Abstract

Electronic cigarettes (ECs) and tobacco cigarettes (TCs) both release nicotine, a sympathomimetic drug. We hypothesized that baseline heart rate variability (HRV) and hemodynamics would be similar in chronic EC and TC smokers and that after acute EC use, changes in HRV and hemodynamics would be attributable to nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol. In 100 smokers, including 58 chronic EC users and 42 TC smokers, baseline HRV and hemodynamics [blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR)] were compared. To isolate the acute effects of nicotine vs. non-nicotine constituents in EC aerosol, we compared changes in HRV, BP, and HR in EC users after using an EC with nicotine (ECN), EC without nicotine (EC0), nicotine inhaler (NI), or sham vaping (control). Outcomes were also compared with TC smokers after smoking one TC. Baseline HRV and hemodynamics were not different in chronic EC users and TC smokers. In EC users, BP and HR, but not HRV outcomes, increased only after using the ECN, consistent with a nicotine effect on BP and HR. Similarly, in TC smokers, BP and HR but not HRV outcomes increased after smoking one TC. Despite a similar increase in nicotine, the hemodynamic increases were significantly greater after TC smokers smoked one TC compared with the increases after EC users used the ECN. In conclusion, chronic EC and TC smokers exhibit a similar pattern of baseline HRV. Acute increases in BP and HR in EC users are attributable to nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol. The greater acute pressor effects after TC compared with ECN may be attributable to non-nicotine, combusted constituents in TC smoke.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Chronic electronic cigarette (EC) users and tobacco cigarette (TC) smokers exhibit a similar level of sympathetic nerve activity as estimated by heart rate variability. Acute increases in blood pressure (BP) and heart rate in EC users are attribute to nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol. Acute TC smoking increased BP significantly more than acute EC use, despite similar increases in plasma nicotine, suggestive of additional adverse vascular effects attributable to combusted, non-nicotine constituents in TC smoke.

Keywords: blood pressure, electronic cigarettes, heart rate variability, nicotine, tobacco cigarettes

INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarettes (ECs), used by an estimated 9 million adults and 3.6 million children in the United States in 2018, are now firmly established as part of the tobacco continuum (7, 42). However, it remains uncertain where on this continuum of harm they belong (17). Accumulating evidence supports the concept that levels of harmful, even carcinogenic, constituents are far lower in EC users compared with tobacco cigarette (TC) smokers, with one exception, nicotine (37). Nicotine levels in chronic EC users and TC smokers are comparable (37). Nicotine, the addictive constituent in cigarettes, is a sympathomimetic drug, and increased sympathetic activity is associated with increased cardiac risk in many populations. Nicotine has also been shown to be proatherogenic in animal models (20, 35). Thus, the long-term health effects, specifically cardiovascular health effects, of chronic EC use remain uncertain.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a biomarker that reflects the relative balance of cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity (23). A pattern of HRV indicative of increased sympathetic-vagal balance, termed “sympathetic predominance” is associated with increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart disease and even those without heart disease (5, 8, 16, 18, 21, 26, 40). Furthermore, the risk is graded. Those with the greatest abnormalities in sympathetic-vagal balance have the greatest cardiovascular risk (16, 40). Importantly, abnormal HRV characterized by elevated sympathetic and reduced vagal cardiac nerve activity has been reported in chronic TC smokers (1, 15, 22). We recently reported that chronic EC users compared with healthy controls also had increased cardiac sympathetic nerve activity as measured by HRV (28). It is unknown whether chronic EC users have lower resting levels of sympathetic activity compared with chronic TC smokers, a finding that may support the inclusion of ECs as part of a harm reduction strategy, or whether cardiac sympathetic activity is similar in EC users and chronic TC smokers, potentially conferring comparable cardiovascular risks.

We also recently reported that in nicotine-naïve nonusers, using an EC with nicotine, but not without nicotine, acutely triggered an increase in cardiac sympathetic activity, consistent with notion that nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol, underlies this sympathetic activation. Furthermore, heart rate, but not blood pressure, significantly increased after using the EC, and this too was attributable to nicotine (27). Acute increases in sympathetic activity have been reported to trigger adverse cardiac events including arrhythmias, ischemia, cardiomyopathy, and even myocardial infarction and sudden death (13, 19, 24, 25, 30, 34). It remains unknown whether chronic EC users, who may have developed tolerance to acute nicotinic effects (10), would also exhibit increased cardiac sympathetic activation and hemodynamics after acutely using an EC, and, if so, whether this increase would be attributable to nicotine or non-nicotine constituents in the aerosol.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that baseline HRV and hemodynamics would be similar in chronic EC users and TC smokers. Furthermore, in EC users, we hypothesized that after EC use, changes in HRV and hemodynamics would be attributable to nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol. Finally, we hypothesized that these HRV and hemodynamic changes would not be different from those in TC smokers after comparable nicotine exposure after acute TC smoking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The study population consisted of healthy male and female subjects between the ages 21 and 45 yr, who were 1) chronic (≥12 mo) EC users who did not smoke TCs (no dual users), or 2) chronic (≥12 mo) TC smokers. To be eligible for inclusion in this study, subjects could have no known health problems, including asthma, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia and could not be taking prescription medications regularly (oral contraceptives were allowed). They could not be obese [≤30 kg/m2 body mass index (BMI)], could not be pregnant (verified each visit by a urine pregnancy test), and could not be competitive athletes. Only subjects who drank less than or equal to two alcoholic drinks per day and did not use illicit drugs (determined through screening questionnaire and confirmed at each visit with a urine toxicology test) were eligible. Since HRV reportedly returns back toward normal within days to weeks following TC smoking cessation, former TC smokers were eligible for the study if they had quit smoking at least 1 yr before the study (14, 39). End-tidal CO was measured in EC users each visit to detect those who were surreptitiously smoking TCs. A urine toxicology test was performed at the beginning of each visit to exclude surreptitious marijuana use. On the day of the written informed consent, before the day of the first experimental session, all subjects were familiarized and acclimated to the experimental set-up. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Acute EC use.

