Abstract

The ρ1 GABAA receptor is prominently expressed in the retina and is present at lower levels in several brain regions and other tissues. Although the ρ1 receptor is insensitive to many anesthetic drugs that modulate the heteromeric GABAA receptor, it maintains a rich and multifaceted steroid pharmacology. The receptor is negatively modulated by 5β-reduced steroids, sulfated or carboxylated steroids, and β-estradiol, whereas many 5α-reduced steroids potentiate the receptor. In this study, we analyzed modulation of the human ρ1 GABAA receptor by several neurosteroids, individually and in combination, in the framework of the coagonist concerted transition model. Experiments involving coapplication of two or more steroids revealed that the receptor contains at least three classes of distinct, nonoverlapping sites for steroids, one each for the inhibitory steroids pregnanolone (3α5βP), 3α5βP sulfate, and β-estradiol. The site for 3α5βP can accommodate the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC. The findings are discussed with respect to receptor modulation by combinations of endogenous neurosteroids.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The study describes modulation of the ρ1 GABAA receptor by neurosteroids. The coagonist concerted transition model was used to determine overlap of binding sites for several inhibitory and potentiating steroids.

Introduction

The ρ1 GABAA receptor is a member of the Cys-loop family of transmitter-gated ion channels. It is expressed at high levels in the retina where it modulates the processing of visual signaling (Lukasiewicz et al., 2004). Additionally, the ρ1 receptor has been detected in several brain regions, such as the hippocampus, superior colliculus, visual cortex, and cerebellum, and in the anterior pituitary gland, dorsal root ganglia, and the pancreatic islets (Wegelius et al., 1998; Rozzo et al., 2002; Maddox et al., 2004; Alakuijala et al., 2005; Nakayama et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2013).

The physiologic role of the ρ1 receptor in the brain is not fully understood, but the receptor is highly sensitive to GABA and shows little desensitization in the presence of ambient concentrations of GABA, making it well-suited to contribute to tonic inhibition (Amin and Weiss, 1994; Alakuijala et al., 2006). In rat pancreatic islets, locally released GABA can activate GABAA receptors, including those comprising ρ1 subunits, on the glucagon-releasing α-cells, thereby affecting glucose homeostasis (Jin et al., 2013). Activation of ρ receptors in the rat anterior pituitary cells has been shown to enhance the secretion of the luteotropic hormone prolactin associated with milk production (Nakayama et al., 2006). The ρ1 receptor has also been implicated in the behavioral effects of ethanol; single nucleotide polymorphisms in the GABRR1 gene encoding for the ρ1 subunit are significantly associated with early onset alcohol dependence (Xuei et al., 2010; Blednov et al., 2014). Modulation of ρ receptor function may have clinical significance. For example, intravitreal injections of the ρ1 inhibitors cis- and trans-(3-aminocyclopentanyl)butylphosphinic acid prevent the development of experimental myopia in the chick (Chebib et al., 2009).

The ρ1 receptor is structurally homologous to heteromeric αβγ and αβδ GABAA receptors but exhibits some notable pharmacological differences (Naffaa et al., 2017). It is insensitive to the competitive antagonist bicuculline and is not activated or modulated by pentobarbital (Shimada et al., 1992). The ρ1 receptor is also insensitive to volatile anesthetics and the intravenous anesthetic propofol (Mihic and Harris, 1996).

Many neurosteroids modulate the ρ1 receptor, in which case the configuration of the steroid at C5 determines the type of the effect. The ρ1 receptor is potentiated by 5α-reduced steroids, such as allopregnanolone and allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (5αTHDOC), but, unlike heteromeric GABAA receptors, is inhibited by 5β-reduced steroids, such as pregnanolone (3α5βP) (Morris et al., 1999; Goutman and Calvo, 2004). The ρ1 receptor is also inhibited by sulfated neurosteroids and the neurosteroid/sex hormone (8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-methyl-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol (β-estradiol) (Li et al., 2007; Eaton et al., 2014). The abundance of neurosteroids in the brain, coupled with the structural diversity of synthetic steroid analogs, raises the prospect for development of steroid-based clinical agents targeting the ρ receptor family. One weakness of this approach, however, has been the relatively low apparent affinity of the ρ1 receptor to many neurosteroids (Li et al., 2007). Hence, it would be beneficial to explore ways to lower the effective concentrations.

In recent work examining the actions of combinations of allosteric potentiators on the heteromeric GABAA receptor, we showed that the magnitude of effect strongly depends on whether the paired potentiators act through the same or distinct binding sites (Shin et al., 2019). This raises a possibility that combinations of neurosteroids or steroid analogs can be identified for employment at practical doses to modulate the ρ1 receptor. Here, we have examined the actions of several inhibitory and potentiating steroids on the human ρ1 receptor. The data, analyzed and interpreted in the framework of the coagonist concerted transition model (Forman, 2012; Ehlert, 2014; Steinbach and Akk, 2019), indicate that the inhibitory steroids 3α5βP, 3α5βP sulfate (3α5βPS), and β-estradiol (structures shown in Fig. 1) act by binding to distinct, nonoverlapping binding sites to independently modulate receptor function. Interestingly, the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC (Fig. 1) is shown to share a binding site with the inhibitory steroid 3α5βP, thereby presenting a case of divergent action for two steroids acting at the same site i.e., binding at overlapping sites elicits functionally opposite effects.

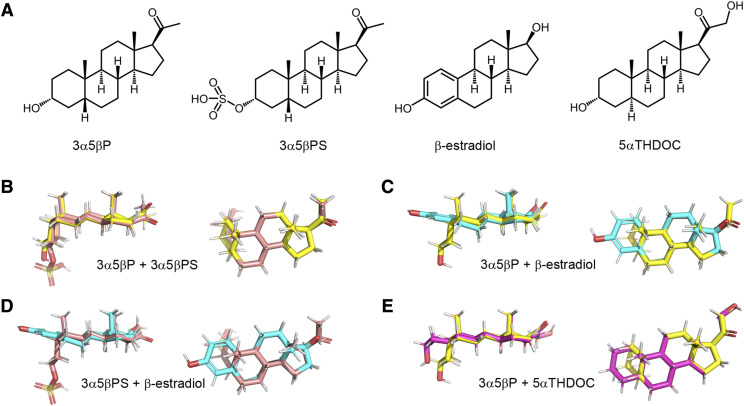

Fig. 1.

Steroid structures. (A) Chemical structures of 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, β-estradiol, and 5αTHDOC. (B) Overlay of 3α5βP (yellow) and 3α5βPS (pink). (C) Overlay of 3α5βP (yellow) and β-estradiol (cyan). (D) Overlay of 3α5βPS (pink) and β-estradiol (cyan). (E) Overlay of 3α5βP (yellow) and 5αTHDOC (magenta). The structures show strong similarities, as expected since the B, C, and D rings are identical, and all the C17 substituents are in the β configuration. The major differences concern the orientation of the A ring (5α vs. 5β fusion vs. the flattened extension of the unsaturated A ring of β-estradiol) and the presence of a bulky charged substituent on the sulfated steroid.

Materials and Methods

Receptors and Expression.

The human wild-type (GenBank Accession No. M62400) and mutant (I307Q) ρ1 GABAA receptors were expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Harvesting of oocytes was conducted under the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University in St. Louis (Approval No. 20170071).

The cDNA for the ρ1 subunit was subcloned into the pGEMHE expression vector in the T7 orientation and linearized with NheI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The ρ1 (I307Q) mutation was generated using QuikChange (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The complementary RNA was synthesized using mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Austin, TX). The oocytes were injected with 5 ng of complementary RNA per oocyte and incubated at 15°C in ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES; pH 7.4) with supplements (2.5 mM Na pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μg/ml gentamycin) for 1–3 days before conducting the electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiology.

The electrophysiological recordings were conducted at room temperature using the standard two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. The oocytes were clamped at −60 mV. The chamber (RC-1Z; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) was perfused with ND96 at the rate of 5–8 ml/min. Bath and drugs were gravity-applied from glass containers via Teflon tubing to the recording chamber (RC-1Z; Warner Instruments) at the rate of 5–8 ml/min.

The current responses were amplified with Axoclamp 900A (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) or OC-725C amplifiers (Warner Instruments), digitized with Digidata 1320 or 1200 series digitizers (Molecular Devices), and stored using Clampex (Molecular Devices). Analysis of the current traces was done using Clampfit (Molecular Devices).

