Abstract

Background

Traditional medicines (TMs) have been used to treat common cold in Asia, but no studies have been conducted to examine the trend of use for several years. The objective of this study was to analyze the prescription patterns of TMs for common cold using national claims data accrued over 7 years in Korea. This will contribute to the scientific evidence enhancing the understanding of TM use for the treatment of common cold.

Methods

This study analyzed national claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. We extracted data for diagnosis of common cold (Korean Standard Classification of Diseases: J00, Acute nasopharyngitis) and prescriptions of TMs for adults who visited all types of oriental medical institutions during 2010–2016. We estimated the prescription patterns of TMs by sex, age group, and year.

Results

We extracted 3,014,428 prescriptions. The total number of prescriptions increased by 125.1% in 2016 compared to that in 2010. For all ages and periods, the number of prescriptions in women was higher than that in men. The age range with the most prescriptions was 70–79 years. The seven most prescribed TMs for common cold were Socheongnyongtang, Samso-eum, Yeongyopaedoksan, Insampaedoksan, Gumigohwaltang, Galgeuntang, and Hyeonggae-yeongyotang.

Conclusion

This was the first study to analyze the prescription patterns of TMs for common cold using National Health Insurance data in Korea. This study provides scientific evidences on the disease burden and the utilization pattern of TMs for common cold to support decision making on initiatives such as allocation and management of health resources.

Keywords: Traditional medicine, Common cold, Prescription pattern

1. Background

Traditional medicine (TM) is leveraged with Western medicine in a healthcare delivery system in South Korea.1 TM, which has developed over several years in Korea, considers the interaction between various factors such as the body, mind, and environment in the treatment of diseases.2 TM is based on comprehensive values such as personalized treatment through communication with patients, preventive medicine emphasizing immunity, and safe treatment using TM and non-surgical modalities.3 Despite these values, positive and negative perceptions of TM coexist, according to a recent survey. The reasons for the positive perception include usefulness proven by its utilization for hundreds of years, safety because of a minimal side effects, effectiveness, and comfort.4 However, TMs are covered narrowly by the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Korea in comparison to other countries in Asia.5 As society ages, the demand for healthcare policies on TM has increased.6 Decision-makers should develop appropriate policies for the judicious distribution of limited resources within healthcare, which increases the need for scientific evidence in support of TM. Epidemiologic research provides the most fundamental scientific basis for evidence-based and essential medicine. Recently, many reports and articles have been published on the epidemiology and utilization patterns of TM using various resources in Korea and wordwide.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Additionally, TMs have been used extensively for treating respiratory diseases such as common cold or asthma.8, 12, 13, 14 Common cold is the most frequently occurring disease, and it reduces productivity in adults, which results in a significant national burden.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In addition, antimicrobial resistance to drugs commonly used to treat common cold also has worsened the burden of the disease.24, 25, 26, 27

TMs represent viable alternatives for treating common cold as the overuse of antibiotics in adult patients has resulted in drug resistance and increased societal burden. TMs have been traditionally prescribed for common cold in Asian countries.28 According to previous studies conducted in Korea and Japan, clinicians have been prescribing TMs for the treatment of diseases and the promotion of health because they are considered safe with few side effects.29, 30, 31, 32 Scientific evidence on key indicators, such as the economic burden and utilization patterns, is required to emphasize the advantages of TMs in treating common cold. This will help in garnering relevant political support including the expansion of NHI coverage and investment in TMs. However, no national study has been conducted to analyze the utilization patterns of TMs as treatments for common cold, except for one in Taiwan that used sample claims data accrued over a year.9 The purpose of this study was to assess the utilization patterns of TMs for the treatment of common cold in Korea using national claims data; this would provide scientific evidence to support healthcare decision-making.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and study process

