ABSTRACT

Background

Evaluation of one’s own body highly depends on psychopathology. In contrast to healthy women, body evaluation is negative in women from several diagnostic groups. Particularly negative ratings have been reported in disorders related to childhood sexual abuse (CSA) including borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, it is unknown whether this negative evaluation persists beyond symptomatic remission, whether it depends on the topography of body areas (sexually connoted versus neutral areas), and whether it depends on CSA.

Objective

First, we aimed at a quantitative comparison of body evaluation across three diagnostic groups: current BPD (cBPD), remitted BPD (rBPD), and healthy controls (HC). Second, we aimed at clarifying the potentially moderating role of a history of CSA and of the sexual connotation of body areas.

Methods

The study included 68 women from the diagnostic groups of interest (cBPD, rBPD, and HC). These diagnoses were established with the International Personality Disorder Examination. The participants used the Survey of Body Areas to quantify the evaluation of the own body and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire for assessing CSA.

Results

While the evaluation of the own body was generally negative in women from the cBPD group it was positive in those who had remitted from BPD. However, their positive scores were strictly confined to neutral body areas, whereas the evaluation of sexually connoted body areas was negative, resembling the respective evaluation in cBPD patients and contrasting the positive evaluation of sexually connoted areas in healthy women. The negative evaluation of sexually connoted areas in remitted women was significantly related to a history of CSA.

Conclusions

Women with BPD may require a specifically designed intervention to achieve a positive evaluation of their entire body. The evaluation of sexually connoted body areas seems to remain an issue even after remission from the disorder has been achieved.

KEYWORDS: Adverse childhood experiences, body image, borderline personality disorder, childhood sexual abuse, remission, trauma

HIGHLIGHTS: • Women with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) showed a negative evaluation of the own body. • In contrast, women who have remitted from BPD showed a generally positive body evaluation. • However, their positive evaluations were strictly confined to areas without sexual connotation; sexually connoted body areas were rated as highly negative. • The negative evaluation of sexually connoted body areas in women who had remitted from BPD was moderated by childhood sexual abuse.

Antecedentes: La evaluación del cuerpo propio depende en gran parte de la psicopatología. En contraste con mujeres sanas, la evaluación del cuerpo es negativa en mujeres de diferentes grupos diagnósticos. Evaluaciones particularmente negativas han sido reportadas en trastornos relacionados al abuso sexual infantil (CSA por sus siglas en inglés), incluyendo el trastorno de personalidad límite (BPD por sus siglas en inglés). Sin embargo, no se conoce si esta evaluación negativa persiste al alcanzar la remisión sintomática, si es que depende de la topografía de las áreas del cuerpo (áreas con connotación sexual versus neutras), y si depende del antecedente de CSA.

Objetivo: Primero, dirigimos una comparación cuantitativa de la evaluación corporal en tres grupos diagnósticos: BPD actual (cBPD), BPD en remisión (rBPD) y controles sanos (HC por sus siglas en inglés). En segundo lugar, intentamos clarificar el potencial rol moderador de una historia de CSA y de la connotación sexual de las áreas corporales.

Métodos: El estudio incluyó 68 mujeres de los grupos diagnósticos de interés (cBPD, rBPD y HC). Estos diagnósticos fueron establecidos con el Examen Internacional de Trastornos de Personalidad. Las participantes completaron la Encuesta de Áreas Corporales para cuantificar la evaluación del cuerpo propio y el Cuestionario de Trauma Infantil para evaluar CSA.

Resultados: Mientras la evaluación del cuerpo propio fue generalmente negativa en mujeres del grupo cBPD, fue positiva en aquellas con BPD en remisión. Sin embargo, sus puntajes positivos fueron estrictamente circunscritos a las áreas del cuerpo neutrales, mientras que la evaluación de las áreas del cuerpo con connotación sexual fue negativa, y símiles a la evaluación de las pacientes del grupo cBPD, y contrastando con la evaluación positiva de las áreas con connotación sexual de las mujeres sanas. La evaluación negativa de áreas del cuerpo con connotación sexual en las mujeres en remisión fue relacionada significativamente con una historia de CSA.

Conclusiones: Las mujeres con BPD pueden requerir una intervención específicamente diseñada para alcanzar una evaluación positiva de su cuerpo completo. La evaluación de áreas del cuerpo con connotación sexual parece permanecer problemática incuso posterior a que la remisión del trastorno ha sido alcanzada.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Experiencias adversas tempranas, imagen corporal, trastorno de la personalidad límite, abuso sexual infantil, remisión, trauma

背景: 对自己身体的评估在很大程度上取决于精神病理学。与健康女性相反, 来自一些诊断组的女性的身体评估为负性。与童年期性虐待 (CSA) 有关的疾病中, 包括边缘性人格障碍 (BPD), 尤其报告了负性评分。但是, 尚不清楚这种负性评估是否会持续到症状缓解后, 是否取决于身体部位分布 (性暗示区还是中性区), 以及是否取决于CSA。

目的: 首先, 我们旨在对三个诊断组的身体评估进行定量比较:当前BPD组 (cBPD), 缓解BPD组 (rBPD) 和健康对照组 (HC) 。其次, 我们旨在阐明CSA历史和身体性暗示部位的潜在调节作用。

方法: 本研究纳入了68名诊断组 (cBPD, rBPD和HC) 的女性。这些诊断由国际人格障碍检查确定。参与者使用身体部位调查量表来量化对自己身体的评估, 并使用儿童期创伤问卷来评估CSA。