The GABA concentration-response relationship was determined by exposing the oocytes to 0.1–10 μM GABA (seven concentration points). Constitutive activity was measured by comparing the effect of 100 μM picrotoxin to the peak response to saturating GABA. The effects of steroids were determined by exposing an oocyte to a low concentration (0.2–0.8 μM) of GABA for 1.5–3 minutes, followed by GABA + steroid (another 2 to 3 minutes), and washout in ND96. No desensitization of the current was observed during the application of low GABA. Each cell was also exposed to a reference solution containing a saturating concentration (10 μM) of GABA. Because of slow washout of the steroids, the steroid concentration-response relationships were determined by exposing each oocyte to a single concentration of steroid. The maximal steroid concentration was 50 μM because of limitations imposed by solubility in aqueous solution.

All experiments were conducted in an exploratory manner. The minimum number of replicates (i.e., cells tested per experimental condition) was five. The sample size was not set before data collection. All experimental observations are included (i.e., no data were excluded).

Data Analysis.

Descriptive analysis of current responses to GABA was aimed at determining the peak current amplitude. Initial characterization of the data was done by fitting the Hill equation to the GABA concentration-response data.

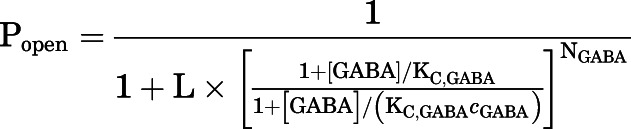

In the second step, the raw amplitudes of current traces were converted to units of open probability (Popen) by comparing a response amplitude to the response to saturating (10 μM) GABA in the same cell (Eaton et al., 2016). No adjustment for constitutive activity was done because of its negligible value (Popen, const = 0.0011; see below). No potentiation of the response to saturating GABA was observed during coapplication with the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC; accordingly, the response to 10 μM GABA had a Popen experimentally indistinguishable from one. The GABA concentration-Popen data were fitted to eq. 1:

|

(1) |

in which [GABA] is the concentration of GABA, KC,GABA is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the transmitter in the closed receptor, and cGABA is the ratio of the equilibrium dissociation constant for GABA in the open receptor to KC,GABA. NGABA, the number of transmitter binding sites, was constrained to five based on the 5-fold symmetry of the homomeric ρ1 receptor. The parameter L is a measure of unliganded gating that was calculated from the experimentally determined constitutive open probability (Popen, const) as:

| (2) |

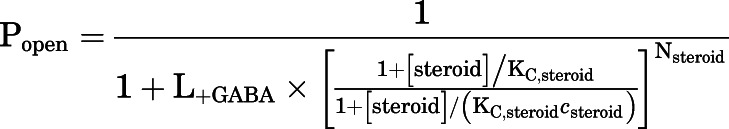

The effects of steroids on GABA-activated receptors were analyzed in the framework of the coagonist concerted transition model to estimate the affinities of the closed and open receptors to the steroid (Forman, 2012; Akk et al., 2018). The experimental concentration-response relationships were fitted to eq. 3:

|

(3) |

in which [steroid] denotes the concentration of steroid, KC,steroid is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the steroid in the closed receptor, and csteroid is the ratio of the equilibrium dissociation constant for steroid in the open receptor to KC,steroid. The number of steroid binding sites (Nsteroid) was constrained to five for all steroids. The parameter L+GABA is a measure of background activity in the presence of GABA calculated from experimental data as (1−Popen,+GABA)/Popen,+GABA. The K and c values are given as best-fit parameter ± S.E. of the fit from the analysis of averaged data from at least five cells. Curve fitting was carried out using Origin v. 7.5 (OriginLab, Northhampton, MA).

Studies of the effects of two simultaneously applied steroids were aimed at comparing the experimental observations with simulations based on two models. In the first model, in which the paired steroids interact with distinct, nonoverlapping sites, the effect of one steroid was considered to modify the value of L+GABA as follows:

| (4) |

in which L+GABA+steroid 1 is the modified L+GABA in the presence of GABA and steroid 1, and Popen, +GABA + steroid 1 is the open probability in the presence of GABA and that steroid. The predicted Popen for the steroid combination was then calculated with eq. 3 using the KC,steroid 2 and csteroid 2 values determined in the absence of steroid 1 and L+GABA+steroid 1 substituting for L+GABA. In this simulation, it is not critical which of the two paired steroids is considered steroid 1 that modifies L+GABA and which is considered steroid 2 whose effect at modified L+GABA (i.e., L+GABA+steroid) is examined. Switching the designation of modulators produces identical results (Shin et al., 2019).

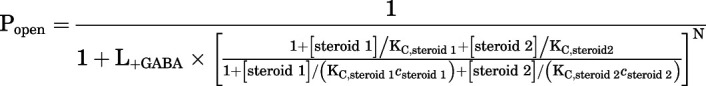

In the second model, we assumed that the two steroids compete for binding to the same site. In this case, the predicted Popen was calculated using eq. 5:

|

(5) |

in which steroid 1 and steroid 2 are the paired steroids, N is the number of shared sites (constrained to five), KC,steroid 1 and KC,steroid 2 are the equilibrium dissociation constants for steroid 1 and steroid 2 in the closed receptor, and csteroid 1 and csteroid 2 are the ratios of the equilibrium dissociation constants for the two steroids in the open receptor to KC,steroid 1 and KC,steroid 2, respectively. The equation can be expanded by adding more terms to the denominator to analyze the combined effect of more than two steroids. Note that in both of these models, the functional parameters for a given steroid were determined in the absence of other steroids.

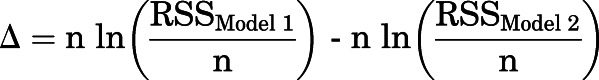

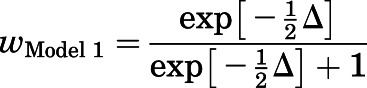

The results of modeling were compared by first calculating the difference in second-order Akaike information criterion scores of the two models:

|

(6) |

in which RSSModel 1 and RSSModel 2 are the residual sums of squares for the two models showing larger and smaller deviations from experimental data, respectively, and n is the number of cells. This was followed by determining Akaike weights for each model (w), which indicate the probability that a given model is the better model (Wagenmakers and Farrell, 2004; Burnham et al., 2011):

|

(7) |

in which wModel 1 is the probability that model 1 is the best model describing data. The probability of model 2 was then calculated as 1−wModel 1. The calculated w values rank the two chosen models without providing specific insight into an absolute best model.

Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking.

Because there are no known structures of the ρ1 GABAA receptor, it was necessary to develop a homology-based model of the receptor. We used the GABAA β3 homopentamer structure [PDB ID: 4COF; (Miller and Aricescu, 2014)] and the structure of the chimeric GLIC-α1 receptor bound with 5αTHDOC [PDB ID: 5OSB; (Laverty et al., 2017)] as templates. The sequence of the ρ1 subunit was modified by truncating the N terminus by removing residues 1–59 because none of the chosen templates had structural information for this region. The next modification was the replacement of the cytoplasmic loop (residues 371–453) with the sequence SQPARA (Jansen et al., 2008). Both of the template structures used had also replaced the cytoplasmic loop with this sequence. The ρ1 sequence was then aligned to the β3 and GLIC-α1 sequences using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). The sequence alignment of a single subunit is given in Supplemental Fig. 1. This alignment was used as the structural input for Modeler version 9 (Sali and Blundell, 1993). A total of 100 models were built and ranked by discrete optimized protein energy score (Shen and Sali, 2006). The top-ranked model (Supplemental Fig. 2) was deemed acceptable using the MolProbity server (Chen et al., 2010) and used for subsequent docking studies.

The model of the ρ1 GABAA receptor was read into the program Chimera (Meng et al., 2006) in which the structure was aligned with the 5αTHDOC-bound (PDB ID: 5OSB) and pregnenolone sulfate–bound structures [PDB ID: 5OSC; (Laverty et al., 2017)]. The bound neurosteroids in these structures were used to define the center of a docking box on each subunit (Supplemental Table 1). The docking boxes were set to be 20 × 20 × 20 Å allowing a large search volume. The intersubunit site (Hosie et al., 2006) was defined by the centroid of the bound 5αTHDOC molecules. The intrasubunit site near the top of the third and fourth membrane-spanning domains (Hosie et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2019) was defined as a centroid defined by residues A322, V329 on TM3 and F442, and I449 on TM4 (numbering in mature peptide). Lastly, the intrasubunit site for pregnenolone sulfate (Laverty et al., 2017) was defined as the centroid of the bound pregnenolone sulfates. The four neurosteroids were individually docked into the various sites using AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010). Docking scores are provided in the text. The best-scored docking poses of the four steroids in each of the three sites are given in Supplemental Figs. 3–5.

