of specific proteins of host cells [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. If these proteins are vital for the host, viral pathogenicity is much greater than that caused by viral replication. With regard to SARS-CoV-2, binding to existing host proteins has already been described [18]. Here, we aim to describe a potential miRNA-like action by viral RNA, in particular at the level of i) oxygen transport by hemoglobin, whose beta-globin and gamma 2 subunits synthesis can be inhibited, and ii) immune response, where type I interferon synthesis can be inhibited. We are not intending to prove here experimentally these inhibitions by small RNAs issued from the SARS-CoV-2 genome, but to prepare this future empirical step by pointing out its potential hybridizing power. In Section 3, we describe a method for finding SARS-CoV-2 inhibitory RNA sub-sequences, and results are given in Section 4, discussed in Section 5. Some perspectives of this work concerning an extension to the inhibition of translation of olfactory and interferon receptors are proposed in Section 6.

Hypothesis

We assume in this paper that short RNA sub-sequences (about 20 nucleotides in length) coming from the SARS-CoV-2 virus genes hybridize the messenger RNA of key human proteins involved in important metabolism as oxygen metabolism (hemoglobin), olfactory perception (olfactory receptors) and immune system (type I interferon), and hence, can inhibit their ribosomal translation.

Methods

Focusing on the seed part of miRNA-like sequences having a putative 8 nucleotide hybridization seed inhibition effect [19], [20] (minimum 7), we compare data from different databases

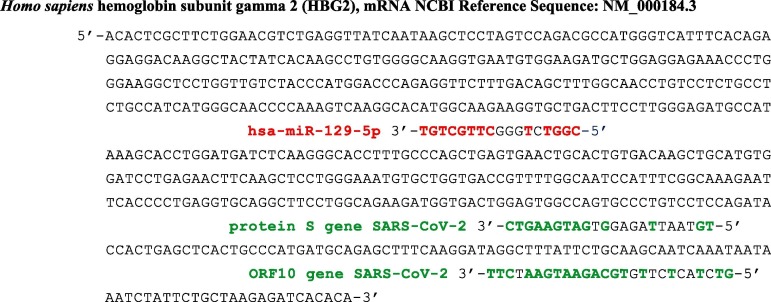

[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] using BLAST [27]. Fig. 1 shows microRNA 129-5p, a known inhibitor of a human foetal hemoglobin component, the gamma-globin 2, replaced in adult by the beta-globin regulated as the other component alpha-globin, by microRNAS [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Two sub-sequences from the SARS-CoV-2 genome, namely from genes of ORF10 and protein S, show the same hybridizing potential.

Fig. 1.

Complete mRNA sequence of the subunit gamma 2 of the fetal human hemoglobin [22]. Sequences in green (resp. red) come from protein S and ORF10 genes of SARS-CoV-2 (resp. hsa miR 129-5p), which can inhibit its ribosomal translation. Probability of length 8 anti-match in red (resp. 9 and 11 in green) by chance in 577 nucleotides equals 0.035 (resp. 0.017 and 0.0003) (T-G and G-T matches counting for ½). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Results

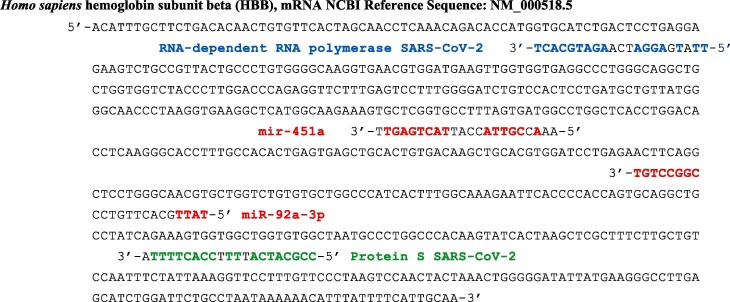

We will apply the method from Section 2 for showing examples where RNA subsequences of the SARS-CoV-2 genome have an inhibitory potential on the ribosomal translation of human mRNAs of the same type as that shown in Section 2 for human micro-RNAs. For example, miRTarBase shows that microRNA hsa-mir-92a-3p targets the beta-globin HBB subunit of adult hemoglobin, inhibiting its translation [25]. This is also the case for microRNas involved in the maturation of erythrocytes like miR-451a [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. We exhibit on Fig. 2 sub-sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 protein S and polymerase genes [23] having the same length of anti-matching as these microRNAs on the mRNA of the hemoglobin beta-globin (HBB) subunit gene.

Fig. 2.

Human beta-globin gene [24] potentially targeted by a subsequence of the gene of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (in blue) and by a subsequence of the gene of the SARS-CoV-2 protein S (in green) [23], by the human microRNAs hsa miR 92a-3p (in red) and hsa miR 451a (in red). Probability of red anti-matches of length 8 in a sequence of 624 nucleotides equals 0.04 and for the blue (resp. green) subsequence is 0.005 (resp. 0.017) (T-G and G-T matches counting for ½). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

