Abstract

Human galectin-7 (Gal-7; also termed p53-induced gene 1 product) is a multifunctional effector by productive pairing with distinct glycoconjugates and protein counter-receptors in the cytoplasm and nucleus, as well as on the cell surface. Its structural analysis by NMR spectroscopy detected doubling of a set of particular resonances, an indicator of Gal-7 existing in two conformational states in slow exchange on the chemical shift time scale. Structural positioning of this set of amino acids around the P4 residue and loss of this phenomenon in the bioactive P4L mutant indicated cis–trans isomerization at this site. Respective resonance assignments confirmed our proposal of two Gal-7 conformers. Mapping hydrogen bonds and considering van der Waals interactions in molecular dynamics simulations revealed a structural difference for the N-terminal peptide, with the trans-state being more exposed to solvent and more mobile than the cis-state. Affinity for lactose or glycan-inhibitable neuroblastoma cell surface contact formation was not affected, because both conformers associated with an overall increase in order parameters (S2). At low µM concentrations, homodimer dissociation is more favored for the cis-state of the protein than its trans-state. These findings give direction to mapping binding sites for protein counter-receptors of Gal-7, such as Bcl-2, JNK1, p53 or Smad3, and to run functional assays at low concentration to test the hypothesis that this isomerization process provides a (patho)physiologically important molecular switch for Gal-7.

Keywords: apoptosis, lectin, molecular dynamics, NMR relaxation, NMR spectroscopy, site-directed mutagenesis

Introduction

Screening for up- or down-regulation of expression of distinct genes upon changing a specific parameter is a robust approach to identify key aspects of the cascade leading to a triggered cellular response. When monitoring the impact of viral transformation (by SV40 of human keratinocytes), chemical carcinogenesis (by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene on rat mammary carcinomas) and induction of p53 (in human colon adenocarcinoma (DLD-1) cells), a marked effect was noted for expression of a gene/protein assigned to the family of galectins, i.e. galectin-7 (Gal-7) [1–3]. In fact, due to its conspicuous up-regulation, it has even been referred to also as p53-induced gene 1 product [3]. These ga(lactose-binding)lectins are multifunctional proteins that have first been delineated to serve as molecular bridge by binding to β-galactoside epitopes of glycan chains of cellular glycoconjugates and then to mediate a wide variety of cellular activities by this functional pairing [4–8]. Beyond this role as ‘readers’ and ‘interpreters’ of glycan-based signals within the concept of the sugar code [9,10], galectins also target peptide motifs, among them distinct cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins [11,12]. The common absence of a signal peptide allows galectins to gain access to the cytoplasm, and transport mechanisms ensure routing to the nucleus or their non-classical secretion [13–17]. Indeed, immunohistochemical studies show such a distribution profile for Gal-7 in cells and tissues (for examples, please see [18–20]). As take-home message, galectins form a versatile platform for recognition processes for different types of ligands.

Functionally, Gal-7 is intimately involved in growth regulation, as illustrated, for example, by the response to ectopic expression in UV-exposed keratinocytes or in the mentioned DLD-1 tumor cells [18,21,22]. Toward this end, either glycans (as cell surface counter-receptors) [23,24], binding partners intracellularly upstream of JNK activation, or even products of Gal-7-dependent modulation of gene expression [18], come into play. Broadening its activity profile, pro-tumoral effector mechanisms have also been documented, highlighting the context-dependent nature of the outcome of the presence of Gal-7 [25,26]. Since the list of proteins that are intracellular binding partners has remarkably grown over the years, now including such potent effectors as the transcription factor Smad3 [27], p53 [28], Bcl-2 [29], E-cadherin [30] and JNK1 [31], elucidating the structural aspects of these interactions has become an important issue. Toward this end, structural characterization of Gal-7 in solution is imperative.

Having reported NMR-spectroscopical assignments [32] and initial binding studies with the canonical ligand lactose [33], we observed unexplained pairs of resonances that intrigued us. Here, we can attribute these pairs to cis/trans isomerization indirectly by engineering and processing a loss-of-function mutant (i.e. P4L) and directly by making specific resonance assignments for each isomer state. The cis/trans-states differ in the presentation of the N-terminal section which profoundly affects its local vicinity. Furthermore, the monomeric state of Gal-7 is promoted at low µM protein concentrations when P4 is in its cis-state. In contrast, the lactose binding-induced overall gain in conformational entropy is not affected by P4 isomerization.

Experimental

Galectin engineering, production and isotopic labeling

Primer design was based on the sequence from Genbank Accession No. NM_002307.3, the sense primer for wild-type Gal-7 was 5′-CGCTAGCATATGTCCAACGTCCCCCACAAG-3′ (NdeI restriction site underlined), the sense primer for the single-site Gal-7 mutant P4L 5′-CGCTAGCATATGTCCAACGTCCTCCACAAG-3′ (NdeI restriction site underlined, changed nucleotide in bold), the antisense primer in both cases was 5′-CGTACGAAGCTTTCAGAAG-ATCCTCACGGA-3′ (HindIII restriction site underlined). For PCR amplification, a pQE-60/Gal-7 plasmid was used as a template [18], the respective PCR products were ligated in-frame into the pET-24a (Novagen®, Sigma–Aldrich, Munich, Germany) expression vector linearized by NdeI/HindIII directing protein generation in the Escherichia coli strain RosettaBlueTM(DE3)pLys S (Novagen®). Optimal yields of protein (wild-type Gal-7 ≈ 100–110 mg/l, for Gal-7 mutant P4L ≈ 80–90 mg/l of culture medium) were obtained in a two-step procedure using first LB medium (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) containing 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at 37°C overnight, then (with resuspended bacterial pellets) M9 minimal medium (enriched with [15N]NH4Cl and/or U-[13C]glucose as medium additive(s)) and induction with 200 µM IPTG at 37°C for 16 h. The suspensions were centrifugated, and cells were lysed by the freeze–thaw approach using 7 ml of buffer (20 mM phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 2 mM EDTA and 4 mM β-mercaptoethanol) per gram wet cell paste. After centrifugation to pellet debris, the supernatant was fractionated by affinity chromatography on home-made lactosylated Sepharose 4B as a crucial step of purification, using buffer with 0.1 M lactose for elution, removing the sugar by several rounds of ultrafiltration and a final gel filtration, and the proteins were checked for purity and activity as previously described [23].

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments

NMR spectra were measured on a Varian Unity Inova 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance probe and x/y/z triple-axis gradient unit. Sequence-specific resonance assignments have been performed using a standard set of 3D NMR experiments, as described previously [34]. Interproton distance restraints were derived from NOEs assigned in 3D 15N-edited or 13C-edited NOESY spectra, obtained at mixing time of 150 ms. Hydrogen bond constraints were identified from the pattern of sequential and interstrand NOEs involving NH and CαΗ protons, and with evidence of slow amide proton-solvent (D2O) exchange, monitored with a series of 2D 1H–15N HSQC experiments. NMR spectra were processed using NMRPIPE [35] and visualized using NMRVIEW [36].

NMR residual dipolar couplings

A Gal-7 sample was prepared in a liquid crystalline phase at 7.5 mg/ml of 3 : 1 14-O-PC : 6-O-PC bicelles in 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.5. Lipids have been purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. Changes in splitting relative to the isotropic 1JNH values were measured at 800 MHz on 15N-labeled Gal-7 at 30°C by using in-phase anti-phase (IPAP) [1H,15N]-HSQC experiments [37].

NMR chemical shifts

To determine chemical shifts, 13C-filtered proton spectra were acquired with a resolution of 0.5 Hz. Chemical shifts were expressed in absolute frequency with no internal reference. Chemical shifts of amide 15N and 1H were measured from 2D 1H–15N HSQC, referenced against water resonance.

NH temperature factors were determined by acquiring 15N–1H HSQC spectra as a function of temperature and plotting 1H chemical shifts vs. the inverse temperature. The normally negative slopes of these curves provide temperature factors (units of ppb/K) that then suggest presence of hydrogen bonds when the value is relatively small.

NMR relaxation experiments

15N longitudinal [RN(NZ)] and transverse [RN(NX)] relaxation terms and heteronuclear NOE enhancements were determined for lactose-loaded and -free 15N-enriched Gal-7. Data were acquired at 1H frequencies of 600 and 800 MHz essentially, as described previously [40–42]. RN(NZ) and RN(NX) were derived by fitting data collected with different relaxation delays to a single exponential decay function, and errors were determined by repeating single data points as we described earlier. Two sets of spectra were recorded for steady-state NOE intensities, one with 3-s proton saturation to achieve steady-state intensities and the other as a control spectrum with no saturation to obtain the initial intensity. NOE enhancements were calculated from the ratios of these intensities. Data for each Gal-7 state (lactose free and loaded) were analyzed using the Lipari–Szabo model free approach [43].

NMR structure calculations

Initial structures were calculated using the program XPLOR-NIH [49]. Starting with random co-ordinates, simulated annealing was carried out based on NOE distance restraints, dihedral angles, carbon chemical shifts and residual dipolar coupling (RDC) restraints using XPLOR-NIH protocols. Distance restraints were grouped into three ranges: 1.8–2.9 Å (strong), 1.8–3.3 Å (medium) and 1.8–5.0 Å (weak). For each hydrogen bond identified, two distance constraints were used: 1.6–2.4 Å for H–O constraints and 2.6–3.4 Å for N–O constraints. A total of 100 random structures were subjected to 24 k simulated annealing and cooling steps of 0.005 ps. From these structures, ten energy-minimized structures were selected based on the absence of NOE violations greater than 0.2 Å, dihedral angle violations greater than 5° and residual dipolar constants greater than 0.5 Hz.

The HADDOCK 2.0 program [50] was used to perform simultaneous docking of two lactose molecules to the Gal-7 homodimer. Based on NOEs between lactose and Gal-7, chemical shift changes induced by lactose binding and solvent-accessibility calculations, amino acid residues were set as active or passive. NOE distance restraints between Gal-7 and lactose were used as unambiguous restraints. Amino acid residues at the interface allowed switching between active and passive residues ±2 sequential residues. The docking procedure was performed in three steps using default parameters in HADDOCK and symmetry restraints with force constants equal to 300 kcal/mol: (1) randomization and rigid body energy minimization, (2) semi-flexible simulated annealing and (3) flexible explicit solvent refinement. Initially, 1000 structures were generated in the rigid body docking, and subsequently, the 100 best structures were selected for further semi-flexible simulated annealing, and then for the final refinement in the presence of explicit water. To produce final structures, we refined the minimum energy-minimized structures for lactose-loaded and -free Gal-7 in explicit solvent using the program NAMD2.6 [51].