Superimposition of Neurosteroids.

Each of the four neurosteroids was aligned to a model of β-estradiol using the “pair alignment” function in the program PyMOL version 2.2.3 (Schrodinger, LLC). As all four neurosteroids share a common steroid backbone, 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and 5αTHDOC were initially aligned to β-estradiol. By aligning the six ring fusion carbons of β-estradiol to the corresponding carbons in the other steroids, the alignment function superimposes the steroid backbone as closely as possible given the different conformations of the A rings. The use of β-estradiol as the common reference automatically aligns the other steroids into a common orientation, as seen in Fig. 1.

Materials, Drugs, and Solutions.

The inorganic salts used in ND96, GABA, and picrotoxin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The steroids (3α5βP, 3α5βPS, β-estradiol, and 5α-THDOC) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich or Steraloids (Newport, RI). The stock solution of GABA was made in ND96 at 500 mM, stored in aliquots at −20°C, and diluted as needed on the day of experiments. The steroids were dissolved in DMSO at 10–50 mM and stored at room temperature (3α5βP, β-estradiol, 5αTHDOC) or at 5°C (3α5βPS).

Results

Analysis of the ρ1 Receptor Activation by GABA.

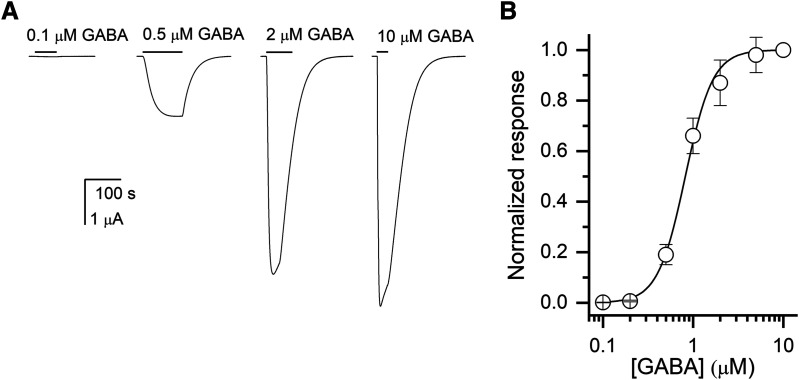

We recorded the GABA concentration-response relationship by exposing oocytes expressing human ρ1 receptors to 0.1–10 μM GABA. Fitting the Hill equation to the concentration-response data yielded an EC50 of 0.82 ± 0.09 μM (mean ± S.D.; n = 5 cells) and a Hill coefficent of 2.85 ± 0.45. These are similar to the values reported previously (Amin and Weiss, 1996; Chang and Weiss, 1998; Li et al., 2006). Sample currents and the GABA concentration-response curve are given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Activation of the ρ1 wild-type receptor by GABA. (A) Sample current responses to applications of 0.1, 0.5, 2, or 10 μM GABA. The bars indicate the durations of applications of GABA. The applications of GABA were followed by 2–4 minutes washes in ND96. (B) The GABA concentration-response relationship from oocytes exposed to 0.1–10 μM GABA. The current amplitudes were normalized to the response to 10 μM in the same cell. The data points show mean ± S.D. from five cells. The concentration-response data from each cell were fitted separately yielding an EC50 of 0.82 ± 0.09 μM (mean ± S.D.) and an nHill of 2.85 ± 0.45. The curve shows a calculated concentration-response relationship based on the mean EC50 and nHill.

Next, we converted the current amplitudes to units of open probability (Popen). To that end, the current amplitudes were matched with estimated Popen of constitutive activity and that of the peak response to saturating GABA (Eaton et al., 2016). To evaluate the level of constitutive open probability, we compared the effects of 100 μM picrotoxin, which inhibits constitutively active receptors, and the saturating concentration (10 μM) of GABA. In 14 cells, picrotoxin elicited apparent outward current with the mean amplitude of 0.106% ± 0.037% of the peak response to saturating GABA. To estimate the open probability elicited by saturating GABA, we probed the ability of the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC (Morris et al., 1999; Li et al., 2007) to potentiate the response to the transmitter. In this approach, it is assumed that coapplication of a potentiator with saturating GABA elicits a response with Popen near one that enables, by comparison of the peak responses, determination of the Popen of response to GABA in the absence of potentiator (Forman, 2012; Eaton et al., 2016). In five cells, no enhancement of the current response was observed when 25–50 μM 5αTHDOC was coapplied with saturating GABA. Furthermore, coapplication of 1 mM amiloride hydrochloride hydrate, a known potentiator of the ρ1 receptor (Snell and Gonzales, 2015), also did not enhance the peak or steady-state responses to saturating GABA. These observations suggest that the Popen of the ρ1 receptor in the presence of saturating GABA is high and experimentally indistinguishable from one. We thus estimated that the Popen of constitutive activity was 0.0011 and, using eq. 2, calculated a value for L of 1018 ± 244 (n = 14).

To gain further insight into the activation properties of the ρ1 receptor, we normalized the current responses to the peak response to 10 μM GABA. The Popen in the presence of 10 μM GABA was constrained to values between 0.92 and 0.999, and the concentration-Popen relationships were fitted with eq. 1. Essentially, we reasoned that a small (less than 8%) potentiating effect of 5αTHDOC might be masked by experimental imprecision and that the true Popen of the ρ1 receptor in the presence of 10 μM GABA falls within the range of 0.92–0.999.

The fitting results, summarized in Table 1, provide a plausible range of KGABA (affinity of the resting receptor to GABA) and cGABA values (a measure of GABA efficacy) for the human ρ1 receptor. The estimates for KGABA ranged from 1.1 μM (with the Popen of the peak response to 10 μM GABA constrained to 0.92) to 2.1 μM (with Popen fixed at 0.999). The estimated cGABA ranged from 0.085 to 0.128, corresponding to the binding of five GABA molecules providing 6.1–7.3 kcal/mol toward stabilization of the open state. In each case, the value of L was adjusted to take into consideration the altered ratio of the response to picrotoxin to the hypothetical response with Popen of 1.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of activation of the ρ1 receptor by GABA

The table gives the results of fitting the GABA conc.-Popen response data to eq. 1. The first column shows the constrained value of Popen at 10 μM GABA. The next columns show the calculated value of L and the fitted values of KC and c (best-fit parameter ± S.D.). The number of binding sites for GABA was constrained to 5.

| Popen at 10 μM GABA | L | KC (μM) | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.999 | 1018 | 2.11 ± 0.46 | 0.085 ± 0.012 |

| 0.98 | 1039 | 1.73 ± 0.33 | 0.097 ± 0.011 |

| 0.96 | 1060 | 1.44 ± 0.26 | 0.110 ± 0.010 |

| 0.94 | 1083 | 1.24 ± 0.21 | 0.119 ± 0.010 |

| 0.92 | 1106 | 1.09 ± 0.19 | 0.128 ± 0.009 |

In subsequent experiments examining the effects of steroids on responses to a low concentration of GABA, the peak response to 10 μM GABA was used as the “reference” response, which was assumed to have an open probability of one. This introduced a potential error in the estimates of Popen in these experiments. The extent of the error was established by assigning different values of Popen to the peak response to saturating GABA (see below).

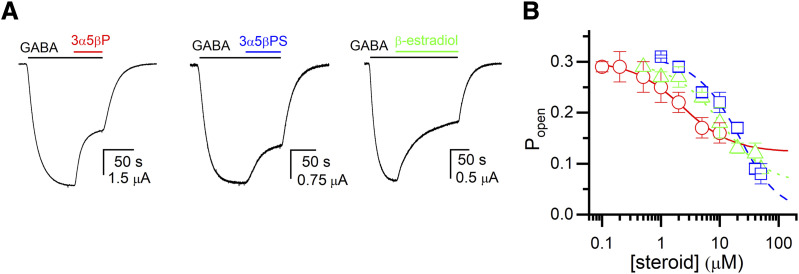

Receptor Inhibition by the Steroids 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-Estradiol.