This study analyzed national claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) database, which covers the entire population of South Korea.33, 34 The claims data of the HIRA include unidentifiable information on patients’ diagnoses, treatments, procedures, surgical histories, and prescription drugs. For laboratory data, we were able to identify whether patients received specific laboratory tests. However, the test results were not provided in the claims data.35 The process involved in acquiring claims data from HIRA was as follows: request for data, review and approval by the HIRA committee, acquisition of permission for remote access of the analysis server, analysis of the claims data, and the transfer of results from the virtual computer to the local computer. As part of the data request process, the data provision agreement, personal information provision agreement, security and compliance agreement, and the summary of the research plan with the document of exemption or approval by IRB were prepared and submitted to the HIRA committee. The review and approval by the HIRA committee took several months. After approval by HIRA, the permission for remote access of the analysis server was granted. Claims data were analyzed on a virtual computer in the analysis server and the results were transferred to a personal computer after obtaining permission. Raw data used for analysis cannot be exported.36 From the HIRA database, we extracted all claims data containing the diagnosis of common cold (Korean Standard Classification of Diseases [KCD], 5th and 6th revision [KCD-5 and KCD-6]: J00, Acute nasopharyngitis [Common cold]) and the prescriptions of TMs for common cold among adults (age ≥ 20 years) visiting the oriental medical center from January 2010 to December 2016. To determine the diagnosis code for analysis, we referred to the “Korean Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline for Common Cold” recently published in Korea.37 This guideline assigned a patient with common cold to the diagnosis code J00 of KCD-7, which is the same as that of KCD-5 and KCD-6. In addition, we used 54 types of herbal formula as TMs for common cold in our study. In Korea, NHI has covered 126 types of TMs including 68 single herb preparations (as extract powder) and 56 herbal formulas (as mix extract powder) since 1990.8 Among these, we selected TMs to be used for analysis, based on the opinion of a clinical expert practicing in a University hospital (Appendix 1).38 We considered all types of oriental medical institutions including oriental hospitals, oriental clinics, and Korean medicine department in medical institutions. This study was certified as exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the Pusan National University Korean Medicine Hospital (E2016011).

2.2. Outcome measures

We first estimated the number and proportion of prescriptions of TMs by sex and age group. Next, we examined the annual number of TM prescriptions from 2010 to 2016. Finally, we identified the 7 most prescribed TMs for common cold and analyzed the number of prescriptions stratified by year. We performed a descriptive analysis and presented continuous variables as mean ± SD and categorical variables as frequency (%) using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We used Microsoft Excel to create graphs and tables based on the descriptive analysis after obtaining the relevant information from the SAS output.

3. Results

3.1. Prescriptions of TMs for common cold by sex and age group

We extracted 3,014,428 prescriptions from the claims data accrued from 2010 to 2016. In all age groups, the number of prescriptions for common cold in women was higher than that in men. The age range with the highest number of TM prescriptions in both men and women was 70–79 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of prescriptions of traditional medicines for common cold stratified by sex and age group.

| Age group | Number of prescriptions for common cold |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N, %) | Male (N, %) | Female (N, %) | ||||

| Total | 4,959,287 | 1,346,319 | 3,612,968 | |||

| 20−29 | 342,422 | (6.90%) | 99,406 | (7.38%) | 243,016 | (6.73%) |

| 30−39 | 666,621 | (13.44%) | 185,214 | (13.76%) | 481,407 | (13.32%) |

| 40−49 | 822,967 | (16.59%) | 235,499 | (17.49%) | 587,468 | (16.26%) |

| 50−59 | 863,983 | (17.42%) | 224,023 | (16.64%) | 639,960 | (17.71%) |

| 60−69 | 965,732 | (19.47%) | 257,659 | (19.14%) | 708,073 | (19.60%) |

| 70−79 | 1,033,259 | (20.83%) | 277,993 | (20.65%) | 755,266 | (20.90%) |

| ≥ 80 | 264,303 | (5.33%) | 66,252 | (4.92%) | 197,778 | (5.47%) |

3.2. Prescriptions of TMs for common cold by year

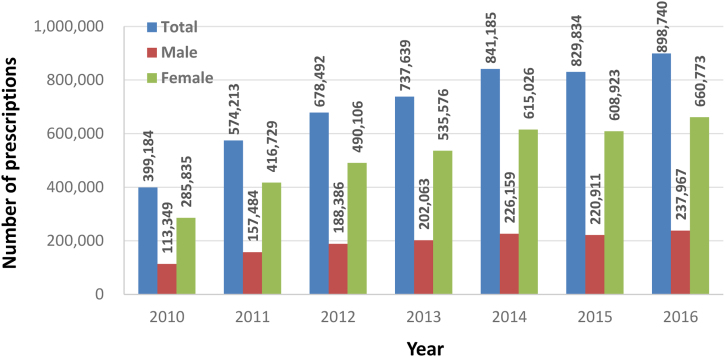

Fig. 1 shows the annual number of TM prescriptions for common cold from 2010 to 2016. The number of prescriptions in 2016 increased by 125.1% from 2010 (male, 109.9%; female, 131.2%). The rate of change in the number of prescriptions during the period between a given year and its preceding year was highest in 2011 (43.9%).

