Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has highlighted and amplified structural inequalities; drawing attention to issues of racism, poverty, xenophobia as well as arguably ineffective government policies and procedures. In South Africa, the pandemic and the resultant national lockdown have highlighted the shortcomings in the protection and care of children. Children in alternative care are particularly at risk as a result of disrupted and uncoordinated service delivery.

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences and impact of the pandemic and the resulting social isolation on the wellbeing and protection of children living in a residential care facility.

Methods and participants

We used qualitative, participatory approaches – specifically draw-and-write methods – to engage with 32 children (average age = 13.5 years) living in a residential care facility in Gauteng.

Findings

Children in care demonstrated an awareness of the socio-economic difficulties facing communities in South Africa, and shared deep concerns about the safety, well-being and welfare of parents and siblings. Although they expressed frustration at the lack of contact with family members, they acknowledged the resources they had access to in a residential care facility, which enabled them to cope and which ensured their safety.

Discussion and conclusion

We focus our discussion on the necessity of a systemic response to child welfare, including a coordinated approach by policy makers, government departments and child welfare systems to address the structural factors at the root of inequality and inadequate, unacceptable care. This response is essential not only during COVID-19 but also in pre- and post-pandemic context.

Keywords: Child protection, Structural inequalities, Pandemic, Covid-19, Lockdown, Residential care, South Africa

1. Introduction

Children live within contexts framed by political, cultural, economic and systemic histories and realities. For the majority of South African children this means exposure and vulnerability to a multitude of risks, including poverty, child abuse, neglect, and exposure to violence. COVID-19 has devastatingly exacerbated these risks, highlighting the numerous fault lines and limitations in the care and protection of South African children. Pre-existing and historical socio-economic inequalities and systemic injustices combined with significant mistakes by key ministries during this period have had a detrimental impact on children.

Children in alternative care are dependent on multiple systems for their protection and are particularly vulnerable at this time. Research shows that emergency responses to COVID-19 intended to contain the virus results in poor and interrupted service delivery (Fallon et al., 2020). Children in care are at particular risk of being neglected by the state as the focus turns to health information, adapted modalities of education and other services to communities (Better Care Network, 2020). Lockdown restrictions also place additional strain on children in care; with care facilities either shutting down and releasing children prematurely, or keeping children in-care, without access to family and friends. Emerging reports from South Africa confirm this, showing that key government departments responsible for vulnerable children in residential care have been severely hampered by the crisis (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020a). Continuity of care as well as coordination of services between all essential service providers; key activities in ensuring the safety and protection of children; have been constrained (Fallon et al., 2020).

In this exploratory study, we consider the impacts of COVID-19 for children in one non-governmental organisation in Johannesburg, South Africa, which aimed to provide continuous and consistent care for children living in residential care. We ask: ‘What can the experiences and perspectives of South African children in care during lockdown tell us about the themes we should focus on to improve care moving forward? We focus on children’s experience of the lockdown as well as COVID-19; their concerns as well as the protective resources that enables them to cope. We frame the experiences of these children in care against the background of a crippled social system and reflect critically on what systemic changes are needed to support children. This study offers a way forward and contributes to an emerging body of research on the impact of pandemics on child well-being and protection.

2. Literature review

2.1. South Africa under lockdown

To address a global pandemic such as COVID-19 requires inspired, informed leadership and co-ordination between all sectors of government and civil society. This has occurred to a limited extent in South Africa.

In comparison to the hesitancy that characterised some of the global responses to the pandemic, South Africa’s initial response was decisive. The complete national lockdown, which began on the 26th March 2020, saw trade, places of worship, and recreational activities shut down. A national curfew was mandated and movement between provinces prohibited. These stringent measures were considered necessary to flatten the curve and to ready an already vulnerable health system (Baldwin-Ragaven, 2020) for a potential influx of cases. However, some rights groups and commentators raised concerns about the impact and feasibility of such measures in a context with gross pre-existing and historic socio-economic inequalities (World Bank, 2018), and a struggling economy (Marais, 2020). Acknowledging these challenges and efforts to mitigate against the worst impacts of the pandemic, the South African government introduced a number of temporary social and economic relief measures, which included increasing the health budget, economic support through the unemployment insurance fund, support for small business and tax relief measures. Social relief support measures included the establishment of the special COVID-19 Social Relief Distress (SRD) grant of R350 per month (£16/$20) as well as increases to existing social welfare grants, for example, the basic child support grant was increased by an additional R440 per month (£20/$26). The government, through the Department of Social Development, also pledged to distribute food packages to communities most in need.

As predicted, however, in a country with such disparate, intense needs, these resources have simply not been sufficient, failing to buffer the majority of South Africans from worsening social and economic conditions (van Bruwaene, Mustafa, Cloete, Goga, & Green, 2020). Findings from the National Income Dynamics Study- Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Spaull et al., 2020), found that almost 3 million people lost their jobs during the most intensive lockdown period, and during this time 1 in 7 children reported that they had gone hungry in the week before they were interviewed during May or June (NIDS-CRAM, 2020). Compounding what is rapidly being seen as a humanitarian crisis, is the constrained leadership at national and provincial level and lack of co-ordination between government departments (Thebus, 2020). The Department of Social Development (DSD), a key department in the care and protection of children and its Minister, have been severely criticised for providing little leadership during this period (Weiner, 2020). For example, DSD’s delivery of the much needed and promised food parcels have been hampered by reports of corruption and theft, cumbersome processes, lack of capacity to distribute food packages, lack of data on who needs this assistance and insufficient funds to meet the needs of the population (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020a).

Similarly, distribution of the COVID SRD grant has been challenged by complicated processes making it difficult to access. Activists report that as at July 2020, approximately four months into lockdown, 74% of individuals eligible to receive the grant have not received it (Thebus, 2020).

The Department of Basic Education (DBE), another crucial department, took a decision at the beginning of the lockdown period to also stop the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP). As a result, the 9.6 million children who are dependent on this one meal a day have had to go without food. A number of children’s rights groups instituted legal action against the Minister of Basic Education as well as the provincial MEC’s, arguing that the failure of government to recommence this nutrition programme was a regression of the rights to education and to basic nutrition (See www.centreforchildlaw.co.za). On the 17 July 2020, DBE was ordered to reopen the NSNP, with the Judge asserting that in closing the programme, the Minister, and her MECs were in breach of their constitutional and statutory duties (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020b).

2.2. South African Children under lockdown

To understand the impact that COVID-19 has on the individual child we reference a multi-systemic framework; this framework situates the individual within broader systems and contextual factors, acknowledging the interconnectedness between the individual, the family, the community and society . Masten and Motti-Stefanidi (2020) note that risks to individuals span across all of these levels and as the pandemic unfolds, the challenges to these systems also change. Similarly, factors that enable and support resilience are situated across levels. Here we draw on a COVID-19 specific explanation of systemic risks shared by the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action (2019).

From this perspective, individual level risks during a pandemic include increased risks of child abuse, neglect, violence, and exploitation, as well as potential psychological distress and a negative impact on development. Challenges also include adjusting to the changed circumstances, with school closures, disrupted routines, isolation from friends and peers, fear of the unknown and losing loved ones (Ghosh, Dubey, Chatterjee, & Dubey, 2020; Orgilés, Morales, Delvecchio, Mazzeschi, & Espada, 2020; Zhou, 2020). These changes may result in increased feelings of anxiety and distress, or may exacerbate existing mental health issues and enhance the risk of developing psychological disorders (Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, 2019). At the level of the family, risks may include family separation, reduced access to social supports, caregiver distress, heightened risk of violence/domestic abuse, disruption to family earnings as well as disrupted family connections and support, and fear of the disease (Spinelli, Lionetti, Pastore, & Fasolo, 2020). Community level risks may include distrust within communities, competition over limited resources, and inadequate access to support services including educational resources and support (Fischer et al., 2020; Sekyere, Bohler-Muller, Hongoro, & Makoae, 2020). Lastly, societal level risks include corrosion of social capital and disrupted and inadequate access to basic services (Fischer et al., 2020; Scott, 2020; Sekyere et al., 2020).

