Abstract

Background

Besides improving glucose control, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition with dapagliflozin reduces blood pressure, body weight and urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR) in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The parameter response efficacy (PRE) score was developed to predict how short-term drug effects on cardiovascular risk markers translate into long-term changes in clinical outcomes. We applied the PRE score to clinical trials of dapagliflozin to model the effect of the drug on kidney and heart failure (HF) outcomes in patients with T2DM and impaired kidney function.

Methods

The relationships between multiple risk markers and long-term outcome were determined in a background population of patients with T2DM with a multivariable Cox model. These relationships were then applied to short-term changes in risk markers observed in a pooled database of dapagliflozin trials (n = 7) that recruited patients with albuminuria to predict the drug-induced changes to kidney and HF outcomes.

Results

A total of 132 and 350 patients had UACR >200 mg/g and >30 mg/g at baseline, respectively, and were selected for analysis. The PRE score predicted a risk change for kidney events of −40.8% [95% confidence interval (CI) −51.7 to −29.4) and −40.4% (95% CI −48.4 to −31.1) with dapagliflozin 10 mg compared with placebo for the UACR >200 mg/g and >30 mg/g subgroups. The predicted change in risk for HF events was −27.3% (95% CI −47.7 to −5.1) and −21.2% (95% CI −35.0 to −7.8), respectively. Simulation analyses showed that even with a smaller albuminuria-lowering effect of dapagliflozin (10% instead of the observed 35% in both groups), the estimated kidney risk reduction was still 26.5 and 26.8%, respectively.

Conclusions

The PRE score predicted clinically meaningful reductions in kidney and HF events associated with dapagliflozin therapy in patients with diabetic kidney disease. These results support a large long-term outcome trial in this population to confirm the benefits of the drug on these endpoints.

Keywords: clinical trial, dapagliflozin, diabetic kidney disease, heart failure, risk markers

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 40% of patients with diabetes develop chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. Both diabetes and CKD are powerful risk factors for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and cardiovascular disease. In addition, emerging data demonstrate a strong association between diabetes and heart failure (HF). Patients with both diabetes and impaired kidney function are at particular high risk to develop HF [2, 3]. As a result, life expectancy among patients with diabetes and kidney disease and/or HF is shortened [4]. New therapies to decrease the risks of developing CKD and HF are being developed.

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a relatively new class of oral anti-diabetic drugs registered for use in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Recent cardiovascular outcome trials have demonstrated that the SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin reduce the risk of HF and slow kidney disease progression in patients with T2DM at cardiovascular risk or with established cardiovascular disease [5–7]. The marked efficacy of these drugs to delay disease progression is unlikely to be explained by their effects on glycated haemoglobin [haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)] alone. Indeed, a study comparing glimepiride against canagliflozin concluded that the beneficial effects of canagliflozin in slowing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline were independent of its glycaemic effects [8]. Furthermore, in hypertensive patients with T2DM who were using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, HbA1c lowering by dapagliflozin only modestly explained the overall 35% reduction in the urine albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR) [9]. The multiple effects of SGLT2 inhibition, including reductions in body weight, blood pressure (BP), albuminuria and uric acid, in addition to reducing HbA1c, may contribute to the reduction in HF and kidney events observed in prior studies [9–11].

Because SGLT2 inhibition has effects on multiple cardiovascular risk markers, integrating changes in these multiple effects as opposed to using HbA1c alone to predict the long-term effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on kidney and HF outcomes seems sensible. The multiple parameter response efficacy (PRE) score is an algorithm that has been developed to translate the effect of an intervention on multiple risk markers into a predicted long-term risk change on clinical outcomes [10]. The PRE score was developed in clinical trials of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) intervention and subsequently validated in clinical trials of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system intervention, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists and endothelin receptor antagonists [12–14].

Randomized controlled trials investigating the long-term effects of SGLT2 inhibition in patients with CKD are currently ongoing. The aim of this study was to apply the PRE score to Phase 3 clinical trials with the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in order to predict the potential benefit of dapagliflozin on kidney and HF outcomes in patients with T2DM and CKD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources and patient population

Individual patient data were selected from a pooled database of Phase 3 dapagliflozin clinical trials (n = 7) with an eGFR between 25 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR >30 mg/g (Supplementary data, Table S1). The study designs of these trials have been previously published [15–21]. Patients were then stratified into two groups, those with UACR >30 mg/g (n = 350) and those with UACR >200 mg/g (n = 132), in order to test the PRE score at varying levels of albuminuria. Patients with impaired eGFR and elevated albuminuria were selected, as this population is also enrolled in the ongoing kidney outcome trials.

