Abstract

Background

In the case of immigrant health and wellness, data are the key limiting factor, where comprehensive national knowledge on immigrant health and health service utilisation is limited. New data and data silos are an inherent response to the increase in technology in the collection and storage of data. The Health Data Cooperative (HDC) model allows members to contribute, store, and manage their health-related information, and members are the rightful data owners and decision-makers to data sharing (e g. research communities, commercial entities, government bodies).

Objective

This review attempts to scope the literature on HDC and fulfill the following objectives: 1) identify and describe the type of literature that is available on the HDC model; 2) describe the key themes related to HDCs; and 3) describe the benefits and challenges related to the HDC model.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the five-stage framework outlined by Arskey and O’Malley to systematically map literature on HDCs using two search streams: 1) a database and grey literature search; and 2) an internet search. We included all English records that discussed health data cooperative and related key terms. We used a thematic analysis to collate information into comprehensive themes.

Results

Through a comprehensive screening process, we found 22 database and grey literature records, and 13 Internet search records. Three major themes that are important to stakeholders include data ownership, data security, and data flow and infrastructure.

Conclusions

The results of this study are an informative first step to the study of the HDC model, or an establishment of a HDC in immigrant communities.

Key words

community health, health data, cooperative, and citizen data empowermen

Introduction

Canada is becoming an increasingly multicultural society, welcoming 250,000 immigrants each year, and composing 20% of the Canadian population [1]. Immigrant communities add to the economic, labor, and cultural diversity of Canada. An immigrant, as defined by Statistics Canada, is any person residing in Canada who was born outside of the country, excluding temporary foreign workers, Canadian citizens born outside Canada, and those with student working visas [2]. Comprehensive national knowledge on immigrant health and health service utilisation is limited to allow for meaningful comparisons either within immigrant sub-groups or between immigrants and the native-born population [3]. Key knowledge gaps in immigrant health include long-term health outcomes, preventable conditions, and chronic disease outcomes, especially amongst subgroups such as refugee and non-European immigrants [4]. Immigrants comprise relatively small portions of the population given that approximately 18% of the Canadian population were born outside of the country. However, meaningful comparisons and generalisable results require large-scale studies that sample an effective number of immigrants, which is often not done with studies using statistics Canada data sets of national population health surveys. This includes the National Population Health Survey (NPHS), Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), the General Social Survey (GSS) [5,6].

In the case of immigrant health, data is the key limiting factor, where comprehensive national knowledge on immigrant health and health service utilisation is limited. There has been a push to increase available immigrant data through linking Canadian immigrant databases to administrative databases in order to explore patterns of mortality, cancer incidence, hospitalizations, physician claims, prescription medication use, and socio-demographic factors of health [4]. However, there is a lack of immigrant data to carry out meaningful comparisons either within immigrant sub-groups or between immigrants and the native-born population. Indeed, to understand how the process of immigration and acculturation affect health, data specifically on immigrant are needed. Further, immigrant groups have culturally based understandings of health and illness, or differences in definition of appropriate ways to treat illness. Health data that is sensitive to these differences would allow for a deeper understanding of health in this group, and may prove fruitful for public health research, policy, and tailored treatments [7].

'Health Data Cooperatives': Are they the solution?

The Health data co-operative (HDC) model is that of a health data bank that is established as an approach to make health data available to society. The cooperative members can contribute to, store, and manage their health-related information and are the rightful data owners and decision-makers to data sharing (e g. research communities, commercial entities, government bodies). Individuals and the community at large may profit from the value of the data both financially and/or through in-kind contributions by providing access to the data to health-related establishments, including research organisations and government services. Combining the HDC members’ demographic, socioeconomic and lifestyle information through a community owned HDC is expected to create tremendous potential for community mobilisation and empowerment [8].

Further, new data and data silos are an inherent response to the increase in technology. For example, gene sequencing gives us access to personal information that may inform the effectiveness of drugs, and health risk factors to certain disease. Further, with the rise of smartphones, there are more than 40,000 health applications that allow for longitudinal monitoring of health without a visit to the doctor’s office. These examples, along with physician offices, hospitals, and laboratories create data silos, where the data becomes isolated in a physically, judicially, or intellectual defined area, and is unavailable for integration across multiple platforms. This result is a lack of autonomy and empowerment in the control of data by citizens, and unnecessary costs by the healthcare systems due to the inaccessibility of this data for analysis and research. This can be especially useful for under-represented population such as immigrants [9].

A health data cooperative is a collective where health related data are integrated, stored, used, and shared under the control of the cooperative members. The brackets in the following examples simply show the type of data a potential cooperative can host, along with potential stakeholders who can use the data. Most HDCs follow a similar structure that starts with 1) members who are any persons who wish to join a cooperative and contribute their data (e.g. health condition, lab results, hospital admission information, 23andMe, data generated from apps, doctor offices, clinic visits); 2) data storage safe space; 3) data sharing (e.g. authorities, doctors, research, patient group) [10]. The HDC model has been common in Europe, with the establishment of the Federation of National HDCs. This federation shares a common IT structure and common data storage. Further, the federation benefits from political support from Swiss stakeholders and truly encapsulates all that HDCs stand for, including being citizen-owned and citizen-centered and secure in storage and management of data [10].