As discussed, within the South African context, these systemic risks are amplified by pre-existing challenges. Present day South Africa continues to be characterized by deeply embedded inequalities and structural violence, a legacy of colonialism and apartheid (Loffell, 2008; Tshishonga, 2019). This inequality manifests in high levels of poverty, discrimination, poor access to education, health and social services, poor service delivery and exposure to high rates of communal and interpersonal violence (Zizzamia, Schotte, & Leibbrandt, 2019). Children in South Africa are particularly vulnerable as a result of these structural challenges; for example, poverty creates food insecurity which impacts on a child’s physical, mental and cognitive development (Hall & Sambu, 2014). Research suggests that prior to the pandemic a quarter of children in South Africa were stunted, 12.5 million children were dependent on child support grants, 59% of children lived below the upper-bound poverty line, 30% of children were without access to water and 8% of children lived in overcrowded households (Hall & Sambu, 2014; Van der Berg & Spaull, 2020).

Poverty is recognized as a significant barrier to children’s well-being, impacting on health and educational opportunities and increasing vulnerability to child maltreatment (Fernandez, Delfabbro, Ramia, & Kovacs, 2019; Loffell, 2008; Manyema & Richter, 2019; Meinck, Cluver, & Boyes, 2015). Artz and team (Artz, Meer, & Muller, 2018) found that approximately 40% of young people in South Africa have had direct experiences of abuse. Fear and additional stressors caused by the pandemic provides an enabling environment that may exacerbate or trigger diverse forms of violence against children and women (Peterman, O’Donnell, Shah, & Gelder, 2020). Given the existing high levels of gender-based violence, sexual abuse and child abuse in South Africa, of significant concern during these exceptional times is the safety of children, especially as many are in close, constant proximity to potential abusers. Lack of income, employment opportunities and food insecurity are likely to increase conflict within families, thereby increasing risk to children (Mathews, Jamieson, & Makola, 2020). The South African Police Service noted a 37% increase in gender based violence related calls within the first week of lockdown, as compared to the same period in 2019 (www.iss.org.za). During this period, Childline South Africa (www.childlinesa.org) reported a 400% increase in calls; while the majority of these were dropped calls, there was a noticeable 62% increase in cases of child abuse and neglect. Similarly, since the beginning of lockdown there has been a notable increase in the number of babies abandoned; approximately 27 abandoned babies have been taken in by organizations in and around Johannesburg (www.babiesmatter.org.za; www.doorsofhope.org.za; Bega, Smillie, & Ajam, 2020).

Similarly, disruptions in education risks the wellbeing of children both in the short-term and may have significant long-term consequences. While some children have been able to access online learning, for the majority of children living in conditions of poverty, with no access to a phone, television or computer, this option has not been possible, further deepening the digital divide (Fore, 2020). Van der Berg and Spaull (2020) report that by the beginning of August 2020, at least 4 million children will have missed more than half (57%) of the number of school days and they note that the education system in South Africa is unlikely to make up this time. This situation has significant long-term consequences in a country with staggeringly high rates of illiteracy (Howie et al., 2017).

2.3. Residential care in South Africa

The Children’s Act 38 (Children’s Act, 2005), forms the basis of child welfare practices in South Africa (Schmid & Patel, 2014) and regulates placement of children in need of care and protection. Section 150 of the Act makes clear that children in need of care should be placed in alternative care and describes alternative care options to include foster care, child and youth care centres (CYCCs) and temporary safe care (Mokgopha, 2019). Placement at CYCCs are considered to be a last resort option, with in-family care regarded as optimal. Existing research suggests that there are 354 registered CYCCs in South Africa, supporting a population of approximately 13,500 children and young people; an unknown number of vulnerable children live in unregistered centres (Mamelani, 2013).

Children identified as vulnerable include those who;

-

i)

have been abandoned or orphaned and are without any visible means of support;

-

ii)

display behaviour which cannot be controlled by the parent or care-giver;

-

iii)

live or work on the streets or beg for a living;

-

iv)

are addicted to a dependence-producing substance and are without any support to obtain treatment for such dependency;

-

v)

have been or are at risk of serious physical or mental harm; or

-

vi)

have been abused, neglected, or exploited (Mahery, Jamieson, & Scott, 2011).

Given the wide range of needs of children entering care, CYCCs are mandated to not only provide for the basic needs of children in terms of food and shelter and access to education, but are required to make therapeutic programmes available. Section 191 of the Children’s Act provides a comprehensive list of programmes that should be offered (Children’s Act, 2005).

Jamieson (2017) asserts that high rates of child sexual abuse, parent mortality, poverty and neglect have resulted in significant increases in children in need of alternative care. However, limited resources, stringent registration procedures, lack of funding and inadequate infrastructure impact on the services actually offered to children in care (Jamieson, 2017). CYCCs have been criticised for providing inadequate care in facilities that are deficient and in poor condition, with staff that are not trained and supervised, and services that fail to meet the children’s specific developmental, psychological, cultural and language needs, and which fails to include youth in decision making (Hansungule, 2018; Malatji & Dube, 2015; Schmid & Patel, 2014).

2.4. Residential care facilities under lockdown

Historically, poor coordination between social and health systems in South Africa during periods of health crises has meant that services to child and youth care centres have been inadequate (Allende & Khota, 2020). The lockdown has intensified these weaknesses. Challenges and system failures during a pandemic are not unique to South Africa, Fallon et al. (2020) note that during a pandemic, the ability of public agencies to operate is hampered. Findings from key stakeholders in Canada report that public system resources and capacity are under strain, struggling to provide services and supports to clients. Goldman, van Ijzendoorn, and Sonuga-Barke (2020) cautioned that during this time, many residential care facilities may close, with children abruptly sent back to families. They (Goldman et al., 2020) add that this practice may have a compound jeopardy impact, in increasing children’s risk of contracting the virus, and also resulting in emotional and health issues, poor access to education and increased risk of abuse. South African organizations caring for the welfare of children have reported that the Department of Social Development (DSD) has not provided adequate leadership and little, if no support, during this period (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020b). Aside from an initial communication describing steps in managing an outbreak at a residential care facility, no further guidance has been provided to organisations. No personal protective equipment has been supplied and no extra funds were/are offered to ensure that safety equipment may be bought and no testing and quarantine facilities established (Personal communication with Author 1, 2020). With no social workers actively working in the field since the beginning of lockdown, removal of children from dangerous situations as well as placement of children into care has also stalled (Personal communication with Author 1, 2020). Added to this difficulty, many residential care facilities have not been able to renew registrations and without this renewal are not able to access funding and potentially face closure (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020b). Importantly, without a valid registration, new children cannot be accepted into care; results from an informal survey of 24 organizations show that approximately 124 children needing care have been turned away (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020b).

Aside from the general risk posed by COVID-19, residential care facilities have additional risks (Allende & Khota, 2020; Fallon et al., 2020). Our interactions with members of a Residential Care Facilities Group1 in Gauteng, suggest that these risks include: the challenges of maintaining COVID-safe practices in communal living spaces, large numbers of children living in small spaces, rostering of staff, health risks and needs of children with pre-existing health conditions such as HIV, AIDS and tuberculosis, and new admissions as well as children absconding from and returning to care. Exacerbating these challenges are limited resources and limited means to quarantine children.

