Abstract

Background

Current guidelines for perioperative management of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) are mainly based on extrapolated evidence or expert opinion. We aimed to systematically investigate how COVID-19 affects perioperative management and clinical outcomes, to develop evidence-based guidelines.

Methods

First, we conducted a rapid literature review in EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (January 1 to July 1, 2020), using a predefined protocol. Second, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 166 women undergoing Caesarean section at Tongji Hospital, Wuhan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Demographic, imaging, laboratory, and clinical data were obtained from electronic medical records.

Results

The review identified 26 studies, mainly case reports/series. One large cohort reported greater mortality in elective surgery patients diagnosed after, rather than before surgery. Higher 30 day mortality was associated with emergency surgery, major surgery, poorer preoperative condition and surgery for malignancy. Regional anaesthesia was favoured in most studies and personal protective equipment (PPE) was generally used by healthcare workers (HCWs), but its use was poorly described for patients. In the retrospective cohort study, duration of surgery, oxygen therapy and hospital stay were longer in suspected or confirmed patients than negative patients, but there were no differences in neonatal outcomes. None of the 262 participating HCWs was infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) when using level 3 PPE perioperatively.

Conclusions

When COVID-19 is suspected, testing should be considered before non-urgent surgery. Until further evidence is available, HCWs should use level 3 PPE perioperatively for suspected or confirmed patients, but research is needed on its timing and specifications. Further research must examine longer-term outcomes.

Clinical trial registration

CRD42020182891 (PROSPERO).

Keywords: Caesarean delivery, COVID-19, perioperative outcome, personal protective equipment, SARS-CoV-2 testing

Editor's key points.

-

•

The impact of COVID-19 on the perioperative management and clinical outcomes were systematically investigated to develop evidence-based guidelines for management.

-

•

A rapid review of 26 studies, mainly case reports/series, found greater mortality in elective surgery patients diagnosed after, rather than before surgery.

-

•

Higher 30 day mortality was associated with emergency surgery, major surgery, poorer preoperative condition and surgery for malignancy.

-

•

A retrospective cohort study found that duration of surgery, oxygen therapy, and hospital stay were longer in suspected or confirmed patients with COVID-19 than in negative patients, with no differences in neonatal outcomes from Caesarean delivery.

-

•

None of the participating HCWs was infected with SARS-CoV-2 when using level 3 PPE perioperatively.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), resulting from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, has become a global pandemic since it was first described in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.1 More than 19 million cases and more than 728 000 deaths have been reported worldwide as of August 2020.2 In the UK alone, 310 829 cases have been reported with 46 574 deaths, and in China there have been 89 270 cases and 4693 deaths.2 In response to this health crisis, guidelines have been published on the clinical management of patients undergoing surgery to prevent transmission to healthcare workers (HCWs) and adverse outcomes in patients.3 , 4 These are mainly based on pre-existing practices rather than on data from patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, and little is known about how perioperative techniques affect transmission rates and outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

A rapid review of clinical guidelines published early in the COVID-19 pandemic concluded that their overall quality was low and their focus should be on evidence-based recommendations, rather than consensus.5 This study therefore had two objectives: (1) to conduct a rapid review of studies and case reports examining the management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 undergoing surgery, and subsequent morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay, use of intensive care, respiratory, and pain support, and COVID-19 transmission to HCWs; (2) and to examine perioperative approaches and outcomes in a series of Caesarean section operations undertaken in Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

Rapid review

Our review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.6 Owing to the fast-evolving nature of COVID-19 and the need to produce clinical evidence for making recommendations on patient care that are readily available to HCWs in a timely manner, we adopted a rapid approach to the review.7 This involved a streamlined protocol whereby article identification, appraisal, and data extraction were shared between two reviewers, with some overlap for quality control, instead of complete independent duplication. Details of the protocol were registered on PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews (ID: CRD42020182891) and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=182891.

Eligibility criteria

Population

The study cohort consisted of any patient undergoing surgery who had confirmed or suspected COVID-19 at the time of surgery.

Intervention

Any form of surgery and perioperative management undertaken whilst the participant was suspected or confirmed as having COVID-19, except where the procedure was conducted to treat COVID-19. Any studies not reporting details of patient management at any time during the perioperative period (defined as 24 h before and after surgery) were excluded from the review. Studies were also excluded if they included patients who did not undergo surgery, and where it was not possible to identify them separately from surgical patients.

Comparator

Where relevant, patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 who were not subject to perioperative interventions.

Outcomes

The outcomes were patient, HCW, and neonatal postoperative outcomes, where relevant.

Study type

Observational studies including cross-sectional, case-control and cohort designs, and case series or case reports and RCTs were included. Because the database search, article screening, and data extraction processes were conducted by UK-based authors, only English language articles were considered to avoid misinterpretation of the data. Unpublished studies, conference abstracts, and research theses or dissertations were excluded (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies in the review. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 who have undergone surgery or HCWs who have treated surgical patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 | 1. Unpublished studies, conference abstracts, and research theses or dissertations |

| 2. Observational studies including case reports, case series, case-control, cross-sectional, cohort, and randomised control trials. | 2. Studies that do not provide any perioperative management details (defined as the time from when the decision to operate was made to 24 h after surgery) |

| 3. Written in English | 3. Studies where the patients are not suspected of or confirmed as having COVID-19 during surgery |

| 4. Studies that do not report patients that have undergone surgery separately from those that have not undergone surgery | |

| 5. Studies reporting surgery only conducted to treat COVID-19 | |

| 6. Studies8,9 that included participants that have also been included in the cohort study of this paper |

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and Web of Science for original articles, reported in English. Databases were searched from January 1, 2020, with initial search to May 4, 2020; the search was updated on July 1, 2020. As the purpose of this study is to provide both clinical evidence and recommendations for further research in a timely manner, it was decided to exclude studies with a sample size of <15 in the re-run of search terms (May 4–July 1, 2020). Such studies are likely to be dominated by lower quality case reports, which would not contribute substantially to the overall evidence presented in this study. Reference sections of included studies were also checked for relevant studies.

The search terms used for all five databases included words related to COVID-19 (the population), surgical interventions, and perioperative management (the interventions). Comparator, outcomes, and study type search terms were not used. Where available, the study year filter was set to 2020 (Supplementary Table S1).

After retrieving articles from the databases, non-English language items and duplicates were removed. HLH and LAC then independently screened the titles and abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify relevant studies. The remaining articles then went through full-text review (HLH and LAC), noting reasons for all exclusions. Any differences in opinion were settled by discussion between the reviewers and, where necessary, the wider research team.

Data extraction

A pro forma spreadsheet was constructed, and data extraction was conducted independently by HLH and AC, who reviewed an equal number of studies with a six-study overlap for quality control. Any differences in data extraction for the overlapped studies were resolved between HLH and AC. Owing to the rapid nature of the review, study authors were not contacted to resolve missing data or identify further studies.

The following data items were extracted:

-

1.

Study details – authors, journal, date of publication, country/countries where the study took place, sample size, and study design.

-

2.

Patient characteristics – age, gender, BMI/weight, comorbidities and method of diagnosing or suspecting COVID-19.

-

3.

Surgical details – type, schedule, indications, duration, and other relevant details.

-

4.

Perioperative management – HCW use and level of personal protective equipment (PPE), patient use of PPE, patient time between symptoms and surgery, type of anaesthesia (e.g. general/regional), analgesics used, pain assessment, vasopressors used, blood loss, and any other relevant details.

