Abstract

Increasing evidence shows that Curcumin (Cur) has a protective effect against cardiovascular diseases. However, the role of Cur in the electrophysiology of cardiomyocytes is currently not entirely understood. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the effects of Cur on the action potential and transmembrane ion currents in rabbit ventricular myocytes to explore its antiarrhythmic property. The whole-cell patch clamp was used to record the action potential and ion currents, while the multichannel acquisition and analysis system was used to synchronously record the electrocardiogram and monophasic action potential. The results showed that 30 μmol/L Cur shortened the 50 and 90% repolarization of action potential by 17 and 7%, respectively. In addition, Cur concentration dependently inhibited the Late-sodium current (INa.L), Transient-sodium current (INa.T), L-type calcium current (ICa.L), and Rapidly delayed rectifying potassium current (IKr), with IC50 values of 7.53, 398.88, 16.66, and 9.96 μmol/L, respectively. Importantly, the inhibitory effect of Cur on INa.L was 52.97-fold higher than that of INa.T. Moreover, Cur decreased ATX II-prolonged APD, suppressed the ATX II-induced early afterdepolarization (EAD) and Ca2+-induced delayed afterdepolarization (DAD) in ventricular myocytes, and reduced the occurrence and average duration of ventricular tachycardias and ventricular fibrillations induced by ischemia–reperfusion injury. In conclusion, Cur inhibited INa.L, INa.T, ICa.L, and IKr; shortened APD; significantly suppressed EAD and DAD-like arrhythmogenic activities at the cellular level; and exhibited antiarrhythmic effect at the organ level. It is first revealed that Cur is a multi-ion channel blocker that preferentially blocks INa.L and may have potential antiarrhythmic property.

Keywords: curcumin, ionic currents, action potential, ventricular myocytes, arrhythmias, ischemia–reperfusion

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading global cause of mortality, and approximately half of this mortality contributes to sudden cardiac deaths (SCDs) (Go et al., 2014), which generally occur after malignant arrhythmia. Most traditional antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) are selective ion channel blockers, a large part of which are limited in clinical application due to their potential proarrhythmic effects and numerous side effects (Zdanowicz and Lynch, 2011). However, the commonly used AAD (amiodarone) is a potent hERG channel inhibitor with a lower risk of proarrhythmic effect because of a counteraction to K+ current inhibition by either Na+ or Ca2+ channel blockade (Kodama et al., 1997; Martin et al., 2004). At present, it is generally believed that an ideal AAD should have multi-ion channel effects, and one of which is the best target (Budillon et al., 2005; Nattel and Carlsson, 2006; Barman, 2015; Polak et al., 2015). Modern cardiology is still waiting for the introduction of safe and effective AADs. Over the years, cumulative randomized controlled trials of traditional natural products have demonstrated its efficacy and safety in patients with CVDs and gradually popularized worldwide (Brenyo and Aktas, 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Hua et al., 2019).

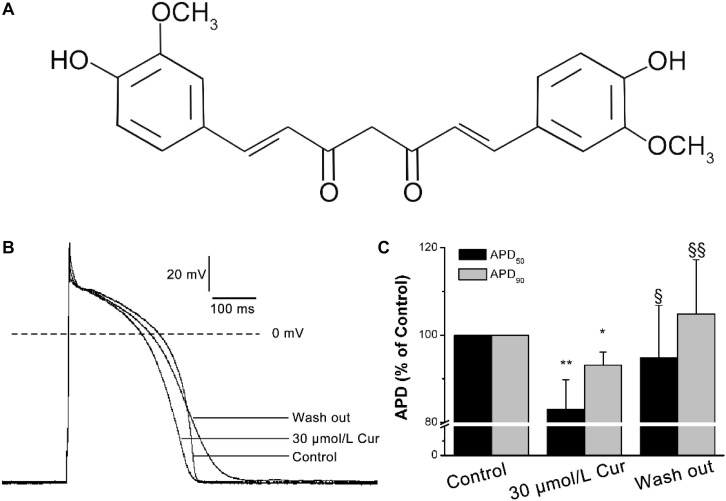

Curcumin (Cur: C21H20O6, MW:368.38, Figure 1A) is a natural yellow polyphenolic substance, the main active alkaloid extracted from the rhizome of turmeric, a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial plant belonging to the family Zingiberaceae, which has been used as an antiseptic and antipyretic folk medicine for centuries (Kumar et al., 2017). Previous researches have shown that Cur has extensive pharmacological activities (Aggarwal et al., 2007; Yallapu et al., 2015; Salehi et al., 2019; Salehi et al., 2020a, b) and has been put into clinical practice with a dose range of 180–3000 mg/day (Panahi et al., 2014). Increasing evidence showed that Cur has a protective effect against CVDs. For instance, Cur can prevent the development of heart failure by inhibiting p300 histone acetyltransferase activity (Morimoto et al., 2008), antagonized sodium fluoride intoxication in rat heart (Nabavi et al., 2011), prevented isoprenaline (ISO)-induced cardiac hypertrophy (Izem-Meziane et al., 2012), and can have a protective effect against the myocardial infarction injury (Nirmala and Puvanakrishnan, 1996). In addition, Cur was reported to prevent the QTc prolongation in ISO-induced myocardial infarction (Boarescu et al., 2019). However, Hu et al. found that Cur blocked hERG channel but had no significant effect on QT interval of rabbits (Hu et al., 2012). At present, few researches have been done on the effects of Cur on cardiac electrophysiology. Therefore, we carry out this study to better understand the electrophysiological properties of Cur and explore its antiarrhythmic property.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of Curcumin (Cur) on action potentials (APs) in ventricular myocytes. (A) Structural formula of Cur. (B) Example records of APs from the control group, Cur group, and wash out group in the same ventricular myocyte. (C) The comparisons of the average APD50 and APD90 percentage values of the control group, Cur group, and wash out group (n = 12, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control; § P < 0.05, §§ P < 0.01 vs. 30 μmol/L Cur).

Materials and Methods

Ventricular Myocytes Preparation

All animal experiments in this investigation were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use of Wuhan University of Science and Technology. Healthy adult New Zealand white rabbits of either sex, weighing 1.8–2.2 kg, were anesthetized with xylazine (Shanghai Shifeng Biological Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, 7.5 mg/kg i.m.) and ketamine (Fujian Gutian Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Fujian, China, 30 mg/kg i.v.); after heparinization, thoracotomy was performed to quickly remove the heart, which was then placed in oxygen-saturated Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). The cardiac aorta was retrogradely cannulated and hanged on the Langendorff-perfusion device, followed by perfusing with Ca2+-free Tyrode solution for 5 min, and then perfused with Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, MO, United States, type I, 1 mg/ml) and BSA (Roche Co., Basel, Switzerland, 1 mg/ml) for 40 min. Before isolating the left ventricle, the heart was perfused with KB solution containing the following (in mM): 85 KOH, 30 KCl, 15 KH2PO4, 6 MgSO4, 20 taurine, 10 glucose, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 50 L-glutamic acid (titrated to pH 7.4 with KOH) with BSA (1 mg/ml) for 5 min to terminate the enzymatic hydrolysis. The isolated left ventricle was snipped into small chunks and placed in KB solution containing BSA (1 mg/ml), gently blown to disperse the cells, and finally filtered through a nylon mesh. Individual ventricular myocytes were stored at 4°C in the same solution for 1 h before electrophysiological testing. All perfusates were saturated with O2 and maintained at 37 ± 0.5C with a thermostatic bath.

Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Preparation

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording was performed on single ventricular myocyte using an EPC10 amplifier (HEKA Electronic, Lambrecht, Germany), filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz. Electrodes were fabricated from borosilicate glass using a two-stage microelectrode puller (PP-100, Narishige Group, Tokyo, Japan) and tip resistances of 1.5–2.5 MΩ when filled with pipette solution. The cell suspension was placed in a 1 ml chamber mounted on the stage of a microscope (TE2000; Nikon, Japan) for about 5 min and then perfused with external solution at a rate of 2 ml/min via an FR-50 solution flow control valve (Warner Instruments Inc., United States) after the cells were completely attached to the chamber wall. The single ventricular myocyte with stable adherence, clear striations, and high refractive index was selected for recording. The electrode filled with pipette solution was inserted into the external solution using 3-D micro-manipulation (MP285, Sutter, United States). The Giga-Ohm seal was formed by the negative pressure, and then the whole-cell clamp mode with a series resistance of 2–5 MΩ was obtained by rupturing the cell membrane. Slow capacitance was routinely optimized and series resistance was compensated by 60–80%. All external solutions were saturated with O2 and experiments were conducted at room temperature (22–25°C).

APs and Ionic Currents Recordings

Ionic currents were recorded in a whole-cell mode of voltage-clamp configuration and the APs were recorded in a current-clamp configuration after the Giga-Ohm seal is implemented in voltage-clamp mode. Voltage protocols, pipette solutions, and external solutions were designed to record different ionic currents.

The pipette solution of APs contained the following (in mM): 5 NaCl, 30 KCl, 110 K-aspartate, 5 Mg-ATP, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 creatine phosphate, and 0.5 CAMP (titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH). The external solution of APs contained the following (in mM): 145 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose (titrated to pH 7.3 with NaOH).

The pipette solution of INa.L contained the following (in mM): 120 CsCl, 1 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 5 Na2ATP, 10 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), 11 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.3 with CsOH). There was no difference between the pipette solution of INa.L, ICa.L, and INa.T. The external solution of INa.L contained the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5.4 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 0.3 BaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 1.8 CaCl2 (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). The composition of external solution used to record ICa.L and INa.L was the same. However, 10 μmol/L nifedipine were added to the external solution to block ICa.L when recording INa.L. The low-sodium external solution was designed to record INa.T, which contain the following (in mM): 30 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 105 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.05 CdCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose (titrated to pH 7.4 with CsOH).

The pipette solution of IKr contained the following (in mM): 140 KCl, 5 K2ATP, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, and 5 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH). The external solution contained the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 5.4 KCl, 0.33 NaH2PO4, and 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). In order to eliminate the interference of the other currents, 10 μmol/L nifedipine (ICa.L blocker), 0.2 mmol/LBaCl2 (IK1 blocker), 0.2 mmol/L 4-AP (Ito blocker), and 30 μmol/L 293B (IKs blocker) were added to the external solution when recording Ikr.

CsCl and KH2PO4 were purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH, United States), while EGTA and HEPES were purchased from Biosharp (Hefei, China). The other unspecified drugs were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States).

For the AP recordings, we need to switch whole-cell clamp mode to current-clamp mode. APs were elicited by continuously stimulating the cells with suprathreshold (1.2–1.5 times) depolarizing pulses (6 ms duration) at a frequency of 1 Hz delivered via the patch pipette.

For the ICa.L recordings, the holding potential (HP) was −40 mV. The single ICa.L was elicited by a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV for 300 ms from the HP. The current–voltage (I–V) relationships of ICa.L was obtained by the 300-ms depolarizing steps from −40 to +60 mV in 5 mV increments. The steady-state inactivation of ICa.L was elicited by the use of a two-pulse protocol: stepping from −50 to 0 mV in 5 mV increments for 2 s followed by a 300 ms depolarizing pulse to 0 mV at 2 s intervals. The time-dependent recovery of ICa.L was determined by two 300 ms depolarizing pulses to 0 mV from the HP, the former of which is a condition pulse and the latter is a test pulse with intervals from 0 to 3100 ms in 100 ms increments.

For the INa.T and INa.L recordings, the HP was −90 mV. The single INa.T was elicited by a depolarizing pulse to −30 mV from HP, and the single INa.L was elicited by a depolarizing pulse to −20 mV and measured at 200 ms. The I–V relationships of INa.L were obtained by applying 300 ms depolarizing steps from −80 to +60 mV in 10 mV increments. Interval between the depolarizing steps was 2 s.

For the IKr recordings, the HP was −40 mV. The I–V relationships of Cur on IKr was elicited by 3000 ms depolarizing steps from −40 to +50 mV in 10 mV increments, and each depolarizing step is followed by a repolarizing pulse to −40 mV for 5 s to evoke large, slowly decaying outward tail currents (IK–tail).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and Monophasic Action Potential (MAP) Recordings of Langendorff-Perfused Isolated Hearts

The antiarrhythmic property of Cur was determined by 30 μmol/L Cur on arrhythmias induced by ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. ECG was recorded by three platinum electrodes, which had been placed near the cardiac apex, right atrium, and aortic root, while MAP was recorded by an electrode placed on the surface of the ventricle. ECG and MAP were monitored simultaneously for 150 min with a multichannel acquisition and analysis system (BL-420F, Taimeng Technology Instruments, Chengdu, china). In the I/R group, within 30 min, the hearts were perfused with Tyrode solution to determine whether they should be considered in the subsequent research; a heartbeat with a disordered rate or rhythm is an exclusion criterion. The arrhythmias were induced by stopping the perfusion for 60 min and then reperfusion for 60 min. In the Cur-I/R group, the perfusate was completely replaced with Tyrode solution containing 30 μmol/L Cur (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) before ischemia to observe the antagonistic effect of Cur on arrhythmias induced by I/R. The Cur used in the whole study was dissolved in DMSO, and the concentration of DMSO in the perfusate did not exceed 1‰.

Data Analysis and Statistic

Fitmaster (v2x32, HEKA Electronic) and Origin8.0 (Originlab, Northampton, MA, United States) were used for measurement, statistical analysis, and graphic fitting. The concentration–response curves were fitted with a Hill function of Y = Bmax/[1 + (IC50/D)n], where Y represents percentage inhibition of currents, n is the Hill coefficient, Bmax is the maximum inhibitory percentage of currents, and D is the Cur concentration. The steady-state (in)activation curves were fitted with a Boltzmann function of Y = 1/[1 + exp (Vm – V1/2)/k], where Y represents relative currents (I/Imax) of steady-state inactivation and the relative conductance (G/Gmax) of steady-state activation, respectively. V1/2 is half (in)activation potential, and Vm and k are the depolarization potential and slope factor, respectively. The conductance (G) was calculated by G = I/(Vm − Vrev) with the data in the I–V curves, where Vrev is the reversal potential. The time-dependent recovery curve was fitted with an exponential function of Y = 1 − exp(−t/τ), where Y represents I/Imax and t is the time interval between two pulses. The time constant τ reflects the rate of recovery from inactivation. The current data were normalized (current divided by capacitance) and expressed as current density. Data were presented as means ± SD. Parametric tests included Student’s t-test and one-way repeated ANOVA, which were followed by the Bonferroni test for two groups and multiple comparisons, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of Cur on APs

The results showed that there was no significant effect of Cur on resting membrane potential (RMP), action potential amplitude (APA), or maximum depolarization velocity (Vmax) (Table 1). Yet, Cur shortened APD50 by 17% but only shortened APD90 by 7% (Figure 1C). After continuous washing to eliminate the effects of the drug, the APD50 and APD90 were prolonged (Figure 1B).

