Abstract

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (s-AKI) has a staggering impact in patients and lacks any treatment. Incomplete understanding of the pathogenesis of s-AKI is a major barrier to the development of effective therapies. We address the gaps in knowledge regarding renal oxygenation, tubular metabolism, and mitochondrial function in the pathogenesis of s-AKI using the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model in mice. At 24 h after CLP, renal oxygen delivery was reduced; however, fractional oxygen extraction was unchanged, suggesting inefficient renal oxygen utilization despite decreased glomerular filtration rate and filtered load. To investigate the underlying mechanisms, we examined temporal changes in mitochondrial function and metabolism at 4 and 24 h after CLP. At 4 h after CLP, markers of mitochondrial content and biogenesis were increased in CLP kidneys, but mitochondrial oxygen consumption rates were suppressed in proximal tubules. Interestingly, at 24 h, proximal tubular mitochondria displayed high respiratory capacity, but with decreased mitochondrial content, biogenesis, fusion, and ATP levels in CLP kidneys, suggesting decreased ATP synthesis efficiency. We further investigated metabolic reprogramming after CLP and observed reduced expression of fatty acid oxidation enzymes but increased expression of glycolytic enzymes at 24 h. However, assessment of functional glycolysis revealed lower glycolytic capacity, glycolytic reserve, and compensatory glycolysis in CLP proximal tubules, which may explain their susceptibility to injury. In conclusion, we demonstrated significant alterations in renal oxygenation, tubular mitochondrial function, and metabolic reprogramming in s-AKI, which may play an important role in the progression of injury and recovery from AKI in sepsis.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, mitochondria, metabolism, oxygenation

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and severe complication in hospitalized patients and affects nearly 70% of adult intensive care unit admissions (1, 4, 49, 52). Sepsis accounts for nearly 50% of episodes of AKI in critically ill patients (2, 52). The incidence of AKI rises with the increasing severity of sepsis and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (1, 2, 4, 49, 52). Yet, therapeutic strategies have been generic, supportive, and largely ineffective. Limited understanding of the multifactorial pathogenesis of AKI in sepsis is a major barrier to progress, and, therefore, systematic research to advance our knowledge is vital (7).

Renal hemodynamics and oxygenation have a significant role in the pathophysiology of AKI (11, 38, 46). Until lately, renal vasoconstriction and hypoperfusion were implicated as the primary pathogenic factors in the development of AKI in sepsis (44). The primacy of renal hypoperfusion in sepsis-associated AKI (s-AKI) has been challenged in large animal models of sepsis (31, 32). However, detailed assessment of renal hemodynamics in rodent models is limited. The kidney is a highly metabolic organ and exhibits a high rate of oxygen consumption to support the energy requirements of tubular reabsorption of filtered solutes. Certain features of renal oxygenation, which include regional heterogeneity in renal blood flow and oxygen delivery as well as the close coupling of renal oxygen consumption to tubular transport, can increase the vulnerability of the kidney to hypoxia and injury. Despite the advances in cellular and molecular pathophysiology of AKI, changes in renal hemodynamics and oxygenation in s-AKI have received little attention. Hence, we conducted a detailed assessment of renal hemodynamics and oxygenation in the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model of s-AKI in mice.

In s-AKI, despite the dramatic decrease in renal function, structural injury is relatively mild without extensive tubular necrosis, which is observed in other forms of AKI (26, 30, 48). Sublethal injury with mitochondrial swelling in the proximal tubules has been described in animal models and in humans with sepsis (26, 48, 51). This may play an important role in the pathophysiology of AKI in sepsis since the majority of the energy to support solute reabsorption in the kidney is derived from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in renal tubules (36). Limited information is available on the detailed assessment of mitochondrial function and tubular metabolism in AKI after sepsis. We investigated various aspects of mitochondrial function and metabolism along the course of sepsis to understand the temporal sequence of changes after CLP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and per the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments were performed in adult male C57BL6/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) with age ranging from 9 to 12 wk. Mice were fed regular chow and water and maintained under standard housing conditions.

CLP model of sepsis.

As previously described (42), mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine via intraperitoneal injection. After the cecum had been localized and exteriorized, the stool was expressed to the tip of the cecum. A 6-0 silk ligature was placed at 50% of the length of the cecum. The cecum was then punctured once with a 25-gauge sterile needle from one side to the other. The smallest amount of feces material was extruded by gently squeezing the cecum, the cecum was returned to the abdomen, and the abdominal incision was then closed in two layers. Sham-operated (sham) mice underwent abdominal incision without any manipulation of the cecum. Pain control was provided by 1 mg/kg body wt of buprenorphine was administrated via intraperitoneal injection at the end of surgery and again at 6 h postoperatively. Fluid resuscitation was provided by 1 mL of warmed sterile saline, which was given subcutaneously immediately postoperatively and then again at 6 h postoperatively.

Inulin clearance and renal oxygen consumption.

As previously described (33, 50), [3H]inulin clearance was performed to measure the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at 24 h after CLP or sham surgery. Briefly, under anesthesia [Inactin (100 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg ip)], a tracheostomy tube was placed, and the left internal jugular, left femoral artery, and urinary bladder were cannulated. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C. At the end of the surgical preparation, mice underwent a 60-min equilibration period, during which time [3H]inulin in NaCl-NaHCO3 at a rate of 0.5 mL/h was infused. Mean arterial pressure was monitored by connecting the femoral artery catheter to a transducer using WinDaq software (DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH). Blood samples for hematocrit and [3H]inulin were obtained from the femoral artery catheter at the beginning and end of each urine collection for GFR measurements by clearance of [3H]inulin.

Renal blood flow (RBF; in mL/min) in the left kidney was monitored with a perivascular ultrasonic transit time flow probe (T420, Transonics, Ithaca, NY) connected to a computer for continuous recording. The proximal left renal vein was used for sampling of venous blood. After the surgical preparation, animals were allowed 60 min for stabilization with the flow probe in place while blood pressure and RBF were recorded. Blood samples were taken from both femoral arteries and renal veins for measurements of total arterial blood hemoglobin (tHb), O2Hb, Po2, and Pco2 using a blood gas analyzer (OPTI CCA and OPTI CCA-TS Blood Gas and Electrolyte Analyzers, Optimedical, Roswell, GA). Oxygen content (O2ct) was calculated by the following formula: O2ct (in mL/mL blood) = (1.39 × tHb × %O2Hb + Po2 × 0.003)/100.

Total left kidney oxygen consumption (Qo2; in mL/min) was calculated from the arteriovenous difference in O2ct multiplied by RBF. Renal oxygen delivery (Do2) was calculated by RBF × arterial O2ct. Fractional oxygen extraction (Fo2) was calculated by Qo2/Do2 × 100.

Fresh isolation of renal proximal tubules.

Mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine via intraperitoneal injection followed by cervical dislocation. As previously described (9, 57), the kidneys were immediately removed and placed in cold (0°C) HBSS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The renal capsule was removed, and the kidney was cut sagitally into two halves. The cortical tissue was removed, chopped/minced, and transferred to 10 mL HBSS-containing collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) at 200 U/mL for digestion. Tubules were incubated at 37°C while being rotated at 70 rpm for 15 min. The tubule suspension was mixed with a 10-mL pipette and returned to the incubator for an additional 15 min. Following digestion, tubules were divided into two 15-mL conical tubes with 5 mL per tube. Five milliliters of sterile, heat-inactivated horse serum (Invitrogen) was added to each tube, and the tube was vortexed for 30 s. After 1 min of sedimentation, the supernatant containing the proximal tubules was removed, transferred to another tube, and centrifuged for 7 min at 200 g. Tubules were washed once with 10 mL HBSS and centrifuged at 200 g for 7 min. After 90–95% of the supernatant was removed and discarded, tubules were resuspended in renal proximal tubule cell (RPTC) media, which consisted of DMEM-F-12 culture media (Invitrogen) containing 15 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM glutamine, 1 µM pyridoxine HCl, 15 mM sodium bicarbonate, 6 mM sodium lactate, 50 nM hydrocortisone, 50 µM L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and insulin-transferrin-selenium solution (5 mg/mL, 2.75 mg/mL, and 3.35 ng/mL, respectively, Invitrogen).

Ex vivo mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

Oxygen consumption in fresh, isolated proximal tubules was measured using an Agilent Seahorse XFe 96 extracellular flux analyzer (5, 14, 57). Isolated proximal tubules were seeded to a XFe 96-well cell culture microplate in 180 μL RPTC media. Isolated proximal tubules from sham and experimental groups (CLP) were examined simultaneously in the same microplate and analyzed accordingly. The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using mix/wait/measure times of 3/3/3 min, respectively. Sequential measurements were performed beginning with basal OCR and then after the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (1 μM) was added followed by the pharmacological uncoupler FCCP (0.5 μM) and finally with complex I (rotenone) and complex III (antimycin) inhibitors (0.5 μM) to each well per previoulsy published protocols (5, 8, 14, 57). The key parameters measured include basal OCR, ATP-linked OCR, maximal OCR, spare or reserve capacity, and nonmitochondrial OCR, as described in the results.

