Néel-type skyrmions in van der Waals ferromagnetic Fe3GeTe2 on (Co/Pd)n superlattice were created without external magnetic field.

Abstract

Magnetic skyrmions are topological spin textures, which usually exist in noncentrosymmetric materials where the crystal inversion symmetry breaking generates the so-called Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. This requirement unfortunately excludes many important magnetic material classes, including the recently found two-dimensional van der Waals (vdW) magnetic materials, which offer unprecedented opportunities for spintronic technology. Using photoemission electron microscopy and Lorentz transmission electron microscopy, we investigated and stabilized Néel-type magnetic skyrmion in vdW ferromagnetic Fe3GeTe2 on top of (Co/Pd)n in which the Fe3GeTe2 has a centrosymmetric crystal structure. We demonstrate that the magnetic coupling between the Fe3GeTe2 and the (Co/Pd)n could create skyrmions in Fe3GeTe2 without the need of an external magnetic field. Our results open exciting opportunities in spintronic research and the engineering of topologically protected nanoscale features by expanding the group of skyrmion host materials to include these previously unknown vdW magnets.

INTRODUCTION

It was found recently that van der Waals (vdW) magnetic materials (1, 2) exhibit many fascinating properties such as the giant tunneling magnetoresistance (3), unconventional responses from quantum metamaterials (4), the pressure (5, 6) and electrical (7, 8) control of magnetism, etc. However, the crystal structures of most vdW magnetic materials (9) have inversion symmetry, thus nominally disqualifying the generation of the so-called Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions (DMIs) (10, 11). The recent success in expanding skyrmion materials from noncentrosymmetric magnets (12–14) to centrosymmetric magnets (15, 16) by dipole-dipole interaction makes it promising to search for skyrmions in vdW magnetic materials by magnetic interaction.

Among the vdW magnetic materials, Fe3GeTe2 (FGT) is an itinerant vdW ferromagnet with a relatively high Curie temperature (TC ~ 230 K) and many interesting magnetic properties (17–20). In particular, the tunable TC and the perpendicular magnetic stripe domains (21–24) in FGT make it an ideal candidate for the formation of magnetic skyrmions. Despite the various theoretical proposals (25–27), skyrmions have only been observed in vdW magnets within an out-of-plane magnetic field so far (28–32). However, the results are very controversial and confusing on the skyrmion structure [Bloch type (28, 29) or Néel type (30–32)], raising the question on the physical origin of the skyrmion formation within the magnetic field (inherent material properties or due to the presence of the magnetic field). To explore the underlying mechanism, it is very important to realize skyrmions in magnetic vdW materials as the ground state in the absence of magnetic field. Here, in this work, we demonstrate a realization of Néel-type magnetic skyrmions in FGT in the heterostructures of FGT/[Co/Pd]10 multilayers at zero magnetic field, which is likely to be stabilized by the magnetic interlayer coupling.