Inhibition of the ρ1 GABAA receptor by neurosteroids has been reported previously (Morris et al., 1999; Li et al., 2007; Eaton et al., 2014). Here, we analyzed the inhibitory effects of the steroids 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-estradiol on the ρ1 receptor in the framework of the coagonist concerted transition model. Current responses were recorded in the presence of 0.4–0.8 μM GABA (Popen ∼0.3) in the absence and presence of 0.1–50 μM steroid. Additionally, each cell was probed by application of a saturating concentration (10 μM) of GABA, initially assumed to generate a peak response with Popen of 0.999 (see Materials and Methods for more details). Analysis of the currents using eq. 3 yielded a K3α5βP of 2.85 ± 0.62 μM and a c3α5βP of 1.25 ± 0.02, a K3α5βPS of 51.1 ± 25.3 μM and a c3α5βPS of 2.34 ± 0.89, and a Kβ-Estradiol of 16.4 ± 4.8 μM and a cβ-Estradiol of 1.47 ± 0.07. The number of binding sites was held at five for each steroid. The data and the fitted curves are shown in Fig. 3. We note that incomplete inhibition, as predicted by eq. 3, has been observed previously for the ρ1 receptor exposed to 3α5βP (Morris et al., 1999; Li et al., 2007).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of the ρ1 wild-type receptor by neurosteroids. (A) Sample current responses to 0.4–0.8 μM GABA (Popen ∼0.3) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 10 μM 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, or β-estradiol. The bars above the traces indicate the durations of applications of GABA and the steroids. (B) The graph shows the steroid concentration-Popen relationships for 3α5βP (circles and solid line), 3α5βPS (squares and dashed line) or β-estradiol (triangles and dotted line). The data points show mean ± S.D. from five to seven cells at each experimental condition. The curves were generated by fitting eq. 2 to the pooled data. The best-fit parameters for 3α5βP are: KC = 2.85 ± 0.62 μM, c = 1.25 ± 0.02. The best-fit parameters for 3α5βPS are: KC = 51.1 ± 25.3 μM, c = 2.34 ± 0.89. The best-fit parameters for β-estradiol are: KC = 16.4 ± 4.8 μM, c = 1.47 ± 0.07.

The inhibitory properties of the steroids were also determined by assuming that the response to 10 μM GABA had a peak Popen of 0.92. This was done to estimate the extent of potential error introduced by initially assigning a Popen of 0.999 to the reference response. The estimated values of Ksteroid and csteroid then were 2.44 ± 0.43 μM and 1.23 ± 0.02, respectively, for 3α5βP, 66.5 ± 37.6 μM and 3.06 ± 2.24 for 3α5βPS, and 14.8 ± 4.2 μM and 1.42 ± 0.06 for β-estradiol. We infer that the precise Popen of the reference response has an acceptably small effect (nominally up to 30%) on the estimated properties of the steroids.

The value of the parameter c, which characterizes the degree to which the steroid prefers a closed receptor over the open receptor, ranged from 1.25 for 3α5βP to 2.34 for 3α5βPS. Thus, the binding of steroid contributes 0.7–2.5 kcal/mol free energy toward stabilizing the closed state.

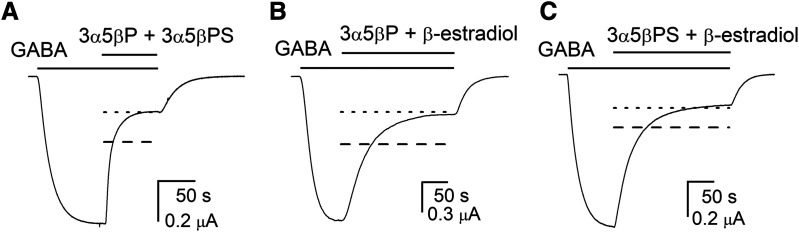

The Effects of Coapplication of Multiple Inhibitory Steroids.

A prior study comparing the effects of mutations in the second membrane-spanning domain on the ability of steroids to inhibit the ρ1 receptor found that the mutations differently affected inhibition by various steroids. Specifically, it was proposed that the steroids 3α5βP, 3α5βPS and β-estradiol interact with distinct, nonoverlapping sites (Li et al., 2007). This was indirectly confirmed by Eaton et al. (2014), who showed that these steroids elicit unique conformational changes in the extracellular domain of the receptor. Here, we employed the coagonist concerted transition model to investigate overlap between the steroid binding sites. To that end, we coapplied two or more inhibitory steroids and measured the net effect of the steroid combination on the amplitude of current generated by a low concentration of GABA (Popen ∼0.35). The experimental observations were compared with the predicted open probabilities calculated using models in which the paired steroids interact to produce a larger functional effect, which we interpret as reflecting independent binding to sites that are physically distinct (eqs. 3 and 4), or interact to produce a smaller functional effect, which we interpret as reflecting mutual prevention of simultaneous binding to a shared, overlapping site (eq. 5).

Coapplication of 3α5βP and 3α5βPS strongly inhibited the response to GABA. In seven cells, the application of 0.5–0.6 μM GABA elicited a response with Popen of 0.31 ± 0.09. Coapplication of 10 μM 3α5βP and 20 μM 3α5βPS with GABA reduced the Popen of the response to 0.08 ± 0.03. The predicted open probability of the response, assuming five shared sites for the two steroids, was 0.14 ± 0.05, whereas the predicted Popen, assuming that the steroids act through nonoverlapping sites, was 0.08 ± 0.03. Sample current traces along with the predicted current levels for the two models are shown in Fig. 4A.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of the ρ1 wild-type receptor by combinations of neurosteroids. Sample current responses to 0.4–0.8 μM GABA (Popen ∼0.3) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 10 μM 3α5βP + 20 μM 3α5βPS (A), GABA + 10 μM 3α5βP + 20 μM β-estradiol (B), or GABA + 20 μM 3α5βPS + 20 μM β-estradiol (C). The bars above the traces indicate the durations of applications of the drugs. The dashed and dotted lines show theoretical current levels simulated by the models assuming same or distinct binding sites, respectively, for the paired steroids.

To provide quantitative insight into the goodness of fit for the two models, we calculated the Akaike weights for the shared site and the distinct site models. The Akaike weight (w) for a particular model expresses the probability or likelihood of the model among those considered (Wagenmakers and Farrell, 2004; Burnham et al., 2011). A value of w closer to one supports the idea that a given model gives a better description of the data. For the 3α5βP + 3α5βPS pair, the wshared sites was <10−11 and wdistinct sites was 1–10−11. We infer that a model with distinct sites for 3α5βP and 3α5βPS is better supported by experimental observations.

Next, we examined the combined effect of 3α5βP and β-estradiol (Fig. 4B). Coapplication of 10 μM 3α5βP and 20 μM β-estradiol inhibited the response to GABA. The Popen was 0.37 ± 0.07 (n = 7 cells) in the absence of the two steroids and 0.09 ± 0.02 in the presence of the two steroids. The predicted Popen, assuming the steroids acted through same sites, was 0.17 ± 0.05 (w ∼10−9) and different sites 0.09 ± 0.03 (w = 1–10−9).

Combination of 20 μM 3α5βPS and 20 μM β-estradiol reduced the open probability of the response to GABA from 0.35 ± 0.09 (n = 15 cells) to 0.08 ± 0.02 (Fig. 4C). Assuming that 3α5βPS and β-estradiol act through the same site, the predicted open probability in the presence of GABA and the two steroids was 0.13 ± 0.04 (w < 10−10). The predicted open probability predicted by the model with different sites for the two steroids was 0.08 ± 0.02 (w = 1–10−10).

Finally, we coapplied the triple combination of 5 μM 3α5βP, 10 μM 3α5βPS, and 10 μM β-estradiol with GABA. The Popen of the control response to GABA alone was 0.37 ± 0.02 (n = 6 cells). In the presence of GABA plus the three steroids, the open probability was 0.071 ± 0.010. The calculated Popen for the model with the same set of five binding sites mediating the effects of the three steroids was 0.17 ± 0.01 (w ∼10−9). Assuming different binding sites for each steroid, the calculated Popen was 0.086 ± 0.007 (w = 1–10−9).

We infer from these experiments that 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-estradiol inhibit the ρ1 receptor through interactions with distinct, nonoverlapping binding sites. These findings are in agreement with previous studies employing mutational and fluorometric approaches (Li et al., 2007; Eaton et al., 2014).

Receptor Potentiation by 5αTHDOC and the Effects of Inhibitory Steroids on Potentiation.