NMR diffusion coefficients

Diffusion coefficients were measured on a Varian Unity Inova 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with an H/C/N triple-resonance probe and x/y/z triple-axis pulse field gradient unit. The maximum magnitude of the gradient, g, was calibrated using Varian deuterated water standard. Measurements were performed, as described before [38,39]. The value of the diffusion coefficient was estimated from the diffusion attenuation of spin-echo by using eqn (1).

| 1 |

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio for protons, δ is the duration of the pulsed field gradient and td is the diffusion time, which comprises all time delays between pulses, during which the magnetization is aligned along z-axis.

Mass spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry was applied for molecular mass determination and peptide mass fingerprinting using trypsin, as previously described [44,45]. Each protein sample was dissolved in water to a final concentration of 4 µg/µl. For molecular mass determination with sinapinic acid (SA) as matrix, the protein-containing sample was further diluted with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (1:5, v/v). 0.5 µl of a saturated solution of SA in ethanol was pipetted on individual spots of the MALDI target. After drying, 1 µl of protein solution was added on top of the thin SA layer, immediately followed by 1 µl of a saturated solution of SA in 0.1% TFA with 30% acetonitrile (TA30). For peptide fingerprinting, the protein (10 µg in 10 µl 40 mM NH4HCO3) was first treated with 2 µl of a 10 mM solution of dithiothreitol (DTT) in 40 mM NH4HCO3 at 45°C for 1 h to completely reduce disulfide bonds. The thiol groups were then alkylated by addition of 1 µl of a solution of 55 mM iodoacetamide in 40 mM NH4HCO3 at 25°C for 30 min and after adding 2.5 µl 10 mM DTT, the mixture was incubated for 15 min at 37°C to let all iodoacetamide react with the thiol group.

Tryptic digestion was performed with 100 ng trypsin in 40 mM NH4HCO3 solution overnight at 37°C. Digest mixtures were desalted with reversed phase ZipTipC-18. ZipTipC18 pipette tips were wetted three times with 10 μl TA50 (50% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA), followed by three washes with 10 μl 0.1% TFA. Peptides were then adsorbed onto the tip by repeatedly drawing the sample solution through the ZipTip, followed by three washes with 0.1% TFA to remove salts. Sample was eluted with 2 µl of a saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid in TA50 and directly spotted on the MALDI target. All matrices were obtained from Bruker Daltonik (Bremen, Germany). Spotted samples were dried at ambient temperature prior to mass spectrometric analysis. MALDI mass spectra were collected on an Ultraflex™ TOFTOF I instrument (Bruker Daltonik) equipped with a nitrogen laser (20 Hz) using settings and calibration as described [44,45]. FlexControl version 2.4 was used for instrument control, and FlexAnalysis version 2.4 for processing the data of the spectra. Annotated spectra were further analyzed by using the program BioTools 3.0 (Bruker Daltonik).

Cell binding and proliferation assays

Neuroblastoma cells (strain SK-N-MC) were cultured at 37°C in Eagle'sminimal essential medium with 10% fetal calf serum (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) and non-essential amino acids in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells grown to confluency in 96-well tissue culture plates for five days (∼105 cells/well) were incubated for 16 h in medium without fetal calf serum. For the binding assays, serum-free Eagle's minimal essential medium (100 μl/well) with 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.01% bovine serum albumin was used to block protein-binding sites, and the labeled galectins (specific radioactivities (150 kBq/µg for galectin-7 and 144 kBq/µg) at non-saturating concentrations. Protein iodination, measurement of carbohydrate-inhibitable binding of 125I-labelled Gal-7 proteins to the cultured cells and data processing followed an optimized procedure [46].

Cell proliferation in the presence or absence of a Gal-7 protein was examined in 96-well tissue plates (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany) by culturing cells in 100 µl medium for 48 h at 37°C and measuring cell growth with a cell proliferation kit (CellTiter-96, Promega, Heidelberg, Germany), as described previously [47,48]. The effect of the presence of 25 µg cholera toxin B-subunit (Ctx-B; Sigma) was examined after co-incubation with the tested galectin [47,48].

Results

Cis–trans isomerization at P4 reflected in HSQC spectra

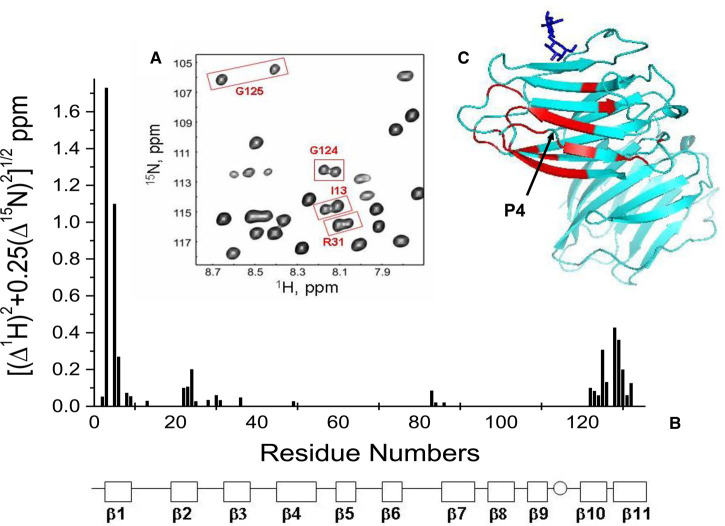

The occurrence of two sets of resonances for distinct amino acids of Gal-7 is exemplified in the HSQC expansion in Figure 1A. It identifies doubled resonances arising from G124, G125, I13 and R31. For the most part, these resonance pairs originate from amino acids at the N- and C-termini that involve β-strands 1, 10 and 11 as well as from residues of proximal β-strands and loops at one side of the β-sandwich. In addition, a few more come from distinct sets of other amino acids, i.e. N36 (β-strand 3), L49 (β-strand 4) as well as R83, G84 and F87 (loop 6 between β-strands 6 and 7). These moieties are in close vicinity to the β-strands 2 and 10. All of the observed doubled resonances are documented in Figure 1B, where 15N–1H-weighted chemical shift differences, Δδ, between cross peak pairs are plotted vs. the amino acid sequence of Gal-7. The residues are highlighted in the crystal structure in one of the subunits of the Gal-7 homodimer (PDB 4GAL), graphically providing an overview on the sites affected (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. HSQC spectra of Gal-7 showing resonance doubling.

(A) Expansion of a 15N–1H HSQC spectrum of Gal-7 with some doubled resonances boxed in and labeled, as discussed in the text. (B) 15N–1H-weighted chemical shift differences, Δδ, between cross peak pairs are plotted vs. the amino acid sequence of Gal-7. The 11 β-strands in Gal-7 are identified at the bottom of the figure. (C) The structure of Gal-7 (PDB access code 4GAL) highlights in red residues showing doubled resonances. A molecule of bound lactose is shown in dark blue for structural orientation.

To exclude the presence of a post-translational modification in at least a part of the protein fraction as cause for this phenomenon, Gal-7 was rigorously tested by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, the peaks of both recombinant Gal-7 produced with regular and with 15N-labeling media appear at the position calculated for unmodified Gal-7 and at 15 120 Da for the 15N-labeled protein. Since the total number of nitrogen atoms in Gal-7 is 201, a complete labeling would produce a mass of 15 146 Da. Thus, extent of labeling reached ∼87% efficiency. The ensuing peptide mass fingerprinting adds validity to this result. Calculated and experimentally determined values (at a sequence coverage of 91.1% (regular) and 83% (15N-labeled)) agreed with each other well (Supplementary Figure S2). The spectral resolution revealed an expectable heterogeneity due to different isotopic abundance (Supplementary Figure S3). These data confirm and extend (to the level of peptide fingerprinting) the initial observation of the absence of any modification for recombinant Gal-7 by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry [23]. This definitive evidence directs attention to examining the possibility of the presence of two different conformations resulting from peptide bond isomerization.

As illustrated in Figure 1A, the two resonances in each pair are in slow exchange so that the energy barrier between two conformational states must be quite high and cannot be attributed to differences in rapid internal motions. With this in mind, the most acceptable explanation is a cis/trans-isomerization at a proline moiety that manifests a slow exchange on the chemical shift time scale, and the data on affected residues given above guided the search using human Gal-7's crystal structure to trace an elicitor [52]. Fittingly, one proline is positioned at the center of the group of residues, whose resonances undergo resonance doubling, i.e. the one at position 4 (labeled P4 in Figure 1C). We tested this proposal of involvement of such a process by engineering a site-specific Gal-7 mutant, in which P4 was replaced with a leucine to generate the P4L mutant that should adopt a single stable conformational state. Supplementary Figure S4 compares HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled P4L mutant (red peaks) and 15N-labeled wild-type Gal-7 (black peaks). A few regions where doubled signals were previously observed, are boxed in to show that these have been converted to single peaks. This comparison demonstrates that doubled peaks are no longer present in the HSQC spectrum of the P4L mutant, demonstrating that the observed conformational change in wild-type Gal-7 rests in cis–trans isomerization at P4, the stereochemistry at this site acting as a molecular switch.