Residential care facilities have had to be proactive, adapting and testing safety measures as the weeks of lockdown continued. Many, like the CYCC we worked with in this exploratory research project, made informed decisions to keep all children in care under strict lockdown. Children, who would have gone home for a brief family visit, were instead kept in care. Other organisations evaluated on a case by case basis each child’s context and chose to keep two-thirds of children in care (Allende & Khota, 2020).

Many children living in residential care come from disadvantaged communities and have been exposed to one or multiple traumas within the home or the community and some have pre-existing health problems (Meintjes, Moses, Berry, & Mampane, 2007). In this context, children may be safer in care where they have access to regular meals, shelter, protection and access to educational resources.

3. Study Aims and Methods

The aim of this rapid exploratory, qualitative study was to understand how children residing in a care facility in South Africa understood and experienced the lockdown measures imposed as a result of COVID-19. We focused on the concerns that children in care experienced during this period as well as what helped them to cope.

Our decision to speak with children was informed by an acknowledgement that children are experts in their lives and capable of speaking on their own behalf. Titi and Jamieson (2020) found that only 10% of stories focus on children, and less than half this number includes the voices of children, noting that such exclusion is in fact a violation of their rights.

3.1. The Context

Children residing at a child and youth care centre in Gauteng, South Africa (herewith referred to as CYCC X) were invited to participate in the study. A CYCC is defined as a facility that provides residential care for more than six children who are not living with their biological families (Children’s Act, 2005). CYCC X is situated in Gauteng (South Africa) and was established by a social worker in 1992, in response to a growing number of mainly black South African children living on the streets. During this period, South Africa was slowly transitioning out of apartheid and the country was characterised by uncertainty and ongoing hostility between various racial groups. The needs of disadvantaged, black children were often not acknowledged and services for this group were lacking or non-existent (Loffell, 2008).

The founding social worker secured an old building and initially housed 20 street connected children. The Centre was dependent on community donor funding. In 1999 the old building was condemned and through private donors, a new building was acquired. The Centre was registered as a non-profit organisation in 2001. At present, 47% of the running costs are covered by government funding, the rest is obtained through various fundraising initiatives and local and international donors (Daly, 2020). From 1992 to the current date, the Centre has cared for over 5000 children and is an active member of the child and youth care sector.

The majority of children at CYCC X have been exposed to one or more risk factors, including poverty, neglect, physical, emotional and/or sexual abuse and streetism. Reasons for admission noted in the CYCC’s most recent progress report show that; 18% of children were admitted because of familial poverty, 5% of children were exposed to domestic violence, 23% reported parental neglect, 17% reported some form of abuse, 1% were placed in care for substance use, 8% were not attending school, 8% were street connected and 20% displayed uncontrollable behaviour prompting parents to request placement (Progress report, 2020).

As mandated in the Children’s Act (Children’s Act, 2005), CYCC X offers extensive programs to meet the physical, psychosocial, and trauma needs of these vulnerable children. This service is delivered to children primarily through the in-care, residential programme and through a pre-care, prevention and early intervention programme and an after-care, transitory support programme. The majority of children at the care facility attend school. The Centre’s 2020 report showed that approximately 114 children were enrolled across 21 different schools in the area. Children not ready or unable to return to the formal education sector are placed in an in-house bridging school programme. Children have access to professional psycho-social therapy, medical and psychiatric care if needed, extra-mural activities, which include dance and drama and daily tutoring assistance. Older youth are given an opportunity to earn money through various entrepreneur initiatives. Regular home visits, where possible and deemed safe, are encouraged (Daly, 2020).

At the time of this study, CYCC X had 151 children in care. During the initial lockdown period, April – early June 2020, 7 children were admitted into care and no children absconded from care. CYCC X established a quarantine facility on their premises, requiring children entering to isolate from other children for a period of two weeks. A space was created adjacent to but separate from the primary living areas. To limit risk posed by staff entering the facilities, the usual 48 -h roster system was replaced by a 21-day shift cycle, with staff self-isolating prior to beginning a shift. As lockdown measures have gradually eased, staff have moved to a 7-day shift cycle. During the complete lockdown period only essential services continued. Children in therapy consulted therapists online. Although many of the schools that the children attended did not have an online teaching programme, educational activities continued throughout the period at the Centre, with lessons delivered by teaching staff and online learning forums.

3.2. Participants

Information regarding the study was shared with children, who were then invited to participate in the study. Participation was voluntary. A total of 32 children and youth chose to participate. The average age of participants was 13.5 years, 18 children identified as girls and 14 identified as boys. At the time of the study, all the participants were legally placed at the CYCC. Informed assent was obtained from the younger children and consent from the older children.

3.3. Data generation

To generate data, participants met in small groups, which were facilitated by a counsellor and a social worker, who both work at the centre. The decision to engage staff in facilitating groups was necessary during the initial, stricter levels of lockdown (when the data were generated) as non-essential staff were not allowed entry onto the premises. The first author has a working relationship with both the facilitators and provided information on the study aims and the methods.

To guide the process, each participant was given a booklet with six open-ended questions related to COVID-19 and the lockdown; each question had space allocated for participants to draw and/or write a response. The first question prompted participants to share something about themselves. The questions that followed included:

-

-

How do I understand Covid-19?

-

-

How is Covid-19 affecting my life?

-

-

What does lockdown look and feel like for me?

-

-

What are some of my worries about Covid-19 and being in lockdown?

-

-

What are some of the things that are helping me cope?

Participants were then invited to share verbally in the groups what they had written, and what the drawing meant to them (Angell, Alexander, & Hunt, 2015). This qualitative method, referred to as 'the draw, write and tell method of data generation', foregrounds the voice of the participants and is flexible and sensitive to the context and of the content (Mitchell, Theron, Smith, Stuart, & Campbell, 2011). This method is particularly useful for use with children as it fun and non-threatening; it also gives children time to think through and structure thoughts before sharing, and may also address linguistic difficulties (Backett-Milburn & McKie, 1999). The method is, however, not without criticism, with suggestions that it may undermine children’s ability to adequately communicate their experiences, may be superficial and assumes that drawing is a fun activity for all children (Angell et al., 2015; Backett-Milburn & McKie, 1999). In our research, we gave children the option of drawing and writing or just writing; of the 32 participants, 14 chose not to include any drawings.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data comprised of the textual information generated by participants and were analysed following the six steps to inductive, thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke (2006). This method of analysis is used to identify, analyse and report themes within data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Author 1 reviewed the data, becoming familiar with it and generated the initial codes and possible themes. These were then reviewed and refined by both authors and through a joint process, final themes were then defined and named.

3.5. Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of Leicester (9 April 2020). The Director at CYCC X, acting as legal guardian, granted consent and as mentioned above, informed assent was obtained for children younger than 12 and consent from those over 12.

As well as delivering these fundamental ethical tasks, and aware of our positionality as researchers (both South African by birth, one Indian and one white born during the Apartheid era), our approach to ethics also accounted for four key dimensions accepted as important when delivering research in low resource settings experiencing chronic structural disadvantage (Emanuel, Wendler, Killen, & Grady, 2004; Tangwa, 2017):

-

-

collaborative partnership and research prioritisation – we ensured that the research questions arose from the needs expressed by CYCC X resulting from the immediacy of lockdown

-

-

social value – we aimed to amplify the COVID-19 experiences of a seldom-heard group of children, and our discussion reflects on the implications of our findings for other CYCCs in the context of a global health challenge.

-

-

respect for participants and the communities in which they live – author 1 has a long association with CYCC X and brought this experience to bear in ensuring a respectful approach was maintained throughout the data gathering process. Author 2 visited the CYCC X in 2019 and spent time with the staff team, with the intention of beginning to build a trusted working relationship.