Research Objectives

The need for immigrant groups to contribute to an HDC model is an important target for public health research. The integration of and access to immigrant specific health data can empower individuals to better manage their health, help contribute to the care of family and friends, help professionals commission the most effective and efficient interventions to benefit the community, allow researchers to develop next generation medicine, and enable the innovation of health technology [10].

Given the importance of data in immigrant health research, it is imperative to scope the literature to understand the complexities of HDC at the national and international level. To systematically map the available literature on the topic of HDCs, the current scoping review will aim to: 1) identify and describe the type of literature that is available on the HDC model; 2) describe the key themes related to HDCs; and 3) describe the benefits and challenges of the HDC model. This scoping review will serve to inform the next stages of research and community engagement to develop a community-based health data cooperative in immigrant communities in Canada. To our knowledge, this is the first review undertaken to synthesize HDC literature.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to systematically map and synthesize the information available on HDCs utilising the reporting guidelines of the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA- ScR) [11] (Supplementary Appendix 1). Further, we followed the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley in their methodological paper on scoping reviews [12]. In their paper, the authors discuss the purpose of scoping reviews as an attempt to examine the extent, range, and nature of the research question, without describing the findings of the studies in detail or doing an assessment of quality. The same approach is taken with this review, using the Arksey and O’Malley five-stage framework.

Stage 1. Identifying the research question

An effective scoping review requires a research question situated within a specific area, but it must also remain broad so as not to exclude potentially useful literature. For this review, we posed the following non-limiting questions: 1) what are the major themes associated with HDCs; and 2) what are the benefits and challenges related to the HDC model.

Stage 2. Identifying relevant studies

Academic published literature searches were conducted using bibliographic databases presented in Table 1 to identify relevant records. An experienced librarian (MV), oversaw the development and execution of the database search strategies, which included a predefined list of keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms (see Table 1) (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy). For grey literature, our search strategy included electronic institutional repositories, Canadian and international professional and government websites, online literature sites, and a manual review of reference lists of relevant publications (see Table 2).

Table 1: Keyword MeSH terms used for search in databases.

| Keywords for health data: |

|---|

|

|

| “Personal Health Record*”[Keyword]; PHR [Keyword]; Data [Keyword]; “data set* [Keyword]; databank [Keyword]; “data bank” [Keyword]; Health [Keyword, MeSH]; Crowd-sourced [Keyword]; crowdsourcing [Keyword, MeSH]; “health trust” [Keyword]; “health data [Keyword]; “Electronic Health Record*” [Keyword]; EHR [Keyword]; “Health Information Exchange *” [Keyword] |

| Keywords for cooperative: |

|

|

| “data cooperative” [Keyword]; Cooperative* [Keyword]; “cooperative business model*” [Keyword]; “cooperative model*” [Keyword]; Citizen-generated [Keyword]; consumer participation [MeSH]; client-generated [Keyword]; people-generated [Keyword]; public-generated [Keyword]; Citizen-driven [Keyword]; client-driven [Keyword]; people-drive [Keyword]; public-driven [Keyword]; citizen-owned [Keyword]; citizen-controlled [Keyword]; “citizen science” [Keyword]; citizen-centric [Keyword]; client-centric [Keyword]; person-centric [Keyword]; people-centric [Keyword]; “citizen empowerment” [Keyword]; “client empowerment” [Keyword]; “people empowerment” [Keyword]; “public empowerment” [Keyword]; Citizen* [Keyword]; client* [Keyword]; public [Keyword]; person* [Keyword] persons [MeSH]; Empowerment [Keyword]; power (psychology) [MeSH]; self-empowerment [Keyword]; Ownership [Keyword, MeSH] |

Table 2: Database search list.

|

Health sciences:

Social sciences:

Business:

Multi-disciplinary:

Political science:

Academic-focused search engines:

|

Repositories/theses:

Health sciences:

Social sciences:

Other:

|

We also conducted a literature search using the three most popular search engines, Google [13], Yahoo! [14], and Bing [15] as these search engines represent more than 96.4% of all search engines worldwide. In addition, meta search engines that blend Web results from Google, Yahoo and Bing, namely MetaCrawler [16] and Monster Crawler [17] were consulted as well. The Internet was used both to identify relevant Web-based information on HDCs and to identify references to non-Web-based information. Our Web search included all relevant webpages from government and non-government organisations, news sites, blogs, discussion boards, social media platforms etc. We executed searches using the following keyword strings: (1) health data cooperative, (2) patient data cooperative and (3) personal health records. Adhering to the recommended search methodology of the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI, 2011), only the first ten pages of the search were utilised for screening. Search results were downloaded and managed in EndNote software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA).

Stage 3. Study Selection

We limited studies to those published in the English language, with no publication date limits. For the grey literature and database search, after removal of duplicates, IN and HN reviewed titles and abstracts for each paper or document for inclusion. Abstracts were classified as relevant, potentially relevant or not relevant to HDCs. Relevant records were those that directly discussed the HDC model or health data, data sharing, stakeholder engagement in data, and data ownership. Records were excluded if they did not discuss any of the concepts above. Abstracts that do not provide enough information on outcomes to determine eligibility were included for further review. Full texts were obtained of the abstracts that met eligibility criteria and were read, reviewed and re-examined for relevance. Two researchers reviewed the full text of the remaining papers to determine eligibility using the same criteria listed above. If no agreement was reached between the two researchers, TCT arbitrated.

