Abstract

Evidence indicates that angiotensin II type 2 receptors (AT2R) exert cerebroprotective actions during stroke. A selective non-peptide AT2R agonist, Compound 21 (C21), has been shown to exert beneficial effects in models of cardiac and renal disease, as well as hemorrhagic stroke. Here, we hypothesize that C21 may exert beneficial effects against cerebral damage and neurological deficits produced by ischemic stroke. We determined the effects of central and peripheral administration of C21 on the cerebral damage and neurological deficits in rats elicited by endothelin-1 induced middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), a model of cerebral ischemia. Rats infused centrally (intracerebroventricular) with C21 before endothelin-1 induced MCAO exhibited significant reductions in cerebral infarct size and the neurological deficits produced by cerebral ischemia. Similar cerebroprotection was obtained in rats injected systemically (intraperitoneal) with C21 either before or after endothelin-1 induced MCAO. The protective effects of C21 were reversed by central administration of an AT2R inhibitor, PD123319. While C21 did not alter cerebral blood flow at the doses used here, peripheral post-stroke administration of this agent significantly attenuated the MCAO-induced increases in inducible nitric oxide synthase, chemokine (C-C) motif ligand 2 and C-C chemokine receptor type 2 mRNAs in the cerebral cortex, indicating that the cerebroprotective action is associated with an anti-inflammatory effect. These results strengthen the view that AT2R agonists may have potential therapeutic value in ischemic stroke, and provide the first evidence of cerebroprotection induced by systemic post stroke administration of a selective AT2R agonist.

Keywords: Compound 21, Angiotensin type 2 receptor, Stroke, Endothelin-1, Ischemia, Chemokine

1. Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) encompasses multiple pathways involved in the pathophysiology of cerebrovascular disease, and RAS pathways are promising targets for both acute and preventative therapies (Ferreira et al., 2010). Initially, experiments on the cerebroprotective potential of RAS pathways focused on inhibiting the angiotensin II (Ang II) type 1 receptor (AT1R) using AT1R antagonists (ARBs) (Lu et al., 2005). More recently, studies suggest that Ang II type 2 receptors (AT2R) exert a protective effect during ischemic stroke. Tissue levels of AT2R are increased in the peri-infarct region of the brain following ischemic injury (Li et al., 2005; Makino et al., 1996), and Ang II-induced activation of neuronal AT2R elicited differentiation and regeneration (Cote et al., 1999; Reinecke et al., 2003). Thus, it was hypothesized that the increased expression of AT2R within the peri-infarct region could, in the presence of ARBs to block AT1R, be activated by the raised endogenous levels of Ang II and serve a neuroprotective role (Li et al., 2005). Data from this and other studies support this idea by demonstrating that the beneficial action of ARBs after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO)-induced cerebral ischemia is prevented by specific AT2R blockers (Faure et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005). Further support for the cerebroprotective potential of AT2R agonism comes from data indicating that MCAO produces greater ischemic brain damage in AT2R knockout mice compared with wild-type controls, and that AT1R blockade was more effective at reducing ischemic damage and neurological deficits in wild type mice compared with mice lacking AT2R (Iwai et al., 2004). Finally, direct evidence for AT2R mediated cerebroprotection was obtained from studies which demonstrated that central treatment with the peptide AT2R agonist CGP42112 pre- or post stroke reduced cortical infarct volume and behavioral deficits following endothelin-1 (ET-1) induced MCAO, effects that were inhibited by the AT2R antagonist, PD123319 (McCarthy et al., 2009, 2012).

The development of a specific non-peptide AT2R agonist, Compound 21 (C21), has made the AT2R a potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases (Steckelings et al., 2011; Carey, 2013). C21 has already been shown to reduce vascular injury and myocardial fibrosis, and renal inflammation and survival, in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (Gelosa et al., 2009; Rehman et al., 2012), as well as renal inflammatory responses in a rat model of renovascular hypertension (Matavelli et al., 2011). Additionally, C21 treatment prevents renal inflammation in renovascular hypertension and in pre-hypertensive obese Zucker rats via induction of interleukin-10 (Dhande et al., 2013). In the current study we assessed the potential cerebroprotective actions of central or peripheral administration of C21 against ischemic stroke produced by ET-1 induced MCAO.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and ethical approval

Male Sprague Dawley rats (8 weeks old; 250–275 g), purchased from Charles River Farms (Wilmington, MA), were used in this study. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In addition, these studies were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Academy of Sciences (eighth ed., 2011). Rats had ad libitum access to water and standard rat chow and were housed in a well-ventilated, specific pathogen-free, temperature-controlled environment (24 ± 1 °C; 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle).

2.2. Anesthesia, analgesia and euthanasia

For surgical procedures, anesthesia was induced using 100% O2/4% isoflurane, and was maintained throughout the surgeries by the administration of 100% O2/2% isoflurane. During the surgeries/procedures, the level of anesthesia was monitored by checking the eye blink reflex and a reaction to paw pinch, and was adjusted if necessary. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, s.c., Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) was administered to rats immediately following the survival surgeries. Animals were euthanized by placing them under deep anesthesia with 100% O2/5% isoflurane, followed by decapitation.

2.3. Implantation of intracranial cannulae

After a 7 day acclimation period, rats were anesthetized as above placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame. They were implanted with a 21 gauge stainless steel guide cannula into the right cerebral hemisphere (1.6 mm anterior and 5.2 mm lateral to bregma), as detailed previously (Regenhardt et al., 2013). This cannula was utilized, seven days after implantation, for injection of either ET-1 (3 μl of 80 μM solution; 1 μl/min) to induce MCAO or control solution (0.9% saline) for the sham MCAO rats (Mecca et al., 2011). In certain experiments rats underwent a second surgery immediately following implantation of the guide cannula. This surgery involved implantation of a stainless steel cannula (kit 1; ALZET, Cupertino, CA, USA) into the left lateral cerebroventricle (1.3 mm posterior and 1.5 mm lateral to bregma, 4.5 mm below the surface of the cranium) as detailed previously (Mecca et al., 2011). This cannula was coupled via vinyl tubing to a 2 week osmotic pump (model 2002; ALZET, Cupertino, CA) (Mecca et al., 2011). In these animals, osmotic pumps were implanted subcutaneously between the scapulae and were used to infuse either C21, PD123319 or control solution [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)] via the intra-cerebroventricular (ICV) route starting at the time of cannula placement and lasting until the animals were euthanized. Body temperature and the level of anesthesia were monitored throughout these surgical procedures.