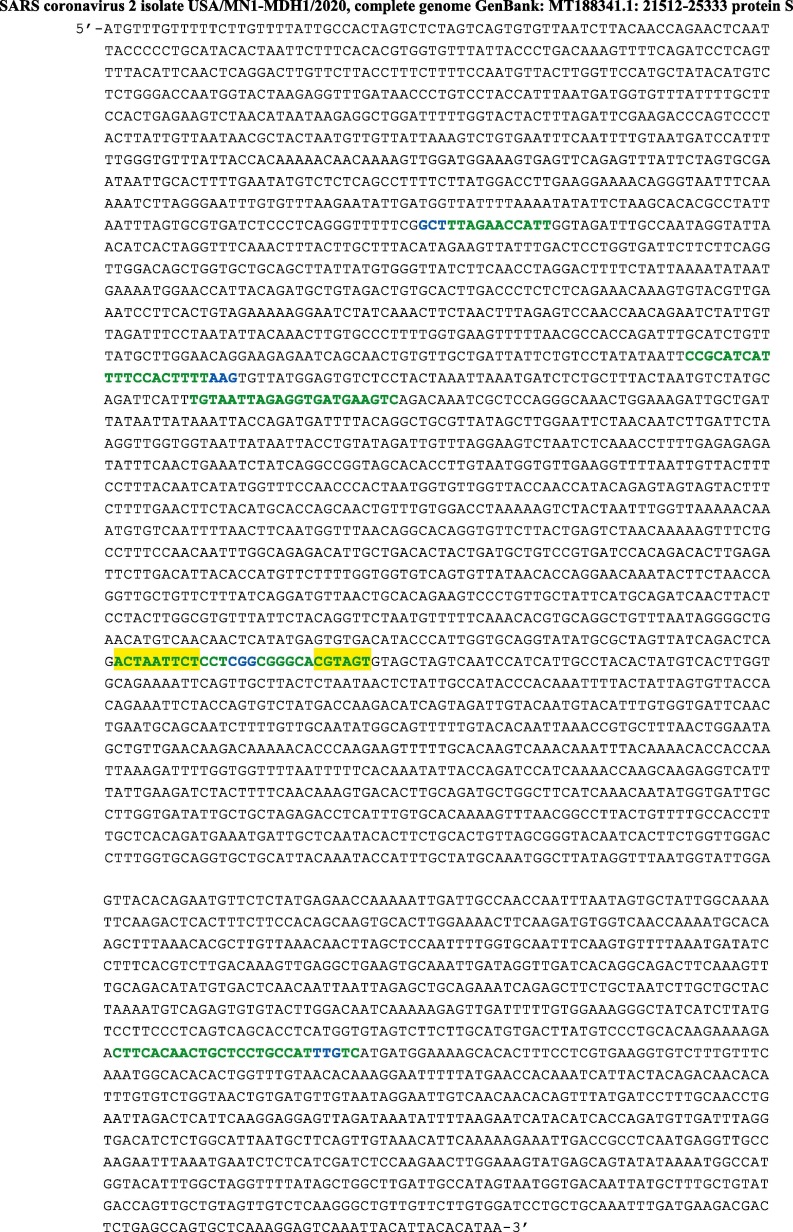

The second example concerns the gene of the spicule protein S of SARS-CoV-2, which shares a long subsequence of length 14 (664–678) with the gene of the Gag protein of the virus HERV-K102 (Fig. 3 ). Its potential targets are the mRNAs of human hemoglobin subunit beta-globin [22], human hemoglobin subunit gamma-globin 2 (HBG2) [23], human type 1 interferons and the human receptor ACE2.

Fig. 3.

mRNA sequence of the protein S of the virus SARS-CoV-2 [23]. The first green subsequence of length 14 (664–678) occurs in mRNA of Gag protein of the virus HERV-K102 [27]. The second of length 23 (1112–1134) anti-matches a mRNA subsequence of hemoglobin subunit beta-globin [22]. The third of length 22 (1200–1221) anti-matches a mRNA subsequence of hemoglobin subunit gamma-globin 2 (HBG2) [23]. The fourth of length 24 (2032–2055) matches a subsequence of mRNA of many type 1 interferons. Highlighted in yellow are sub-sequences common with the SARS furin cleavage site [33], [34]. The fifth of length 25 (3152–3176) matches a subsequence of mRNA of the receptor ACE2. Blue: mutations whose location of both codon and nucleotide involved [35] are, in order: 635 gCtagTt, 1133 aAgaaGg, 2045 cGgacAg and 3189 ttG > ttT. The probabilities of the above matches and anti-matches will be given in the following in Figures concerning each of them. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

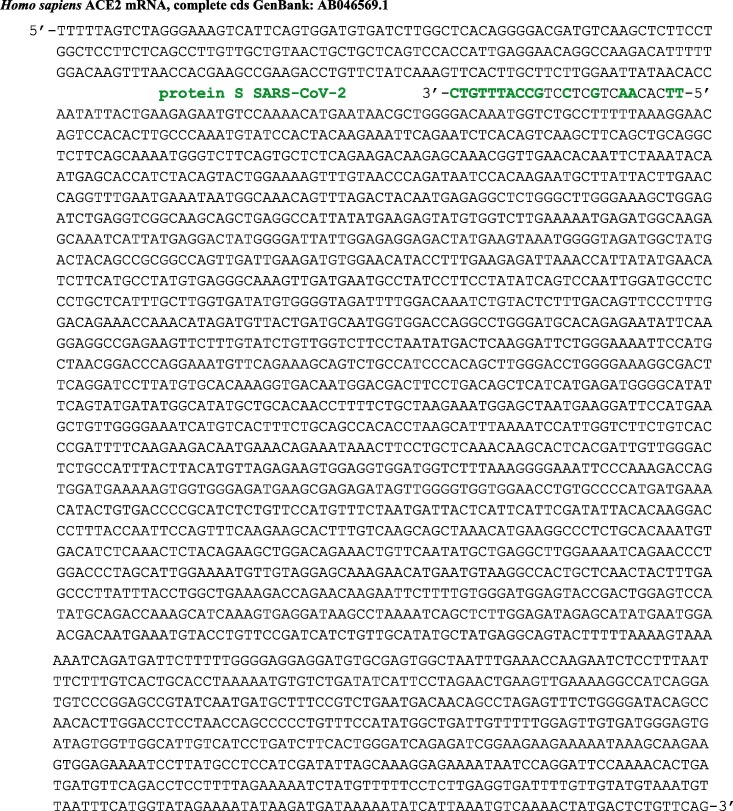

The classical protein–protein interaction of the spicule protein S of SARS-CoV-2 is with the human protein receptor ACE2, but there exists a putative miRNA-like translation inhibition due to a subsequence (in green) of the protein S gene (Fig. 3) matching the ACE2 mRNA (Fig. 4 ). The human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K102 [32] has been described as having an antagonizing power on HIV-1 replication, by stimulating antibody production. It is indeed capable of high replication rate in vivo and in vitro and this high particle production can stimulate an early protective innate immune response against HIV-1 replication. It could play the same role in SARS-CoV-2. A possible mechanism of this immune stimulation could be due to the fact that both Gag protein of HERV-K107 and protein S of SARS-CoV-2 share common sub-sequences as the subsequence of length 15 nucleotides from the protein S of the SARS-CoV-2 given in green on Fig. 5 .

