Abstract

Background & Aims:

Liver regeneration is impaired in mice with hepatocyte-specific deficiencies in microRNA (miRNA) processing, but it is not clear which miRNAs regulate this process. We developed a high-throughput screen to identify miRNAs that regulate hepatocyte repopulation following toxic liver injury using Fah−/− mice.

Methods:

We constructed plasmid pools encoding more than 30,000 tough decoy iRNA inhibitors (hairpin nucleic acids designed to specifically inhibit interactions between miRNAs s and their targets) to target hepatocyte miRNAs in a pairwise manner. The plasmid libraries were delivered to hepatocytes in Fah−/− mice at time of liver injury via hydrodynamic tail vein injection. Integrated transgene-containing transposons were quantified following liver repopulation via high-throughput sequencing. Changes in polysome-bound transcripts following miRNA inhibition were determined using translating ribosome affinity purification followed by high-throughput sequencing.

Results:

Analyses of tough decoy abundance in hepatocyte genomic DNA and input plasmid pools identified several thousand miRNA inhibitors that were significantly lost or gained following repopulation. We classified a subset of miRNA binding sites as those that have strong effects on liver repopulation, implicating the targeted hepatocyte miRNAs as regulators of this process. We then generated a high-content map of pairwise interactions between 171 miRNA-binding sites and identified synergistic and redundant effects.

Conclusions:

We developed a screen to identify miRNAs required for liver regeneration after injury in live mice.

Keywords: TuD, MBS, high-throughput screen, post-transcriptional regulation

Introduction:

Hepatocytes function as the nexus of numerous essential metabolic pathways and are frequently exposed to environmental toxins and viruses. The ability of the liver parenchyma to restore organ mass in response to tissue injury is highly conserved among vertebrates. Upon injury, local and systemic cytokines and growth factors, such as interleukin 6 and hepatocyte growth factor, signal quiescent hepatocytes to temporarily pause homeostatic functions and re-enter the cell cycle.1 Harnessing this natural ability for recovery is a topic of clinical importance, as organ transplantation is the only current remedy for fulminant liver failure.

The repopulating hepatocyte transcriptome is highly dynamic2,3 but the importance of post-transcriptional gene regulation is poorly understood. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a major post-transcriptional regulatory component, controlling mRNA stability and translational efficiency by recruiting the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to target transcripts.4 Previous studies in mice utilizing hepatocyte-specific deletion of Dicer have shown that miRNAs are required for normal liver development and homeostasis.5–7 Furthermore, mice with a hepatocyte-specific deficiency in miRNA processing exhibit impaired liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy.8 Yet, no large-scale or combinatorial functional mapping during liver repopulation has been performed to date. Furthermore, interactions between miRNAs during this process are largely unknown.

Tough decoys (‘TuDs’) are potent miRNA inhibitors that can target individual or multiple miRNAs in mammalian cells with high specificity.9–11 TuDs are single-stranded RNAs that contain one or more miRNA-binding sites (MBSs), each designed to base-pair with a mature miRNA, thereby inhibiting interactions of the miRNA with its endogenous mRNA targets (Supplementary Figure 1A). Evidence that TuDs induce nucleotide trimming and tailing of targeted miRNAs suggests that a single MBS can inactivate multiple miRNA molecules in succession.12

A pertinent system to study liver repopulation is the FAH-deficient (Fah−/−) mouse model of hereditary tyrosinemia type I (HTI), which recapitulates salient features of the condition.13 The Fah gene encodes fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH), which catalyzes the removal of a toxic intermediate of tyrosine catabolism. A strong selection pressure for hepatocytes expressing a Fah transgene to survive and expand upon the induction of injury allows co-expressed genes to be screened in parallel for effects on hepatocyte repopulation in vivo.14–17

Utilizing the Fah−/− model, we developed a large-scale screening platform to map the regulation of liver repopulation by miRNAs. We constructed TuD miRNA inhibitors targeting the 171 most abundant RISC-bound hepatocyte miRNAs. By sequential ligation of pooled miRNA binding sequences to a stem-loop scaffold, we created libraries of over 30,000 unique single- and dual-targeting TuDs to perform the first high-throughput combinatorial inhibition screen to map miRNA function in vivo. This approach uncovered previously unknown miRNA regulatory networks active during liver repopulation. The data herein broadens our understanding of hepatocyte post-transcriptional control in the context of liver repopulation and may ultimately aid advancements in therapeutic stimulation of native liver recovery.

METHODS

Fah−/− mouse model of hereditary tyrosinemia type I

C57BL/6j Fah−/− mice were a gift from Markus Grompe and were maintained on 7.5 μg/mL nitisinone in H2O until hydrodynamic tail vein injection of plasmids13. Animal experiments were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 805623).

MicroRNA-binding site (MBS) design and TuD library generation

MicroRNAs were selected using a list of AGO2-bound miRNAs obtained by high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation in mouse livers following partial hepatectomy.3 One MBS was generated for each confidently-annotated miRNA represented by at least 0.01% of the total reads at any time point and devoid of a stretch of uracils of length four or more (n=171). Three scrambled-sequence non-targeting MBSs and three MBSs targeting miRNAs detected at fewer than two reads per million in the AGO2-bound fraction of the quiescent or regenerating mouse liver (miR-1a-1–5p, miR-670–3p, and miR-880–5p) were included as negative controls. Oligonucleotides were purchased as ssDNA, annealed and combined to generate a MBS pool containing 177 unique dsDNA MBSs, and ligated sequentially into pBT264-MBSacceptor (Supplementary Table 1). TuDs from the pBT264 pool were ligated to pKT2-Fah-U6-TuDacceptor-pT or pKT2-Fah-U6-TuDacceptor-tail to create the pKT2-Fah-TuDstd (TuDstd) and pKT2-Fah-TuDtail (TuDtail) libraries, respectively. Endotoxin-free TuD library plasmid preparations were obtained using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen). Individual pKT2-Fah-TuDstd, pKT2-Fah-TuDtail, and pKT2-Fah-eGFP-L10a-TuDstd plasmids containing single- or dual-targeting TuDs were derived by sequentially ligating single MBS inserts into the TuD scaffold of pBT264-MBSacceptor, followed by transfer into pKT2-Fah plasmids.

Cell culture and dual luciferase assays

Hepa 1–6 mouse hepatoma cells (ATCC CRL-1830) were maintained on culture-treated plastic in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin. For luciferase experiments, cells were plated on 24-well tissue culture dishes and co-transfected with 10 ng of pMiRCheck2 miRNA sensor plasmid and 500 ng of pKT2-Fah-TuDstd, pKT2-Fah-TuDtail, or pGeneClip (Promega) plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Invitrogen). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity was determined 24 (TuD) or 48 h (pGeneClip) post-transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

MicroRNA inhibition in the mouse liver

The TuDstd library or TuDtail library (10 μg in Ringer’s lactated solution; fluid volume was equal to 10% of recipient mouse weight) was delivered to male Fah−/− mice (age 8–12 weeks) via hydrodynamic tail vein injection. Nitisinone was withdrawn to induce hepatocyte toxicity and repopulation. Four weeks post-injection, mice were euthanized and livers excised. Genomic DNA was isolated from 400 mg of tissue collected from multiple liver lobes and remaining tissue was processed for histological analyses. For the TRAP-Seq experiment, pKT2-Fah-eGFP-L10a-TuDstd plasmids expressing either a TuD with two control MBSs (miR-880–5p and scramble-3) or a TuD with a miR-374b-5p MBS in the 3’ position (miR-880–5p and miR-374b-5p) were delivered to male Fah−/− mice (age 4 months) as above and repopulation induced by nitisinone withdrawal. Two weeks post-injection, mice were euthanized and livers isolated for analysis. In the TuD competition experiment, pools containing approximately 1% each of the TRAP-Seq plasmids and 98% of pKT2-Fah plasmid were delivered to female Fah−/− mice (age 2 months) as above and repopulation induced by nitisinone withdrawal. Mice were euthanized four weeks after injection and liver gDNA was isolated for sequencing.