Owing to the dynamic nature of the Internet, the screening and full review of webpages identified in the internet search was conducted concurrently. NH performed the first search string, archiving the list of the first ten pages (i.e. Web address, page title, brief description and date searched) and classified each as potentially useful or not useful based on the same criteria listed above for the database and grey literature search. The reviewer then opened all pages considered potentially useful, archived each full page and, should the page contain information about an HDC, classified that tool as eligible or ineligible for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion were recorded. The second reviewer (IN) then independently opened the archives created by the primary reviewer and assess random selections of ten percent of the websites classified by the primary reviewer as eligible and ten percent of those classified as ineligible. The second reviewer also archived the full page of each website opened for assessment (i.e., included and excluded) in case the content had been modified since the primary reviewer undertook screening and full review. If no agreement was reached between the two researchers, TCT arbitrated.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

Information was extracted on the citation, study location, study objective, the health-data-related variable, how the cooperative was established, the main outcome variables, how the outcome variables were measured, and benefits and challenges of HDC. Further, due to the scoping nature of this review, additional descriptive information was collected for selected records including country of origin, author affiliation, and target audience. Two reviewers (IN and NH) independently carried out the data extraction, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarising and reporting the Results

To explore our first research question, we conducted a content analyses of the abstracted data from the records to discover, and generated themes that were adjusted iteratively. For our second research question, the abstracted information on benefits and challenges related to HDC models was stratified by these themes (Tables 3 & 4).

Table 3: Descriptive data and major themes of included studies.

| Author | Year | Location | Publication Type | Author affiliation, Target audience | Major themes related to HDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DATABASE SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| Contreras et al. | 2018 | UK | Letter to editor | Academic, Academia |

|

| Grumbach et al. | 2014 | USA | Research Article | Academic, Academia |

|

| Hafen et al. | 2014 | Switzerland | Research Article | Academic, Academia/policy |

|

| Mahlmann et al. | 2018 | Switzerland | Research Article | Academic, Academia /policy/Public health workers |

|

| Mikk et al. | 2017 | USA | Commentary | Academic, Academia |

|

| Tracy et al. | 2004 | Canada | Research Article | Academic, Academia |

|

| Van Roessel et al. | 2018 | Switzerland | Research Article | Academic, Academia/policy |

|

| Vayena et al. | 2017 | Switzerland | Review | Academic, Academia/Policy /Public health workers |

|

| Montgomery J. | 2017 | USA | Review | Academic, Academia/Policy /Public health workers |

|

| Blasimme et al. | 2018 | Netherland | Commentary | Academic, Academia/Policy /Public Health workers |

|

| Dorey et al. | 2018 | Netherland | Research Article | Academic, Academia, Policy, Public Health workers |

|

| King et al. | 2016 | USA | Research Article | Non-academic, policy |

|

| Torres et al. | 2014 | USA | Research Article | Academic, Policy |

|

| Allen et al. | 2014 | USA | Case Study | Non-academic, Policy |

|

|

| |||||

| GREY LITERATURE SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| Denise et al. | 2012 | USA | Policy report | Academic, Policy |

|

| Nadeau, E.G. | 2010 | USA | Report | Academic, Academia |

|

| Future Care Capital | 2017 | UK | Company Report | Non-academic, Policy |

|

| Ken, T. | 2015 | USA | News article | Academic, Academia |

|

| Website Name, URL | Location | Purpose of Website | Private or Academic | Themes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTERNET SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| A healthcare Startup to provide patient perspective adopts co-op model, https://medcitynews.com/2018/04/healthcare-startup-provide-patient-perspective-adopts-co-op-model/ | Europe | News | Private |

|

|

| Are digital data co-ops an alternative to the commercialisation of health? https://thisisnotasociology.blog/2017/02/27/are-digital-data-co-ops-an-alternative-to-the-commercialisation-of-health | USA | Blog | Private |

|

|

| Data Cooperatives - P2P Foundation, http://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Data_Cooperatives | Europe | Research | Academic |

|

|

| Holland Health Data Cooperative | LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/company/holland-health-data-cooperativ | Europe | Corporate | Private |

|

|

| Swiss Data alliance, https://swiss-data-alliance.squarespace.com | Europe | Presentation |

|

||

| MIDATA.COOPs – Personal (Health) Data Cooperatives, https://www.midata.coop/ | Europe | Corporate | Private |

|

|

| Patient Ownership creating the business Environment http://www.ourhdc.com/files/77395669.pdf | USA | Corporate | Private |

|

|

| The future of your health data, http://maneeshjuneja.com/blog/2014/2/12/the-future-of-your-health-data | USA | Blog | Private |

|

|

| The Personal Data Economy – A Cooperative Approach - Inspire2Live, http://inspire2live.org/wp-content/uploads/10.-Ernst-Hafen-Personal-Data-Economy-a-cooperative-approach.pdf | Europe | Research | Academic |

|

|

| This co-op lets patients monetize their own health data - Fast Company, https://www.fastcompany.com/90207550/this-co-op-lets-patients-monetize-their-own-health-data | USA | News | Private |

|

|

| Towards a European Ecosystem for Healthcare Data – Digital, https://digitalenlightenment.org/system/files/def_healthcare_data_management_report_oct2017_v3.5.pdf | Europe | Research | Academic |

|

|

| Data Commons Cooperative, https://datacommons.coop/ | Australia | Corporate | Private |

|

|

| Digital Health CRC – Home, https://www.digitalhealthcrc.com/ | USA | Corporate | Private |

|

|

Table 4: Reported benefits and challenges of the HDC model.