Fig. 4.

mRNA sequence of the human protein receptor ACE2. The green 5′-3′ seed subsequence of length 10 is the reverse of an RNA sequence of the protein S of SARS-CoV-2. The probability to observe such an anti-match of length 10 by chance in a sequence of 2581 nucleotides equals 0.003. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

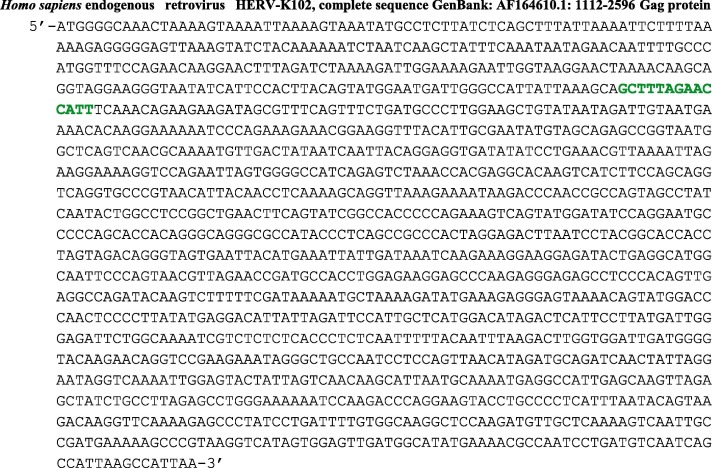

Complete RNA sequence of the Gag protein of the virus HERV-K102 [36]. The green subsequence of length 14 (271–285) is present in the RNA sequence of the protein S of virus SARS-CoV-2 [22]. The probability to observe this match of length 14 by chance in a sequence of 1475 nucleotides equals 10-6. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Discussion

When we combine the antibody power originated by the endogenous human retrovirus HERV-K102 envelop protein (whose part of its mRNA is shared by the SARS-CoV-2 protein S [36]) with the putative inhibitory role of circRNAs capable to block the miRNA-like action of SARS-CoV-2, one could understand why certain carriers of SARS-CoV-2 are completely asymptomatic and therefore, by mimicking their defence mechanisms, consider a possible therapy against SARS-CoV-2. Indeed, if we look on the “sponge effect” of circRNAs against microRNAs [37], [38], [39], one can consider a therapeutic effect erasing pathogenic actions of microRNAs.

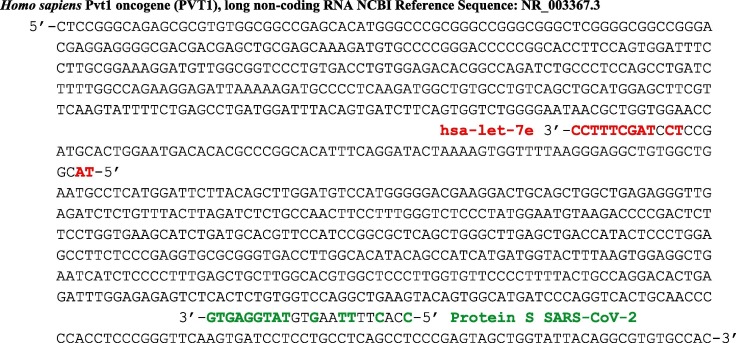

For example, in the case of the human let-7e microRNA, a sub-sequence of human circular RNA PVT1 [40] hybridizes hsa-let-7e (Fig. 6 ), thus preventing it from exerting a too important inhibition on the translation of proteins such as the gamma-globin 2. There exists a sub-sequence of the protein S of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 6), on which a similar action would be possible, hence reducing the miR-like pathogenicity of the protein S, but with less efficiency, with a hybridization free energy ΔG equal to −4.6 kcal/mol vs −11 for the hsa-let-7e.

Fig. 6.

RNA sub-sequence of the circPVT1 [22]. The RNA sequence in red is the microRNAs hsa miR let-7 inhibited by its “sponge” hsa-circ-PVT1. The RNA sequence in green is a sub-sequence of the protein S of SARS-CoV-2 on which hsa-circ-PVT1 could serve as inhibitor. Anti-match probability of a sub-sequence of length 9 in a sequence of length 1946 is 0.06 (resp. 0.03) for the red (resp. green) sub-sequence. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

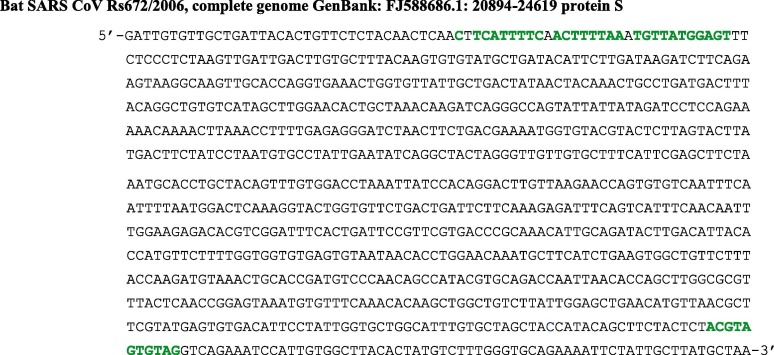

We can also compare the putative miRNA-like inhibitory efficacy of the protein S in other coronaviruses than SARS-CoV-2. By taking for example the SARS CoV Rs672 virus observed in 2006, it is possible to exhibit in the RNA sequence of its protein S gene some sub-sequences similar to those from SARS-CoV-2 involved in a miRNA inhibitory effect (Fig. 7 ): they have less nucleotides anti-matching their protein targets, which could explain lesser virulence of the SARS epidemic than of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.