TRAP-Seq

Repopulating hepatocyte-specific messenger RNA was isolated by translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) as previously described.18,19 Briefly, 500 mg of liver homogenate was incubated with magnetic-bound anti-GFP antibodies (Htz-GFP-19F7 and Htz-GFP-19C8, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Monoclonal Antibody Facility, New York, NY) and mRNA bound to the GFP-tagged ribosomal subunit protein L10a was purified (Absolutely RNA Microprep Kit, Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE). RNA-Seq libraries were prepared from 1 μg of purified RNA using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina with NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England BioLabs). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 (75 cycles). Following alignment to the GRCm38/mm10 genome assembly using STAR v2.5.2a, raw read counts were converted to transcripts per kilobase million (TPM).

Immunohistology

Paraffin sections were labeled with antibodies according to standard procedures. Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer (rabbit anti-FAH, 1:200; goat anti-GFP antibody (Abcam #Ab6673), 1:500; rabbit anti-MEX3C antibody (Proteintech 22882–1-AP), 1:100).

Differential TuD abundance

To generate TuD read counts, we generated a custom TuD dictionary from a dictionary of 31,329 potential TuD sequences by removing stem sequence, trimming to 75 nucleotides, and removing the invariable loop sequence. The dictionary was expanded to allow a single mismatch across the trimmed sequences. Reads corresponding to MBS1 and MBS2 were concatenated and mapped to the TuD name (MBS pair). We used the mapped raw TuD sequencing reads to determine differential TuD sequence abundance following liver repopulation using the The DESeq2 algorithm20. A Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value (FDR) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inhibition of hepatocyte microRNA activity using tough decoys

To perform large-scale miRNA inhibition screens in the Fah−/− mouse model of liver repopulation, we generated expression plasmids containing the mouse Fah cDNA and U6 promoter-driven TuD cassettes (Figure 1A). Each Fah-TuD plasmid also encodes the Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposase and transposable elements, facilitating stable integration of the Fah and TuD cassettes into the hepatocyte genome. Expression of shRNAs from strong RNA Pol III promoters can induce hepatotoxicity in vivo by oversaturating the exportin-5 pathway.21 Because RNA Pol III-driven TuD expression might also be toxic to hepatocytes, we designed a second TuD expression cassette to attenuate transcript levels, by removing the termination signal (poly(T); ‘pT’) immediately adjacent to the TuD sequence to allow transcription to proceed to a downstream termination signal.

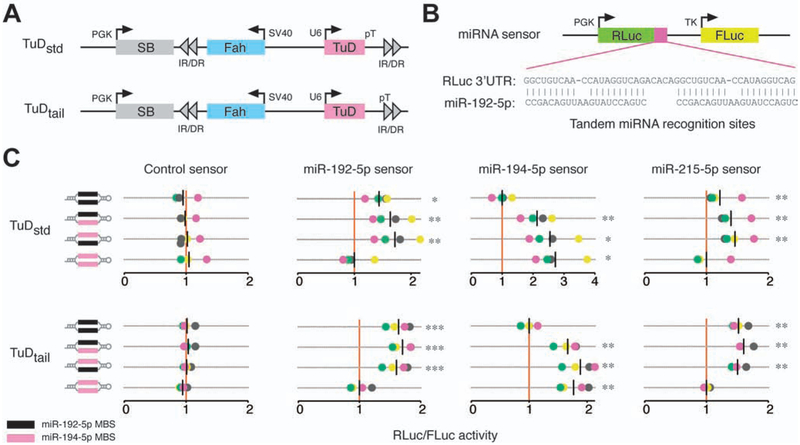

Figure 1.

Inhibition of microRNA activity via tough decoy expression. (A) Fah plasmids expressing TuDs from a U6 promoter as standard hairpins (TuDstd) or with extended 3’ sequences (TuDtail). Plasmids encode sleeping beauty (SB) transposase and inverted repeat/direct repeat (IR/DR) sequences for genomic integration. (B) MiRNA sensor plasmids encoding a Renilla luciferase (RLuc) cDNA with miRNA binding sites in the 3’UTR and a non-targeted firefly luciferase (FLuc) cDNA. (C) Dual luciferase assays in mouse Hepa 1–6 cells co-transfected with Fah plasmids encoding TuDs directed against the miRNA-194/192/215 family and miRNA sensor plasmids. The RLuc/FLuc ratios for miRNA sensors are scaled such that the mean of the sensor-specific control TuD is one (red vertical line). Assays were performed in quadruplicate; data points are colored by replicate. Black vertical lines indicate the mean luciferase ratio of each TuD. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnet’s test for multiple comparisons.

To determine if a single TuD can inhibit the activity of two different miRNAs when expressed from a transposon containing the Fah cDNA, we performed dual-luciferase reporter experiments in Hepa 1–6 hepatoma cells in vitro (Figure 1B). Single- or dual-targeting TuDs directed against members of the miR-194/192/215 family and expressed from either Fah-TuD plasmid significantly increased the ratio of Renilla luciferase (RLuc) to firefly luciferase (FLuc) activities (Figure 1C). Notably, dual-targeting TuDs displayed miRNA inhibition comparable in magnitude to the associated one-wise TuD constructs, suggesting that TuD levels were not limiting in either expression platform. As expected, TuDs targeting miR-192 also de-repressed a miR-215 sensor due to nearly identical miRNA sequences. Based on these findings, we reasoned that TuDs can be employed to effectively inhibit endogenous hepatocyte miRNAs in a pairwise manner in vivo.

Generation of pairwise tough decoy libraries for a massively parallel microRNA inhibition screen

To perform a massively-parallel screen of miRNA function during liver repopulation, we began by selecting relevant miRNAs to be targeted using our previously-published dataset of miRNAs bound by Argonaute2 (AGO2) in the quiescent mouse liver and following partial hepatectomy3. For inclusion in our screen, we set a minimum threshold of 0.01% of total AGO2-bound miRNA reads at any of four time points during liver regeneration (quiescent liver and 1, 36, and 48 hours after partial hepatectomy). We excluded miRNAs containing a poly(A) stretch of length four or greater, as a corresponding MBS would include a RNA Pol III termination signal.22 All together, our MBS pool targeted 171 confidently annotated mature hepatocyte-relevant miRNAs. MBSs targeting three scrambled-sequence miRNAs (scramble-1, −2, −3) and three miRNAs present below two reads per million in the partial hepatectomy dataset (miR-1a-1–5p, miR-670–3p and miR-880–5p) served as negative controls, giving a total pool size of 177 MBSs (Supplementary Table 1). The TuD library was assembled en masse via sequential ligation of the MBS pool to a storage plasmid containing TuD stem and loop sequences (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 1B). This library, containing up to 31,329 possible pairwise combinations of 177 unique MBSs, was subcloned into our Fah expression plasmids to test their effect on hepatocyte repopulation (Figure 2A).