结果: cBPD组的女性对自己身体的评价总体为负性, 而缓解BPD组女性的评估为正性。然而其正性得分严格限于中性身体部位, 而对有性暗示的身体部位的评估则为负性, 这类似于cBPD患者的分别评估, 相反于健康女性对性暗示部位的正性评估。缓解组女性对性暗示部位的负性评估与CSA的病史密切相关。

结论: 患有BPD的女性可能需要专门设计的干预措施才能对整个身体进行正性评估。即使在疾病缓解后, 对有性暗示的身体部位的评估似乎仍然是一个问题。

关键词: 不良童年经历, 身体形象, 边缘性人格障碍, 童年期性虐待, 缓解, 创伤

1. Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a frequent consequence of childhood sexual abuse (CSA, de Aquino Ferreira, Pereira, Benevides, & Melo, 2018). BPD is characterized by affective instability, an unstable sense of self, unstable trust, and hypersensitivity to interpersonal rejection (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Bortolla, Cavicchioli, Galli, Verschure, & Maffei, 2019; Glenn & Klonsky, 2009; Houben, Claes, Sleuwaegen, Berens, & Vansteelandt, 2018; Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan, & Bohus, 2004; Linehan, 1993; Miano, Fertuck, Roepke, & Dziobek, 2017; Schmahl et al., 2014). All of these characteristics are associated with a negative evaluation of the own body, both in healthy and clinical samples (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2002; Crocker & Wolfe, 2001; Thompson, Heinberg, & Altabe, 1999). Accordingly, the evaluation of one’s own body, which in turn is a well-established factor for well-being (Swami, Weis, Barron, & Furnham, 2018), represents an important issue when studying the phenomenology and treatment of BPD. However, systematic research with a focus on body evaluation in subjects with BPD is scant – despite the newly established trend towards more holistic approaches in establishing phenomenology, defining recovery, and assessing treatment success in personality disorders (Ng, Townsend, Miller, Jewell, & Grenyer, 2019).

The few pioneering studies on evaluation of the own body in BPD have demonstrated that most patients with a BPD diagnosis evaluate their body as highly negative (Dyer, Hennrich, Borgmann, White, & Alpers, 2013; Haaf, Pohl, Deusinger, & Bohus, 2001; Kazuko & Inoue, 2009; Kleindienst et al., 2014). The negative evaluation of the own body in the BPD group clearly contrasts with the generally positive body evaluation in healthy control participants (Kleindienst et al., 2014). However, findings were mixed with respect to the clinical specificity of negative body evaluation: While body evaluation was found to be neutral in clinical control participants with a diagnosis of anxiety disorders including social phobia and panic disorder, it was negative in women with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after CSA (Kleindienst et al., 2014). Negative self-ratings in the domains of ‘acceptance of body’ and ‘attractivity to others’ were further reported for women with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa (Haaf et al., 2001). However, in those studies that compared body evaluation across different diagnostic groups (Haaf et al., 2001; Kleindienst et al., 2014), the most negative mean ratings were observed in participants with a diagnosis of BPD.

Besides increasing the risk for developing BPD, CSA is known to have further pervasive long-term consequences on self-esteem, identity, and sexuality, both in adolescence and adulthood (Fergusson, McLeod, & Horwood, 2013; Herman, Perry, & Van der Kolk, 1989; Irish, Kobayashi, & Delahanty, 2010). Furthermore, CSA is thought to counteract the development of a positive evaluation of the own body. A coherent and positive body image develops in an interpersonal process involving positive feedback from caregivers and peers (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2002; Sack, Boroske-Leiner, & Lahmann, 2010; Wood-Barcalow, Tylka, & Augustus-Horvath, 2010). Accordingly, severe violations of body boundaries such as sexual abuse may have particularly negative and enduring consequences for the development of one’s body image (Weiner & Thompson, 1997). Following these general observations and theoretical considerations, CSA has been investigated as a potential negative predictor of body evaluation in BPD. However, the empirical results are mixed – while some studies support that CSA is an aggravating factor for the negative evaluation of the own body (Dyer et al., 2013), others do not (Kleindienst et al., 2014). Given the paucity of empirical investigations and given the heterogeneity of the findings, further research is required to clarify to which extent a history of CSA is related to a more negative evaluation of the own body in BPD patients. In addition, it is largely unknown whether a negative body evaluation in BPD patients typically affects all body areas, or whether it is pronounced for those areas that are typically affected by severe CSA, i.e. sexually connoted body areas. In female population-based samples, there is a large variance in the evaluation of one’s own sexually connoted body areas (Ålgars et al., 2011), with about 50% not being satisfied with their genitals and breasts. The overall reduced body evaluation in BPD might be pronounced for these body areas, especially when a history of CSA is reported.

Besides elaborating the phenomenology of body evaluation along with its antecedents, it would be clinically relevant to know whether a negative evaluation of the own body tends to persist after symptomatic remission. Empirical observations indicate that remission is common in BPD: over a course of 16 years, 99% of BPD patients temporarily fulfilled the criteria for symptomatic remission; however, recurrence of the disorder was observed in up to 36% of the cases (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich, & Fitzmaurice, 2012), and significant impairments in social functioning (Gunderson et al., 2011), emotional regulation (Chung, Hensel, Schmidinger, Bekrater‐Bodmann, & Flor, 2020), and self-perception (Löffler, Kleindienst, Cackowski, Schmidinger, & Bekrater-Bodmann, 2020) also persist in the remitted stage. These findings indicate that remission of BPD might be rather volatile in terms of stable clinical improvement. Whether or not body evaluation is subject to normalization during the remission of the disorder remains an open question, whose answer might have important clinical implications in terms of both therapy and therapeutic aftercare.