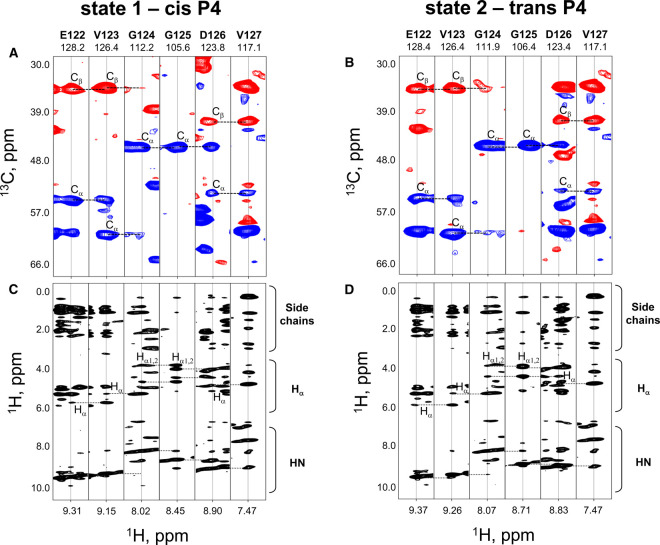

For insight into this isomerization process, we next assigned each resonance in a pair to either the cis or the trans configuration at this position. At first, we grouped resonances in each pair by making sequence-specific assignments using HNCACB data. Results of this approach are illustrated in Figure 2A,B. These panels show strip plots for the selected amino acid sequence from E122 to V127. They disclose that G124, G125 and D126, each showing doubled resonances, can be grouped as labeled. At this point, we could only refer to these groupings as state 1 and state 2. Assignment of the two states to the peptide bond toward P4 in either the cis or the trans-state was then done by determining chemical shifts of P4-derived resonances in HNCACB spectra and by analyzing 13C-edited and 15N-edited NOESY data in detail. For example, in the trans-isomer of this peptide bound, relatively strong NOEs were observed between P4 δH2 and V3 αH (and βH2) resonances (i.e. Cαi−1Hαi−1/CδiHδi), whereas NOEs were detected between the P4 αH and V3 αH resonances (i.e. Cαi−1Hαi−1/CαiHαi) in the cis-state. In addition, the following parameter could be exploited for reaching a definitive assignment: 13C chemical shifts for P in both configurations are known to differ significantly, especially the chemical shift difference between 13Cβ and 13Cγ groups, as already documented in great detail [53–57]. Analyzing our respective NMR data accordingly allowed us to make isomer state-specific assignments for the resonances in each pair, which are listed in Table 1. The validity of these assignments is supported by examining intensities for resonances within each pair and comparing them with the expectable result. As previously reported, the trans-isomer state is normally the more populated one [58], and resonances listed for the trans-state in Table 1 were indeed observed as such.

Figure 2. HNCACB spectra used for resonance assignments.

(A,B) Strip plots from an HNCACB experiment taken at the amide 15N and 1H chemical shifts of residues E122-V127 are shown for conformational states 1 (cis P4, A) and 2 (trans P4, B), as discussed in the text. Chemical shifts of Cα (blue cross-peaks) and Cβ (red cross-peaks) atoms are indicated on the vertical axis. Horizontal dotted lines indicate sequential connectivity. (C,D) Strip plots from a 15N-HSQC-NOESY experiment taken at the amide 15N and 1H chemical shifts of the same residues as in panels (A) and (B) for Gal-7 P4 cis (C) and trans (D) states. 1H chemical shifts are indicated on the vertical axis, and horizontal dotted lines show sequential connectivity.

Table 1. Resonance assignments for residues showing doubled resonances due to trans- and cis- at P4.

| P4 trans-state | P4 cis-state | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 15N | 1H | 15N | |

| 3 | 8.3368 | 122.8398 | 7.92864 | 115.9922 |

| 5 | 8.83915 | 120.9279 | 9.30426 | 124.5026 |

| 6 | 7.9543 | 125.2998 | 8.01535 | 126.4543 |

| 13 | 8.14318 | 114.7628 | 8.18224 | 114.9321 |

| 22 | 8.55584 | 125.8294 | 8.65653 | 125.8342 |

| 23 | 6.98164 | 110.024 | 6.93921 | 109.6225 |

| 25 | 7.81349 | 126.8022 | 7.77497 | 126.9239 |

| 25 | 7.81349 | 126.8022 | 7.77497 | 126.9239 |

| 28 | 8.00783 | 112.7664 | 7.95931 | 112.6913 |

| 30 | 9.77288 | 116.5473 | 9.82884 | 116.5161 |

| 31 | 8.1364 | 116.2752 | 8.09591 | 116.1814 |

| 83 | 8.55182 | 112.3722 | 8.45364 | 112.3079 |

| 86 | 8.47241 | 115.4363 | 8.50488 | 115.4729 |

| 121 | 8.84909 | 123.6155 | 9.39105 | 128.3833 |

| 123 | 9.20225 | 126.4689 | 9.28112 | 126.3715 |

| 124 | 8.14937 | 112.3163 | 8.09373 | 112.4715 |

| 125 | 8.67174 | 106.1385 | 8.41869 | 105.4444 |

| 126 | 8.83 | 123.4 | 8.9 | 123.8 |

| 127 | 7.49584 | 117.1904 | 7.49584 | 117.1904 |

| 128 | 8.00277 | 125.4523 | 8.11128 | 127.0734 |

| 129 | 8.7866 | 125.9289 | 8.96463 | 127.1541 |

| 130 | 9.022 | 125.5756 | 8.98959 | 124.889 |

| 132 | 8.27756 | 122.7921 | 8.2541 | 122.3009 |

Structure and dynamics of the two isomer states at P4

The NMR solution structure of Gal-7 was determined by using 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY, 3JNH coupling constants for dihedral angles, RDCs and the chemical shift index, as well as HD exchange and NH temperature factors to identify likely hydrogen bonds. Strip plots from 15N-edited NOESY spectra for Gal-7 cis and trans states at P4 are exemplified and compared in Figure 2C,D, respectively. The set of inter-residue NOEs from either P4 isomer state is essentially the same, with generally lower NOE intensities for residues around P4 in the trans-state. Supplementary Figure S5A shows the temperature dependence of NH resonances in HSQC spectra acquired from 278 to 313 K, with some expansions provided in Supplementary Figure S5B–D. In either P4 isomer state, most resonances are shifted to the same extent, indicating the same potential to form hydrogen bonds. One clear exception is G125 (Supplementary Figure S5A boxed and S5B expanded), in which the signal for G125 NH in the trans-state changes little over this temperature range with a temperature factor of −2.2 ppb/K. In contrast, G125 NH in the cis-state exhibits a temperature factor of −6.8 ppb/K. In this regard, G125 in the trans-state is most probably involved in a hydrogen bond, whereas it is not in the cis-state. For the most part, NHs of the protein backbone that were identified as forming hydrogen bonds are correlated with β-strands involved in antiparallel β-sheet structures.

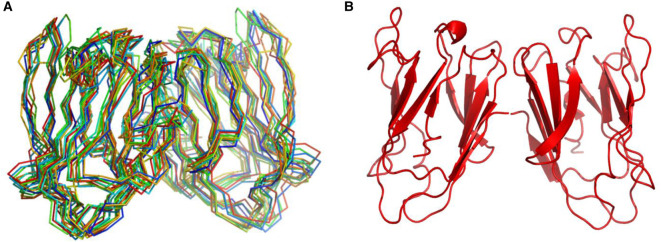

Using these NMR data, we calculated structures for Gal-7 in the cis- and trans-states at P4. Structural statistics are summarized in Table 2. Because Gal-7 is mostly dimeric at 400 μM [23,33,59] and HSQC data show the presence of only one set of resonances, the Gal-7 dimer in solution is symmetric as previously reported for the crystal structure of this lectin [52] (PDB code 4GAL). Because of this, we initially forced the Gal-7 dimer to remain symmetric during structural calculations. Moreover, several NOEs were observed between subunits, and this set of inter-subunit NOEs served as evidence for a single type of dimer being formed in either P4 isomer state. The 10 lowest energy-minimized Gal-7 structures out of 100 calculated exhibited root-mean-square deviations from the average structure of ∼0.6 Å for the β-sheet backbone Cα atoms and ∼1.1 Å for all non-hydrogen atoms (Table 2). The Cα traces of β-sheet-aligned structures for the apo-Gal-7 cis-state at P4 are superimposed in Figure 3A, along with a ribbon structure representation of the average structure in Figure 3B. Looking at the cis-based conformer, the hydrogen bond between N2 and G125 cannot form, consistent with the large negative NH temperature factor observed for Gal-7 in the P4 cis-state. However, the presence of more NOEs between N-terminal residues (residues 1–5) and the CRD β-sandwich in the P4 cis-state indicates that the N-terminus in the cis-state is more structurally integrated than in the trans-state. Aside from this N-terminal segment, the structures of Gal-7 in the cis- and trans-states at P4 are the same, and thus only the P4 cis-state is shown in Figure 3. In addition, our NMR solution structure of Gal-7 is the same as that reported for the crystal structure of the lectin [52] (PDB code 4GAL, backbone RMSD < 1 Å) in which P4 is in the trans-state in both subunits of the dimer.

Table 2. Structural statistics for NMR solution structures of Gal-7 in the P4 cis-state in the absence (apo-Gal-7) and presence of lactose (10 mM, holo-Gal-7).

| Parameter | apo-Gal-7 | holo-Gal-7 |

|---|---|---|

| Constraints per monomer | ||

| Intramolecular | ||

| NOE distance restraints (total) | 1659 | 1688 |

| Average number of NOE restraints per residue | 12 | 12 |

| Long-range (|i−j| > 4) | 511 | 525 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 69 | 69 |

| RDC | 67 | 67 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | 131 | 131 |

| Intermolecular | ||

| NOE distance restraints (total) | 18 | Interface: 24 Gal-7/lactose: 10 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 6 | 6 |

| Ramachandran statistics | ||

| Most-favorable region (%) | 80.7 | 73.7 |

| Additionally allowed region (%) | 16.7 | 23.2 |

| Generously allowed region (%) | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Disallowed region (%) | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| RMSD to the mean structure for the backbone atoms (Å) | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| RMSD to the mean structure for non-hydrogen atoms (Å) | 1.12 | 1.45 |

Structural statistics are essentially the same for Gal-7 in the P4 trans-state, albeit with several fewer NOEs and other constraints observed for N-terminal residues through L9.

Figure 3. NMR-based structures of Gal-7.

Superpositions of the ten lowest energy structures (Cα traces) are shown for lactose-free apo-Gal-7 dimer (A), along with the average structure of this Gal-7 dimer in Pymol ribbon format (B).