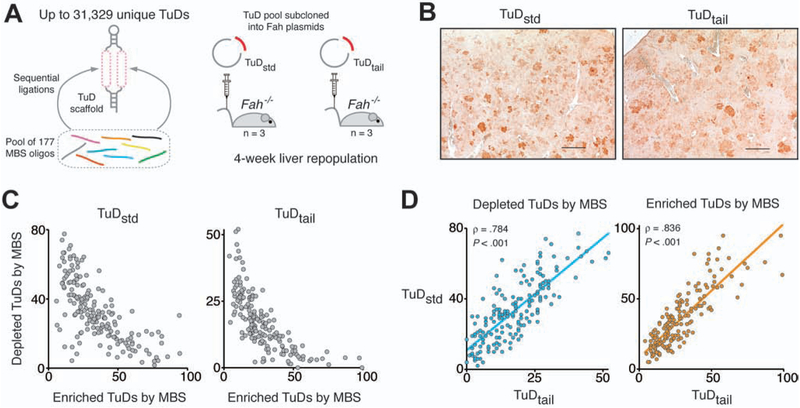

Figure 2.

High-content pairwise miRNA inhibition in vivo. (A) Fah/TuD plasmid libraries were assembled by pooled ligations and administered to male Fah−/− mice. Livers were analyzed four weeks after injection. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of Fah−/− mouse liver tissue showed numerous FAH-positive repopulation nodules. Scale bar, 500 μm. (C) MBS tallies in enriched and depleted TuDs were negatively correlated in the TuDstd and TuDtail experiments. (D) Depleted (left panel) and enriched (right panel) MBS tallies were significantly correlated between experiments. ◻, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

High coverage of tough decoy libraries in the repopulating mouse liver

The TuD plasmid pools, termed ‘TuDstd’ (with pT) or ‘TuDtail’ (without pT) were administered to adult male Fah−/− mice (n=3 each) via hydrodynamic tail vein injection and nitisinone was withdrawn to induce liver repopulation by hepatocytes incorporating Fah-TuD transposons. Similar body weight profiles were observed for all animals (Supplementary Figure 2A). Four weeks after plasmid injection, mice were euthanized and liver tissue was collected for analysis. Abundant FAH-positive repopulation nodules were observed in all mice (Figure 2B).

To quantify TuD abundance, we sequenced TuD fragments amplified from liver genomic DNA (gDNA) and from the input plasmid pools. Using our strict mismatch criteria, approximately 95% of reads mapped to a TuD sequence. TuDstd and TuDtail plasmid libraries contained 30,817 and 30,846 (98.4% and 98.5%), respectively, of the 31,329 possible MBS combinations, indicating high cloning efficiency. Following liver repopulation, 30,317 and 30,796 (96.8% and 98.3%) TuDs were detected in liver gDNA samples (Supplementary Table 2). Notably, we observed significant correlations among replicates of the plasmid libraries and liver samples, attesting to the robustness of the assay (Supplementary Figure 2B,C). These data demonstrate that very large combinatorial libraries can be screened in vivo using the Fah−/− mouse model.

MicroRNAs regulate hepatocyte proliferation in vivo following toxic liver injury

Principal component analysis of sequencing reads showed a clear separation of liver and plasmid input replicates, suggesting that inhibition of specific miRNAs elicits substantial effects on hepatocyte repopulation (Supplementary Figure 2D). We used the differential TuD abundance between plasmid libraries and hepatocyte gDNA as a measure of miRNA impact on liver repopulation. To identify TuDs with altered abundance, we performed differential expression analysis using DESeq2.20 In TuDstd-injected animals, 5,969 TuDs (19.5%) had an adjusted P<0.05, whereas in TuDtail-injected animals, 3,981 TuDs (13.0%) were significantly altered in abundance after repopulation (Supplementary Figure 3A). Many MBSs displayed a strong bias towards either enrichment or depletion; individual MBS prevalence among the enriched and depleted TuD sets was inversely correlated (Figure 2C).

The observed fold change distributions were significantly correlated between libraries (Spearman’s rank correlation, P<.001) (Supplementary Figure 3B) and the distribution interquartile ranges were similar between the two experiments (0.60 and 0.56). The congruent overlap of enriched and depleted TuD sets was significantly greater than expected by chance (Supplementary Figure 3C) and the tallies of enriched and depleted TuDs for each MBS were significantly correlated between libraries (Figure 2D). These findings suggested that the immediate pT termination signal in the TuDstd experiment did not adversely affect repopulation, and that the findings of our screen were reproducible. To streamline subsequent analyses, we combined the two datasets; after removal of non-biological variation, correlation among all replicates was improved (Supplementary Figure 3D and E).

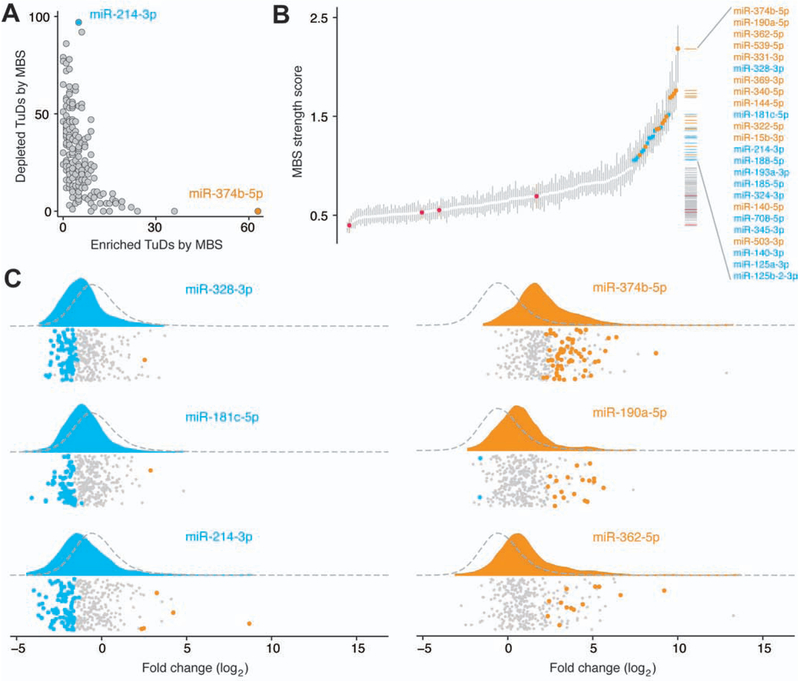

We identified significantly altered TuDs in the combined data set by comparing the log2 fold change values among animal replicates to the population of control TuDs (i.e. TuDs with a control MBS in both MBS positions). After correction for multiple testing, a total of 3,077 TuDs were significantly altered following repopulation, 2,579 (84%) of which were depleted (Supplementary Figure 3F). The most prevalent MBSs among depleted and enriched TuDs were directed against miR-214–3p and miR-374b-5p, respectively (Figure 3A), in agreement with our analysis prior to data set combination.