Individual patient data from the placebo arm of the Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints (ALTITUDE) were used for the background population to model the risk relations for different cardiovascular risk markers with kidney and HF outcomes. The design of ALTITUDE has been previously published [22]. This population included patients with T2DM and CKD (defined as eGFR between 25 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) with various degrees of albuminuria [UACR >30 mg/g (n = 2163) and UACR >200 mg/g (n = 1341)].

Endpoint definition

The kidney outcome was defined as a composite of ESKD and a confirmed doubling of serum creatinine. The HF outcome was defined as hospitalization due to congestive heart failure (CHF).

Risk marker selection

Parameters measured in the intention-to-treat population of the dapagliflozin Phase 3 trials that were previously identified as risk markers for kidney or HF outcomes and have been shown to change with SGLT2 treatment were used for analysis. These included Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), systolic BP, UACR, body weight, haemoglobin (Hb), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), serum albumin, calcium, potassium, phosphate and uric acid. The UACR was measured in an untimed random spot urine sample.

Statistical analysis

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the coefficients and hazard ratios associated with each risk marker for the first recorded kidney or HF event. The regression coefficients for each risk marker were taken and used as weights for the risk equation for kidney and HF outcomes. First, risk marker–outcome relationships were calculated in ALTITUDE over a median follow-up of 2.8 years. These calculated risk marker–outcome relationships were then applied to the baseline and Week 24 (Month 6) biomarker measurements of patients selected from the dapagliflozin trials to estimate the risk of kidney and HF outcomes at both time points. The mean difference in the predicted risk in the dapagliflozin arm, adjusted for the mean difference in the predicted risk in the placebo arm, represents the PRE score and reflects an estimation of the expected kidney and HF risk reduction conferred by dapagliflozin treatment.

Risk marker–outcome relationships were calculated in patients from the ALTITUDE background population with UACR >200 mg/g (n = 1341) and UACR >30 mg/g (n = 2641). These relationships were applied to patients included in the dapagliflozin Phase 3 trials with UACR >200 mg/g (n = 92) and UACR >30 mg/g (n = 260), respectively. The PRE score was calculated for subjects in the dapagliflozin Phase 3 trials in which all risk markers were measured at baseline and follow-up. To evaluate the influence of missing data, we applied multiple imputations to the data from the dapagliflozin Phase 3 programme by using a multilevel linear model (from the R package ‘mice’; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, www.r-project.org). Since the short-term change in albuminuria is a strong predictor of kidney outcomes, we performed a simulation analysis to estimate the change in the risk of kidney outcomes at various levels of albuminuria reduction.

Means and standard deviations (SDs) are provided for variables with a normal distribution, whereas medians and first and third quartiles are provided for variables with a skewed distribution. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables that are not normally distributed, such as UACR, a natural log transformation was applied before analysis. Two-sided P-values <0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 3.0.1.

RESULTS

In the background dataset derived from ALTITUDE, 172 (8.0%) patients experienced a kidney event and 120 (5.5%) patients were hospitalized for CHF during a median follow-up of 2.8 years.

Baseline characteristics of the populations from ALTITUDE and the dapagliflozin trials with UACR >200 mg/g and >30 mg/g are described in Table 1 and Supplementary data, Table S2, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the background population from ALTITUDE and the dapagliflozin Phase 3 programme participants included in the analysis for the subgroup with UACR >200 mg/g

| Background population (n = 1341) | Placebo (n = 31) | DAPA 5 mg (n = 33) | DAPA 10 mg (n = 28) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 63.0 (9.6) | 64.4 (7.7) | 63.5 (7.5) | 62.0 (9.5) | 0.35 |

| Female, n (%) | 411 (31) | 9 (29) | 13 (38) | 6 (21) | 1.00 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Caucasian | 641 (48) | 27 (87) | 26 (77) | 24 (86) | |

| Black | 47 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | |

| Asian | 530 (39) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) | 1 (4) | |