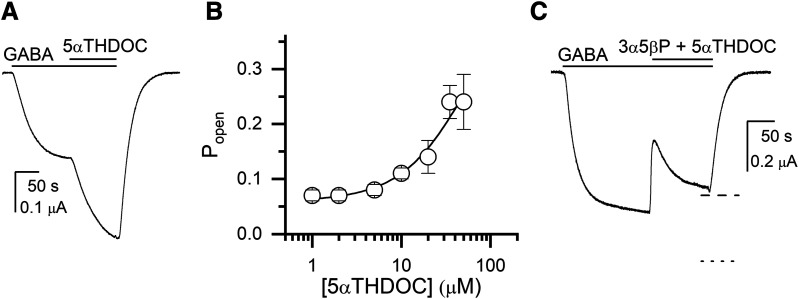

The ρ1 receptor is potentiated by 5α-reduced steroids (Morris et al., 1999). Here, we analyzed the potentiating effect of the steroid 5αTHDOC by coapplying 1–35 μM steroid with 0.2 μM GABA (Popen of 0.04–0.08). Analysis of the currents (five to six cells at each steroid concentration) using eq. 1 yielded a K5αTHDOC of 38.2 ± 28.6 μM and a c5αTHDOC of 0.58 ± 0.07. The number of steroid binding sites was constrained to five. A sample current trace and the steroid concentration-response curve are given in Fig. 5, A and B.

Fig. 5.

Potentiation of the ρ1 wild-type receptor by 5αTHDOC in the absence and presence of the inhibitory steroid 3α5βP. (A) A sample current response to 0.2 μM GABA (Popen = 0.05) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 20 μM 5αTHDOC. The bars above the traces indicate the durations of applications of the drugs. (B) The graph shows the 5αTHDOC concentration-Popen relationship. The data points show mean ± S.D. from five to six cells at each experimental condition. The curve was generated by fitting eq. 2 to the pooled data. The best-fit parameters are: KC,5αTHDOC = 38.2 ± 28.6 μM, c5αTHDOC = 0.58 ± 0.07. (C) A sample current response to 0.35 μM GABA (Popen = 0.10) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 20 μM 5αTHDOC + 10 μM 3α5βP. The biphasic effect upon the application of steroids is likely due to a rapidly developing inhibitory effect of 3α5βP followed by a more slowly developing potentiating effect of 5αTHDOC. The dashed and dotted lines show theoretical current levels simulated by the models assuming same or distinct binding sites, respectively, for 5αTHDOC and 3α5βP.

Examination of the effect on receptor function resulting from coapplication of 5αTHDOC with an inhibitory steroid can be used to determine whether the paired steroids interact with the same or distinct sites. The approach is analogous to that described above for combinations of inhibitory steroids in which the difference in predicted Popen values from the two models compared with experimental results enabled determination of the better model. For combinations of 5αTHDOC plus an inhibitory steroid, a reasonable separation between the two predicted Popen values was obtained only for 3α5βP, whereas for the 5αTHDOC + 3α5βPS and 5αTHDOC + β-estradiol combinations the two models predicted experimentally indistinguishable Popen values at steroid concentrations less than 50 µM.

Coapplication of the combination of 20 μM 5αTHDOC + 10 μM 3α5βP with 0.35 μM GABA decreased the steady-state Popen from 0.11 ± 0.03 to 0.09 ± 0.03 (n = 8 cells). The predicted Popen, assuming that different binding sites mediate the actions of the two steroids, was 0.14 ± 0.04 (w = 10−8) whereas the predicted Popen from the same site model was 0.09 ± 0.03 (w = 1–10−8). We infer that 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC act through overlapping sites.

A sample trace showing the effect of 5αTHDOC + 3α5βP is shown in Fig. 5C. Note that the steroid effect is biphasic: a rapid inhibition is followed by a slow increase in current level. We propose that the initial inhibition reflects the more rapidly developing effect of 3α5βP (e.g., as apparent in Fig. 3B), whereas the second, recovery phase represents the more slowly developing potentiation by 5αTHDOC (e.g., Fig. 5A).

Effect of the I307Q Mutation on Receptor Modulation by Potentiating and Inhibitory Steroids.

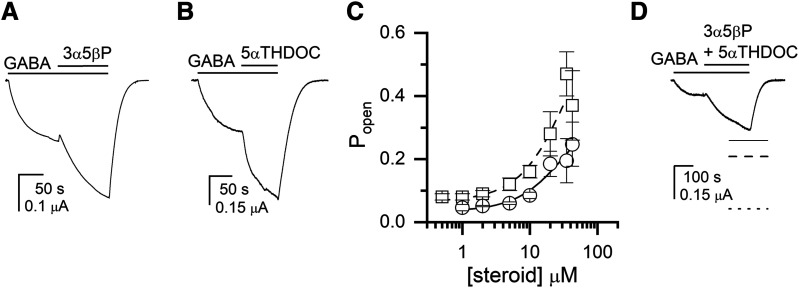

The isoleucine-to-glutamine mutation at position 307 (15′ residue in the second membrane-spanning domain) in the ρ1 receptor switches the effect of 3α5βP from inhibition to potentiation (Morris and Amin, 2004; Eaton et al., 2014). The underlying mechanism for this switch is not clear. One possibility is that the mutation modifies the nature of the postulated site for 3α5βP and/or steroid interactions with the site. Alternatively, the I307Q mutation may unmask a novel site that mediates potentiation by 3α5βP, potentially by abolishing the actions of 3α5βP at the conventional inhibitory site. To attempt to distinguish between these possibilities, we examined modulation of the ρ1(I307Q) receptor by 3α5βP, 5αTHDOC, and the combination of the two steroids. We reasoned that if the mutation converts the existing site to potentiating for 3α5βP, then receptor behavior in the presence of 3α5βP + 5αTHDOC will continue to be described by a model in which the steroids compete for a shared site (eq. 5).

Coapplication of 3α5βP with 0.11–0.15 μM GABA (Popen ∼0.04) resulted in potentiation of the current response (Fig. 6A). Analysis of the responses using eq. 2 yielded a K3α5βP of 20.5 ± 15.1 μM and a c3α5βP of 0.55 ± 0.05. Coapplication of 5αTHDOC with 0.1–0.2 μM GABA (Popen ∼0.07) also potentiated the response to GABA (Fig. 6B). Curve fitting of the concentration-Popen data yielded a K5αTHDOC of 28.6 ± 26.1 μM and a c5αTHDOC of 0.49 ± 0.08. These values are similar to the K and c in the wild-type receptor, indicating that the mutation minimally affects potentiation by 5αTHDOC. The concentration-Popen relationships are shown in Fig. 6C.

Fig. 6.

Potentiation of the ρ1(I307Q) receptor by 3α5βP, 5αTHDOC, and the combination of the two steroids. (A) A sample current response to 0.11 μM GABA (Popen = 0.05) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 10 μM 3α5βP. The bars above the traces indicate the durations of applications of the drugs. (B) A sample current response to 0.2 μM GABA (Popen = 0.1) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 10 μM 5αTHDOC. (C) The graph shows the steroid concentration-Popen relationships for 3α5βP (circles and solid line) and 5αTHDOC (squares and dashed line). The data points show mean ± S.D. from five to six cells at each experimental condition. The curves were generated by fitting eq. 2 to the pooled data. The best-fit parameters for 3α5βP are: KC = 20.5 ± 15.1 μM, c = 0.55 ± 0.05. The best-fit parameters for 5αTHDOC are: KC = 28.6 ± 26.1 μM, c = 0.49 ± 0.08. (D) A sample current response to 0.15 μM GABA (Popen = 0.03) followed by a coappplication of GABA + 10 μM 3α5βP + 10 μM 5αTHDOC. The dashed and dotted lines show theoretical current levels simulated by the models assuming same or distinct binding sites, respectively, for 5αTHDOC and 3α5βP. The solid line shows the estimated steady-state response level in the presence of GABA + 3α5βP + 5αTHDOC from the fit of a single exponential function.

Coapplication of the combination of 10 μM 3α5βP + 10 μM 5αTHDOC potentiated the response to GABA (Fig. 5D). The Popen was 0.05 ± 0.03 (n = 7 cells) in the presence of GABA and 0.14 ± 0.07 in the presence of GABA plus the two steroids. The predicted Popen, assuming that 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC bind to different sites, was 0.33 ± 0.16 (w = 0.00002). The predicted Popen for the same site model was 0.21 ± 0.12 (w = 0.99998). We infer that 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC interact with overlapping sites and propose that the I307Q mutation alters the direction of effect of 3α5βP rather than generating a new binding site for the steroid. This idea is also supported by the finding that the I307S substitution enables potentiation of the ρ1 receptor by the structurally unrelated pentobarbital (Belelli et al., 1999).

