Abstract

Background

The “time perspectives theory” describes how individuals emphasize some time frames over others (e.g., present vs. future) and thus create their unique approach to time perception. Building on this theory, we investigated three time orientations in Alzheimer’s disease (AD): (1) present-hedonistic orientation, which focuses on current sensations and pleasures without considering the future, (2) present-fatalistic orientation, characterized by a bias of hopelessness and helplessness toward the future, and (3) future orientation, which focuses on achieving personal goals and future consequences of present actions.

Methods

Participants with mild AD (n = 30) and controls (n = 33) were assessed with a questionnaire regarding time perspectives and a questionnaire of depression.

Results

Results demonstrated low future orientation and high present-fatalistic orientation in AD participants, whereas older adults demonstrated the reverse pattern. Depression positively correlated with fatalistic-present orientation, but negatively correlated with hedonistic-present and future orientations.

Discussion

Although our findings are preliminary and the sample size is small, depression in mild AD seems to be related with a fatalistic orientation toward the present, as well as a hopeless and helpless perspective on the future, an orientation that results in little desire to enjoy the present.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Depression, Future thinking, Time perspectives

Future thinking, i.e., the ability to project oneself forward in time to anticipate and plan for future events, has been found to be compromised in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1], and this compromise has been attributed to several cognitive factors, especially difficulties in the ability to extract and recombine information from past events into coherent and novel scenarios [2–4]. Research has also attributed the compromise of future thinking in AD patients to a decline in autonoetic consciousness, i.e., the ability to mentally project oneself in time [3]. Although these accounts provide insight into the cognitive mechanisms that underlie compromise of future thinking in AD, very little is known about the emotional and attitudinal correlates of future thinking in the disease.

The relationship between emotional regulation and future thinking can be highlighted with the “time perspectives theory” that describes how individuals assign the continual flow of personal experiences to temporal categories or time frames [5]. According to the time perspectives theory, individuals learn to categorize personal and social experiences into time frames (e.g., present vs. future) to lend order, coherence, and meaning to these events. More specifically, the time perspectives theory proposes five time orientations, (1) past positive, which refers to a positive sentimental and nostalgic vision of the past, (2) past negative, which refers to a negative attitude towards the personal past, (3) present-hedonistic, that refers to a focus on pleasures and current sensations, without considering the future, (4) present-fatalistic, characterized by a bias of hopelessness and helplessness toward the future, and (5) future, which refers to an orientation to achieve personal goals and to evaluate the future consequences of present actions. Considering these five orientations, our study investigated whether individuals with AD demonstrate an orientation toward the future or the hedonistic or fatalistic present. The positive and negative past orientations, as proposed by the time perspectives theory, were not investigated in our study, as the greatest clinical interest lies in future orientation in AD patients, which according to the theory is associated with emotional regulation and attitudes towards the present rather than with the past. Another reason was that, unlike the lack of research on present-hedonistic and present-fatalistic orientations in AD, an abundant literature has covered both past positive [6–8] and past negative orientations in the disease [9–11].

Besides investigating whether individuals with AD would demonstrate an orientation toward the hedonistic or fatalistic present when dealing with the future, another objective was to investigate relationships between these three time orientations and depression. This aim was inspired by research suggesting that time perspectives theory is relevant for the study of well-being, quality of life, and mental health [12, 13]. More specifically, hedonistic orientation toward the present has been found to be positively correlated with optimism [14] and happiness in the general population [15]; these findings are in line with the consideration of Maslow [16] who hypothesized that a focus on the present with an emphasis on the “here and now” is important for well-being. In contrary, the present-fatalistic orientation, as proposed by the time perspectives theory, has been found to reflect helpless and hopeless attitudes towards life and the future and has been found to be related with aggression, anxiety, and depression [17, 18]. In the same way, present-fatalistic orientation has been associated with lack of life satisfaction and poor mental health [19]. Present-fatalistic orientation has been also suggested as a significant indicator of suicidal ideation in adolescents [20]. As for the future orientation, research suggests that individuals who orient themselves towards the future possess high ability to plan and generally present high levels of subjective well-being and low levels of depression [21, 22]. Nevertheless, an overemphasis on future goals may result in high levels of anxiety, which negatively affect the capacity to enjoy present activities [15].