| Other | 123 (9) | 2 (7) | 4 (12) | 1 (4) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| HbA1c (%) | 7.8 (1.6) | 8.4 (0.9) | 8.5 (1.0) | 8.2 (0.9) | 0.94 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 139 (17) | 141 (15) | 143.2 (19.4) | 143.7 (19.6) | 0.47 |

| UACR (mg/g), median (IQR) | 869 (385–1795) | 618 (353–980) | 696 (449–1835) | 576 (388–1028) | 0.23 |

| Weight (kg) | 81.0 (19) | 98.4 (20) | 90.2 (15.0) | 99.2 (19.3) | 0.31 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.7 (1.8) | 13.4 (1.8) | 13.2 (1.3) | 13.4 (1.6) | 0.76 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 45.9 (13.7) | 41.7 (9.5) | 39.4 (11.5) | 41.8 (8.6) | 0.59 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 102.6 (39) | 87.9 (32) | 106.9 (43.8) | 95.1 (36.5) | 0.11 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.3) | 0.07 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | 0.41 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.4) | 0.47 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 7.2 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.9) | 0.08 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.3 (0.5) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.4 (0.5) | 9.6 (0.5) | 0.17 |

Values are presented as mean (SD) unless stated otherwise.

P-value for the difference between placebo and dapagliflozin.

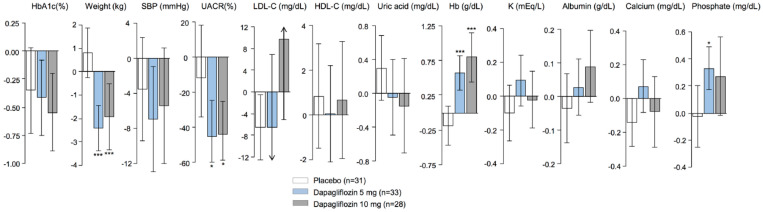

Short-term changes in risk markers

Changes in risk markers in patients with UACR >200 mg/g after treatment with placebo and dapagliflozin 5 and 10 mg are shown in Figure 1. In line with prior studies in patients with impaired kidney function, dapagliflozin modestly reduced HbA1c. Reductions in body weight, BP, uric acid and UACR and increases in Hb, albumin and phosphate were also observed. The direction and magnitude of the short-term changes in risk markers were similar in patients with UACR > 30mg/g (Supplementary data, Figure S1).

FIGURE 1.

Mean changes in risk markers from baseline to Month 6 in the included population of the dapagliflozin Phase 3 programme with UACR >200 mg/g. Changes are presented as mean (±95% CI) and are given for placebo, dapagliflozin 5 mg and dapagliflozin 10 mg.