TABLE 1.

Effects of Cur on the parameters of APs in rabbit ventricular myocytes.

| Parameters | Control | 30 μmol/L Cur | Wash out |

| RMP (mV) | −773 | −754 | −745 |

| APA (mV) | 1237 | 1149 | 11410 |

| APD50 (ms) | 23915 | 19922** | 22621§ |

| APD90 (ms) | 2718 | 25211* | 28229§§ |

| Vmax (V/s) | 18612 | 16425 | 15918 |

RMP, Resting membrane potential; APA, action potential amplitude; APD50, 50% repolarization of AP; APD90, 90% repolarization of AP; Vmax, maximum depolarization velocity (n = 12, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. control; §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01 vs. 30 μmol/L Cur).

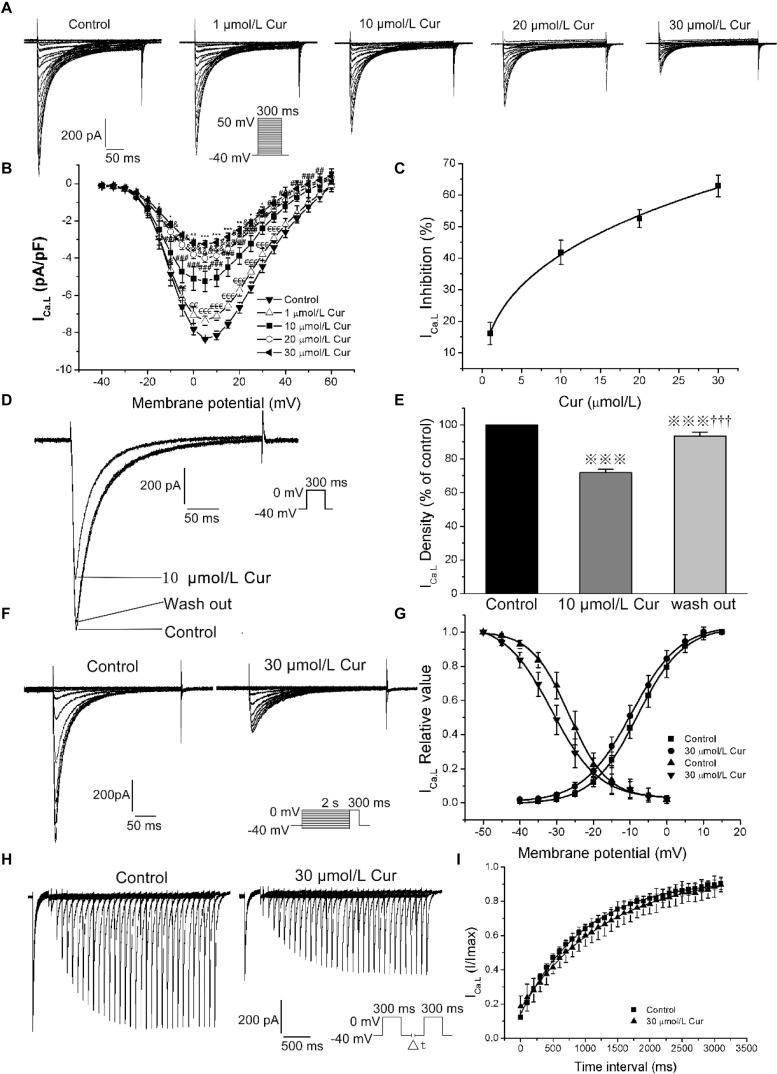

Effects of Cur on ICa.L

According to our previous literature, the recording of the ICa.L was started 10 min after the whole-cell mode was established and the entire experimental record was finished in 20 min to eliminate the deviation induced by ICa.L rundown (Jiang et al., 2017). By studying the effects of Cur on the I–V relationships, steady-state (in)activation, and time-dependent recovery of ICa.L in ventricular myocytes, the results showed that Cur inhibited ICa.L in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A) and the maximum current density of ICa.L was obtained at the test potential of 5 mV (Figure 2B). The concentration–response curve fitted with a Hill function with the IC50 value of ICa.L was calculated to be 16.66 μmol/L (Figure 2C). The ICa.L was inhibited by 10 μmol/L Cur and reversed by washing out, indicating that the inhibitory effect of Cur on ICa.L was reversible (Figures 2D,E), and 30 μmol/L Cur induced a left shift of steady-state inactivation with the inactivation V1/2 shifted from −27.17 ± 0.24 to −31.29 ± 0.13 (n = 20, P < 0.001 vs. control) and k was increased from 6.27 ± 0.17 to 7.12 ± 0.27 (n = 20, P < 0.001 vs. control, Figures 2F,G), with no significant effect on activation (Figure 2G). Cur also slowed the recovery from inactivation with τ value increasing from 988.83 ± 22.49 to 1379.22 ± 29.63 (n = 7, P < 0.01 vs. control) (Figures 2H,I).

FIGURE 2.

The effects of Cur on L-type calcium current (ICa.L) in ventricular myocytes. (A) Example records ICa.L in different membrane potentials for the control group and Cur (5, 10, 20, and 30 μmol/L) groups. (B) The current–voltage (I–V) relationship curves of Cur on ICa.L (n = 8, €P < 0.05, €€P < 0.01, €€€P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. 5 μmol/L; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 20 μmol/L). (C) The concentration–response relationship curve of Cur on ICa.L. (D) Example records of the single ICa.L from the same cell of three groups (control group, 10 μmol/L Cur group and wash out group), showing a reversible inhibitory effect of Cur on ICa.L. (E) The comparison of average ICa.L percentage values of the three groups (n = 6,  P < 0.001 vs. control; †††P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L Cur). (F) Example records of steady-state inactivation of ICa.L before and after administrating 30 μmol/L Cur. (G) Steady-state activation and inactivation curves of two groups. (H) Example records of time-dependent recovery of ICa.L before and after 30 μmol/L Cur administration. (I) Time-dependent recovery curves of the two groups.

P < 0.001 vs. control; †††P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L Cur). (F) Example records of steady-state inactivation of ICa.L before and after administrating 30 μmol/L Cur. (G) Steady-state activation and inactivation curves of two groups. (H) Example records of time-dependent recovery of ICa.L before and after 30 μmol/L Cur administration. (I) Time-dependent recovery curves of the two groups.