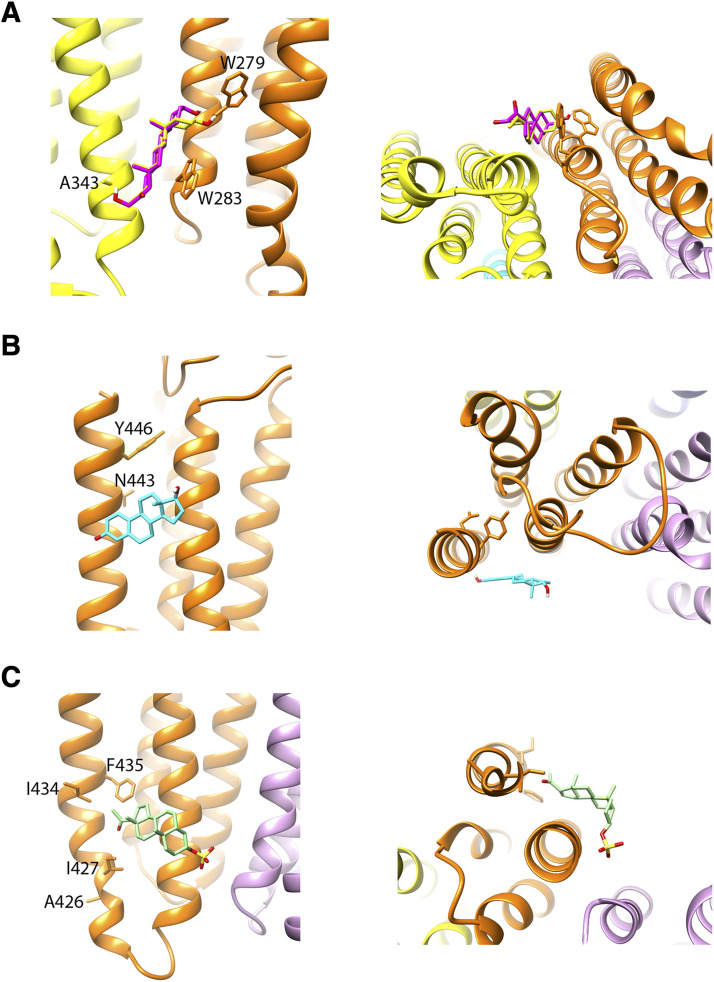

Homology Modeling and Docking of Steroids in Putative Binding Sites.

Two binding sites for neurosteroids have been identified in bacterial-GABAA chimeric subunits: an intersubunit site between the first and third membrane-spanning domains of neighboring subunits for potentiating steroids, such as 5αTHDOC and 3α5βP, and an intrasubunit site lined by the third and fourth membrane-spanning domains for the inhibitory steroid pregnenolone sulfate (Laverty et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017). In the heteromeric α1β3 receptor, analogs of potentiating steroids additionally label intrasubunit sites near the interface between membrane-spanning and extracellular domains in the α1 and β3 subunits (Chen et al., 2019). It is conceivable that homologous sites in the ρ1 receptor mediate the modulatory effects of the tested steroids.

We generated a homology model of the ρ1 receptor based on the published structures of β3 and GLIC-α1 homomeric structures (Miller and Aricescu, 2014; Laverty et al., 2017) and docked 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, β-estradiol, and 5αTHDOC in each of the three putative binding sites for steroids. The docking scores, determined using AutoDock Vina software, indicate only small (up to 1 kcal/mol) differences for the four steroids in each of the binding sites. At the intersubunit site (Hosie et al., 2006), the ranking of docking scores was: 3α5βPS (−8.6 kcal/mol) > 3α5βP (−8.2 kcal/mol) > β-estradiol (−7.8 kcal/mol) > 5αTHDOC (−7.6 kcal/mol). At the intrasubunit site near the interface between membrane-spanning and extracellular domains (Hosie et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2019), the docking scores were: 3α5βP (−7.1 kcal/mol) > β-estradiol (−6.9 kcal/mol) > 3α5βPS (−6.8 kcal/mol) > 5αTHDOC (−6.6 kcal/mol). At the intrasubunit site originally identified for the inhibitory steroid pregnenolone sulfate (Laverty et al., 2017), the docking scores were: β-estradiol (−7.7 kcal/mol) > 3α5βP (−7.4 kcal/mol) > 3α5βPS (−7.0 kcal/mol) > 5αTHDOC (−6.9 kcal/mol). The structures of binding sites with docked steroids are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Docking of steroids in putative binding sites. (A) The panels show a side view (left panel) and a view from the intracellular side of the receptor (right panel) at the putative intersubunit binding site for steroids (Hosie et al., 2006) with 3α5βP (yellow) and 5αTHDOC (magenta) docked in the site. The residues shown are W279 (corresponding to Q241 in α1), W283 (α1W245), and A343 (corresponds to T305 in the α1 or F301 in the β3 subunit) that have been implicated in the effects of potentiating steroids in the heteromeric GABAA receptor (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2012). (B) The panels show a side view (left panel) and a view from the extracellular side of the receptor (right panel) at the putative intrasubunit binding site for potentiating steroids (Chen et al., 2019). The steroid β-estradiol is shown in the site. The residues shown are N443 and Y446 that correspond to N407 and Y410, respectively, in the α1 subunit and have been implicated in the actions of potentiating steroids in the heteromeric GABAA receptor (Hosie et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009). (C) The panels show a side view (left panel) and a view from the intracellular side of the receptor (right panel) at the putative intrasubunit binding site for inhibitory steroids (Laverty et al., 2017). The steroid 3α5βPS is shown in the site. The residues shown are A426, I427, I434, and F435 that correspond to K390, I391, I398, and F399, respectively, in the α1 subunit and have been shown to inhibit the actions of pregnenolone sulfate in the GLIC-α1 receptor (Laverty et al., 2017). The selection of docked steroids in (A–C) was not based on best docking scores (see Results) but rather on analogy with the presumed steroid selectivity in the heteromeric GABAA receptor.

Discussion

We implemented the coagonist concerted transition model to analyze the activation of the human ρ1 GABAA receptor by the transmitter GABA and modulation of GABA-activated receptors by structurally related inhibitory and potentiating neurosteroids (Fig. 1) and combinations of neurosteroids. The data indicate that the GABA equilibrium dissociation constant in the resting receptor is 1.1–2.1 μM and that the binding of five GABA molecules contributes 6.1–7.3 kcal/mol free energy toward stabilization of the open state. A range, rather than a precise estimate, is due to the lack of an exact value for maximal open probability in the presence of GABA. In macroscopic recordings, the maximal Popen for a given agonist is typically determined by comparing a response to a saturating concentration of the agonist with a reference response to a combination of the agonist and a potentiator. The latter is assumed to generate a response with Popen indistinguishable from one. Here, coapplication of the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC with saturating GABA was without effect on the peak response, suggesting that the maximal Popen for GABA in the ρ1 receptor is near one. The absence of other suitable allosteric potentiators (Belelli et al., 1999) or orthosteric or allosteric agonists more efficacious than GABA (Chang et al., 2000) did not allow for a more precise estimate. The ambiguity in maximal Popen for GABA affects the estimated Popen values in Figs. 2, 3, and 5. Our calculations indicate that the resulting fitted values of Ksteroid and csteroid would differ from those presented in Table 2 by <30%.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of modulation of the ρ1 receptor by steroids

The table summarizes the results of fitting the steroid conc.-Popen response data from ρ1 wild-type and I307Q mutant receptors to eq. 2. The experiments were conducted in the presence of GABA, and L was calculated as (1−Popen,GABA)/Popen,GABA. The number of binding sites for steroids was constrained to five, and the maximal Popen for GABA was assumed to be 0.999.

| Receptor | Steroid | KC (μM) | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| ρ1 wild-type | 3α5βP | 2.85 ± 0.62 | 1.25 ± 0.02 |

| 3α5βPS | 51.1 ± 25.3 | 2.34 ± 0.89 | |

| β-Estradiol | 16.4 ± 4.8 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | |

| 5αTHDOC | 38.2 ± 28.6 | 0.58 ± 0.07 | |

| ρ1(I307Q) | 3α5βP | 20.5 ± 15.1 | 0.55 ± 0.05 |

| 5αTHDOC | 28.6 ± 26.1 | 0.49 ± 0.08 |

The findings indicate that the ρ1 GABAA receptor contains at least three classes of distinct, nonoverlapping sites for neurosteroids. There is one class of sites for both of the inhibitory neurosteroids 3α5βP and 3α5βPS and the neurosteroid/sex hormone β-estradiol. The site for 3α5βP can alternatively bind the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC. From the 5-fold symmetry of the homomeric ρ1 receptor, and for simplicity, we have assumed that there are five sites of each class in the receptor.