-

-

risk-benefit ratio – our exploratory project aimed to surface the key worries experienced by the participants, and had existing mechanisms in place to ensure they had adequate counselling and other support should significant issues arise.

To ensure trustworthiness of the data, author 1 shared findings from the study with childcare staff and social workers based at CYCC X; this group were in close contact with the children during the lockdown period and had engaged the children in similar conversations throughout the lockdown period. They were able to confirm the consistency of the findings. Time constraints for both children (including a demanding school schedule), staff (supporting online learning together with regular care duties) and ourselves, meant that, at the time of writing this, we were not able to share findings with the children.

We used thick descriptions to describe the context and shared excerpts and images from the participants, ensuring we could begin to interpret the characteristics of each participant’s contribution (Schwandt, 2001).

4. Findings

Findings from the study draws attention both to how the experiences and ways of coping for children in residential care are similar to that reported by children living in family contexts as well as how they differ. Consistent with emerging literature on the impact of Covid-19 on children’s mental health, children in care reported experiencing a range of emotions ranging from frustration, anger and happiness and reported drawing on a host of resources to enable them to cope (Ghosh et al., 2020). Children in care, however, differed with regards to their concerns, which centred primarily on worry for parents and siblings’ well-being.

4.1. Children’s experiences of lockdown

COVID-19 as well as the variations in containment measures have raised concerns about the mental health and well-being of both adults and children (Panchal et al., 2020). For children in care, these feelings are exacerbated, as they are unable to have the normal contact visits with parents or extended family and tend to be under strict supervision, often grouped together with children with a variety of emotional and/or behavioural difficulties (Crawley et al., 2020).

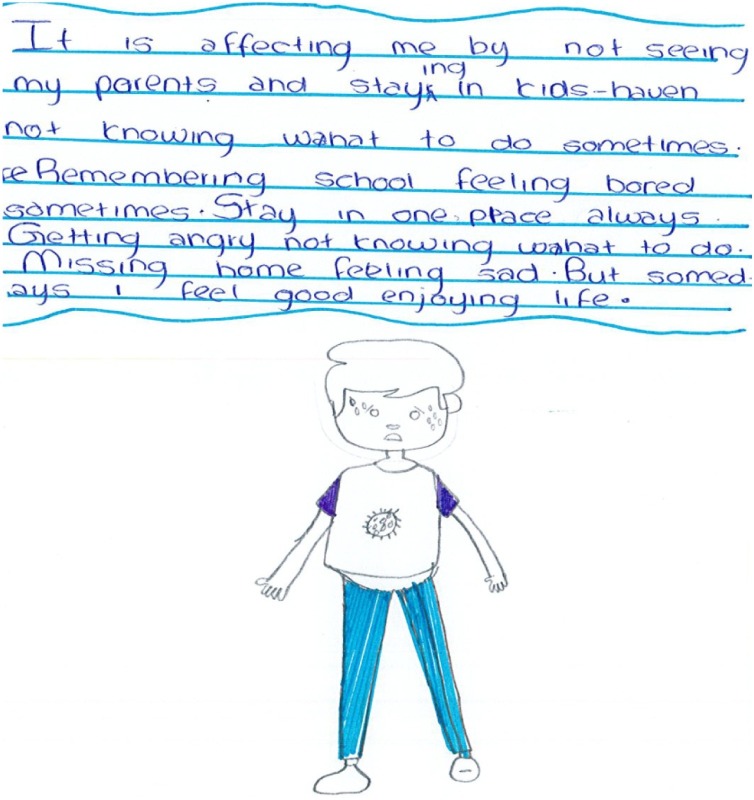

Children at CYCC X similarly appeared to be experiencing a wide range of emotions in response to being under lockdown. Fear, sadness and worry because of the virus, anger and frustration at having to be under lockdown away from family and school, as well as feelings of hopelessness and discomfort were mentioned. One of the participants aptly summarises the range of emotions she experienced during this period, many of which were echoed by other participants. Her list included the following emotions: ‘feel sad, disappointed, trying so hard to put a smile on my face, angry, not going to school, Upset’ (Child 5) (Image 1 ).

Image 1.

Child 5 feelings about Covid-19 and lockdown.

Similarly, Child 3, shared this image (see Image 2 below), which draws attention to the frustration and sadness at being in care, away from family and home, the boredom and anger at having to be away from school and peers, while also enjoying moments of happiness.

Image 2.

Child 3 feelings about Covid-19 and lockdown.

Illustrating the negative psychological impacts of being under lockdown, children used words like ‘I feel hopeless’ (Child 13) and ‘I feel sad’ (Child 8). One of the older youth understood the necessity of lockdown but indicated that it left her feeling depressed, ‘it feels very depressing having to be stuck in one place. For all the right reasons, but at the same time it is very stressful especially for the future plans that had to take place’ (Child 6). For this adolescent, closure of schools meant no contact with peers and raised concerns about the future.

For some children, lockdown felt like being imprisoned, says Child 1 ‘lockdown makes me feel like I’m in prison’, echoing this, Child 26 adds,’ I feel like I am being punished for something I didn’t do. I feel like I’m in prison.’

4.2. Concerns related to COVID-19 and lockdown

4.2.1. Concern for family

Children in care have been removed from unsafe homes, or as in the case of street connected youth, have made a choice to leave family homes because of maltreatment, or have been placed in care because of behavioural problems. As mentioned above, CYCC X had taken a decision to keep all children in care for the duration of the lockdown period; as a way to ensure their safety (from violence and Covid-19 infection) as well as to ensure their well-being in terms of access to food and other resources. For children in care, this meant an indefinite period of no family visits. For many children this lack of family contact was a significant stressor. For example, Child 12 says, ‘corona is effecting my life by taking me away from my family,’ Child 32 says, ‘It’s effecting my life cause now I don’t get to see my family’ and Child 3 says, ‘I feel worried about my parents … what is happening about them and I get worried when I will see them again.’

Many children voiced their concerns for their parents and sibling’s well-being, Child 1 says, ‘Corona is making me be worried and stressed about my family.’ Similarly, Child 30 says, ‘I am not sure if my siblings are really doing okay or not, even with them saying they are, ‘okay’ I am still left wondering if they are.’

Recognising the potential severity of COVID-19, some children feared not seeing family members again. Child 26 says, ‘My family could be infected or could die and I won’t even be aware.’

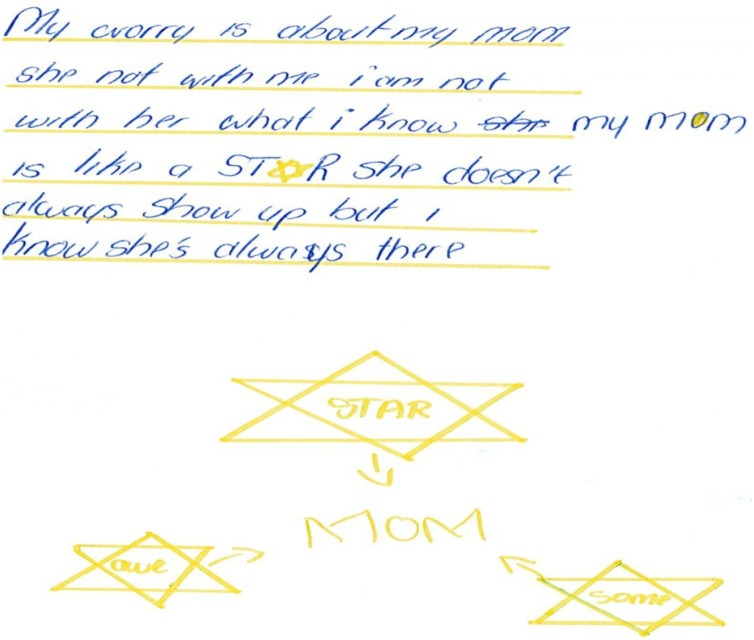

The image (Image 3 ) below by Child 2 and her explanation reflects the complex relationship that children in care have with parents. For Child 2, her concern for and attachment to her mum appears to override her mother’s absence or potential parental neglect. Speaking of her concern for her mum, Child 2 writes, ‘My worry is about my mum, she [is] not with me, I am not with her what I know my mom is like a star she doesn’t always show up but I know she is there.’ Her statement that ‘she doesn’t always show up’ suggests that her mum may not always respond to her needs but her presence is reassuring. As shared above, parental neglect accounts for almost a quarter of admissions into CYCC X.