| Author | Benefits | Challenges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DATABASE SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| Contreras et al. 2018 |

|

|

|||

| Grumbach et al. 2009 |

|

|

|||

| Hafen et al. 2004 |

|

|

|||

| Mahlmann et al. 2017 |

|

|

|||

| Mikk et al. 2018 |

|

|

|||

| Tracy et al. 2004 |

|

|

|||

| Van Roessel et al. 2017 |

|

|

|||

| Montgomery J. 2017 |

|

||||

| Blasimme et al. 2018 |

|

|

|||

| Dorey et al. 2018 |

|

||||

| King et al. 2016 |

|

|

|||

| Torres et al. 2014 |

|

|

|||

| Allen et al. 2014 |

|

||||

|

| |||||

| GREY LITERATURE SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| Love et al. 2012 |

|

||||

| Nadeau, E.G. 2010 |

|

|

|||

| Hartley et al. 2014 |

|

|

|||

| Hafen E. 2014 |

|

|

|||

| International Health Cooperative Organization, 2018 |

|

|

|||

| Craddock et al. 2004 |

|

||||

| Naylor et al. 2017 |

|

|

|||

| Terry K. 2015 |

|

|

|||

|

| |||||

| INTERNET SEARCH | |||||

|

| |||||

| A healthcare Startup to provide patient perspective adopts co-op model, https://medcitynews.com/2018/04/healthcare-startup-provide-patient-perspective-adopts-co-op-model |

|

|

|||

| Are digital data co-ops an alternative to the commercialisation of health? https://thisisnotasociology.blog/2017/02/27/are-digital-data-co-ops-an-alternative-to-the-commercialisation-of-health/ |

|

|

|||

| Data Cooperatives - P2P Foundation |

|

|

|||

| Holland Health Data CooperativE, LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/holland-health-data-cooperative |

|

||||

| midata.coop - Swiss Data Alliance |

|

||||

| MIDATA.COOPs – Personal (Health) Data Cooperatives https://www.midata.coop |

|

||||

| Patient Ownership creating the business environment http://www.ourhdc.com/files/77395669.pdf |

|

||||

| The future of your health data http://maneeshjuneja.com/blog/2014/2/12/the-future-of-your-health-data |

|

||||

| The Personal Data Economy – A Cooperative Approach - Inspire2Live http://inspire2live.org/wp-content/uploads/10.-Ernst-Hafen-Personal-Data-Economy-a-cooperative-approach.pdf |

|

||||

| This co-op lets patients monetize their own health data - Fast Company https://www.fastcompany.com/90207550/this-co-op-lets-patients-monetize-their-own-health-data |

|

|

|||

| Towards a European Ecosystem for Healthcare Data – Digital https://digitalenlightenment.org/system/files/def_healthcare_data_management_report_oct2017_v3.5.pdf |

|

|

|||

| Data Commons Cooperative https://datacommons.coop/ |

|

||||

| Digital Health CRC - Home https://www.digitalhealthcrc.com/ |

|

||||

Results & Discussions

We present our results separately for our two research streams: 1) academic database and grey literature search; and 2) internet search. We start by discussing the descriptive characteristics of the records found by these two search streams. Next, the benefits and challenges of HDCs are discussed in the context of three unifying themes that have emerged from the data: 1) data ownership and control; 2) data security; and 3) data flow and infrastructure.