The present study had several objectives. The first aim was to quantify the evaluation of the own body in both current BPD (cBPD) and remitted BPD (rBPD) patients and to compare them with the values obtained in a group of healthy controls (HC). Second, we aimed at clarifying the potentially moderating role of two variables on body evaluation: (i) a history of CSA and (ii) the sexual connotation of body areas. We hypothesized that body evaluation would differ across the three groups under investigation (cBPD vs rBPD vs HC) and that remitted BPD subjects show normalization of body evaluation. We further hypothesized that a history of CSA would be negatively correlated to body evaluation, especially for sexually connoted body areas. Finally, we investigated the hypothesis that the sexual connotation of body areas might moderate the supposed normalization of body evaluation in remitted BPD.

2. Methods

2.1. Diagnostic groups, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants from three diagnostic groups were included into this study: current BPD (cBPD), remitted BPD (rBPD), and healthy controls (HC). Participants from the cBPD group had to meet the diagnostic criteria of BPD according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), which also correspond to the diagnostic criteria of BPD in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Participants from the rBPD group were required to have a lifetime diagnosis of BPD, but during the 24 months preceding study participation they had to meet no more than three BPD criteria. In addition, participants were only included into the rBPD group if behaviours of non-suicidal self-injury had occurred no more than twice a year during the 24 months preceding study participation and if no crisis intervention due to BPD symptoms had occurred during the last 24 months. HC participants had to display lifetime absence of both axis I and axis II disorders.

Besides these specific criteria defining the three groups, participants had to meet general inclusion criteria, i.e. female gender, age between 18 and 50 years, fluency in German, and a body mass index ≥ 16.5. General exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of schizophrenia (lifetime), bipolar I disorder (lifetime), mental retardation, serious physical illness, severe brain diseases, concussion, pregnancy, substance dependence disorder within the last year or substance abuse during the last two months, and current psychotropic medication (with the exception of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

2.2. Recruitment

The study was carried out within a consortium on mechanisms underlying emotion dysregulation in BPD, the KFO-256 (Schmahl et al., 2014). Participants were recruited through the central recruitment unit of the KFO-256. Psychometric data were monitored and stored at a central database. Accordingly, samples across KFO-256 studies may show overlap in participants. Individuals with a current or previous diagnosis of BPD (cBPD and rBPD) have been recruited from various sources including the pool of inpatients and outpatients at the Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim, and of the Department of General Psychiatry at the University of Heidelberg, as well as online announcements and flyers. Female HC participants were recruited through the local resident’s registration office.

All participants provided their written informed consent prior to study participation. The study was approved by the ethics board of the Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, and is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Assessments

2.3.1. Diagnostic procedure and questionnaires

The diagnostic criteria of BPD according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were assessed with the International Personality Disorder Examination (Loranger, 1999). The diagnostic interviews were conducted by specifically trained psychologists with at least a Master’s degree. Co-occurrng axis I disorders were diagnosed according to the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I; Wittchen, Zaudig, & Fydrich, 1997). Clinical assessments further included self-rating instruments for severity of borderline symptomatology (Borderline Symptom List [BSL-23]; Bohus et al., 2009) and for childhood abuse (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [CTQ]; Bernstein et al., 2003). A history of sexual abuse was assessed from the respective sub-scale of the CTQ.

2.3.2. Evaluation of the own body

The evaluation of the own body was assessed with the Survey of Body Areas (SBA, Kleindienst et al., 2014). Participants were asked to colour the front and the back of a female standardised drawing, using different coloured crayons to indicate which of their own body areas they either like or dislike. The participants were instructed as follows: “Here is a schematic drawing of a body. We would like to ask you to use this drawing for indicating which areas of your body you like and which areas you dislike. Please colour the body areas you like in green and the body areas you dislike in red. Neutral body areas may be left unmarked.” The resulting drawings were later divided into 27 predefined areas, presenting a slightly modified version of the originally published SBA. Positively rated areas were coded with +1, while negatively rated areas were coded with −1; neutral or ambiguous areas (i.e. rated both positively and negatively) were coded with 0. This allowed for the calculation of several indices, including the SBA mean score (ranging from −1 to +1) which was defined as the unweighted mean evaluation of the 27 body areas. For the purposes of the present study, the body areas were subdivided into areas that typically have a sexual connotation and into areas that are typically considered neutral at this respect. This subdivision was carried out in accordance with recommendations and empirical data previously reported (Bernard, Gervais, Allen, Campomizzi, & Klein, 2012; Bernard, Gervais, Allen, Delmée, & Klein, 2015; Gervais, Vescio, Förster, Maass, & Suitner, 2012). Sexually connoted areas included five areas (genitalia, left and right buttock areas, left and right breasts); neutral areas included 17 areas (head, neck, left and right shoulders, left and right upper and lower arms, left and right legs, left and right hands, left and right feet, upper back). Areas that could not be unambiguously assigned to either sexually connoted or sexually neutral areas (i.e. left and right thighs, belly, lower back, décolleté; Bernard et al., 2012, 2015; Gervais et al., 2012) have not been included in the analyses on sexual versus neutral areas.