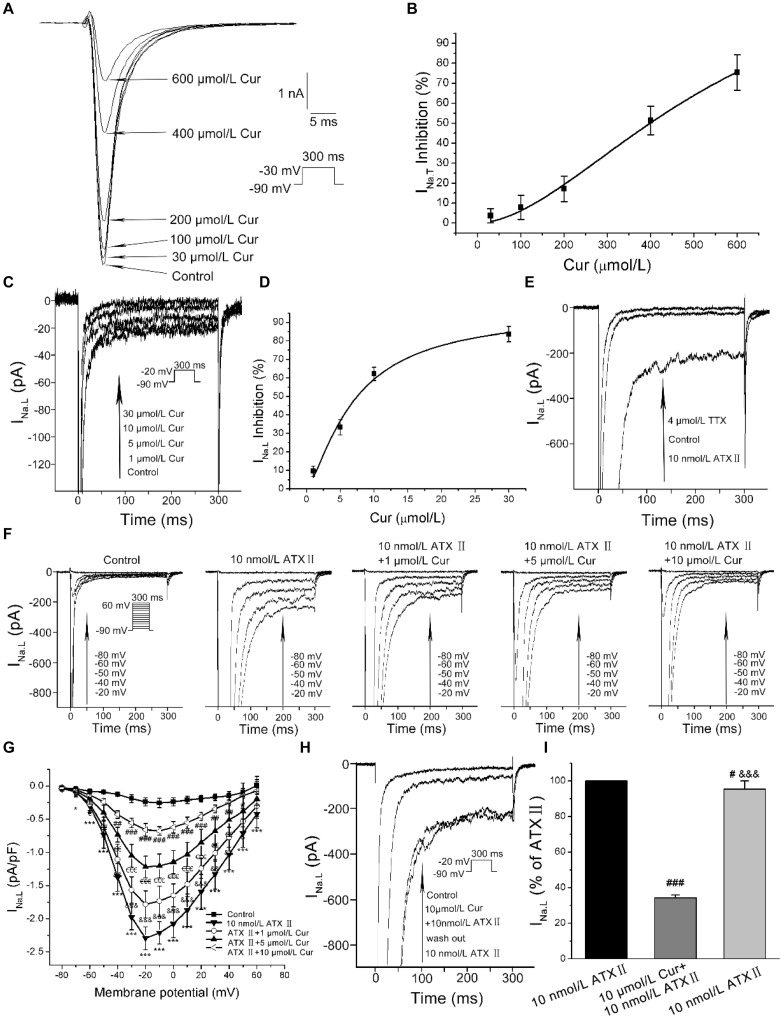

Effects of Cur on INa.L and INa.T

At the given concentration of 30 μmol/L, Cur only reduced the INa.T by 4%, and when the concentration increased to 100, 200, 400, and 600 μmol/L, the INa.T was gradually suppressed more significantly (Figure 3A). The concentration-dependent curve was fitted with a Hill function with the IC50 value calculated to be 398.88 μmol/L (Figure 3B). In addition, Cur reduced the basal endogenous INa.L in a concentration-dependent manner with reduced INa.L by 83% at the administration of 30 μmol/L Cur (Figure 3C), and the concentration–response relationship curves were fitted with a Hill function with the IC50 value calculated to be 7.53 μmol/L (Figure 3D). The IC50 ratio of Cur on INa.T and INa.L was 52.97, which means that the inhibitory effects of Cur on INa.L was 52.97-fold favorable than that of INa.T. In the next series of experiments, we used the INa.L opener–Sea anemone toxin II (ATX II, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) to induce an increase in the amplitude of INa.L to study the effects of Cur on the enhanced INa.L. The amplitude of recorded current was first augmented by 10 nmol/L ATX II, and then sodium channel blocker-TTX (Alomone Labs) at the concentration of 4 μmol/L was applied to the ATXII-increased currents to determine whether the current we recorded was INa.L. The results showed that the density of recorded currents was increased from −0.30 ± 0.04 to −1.93 ± 0.14 pA/pF (n = 12, P < 0.001 vs. ATX II) by 10 nmol/L ATX II, and then reduced to 0.11 ± 0.03 pA/pF (n = 12, P < 0.001 vs. control) by 4 μmol/L TTX (Figure 3E). It can be concluded that the currents we recorded were INa.L. Applying the different concentrations (1, 5, and 10 μmol/L) of Cur on ATXII-increased INa.L (Figure 3F), the I–V curves showed that Cur effectively inhibited the ATX II-increased INa.L (Figure 3G). In addition, ATX II-increased INa.L was significantly reduced with 10 μmol/L Cur and then increased again after wash out with 10 nmol/L ATX II (Figures 3H,I), which showed that the inhibitory effect of Cur on ATX II-increased INa.L was reversible.

FIGURE 3.

The effects of Cur on transient sodium currents (INa.T) and late sodium currents (INa.L) in ventricular myocytes. (A) Example records of the single INa.T of control group and Cur (30, 100, 200, 400, and 600 μmol/L) groups. (B) The concentration–response relationship curve of Cur on INa.T. (C) Example records of different concentrations of Cur on the basal endogenous INa.L. (D) The concentration–response relationship curve of Cur on the single basal endogenous INa.L. (E) Example records of INa.L of control, ATX II, and TTX groups. (F) Example records of ATX II increased-INa.L at membrane potentials of −80, −60, −50, −40, and −20 mV from the same cell for the control group, ATX II group, and Cur groups (1, 5, and 10 μmol/L). (G) The I–V relationships curves for the effects of Cur on ATX II-increased INa.L (n = 11, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. control; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001 vs. 10 nmol/L ATX II; €P < 0.05, €€P < 0.01, €€€P < 0.001 vs. 1 μmol/L Cur; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. 5 μmol/L Cur). (H) Example records of single INa.L showing a reversible inhibitory effect of Cur on ATX II-increased INa.L. (I) The comparison of average INa.L percentage values of the three groups (n = 8, #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. control; &&&P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L Cur).

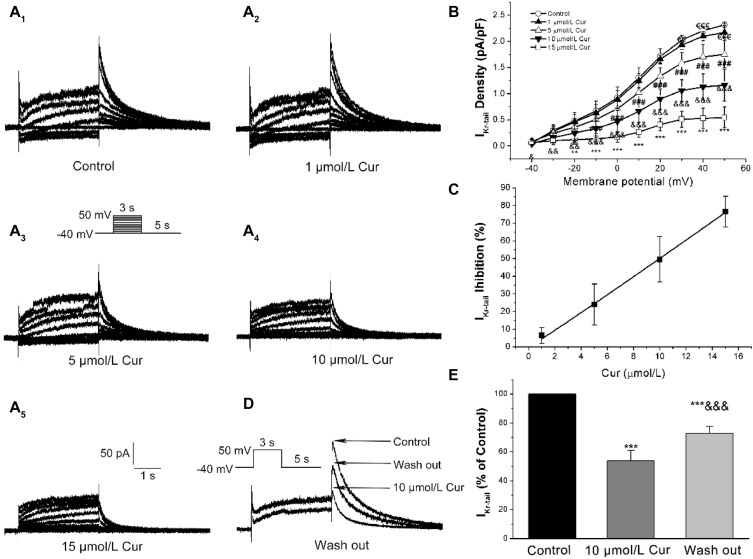

Effects of Cur on IKr

The I–V and concentration–response relationships of Cur on IKr was evaluated by measuring the tail currents (IK–tail) (Figure 4A). The I–V relationships curves showed that Cur inhibited IK–tail in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4B). The concentration–response relationship curves were fitted with a Hill function and the value of IC50 was calculated to be 9.96 μmol/L (Figure 4C). The IK–tail was inhibited by 10 μmol/L Cur and could be reversed by washing out (Figures 4D,E).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of Cur on rapidly delayed rectifying K+ currents (IKr) in ventricular myocytes. (A1–A5) Example records of Cur on IKr in different membrane potentials for the control group and Cur groups (1, 5, 10, and 15 μmol/L). (B) The I–V relationships curves for the effects of Cur on IKr–tail (n = 15, €€P < 0.01, €€€P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. 1 μmol/L Cur; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001 vs. 5 μmol/L Cur; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L Cur). (C) The concentration–response relationship curve of Cur on IKr–tail, fitted with a Hill function. (D) Example records of single IKr showing a reversible inhibitory effect of Cur on IKr–tail. (E) The comparison of average IKr–tail percentage values of three groups (n = 8, ***P < 0.001 vs. control, &&&P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L Cur).