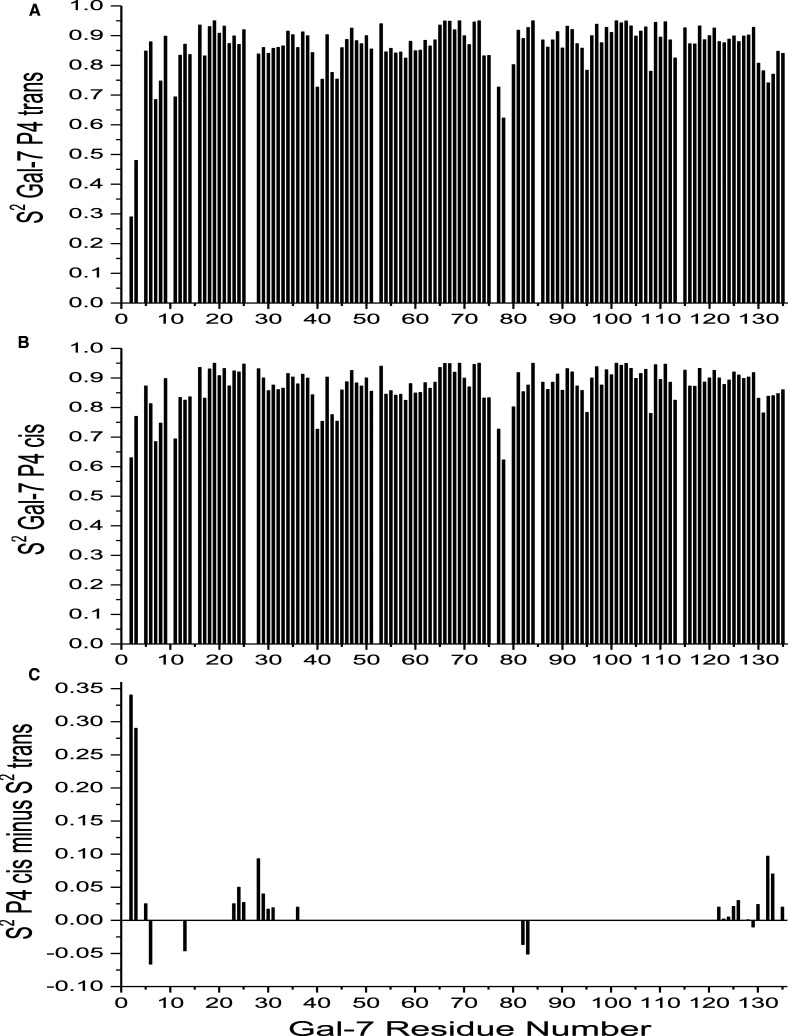

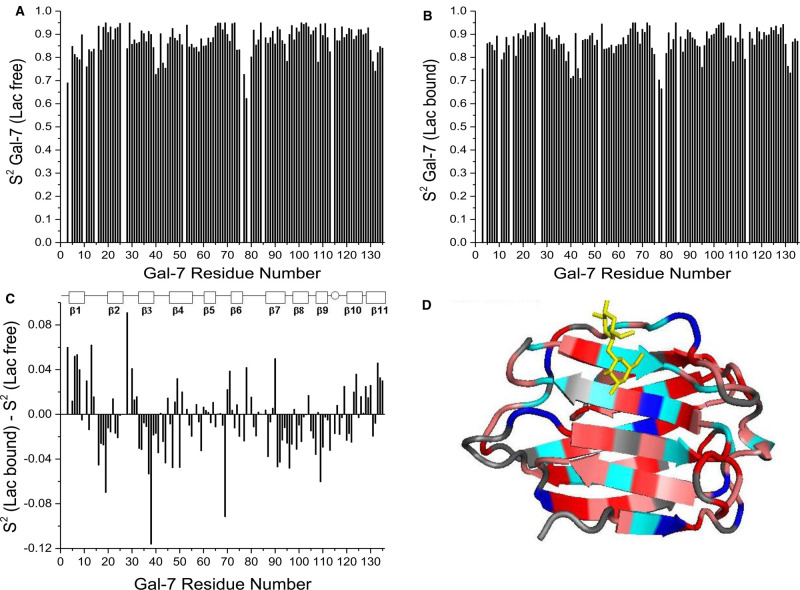

Because our Gal-7 structure is the same as those previously published, we focused attention on assessing internal motions of the backbone in Gal-7 P4 isomer states by using 1H–15N NMR relaxation data (T1, T2 and NOE) at 600 and 800 MHz and the Lipari–Szabo model free approach [43] to derive motional order parameters, S2, for all NH vectors. Figure 4A,B shows plots of S2 values for P4 trans- and cis-states vs. the amino acid sequence. Since average order parameters in both isomer states fall within the canonical range of 0.84–0.86, transient formation of Gal-7 dimers did not influence relaxation terms [60]. In general, backbone NH groups within β-strands are the most motionally restricted, whereas those at the N-terminus are relatively more mobile. On the other hand, C-terminal residues in β-strand 11, which is positioned behind the more mobile N-terminal β-strand-1, are relatively motionally restricted. Although trends in S2 are generally the same for residues in the trans- and -cis states at P4, there are significant differences as shown in Figure 4C that plots ΔS2 (trans-minus-cis) vs. the Gal-7 sequence. These data indicate that when P4 is in the cis-state, residues 3–6, 22–36 and 122–136 are more motionally restricted than they are in the trans-state. This observation is consistent with increased folding interactions between the N-terminus in the P4 cis-state and the main body of the CRD (see Figure 1).

Figure 4. Motional order parameters derived from NMR relaxation data.

Internal motions in Gal-7 conformational states were assessed by acquiring 1H–15N NMR relaxation data (T1, T2 and NOE) at 600 and 800 MHz, and were analyzed by using the Lipari–Szabo model free approach [43] to derive motional order parameters, S2, for all NH vectors. (A) S2 values for P4 trans-state vs. the amino acid sequence. (B) S2 values for P4 cis-state vs. the amino acid sequence. (C) ΔS2 values (trans-minus-cis) vs. the Gal-7 sequence showing that differences are primarily localized around P4 and the P4 cis-state is more motionally restricted.

Holo-Gal-7: structure, dynamics and lactose affinity

As with apo-Gal-7, we also collected NMR data on lactose-loaded Gal-7 (i.e. 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY, 3JNH coupling constants, chemical shift index and HD exchange). With the exception of chemical shifts of residues at the lactose binding site, the set of inter-residue NOEs, 3JNH coupling constants and HD exchange parameters were effectively the same for apo- and holo-Gal-7 in both P4 isomer states. Because of this, calculated structures for holo-Gal-7 varied little from those of apo-Gal-7. Structural statistics for holo-Gal-7 (Table 2), however, indicate that the calculated structure for apo-Gal-7 is somewhat better defined than that for holo-Gal-7. The reason for this apparently rests in differences in structural dynamics, with holo-Gal-7 exhibited greater internal mobility as observed for Gal-1 [62].

Lipari–Szabo model free analysis [43] of 1H–15N NMR relaxation data (T1, T2 and NOE) with lactose-loaded Gal-7 yielded motional order parameters, S2, for all NH vectors. Plots of S2 values for lactose-free and -loaded Gal-7 vs. the amino acid sequence of Gal-7 are shown in Figure 5A,B. Whereas trends in S2 values for holo-Gal-7 parallel those for apo-Gal-7, there are differences as shown in Figure 5C, with alterations highlighted in color on the Gal-7 structure in Figure 5D (red and pink for increased mobility, and blue and cyan for decreased mobility). Note that the binding of lactose to Gal-7 generally increases backbone mobility throughout the structure, with the exception of residues at the lactose binding site itself. This observation is the same as that found with Gal-1 [62]. Using equations reported previously that relate changes in S2 to conformational entropy, ΔS [61], we find that, for lactose binding to Gal-7, ΔS/k is +0.1/residue. In regions with the largest differences in S2, ΔS/k increases to +0.18/residue. Residues within and around the lactose-binding site and of the N- and C-termini are exceptions, where ΔS/k is −0.07/residue and −0.09/residue, respectively. As noted previously with Gal-1 [62], conformational entropy of the lectin is increased upon ligand binding, and thus contributes to a positive entropy term (ΔS) to reduce the extent of entropic penalty within the enthalpy-driven process of lactose binding, as reported by isothermal titration calorimetry for Gal-7 testing di-, tetra- and hexasaccharides (N-acetyllactosamine and its di- and trimers), as well as for the glycoprotein asialofetuin [63,64].

Figure 5. NMR-derived motional order parameters.

Order parameters, S2, for lactose-free (A) and lactose-loaded (B) Gal-7 P4 trans-states vs. the amino acid sequence. (C) The difference in order parameters, ΔS2 [calculated as S2 for lactose-free minus S2 for lactose-loaded protein] is shown vs. the Gal-7 amino acid sequence. These terms were derived from T1 and T2 relaxation times and NOE values determined at 600 and 800 MHz and analyzed by using the Lipari–Szabo model free approach as discussed in the text. A positive ΔS2 value indicates more restricted motion for an NH vector of that residue in the lactose bound state, and a negative ΔS2 value indicates less restricted motion for an NH vector in that residue in the lactose bound state. (D) Crystallographic structure of Gal-7 (PDB access code 4GAL) highlights differences shown in panel (C), with negative ΔS2 values highlighted in shades of red and positive ΔS2 values highlighted in shades of blue. Gray indicates not significant change. A molecule of bound lactose is shown in yellow for structural orientation.

Having identified cis/trans-isomerization at P4 to generate two Gal-7 conformers in slow exchange on the NMR chemical shift time scale, we could refine analysis of ligand binding by this lectin in two structural states. Previously, we reported that lactose binds to Gal-7 with positive cooperativity [33], where the first step has an equilibrium association binding constant (K1) of 4 ± 2 × 103 M−1, followed by association of the second lactose molecule with K2 = 17 ± 7 × 103 M−1, and this by looking at signals for the trans-state conformer. Here, we found that the affinity of lactose for the Gal-7 P4 cis-state is the same as that for the trans-state, with either state exhibiting positive cooperativity in ligand binding. This indicates that P4 cis/trans-isomerization has no significant effect on affinity for the canonical glycan ligand. By performing a titration with lactose on the Gal-7 P4L mutant, we also found no significant difference in affinity constants for lactose binding of Gal-7 as a single conformer (data not shown).