-

5.

Postoperative outcomes – HCW COVID-19 status, patient discharge status, length of hospital stay, use of ICU or high dependency unit (HDU), level of respiratory support, use of analgesia, mortality and, where relevant to the study, neonatal COVID-19 status, Apgar score, mortality, discharge status, and any other relevant reported details

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

The quality of reporting of all included studies was evaluated by HLH and AC according to the CAse REport (CARE) guidelines10 for case reports/series or the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines11 for cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies. A quality score12 , 13 was calculated for each article based on a checklist of 36 items for CARE (Supplementary Table S2) and 32–34 items for STROBE (Supplementary Table S3), depending on the type of observational study. The presence of an item scored 1, absence scored 0, and the total was calculated. A percentage of the maximum possible score was also calculated and ‘high quality’ was defined as any study achieving a score of 80% or greater.12 , 14 ‘Low quality’ was defined as any study with a score of <80%. Higher scores indicate studies with reporting of higher quality. Disagreements were resolved via discussion between the two reviewers.

Summary measures

For case reports and series with sample size ≤5, numeric values are reported individually. Otherwise, summary statistics are presented (e.g. median, mean, range, inter-quartile range [IQR], or standard deviation [sd]) as reported in original papers. Qualitative variables are reported as counts. A synthesis of the extracted data was constructed, structured around the type of surgery performed, surgical practices, population demographic and clinical characteristics, and type of outcome. Recommendations for the perioperative management of patients with COVID-19 were developed from the synthesised evidence, and tables were constructed to aid the presentation of the extracted data and quality assessment of each article.

Cohort study

Study design and data sources and ethics

This single-centre, retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China (TJ-IRB20200421). The requirement for informed consent from participants was waived under the regulations of the Institutional Review Board. Data, including demographic, clinical, imaging, laboratory, perioperative management, and maternal and fetal outcomes, were extracted from the electronic database of medical records at Tongji Hospital, and anonymised for analyses.

Data from all parturients who underwent Caesarean section (including emergency surgery) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan were included. To ensure completeness of reported data, we included all patients who had undergone Caesarean section in the defined period; some of these data have been reported previously by other groups.8 , 9

COVID-19 case definitions were based on the National Health Commission of China's diagnostic criteria (7th edition) (Table 2 ).15 A confirmed case of COVID-19 was defined as a suspected case with a positive result of real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) assay of respiratory tract specimen or of serum-specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. If the results of two RT–PCR tests taken at least 24 h apart, and serum-specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 detected at least 7 days after the onset of the disease, were negative in a suspected case, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was excluded. All patients were tested with RT–PCR or antibodies or chest CT when possible. If COVID-19 was suspected or confirmed, follow-up tests were performed after surgery.

Table 2.

National Health Commission of China's diagnostic criteria for suspected cases of COVID-19 (7th edition).

| A case that has any one condition of epidemiological history and any two clinical manifestations is considered as a suspected case. If there is no clear epidemiological history, then suspected cases need all three clinical manifestations. |

| A. Epidemiological history |

| 1. History of residence or travel in Wuhan and its surrounding areas, or in other communities with cases reported within 2 weeks before the onset of the disease; |

| 2. History of contact with SARS-CoV-2-infected patients (positive results of nucleic acid test) within 2 weeks before the onset of the disease; |

| 3. History of contact with patients with fever, respiratory symptoms, or both who are from Wuhan and its surrounding areas, or from other communities with cases reported within 2 weeks before the onset of the disease; |

| 4. Cluster of infections: two or more cases with fever, respiratory symptoms, or both occurred in a small area such as home, office, and school class within 2 weeks before the onset of the disease. |

| B. Clinical manifestations |

| 1. Fever, respiratory symptoms, or both. |

| 2. Imaging features of COVID-19: multiple patchy shadows and interstitial changes in the early phase, and then multiple ground-glass opacities, infiltration shadows or even consolidation in advanced phase. |

| 3. Normal or decreased leucocyte and lymphocyte count in the early stage of disease. |

Perioperative management

Before entering the operating room, triage was performed by obstetricians and anaesthetists, including a medical history review, brief physical examination, and review of blood test results, CT, and tests for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid or antibodies. Because individuals might be infected with SARS-CoV-2 but be asymptomatic, all patients were placed in an isolation holding area and transferred to a dedicated negative pressure operating room with an anteroom (buffer area). Patients wore surgical or N95 masks throughout the process. After the patient entered the operating room, continuous electrocardiography, regular noninvasive blood pressure, and peripheral pulse oximetry were monitored. Spinal anaesthesia or combined spinal–epidural anaesthesia was the primary technique. General anaesthesia with tracheal intubation was an option under certain circumstances such as contraindications of spinal anaesthesia, maternal or fetal emergencies, or failed spinal anaesthesia. During tracheal intubation, surgeons and nurses remained in the operating room to ensure that surgery started as soon as possible after induction. The neonatal team was notified before delivery in order to attend and make any necessary preparations. After delivery, newborns were cleaned immediately to remove blood clots, meconium, and amniotic fluid, and were then placed under a radiant warmer in a cordoned-off area in the operating room. Apgar scores of newborns were assessed at 1 and 5 min. For patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, their newborns were transferred to a neonatology isolation room shortly after delivery. SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid tests were then carried out as soon as possible in all newborns. Maternal contact was not allowed.

One day after surgery, full blood count and coagulation tests were performed in parturients. If COVID-19 was suspected or confirmed, chest CT, SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid, or antibodies were tested again. Body temperature or any other symptoms associated with COVID-19 were recorded daily by nurses throughout the hospital stay. According to parturients' clinical condition, supplemental oxygen was delivered via nasal cannula or mask to maintain an SpO2 of 95% or above. Other methods of noninvasive or invasive ventilation were considered if necessary. Diclofenac, dezocine, or both was given, as requested by the parturients, to relieve postoperative pain.

Perioperative protection and postoperative evaluation of HCWs

Self-protection precautions were strictly followed by all participating HCWs. Level 3 PPE, including N95 mask, fluid-resistant gown, goggles, face shield, disposable hair cover, head covering, two layers of gloves, and fluid-resistant shoe covers, was used by all HCWs involved. PPE was donned before entering the operating room and was doffed after exiting operating room in the buffer area. All HCWs involved had a 24 h duty shift every 1–2 weeks. They were required to report any COVID-19-related symptoms such as fever, cough, or fatigue. At the beginning of April 2020, all HCWs were required to have a SARS-CoV-2 antibody test, a test for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid by nasopharyngeal swab, and a chest CT scan.