Fig. 1.

Annual number of prescriptions from 2010 to 2016.

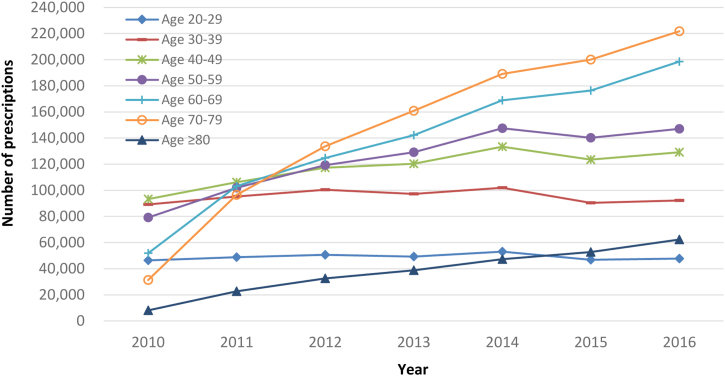

An analysis of the annual number of prescriptions stratified by age group revealed that the rate of increase was higher in the older age group. During the 7 years, the number of prescriptions increased by 2.9%, 3.5%, 38.5%, and 85.6% in patients who were 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 years old, respectively. The rate increased extremely in patients ≥ 60 years of age. From 2010–2016, the number of prescriptions increased by 282.9%, 607.0%, and 676.1% for patients who were 60–69, 70–79, and ≥ 80 years of age (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prescription trends stratified by age group and year.

3.3. The most prescribed TMs for common cold

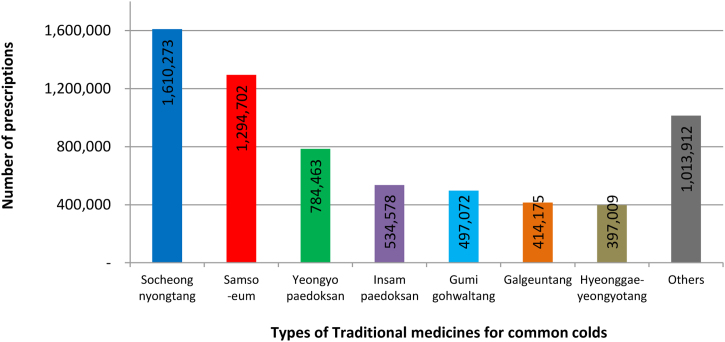

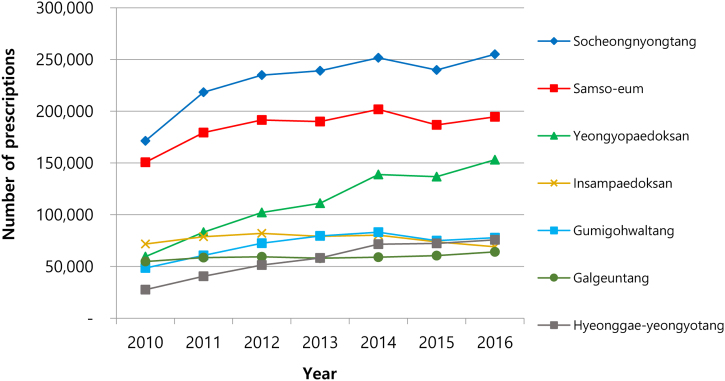

The seven most prescribed medicines were Socheongnyongtang, Samso-eum, Yeongyopaedoksan, Insampaedoksan, Gumigohwaltang, Galgeuntang, and Hyeonggae-yeongyotang. These medications accounted for 84.51% of the total TM prescriptions between 2010 and 2016 (Fig. 3). Except for Insampaedoksan, the number of prescriptions for all the top seven TMs increased during the 7 years. In all periods, Socheongnyongtang and Samso-eum were always the most and second-most prescribed TMs, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Number of traditional medicine prescriptions stratified by the type of traditional medicine between 2010 and 2016.

Fig. 4.

Number of traditional medicine prescriptions stratified by year and the type of traditional medicine.