2.4. Measurement of cerebral blood flow

Laser Doppler flowmetry was used to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF) as detailed previously (Mecca et al., 2011). In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame as described above. CBF measurements were performed using a Standard Pencil Probe and Blood Flow Meter coupled to a Powerlab 4/30 with LabChart 7 (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The probe was secured to the skull surface with a plastic holder placed just posterior to the MCA guide cannula.

2.5. Experimental protocols

Experiment 1:

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether centrally applied C21 exerted protective effects during ischemic stroke. Rats were infused ICV with C21 (0.0075 μg/μl//h) or 1 μl of aCSF for 7 days, and then underwent ET-1 induced MCAO. After 3 more days of ICV C21 or aCSF infusion, rats underwent neurological testing, and were then euthanized to assess cerebral infarct volume. Since C21 has a half-life of ~4 h in rats (Wan et al., 2004), it was infused centrally before and after stroke in order to elicit a constant level of drug in the CNS during the insult. The dose of C21 infused ICV in this experiment was based on a previous study in which ICV infusion of a higher dose of C21 (0.5 μg/μl//h) elicited AT2R specific effects (Gao et al., 2011). Since the ICV dose of C21 used in our study is lower, we do not expect AT1R activity.

Experiment 2:

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether C21 applied systemically before and after the insult exerted protective effects against ischemic stroke. Rats were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with either C21 (0.03 mg/kg or 0.1 mg/kg) or control solution (0.9% sterile saline). Two hours later, rats underwent ET-1 induced MCAO. At 4, 24 and 48 h following MCAO, rats received further IP injections of C21 (0.03 mg/kg or 0.1 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline. At 3 days post-MCAO rats underwent neurological testing, and were then euthanized to assess cerebral infarct volume. The doses of C21 injected IP in this and subsequent experiments were based on doses of C21 (0.03–0.3 mg/kg) used in previously published studies that elicited effects blocked by the AT2R antagonist PD123319 (Bosnyak et al., 2010; Gelosa et al., 2009; Wan et al., 2004). In addition, pharmacokinetic data provided by Vicore Pharma (Göteborg, Sweden; suppliers of C21) indicate that intravenous injection of 0.03 mg/kg C21 (the primary dose used in our study) results in a peak plasma concentration of approximately 0.1 μM C21. The Ki of C21 for the AT1R is >10 μM (Bosnyak et al., 2011; Wan et al., 2004), meaning that when plasma peak concentrations of C21 are well below 1 μM there will not be a stimulation of AT1R. Based on this, and since it can be assumed that plasma concentrations of C21 obtained after IP injection will be lower than after intravenous injection, we expected that any effects produced by IP administered 0.03 mg/kg C21 would be AT2R-mediated.

Experiment 3:

The aim of this experiment was to determine if C21, applied systemically at a dose that elicited cerebroprotection, altered blood pressure. Rats were administered a single IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline, followed 30 min later by mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) measurement via an occlusion tail-cuff.

Experiment 4:

The aims of this experiment were twofold: to determine if C21, applied systemically at a dose that elicited cerebroprotection, altered (1) baseline CBF and (2) the decrease in CBF produced by ET-1 induced MCAO. (1) Rats were administered a single IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline, followed by analysis of CBF for 60 min; (2) administered a single IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline 2 h prior to ET-1 induced MCAO, as in Experiment 2. CBF was monitored starting 5 min before ET-1 induced MCAO and continued until 4 h post ET-1 injection.

Experiment 5:

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether C21 applied systemically only after the MCAO insult exerted protective effects against ischemic stroke. This protocol was similar to Experiment 2, with two exceptions: rats were not administered the pre-MCAO IP injection of C21 or 0.9% saline, and only one dose of C21 (0.03 mg/kg) was used.

Experiment 6:

The aim of this experiment was to determine whether the cerebroprotective action of C21 applied systemically after the insult was mediated by central AT2R. Rats were infused ICV with PD123319 (0.3 μg/μl/h) or aCSF for 7 days prior to and 3 days following ET-1 induced MCAO. C21 (0.03 mg/kg, IP) was administered at 4, 24 and 48 h post-MCAO. At 3 days post-MCAO rats underwent neurological testing, and were then euthanized to assess cerebral infarct volume. Since PD123319 has a very short half-life (~20 min) in rats (Levy et al., 1996), it was infused centrally before and after ET-1 induced MCAO and C21 application.

Experiment 7:

The aim of this experiment was to investigate whether the cerebroprotective action of systemically applied C21 was associated with changes in inflammatory gene expression in the brain. Rats underwent ET-1 induced MCAO or a sham MCAO, followed 4 and 12 h later with IP injections of either C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline. Twenty-four hours post MCAO or sham MCAO, one group of rats underwent neurological testing, followed by euthanization to assess cerebral infarct volume. Another group of rats, treated with C21 in identical fashion, were euthanized at 24 h post-stroke, brains removed and processed for analysis of gene expression in cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the MCAO. Initial studies demonstrated that analysis of gene expression in the cerebral cortex at48 h or later time points after stroke was unreliable. Further, in associated studies we have demonstrated that the cerebroprotective actions of Ang-(1–7) are associated with potent anti-inflammatory actions at 24 h post stroke (Mecca et al., 2011; Regenhardt et al., 2013). Hence our choice of 24 h for gene expression analyses in these studies. This necessitated an alteration in the post-stroke C21 treatment protocol (4 and 12 h instead of 4, 24 and 48 h).

2.6. Neurological testing

Neurological testing was performed 24 or 72 h post ET-1 induced MCAO, depending on the Experiment, using the Bederson (perfect score = 0) and Garcia (perfect score = 18) exams, which cumulatively evaluate spontaneous activity, symmetry in limb movement, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, response to vibrissae touch, resistance to lateral push and circling behavior (Bederson et al., 1986; Garcia et al., 1995). Investigators who were blinded to the treatment performed all neurological exams on rats.