RESULTS

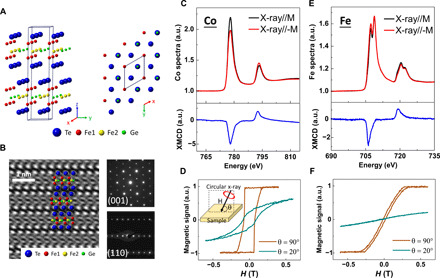

We fabricated the sample of Pd(1)/FGT/Pd(wedge)/[Co(0.4)/Pd(0.9)]10/Pd(3) on a Si(111) substrate (see the “MATERIALS AND METHODS” section), where the numbers in parentheses are the film thicknesses in units of nanometer. The Pd wedge (0 to 16 nm) permits a monotonic decrease in the ferromagnetic coupling between the FGT and [Co/Pd]10 with increasing Pd spacer layer thickness (33). Figure 1A shows the schematic drawing of the FGT atomic structure: Covalently bonded Fe3Ge layers are separated by two adjacent Te layers that are vdW gapped. The Fe atoms occupy two inequivalent Wyckoff sites denoted as Fe1 and Fe2: The Fe1 atoms form a hexagonal net, and the Fe2 atoms are bonded covalently with the Ge atoms to form a hexagonal structure of P63/mmc space group. High-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image together with sharp electron diffraction patterns indicate the high quality of our single crystalline FGT samples (Fig. 1B). There is no evidence of inversion symmetry breaking from the TEM result of the bulk FGT crystal. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) manifests as the difference of x-ray absorption spectra for magnetization parallel and antiparallel to the x-ray incidence direction (Fig. 1, C and E). Then, element-resolved Co and Fe XMCD measurements were performed by tuning the x-ray photon energy across the Co L3 edge absorption energy of 778.0 eV (Fig. 1C) and the Fe L3 edge absorption energy of 706.3 eV (Fig. 1E), respectively. Since XMCD measures the projection of the magnetization along the x-ray incidence direction, we obtained the out-of-plane and in-plane hysteresis loops at normal (θ = 90°) and grazing (θ = 20°) incidence of the circularly polarized x-rays (Fig. 1D), respectively. The Co/Pd multilayers exhibit an out-of-plane easy-axis hysteresis loop and an in-plane hard-axis hysteresis loop (Fig. 1D), consistent with the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy of Co/Pd multilayers in this thickness range (34, 35). The FGT hysteresis loops also exhibit a much smaller saturation field of the out-of-plane hysteresis loop than that of the in-plane hysteresis loop (Fig. 1F), showing an out-of-plane easy magnetization axis. The zero remanence is consistent with the formation of the stripe domain (labyrinthine domain) phase in FGT (22, 24). All the XMCD measurements were performed at T = 110 K, well below the bulk FGT Curie temperature.

Fig. 1. Crystal structure and element-resolved XMCD measurement.

(A) Atomic structure of FGT. (B) High-resolution cross-section scanning TEM image (left) and the corresponding electron diffraction patterns of (001)-oriented (top right) and (110)-oriented (bottom right) FGT. There is no evidence of inversion symmetry breaking in the bulk FGT crystal. Element-resolved XMCD measurements from (C) the Co absorption edge and (E) the Fe absorption edge, respectively. a.u., arbitrary units. Both (D) the Co and (F) the Fe hysteresis loops show an out-of-plane easy magnetization axis from Co/Pd multilayers and FGT vdW material. The inset in (D) is the schematic drawing for the hysteresis loop measurement, where θ is the angle between the x-ray incidence direction and the sample surface.

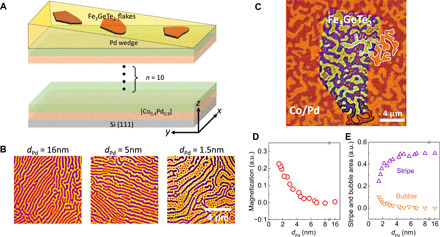

The sample was magnetized along the out-of-plane direction (+z direction) at room temperature to force the Co/Pd multilayers into a single domain (see fig. S1) and then imaged at zero field using photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) at T = 110 K along the Pd wedge to enable a systematic study of the FGT domain pattern as a function of the Pd thickness. As a reference, FGT domains on top of a thick Pd layer (dPd = 16 nm) are shown in Fig. 2B to represent the zero-coupling case. As expected, we observed the same stripe domains as in the free FGT flake (22) with equal amounts of bright and dark stripes whose magnetizations are in the +z and −z directions, respectively. As the Pd spacer thickness decreases to 5 nm to turn on the magnetic coupling between the FGT and [Co/Pd]10, some of the dark stripes (whose magnetization is in −z direction and antiparallel to the [Co/Pd]10 magnetization direction) break into bubbles (later shown in Fig. 3 to be Néel-type skyrmions). With further increase in the coupling by reducing the Pd thickness to 1.5 nm, more dark stripes break into bubbles (skyrmions). Note that the stripe width (~160 nm) and the bubble diameter (~140 nm) are more or less unchanged with increasing interlayer coupling strength. Since the magnetic domains of FGT has been confirmed, not vary from flake to flake in the thick region above 50 nm (22), the slight change of FGT minority domain width in different flakes may be due to different thicknesses of Pd spacer layer. We also quantitatively analyzed the PEEM images in Fig. 2B to obtain the bubble area and the normalized magnetization (the areal difference between the bright and dark domains). The results clearly show that as the interlayer coupling increases by reducing the Pd spacer layer thickness from 16 to 1.5 nm, the magnetization increases (Fig. 2E) at the expense of reducing the area (Fig. 2E) of minority domains (dark stripes). The bubble area simultaneously increases, further confirming our observation that the bubbles (skyrmions) are formed by breaking the dark stripes (antiparallel to the [Co/Pd]10 magnetization) into bubbles. Note that our result does not depend on the mechanism of the interlayer coupling mechanism but only on the existence of this coupling. In addition, since the [Co/Pd]10 is at the single domain state in Fig. 2B, stray field effect should be negligible as compared to the interlayer coupling (33).