Effects of Cur on the Early Afterdepolarization (EAD)-Like and Delayed Afterdepolarization (DAD)-Like Arrhythmogenic Activity in Ventricular Myocytes

INa.L opener-ATX II was used to induce a prolongation of APD and the occurrence of EADs to explore the potential antagonistic effects of Cur on EADs. The results showed that 10 nmol/L ATX II effectively prolonged APD (n = 11, Figure 5A), and all 11 ventricular myocytes occurred EADs (Figure 5B). For given Cur at a concentration of 20 μmol/L, the prolonged APD was significantly shortened and the occurrence of EADs was completely eliminated (11/11, Figure 5C). Moreover, EADs reappeared and APD prolonged again after continuous washing with external solution containing 10 nmol/L ATX II (11/11, Figures 5D–F).

FIGURE 5.

The antagonistic effects of Cur on the prolonged APD and early afterdepolarization (EAD) in ventricular myocytes. (A–D) Example records of APs with a train-of-three stimulation at a lower frequency of 0.25 Hz for the control group, ATX II group, Cur-treated group, and wash out group, respectively. (E) Example records of single APs at a frequency of 0.25 Hz on the different groups. (F) The comparison of average APD90 values of four groups (n = 11, ***P < 0.001 vs. control; ###P < 0.001 vs. 10 nmol/L ATX II; &&&P < 0.001 vs. 10 μmol/L ATX II with 20 μmol/L Cur).

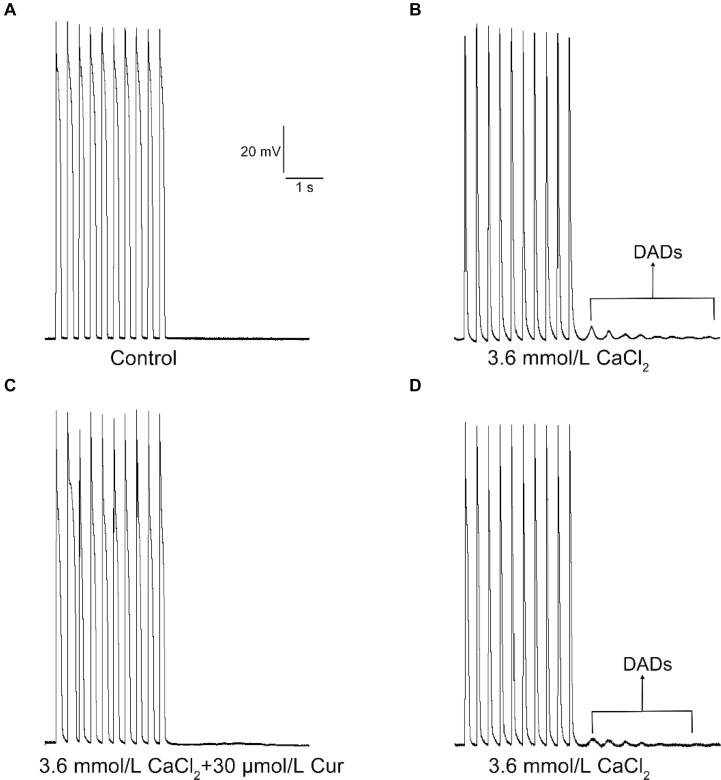

In the present study, the DADs were elicited by increasing the concentration of CaCl2 in the external solution to 3.6 mmol/L. DADs occurred in 9 of 9 ventricular myocytes (Figures 6A,B). At a concentration of 30 μmol/L, Cur completely suppressed the DADs in 9 of 9 ventricular myocytes (9/9, Figure 6C). The DADs reappeared after washing with the external solution containing 3.6 mmol/L CaCl2 (9/9, Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6.

The effects of Cur on delayed afterdepolarization (DAD) in ventricular myocytes. (A–D) Example records of APs with a train-of-10 stimulation at a higher frequency of 5 Hz, and the cycle length was 7 s. (A–D) Represent the control group, DAD group, Cur-treated group, and wash out group, respectively.

The Antiarrhythmic Effects of Cur on Langendorff-Perfused Rabbit Hearts Suffered From I/R Injury

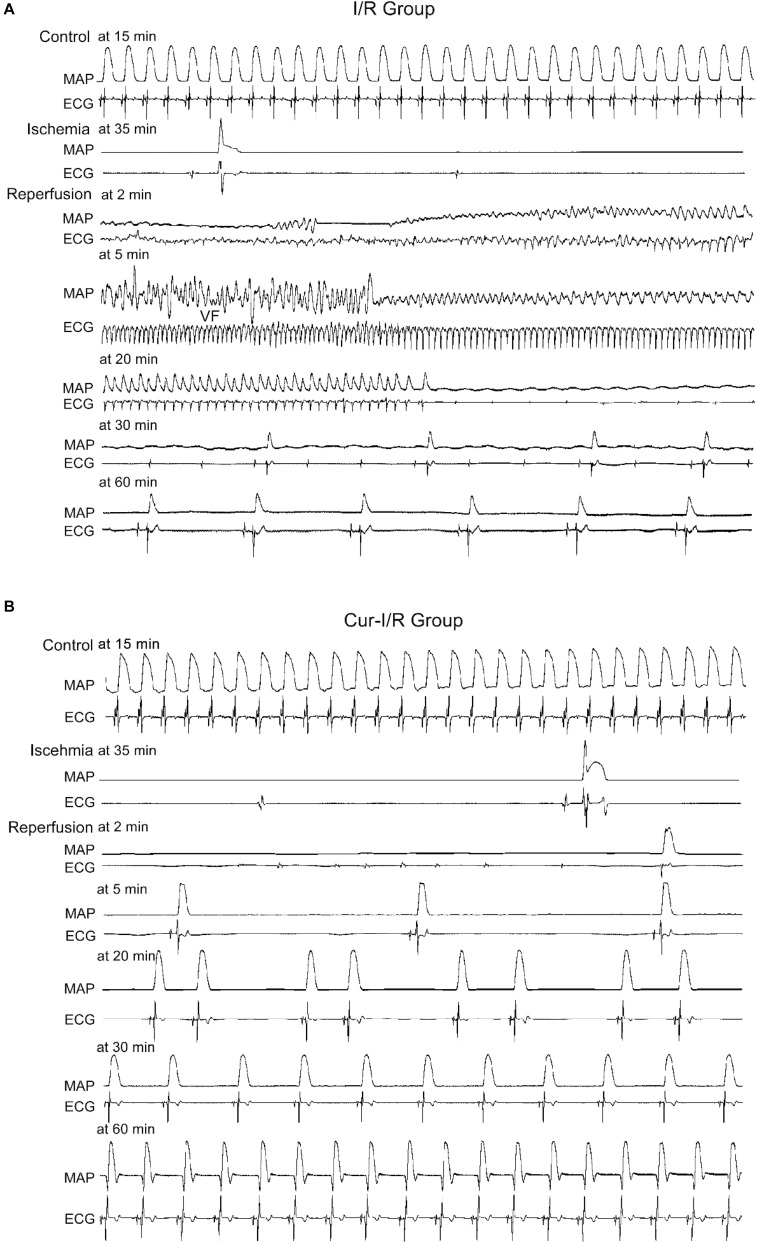

In the I/R group, the results showed that in 8 of 12 cases, both ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) occurred, while in the other 4 cases, only VF occurred (Figure 7A). In the Cur-I/R group (Figure 7B), there was a pretreatment of 30 μmol/L Cur before ischemia. VF and VT only occurred in one of seven I/R injury hearts; nevertheless, no VF or VT occurred in the other six cases and sinus rhythm was restored after reperfusion. The effect of Cur on I/R-induced arrhythmias was evaluated by comparing the average duration and incidence of VF and VT between two groups. The results showed that Cur significantly reduced the incidence and average duration of the VT and VF after reperfusion (Figures 8A,B). It can be seen that Cur revealed an anti-arrhythmic effect on isolated rabbit hearts subjected to I/R.