2.7. Intracerebral infarct size

Cerebral infarct size was assessed by staining a single 2 mm coronal brain section from each rat with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; 0.05%) for 30 min at 37 °C as detailed previously (Mecca et al., 2011). This 2 mm coronal brain section was ~1 mm rostral and ~1 mm caudal to the optic chiasm. Tissue ipsilateral to the occlusion, which was not stained, was assumed to be infarcted. After fixation with 10% formalin, brain sections were scanned on a flatbed scanner (Canon) and analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH). Using this single 2 mm brain section, the stained (un-infarcted) cross-sectional area of the contralateral (left) hemisphere was used to calculate, in the same slice, the infarct size (unstained tissue) within the hemisphere ipsilateral to the ET-1 induced MCAO. To compensate for the effect of brain edema, the corrected infarct volume was calculated using an indirect method (Kagiyama et al., 2004; Lin et al., 1993). Cerebral infarct measurements were performed by individuals who were blinded as to the treatment groups.

Note that we chose to perform analyses of cerebral infarcts on single brain sections as the infarct size obtained from this analysis at 72 h following ET-1 induced MCAO (45.11 ± 7.2%; n = 5 rats) was not significantly different from that obtained when making assessments using five 2 mm coronal brain slices (1 rostral and 3 caudal to the above-described single slice) from the same rats (average 43.89 ± 4.8%; n = 5 rats). Similarly, there was no difference in the cerebral infarct sizes obtained from analysis of a single brain slice (22.29 ± 8.4%; n = 3 rats) or five 2 mm brain slices (20.45 ± 7.4%; n = 3 rats) from C21-treated rats (0.03 mg/kg IP; administered IP using the protocol described in Experiment 5, above).

2.8. mRNA analyses

Cluster of differentiation 11b (CD11b), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), myeloperoxidase (MPO), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), chemokine (C-C) motif ligand 2 (CCL2), C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) mRNA were analyzed via real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) in a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as detailed previously (Regenhardt et al., 2013). Oligonucleotide primers and Taqman probes specific for the above genes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA.

2.9. Chemicals

C21 was a generous gift from Vicore Pharma (Göteborg, Sweden). PD123319 was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). ET-1 was from American Peptide Company, Inc (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

2.10. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Of the 208 rats used for this study, 8 rats died shortly after or did not recover from the ET-1-induced MCAO. A further 6 rats were excluded from the study as they did not develop any discernable stroke following the ET-1 induced MCAO, as evidenced by perfect neurological scores and confirmed after euthanasia by assessment of cerebral infarct as described above.

2.11. Experimental groups, randomization and allocation concealment

Rats were assigned within each of the Experimental protocols as follows. Each rat within these protocols was assigned a number, and then assigned to a group using a computer program (Microsoft Excel). This allocation was concealed to the individuals who performed the ET-1 induced MCAO, drug treatments and behavioral testing.

2.12. Data analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated, as specified in the figure legends, with the use of the Kruskal–Wallis test, One-way ANOVA, Mann Whitney test or unpaired t-test, as well as with Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test, Bonferroni’s test, or Newman–Keuls Multiple Comparison Test for post-hoc analyses when appropriate. Power analyses were performed to calculate sample sizes. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. ICV pre-treatment with C21 reduces the neurological deficits and cerebral injury after ET-1 induced MCAO

ICV infusion of C21 (0.0075 μg/μl/h) into rats pre- and post ET-1 induced MCAO as described in Experiment 1 in the Methods produced a significant decrease in the cerebral infarct size (measured 72 h following ET-1 application) when compared with control (aCSF infused) rats (Fig. 1). Central pre-treatment with C21 also attenuated the neurological deficits attributable to ET-1 induced MCAO, as evidenced by significant improvements in the Bederson and Garcia exam scores when compared with the control rats (Fig. 1). Our previous experiments have shown that rats receiving a sham MCAO (0.9% saline instead of ET-1) have no discernable infarcts or neurological deficits (Mecca et al., 2011; Regenhardt et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Central pre-treatment with C21 is cerebroprotective. Rats were pre-treated with C21 (0.0075 μg/μl/h) or 1 μl of aCSF via ICV infusion for 7 days prior to ET-1 induced MCAO. (A) Bar graphs show % cerebral infarct size (white color) and (B) representative brain sections from each treatment condition. Panels (C) and (D) are data from Bederson and Garcia Neurological Exams, respectively. Data are means ± SEM from 21 (C21-treated) and 16 (aCSF-treated) rats. *p < 0.05 vs. saline control (unpaired t-test for panel A and Mann Whitney test for panels C and D).

3.2. Systemic pre- and post-stroke treatment with C21 reduces the neurological deficits and cerebral injury produced by ET-1 induced MCAO