Figure 3.

MicroRNAs regulate repopulation following liver injury. (A) MBS tallies in enriched and depleted TuDs were negatively correlated in the combined data set. (B) Quantile plot of 174 individual MBS strength scores. Control MBS scores are shown in red. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Twenty four MBSs with strength scores above 1 are colored according to phenotypes above (orange) or below (blue) zero. (C) Raincloud plots of the log2 fold change distributions of TuDs containing the strongest MBSs with a negative phenotype (blue) and or a positive phenotype (orange). Kernel density plots are shaded according to the MBS phenotype. Dashed lines indicate the density plot of all TuDs not containing the specified MBS. Data points indicate each TuD detected containing the specified MBS and are colored by significance: depleted (blue), enriched (orange), or unchanged (gray) relative to non-targeting controls. Each distribution was significantly different from the remaining TuDs (P<.001).

To group MBSs according to their effects on liver repopulation, we performed hierarchical clustering of TuD log2 fold changes (Supplementary Figure 4A). As each MBS pairing can occur in two orientations (5’-AB-3’ and 5’-BA-3’), our heatmap is MBS order-specific, with rows indicating the 5’ position, and columns representing the 3’ position. In each orientation, three main clusters emerged, and their intersection demonstrated that MBS effects on liver repopulation were largely position-independent (Pearson’s χ2=45.4, P<.001; Supplementary Figure 4B). Across all pairwise MBS combinations, we observed a significant positive correlation of log2 fold change between TuD pairs (5’-AB-3’ and 5’-BA-3’) (Supplementary Figure 4C). In addition, each set of significant TuDs was more likely to contain both orientations of an MBS pairing than would be expected by chance (Supplementary Figure 4D). The individual MBSs present in significant TuDs did not display strong positional bias (Supplementary Figure 4E).

Defining individual miRNA binding site effects

To characterize individual MBS effects on liver repopulation, we assigned to each a ‘phenotype’ score, defined as the median log2 fold change among the subset of TuDs containing the MBS paired with one of six control MBSs, across all replicates. The lowest phenotype score was observed for the MBS targeting miR-214–3p, which was the most prevalent MBS within depleted TuDs (Supplementary Figure 5A). Similarly, the MBS targeting miR-374b-5p, the most prevalent MBS among enriched TuDs, was assigned the second highest phenotype score.

Next, we developed a metric to capture the ability of an MBS to affect liver repopulation in the presence of a second MBS. For each TuD, we assigned two MBS ‘strength scores’ based on the constituent MBS phenotypes and the observed TuD log2 fold-change. Each strength score is the ratio of the distance between MBS phenotypes and the distance between the MBS phenotype and the TuD log2 fold-change (Supplementary Figure 5B). For each MBS, an overall strength score was calculated as the median strength score for the MBS across all TuDs and replicates. The largest overall strength score was observed for miR-374b-5p (Figure 3B). Of note, this approach allowed for comparison of the magnitude of the impact of each MBS on liver repopulation, regardless of whether the MBS enhances or inhibits regeneration (Supplementary Figure 5C). We then examined the log2 fold-change distributions of the strongest MBSs with positive (enriched) or negative (depleted) phenotypes and found these distributions to be significantly different than the population of TuDs not containing the MBS of interest (P<.001 for each) (Figure 3C).

We then compared our strength metric with the Bradley-Terry model of pairwise comparisons.23 For each pairwise TuD (i.e. having two different MBSs) we assigned a ‘win’ or ‘loss’ to each constituent MBS based on MBS phenotypes and the TuD log2 fold-change (Supplementary Figure 6A), which were then used to derive model coefficients for each MBS. In line with our strength metric, the Bradley-Terry model classified the miR-374b-5p MBS as the most potent regulator of repopulation, and Bradley-Terry model coefficients were significantly correlated with strength scores (Supplementary Figure 6B–D). Altogether, these analyses classified a subset of MBSs as modifiers of hepatocyte replication, implicating specific miRNAs in the post-transcriptional regulation of liver repopulation.

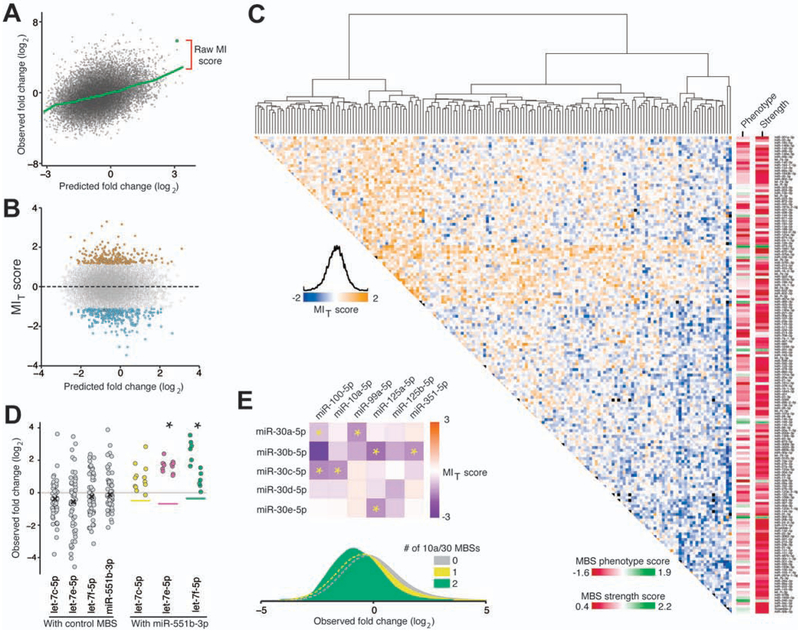

Epistatic effects of pairwise microRNA inhibition during liver repopulation

Our screening platform was also designed to identify pairwise miRNA interactions, as the binding of multiple RISCs to a transcript can elicit cooperative repression to an extent greater than the sum of the individual complexes.24 To uncover epistatic effects, we derived a miRNA-interaction (MI) score for each TuD based on a previously described model of combinatorial effects (Figure 4A).25 Raw MI scores were converted to modified t-value scores (MIT scores)26 using replicate raw MI scores of each MBS pairing in either orientation (i.e. 5’-A,B-3’ and 5’-B,A-3’). We defined TuDs with MIT scores two standard deviations from the population mean (639 MBS pairings, 4.5%) as displaying significant miRNA interactions (Figure 4B). We next derived a miRNA interaction map by hierarchical clustering of MIT scores (Figure 4C). Overlay of MBS phenotypes or strength scores suggested that clustering on the MIT map was not driven by individual miRNA effects.

Figure 4.