Cell binding and growth-inhibitory activity of wild-type Gal-7 and its P4L mutant

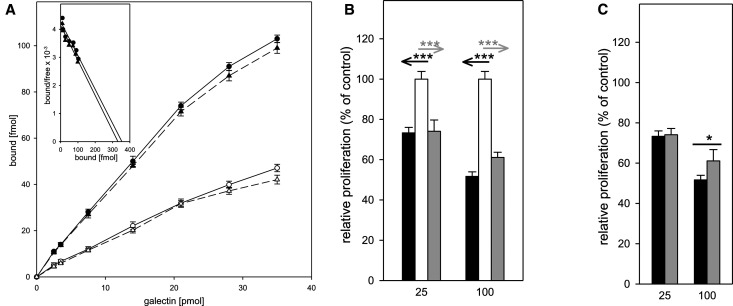

Having analyzed lactose binding to wild-type Gal-7 and its P4L mutant, we addressed the question of whether removal of the P4 conformational switch affects binding to a physiological glycan counter-receptor in cell assays. Based on our previous observation that Gal-7 is a receptor for the pentasaccharide of ganglioside GM1 for differentiating human neuroblastoma (SK-N-MC) cells and that this pairing induces growth inhibition [23], we performed a Scatchard analysis of glycan-inhibited cell-surface binding using radio-iodinated wild-type Gal-7 and its P4L mutant. The interaction of GM1 with human galectins has been thoroughly characterized in solution and in silico by docking analysis. The evidence that GM1 is a counter-receptor for galectins on human neuroblastoma (SK-N-MC) cells has been extended to Gal-7, and the application of a so-called neoganglio-protein presenting the GM1 lysoganglioside on albumin demonstrated the physical interaction of Gal-7 with GM1 in a carbohydrate-inhibitable manner with a KD-value of 2.29 ± 1.27 µM [23] and to other members of the galectin family [46]. Thus, our Scatchard analysis determines the affinity of a proven cell surface-presented ligand. As shown in Figure 6A, the resulting affinity is 814 ± 152 nM for wild-type and 761 ± 121 nM for P4L, values that are similar. The presence of a ganglioside GM1 receptor, i.e. cholera toxin B-subunit, at 25 µg/ml reduced the extent of binding (Figure 6A, dashed lines), as target selection by Gal-7 in this cell system was expected.

Figure 6. Effect of lectins on neuroblastoma cell growth.

(A) Binding of iodinated Gal-7-WT (●, solid line) and Gal-7-P4L (▴, solid line) to the surface of human neuroblastoma cells was quantitated for cells cultured in 96-well plates for five days (final density: 105 cells per well) prior to adding of the iodinated probe. Results are the means of three independent experiments ± SD. Binding was also measured in the presence of 0.25 mg/ml Ctx B: Gal-7-WT + Ctx (○, dashed line), Gal-7-P4L + Ctx B (Δ, dashed line). Inset, Scatchard plots. These experiments were performed in 96-well plates with 100 µl of medium. To display original results, the binding diagram shows the total amount of free ligand in 100 µl vs. the amount of ligand bound to cells. These data were used to calculate numbers for the Scatchard plot. Consequently, the KD (that is read directly from the Scatchard plot) has the dimension of fmol/100 µl. However, to express the result as a molar concentration, we expanded this to fmol/l: fmol/100 µl = fmol × 104/100 µl × 104 = fmol/l. Since this resulted in relatively high values, we converted the molar concentration representing the KD value to nM = nmol/l, that is nmol/l = fmol × 10−6/l. (B,C) Effects of lectins on neuroblastoma cell growth were measured in proliferation assays after 48 h incubation in the presence of wild-type Gal-7 (black bar) or the P4L variant (gray bar), using untreated cultures in parallel as control, set to 100% and as reference (B). Statistical evaluation of the two data sets in direct comparison is given in (C). Results are the means of four independent experiments ± SD, level of significance is graded into three categories: * 0.05 ≥ P > 0.01, ** 0.01 ≥ P ≥ 0.005 and *** P < 0.005.

Next, we tested the two proteins for their effects on cell proliferation. Induction of growth inhibition was indistinguishable at 25 µg/ml, whereas the wild-type protein was more active than its P4L mutant at 100 µg/ml (Figure 6B,C). Although the affinity of cell binding was indistinguishable, the efficiency of blocking cell growth that depends on lattice formation on the cell surface at the higher concentration, appeared to be somewhat different, suggesting an impact of the mutation on characteristics and/or activity of surface cluster arrangements required to cause the experimental read-out.

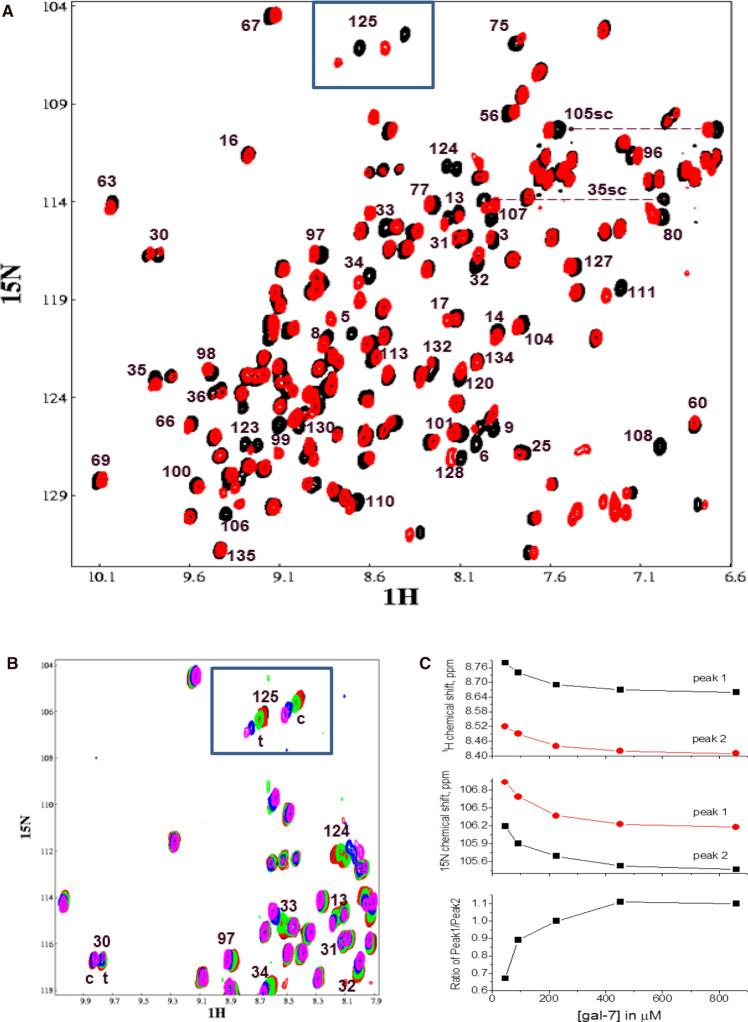

Isomer states at P4 influence the Gal-7 monomer–dimer equilibrium

During this study, we observed a dependence of cis/trans-originating resonance intensities from P4 on the Gal-7 concentration. Figure 7A shows an HSQC spectrum of 15N-labeled Gal-7 at 680 μM (black peaks) overlaid with that of Gal-7 at 40 μM (red peaks). At the higher Gal-7 concentration, resonance intensities of the trans- and cis-states (e.g. boxed G125 resonances at the top of the HSQC) are nearly equal. At the lower Gal-7 concentration, residues in the P4 cis-state display relatively greater resonance intensities. Figure 7B presents overlaid expansions of these HSQC spectra (boxed G125 resonances) at several Gal-7 concentrations. Figure 7C plots the change in 1H (top panel) and 15N (middle panel) chemical shifts vs. the Gal-7 concentration for the best-resolved signal, i.e. G125, of the cis- and trans-isomer pair. At Gal-7 concentrations less than ∼400 μM, chemical shifts and resonance intensities for these peaks changed significantly, with concentration-dependent changes correlated with the trans/cis-derived intensity ratio (Figure 7C, bottom panel). This trend demonstrates that the population of Gal-7 in the cis-state at P4 is increased at lower protein concentrations at the expense of its trans-isomer state. Since Gal-7 is a homodimer at high concentrations, this concentration-dependent trend indicates a shift in the monomer–dimer equilibrium to the monomer state at the lower Gal-7 concentrations.

Figure 7. Effect of Gal-7 concentration on aggregate state.

(A) HSQC spectrum of 15N-labeled Gal-7 at 680 μM (black peaks) overlaid with that of Gal-7 at 40 μM (red peaks). Some of the peaks are labeled with the Gal-7 sequence number. (B) Overlays of expansions from HSQC spectra acquired at several Gal-7 concentrations: 40 μM (black peaks), 100 μM (red peaks), 210 μM (green peaks), 425 μM (blue peaks), 850 μM (magenta peaks). (C) The change in 1H (top panel) and 15N (middle panel) chemical shifts vs. the Gal-7 concentration for the G125 cis (labeled peak 1) and trans (labeled peak 2) isomer pair. The trans/cis intensity ratio vs. Gal-7 concentration is shown in the bottom panel.