In this open label randomized crossover study, chronic EC users participated in up to four 30-min acute exposure sessions in random order separated by 4 wk: 1) sham vaping, a control session consisting of puffing on an empty EC, 2) EC with nicotine (ECN), 3) EC without nicotine (EC0), and 4) nicotine inhaler (NI), a “clean” source of nicotine, without flavorings or solvents.

Acute tobacco cigarette smoking.

Chronic TC smokers participated in up to two acute smoking sessions in random order separated by 4 wk: 1) sham smoking, a control session consisting of puffing on an empty straw, and 2) smoking 1 TC (own brand).

Smoking Topography

Electronic cigarette and nicotine inhaler.

A rigorous, reproducible, and uniform vaping protocol was utilized to provide a similar EC “dose” (as estimated by nicotine level) as smoking one tobacco cigarette, as previously described (27). Briefly, participants took a 3-s puff every 30 s from the EC for up to 30 min (60 puffs). According to the package insert and company literature, utilizing this same topography, the nicotine inhaler (NI) was expected to achieve very similar plasma nicotine levels seen with our second-generation EC device (27).

Tobacco cigarette.

Subjects puffed on an empty straw or smoked one TC in 7 min, a typical time interval to smoke one TC.

EC Device

In our earliest studies (2015), subjects (n = 17) used Greensmoke cigalike EC device (the highest rated EC brand in the United States sold online at the time of the study design) with tobacco-flavored liquid and the solvents vegetable glycerin/propylene glycol (VG/PG) with 1) 1.2% nicotine, and 2) 0% nicotine. In 2016, subjects (n = 18) used a more‐efficient nicotine delivery system, the second‐generation pen‐like device (1.0 Ω, eGo‐One by Joyetech, Irvine, CA), strawberry-flavored VG/PG liquid with 1) 1.2% nicotine, 2) 0% nicotine, or 3) empty (control). In 2019, subjects used the Juul (n = 14), mint-flavored pods, 1) with 5% nicotine, and 2) without nicotine (Cyclone).

Nicotine and Cotinine Plasma Levels

Before and after EC or TC exposures, blood was drawn according to laboratory specifications and sent to the UCLA Clinical Laboratories for nicotine (half-life 1–2 h) and cotinine (half-life 16–20 h) levels. The assay for plasma nicotine and cotinine was run by the commercial laboratory Quest Laboratories with a limit of quantitation of 2 ng/mL for both plasma nicotine and cotinine

Heart Rate Variability during Ad Libitum Breathing and during Controlled Breathing (Vagal Stimulus)

The ECG was recorded for 5 min during quiet rest during ad libitum breathing and for 5 min during controlled breathing at a rate of 12 breaths per minute, a known stimulus for vagal tone (1, 9). During controlled breathing, participants were cued visually by watching the secondhand on a large clock to inhale every 5 s. Five-minute ECG recordings were analyzed using standard commercial software (LabChart7, Ad Instruments) in the frequency domain according to published guidelines (23). Three main spectral components were distinguished: high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.4 Hz), low frequency (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz), and very low frequency (VLF, 0.003–0.04 Hz). As recommended in the published guidelines, HRV is presented in normalized units to correct for differences in total power between the groups. Time domain analysis was not applied to these recordings, since a minimum of 20-min recordings, and preferentially, 24-h recordings, are recommended for this methodology (23).

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), mean BP (MBP), and heart rate (HR) were measured after a 10-min rest period in the supine position at baseline and after a 5-min rest period following each exposure, with a noninvasive BP monitor (Casmed 740, Avante Health Solutions) according to American Heart Association guidelines (29). MBP was calculated using the formula (SBP + 2 × DBP)/3. The same approach to BP measurement was followed in EC users and TC smokers pre-/postexposure, including control (sham smoking).

Experimental Session

To avoid the potential influence of circadian rhythm on autonomic tone, subjects were studied mid-day (usually between 10 AM-2 PM. After abstaining from smoking, caffeine, and exercise for at least 12 h, fasting participants were placed in a supine position in a quiet, temperature-controlled (21 °C) room in the Human Physiology Laboratory located in the UCLA Clinical and Translational Research Center. No cell phones or digital stimuli were allowed, and during data acquisition, talking was minimized. The participant was instrumented, blood was drawn, and after a 10-min rest period, blood pressure and heart rate were measured, and the ECG was recorded for 10 min. The participant then underwent an assigned exposure: ECN, EC0, NI, or sham-vaping control for EC users and TC or sham-smoking control for TC smokers. Immediately after vaping or smoking, the participant was repositioned, and after a 5-min rest period, blood pressure and heart rate were measured. Then the ECG was recorded for 10 min, blood was drawn, and the study was concluded.