Epistatic miRNA interactions uncovered by pairwise TuD screens. (A) Raw miRNA interaction (MI) scores were calculated as the residuals from a LOWESS fit line (green) of the observed versus predicted log2 fold change plot. (B) Scatterplot of modified t-scores of raw MI data (MIT score) and predicted log2 fold changes. MIT scores at least two standard deviations from the population mean were considered significant interactions. (C) Hierarchical clusters and heatmap of MIT scores for all TuDs. Individual MBS phenotypes and strength scores are shown in columns beside the MIT map. (D) The observed fold changes for TuDs containing a control MBS paired with an MBS targeting members of the let-7 family or miR-551b-5p. Each data point represents a single mouse replicate. The predicted fold changes for pairwise combinations are indicated by colored lines. Data points for each pairwise TuD (colored) are separated horizontally by orientation (AB, left; BA, right). Asterisks indicate significant interactions by MIT score. (E) Top panel, heatmap of MIT scores of TuDs targeting the miR-10 and miR-30 families. Asterisks indicate significant interaction by MIT scores. Bottom panel, fold change density plots TuDs containing the indicated number of miR-10 and miR-30 MBSs.

Genetic interaction maps, such as our MIT map, are useful for generating hypotheses.25,27 The highest MIT score was observed for the TuD containing let-7e-5p and miR-551b-3p MBSs. Both of these MBSs had phenotypes below zero, suggesting that let-7e-5p or miR-551b-3p inhibition alone does not enhance liver repopulation. However, co-repression of these miRNAs resulted in consistent enrichment following repopulation (Figure 4D). Strikingly, all TuDs pairing a miR-551b-3p MBS with an MBS targeting let-7c-5p, let-7e-5p, or let-7f-5p had fold-change values greater than expected (Figure 4D). These MBSs did not tightly cluster on our fold change map and are not predicted to target the same signaling pathways (Supplementary Figure 7A), suggesting independent functions due to largely disjoint target mRNA sets.

We also noted that seven of 30 TuDs (23%) targeting both the miR-30 family and the miR-10 family had significant MIT scores below zero (Figure 4E). The population of TuDs containing two MBSs targeting the miR-30 and/or miR-10 family had significantly lower fold-change values compared to TuDs containing one such MBS or none (Figure 4E). Putative target transcripts of these miRNA families showed significant overlap in numerous KEGG pathways (Supplementary Figure S7B). The RAR-related orphan receptor alpha (Rora) transcript may account for the observed miRNA interaction, as AGO2 footprints on the Rora transcript overlap with miR-30 and miR-10 family recognition sequences.3

MicroRNA-374b inhibition in hepatocytes accelerates liver repopulation

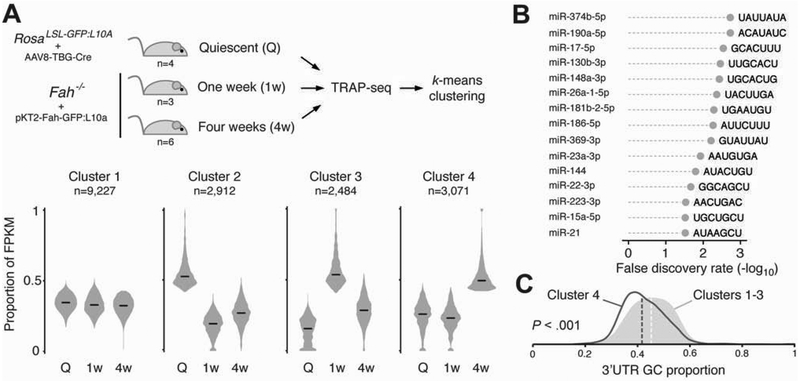

To examine transcripts induced in FAH-positive repopulating hepatocytes for putative miRNA binding sites, we utilized our previously published TRAP-Seq data set of translating mRNAs isolated specifically from repopulating hepatocytes of the Fah−/− mouse.2 Transcripts were assigned to one of four clusters using k-means clustering based on temporal changes in expression level (Figure 5A). The 3’UTRs of transcripts of cluster four (n=3,071), which displayed elevated expression at four weeks after the initiation of liver injury, were significantly enriched for the seed recognition sequences of several miRNAs identified in our screen as strong regulators of repopulation (Figure 5B). Remarkably, the two most significantly enriched seeds were those of miR-374b-5p and miR-190a-5p, targets of the two MBSs with the highest strength scores. As a group, the miRNAs with enriched seed abundance in cluster four showed a high proportion of A and U nucleotides (65.7%) within the seed sequence. Interestingly, the mRNAs of cluster four had significantly higher A/U-content compared to transcripts of the remaining three clusters (Supplementary Figure 8A); this was also true when restricted to 3’UTR sequences (Figure 5C). Repopulating hepatocytes may therefore upregulate a subset of miRNAs to coincide with this shift in the protein-coding transcriptome.

Figure 5.

Putative miRNA regulation of the dynamic transcriptome of repopulating hepatocytes. (A) Transcripts from the Wang et al. data set were clustered by k-means partitioning into four groups. Black bars indicate group medians. (B) The 3’UTRs of cluster 4 mRNAs were significantly enriched for seed recognition sequences of several miRNAs identified as strong regulators of liver repopulation. (C) Density plots of 3’UTR GC content. Dashed vertical lines indicate population medians. Cluster 4 transcripts have significantly reduced GC content compared to clusters 1–3.

Our previously published report of AGO2-bound miRNAs found that liver miR-374b-5p levels increase significantly following partial hepatectomy (Supplementary Figure 8B).3 We also noted that the promoter of the miR-374b host gene, Ftx, exhibited increased chromatin accessibility following the induction of liver repopulation in Fah−/− mice (Supplementary Figure 8C). Taken together, these results suggested that miR-374b-5p targets genes important for liver repopulation following hepatotoxic injury.