Statistical analysis

Suspected or confirmed cases were categorised together and compared with negative cases. Maternal outcomes including duration of operation, oxygen therapy, hospital stay, and fetal outcomes such as Apgar scores were compared between groups. Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR). These data failed the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality, and significance was calculated using Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables are expressed as number (%) and analysed using χ2 tests. SPSS 21.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Rapid review

Study selection

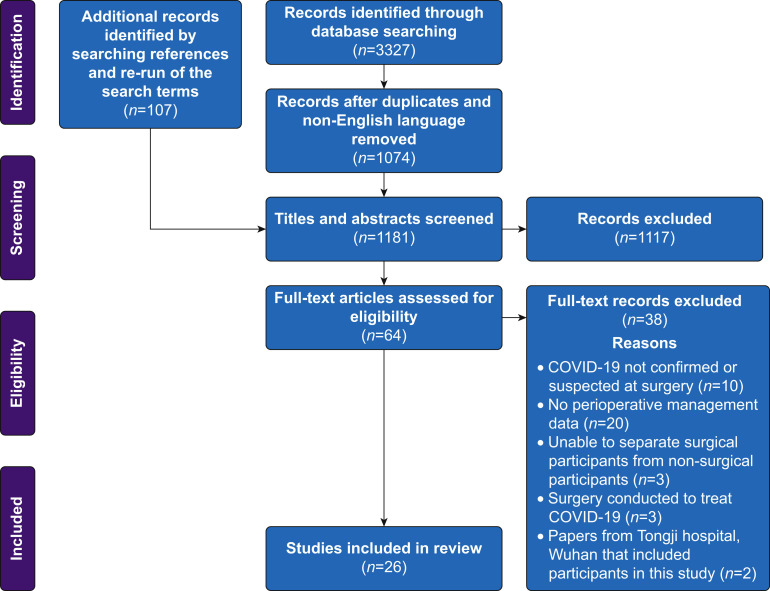

The workflow for identifying and screening articles is provided in Figure 1 . The initial literature searches yielded 3227 papers. The re-run of the search yielded a further 107 articles. After removal of duplicates, non-English language papers, and title and abstract screening, 64 articles remained for full-text review. Articles identified during the re-run of search terms (from May 4 to July 1, 2020) that were excluded on the basis of having a sample size ≤15 are shown in Supplementary Table S4. A full list of the 38 articles excluded on full-text review, with reasons, is provided in Supplementary Table S5. We therefore identified 26 articles for inclusion in this review.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41

Fig 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the identification and screening of articles for inclusion in the review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of each included study are summarised in Table 3 . There were no RCTs, and 22 of the papers were lower quality case reports or case series.16 , 17 , 19 , 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 , 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 , 41 The remaining four were observational studies, of which two were cohort studies,20 , 33 one was a small cross-sectional study (n=7),18 and one was a retrospective four-centre clinical study (n=37).40 The cross-sectional study was published without peer review.18 Only one study met our definition of ‘high quality’.33

Table 3.

Characteristics and quality assessment of the studies included in this review. CARE, CAse REport; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RT–PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; STROBE, Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology.

| Authors | Date of publication | Country | Study design | Surgery | Method of suspecting/diagnosing COVID-19 in patient(s) | Sample size | STROBE/CARE score (%)∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzamora and colleagues16 | 18/04/2020 | Peru | Case report | Caesarean section | Nasopharyngeal RT–PCR, CT | 1 | 22 (61) |

| Catellani and colleagues17 | 30/04/2020 | Italy | Case series | Orthopaedic | Oropharyngeal RT–PCR, thoracic CT | 16 (13 underwent surgery) | 21 (58) |

| Chehrassan and colleagues18 | 14/04/2020 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 5 Orthopaedic, 1 abdominal | High-resolution CT | 7 (6 underwent surgery) | 12 (37) |

| Chen and colleagues19 | 16/03/2020 | China | Case series | Caesarean section | Nasal RT–PCR, chest CT | 17 | 22 (61) |

| Doglietto and colleagues20 | 12/06/2020 | Italy | Cohort | 22 Orthopaedic, 7 vascular, 6 neurological, 5 general, 1 thoracic | Nasopharyngeal RT–PCR, chest CT, chest radiography | 41 | 26 (76) |

| Dong and colleagues21 | 26/03/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Nasopharyngeal RT–PCR, chest CT | 1 | 18 (50) |

| Du and colleagues22 | 19/05/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Pharyngeal RT–PCR, CT | 1 | 18 (50) |

| Ferrazzi and colleagues23 | 27/04/2020 | Italy | Case series | Caesarean section | Throat swab RT–PCR (confirmative chest X-ray) | 42 (18 underwent surgery) | 19 (52) |

| Firstenberg and colleagues24 | 19/04/2020 | USA | Case report | Cardiothoracic | CT (preoperatively), RT–PCR (postoperatively, not explicitly stated) | 1 | 25 (69) |

| Gao and colleagues25 | 18/04/2020 | China | Case series | Abdominal | Chest CT and radiography (preoperatively), oropharyngeal RT–PCR (postoperatively) | 4 | 17 (47) |

| Gidlöf and colleagues26 | 06/04/2020 | Sweden | Case report | Caesarean section | Nasopharyngeal RNA test | 1 | 15 (41) |

| He and colleagues27 | 21/03/2020 | China | Case series | Cardiothoracic | CT and clinical symptoms | 4 | 13 (36) |

| Lee and colleagues28 | 31/03/2020 | Republic of Korea | Case report | Caesarean section | Sputum and nasopharyngeal RT–PCR, chest CT, and chest radiography | 1 | 21 (58) |

| Li and colleagues29 | 2020, exact data unclear | China | Case report | Caesarean section | RT–PCR (not explicitly stated) of sputum sample | 1 | 20 (55) |

| Lu and colleagues30 | 24/04/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Throat swab RT–PCR, chest CT | 1 | 24 (66) |

| Lyra and colleagues31 | 20/04/2020 | Portugal | Case report | Caesarean section | Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal RT–PCR | 1 | 18 (50) |

| Mi and colleagues32 | 09/06/2020 | China | Case series | Not reported | Not reported | 28 | 7 (19) |

| Nepogodiev and colleagues33 | 29/05/2020 | 24 countries (led by UK) | Cohort | 373 gastrointestinal and general, 302 orthopaedic, 86 cardiothoracic, 62 hepatobiliary, 51 obstetric, 45 vascular, 40 head and neck, 39 neurosurgery, 37 urological, 57 other and 36 missing | Nasal swab or bronchoalveolar lavage RT–PCR, relevant clinical symptoms (including cough, fever, or myalgia), or radiological findings (thorax CT) | 1128 | 33 (97) |

| Song and colleagues34 | 26/02/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Throat and faecal RT–PCR, chest CT | 1 | 22 (61) |

| Sun and colleagues35 | 28/04/2020 | China | Case series | Caesarean section | Pharyngeal, laryngeal, throat and tracheal tube tip RT–PCR | 3 | 18 (50) |

| Wang and colleagues36 | 28/02/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Throat swab RT–PCR, chest CT | 1 | 21 (58) |

| Xia and colleagues37 | 17/03/2020 | China | Case report | Caesarean section | Oropharyngeal RT–PCR, chest CT | 1 | 14 (38) |

| Zeng and colleagues38 | 26/03/2020 | China | Case series | Caesarean section | Symptoms, chest CT scan, and RT–PCR | 6 | 9 (25) |

| Zhang and colleagues39 | 08/04/2020 | China | Case series | Caesarean section | Suspected: abnormal CT (ground-glass opacity and bilateral patchy shadowing), coupled with typical clinical symptoms (fever, cough, headache, sore throat, shortness of breath), sputum. Confirmed: nasopharyngeal RT–PCR | 4 | 17 (47) |

| Zhao and colleagues40 | 18/03/2020 | China | Clinical study | 10 abdominal, 2 cardiovascular, 6 orthopaedic, 11 gynaecology and obstetrics, 2 neurosurgery and 6 other | Laboratory, imaging (CT) and clinical findings (body temperature) | 37 | 10 (29) |

| Zhong and colleagues41 | 28/03/2020 | China | Case series | 45 Caesarean section, 4 orthopaedic | Radiology for inclusion in study, confirmation through throat swab RT–PCR | 49 | 26 (72) |

Details of the STROBE and CARE scores are provided in the Methods section.