Ex vivo glycolysis measurement.

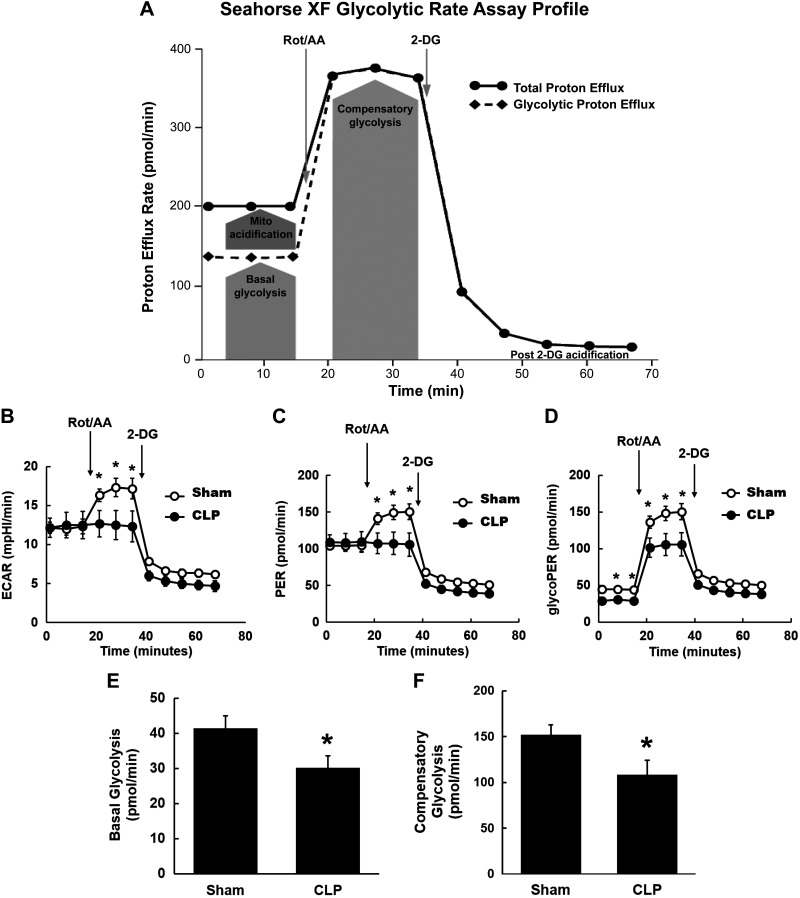

Experiments were conducted in fresh isolated proximal tubules using Agilent Seahorse XF glycolytic assays. During glycolysis, the conversion of glucose to pyruvate, and subsequently lactate, results in a net production and extrusion of protons into the extracellular medium, resulting in the acidification of the medium surrounding the cell. Using the Agilent Seahorse XF glycolysis stress test kit, the acidification of the medium was directly measured and reported as the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (14, 18). Isolated proximal tubules from CLP or sham mice were seeded to a XFe 96-well cell culture microplate in 180 μL RPTC media. Both groups were examined simultaneously in the same microplate and analyzed accordingly. Glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 μM), and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 50 mM) were inserted through the injection ports sequentially while measurements were made to calculate glycolytic capacity and reserve as described in the results. In separate experiments, we used the newer Seahorse XF glycolytic rate assay, which determines the protons exported by cells into the assay medium over time, the proton efflux rate (PER), expressed as picomoles per minute. Mitochondrial acidification is subtracted to determine glycolytic PER (glycoPER). The key parameter of this assay, glycoPER, correlates 1:1 with lactate accumulation over time. Isolated proximal tubules from CLP or sham mice were seeded to a XFe 96-well cell culture microplate in 180 μL Seahorse XF glycolytic rate assay media (containing glucose, glutamine, pyruvate, and HEPES buffer). Both groups were examined simultaneously in the same microplate and analyzed accordingly. Measurements were conducted under basal conditions and after mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitor [rotenone and antimycin (0.5 μM)] injection and glycolysis inhibitor [2-DG (50 mM)] injection. Agilent Seahorse glycolytic rate assay report generator was used to analyze and calculate basal and compensatory glycolysis, as described in results.

Western blot analysis.

Frozen kidneys were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 µg/mL leupeptin, with protease inhibitors (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (Cell Signaling). Protein concentration was determined using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Protein lysates (80 µg whole lysate, 60 µg cytosolic fraction, and 20 µg mitochondrial fraction) were separated by 4–12% bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Novex) in 1× MOPS-SDS running buffer (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred into semi-wet iBlot nitrocellulose transfer stacks (Invitrogen) for probing of proteins below 50 kDa. Proteins over 50 kDa were probed from nitrocellulose membranes that were transferred in transfer buffer containing 1× transfer buffer (Invitrogen), 10% methanol, and 0.001% antioxidant (Invitrogen). Membranes were incubated in 5% milk and Tris-buffered saline-Tween blocking buffer for 1 h in room temperature, after which the immunoblots were incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: anti-mitofusin-1 (Mfn1; ab57602, Abcam), anti-mitofusin-2 (Mfn2; ab50838, Abcam), anti-dynamin-like 120-kDa protein (OPA1; ab42364, Abcam), anti-6-phosphofructokinase, liver type (PFKL; ab37583, Abcam), anti-carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1; ab128568, Abcam), anti-carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT2; ab181114, Abcam), anti-acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (ACOX2; sc-514320, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-pyruvate kinase M1/2 (PKM; no. 3106S, Cell Signaling), anti-pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH; ab110334, Abcam), anti-phospho-PDH (ab177461, Abcam), anti-lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA; ab52488, Abcam), and anti-lactate dehydrogenase B (LDHB; ab85319, Abcam). β-Actin (A5316, Sigma-Aldrich) and GAPDH (no. 2118, Cell Signaling) were used as loading controls. After removal of the primary antibodies, the immunoblots were incubated in IRDye secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences) in room temperature for 1 h. Completed immunoblots were imaged on the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences) using their Odyssey Application software (version 3.0.25). Immunoblot images were analyzed with Image Studio software (Li-Cor, version 5.2.5).

Measurement of ATP content.

ATP content was measured by a fluorometric assay using the ATP colorimetric/fluorometric assay kit (catalog no. K354-100, BioVision). Approximately 20 mg of kidney tissue were homogenized in 200 µL ATP assay buffer. The tissue homogenate was deproteinized using the Deproteinization Sample Preparation Kit (catalog no. K808, BioVision). Fluorescence (excitation/emission = 535/587 nm) was measured in a microplate reader, and the ATP content was expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Kidneys were dissected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy (Qiagen) method following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, with a ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm (A260/280) >1.9 (indicating very high-quality RNA). cDNA was generated by RT-PCR using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kits (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR green (ThermoFisher Scientific) gene expression assay according to the company’s instruction. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time RT-PCR and mtDNA copy measurement

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| mtND-1 | 5′-CTGTTCCGGGGAATGTGGAG-3′ | 5′-AGACAAGACTGATAGACGAGGGG-3′ |

| PGC-1α | 5′-AGACAGGTGCCTTCAGTTCAC-3′ | 5′-GCAGCACACTCTATGTCACTC-3′ |

| TFAM | 5′-TAGGCACCGTATTGCGTGAG-3′ | 5′-CAGACAAGACTGATAGACGAGGG-3′ |

| β-Actin | 5′-CACTGTCGAGTCGCGTCC-3′ | 5′-TCATCCATGGCGAACTGGTG-3′ |

| PFK | 5′-CCATGTTGTGGGTGTCTGAG-3′ | ACAGGCTGAGTCTGGAGCAT-3′ |

| CPT1 | 5′-GGTCTTCTCGGGTCGAAAGC-3′ | 5′-TCCTCCCACCAGTCACTCAC-3′ |

mtND-1, mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; PFK, phosphofructokinase; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I.

mtDNA copy measurement.

Total DNA was isolated from the kidneys using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was quantified, and 5 ng were used for PCR. Relative mtDNA content was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR using primers for mitochondria-encoded NADH dehydrogenase 1 [NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND-1)] and was normalized to nuclear-encoded β-actin. Primer sequences for ND-1 and β-actin are shown in Table 1.

Electron microscopy.

Mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine via intraperitoneal injection. After perfusion with PBS, mice were perfused with modified Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4). Random pieces of kidney tissue were processed by immersion and fixation in modified Karnovsky’s fixative for at least 4 h. Samples were then transferred to the Electron Microscopy Core at the University of California-San Diego for imaging preparation. Blinded samples were provided to the pathologist for image analysis and interpretation. Electron microscopic analysis was performed on a Phillips EM208S electron microscope. Images were captured using the Advanced Microscopy Techniques camera and imaging software.

Statistical methods.

Data were analyzed by unpaired t test using commercial software (GraphPad). Paired t test was used to analyze paired experiments. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Unless stated otherwise, results are presented as group means ± SE.