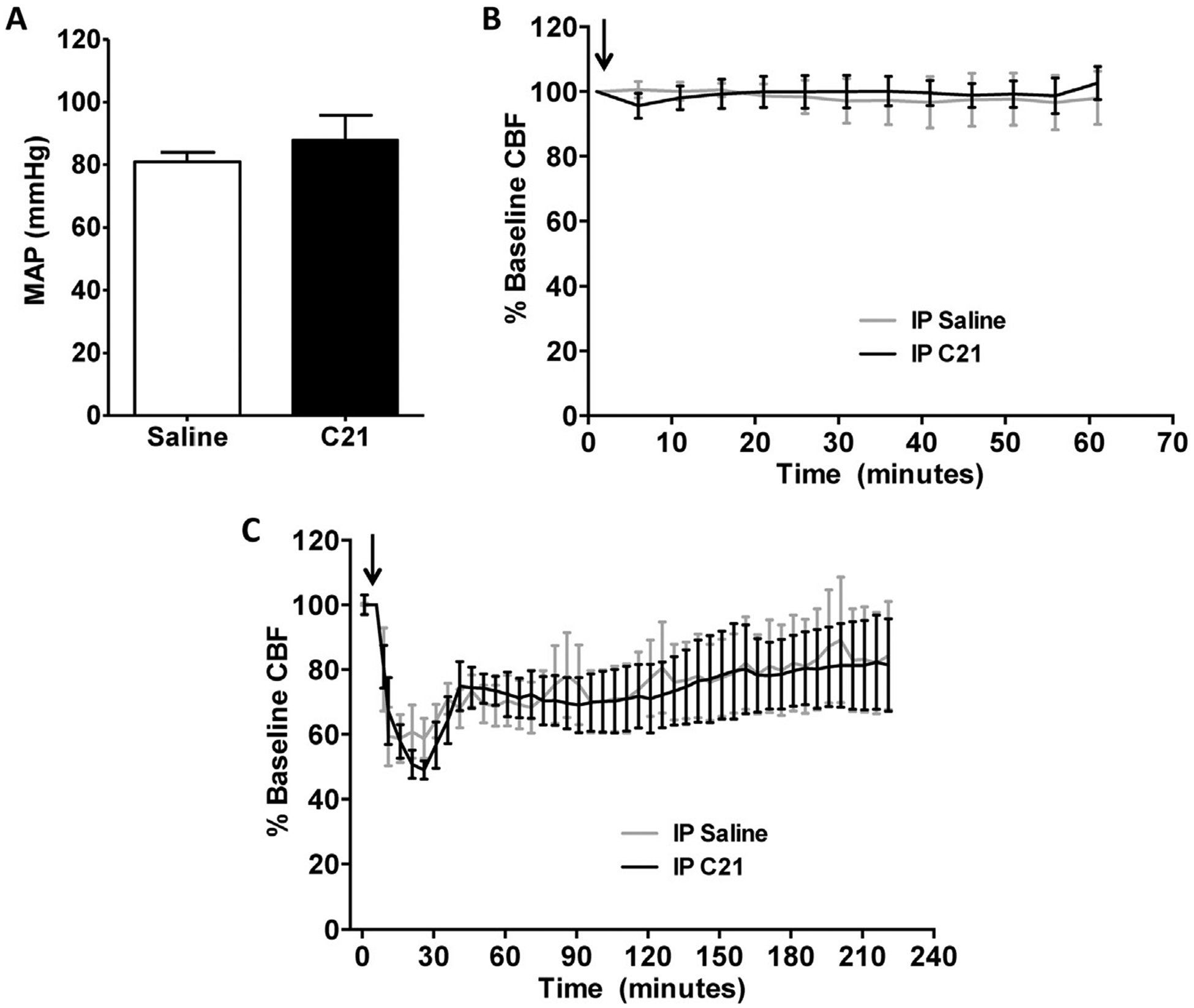

IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg or 0.1 mg/kg) into rats pre- (2 h) and post- (4, 24 and 48 h) ET-1 induced MCAO as described in Experiment 2 in the Methods significantly decreased the cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits (as measured by the Bederson examination) when compared with control (0.9% saline injected) rats (Fig. 2). A similar although non-significant beneficial trend was identified using the Garcia examination (Fig. 2). Since 0.1 mg/kg C21 exerted no greater cerebroprotective action than 0.03 mg/kg C21, the lower dose of this drug was used in all subsequent experiments. We also demonstrated, as per Experiments 3 and 4 (Methods), that IP injection of 0.03 mg/kg C21 did not alter baseline MAP or CBF (Fig. 3A, B). In a further set of rats, C21 (0.03 mg/kg) was injected via the IP route 2 h prior to ET-1 induced MCAO and CBF was measured 5 min before and for 4 h after stroke, as described in Experiment 4 (Methods). The data in Fig. 3C demonstrate that C21 did not alter the ET-1 induced reduction in CBF or the recovery towards baseline over the next 4 h. Importantly, this suggests that the observed beneficial actions of C21 are not a result of antagonizing or offsetting the actions of ET-1 to elicit vasoconstriction and reduce CBF.

Fig. 2.

Peripheral pre- and post-stroke treatment with C21 is cerebroprotective. Rats were injected IP with C21 (0.03 mg/kg [n = 11] or 0.1 mg/kg [n = 10]) or saline (0.9%, n = 11) 2 h prior to, as well as 4, 24, and 48 h following MCAO induction. (A) Bar graphs showing % cerebral infarct size and (B) representative brain sections from each treatment condition. (C), (D) are data from Bederson and Garcia Neurological Exams, respectively. Data are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. saline control (one way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for panel A, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s Multiple Comparison analysis for panels C and D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of peripherally administered C21 on blood pressure and CBF. (A) Rats received a single IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg, n = 6) or saline (0.9%, n = 6). Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was measured 30 min after injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM, and no significant difference was detected (unpaired t-test). (B) Rats were administered a single IP injection of C21 (0.03 mg/kg, n = 4) or 0.9% saline (n = 4), followed by analysis of CBF for 60 min. Arrow indicates C21 or 0.9% saline injection. (C) Rats were injected IP with C21 (0.03 mg/kg, n = 4) or 0.9% saline (n = 6) 2 h prior to MCAO induction. Graphs are 5 min averages of continuous flow recordings normalized to a 5 min pre-stroke baseline. Arrow indicates ET-1 injection. For panels (B) and (C) graphs are 5 min averages of continuous flow recordings normalized toa5 min pre-stroke baseline, and data are presented as means ± SEM. No significant differences exist between C21 and 0.9% saline treatment groups at any time point (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA).