FIGURE 7.

The effects of Cur on isolated rabbit hearts that suffered from ischemia–reperfusion (I/R). (A,B) Example records of MAP and ECG of the Langendorff-perfused hearts in the I/R group (A) and Cur-I/R group (B).

FIGURE 8.

The histogram of I/R experiments results. (A) The comparison of average duration of ventricular fibrillation (VF) and ventricular tachycardia (VT) after reperfusion in the two groups (#P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. I/R group). (B) The comparison of the incidence of VF and VT in the two groups (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. I/R group).

Discussion

Cur is a kind of active alkali extracted from turmeric rhizomes and has long been used as a traditional medicine, especially the spice and coloring agent in food (Kumar et al., 2017). Over the past half century, extensive researches on Cur have shown that it is a highly pleiotropic molecule that has multiple pharmacological activities (Burashnikov and Antzelevitch, 2009; Gupta et al., 2013). In this study, we investigated the influence of Cur on the electrophysiology of rabbit ventricular myocytes and explored its antiarrhythmic property. The results of the present study suggested that Cur is a multi-ion channel blocker, which inhibited ICa.L, INa.L, INa.T, IKr and preferentially blocks INa.L, cumulatively resulting in the changes of AP waveform. Additionally, Cur exhibited an antagonism on EAD and DAD-like arrhythmias in ventricular myocytes, and also reduced the occurrence of VF and VT in Langendorff-perfused rabbit hearts subjected to I/R.

To our knowledge, the effect of Cur on the AP of ventricular myocytes is not clear. The generation of APs is the response to the organized activities of several transmembrane ionic currents in cardiomyocytes, and the AP waveform will be remodeled by disrupting the activity of these ionic currents. INa.T is the fundamental inward ion current that initiates the depolarization of the AP in ventricular myocytes (Rashid and Kuyucak, 2018). Our results found that 30 μmol/L Cur has no significant effect on APA or Vmax, which is consistent with the findings that 30 μmol/L Cur has no significant inhibitory effect on INa.T, suggesting that Cur did not affect the generation or conduction of AP in ventricular myocytes. It is well known that the APD related to the balance between inward Ca2+ and outward K+ channel. Moreover, latest research has confirmed that the basal endogenous INa.L is also a significant contributor to APD (Song and Belardinelli, 2017). In our study, Cur shortened APD50 more significantly than APD90 (APD50 and APD90 was shortened by 17 and 7%) which may be related to the blocking effects of Cur on INa.L, ICa.L, and IKr. The suppression of IKr would have caused the retardation and prolongation of APD, but the inhibitory effects of Cur on ICa.L and INa.L make a contrary effect on the prolongation of APD. The slight shortening of APD90 (only shortened by 7%) may not show up on the ECG, which was consistent with the previous study where Cur (1 mg/ml) had no significant influence on QT interval in vivo (Hu et al., 2012).

As we all know, the ICa.L-triggered excitation–contraction coupling is essential for cardio function and plays a crucial role in cardiac arrhythmias (Guia et al., 2001). The aberrant activation of ICa.L will cause intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) overload and lead to disequilibrium of [Ca2+]i homeostasis (Fabiato, 1983; Inui and Fleischer, 1988; Meissner et al., 1988; Cannell et al., 2013). In the present study, we found that Cur not only reduced the ICa.L but also played a role in the kinetics of L-type calcium channels, which accelerated steady-state inactivation and prolonged time-dependent recovery from inactivation. These various regulatory effects of Cur on ICa.L synergistically reduced the [Ca2+]i. The inhibition of ICa.L may prevent the [Ca2+]i overload and thus play an antiarrhythmic role (Damasceno et al., 2012).

In many pathological conditions (e.g., oxidative stress, ischemia, and heart failure), the augmentation of INa.L will prolong the APD and facilitate EADs (Tang et al., 2012; Toischer et al., 2013). Moreover, the increased INa.L may cause intracellular Na+ ([Na+]i) overload, which is followed by an increased influx of Ca2+ via enhanced reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (INCX), resulting in [Na+]i-dependent [Ca2+]i overload. This failure to maintain the homeostasis of [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i will induce arrhythmias. Thus, effective inhibition of INa.L can reduce [Na+]i-dependent [Ca2+]i overload and may suppress its induced arrhythmias (Cao et al., 2018; Li et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2011). At present, the traditional class I C Na+ channel inhibitors are potent inhibitors of INa.L used as AADs, but safety concerns have limited the use of these agents in clinical practice due to the significant inhibition of INa.T, such as Mexiletine, Quinidine, and Flecainide with an IC50 ratio on INa.T and INa.L of 1.96, 1.1, and 1, respectively, and clinically used AADs, such as Disopyramide and Procaine, which have a smaller IC50 ratio on INa.T and INa.L (Guo and Jenkinson, 2018). This non-negligible inhibition on INa.T may slow the conduction of AP especially in hearts with structural disease, leading to cardiac arrhythmia. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore a potent inhibitor of INa.L without inhibiting INa.T obviously. In our research, we found that the inhibitory effects of Cur on INa.L are far greater than INa.T with an IC50 ratio on INa.T and INa.L of 52.97. Even at a concentration of about 3.98-fold, the IC50 value of INa.L, Cur only reduced INa.T by 4%. Ranolazine appears to be the most clinically selective inhibitor of late INa.L with an IC50 ratio on INa.T and INa.L of 4.49 (Guo and Jenkinson, 2018). Similar to Cur, ranolazine not only inhibits INa.L and INa.T but also blocks IKr. It is a pity that there is no INa.L inhibitor that is more effective and selective than ranolazine, which remains the preferred INa.L inhibitor (Antzelevitch et al., 2011). In this sense, it may be safer for Cur to reduce INa.L instead of INa.T than the abovementioned class I C Na+ channel inhibitors.

From the above discussion, Cur was a multi-ion channel blocker that preferentially blocks INa.L, which had the potential to prevent [Ca2+]i overload by inhibiting ICa.L and INa.L. Previous clinical and experimental studies have indicated that the traditional natural products with multi-ion channel blocking effects not only inhibited the occurrence of arrhythmias to some extent but also have lower toxicity and side effect (Brenyo and Aktas, 2014; Chuang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Moreover, multi-ion channel blockers can decrease the risk of pro-arrhythmia, which is an obstacle of the traditional AADs (Nattel and Carlsson, 2006). Cur, a traditional natural product with a multi-ion channel blocker that preferentially blocks INa.L, may have lower toxicity and fewer side effects, with the addition of various clinical trials showing that Cur does not cause any adverse complications on liver and kidney function and it is safe even at high dose (Rahmani et al., 2018), which makes it worthy for further studies as a candidate of AAD.