RESULTS

Renal hemodynamics and oxygenation in s-AKI.

We performed in vivo measurements of renal hemodynamics and oxygenation at 24 h after CLP in mice. Systemic characteristics and renal functional measurements are shown in Table 2. Mean arterial pressure was reduced in CLP mice (P < 0.01) compared with sham mice. GFR, measured by [3H]inulin clearance, was significantly lower in CLP mice (P < 0.01). Renal plasma flow and filtration fraction were not significantly different between groups. We examined various parameters of renal oxygenation by measuring RBF, Do2, Qo2, and Fo2 in the left kidney during clearance experiments. These data are shown in Table 3. Hb, hematocrit, RBF, and consequently Do2 were significantly lower in CLP mice (P < 0.01), indicating reduced O2 supply to the kidney in sepsis. However, the arteriovenous difference in O2ct was not significantly different between CLP and sham mice. Total renal Qo2 was lower in the CLP mice but was driven by lower RBF as the oxygen extraction by the kidney was similar in both CLP and sham mice. Importantly, Fo2 was similar in CLP and sham mice. Renal Qo2 factored for GFR, which is a surrogate for the filtered load available for tubular reabsorption, was also not different in CLP mice compared with sham mice.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic and renal functional measurements at 24 h post-CLP

| Groups | n | Mean Arterial Pressure, mmHg | Glomerular Filtration Rate, mL/min | Renal Plasma Flow, mL/min | Filtration Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 7 | 90 ± 2.4 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| CLP | 10 | 73 ± 3.2 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| Analyses | P = 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.07 | P = 0.08 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE; n, number of animals. CLP, cecal ligation and puncture.

Table 3.

Renal oxygenation measurements (single kidney) at 24 h post-CLP

| Groups | n | Hemoglobin, g/dL | Hematocrit, % | Renal Blood Flow, ml/min | Renal Arteriovenous Difference in Oxygen Content, mL O2/mL blood | Oxygen Delivery, mL/min | Renal Fractional Oxygen Extraction, % | Renal Oxygen Consumption, mL/min | Renal Oxygen Consumption/Glomerular Filtration Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 7 | 14 ± 0.4 | 44 ± 1 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.024 ± 0.003 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 13.9 ± 2.2 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.23 ± 0.04 |

| CLP | 10 | 11 ± 0.3 | 31 ± 1 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 13.5 ± 2.5 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.40 ± 0.21 |

| Analyses | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.007 | P = 0.14 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.89 | P = 0.006 | P = 0.052 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. CLP, cecal ligation and puncture.

Mitochondrial function and metabolism in s-AKI.

Our in vivo results showed that oxygen utilization by the kidney was not diminished despite reduced oxygen supply, reduced GFR, and filtered load in sepsis. This suggests inefficient oxygen utilization for Na+ reabsorption (more oxygen utilization per net Na+ reabsorbed), given that the majority of renal Qo2 is obligated for tubular reabsorption of filtered Na+ (36). Alternatively, impaired mitochondrial function to support energy demands in the kidney or altered basal metabolism of tubular cells could be invoked to explain this inefficient energy utilization in CLP. We examined various aspects of mitochondrial function and metabolism at the early (4 h) and late (24 h) time points after CLP to better understand the temporal sequence of events in s-AKI.

Tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics in early s-AKI (4 h post-CLP).

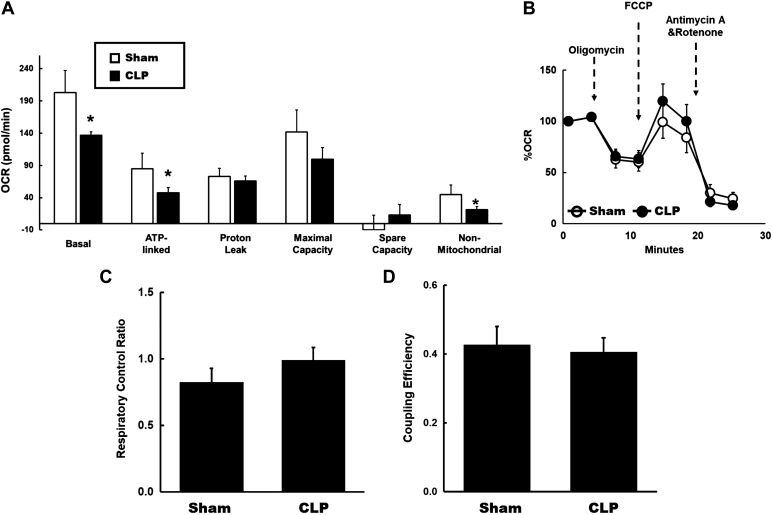

We assessed mitochondrial bioenergetics in fresh isolated proximal tubules from sham and CLP mice by examining the fundamental parameters of mitochondrial respiration. Measurements include basal OCR, ATP-linked OCR, nonmitochondrial OCR, proton leak, maximal capacity, and reserve capacity. Basal OCR reflects the minimum amount of mitochondrial OXPHOS needed to meet the energy demand (8, 14). At 4 h after CLP, we observed that basal OCR was significantly reduced in proximal tubules isolated from CLP kidneys compared with sham kidneys (Fig. 1A). The decrease in OCR in response to oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor) reflects ATP-linked OCR, and the remainder represents proton leak (8, 14). We also observed significantly decreased ATP-linked OCR in tubules from CLP kidneys (Fig. 1A). There was no difference in proton leak, indicating no changes in the coupling of CLP tubular mitochondria compared with the sham group. Maximal OCR is the maximal rate of oxidation in the electron transport chain achieved with the dissipation of the proton gradient by pharmacological uncouplers of OXPHOS such as FCCP, which increase proton permeability across the inner mitochondrial membrane (8, 14). It reflects the maximum activity of electron transport and substrate oxidation achievable by cells. FCCP-induced maximal OCR was not significantly different between groups (Fig. 1B). The difference between basal OCR and maximal OCR is referred to as the spare or reserve bioenergetic capacity, which estimates the maximal capacity for OXPHOS with increased ATP demand or in response to acute stress (8). No differences in reserve capacity was observed between CLP and sham groups. Nonmitochondrial OCR reflects the oxidation by nonmitochondrial enzymes, such as NADPH oxidases, lipoxygenases, and cyclooxygenases (8, 14). Nonmitochondrial OCR was reduced in CLP (Fig. 1A). The respiratory control ratio (RCR) is the ratio of FCCP-induced maximal OCR to ATP-linked OCR. A high RCR implies that the mitochondria have a high capacity for substrate oxidation and a low proton leak (8). RCR was not significantly different between groups (Fig. 1C). Finally, coupling efficiency is the proportion of basal OCR used for ATP synthesis and is determined by the change in basal respiration rate with the addition of oligomycin (8). It is calculated by the ratio of ATP-linked OCR to basal OCR. No differences in coupling efficiency were observed (Fig. 1D). Overall, these data indicate suppression of basal and ATP-linked mitochondrial respiration in tubules at 4 h post-CLP.

Fig. 1.

Tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A: mitochondrial respiration in fresh isolated tubules from sham and CLP mice was measured using the Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer and Cell Mito Stress test kit. Oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) were measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (0.5 μM), FCCP (4 μM), rotenone (1 μM), or antimycin A (1 μM). A: basal respiration, ATP-linked, proton leak, maximal capacity, spare capacity, and nonmitochondrial respiration in fresh isolated tubules from each group. Decreased basal, ATP-linked, and nonmitochondrial OCRs were observed in CLP tubules compared with sham tubules. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 8 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group. B: data are presented after normalization to basal respiration. Each data point represents an OCR measurement. No significant differences were detected. C: respiratory control ratio (RCR), the ratio of FCCP-induced maximal OCR to ATP-linked OCR. There was a small increase in mitochondrial RCR in CLP tubules. D: coupling efficiency, the ratio of ATP-linked OCR to basal OCR. No differences in coupling efficiency was observed.

Mitochondrial content and biogenesis in early s-AKI (4 h post-CLP).

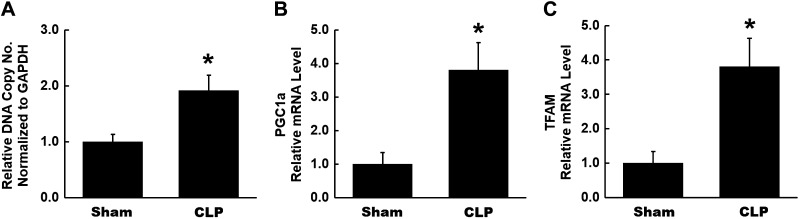

The mtDNA copy number is a commonly used biomarker to assess mitochondrial content and is typically measured as the ratio of mitochondrial genome to nuclear genome using real-time quantitative PCR. We observed a significant increase in mtDNA copy number in kidneys isolated from CLP mice (Fig. 2A). We also assessed mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC)-1α, which is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (56). PGC-1α mRNA expression was significantly increased in CLP kidneys compared with sham kidneys (Fig. 2B). PGC-1α induces gene transcription of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which participates in mitochondrial biogenesis through its interactions with mtDNA (56). mRNA expression of TFAM was also significantly increased in CLP kidneys (Fig. 2C). As TFAM is a downstream transcriptional target of PGC-1α, these results are consistent with increased transcriptional activity of PGC-1α early in CLP kidneys. Overall, these data indicate increased mitochondrial content and biogenesis in the kidney early after CLP, perhaps as an early compensatory response to injury.