4. Discussion

This is the first retrospective cross-sectional study that analyzed the TM prescription patterns for common cold using NHI data in Korea. South Korea launched the NHI with coverage for 26 types of TMs through a pilot project in 1984 and expanded this to 56 types in 1990.8 We found that several TMs were prescribed for the treatment of common cold, and the number has been increasing every year. We evaluated the prescription patterns of TMs in the treatment of common cold by various factors such as age, sex, year, and the type of TM.

According to the results stratified by sex, women were prescribed more TMs for common cold than men between 2010 and 2016. Similar results were reported by previous studies in Taiwan, Japan, and Korea, which also analyzed the usage patterns of TM.4, 7, 32, 39 According to previous studies that analyzed attitudes and trusts for TMs, women generally trusted TMs and visited oriental medical centers more often than men.4, 30, 40 Conboy et al. reported that women were more interested in health and may actively explore and practice various health plans and management.41, 42 However, more comprehensive research is needed to determine why women’s utilization rate is higher than that of men in TMs.

According to the results by year, the number of prescriptions continued to increase except in 2015. In a previous study that analyzed the use of TMs regardless of indications, the total number of prescriptions for three TMs including Socheongnyongtang, Samso-eum, and Insampaedoksan also slightly decreased in 2015.43 As far as we know, there were no policy factors that could affect the decline of TMs in 2015. Additional research is required to determine why the number of prescriptions did not increase in 2015. In our study, the total number of prescriptions of TMs for common cold increased by 125.14% in 2016 from 2010. Previous studies also showed that the utilization rate of TM increased with time.8, 11, 40 Kwon et al., in comparing the use of TM in 2011 and 2014, reported that the adoption of treatments such as acupuncture, moxibustion, cuppinig, and chuna decreased, while herbal medicine use increased.40 Due to the limitation of the cross-sectional study design, we could not certain the factors that influenced the change in TM prescription for common cold. However, according to previous studies, age is closely related to the use of TM.39, 44 The Korean society is rapidly aging, and this may have influenced the increase in the annual use of TM. Further studies are required to ascertain the overall factors influencing the increase in TM use.

Our study showed that the annual number of TM prescriptions for common cold increased with age, especially in patients aged 60 years or older. This trend was more evident between 2010 and 2011. This may be attributed to the revision of the fixed copayment program for outpatients aged 65 years or older in Korea. In 2011, the standard price of the fixed copayment program for older adults increased from 15,000 won to 21,000 won. A previous study reported that this revision significantly influenced the increase in the number of TM prescriptions, especially for patients over 65 years of age.45 As another possible cause, the differences in the perception of TM by age may have influenced the use of TM for common cold. In Korea, previous studies reported that trust was lower in younger age groups.4, 30, 40 Kwon et al. reported that the “lack of scientific evidence” was the main reason for distrust in TMs in younger age groups, which was consistent with findings from other studies.40 In our study, the number of prescriptions was highest in patients who were 70–79 years of age, but in Taiwan, patients who were 30–59 years of age used TMs for common cold more than any other group.9 Our study analyzed the claims data based on a prescription unit, while the Taiwan study performed the analysis based on a patient unit, and this may have contributed to the difference. In addition, different policies and clinical applications for TMs in the two countries may have affected the prescription patterns.39, 46 For a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the TM prescription patterns, additional studies considering disease indication, efficacy, national policies, and perception of TM are required.