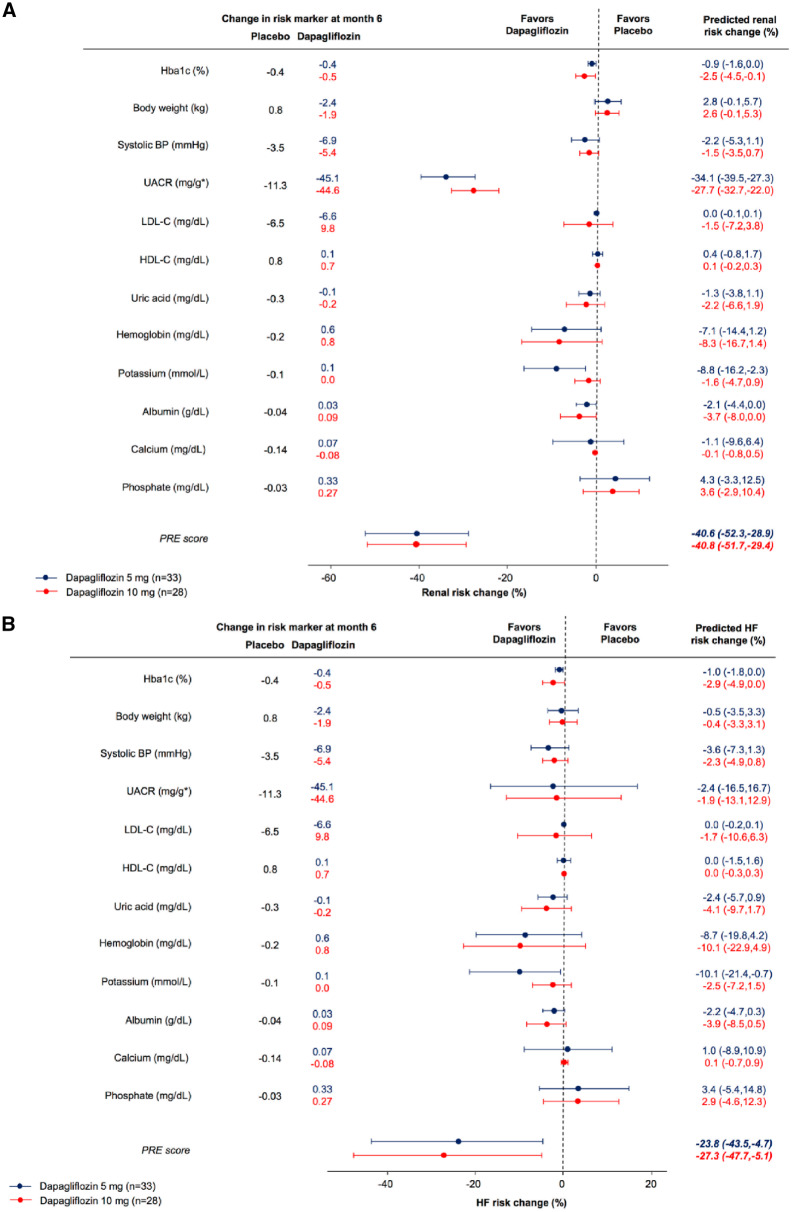

Predicted treatment effect

In patients with UACR >200 mg/g, the predicted risk change for the kidney endpoint with dapagliflozin based on the observed placebo-corrected change in HbA1c alone was −0.9% (−1.6–0.0) and −2.5% (95% CI −4.5 to –0.1) with dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg, respectively (Figure 2). Based on albuminuria-lowering effects alone, the predicted risk change in kidney endpoints was −34.1% (95% CI −39.5 to −27.3) and −27.7% (95% CI −32.7 to −22.0), respectively. Integrating all short-term biomarker changes resulted in a predicted risk change of −40.6% (95% CI −52.3 to −28.9) and −40.8% (95% CI −51.7 to −29.4) with dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg, respectively. The predicted risk change for hospitalization due to HF based on the PRE score was −23.8% (95% CI −43.4 to −4.7) and −27.3% (95% CI −47.7 to −5.1), respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted risk change for (A) kidney and (B) HF outcomes for patients with UACR >200 mg/g, based on changes in single risk markers and the integrated effects of all risk markers. Circles indicate the point estimates of the percentage mean change in relative risk induced by dapagliflozin compared with placebo and is given with its 95% CI.

In patients with UACR >30 mg/g, the predicted risk change for the kidney endpoint was −47.6% (95% CI −55.9 to −37.1) and −40.4% (95% CI −48.1 to −31.1) after treatment with dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg, respectively. The predicted risk change for hospitalizations due to HF was −23.4% (95% CI −39.1 to −7.4) and −21.2% (95% CI −35.0 to −7.8), respectively (Supplementary data, Figure S1).