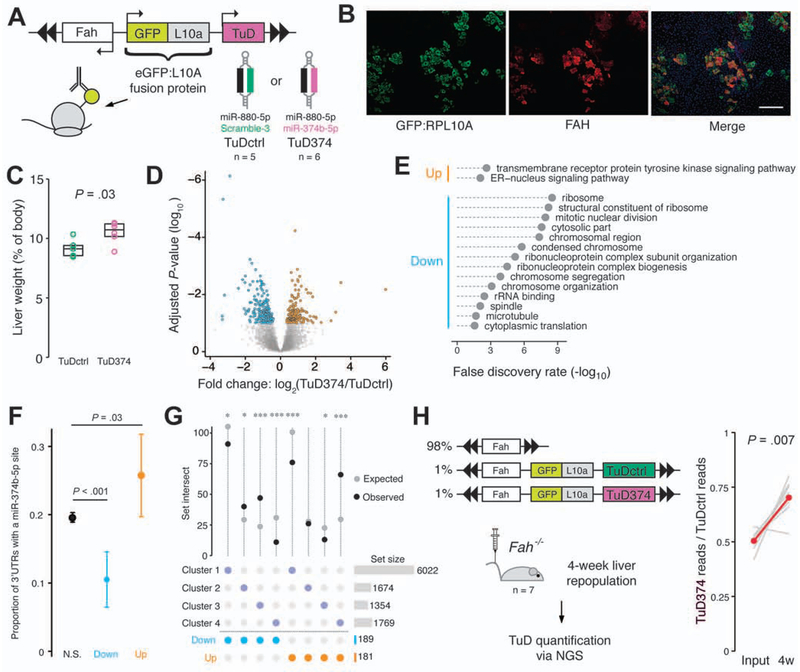

To test this hypothesis, we developed plasmids that facilitate TRAP-Seq analysis in the presence of specific miRNA inhibition (Figure 6A). Each plasmid encoded a fusion protein consisting of the ribosomal protein RPL10A and enhanced GFP, along with a TuD targeting miR-374b-5p (‘TuD374’) or control miRNAs (‘TuDctrl’). TRAP plasmids were administered to male Fah−/− mice (TuDctrl, n=5; TuD374, n=6) and liver repopulation was induced two weeks prior to tissue collection. Immunofluorescent imaging confirmed the co-expression of FAH and the GFP:RPL10A fusion protein in repopulating hepatocytes (Figure 6B). The liver to body weight ratio at sacrifice was significantly higher in animals treated with TuD374 compared to TuDctrl, despite similar overall body weights between groups (Figure 6C and Supplementary Figure 9A).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of miR-374b accelerates liver repopulation. (A) Profiling the miR-374b-5p target transcriptome using TRAP-Seq. Fah plasmids co-expressing an RPL10A:GFP fusion protein and a TuD targeting miR-374b-5p or control miRNAs were delivered to Fah−/− mice. Translating ribosomes were isolated after two weeks of repopulation and ribosome-bound mRNAs were quantified by sequencing. (B) Immunofluorescent staining of liver sections confirming co-expression of RPL10A:GFP (green) and FAH (red). DAPI, blue; scale bar, 200 μm. (C) Liver weight as a percentage of body weight. Box overlays indicate the sample median and interquartile range. (D) Differential ribosomal occupancy between groups as determined by DESeq2. (E) Gene ontology overrepresentation analysis of the differentially expressed transcript sets. (F) Proportion of 3’UTRs containing a miR-374b-5p seed recognition site. Data are presented as mean ± 95% CI. (G) Upset plot of the intersect between differentially expressed genes of the TuD TRAP-Seq experiment and the gene clusters of Figure 5A. TuD374 livers were enriched for transcripts elevated at 4-weeks (cluster 4) and depleted for transcripts elevated at week 1 (cluster 3). *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. (H) Left panel, experiment schematic. Right panel, proportional sequencing reads of TuD374 to TuDctrl in the plasmid input and livers following four weeks of liver repopulation. Individual replicates are shown in gray. Red data points indicate group means.

To assess changes in the hepatocyte transcriptome induced by miR-374b-5p inhibition, we isolated ribosome-bound mRNA from TuD374 and TuDctrl livers via affinity purification and performed RNA-Seq. Differential expression analysis identified 421 genes as significantly altered (FDR<10%; Figure 6D). Among differentially expressed genes, we noted a striking decrease in transcripts of ribosomal proteins (Supplementary Figure 9B) and cell cycle regulators in TuD374 animals. Indeed, gene ontology (GO) analysis found that the set of genes significantly reduced by miR-374b-5p inhibition was enriched for many GO terms associated with cell proliferation and the cytosolic ribosome (Figure 6E). Strikingly, each altered ribosomal gene showed a decrease in expression over time in our previous TRAP-Seq time course (Supplementary Figure 9C). In addition, several genes highly expressed in fetal liver cells, including Igf2 and Afp, were significantly reduced in TuD374 livers (Supplementary Figure 9D).

Transcripts increased in TuD374-expressing hepatocytes were significantly more likely to contain a miR-374b-5p seed sequence in the 3’ UTR compared to unaffected mRNAs (Figure 6F). However, the majority of elevated mRNAs did not contain a miR-374b-5p seed recognition site, and we sought to identify indirect mechanisms to account for the observed expression changes. We used iRegulon28 to identify transcription factor binding motifs enriched within a 20 kb window centered on the transcriptional start sites of genes in the altered sets. The motif with the highest Normalized Enrichment Score (NES) among upregulated genes is bound by forkhead box (FOX) transcription factors, suggesting TuD374-expressing hepatocytes had regained normal metabolic functions following two weeks of repopulation (Supplementary Figure 9E). Among the most downregulated transcripts in TuD374 hepatocytes was the mRNA encoding Y box protein 1 (YBX1), a transcription factor that interacts with the Y/CCAAT box. This motif, also bound by the nuclear transcription factor Y (NFY) complex, was the most enriched binding motif of the downregulated genes (Supplementary Figure 9E).

Next, we compared the sets of significantly altered transcripts to the k-means clusters we derived from the repopulation time-course TRAP-Seq data. We found a 2.3-fold overrepresentation of genes elevated in TuD374 livers within TRAP-Seq cluster four, which consists of genes increased after four weeks of repopulation, and a 1.7-fold underrepresentation within cluster three, which showed elevation at the one-week time point (Figure 6G). Conversely, genes reduced in TuD374 livers were underrepresented 2.8-fold in cluster four and 2-fold overrepresented in cluster three. These results, in addition to the observed increase in liver size and a less proliferative expression profile, suggested TuD374 hepatocytes had more rapidly executed their repopulation program. To test this notion, we performed a competitive repopulation experiment by injecting female Fah−/− mice (n=7) with a pool of TuDctrl and TuD374 plasmids together with a plasmid expressing Fah alone. After four weeks of repopulation, we observed a significant increase in the relative proportion of TuD374 in liver tissues compared to the input plasmid pools, confirming accelerated repopulation by hepatocytes upon miR-374b-5p inhibition (Figure 6H and Supplementary Table 5).