Search Results

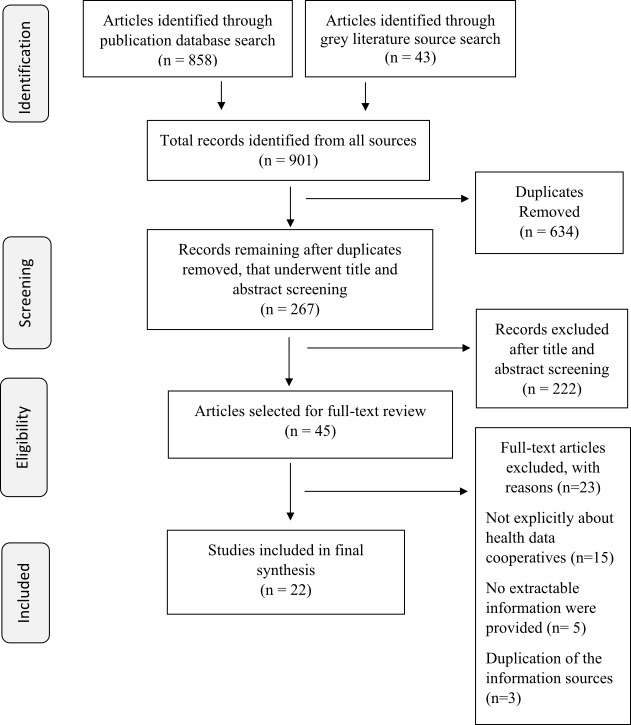

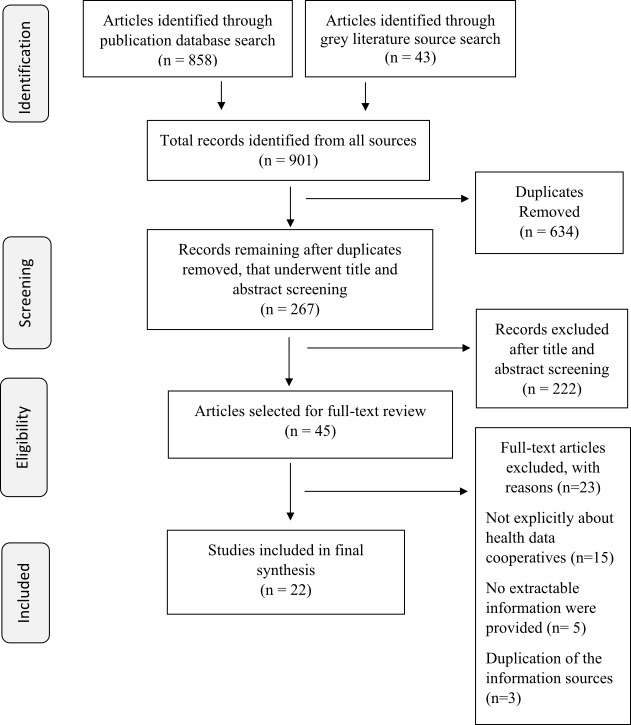

Our database and grey literature search yielded nine hundred and one records, which underwent two levels of screening, first being title and abstract screening and the second being a full text reading, to be included in the final synthesis. The final number of records that were read in detail for data abstraction was twenty-two (Figure 1). For the internet search, we initially identified eight hundred and seventy webpages across the multiple search engines. After the removal of duplicates (either internal, or external corresponding with the database and grey literature search) and a screening of the landing-page for the inclusion and exclusion criteria, thirteen webpages were included in the final analysis (Figure 2).

PRISMA Flow diagram for search of health data co-op literature using published and grey literature databases.

PRISMA flow diagram for search of health data co-op literature through Internet scan.

Study Characteristics

Of the twenty-two records identified in the initial search stream, eight were grey literature records, and fourteen were academic literature published in journals. Of these twenty-two, no records were published before the year 2000, whereas records increased after the year 2014. This is expected as HDC as a topic is relatively unexplored, and technological advances leading to increased data will rightly increase the interest in study of the HDC model. Only two records were written by authors with a non-academic affiliation. Much of the target audience seems to be academia, policy, and public health workers, or simply for academia. The majority of the records originated from the United States, with Europe in second place. Only one record was identified from Canada (Table 5).

Table 5: Descriptive characteristics of health data co-operative literature identified through published and grey literature search.

| All records (Grey, database, and web search) | Grey literature | Academic literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 22 | (n=8) | (n=14) | ||

|

| ||||

| Publication date | ||||

| Earlier than 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2000 - 2013 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| 2014 - 2016 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| 2017 | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| 2018 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Author affiliation | ||||

| Academic | 16 | 4 | 12 | |

| Non-academic | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Study Location | ||||

| Canada | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| US | 11 | 4 | 6 | |

| Switzerland | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Netherlands | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| UK | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Target Audience | ||||

| Academia | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Policy | 9 | 4 | 3 | |

| Academia, policy | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| Academia, policy, public health workers | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

Of the thirteen internet search webpages identified, nine were of a private nature (e.g. blogs, news sites, opinion pieces, corporate sites), and four were of an academic nature (authors were affiliated with an educational institution) (Table 6). The main purposes of these webpages included: 1) homepages of the sites for HDC companies; 2) academic research on the HDC model, such as conference presentations or professional opinion pieces. A significant number of the private webpages were for lay audiences, whereas all the academic records were for academic audiences. Most of the private webpages originated from the United States and Europe, with none being from Canada. All academic webpages were from Europe.

Table 6: Descriptive characteristics of health data co-operative literature identified through Internet scan.

| All Records | Private | Academic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=13) | (n=9) | (n=4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Purpose of Website | ||||

| Research | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Corporate | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Blog | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| News | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Target Audience | ||||

| Professionals | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Academic | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| Lay | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| Location | ||||

| US | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Canada | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Australia | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Europe | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

Major Themes and Benefits and Challenges of HDC

The HDC model seems to fill significant gaps in health data, health research, and community health. All records identify in their content that HDCs are citizen owned and the equal property of members, where the model aims to enable meaningful collaboration and facilitate a transformation of community health data [8]. The records point to integrations and merging of new types of data (i.e. lifestyle data, quantified self-movement, demographic characteristic, genetic data) that can drive improvements in health and healthcare by increasing the accuracy, accessibility, and utility of patient information [18]. Through thematic analysis, three major themes capture the data available on HDCs: 1) Data ownership and control; 2) Data security; and 3) Data flow and infrastructure. The benefits and challenged are discussed within these themes.