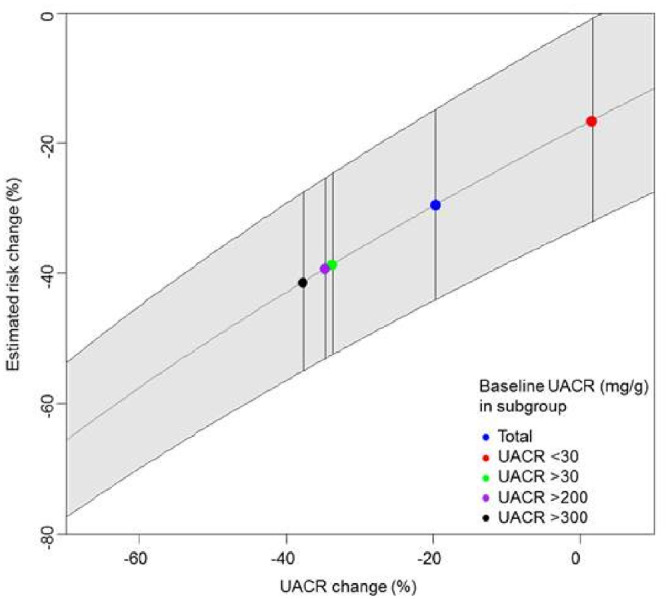

Simulations and sensitivity analyses

Since albuminuria change is a strong predictor for kidney outcomes, additional simulations were performed in order to predict the risk changes for varying levels of albuminuria changes induced by dapagliflozin (Figure 3). These simulation analyses revealed that a 10% decrease in UACR, instead of the observed decrease of 35%, would have resulted in an estimated kidney risk reduction of 26.8 and 26.5% in patients with UACR >200 mg/g and >30 mg/g, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Simulated UACR changes and the effect on kidney outcomes.

In a sensitivity analysis, we assessed the impact of missing values. In the dapagliflozin trials, data were missing in 9.5% of patients at baseline and in 25.1% of patients at Month 6. There were very few missing baseline data across the ALTITUDE background dataset (<0.01%). There were no differences in baseline characteristics between patients with complete biomarker data and the total selected population from the dapagliflozin trials (n = 350). Short-term changes in risk markers in the analysis population remained similar after multiple imputations. In patients with UACR >200 mg/g, the predicted kidney risk changes with dapagliflozin 5 and 10 mg after multiple imputation were −44.1% (95% CI −5.1 to −32.6) and −38.5% (95% CI −47.2 to −28.7), respectively. The predicted risk changes for hospitalizations due to HF were −24.0% (95% CI −46.0 to −3.1) and −24.7% (95% CI −43.6 to −5.0), respectively (Supplementary data, Figure S2). After multiple imputations, predicted risk changes for kidney and HF outcomes for patients with UACR >30 mg/g did not differ from those in the main analysis without multiple imputations (Supplementary data, Figure S3).

DISCUSSION

Changes in biomarkers can be used to monitor and predict the efficacy of therapies to decrease the risk of kidney and cardiovascular outcomes. In this study we used an algorithm that translates the short-term effect of an intervention on multiple risk markers into a predicted long-term risk change on clinical outcomes. The algorithm was used to predict the effect of dapagliflozin on kidney and HF outcomes in patients with T2DM and CKD. Our results indicate that treatment with dapagliflozin would confer considerable improvements in kidney and HF outcomes in these patients. These results support a large dapagliflozin outcome trial to confirm long-term safety and efficacy in reducing adverse clinical events.

As with most short-term clinical trials testing the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, the dapagliflozin trials included in this study were primarily designed to assess the effects of dapagliflozin on HbA1c [15–17, 19–21, 23]. Our analysis suggests that glycaemic effects of dapagliflozin only modestly contribute in reducing the risk of kidney outcomes. Non-glycaemic effects of dapagliflozin, in particular the albuminuria-lowering properties, are probably more important contributors of the predicted effects on kidney outcomes. Indeed, prior studies have suggested that albuminuria lowering is a key to reducing kidney outcomes [24, 25].

A meta-analysis of cardiovascular events across the dapagliflozin Phases 2b and 3 programmes suggested beneficial effects of dapagliflozin on cardiovascular and HF outcomes [26]. In line with these results, empagliflozin reduced the occurrence of hospitalization for HF by 35% in the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients–Removing Excess Glucose and by 39% in the subgroup of patients with diabetes and kidney disease [27]. Likewise, another large-scale cardiovascular outcome study, the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study, reported a decrease in hospitalization for HF of 33% in patients randomized to canagliflozin versus placebo [7]. The recently completed Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58 trial investigated the effects of dapagliflozin in patients at high cardiovascular risk and reported that dapagliflozin reduced the occurrence of the composite kidney outcome by 47%. Furthermore, risk for hospitalization due to HF decreased by 27% on dapagliflozin [5]. A meta-analysis of the three cardiovascular outcome trials confirmed the consistent and strong effect of SGLT2 inhibitors in reducing the risk of hospitalization for HF and progression of renal disease [28]. These observed effects are very similar to our PRE score predictions in patients with elevated albuminuria. The ongoing Dapagliflozin on Renal Outcomes and Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease trial, described in the companion article, will provide a more clear answer whether the predicted effects of dapagliflozin in patients with CKD are accurate (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03036150).