Statistical Analysis

The three primary outcomes in the parallel study were 1) high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.4 Hz), 2) low frequency (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz), and the 3) LF-to-HF ratio in abstinent participants during ad libitum breathing, and the change in these outcomes following each exposure. Secondary outcomes were these HRV variables during controlled respirations (12 breaths per minute). Additional secondary outcomes included resting hemodynamics, including the SBP, DBP, MBP, and HR, and the change in these outcomes with each acute exposure.

Data from cigalike, pen-like, and Juul devices were analyzed as a single EC group, distinguished only by liquid with and without nicotine. Mean postexposure minus baseline differences were compared across ECN, EC0, NI, and control using a crossover repeated measure (mixed) ANOVA model adjusting for session and order. Normal quantile plots (not shown) were examined, and the Shapiro-Wilk statistic was computed to confirm that the model residual errors followed the normal distribution on the appropriate original or log scale. Means ± SE for baseline to postexposure changes were adjusted by session and order effects.

Associations between two continuous variables were assessed using the nonparametric Spearman correlation (rs) since the relation was monotone but not necessarily linear. Differences or associations were considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05.

Sample size calculation.

Sample size was based on end points of HRV. Since there were no data regarding the acute effects of EC on HRV components at the time of the study design (2015), we used the reported pooled SD of acute oral administration of nicotine (nicotine lozenge) on HRV in healthy young nonsmokers (38). Using the reported SD of 0.3 to 2 for HF, LF, and LF-to-HF ratio for acute exposure to 4 mg oral nicotine, and assuming similar SDs with EC exposures, we calculated that a sample size of only eight subjects was required for 80% power using a two-sided alpha = 0.05. Our final analysis included at least 34 subjects per group.

RESULTS

Study Population

Of 106 participants, 6 were excluded (3 urine positive for marijuana, 2 carbon monoxide >10 ppm consistent with surreptitious TC use, and 1 illness) leaving 100 participants, including 58 chronic EC users and 42 chronic TC smokers who were enrolled in this study. Baseline demographics of the 58 chronic EC users and the 42 chronic TC smokers are displayed in Table 1. The groups had similar demographics including age, sex, race, and BMI. Plasma cotinine level tended to be higher in the TC smokers, indicative of greater smoking burden, although this did not reach statistical significance. Seven EC users and 9 TC smokers did not completely abstain from smoking before the study, as indicated by detectable plasma nicotine levels ≥3 ng/mL. An analysis was performed without these participants, and results were unchanged (data not shown).

Table 1.

Study population

| EC Users | TC Smokers | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 58 | 42 | |

| Mean age, yr | 27.7 ± 5.3 | 26.9 ± 5.6 | 0.31 |

| Sex, men/women | 39/19 | 27/15 | 0.87 |

| Race | 0.57 | ||

| African American | 2 | 4 | |

| Asian | 14 | 13 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 3 | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 36 | 22 | |

| Other/unknown | 1 | 0 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.6 ± 3.7 | 24.2 ± 2.9 | 0.71 |

| Plasma cotinine, ng/mL | 28.0 (0–82) | 72.3 (4.8–106) | 0.07 |

| Former TC smoker | 34 (59%) | NA |

Values are means ± SD for mean age and body mass index and median (Q1–Q3) for plasma cotinine. EC, electronic cigarette; TC, tobacco cigarette; NA, not applicable.

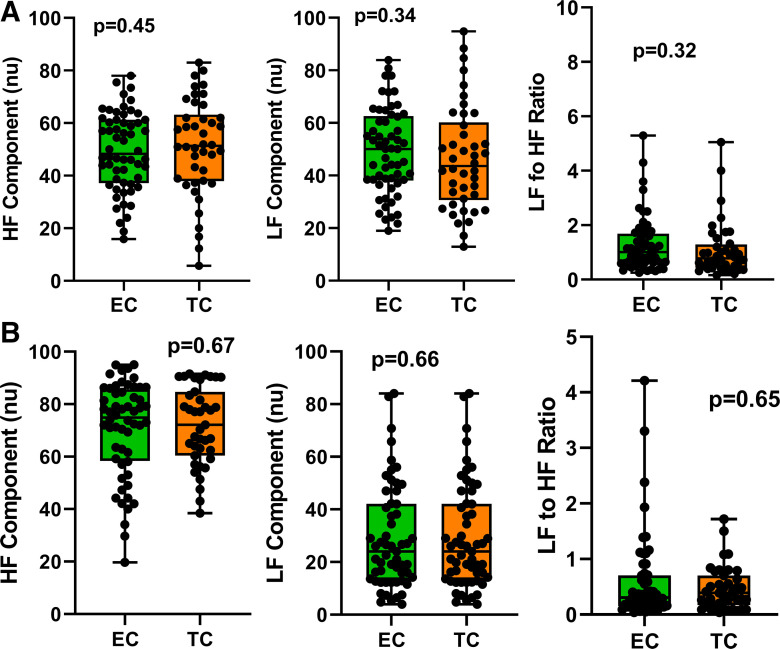

Baseline HRV

HRV parameters were analyzed for HF, an indicator of vagal activity; LF, largely sympathetic activity; and the ratio of LF to HF, reflecting the cardiac sympathetic:vagal balance (Fig. 1). Resting HRV parameters during ad libitum breathing are displayed in Fig. 1A. There was no difference in any HRV parameter between the groups. Similarly, there was no difference in any HRV parameter during controlled breathing (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Baseline heart rate variability components. HRV components, including HF (vagal activity), LF (predominantly sympathetic activity), and LF-to-HF ratio (sympathetic:vagal balance), were not different in chronic EC users (n = 58) and TC smokers (n = 42) during ad libitum breathing (A) or controlled breathing (B). Means were compared between groups using t tests and are displayed as mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. EC, electronic cigarette; HF, high frequency; HRV, heart rate variability; LF, low frequency; TC, tobacco cigarette; nu, normalized units.