3.3. Systemic post-stroke treatment with C21 reduces the neurological deficits and cerebral injury produced by ET-1 induced MCAO

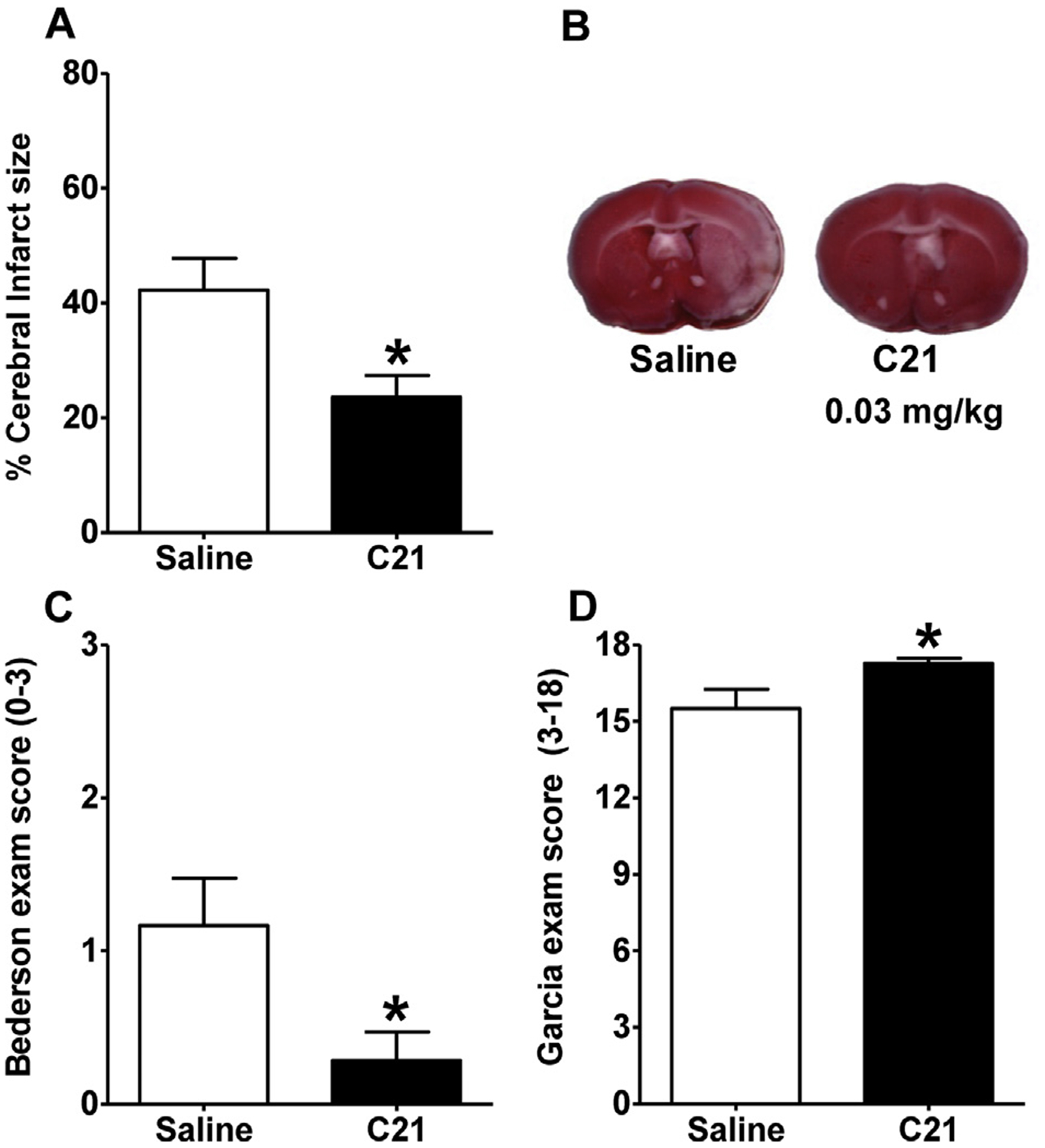

Administration of C21 (0.03 mg/kg) via the IP route 4, 24 and 48 h after MCAO induction, as described in Experiment 5 of the Methods, significantly decreased the cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits when compared with control rats (Fig. 4). To determine whether the cerebroprotective properties of systemically applied C21 are a direct result of an agonist effect via AT2R, we tested the effects of ICV infusion of the AT2R antagonist PD123319 (0.3 μg/μl/h) on the cerebroprotective action of C21 administered IP post-MCAO, as described in Experiment 6 (Methods). IP post-MCAO only treatment with C21 significantly decreased the cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits when compared with control rats (Fig. 5), consistent with the data in Fig. 4. Co-treatment with PD123319 infused ICV eliminated the cerebroprotective effect of systemically administered C21 as assessed by measurement of cerebral infarct size, as well as neurological examinations (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Peripheral treatment with C21 at 4, 24 and 48 h post-stroke is cerebroprotective. Rats were injected IP with either C21 (0.03 mg/kg, n = 7) or saline (0.9%, n = 6) at 4, 24, and 48 h following MCAO induction. (A) Bar graphs showing % infarcted gray matter and (B) representative brain sections from each treatment condition. (C), (D) are data from Bederson and Garcia Neurological Exams, respectively. Data are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. saline control (unpaired t-test for panel A or Mann Whitney test for panels C and D).

Fig. 5.

Cerebroprotective effect of C21 is abolished by PD123319. Rats were pre-treated with PD123319 (PD; 0.3 μg/μl/h) or aCSF via ICV infusion for 7 days prior to ET-1 induced MCAO. IP injections with either C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or 0.9% saline were administered at 4, 24, and 48 h following MCAO induction in both pre-treatment groups. (A) Bar graphs showing % cerebral infarct size and (B) representative brain sections from each treatment condition. (C), (D) are data from Bederson and Garcia Neurological Exams, respectively. Data are means ± SEM from 14 (aCSF/saline), 17 (aCSF/C21), 8 (PD/saline) and 8 (PD/C21) treated rats. *p < 0.05 vs. saline control (one way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s analysis for panel A, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s Multiple Comparison analysis for panels C and D).

