Abstract

Background & purpose

In response to the COVID-19 (C-19) pandemic, the South African government instituted strict lockdown and related legislation. Although this response was well intended, many believed it advanced children’s vulnerability to abuse and neglect. This article interrogates these concerns. It investigates how C-19 legislation enabled, or constrained, South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect and appraises the findings from a social-ecological resilience perspective with the aim of advancing child protection in times of emergency.

Method

The authors conducted a rapid review of the legislation, directives and regulations pertaining to South Africa’s strict lockdown (15 March to 31 May 2020). They searched two databases (SA Government platform and LexisNexus) and identified 140 documents for potential inclusion. Following full-text screening, 17 documents were reviewed. Document analysis was used to extract relevant themes.

Findings

The regulations and directives that informed South Africa’s strict lockdown offered three protective pathways. They (i) limited C-19 contagion and championed physical health; (ii) ensured uninterrupted protection (legal and statutory) for children at risk of abuse; and (iii) advanced social protection measures available to disadvantaged households.

Conclusion

C-19 legislation has potential to advance children’s protection from abuse and neglect during emergency times. However, this potential will be curtailed if C-19 legislation is inadequately operationalised and/or prioritises physical health to the detriment of children’s intellectual, emotional, social and security needs. To overcome such risks, social ecologies must work with legislators to co-design and co-operationalise C-19 legislation that will not only protect children, but advance their resilience.

Keywords: Covid-19, child protection, resilience, South Africa, rapid review

1. Introduction

COVID-19 (C-19) has not been kind to the health or wellbeing of the world’s children. All the same, children in low-and-middle-income (LMIC) contexts are especially vulnerable to the pandemic’s negative effects (Simba et al., 2020). Their vulnerability relates to the resource-constrained nature of their physical, social, and service ecologies. Moreover, lockdown conditions, which have been an almost universal response to the C-19 pandemic, are likely to further constrain children’s access to resources and undermine their fundamental right to be cared for and protected from abuse and neglect (Teo and Griffiths, 2020). Amongst others, there are concerns about how lockdown conditions are increasing children’s exposure to domestic violence (Bradbury‐Jones & Isham, 2020), and decreasing their access to basic resources, including food and education (Clark et al., 2020). In many countries, C-19-specific legislation has been introduced as one form of response to such concerns.

In this article, we critically consider South Africa’s legislative response to the C-19 pandemic, with special interest in its potential to facilitate the care and protection of children in the face of strict lockdown conditions. We juxtapose this potential with reports of C-19 lockdown-related impacts on South African children’s health and wellbeing and use the conclusions to urge societies to go beyond legislation to advance the resilience of children to C-19 lockdown conditions that heighten the chances for child maltreatment.

From a social-ecological perspective, resilience is a process that supports children to avoid or manage the disruptive effects of extreme stressors (Masten, 2014). This process draws on resources within children (e.g., a strong immune system, capacity to self-regulate, or intelligence) and the social-ecological systems they are connected to (e.g., a well-functioning family, supportive schools, or enabling legislation) (Masten & Cicchetti, 2016). Essentially, what limits the disruptive effects of significant stressors is when children are supported by their social ecologies to access basic resources; enjoy nurturing relationships; have a powerful identity; behave in culturally valued ways; know social and/or spiritual cohesion; exercise control and efficacy; and experience social justice (Ungar, 2015; Ungar et al., 2007). Typically, the protective value and expression of the aforementioned are shaped by a child’s situational and cultural context (Ungar & Theron, 2020). For instance, although some schools have responded to the C-19 health crisis by shifting daily, in-person teacher-child interaction to regular and virtual teacher-child interaction, this adjusted form of relating has reduced protective value for children without access to digital resources and electricity (Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020). Thus, in the interests of minimising the negative health and wellbeing effects of living in a disadvantaged or violent household in the face of C-19, greater attention is required to how social ecologies might support children in contextually responsive ways.

2. C-19 in the South African Context

The first C-19 case was reported in South Africa on 5 March 2020. Within 10 days (i.e., on 15 March), a National State of Disaster (with restrictions on the size of public gatherings and foreign nationals’ entrance to South Africa) was declared by the President of South Africa, as per the Disaster Management Act, 57 of 2002 (hereinafter the Disaster Management Act). Even though the number of confirmed cases was still low then (61 cases; no casualties), there were concerns about the health-care system’s capacity to respond effectively to an increased number of cases. Given widespread disadvantage in South Africa, and associated challenges of overcrowded households and densely populated neighbourhoods (Naidu, 2020), there were also expectations of rapid viral spread.

On 23 March 2020, the president announced a 3-week national lockdown starting on 26 March 2020(which was extened for another two weeks until 30 April 2020). The media dubbed this “hard lockdown”. Its main objective was to curb the spread of C-19 and safeguard the physical health of all South Africans, including children. To reach this objective, the movement of all people in South Africa was restricted. Only those who provided essential services could continue with their daily work; all others were restricted to their places of residence. Schools were closed, and the sale of goods was limited to essential goods (such as food). Lockdown was enforced by the combined forces of the South African Police Services and the South African National Defence Force. Patrols and roadblocks were common.

On 29 April 2020, the South African government published details of a new risk-adjusted strategy. It included five alert levels (levels 5 through to 1, with lower levels representing fewer restrictions). On 1 May 2020, Level 5 (the so-called “hard lockdown”) was replaced with Level 4. This brought minimal relaxation in the restrictions (e.g., the sale of stationery and educational books was permitted, as was restaurant food-delivery service; select businesses were permitted to operate at 50% staff capacity). Despite such easing, South Africa’s lockdown was described as “one of the most rigid and extreme lockdowns announced anywhere in the world” (Habib, 2020).

The Disaster Management Act afforded the Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA) the power to institute certain restrictions on the rights of citizens. The same Act allowed the establishment of a National Disaster Management Centre directed by the Minister of COGTA. Its duty was to make recommendations on draft legislation aimed at combatting the national disaster. Together with the Minister of COGTA and the National Disaster Management Centre, cabinet ministers (i.e., the executive arm of the South African Government) were key role players in the coordination and management of the C-19 disaster. C-19-related regulations from the Minister of COGTA and relevant cabinet ministers were published in the Government Gazette and used, inter alia, to regulate the movement of people and goods and to provide relief to those in need of social services.

The lockdown was associated with economic disaster. Results from the first wave of the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) study showed substantial C-19 related declines in employment among the South African households surveyed in May 2020 (n = 7000), with losses skewed towards more disadvantaged households (Spaull et al., 2020). In South Africa, where disadvantage is rooted in Apartheid policies and practices that were biased against people of colour and women, the race, gender and education of the household-head typically predict household disadvantage (Mhlongo, 2019). Increased economic strain means that children are more likely to experience food insecurity and inadequate health and other forms of care, and so it was not surprising that the NIDS-CRAM study included reports of child hunger from 15% of the surveyed South African households (Wills et al., 2020). Prior to lockdown, 59% of South Africa’s 19.7 million children lived below the country’s upper-bound poverty line (around USD$78 per person per month), almost two thirds of received a child support grant and 11% lived in households that reported child hunger (Shung-King et al., 2019).