Research in normal aging has assessed the present-hedonistic, present-fatalistic, and future orientations. Desmyter and De Raedt [23] have investigated this issue in a population of 149 healthy older adults aged between 65 and 96 years. The authors found that older adults with present-hedonistic orientation reported more life satisfaction, and the same thing was observed for those with future orientation. In contrary, older adults with present-fatalistic orientation reported more depressive feelings and less satisfaction with life. These findings corroborate previous research showing that older adults tend to demonstrate more future and present-hedonistic orientation than present-fatalistic orientation [18]. There is also evidence to suggest that although older adults think often about their own future death, this future inspires less fear and anxiety in them than in younger adults [24]. Other studies also found that maintaining a future perspective is crucial for well-being in older people, if combined with other time orientations [25].

To summarize, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published information about future time perspectives in AD. We therefore compared present-hedonistic, present-fatalistic, and future orientations in individuals with AD. More specifically, we investigated whether these individuals demonstrate high present-fatalistic and low future orientations. We also investigated the relationship between these three time orientations and depression, expecting that high levels of depressive symptoms would be positively correlated with present-fatalistic orientation and negatively with low future orientation. We reasoned that, due to the disease and cognitive decline, people who have been diagnosed with AD may have lost hope for their future, resulting in depression and hopelessness and helplessness toward the future.

Method

Participants

This study included 30 participants with a clinical diagnosis of probable mild AD (22 women and 8 men; M age = 71.57 years, SD = 7.03; M years of formal education = 8.57, SD = 2.61) and 33 control older adults (23 women and 10 men; M age = 68.94 years, SD = 5.63; M years of formal education = 9.64, SD = 2.82). The AD participants were recruited from local retirement homes. They were diagnosed with probable AD dementia by an experienced neurologist or geriatrician based on the NIA-AA clinical criteria [26]. The older adults were often spouses or companions of AD participants, were independent and living at home. These participants were matched with the AD participants according to sex (X2 (1, N = 63) = .10, p > .10), age (t(61) = 1.64, p > .10), and educational level (t(61) = 1.56, p > .10).

All participants provided informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in The Declaration of Helsinki as well as those of the ethics committee of the Hospital of Tourcoing. Exclusion criteria were significant psychiatric or neurological illness, history of alcohol or drug use, and major visual or auditory acuity difficulties that could prevent assessment. Clinical and cognitive characteristics of all participants were assessed with a comprehensive battery described below (for further details on the battery, see [27, 28]). AD participants were tested in retirement homes and controls in their own homes.

Clinical and cognitive characteristics

Participants were assessed a battery tapping general cognitive functioning, episodic memory, working memory, shifting, and depressive symptoms. General cognitive functioning was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and the maximum score was 30 points [29]. Verbal episodic memory was evaluated with the task of Grober and Buschke [30] on which participants had to retain 16 words, each of which describes an item that belongs to a different semantic category. After immediate cued recall, the participants proceeded to a distraction phase, during which they had to count backwards from 374 in 20 s. The distraction phase was immediately followed by 2 min of free recall and the score/16 from this phase provided a measure of episodic recall. In the working memory assessment, participants had to repeat a string of single digits in the same order (i.e., forward spans) or in the reverse order (i.e., backward spans); scores referred to number of correctly repeated digits. In order to evaluate executive function, we assessed shifting with the Plus–Minus task. The score referred to the difference between the time for list 3 (shifting between addition and subtraction) and the average times for lists 1 (addition) and 2 (subtraction). We assessed depressive symptoms with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [31], consisting of seven items that were scored by the participants on a 4-point scale from 0 (not present) to 3 (considerable). Scores on clinical and cognitive tasks for study participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cognitive and clinical characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients and older adults

| Task | AD n = 30 | Older adults n = 33 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General cognitive functioning | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | 21.90 (1.49)*** | 28.36 (1.29) |

| Episodic memory | Grober and Buschke | 6.03 (2.25)*** | 11.03 (3.11) |

| Working memory | Forward span | 5.43 (1.38)* | 6.52 (1.82) |

| Backward span | 3.67 (1.15)*** | 5.27 (1.44) | |

| Shifting | Plus-Minus | 12.42 (7.23)*** | 6.16 (3.20) |

| Depressive symptoms | HADS | 10.33 (3.40)*** | 6.67 (2.29) |

Note: Standard deviations are given between brackets; the maximum score on the MMSE was 30 points; the maximum score on the episodic task was 16 points; performances on the forward and backward spans refer to number of correctly repeated digits; scores on the Plus–Minus task refer to reaction time; the maximum score on the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) was 21 points; differences between groups were significant at * p < .05, *** p < .001