Based on this classification, separate mean values for sexual and neutral areas were calculated (both ranging from −1 to +1). To investigate differences between sexual and neutral areas, we further calculated delta-scores for each individual i, with positive scores representing more positive evaluation of sexually connoted body areas:

2.4. Data analytic strategy

Mean ratings of body evaluation were analysed using both between-group comparisons and within-group comparisons. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by pair-wise Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc comparisons were used for comparing body evaluation across the three diagnostic groups (HC vs rBPD vs cBPD). Within each of these groups, one-sample t-tests were used to establish whether the average body evaluation would differ significantly from a neutral score of 0, thus indicating whether this evaluation was predominantly positive or negative in the respective group. Multivariate linear regression models controlling for the CTQ total score were used to predict evaluation of the own body from a history of CSA. Missing items from the CTQ were estimated from the individually available items based on a Stochastic Regression Imputation (SRI) approach which avoids both bias and overfitting (Enders, 2006). Overall, 9 out of 2108 items (0.43%) have been missing and were imputed. Unless reported otherwise residuals of the regression models were in line with normality, i.e. non-significant Shapiro-Wilk tests supplemented by graphical inspection. Furthermore sensitivity analyses were carried out by calculating Cook’s D (Cook, 1979) for each regression model which were checked for potentially influential cases (i.e. Cook’s D > 4/(n − k − 1), with n = number of cases and k = number of parameters in the model). Unless reported otherwise, findings of the regression analyses were essentially confirmed (i.e. significant beta-estimates remained significant and non-significant beta-estimates remained non-significant) after potentially influential cases had been removed from the respective model.

Cohen’s d (based on pooled standard deviation) was used as an estimate of between-group effect-sizes for continuous data. Unless otherwise indicated, descriptive statistics are provided as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. Pairwise comparisons of non-normal scores were carried out by Van-der-Waerden tests based on asymptotic Z-statistics. Two-tailed p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS™ v.9.4.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Overall, 69 participants met the criteria for study participation and provided their informed consent. Due to an acute physical malaise during the experimental session, one participant from the HC group had to be excluded. Thus, the final sample consisted of 68 women and included 20 HC, 22 individuals who have remitted from BPD, and 26 individuals with a current diagnosis of BPD. There were no significant differences with respect to age across the three groups (HC: 27.05 ± 7.17 years, rBPD: 29.77 ± 5.44 years, cBPD: 31.65 ± 9.09 years, F(2,65) = 2.13, p = 0.13). Similarly, the three groups did not differ with respect to their Body-Mass-Index (HC: 23.40 ± 5.32 kg/m2, rBPD: 24.04 ± 6.60 kg/m2, cBPD: 24.91 ± 5.56 kg/m2, F(2,60) = 0.74, p = 0.69).

As expected, the HC participants with no history of mental disorders had very low scores on the subscale of the CTQ for sexual abuse (5.00 ± 0.00) and on the mean-score of the BSL-23 (0.16 ± 0.25). The groups of remitted and current BPD did not differ significantly with respect to the mean scores of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) (rBPD: 6.60 ± 3.02, cBPD: 8.18 ± 4.44, Z = −1.36, p = 0.17). However, symptom severity as assessed with the BSL-23 was higher in cBPD (1.86 ± 0.53) compared to rBPD (0.50 ± 0.38; t(39) = 8.96, p < 0.001). By definition, participants from the HC group had no co-occurring axis I disorders. While none of the participants from the rBPD group currently met the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress-disorder, major depressive disorder, or eating disorders, the prevalences of these disorders in the cBPD group were 50.0%, 26.9%, and 19.2%, respectively. The percentages of participants meeting lifetime diagnoses for these disorders in the rBPD and cBPD groups, respectively, were 45.5% vs 53.9% (p = 0.56) for post-traumatic stress-disorders, 63.6% vs 76.9% (p = 0.31) for major depressive disorders, and 46.2% vs 50.0% (p = 0.75) for eating disorders.

3.2. Evaluation of body areas

3.2.1. Evaluation of body areas in general

The mean evaluation of body areas was different across the three groups (F(2,65) = 11.75, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests indicated that the differences between the groups of cBPD and HC as well as between cBPD and rBPD were large and statistically significant, while the difference between groups of rBPD and HC was small to medium and not statistically significant (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of the own body.

| Healhty Controls (HC) n = 20 |

Remitted BPD (rBPD) n = 22 |

Current BPD (cBPD) n = 26 |

Statistical comparisons of diagnostic groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All body areas | 0.323 ± 0.373 (t19 = 3.86, p = 0.001) |

0.171 ± 0.380 (t21 = 2.11, p = 0.047) |

−0.202 ± 0.389 (t25 = −2.65, p = 0.014) |

overall: F2,65 = 11.75, p < 0.001 rBPD vs HC: t40 = −1.30, d = 0.40, p = 0.200 cBPD vs HC: t44 = −4.61, d = 1.37, p < 0.001* cBPD vs rBPD: t46 = −3.35, d = 0.97, p = 0.002* |

| Body areas with sexual connotation | 0.270 ± 0.567 (t19 = 2.13, p = 0.046) |

−0.300 ± 0.585 (t21 = −2.41, p = 0.025) |

−0.346 ± 0.440 (t25 = −4.01, p = 0.001) |

overall: F2,65 = 9.01, p = 0.0004 rBPD vs HC: t40 = −3.20, d = 0.99, p = 0.003* cBPD vs HC: t44 = −4.15, d = 1.24, p < 0.001* cBPD vs rBPD: t46 = −0.31, d = 0.09, p = 0.757 |

| Neutral body areas | 0.379 ± 0.351 (t19 = 4.82, p < 0.001) |

0.331 ± 0.320 (t21 = 4.85, p < 0.001) |

−0.019 ± 0.436 (t25 = −0.23, p = 0.822) |

overall: F2,65 = 7.94, p = 0.001 rBPD vs HC: t40 = −0. 46, d = 0.14, p = 0.645 cBPD vs HC: t44 = −3.33, d = 0.99, p = 0.002* cBPD vs rBPD: t46 = −3.12, d = 1.18, p = 0.003* |

| Body areas with sexual connotation vs neutral body areas | −0.109 ± 0.464(t19 = −1.05, p = 0.307) | −0.631 ± 0.531 (t21 = −5.58, p < 0.001) |

−0.327 ± 0.361 (t25 = −4.62, p < 0.001) |

overall: F2,65 = 7.12, p = 0.0016 rBPD vs HC: t40 = −3.38, d = 1.04, p = 0.002* cBPD vs HC: t44 = −1.79, d = 0.53, p = 0.080 cBPD vs rBPD: t46 = 2.35, d = 0.68, p = 0.023 |

*These post hoc tests remain statistically significant after Bonferroni-correction.