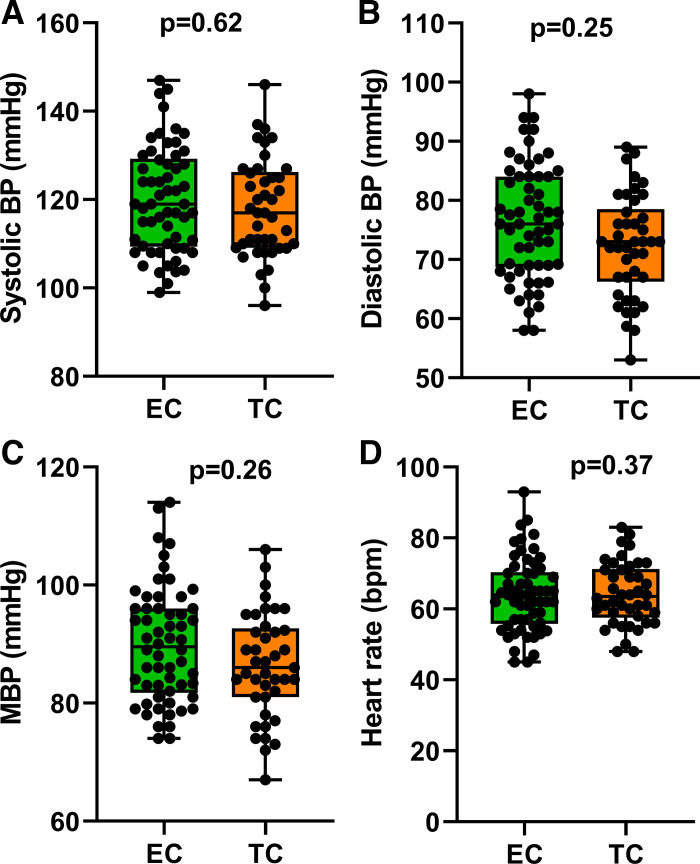

Baseline Hemodynamics

Baseline hemodynamics, including HR, SBP, DBP, and MBP, were not different between the chronic EC users and chronic TC smokers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Baseline hemodynamics. Systolic blood pressure (A), diastolic blood pressure (B), mean blood pressure (C), and heart rate (D) were not different in chronic EC users (n = 58) and TC smokers (n = 42). Means were compared between groups using t tests and are displayed as mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. BP, blood pressure; EC, electronic cigarette; MBP, mean blood pressure; TC, tobacco cigarette; bpm, beats/min.

Acute Exposures

Eighty-two smokers, including 48 chronic EC users and 34 chronic TC smokers, participated in the acute exposures study. The groups had similar demographics including age, sex, race, and BMI (data not shown).

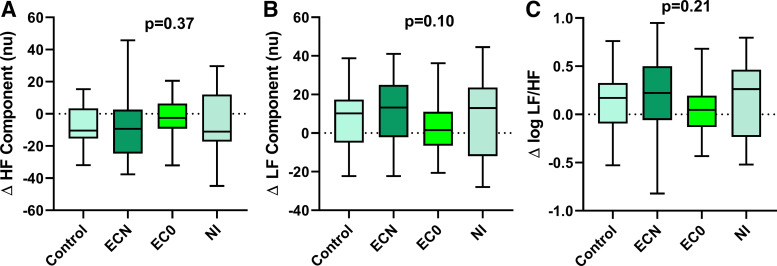

Changes in HRV following Acute EC Use

The change in plasma nicotine level when analyzed by EC device type (cigalike, pen-like, Juul) showed a trend for a smaller increase in nicotine levels with the cigalike device that did not reach significance (cigalike vs. pen-like vs. Juul, 2.68 ± 1.19 vs. 7.12 ± 1.13 vs. 5.00 ± 3.16 ng/mL, overall P = 0.09); thus the EC data was grouped as a single EC device, distinguished only by liquid with and without nicotine (Fig. 3). The increase in plasma nicotine tended to be greater, although this did not reach significance, after using the ECN versus the NI (4.67 ± 0.72 ng/mL vs. 2.72 ± 1.06 ng/mL, P = 0.13). None of the exposures, including the ECN, EC0, or NI produced a significant change in the any of the HRV parameters compared with the sham control (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Change in heart rate variability components after acute EC exposures. HRV components, including HF (A), LF (B), or LF-to-HF ratio (C), did not change significantly after using an EC with nicotine (n = 36), EC without nicotine (n = 34), or nicotine inhaler (n = 20), compared with sham control (n = 44). Means were compared using a repeated measure (mixed) model adjusting for visit and controlling for nonindependence via random subject effects. Values are mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. EC, electronic cigarette; ECN, EC with nicotine; EC0, EC without nicotine; HF, high frequency; HRV, heart rate variability; LF, low frequency; NI, nicotine inhaler; nu, normalized units.