Although the mechanisms underlying the multipotent action of SGLT2 inhibitors are not completely understood, several lines of evidence suggest that the normalization of tubuloglomerular feedback plays a key role in the renoprotective effects [29]. In addition, dapagliflozin-induced natriuretic/osmotic diuresis and the resultant volume contraction may contribute to enhanced fluid clearance from the interstitial space and explain the reduction in HF risk [30–32]. However, the favourable cardiorenal effects of dapagliflozin are potentially counterbalanced by other non-beneficial effects, including alterations in calcium and phosphate homeostasis [33]. Prior studies have shown modest increases in phosphate during dapagliflozin therapy that were explained by increased activity of the -− transporter, leading to a reduction in phosphate clearance and compensatory increases in parathyroid hormone and fibroblast growth factor 23 [33–35]. The increase in serum phosphate levels observed in our analysis translated into a small increase in estimated kidney and HF risk. Yet the benefits associated with improvements in multiple risk markers outweighed this small increase in risk.

What is the applicability of the PRE score for future clinical trials and patient care? Changes in single risk markers often insufficiently predict the long-term drug effect on clinical outcomes, as shown by multiple clinical trials [22, 36–38]. Integrating multiple short-term risk marker changes has the potential to better predict long-term treatment effects [39]. Accurate long-term risk prediction is important to better predict the long-term effect of a drug in daily patient care as well as to improve the design of clinical trials. As such, the PRE score can be used in clinical practice to better predict the long-term effect of a drug for an individual patient and during early drug development to determine if a new drug is likely to be effective and to inform power and sample size calculations [39].

A main limitation of this study is that we could not include all relevant biomarkers that are associated with kidney and HF outcomes. For example, we ideally would have used N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide as a marker for volume status instead of body weight, as the latter may merely represent initial volume contraction rather than sustained alterations in fluid handling. In addition, the number of patients with UACR >200 mg/g and eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 was relatively small, which limits the precision of our effect estimates. Furthermore, some patients did not use concomitant RAAS inhibition. In the ongoing kidney outcome trials of SGLT2 inhibitors, nearly all patients are receiving RAAS inhibition. We do not believe, however, this influences our predictions, as it has been shown that the effects of dapagliflozin on all cardiovascular risk markers included in our analysis are consistent regardless of concomitant RAAS inhibition [40].

In conclusion, the PRE score predicted clinically meaningful reductions in kidney and HF endpoints associated with dapagliflozin therapy in patients with diabetic kidney disease. These results support a large long-term outcome trial in this population to confirm the benefits of the drug on these endpoints.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The dapagliflozin clinical trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca. We thank all investigators, patients and support staff.

FUNDING

The dapagliflozin clinical trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca. This study was conducted in the framework of the Innovative Medicines Initiative BEAt-DKD programme. The BEAt-DKD project has received funding from the IMI2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement 115974. This joint undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. H.J.L.H. is supported by a Vidi grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (917.15.306).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

N.M.A.I. and H.J.L.H. designed the study, conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript. D.C.W., B.V.S. and D.C.S. made contributions to the conception and design of the study and the acquisition of data. M.J.P., D.C.W., B.V.S. and D.C.S. performed revisions for important intellectual content.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