Data control and ownership

The grey literature and database search records emphasised the benefits of control that participants will have over their health data. HDCs can operate with minimal costs and without charging their participants, since the valuable nature of the data can be invested in different industries by the participants to generate profits [18,19] . This transaction can involve multiple stakeholders including primary care physicians, beneficiaries, community members, health departments, social services, and universities. Some HDC models are able to provide and gain consent electronically and build a democratic structure, which establishes a link between control and ownership [20,21]. Ideally, participants of the co-operative can have control of data access, data use, and governance. Data control, in this case, is conducive to transparency, accountability, and trust [20,22]. The web search results looked at data ownership and control from a practical perspective, since most records were from HDC companies, mainly opinions or news blogs. Here, the HDC corporations not only give patients control of their data, but also allow them to connect and pitch to interested stakeholders. Further, there seems to be a big push from private cooperatives to take control of data away from corporations and put it back into the hands of people [23,24].

Negative aspects of data control and ownership were focused on the political and bureaucratic hurdles to truly make data belong to participants. This includes: first, establishing legal precedence, where health information as a private property of patients is hard to justify based on traditional labour theory of ownership [25-28] . Second, the HDC model would need to establish connections within government agencies, which may risk the privacy of participants if robust data governance is not in place [19,23]. For example, HDCs in countries hosting public healthcare systems may need to establish health data sharing procedures that follow the countries laws and policies. The web search results took a practical and patient-centered approach to these issues. The records show there is an inherent variability in a community’s vision on how they want to use the data within the cooperative. This variability can be in who has access to the data, who is the data controller, and who outlines the data sharing agreements. This can lead to distrust, lack of respect, and insufficient patient control of the process [22,29,30].

Data security

Data security was equally a strength of the HDC model as much as it was a weakness. Briefly, the grey and database literature results found that HDC models are able to securely store data from multiple platforms within secure servers and cloud computing. This not only provides a financially sound solution but offers an opportunity to collect data that is comparable. For example, the creation and management of a single server to hold information can be designed such that the information is ready-to-use by interested stakeholders [31]. However, there are concerns that no technology exists thus far that can absolutely guarantee trust, transparency, and data security [32] . Although a singular space to store data provides its benefits, it is also open to security threats [33,34]. Insufficient transparency may discourage patients from entering a cooperative due to the fear of an anonymity breach.

The web results show the use of government regulatory bodies and governance structures that improve data security and transparency related to access and control of patient data, which can legitimise the HDC operation. However, considering large data repositories and their value in the market, cyber-attacks are a real threat [28,35]. This is especially true due to the ability of many cooperatives to access aspects of data through multiple modalities, including phone applications. As the access points to data repositories increase, so do security threats, and the potential costs to secure such repositories [36,37]. Indeed, to ensure data security, the HDC models must establish access and privacy standards that are communicated to HDC members and that may need to be regulated by not only good governance structures, but also independent government regulatory bodies [22].

Data flow and infrastructure

Records discussed data flow and infrastructure of the HDC model on multiple levels. Grey and database literature discuss the advantages of HDC in that they can create longitudinal health data from various care settings, which can be accessed via mobile applications [38]. Data integration is a highly cited strength of the HDC model in both search streams. Integration allows the use of data from multiple modalities, reducing the costs of gathering and third-party consent. Cloud computing would then allow access to the data at anytime [19,20,39]. The web results break down the process of data collection and integration. Patients can collect, store, and manage data that is lifestyle (e.g. running times, blood pressures, sleep time, number of steps taken in a day) or medical (e.g. lab results, genetic information) in nature and can input it using a simple interface on either a phone or computer. The data is then used by interested stakeholders and invested into projects that will benefit the community of patients [40-42].

The challenges to the data flow and infrastructure of the HDC include clashes with the socio-political system in the host country. For example, it is difficult to know the fate of a HDC in a publicly funded healthcare system [43]. Further, the HDC may function better with the patient population representing homogenous strata, which may include participants with similar disease profiles and risk factors, or similar demographic characteristics. If this is not the case, certain disease groups may take leading roles in decision making, domineering the voices of another legitimate cooperative stakeholder [44-48]. Finally, although data integration is an important strength of the HDC model, webpage records show that there is a risk for collecting too much data. Not only will this create waste, as some data may be unusable, but it can also make it difficult to maintain anonymity. As more personal data is combined for patients, the easier it becomes to re-identify a patient profile [49-51].

Implications and Future Work

The work presented here has implications to inform the development of HDCs in communities that face disparities in healthcare access, health outcomes, and exposure to social cultural, and environmental influences. The key question in health research is to understand how immigrant communities fare in comparison to the health of people born in Canada. To answer this, data on long-term health outcomes, preventable conditions, and chronic disease outcomes are essential. This review outlines the political, financial, and humanistic barriers that must be overcome to establish HDCs. First, there is a need for a transparent infrastructure of an HDC that works well with the political situation in Canada, which hosts a public healthcare system. The collection and hosting of health data must overcome barriers in costs, legality, and privacy and security that must not only be effective, but also be effectively communicated to HDC members. Finally, the investment of health data must establish a democratic process where cooperative members establish informed consent, and members have a voice within the sharing of such data. Regardless of these barriers, the HDC models would encourage the development of information sharing hubs or community-based labs for immigrant communities to understand the worth and consequences of health data and serve as a source of grassroots action to understand health data. Next steps to understand HDCs further, along with the nuances of establishing an HDC, could be to conduct an in-depth systematic review, environmental scans, and content analyses of prominent HDC models. Cooperatives are ultimately a community-level initiative; therefore future work should involve community members in the exploration for HDCs in order to provide effective ready-to-use evidence.