Fig. 2.

Mitochondrial content and biogenesis at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A: mtDNA content was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR expressed as the ratio of the mitochondrial genome to the nuclear genome. A significant increase was observed in mtDNA copy number in CLP kidneys. B and C: mRNA levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC)-1α and transcription of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) in kidneys from each group were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. A significant increase was found in both in CLP kidneys. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

Mitochondrial dynamics and morphology in early s-AKI (4 h post-CLP).

Mitochondrial dynamics refer to repetitive cycles of fusion (union) and fission (division), which determine mitochondrial architecture (59). We assessed the expression of various proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics. We observed increased expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins MFN2 and OPA1 in CLP kidneys, whereas MFN1 expression was not different (Fig. 3, A–C). We further examined alterations in mitochondrial morphology by electron microscopy. Representative electron micrographs of mouse kidneys from CLP and sham mice are shown in Fig. 3D. Proximal tubules in sham mice showed well-packed and relatively uniform and fusiform mitochondria (Fig. 3D). In the proximal tubules of CLP kidneys, very subtle features of tubular injury with minimal changes to mitochondrial morphology were seen.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial dynamics and morphology at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A–C: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blots showing expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins mitofusin-1 (Mfn1), mitofusin-2 (Mfn2), and dynamin-like 120-kDa protein (OPA1) in kidneys from each group examined by Western blot analysis and normalized to β-actin. Increased expression of Mfn2 and OPA1 was observed in CLP kidneys. Both bands for OPA1 were analyzed for densitometry. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group. D: representative electron micrographs of mouse kidneys. Well-packed and uniform mitochondria in sham proximal tubules were found. In CLP, proximal tubules with subtle features of tubular injury and minimal changes in mitochondrial morphology were seen. Scale bar = 2 μm for left images and 200 nm for middle and right images. n = 3 per group.

Tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics in late s-AKI (24 h post-CLP).

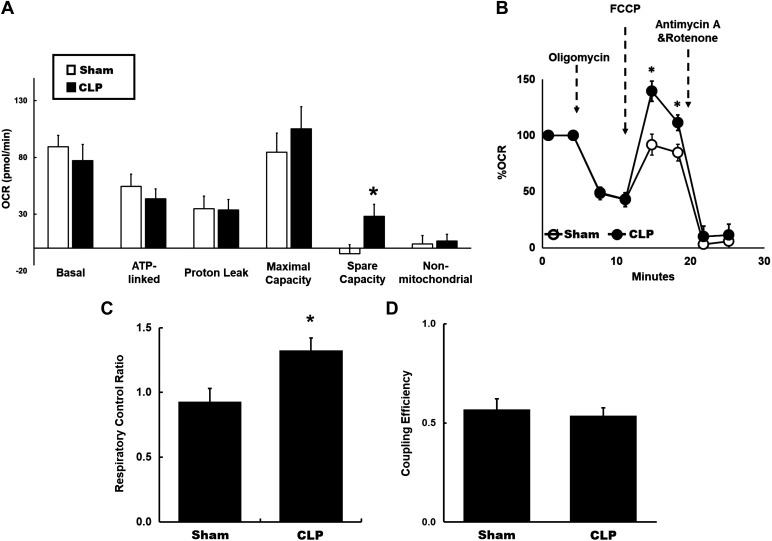

Using protocols similar to the 4-h time point, tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics were evaluated by examining the fundamental parameters of mitochondrial respiration at 24 h after CLP. Basal and ATP-linked OCR in proximal tubules from CLP kidneys were not statistically different from sham tubules (Fig. 4A). No difference in proton leak was seen, indicating no changes in uncoupling of CLP tubular mitochondria (Fig. 4A). We also did not detect any significant changes in nonmitochondrial OCR between the groups (Fig. 4A). However, we found a significant increase in the reserve capacity in tubules from CLP mice compared with sham mice (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, normalized to basal OCR, maximal OCR was significantly higher in CLP tubules (Fig. 4B). We also observed a significant increase in mitochondrial RCR in CLP tubules (Fig. 4C). Coupling efficiency was similar (Fig. 4D), consistent with no differences in proton leak between CLP and sham tubules. These data indicate dynamic changes in tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics with elevated maximal OCR, reserve capacity, and RCR, indicating the high respiratory capacity of tubular mitochondrial at 24 h after CLP.

Fig. 4.

Tubular mitochondrial bioenergetics at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A: mitochondrial respiration in fresh isolated tubules from sham and CLP mice was measured using the Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer and Cell Mito stress test kit as per the protocol described in Fig. 1. Significant increase in spare capacity in CLP tubules was observed compared with sham tubules. No significant differences were found in basal or ATP-linked oxygen consumption rates (OCRs). Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 8 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group. B: data are presented after normalization to basal respiration. Each data point represents an OCR measurement. A significant increase in FCCP-induced maximal OCR was observed in CLP tubules compared with sham tubules. C: respiratory control ratio (RCR), the ratio of FCCP-induced maximal OCR to ATP-linked OCR. A significant increase in mitochondrial RCR in CLP tubules compared with sham tubules was found. D: coupling efficiency, the ratio of ATP-linked OCR to basal OCR. No differences in coupling efficiency were observed.

Mitochondrial content and biogenesis in late s-AKI (24 h post-CLP).

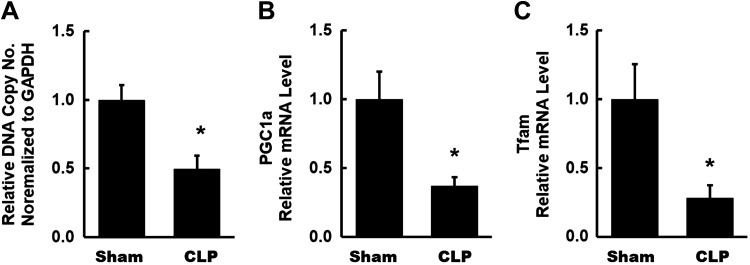

The changes in mitochondrial content and biogenesis at this time point were in sharp contrast to those observed at the early time point. mtDNA copy number was significantly decreased at 24 h after CLP (Fig. 5A). mRNA expression of PGC-1α and its downstream transcriptional target, TFAM, was also significantly reduced in CLP kidneys compared with sham kidneys (Fig. 5, B and C). These results indicate decreased transcriptional activity of PGC-1α and reduced mitochondrial content and biogenesis in CLP kidneys at the 24-h time point.

Fig. 5.

Mitochondrial content and biogenesis at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A: a significant decrease was observed in mtDNA copy number, as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR, in CLP kidneys. B and C: mRNA levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC)-1α and transcription of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) in kidneys from each group were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. A significant decrease in both was observed in CLP kidneys. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

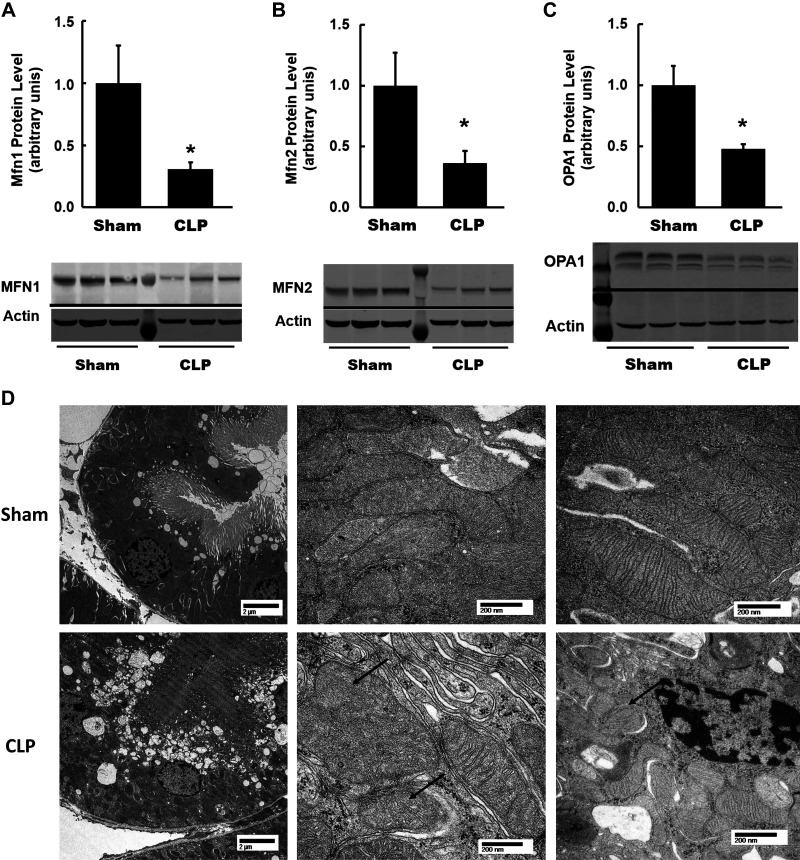

Mitochondrial dynamics and morphology in late s-AKI (24 h post-CLP).