Procedure

Participants completed a French validation [32] of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory [5]. The present-hedonistic orientation was assessed with seven items (“I do things impulsively,” “When listening to my favorite music, I often lose track of time,” “I try to live my life as fully as possible, one day at a time,” “Ideally, I would live each day as if it were my last,” “I make decisions on the spur of the moment,” “I often follow my heart more than my head,” and “I feel that it’s more important to enjoy what you’re doing than to get work done on time”). The present-fatalistic orientation was assessed with seven items (“Fate determines much of my life,” “Since whatever will be will be, it doesn’t really matter what I do,” “It takes joy out of the process and flow of my activities if I have to think about goals, outcomes, and products,” “My life path is controlled by forces I cannot influence,” “It doesn’t make sense to worry about the future, since there is nothing that I can do about it anyway,” “Life is too complicated; I would prefer the simpler life of the past,” and “Often luck pays off better than hard work”). The future orientation was assessed with seven items (“I believe that a person’s day should be planned ahead each morning,” “Meeting tomorrow’s deadlines and doing necessary work comes before tonight’s play,” “It upsets me to be late for appointments,” “I meet my obligations to friends and authorities on time,” “I take each day as it is rather than try to plan it out,” “Before making a decision, I weigh the costs against the benefits,” “I make lists of things to do,” and “There will always be time to catch up on my work”). Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very uncharacteristic of me; 5 = very characteristic of me). Although the French validation of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory includes more than seven items for the three time orientations, we excluded items that do not fit with everyday life of AD patients (e.g., “I believe that getting together with one’s friends to party is one of life’s important pleasures”) as well as those with low factor loadings in the French validation.

Results

We compared differences between mean scores of AD participants and older adults for each of the three time orientations. Non-parametrical tests were used due to the scale nature and abnormal distribution of variables. Significant comparisons were reported with effect size; d = 0.2 can be considered a small effect size, d = 0.5 represents a medium effect size, and d = 0.8 refers to a large effect size [33]. We also assessed, for each population, (Spearman) correlations between scores on the inventory and depressive symptoms. Bonferroni correction was not applied as it may increase type II errors and therefore may be overly conservative (for the same view, see [34, 35]). Another reason why Bonferroni correction might not be appropriate is related to the specificity of our hypothesis, according to Perneger [36], this correction may not be a necessary step in studies where specific predictions are made. For all tests, level of significance was set as p ≤ 0.05, p values between 0.051 and 0.10 were considered trends, if any.