Further, the C-19-related closure of government schools during strict lockdown had significant ramifications for the nine million South African children who rely on school feeding schemes, with some contending that disrupted access to school feeding schemes is tantamount to “a form of abuse or neglect” (van Bruwaene et al., 2020). School closure also raised concerns about South African children’s rights to education and educational progress, particularly for those from households without digital resources (Wolfson Vorster, 2020). School closure was also expected to complicate access to medical and support services, as South African schools typically facilitate such access for children from disadvantaged homes (Mphahlele, 2020).

The media reported that violence against South Africa’s children increased during lockdown (Lund et al., 2020; Nkomo, 2020). Similarly, a report by a child-dedicated crisis line for the lockdown period 27 March to 30 April noted a 67% increase in calls and a 400% increase in cases opened and counselling sessions, compared to the same period in 2019 (Childline Gauteng, 2020). Although the highest number of calls related to C-19-associated anxieties and challenges, reports of abuse constituted the second highest number and reflected a 61.6% increase compared to the same period in 2019. Emotional abuse was most prevalent, followed by physical and sexual abuse. These media and non-governmental organisation reports were in stark contrast to government communication that domestic violence, including incidences of abuse, decreased during strict lockdown (South African Government, 2020). However, the media and non-governmental reports were not surprising given pre-COVID studies of sexual and other forms of violence against children in South Africa. The nationally representative Optimus study, for example, found a general prevalence rate of just over 12% for any form of sexual violence, emotional abuse, or neglect (Ward et al., 2018). The study also reported prevalence rates of 18% for physical abuse and 24.6% for family violence. In addition, more than half of all participants reported other forms of direct or indirect exposure to violence, mostly crime related. Despite this prevalence and the fact that South Africa is characterised as a country challenged by high levels of continuous traumatic stress (Kaminer et al., 2018), children from disadvantaged households in South Africa have no or limited access to psychological or other mental health services (Bukola et al., 2020). More typically, according to the Integrated Service Delivery Model, the Department of Social Development (DSD) is required to support children to manage experiences of violence (DSD, 2005). DSD also renders statutory services to safeguard children in need of care and protection, including children who are in conflict with the law or require rehabilitation. Families whose children were removed from their care are entitled to family reunification services (Children’s Act, 2005). DSD also provides drop-in-centres that offer a form of home-based care to children who are vulnerable (Mahlase & Ntombela, 2011; Shung-King et al., 2019).

2.1. The present study

Children’s basic rights to protection were enshrined in South Africa’s constitution (The Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996), and further mandated (e.g., the Children’s Act, 2005). During a National State of Disaster, such as the C-19 pandemic, the South African state must ensure that the constitutional rights of its children to be protected against any form of abuse and neglect are upheld. However, there are concerns that the national lockdown initiated on 26 March 2020 as part of the South African government’s state-of-disaster response to C-19, disrupted children’s access to the abovementioned and other crucial resources, worsened children’s household disadvantage and made children more vulnerable to abuse and neglect (Madonsela, 2020; Mphahlele, 2020; Nkomo, 2020; van Bruwaene et al., 2020; Wills et al., 2020). To better understand the implications of alert levels 4 and 5 (hereafter referred to collectively as “strict lockdown”) for South African children’s vulnerability to abuse and neglect, as directed by associated state-of-emergency legislation, we conducted a rapid review of the relevant legislation using the method described next.

Our review was directed by the following questions: How does the C-19 legislation and secondary legislation (i.e., regulations and directives), relevant to strict lockdown, potentially enable South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect? Might this same legislation and secondary legislation potentially constrain South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect, and if so, how? As per the Children’s Act of SA (2005), we defined abuse as deliberate physical, sexual, emotional or psychological harm or ill-treatment to a child, including (but not limited to) assault, bullying, injury, sexual abuse, and exploitative labour. Likewise, neglect was defined as the failure to “provide for the child’s basic physical, intellectual, emotional or social needs” (p.24). In order to advance child protection in times of emergency more generally, we interpreted the answers to these questions from a social-ecological resilience perspective.

3. Methodology

Following Watson et al. (2017) we conducted a rapid review of the South African government’s C-19 legislation, regulations and directives pertaining to strict lockdown and followed a document analysis approach to data analysis. A rapid review is a methodology used for developing a timely but comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon (Garritty et al., 2020). In comparison with other review methodologies, the emphasis in a rapid review is on providing evidence-informed insights in a relatively short period of time, often in response to a health crisis (Ganann et al., 2010). Given the current concerns about lockdown restrictions’ implications for South African children’s vulnerability to abuse and neglect, and the calls for social scientists to guide legislation and other government decisions (Madonsela, 2020), a rapid review was appropriate.

3.1. Search strategy

Due to the focus of the two research questions that informed our study, only grey literature was considered (i.e., South African legislation and secondary legislation relevant to the National State of Disaster). An information specialist advised us to conduct our search on the official SA Government platform where published legal documents, such as regulations and directives related to C-19 and a legal database, are found. We also accessed LexisNexus which is a provider of content and technology solutions, including content of a legal nature.

The first author and a post-graduate research assistant searched these platforms using the following search terms, “Covid-19” OR “Coronavirus” AND “regulations”, “directions”, “directives”, “legislations” AND “South Africa”. The initial search yielded 140 full-length documents. They were collated in EndNote X9 (2019) and exported to Rayyan, a web application for screening purposes (Ouzzani et al., 2016).

Authors AF and DFF screened the full-length documents to determine inclusion eligibility; using a blind procedure function in Rayyan, and the third author (LT) provided a consensus vote in eight instances where the screening authors disagreed. The following eligibility criteria were applied: legislation, regulation or directives relevant to strict lockdown conditions (levels 5 and 4); published for the period 15 March – 31 May (i.e., from the announcement of the National State of Disaster to the final day of level 4 restrictions); and content relevant to child abuse or neglect. As English is the official language of communication by the South African government, only English publications were included. Regulations applicable to alert levels 1—3 (i.e., not strict lockdown) were excluded. These inclusion/exclusion criteria determined that 117 documents were ineligible as they were regulations related to protective measures relevant to the Fishing industry; Higher Education, Safety in the Workplace, Correctional Services; Immigration, Sports and Culture; Mineral Sources, Health Protocols and Labour matters (i.e., irrelevant to protection of children).