Fig. 7.

RNA sub-sequence of the SARS CoV Rs672 protein S gene. Nucleotides in green are homologous to those of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene (in green on Fig. 3), which could explain the lesser virulence of SARS as compared to SARS-CoV-2 due to fewer anti-matches with their miRNA-like targets. The probability to observe by chance a sub-sequence of length 31 in a sequence of 3722 nucleotides with exactly 3 errors equals 3 C331 0.2531 = 3 10-15 and for a sub-sequence of length 11 equals 9 10-4. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

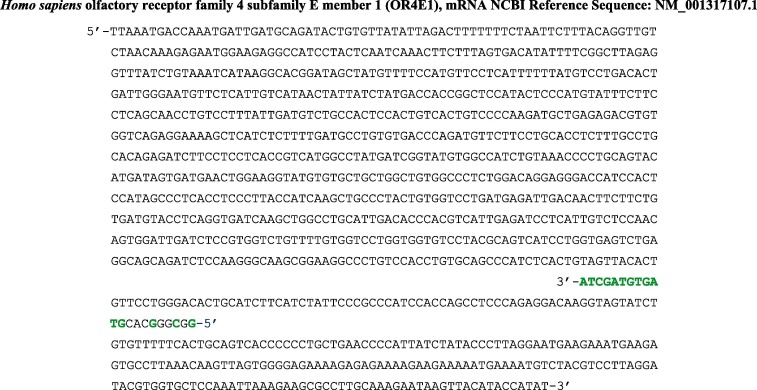

Among the symptoms of the COVID-19 disease, anosmia is frequently described. This defect could be due to a miRNA-like inhibition of mRNAs of genes from olfactory receptor family (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Complete mRNA sequence of the human olfactory receptor family 4 subfamily E member 1 (OR4E1) [22]. The RNA sequence in green is a sub-sequence of the protein S of SARS-CoV-2, which can exert a miRNA-like inhibition of the translation of OR4E1. The probability to observe such an anti-match of length 12 by chance in a sequence of 577 nucleotides equals 5 10-4. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Perspectives

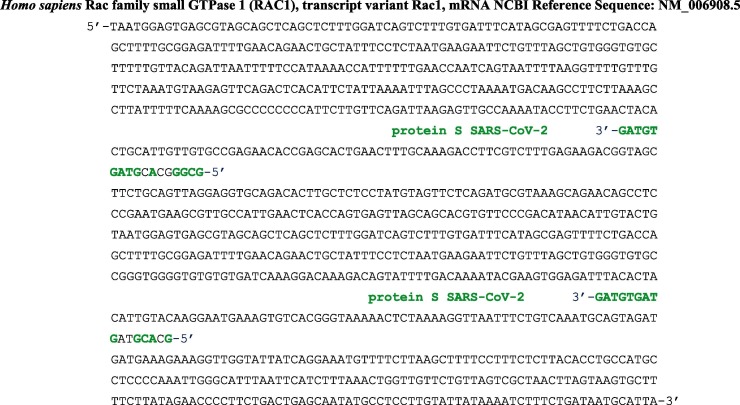

The perspectives of the present work are in the more in-depth study of unconventional mechanisms of action of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, in particular those concerning the disturbances of oxygen transport observed in many patients [41], [42]. We can also notice the resemblance of a SARS-CoV-2 sub-sequence with hsa-miR-let-7b, the microRNA the most upregulated in Kawasaki disease [43] described as potentially linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection [44]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus could have, more than a direct protein–protein interaction (proposed in [16] despite the criticisms of [45]), an effective inhibitory action in vivo of the same type as that predicted here in silico on the synthesis of subunits of human hemoglobin, and this action is more important for SARS-CoV-2 than for other coronaviruses (like the SARS CoV Rs672 on Fig. 8). This hypothesis is in agreement with numerous studies showing a decrease of adult human hemoglobin blood concentrations in severe COVID-19 cases [46], [47], presenting an increase of the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein as one of the three major predictors of severity [48], like in ß-thalassemia [49] and viral infections [50]. Hence, one could envisage a therapy blocking pathologic inhibitor effects on ribosomal translation of hemoglobin subunits, using for example circular RNAs as blockers of possible viral miRNA-like mechanisms (Fig. 7) [51], [52], [53], [54]. Another direction could be to search if furin cleavage site sub-sequence has the same type of interaction with key proteins like Rac small GTPase (a protein from the Rho GTPase family, which is a strong determinant of the virus-induced IFNbeta response [55], [56]), implicated in replication of many important viral pathogens infecting humans or like interferons. A first example is given by the human small GTPase 1 (Fig. 9 ) in which the inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene is possibly obtained through the same miRNA-like subsequence as for all type 1 interferons. The host immune system is indeed reacting to viral intrusion first with synthesis of type I interferons IFNalphas and IFNbetas [57], [58]. They are messengers allowing the activation of cellular defenses blocking viral replication. In humans, these type I interferons are bound to interferon receptors, and then, they induce proteins with antiviral actions: RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR), 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), RNase L, and Mx protein GTPases [59].

Fig. 9.

MiRNA-like subsequence of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene (from its furin cleavage site) anti-matching a subsequence of the human GTPase 1 gene. The probability to observe such anti-matches of length 9 by chance in the of the 2301-length sequence of the whole human GTPase 1 gene equals 0.017.