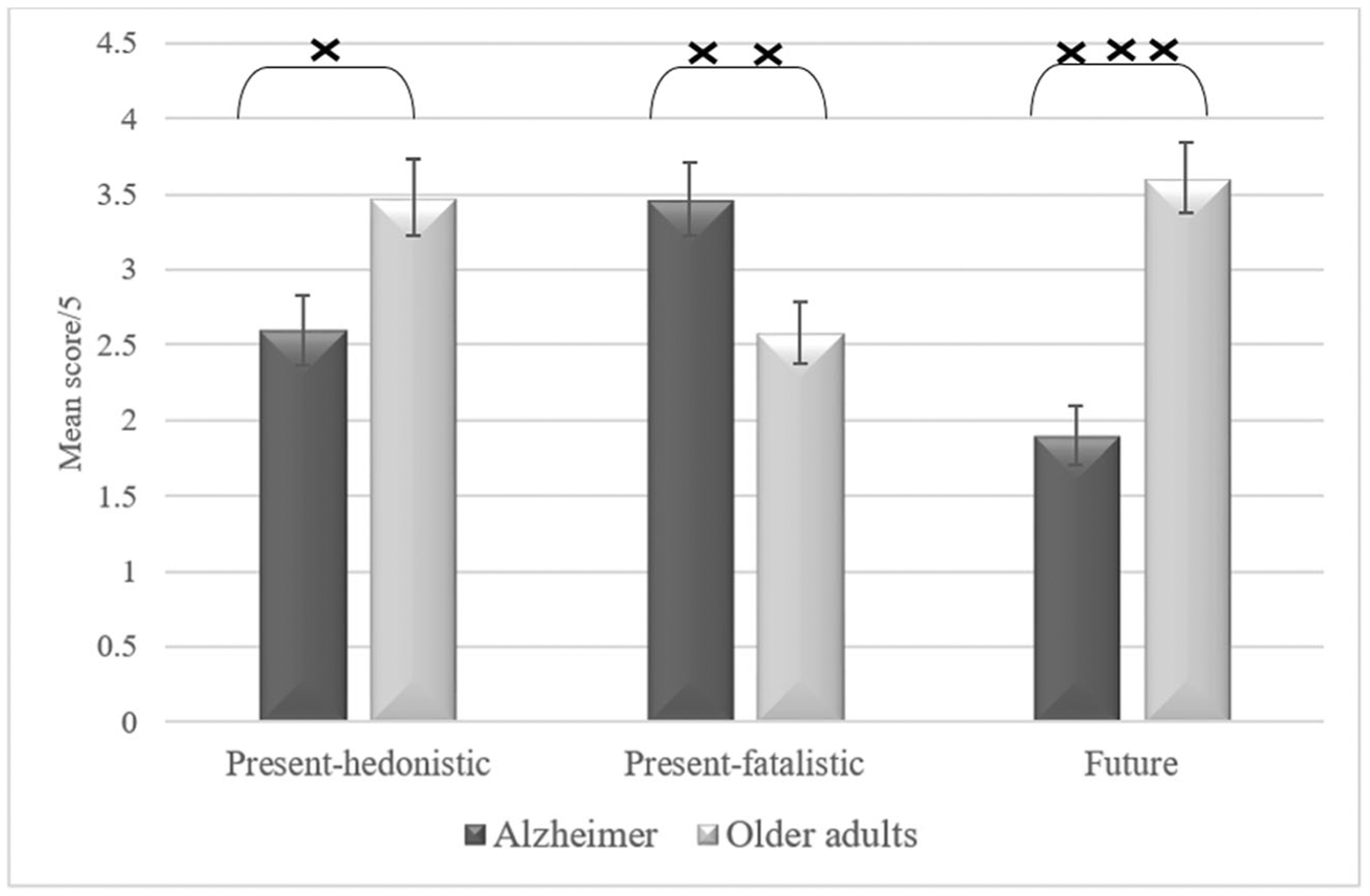

Low future orientation and high present-fatalistic orientation in AD

In AD participants (see Fig. 1), Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significantly lower scores on future orientation than on present-hedonistic orientation (Z = − 2.16, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .59) or on present-fatalistic orientation (Z = − 3.45, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.30), and lower scores on present-hedonistic orientation than on present-fatalistic orientation (Z = − 2.14, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .66). In older adults, analyses showed lower scores on present-fatalistic orientation than on future orientation (Z = − 2.62, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .81) or on present-hedonistic orientation (Z = − 2.46, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .67), whereas no significant differences were observed between future and present-hedonistic orientations (Z = .35, p > .01).

Fig. 1.

Mean scores on the three time perspectives, as assessed with the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory. xp < .05,xxp < .01, xxxp < .001. Error bars are 95% within-subject confidence intervals

The Mann–Whitney U test showed significantly lower scores in AD participants than in older adults on present-hedonistic orientation (Z = − 2.46, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .64), and future orientation (Z = − 4.55, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.47). Higher scores were observed in AD participants than in older adults on present-fatalistic orientation (Z = − 2.61, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .70).

Positive correlations between depressive symptoms and fatalistic-present orientation in AD

In both populations (see Table 2), depressive symptoms were positively correlated with fatalistic-present orientation, but negatively correlated with hedonistic-present and future orientations. For convenience, we assessed correlations between the three categories of time perspective and general cognitive ability, episodic memory, working memory, and shifting and found no significant correlations (p > .1).