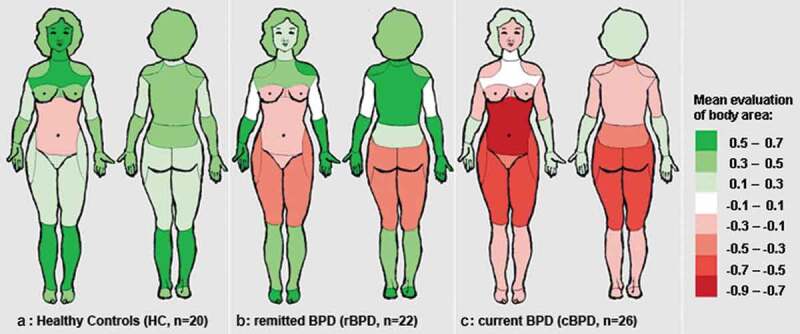

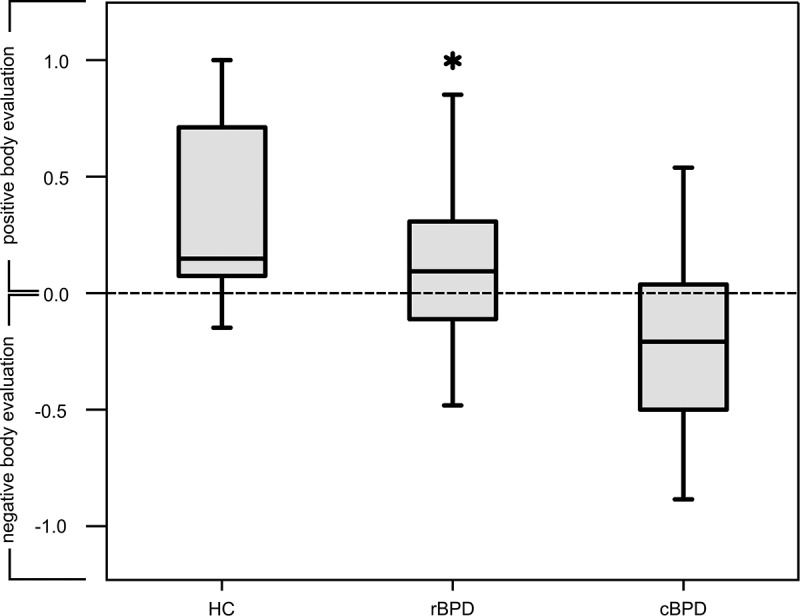

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall evaluation of the own body was positive in the majority of women from the HC group. Accordingly, the mean evaluation of all body areas was significantly different from zero (0.32 ± 0.37, t(19) = 3.86 p = 0.001). Remarkably, the overall evaluation of the own body in the group of individuals who had remitted from BPD (rBPD) was also larger than zero (0.17 ± 0.38, t(21) = 2.11, p = 0.047), which indicates a predominantly positive body evaluation in these individuals. In contrast, the group of patients from the cBPD group exhibited a significantly negative overall evaluation of their body (−0.20 ± 0.39, t(25) = −2.65, p = 0.014). The differences between the groups’ overall evaluation of the body are visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Average evaluation of body areas in A: healthy controls (HC), B: participants who have remitted from borderline personality disorder (rBPD), and C: participants with a current diagnosis of borderline presonality disorder (cBPD).

Figure 2.

Box plots for the evaluation of the own body in the three diagnostic groups. HC = healthy controls, rBPD = remitted borderline personality disorder, cBPD = current borderline personality disorder. Values range from −1 (= 100% negative) to +1 (= 100% positive). Outliers are marked by an asterisk.