3.2. Data extraction

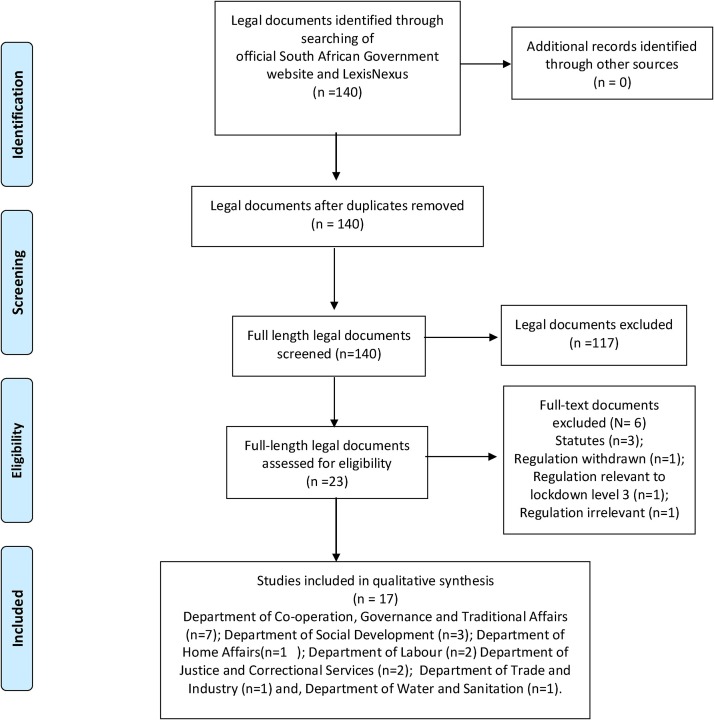

After the 23 eligible full-length documents were imported into Atlas.Ti scientific software, document analysis followed an iterative process combining elements of qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis (Bowen, 2009). Authors AF and LT, both of whom are experienced qualitative researchers and skilled in thematic and content qualitative data analysis, read through the documents and developed a coding framework. In line with the definition of child neglect, this framework included codes relevant to children’s physical, intellectual, emotional, and social needs (e.g., access to health services enabled; access to health services constrained; access to formal education enabled; access to formal education constrained). The framework also included codes relevant to child abuse (e.g., access to court enabled; access to court constrained; safeguarding of children enabled; safeguarding of children constrained). Once these two authors had piloted and tweaked the framework, the documents were independently coded by authors DFF and AF. In this process, a further six documents were excluded (see Fig. 1 for reasons). Subsequently, 17 documents were considered for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process.

Next, the codes were developed into preliminary categories relevant to our focus on legislation and child abuse and neglect. These categories formed the basis of the analytical framework that included the ministry that issued the legislation; measures that could protect children against abuse and neglect during strict lockdown; and measures that could constrain children’s protection against abuse and neglect during strict lockdown. These same categories informed the data extraction chart (see Table 1 ), which included the following items: Name of state department, title of legislation/secondary legislation, date issued, publication details, and focus of the said documents.

Table 1.

Summary of extracted data

| n | Government department issuing regulation/directive/ directions |

Title of regulation / directive/directions | Government Gazette number & page numbers | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020a, March 18). | Regulations in terms of section 27(1) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 318). | Government Gazette, 43107, p. 3-11. |

|

| 2 | Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020b, March 25). | Amendments of regulations in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 398). | Government Gazette, 43148, p. 3-13. |

|

| 3 | Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020c, March 25). | Directions in terms of section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 399). | Government Gazette, 43147, p. 3-13 |

|

| 4 | Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020d, March 26). | Amendments of regulations in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 419). | Government Gazette, 43168, p. 3-5. |

|

| 5 | Department of Labour, South Africa (2020a, March 26). | Directive in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 215). | Government Gazette, 43161, p. 3-10. |

|

| 6 | Department of Social Development, South Africa (2020a, March 30). | Directions in terms of regulation 10(5) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 430). | Government Gazette, 43182, p. 3-10. |

|

| 7 | Department of Justice and Correctional Services, South Africa (2020a, March 31). | Directions in terms of regulation 10 under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 440). | Government Gazette, 43191, p. 3-12. |

|

| 8 | Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020e, April 2). | Amendments of regulations issued in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 446). | Government Gazette, 43199, p. 3-17. |

|

| 9 | Department of Social Development (South Africa). (2020b, April 7). | Amendment to directions in terms of regulation 10(8) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 455). | Government Gazette, 43213, p. 3-5. |

|

| 10 | Department of Labour, South Africa (2020b, April 8). | Amendment of directive in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 240). | Government Gazette, 43216, p. 3-6. |

|

| 11 | Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa (2020, April 15). | Directions in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 464). | Government Gazette, 43231, p. 3-11. |

|

| 12 | Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020f, April 16). | Amendments of regulations issued in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 465). | Government Gazette, 43232, p. 3-9. |

|

| 13a | Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs, South Africa (2020g, April 29). | Regulations in terms of section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 480). | Government Gazette, 43258, p. 3-38. |

|

| 14 | Department of Justice and Correctional Services, South Africa (2020b, May 4) | Directions in terms of regulation 4(2) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 489). | Government Gazette, 43268, p. 3-16. |

|

| 15 | Department of Home Affairs, South Africa (2020, May 9). | Amendment of directions in terms of regulation 10(8) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 518). | Government Gazette, 43301, p. 3-6. |

|

| 16 | Department of Social Development, South Africa (2020c, May 9). | Amendment to directions in terms of regulation 4(5) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002 (Notice 517). | Government Gazette, 43300, p. 3-12. |

|

| 17 | Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, South Africa (2020, May 12). | Directions in terms of regulation 4(10)(a) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act. 57 of 2002 (Notice 523). | Government Gazette, 43307, p. 3-8. |

|

This regulation consolidates, replace and extend the previous regulations issued by the Minister of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs.

For each of the included publications, data were charted by DFF (a legal professional and skilled in document analysis and interpretation of legal documents) and checked by AF (a social work professional). Following Saldana (2009), AF and DFF held consensus discussions to resolve any discrepancies. This typically entailed verbal explanations of the reasons why data were charted as enabling/constraining child protection. In the rare instance where verbal explanations did not resolve discrepant charting of the data, LCT arbitrated. An inductive content analysis of the data informed three themes (see Findings) and all authors agreed on them.

The seven resources associated with the resilience of children from LMICs – i.e., access to basic resources, nurturing relationships; a powerful identity; opportunities to behave in culturally valued ways; social and/or spiritual cohesion; efficacy; and social justice (Ungar, 2015; Ungar et al., 2007) – were used as in interpretive lens. This lens supported deductions about the potential of C-19 legislation to support the resilience of South African children who are vulnerable to abuse and neglect during strict lockdown. In so doing, our interpretive analysis of the data was deductive (Stuckey, 2015).

4. Findings

Table 1 summarises the focus of the 17 C-19 regulations and directives pertaining to strict lockdown that had the potential to enable, and/or constrain, South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect, either directly or indirectly. Seven of the included regulations and directives were issued by the Department of Co-operation and Governance, one by the Department of Home Affairs, three by the Department of Social Development, two by the Department of Justice and Correctional Services, two by the Department of Labour, one by the Department of Trade and Industry, and one by the Department of Water and Sanitation. The absence of regulations by the Department of Education during strict lockdown is glaring, not least because school-based feeding schemes were suspended as a consequence of school closure.