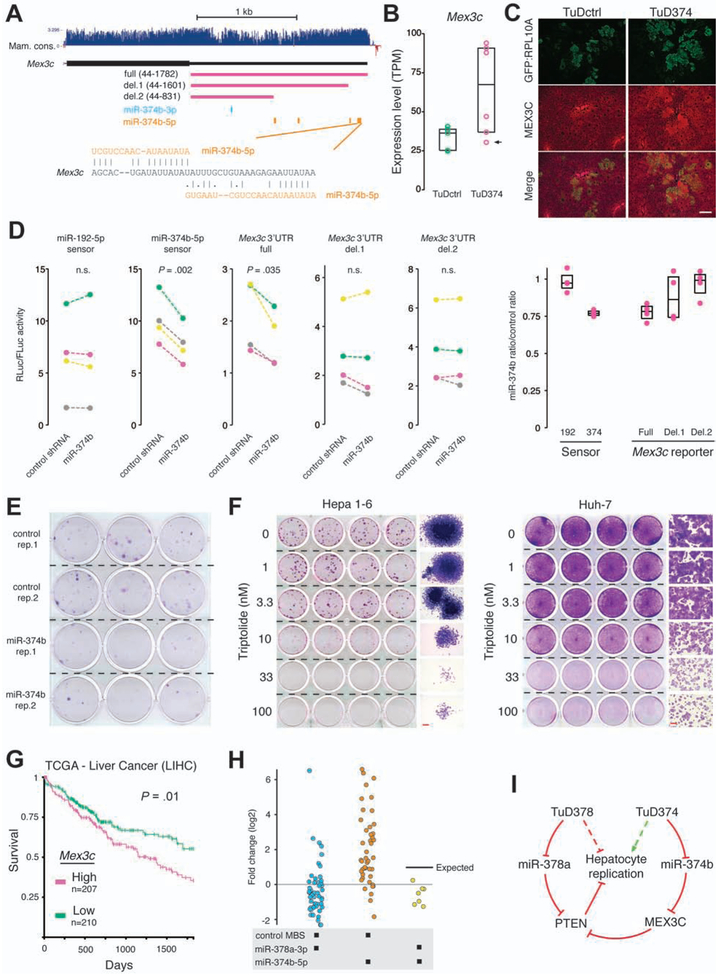

MicroRNA-374b regulates liver cell replication by targeting Mex3c

We next sought to identify potential miR-374b-5p targets that could partially explain our in vivo observations. Using in silico prediction tools, we found the Mex3c mRNA to be a likely miR-374b-5p target (Figure 7A). Mex3c encodes an RNA-binding protein with E3 ligase activity recently shown to inhibit the phosphoinositol phosphatase activity of PTEN by directly facilitating lysine 27 polyubiquitination (PTENK27-polyUb).29,30 Because PTEN functions downstream of receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling (enriched in TuD374 animals, Fig. 6E) and negatively regulates liver regeneration, we postulate that elevated Mex3c expression enhances hepatocyte replication by inhibiting PTEN.31

Figure 7.

MiR-374b-5p targets Mex3c in liver cells. (A) Genome browser tracks showing exon 2 of the mouse Mex3c gene and predicted miRNA binding sites. (B) Mex3c expression as determined by TRAP-Seq in Fah−/− mouse livers following two weeks of repopulation transfected with either control or miR-374 targeting TuDs encoded on the Fah cDNA plasmid. Arrow indicates the TuD374 replicate displayed in panel C. (C) GFP:RPL10A and MEX3C protein in liver sections of Fah−/− mice following two weeks of repopulation. Scale bar, 50 mm. (D) Dual luciferase assays performed in Hepa 1–6 cells. Mex3c 3’UTR sequences used in reporter constructs are shown in panel A. Left panel, RLuc/FLuc ratios. Right panel, miR-374b transfected cell ratios relative to control transfected cells. (E) One-week clonogenic assay of Hepa 1–6 cells expressing control shRNA or mmu-miR-374b. (F) Mouse hepatoma Hepa 1–6 cells and human HCC-derived Huh-7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of triptolide for one week and then stained with crystal violet. Side panels are representative magnifications. Scale bars, 200 mm. (G) Five-year survival probability of HCC patients (TCGA) grouped by Mex3c mRNA levels. (H) Observed fold changes for TuDs containing the indicated MBS pairings. Each data point represents a single mouse replicate. The expected fold-change for the miR-378a-3p + miR-374b-5p TuD is indicated. (I) A model for miR-374b-5p/Mex3c regulation of liver repopulation. Dashed lines indicate proposed net effects on liver repopulation.

To modulate miR-374b-5p levels in vitro, we derived a plasmid expressing the mouse miR-374b hairpin. Dual luciferase assays confirmed elevated miR-374b-5p activity in Hepa 1–6 cells after miR-374b hairpin transfection (Figure 7D). Using Mex3c 3’UTR reporters, we found that miR-374b significantly repressed the full length 3’UTR, whereas truncations that removed some or all predicted miR-374b-5p sites showed a loss of repression, confirming Mex3c as a direct target of miR-374b-5p (Figure 7D). Furthermore, cells expressing miR-374b displayed reduced clonogenicity compared to controls, in agreement with our TuD374 experiments, (Figure 7E).

To determine if MEX3C can affect liver cell replication, we treated cells with triptolide, a compound that directly binds the RING domain of MEX3C and prevents its association with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2S, thereby inhibiting the formation of PTENK27-polyUb.29 Triptolide treatment of mouse Hepa 1–6 or human Huh-7 cells decreased growth in a dose-dependent manner at low nanomolar concentrations (Figure 7F). Finally, we queried the human liver cancer dataset of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for MEX3C expression and found that patients with elevated MEX3C levels have reduced 5-year survival (Figure 7G).

One of the lowest MIT scores for TuDs containing the miR-374b-5p MBS was the miR-378a-3p MBS pairing (Figure 7H). As miR-378a-3p was previously shown to target the Pten, we speculate that de-repression of Pten upon miR-378a-3p inhibition is sufficient to negate the pro-replicative effects of the miR-374b-5p MBS and that miR-374–5p functions primarily upstream of AKT signaling in repopulating hepatocytes, as modeled in Figure 7I.32

DISCUSSION

Although screening pairwise combinations of all protein-coding transcripts in mammalian cells is currently unfeasible, massive pairwise genetic screens employing shRNA, siRNA, miRNA, or CRISPR expression systems have now been conducted in vitro.25,27,33–36 Given that a mammalian cell type expresses just a subset of the ~1,000 miRNAs encoded in its genome, screens encompassing all pairwise combinations of miRNAs active in a given cell type are now practical. Here we demonstrate a novel approach to screen miRNA function in a pairwise and high-throughput manner in vivo.

The continued delivery of miRNA modulators to the liver in an efficacious manner over a repopulation time course is cost-prohibitive. Our sequential ligation approach makes the derivation of large TuD pools cost-effective compared to the synthesis of full-length inhibitors, as the stem and loop sequences shared by all TuDs are incorporated within the plasmid backbone prior to inhibitor assembly. By tailoring our TuD plasmids for use in Fah−/− mouse model, we have screened inhibitors in vivo at a much larger scale than would otherwise be possible. Furthermore, our pairwise TuD design ensured that a given MBS was present in numerous, uniquely identifiable inhibitors in each library, with up to 353 measurement for each MBS, enabling accurate quantification of effects on repopulation.

The detection of miRNA regulation is often confounded by mild to moderate effect sizes and redundant targeting by multiple miRNAs upon individual transcripts further complicates the elucidation of their function. High-order systematic miRNA screens afford the opportunity to discover interactions that would otherwise go undetected.35 The results of our pairwise inhibition screens will enable the design of higher-order miRNA investigations, for which the mouse liver would otherwise be insufficient due to scalability. Exploration of the interaction map generated here may also inform novel combinatorial therapeutic strategies to address aberrant liver cell proliferation. The miRNA inhibition system we developed can be easily adapted to study other conditions for which the Fah−/− model has been utilized, including hepatocellular carcinoma.16 To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic functional test of a mammalian tissue’s miRNAome.

Supplementary Material

Grant support:

This work was supported by the following awards from the NIH: R01 DK102667 (K.H.K.), K01 DK102868 (A.M.Z.), K08 DK106478 (K.J.W.), and F31 DK113666 (A.W.W.). We thank the University of Pennsylvania Diabetes Research Center for the use of the Functional Genomics Core (P30 DK19525) and the Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases (P30 DK050306) for the use of the Molecular Pathology and Imaging Core. We also thank Long Gao for bioinformatics support.

Abbreviations:

- AGO2

Argonaute 2

- FAH

fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase

- FLuc

firefly luciferase

- FOX

forkhead box

- HTI

hereditary tyrosinemia type I

- MBS

microRNA-binding site

- miRNA

microRNA

- NES

Normalized Enrichment Score

- NFY

nuclear transcription factor Y

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RLuc

Renilla luciferase

- TuD

tough decoy

- YBX1

Y box protein 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All work performed in the Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Disclosures: The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Transcript Profiling: Pending.