Sixteen of the studies were conducted in China, where the virus was first reported.19 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Three were conducted in Italy,18 whereas one study was conducted in each of Iran,18 Peru,16 Portugal,31 South Korea,28 Sweden,26 and USA.24 One paper was a multi-centre cohort study conducted in 24 different countries, led by a centre in the UK.33

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

CARE Quality assessment scores ranged from 7 to 26 (of 36) for the case reports and case series STROBE scores ranged from 10 to 33 (of 34) for the observational studies (Table 3). A full breakdown of scores for each study is provided in Supplementary Tables S6 and S7.

Owing to the limited sample sizes of the included studies, the heterogeneity in surgeries performed and approaches to perioperative management, and the inherent lack of comparative groups in the case reports, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis to estimate effect sizes and we could not quantitatively assess risk of bias across studies.

COVID-19 status

Diagnosis of COVID-19 and timing of diagnosis (relative to surgical procedure) were variably reported, applying a range of diagnostic criteria. Suspected COVID-19 was usually based on relevant symptoms. All of the studies used RT–PCR for SARS-CoV-2 RNA or chest CT for diagnosis (although one study did not report diagnostic criteria32). Four studies used RT–PCR only,26 , 29 , 31 , 35 two studies used CT only,18 , 27 and 19 studies used a combination of both.16 , 17 , 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 , 28 , 30 , 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 In some places RT–PCR was not available.33 Specimens used for RT–PCR included nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, sputum, tracheal tube tip, and bronchoalveolar lavage. Although not fully reported in all studies, RT–PCR tests were negative in some cases despite CT findings (and in some cases, symptoms) consistent with COVID-19.25 , 41

Perioperative management

The total number of surgical procedures reported in the included studies was 1370, including gastrointestinal/abdominal (n=393),18 , 20 , 25 , 33 , 40 orthopaedic (n=352),17 , 18 , 20 , 33 , 40 , 41 obstetric/gynaecologic (n=166),16 , 19 , 21, 22, 23 , 26 , 28, 29, 30, 31 , 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 cardiothoracic/vascular (n=146),20 , 24 , 27 , 33 , 40 hepatobiliary (n=62),33 neurosurgical (n=47),20 , 33 , 40 head and neck (n=40),33 urologic (n=37),33 other surgeries (n=63),33 , 40 and missing details (n=64).32 , 33 The schedule of surgeries, where reported, were classed as elective (n=316), and urgent or emergency (n=949). At least 153/166 of the obstetric/gynaecologic surgeries were Caesarean sections. Most of the other surgeries were for cancer or trauma (Supplementary Table S8).

Most studies reported surgical procedures performed under neuraxial anaesthesia (Table 4 ). Ten reported procedures (53 Caesarean sections, 17 orthopaedic) using neuraxial anaesthesia only17 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 41 and three reported procedures (five aortic dissections and one Caesarean section) using general anaesthesia only,16 , 24 , 27 whereas six reported a mix of surgeries performed using either general or neuraxial anaesthesia.19 , 20 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 40 When reported, spinal, epidural, or a combination of the two methods were used. Exact details of which anaesthetics and analgesics were used were only reported in five of the 26 studies.19 , 28 , 34 , 37 , 41 It is not clear whether there were any changes from standard anaesthetic/analgesic practice because of COVID-19.

Table 4.

Perioperative management details of patients in the rapid review. BSL, biosafety level; HCW, health care worker; PPE, personal protective equipment; sd, standard deviation.

| Study | Type of surgery | HCW use of PPE | HCW level of PPE | Patient use of PPE | Patient level of PPE | Type of anaesthesia | Pain assessment | Analgesics used | Vasopressors used | Blood loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzamora and colleagues16 | 1 Caesarean section | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 1 General anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not Reported |

| Catellani and colleagues17 | 13 Orthopaedic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 13 spinal anaesthesia with nerve block | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported, managed with transfusion |

| Chehrassan and colleagues18 | 5 Orthopaedic, 1 abdominal | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Chen and colleagues19 | 17 Caesarean sections | Yes | BSL-3 (N95 masks, goggles, protective suits, disposable medical caps, and medical rubber gloves) | Yes | 17 Regular surgical masks | 14 epidural and 3 general anaesthesia | VAS | Epidural anaesthesia – lidocaine 2%, ropivacaine 0.75% General anaesthesia –sevoflurane 8%, lidocaine 2%, remifentanil, succinylcholine, sufentanil, propofol |

Not reported | Epidural anaesthesia - Mean: 307 ml (sd=92), General anaesthesia – Mean: 300 ml (sd=100) |

| Doglietto and colleagues20 | 22 Orthopaedic, 7 vascular, 6 neurological, 5 general, 1 thoracic | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 21 local and 20 general anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dong and colleagues21 | 1 Caesarean section | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | N95 mask | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Du and colleagues22 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Level 3 | Yes | N95 mask | Combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ferrazzi and colleagues23 | 18 Caesarean sections | Yes | More strict PPE than just surgical masks | Yes | 18 More strict PPE than just surgical masks | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Firstenberg and colleagues24 | 1 Cardiothoracic | Yes | N95 masks with face shield or goggles (in addition to surgical gown and gloves) | Not reported | Not reported | General anaesthesia implied from tracheal tubing (but not explicitly stated) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gao and colleagues25 | 4 Abdominal | Yes | Full PPE (Level 3) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Gidlöf and colleagues26 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Spinal anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ∼200ml |

| He and colleagues27 | 4 Cardiothoracic | Yes | Level 3 | Not reported | Not reported | General anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lee and colleagues28 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | N95 mask, surgical cap, double gown, double gloves, shoe covers, powered air-purifying respirator | Yes | N95 mask | Spinal anaesthesia | Not reported | Marcaine 0.5%, fentanyl (injected intrathecally) | Phenylephrine | 400 cc |

| Li and colleagues29 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Protective suit | Yes | Protective suit | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lu and colleagues30 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Level 3 (gown, N95 mask, eye protection, and three-layer latex gloves) | Not reported | Not reported | Combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ∼200ml |

| Lyra and colleagues31 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Level 2 | Not reported | Not reported | Regional anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mi and colleagues32 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 21 Spinal, 3 local and 4 general anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Nepogodiev and colleagues33 | 373 gastrointestinal and general, 302 orthopaedic, 86 cardiothoracic, 62 hepatobiliary, 51 obstetric, 45 vascular, 40 head and neck, 39 neurosurgery, 37 urological, 57 other, and 36 missing | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 30 day mortality – 15 local, 32 regional, 217 general anaesthesia; pulmonary complications – 25 local, 73 regional, 464 general anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Song and colleagues34 | 1 Caesarean section | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | Not reported | Combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia | Not reported | Tramadol | Yes | 300ml |

| Sun and colleagues35 | 3 Caesarean sections | Yes | Full (N95 mask, eye goggles, face shield, top-to-bottom tight-fitting gown) | Yes | 1 Not reported, 2 face masks | 1 General and 2 spinal anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Wang and colleagues36 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Level 3 | Not reported | Not reported | Combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 200ml |

| Xia and colleagues37 | 1 Caesarean section | Yes | Third-level measure – N95 mask (fit tested), disposable surgical cap, medical goggles or positive-pressure headgear, disposable protective clothing, disposable gloves, disposable shoe covers | Not reported | Not reported | Combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia | Not reported | 1% ropivacaine | Intravenous methoxamine | ∼300ml |

| Zeng and colleagues38 | 6 Caesarean sections | Yes | Protective suits and double masks | Yes | 6 masks | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zhang and colleagues39 | 4 Caesarean sections | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | 1 Level 2, 3 level 3 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zhao and colleagues40 | 10 abdominal, 2 cardiovascular, 6 orthopaedic, 11 gynaecology and obstetrics, 2 neurosurgery and 6 other | Unclear (the study states a protocol including level 3 protective measures for operating room staff but not specified for which cases PPE was used) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 26 General anaesthesia and 11 spinal anaesthesia | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zhong and colleagues41 | 45 Caesarean sections, 4 orthopaedic | Yes | 37 Level 3 and 7 Level 1 | Not reported | Not reported | Spinal anaesthesia | Not reported | Lidocaine 2% (2 ml) and isobaric ropivacaine 0.75% | Not reported | Not reported |