Fig. 2. Creating magnetic skyrmions in FGT by the magnetic interlayer coupling between FGT and [Co/Pd]10 multilayers.

(A) Schematic drawing of the sample structure, where the wedged Pd spacer layer tunes the coupling strength between FGT and perpendicularly magnetized [Co/Pd]10 multilayers. (B) PEEM images of the FGT magnetic domains at three different thicknesses of the Pd spacer layer. The bright and dark contrasts correspond to an out-of-plane magnetization in the +z and –z directions, respectively. The [Co/Pd]10 underlayer was magnetized in the +z direction. Dark stripes are gradually broken into bubbles (skyrmions) as the coupling strength increases by decreasing the Pd thickness. The thicknesses of FGT flakes are 130, 150, and 130 nm, respectively. (C) Magnetic domain images of the FGT obtained at Fe L3 edge (the center flake) and the [Co/Pd]10 obtained at Co L3 edge (surrounding area) at dPd = 0.9 nm after demagnetizing the [Co/Pd]10 into multidomains. The magnetization direction inside the bubbles is always antiparallel to the underlayer [Co/Pd]10 magnetization. (D) FGT normalized magnetization calculated from the areal difference between the bright and the dark domains of the PEEM images and (E) from areal fractions of stripes and bubbles (antiparallel to [Co/Pd]10 magnetization) as a function of Pd spacer layer thickness.

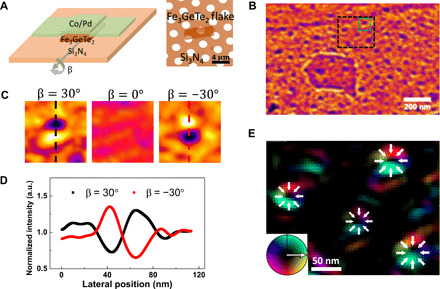

Fig. 3. Néel-type skyrmions observed by LTEM in the system of FGT/[Co/Pd]10 multilayers.

(A) Schematic drawing of sample structure and TEM image of FGT flake on a porous Si3N4 membrane. The thickness of FGT flake here is 70 nm. (B) LTEM images of FGT/[Co/Pd]10 at a sample tilting angle of 30°. (C) LTEM images taken from selected area in (B) (green dashed box) at sample tilting angles of 30°, 0°, and − 30°. The zero contrast at 0° tilting angle and the reversed contrasts at opposite tilting angles indicate the Néel-type structure of the skyrmion. All LTEM measurements were performed at liquid nitrogen temperature. (D) Line profiles of the contrast from the same skyrmion at opposite tilting angles, showing the contrast reversal of the Néel-type skyrmion at opposite tilting angles. (E) The magnetization distribution obtained by exit wave phase reconstruction of the selected LTEM data [black dashed box in (B)]. The white arrows and the color wheel indicate the in-plane direction of the magnetization.