Researches have shown that increased INa.L and ICa.L will not only prolong APD and cause EADs but also lead to DADs and triggered activities (Wagner et al., 2011). The EADs may contribute to the occurrence of ventricular premature contraction and torsade de pointes, thus leading to VF (Binah and Rosen, 1992). We found that Cur not only significantly shortened ATX II-prolonged APD but also suppressed the occurrence of EADs. In this study, the antagonistic effects of Cur on EADs may be related to its inhibitory effects on ATX II-increased INa.L, which had been investigated in the present study. In addition to EADs, the DADs were also implicated in arrhythmias and SCDs. DADs are the membrane potential oscillation that occurs after cardiomyocytes are completely repolarized. This membrane potential oscillation was caused by the increase of [Ca2+]i, leading to the enhanced INCX, which in turn generated the transient inward currents (Ter Keurs and Boyden, 2007). Therefore, it can be concluded that the DADs can be suppressed by reducing the [Ca2+]i. In this investigation, Cur displayed a significant antagonistic effect on the DAD-like arrhythmogenic activity in ventricular myocytes, which may be related to the inhibitory effects of Cur on ICa.L. Thus, it seems that Cur has the effect of inhibiting EAD-like and DAD-like arrhythmogenic activity at the cellular level.

Coronary disease is one of the leading causes of death and disability of CVDs, and the coronary recanalization usually cannot prevent cardiomyocyte death, but instead facilitate severe arrhythmias after reperfusion (Ruiz-Meana and Garcia-Dorado, 2009). Previous studies have demonstrated that I/R injury-induced arrhythmias related to [Ca2+]i overload, which is mainly caused by the significant augmentation of INa.L (Soliman et al., 2012). During the ischemia stage, the increased intracellular H2O2 and acidosis lead to the increase of inward Na+ currents, which causes intracellular Ca2+ aggregation via the reverse INCX. INa.L is intensified to rectify acidosis after reperfusion, which will lead to more serious destruction of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to severe arrhythmia (Ruiz-Meana and Garcia-Dorado, 2009). Thus, alleviating the [Ca2+]i overload will contribute to the suppression of I/R-induced arrhythmias. In the present study, Cur exhibited an inhibitory role on ICa.L and INa.L, which means that Cur can reduce [Ca2+]i. The findings also demonstrated that Cur can prevent the occurrence of arrhythmias after reperfusion, which is beneficial for the recovery of isolated heart suffering from I/R injury. The suppression effects of Cur on I/R-induced arrhythmias may be related to its inhibition on ICa.L and INa.L. The results of the study show that Cur has a certain antagonized effect on cardiac arrhythmia and has potential application prospects for AADs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Cur is a multi-ion channel blocker that inhibits ICa.L and IKr and preferentially blocks INa.L, shortens APD, suppresses EADs and DADs at the cellular level, and prevents I/R-induced arrhythmia at the organ level.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use of Wuhan University of Science and Technology.

Author Contributions

JM managed the experimental design and thesis supervision. LS managed the experiments, adjustment of experimental scheme, data analysis, creating the figure, and manuscript preparation. ZZ managed preliminary experiments, data collection and analysis, and involved in the manuscript preparation. LH managed the experiment in organ level and collected data based on the result. P-HZ managed the preparation of experimental materials and experimental method guidance in the whole study. P-PZ assisted in material preparation. ZC assisted in creating the figures and the manuscript refinement. ZL assisted in solution preparation and improving the experiment method. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- AADs