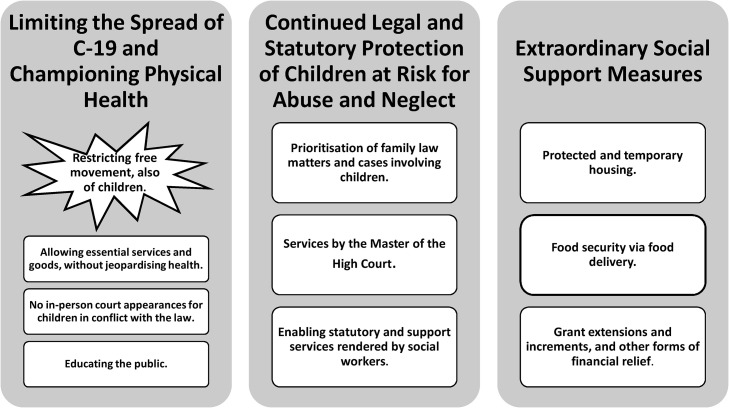

Three themes flow from the content analysis of the above documents: Limiting the spread of C-19 and championing physical health; Continued legal and statutory protection of children at risk for abuse and neglect; and Extraordinary social support measures. As depicted in Fig. 2 , and further detailed in Table 2 , the legislation that enabled protection from exposure to C-19 had obvious potential to constrain children’s protection from abuse and neglect. Such ambivalent protective value is visually cued by the use of an irregular shape (see Fig. 2). Each theme, and its potential to enable or constrain protection from abuse and/or facilitation of basic physical, intellectual, emotional or social needs neglect, is detailed next.

Fig. 2.

Summary of themes and sub-themes pertaining to C-19 legislation’s potential to facilitate child protection from abuse or neglect.

Table 2.

The potential of C-19 legislation to enable/constrain child protection during strict lockdown

| Theme | Sub-themes | Enabling elements | Constraining elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Championing Physical Health |

|

Protection of physical health: In order to physically protect South Africans against C-19 and limit its spread, the National Command Centre authorized a nation-wide lockdown, restricting most people to their homes (Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs of South Africa [Department of COGTA], 2020b). |

Neglect of children’s emotional and social needs: Children who were with a non-resident parent (e.g., with the secondary holder of parental responsibilities) at the time, were not allowed to return to their primary place of residence. Likewise, if children were at their primary place of residence, restriction of movement disrupted in-person contact with a non-resident caregiver (Department of DSD, 2020a). Whilst directives were issued to caregivers who were not with their child to maintain regular communication using electronic means (Department of Social Development [Department of DSD], 2020a), there was potential for absence-related emotional or psychological harm. At the start of strict lockdown, no visits were permitted to child and youth care centres, substance abuse facilities, shelters, or residential facilities for persons with disabilities. All family reunification programmes and releases were suspended (Department of COGTA, 2020a; Department of DSD, 2020a). These strict measures potentiated disrupted familial and social relationships and concomitant risk of emotional or psychological harm, and this could explain why they were subsequently amended. Further restriction of movement occurred at district and metropolitan levels, with municipalities directed to protect their communities against infection by closing of all public spaces, such as swimming pools, libraries and parks (Department of COGTA, 2020c). All public gatherings, including religious services and cultural activities, were stopped and nobody could participate in sport (Department of COGTA, 2020b). Whilst these measures protected children from encountering people who were C-19+, they disrupted children’s access to extramural, cultural or religious activity. Potential to heighten vulnerability to abuse: If children were locked down with abusive adults, restricted movement likely heightened children’s vulnerability to abuse. |

|

Protection of physical health: The Department of Social Development as well as the Department of Basic Education were given a mandate by the Minister of GOGTA to issue determinations to protect children against the harms of C-19 (Department of COGTA, 2020a). Subsequently, all schools and partial care facilities were closed to prevent unnecessary movement of children. |

Neglect of children’s emotional and social needs: School closure meant 9 million children’s access to school-based feeding schemes was obstructed (Mphahlele, 2020). Likewise, unless they had recourse to virtual education opportunities, children’s access to formal education was halted (Wolfson, 2020). | ||

| Recognition of children’s emotional and social needs: One week into strict lockdown, movement across provincial borders was allowed for children for the purpose of funeral attendance, particularly if the deceased was the child’s caregiver (Department of COGTA, 2020E). Similarly, movement of children between co-holders of parental responsibilities and rights was allowed from the second week of strict lockdown. Such movement was regulated through the issuing of a travel permit, granted by a magistrate, after having considered the reasons for travel and ensuring that all the legal requirements (e.g., a court order or a parenting plan registered with the family advocate) were in place (Department of DSD, 2020b). | |||

|

Protection of physical health: The Departments of Health and Social Development were instructed to provide directives for the provision or maintenance of essential health and social services, which included access to medical services, hospital supplies, and medicines (Department of COGTA, 2020e). In partnership with health authorities, municipalities were instructed to provide sanitizers, facial masks and latex gloves at sites where staff and councillors have access to the public (Department of COGTA, 2020c). Access to health establishments were allowed for those in need of treatment or medication (Department of COGTA, 2020g). Municipalities were also directed to provide water and sanitation services for all (Department of COGTA, 2020c). Although the Department of Home Affairs suspended most of its services during the initial period of strict lockdown, it continued to issue birth certificates (Department of COGTA, 2020b). Later, the department’s essential services were extended to include the reissuing of birth and death certificates and registration of births (excluding late registrations). This essential service gives children access to basic health services (Department of Home Affairs, 2020). |

||

|

Protection of physical health: During strict lockdown all matters relating to children who were detained in child and youth care centres were remanded in absentia (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020a). This meant that children were protected from in-person interaction and potential concomitant exposure to C-19. |

||

|

Protection of physical health: Local government structures were instructed to develop and roll out awareness campaigns in their communities. The campaigns aimed to educate communities, including families and children, about C-19. The emphasis was on actions that could be taken to safeguard physical health and curb the spread of the C-19 (Department of COGTA, 2020c). |

||

| Continued Legal and Statutory Protection of Children at Risk for Abuse and Neglect |

|

Protection of children from abuse: Although operations at courts nationwide were halted, allowance was made for matters pertaining to the safeguarding of children. This included matters relating to foster care, adoption, removal of children in need of care and protection, placement of children in youth and childcare centres, and international child abduction cases (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). No new matters were enrolled during strict lockdown, except for new applications for protection orders, domestic violence, and harassment orders (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020a). Sheriffs of the court were directed to only serve processes which were deemed urgent, such as domestic violence protection orders, and harassment orders (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). Similarly, cases pertaining to children awaiting trial at secure care facilities were prioritised (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). Matters relating to children were similarly prioritised in the later part of strict lockdown. For example, directive amendments resulted in an extension of the services by sheriffs of the court. The extension included all urgent court processes in family law matters; applications for protection orders, foster care applications, and hearings; care and contact applications including applications for the removal of children to safe care, international abduction cases, and adoption cases and hearings (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). Criminal trials resumed in the later stage of strict lockdown, but were limited to sexual offences, gender-based violence (GBV) cases and serious violent crimes (i.e., crimes most likely to cause/heighten child vulnerability) (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). |