Image 3.

Child 2 articulates her concern about her mother.

In their concern, children and youth in care demonstrated an awareness of the contextual realities of many of their families as well as the community, Child 12 says, ‘My worries about being in lockdown are that I don’t know what happen to my family and what are they eating…..is my baby sister protected?’ Also expressing concern about a sibling, Child 23 also wonders, ‘How are my siblings?’ These statements suggest that participants are cognisant of the prevalence of child abuse in South Africa and recognise that younger siblings may be at risk.

Similarly, Child 6 says,

‘My worries about being in lockdown is … how are my family and friends during this lockdown, because it seems like people are no more dying from covid-19 their life’s [lives] are more effected from “hunger”. I’m very worried because all the shops are closed and what are my family eating and are they save [safe] from covid-19 or not and hungry?’

In this statement, this young participant exhibits an awareness of the poverty and the resultant hunger that many South Africans are experiencing. She echoes what many commentators have iterated; that is, that the South African economy may not be robust enough to withstand the lockdown and that there is a greater likelihood that people will die from hunger than from Covid-19.

4.2.2. Concern for lost opportunities

Almost all the children expressed concerns about the impact that the lockdown was having on their education and their futures. Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of education for South African children exposed to structural disadvantage; for many education is regarded as a means to escape poverty (Phasha, 2010; Mosavel, Ahmed, Ports, & Simon, 2015; Walker & Mkwanazi, 2015).

Participants expressed worry about not being able to go to school and for not being able to move onto the next grade. For example, Child 16 says, ‘My worries is that I’m not going to school,’ Child 14 says, ‘How am I going to finish my grade?’ and Child 26 echoes this sentiment, saying ‘I can longer go to school when I’m so close to finishing….I may never get a chance to finish my education.’ Tied to this were concerns of falling behind and failing a grade, Child 3 added, ‘I also think about school, when I will go back to school also if I will repeat a grade because I don’t want to repeat.’ These concerns are not unfounded, with child protection agencies asserting that many of the 1.5 billion children currently out of school worldwide will never return to school and will have limited future prospects (Wolfson-Vorster, 2020a).

Referring to the strict regulations that were of necessity imposed by the CYCC, Child 3 and Child 32 both express frustration at not being able to leave the centre and go to school, Child 3 adds, ‘When I will be free again?’ Child 32 asks the same question, ‘When I am going to be free?’

4.2.3. Concern for the Community

Participating children appeared to have an awareness of how the pandemic not only impacted on them and their families, but spoke to wider societal challenges facing many people in South Africa. As mentioned above, these same concerns, about hunger, worsening economic conditions as well as difficulty practising social isolation in small spaces, have dominated discussions of the pandemic in South Africa.

‘Some of my worries is that there are people who don’t have anything to eat and those who need some money because there are those who are selling in the street to make life for their family. So now they don’t have in this lockdown. And I’m worried about my family and how they are surviving….I am worried about the ones that are living on the street. What are they eating, where do they sleep. I am worried about the people who are living in the shacks because it is a small zozo that can occupy three people but now they are six or more.’ (Child 13)

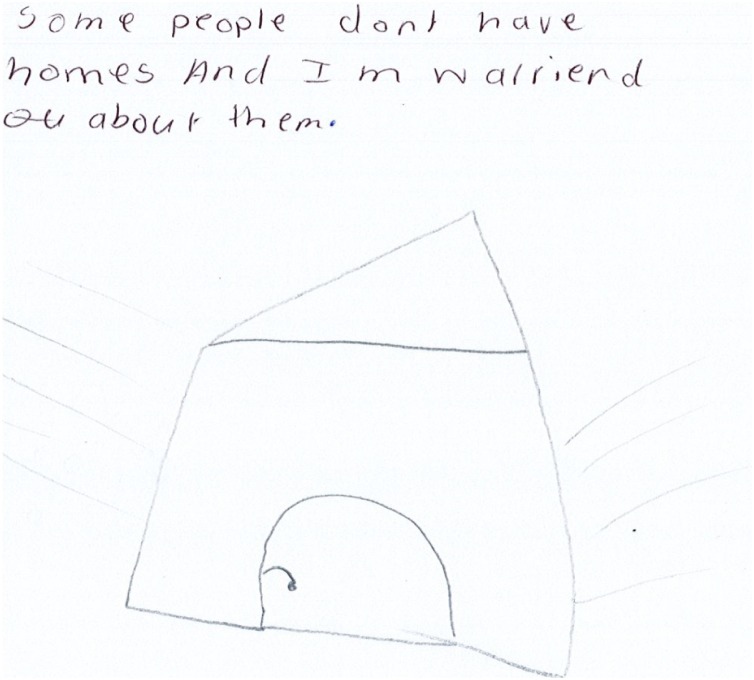

In the image below (see Image 4 ), Child 3 draws attention to people that don’t have homes.

Image 4.

Child 3 expresses concern about those without homes.