Strengths and limitations

This review is the first of its kind to map the literature on HDC and related topics. It has multiple strengths, the first being an extensive search strategy that includes database, grey literature, and internet search streams. The review was also strong in collating the literature into comprehensive themes that represented the data appropriately. However, this review had multiple limitations. The inclusion criteria may have been broad; however, this is something the authors felt was necessary to capture information on HDC and related topics appropriately. Further, the review was unable to assess the quality of the literature, due the variability in the type of records identified in this review. Finally, most records found hailed from Europe and the United States which present different sociopolitical and health-related environments. In this case, the results of this scoping review should be generalised to Canada with caution.

Conclusions

The results of this extensive scoping review found HDC to be a relatively unexplored topic, with a focus in records from the United States and Europe. Canada seems to be lacking in its use, discussion, or research of the HDC model. We found that the benefits and challenges of HDC operate around three main themes related to data control, data security, and data flow and infrastructure. The study of HDC is multi-disciplinary, with themes in law, ethics, medicine, and public health, and presents a way to revolutionise the collection, storage, and use of health data that may be more sustainable than other models. The results of this study are an informative first step to the study of the HDC model, or an establishment of a HDC in immigrant populations.

Ethics

Ethical approval is not required as this paper is research based on review of published/publicly reported literature.

Supplementary Appendices

Supplementary Appendix 1. PRISMA reporting checklist for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR)

Supplementary Appendix 2. Medline search strategy

References

- 1. Akbari AH, Haider A. Impact of immigration on economic growth in Canada and in its smaller provinces. Journal of International Migration and Integration. 1February2018;19(1):129-142. 10.1007/s12134-017-0530-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Statistics Canada. Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 Census. Retreived September 10, 2019 from Statistics Canada: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beiser M, Puente-Duran S, Hou F. Cultural distance and emotional problems among immigrant and refugee youth in Canada: Findings from the New Canadian Child and Youth Study (NCCYS). International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1November2015;49:33-45. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beiser M, Canada. Human Resources Development Canada. Applied Research Branch. Growing up Canadian: A study of new immigrant children. Human Resources Development Canada, Strategic Policy, Applied Research Branch; October1998.

- 5. Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1March2005;96(2):S30-44. 10.1007/BF03403701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali JS, McDermott S, Gravel RG. Recent research on immigrant health from Statistics Canada’s population surveys. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1May2004;95(3):I9-13. 10.1007/BF03403659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller-Thomson E, Noack AM, George U. Health decline among recent immigrants to Canada: findings from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1July2011;102(4):273-280. 10.1007/BF03404048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hafen E, Kossmann D, Brand A. Health data cooperatives–citizen empowerment. Methods of information in medicine. 2014;53(02):82-86. 10.3414/ME13-02-0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shommu NS, Ahmed S, Rumana N, Barron GR, McBrien KA, Turin TC. What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: A systematic scoping review. International journal for equity in health. December2016;15(1):6. 10.1186/s12939-016-0298-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Roessel I, Reumann M, Brand A. Potentials and challenges of the health data cooperative model. Public health genomics. 2017;20(6):321-331. https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/en/publications/potentials-and-challenges-of-the-health-data-cooperative-model [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine. 2October2018;169(7):467-473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology. 1February2005;8(1):19-32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Google.com, Mountain View, California, USA. Available from: https://www.google.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yahoo.com, Sunnyvale, California, USA. Available from https://ca.yahoo.com/?p=us [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bing.com, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA. Available from: https://www.bing.com/?toWww=1&redig=3147F62CCBD149F7B0F503CC6700D76A [Google Scholar]

- 16. Metacrawler.com, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA. Available from: https://www.metacrawler.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 17. Monstercrawler.com, London, England, United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.monstercrawler.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vayena E, Blasimme A. Biomedical big data: new models of control over access, use and governance. Journal of bioethical inquiry. 1December2017;14(4):501-513. 10.1007/s11673-017-9809-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Contreras JL, Rumbold J, Pierscionek B. Patient data ownership. Jama. 6March2018;319(9):935. 10.1001/jama.2017.21672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grumbach K, Mold JW. A health care cooperative extension service: transforming primary care and community health. JAMA. 24June2009;301(24):2589-2591. 10.1001/jama.2009.923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Montgomery J. Data sharing and the idea of ownership. The New Bioethics. 2January2017;23(1):81-86. 10.1080/20502877.2017.1314893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blasimme A, Vayena E, Hafen E. Democratizing Health Research Through Data Cooperatives. Philosophy & Technology. 1September2018;31(3):473-479. 10.1007/s13347-018-0320-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grant, P. Patient Ownership – creating the business environment to build the Learning Health System. Retrieved November 4, 2018, from http://www.ourhdc.com/

- 24. Hafen, E., Kossmann, D., & Brand, A.. Health Data Cooperatives – Citizen Empowerment. Retrieved Jan, 2014 from 10.3414/ME13-02-0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torres GW, Swietek K, Ubri PS, Singer RF, Lowell KH, Miller W. Building and Strengthening Infrastructure for Data Exchange: Lessons from the Beacon Communities. EGEMS. 2014;2(3). 10.13063/2327-9214.1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen C, Des Jardins TR, Arvela Heider KA, McWilliams L, Rein AL, Schachter AA, Singh R, Sorondo B, Topper J, Turske SA. Data governance and data sharing agreements for community-wide health information exchange: lessons from the beacon communities. EGEMS. 2014;2(1). 10.13063/2327-9214.1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Terry, K. Patient records: the struggle for ownership. Retrieved December, 2015 from: https://www.medicaleconomics.com/health-law-policy/patient-records-struggle-ownership [PubMed]