|

|

Recognition of children’s basic needs and the role of financial security in addressing those needs: The services of the master of the high court were suspended during strict lockdown. However, allowance was made for payments to natural guardians on behalf of minors, where these payments were in respect of maintenance and education. The Master of the High Court also had to accept applications for payments to the benefit of child-headed households, orphans, and the elderly (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020a). Later on in strict lockdown, the Master of the High Court was also allowed to receive applications for payments of funds from the guardians’ fund (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020b). |

||

|

Protection of children from abuse: For children in need of care and protection, placement in alternative care continued. To expedite placement at a place of safety or youth care centre, a social worker’s report constituted sufficient recommendation for the granting of a court order for the removal and placement of a child (Department of DSD, 2020a). The DSD was specifically tasked with identifying temporary shelters for safe care that met C-19 health standards (Department of DSD, 2020a). Further, children who were in safe care or in child and youth care centres at the start of lockdown were not allowed to be released. The same applied to those in substance abuse centres and shelters for victims of violence, including GBV (Department of DSD, 2020a). A social worker’s report was deemed sufficient authorisation for admission to treatment centres and half-way houses (Department of DSD, 2020a). |

||

|

Attention to children’s psychological needs: The delivery of care services and social relief of distress services for children were declared essential services (Department of COGTA, 2020b). Other essential services that were allowed by the DSD included counselling, services supporting victims of GBV, and care and relief services (Department of COGTA, 2020g). During strict lockdown, psychosocial services were initially restricted to those infected or affected by C-19 (Department of DSD, 2020a). Later in strict lockdown, it was permissible to refer survivors of GBV for psychosocial support by other service providers, including civil society organisations (Department of DSD, 2020c). Psychosocial support services, including screening and referral for substance abuse, were also extended to the homeless (including children) (Department of DSD, 2020c). |

|||

| Extraordinary Social Support Measures |

|

Protection of physical health and children’s basic need for shelter: Landlords were not allowed to evict any person from any place of residence (Department of COGTA, 2020f). Although courts were mandated to grant an order for eviction, the order had to be stayed and suspended until the last day of strict lockdown (Department of COGTA, 2020g). Also, temporary shelters and sites of self-isolation/quarantine for homeless people were identified, including children who were homeless (Department of COGTA, 2020g). These temporary sites for quarantine and for self-isolation had to comply with health protocols. | |

|

Protection of physical health and children’s basic need for food: During strict lockdown the preparation and distribution of food and related items to eligible families, which normally occurred at community nutrition development centres and drop-in-centres, were halted. No gathering or sit-down meals were allowed at these sites (Department of DSD, 2020a). Instead, the food had to be delivered through a knock and drop (i.e., door-to-door delivery) system. |

Potential for food insecurity: Of the estimated two million food parcels needed per month, only 788 000 parcels were distributed in the month of May (Seekings, 2020). |

|

|

Recognition of children’s basic needs and the role of financial security in addressing those needs: Payments of social grants continued during lockdown and recipients could collect their funds in person (Department of COGTA, 2020b). Further, C-19 concessions prevented the lapsing of social grants which had not been claimed for three consecutive months (Department of DSD, 2020c). Temporary disability grants, care dependency and foster grants that lapsed between February and June 2020 were extended until the end of October 2020 (Department of DSD, 2020c) The Minister of DSD also directed a modest increase of R250 (approximately USD$15) for existing disability, care dependency, and foster care grants from May 2020 to October 2020. For May 2020, a modest increase of R300 (approximately USD$18) was added to the child support grant. This was subsequently replaced by a C-19 social relief of distress for caregivers grant for the period June to October 2020. The value of the latter grant is R500 (approximately USD$30) per month per child support grant caregiver, and not per child (Department of DSD, 2020c). Initially all applications for social relief of distress were required to be made in person. However, these regulations were relaxed to allow telephonic applications for new social relief of distress grants (Department of DSD, 2020a). |

4.1. Limiting the Spread of C-19 and Championing Physical Health

The regulations prioritised the maintenance of physical health. This was done via four key mechanisms: restriction of movement; access to essential services and goods; children exempted from court appearances; and public health campaigns (see Table 2 for detail). Ostensibly, each of these mechanisms protected children from bodily harm in the form of C-19 symptoms and related health complications. Paradoxically, for children in crowded households (a typical South African phenomenon; Naidu, 2020) and in institutional

care, in-person interaction within the household or institution might be as threatening to physical health as other in-person interaction. Further, the focus on safeguarding children’s protection from C-19 by imposing significant restrictions on their movement, obstructed children’s access to their extended family, schools, community-based recreation facilities and faith-based communities. School closure meant 9 million children’s access to school-based feeding schemes was obstructed (Mphahlele, 2020). Likewise, unless they had recourse to virtual education opportunities, children’s access to formal education was halted (Wolfson Vorster, 2020). In instances where children were locked down with abusive others, restricted movement likely heightened children’s vulnerability to abuse.

4.2. Continued Legal and Statutory Protection of Children at Risk for Abuse

The regulations pertaining to strict lockdown acknowledged children’s rights to protection from physical, sexual or psychological abuse (see Table 2 for detail). This was facilitated by the judiciary being advised to prioritise family law matters and cases involving children, continued services by the master of the high court, as well reports by social workers being used to authorise child protection services (Department of Justice and Correctional Services, 2020a, 2020b). Whilst these regulations and directives are useful, they do not guarantee that children will be protected, particularly in instances of children being locked down with abusive others.

4.3. Extraordinary Social Support Measures

Various measures were put in place to compensate for the socioeconomic impacts of C-19 and/or for socioeconomic risks that might be more problematic in the face of C-19. As detailed in Table 2, these included protected and temporary housing, food security via food delivery, and fiscal supports via grant extensions and increments and other financial relief measures. Although the grant increments were very modest, they signal government’s awareness that C-19 challenges exacerbated the socioeconomic disadvantage that was already rife in South Africa, prior to lockdown (Spaull et al., 2020). Whilst neglect is not unique to contexts of socioeconomic disadvantage, resource constraints typically complicate caregivers’ facilitation of their children’s physical, intellectual, social and emotional needs (Evans, 2004).

5. Discussion

The purpose of our rapid review was to identify South African legislation and secondary legislation, relevant to strict lockdown that had the potential to enable South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect during the lockdown period. The 17 pieces of secondary legislation that we reviewed suggested three pathways of potential protection, namely directives that: limit C-19 contagion and champion physical health; ensure uninterrupted protection (legal and statutory) for children at risk of abuse and neglect; and advance social protection measures available to disadvantaged households. Essentially, these pathways supported caregivers’ duty to satisfy children’s essential physical needs and protect children from deliberate physical, sexual, emotional or psychological harm or ill-treatment. As detailed later in this discussion, these legal pathways did less to support caregivers’ facilitation of children’s intellectual, emotional and social needs.