4.3. Protective resources enabling children to cope

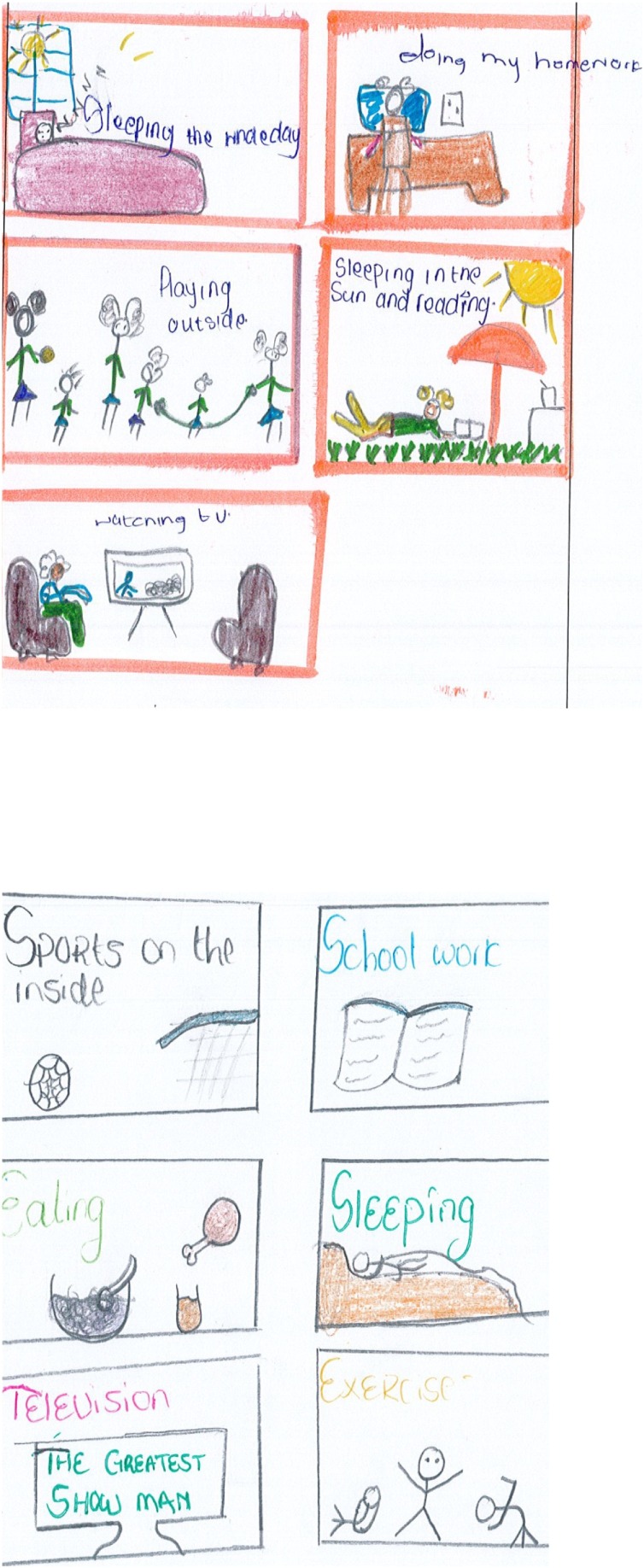

The majority of children drew on internal, self-regulatory mechanisms to help them cope, including exercise, reading, listening to music and watching television. These approaches were accompanied by engaging with others through play and group sports. Some of these resources - like television and radio- were easily accessible for children while in residential care.

Engaging with others through play was especially important for the younger participants, while for some of the older children helping staff with chores and younger children with homework appeared to give them a sense of purpose and stopped them from feeling bored. For example, Child 25 says, ‘keeping myself busy at all times so that I don’t get bored and start complaining. Going to home work class and helping the staff with whatever they need help with.’ Sense of purpose has previously been identified as a potential protective factor in psychological resilience during adolescence (e.g. Wang, Hu, & Yin, 2017).

In addition to these internal mechanisms, structural resources provided by the CYCC enabled children to cope. The ability to access education, through access to the online learning programme, ‘doing my homework online’ (Child 4), alleviated some of the children’s fears of falling behind and also kept them occupied, facilitating coping. It is important to note here that for the majority of children in South Africa accessing education through online forums was not possible (Van der Berg & Spaull, 2020).

The awareness of being safe also helped children cope; ‘We are very safe, we are in our homes and in our shelters because if we were outside we should have been dead or killed’ (Child 9). Child 10 echoes this sentiment saying, ‘By knowing I am safe.’ As above, these statements suggest that participants in care are fully aware of the dangers present in communities; as mentioned above, approximately 45% have had exposure to some form of violence. The structure and support offered by the CYCC enable them to feel safe.

This sense of safety also enabled some children to focus ‘on the positive side of life’ (Child 18). The following images (Images 5 and 6) from participants captures this range of protective, resilience-enabling resources.

Images 5 and 6.

Participants share their protective, resilience-enabling factors.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

COVID-19 has been referred to as an unprecedented event, unparalleled in its impact. In this global reach, it highlights more than any other event in recent times, our global inter-connectedness. However, as witnessed in South Africa and elsewhere, individuals, communities and societies are differentially impacted. In South Africa, the social and economic disruptions caused by the pandemic and associated lockdown, combined with long-term structural social, economic and political inequality, and failures within government have impacted on service delivery, access to resources and availability of supportive networks, the absence of which increases vulnerability and heightens levels of anxiety and stress in children. In this exploratory study we aimed to address the research question: ‘What can the experiences and perspectives of South African children in care during lockdown tell us about the themes we should focus on to improve care moving forward?’ As the findings emerged, we noted that there were a number of domains of concern that reflect the social ecologies in which our participants operated. In spite of being ‘out’ of community contexts, our findings show that children in care situate themselves firmly within their social-ecologies. They continue to express concern for families and for communities (some who may have rejected them). They acknowledged the resources that they have access to while at the CYCC and through their concern for parents, siblings and wider society also acknowledged the prevalence of hunger, violence and food insecurity in South Africa.

For many South African children, pre-existing structural challenges heighten exposure to a multitude of risks. Covid-19 has increased these risks factors. The majority of children admitted into care at CYCC X have been exposed to poverty and child maltreatment. Fernandez et al. (2019) note that so caregivers access to adequate economic and social capital protects children against poverty and environments that may be unsafe. Children from families that are disadvantaged economically, socially and emotionally tend to be over-represented in out of home care (Fernandez et al., 2019). The findings from this study suggest that the experiences of children living in this residential care facility during the lockdown are in many ways the same as that of children living in similarly resourced, in-home contexts. These experiences, however, are not reflective of all children in South Africa, the majority of whom live in under-resourced contexts. Therefore, while the participants in our study had access to regular meals and education and felt safe, this may not have been the case if the CYCC had returned the children to family care. Under these circumstances, being in a nurturing, care facility may buffer children from the numerous challenges posed by unsafe and/or under-resourced contexts.

At the same time, being separated from family members emerged as a primary source of worry, with almost all participants expressing concern about the health, safety and well-being of parents and siblings. The study therefore surfaces a paradox – while being with family is important to the wellbeing of all children, the fundamental importance of safety, food and shelter as protective factors, means this contact with family is not possible during a pandemic.

CYCC X appears to provide an environment that is consistent, stable, and built on supportive relationships. Studies show that access to supportive relationships and a responsive ecology provide a measure of protection in the face of multiple adversities (Collishaw, Gardner, Lawrence Aber, & Cluver, 2016; Mosavel et al., 2015; Ungar, 2011). Many of the children acknowledged the protection and support offered to them by CYCC X, and which enabled them to cope. Participants drew on a range of internal resources to help them cope, which was facilitated by caregivers that were available, access to therapeutic support as well as access to resources, like television, sports, books and online learning forums. Thus, even while in care – often thought of as the last possible resort for vulnerable children - in this protective context, they were also able to access their own internal resources and reach out to support others.

Of significant concern for the participants in our study, was the closure of schools. This experience is consistent with findings emerging from other studies, across diverse contexts. Ghosh et al. (2020) note that being quarantined in homes and institutions presents a bigger psychological burden than that of the actual pandemic; adding that school closures, lack of physical activity and aberrant eating and sleeping habits may potentially promote monotony, distress, impatience, annoyance and varied neuropsychiatric manifestations. Isolation and the absence of routines imposed by schools may also lead to psychological distress as schools provide stability and may be a coping mechanism for some children. In the context of the residential care facility, the psychosocial support offered by schools, takes on further importance in that it represents an additional, external space away from the confines of the facility. Additionally for children at CYCC X absence from school was seen as potentially jeopardising future plans. South African research with youth exposed to structural adversity shows that access to education and the presence of future oriented plans enable positive adaptation in contexts of risk and is regarded as a means to securing a better, more economically stable future (Lundgren & Scheckle, 2019; Theron & Van Rensburg, 2018; Walker & Mkwanazi, 2015).

In the context of an emergency, such as this one, protecting the rights of children in residential care requires collaboration across multiple sectors, including government ministries (Better Care Network, 2020). Masten and Motti-Stefanidi (2020) suggest that every disaster brings with it lessons for future resilience planning at multiple levels. As such, learnings from this experience may be leveraged to repair and transform the child protection sector, strengthening system responses and building resilience.