Our definition of distinct versus overlapping sites is based on functional effects of combinations of steroids, using parameters for steroid effects obtained in studies of one steroid in the absence of others. In the case of postulated distinct binding sites (3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-estradiol), we have shown that when used in combination, each steroid acts independently, and there is no indication that the binding of one steroid modifies the effect of another except through energetic additivity. This lack of interaction between the two steroid molecules, other than one mediated by stabilization of particular states of the receptor, is incompatible with the physical prevention by one steroid of access of the other to a binding site on the receptor. This, in turn, precludes the possibility that the interaction of the steroids with the receptor requires that the steroids associate with the same residues in the receptor or a shared subset of the residues.

In the case of postulated overlapping binding sites (3α5βP and 5αTHDOC), we have shown that in combination the two steroids display competitive interaction. For simplicity, and because of mutational and structural evidence that 5α- and 5β-reduced steroids act through a common site in heteromeric (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2019) and α-homomeric GABAA receptors (Laverty et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018), we have assumed that 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC compete for a shared site. We cannot, however, exclude a possibility that the two steroids bind to distinct but allosterically linked sites in the ρ1 receptor. We also note that the electrophysiological experiments provide no evidence about the actual physical location of the sites and also do not define the extent of overlap in the case of 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC or other details, such as the orientation of the bound steroids in the postulated site.

We tested the possibility that the three sites for potentiating and inhibitory steroids previously identified in the α1 subunit or the α1β3 receptor (Laverty et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019) also mediate the actions of 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, β-estradiol, and 5αTHDOC in the ρ1 receptor. Docking of the steroids to homologous sites in a model generated using β3 and GLIC-α1 crystal structures, however, indicated little selectivity for different steroids. The docking scores were within 1 kcal/mol at each individual site and within 2 kcal/mol across all the steroid-site pairs. Although the estimated energies were similar, the poses of the docked steroids at a given site could vary even to the extent of having reversed orientations (see Supplemental Information). However, it was not possible to interpret the poses in terms of functional consequences since the homology model was built based on structures corresponding to the desensitized receptor, whereas the coagonist concerted transition model assumes that ligands have distinct affinities to different states. Thus, an inhibitory steroid, such as 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, or β-estradiol, is expected to have higher affinity to the resting or desensitized state, depending on the mechanism of inhibition, than the open state, whereas the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC has higher affinity to the open state. In the present analysis, we have assumed that the inhibitory steroids act by stabilizing the resting state. In future work, once appropriate structures become available, it will be interesting to compare docking with different functional states. Alternatively, the tested steroids may bind elsewhere in the ρ1 receptor.

The classification of three distinct sites for inhibitory steroids in the ρ1 receptor is also in agreement with previous mutagenesis and fluorometrical data. The P294S mutation (2′ residue in the second membrane-spanning domain) selectively eliminates inhibition by 3α5βP, whereas the T298F mutation (6' in the second membrane-spanning domain) eliminates inhibition by β-estradiol (Li et al., 2007). Furthermore, the steroids 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-estradiol differently modify fluorescence changes caused by GABA in the extracellular domain of the receptor (Eaton et al., 2014). Here, we used an activation model–based approach to analyze ρ1 receptor modulation by inhibitory steroids. In previous work, the model has been most notably employed in studies of the actions of agonists and agonist combinations on heteromeric α1βγ2 GABAA receptors.

The electrophysiological data indicate that a common site mediates the actions of the inhibitory steroid 3α5βP and the potentiating steroid 5αTHDOC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of different steroids or analogs interacting with a common site eliciting opposite modulation of the GABAA receptor. Divergent modes of action have been reported previously for agonists and inverse agonists at the benzodiazepine site in the heteromeric αβγ GABAA receptor (Sigel and Ernst, 2018). In the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, the competitive antagonists bicuculline and gabazine inhibit activation by allosteric agonists and cause distinct conformational changes in a fluorescence assay (Ueno et al., 1997; Muroi et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2011). Finally, the different conformational changes elicited near the transmitter binding site by GABA and competitive antagonists may be considered a special case of this phenomenon. In the ρ1 receptor, the competitive antagonist 3-aminopropyl(methyl)phosphinic acid elicits conformational changes in the extracellular domain of the receptor that differ from those observed in the presence of GABA (Chang and Weiss, 2002).

Although energetic additivity arising from steroid interactions with distinct binding sites strongly enhances the net inhibitory effect when 3α5βP, 3α5βPS, and β-estradiol are coapplied, the low affinity of the steroids to the ρ1 receptor suggests little functional modulation under physiologic conditions. Using eq. 2, we estimate that the combination of 0.1 μM 3α5βP, 1 μM 3α5βPS, and 0.01 μM β-estradiol [approximate physiologic concentrations; (Bixo et al., 1995; Cheney et al., 1995; Weill-Engerer et al., 2002)] reduces the response to physiologic, ambient GABA (∼300 nM) from a Popen of 0.08 to 0.07. In a reverse calculation, to estimate the concentrations of the individual steroids needed to elicit a more “meaningful” reduction in Popen, we find that a 5-fold increase in 3α5βP (to 0.5 μM) and 3α5βPS (to 5 μM) is sufficient to reduce the open probability from 0.08 to 0.045. A more drastic increase in the concentration of β-estradiol is needed for further reduction in Popen (coapplication of 1 or 5 μM β-estradiol with 0.5 µM 3α5βP + 5 µM 3α5βPS reduces the Popen to 0.041 or 0.030, respectively). Incidentally, this suggests that targeting of the β-estradiol binding site is the most efficient way to pharmacologically modulate function of the ρ1 receptor that is exposed to physiologic concentrations of 3α5βP and 3α5βPS.

In summary, we have shown that the ρ1 GABAA receptor contains three classes of functionally defined nonoverlapping binding sites for neurosteroids: one each for sulfated steroids and β-estradiol and a shared site for 3α5βP and 5αTHDOC. Although interaction with distinct sites strongly enhances the net effect of combined drugs, the relatively low affinities and weak efficacies of the tested steroids suggest minimal modulation of the human ρ1 receptor by neurosteroids under physiologic conditions. This work has extended the applicability of the concerted transition model in two ways: by demonstrating that it can be used to analyze modulation by inhibitory allosteric agents as well as potentiate and by applying it to an additional member of the pentameric transmitter-gated ion-channel family.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Daniel J. Shin for help with electrophysiology.

Abbreviations

- c

ratio of the equilibrium dissociation constant of the open receptor to that of the closed receptor

- β-estradiol

(8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-methyl-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol

- GLIC

Gloeobacter violaceus ligand-gated ion channel

- 3α5βP

1-[(3R,5R,8R,9S,10S,13S,14S,17S)-3-hydroxy-10,13-dimethyl-2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-17-yl]ethanone (pregnanolone)

- PDB ID

Protein Data Bank Identification

- Popen

open probability of the receptor

- Popen, const

open probability of the constitutively active receptor

- 3α5βPS

[(3R,5R,8R,9S,10S,13S,14S,17S)-17-acetyl-10,13-dimethyl-2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-yl]ethanone hydrogen sulfate (pregnanolone sulfate)

- 5αTHDOC

(3α,5α)-3,21-dihydroxypregnan-20-one (allotetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone)

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Germann, Evers, Steinbach, Akk.

Conducted experiments: Germann, Burbridge, Pierce.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Reichert.

Performed data analysis: Germann, Burbridge, Pierce, Akk.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Germann, Reichert, Evers, Steinbach, Akk.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R01 GM108580] and [Grant R01 GM108799] and funds from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research.