We then demagnetized the sample to change the [Co/Pd]10 from a single-domain magnetized state (+z direction) into multidomains. Element-resolved PEEM measurements provide both the [Co/Pd]10 and FGT domain images by tuning the x-ray photon energy to the Co L3 edge or Fe L3 edge absorption energies, respectively. The [Co/Pd]10 multilayers exhibit a dendrite-like multidomain pattern with alternating up (+z direction, bright area) and down (−z direction, dark area) magnetizations (domains surrounding the center FGT flake in Fig. 2C). Consequently, we observed both dark and bright bubbles grouped into dendrite-like domains in the FGT flake. It should be mentioned that PEEM only measures the top layer magnetization due to the finite escape depth of photoemission electrons (a few nanometers). However, since the bright (or dark) [Co/Pd]10 domain connects well with bright (or dark) FGT dendrite-like domains at the boundary of the FGT flake (see white and dark dendrite-like profiles in Fig. 2C), it can be clearly seen that the bubble magnetization in FGT is always antiparallel to the [Co/Pd]10 underlayer local magnetization direction, the same as in Fig. 2B when the [Co/Pd]10 underlayer is in a single domain state. Therefore, we conclude that the transition of the stripe phase to skyrmion (bubble) phase in FGT must be a result of its magnetic coupling to the perpendicularly magnetized [Co/Pd]10.

To probe the topological structure of the observed bubbles (36), we used Lorentz TEM (LTEM) to resolve the magnetic structure of the domain wall. By defocusing the imaging lens, the Lorentz deflection of the electron beam due to a local in-plane magnetic field will diverge or converge to generate intensity contrast from these regions of the sample. Note that the PEEM experiment could not reveal the strong coupling limit for dPd < 1 nm (in this limit, all minority stripes in Fig. 2 should be converted into bubbles) due to the oxidization of Co layer. Thus, we prepared a sample of [Co/Pd]10/FGT on a Si3N4 membrane (see the “MATERIALS AND METHODS” section) by growing [Co/Pd]10 on top of FGT without the Pd spacer layer between FGT and [Co/Pd]10, which corresponds to the dPd = 0 nm case for sample structure used for PEEM measurements (Fig. 2). [Co/Pd]10 was magnetized along the out-of-plane direction at room temperature into a single domain state, so any magnetic contrast in LTEM images comes from the in-plane component of magnetization in the FGT layer. Figure 3A shows the schematic drawing of the sample side view and TEM image of the top view. A well-established method for the detection of the spin configuration of a skyrmion is to compare the defocused LTEM images at various tilting angles of the sample relative to the electron beam (37, 38). Since the contrast in LTEM arises from the projection of the magnetization curl along the beam propagation direction, a Néel-type skyrmion should not show any contrast at normal incidence but show opposite contrasts in each halves of the skyrmion after tilting the sample (37). We found that the system has Néel-type skyrmions at zero field (Fig. 3B) whose LTEM image exhibits zero contrast at normal incidence (Fig. 3C, middle), dark/bright contrasts within two halves of the skyrmion after tilting the sample by +30° (Fig. 3C, left), and a contrast reversal after tilting the sample in the opposite direction (i.e., −30°; Fig. 3C, right). The line profile in Fig. 3C more clearly shows the contrast reversal (Fig. 3D) for opposite tilting angles, further confirming the Néel-type structure of the skyrmion. To construct the magnetization distribution map, we analyzed a series of LTEM images (see fig. S2) from underfocus to overfocus using the exit wave phase reconstruction method (39). Figure 3E shows the magnetization distribution of the Néel-type skyrmions, where hedgehog-like spin configurations were observed. It should be mentioned that the LTEM images in Fig. 3 were obtained in zero magnetic field so that any field effect on the wall type of skyrmions was eliminated. In another word, the Néel-type structure of the skyrmion should be an inherent property of FGT.