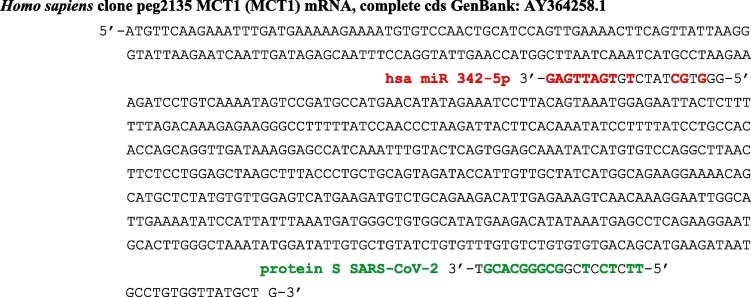

In the same way, the miRNA-like subsequence of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene from its furin cleavage site anti-matches the mRNA of the MCT1 gene involved in the lactate shuttle between astrocytes and neurons (Fig. 11 ) and this effect decreases the energy provided to the brain [61], [62]. That could explain some neurological and neuropsychiatric complications observed in SARS-COV-2 patients, since the earliest cohorts featured non-specific neurological symptoms, such as dizziness and headache.

Fig. 11.

MiRNA-like subsequence of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene (from its furin cleavage site) anti-matching the mRNA of the human MCT1 gene. The probability to observe this anti-match of length 9 by chance in a sequence of 638 nucleotides equals 2.5 10-3. In red, the micro-RNA hsa miR 342-5p inhibiting the human MCT1 gene sequence with a subsequence of length 8 and this anti-match has the probability 0.02 to occur by chance in a sequence of 638 nucleotides. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

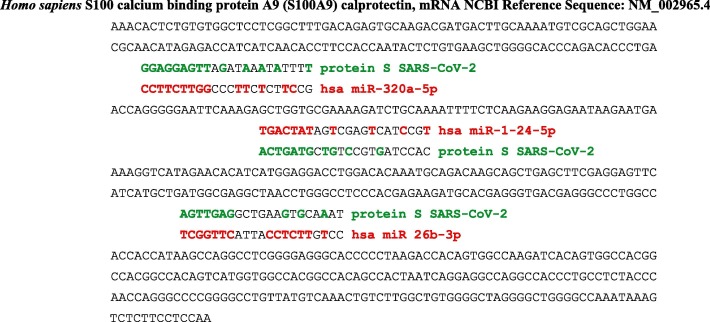

In [63], it is described a release of massive amounts of calprotectin (S100A8/S100A9) in severe cases of COVID-19. Studies about human microRNAs like hsa miR-320a-5p, hsa miR-1-24-5p and hsa miR 26b-3p identify the calprotectin as possible targets [64], [65], [66]. These microRNAs are inhibitors of the calprotectin (Fig. 12 ), but they can be hybridized by small sequences from protein S of SARS-CoV-2, which could play the same role as microRNAs sponges than the cellular circular RNAs [67], i.e., they can suppress their inhibitory power on the messenger RNA of their target proteins (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

MiRNA-like subsequences of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene (in green) anti-matching human microRNAs (in red) having as target the calprotectin (S100A9). The probability to observe the first anti-match of length 9 by chance in a sequence of 569 nucleotides equals 3.5 10-2. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

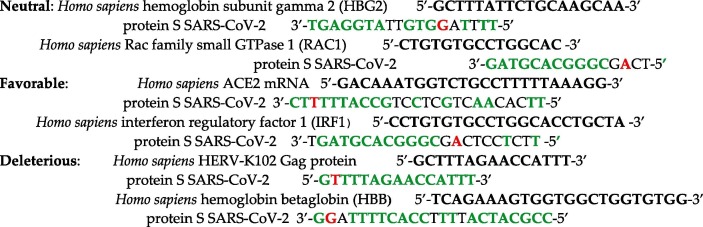

Eventually, the mutations observed on SARS-CoV-2 [35], [68], [69] can be neutral (without any effect), favorable (less pathogenic) or deleterious (more pathogenic). Among them, we have (mutations in red):

We can notice also that the protein S gene is not the only SARS-CoV-2 gene anti-matching important human molecules. It is for example the case of the ORF10 protein with the human gamma-globin 2 (Fig. 13 ).

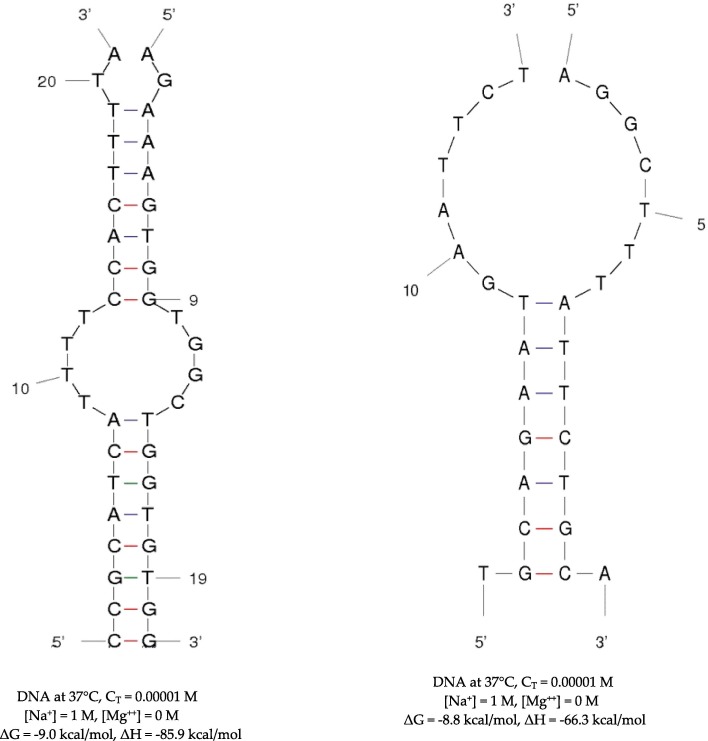

Fig. 13.