Table 2.

Correlations between the three time orientations (i.e., present-hedonistic, present-fatalistic, and future) and depression

| 1. Hedonistic | 2. Fatalistic | 3. Future | 4. Depression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer | 1. | - | |||

| 2. | −.37 p < .05 | - | |||

| 3. | −.19 p > .01 | −.38 p < .05 | - | ||

| 4. | −.54 p < .01 | .44 p < .01 | −.46 p < .01 | - | |

| Older adults | 1. | - | |||

| 2. | −.11 p > .01 | - | |||

| 3. | −.10 p > .01 | −.10 p > .01 | - | ||

| 4. | −.47 p < .01 | .47 p < .01 | −.38 p < .05 | - |

Discussion

The paper investigated present-hedonistic, present-fatalistic, and future orientations in AD. Results demonstrated low future orientation and high present-fatalistic orientation in AD participants, whereas older adults demonstrated the reverse pattern. In both populations, depressive symptoms were positively correlated with fatalistic-present orientation, but were negatively correlated with hedonistic-present and future orientations.

Relatively to present-hedonistic and present-fatalistic orientations, our AD participants demonstrated low future orientation. These findings mirror the literature on decline of future thinking in the disease [2–4, 37]. More precisely, as the future orientation items of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory assess how individuals strive to achieve personal goals and evaluate future consequences of present actions, our findings suggest that individuals with AD tend to orient themselves disproportionately toward the present than toward the future. This consideration may be compared with the idea that people with amnesia occupy a permanent present [38] or lack the temporal consciousness that is required to recollect the past or construct the future [39–43]. Although this metaphor may be partially accurate in characterizing the mental life of a severely amnesic person or even individuals with advanced AD, it should be highlighted that individuals with mild AD are not literally “stuck in time.” These patients may demonstrate some ability to mentally project themselves in the future and, especially, project themselves in the past to recollect memories with high emotional valence [44, 45]. Together, our findings suggest that individuals with AD tend to consider their life in terms of short-term rather than long-term plans, disproportionately orienting themselves toward the present.

Besides demonstrating a general orientation toward the present than toward the future, our AD participants demonstrated more present-fatalistic than present-hedonistic orientation, and this fatalism was correlated with depressive symptoms. Generally speaking, hopelessness, as assessed with the present-fatalistic items of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, has been considered an indicator of depression [46, 47]. Empirical research, using a variety of methods, has demonstrated that depressed people tend to feel hopeless in their prediction of future and are more likely to anticipate negative events [48–50]. Considering the prevalence of depression in AD (for review, see [9, 10]), it is not surprising that our participants demonstrated more present-fatalistic than present-hedonistic orientations. Depression in AD seems to be related with a fatalistic orientation toward the present, as well as a hopeless and helpless perspective on the future, an orientation that results in little desire to enjoy the present (i.e., low present-hedonistic orientation). More specifically, due to the cognitive and functional decline, patients with AD may have lost hope for their future, resulting in depression and hopelessness toward the future. In other words, the awareness of looming death in AD, especially after the diagnosis is conveyed, may trigger depression and lack of a hedonistic orientation toward the present or future. Although a hedonistic focus on the here-and-now may function to reduce this negative effect, such orientation may be limited in AD patients due to the cognitive and functional decline as well as to the social withdrawal.

Contrary to AD participants, older adults demonstrated less present-fatalistic orientation than present-hedonistic or future orientations. These findings replicate research assessing the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory in normal aging [18, 23, 51]. Interestingly, depressive symptoms were negatively correlated with the present-hedonistic and future orientations, but positively correlated with the present-fatalistic orientations. These findings can be linked to the socioemotional selectivity theory [52], which holds that time perspectives influence motivation in aging. Research based on this theory has demonstrated that older people attach more importance and attention to present and past positive stimuli, resulting in general satisfaction with accomplishments during life [53, 54]. In our view, healthy older adults tend to see their future as a way of maintaining the positive affects they enjoy in the present. A positive view of the present in normal aging tends to go hand in hand with a positive attitude towards the future, and positive affect in general.