Contributor Information

Yue J. Wang, Florida State University;.

Jonathan Schug, PSOM Next-Generation Sequencing Core, University of Pennsylvania;.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michalopoulos GK, DeFrances MC. Liver regeneration. Science 1997;276:60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang AW, Wangensteen KJ, Wang YJ, et al. TRAP-seq identifies cystine/glutamate antiporter as a driver of recovery from liver injury. J Clin Invest 2018;128:2297–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schug J, McKenna LB, Walton G, et al. Dynamic recruitment of microRNAs to their mRNA targets in the regenerating liver. BMC Genomics 2013;14:26–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018;173:20–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hand NJ, Master ZR, Le Lay J, Friedman JR. Hepatic function is preserved in the absence of mature microRNAs. Hepatology 2009;49:618–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekine S, Ogawa R, Ito R, et al. Disruption of Dicer1 induces dysregulated fetal gene expression and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2009;136:230–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekine S, Ogawa R, Mcmanus MT, Kanai Y, Hebrok M. Dicer is required for proper liver zonation. J Pathol 2009;219:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song G, Sharma AD, Roll GR, et al. MicroRNAs control hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration. Hepatology 2010;51:1735–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bak RO, Hollensen AK, Primo MN, Sorensen CD, Mikkelsen JG. Potent microRNA suppression by RNA Pol II-transcribed ‘Tough Decoy’ inhibitors. RNA 2013;19:280–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haraguchi T, Ozaki Y, Iba H. Vectors expressing efficient RNA decoys achieve the long-term suppression of specific microRNA activity in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollensen AK, Bak RO, Haslund D, Mikkelsen JG. Suppression of microRNAs by dual-targeting and clustered Tough Decoy inhibitors. RNA Biol 2013;10:406–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie J, Ameres SL, Friedline R, et al. Long-term, efficient inhibition of microRNA function in mice using rAAV vectors. Nat Methods 2012;9:403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grompe M, al-Dhalimy M, Finegold M, et al. Loss of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase is responsible for the neonatal hepatic dysfunction phenotype of lethal albino mice. Genes Dev 1993;7:2298–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wangensteen KJ, Wilber A, Keng VW, et al. A facile method for somatic, lifelong manipulation of multiple genes in the mouse liver. Hepatology 2008;47:1714–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wangensteen KJ, Zhang S, Greenbaum LE, Kaestner KH. A genetic screen reveals Foxa3 and TNFR1 as key regulators of liver repopulation. Genes Dev 2015;29:904–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wangensteen KJ, Wang YJ, Dou Z, et al. Combinatorial genetics in liver repopulation and carcinogenesis with a in vivo CRISPR activation platform. Hepatology 2018;68:663–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuestefeld T, Pesic M, Rudalska R, et al. A Direct in vivo RNAi screen identifies MKK4 as a key regulator of liver regeneration. Cell 2013;153:389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiman M, Kulicke R, Fenster RJ, Greengard P, Heintz N. Cell type-specific mRNA purification by translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP). Nat Protoc 2014;9:1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang AW, Zahm AM, Wangensteen KJ Cell Type-specific Gene Expression Profiling in the Mouse Liver. J. Vis. Exp 2019;151:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 2010;11:R10–r106. Epub 2010 Oct 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature 2006;441:537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Z, Herrera-Carrillo E, Berkhout B. Delineation of the Exact Transcription Termination Signal for Type 3 Polymerase III. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2018;10:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley RA, Terry ME. Rank Analysis of Incomplete Block Designs: I. The Method of Paired Comparisons. Biometrics 1952;39:324–345. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doench JG, Petersen CP, Sharp PA. siRNAs can function as miRNAs. Genes Dev 2003;17:438–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassik MC, Kampmann M, Lebbink RJ, et al. A systematic mammalian genetic interaction map reveals pathways underlying ricin susceptibility. Cell 2013;152:909–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Krogan NJ, Weissman JS. A strategy for extracting and analyzing large-scale quantitative epistatic interaction data. Genome Biol 2006;7:R6–r63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horlbeck MA, Xu A, Wang M, et al. Mapping the Genetic Landscape of Human Cells. Cell 2018;174:95–967.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janky R, Verfaillie A, Imrichova H, et al. iRegulon: from a gene list to a gene regulatory network using large motif and track collections. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Hu Q, Li C, et al. PTEN-induced partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition drives diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 2019;129:1129–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Q, Li C, Wang S, Li Y, et al. LncRNAs-directed PTEN enzymatic switch governs epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cell Res 2019;29:286–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kachaylo E, Tschuor C, Calo N, et al. PTEN Down-Regulation Promotes beta-Oxidation to Fuel Hypertrophic Liver Growth After Hepatectomy in Mice. Hepatology 2017;66:908–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Zuo X, Yang B, et al. MicroRNA directly enhances mitochondrial translation during muscle differentiation. Cell 2014;158:607–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roguev A, Talbot D, Negri GL, et al. Quantitative genetic-interaction mapping in mammalian cells. Nat Methods 2013;10:432–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laufer C, Fischer B, Billmann M, Huber W, Boutros M. Mapping genetic interactions in human cancer cells with RNAi and multiparametric phenotyping. Nat Methods 2013;10:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong AS, Choi GC, Cheng AA, Purcell O, Lu TK. Massively parallel high-order combinatorial genetics in human cells. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:952–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han K, Jeng EE, Hess GT, Morgens DW, Li A, Bassik MC. Synergistic drug combinations for cancer identified in a CRISPR screen for pairwise genetic interactions. Nat Biotechnol 2017;35:463–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyamichi K, Amat F, Moussavi F, et al. Cortical representations of olfactory input by trans-synaptic tracing. Nature 2011;472:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hand NJ, Horner AM, Master ZR, et al. MicroRNA profiling identifies miR-29 as a regulator of disease-associated pathways in experimental biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gagnon-Bartsch JA, Jacob L, Speed TP. Removing unwanted variation from high dimensional data with negative controls. Berkeley: Tech Reports from Dep Stat Univ California; 2013;1–112. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newson R QQVALUE: Stata module to generate quasi-q-values by inverting multiple-test procedures. 2013;. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the royal statistical society.Series B (Methodological) 1995;289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner H, Firth D. Bradley-Terry models in R: the BradleyTerry2 package. Journal of Statistical Software 2012;48:. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Vasaikar S, Shi Z, Greer M, Zhang B. WebGestalt 2017: a more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:W13–W137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marco A SeedVicious: Analysis of microRNA target and near-target sites. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vlachos IS, Zagganas K, Paraskevopoulou MD, et al. DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paraskevopoulou MD, Georgakilas G, Kostoulas N, et al. DIANA-microT web server v5.0: service integration into miRNA functional analysis workflows. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krzywinski M, Birol I, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Hive plots--rational approach to visualizing networks. Brief Bioinform 2012;13:627–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warnes GR, Bolker B, Bonebakker L, et al. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. R package version 2009;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pavlidis P, Noble WS. Matrix2png: a utility for visualizing matrix data. Bioinformatics 2003;19:295–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lai D, Proctor JR, Zhu JY, Meyer IM. R-CHIE: a web server and R package for visualizing RNA secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.