Use of PPE and infection reduction strategies

Patient use of PPE was poorly reported, with only nine studies stating that patients wore any protection.19 , 21, 22, 23 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 39 Six of these reported the use of surgical masks only,19 , 21 , 22 , 28 , 35 , 38 with N95 mask respirators specifically mentioned in three studies.21 , 22 , 28

HCW use of PPE was more comprehensively reported, with 16 studies describing perioperative use.19 , 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 , 35, 36, 37, 38 , 41 Reported type of PPE used by HCWs was wide-ranging with N95 mask respirators, disposable surgical caps, medical goggles or positive-pressure headgear, and disposable protective clothing, gloves, and shoes/shoe covers described. However, details on duration of PPE use, and at what points during the perioperative period (e.g. only during intubation/aerosol-generating procedures), were lacking.

Nine of the studies in our review reported using operating rooms with negative pressure.19 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 38 Only one of these studies also described the postoperative care of a patient in a negative pressure ICU,24 although two studies described sending neonates to negative-pressure wards immediately after birth.29 , 31 However, details on other elements of ventilation such as air changes per hour, direction, and filtration were lacking.

Twelve of the studies describing Caesarean sections reported immediate separation of the neonates from their mothers after delivery, aiming to reduce risks of postpartum infection. Eight of these were conducted in China,19 , 21 , 30 , 34, 35, 36 , 38 , 39 whereas the other four were conducted in Italy,23 Portugal,31 Peru,16 and South Korea.28

Three studies reported on the decontamination of the anaesthesia machine after surgery,19 , 24 , 40 with two of the studies reporting no HCW infection with SARS-CoV-219,24 (the third study did not report HCW COVID-19 status40). A further study reported the discarding of disposable anaesthetic devices after single use.27

Patient outcomes

Patient outcomes reported included length of hospital stay, requirement for critical care, level of respiratory support and respiratory complications, discharge status, and mortality (Supplementary Table S9). None of the included studies reported on all these outcomes. Reporting on discharge status was very limited. Twelve studies reported length of stay in hospital, which ranged from 5 to 52 days.18, 19, 20 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 28, 29, 30, 31 , 33 , 35

In the largest cohort study (n=1128), the median length of stay in hospital (IQR) was 10 days (3–27) for minor surgery and 17 days (8–29) for major surgery, reported in a total of 1083 patients.33 This study reported an overall 30 day mortality of 23.8%, with a higher rate of mortality in patients undergoing elective surgery where the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus had been confirmed postoperatively rather than preoperatively (20.4% vs 9.1%). A number of patient factors were found to be associated with higher 30 day mortality including male sex (odds ratio [OR]=1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.28–1.40), emergency surgery (OR=1.67, 95% CI=1.06–2.63), major surgery (OR=1.52, 95% CI=1.01–2.31), older age (>70 yr) (OR=2.30, 95% CI=1.65–3.22), poorer preoperative condition as assessed by ASA physical status classification (OR=2.35, 95% CI=1.57–3.53), and surgery for malignancy (OR=1.55, 95% CI=1.01–2.39). Pulmonary complications, defined as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or unexpected postoperative ventilation, occurred in 51.2% of patients with COVID-19, and was associated with increased mortality compared with those who did not develop complications (38.0% vs 8.7%).

Postoperative use of ICU was poorly reported, and where it was reported (nine studies)18 , 20 , 22, 23, 24, 25 , 27 , 32 , 33 it was not always clear whether patients had been transferred there because of COVID-19 or whether they would have been transferred there because of the indication for surgery.27 Postoperative respiratory support was described in 10 studies,17 , 18 , 20 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 37 but as with ICU use it was not clear in some papers whether this would have occurred anyway. Postoperative use of analgesia was only reported in three studies,17 , 28 , 37 with only one reporting any formal pain assessment.19

Reporting of outcomes in neonates was more consistent, with 16 studies (out of 19 studies involving obstetric surgeries) reporting COVID-19 status16 , 19 , 21, 22, 23 , 26 , 28, 29, 30, 31 , 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and 12 of those studies reporting only negative test results, mainly for RT–PCR.19 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 28, 29, 30, 31 , 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Of the other four studies, two reported only positive tests23 , 39 and two reported a mix of positive and negative results.16 , 35 Apgar scores were reported in 14 studies (of the 19 involving obstetric surgeries), and these were generally very good or excellent.16 , 19 , 21, 22, 23 , 26 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 No neonatal mortalities were reported in any of the studies.

HCW outcomes

Most of the studies reported outcomes within a few days to 2 weeks after surgery.

HCW COVID-19 outcomes were only reported in 10 studies.19 , 22, 23, 24 , 28 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 37 , 41 One of these, a case series of 49 patients including outcomes from 44 anaesthetists, reported five anaesthetists testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 on RT–PCR testing after delivery of spinal anaesthesia during Caesarean section or orthopaedic surgery.41 One of the five anaesthetists testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 had worn level 3 PPE (2.7% of all who wore level 3 PPE), whereas four had worn level 1 PPE (57.1% of all who wore level 1 PPE), suggesting better HCW protection with level 3 PPE. This also appears to be supported by eight of the other nine studies where no HCW SARS-CoV-2 infections were reported when using PPE.19 , 22, 23, 24 , 28 , 30 , 35 , 37 Three of these studies reported level 3 PPE,22 , 30 , 37 one reported biosafety level 3,19 and four studies described PPE in detail including N95 masks, eye goggles, face shields, and surgical gowns.23 , 24 , 28 , 35 However, we can only make tentative recommendations on the use of PPE as it was not clearly reported how long PPE was worn before, during, and/or after the surgery, and whether any changes were made to the level of PPE worn at any stage (e.g. after intubation/extubation of the patient). Furthermore, we cannot be sure that HCW infection occurred as a result of caring for patients with COVID-19 rather than other sources such as infected colleagues or in the wider community.41

Cohort study

Patient characteristics

Between January 23, 2020 and March 31, 2020, 166 parturients underwent Caesarean section and were included in this study. Before surgery, two patients were confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and 36 patients were considered as suspected cases based on the above criteria (Table 2). After surgery, five suspected cases were confirmed and 11 suspected cases were ruled out. Finally, seven confirmed cases and 20 suspected cases of COVID-19 were identified. One case report9 and five patients (patients 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7) from a case series8 were reported previously by others. The other two patients (patients 2 and 3) in the case series8 undergoing Caesarean section between January 1, 2020 and January 23, 2020 were not included in the current study. All 20 suspected cases had imaging features of COVID-19. They were tested with RT–PCR only before discharge and the results were negative. For analysis, we combined these suspected cases and confirmed cases as one group (n=27) and patients not (suspected to be) infected with SARS-CoV-2 as a second ‘negative’ group (n=139). As shown in Supplementary Table S10, the BMI of suspected or confirmed patients was higher than that of negative patients (P=0.034). Symptoms associated with COVID-19 occurred only in suspected or confirmed patients; fever was the most common with an incidence of 44.4%, followed by cough (14.8%) and diarrhoea (3.7%).