One potential limitation of our study is the small sample size, which increases the risk of type II statistical errors. We also did not correct for multiple comparisons, inflating the risk of type I error. Also, the causality between depression and future time perspective should be approached with caution as our findings demonstrate correlations rather than cause–effect relationships.

To summarize, human beings conceive the future and present in a dynamic interaction from which complex future thinking emerges in the ongoing present moment. This interaction requires conscious awareness of self-continuity, and the use of mental time travel into the past and future to, respectively, extract autobiographical information and construct future scenarios. Whereas research on future thinking in AD has been mainly concerned with the comparison between past and future thinking, our study expands this literature by demonstrating how future thinking influences the orientation toward the present. In our view, individuals with mild AD can successfully disentangle present from future time perspectives; the difficulty, however, lies in finding a balance between these two perspectives in a dynamic way according to the situation. This view suggests that compromise in time perspectives in AD may be related with a difficulty in switching flexibly between several time perspectives depending on task features and environmental demands, resulting in a bias towards a present-fatalistic orientation in the disease.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the LABEX (excellence laboratory, program investment for the future), DISTALZ (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary approach to Alzheimer disease), and the EU Interreg 2 Seas Programme 2014-2020 (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund). This research was also supported in part (DK) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All participants provided informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in The Declaration of Helsinki as well as those of the ethics committee of the Hospital of Tourcoing.

References

- 1.Irish M, Piolino P (2015) Impaired capacity for prospection in the dementias - theoretical and clinical implications. Br J Clin Psychol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Addis DR, Sacchetti DC, Ally BA, Budson AE, Schacter DL (2009) Episodic simulation of future events is impaired in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 47(12):2660–2671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Haj M, Antoine P, Kapogiannis D (2015) Similarity between remembering the past and imagining the future in Alzheimer’s disease: implication of episodic memory. Neuropsychologia. 66(0): 119–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Haj M, Antoine P, Kapogiannis D (2015) Flexibility decline contributes to similarity of past and future thinking in Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus. 25(11):1447–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimbardo P, Boyd JN (1999) Putting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J Pers Soc Psychol 77(6): 1271–1288 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotelli M, Manenti R, Zanetti O (2012) Reminiscence therapy in dementia: a review. Maturitas. 72(3):203–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moos I, Björn A (2006) Use of the life story in the institutional care of people with dementia: a review of intervention studies. Ageing Soc 26(03):431–454 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappeliez P (2013) Neglected issues and new orientations for research and practice in reminiscence and life review. Int J Reminiscence Life Rev 1(1):19–25 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holtzer R, Scarmeas N, Wegesin DJ, Albert M, Brandt J, Dubois B, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Stern Y (2005) Depressive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: natural course and temporal relation to function and cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(12):2083–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verkaik R, Nuyen J, Schellevis F, Francke A (2007) The relationship between severity of Alzheimer’s disease and prevalence of comorbid depressive symptoms and depression: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22(11):1063–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Haj M, Antoine P (2016) Death preparation and boredom reduction as functions of reminiscence in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 54(2):515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore M, Höfer S, McGee H, Ring L (2005) Can the concepts of depression and quality of life be integrated using a time perspective? Health Qual Life Outcomes 3(1):1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavot W, Diener E, Suh E (1998) The temporal datisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 70(2):340–354 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurmi J-E, Pulliainen H, Salmela-Aro K (1992) Age differences in adults’ control beliefs related to life goals and concerns. Psychol Aging 7(2):194–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake L, Duncan E, Sutherland F, Abernethy C, Henry C (2008) Time perspective and correlates of wellbeing. Time Soc 17(1):47–61 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslow AH (1972) The farther reaches of human nature. Maurice Bassett, New York [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boniwell I (2005) Beyond time management: how the latest research on time perspective and perceived time use can assist clients with time-related concerns. Int J Evid Based Coach Mentor 3(2): 61–74 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimbardo P, Boyd J (2008) The time paradox: the new psychology of time that will change your life. Free Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anagnostopoulos F, Griva F (2012) Exploring time perspective in Greek young adults: validation of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory and relationships with mental health indicators. Soc Indic Res 106(1):41–59 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laghi F, Baiocco R, D’Alessio M, Gurrieri G (2009) Suicidal ideation and time perspective in high school students. Eur Psychiatry 24(1):41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allemand M, Hill PL, Ghaemmaghami P, Martin M (2012) Forgivingness and subjective well-being in adulthood: the moderating role of future time perspective. J Res Pers 46(1):32–39 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coudin G, Lima ML (2011) Being well as time goes by: future time perspective and well-being. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 11(2):219–232 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desmyter F, De Raedt R (2012) The relationship between time perspective and subjective well-being of older adults. Psychol Belg 52(1):19–38 [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Raedt R, Van Der Speeten N (2008) Discrepancies between direct and indirect measures of death anxiety disappear in old age. Depress Anxiety 25(8):E11–EE7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shifflett PA (1987) Future time perspective, past experiences, and negotiation of food use patterns among the aged. The Gerontologist 27(5):611–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH et al. (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 7(3):263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Haj M, Jardri R, Laroi F, Antoine P (2016) Hallucinations, loneliness, and social isolation in Alzheimer’ disease. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 21(1):1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Haj M, Kapogiannis D, Antoine P (2016) Phenomenological reliving and visual imagery during autobiographical recall in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 52(2):421–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grober E, Buschke H (1987) Genuine memory deficits in dementia. Dev Neuropsychol 3(1):13–36 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apostolidis T, Fieulaine N (2004) Validation française de l’échelle de temporalité. Rev Eur Psychol Appl 54(3):207–217 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, Erlbaum Associates [Google Scholar]