DISCUSSION

As shown in our previous work (22), the stripe domains in FGT are a result of the competition among the exchange interaction, magnetic anisotropy, and dipolar interaction. In the limit of the strong dipolar interaction such as in bulk FGT, the stripe width reaches a minimum width (on the order of 102 nm). This is the stripe phase in the dPd = 16-nm sample (Fig. 2B), where the 16-nm Pd is thick enough to decouple the coupling between FGT and [Co/Pd]10. It is very important to point out that the stripe phase retains the up/down symmetry (inversion symmetry along the z axis), e.g., the magnetic stripe pattern (both the up/down area ratio and the shape) is invariant after changing Sz to –Sz, where Sz is the spin component of FGT along the surface normal direction. In contrast, the skyrmion phase breaks the up/down symmetry in the sense that both the up/down domain areas and the up/down domain shapes (e.g., separated bubbles versus connected area) will change after changing Sz to –Sz. Therefore, the existence of stripe domains in the dPd = 16-nm sample shows that inversion symmetry breaking along the z axis at the FGT/Pd interface or any possible sample surface oxidization is certainly not strong enough to stabilize magnetic skyrmions in FGT. Therefore, it must be the magnetic coupling between the stripe phase and the perpendicular magnetization of the [Co/Pd]10 that drives and stabilizes the skyrmion phase in FGT in the dPd = 5 and 1.5 nm samples (Fig. 2B).

We can qualitatively understand the transition from the stripe phase to the skyrmion phase from the following scenario. The coupling between FGT and [Co/Pd]10 should result in a net perpendicular magnetization in FGT by reducing the minority domain area (dark stripes in Fig. 2B). Since the stripes are already reaching the minimum width, the minority stripes have to be broken into segments (equivalent bubbles) to reduce their relative area. Consequently, as the magnetization increases with the coupling strength, more and more bubbles appear by breaking the minority stripes as shown in Fig. 2, B, D, and E. Our result may also explain the existence of skyrmions within an out-of-plane magnetic field where the field also reduces the minority domains. However, since LTEM measurement can only have magnetic field applied along the electron beam direction, there is an inevitable in-plane component of magnetic field when imaging the Néel-type skyrmions at a tilting angle of the sample. It is not clear at present on how this in-plane component of magnetic field affects the skyrmion formation. Using LTEM, we analyzed the stripe domains in a FGT flake without the [Co/Pd]10 and identified the Néel-type walls of the stripes (see fig. S3). Since there is no broken inversion symmetry in FGT crystal, it is unclear if the observed Néel-type wall is from mechanisms other than DMI [e.g., dipole-dipole interaction (15, 16)]. We would like to leave this topic as an open question for future studies. In summary, we demonstrate the realization of magnetic skyrmions in magnetic vdW FGT by magnetic coupling between FGT and out-of-plane magnetized Co/Pd multilayers. Our findings provide an effective method to induce magnetic skyrmions in vdW magnets at zero magnetic field in magnetic heterostructures, opening a new avenue to vdW magnet-based topological spintronics such as the zero-field skyrmion motion in vdW ferromagnets. The expansion of skyrmion materials to the vdW materials by this work should generate new opportunities for both magnetic research and vdW material research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample fabrication

The sample of Pd wedge (0 to 16 nm)/[Co0.4/Pd0.9]10/Pd (3) on a Si(111) substrate was grown by molecular beam epitaxy in an ultrahigh vacuum chamber with a base pressure of 5 × 10−10 torr. All films were grown at room temperature from the thermal crucibles. The Si(111) substrate was first annealed to ~200°C. Then, a 3-nm thick bottom Pd layer was grown as a seed layer. The thicknesses of Co and Pd in the stack structure were chosen to exhibit strong out-of-plane magnetic anisotropy. Then, a Pd wedge (0 to 16 nm) was grown by moving the substrate behind a knife-edge shutter during the growth. FGT flakes were exfoliated from a high-quality bulk FGT single crystal, which was fabricated by chemical vapor transport method. To facilitate the FGT exfoliation, the sample was heated to 50°C, exfoliated, and transferred immediately (within 15 min) into the ultrahigh vacuum chamber. Last, a 1.0-nm-thick Pd protection layer was grown on top of the sample from a thermal crucible.

Samples on membranes were prepared for LTEM imaging. A porous TEM grid with a 200-nm Si3N4 film and 2.0-μm-diameter pores window was used as substrate. FGT flakes were exfoliated onto a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp attached to a glass slide. The glass slide was subsequently attached to a micromanipulator with a microscope to align the exfoliated flakes with the substrate. The flakes were transferred by bringing the PDMS stamp into contact with the substrate and slowly peeling it off, all at room temperature. After transferring the flakes, the sample was transferred into the ultrahigh vacuum chamber. In the chamber, the sample was first annealed at ~100°C, after which 10 stacks of Co/Pd multilayer were deposited.