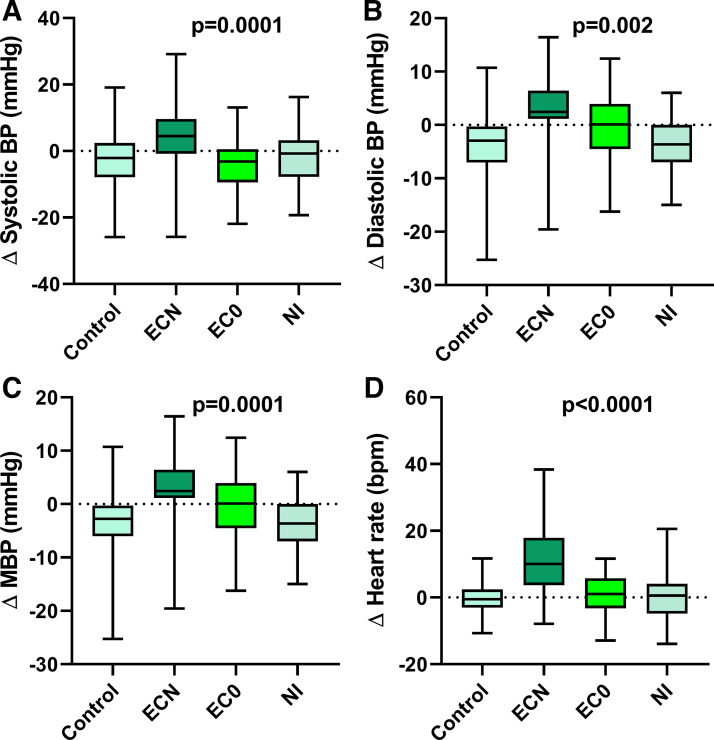

Changes in Hemodynamics following Acute EC Use

After use of the ECN, but not EC0 or NI, all hemodynamic outcomes (SBP, DBP, MBP, and HR) were increased compared with the sham control (Fig. 4). The increase in HR was strongly correlated with the increase in plasma nicotine levels (Spearman correlation Rs 0.501, P = 0.003).

Fig. 4.

Change in hemodynamics after acute EC exposures. Blood pressure, including SBP (A), DBP (B), and MBP (C), and heart rate (D) significantly increased after using the EC with nicotine (n = 35) but not after EC without nicotine (n = 33) or nicotine inhaler (n = 19), compared with sham control (n = 44). Means were compared using a repeated measure (mixed) model adjusting for visit and controlling for nonindependence via random subject effects. Values are mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. BP, blood pressure; EC, electronic cigarette; ECN, EC with nicotine; EC0, EC without nicotine; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; NI, nicotine inhaler; bpm, beats/min.

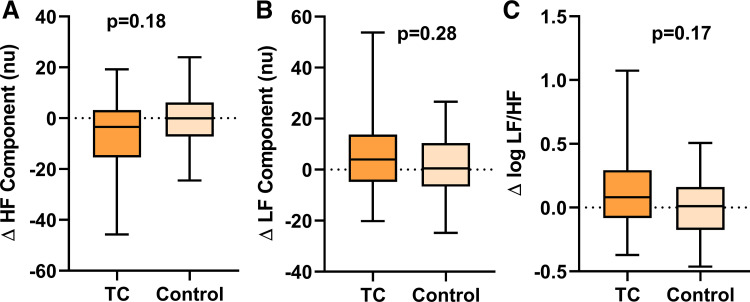

Changes in HRV following Acute TC Smoking

The increase in plasma nicotine was similar after using the TC compared with the EC with nicotine (6.17 ± 0.86 ng/mL vs. 4.67 ± 0.71 ng/mL, P = 0.18) and significantly greater than the NI (2.72 ± 1.06 ng/mL, P = 0.01) (Fig. 5). TC smoking did not cause a significant change in the any of the HRV parameters compared with the sham control (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Change in heart rate variability components after acute TC smoking. HRV components, including HF (A), LF (B), or LF-to-HF ratio (C), did not change significantly after smoking 1 TC (n = 30) compared with sham control (n = 31). Means were compared using a repeated measure (mixed) model adjusting for visit and controlling for nonindependence via random subject effects. Values are mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. HF, high frequency; HRV, heart rate variability; LF, low frequency; TC, tobacco cigarette; nu, normalized units.