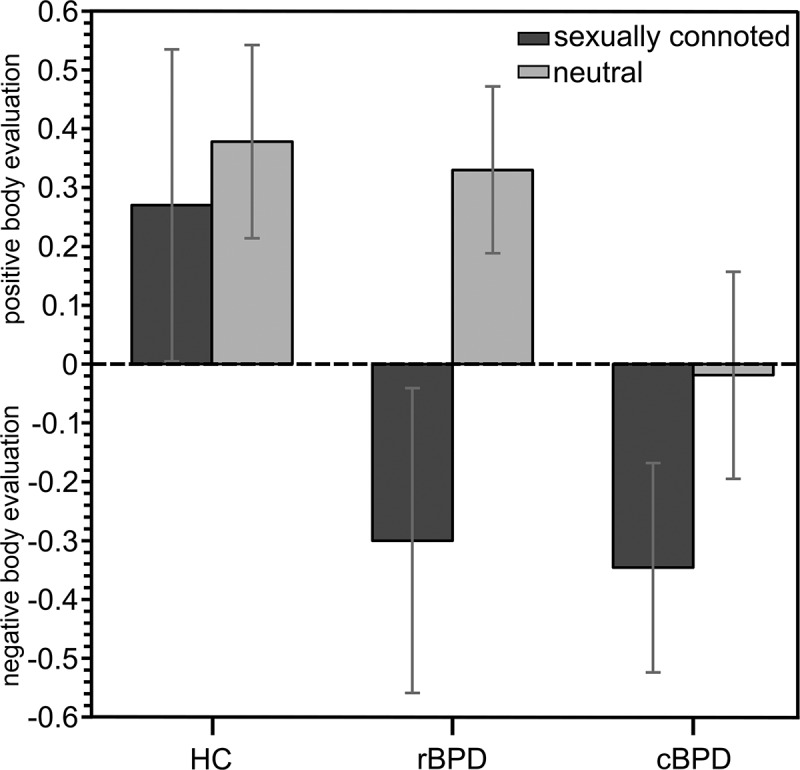

3.2.2. Evaluation of sexually connoted and neutral body areas

The evaluation of sexually connoted body areas was significantly different in the three groups (F(2,65) = 9.01, p < 0.001, for post-hoc tests see Table 1). While the evaluation of body areas that typically have a sexual connotation was positive in healthy participants (0.27 ± 0.57, t(19) = 2.13, p = 0.046), this evaluation was negative in particpiants who have remitted from BPD (−0.30 ± 0.58, t(21) = −2.41, p = 0.025) and in participants with a current BPD diagnosis (−0.35 ± 0.44, t(25) = 4.01, p < 0.001).

The three groups also differed with respect to the evaluation of neutral body areas (F(2,65) = 7.01, p = 0.001, for post-hoc tests see Table 1). However, there was a different pattern than for the evaluation of sexually connoted areas: The evaluation of neutral body areas was highly positive in both the HC and rBPD groups (0.38 ± 0.35, t(19) = 4.82, p < 0.001, and 0.33 ± 0.32, t(21) = 4.85, p < 0.001), while it was essentially indifferent in the cBPD group (−0.02 ± 0.28, t(25) = −0.23, p = 0.822). The differentiation between sexually connoted and neutral areas is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mean evaluation of sexually connoted vs neutral body areas in healthy control participants (HC), in participants who have remitted from borderline personality disorder (rBPD), and in participants with current borderline personality disorder (cBPD). Values range from −1 (= 100% negative) to +1 (= 100% positive). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Accordingly, the delta-scores (i.e. the differences between sexually connoted and neutral body areas) across the three groups differed significantly (F(2,65) = 7.12, p = 0.002). In the HC group, the mean delta-score was small and not statistically different from 0 (−0.11 ± 0.46, t(19) = −1.05, p = 0.307). In contrast, these delta-scores were negative and highly significant for both the rBPD (−0.63 ± 0.53, t(25) = 5.58, p < 0.001) and cBPD (−0.33 ± 0.36, t(21) = −4.62, p < 0.001) groups. The delta-score was particularly pronounced in the group of remitted BPD: In contrast to the negative evaluation of sexually connoted areas, the evaluation of non-sexual areas was clearly positive (see above).

In a post-hoc analysis, the delta-scores of sexually connoted minus neutral body areas were regressed on the subscale ‘Sexual Abuse’ of the CTQ while controlling for the CTQ total score, separately for cBPD and rBPD. In these analyses, CSA emerged as a significant predictor in the group of rBPD, i.e. a high level of CSA was related to a significant difference in the evaluation of sexually connoted versus neutral body areas (β = −0.103 ± 0.035, p = 0.010). Post-hoc analyses revealed that this significance can be explained by the negative relation between high scores of sexual abuse and the evaluation of sexually connoted body areas (β = −0.100 ± 0.040, p = 0.024). In contrast, CSA was not significantly related to the evaluation of neutral body areas in rBPD (β = −0.013 ± 0.020, p = 0.521). In the group of cBPD, CSA did not emerge as a predictor for the delta-score or to the evaluation of specific body areas (delta-score: β = 0.011 ± 0.016, p = 0.515; sexually connoted areas: β = 0.002 ± 0.020, p = 0.920; neutral areas: β = 0.003 ± 0.026, p = 0.923). Entering lifetime diagnoses of post-traumatic stress-disorder, major depressive disorder, and eating disorders as additional regressors to the models did not affect the essence of these results. In particular, CSA still was a significant predictor in the group of rBPD, but not in the group of cBPD.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to quantify the evaluation of the own body in women with a current diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (cBPD) and those who had remitted from BPD (rBPD), and to compare the resulting scores with those obtained from female healthy controls (HC). Furthermore, we investigated the potentially moderating role of the topography of body areas (sexually connoted versus neutral areas) and of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Overall, rBPD participants showed a significantly positive evaluation of their own body, which was not significantly different from HC. At this respect, they were clearly different from the group with cBPD who evaluated their own body as significantly negative. As evidenced by more detailed analyses accounting for the topography of body areas, there was a difference between the rBPD and HC groups in terms of body areas that typically have a sexual connotation. For theses body areas the difference between the rBPD and HC groups was large (d = 0.99) and highly significant while the difference between these two groups with respect to neutral areas was small (d = 0.14) and not significant. A history of CSA emerged as a significant predictor for the evaluation of sexually connoted body areas only in rBPD. In sum, in women who have remitted from a BPD, the evaluation of sexually connoted body areas resembled the evaluation of women with a current diagnosis of BPD whereas the evaluation of neutral body areas resembled the evaluation of healthy women who have no history of BPD or other mental disorders. CSA was found to be a moderator of sexually connoted body area evaluation after remission of the disorder.