XMCD, PEEM, and LTEM measurement

XMCD measurements were performed at Beamline 4.0.2 and 6.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source by switching the magnetization parallel and antiparallel to the propagation direction of a circularly polarized x-rays at normal incidence. Magnetic domain images from PEEM were taken at Beamline 11.0.1 of the Advanced Light Source using left- and right-circular polarized x-rays at a photon energy of 706.3 eV (778.0 eV), which corresponds to the energy of maximum XMCD at Fe (Co) L3 edge.

The LTEM images were acquired using the FEI Themis TEM in molecular foundry. A series of images were obtained in Lorentz mode with various defocus values from −400 to 400 μm at a step of 100 μm. A Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm was used for the exit wave phase reconstruction, in combination with an iterative algorithm to remove the in-plane imaging distortions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The project is primarily supported by U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231 (van der Waals Heterostructures Program, KCWF16). This research used resources of the Advanced Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the DOE under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. J.W.C. acknowledges support by the KIST Institutional Program and the National Research Foundation of Korea (no. 2019K1A3A7A09033388). G.C. acknowledges support by the NSF (DMR-1610060) and the UC Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives (MRP-17-454963). Y.Z.W. acknowledges support by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 11734006 and 11974079). C.H. acknowledges support by Future Materials Discovery Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (no. 2015M3D1A1070467) and Science Research Center Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (no. 2015R1A5A1009962). Author contributions: Q.L., M.Y., and Z.Q.Q. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. R.V.C. performed the PEEM measurements and contributed to the discussion. R.D., J.T., and C.O. carried out the LTEM measurements and analyzed the LTEM data. J.D.C. and F.W. helped to prepare the samples. C.K., P.S., and A.T.N. performed the XMCD measurements and contributed to the discussion. J.W.C., G.C., Y.Z.W., and C.H. were involved in the analysis and discussion of the data. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/36/eabb5157/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gong C., Li L., Li Z., Ji H., Stern A., Xia Y., Cao T., Bao W., Wang C., Wang Y., Qiu Z. Q., Cava R. J., Louie S. G., Xia J., Zhang X., Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature 546, 265–269 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang B., Clark G., Navarro-Moratalla E., Klein D. R., Cheng R., Seyler K. L., Zhong D., Schmidgall E., McGuire M. A., Cobden D. H., Yao W., Xiao D., Jarillo-Herrero P., Xu X., Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270–273 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song T., Cai X., Tu M. W.-Y., Zhang X., Huang B., Wilson N. P., Seyler K. L., Zhu L., Taniguchi T., Watanabe K., McGuire M. A., Cobden D. H., Xiao D., Yao W., Xu X., Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der Waals heterostructures. Science 360, 1214–1218 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song J. C. W., Gabor N. M., Electron quantum metamaterials in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 986–993 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song T., Fei Z., Yankowitz M., Lin Z., Jiang Q., Hwangbo K., Zhang Q., Sun B., Taniguchi T., Watanabe K., McGuire M. A., Graf D., Cao T., Chu J.-H., Cobden D. H., Dean C. R., Xiao D., Xu X., Switching 2D magnetic states via pressure tuning of layer stacking. Nat. Mater. 18, 1298–1302 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li T., Jiang S., Sivadas N., Wang Z., Xu Y., Weber D., Goldberger J. E., Watanabe K., Taniguchi T., Fennie C. J., Mak K. F., Shan J., Pressure-controlled interlayer magnetism in atomically thin CrI3. Nat. Mater. 18, 1303–1308 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang B., Clark G., Klein D. R., MacNeill D., Navarro-Moratalla E., Seyler K. L., Wilson N., McGuire M. A., Cobden D. H., Xiao D., Yao W., Jarillo-Herrero P., Xu X., Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 544–548 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z., Zhang T., Ding M., Dong B., Li Y., Chen M., Li X., Huang J., Wang H., Zhao X., Li Y., Li D., Jia C., Sun L., Guo H., Ye Y., Sun D., Chen Y., Yang T., Zhang J., Ono S., Han Z., Zhang Z., Electric-field control of magnetism in a few-layered van der Waals ferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 554–559 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibertini M., Koperski M., Morpurgo A. F., Novoselov K. S., Magnetic 2D materials and heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 408–419 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dzyaloshinskii I. E., Thermodynamical theory of “weak” ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic substances. Sov. Phys. JETP 5, 1259–1272 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriya T., Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mühlbauer S., Binz B., Jonietz F., Pfleiderer C., Rosch A., Neubauer A., Georgii R., Böni P., Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu X. Z., Onose Y., Kanazawa N., Park J. H., Han J. H., Matsui Y., Nagaosa N., Tokura Y., Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 465, 901–904 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kézsmárki I., Bordács S., Milde P., Neuber E., Eng L. M., White J. S., Rønnow H. M., Dewhurst C. D., Mochizuki M., Yanai K., Nakamura H., Ehlers D., Tsurkan V., Loidl A., Néel-type skyrmion lattice with confined orientation in the polar magnetic semiconductor GaV4S8. Nat. Mater. 