Whilst the above-mentioned pathways offer only partial protection from abuse and neglect, from a social-ecological resilience perspective they nevertheless appear to bolster some of the resources associated with the resilience of children from LMICs. Three such resources – i.e., access to basic resources, a powerful identity, and experiences of social justice were (Ungar, 2015; Ungar et al., 2007) – were implicit in each of these pathways. Access to basic resources was implied in the directives relating to the provision of housing, food, financial support, and health and wellbeing services. A powerful identity was tacit in children’s right to physical health and related directives to limit contagion and advance health. Children could also infer a powerful identity from the prioritisation of legal matters relating to their protection and welfare. The additional social support measures directed toward disadvantaged households spoke of social justice. In the South African context, which is characterised as deeply unequal (Habib, 2020) and where C-19 impacts are skewed towards households and persons that were already disadvantaged (Madonsela, 2020; Spaull et al., 2020), legislation that advances social justice in C-19 times is essential and contextually responsive.

In addition to identifying South African legislation and secondary legislation that had the potential to enable South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect during the lockdown period, we were interested in how this same legislation might constrain South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect. Ultimately, our interest was in extrapolating lessons that societies – more particularly unequal ones – could use during times of emergency to support the resilience of children who are vulnerable to abuse and neglect. To this end, we offer three propositions and draw attention to their practice and policy implications:

5.1. C-19 legislation that prioritises physical health potentiates neglect of children’s basic physical, intellectual, emotional and social needs

One of the mechanisms used to limit C-19 contagion and champion physical health, namely restricted freedom of movement, had ambivalent protective value. Clearly, this mechanism is protective of physical health. However, this mechanism meant that children’s connections to persons beyond their immediate household were truncated. Children were also prevented from attending school and participating in sporting, religious, or cultural events. In effect, legislation that prioritises physical health has the potential to be inadequately supportive of caregivers’ duty to address children’s basic intellectual, emotional, and social needs. This implies that in the face of C-19 and related harms, the physical took precedence at the expense of the intellectual, emotional, and social. Whilst it cannot be easy for a government to know how best to protect children in the face of C-19, the under-attention to children’s intellectual, emotional and social needs fits with concerns that C-19 related decisions advanced child neglect (van Bruwaene et al., 2020). This potential for neglect is probably heightened for the nine million South African children who rely on school-based feeding schemes (Mphahlele, 2020).

From a social-ecological resilience perspective, restrictions on children’s movement would necessarily constrain resources associated with the resilience of children from LMICs, such as nurturing relationships, opportunities to behave in culturally valued ways, social and/or spiritual cohesion, and a sense of control (Ungar, 2015; Ungar et al., 2007). A systematic review of the 2009—2017 studies relating to the resilience of South African children (i.e., Van Breda & Theron, 2018) found that affective support, from a range of relationships that extend beyond the immediate household, was the primary source of South African children’s resilience. Likewise, children’s connections to a network that was inclusive of adults and peers beyond the household provided them with key opportunities to develop and experience control over their life, and nurtured spiritual and cultural affiliation. Given the centrality of South African children’s social networks to their resilience, C-19 legislation’s potential to constrain social connections during strict lockdown, via restricted movement, is problematic.

It is possible to forestall the potential caveats of legislation that prioritises physical health at the expense of neglecting children’s other needs. One way to do so is to be explicit that C-19 legislation should limit children’s exposure to the virus, support children’s caregivers to satisfy children’s essential physical, intellectual, emotional and social needs, and prioritize legal, statutory and care responses to child abuse or neglect. Addressing all the aforementioned would constitute risk-relevant ways of advancing children’s resilience. It would also constitute a response that acknowledges that even in emergency times, none of a child’s needs (i.e., physical, intellectual, emotional, and social) should be prioritised at the expense of others. To this end, social work, mental health, and education professionals need to actively collaborate with government to ensure that pandemic-related legislation does not neglect children’s intellectual, emotional, and social needs. This recommendation fits well with Madonsela’s (2020) call for a “Multidisciplinary COVID-19 Advisory Forum” that could support ministries to table policy and legislation that are more likely to advance the interests of society’s most vulnerable, including children. It is possible that such a multidisciplinary team would argue that a responsive way to champion children’s resilience to neglect and abuse during emergency times would be to keep schools open. If there were empirical evidence that children’s presence in classrooms advanced the spread of C-19, then schools could remain open to serve as sites for food distribution, public education relating to C-19, and/or support service hubs (Mutch, 2014).

5.2. C-19 legislation that prioritises physical health potentiates vulnerability to abuse

In protecting children’s physical health by restricting them to their homes, vulnerability to domestic violence and other forms of abuse is inadvertently prompted in cases where children reside with the abuser (Naidu, 2020). Further, as also noted by Teo and Griffiths (2020), school staff have a legal duty to report abuse or neglect concerns to child protection authorities. The C-19-related closure of South African schools has impaired this protective mechanism, one which has frequently been used by South African children to gain statutory protection and other forms of support (Meinck et al., 2017). Given that strict lockdown meant that children with experiences of abuse by a household member were probably sequestered with the abuser, reduced access to protective resources beyond the household – like the school ecology – are particularly concerning.

Social ecologies are being encouraged to identify contextually responsive interventions that could address multiple abuse and neglect risks simultaneously (Desmond et al., 2020). Regarding C-19, this would mean conceptualising initiatives that safeguard children’s health without diminishing children’s access to protective supports. Policymakers, social work professionals, educators, mental health practitioners and other service providers are key to supporting the policy and practice uptake of the insights that result from such deliberations.

Social work professionals, educators, mental health practitioners and other service providers could also be instrumental in communicating accounts of how local families and institutions championed child protection and resilience. Whilst psychoeducation is inadequate in and of itself to prevent or manage abuse to children (Tarabulsy et al., 2008), there is protective value in sharing stories that model or illustrate resilience, including stories of how families and communities protect children against abusers (Theron et al., 2017). Creative ways of doing so could be for ‘knock-and-drop’ food initiatives to include reading material that comprises stories of South African families’ successful efforts to safeguard children from abuse and neglect during C-19, as told by families themselves and documented by teachers or other literate community members.

5.3. Inadequate operationalisation of C-19 legislation stymies its protective potential

The ‘knock-and-drop’ directive appears to have been inadequately operationalised. Anecdotal reports (e.g., Seekings, 2020) suggest that more than 50% of disadvantaged households did not benefit from the ‘knock-and-drop’ directive. Other media reports suggested that of the estimated two million food parcels needed per month, only 788 000 parcels were distributed in the month of May (Seekings, 2020). Habib (2020) attributed this failure to South Africa’s “skills-compromised civil service and its acute inability to execute decisions like, among others, … the distribution of food parcels”. Others suggested that the failure reflects C-19-related corruption (Griffiths, 2020). Across the globe, C-19-related corruption has undermined initiatives to advance health and wellbeing (Hanstad, 2020).