The findings of our study suggest that it is only through co-ordinated, holistic, and strategically sound collaboration that we will be able to protect children in care in South Africa. This task cannot be the responsibility of individual non-governmental organisations. It requires state departments to be fully invested in the welfare of children, to act strategically in support of organisations, and to be held accountable if and when they fail to uphold the constitutional rights of children. Disappointing leadership and guidance from state departments in South Africa have highlighted the need for emergency response planning and clearer guidelines. To this end, and moving forward, both state social services as well as alternate care services need to be recognised as essential services. Continuity of services as well as reduced bureaucratic gatekeeping need to be ensured to enable residential care facilities to continue providing services, with necessary funding and without unhelpful barriers set up by state departments (Better Care Network, 2020). Given the schooling and mental wellbeing concerns expressed by our participants, state departments (DSD and DBE) need to prioritise the equipment (including personal and protective equipment), facilities (including quarantine facilities) and training needed by residential facilities to ensure children have access to learning and psycho-social support.

Some of the challenges experienced by children during lockdown, particularly regarding concern for family members, suggests a need for creative problem solving by care facilities to ensure that children have continued contact with families. Digital technologies may offer new solutions using ‘free at the point of use’ services for families to stay in touch with CYCCs. Regional or national policy programmes facilitating solar chargers for communication devices in CYCCs, and devices themselves in limited numbers, would overcome this barrier at a relatively low cost.

Beyond this emergency response planning, the pandemic has reinforced the need for broad scale systemic changes, necessary to protect and assist the most vulnerable communities in South Africa. Strengthening economic support for families is essential given the increasing levels of poverty, food insecurity and growing rates of unemployment. Current calls for a universal, unemployment or basic income grant and general increase in child support grants are positive developments in the right direction.

Our findings on the significant role that parents play, even in their absence, suggest a need for positive parenting skills and family strengthening interventions that will ensure that children are cared for in family environments. Combining social support grants that provide a measure of protection against the impacts of poverty with family strengthening interventions promotes greater child and youth development and well-being (Cluver et al., 2016).

Families and communities should be safe spaces for children; the appallingly high prevalence of gender based violence and child abuse demands greater accountability from government and co-ordinated action from all departments, including justice, social development and health. The promotion of social norms that protect against adversity and violence through public education campaigns, legislative approaches that acknowledge and prioritise gender based violations and that develop and implement gender sensitive solutions is necessary (Centre for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), 2019).

Participants' concerns regarding the interruption of their schooling highlighted the centrality of education in nurturing hope for children exposed to adversity. The importance of the schooling system has also been the subject of much discussion in the country throughout the pandemic. The role that education and educational systems have on youth development suggests a need for increased efforts in ensuring that these spaces are fully resourced and accessible. Efforts must be made to ensure that digital poverty is addressed, and that all children have equal access to adequate schooling.

6. Limitations

This study took place under unusual circumstances demanded by a global pandemic. As a result, there are limitations to the conclusions we can reasonably draw, that could be mitigated by future research. Our intention was to capture, in the most systematic way we could, the immediate experiences of our participants during the most intense period of South Africa’s lockdown, and our design reflects this priority. The study has four key limitations to which we draw attention:

-

1

The size of the sample and length of the data-gathering period invite further investigation, in other alternative care settings in South Africa and beyond.

-

2

Qualitative research is dependent in part on the skill and experience of the person gathering the data. We mitigated the risk of poor data quality by ensuring the approach was closely structured and supported by Author 1, and that a common prompt tool was used across the sample.

-

3

The qualitative nature of the study facilitates a rich and trustworthy understanding of the perspectives and experiences of our participants, but should not be read to imply causality.

-

4

In order to increase trustworthiness, our study relied on a well-tested method; arguably future research of this type should seek to take a more Africa(n)-aligned approach to gathering data, which will bring with it additional strengths and some risks.

7. Conclusion

Our study with vulnerable children in care has provided a living example of the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic exposes and exacerbates the inherent structural inequalities that characterise South Africa. This exacerbation of existing inequalities lies at the interface between public health, and societal and systemic structures. COVID-19, devastating in its impact, urges accountability and provides multiple opportunities to learn from and build the capacity and resilience of individual, family, community and societal systems.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible through seed funding from the Leicester Institute of Advanced Studies (LIAS), University of Leicester and the (Research England) Global Challenges Research Fund. We wish to thank our child and youth participants for sharing their knowledge with us as well the Director at CYCC X for granting us permission to conduct the study, and staff CYCC X for their assistance with data generation.

Footnotes

The Residential Care Facilities Group is a group of residential care facilities in Gauteng. During the lockdown period the group has had online meetings twice a month, sharing resources and support.

References

- Allende, K., & Khota, F. (2020, May 26). Caring for children in uncertain times. http://www.jch.org.za/newsArticle.asp?id=136.

- Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action . 2019. Principle 10: Strengthen children’s resilience in humanitarian action. Retrieved from: https://casemanagement.alliancecpha.org/en/child-protection-topics/principle-10-strengthen-childrens-resilience-humanitarian-action. [Google Scholar]

- Angell C., Alexander J., Hunt J.A. Draw, write and tell’: A literature review and methodological development on the ‘draw and write’research method. Journal of Early Childhood Research. 2015;13(1):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Artz L., Meer T., Muller A. Global Perspectives on Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Across the Lifecourse. Springer; 2018. Women’s Exposure to Sexual Violence Across the Life Cycle: An African Perspective; pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Backett-Milburn K., McKie L. A critical appraisal of the draw and write technique. Health Education Research. 1999;14(3):387–398. doi: 10.1093/her/14.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin-Ragaven L. Social dimensions of COVID-19 in South Africa: a neglected element of the treatment plan. Wits Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;2(SI):33. [Google Scholar]

- Bega, S., Smillie, S., & Ajam, K. (2020, May 16). Spike in child abandonments and the physical abuse of youngsters during lockdown 16 IOL. Retrieved from: https://www.iol.co.za/saturday-star/news/spike-in-child-abandonments-and-the-physical-abuse-of-youngsters-during-lockdown-48012964.

- Better Care Network . 2020. Technical Note on the Protection of Children during the Covid- 19 Pandemic: Children and Alternative Care. Retrieved from: https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/particular-threats-to-childrens-care-and-protection/covid-19/alternative-care-and-covid-19/technical-note-on-the-protection-of-children-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-children-and-alternative. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Division of Violence Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta; Georgia: 2019. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 2005. South Africa: Act No. 38 of 2005, Children’s Act. [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S., Gardner F., Lawrence Aber J., Cluver L. Predictors of mental health resilience in children who have been parentally bereaved by AIDS in urban South Africa. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2016;44:719–730. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley E., Loades M., Feder G., Logan S., Redwood S., Macleod J. Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2020;4(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly S. 2020. The History and Achievements of Kids Haven. Internal Report. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel E.J., Wendler D., Killen J., Grady C. What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;189(5):930–937. doi: 10.1086/381709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon D., McGhee K., Davies J., MacLeod F., Clarke S., Sinclair W. Capturing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Nursing. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/24694193.2020.1788346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E., Delfabbro P., Ramia I., Kovacs S. Children returning from care: The challenging circumstances of parents in poverty. Children and Youth Services Review. 2019;97:100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J., Languilaire J.-C., Lawthom R., Nieuwenhuis R., Petts R., Runswick-Cole K. Community, work, and family in times of COVID-19. Community, Work & Family. 2020;23(3):247–252. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2020.1756568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fore H. A wake-up call: COVID-19 and its impact on children’s health and wellbeing. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(e861-2) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman P., van Ijzendoorn M., Sonuga-Barke E. The implications of COVID-19 for the care of children living in residential institutions. The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Dubey M.J., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. Impact of COVID-19 on children: special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatr. 2020;72:226–235. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K., Sambu W. Income poverty, unemployment and social grants. In: Mathews S., Jamieson L., Lake L., Smith C., editors. South African child gauge 2014. Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2014. pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hansungule Z. 2018. Questionable Correction: Independent Oversight of Child and Youth Care Centres in South Africa. APCOF Research Paper Series, Issue 19. Retrieved from: http://apcof.org/wp-content/uploads/no-19-child-and-youth-care-center-by-zita-hansungule-.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Howie S.J., Combrinck C., Roux K., Tshele M., Mokoena G.M., McLeod Palane N. Centre for Evaluation and Assessment; Pretoria: 2017. PIRLS Literacy 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016: South African Children’s Reading Literacy Achievement. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson L. Children and young people’s right to participate in residential care in South Africa. The International Journal of Human Rights. 2017;21(1):89–102. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2016.1248126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loffell J. Developmental Social Welfare and the Child Protection Challenge in South Africa. Practice. 2008;20(2):83–91. doi: 10.1080/09503150802058889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren B., Scheckle E. Hope and future: Youth identity shaping in post Apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2019;24(1):51–61. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2018.1463853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahery P., Jamieson L., Scott K. 1st ed. Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town & National Association of Child and Youth Care Workers; Cape Town, South Africa: 2011. Children’s act guide for child and youth care workers. [Google Scholar]