These findings add to the extant literature at several respects. Firstly, our results regarding body evaluation in the cBPD group confirm previous findings which reported that the overall body image is negative in women with a current BPD (Haaf et al., 2001; Kleindienst et al., 2014; Sansone, Chu, & Wiederman, 2010; Sansone, Wiederman, & Monteith, 2001). In addition, our results correspond to those from previous studies hereby confirming that body evaluation in the group of cBPD is in sharp contrast to mentally healthy women who typically reported a positive attititude towards their own body (Haaf et al., 2001; Kleindienst et al., 2014). However, the separate analyes of sexually connoted and neutral body areas revealed that the overall neagtive evaluation in cBPD might be driven by a negative evaluation of the sexually connoted body areas wheras neutral body areas were evaluated as neutral in cBPD. Because our study is the first to systematically investigate body evaluation in women who have remitted from BPD, our findings regarding this group clearly extend previous findings. The observation that body evaluation in rBPD women is mostly positive is in line with evidence showing that important aspects of the psychopathology of BPD are amenable to change (Temes & Zanarini, 2018).

The sharp contrast between the positive evaluation of neutral body areas and the negative evaluation of sexually conoted areas in rBPD has not been reported in previous studies. Furthermore, our study was the first one to detect an impact of the severity of CSA on the negative evaluation of sexually connoted (but not on the evaluation of neutral) body areas. If replicated, these findings would indicate that the impact of CSA is particularly longlasting for the evaluation of sexually connoted body areas in women with BPD, hereby refining previous findings regarding the consequences of CSA in BPD (for an overview see de Aquino Ferreira et al., 2018). However, since the quality of sexual life was not assessed in the present study, the relatonship between a history of CSA and the quality of sexual relationships remains unclear and requires further investigation. On the one hand, Karan, Niesten, Frankenburg, Fitzmaurice, and Zanarini (2016) reported that difficulties in sexual relationships are not chronic in patients with BPD, especially after a symptomatic remission has been attained. On the other hand, Kearney-Cooke and Ackard (2000) reported that women with a history of sexual abuse displayed a more negative overall body image and less comfort with having sex than women without a history of sexual abuse.

Besides CSA, other sources, such as negative self-related emotions, might contribute to the differential evaluation of body areas in rBPD. In particular, BPD is characterized by high levels of self-disgust (Schienle, Haas-Krammer, Schöggl, Kapfhammer, & Ille, 2013; Winter, Bohus, & Lis, 2017) and bodily shame (Scheel et al., 2014). Whether or not these negative emotions are specifically pronounced for sexually connoted body areas in BPD, remains uncovered, since these aspects have not been assessed in the present study. Disgust and shame (Rüsch et al., 2007, 2011), however, may be key targets for psychotherapeutic interventions in borderline personality disorder, and if these emotions contribute to the differential effect found in the present study, our results might provide starting points for achieving more comprehensive effects in the treatment of BPD patients.

Several limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results. Most importantly, we have to emphasize that our study is cross-sectional. Accordingly, it must be kept in mind that all inferences about causal relationships remain largely speculative. Specifically, our major findings referring to the rBPD group should be established from a longitudinal study before drawing conclusions about the course of body evaluation from current to remitted BPD. Another limitation relates to the relatively small sample size. While the sample size was sufficient to establish statistical significance for several major findings, our study was underpowered to detect small to medium effects. Finally, it should be borne in mind that our sample was recruited at a specialized university setting and only included female patients with a maximum age of 50 years. Since sex and age may impact body dissatisfaction (Grogan, 1999), the external validity of our findings is somewhat restricted, and should not be extrapolated to other age groups or to a male population, unless our findings have been replicated in a more diverse sample.

Despite these limitations, it may be concluded that women who have remitted from BPD show a generally positive evaluation of their body while a predominantly negative evaluation of sexually connoted body areas remains an issue in this population. This negative evaluation of sexually connoted body areas was related to CSA in the rBPD group. Besides replicating these findings, future research might investigate potential consequences of a highly negative body evaluation of sexually connoted body areas on relevant variables such as a sexual satisfaction, partnership, self-confidence, or quality of life (Gillen & Markey, 2019). Prospective studies will be needed to clarify the interplay between body-related issues (which are normal transient phenomena in adolescence) and the development and treatment of BPD. A persistently negative body evaluation may be both a precursor or a consequence of BPD. At any rate, the pervasively negative body evaluation in cBPD and the selectively negative body evaluation in rBPD both suggest developing a more systematic evaluation of treatment modules (e.g. mirror confrontation) addressing the evaluation of the own body in women treated for BPD.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the project ‘Mechanisms of disturbed emotion processing in borderline personality disorder’, which received funding from a Clinical Research Unit program (KFO-256 – start-up funding grant and BE 5723/1-2 (both awarded to RBB)) of the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RBB, upon reasonable request.