14, 1116–1122 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X., Mostovoy M., Tokunaga Y., Zhang W., Kimoto K., Matsui Y., Kaneko Y., Nagaosa N., Tokura Y., Magnetic stripes and skyrmions with helicity reversals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8856–8860 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X. Z., Tokunaga Y., Kaneko Y., Zhang W. Z., Kimoto K., Matsui Y., Taguchi Y., Tokura Y., Biskyrmion states and their current-driven motion in a layered manganite. Nat. Commun. 5, 3198 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y., Lu H., Zhu X., Tan S., Feng W., Liu Q., Zhang W., Chen Q., Liu Y., Luo X., Xie D., Luo L., Zhang Z., Lai X., Emergence of Kondo lattice behavior in a van der Waals itinerant ferromagnet, Fe3GeTe2. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao6791 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan C., Lee J., Jung S.-G., Park T., Albarakati S., Partridge J., Field M. R., McCulloch D. G., Wang L., Lee C., Hard magnetic properties in nanoflake van der Waals Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 1554 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alghamdi M., Lohmann M., Li J., Jothi P. R., Shao Q., Aldosary M., Su T., Fokwa B. P. T., Shi J., Highly efficient spin–orbit torque and switching of layered ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 19, 4400–4405 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X., Tang J., Xia X., He C., Zhang J., Liu Y., Wan C., Fang C., Guo C., Yang W., Guang Y., Zhang X., Xu H., Wei J., Liao M., Lu X., Feng J., Li X., Peng Y., Wei H., Yang R., Shi D., Zhang X., Han Z., Zhang Z., Zhang G., Yu G., Han X., Current-driven magnetization switching in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw8904 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng Y., Yu Y., Song Y., Zhang J., Wang N. Z., Sun Z., Yi Y., Wu Y. Z., Wu S., Zhu J., Wang J., Chen X. H., Zhang Y., Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q., Yang M., Gong C., Chopdekar R. V., N’Diaye A. T., Turner J., Chen G., Scholl A., Shafer P., Arenholz E., Schmid A. K., Wang S., Liu K., Gao N., Admasu A. S., Cheong S.-W., Hwang C., Li J., Wang F., Zhang X., Qiu Z. Q., Patterning-induced ferromagnetism of Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals materials beyond room temperature. Nano Lett. 18, 5974–5980 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang M., Li Q., Chopdekar R. V., Stan C., Cabrini S., Choi J., Wang S., Wang T., Gao N., Scholl A., Tamura N., Hwang C., Wang F., Qiu Z. Q., Highly enhanced curie temperature in Ga-implanted Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals material. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2, 2000017 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fei Z., Huang B., Malinowski P., Wang W., Song T., Sanchez J., Yao W., Xiao D., Zhu X., May A. F., Wu W., Cobden D. H., Chu J.-H., Xu X., Two-dimensional itinerant ferromagnetism in atomically thin Fe3GeTe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 778–782 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong Q., Liu F., Xiao J., Yao W., Skyrmions in the Moiré of van der Waals 2d magnets. Nano Lett. 18, 7194–7199 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Shi M., Mo P., Lu J., Electrical-field-induced magnetic Skyrmion ground state in a two-dimensional chromium tri-iodide ferromagnetic monolayer. AIP Adv. 8, 055316 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Behera A. K., Chowdhury S., Das S. R., Magnetic skyrmions in atomic thin CrI3 monolayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 232402 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han M.-G., Garlow J. A., Liu Y., Zhang H., Li J., DiMarzio D., Knight M. W., Petrovic C., Jariwala D., Zhu Y., Topological magnetic-spin textures in two-dimensional van der Waals Cr2Ge2Te6. Nano Lett. 19, 7859–7865 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding B., Li Z., Xu G., Li H., Hou Z., Liu E., Xi X., Xu F., Yao Y., Wang W., Observation of magnetic Skyrmion Bubbles in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Nano Lett. 20, 868–873 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.T. Park, L. Peng, J. Liang, A. Hallal, X. Zhang, S. J. Kim, K. M. Song, K. Kim, M. Weigand, G. Schuetz, S. Finizio, J. Raabe, J. Xia, Y. Zhou, M. Ezawa, X. Liu, J. Chang, H. C. Koo, Y. D. Kim, M. Chshiev, A. Fert, H. Yang, X. Yu, S. Woo, Observation of magnetic skyrmion crystals in a van der Waals ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2 arXiv:1907.01425 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci] (2019).