Antiarrhythmic drugs

- APA

Action potential amplitude

- APD50 and APD90

50% and 90% repolarization of action potential

- Cur

Curcumin

- CVDs

Cardiovascular diseases

- DAD

proarrhythmic Delayed afterdepolarization

- EAD

Early afterdepolarization

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- ICa.L

L-type calcium current

- INa.T

Transient-sodium current

- INa.L

Late-sodium current

- IKr

Rapidly delayed rectifying potassium current

- INCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- I/R

Ischemia–reperfusion

- MAP

Monophasic action potential

- RMP

Resting membrane potential

- Vmax

Maximum depolarization velocity

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

- [Ca2+]i

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- [Na+]i

Intracellular Na+ concentration.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81670302).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.00978/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aggarwal B. B., Sundaram C., Malani N., Ichikawa H. (2007). Curcumin: the Indian solid gold. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 595 1–75. 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C., Burashnikov A., Sicouri S., Belardinelli L. (2011). Electrophysiologic basis for the antiarrhythmic actions of ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 8 1281–1290. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman M. (2015). Proarrhythmic effects of antiarrhythmic drugs: case study of flecainide induced ventricular arrhythmias during treatment of atrial fibrillation. J. Atr. Fibrill. 8:1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binah O., Rosen M. R. (1992). Mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation 85(Suppl. 1), I25–I31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarescu P. M., Boarescu I., Bocsan I. C., Pop R. M., Gheban D., Bulboaca A. E., et al. (2019). Curcumin nanoparticles protect against isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction by alleviating myocardial tissue oxidative stress, electrocardiogram, and biological changes. Molecules 24:2802. 10.3390/molecules24152802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenyo A., Aktas M. K. (2014). Review of complementary and alternative medical treatment of arrhythmias. Am. J. Cardiol. 113 897–903. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budillon A., Bruzzese F., Di Gennaro E., Caraglia M. (2005). Multiple-target drugs: inhibitors of heat shock protein 90 and of histone deacetylase. Curr. Drug Targets 6 337–351. 10.2174/1389450053765905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burashnikov A., Antzelevitch C. (2009). New pharmacological strategies for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Ann. Noninvasive. Electrocardiol. 14 290–300. 10.1111/j.1542-474x.2009.00305.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell M. B., Kong C. H., Imtiaz M. S., Laver D. R. (2013). Control of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release by stochastic RyR gating within a 3D model of the cardiac dyad and importance of induction decay for CICR termination. Biophys. J. 104 2149–2159. 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z. Z., Tian Y. J., Hao J., Zhang P. H., Liu Z. P., Jiang W. Z., et al. (2018). Barbaloin inhibits ventricular arrhythmias in rabbits by modulating voltage-gated ion channels. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39 357–370. 10.1038/aps.2017.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S. F., Liao C. C., Yeh C. C., Lin J. G., Lane H. L., Tsai C. C., et al. (2016). Reduced risk of stroke in patients with cardiac arrhythmia receiving traditional Chinese medicine: a nationwide matched retrospective cohort study. Complement. Ther. Med 25 34–38. 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno D. D., Ferreira A. J., Doretto M. C., Almeida A. P. (2012). Anticonvulsant and antiarrhythmic effects of nifedipine in rats prone to audiogenic seizures. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 45 1060–1065. 10.1590/s0100-879x2012007500119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. (1983). Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. 245 C1–C14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go A. S., Mozaffarian D., Roger V. L., Benjamin E. J., Berry J. D., Blaha M. J., et al. (2014). Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guia A., Stern M. D., Lakatta E. G., Josephson I. R. (2001). Ion concentration-dependence of rat cardiac unitary L-type calcium channel conductance. Biophys. J. 80 2742–2750. 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)76242-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Jenkinson S. (2018). Simultaneous assessment of compound activity on cardiac Nav1.5 peak and late currents in an automated patch clamp platform. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 99:106575. 10.1016/j.vascn.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. C., Patchva S., Aggarwal B. B. (2013). Therapeutic roles of curcumin: lessons learned from clinical trials. AAPS J. 15 195–218. 10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C. W., Sheng Y., Zhang Q., Liu H. B., Xie X., Ma W. C., et al. (2012). Curcumin inhibits hERG potassium channels in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 208 192–196. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z., Zhai F. T., Tian J., Gao C. F., Xu P., Zhang F., et al. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of oral Chinese patent medicines as adjuvant treatment for unstable angina pectoris on the national essential drugs list of China: a protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 9:e026136. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M., Fleischer S. (1988). Purification of Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) from heart and skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Methods Enzymol. 157 490–505. 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57098-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izem-Meziane M., Djerdjouri B., Rimbaud S., Caffin F., Fortin D., Garnier A., et al. (2012). Catecholamine-induced cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction and mPTP opening: protective effect of curcumin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302 H665–H674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Zeng M., Cao Z., Liu Z., Hao J., Zhang P., et al. (2017). Icariin, a novel blocker of sodium and calcium channels, eliminates early and delayed afterdepolarizations, as well as triggered activity, in rabbit cardiomyocytes. Front. Physiol. 8:342. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama I., Kamiya K., Toyama J. (1997). Cellular electropharmacology of amiodarone. Cardiovasc. Res. 35 13–29. 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00114-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Singh A. K., Kaushik M. S., Mishra S. K., Raj P., Singh P. K., et al. (2017). Interaction of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) with beneficial microbes: a review. 3 Biotech 7:357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Wang Y. P., Gao L., Zhang P. P., Zhou Q., Xu Q. F., et al. (2013). Resveratrol protects rabbit ventricular myocytes against oxidative stress-induced arrhythmogenic activity and Ca2+ overload. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34 1164–1173. 10.1038/aps.2013.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. L., McDermott J. S., Salmen H. J., Palmatier J., Cox B. F., Gintant G. A. (2004). The utility of hERG and repolarization assays in evaluating delayed cardiac repolarization: influence of multi-channel block. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 43 369–379. 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G., Rousseau E., Lai F. A., Liu Q. Y., Anderson K. A. (1988). Biochemical characterization of the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal and cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 82 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T., Sunagawa Y., Kawamura T., Takaya T., Wada H., Nagasawa A., et al. (2008). The dietary compound curcumin inhibits p300 histone acetyltransferase activity and prevents heart failure in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 118 868–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi S. F., Nabavi S. M., Ebrahimzadeh M. A., Eslami S., Jafari N., Moghaddam H. (2011). The protective effect of curcumin against sodium fluoride-induced oxidative stress in rat heart. Arch. Biol. Sci. 63 563–569. 10.2298/abs1103563n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S., Carlsson L. (2006). Innovative approaches to anti-arrhythmic drug therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5 1034–1049. 10.1038/nrd2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmala C., Puvanakrishnan R. (1996). Protective role of curcumin against isoproterenol induced myocardial infarction in rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 159 85–93. 10.1007/bf00420910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panahi Y., Saadat A., Beiraghdar F., Sahebkar A. (2014). Adjuvant therapy with bioavailability-boosted curcuminoids suppresses systemic inflammation and improves quality of life in patients with solid tumors: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 28 1461–1467. 10.1002/ptr.5149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak S., Pugsley M. K., Stockbridge N., Garnett C., Wisniowska B. (2015). Early drug discovery prediction of proarrhythmia potential and its covariates. AAPS J. 17 1025–1032. 10.1208/s12248-015-9773-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani A. H., Alsahli M. A., Aly S. M., Khan M. A., Aldebasi Y. H. (2018). Role of curcumin in disease prevention and treatment. Adv. Biomed. Res. 7:38 10.4103/abr.abr_147_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M. H., Kuyucak S. (2018). Computational study of the loss-of-function mutations in the Kv1.5 channel associated with atrial fibrillation. ACS Omega 3 8882–8890. 10.1021/acsomega.8b01094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Meana M., Garcia-Dorado D. (2009). Translational cardiovascular medicine (II). Pathophysiology of ischemia-reperfusion injury: new therapeutic options for acute myocardial infarction. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 62 199–209. 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)71538-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B., Calina D., Docea A. O., Koirala N., Aryal S., Lombardo D., et al. (2020a). Curcumin’s nanomedicine formulations for therapeutic application in neurological diseases. J. Clin. Med. 9:430. 10.3390/jcm9020430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B., Del Prado-Audelo M. L., Cortes H., Leyva-Gomez G., Stojanovic-Radic Z., Singh Y. D., et al. (2020b). Therapeutic applications of curcumin nanomedicine formulations in cardiovascular diseases. J. Clin. Med. 9:746. 10.3390/jcm9030746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B., Lopez-Jornet P., Pons-Fuster Lopez E., Calina D., Sharifi-Rad M., Ramirez-Alarcon K., et al. (2019). Plant-derived bioactives in oral mucosal lesions: a key emphasis to curcumin, lycopene, chamomile, aloe vera, green tea and coffee properties. Biomolecules 9:106. 10.3390/biom9030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman D., Wang L., Hamming K. S., Yang W., Fatehi M., Carter C. C., et al. (2012). Late sodium current inhibition alone with ranolazine is sufficient to reduce ischemia- and cardiac glycoside-induced calcium overload and contractile dysfunction mediated by reverse-mode sodium/calcium exchange. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 343 325–332. 10.1124/jpet.112.196949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Belardinelli L. (2017). Basal late sodium current is a significant contributor to the duration of action potential of guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Physiol. Rep. 5:e13295. 10.14814/phy2.13295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., Ma J., Zhang P., Wan W., Kong L., Wu L. (2012). Persistent sodium current and Na+/H+ exchange contributes to the augmentation of the reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange during hypoxia or acute ischemia in ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 463 513–522. 10.1007/s00424-011-1070-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Keurs H. E., Boyden P. A. (2007). Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol. Rev. 87 457–506. 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toischer K., Hartmann N., Wagner S., Fischer T. H., Herting J., Danner B. C., et al. (2013). Role of late sodium current as a potential arrhythmogenic mechanism in the progression of pressure-induced heart disease. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 61 111–122. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S., Ruff H. M., Weber S. L., Bellmann S., Sowa T., Schulte T., et al. (2011). Reactive oxygen species-activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIdelta is required for late I(Na) augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ. Res. 108 555–565. 10.1161/circresaha.110.221911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Russell A., Yan Y. (2014). Erratum to: traditional Chinese medicine and new concepts of predictive, preventive and personalised medicine in diagnosis and treatment of sub-optimal health. EPMA J. 5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Q., Jiang X. J., Zhang G. Y., Chen M., Tong C. F., Zhang D. (2016). Effects of ginseng-spikenard heart-nourishing capsule on inactivation of C-type Kv1.4 potassium channel. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 29 1513–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallapu M. M., Nagesh P. K., Jaggi M., Chauhan S. C. (2015). Therapeutic applications of curcumin nanoformulations. AAPS J. 17 1341–1356. 10.1208/s12248-015-9811-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. F., Li C. Z., Wang W., Chen Y. M., Zhang Y., Liu Y. M., et al. (2011). Electrophysiological mechanisms of sophocarpine as a potential antiarrhythmic agent. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32 311–320. 10.1038/aps.2010.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdanowicz M. M., Lynch L. M. (2011). Teaching the pharmacology of antiarrhythmic drugs. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 75:139. 10.5688/ajpe757139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.