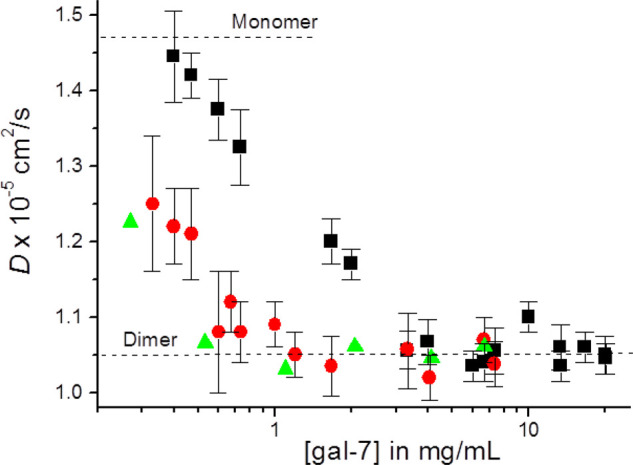

At first, this observation was unexpected, because we previously derived Kd values for Gal-7 dimer dissociation of ∼2 μM using FPLC gel filtration data [33]. For further insight into this issue, we performed 15N-edited PFG NMR experiments to determine the diffusion coefficient, D, as a function of Gal-7 concentration in the absence and presence of lactose (Figure 8). Dashed lines represent theoretical D values calculated using the Stokes–Einstein relationship [65]. At the highest Gal-7 concentrations, observed D values (∼1.05 × 10−6 cm2/s) are the same as the theoretical D value for the dimer state. As the Gal-7 concentration is reduced in the absence of lactose (apo-Gal-7, black squares), the D value is increased, as expected upon dimer dissociation and increasing populations of the smaller sized monomer. From these NMR diffusion data, we estimate that the monomer–dimer equilibrium constant, Kd, for apo-Gal-7 is ∼19 μM, the concentration at which populations of monomer and dimer are about equal. Our NMR-derived Kd value falls between those of 30 μM derived using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [33] and 10 μM derived using ultracentrifugation [23]. Moreover, the 50% dissociation point is about the mid-point in our plot of the trans/cis intensity ratio (Figure 7C, bottom panel), thus supporting the idea that Gal-7 monomers are favored when P4 is in its cis-state. Upon addition of lactose, the D value curve is shifted to lower Gal-7 concentrations (Figure 8), indicating greater stability of the Gal-7 dimer state and a shift to the trans-state at P4. This observation is consistent with our previous report that lactose binding stabilizes the Gal-7 dimer state [33]. Overall, our results indicate that isomerization at P4 affords the opportunity for Gal-7 to modulate its monomer–dimer equilibrium differently at low (probably physiological) concentrations.

Figure 8. Molecular diffusion measured by PFG-NMR.

15N-edited PFG NMR-derived diffusion coefficients, D, are plotted as a function of Gal-7 concentration in the absence of lactose (black squares) as well as in the presence of lactose at 10 mM (red circles) and at 25 mM (green triangles).

Discussion

The possibility to adopt various conformations affords a versatile means to broaden a protein's range of functions. Structural conversions depend on some type of molecular on/off switching mechanism. In the case of lectins, the existence of two conformational states had first been reported with metal ion (Ca2+, Mn2+) binding to concanavalin A [66,67]. Instead of being involved in coordination bonding with the glycan [68], these metal ions induce a series of conformational changes that eventually shaped the contact site for the sugar by allowing the side chain of N208 to ‘flop’ into its appropriate position [69-71]. At the heart of this process was trans- to cis-isomerization of a non-prolyl peptide bond at A207-N208 that promoted cation binding. In a survey of a non-redundant set of 571 proteins, 12 of the 43 hits for non-proline peptide bonds in cis-configuration (often located close to the active site) were sugar receptors or carbohydrate-processing enzymes [72]. Among them is the lentil lectin LCA with its β-sandwich fold just like concanavalin A [73], and the snowdrop lectin GNA with its β-prism II fold [74].

This phenomenon of shifting the position of a trans/cis-equilibrium in a peptide bond by a binding a divalent cation (or Tb3+) had also been discovered for the rat liver and serum collecting mannose-binding protein A/C (MGP-A/C), two Ca2+-dependent C-type lectins. In this case, however, proline (and its coordination with sugar) is involved. The cation-induced prolyl peptide bond isomerization at E190-P191 (P186 in MBP-A) allows these C-type lectins to preferentially adopt the active cis-form, whereas loss of the cation triggers a switch back to a ∼80–85% population of the trans-state which lacks the capacity to accommodate the cognate glycan [75,76]. In these two studies, the functionally intriguing opportunity to separate cargo from endocytic C-type lectins (which bear the highly conserved Pro residue at this strategic site) during endosomal transit upon exposure to an acidic pH that causes loss of Ca2+ (as suggested earlier [77], had not gone unnoticed. Keeping these precedents of Ca2+-triggered (non)-prolyl peptide bond isomerization in leguminous (seed) and mammalian (C-type) lectins in mind, we formulated the basic question as to whether a prolyl peptide bond isomerization can occur in a human Ca2+-independent lectin, thus establishing a putative molecular switch.

In our present study, we identified such a cation-independent process for a human galectin, namely position P4 of Gal-7. This discovery explained the occurrence of resonance pairs in NMR data of human Gal-7. Working with an engineered P4L mutant and acquiring NMR resonance assignments and inter-subunit NOEs, we found that the homo-dimeric lectin could exist as a mixed cis/trans-hetero-dimer. Lactose binding did not affect this equilibrium, with both conformations exhibiting rather equal affinities. If we assume functional relevance for this isomer generation, then this would imply an impact on activity other than glycan binding. Moreover, conformational changes occur at places away from the immediate vicinity of the lactose contact site that we defined in detail. For example, the N-terminus can move between a core-associated and a more solvent-exposed structure. Since shuttling between cellular compartments, as well as export, may involve this region as indicated with Gal-3 and its structural organization at this site [78,79], and N-terminal contact has been documented for Gal-1 around L11 in Ras-dependent growth regulation [80], tipping the balance toward one conformer or another here could be physiologically relevant, even providing a possible explanation for different intracellular routing of a galectin. Of note, the detected alterations go beyond the conformational repositioning at P4, as it affects the lectin more globally. As a consequence, this region of the protein (a platform for possible contacts with other proteins) can form two structures, each with its own complementarity profile.

In view of the capacity of Gal-7 to interact with key mediators of growth as mentioned in the introduction, mapping of the contact sites will thus be timely for counter-receptors in solution to trace respective pairing at this site. Conceptually, this has been done in this way for Gal-1 and the pre-B cell receptor. In this case, protein–protein interactions outside of the canonical lactose binding site, were depicted [81]. Also worth noting is that in the crystal structure of chicken galectin-1B (CG-1B), the proline residue at this analogous position in the trans-conformation (sandwiched by C2 and C7 that can form inter- and intra-subunit disulfide bridges) has been shown to stabilize the hydrophobic core at the interface [82], an indication for isomerization not yet studied. In addition to affecting interactions with protein counter-receptors and relative positions of members of the cysteine pair, this region around P4 at the interface could also regulate the extent of hetero-dimerization with subunits of other galectins, such as Gal-1 or -3, documented to occur recently [83]. When looking at galectin structures [84], crystallographic evidence for an isomerization at this site to the cis-state is available for the Charcot–Leyden crystal protein [85] (termed Gal-10) despite a lack to bind the canonical glycan ligand lactose as is the case for the galectin-related protein [6,86]. The conservation of proline within the N-terminal stretch (albeit to a limited extent) and the difference with the analogous pair CG-1A/B (CG-1A and also human Gal-1 having a leucine rather than proline at the equivalent position) hypothetically indicate a possible relevance, thus warranting investigation with functional studies.

Overall, our report on the prolyl peptide isomerization at P4 in human Gal-7 raises the perspective to systematically explore this so far unrecognized phenomenon for galectins. This molecular process may provide dynamic structural flexibility for Gal-7 to adapt to a high-affinity, and even cross-linking, state from the mixed-conformer form of the homodimer upon association with non-glycan counter-receptors, and the observed difference in growth inhibition of neuroblastoma cells as a sign for a more active surface lattice at higher concentrations. Structural conversion then may bring about a similar outcome, as the presence of an N-glycan does, for a galectin, if directed to enter the endoplasmic reticulum [17]. Since galectins are at least bifunctional, they can engage in binding more than one partner. Cooperation between sites for glycan binding and for non-glycan contacts on the cell surface has been documented to occur with Ctx-B [87,88], providing us with an inspiring model, and, indeed, recently for Gal-3 when interacting with a glycan and the chemokine CXCL12 [89].

In this sense, our present data provide a clear direction for further research. Thus comparative assays with wild-type Gal-7 and its P4L mutant appear warranted, as generation of a change to the P4L status on the genome level is a new type of variant design for delineating structure-activity relationships [90,91]. In this context, we should note the occurrence of two Gal-7 genes in man and primates [92]. Equally relevant is the P-to-H substitution in mouse and rat Gal-7, a factor to note when extrapolating data across species barriers, that can prompt studies with variants bearing a proline at this site (with a mutant or with cells engineered to express the mutant lectin, in comparison with wild-type controls) and complement work with mutant(s) of human Gal-7. With these tools in hand, the next steps toward defining the biological relevance for this isomerization process (if any) can confidently be undertaken.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to Lieselotte Mantel for her excellent technical assistance. NMR Instrumentation was provided with funds from the NSF (BIR-961477), the University of Minnesota Medical School and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. The authors also wish to thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (University of Minnesota) for providing computer resources. K.H.M. is also most grateful for financial support from the Ludwig-Maximillians-Universitaet Center for Advanced Study, and the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung, during his 2019 sabbatical stay in Munich, Germany.

Abbreviations

- CG

chicken galectin

- CRD

carbohydrate recognition domain

- Ctx-B

cholera toxin B-subunit

- Gal-7

galectin-7

- HDX

hydrogen-deuterium exchange

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NOESY

nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- PFG

pulse field gradient

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

The author declares that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

Open access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of University of Minnesota in an all-inclusive Read & Publish pilot with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society.