We assessed protein expression of various proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics. Remarkably, protein expression of three important mitochondrial fusion regulatory proteins, MFN1, MFN2, and OPA1, were all significantly reduced in CLP kidneys compared with sham kidneys (Fig. 6, A–C). Representative electron micrographs of mouse kidneys at 24 h after CLP and sham operation are shown in Fig. 6D. Proximal tubules in sham mice showed well-packed and relatively uniform and fusiform mitochondria. In CLP kidneys, proximal tubules showed mild injury (cytoplasmic vacuolization, decreased brush-border density, and widened lumens). Mitochondria appeared less well packed and disorganized. Some appeared swollen with loss of normal cristae architecture. There was increased variability in size and shape, but, overall, mitochondria appeared smaller and more rounded. These data indicate significant changes in renal mitochondrial morphology from an early to a later time point after CLP.

Fig. 6.

Mitochondrial dynamics and morphology at 4 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). A–C: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blots showing expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins mitofusin-1 (Mfn1), mitofusin-2 (Mfn2), and dynamin-like 120-kDa protein (OPA1) in kidneys from each group examined by Western blot and normalized to β-actin. Decreased expression of Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1 was observed in CLP kidneys. Both bands for OPA1 were analyzed for densitometry. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group. D: representative electron micrographs of mouse kidneys. Well-packed and uniform mitochondria in sham proximal tubules were found. In CLP proximal tubules, mild tubular injury (cytoplasmic vacuolization, decreased brush-border density, and widened lumens) and altered mitochondrial morphology with smaller and more rounded mitochondria (arrow, right) were seen. Additionally, swelling, loss of normal cristae architecture (arrows, middle), and increased size variability were seen. Scale bar = 2 μm for the left images and 200 nm for the middle and right images. n = 3 per group.

Renal metabolism in s-AKI.

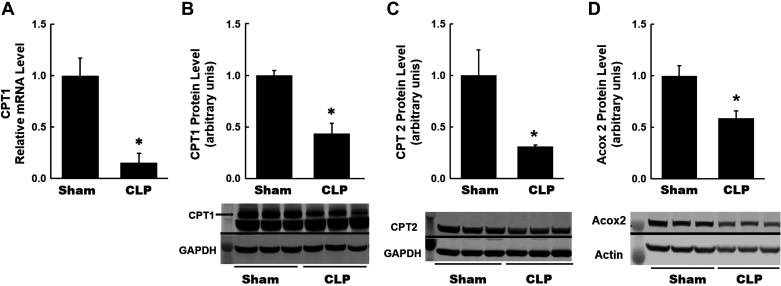

Recently, metabolic reprogramming after kidney injury has been described in AKI and CKD. To examine whether there is evidence for alterations in renal metabolism in s-AKI, we measured expression levels of key metabolic enzymes in the kidneys at 4 and 24 h after CLP. At the 4-h time point, we did not observe significant or consistent changes in the expression of key metabolic enzymes after CLP (data not shown). However, there were significant changes in the expression of various enzymes at the 24-h time point. CPT1 is a rate-limiting enzyme of fatty acid oxidation in the mitochondria (15, 24). It is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane and facilitates the transport of long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs into the mitochondria for fatty acid oxidation. We observed a significant decrease in both mRNA and protein expression of CPT1 in CLP kidneys (Fig. 7, A and B). We also observed a significant decrease in protein expression of CPT2, which is another rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid oxidation (15, 24), in CLP kidneys (Fig. 7C). Expression of ACOX2, which is an enzyme involved in the peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation (37), was also decreased in CLP kidneys (Fig. 7D). These data provide evidence for reprogramming to alternate metabolic pathways in the kidney at 24 h after CLP.

Fig. 7.

Renal metabolism at 24 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP): fatty acid oxidation. A: quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), a rate-limiting enzyme of lipid oxidation, in kidneys from each group. A significant decrease was observed in CLP kidneys. B–D: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blot showing decreased protein expression of CPT1 and other fatty acid oxidation enzymes, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT2) and acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (Acox2), in CLP kidneys normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

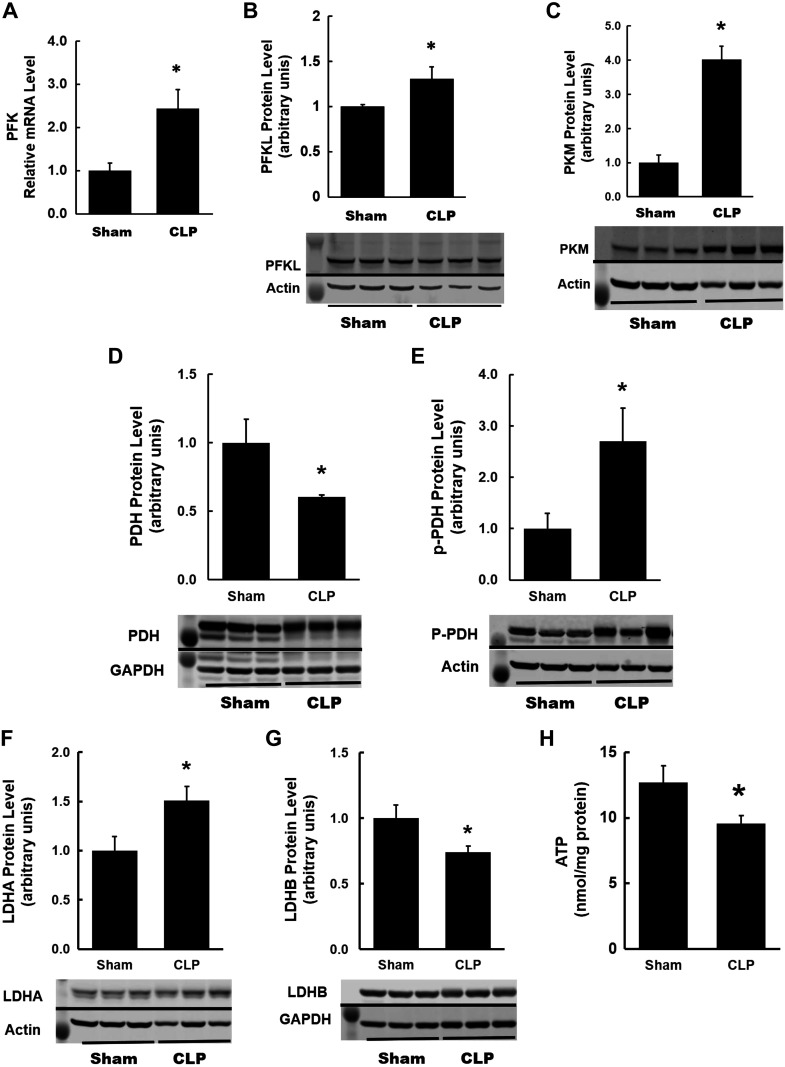

Next, we examined the expression of various glycolytic enzymes to assess the activation of this pathway. Hexokinases catalyze the first step in the glycolytic pathway by converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate. There were no significant changes in the expression of upstream glycolytic enzymes hexokinase 1 and 2 (data not shown). Phosphofructokinase (PFK) is a rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme that irreversibly converts fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and controls the commitment of glucose to glycolysis (21, 22). We observed a significant increase in mRNA and protein expression levels of PFKL (the isoform expressed in the kidney) in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8, A and B). PKM is another rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme, which catalyzes the final step in glycolysis by transferring a phosphoryl group from phosphoenolpyruvate to ADP to form pyruvate and ATP. There was also a significant increase in protein expression of PKM in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8C). We measured protein expression of PDH, which catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to produce acetyl-CoA, which fuels the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle within the mitochondria (47). Interestingly, expression of PDH was significantly reduced in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8D), whereas expression of phospho-PHD (inactive form of PHD) was increased significantly in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8E). We also examined the expression of LDHA and LDHB subunits. In CLP kidneys, we observed an increase in the LDHA subunit (Fig. 8F), which has a higher affinity for pyruvate, thus preferentially converting pyruvate to lactate and NADH to NAD+ (53). The LDHB subunit, which has a higher affinity for lactate, thus preferentially converting lactate to pyruvate and NAD+ to NADH, was significantly decreased in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8G). Finally, we also measured ATP levels by ATP fluorometric assay. Compared with sham kidneys, ATP levels were significantly lower in CLP kidneys (Fig. 8H).

Fig. 8.