Laboratory findings of patients before and after Caesarean section are summarised in Supplementary Table S11. Compared with baseline pre-procedural values, increased leukocyte and neutrophil counts were observed after surgery in all patients. Compared with negative patients, suspected or confirmed patients had lower leukocyte (P=0.003 before surgery; P=0.047 after surgery) and lymphocyte (P=0.030 before surgery; P=0.041 after surgery) counts during the perioperative period. Baseline pre-procedural C-reactive protein levels in confirmed or suspected patients were higher than negative patients (P=0.014), but were not difference from postsurgical levels. In negative patients, there were significantly elevated levels of CRP (P=0.006) and D-dimer (P=0.011) after surgery compared with baseline pre-procedural values.

Characteristics of anaesthesia and surgery

An overview of intraoperative characteristics is shown in Supplementary Table S10. Regional anaesthesia was the most common type of anaesthesia and was performed in 142 (85.5%) of parturients. Duration of operation in suspected or confirmed patients was longer than that in negative patients (P=0.003). However, there were no significant differences in blood loss, fluid management, or use of vasoactive drugs and flurbiprofen.

Maternal and fetal outcomes

As listed in Supplementary Table S10, 48.8% of patients received diclofenac, dezocine, or both for postoperative pain. There was no significant difference between suspected or confirmed patients and negative patients. Both the duration of oxygen therapy (P<0.001) and length of hospital stay (P<0.001) were significantly longer in suspected or confirmed patients than negative patients. No suspected or confirmed patients developed severe pneumonia or received noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation. However, a negative patient with liver cancer was intubated and died because of pulmonary embolism after surgery.

The median Apgar scores were 8 at 1 min and 9 at 5 min. There were no apparent differences between neonates in the suspected or confirmed group and the negative group. In the negative group, a neonate delivered at 25 weeks' gestation died 10 min after birth. In the confirmed group, a neonatal COVID-19 infection with positive RT–PCR assay results on pharyngeal swab was reported 36 h after birth, which had been reported in a previous study.8 However, the results of nucleic acid tests for SARS-CoV-2 on placenta specimens, cord blood, and mother's breast milk in this mother–neonate dyad were all negative.

Postoperative evaluation of HCWs

A total of 262 HCWs including 71 anaesthetists, 60 obstetricians, and 131 nurses (circulating nurses, instrument nurses, and neonatal nurses) were involved in these Caesarean sections. Level 3 PPE was used by all the HCWs during the operation. None of them reported COVID-19-related symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. As of April 15, 2020, none of them has been infected with SARS-CoV-2 according to chest CT findings, RT–PCR testing, and/or SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing.

Discussion

Our rapid literature review identified 26 studies reporting perioperative management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive such review to date. Most studies were low-quality case reports/series with low sample size, and even amongst the observational studies, perioperative management was not necessarily the main focus of any quantitative analysis conducted20 , 33 and was poorly reported.18 Thus, a cohort study of Caesarean sections, especially focusing on perioperative management and patients and HCW outcomes, was performed to augment the included evidence base.

All studies included in the review used either RT–PCR or chest CT to diagnose SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. This approach appears to be supported by the fact that RT–PCR testing did not always produce positive results, despite the presence of relevant clinical symptoms and the elimination of other viruses or comorbidities that could potentially explain those symptoms. In our cohort study, only five of 27 participants with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT–PCR. The wider literature has also reported uncertainty in diagnostic performance of RT–PCR42 and when compared with CT their sensitivity ranges from 50% to 81%.43, 44, 45 The use of CT does need to be balanced against the extra risk of exposing patients to radiation, particularly for women undergoing Caesarean section whose fetus will also be exposed.46 This is an area that requires further investigation, but consideration should be given to using both approaches in diagnosing COVID-19.

The timing of COVID-19 testing also needs to be considered as higher mortality was reported in patients undergoing elective surgery where the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus was confirmed postoperatively rather than preoperatively (20.4% vs 9.1%).33 Performing tests preoperatively will enable informed decisions about the postponement of surgeries to be made for patients who test positive and are thus at increased risk of postoperative complications. There may also be requirements to ensure appropriate levels of care, such as facilities or staffing, are available for the postoperative period should complications arise. COVID-19 testing may also influence ICU admissions and transmission to HCWs.47, 48, 49 This further suggests that testing for possible SARS-CoV-2 infection should take place before surgery, as supported by the ASA and Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation joint guidelines.50 However, as this might be difficult for emergency surgery, a standardised diagnosis and treatment protocol for emergency patients should therefore be developed. This is already happening in some places, and although preoperative screening will potentially increase the time between admission and surgery, initial evidence suggests that this risk can be minimised to the point that it can be balanced against the potential risk of performing surgical procedures in COVID-19 patients.51 Further research is necessary to establish whether the testing pathway is of more clinical benefit than not having it. In patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, the COVID-19 status of newborns should also be taken into account where relevant. Testing should be performed as soon as possible after delivery to help prevent transmission to HCWs and to ensure risk to the newborn is minimised, with early recognition and management of symptoms.

Despite being included in perioperative anaesthesiology guidelines for HCWs in both the USA and China,3 , 50 PPE use was poorly reported by studies in patients (nine studies).19 , 21, 22, 23 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 39 Current guidance in the UK is that anyone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should wear a surgical face mask in clinical areas, communal waiting areas, and during transportation as long as this does not compromise their clinical care.52 In tuberculosis patients, use of surgical face masks has been shown to confer a 56% decreased risk of transmission compared with those not wearing a mask.53 A literature review of studies analysing the effectiveness of respiratory protection for HCWs against infectious diseases found that guidelines were consistent in recommending at least an N95 respirator for care of patients with tuberculosis.54 Despite this, there is currently no evidence that patient use of face masks reduces risk of COVID-19 transmission to HCWs, despite these studies not reporting any HCW infections.19 , 21, 22, 23 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 39 Better reporting was observed relating to HCWs themselves. A recent study showed the effectiveness of HCWs wearing PPE in preventing COVID-19 infection and advocated its continued use in the absence of a vaccine.55 In our cohort study, none of the 262 HCWs developed COVID-19, suggesting that both regional and general anaesthesia can be delivered safely to patients with COVID-19 when surgical or N95 masks are applied in patients and level 3 PPE is used by HCWs during the perioperative period. The use of aprons, sterile fluid-resistant disposable gowns, sterile gloves, fluid-resistant surgical masks, and eye protection is recommended in the UK for Caesarean sections.56 However, high-level PPE is difficult to work in. For this reason, it is important that future studies report on the duration of PPE use, whether they were used at particular points in the surgical process as some procedures are considered particularly high risk of airborne transmission, and what levels constitute safe use.57 It is also important to establish when PPE use is not necessary, to prevent wastage. Until these questions are addressed, HCWs should continue to use level 3 PPE during the perioperative period for all untested, suspected, or confirmed cases of COVID-19 during times of pandemic and local outbreak.55