Hybridization between subsequences from SARS-CoV-2 genome and human genome. Left: hybridization between a subsequence of the SARS-CoV-2 Protein S gene and a subsequence of the gene of the human hemoglobin beta-globin (HBG) subunit (Fig. 2). Right: hybridization between a subsequence of the SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 gene and a subsequence of the gene of the human hemoglobin gamma-globin 2 (HGG 2) subunit (Fig. 1).

On Fig. 13, the free energy and enthalpy are given in kcal/mol for two hybridizations [70], [71] between subsequences of SARS-CoV-2 genes and subsequences of genes of two important proteins of the human metabolism of oxygen, involved in the oxygen transportation in adult for the first (the human hemoglobin beta-globin (HBG) subunit) and the in embryo for the second (the human hemoglobin gamma-globin 2 (HGG 2) subunit).

We have summarized the probabilities of anti-matches of Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, allowing for the comparison between the classical miRNA action and the putative inhibitory influence the protein S gene of SARS-CoV-2 can have on the translation of important human proteins.

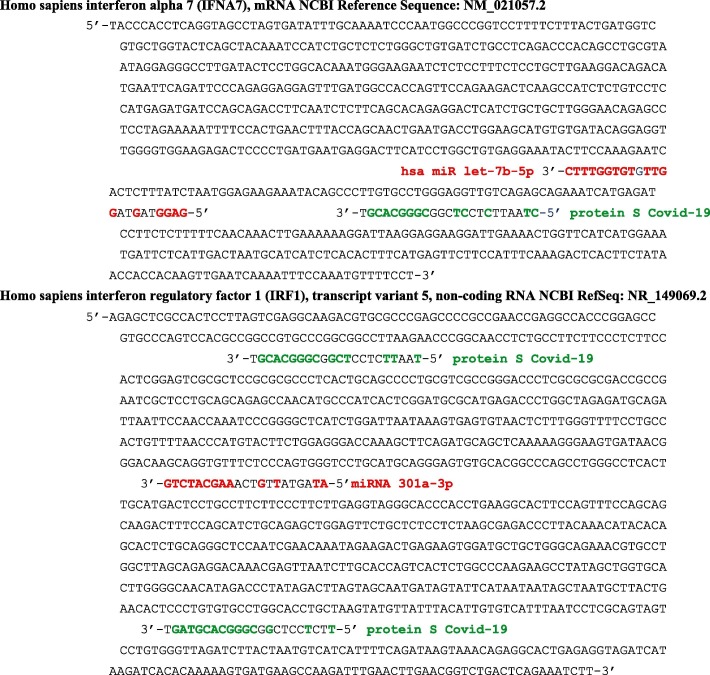

Fig. 10.

MiRNA-like subsequence of SARS-CoV-2 protein S gene (from its furin cleavage site) anti-matching sequences from the human type 1 interferon (IFNA7) or interferon regulatory factor (IRF1). In the first case, the sequence is the whole mRNA of IFNA7 and the probability to observe such an anti-match of length 8 by chance in a sequence of 730 nucleotides equals 0.04. In the second case, the sequence of the whole mRNA of IRF1 contains to targets and the probability to observe the last anti-match of length 11 by chance in a sequence of 1032 nucleotides equals 2 10-3. In red, miRNA inhibiting sequences [59], [60]. The probability to observe by chance the micro-RNA hsa miR let-7b-5p anti-match of length 9 in the first 730-length sequence equals 0.02 and the micro-RNA hsa miR 301a-3p anti-match of length 9 in the second 1032-length sequence equals 0.016. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The Table 1 presents the probability P and free energy ΔG (kcal/mol) of the anti-matches between human genes and protein S gene subsequences (TG and GT counting for ½), which are precisely described from Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11. All these probabilities are less than 5 10-2 showing the significance of the corresponding associations, which could be at the origin of the brakes observed on many metabolisms, thus explaining the ubiquitous and inconstant nature of the symptoms of COVID-19. They concern indeed many organs, in a sequence and with a duration difficult to anticipate, the cases observed ranging from asymptomatic or mildly affected patients to severe patients suffering from numerous chronic co-morbidities, the worsening of which due to COVID-19 leading sometimes to death.

Table 1.

Probability P and free energy ΔG (kcal/mol) of anti-matching between human genes and protein S gene subsequence (TG and GT counting for ½).