Renal metabolism at 24 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP): glycolysis. A: quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of phosphofructokinase (PFK), a rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, in kidneys from each group. A significant increase was observed in CLP kidneys. B and C: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blot showing increased protein expression of PFK, liver type (PFKL; the isoform expressed in the kidney), and pyruvate kinase M (PKM) in CLP kidneys normalized to β-actin. D and E: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blot showing decreased protein expression of total pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and increased expression of phospho-PDH (inactive form of PDH) in CLP kidneys normalized to the internal controls GAPDH and β-actin, respectively. F and G: summary densitometry graph and representative Western blot showing increased protein expression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and decreased protein expression of lactate dehydrogenase B (LDH-B) in CLP kidneys normalized to the internal controls β-actin and GAPDH, respectively. H: quantitation of ATP content in mouse kidneys using the fluorometric assay. Decreased ATP levels were observed in CLP kidneys. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

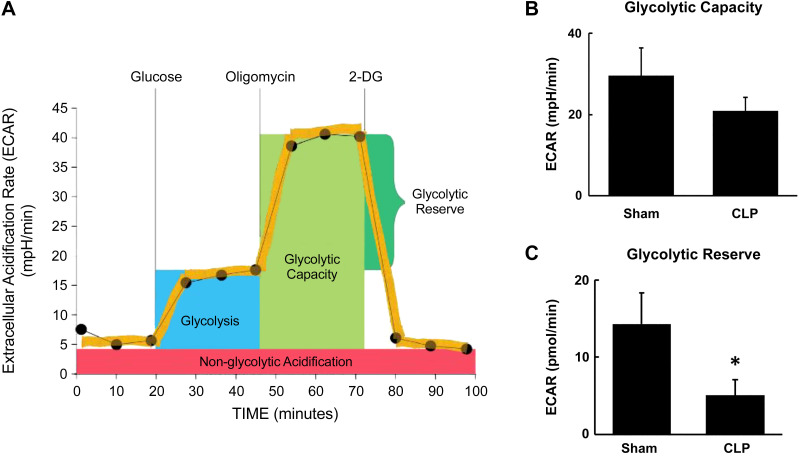

These results indicate activation of the glycolysis pathway and a potential increase in the metabolic fate of pyruvate toward conversion to lactate rather than to acetyl-CoA to enter the mitochondrial TCA cycle. However, the decrease in ATP content suggests that functional glycolysis may be impaired. Hence, we sought to examine functional glycolysis in fresh isolated proximal tubules from CLP kidneys using Agilent Seahorse XF glycolytic assays. Glycolysis involves catabolism of glucose to pyruvate and then conversion of pyruvate to lactate, resulting in the extrusion of protons out of the cells. This extracellular acidification was measured and reported as ECAR using the Agilent Seahorse XF glycolysis stress test kit (14, 18). ECAR was measured at the basal condition followed by injection of glucose, oligomycin, and 2-DG as per the protocol shown in Fig. 9A. ECAR measured without the presence of glucose or pyruvate reflects nonglycolytic acidification from other cellular processes. Glucose is supplied to feed glycolysis, and the difference between ECAR before and after the addition of glucose indicates the basal rate of glycolysis. Oligomycin stops oxidative phosphorylation by inhibiting ATP synthase and drives glycolysis. Maximum ECAR following the addition of oligomycin reflects the glycolytic capacity of cells. The final injection of 2-DG, a glucose analog, which inhibits glycolysis through competitive binding to glucose hexokinase, results in a decrease in ECAR and confirms the glycolytic source of ECAR. The difference between glycolytic capacity and basal glycolysis rate indicates the glycolytic reserve of the cells, which reflects the ability to respond to an energetic demand. We observed a trend for decreased glycolytic capacity (P = 0.06) and significantly lower glycolytic reserve in CLP tubules (Fig. 9, B and C).

Fig. 9.

Glycolytic capacity and reserve at 24 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Glycolysis was measured in fresh isolated tubules from sham and CLP mice using the Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer and Agilent Seahorse XF glycolysis stress test kit. A: Agilent Seahorse XF glycolysis stress test profile (adapted from the Agilent Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Kit User Guide). Acidification of the medium was directly measured and reported as the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) with sequential addition of glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 μM), and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 50 mM) to calculate glycolytic capacity and reserve. B: glycolytic capacity was equal to maximum ECAR after oligomycin. There was a trend for decreased glycolytic capacity in CLP proximal tubules. C: glycolytic reserve was equal to glycolytic capacity − basal glycolysis rate. The glycolytic reserve was significantly reduced in CLP proximal tubules. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

To further confirm the decrease in functional glycolysis observed in these experiments, we also used the newer Seahorse XF glycolytic rate assay, which is more specific for glycolytic acidification. Pyruvate, obtained from the catabolism of glucose, can be either converted to lactate in the cytoplasm or enter the TCA cycle in the mitochondria and be converted to CO2 and water. Glycolysis and mitochondria-derived CO2 are the two main contributors to extracellular acidification and PERs. The contribution of glycolysis to PER (%PER from glycolysis) varies among different cell types. Particularly in cells that are highly oxidative, such as proximal tubules, it is important to subtract the contribution of mitochondria-derived CO2 to extracellular acidification to obtain accurate measurement of glycolysis. The Seahorse XF glycolytic rate assay allows simultaneous measurement of mitochondrial and glycolytic acidification to calculate glycoPER by subtracting mitochondrial CO2-derived PER from total PER (Fig. 10A). GlycoPER is also referred to as basal glycolysis. The mitochondrial electron chain inhibitors rotenone and antimycin A induce a switch to glycolysis in the cells to meet the energy demands, referred to as compensatory glycolysis (Fig. 10A). In the basal condition, ECAR and total PER in tubules were similar between sham and CLP groups (Fig. 10, B and C). Consistent with the above results, glycoPER in CLP tubules was significantly lower than that in sham tubules even under the basal condition (Fig. 10D). Following rotenone and antimycin A administration, compensatory glycolysis rates were significantly lower in CLP tubules (Fig. 10, B–D). The data are shown in Fig. 10, E and F. These data indicate that despite an increase in the expression of several glycolytic enzymes, functional glycolysis was reduced in CLP tubules.

Fig. 10.

Glycolytic rate at 24 h after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Glycolysis was measured in fresh isolated proximal tubules from sham and CLP mice using the Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer and Agilent Seahorse XF glycolysis rate assay. A: Agilent Seahorse XF glycolytic rate assay profile (adapted from Agilent Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay Kit User Guide). The proton efflux rate (PER) was determined at the basal conditions and following rotenone and antimycin A (Rot/AA; 0.5 μM) and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 50 mM) injection. Glycolytic PER (GlycoPER) was determined by the subtraction of mitochondrial acidification from total PER. B–D: kinetic graphs of real-time extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), total PER, and GlycoPER. Under basal conditions, there were similar ECAR and total PER between sham and CLP groups (B and C) but reduced GlycoPER in CLP tubules (D). Following Rot/AA, ECAR, PER, and GlycoPER were significantly reduced in CLP tubules (B–D). E and F: basal glycolysis and compensatory glycolysis were significantly reduced in CLP tubules. Data are presented as means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

DISCUSSION

The impact of AKI in critically ill patients with sepsis is staggering with extremely poor outcomes (1, 2, 4, 49, 52). Advances in therapeutic strategies have been limited to supportive measures, partly due to the complicated and multifaceted pathophysiology-altered hemodynamics and endothelial and epithelial dysfunction (58), which evolves during the course of illness. We focused our investigations to address the major gaps in knowledge with regard to renal oxygenation and mitochondrial function in sepsis.

In sepsis, systemic hemodynamics have been well described (20, 27, 44), but conflicting reports on renal hemodynamics have been published, depending on the model and time point examined after sepsis. Data obtained from animal studies using LPS endotoxin infusion demonstrated a hypodynamic state (12), with renal vasoconstriction and hypoperfusion (44), whereas some studies in large animal models have shown low GFR even with sustained or increased RBF (31, 32), whereas others have shown mixed results (6, 25). Low RBF has been reported in aged CLP mice (55) and after LPS administration (51). We also found RBF to be significantly lower in CLP, whereas renal plasma flow and filtration fraction were not significantly different from the sham group. Human data are limited, but a recent study has demonstrated reduced RBF in established s-AKI, albeit with significant intragroup variability (40). Overall, the data collectively suggest that a reduction in RBF is not essential to the pathogenesis of s-AKI. These observations also reflect clinical experience, where aggressive fluid resuscitation lowers the risk of AKI but does not prevent it, and the failure of vasodilators in septic AKI (16).

There are distinctive features of renal oxygenation that make the kidney more susceptible to oxygen demand-supply mismatch and hypoxia. Renal oxygen consumption is driven by tubular transport, which is determined by the filtered solute load and GFR. In aged mice with CLP, tissue hypoxia at 4 and 6 h was demonstrated (55), although other parameters of renal oxygenation in CLP mice have not been reported before. Our findings provide important insights into the changes in renal oxygenation after sepsis. We observed decreased renal Do2 but unchanged renal oxygen extraction in CLP mice despite reduced GFR and reabsorptive load. Interestingly, in patients with AKI after cardiac surgery, an increase in renal oxygen extraction was observed compared with postcardiac surgery patients without AKI (41). These results suggest inefficient oxygen utilization for Na+ reabsorption, increased oxygen utilization for nontransport processes, and/or impaired underlying mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity in AKI.