References

- Ålgars, M., Santtila, P., Jern, P., Johansson, A., Westerlund, M., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2011). Sexual body image and its correlates: A population-based study of Finnish women and men. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(1), 26–11. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P., Gervais, S. J., Allen, J., Campomizzi, S., & Klein, O. (2012). Integrating sexual objectification with object versus person recognition: The sexualized- body-inversion hypothesis. Psychological Science, 23(5), 469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P., Gervais, S. J., Allen, J., Delmée, A., & Klein, O. (2015). From sex objects to human beings: Masking sexual body parts and humanization as moderators to women’s objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(4), 432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., … Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R. D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., … Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): Development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolla, R., Cavicchioli, M., Galli, M., Verschure, P. F., & Maffei, C. (2019). A comprehensive evaluation of emotional responsiveness in borderline personality disorder: A support for hypersensitivity hypothesis. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (2002). Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, B. Y., Hensel, S., Schmidinger, I., Bekrater‐Bodmann, R., & Flor, H. (2020). Dissociation proneness and pain hyposensitivity in current and remitted borderline personality disorder. European Journal of Pain. epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, R. D. (1979). Influential observations in linear regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(365), 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Aquino Ferreira, L. F., Pereira, F. H. Q., Benevides, A. M. L. N., & Melo, M. C. A. (2018). Borderline personality disorder and sexual abuse: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 262, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, A., Hennrich, L., Borgmann, E., White, A. J., & Alpers, G. W. (2013). Body image and noticeable self-inflicted scars. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(12), 1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C. K. (2006). A primer on the use of modern missing-data methods in psychosomatic medicine research. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(3), 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson, D. M., McLeod, G. F., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(9), 664–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, S. J., Vescio, T. K., Förster, J., Maass, A., & Suitner, C. (2012). Seeing women as objects: The sexual body part recognition bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 743–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen, M. M., & Markey, C. H. (2019). A review of research linking body image and sexual well-being. Body Image, 31, 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn C. R., Klonsky E. D. (2009).. Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 23(1), 20–28. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan, S. (1999). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, J. G., Stout, R. L., McGlashan, T. H., Shea, M. T., Morey, L. C., Grilo, C. M., … Ansell, E. (2011). Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: Psychopathology and function from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 827–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaf, B., Pohl, U., Deusinger, I. M., & Bohus, M. (2001). Examination of body concept of female patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 51, 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J. L., Perry, C., & Van der Kolk, B. A. (1989). Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben, M., Claes, L., Sleuwaegen, E., Berens, A., & Vansteelandt, K. (2018). Emotional reactivity to appraisals in patients with a borderline personality disorder: A daily life study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish, L., Kobayashi, I., & Delahanty, D. L. (2010). Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karan, E., Niesten, I. J., Frankenburg, F. R., Fitzmaurice, G. M., & Zanarini, M. C. (2016). Prevalence and course of sexual relationship difficulties in recovered and non‐recovered patients with borderline personality disorder over 16 years of prospective follow‐up. Personality and Mental Health, 10, 232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazuko, T., & Inoue, K. (2009). Discriminative features of borderline personality disorder. Shinrigaku Kenkyu, 79, 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney-Cooke, A., & Ackard, D. M. (2000). The effects of sexual abuse on body image, self-image, and sexual activity of women. The Journal of Gender-specific Medicine, 3, 54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst, N., Priebe, K., Borgmann, E., Cornelisse, S., Krüger, A., Ebner-Priemer, U., & Dyer, A. (2014). Body self-evaluation and physical scars in patients with borderline personality disorder: An observational study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 364, 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, A., Kleindienst, N., Cackowski, S., Schmidinger, I., & Bekrater-Bodmann, R. (2020). Reductions in whole-body ownership in borderline personality disorder – A phenomenological manifestation of dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21, 264–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger, A. W. (1999). International personality disorder examination (IPDE): DSM-IV and ICD-10 modules. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Miano, A., Fertuck, E. A., Roepke, S., & Dziobek, I. (2017). Romantic relationship dysfunction in borderline personality disorder-a naturalistic approach to trustworthiness perception. Personality Disorders, 8(3), 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, F. Y., Townsend, M. L., Miller, C. E., Jewell, M., & Grenyer, B. F. (2019). The lived experience of recovery in borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 6, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, N., Lieb, K., Göttler, I., Hermann, C., Schramm, E., Richter, H., … Bohus, M. (2007). Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, N., Schulz, D., Valerius, G., Steil, R., Bohus, M., & Schmahl, C. (2011). Disgust and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 261, 369–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack, M., Boroske-Leiner, K., & Lahmann, C. (2010). Association of nonsexual and sexual traumatizations with body image and psychosomatic symptoms in psychosomatic outpatients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, R. A., Chu, J. W., & Wiederman, M. W. (2010). Body image and borderline personality disorder among psychiatric inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51, 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, R. A., Wiederman, M. W., & Monteith, D. (2001). Obesity, borderline personality symptomatology, and body image among women in a psychiatric outpatient setting. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel, C. N., Bender, C., Tuschen-Caffier, B., Brodführer, A., Matthies, S., Hermann, C., … Jacob, G. A. (2014). Do patients with different mental disorders show specific aspects of shame? Psychiatry Research, 220, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle, A., Haas-Krammer, A., Schöggl, H., Kapfhammer, H. P., & Ille, R. (2013). Altered state and trait disgust in borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201, 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl, C., Herpertz, S. C., Bertsch, K., Ende, G., Flor, H., Kirsch, P., … Spanagel, R. (2014). Mechanisms of disturbed emotion processing and social interaction in borderline personality disorder: State of knowledge and research agenda of the German clinical research unit. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami, V., Weis, L., Barron, D., & Furnham, A. (2018). Positive body image is positively associated with hedonic (emotional) and eudaimonic (psychological and social) well-being in British adults. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temes, C. M., & Zanarini, M. C. (2018). The longitudinal course of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 41, 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J., Heinberg, L., & Altabe, M. (1999). Exacting beauty. Theory, assessment and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, K. E., & Thompson, J. K. (1997). Overt and covert sexual abuse: Relationship to body image and eating disturbance. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22, 273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D., Bohus, M., & Lis, S. (2017). Understanding negative self-evaluations in borderline personality disorder—A review of self-related cognitions, emotions, and motives. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen, H., Zaudig, M., & Fydrich, T. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus-Horvath, C. L. (2010). “But I like my body”: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7, 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Reich, D. B., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2012). Attainment and stability of sustained symptomatic remission and recovery among patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects: A 16-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 476–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RBB, upon reasonable request.