In this study, we identified the most commonly prescribed TMs for treating common cold. Socheongnyongtang and Samso-eum were the two most prescribed drugs from 2010 to 2016. Socheongnyongtang consists of eight species of medicinal plants, and it is used to treat cold with persistent external symptoms, including fever, cough, and dyspnea. Samso-eum is a decoction of Sappan Lignum and is used to treat symptoms of common cold, including chills, fever, spontaneous sweating, headache, nasal congestion, and cough with sputum.47 Following these two drugs, the most frequently prescribed drugs for common cold were Yeongyopaedoksan, Insampaedoksan, Gumigohwaltang, Galgeuntang, and Hyeonggae-yeongyotang, in descending order. Yeongyopaedoksan has been used to treat respiratory and inflammatory diseases. Insampaedoksan, the original version of Yeongyopaedoksan, is usually used to treat fevers with headache and joint, and generalized pain.48 Gumigohwaltang is used to treat headaches, joint pain, aversion to cold with fever, absence of sweating, and floating and tense pulse.49 Galgeuntang and Hyeonggae-yeongyotang are also used to treat sequelae of common cold, including inflammation.50, 51 TMs commonly used for treating common cold in Taiwan, according to a study, were Yin-Qiao-San, Xin-Yi-Qing-Fei-Tang, Ma-Xing-Gan-Shi-Tang, Chuan-Xiong-Cha-Tiao-San, Ge-Gen-Tang, Xin-Yi-San, and Jing-Fang-Bai-Dun-San.9 The different findings from our study may be attributed to the influence of the environment, culture, and race on the development and use of TM.5 Another factor may be the differences between the healthcare systems for TMs in different countries. The Taiwanese NHI covers 337 types of Chinese herbal formulas and over 500 types of Chinese single herbal preparations, while the Korean NHI covers only 56 herbal formulas and 68 single herb preparations.52 This difference in coverage may have affected the burden of treatment and limited the range of TMs prescribed.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, our study evaluated the usage patterns of TMs at a prescription level, which made it difficult to analyze the characteristics of patients using TMs for common cold. To better understand the factors affecting the patterns of TM use by patients with common cold, additional research using data prioritizing patient characteristics is necessary. Next, we were not able to evaluate over-the-counter or uninsured TM use, because we used claims data from the HIRA. Currently, only 56 herbal formulas (as mixed-extract powders) are covered by the NHI in Korea. However, the most commonly used forms of TM in clinical practice are packages of crude herbal decoction, which can be used flexibly to treat various conditions and diseases as over-the-counter or uninsured medication.8 To identify the treatment patterns involving these types of TMs, additional research, such as a survey or prospective study, is required.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to evaluate the annual prescription patterns of TMs used to treat common cold over a long period (7 years) using national claims data. A previous study conducted in Taiwan also analyzed TMs for common cold using health insurance data, but that study only used sample data accrued over a year (2011), making it difficult to identify long-term trends.9 Our study results are not only representative because the data was extracted from the national claims data, but also we analyzed the TM prescriptions over a long period stratified by age, sex, and the type of TM. In Korea, microbial resistance caused to antibiotics commonly used in treating common cold is frequent. Therefore, the advantage of TMs, which alleviate concerns about antibiotic resistance, cannot be over emphasized.53 However, investment in TMs in inadequate due to the high price and the lack of scientific evidence and policy support.54 We did not evaluate the effectiveness of TMs in this study, and to evaluate the role of TMs in reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance, future studies are required. However, we believe that our research, which had representative results on the use of TMs for common cold, can be used as a scientific basis for healthcare decision making for initiatives, such as the allocation and management of healthcare resources, that take the economic burden and the utilization patterns of TMs for common cold into consideration.

In this large-scale, nationwide, population-based study, we found that the adoption of TMs in treating common cold is increasing. The results of this study may be used as real-world evidence of utilization patterns of TMs for the treatment of common cold. Further studies evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of TMs are warranted.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HK, JYC, MH, and HSS. Methodology: HK, JYC, MH, and HSS. Validation: HK, JYC, MH, and HSS. Formal Analysis: HK. Investigation: HK, JYC, and HSS. Resources: HK, JYC, and HSS. Data Curation: HK and HSS. Writing – Original Draft: HK, JYC, MH, and HSS. Writing – Review & Editing: HK, JYC, and HSS. Visualization: HK. Supervision: JYC and HSS. Project administration: HK, JYC, and HSS. Funding Acquisition: JYC.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by the Traditional Korean Medicine R&D Program funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) (HB16C0006).

Ethical statement

This research has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pusan National University Korean Medicine Hospital (IRB number: E2016011).

Data availability

We used the data provided by the HIRA (M20170828763); however, we declare that the results do not reflect the positions of either the HRIA or the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Health Insurance Review and Assessment but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and they are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Health Insurance Review and Assessment.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2020.100458.

Supplementary material

The following are Supplementary material to this article:

References

- 1.Lee T. SAGE Publications Sage UK; London, England: 2015. The integration of Korean medicine in South Korea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin C.S., Ko S.-G. Introduction to the history and current status of evidence-based Korean medicine: A unique integrated system of allopathic and holistic medicine. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/740515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han S.Y., Kim H.Y., Lim J.H., Cheon J., Kwon Y.K., Kim H. The past, present, and future of traditional medicine education in Korea. Integr Med Res. 2016;5(2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo J.-M., Park E.-J., Lee M., Ahn M., Kwon S., Koo K.H. Changes in attitudes toward and patterns in traditional Korean medicine among the general population in South Korea: a comparison between 2008 and 2011. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):436. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park H.-L., Lee H.-S., Shin B.-C. Traditional medicine in China, Korea, and Japan: A brief introduction and comparison. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/429103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han D.W., Lim B. 2005. Strategies to scale-up the public role of traditional Korean medical services for the future society. Presidential committee on ageing society and population policy. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh S.C., Lai J.N., Lee C.F., Hu F.C., Tseng W.L., Wang J.D. The prescribing of Chinese herbal products in Taiwan: A cross‐sectional analysis of the national health insurance reimbursement database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(6):609–619. doi: 10.1002/pds.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim B. Korean medicine coverage in the National Health Insurance in Korea: Present situation and critical issues. Integr Med Res. 2013;2(3):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J.-S., Ho C.-H., Hsu Y.-C., Wang J.-J., Hsieh C.-L. Traditional Chinese medicine treatments for upper respiratory tract infections/common colds in Taiwan. Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6(5):538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh R.-Y., Seol I.-C., Son C.-G. Randomized clinical controlled trials of a herb remedies in Korea - systematic review. J Korean Oriental Med. 2010;31(4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo S., Park B.H., Choi S.-J. A study on the sociodemographic characteristics of adult users of Korean traditional medicine. J Korean Public Health Nurs. 2016;30(1):136–148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong C.D. Complementary and alternative medicine in Korea: Current status and future prospects. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7(1):33–40. doi: 10.1089/107555301753393788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bent S. Herbal medicine in the United States: Review of efficacy, safety, and regulation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):854–859. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0632-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek S.-M., Choi S.M., Seo H.-J., Kim S.G., Jung J.-H., Lee M. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by self-or non-institutional therapists in South Korea: A community-based survey. Integr Med Res. 2013;2(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allan G.M., Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: Making sense of the evidence. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(3):190–199. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monto A.S., Ullman B.M. Acute respiratory illness in an American community: The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Driel M.L., Scheire S., Deckx L., Gevaert P., De Sutter A. What treatments are effective for common cold in adults and children? BMJ. 2018;363:k3786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fashner J., Ericson K., Werner S. Treatment of the common cold in children and adults. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(2):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bramley T.J., Lerner D., Sarnes M. Productivity losses related to the common cold. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(9):822–829. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fendrick A.M., Monto A.S., Nightengale B., Sarnes M. The economic burden of non–influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):487–494. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruez P. Quality and bottom-line can suffer at the hands of the working sick. Managed Healthcare Executive. 2004;14(11):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y.-M., Jung M.-H. Economic impact according to health problems of workers. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2008;38(4):612–619. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2008.38.4.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotsimbos T., Armstrong D., Buckmaster N., de Looze F., Hart D., Holmes P. Respiratory infectious disease burden in Australia. Austral Lung Found. 2007:612–619. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y.-I., Kim S.T. 2019. 2018 national health insurance statistical yearbook. wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, National Health Insurance Service. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Hong-Bin. Clinical and economic burden of infection with six multi-drug resistant organisms. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gandra S., Barter D., Laxminarayan R. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance: how much do we really know? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):973–980. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norrby R., Powell M., Aronsson B., Monnet D.L., Lutsar I., Bocsan I.S. The bacterial challenge: Time to react - a call to narrow the gap between multidrug-resistant Bacteria in the EU and the development of new antibacterial agents. ECDC/EMEA Joint Technical Report. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W., Liu B., Wang L.-Q., Ren J., Liu J.-P. Chinese patent medicines for the treatment of the common cold: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):273. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang S., Kim K.H., Sun S.-H., Go H.-Y., Lee E.-K., Jang B.-H. Characteristics of herbal medicine users and adverse events experienced in South Korea: A Survey study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/4089019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim D.-H., Cho M.-K., Hong M.-N., Cho M.-K. A survey in the general population on the perception of the common cold treatment at the Korean medical clinic. J Intern Korean Med. 2017;38(3):336–352. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moschik E., Mercado C., Yoshino T., Matsuura K., Watanabe K. Usage and attitudes of physicians in Japan concerning traditional Japanese medicine (kampo medicine): A descriptive evaluation of a representative questionnaire-based survey. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/139818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katayama K., Yoshino T., Munakata K., Yamaguchi R., Imoto S., Miyano S. Prescription of kampo drugs in the Japanese health care insurance program. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/576973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon H.-K., Park C., Jang S., Jang S., Lee Y.-K., Ha Y.-C. Incidence and mortality following hip fracture in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(8):1087–1092. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song S.O., Jung C.H., Song Y.D., Park C.-Y., Kwon H.-S., Cha B.S. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38(5):395–403. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim L., Kim J.-A., Kim S. A guide for the utilization of health insurance review and assessment service national patient samples. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36 doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi N.-K. Public health- and social pharmacy-related study using the Korean health insurance review and assessment service (HIRA) claims data. J Korean Acad Manag Care Pharm. 2015;4(1):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi J.-Y. 2017. Korean medicine clinical practice guideline for common cold. Guideline center for Korean medicine and the society of internal Korean medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministry of health and welfare. Announcement of details on application criteria and methods for medical care benefit by the National Health Insurance Act of 2009. 30 November 2009; No. 2009-214.