Evidently, well-intentioned legislation and/or secondary legislation require operational capacity for its enabling potential to be realised (De Jager, 2000; Habib 2020). Effective operationalisation of resilience-enabling directives is more likely to be realised when ministries and civil society (e.g., the private sector, non-government organisations, or community-based volunteers) collaborate. The private sector with its managerial and logistical acumen is particularly well placed to support the operationalisation of enabling legislation (Habib, 2020). Similarly, civil society must be vigilant regarding corruption and not shy away from whistleblowing and other ways of holding the corrupt accountable.

Operational capacity is also likely to be advanced when a whole social ecology takes responsibility for the resilience of its children who are vulnerable to abuse and neglect (Ungar, 2011; Ungar & Theron, 2020), perhaps even more so in times of emergency such as that of C-19 (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020). Put differently, children, their families, schools, and communities need to co-facilitate children’s access to resilience enablers. How many more South African households might have received food supplies if community- and faith-based organisations had co-facilitated the ‘knock-and-drop’ directive? Child protection practitioners and other service providers need to sensitize these and other social-ecological stakeholders to their potential to advance the operationalisation of legislation aimed at protecting children against abuse and neglect.

5.4. Limitations

We acknowledge that rapid reviews are limited, particularly with regard to selection bias as searching of the relevant literature is typically neither exhaustive nor inclusive of hand-searching or contacting of experts (Ganann et al., 2010). In following the advice of an information specialist and searching beyond the SA Government platform (i.e., also searching LexisNexus), we hoped to compensate somewhat for selection bias. Similarly, we focused only on government regulations relevant to strict lockdown. Had we, for example, included policies and/or documented strategies of non-government organisations that are engaged in child protection work (such as dedicated crisis lines and counselling services), we would probably have generated evidence-informed accounts of social-ecological capacity to champion the resilience of children vulnerable to abuse and neglect, also in times of emergency.

5.5. Conclusion

Ideally, our rapid review needs to be followed up with a comprehensive systematic review. In the interim, we are hopeful that the findings offer enough evidence that legislation specific to the C-19 pandemic has potential to champion the protection and resilience of children who are vulnerable to abuse and neglect in the face of lockdown and associated risks. Realising this potential is incumbent on lawmakers ensuring that lockdown regulations do more than protect children’s physical health and champion their rights to legal and statutory responses to abuse. In addition, legislation must ensure that children’s intellectual, emotional and social needs must be provided for, also in emergency times. In contexts where disadvantage is endemic, realising legislation’s potential to advance children’s resilience to neglect and abuse will also require that social justice be championed, not only by legislators and government but by the whole of society.

References

- Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the Republic of South African . 1996. Government Gazette. (No.17678).https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bowen G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal. 2009;9(2):27. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury‐Jones C., Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID‐19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukola G., Bhana A., Petersen I. Planning for child and adolescent mental health interventions in a rural district of South Africa: a situational analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2020;32(1):45–65. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2020.1765787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children’ Act . Vol. 28944. 2005. pp. 3–214.https://www.gov.za/documents/childrens-act (Government Gazette). (Act no. 38 of 2005) [Google Scholar]

- Childline Gauteng . 2020. Covid-19 - Report on help line data lockdown period 27th March 2020 – 30th April 2020.https://childlinegauteng.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2.-Lockdown-Level-5_CLGP_-Stats-Report_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Clark H., Coll-Seck A.M., Banerjee A., Peterson S., Dalglish S.L., Ameratunga S., Balabanova D., Bhutta Z.A., Borrazzo J., Claeson M., Doherty T., El-Jardali F., George A.S., Gichaga A., Gram L., Hipgrave D.B., Kwamie A., Meng Q., Mercer R.…Costello A. After COVID-19, a future for the world’s children? The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31481-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jager H. Auditing SA. 2000. Importance of legislation; pp. 3–4.http://www.saiga.co.za/publications-auditingsa.htm [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43107. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–11.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43107gon318.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Regulations in terms of section 27(1) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 318)). March 18. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43148. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–13.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/4314825-3cogta.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendments of regulations in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 398)). March 25. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43147. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–13.http://www.saflii.org/images/directions.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 399)). March 25. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43168. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–5.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43168reg11067gon419.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendments of regulations in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 419)). March 26. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43199. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–17.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43199rg11078-gon446.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendments of regulations issued in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 446)). April 2. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43232. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–9.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43232rg11089gon465-translations_0.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendments of regulations issued in terms section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 465)). April 16. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Co-Operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43258. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–38.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43258rg11098gon480s.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Regulations in terms of section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 480)). April 29. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Home Affairs (South Africa) Vol. 43301. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–6.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202005/43301rg11108gon518.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendment of directions in terms of regulation 10(8) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 518)). May 9. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice and Correctional Services (South Africa) Vol. 43191. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–12.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43191rg11076-gon440.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of regulation 10 under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 440)). March 31. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice and Correctional Services (South Africa) Vol. 43268. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–16.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202005/43268rg11103gon489.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of regulation 4(2) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 489)). May 4. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Labour (South Africa) Vol. 43161. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–10.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43161gen215.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directive in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 215)). March 26. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Labour (South Africa) Vol. 43216. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–6.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43216gen240.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendment of directive in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 240)). April 8. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development (South Africa) 2005. The integrated service delivery model.http://operationcompassion.co.za/images/Pdf/Legislation%20quidelines/Service%20Delivery%20Model.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development (South Africa) Vol. 43182. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–10.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43182rg11072gon430.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of regulation 10(5) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 430)). March 30. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development (South Africa) Vol. 43213. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–5.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43213rg11083gon455.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendment to directions in terms of regulation 10(8) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 455)). April 7. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development (South Africa) Vol. 43300. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–12.https://www.gov.za/documents/disaster-management-act-social-development-directives-amendment-9-may-2020-0000 (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Amendment to directions in terms of regulation 4(5) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 517)). May 9. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (South Africa) Vol. 43307. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–8.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202005/43307rg11110gon523.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of regulation 4(10)(a) of the regulations under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act. (Notice 523)). May 12. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water and Sanitation (South Africa) Vol. 43231. Government Gazette; 2020. pp. 3–11.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202004/43231gon464s.pdf (Disaster Management Act, 2002 (Act no. 57 of 2002): Directions in terms of regulation 10 (8) under section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Notice 464)). April 15. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond C., Sherr L., Cluver L. Covid-19: Accelerating recovery. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2020 doi: 10.1080/17450128.2020.1766731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G.W. The environment of childhood poverty. American psychologist. 2004;59(2):77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e625/f51c09e24052947b556790cdf3dce3c4be9c.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganann R., Ciliska D., Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implementation Science. 2010;5(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1748-5908-5-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garritty C., Gartlehner G., Kamel C., King V.J., Nussbaumer-Streit B., Stevens A., Hamel C., Affengruber L. 2020. Cochrane Rapid Reviews. Interim guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group.https://methods.cochrane.org/rapidreviews/sites/methods.cochrane.org.rapidreviews/files/public/uploads/cochrane_rr_-_guidance-23mar2020-v1.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J. Daily Maverick; 2020. Food parcels as an instrument of politics and corruption.https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-04-22-food-parcels-as-an-instrument-of-politics-and-corruption/ April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Habib A. More eyes on COVID-19: Perspectives from Political Science: Insights from the political management of COVID-19. South African Journal of Science. 2020;116(7/8) doi: 10.17159/sajs.2020/8499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanstad T. World Economic Forum; 2020. Corruption is rife in the COVID-19 era. Here’s how to fight back.https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/corruption-covid-19-how-to-fight-back/ July 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer D., Eagle G., Crawford-Browne S. Continuous traumatic stress as a mental and physical health challenge: Case studies from South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology. 2018;23(8):1038–1049. doi: 10.1177/1359105316642831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund R.G., Manica S., Manica G. 2020. Collateral issues in times of covid-19: child abuse, domestic violence and femicide. RBOL-Revista Brasileira de Odontologia Legal.https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/en/publications/collateral-issues-in-times-of-covid-19-child-abuse-domestic-viole [Google Scholar]