3.4. Effects of IP post-stroke treatment with C21 on the expression of pro-inflammatory genes within the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the ET-1 induced MCAO

Because pro-inflammatory cytokines (PIC) and iNOS are induced following cerebral infarction and contribute to neuronal damage (Lee et al., 2005; Nakashima et al., 1995; Patel et al., 2013), we tested the effects of C21 administered IP post-stroke on the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the ET-1 induced MCAO. We chose to analyze gene expression 24 h post-MCAO, as mRNA analyses in the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the stroke performed at later time points post-MCAO proved less reliable (data not shown). Thus, we administered C21 (0.03 mg/kg) IP at 4 and 12 h post-stroke, as described in Experiment 7 (Methods). This treatment strategy with C21 was as effective in producing a cerebroprotective action (Fig. 6) as when it was administered 4, 24 and 48 h post ET-1 induced MCAO (Figs. 4 and 5). qRT-PCR analyses revealed that ET-1 induced MCAO elicited significant increases in the levels of mRNAs for CD11b (marker for monocytes/microglia activation), GFAP (marker for astrogliosis), CCL2 (marker of monocyte/microglial recruitment) and CCR2 (receptor for CCL2) when compared with rats that underwent sham MCAO (Fig. 7). The increases in CCL2 and CCR2 mRNAs were significantly reduced in the rats treated with C21 (Fig. 7). While there was a trend for CD11b and GFAP mRNAs to be reduced in the C21-treated rats, the effects of this AT2R agonist were not significant (Fig. 7). In addition, C21 treatment did not alter the increase in the level of mRNA for MPO (neutrophil marker) (not shown). The levels of iNOS, eNOS, IL-1α, IL-1β mRNAs (Fig. 8) and IL-6 mRNA (not shown) were all significantly increased in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex at 24 h post ET-1 induced MCAO, compared with sham MCAO rats. The level of iNOS mRNA was significantly reduced in the C21-treated rats, but there were no significant effects on the other genes tested (eNOS, IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-6 mRNAs).

Fig. 6.

Peripheral treatment with C21 at 4 and 12 h post-stroke is cerebroprotective. Rats were injected IP with either C21 (0.03 mg/kg, n = 6) or saline (0.9%, n = 6) at 4 and 12 h following MCAO induction. Twenty-four hours post-MCAO, rats underwent neurological testing via the Bederson and Garcia tests, and then were euthanized. Panels (A), (B) and (C) are the % cerebral infarct size, Bederson and Garcia scores respectively. Data are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. saline control (unpaired t-test for panel A or Mann Whitney test for panels B and C).

Fig. 7.

Peripheral post-stroke administration of C21 reduces CCL2 and CCR2 mRNAs in the cerebral cortex. Rats were injected IP with C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or saline (0.9%) at 4 and 12 h following MCAO induction by ET-1 or sham stroke. One-day post-MCAO, the ipsilateral cerebral cortex was used for qRT-PCR analyses. Shown are the respective levels of CD11b, GFAP, CCL2 and CCR2 mRNAs in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex in rats that underwent MCAO or sham stroke plus IP C21 or saline treatments. Data (normalized against GAPDH) are means ± SEM from 4 to 8 rats per treatment group. *p < 0.05 vs. respective sham stroke control; ψp < 0.05 vs. rats that underwent MCAO and IP saline treatment (one way ANOVA with Newman–Keuls analysis).

Fig. 8.

Peripheral post-stroke administration of C21 reduces iNOS mRNA in the cerebral cortex. Rats were injected IP with C21 (0.03 mg/kg) or saline (0.9%) at 4 and 12 h following MCAO induction by ET-1 or sham stroke. One-day post-MCAO, the ipsilateral cerebral cortex was used for qRT-PCR analyses. Shown are the respective levels of iNOS, eNOS, IL-1α and IL-1β mRNAs in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex in rats that underwent MCAO or sham stroke plus IP C21 or saline treatments. Data (normalized against GAPDH) are means ± SEM from 4 to 8 rats per treatment group. *p < 0.05 vs. respective sham stroke control; ψp < 0.05 vs. rats that underwent MCAO and IP saline treatment (one way ANOVA with Newman–Keuls analysis).

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that administration of the AT2R agonist C21 at a dose that is selective for AT2R (Jehle et al., 2012; Namsolleck et al., 2013; Paulis et al., 2012) is cerebroprotective during ischemic stroke. Central (ICV) or systemic (IP) pre-treatment with C21 limits the cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits due to ET-1 induced MCAO. Importantly, C21 administered systemically only after stroke also reduced cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits due to ET-1 induced MCAO, effects that were abolished by an AT2R antagonist. The data also indicate that these actions of C21 were independent of effects on CBF, but were associated with reductions in certain inflammatory markers in the brain. Thus, the data presented here are proof of principle that selective activation of AT2R post stroke via a systemic route can exert beneficial effects after ischemic stroke. Thus, the data provide evidence that direct activation of the AT2R with the non-peptide agonist C21 has potential utility for acute or preventative stroke therapy. In addition to these significant findings, our experiments raise multiple important questions about the mechanism and significance of AT2R mediated cerebroprotection.

Major questions raised by our results concern the locus and mechanism of C21 mediated cerebroprotection. Our previous studies on angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)], which exerts a similar reduction in cerebral infarct size and neurological deficits after ET-1 induced MCAO, suggested that the beneficial actions of this agent did not involve a cerebrovascular mechanism (Mecca et al., 2011). Similar to these findings, IP administration of C21 did not alter baseline CBF, nor did it alter the reduction in CBF elicited by ET-1 induced MCAO (Fig. 3). Additionally, the fact that C21 exerts cerebroprotection when administered 4 h post stroke, at which time cell death processes are underway, might suggest that the beneficial actions of this AT2R agonist do not involve a cerebrovascular mechanism. However, without a more detailed analysis of CBF using microspheres or magnetic resonance imaging of regional cerebral circulation we cannot exclude the possibility that C21 is acting to improve stroke penumbral circulation. Regarding an alternative cerebroprotective mechanism, our data do demonstrate that C21 administered peripherally post stroke attenuated the increase in iNOS expression in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex following ET-1 induced MCAO. This finding is relevant because induction of iNOS in activated microglia and infiltrating leukocytes leads to subsequent generation of toxic levels of NO during the delayed events that contribute to neuronal death following cerebral ischemia (Nakashima et al., 1995; Patel et al., 2013). Our data indicate that the increases in MPO, GFAP and CD11b mRNAs that occur in the cerebral cortex post-stroke were not significantly altered in the C21-treated rats, suggesting that it does not alter neutrophil invasion, astrogliosis and microglial activation, respectively. Furthermore, the stroke-induced increases in PICs such as IL-1α and IL-1β, which are known to induce iNOS expression in the infarct zone (Patel et al., 2013), were not significantly altered in the C21-injected rats. However, the data presented here indicate that the increases in the levels of mRNAs for CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 elicited by ET-1 induced MCAO are significantly less in the C21 treated rats (Fig. 7). CCL2 is known to promote post stroke inflammation through monocyte and microglia recruitment (El Khoury et al., 2007; Schilling et al., 2009). Based on this, we might expect attenuation of the increased CD11b expression, which should represent both microglial and monocyte recruitment, and PICs that are secreted from these cells. While there was a tendency for CD11b and IL-1β mRNA expression to be attenuated in the cortex of C21-treated rats (Figs. 7 and 8), it is possible that significant changes would be detected at later time points post-stroke when the inflammatory response is more robust. Other possibilities are that C21 has an action downstream of PIC expression, and that an alternate molecule other than the PICs tested is involved in the increased iNOS expression that occurs during ischemic stroke. Further experiments examining the differential expression of the genes for CD11b and PICs over time will be necessary to fully elucidate the involvement of microglia/macrophages in the cerebroprotective mechanism of C21. These results also raise questions of AT2R cellular localization and C21 binding. Studies utilizing immunostaining and quantative PCR provide evidence that AT2R protein and mRNA is present in rat microglia (Miyoshi et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Pallares et al., 2008), and future experiments will determine the effects of C21 on the activation and migration of these cells.