- 28. Institute of Molecular Systems Biology. Health Data Cooperatives-Citizen-Controlled Health Data Repositories as a Basis for Big Data Analytics in Health. Retrieved 2014 from: http://www.ehealth2014.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Pres_Hafen.pdf

- 29.Harper, C. Are digital data co-ops an alternative to the commercialisation of health? – This Is Not a Sociology Blog [Blog post]. Retrieved 2019, July from: https://thisisnotasociology.blog/2017/02/27/are-digital-data-co-ops-an-alternative-to-the-commercialisation-of-health/

- 30.Anzilotti, E. This co-op lets patients monetize their own health data [Blog post]. Available July, 2018 from: https://www.fastcompany.com/90207550/this-co-op-lets-patients-monetize-their-own-health-data

- 31. Van Roessel I, Reumann M, Brand A. Potentials and challenges of the health data cooperative model. Public health genomics. 2017;20(6):321-331. 10.1159/000489994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dorey CM, Baumann H, Biller-Andorno N. Patient data and patient rights: Swiss healthcare stakeholders’ ethical awareness regarding large patient data sets–a qualitative study. BMC medical ethics. December2018;19(1):20. 10.1186/s12910-018-0261-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Future Care Capital. Intelligent sharing: Unleashing the potential of health and care data in the UK to transform outcomes. Retrieved 2017 from: https://futurecarecapital.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Full-Report-Unleashing-the-potential-of-health-and-care-data.pdf

- 34. The National Association of Health Data Organizaitons Health Data Systems at a Crossroads: Lessons Learned From 25 Years of Hospital Discharge Data Reporting Programs. Retrieved 2019 from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311800896_Health_Data_Systems_at_a_Crossroads_Lessons_Learned_From_25_Years_of_Hospital_Discharge_Data_Reporting_Programs

- 35. Towards a European Ecosystem for Healthcare Data Workshop Report Towards a European Ecosystem for Healthcare: Workshop Report. Retrieved November 4, 2018, from https://ec.europa.eu/health/expert_panel/sites/expertpanel/files/012_disruptive_innovation_en.pdf

- 36. Vayena E, Gourna EL, Streuli J, Hafen E, Prainsack B. Experiences of early users of direct-to-consumer genomics in Switzerland: an exploratory study. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15(6):352-362. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1159/000343792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The future of your health data — Maneesh Juneja. Retrieved Nov, 2018 from http://maneeshjuneja.com/blog/2014/2/12/the-future-of-your-health-data

- 38. Mählmann L, Reumann M, Evangelatos N, Brand A. Big Data for Public Health Policy-Making: Policy Empowerment. Public health genomics. 2017;20(6):312-320. 10.1159/000486587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mikk KA, Sleeper HA, Topol EJ. The pathway to patient data ownership and better health. Jama. 17October2017;318(15):1433-1434. 10.1001/jama.2017.12145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holland Health Data Cooperative | LinkedIn. (n.d.). Retrieved Nov, 2018 from https://www.linkedin.com/company/holland-health-data-cooperative/about/

- 41. Steiger, D. MIDATA.COOP. Retrieved Nov, 2018 from https://www.midata.coop/en/home/

- 42. Vayena E, Ineichen C, Stoupka E, Hafen E. Playing a part in research? University students' attitudes to direct-to-consumer genomics. Public health genomics. 2014;17(3):158-168. 10.1159/000360257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Government of Canada: Co-operatives Secretariat. Health care co-operatives in Canada. Retrieved 2018 from: http://www5.agr.gc.ca/resources/prod/coop/doc/healthcare_coopsincan2004_e.pdf

- 44. Tracy CS, Dantas GC, Upshur RE. Feasibility of a patient decision aid regarding disclosure of personal health information: qualitative evaluation of the Health Care Information Directive. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 12;4(1):13. 10.1186/1472-6947-4-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nadeau, E.G. The First Mile: The potential for community-based health cooperatives in sub-Saharan Africa [Report]. Retrieved July 2018 from: http://www.thecooperativesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/The-First-Mile-Community-Based-Health-Cooperatives-.pdf

- 46. Connecticut Commission on Economic Competitiveness and The Commerce Committee. (2017). Status report of the Connecticut health data collaborative (CHDC). Retrieved July 2018 from: http://www.senatedems.ct.gov/docshr/pdf/Hartley-170203-CHDC.pdf

- 47. International Health Cooperative Organization. Cooperative health report. (2018). Retrieved July 2018 from: http://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-6160_en.html

- 48. Data Commons Cooperative. Retrieved Nov, 2018 from https://datacommons.coop/

- 49. Data Cooperatives. In P2P Foundation wiki. Retrieved Nov, 2018 from http://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Data_Cooperatives

- 50. Digital Health. 2005. Retrieved July 2018 from 10.4324/9781410613479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Health Record: Improving Health Through Multisector Collaboration, Information Sharing, and Technology [Report] Retrieved July 2018 from: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2016/16_0101.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]