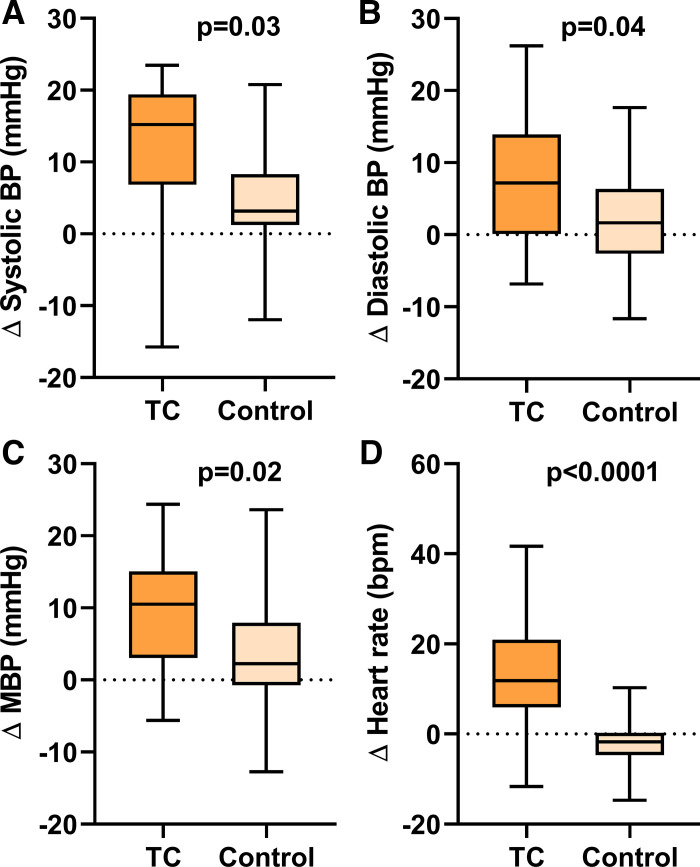

Changes in Hemodynamics following Acute TC Smoking

After smoking the TC, all hemodynamic outcomes (SBP, DBP, MBP, and HR) were increased compared with the sham control (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Change in hemodynamics after acute TC smoking. Blood pressure, including SBP (A), DBP (B), and MBP (C), and HR (D) significantly increased after smoking the TC (n = 30) compared with sham control (n = 31). Means were compared using a repeated measure (mixed) model adjusting for visit and controlling for nonindependence via random subject effects. Values are mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. BP, blood pressure; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, tobacco cigarette; bpm, beats/min.

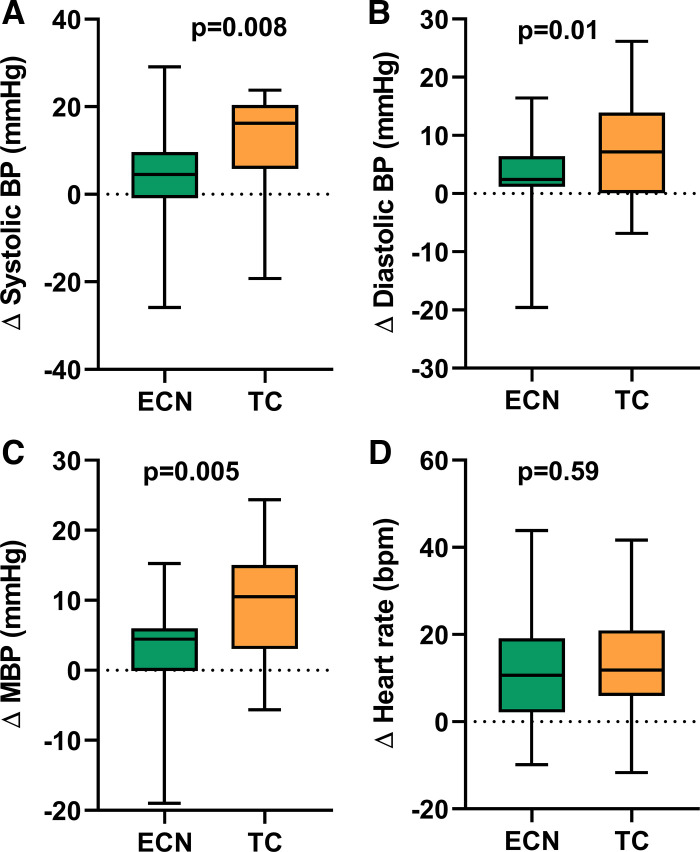

Changes in Hemodynamics after Smoking a TC Versus an ECN

The increase in SBP, DBP, and MBP, but not HR, was significantly greater after smoking the TC compared with using the ECN, despite similar increases in nicotine (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of changes in hemodynamics after acute TC vs. EC smoking. Changes in SBP (A), DBP (B), and MBP (C) but not HR (D) were significantly greater after smoking 1 TC (n = 30) compared with a comparable exposure to the EC with nicotine (n = 35), as indicated by similar increases in plasma nicotine levels. Means were compared using a repeated measure (mixed) model adjusting for visit and controlling for nonindependence via random subject effects. Values are mean (25–75%) with whiskers to minimum to maximum of the data. BP, blood pressure; ECN, electronic cigarette with nicotine; MBP, mean blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, tobacco cigarette; bpm, beats/min.

DISCUSSION

The major new findings in this study of 100 smokers, which included 58 chronic EC users (not dual users) and 42 TC smokers with similar demographics and smoking burden, are that 1) baseline HRV outcomes were similar in chronic EC users and chronic TC smokers, consistent with a similar level of cardiac sympathetic nerve activity, 2) resting hemodynamics, including blood pressure and heart rate, were not different between chronic EC users and TC smokers, 3) unlike nonusers (27), when chronic EC users acutely used an ECN, there was no significant change in HRV, although blood pressure and heart rate increased significantly, and 4) similarly, when chronic TC smokers acutely smoked one TC, HRV did not change, but blood pressure increased to a significantly greater extent than when EC users used an ECN. This greater pressor effect occurred despite similar increases in plasma nicotine levels after TC smoking and ECN use, potentially implicating the non-nicotine (tar) constituents in TC smoke, absent from EC aerosol, in this acute hemodynamic response.