|

Conclusion

To conclude, the natural history of the SARS-CoV-2 virus remains widely unknown and it is still too early to say whether the many mutations observed will cause it to evolve in a favorable direction from a human point of view. There are for example some mutations surely deleterious [71], [72], but also others favoring the positive role of some human miRNAs against SARS-CoV-2 [73], [74], [75] suggesting a possible therapy. The present proposal of a miRNA-like mechanism would at least allow to see, for a predictive purpose, what mutations (depending for example on geoclimatic factors [76]) are keeping, losing or reinforcing its pathogenicity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jacques Demongeot: Writing - review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Hervé Seligmann: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Demongeot J., Flet-Berliac Y., Seligmann H. Temperature decreases spread parameters of the new SARS-CoV-2 cases dynamics. Biology (Basel) 2020;9:94. doi: 10.3390/biology9050094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demongeot J., Drouet E., Moreira A., Rechoum Y., Sené S. Micro-RNAs: viral genome and robustness of the genes expression in host. Phil Trans Royal Soc A. 2009;367:4941–4965. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandiera S., Matégot R., Demongeot J., Henrion-Caude A. MitomiRs: delineating the intracellular localization of microRNAs at mitochondria. Free Radical Biol Med. 2013;64:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demongeot J., Hazgui H., Bandiera S., Cohen O., Henrion-Caude A. MitomiRs, ChloromiRs and general modelling of the microRNA inhibition. Acta Biotheor. 2013;61:367–383. doi: 10.1007/s10441-013-9190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demongeot J., Cohen O., Henrion-Caude A. MicroRNAs and robustness in biological regulatory networks. A generic approach with applications at different levels: physiologic, metabolic, and genetic. Springer Series Biophys. 2013;16:63–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demongeot J., Hazgui H., Escoffier J., Arnoult C. Inhibitory regulation by microRNAs and circular RNAs. IFBME Proc. 2014;41:722–725. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demongeot J., Henrion C.A. The old and the new on the prebiotic conditions of the origin of life. Biology (Basel) 2020;9:88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demongeot J., Seligmann H. Comparisons between small ribosomal RNA and theoretical minimal RNA ring secondary structures confirm phylogenetic and structural accretion histories. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7693. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64627-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeffer S., Sewer A., Lagos-Quintana M., Sheridan R., Sander C., Grässer F.A. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods. 2005;2:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nmeth746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kincaid R.P., Burke J.M., Sullivan C.S. RNA virus microRNA that mimics a B-cell oncomiR. PNAS. 2012;109:3077–3082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116107109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen B.R. Viruses and microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38:S25–S30. doi: 10.1038/ng1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yekta S., Shih I.H., Bartel D.P. MicroRNA-directed cleavage of HOXB8 mRNA. Science. 2004;304:594–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1097434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennecke J., Stark A., Russell R.B., Cohen S.M. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macfarlane L.A., Murphy P.R. MicroRNA: biogenesis, function and role in cancer. Curr Genom. 2010;11:537–561. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li D., Dong H., Li S., Munir M., Chen J., Luo Y. Hemoglobin subunit beta interacts with the capsid protein and antagonizes the growth of classical swine fever virus. J Virol. 2013;87:5707–5717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03130-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W, Li H. SARS-COV-2 Attacks the 1-Beta Chain of Hemoglobin and Captures the Porphyrin to Inhibit Human Heme Metabolism. ChemRxiv Preprint 2020, https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.11938173.v5.