- 39.Huang C.-W., Hwang I.-H., Lee Y.-S., Hwang S.-J., Ko S.-G., Chen F.-P. Utilization patterns of traditional medicine in Taiwan and South Korea by using national health insurance data in 2011. PLoS One. 2018;13(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon S., Heo S., Kim D., Kang S., Woo J.-M. Changes in trust and the use of Korean medicine in South Korea: a comparison of surveys in 2011 and 2014. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):463. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conboy L., Patel S., Kaptchuk T.J., Gottlieb B., Eisenberg D., Acevedo-Garcia D. Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine: An analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample. J Altern Complement Med: Res Paradigm Pract Policy. 2005;11(6):977–994. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wade C., Chao M., Kronenberg F., Cushman L., Kalmuss D. Medical pluralism among American women: Results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2008;17(5):829–840. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service . 2017. Claims status of reimbursable drugs. Gangwondo; 2018 June. Report No.: G000J61-2018-38. Available from: https://www.hira.or.kr/ebooksc/ebook_477/ebook_477_201806041037009230.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang B.-R., Choi I.Y., Kim K.-J., Kwon Y.D. Use of traditional Korean medicine by patients with musculoskeletal disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeong D.-B. 2017. Analysis of the behavior of Korean medical doctors before and after upward revision of elderly outpatients copayment system [Master’s thesis]: The Graduate School of Seoul National University. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L., Fu Y., Zhang L., Zhao S., Feng Q., Cheng Y. Clinical application of traditional herbal medicine in five countries and regions: Japan; South Korea; Mainland China; Hong Kong, China; Taiwan, China. J Tradit Chinese Med Sci. 2015;2(3):140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiao Y., Liu J., Jiang L., Liu Q., Li X., Zhang S. Guidelines on common cold for Traditional Chinese Medicine based on pattern differentiation. J Tradit Chinese Med. 2013;33(4):417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(13)60141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byun J.-S., Yang S.-Y., Jeong I.-C., Hong K.-E, Kang W., Yeo Y. Effects of So-cheong-ryong-tang and Yeon-gyo-pae-dok-san on the common cold: Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133(2):642–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park H., Hwang Y.-H., Jang D., Ha J.-H., Jung K., Ma J.Y. Acute toxicity study on Gumiganghwal-tang and fermented Gumiganghwal-tang extracts. Herb Formula Sci. 2012;20(2):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee S.Y., Lee J.Y., Kang W., Kwon K.-I., Park S.-K., Oh S.J. Cytochrome P450-mediated herb–drug interaction potential of Galgeun-tang. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gang S.G., Cho N.J., Kim J.Y., Han H.S., Kim K.K. Investigation of antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities of the hyeonggaeyeongyotang gagambang. Korea J Herbol. 2018;33(4):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang C.-W., Hwang I.-H., Yun Y.-H., Jang B.-H., Chen F.-P., Hwang S.-J. Population-based comparison of traditional medicine use in adult patients with allergic rhinitis between South Korea and Taiwan. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2018;81(8):708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sul M.-C., Lim D.-J., Park Y.-J., Bang J.-H., Kim J.-H., Choi J.-Y. A systematic review in the journals under Korean oriental medical society. J Intern Korean Med. 2010:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chae J.-M., Choi Y.-J., Choi Y.-M. A study on the rationalization of insurance benefits for Korean medicine services. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We used the data provided by the HIRA (M20170828763); however, we declare that the results do not reflect the positions of either the HRIA or the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Health Insurance Review and Assessment but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and they are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Health Insurance Review and Assessment.