N.M.A.I. and M.J.P. report no conflicts of interest. H.J.L.H. is a consultant for AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe and MundiPharma and has a policy that all honoraria are paid to his employer. D.C.W. has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline and Vifor Fresenius. D.C.S. and B.V.S. are employees and shareholders of AstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(Suppl 1): S14–S80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jonnalagadda VG, Kasala ER, Sriram CS.. Diabetes and heart failure: are we in the right direction to find the right morsel for success? JACC Heart Fail 2018; 6: 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lambers Heerspink HJ, Chertow GM, Akizawa T. et al. Baseline characteristics in the Bardoxolone methyl EvAluation in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Occurrence of renal eveNts (BEACON) trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28: 2841–2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wen CP, Chang CH, Tsai MK. et al. Diabetes with early kidney involvement may shorten life expectancy by 16 years. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP. et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE. et al. Empagliflozin and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, established cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2018; 137: 119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW. et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cefalu WT, Leiter LA, Yoon KH. et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (CANTATA-SU): 52 week results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013; 382: 941–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heerspink HJ, Johnsson E, Gause-Nilsson I. et al. Dapagliflozin reduces albuminuria in patients with diabetes and hypertension receiving renin-angiotensin blockers. Diabetes Obes Metab 2016; 18: 590–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fioretto P, Stefansson BV, Johnsson E. et al. Dapagliflozin reduces albuminuria over 2 years in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and renal impairment. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 2036–2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sjostrom CD, Johansson P, Ptaszynska A. et al. Dapagliflozin lowers blood pressure in hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2015; 12: 352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smink PA, Miao Y, Eijkemans MJ. et al. The importance of short-term off-target effects in estimating the long-term renal and cardiovascular protection of angiotensin receptor blockers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014; 95: 208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schievink B, de Zeeuw D, Parving HH. et al. The renal protective effect of angiotensin receptor blockers depends on intra-individual response variation in multiple risk markers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 80: 678–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smink PA, Hoekman J, Grobbee DE. et al. A prediction of the renal and cardiovascular efficacy of aliskiren in ALTITUDE using short-term changes in multiple risk markers. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014; 21: 434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrannini E, Ramos SJ, Salsali A. et al. Dapagliflozin monotherapy in type 2 diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control by diet and exercise: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 2217–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailey CJ, Gross JL, Hennicken D. et al. Dapagliflozin add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 102-week trial. BMC Med 2013; 11: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strojek K, Yoon KH, Hruba V. et al. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control with glimepiride. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2013; 138(Suppl 1): S16–S26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kohan DE, Fioretto P, Tang W. et al. Long-term study of patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment shows that dapagliflozin reduces weight and blood pressure but does not improve glycemic control. Kidney Int 2014; 85: 962–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilding JP, Woo V, Rohwedder K. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving high doses of insulin: efficacy and safety over 2 years. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 124–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cefalu WT, Leiter LA, de Bruin TW. et al. Dapagliflozin’s effects on glycemia and cardiovascular risk factors in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a 28-week extension. Diab Care 2015; 38: 1218–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leiter LA, Cefalu WT, de Bruin TW. et al. Dapagliflozin added to usual care in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus with preexisting cardiovascular disease: a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a 28-week extension. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 1252–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ. et al. Cardiorenal end points in a trial of aliskiren for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 2204–2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bays HE, Sartipy P, Xu J. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with type II diabetes mellitus, with and without elevated triglyceride and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J Clin Lipidol 2017; 11: 450–458.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heerspink HJ, Kropelin TF, Hoekman J. et al. Drug-induced reduction in albuminuria is associated with subsequent renoprotection: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 2055–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roscioni SS, Lambers Heerspink HJ, de Zeeuw D.. Microalbuminuria: target for renoprotective therapy PRO. Kidney Int 2014; 86: 40–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sonesson C, Johansson PA, Johnsson E. et al. Cardiovascular effects of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and different risk categories: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016; 15: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM. et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I. et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet 2019; 393: 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heerspink HJ, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH. et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation 2016; 134: 752–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dailey G. Empagliflozin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: an overview of safety and efficacy based on Phase 3 trials. J Diabetes 2015; 7: 448–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hallow KM, Helmlinger G, Greasley PJ. et al. Why do SGLT2 inhibitors reduce heart failure hospitalization? A differential volume regulation hypothesis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018; 20: 479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lambers Heerspink HJ, de Zeeuw D, Wie L. et al. Dapagliflozin a glucose-regulating drug with diuretic properties in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 853–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor SI, Blau JE, Rother KI.. Possible adverse effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on bone. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 8–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Jong MA, Petrykiv SI, Laverman GD. et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on circulating markers of phosphate homeostasis, a post-hoc analysis of a randomized cross-over trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 14: 66–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Filippatos TD, Tsimihodimos V, Liamis G. et al. SGLT2 inhibitors-induced electrolyte abnormalities: an analysis of the associated mechanisms. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2018; 12: 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W. et al. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 905–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK. et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1547–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nissen SE, Wolski K.. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2457–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heerspink HJ, Grobbee DE, de Zeeuw D.. A novel approach for establishing cardiovascular drug efficacy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014; 13: 942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weber MA, Mansfield TA, Alessi F. et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on blood pressure in hypertensive diabetic patients on renin-angiotensin system blockade. Blood Press 2016; 25: 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.