- 17.Sakuma T., Tonne J.M., Squillace K.A., Ohmine S., Thatava T., Peng K.W. Early events in retrovirus XMRV infection of the wild-derived mouse Mus pahari. J Virol. 2011;85:1205–1213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00886-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Fu Z., Liang H., Wang Y., Qi X., Ding M. H5N1 influenza virus-specific miRNA-like small RNA increases cytokine production and mouse mortality via targeting poly(rC)-binding protein 2. Cell Res. 2018;28:157–171. doi: 10.1038/cr.2018.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X. Composition of seed sequence is a major determinant of microRNA targeting patterns. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1377–1383. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broughton J.P., Lovci M.T., Huang J.L., Yeo G.W., Pasquinelli A.E. Pairing beyond the Seed Supports MicroRNA Targeting Specificity. Mol Cell. 2016;64:320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuccore. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NR_029482.1?report=fasta (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 22.Nuccore. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT446312.1?from=21561&to=25382& report=fasta (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 23.Nuccore. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_000184.3?report=fasta (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 24.Nuccore. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_000518.5?report=fasta (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 25.Genecards. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=HBB (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 26.Mirbase. Available online: http://www.mirbase.org/cgi-bin/mirna_entry.pl?acc=MI0000093 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 27.NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/msaviewer/?rid=BGU9FGPS114&coloring (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- 28.Xu P., Palmer L.E., Lechauve C., Zhao G., Yao Y., Luan J. Regulation of gene expression by miR-144/451 during mouse erythropoiesis. Blood. 2019;133:2518–2528. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018854604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu C., Xue J., Dang X. Detection of miR-144 gene in peripheral blood of children with β-thalassemia major and its significance. China Trop Med. 2010;10:285–286. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saki N., Abroun S., Soleimani M., Kavianpour M., Shahjahani M., Mohammadi-Asl J. MicroRNA expression in β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease: A role in the induction of fetal hemoglobin. Cell J. 2016;17:583–592. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2016.3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai K., Jia S., Yu S., Luo J., He Y. Genome-wide analysis of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs and miRNAs with associated co-expression and ceRNA networks in β-thalassemia and hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin. Oncotarget. 2017;8:49931–49943. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alizadeh S., Kaviani S., Soleimani M., Kouhkan F., Pourfathollah A.A., Amirizadeh N. Mir-155 downregulation by miRCURY LNA™ microRNA inhibitor can increase alpha chain hemoglobins expression in erythroleukemic K562 cell line. Int J Hematol-Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Changeux J.P., Amoura Z., Rey F., Miyara M. A nicotinic hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2 with preventive and therapeutic implications. CR Biol. 2020;343:33–39. doi: 10.5802/crbiol.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Follis K.E., York J., Nunberg J.H. Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell–cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology. 2006;350:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CNCB. Available online: https://bigd.big.ac.cn/ncov/variation/annotation/variant/24751 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- 36.Laderoute M.P., Larocque L.J., Giulivi A., Diaz-Mitoma F. Further evidence that human endogenous RetroVirus K102 is a replication competent foamy virus that may antagonize HIV-1 replication. Open AIDS J. 2015;9:112–122. doi: 10.2174/1874613601509010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holdt L.M., Kohlmaier A., Teupser D. Circular RNAs as therapeutic agents and targets. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1262. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang M., Yu F., Wu W., Zhang Y., Chang W., Ponnusamy M. Circular RNAs: A novel type of non-coding RNA and their potential implications in antiviral immunity. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:1497–1506. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.22531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panda A.C., Grammatikakis I., Kim K.M., De S., Martindale J.L., Munk R. Identification of senescence-associated circular RNAs (SAC-RNAs) reveals senescence suppressor CircPVT1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4021–4035. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghetti M., Vannini I., Storlazzi C.T., Martinelli G., Simonetti G. Linear and circular PVT1 in hematological malignancies and immune response: two faces of the same coin. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:69. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01187-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geier M.R., Geier D.A. Respiratory conditions in coronavirus disease 2019 (SARS-COV-2): Important considerations regarding novel treatment strategies to reduce mortality. Med Hypotheses. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Liu S.M., Yu X.H., Tang S.L., Tang C.K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (SARS-COV-2): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y., Ding Y.Y., Ren Y., Cao L., Xu Q.Q., Sun L. Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs in acute Kawasaki disease. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:932–938. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones V.G., Mills M., Suarez D., Hogan C.A., Yeh D., Bradley Segal J. SARS-COV-2 and Kawasaki disease: Novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:537–540. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@amdahl/SARS-CoV-2-debunking-the-hemoglobin-story-ce27773d1096 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- 46.Sun S., Cai X., Wang H., He G., Lin Y., Lu B. Abnormalities of peripheral blood system in patients with SARS-COV-2 in Wenzhou. China. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2020;507:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mardani R., Vasmehjani A.A., Zali F., Gholami A., Nasab S.D.M., Kaghazian H. Laboratory parameters in detection of SARS-COV-2 patients with positive RT-PCR; a diagnostic accuracy study. Archiv Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan L., Zhang H.T., Goncalves J., Xiao Y., Wang M., Guo Y. An interpretable mortality prediction model for SARS-COV-2 patients. Nature Machine Intell. 2020;2:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hassan T.H., Elbehedy R.M., Youssef D.M., Amr G.E. Protein C levels in β-thalassemia major patients in the east Nile delta of Egypt. Hemat Oncol Stem Cell Therapy. 2010;3:60–65. doi: 10.1016/s1658-3876(10)50036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lepik K., Annilo T., Kukuskina V., eQTLGen Consortium, Kisand K., Kutalik Z., Peterson P., Peterson H. C-reactive protein upregulates the whole blood expression of CD59 – an integrative analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(e1005766) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stower H. Circular sponges. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:238. doi: 10.1038/nrg3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Q., Honko A., Zhou J., Gong H., Downs S.N., Vasquez J.H. Cellular nanosponges inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Nano Lett. 2020;20:5570–5574. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stenvang J., Petri A., Lindow M., Obad S., Kauppinen S. Inhibition of microRNA function by antimiR oligonucleotides. Silence. 2012;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleming S.B. Viral inhibition of the IFN-induced JAK/STAT signalling pathway: development of live attenuated vaccines by mutation of viral-encoded IFN-antagonists. Vaccines. 2016;4:23. doi: 10.3390/vaccines4030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van den Broeke C., Jacob T., Favoreel H.W. Rho'ing in and out of cells: viral interactions with Rho GTPase signaling. Small GTPases. 2014;5 doi: 10.4161/sgtp.28318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spearman P. Viral interactions with host cell Rab GTPases. Small GTPases. 2018;9:192–201. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2017.1346552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hardy M.P., Owczarek C.M., Jermiin L.S., Ejdebäck M., Hertzog P.J. Characterization of the type I interferon locus and identification of novel genes. Genomics. 2004;84:331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samuel C.E. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Savan R. Post-transcriptional regulation of interferons and their signaling pathways. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014;34:318–329. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.miRBase. Available online: http://www.mirbase.org/cgi-bin/mirna_entry.pl?acc=MI0000063 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- 61.Pellerin L., Pellegri G., Bittar P.G., Charnay Y., Bouras C., Martin J.L. Evidence supporting the existence of an activity-dependent astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20:291–299. doi: 10.1159/000017324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.miRBase. Available online: http://www.mirbase.org/cgi-bin/mirna_entry.pl?acc=MI0000805 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- 63.Silvin A., Chapuis N., Dunsmore G., Goubet A.G., Dubuisson A., Derosa L. Elevated calprotectin and abnormal myeloid cell subsets discriminate severe from mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cordes F., Brückner M., Lenz P., Veltman K., Glauben R., Siegmund B. MicroRNA-320a strengthens intestinal barrier function and follows the course of experimental colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2341–2355. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basu A., Munir S., Mulaw M.A., Singh K., Herold B., Crisan D. A novel S100A8/A9 induced fingerprint of mesenchymal stem cells associated with enhanced wound healing. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24425-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jung N., Schenten V., Bueb J.L., Tolle F., Bréchard S. MiRNAs Regulate cytokine secretion induced by phosphorylated S100A8/A9 in neutrophils. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5699. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ebert M., Neilson J., Sharp P. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Varatharaj A., Thomas N., Ellul M.A., Davies N.W.S., Pollak T.A., Tenorio E.L. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of SARS-COV-2 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Unafold. Available online: http://unafold.rna.albany.edu/results2/twostate/200724/000229/ (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- 70.Unafold. Available online: http://unafold.rna.albany.edu/results2/twostate/200724/062836/ (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- 71.Yao H., Lu X., Chen Q., Xu K., Chen Y., Cheng L. Patient-derived mutations impact pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2. MedRxiv preprint. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.14.20060160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W. Spike mutation pipeline reveals the emergence of a more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv preprint. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.29.069054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rakhmetullina A., Ivashchenko A., Akimniyazova A., Aisina D., Pyrkova A. The miRNA Complexes Against Coronaviruses SARS-COV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Res Square preprint. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-20476/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ivashchenko A., Rakhmetullina A., Aisina D. How miRNAs can protect humans from coronaviruses SARS-COV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV. Res Square preprint. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-16264/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sadanand F., Bikash S., Ibrahim Y., Jin L.T., Ashok S., Ravindra K. SARS-COV-2 virulence in aged patients might be impacted by the host cellular MicroRNAs abundance/profile. Aging Disease. 2020;11:509–522. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seligmann H., Iggui S., Rachdi M., Vuillerme N., Demongeot J. Inverted covariate effects for mutated 2nd vs 1st wave Covid-19: high temperature spread biased for young. Biology (Basel) 2020;9:226. doi: 10.3390/biology9080226. 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]