- Malatji H., Dube N. Experiences and challenges related to residential care and the expression of cultural identity of adolescent boys at a child and youth care centre (cycc) in Johannesburg. Social work/Maatskaplike werk. 2015;53(1) doi: 10.15270/52-2-549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamelani . 2013. Transitional support: The experiences and challenges facing youth transitioning out of state care in the Western Cape. Retrieved from: https://www.mamelani.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Transitional_Support_WC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Manyema M., Richter L.M. Adverse childhood experiences: prevalence and associated factors among South African young adults. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais H. The crisis of waged work and the option of a universal basic income grant for South Africa. Globalizations. 2020;17(2):352–379. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S., Motti-Stefanidi F. Multisystem Resilience for Children and Youth in Disaster: Reflections in the Context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, S., Jamieson, L., & Makola, L. (2020, May 26). Our COVID-19 strategy must include measures to reduce violence against women and children 26 IOL. Retrieved from: https://www.iol.co.za/news/opinion/our-covid-19-strategy-must-include-measures-to-reduce-violence-against-women-and-children-48510271.

- Meinck M., Cluver L.D., Boyes M.E. Household illness, poverty and physical and emotional child abuse victimisation: findings from South Africa’s first prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1792-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meintjes H., Moses S., Berry L., Mampane R. Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town & Centre for the Study of AIDS, University of Pretoria; Cape Town: 2007. Home truths: The phenomenon of residential care for children in a time of AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C., Theron L., Smith A., Stuart J., Campbell Z. Picturing research. Brill Sense; 2011. Drawings as research method; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgopha M.S. University of Johannesburg; 2019. Resilience Development of Former Street Children on the streets, in Residential Care and Beyond Care. Unpublished Masters Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Mosavel M., Ahmed R., Ports K., Simon C. South African urban youth narratives: Resilience within a community. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2015;20(2):245–255. doi: 10.1080/026738843.2013.785439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés Mireia, Morales Alexandra, Delvecchio Elisa, Mazzeschi Claudia, Espada Jose. 2020. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Orgera, K., Cox, C., Garfield, R., Hamel, L., et al. (2020, April 21). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/.

- Phasha T. Educational resilience among African survivors of child sexual abuse in South Africa. Journal of Black Studies. 2010;40(6):1234–1253. doi: 10.1177/0021934708327693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman Potts, O’Donnell Thompson, Shah Oertelt-Prigione, Gelder van. Center for Global Development; Washington, DC: 2020. Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children. CGD Working Paper 528. Retrieved from: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/pandemics-and-violence-against-women-and-children. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid J., Patel L. The interaction of local and international child welfare agendas: A South African case. International Social Work. 2014;59(2):246–255. doi: 10.1177/0020872813516477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt T.A. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. 2020. What risks does COVID-19 pose to society in the long-term? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/what-risks-does-covid-19-pose-to-society-in-the-long-term/. Accessed 23 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sekyere E., Bohler-Muller N., Hongoro C., Makoae M. Wilson Centre; 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 in South Africa. Africa Program Occasional Paper. www.wilsoncenter.org/africa. [Google Scholar]

- Spaull N., Ardington C., Bassier I., Bhorat H., Bridgman G., Brophy T., Budlender J., Burger R., Burger R., Carel D., Casale D., Christian C., Daniels R., Ingle K., Jain R., Kerr A., Kohler T., Makaluza N., Maughan-Brown B., Mpeta B., Nkonki, L, Nwosi C.O., Oyenubi A., Patel L., Posel D., Ranchhod V., Rensburg R., Rogan M., Rossouw L., Skinner C., Smith A., Van der Berg S., van Schalwyk C., Wills G., Zizzamia R. 2020. National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) ? Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) Overview and Findings: NIDS-CRAM Synthesis Report Wave 1. Retrieved from: https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Spaull-et-al.-NIDS-CRAM-Wave-1-Synthesis-Report-Overview-and-Findings-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli M., Lionetti F., Pastore M., Fasolo M. Parents’ Stress and Children’s Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangwa G.B. Giving voice to African thought in medical research ethics. Theoretical medicine and bioethics. 2017;38(2):101–110. doi: 10.1007/s11017-017-9402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thebus S. Cape Argus; 2020. Almost 80% of citizens eligible for Social Relief of Distress Grants kept waiting’. 20 June 2020. https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/almost-80-of-citizens-eligible-for-social-relief-of-distress-grants-kept-waiting-51211564. [Google Scholar]

- Theron L., Van Rensburg A. Resilience over time: Learning from school- attending adolescents living in conditions of structural inequality. Journal of Adolescence. 2018;67:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titi, N., & Jamieson, L. (2020, June 7). Include children's voice's on issues that concern them. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/news-include-childrens-voices-on-issues-that-concern-them.

- Tshishonga N. The Legacy of Apartheid on Democracy and Citizenship in Post- Apartheid South Africa: An Inclusionary and Exclusionary binary? AFRIKA: Journal of Politics. Economics and Society. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.31920/2075-6534. p.167-191/2019/9n1a8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bruwaene L., Mustafa F., Cloete J., Goga A., Green R.J. What are we doing to the children of South Africa under the guise of COVID-19 lockdown? SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2020;110(7):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Berg S., Spaull N. Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP) Stellenbosch University; Stellenbosch: 2020. Counting the Cost: COVID-19 school closures in South Africa & its impacts on children. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu M., Yin X. Positive academic emotions and psychological resilience among rural-to-urban migrant adolescents in China. Social Behaviour and Personality. 2017;45(10):1665–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Walker M., Mkwanazi F. Challenges in accessing higher education: A case study of marginalised young people in one South African informal settlement. International Journal of Educational Development. 2015;40:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson-Vorster, R. (2020, May 5). The challenge of safety and some potential solutions. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-05-05-part-two-the-challenge-of-safety-and-some-potential-solutions/.

- Wolfson-Vorster, R. (2020, July 22). Children’s rights, a silent casualty of Covid-19. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-07-22-childrens-rights-a-silent-casualty-of-covid-19/.

- World Bank . 2018. Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: An assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities. Retrieved from: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/pdf/124521-REV-OUO-South-Africa-Poverty-and-Inequality-Assessment-Report-2018-FINAL-WEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zizzamia R., Schotte S., Leibbrandt M. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2019. Snakes and ladders and loaded dice: poverty dynamics and inequality in South Africa between 2008–2017.http://localhost:8080/handle/11090/950 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Managing Psychological Distress in Children and Adolescents Following the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Cooperative Approach. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1037/tra0000754. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]