- 31.Y. Wu, S. Zhang, G. Yin, J. Zhang, W. Wang, Y. L. Zhu, J. Hu, K. Wong, C. Fang, C. Wang, X. Han, Q. Shao, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, J. Zang, Z. Mao, X. Zhang, K. L. Wang, Néel-type skyrmion in WTe2/Fe3GeTe2 van der Waals heterostructure. arXiv:1907.11349 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci] (26 July 2019).

- 32.H. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Zhu, Z.-A. Li, H. Zhang, H. Tian, Y. Shi, H. Yang, J. Li, Direct observations of chiral spin textures in van der Waals magnet Fe3GeTe2 nanolayers. arXiv:1907.08382 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci] (19 July 2019).

- 33.Bloemen P. J. H., de Jonge W. J. M., Determination of the ferromagnetic coupling across Pd by magneto-atomic engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 4522 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakajima N., Koide T., Shidara T., Miyauchi H., Fujimori A., Iio K., Katayama T., Nývlt M., Suzuki Y., Perpendicular magnetic anisotropy caused by interfacial hybridization via enhanced orbital moment in Co/Pt multilayers: Magnetic circular x-ray dichroism study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5229–5232 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tudu B., Tian K., Tiwari A., Effect of composition and thickness on the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy of (Co/Pd) multilayers. Sensors 17, 2743 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W., Upadhyaya P., Zhang W., Yu G., Jungfleisch M. B., Fradin F. Y., Pearson J. E., Tserkovnyak Y., Wang K. L., Heinonen O., te Velthuis S. G. E., Hoffmann A., Blowing magnetic skyrmion bubbles. Science 349, 283–286 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollard S. D., Garlow J. A., Yu J., Wang Z., Zhu Y., Yang H., Observation of stable Néel skyrmions in cobalt/palladium multilayers with Lorentz transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 14761 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benitez M. J., Hrabec A., Mihai A. P., Moore T. A., Burnell G., McGrouther D., Marrows C. H., McVitie S., Magnetic microscopy and topological stability of homochiral Néel domain walls in a Pt/Co/AlOx trilayer. Nat. Commun. 6, 8957 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ophus C., Ewalds T., Guidelines for quantitative reconstruction of complex exit waves in HRTEM. Ultramicroscopy 113, 88–95 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/36/eabb5157/DC1