Primary laboratory of origin (for G.K.): Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Akk G, Li P, Bracamontes J, Reichert DE, Covey DF, Steinbach JH. (2008) Mutations of the GABA-A receptor α1 subunit M1 domain reveal unexpected complexity for modulation by neuroactive steroids. Mol Pharmacol 74:614–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Li P, Bracamontes J, Wang M, Steinbach JH. (2011) Pharmacology of structural changes at the GABA(A) receptor transmitter binding site. Br J Pharmacol 162:840–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Shin DJ, Germann AL, Steinbach JH. (2018) GABA type A receptor activation in the allosteric coagonist model framework: relationship between EC50 and basal activity. Mol Pharmacol 93:90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alakuijala A, Alakuijala J, Pasternack M. (2006) Evidence for a functional role of GABA receptors in the rat mature hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 23:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alakuijala A, Palgi M, Wegelius K, Schmidt M, Enz R, Paulin L, Saarma M, Pasternack M. (2005) GABA receptor ρ subunit expression in the developing rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 154:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Weiss DS. (1994) Homomeric ρ 1 GABA channels: activation properties and domains. Receptors Channels 2:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Weiss DS. (1996) Insights into the activation mechanism of ρ1 GABA receptors obtained by coexpression of wild type and activation-impaired subunits. Proc Biol Sci 263:273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Pau D, Cabras G, Peters JA, Lambert JJ. (1999) A single amino acid confers barbiturate sensitivity upon the GABA ρ 1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol 127:601–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixo M, Bäckström T, Winblad B, Andersson A. (1995) Estradiol and testosterone in specific regions of the human female brain in different endocrine states. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 55:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Benavidez JM, Black M, Leiter CR, Osterndorff-Kahanek E, Johnson D, Borghese CM, Hanrahan JR, Johnston GA, Chebib M, et al. (2014) GABAA receptors containing ρ1 subunits contribute to in vivo effects of ethanol in mice. PLoS One 9:e85525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR, Huyvaert KP. (2011) AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Covey DF, Weiss DS. (2000) Correlation of the apparent affinities and efficacies of γ-aminobutyric acid(C) receptor agonists. Mol Pharmacol 58:1375–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Weiss DS. (1998) Substitutions of the highly conserved M2 leucine create spontaneously opening ρ1 γ-aminobutyric acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol 53:511–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Weiss DS. (2002) Site-specific fluorescence reveals distinct structural changes with GABA receptor activation and antagonism. Nat Neurosci 5:1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebib M, Hinton T, Schmid KL, Brinkworth D, Qian H, Matos S, Kim HL, Abdel-Halim H, Kumar RJ, Johnston GA, et al. (2009) Novel, potent, and selective GABAC antagonists inhibit myopia development and facilitate learning and memory. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328:448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Wells MM, Arjunan P, Tillman TS, Cohen AE, Xu Y, Tang P. (2018) Structural basis of neurosteroid anesthetic action on GABA A receptors. Nat Commun 9:3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZW, Bracamontes JR, Budelier MM, Germann AL, Shin DJ, Kathiresan K, Qian MX, Manion B, Cheng WWL, Reichert DE, et al. (2019) Multiple functional neurosteroid binding sites on GABAA receptors. PLoS Biol 17:e3000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZW, Manion B, Townsend RR, Reichert DE, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Sieghart W, Fuchs K, Evers AS. (2012) Neurosteroid analog photolabeling of a site in the third transmembrane domain of the β3 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor. Mol Pharmacol 82:408–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney DL, Uzunov D, Costa E, Guidotti A. (1995) Gas chromatographic-mass fragmentographic quantitation of 3 α-hydroxy-5 α-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone) and its precursors in blood and brain of adrenalectomized and castrated rats. J Neurosci 15:4641–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton MM, Germann AL, Arora R, Cao LQ, Gao X, Shin DJ, Wu A, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Steinbach JH, et al. (2016) Multiple non-equivalent interfaces mediate direct activation of GABAA receptors by propofol. Curr Neuropharmacol 14:772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton MM, Lim YB, Covey DF, Akk G. (2014) Modulation of the human ρ1 GABAA receptor by inhibitory steroids. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231:3467–3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert FJ. (2014) Analysis of allosteric interactions at ligand-gated ion channels, Affinity and Efficacy pp 179–249, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Forman SA. (2012) Monod-Wyman-Changeux allosteric mechanisms of action and the pharmacology of etomidate. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 25:411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutman JD, Calvo DJ. (2004) Studies on the mechanisms of action of picrotoxin, quercetin and pregnanolone at the GABA ρ 1 receptor. Br J Pharmacol 141:717–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. (2006) Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature 444:486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M, Bali M, Akabas MH. (2008) Modular design of Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels: functional 5-HT3 and GABA ρ1 receptors lacking the large cytoplasmic M3M4 loop. J Gen Physiol 131:137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Korol SV, Jin Z, Barg S, Birnir B. (2013) In intact islets interstitial GABA activates GABA(A) receptors that generate tonic currents in α-cells. PLoS One 8:e67228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty D, Thomas P, Field M, Andersen OJ, Gold MG, Biggin PC, Gielen M, Smart TG. (2017) Crystal structures of a GABA A-receptor chimera reveal new endogenous neurosteroid-binding sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24:977–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Bandyopadhyaya AK, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Akk G. (2009) Hydrogen bonding between the 17β-substituent of a neurosteroid and the GABA(A) receptor is not obligatory for channel potentiation. Br J Pharmacol 158:1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Covey DF, Alakoskela JM, Kinnunen PK, Steinbach JH. (2006) Enantiomers of neuroactive steroids support a specific interaction with the GABA-C receptor as the mechanism of steroid action. Mol Pharmacol 69:1779–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jin X, Covey DF, Steinbach JH. (2007) Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant ρ1 GABAC receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323:236–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz PD, Eggers ED, Sagdullaev BT, McCall MA. (2004) GABAC receptor-mediated inhibition in the retina. Vision Res 44:3289–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox FN, Valeyev AY, Poth K, Holohean AM, Wood PM, Davidoff RA, Hackman JC, Luetje CW. (2004) GABAA receptor subunit mRNA expression in cultured embryonic and adult human dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 149:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. (2006) Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF Chimera. BMC Bioinformatics 7:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Harris RA. (1996) Inhibition of ρ1 receptor GABAergic currents by alcohols and volatile anesthetics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PS, Aricescu AR. (2014) Crystal structure of a human GABAA receptor. Nature 512:270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PS, Scott S, Masiulis S, De Colibus L, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Aricescu AR. (2017) Structural basis for GABA A receptor potentiation by neurosteroids. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24:986–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KD, Amin J. (2004) Insight into the mechanism of action of neuroactive steroids. Mol Pharmacol 66:56–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KD, Moorefield CN, Amin J. (1999) Differential modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type C receptor by neuroactive steroids. Mol Pharmacol 56:752–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroi Y, Czajkowski C, Jackson MB. (2006) Local and global ligand-induced changes in the structure of the GABA(A) receptor. Biochemistry 45:7013–7022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naffaa MM, Hung S, Chebib M, Johnston GAR, Hanrahan JR. (2017) GABA-ρ receptors: distinctive functions and molecular pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol 174:1881–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama Y, Hattori N, Otani H, Inagaki C. (2006) γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-C receptor stimulation increases prolactin (PRL) secretion in cultured rat anterior pituitary cells. Biochem Pharmacol 71:1705–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzo A, Armellin M, Franzot J, Chiaruttini C, Nistri A, Tongiorgi E. (2002) Expression and dendritic mRNA localization of GABAC receptor ρ1 and ρ2 subunits in developing rat brain and spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 15:1747–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234:779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MY, Sali A. (2006) Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci 15:2507–2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada S, Cutting G, Uhl GR. (1992) γ-Aminobutyric acid A or C receptor? γ-aminobutyric acid ρ 1 receptor RNA induces bicuculline-, barbiturate-, and benzodiazepine-insensitive γ-aminobutyric acid responses in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Pharmacol 41:683–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DJ, Germann AL, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Akk G. (2019) Analysis of GABAA receptor activation by combinations of agonists acting at the same or distinct binding sites. Mol Pharmacol 95:70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel E, Ernst M. (2018) The benzodiazepine binding sites of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 39:659–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell HD, Gonzales EB. (2015) Amiloride and GMQ allosteric modulation of the GABA-A ρ1 receptor: influences of the intersubunit site. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 353:551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach JH, Akk G. (2019) Applying the Monod-Wyman-Changeux allosteric activation model to pseudo-steady-state responses from GABAA receptors. Mol Pharmacol 95:106–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31:455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Bracamontes J, Zorumski C, Weiss DS, Steinbach JH. (1997) Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci 17:625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers EJ, Farrell S. (2004) AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon Bull Rev 11:192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegelius K, Pasternack M, Hiltunen JO, Rivera C, Kaila K, Saarma M, Reeben M. (1998) Distribution of GABA receptor ρ subunit transcripts in the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci 10:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weill-Engerer S, David JP, Sazdovitch V, Liere P, Eychenne B, Pianos A, Schumacher M, Delacourte A, Baulieu EE, Akwa Y. (2002) Neurosteroid quantification in human brain regions: comparison between Alzheimer’s and nondemented patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:5138–5143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuei X, Flury-Wetherill L, Dick D, Goate A, Tischfield J, Nurnberger J, Jr., Schuckit M, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Hesselbrock V, et al. (2010) GABRR1 and GABRR2, encoding the GABA-A receptor subunits ρ1 and ρ2, are associated with alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 153B:418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]