Authors Contribution

M.C.M., I.V.N., V.A.D. and H.I. performed the NMR experiments, and helped write the manuscript. M.C.M., I.V.N. and A.D. calculated the NMR-based structures and performed molecular dynamics studies. M.M. and J.K. performed the MS studies and helped write the manuscript. H.K. and H.J.G. expressed, isolated and purified the galectin proteins used in the study and helped write the manuscript. K.H.M. supervised the NMR work, analyzed and interpreted NMR data, and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Madsen P., Rasmussen H.H., Flint T., Gromov P., Kruse T.A., Honoré B. et al. (1995) Cloning, expression and chromosome mapping of human galectin-7. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5823–5829 10.1074/jbc.270.11.5823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J., Pei H., Kaeck M. and Thompson H.J. (1997) Gene expression changes associated with chemically induced rat mammary carcinogenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 20, 204–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyak K., Xia Y., Zweier J.L., Kinzler K.M. and Vogelstein B. (1997) A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature 389, 300–305 10.1038/38525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teichberg V.I., Silman I., Beitsch D.D. and Resheff G. (1975) A β-D-galactoside-binding protein from electric organ tissue of Electrophorus electricus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 1383–1387 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirabayashi J. (1997) Recent topics on galectins. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 9, 1–180 10.4052/tigg.9.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper D.N.W. (2002) Galectinomics: finding themes in complexity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1572, 209–231 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00310-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltner H., Toegel S., García Caballero G., Manning J.C., Ledeen R.W. and Gabius H.-J. (2017) Galectins: their network and roles in immunity/tumor growth control. Histochem. Cell Biol. 147, 239–256 10.1007/s00418-016-1522-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirabayashi J. (2018) Special issue on galectins. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 30, SE1–SE223 10.4052/tigg.1736.1SJ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabius H.-J. and Roth J. (2017) An introduction to the sugar code. Histochem. Cell Biol. 147, 111–117 10.1007/s00418-016-1521-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaltner H., Abad-Rodríguez J., Corfield A.P., Kopitz J. and Gabius H.-J. (2019) The sugar code: letters and vocabulary, writers, editors and readers and biosignificance of functional glycan-lectin pairing. Biochem. J. 476, 2623–2655 10.1042/BCJ20170853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F.-T., Patterson R.J. and Wang J.L. (2002) Intracellular functions of galectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1572, 263–273 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00313-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García Caballero G., Schmidt S., Schnölzer M., Schlötzer-Schrehardt U., Knospe C., Ludwig A.-K. et al. (2019) Chicken GRIFIN: binding partners, developmental course of localization and activation of its lens-specific gene expression by L-Maf/Pax6. Cell Tissue Res. 375, 665–683 10.1007/s00441-018-2931-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes R.C. (1999) Secretion of the galectin family of mammalian carbohydrate-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473, 172–185 10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haudek K.C., Spronk K.J., Voss P.G., Patterson R.J., Wang J.L. and Arnoys E.J. (2010) Dynamics of galectin-3 in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1800, 181–189 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funasaka T., Raz A. and Nangia-Makker P. (2014) Nuclear transport of galectin-3 and its therapeutic implications. Semin. Cancer Biol. 27, 30–38 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato S. (2018) Cytosolic galectins and their release and roles as carbohydrate-binding proteins in host-pathogen interaction. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 30, SE199–SE209 10.4052/tigg.1739.1SE [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutzner T.J., Higuero A.M., Sussmair M., Kopitz J., Hingar M., Diez-Revuelta N. et al. (2019) How presence of a signal peptide affects human galectins-1 and -4: Clues to explain common absence of a leader sequence among adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1864, 129449 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.129449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuwabara I., Kuwabara Y., Yang R.Y., Schuler M., Green D.R., Zuraw B.L. et al. (2002) Galectin-7 (PIG1) exhibits pro-apoptotic function through JNK activation and mitochondrial cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3487–3497 10.1074/jbc.M109360200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saussez S., Decaestecker C., Lorfevre F., Chevalier D., Mortuaire G., Kaltner H. et al. (2008) Increased expression and altered intracellular distribution of adhesion/growth-regulatory lectins galectins-1 and -7 during tumour progression in hypopharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Histopathology 52, 483–493 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.02973.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cada Z., Chovanec M., Smetana K., Betka J., Lacina L., Plzak J. et al. (2009) Galectin-7: will the lectin's activity establish clinical correlations in head and neck squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas? Histol. Histopathol. 24, 41–48 10.14670/HH-24.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernerd F., Sarasin A. and Magnaldo T. (1999) Galectin-7 overexpression is associated with the apoptotic process in UVB-induced sunburn keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11329–11334 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda S., Kuwabara I. and Liu F.-T. (2004) Suppression of tumor growth by galectin-7 gene transfer. Cancer Res. 64, 5672–5676 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopitz J., André S., von Reitzenstein C., Versluis K., Kaltner H., Pieters R.J. et al. (2003) Homodimeric galectin-7 (p53-induced gene 1) is a negative growth regulator for human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene 22, 6277–6288 10.1038/sj.onc.1206631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturm A., Lensch M., André S., Kaltner H., Wiedenmann B., Rosewicz S. et al. (2004) Human galectin-2: novel inducer of T cell apoptosis with distinct profile of caspase activation. J. Immunol. 173, 3825–3837 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demers M., Magnaldo T. and St-Pierre Y. (2005) A novel function for galectin-7: promoting tumorigenesis by up-regulating MMP-9 gene expression. Cancer Res. 65, 5205–5210 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campion C.G., Labrie M., Lavoie G. and St-Pierre Y. (2013) Expression of galectin-7 is induced in breast cancer cells by mutant p53. PLoS One 8, e72468 10.1371/journal.pone.0072468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inagaki Y., Higashi K., Kushida M., Hong Y.Y., Nakao S., Higashiyama R. et al. (2008) Hepatocyte growth factor suppresses profibrogenic signal transduction via nuclear export of Smad3 with galectin-7. Gastroenterology 134, 1180–1190 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosset A.A., Labrie M., Gagne D., Vladoiu M.C., Gaboury L., Doucet N. et al. (2014) Cytosolic galectin-7 impairs p53 functions and induces chemoresistance in breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 14, 801 10.1186/1471-2407-14-801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villeneuve C., Baricault L., Canelle L., Barboule N., Racca C., Monsarrat B. et al. (2011) Mitochondrial proteomic approach reveals galectin-7 as a novel bcl-2 binding protein in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 999–1013 10.1091/mbc.e10-06-0534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Advedissian T., Proux-Gillardeaux V., Nkosi R., Peyret G., Nguyen T., Poirier F. et al. (2017) E-Cadherin dynamics is regulated by galectin-7 at epithelial cell surface. Sci. Rep. 7, 17086 10.1038/s41598-017-17332-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H.L., Chiang P.C., Lo C.H., Lo Y.H., Hsu D.K., Chen H.Y. et al. (2016) Galectin-7 regulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation through JNK-miR-203-p63 signaling. J. Invest. Dermatol. 136, 182–191 10.1038/JID.2015.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nesmelova I.V., Berbis M.A., Miller M.C., Cañada F.J., André S., Jiménez-Barbero J. et al. (2012) 1H, 13c, and 15N backbone and side-chain chemical shift assignments for the 31kDa human galectin-7 (p53-induced gene 1) homodimer, a pro-apoptotic lectin. Biomol. NMR Assign. 6, 127–129 10.1007/s12104-011-9339-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ermakova E., Miller M.C., Nesmelova I.V., Lopez-Merino L., Berbís M.A., Nesmelov Y. et al. (2013) Lactose binding to human galectin-7 (p53-induced gene 1) induces long-range effects through the protein resulting in increased dimer stability and evidence for positive cooperativity. Glycobiology 23, 508–523 10.1093/glycob/cwt005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nesmelova I.V., Pang M., Baum L.G. and Mayo K.H. (2008) 1H, 13c, and 15N backbone and side-chain chemical shift assignments for the 29 kDa human galectin-1 protein dimer. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2, 203–205 10.1007/s12104-008-9121-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J. and Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 10.1007/BF00197809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson B.A. (2004) Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 278, 313–352 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou J.J., Delaglio F. and Bax A. (2000) Measurement of one-bond 15N-13C’ dipolar couplings in medium sized proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 18, 101–105 10.1023/A:1008358318863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nesmelova I.V., Idiyatullin D. and Mayo K.H. (2004) Measuring protein self-diffusion in protein-protein mixtures using a pulsed gradient spin-echo technique with WATERGATE and isotope filtering. J. Magn. Reson. 166, 129–133 10.1016/j.jmr.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nesmelova I.V., Sham Y., Dudek A.Z., van Eijk L.I., Wu G., Slungaard A. et al. (2005) Platelet factor 4 and interleukin-8 CXC chemokine heterodimer formation modulates function at the quaternary structural level. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4948–4958 10.1074/jbc.M405364200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daragan V.A., Kloczewiak M.A. and Mayo K.H. (1993) 13C nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation-derived (, ( bond rotational energy barriers and rotational restrictions for glycine 13C (-methylenes in a GXX-repeat hexadecapeptide. Biochemistry 32, 10580–10590 10.1021/bi00091a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Idiyatullin D., Krushelnitsky A., Nesmelova I., Blanco F., Daragan V.A., Serrano L. et al. (2000) Internal motional amplitudes and correlated bond rotations in an α-helical peptide derived from13C and 15N NMR relaxation. Protein Sci. 9, 2118–2127 10.1110/ps.9.11.2118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Idiyatullin D., Nesmelova I., Daragan V.A. and Mayo K.H. (2003) Comparison of 13CαH and 15NH backbone dynamics in protein GB1. Protein Sci. 12, 914–922 10.1110/ps.0228703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipari G. and Szabo A. (1981) Nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in nucleic acid fragments: models for internal motion. Biochemistry 20, 6250–6256 10.1021/bi00524a053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopitz J., Vértesy S., André S., Fiedler S., Schnölzer M. and Gabius H.-J. (2014) Human chimera-type galectin-3: defining the critical tail length for high-affinity glycoprotein/cell surface binding and functional competition with galectin-1 in neuroblastoma cell growth regulation. Biochimie 104, 90–99 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García Caballero G., Flores-Ibarra A., Michalak M., Khasbiullina N., Bovin N.V., André S. et al. (2016) Galectin-related protein: an integral member of the network of chicken galectins. 