Recently, the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in AKI has received significant attention. In ischemic AKI, decreased mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial swelling, along with a reduction in electron transport chain proteins and an increase in mitochondrial NADH, have been reported (10, 17, 23). The functional activity of mitochondria in AKI has been less studied, especially in s-AKI. Tran et al. (51) demonstrated reduced cytochrome c staining after LPS and CLP. Patil et al. (39) showed decreased activity of mitochondrial complexes I, II, and III and low ATP levels after CLP in aged mice. We examined mitochondrial function ex vivo in fresh isolated proximal tubules. This approach offers the advantage over existing methodologies, which use isolated mitochondria, of enhanced physiological relevance by making these measurements in intact cells with an undisturbed cellular environment and interactions of mitochondria with other cellular organelles (8).

Our findings demonstrate dynamic changes in tubular mitochondrial function and bioenergetics, which evolve over the course of sepsis. In early sepsis, we observed a decrease in basal and ATP-linked mitochondrial OCR, along with an increase in markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and content. Basal respiration is mainly controlled by ATP turnover and responds to ATP demand (8). The suppression in basal and ATP-linked respiration may be due to low ATP demand or an adaptive mechanism to allow for cell survival, a form of cellular hibernation in the septic milieu. This would be consistent with the lack of tubular cell death observed in experimental and clinical sepsis (26, 30, 48). The increase in mitochondrial biogenesis regulators, mitochondrial content, and fusion proteins at the early time point is also consistent with an early compensatory response.

At the 24-h time point, there was decreased mitochondrial content and biogenesis in CLP kidneys; however, CLP tubules demonstrated increased FCCP-stimulated OCR, indicating that mitochondria were using less than the maximal rate of respiration supported by substrates in the cells. CLP tubules also showed an increase in the spare or reserve bioenergetic capacity, which estimates the ability of cells to respond to increased energy demand or to acute stress (8). Coupling efficiency and RCR are thought to be excellent markers of mitochondrial dysfunction, as they are sensitive to changes in any component of mitochondrial OXPHOS (8). No changes in coupling efficiency were evident in CLP tubular mitochondria. Remarkably, RCR was increased in CLP tubular mitochondria at this time point, which indicates a high capacity for substrate oxidation and respiration with low proton leak. Some caveats should be considered while interpreting the OCR data. The process of isolation of tubules may introduce some confounding, especially in CLP mice, as the injured tubules may not survive the isolation process, and the data may only reflect the function of more robust tubules. Another caveat to consider is that OCR is normalized to cellular protein content and does not capture changes in mitochondrial content and density within the cell, which can affect cellular respiration. Hence, it is important to interpret the observed changes (or lack thereof) in respiration in the context of changes in mitochondrial content within the cell. Nonetheless, our results still indicate that even with decreased mitochondrial content, the residual tubular mitochondria in CLP display high respiratory capacity. However, despite the high respiratory capacity, ATP levels were lower in CLP kidneys. This could indicate a low tubular ATP demand or decreased ATP synthesis efficiency in tubular mitochondria, which could result from altered mitochondrial morphology and dynamics.

Mitochondrial morphology (or dynamics) strongly influences mitochondrial metabolism and survival and is regulated by fission and fusion proteins (59). Recent studies have also described the role of mitochondrial dynamics in bioenergetic adaptation to metabolic demands of the cell. Increased ATP synthesis capacity was shown to be dependent on decreased fission and increased fusion (19). Lack of Mfn2 and fragmented mitochondria were associated with high respiration but decreased ATP synthesis efficiency (3, 34, 45). We found decreased expression of all three fusion proteins at the 24-h time point, corresponding with rounded and fragmented mitochondria using electron microscopy. These changes in mitochondrial morphology could impair bioenergetic efficiency and capacity of tubular mitochondria in septic kidneys but need to be examined in further detail.

Proximal tubules have limited capacity to metabolize glucose (21, 22). However, in most cells, including parts of the kidney (medulla), glucose is used as fuel. Under aerobic/normoxic conditions, it is catabolized to pyruvate into the cytosol, which enters the TCA cycle within the mitochondria. Under anaerobic/hypoxic conditions, pyruvate is converted to lactate in the cytosol. Conversion of pyruvate to lactate even under aerobic conditions is referred to as the “Warburg” effect or aerobic glycolysis (54). This metabolic reprogramming has been described in tumor cells and proliferating cells (35). Glycolysis is an inefficient pathway to generate ATP per unit of glucose but better supports macromolecular synthesis (nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids). After injury, tubular metabolism may be adapted to facilitate the biomass synthesis needed for proliferation and repair, which is better supported by glycolysis. Interestingly, while we did not observe any changes in the expression of upstream glycolytic enzymes, such as hexokinase 1 and 2, other key and rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes involved in later stages of glycolysis were increased. These included PFK, which catalyzes the irreversible commitment of glucose to glycolysis, and pyruvate kinase, which catalyzes the final step of glycolysis to form pyruvate, as well as other enzymes, which preferentially direct the metabolic fate of pyruvate toward conversion to lactate rather than to acetyl-CoA to enter the TCA cycle within the mitochondria. However, when we measured functional glycolysis in proximal tubules, we observed significant reductions in various parameters of compensatory glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, and reserve in CLP. Perhaps, the lack of upregulation of upstream glycolytic enzymes, such as hexokinase, limits the ability of the tubular cells to initiate the glycolytic pathway. Another possibility is that glucose entry and uptake into the tubular cells may be limited, perhaps due to altered expression of Na+-glucose cotransporters and facilitative glucose transporters. An increase in glycolytic enzymes in proximal tubules has been observed during hypoxic/ischemic stress (13, 29); however, functional glycolysis has not been examined in various injury models. This decrease in functional glycolysis could be elemental in impairing the ability of proximal tubular cells to withstand injury and play a detrimental role in their repair and recovery after injury. Detailed assessment of factors underlying the diminished functional glycolysis and their impact on tubular function need to be further examined. We also observed a significant reduction in key enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation, which is the preferential metabolic pathway in proximal tubules. Metabolic reprogramming affecting fatty acid metabolism in kidney disease has also been recently described in diabetic kidneys (43) and in transgenic models of advanced kidney fibrosis (28).