When chronic EC users used an ECN compared with sham control, there was no significant increase in cardiac sympathetic activity detectable with HRV. These findings are in contrast with our previously reported findings in nicotine-naïve healthy controls, in whom acutely using an ECN, but not an EC without nicotine, significantly increased cardiac sympathetic nerve activity (27). Similar to the chronic EC users, when chronic TC smokers smoked a TC compared with sham control, there was no significant increase in cardiac sympathetic activity. Perhaps surprisingly, despite this blunted cardiac sympathetic excitation after smoking, blood pressure and heart rate were markedly and significantly increased in each group after smoking. There are at least two explanations, not mutually exclusive, for the blunted cardiac sympathetic excitation in chronic EC users and TC smokers after smoking: 1) nicotine receptors may be desensitized to the sympathomimetic effects of nicotine in chronic smokers, and/or 2) homeostatic, specifically, baroreflex-mediated responses to the nicotine’s pressor effect may have reflexively inhibited its sympathomimetic effects.

Nicotinic cholinergic receptors, found throughout the central and autonomic nervous system, become desensitized after acute or chronic nicotine exposure; in fact, these central neural effects form the basis for addiction and withdrawal (32). Acute tolerance occurs rapidly after brief nicotine exposure, and receptors become reversibly desensitized, shifting to an inactivated state within minutes (3, 10, 32, 33). This explanation is unlikely to be operative in our study, since participants had refrained from smoking for several hours as confirmed by nondetectable nicotine levels. With chronic nicotine exposure, nicotinic cholinergic receptors become chronically desensitized. This desensitization, or “tolerance” to nicotine effects, is characterized by receptor phosphorylation and potentially irreversible reductions in nicotine receptor function, which may trigger an upregulation in receptor number (3, 10, 32, 33). While chronic tolerance to nicotine may be contributing the blunted HRV responses, it is unlikely the only explanation, since BP and HR markedly and significantly increased in chronic EC users and TC smokers after acute smoking.

The sympathomimetic effects of nicotine on the cardiovascular system are the result nicotine interactions with the receptors on both peripheral and central neurons (11, 12, 31). Nicotine binds with nicotinic receptors on postganglionic peripheral sympathetic nerve endings in the heart, increasing exocytotic norepinephrine release (12). Norepinephrine release in cardiac tissue interacts with β-adrenergic receptors to increase heart rate and contractility; exocytotic norepinephrine release in vascular tissue binds to α-adrenergic receptors, causing vasoconstriction. Additionally, nicotine binds to central nicotinic receptors to increase central sympathetic neural outflow, an effect that is modulated by the baroreflexes (11, 31). The vasoconstriction and resultant increase in blood pressure that accompanies acute TC smoking activates baroreflexes, which then inhibit this central sympathetic neural outflow (31). Narkiewicz et al. demonstrated that only by infusing a vasodilator during acute TC smoking to block the vasoconstriction and thus the increase in blood pressure was the increase in central sympathetic outflow unmasked (31). Accordingly, the explanation for the discordant cardiac sympathetic and pressor responses during acute smoking in our study is likely due to this vasoconstrictor-pressor effect of acute EC or TC smoking. We speculate that the increase in blood pressure engaged the baroreflexes, resulting in a reflex inhibition in central sympathetic outflow, including cardiac sympathetic outflow detected by HRV, thereby partially masking cardiac sympathetic activation. In our prior report in nonusers in whom using the EC with nicotine markedly and significantly increased cardiac sympathetic activity measured by HRV, blood pressure did not increase; thus, the baroreflex was not engaged (27).

The greater increase in blood pressure after smoking the TC compared with ECN may be of clinical importance. Acute hemodynamic effects during TC smoking have been advanced as one mechanism whereby smoking triggers acute ischemic events (2, 4). This exaggerated pressor effect is not attributable to a greater increase in plasma nicotine levels, since the increase in plasma nicotine was not different between the two groups. We speculate that the exaggerated acute increase in blood pressure after smoking the TC is attributable to 1 or more of the 7,000 non-nicotine constituents in TC smoke. Alternatively, TC smokers compared with nonsmokers are known to have decreased arterial compliance, thus rendering them more susceptible to pressor stimuli (41). The clinical implications of the relatively greater pressor effects with acute TC smoking compared with the ECN use are uncertain but may support a harm-reduction role for ECs, and warrant further study. Of course, the potential proatherogenic effects of nicotine in EC aerosol remain (20, 36).

Limitations

Tobacco cigarette smoking and electronic cigarette use in our participants was self-reported. Unlike TC smoking burden, which can be quantified in terms of cigarettes per day, it is difficult to quantify EC burden, since most EC users are unaware how much e-liquid they use daily. Accordingly, we relied on plasma cotinine levels as an objective, shared indicator of TC or EC smoking burden that can be compared between the groups. The cotinine level was relatively low, suggesting that the participants in this study were light smokers. This is a healthy population, which included very few African Americans, so extrapolation of these findings to patients with obesity, diabetes, or hypertension, and to African Americans, remains uncertain.

Reflecting the rapidly evolving EC device technology, three different EC devices were used in the course of these studies. Upon analyzing the change in plasma nicotine level by EC device type, we only uncovered a trend for a smaller increase in nicotine levels with the cigalike device that did not reach significance. This analysis supports our approach of grouping the EC data as a single EC device, distinguished only by liquid with and without nicotine, and then relating changes in physiologic end points to changes in plasma nicotine.

The nicotine inhaler was used to provide a clean source of inhaled nicotine, and despite a small increase in plasma nicotine levels, no change in hemodynamics was detectable. This lack of any effect is perplexing, and may be explained by chronic desensitization of nicotine receptors in chronic TC and EC smokers or simply that the nicotine inhaler proved to be such an inadequate source of nicotine that its effects on the outcomes could not be adequately evaluated. In future studies, either more frequent nicotine inhaler puffing or longer nicotine inhaler exposure time should be utilized to increase delivery of nicotine from this source. Other studies of inhaled nicotine replacement therapies using different topography have reported larger changes in plasma nicotine levels accompanied by increases in heart rate and blood pressure (6).