Targeting the CNS with pharmacotherapy has proven difficult because the blood brain barrier (BBB) excludes many molecules and limits their activity centrally (Pardridge, 2005). Most small molecules that cross the BBB have a molecular mass less than 400–500 g/mol and are very lipophilic (Ghose et al., 1999). These concerns were the rationale for our initial experiments where C21 was delivered directly into the cerebral ventricle. C21 is hydrophilic and has a molecular mass of 497.6 g/mol, and there is minimal transport of this drug across the BBB after peripheral administration (Shraim et al., 2011). However, it is clear that BBB disruption occurs following ischemic insult (Yang and Rosenberg, 2011), and based on our data a peripheral treatment strategy would likely be effective. Further experiments will elicit the window available for effective cerebroprotection when C21 is administered as a post-stroke therapy.

Several strengths of this study should be addressed as it offers advantages to previous investigations of AT2R stimulation for cerebroprotection. For example, previous studies indicated that the peptide AT2R agonist, CGP42112, was cerebroprotective when administered centrally prior to or after stroke (McCarthy et al., 2009, 2012). Our experiments have included a post-stroke systemic treatment regimen with C21 that would be clinically significant for human stroke treatment. It is also noteworthy that C21 is an orally active compound (Steckelings et al., 2011).

In conclusion, the current work demonstrates that administration of the selective AT2R agonist C21, post insult, results in significant beneficial actions against ischemic stroke. Importantly, this cerebroprotective action of AT2R agonism can be obtained when the C21 is applied systemically post stroke over a time frame that may be of therapeutic value. Thus, the current work provides important new data that activation of cerebral AT2R may be a viable therapeutic avenue for ischemia-induced cerebrovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate (09GRNT2060421), the American Medical Association, and the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Adam Mecca was a NIH/NINDS, Pre-doctoral Fellow (F30 NS-060335). Robert Regenhardt received Pre-doctoral Fellowship support from the University of Florida Multidisciplinary Training Program in Hypertension (T32 HL-083810). Douglas Bennion is the recipient of an American Heart Association Greater Southeast Pre-doctoral Fellowship (12PRE11940010). Support from the University of Florida University Scholars Program (Jason Joseph, Fiona Desland, Neal Patel) and from the University of Florida HHMI Science for Life program (Jason Joseph, Neal Patel, David Pioquinto) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H, 1986. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke 17, 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosnyak S, Welungoda IK, Hallberg A, Alterman M, Widdop RE, Jones ES, 2010. Stimulation of angiotensin AT2 receptors by the non-peptide agonist, Compound 21, evokes vasodepressor effects in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol 159 (3), 709–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosnyak S, Jones ES, Christopoulos A, Aguilar MI, Thomas WG, Widdop RE, 2011. Relative affinity of angiotensin peptides and novel ligands at AT1 and AT2 receptors. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 121 (7), 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, 2013. Newly discovered components and actions of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 62 (5), 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote F, Do TH, Laflamme L, Gallo JM, Gallo-Payet N, 1999. Activation of the AT(2) receptor of angiotensin II induces neurite outgrowth and cell migration in microexplant cultures of the cerebellum. J. Biol. Chem 274, 31686–31692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhande I, Ali Q, Hussain T, 2013. Proximal tubule angiotensin AT2 receptors mediate an anti-inflammatory response via interleukin-10: role in renoprotection in obese rats. Hypertension 61 (6), 1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD, 2007. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat. Med 13, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure S, Bureau A, Oudart N, Javellaud J, Fournier A, Achard JM, 2008. Protective effect of candesartan in experimental ischemic stroke in the rat mediated by AT2 and AT4 receptors. J. Hypertens 26 (10), 2008–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Bradford CN, Mecca AP, Sumners C, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK, 2010. Therapeutic implications of the vasoprotective axis of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension 55, 207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zhang H, Le KD, Chao J, Gao L, 2011. Activation of central angiotensin type 2 receptors suppresses norepinephrine excretion and blood pressure in conscious rats. Am. J. Hypertens 24 (6), 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JH, Wagner S, Liu KF, Hu XJ, 1995. Neurological deficit and extent of neuronal necrosis attributable to middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Statistical validation. Stroke 26, 627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelosa P, Pignieri A, Fandriks L, de Gasparo M, Hallberg A, Banfi C, Castiglioni L, Turolo L, Guerrini U, Tremoli E, Sironi L, 2009. Stimulation of AT2 receptor exerts beneficial effects in stroke-prone rats: focus on renal damage. J. Hypertens 27, 2444–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose AK, Viswanadhan VN, Wendoloski JJ, 1999. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem 1, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Liu HW, Chen R, Ide A, Okamoto S, Hata R, Sakanaka M, Shiuchi T, Horiuchi M, 2004. Possible inhibition of focal cerebral ischemia by angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation. Circulation 110, 843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehle AB, Xu Y, Dimaria JM, French BA, Epstein FH, Berr SS, Roy RJ, Kemp BA, Carey RM, Kramer CM, 2012. A nonpeptide angiotensin II type 2 receptor agonist does not attenuate postmyocardial infarction left ventricular remodeling in mice. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol 59 (4), 363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagiyama T, Glushakov AV, Sumners C, Roose B, Dennis DM, Phillips MI, Ozcan MS, Seubert CN, Martynyuk AE, 2004. Neuroprotective action of halogenated derivatives of L-phenylalanine. Stroke 35 (5), 1192–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Cho GS, Kim HJ, Lim JH, Oh YK, Nam W, Chung JH, Kim WK, 2005. Accelerated cerebral ischemic injury by activated macrophages/microglia after lipopolysaccharide microinjection into rat corpus callosum. Glia 50, 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BI, Benessiano J, Henrion D, Caputo L, Heymes C, Duriez M, Poitevin P, Samuel JL, 1996. Chronic blockade of AT2-subtype receptors prevents the effect of angiotensin II on the rat vascular structure. J. Clin. Investig 98, 418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Culman J, Hortnagl H, Zhao Y, Gerova N, Timm M, Blume A, Zimmermann M, Seidel K, Dirnagl U, Unger T, 2005. Angiotensin AT2 receptor protects against cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal injury. FASEB J. 19, 617–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, He YY, Wu G, Khan M, Hsu CY, 1993. Effect of brain edema on infarct volume in a focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Stroke 24 (1), 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Zhu YZ, Wong PT, 2005. Neuroprotective effects of candesartan against cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuroreport 16, 1963–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino I, Shibata K, Ohgami Y, Fujiwara M, Furukawa T, 1996. Transient upregulation of the AT2 receptor mRNA level after global ischemia in the rat brain. Neuropeptides 30, 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matavelli LC, Huang J, Siragy HM, 2011. Angiotensin AT2 receptor stimulation inhibits early renal inflammation in renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 57, 308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecca AP, Regenhardt RW, O’Connor TE, Joseph JP, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ, Sumners C, 2011. Cerebroprotection by angiotensin-(1–7) in endothelin-1-induced ischaemic stroke. Exp. Physiol 96, 1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CA, Vinh A, Callaway JK, Widdop RE, 2009. Angiotensin AT2 receptor stimulation causes neuroprotection in a conscious rat model of stroke. Stroke 40, 1482–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CA, Vinh A, Broughton BR, Sobey CG, Callaway JK, Widdop RE, 2012. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation initiated after stroke causes neuroprotection in conscious rats. Hypertension 60 (6), 1531–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi M, Miyano K, Moriyama N, Taniguchi M, Watanabe T, 2008. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of rat microglial cells by suppressing nuclear factor kappaB and activator protein-1 activation. Eur. J. Neurosci 27, 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima MN, Yamashita K, Kataoka Y, Yamashita YS, Niwa M, 1995. Time course of nitric oxide synthase activity in neuronal, glial, and endothelial cells of rat striatum following focal cerebral ischemia. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 15, 341–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namsolleck P, Boato F, Schwengel K, Paulis L, Matho KS, Geurts N, Thöne-Reineke C, Lucht K, Seidel K, Hallberg A, Dahlöf B, Unger T, Hendrix S, Steckelings UM, 2013. AT2-receptor stimulation enhances axonal plasticity after spinal cord injury by upregulating BDNF expression. Neurobiol. Dis 51, 177–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM, 2005. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx 2, 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AR, Ritzel R, McCullough LD, Liu F, 2013. Microglia and ischemic stroke: a double-edged sword. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol 5 (2), 73–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulis L, Becker ST, Lucht K, Schwengel K, Slavic S, Kaschina E, Thöne-Reineke C, Dahlöf B, Baulmann J, Unger T, Steckelings UM, 2012. Direct angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation in Nω-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester-induced hypertension: the effect on pulse wave velocity and aortic remodeling. Hypertension 59 (2), 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenhardt RW, Desland F, Mecca AP, Pioquinto DJ, Afzal A, Mocco J, Sumners C, 2013. Anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin-(1–7) in ischemic stroke. Neuropharmacology 71, 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman A, Leibowitz A, Yamamoto N, Rautureau Y, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL, 2012. Angiotensin type 2 receptor agonist Compound 21 reduces vascular injury and myocardial fibrosis in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 59 (2), 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke K, Lucius R, Reinecke A, Rickert U, Herdegen T, Unger T, 2003. Angiotensin II accelerates functional recovery in the rat sciatic nerve in vivo: role of the AT2 receptor and the transcription factor NF-kappaB. FASEB J. 17, 2094–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rey P, Parga JA, Munoz A, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL, 2008. Brain angiotensin enhances dopaminergic cell death via microglial activation and NADPH-derived ROS. Neurobiol. Dis 31, 58–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling M, Strecker JK, Schabitz WR, Ringelstein EB, Kiefer R, 2009. Effects of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 on blood-borne cell recruitment after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Neuroscience 161, 806–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shraim N, Mertens B, Clinckers R, Sarre S, Michotte Y, Van Eeckhaut A, 2011. Microbore liquid chromatography with UV detection to study the in vivo passage of Compound 21, a non-peptidergic AT receptor agonist, to the striatum in rats. J. Neurosci. Methods 202, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckelings UM, Larhed M, Hallberg A, Widdop RE, Jones ES, Wallinder C, Namsolleck P, Dahlof B, Unger T, 2011. Non-peptide AT2-receptor agonists. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 11, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Wallinder C, Plouffe B, Beaudry H, Mahalingam AK, Wu X, Johansson B, Holm M, Botoros M, Karlén A, Pettersson A, Nyberg F, Fändriks L, Gallo-Payet N, Hallberg A, Alterman M, 2004. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of the first selective nonpeptide AT2 receptor agonist. J. Med. Chem 47 (24), 5995–6008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Rosenberg GA, 2011. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in acute and chronic cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 42 (11), 3323–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]