In summary, our findings demonstrate significant changes in renal oxygenation, mitochondrial function, and metabolism in AKI during sepsis. We provide detailed assessment of the evolution of changes in tubular mitochondrial respiration, biogenesis, and morphology and metabolic reprogramming along the course of sepsis. Whether the metabolic reprogramming is an early, adaptive response and how it impacts the progression of injury and recovery from AKI remain to be further studied.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01DK107852 (to P. Singh), VA Merit Award BX002175 (to P. Singh), and resources from the University of Alabama at Birmingham-University of California-San Diego O’Brien Center (NIH Grant P30DK079337).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.S. conceived and designed research; Y.L., N.N., H.P., R.T., and J.E.Z. performed experiments; Y.L., N.N., H.P., R.T., J.E.Z., and P.S. analyzed data; Y.L., N.N., J.E.Z., and P.S. interpreted results of experiments; Y.L., N.N., J.E.Z., and P.S. prepared figures; Y.L. and P.S. drafted manuscript; Y.L., N.N., R.T., J.E.Z., and P.S. edited and revised manuscript; P.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Some of the results have been presented as abstracts at American Society of Nephrology and Experimental Biology meetings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alobaidi R, Basu RK, Goldstein SL, Bagshaw SM. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 35: 2–11, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29: 1303–1310, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach D, Naon D, Pich S, Soriano FX, Vega N, Rieusset J, Laville M, Guillet C, Boirie Y, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Manco M, Calvani M, Castagneto M, Palacín M, Mingrone G, Zierath JR, Vidal H, Zorzano A. Expression of Mfn2, the Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A gene, in human skeletal muscle: effects of type 2 diabetes, obesity, weight loss, and the regulatory role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6. Diabetes 54: 2685–2693, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagshaw SM, George C, Dinu I, Bellomo R. A multi-centre evaluation of the RIFLE criteria for early acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1203–1210, 2008. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeson CC, Beeson GC, Schnellmann RG. A high-throughput respirometric assay for mitochondrial biogenesis and toxicity. Anal Biochem 404: 75–81, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benes J, Chvojka J, Sykora R, Radej J, Krouzecky A, Novak I, Matejovic M. Searching for mechanisms that matter in early septic acute kidney injury: an experimental study. Crit Care 15: R256, 2011. doi: 10.1186/cc10517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonventre JV, Basile D, Liu KD, McKay D, Molitoris BA, Nath KA, Nickolas TL, Okusa MD, Palevsky PM, Schnellmann R, Rys-Sikora K, Kimmel PL, Star RA; Kidney Research National Dialogue (KRND) . AKI: a path forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1606–1608, 2013. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06040613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J 435: 297–312, 2011. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breggia AC, Himmelfarb J. Primary mouse renal tubular epithelial cells have variable injury tolerance to ischemic and chemical mediators of oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 1: 33–38, 2008. doi: 10.4161/oxim.1.1.6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest 119: 1275–1285, 2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bullen A, Liu ZZ, Hepokoski M, Li Y, Singh P. Renal oxygenation and hemodynamics in kidney injury. Nephron 137: 260–263, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000477830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deitch EA. Animal models of sepsis and shock: a review and lessons learned. Shock 9: 1–11, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199801000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickman KG, Mandel LJ. Differential effects of respiratory inhibitors on glycolysis in proximal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 258: F1608–F1615, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.6.F1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Divakaruni AS, Paradyse A, Ferrick DA, Murphy AN, Jastroch M. Analysis and interpretation of microplate-based oxygen consumption and pH data. Methods Enzymol 547: 309–354, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801415-8.00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillmore N, Lopaschuk GD. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an approach to treat heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833: 857–865, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedrich JO, Adhikari N, Herridge MS, Beyene J. Meta-analysis: low-dose dopamine increases urine output but does not prevent renal dysfunction or death. Ann Intern Med 142: 510–524, 2005. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funk JA, Schnellmann RG. Persistent disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis after acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F853–F864, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00035.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Nichols AG, Macintyre AN, Inoue M, Ilkayeva O, Winter PS, Liu X, Priyadharshini B, Slawinska ME, Haeberli L, Huck C, Turka LA, Wood KC, Hale LP, Smith PA, Schneider MA, MacIver NJ, Locasale JW, Newgard CB, Shinohara ML, Rathmell JC. Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J Clin Invest 125: 194–207, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI76012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes LC, Di Benedetto G, Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol 13: 589–598, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncb2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graetz TJ, Hotchkiss RS. Sepsis: Preventing organ failure in sepsis—the search continues. Nat Rev Nephrol 13: 5–6, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guder WG, Ross BD. Enzyme distribution along the nephron. Kidney Int 26: 101–111, 1984. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guder WG, Wagner S, Wirthensohn G. Metabolic fuels along the nephron: pathways and intracellular mechanisms of interaction. Kidney Int 29: 41–45, 1986. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall AM, Rhodes GJ, Sandoval RM, Corridon PR, Molitoris BA. In vivo multiphoton imaging of mitochondrial structure and function during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 83: 72–83, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han SH, Malaga-Dieguez L, Chinga F, Kang HM, Tao J, Reidy K, Susztak K. Deletion of Lkb1 in renal tubular epithelial cells leads to CKD by altering metabolism. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 439–453, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014121181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He X, Su F, Velissaris D, Salgado DR, de Souza Barros D, Lorent S, Taccone FS, Vincent JL, De Backer D. Administration of tetrahydrobiopterin improves the microcirculation and outcome in an ovine model of septic shock. Crit Care Med 40: 2833–2840, 2012. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b88ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 348: 138–150, 2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2: 16045, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang HM, Ahn SH, Choi P, Ko YA, Han SH, Chinga F, Park AS, Tao J, Sharma K, Pullman J, Bottinger EP, Goldberg IJ, Susztak K. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med 21: 37–46, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan R, Geng H, Singha PK, Saikumar P, Bottinger EP, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA. Mitochondrial pathology and glycolytic shift during proximal tubule atrophy after ischemic AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3356–3367, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langenberg C, Bagshaw SM, May CN, Bellomo R. The histopathology of septic acute kidney injury: a systematic review. Crit Care 12: R38, 2008. doi: 10.1186/cc6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langenberg C, Bellomo R, May C, Wan L, Egi M, Morgera S. Renal blood flow in sepsis. Crit Care 9: R363–R374, 2005. doi: 10.1186/cc3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langenberg C, Wan L, Egi M, May CN, Bellomo R. Renal blood flow in experimental septic acute renal failure. Kidney Int 69: 1996–2002, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Satriano J, Thomas JL, Miyamoto S, Sharma K, Pastor-Soler NM, Hallows KR, Singh P. Interactions between HIF-1α and AMPK in the regulation of cellular hypoxia adaptation in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F414–F428, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00463.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liesa M, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of nutrient utilization and energy expenditure. Cell Metab 17: 491–506, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27: 441–464, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandel LJ. Primary active sodium transport, oxygen consumption, and ATP: coupling and regulation. Kidney Int 29: 3–9, 1986. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno-Fernandez ME, Giles DA, Stankiewicz TE, Sheridan R, Karns R, Cappelletti M, Lampe K, Mukherjee R, Sina C, Sallese A, Bridges JP, Hogan SP, Aronow BJ, Hoebe K, Divanovic S. Peroxisomal β-oxidation regulates whole body metabolism, inflammatory vigor, and pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. JCI Insight 3: e93626, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nourbakhsh N, Singh P. Role of renal oxygenation and mitochondrial function in the pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract 127: 149–152, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000363545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patil NK, Parajuli N, MacMillan-Crow LA, Mayeux PR. Inactivation of renal mitochondrial respiratory complexes and manganese superoxide dismutase during sepsis: mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitigates injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F734–F743, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00643.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, Bellomo R. Measurement of renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging during septic acute kidney injury: a pilot investigation. Crit Care Med 40: 1768–1776, 2012. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246bd85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Redfors B, Bragadottir G, Sellgren J, Swärd K, Ricksten SE. Acute renal failure is not an “acute renal success”−a clinical study on the renal oxygen supply/demand relationship in acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 38: 1695–1701, 2010. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e61911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc 4: 31–36, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sas KM, Kayampilly P, Byun J, Nair V, Hinder LM, Hur J, Zhang H, Lin C, Qi NR, Michailidis G, Groop PH, Nelson RG, Darshi M, Sharma K, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Pop-Busui R, Weinberg JM, Soleimanpour SA, Abcouwer SF, Gardner TW, Burant CF, Feldman EL, Kretzler M, Brosius FC III, Pennathur S. Tissue-specific metabolic reprogramming drives nutrient flux in diabetic complications. JCI Insight 1: e86976, 2016. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schrier RW, Wang W. Acute renal failure and sepsis. N Engl J Med 351: 159–169, 2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sebastián D, Hernández-Alvarez MI, Segalés J, Sorianello E, Muñoz JP, Sala D, Waget A, Liesa M, Paz JC, Gopalacharyulu P, Orešič M, Pich S, Burcelin R, Palacín M, Zorzano A. Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) links mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum function with insulin signaling and is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 5523–5528, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108220109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh P, Ricksten SE, Bragadottir G, Redfors B, Nordquist L. Renal oxygenation and haemodynamics in acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 40: 138–147, 2013. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stacpoole PW. Therapeutic targeting of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex/pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDC/PDK) axis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 109: djx071, 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takasu O, Gaut JP, Watanabe E, To K, Fagley RE, Sato B, Jarman S, Efimov IR, Janks DL, Srivastava A, Bhayani SB, Drewry A, Swanson PE, Hotchkiss RS. Mechanisms of cardiac and renal dysfunction in patients dying of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 509–517, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1983OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thakar CV, Christianson A, Freyberg R, Almenoff P, Render ML. Incidence and outcomes of acute kidney injury in intensive care units: a Veterans Administration study. Crit Care Med 37: 2552–2558, 2009. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a5906f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas JL, Pham H, Li Y, Hall E, Perkins GA, Ali SS, Patel HH, Singh P. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α activation improves renal oxygenation and mitochondrial function in early chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F282–F290, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00579.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran M, Tam D, Bardia A, Bhasin M, Rowe GC, Kher A, Zsengeller ZK, Akhavan-Sharif MR, Khankin EV, Saintgeniez M, David S, Burstein D, Karumanchi SA, Stillman IE, Arany Z, Parikh SM. PGC-1α promotes recovery after acute kidney injury during systemic inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 4003–4014, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI58662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators . Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 294: 813–818, 2005. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valvona CJ, Fillmore HL, Nunn PB, Pilkington GJ. The regulation and function of lactate dehydrogenase A: therapeutic potential in brain tumor. Brain Pathol 26: 3–17, 2016. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324: 1029–1033, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Z, Holthoff JH, Seely KA, Pathak E, Spencer HJ III, Gokden N, Mayeux PR. Development of oxidative stress in the peritubular capillary microenvironment mediates sepsis-induced renal microcirculatory failure and acute kidney injury. Am J Pathol 180: 505–516, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinberg JM. Mitochondrial biogenesis in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 431–436, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitaker RM, Wills LP, Stallons LJ, Schnellmann RG. cGMP-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis and promote recovery from acute kidney injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347: 626–634, 2013. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zarjou A, Agarwal A. Sepsis and acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 999–1006, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhan M, Brooks C, Liu F, Sun L, Dong Z. Mitochondrial dynamics: regulatory mechanisms and emerging role in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int 83: 568–581, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]