1. From strong sequence conservation of the gene confined to vertebrates to biochemical characteristics of the chicken protein and its crystal structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 2285–2297 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopitz J., von Reitzenstein C., Burchert M., Cantz M. and Gabius H.-J. (1998) Galectin-1 is a major receptor for ganglioside GM1, a product of the growth-controlling activity of a cell surface ganglioside sialidase, on human neuroblastoma cells in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 11205–11211 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kopitz J., von Reitzenstein C., André S., Kaltner H., Uhl J., Ehemann V. et al. (2001) Negative regulation of neuroblastoma cell growth by carbohydrate-dependent surface binding of galectin-1 and functional divergence from galectin-3. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35917–35923 10.1074/jbc.M105135200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kopitz J., Ballikaya S., André S. and Gabius H.-J. (2012) Ganglioside GM1/galectin-dependent growth regulation in human neuroblastoma cells: special properties of bivalent galectin-4 and significance of linker length for ligand selection. Neurochem. Res. 37, 1267–1276 10.1007/s11064-011-0693-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Tjandra N. and Clore G.M. (2003) The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 10.1016/S1090-7807(02)00014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dominguez C., Boelens R. and Bonvin A.M. (2003) HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 10.1021/ja026939x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E. et al. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leonidas D.D., Vatzaki E.H., Vorum H., Celis J.E., Madsen P. and Acharya K.R. (1998) Structural basis for the recognition of carbohydrates by human galectin-7. Biochemistry 37, 13930–13940 10.1021/bi981056x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schubert M., Labudde D., Oschkinat H. and Schmieder P. (2002) A software tool for the prediction of Xaa-Pro peptide bond conformations in proteins based on 13C chemical shift statistics. J. Biomol. NMR 24, 149–154 10.1023/A:1020997118364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cavalli A., Salvatella X., Dobson C.M. and Vendruscolo M. (2007) Protein structure determination from NMR chemical shifts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9615–9620 10.1073/pnas.0610313104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen Y., Lange O., Delaglio F., Rossi P., Aramini J.M., Liu G. et al. (2008) Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4685–4690 10.1073/pnas.0800256105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen Y., Vernon R., Baker D. and Bax A. (2009) De novo protein structure generation from incomplete chemical shift assignments. J. Biomol. NMR 43, 63–78 10.1007/s10858-008-9288-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wishart D.S., Arndt D., Berjanskii M., Tang P., Zhou J. and Lin G. (2008) CS23D: a web server for rapid protein structure generation using NMR chemical shifts and sequence data. Nucl. Acids Res. 36, W496–W502 10.1093/nar/gkn305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wüthrich K. (1986) NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids, John Wiley & Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morris S., Ahmad N., André S., Kaltner H., Gabius H.-J., Brenowitz M. et al. (2004) Quaternary solution structures of galectins-1, -3 and -7. Glycobiology 14, 293–300 10.1093/glycob/cwh029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schurr J.M., Babcock H.P. and Fujimoto B.S. (1994) A test of the model-free formulas. Effects of anisotropic rotational diffusion and dimerization. J. Magn. Reson. 105, 211–224 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prabhu N.V., Lee A.L., Wand A.J. and Sharp K.A. (2003) Dynamics and entropy of a calmodulin-peptide complex studied by NMR and molecular dynamics. Biochemistry 42, 562–570 10.1021/bi026544q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nesmelova I.V., Ermakova E., Daragan V.A., Pang M., Menendez M., Lagartera L. et al. (2010) Lactose binding to galectin-1 modulates structural dynamics, increases conformational entropy, and occurs with apparent negative cooperativity. J. Mol. Biol. 397, 1209–1230 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmad N., Gabius H.-J., Kaltner H., André S., Kuwabara I., Liu F.-T. et al. (2002) Thermodynamic binding studies of cell surface carbohydrate epitopes to galectins-1, -3 and -7. Evidence for differential binding specificities. Can. J. Chem. 80, 1096–1104 10.1139/v02-162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dam T.K., Gabius H.-J., André S., Kaltner H., Lensch M. and Brewer C.F. (2005) Galectins bind to the multivalent glycoprotein asialofetuin with enhanced affinities and a gradient of decreasing binding constants. Biochemistry 44, 12564–12571 10.1021/bi051144z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cantor C. R. and Schimmel P. R (1980) Biophysical Chemistry. pp. 1–3, Freeman, W. H., New York [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown R.D. III, Brewer C.F. and Koenig S.H. (1977) Conformation states of concanavalin A: kinetics of transitions induced by interaction with Mn2+ and Ca2+ ions. Biochemistry 16, 3883–3896 10.1021/bi00636a026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koenig S.H., Brewer C.F. and Brown R.D. III (1978) Conformation as the determinant of saccharide binding in concanavalin A: Ca2+-concanavalin A complexes. Biochemistry 17, 4251–4260 10.1021/bi00613a022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gabius H.-J. (2011) The how and why of Ca2+ involvement in lectin activity. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 23, 168–177 10.4052/tigg.23.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bouckaert J., Loris R., Poortmans F. and Wyns L. (1995) Crystallographic structure of metal-free concanavalin A at 2.5 Å resolution. Proteins 23, 510–524 10.1002/prot.340230406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouckaert J., Poortmans F., Wyns L. and Loris R. (1996) Sequential structural changes upon zinc and calcium binding to metal-free concanavalin A. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16144–16150 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bouckaert J., Dewallef Y., Poortmans F., Wyns L. and Loris R. (2000) The structural features of concanavalin A governing non-proline peptide isomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19778–19787 10.1074/jbc.M001251200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jabs A., Weiss M.S. and Hilgenfeld R. (1999) Non-proline cis peptide bonds in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 286, 291–304 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loris R., Van Overberge D., Dao-Thi M.H., Poortmans F., Maene N. and Wyns L. (1994) Structural analysis of two crystal forms of lentil lectin at 1.8 A resolution. Proteins 20, 330–346 10.1002/prot.340200406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hester G., Kaku H., Goldstein I.J. and Wright C.S. (1995) Structure of mannose-specific snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) lectin is representative of a new plant lectin family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 472–479 10.1038/nsb0695-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ng K.K., Park-Snyder S. and Weis W.I. (1998) Ca2+-dependent structural changes in C-type mannose-binding proteins. Biochemistry 37, 17965–17976 10.1021/bi981972a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ng K.K.-S. and Weis W.I. (1998) Coupling of prolyl peptide bond isomerization and Ca2+ binding in a C-type mannose-binding protein. Biochemistry 37, 17977–17989 10.1021/bi9819733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leitinger B., Hille-Rehfeld A. and Spiess M. (1995) Biosynthetic transport of the asialoglycoprotein receptor H1 to the cell surface occurs via endosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 10109–10113 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gong H.C., Honjo Y., Nangia-Makker P., Hogan V., Mazurak N., Bresalier R.S. et al. (1999) The NH2 terminus of galectin-3 governs cellular compartmentalization and functions in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 59, 6239–6245 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Flores-Ibarra A., Vértesy S., Medrano F.J., Gabius H.-J. and Romero A. (2018) Crystallization of a human galectin-3 variant with two ordered segments in the shortened N-terminal tail. Sci. Rep. 8, 9835 10.1038/s41598-018-28235-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rotblat B., Niv H., André S., Kaltner H., Gabius H.-J. and Kloog Y. (2004) Galectin-1(L11A) predicted from a computed galectin-1 farnesyl-binding pocket selectively inhibits Ras-GTP. Cancer Res. 64, 3112–3118 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elantak L., Espeli M., Boned A., Bornet O., Bonzi J., Gauthier L. et al. (2012) Structural basis for galectin-1-dependent pre-B cell receptor (pre-BCR) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 44703–44713 10.1074/jbc.M112.395152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.López-Lucendo M.F., Solís D., Sáiz J.L., Kaltner H., Russwurm R., André S. et al. (2009) Homodimeric chicken galectin CG-1B (C-14): crystal structure and detection of unique redox-dependent shape changes involving inter- and intrasubunit disulfide bridges by gel filtration, ultracentrifugation, site-directed mutagenesis, and peptide mass fingerprinting. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 366–378 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miller M.C., Ludwig A.-K., Wichapong K., Kaltner H., Kopitz J., Gabius H.-J. et al. (2018) Adhesion/growth-regulatory galectins tested in combination: evidence for formation of hybrids as heterodimers. Biochem. J. 475, 1003–1018 10.1042/BCJ20170658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kamitori S. (2018) Three-dimensional structures of galectins. Trends. Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 30, SE41–SE50 10.4052/tigg.1731.1SE [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leonidas D.D., Elbert D.L., Zhou Z., Leffler H., Ackerman S.J. and Acharya K.R. (1995) Crystal structure of human Charcot-Leyden crystal protein, an eosinophil lysophospholipase, identifies it as a new member of the carbohydrate-binding family of galectins. Structure 3, 1379–1393 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00275-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Manning J.C., García Caballero G., Ruiz F.M., Romero A., Kaltner H. and Gabius H.-J. (2018) Members of the galectin network with deviations from the canonical sequence signature. 2. Galectin-related protein (GRP). Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 30, SE11–SE20 10.4052/tigg.1727.1SE [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aman A.T., Fraser S., Merritt E.A., Rodigherio C., Kenny M., Ahn M. et al. (2001) A mutant cholera toxin B subunit that binds GM1- ganglioside but lacks immunomodulatory or toxic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8536–8541 10.1073/pnas.161273098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodighiero C., Fujinaga Y., Hirst T.R. and Lencer W.I. (2001) A cholera toxin B-subunit variant that binds ganglioside GM1 but fails to induce toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36939–36945 10.1074/jbc.M104245200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eckardt V., Miller M.C., Blanchet X., Duan R., Leberzammer J., Duchene J. et al. (2020) Chemokines and galectins form heterodimers to modulate inflammation. EMBO Rep. 21, e47852 10.15252/embr.201947852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaltner H., García Caballero G., Ludwig A.-K., Manning J.C. and Gabius H.-J. (2018) From glycophenotyping by (plant) lectin histochemistry to defining functionality of glycans by pairing with endogenous lectins. Histochem. Cell Biol. 149, 547–568 10.1007/s00418-018-1676-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ludwig A.-K., Kaltner H., Kopitz J. and Gabius H.-J. (2019) Lectinology 4.0: altering modular (ga)lectin display for functional analysis and biomedical applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 935–940 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaltner H., Raschta A.-S., Manning J.C. and Gabius H.-J. (2013) Copy-number variation of functional galectin genes: studying animal galectin-7 (p53-induced gene 1 in man) and tandem-repeat-type galectins-4 and -9. Glycobiology 23, 1152–1163 10.1093/glycob/cwt052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.