- Madonsela T. More eyes on COVID-19: A legal perspective: The unforeseen social impacts of regulatory interventions. South African Journal of Science. 2020;116(7/8) doi: 10.17159/sajs.2020/8527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlase Z., Ntombela S. Drop-In centres as a community response to children’s needs. South African Journal of Childhood Education. 2011;1(2):193–201. https://sajce.co.za/index.php/sajce [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S. Guilford Publications; 2014. Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S., Cicchetti D. Resilience in development: Progress and transformation. In: Cicchetti D., editor. Developmental psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2016. pp. 271–333. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S., Motti-Stefanidi F. Multisystem Resilience for Children and Youth in Disaster: Reflections in the Context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science. 2020;1(2):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinck F., Cluver L., Loening-Voysey H., Bray R., Doubt J., Casale M., Sherr L. Disclosure of physical, emotional and sexual child abuse, help-seeking and access to abuse response services in two South African Provinces. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2017;22(Suppl. 1):94–106. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1271950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhlongo N., editor. Black tax: Burden or ubuntu? Jonathan Ball Publishers; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mphahlele K. Spotlight; 2020. COVID-19: The kids are not all right.https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2020/04/17/covid-19-the-kids-are-not-all-right/ April 17. [Google Scholar]

- Mutch C. The role of schools in disaster preparedness, response and recovery: what can we learn from the literature? Pastoral Care in Education. 2014;32(1):5–22. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2014.880123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu T. The COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(5):559–561. doi: 10.1037/tra0000743. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-47568-005.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkomo G. Daily Maverick; 2020. SA needs to save its future – the children.https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-06-09-sa-needs-to-save-its-future-the-children/#gsc.tab=0 June 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. Sage; 2009. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Seekings J. Daily Maverick; 2020. Feeding poor people: The national government has failed.https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-06-02-feeding-poor-people-the-national-government-has-failed/#gsc.tab=0 June 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shung-King M., Lake L., Sanders D., Hendricks M., editors. South African Child Gauge 2019. Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town; 2019. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/cg-2019-child-and-adolescent-health [Google Scholar]

- Simba J., Sinha I., Mburugu P., Agweyu A., Emadau C., Akech S., Kithuci R., Oyiengo L., English M. Is the effect of COVID‐19 on children underestimated in low‐and middle‐income countries? Acta Paediatrica. 2020 doi: 10.1111/apa.15419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Government . 2020. Minister Bheki Cele: Visit to KwaZulu-Natal to assess adherence to the Coronavirus COVID-19 lockdown regulations.https://www.gov.za/speeches/minister-bheki-cele-visit-kwazulu-natal-assess-adherence-coronavirus-covid-19-lockdown April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Spaull N., Ardigton C., Bassier I., Bhorat H., Bridgman G., Brophy T., Budlender J., Burger R., Burger R., Carel D., Casale D., Christian C., Daniels R., Ingle K., Jain R., Kerr A., Köhler T., Makaluza N., Maughan-Brown B.…Zuze L. 2020. NIDS-CRAM Wave 1 Synthesis Report: Overview and Findings.https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Spaull-et-al.-NIDS-CRAM-Wave-1-Synthesis-Report-Overview-and-Findings-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey H.L. The second step in data analysis: Coding qualitative research data. Journal of Social Health and Diabetes. 2015;3(1):7–10. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-second-step-in-data-analysis%3A-Coding-research-Stuckey/5295130cc0c9775bb8591fb26a798b7a8ccad0c1 [Google Scholar]

- Tarabulsy G.M., St‐Laurent D., Cyr C., Pascuzzo K., Moss E., Bernier A., Dubois‐Comtois K. Attachment‐based intervention for maltreating families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(3):322–332. doi: 10.1037/a0014070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo S.S., Griffiths G. Child protection in the time of COVID‐19. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jpc.14916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theron L.C., Cockroft K., Wood L. The resilience-enabling value of African folktales: The Read-Me-to-Resilience Intervention. School Psychology International. 2017;38(5):491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Practitioner review: Diagnosing childhood resilience – a systemic approach to the diagnosis of adaptation in adverse social and physical ecologies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(1):4–17. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M., Brown M., Liebenberg L., Othman R., Kwong W.M., Armstrong M., Gilgun J. Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence. 2007;42(166):287–310. https://is.muni.cz/el/1441/jaro2015/SP4MP_ETPP/um/53040956/UNIQUE_PATHWAYS_TO_RESILIENCE_ACROSS_CULTURES.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M., Theron L. Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):441–448. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breda A.D., Theron L.C. A critical review of South African child and youth resilience studies, 2009-2017. Child and Youth Services Review. 2018;91:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Bruwaene L., Mustafa F., Cloete J., Goga A., Green R.J. What are we doing to the children of South Africa under the guise of COVID-19 lockdown? SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2020;110(7):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lancker W., Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e243–e244. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C.L., Artz L., Leoschut L., Kassanjee R., Burton P. Sexual violence against children in South Africa: A nationally representative cross-sectional study of prevalence and correlates. The Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(4):e460–e468. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills G., Patel L., Van der Berg S., Mpeta B. Working Paper Series NIDS-CRAM Wave 1. 2020. Household resource flows and food poverty during South Africa’s lockdown: Short-term policy implications for three channels of social protection.https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Wills-household-resource-flows-and-food-poverty-during-South-Africa%E2%80%99s-lockdown-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson Vorster R. Daily Maverick; 2020. The challenges of hunger and education for SA’S children.https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-05-05-part-one-the-challenges-of-hunger-and-education/#gsc.tab=0 May 5. [Google Scholar]