Although this was not analysed directly with respect to postoperative outcomes, we found that nine of the studies reported conducting surgical procedures in negative pressure operating rooms.19 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 38 Negative pressure rooms are commonly used in infection control and ensure that air continually flows into the room, rather than the surrounding area. However, most hospitals only have a limited number of negative pressure operating rooms and therefore have to adapt additional rooms for this purpose. As current recommendations on minimum environmental ventilation requirements are based on previous non-COVID-19 work, further analysis and reporting on ventilation characteristics is required.3

We identified 12 studies reporting the separation of neonates from mothers after Caesarean section.16 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 34, 35, 36 , 38 , 39 In our cohort study, newborns of mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were also transferred to an isolated observation ward after birth. At least in China, where nine of those studies were conducted, this represents a significant change from standard practice where normally mother and child skin-to-skin contact is encouraged, with recognised neurobiological benefits for mother and neonate. Although a newborn whose mother was confirmed with COVID-19 tested positive 36 h after birth in our cohort study, whether the case was a contact transmission or a vertical transmission remains to be confirmed. As the remaining studies did not accurately report the level of mother and child contact, it is not possible to determine whether separation decreases the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerging data suggest that allowing neonates to room in with their mothers and breastfeed confers low risk of perinatal and vertical transmission when a face mask is worn and proper hygiene is observed.58 Because of these clinical implications and the potential impact on maternal–neonate interaction, this area requires urgent investigation.

A large cohort study identified patient and surgical factors associated with 30-day mortality.33 This multicentre study is easily the largest study of postoperative outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and because of the size and quality of the analysis, it is the only study from which we can make strong conclusions.33 Consequently, future studies should consider longer-term reporting of health outcomes.

Previous studies found low mortality rates (1%) and requirement for respiratory support (10%) amongst pregnant women with COVID-19, and low neonatal transmission (5%), which our study supported.59 , 60 However, the duration of operation, oxygen therapy, and length of hospital stay were significantly longer in suspected or confirmed patients than negative patients. An optimal approach to perioperative management in COVID-19 patients including appropriate use of anaesthetics and analgesics needs to be determined in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the rapid review approach is the ability to quickly synthesise relevant original articles and identify current perioperative practices that are associated with favourable postoperative outcomes. This has already enabled us to make early clinical recommendations (Table 5 ) on the perioperative management of COVID-19 to the Scottish Government via the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), which can be disseminated to policymakers and HCWs and inform future perioperative practice (Roberta James, SIGN Programme Lead, personal communication, 2020).

Table 5.

Clinical recommendations for the perioperative management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and suggestions for further research.

| A. Clinical recommendations |

| During the perioperative period, when COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed: |

| 1. Testing for COVID-19 should be conducted preoperatively. During a pandemic or local outbreak, all patients should be tested. |

| 2. RT–PCR and chest CT (along with relevant clinical signs) should be conducted together to confirm COVID-19 diagnosis and reduce waiting times. |

| 3. Surgeries should be conducted in negative pressure operating rooms where possible, with HCWs using Level 3 PPE and patients wearing face masks, if practical, until further evidence is available. During a pandemic or local outbreak all HCWs should use Level 3 PPE for surgeries involving untested patients. |

| 4. Clinicians should consider relevant risk factors of increased mortality in COVID-19 patients including male sex, age >70 yr, poor preoperative condition, malignancy and the urgency and extent of surgery before deciding whether to conduct surgery. |

| 5. Strategies should be implemented to reduce the risk of postoperative respiratory complications and associated mortality (e.g. use of regional anaesthesia over general anaesthesia and postponing surgery for patients with correctable pathophysiology). |

| 6. Clinical management should take account of the potential need for prolonged hospital stay, particularly in high-risk groups. |

| 7. Clinicians should consider the isolation of neonates immediately after birth if the mother is suspected or confirmed as having COVID-19. |

| B. Research recommendations |

| 1. Optimal approach to perioperative diagnosing of COVID-19 needs to be determined, taking into account the false-negative rate of RT–PCR tests. |

| 2. There should be routine recording and reporting of specific perioperative management approaches when COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed, including anaesthetics/analgesics used, to allow understanding of their relationships with postoperative outcomes. |

| 3. Individual studies should provide more detailed reporting on the duration of PPE use during the perioperative period, by HCWs and patients, when COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed, and whether any changes should be made for specific procedures (e.g. tracheal intubation/extubation). |

| 4. Current and future studies should record and report long-term outcomes of surgery in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 for patients and HCWs. |

| 5. The length of time after COVID-19 resolution before a patient can undergo surgery, without increased risk, needs to be established. |

Because COVID-19 is a new and developing disease, hospital departments are having to adapt quickly to ensure optimum care and they rely on quick and accurate clinical guidance on how to provide this. However, many hospitals are not set up to conduct rapid research involving data collection, particularly during a global pandemic, and consequently there are gaps in reporting that this review has identified. A possible solution to this is to implement electronic health (eHealth) recording of patient data to ensure automated availability of relevant items of interest.

Converse to the rapid synthesis of the current literature, the short period of time that COVID-19 has been in existence relative to other infectious diseases means that there has not been enough time for many large and comprehensive cohort studies to be published, and therefore the majority of studies included in this review are case reports and series. This means that the clinical implications of these studies should be treated with caution until further robust studies are published, preferably in the form of RCTs such as the Randomised Evaluation Of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) Trial (https://www.recoverytrial.net/).61

The rapid nature of this review means that more recently published articles may have been missed, although we mitigated this risk by conducting a further (targeted) literature search before submission. Excluding those not in English is pertinent given the global status of the COVID-19 pandemic. We also had to exclude two studies from Tongji Hospital in Wuhan as some of the participants were also included in the cohort study for this paper.8 , 9

Conclusions

From this rapid literature review and cohort study, we can make early clinical and research recommendations around the perioperative management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. These are presented in Table 5 and include timing of COVID-19 testing before surgery, more detailed reporting of patient and HCW use of PPE, more detailed reporting of the perioperative use of anaesthesia and analgesia, and research into the long-term consequences of COVID-19. Together it is anticipated that these recommendations will contribute to improved postoperative outcomes for both patients with COVID-19 and HCWs treating those patients.

Authors' contributions

Study conception and design: HZ, WM, BHS, JH, LAC

Data acquisition: HZ, JY, ZZ, XZ, AL, LW, WZ, HLH, AC

Data analysis and interpretation: all authors

Drafting of the article and revising for important intellectual content: all authors

Final approval of the published version: all authors.

Declarations of interest

LAC is an editor of the British Journal of Anaesthesia. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Partly supported by the University of Dundee Global Challenges Research Fund.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lin Yan and Gang Chen from Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, for their efforts in collecting the information that was used in this study; and all the patients and healthcare workers involved in the study.