- 34.García LV (2004) Escaping the Bonferroni iron claw in ecological studies. Oikos. 105(3):657–663 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moran MD (2003) Arguments for rejecting the sequential Bonferroni in ecological studies. Oikos. 100(2):403–405 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perneger TV (1998) What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 316(7139):1236–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irish M, Addis DR, Hodges JR, Piguet O (2012) Considering the role of semantic memory in episodic future thinking: evidence from semantic dementia. Brain. 135(Pt 7):2178–2191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craver CF, Kwan D, Steindam C, Rosenbaum RS (2014) Individuals with episodic amnesia are not stuck in time. Neuropsychologia. 57:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tulving E (2002) Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annu Rev Psychol 53:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.La Corte V, George N, Pradat-Diehl P, Barba GD (2011) Distorted temporal consciousness and preserved knowing consciousness in confabulation: a case study. Behav Neurol 24(4):307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein SB, Loftus J, Kihlstrom JF (2002) Memory and temporal experience: the effects of episodic memory loss on an amnesic patient’s ability to remember the past and imagine the future. Soc Cogn 20(5):353–379 [Google Scholar]

- 42.La Corte V, Serra M, Attali E, Boisse MF, Dalla BG (2010) Confabulation in Alzheimer’s disease and amnesia: a qualitative account and a new taxonomy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16(6):967–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El Haj M, Kapogiannis D (2016) Time distortions in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and theoretical integration. Npj Aging Mech Dis 2:16016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinelli P, Anssens A, Sperduti M, Piolino P (2013) The influence of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease in autobiographical memory highly related to the self. Neuropsychology. 27(1):69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El Haj M, Antoine P, Nandrino JL, Gely-Nargeot MC, Raffard S (2015) Self-defining memories during exposure to music in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 27(10):1719–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB (1989) Hopelessness depression: a theory-based subtype of depression. Psychol Rev 96(2): 358–372 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, Stewart BL, Steer RA (2006) Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: a replication with psychiatric outpatients. FOCUS. 4(2):291–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunning D, Story AL (1991) Depression, realism, and the overconfidence effect: are the sadder wiser when predicting future actions and events? J Pers Soc Psychol 61(4):521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connor RC, Connery H, Cheyne WM (2000) Hopelessness: the role of depression, future directed thinking and cognitive vulnerability. Psychol Health Med 5(2):155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lavender A, Watkins E (2004) Rumination and future thinking in depression. Br J Clin Psychol 43(Pt 2):129–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petkoska J, Earl JK (2009) Understanding the influence of demographic and psychological variables on retirement planning. Psychol Aging 24(1):245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST (1999) Taking time seriously. a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol 54(3):165–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed AE, Carstensen LL (2012) The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Front Psychol 3:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Brooks KP, Nesselroade JR (2011) Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychol Aging 26(1):21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]