Handling editor: Hugh C Hemmings Jr

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.049.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200810-covid-19-sitrep-203.pdf?sfvrsn=aa050308_2 Situation Report – 203. 2020. Available from:

- 3.Chen X., Liu Y., Gong Y., et al. Perioperative management of patients infected with the novel coronavirus: recommendation from the joint task force of the Chinese society of Anesthesiology and the Chinese association of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1307–1316. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenland J.R., Michelow M.D., Wang L., London M.J. COVID-19 Infection: implications for perioperative and critical care physicians. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1346–1361. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagens A., Sigfrid L., Cai E., et al. Scope, quality, and inclusivity of clinical guidelines produced early in the covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ. 2020;369:m1936. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khangura S., Konnyu K., Cushman R., Grimshaw J., Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu N., Li W., Kang Q., et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:559–564. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S., Guo L., Chen L., et al. A case report of neonatal 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:853–857. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proença R., Mattos Souza F., Lisboa Bastos M., et al. Active and latent tuberculosis in refugees and asylum seekers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:838. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alwhaibi M., Al Aloola N.A. Healthcare students' knowledge, attitude and perception of pharmacovigilance: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamboni K., Baker U., Tyagi M., Schellenberg J., Hill Z., Hanson C. How and under what circumstances do quality improvement collaboratives lead to better outcomes? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0978-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China Diagnosis and treatment scheme of COVID-19 (Interim version 7) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtmlhttp://kjfy.meetingchina.org/msite/news/show/cn/3337.html Available from: English version translated by the Chinese Society of Cardiology, Available from:

- 16.Alzamora M.C., Paredes T., Caceres D., Webb C.M., Valdez L.M., La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:861–865. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catellani F., Coscione A., D'Ambrosi R., Usai L., Roscitano C., Fiorentino G. Treatment of proximal femoral fragility fractures in patients with COVID-19 during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Northern Italy. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2020;102:e58. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chehrassan M., Ebrahimpour A., Ghandhari H., et al. Management of spine trauma in COVID-19 pandemic: a preliminary report. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020;8:270–276. doi: 10.22038/abjs.2020.47882.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen R., Zhang Y., Huang L., Cheng B.H., Xia Z.Y., Meng Q.T. Safety and efficacy of different anesthetic regimens for parturients with COVID-19 undergoing Cesarean delivery: a case series of 17 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01630-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doglietto F., Vezzoli M., Gheza F., et al. Factors associated with surgical mortality and complications among patients with and without coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:1–14. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong L., Tian J., He S., et al. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Y., Wang L., Wu G., Lei X., Li W., Lv J. Anesthesia and protection in an emergency cesarean section for pregnant woman infected with a novel coronavirus: case report and literature review. J Anesth. 2020;34:613–618. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02796-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrazzi E., Frigerio L., Savasi V., et al. Vaginal delivery in SARS-CoV-2 infected pregnant women in Northern Italy: a retrospective analysis. BJOG. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firstenberg M.S., Libby M., Ochs M., Hanna J., Mangino J.E., Forrester J. Isolation protocol for a COVID-2019 patient requiring emergent surgical intervention: case presentation. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:15. doi: 10.1186/s13037-020-00243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y., Xi H., Chen L. Emergency surgery in suspected COVID-19 patients with acute abdomen: case series and perspectives. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e38–e39. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidlöf S., Savchenko J., Brune T., Josefsson H. COVID-19 in pregnancy with comorbidities: more liberal testing strategy is needed. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:948–949. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He H., Zhao S., Han L., et al. Anesthetic management of patients undergoing aortic dissection rpair with suspected severe acute respiratory syndrome COVID-i9 infection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:1402–1405. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee D.H., Lee J., Kim E., Woo K., Park H.Y., An J. Emergency cesarean section on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) confirmed patient. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020;73:347–351. doi: 10.4097/kja.20116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Zhao R., Zheng S., et al. Lack of vertical transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1335–1336. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu D., Sang L., Du S., Li T., Chang Y., Yang X.A. Asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in late pregnancy indicated no vertical transmission. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyra J., Valente R., Rosario M., Guimaraes M. Cesarean section in a pregnant woman with COVID-19: first case in Portugal. Acta Med Port. 2020;33:429–431. doi: 10.20344/amp.13883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mi B., Chen L., Panayi A.C., Xiong Y., Liu G. Surgery in the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Br J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1002/bjs.11733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nepogodiev D., Glasbey J.C., Li E., et al. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song L., Xiao W., Ling K., Yao S., Chen X. Anesthetic management for emergent cesarean delivery in a parturient with recent diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a case report. Transl Perioper Pain Med. 2020;7:234–237. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun M., Xu G., Yang Y., et al. Evidence of mother-to-newborn infection with COVID-19. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e245–e247. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X., Zhou Z., Zhang J., Zhu F., Tang Y., Shen X. A case of 2019 novel coronavirus in a pregnant woman with preterm delivery. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:844–846. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia H., Zhao S., Wu Z., Luo H., Zhou C., Chen X. Emergency Caesarean delivery in a patient with confirmed COVID-19 under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:e216–e218. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng H., Xu C., Fan J., et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323:1848–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z.J., Yu X.J., Fu T., et al. Novel coronavirus infection in newborn babies under 28 days in China. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000697. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00697-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao S., Ling K., Yan H., et al. Anesthetic management of patients with COVID 19 infections during emergency procedures. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:1125–1131. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong Q., Liu Y.Y., Luo Q., et al. Spinal anaesthesia for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and possible transmission rates in anaesthetists: retrospective, single-centre, observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woloshin S., Patel N., Kesselheim A.S. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection — challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Callaway M., Harden S., Ramsden W., et al. A national UK audit for diagnostic accuracy of preoperative CT chest in emergency and elective surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:705–708. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernigou J., Cornil F., Poignard A., et al. Thoracic computerised tomography scans in one hundred eighteen orthopaedic patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: identification of chest lesions; added values; help in managing patients; burden on the computerised tomography scan department. Int Orthop. 2020;44:1571–1580. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04651-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gruskay J.A., Dvorzhinskiy A., Konnaris M.A., et al. Universal testing for COVID-19 in essential orthopaedic surgery reveals a high percentage of asymptomatic infections. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2020;102:1379–1388. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.20.01053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y.X.J., Liu W.-H., Yang M., Chen W. The role of CT for Covid-19 patient’s management remains poorly defined. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:145. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rescigno G., Firstenberg M., Rudez I., Uddin M., Nagarajan K., Nikolaidis N. A case of postoperative Covid-19 infection after cardiac surgery: lessons learned. Heart Surg Forum. 2020;23 doi: 10.1532/hsf.3011. e231–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu W., Huang X., Zhao H., Jiang X. A COVID-19 patient who underwent endonasal endoscopic pituitary adenoma resection: a case report. Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E140–E146. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Society of Anesthesiologists and Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation The ASA and APSF joint statement on perioperative testing for the COVID-19 virus. 2020. https://www.asahq.org/-/media/files/spotlight/asa-and-apsf-statement-on-perioperative-testing-for-the-covid-19-virus-june-3.pdf?la=en&hash=F77342E667AF5CBE503D8597A5B6894DAB2FBC66 Available from:

- 51.Meng Y., Leng K., Shan L., et al. A clinical pathway for pre-operative screening of COVID-19 and its influence on clinical outcome in patients with traumatic fractures. Int Orthop. 2020;44:1549–1555. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04645-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Public Health England COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE) 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe Available from:

- 53.Dharmadhikari A.S., Mphahlele M., Stoltz A., et al. Surgical face masks worn by patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: impact on infectivity of air on a hospital ward. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1104–1109. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1190OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.CADTH Rapid Response Reports . Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; Ottawa (ON): 2014. Respiratory precautions for protection from bioaerosols or infectious agents: a review of the clinical effectiveness and guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu M., Cheng S.-Z., Xu K.-W., et al. Use of personal protective equipment against coronavirus disease 2019 by healthcare professionals in Wuhan, China: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]