Finally, TC smokers (1, 15, 22) and EC users (28) have been reported to have elevated cardiac sympathetic activity as assessed by HRV. One aim of this study was to determine if levels of cardiac sympathetic activity were similar in chronic EC users compared with TC smokers, indicative of similar cardiac risk, or lower, supportive a harm reduction role for ECs. Although we found similar levels of cardiac sympathetic activity in these groups, our participants were young and otherwise healthy, and thus it remains unproven that their cardiac sympathetic activity is elevated compared with other young healthy nonsmokers.

In conclusion, chronic EC users and TC smokers exhibit a similar pattern of resting HRV. Acute increases in BP and HR in EC users are attributable to nicotine, not non-nicotine, constituents in EC aerosol. The greater acute pressor effects in TC smokers after TC smoking compared with EC users after using an ECN, despite similar increases in plasma nicotine, may be indicative of additional adverse vascular effects of combusted, non-nicotine constituents in TC smoke.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP) under Contract No. TRDRP XT-320833 (to H.R.M.), 25IR-0024 (to H.R.M.), and TRDRP 28IR-0065 (to H.R.M.) and by National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Clinical Translational Science Institute (CTSI) Grant UL1TR001881.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.A. and H.R.M. conceived and designed research; S.A., K.P.H., Y.C., R.S.M., K.H.N., E.U.T., J.G., and H.R.M. performed experiments; S.A., K.P.H., K.H.N., J.G., and H.R.M. analyzed data; S.A. and H.R.M. interpreted results of experiments; S.A., K.P.H., and H.R.M. prepared figures; S.A. and H.R.M. drafted manuscript; S.A., K.P.H., Y.C., R.S.M., K.H.N., J.G., and H.R.M. edited and revised manuscript; S.A., K.P.H., Y.C., R.S.M., K.H.N., E.U.T., J.G., and H.R.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The corresponding author is deeply grateful to Dr. Allyn Mark for insightful review of this paper and continued mentorship over several decades. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02724241).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barutcu I, Esen AM, Kaya D, Turkmen M, Karakaya O, Melek M, Esen OB, Basaran Y. Cigarette smoking and heart rate variability: dynamic influence of parasympathetic and sympathetic maneuvers. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 10: 324–329, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 46: 91–111, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0033-0620(03)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benowitz NL. Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 83: 531–541, 2008. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benowitz NL. Nicotine and coronary heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 1: 315–321, 1991. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(91)90068-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigger JT Jr, Fleiss JL, Steinman RC, Rolnitzky LM, Kleiger RE, Rottman JN. Frequency domain measures of heart period variability and mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation 85: 164–171, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.85.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell B, Dickson S, Burgess C, Siebers R, Mala S, Parkes A, Crane J. A pilot study of nicotine delivery to smokers from a metered-dose inhaler. Nicotine Tob Res 11: 342–347, 2009. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students–United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 1276–1277, 2018. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dekker JM, Crow RS, Folsom AR, Hannan PJ, Liao D, Swenne CA, Schouten EG. Low heart rate variability in a 2-minute rhythm strip predicts risk of coronary heart disease and mortality from several causes: the ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities. Circulation 102: 1239–1244, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.11.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driscoll D, Dicicco G. The effects of metronome breathing on the variability of autonomic activity measurements. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 23: 610–614, 2000. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2000.110944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fattinger K, Verotta D, Benowitz NL. Pharmacodynamics of acute tolerance to multiple nicotinic effects in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 281: 1238–1246, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Calhoun DA, Bolla GB, Giannattasio C, Marabini M, Del Bo A, Mancia G. Mechanisms responsible for sympathetic activation by cigarette smoking in humans. Circulation 90: 248–253, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haass M, Kübler W. Nicotine and sympathetic neurotransmission. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 10: 657–665, 1997. doi: 10.1007/BF00053022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammoudeh AJ, Alhaddad IA. Triggers and the onset of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev 17: 270–274, 2009. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181bdba75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harte CB, Meston CM. Effects of smoking cessation on heart rate variability among long-term male smokers. Int J Behav Med 21: 302–309, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayano J, Yamada M, Sakakibara Y, Fujinami T, Yokoyama K, Watanabe Y, Takata K. Short- and long-term effects of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol 65: 84–88, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillebrand S, Gast KB, de Mutsert R, Swenne CA, Jukema JW, Middeldorp S, Rosendaal FR, Dekkers OM. Heart rate variability and first cardiovascular event in populations without known cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis and dose-response meta-regression. Europace 15: 742–749, 2013. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalkhoran S, Benowitz NL, Rigotti NA. Prevention and treatment of tobacco use: jacc health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 1030–1045, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.La Rovere MT, Bigger JT Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ; ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators . Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet 351: 478–484, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leor J, Kloner RA; The Investigators . The Northridge earthquake as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 77: 1230–1232, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Liu S, Cao G, Sun Y, Chen W, Dong F, Xu J, Zhang C, Zhang W. Nicotine induces endothelial dysfunction and promotes atherosclerosis via GTPCH1. J Cell Mol Med 22: 5406–5417, 2018. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao D, Carnethon M, Evans GW, Cascio WE, Heiss G. Lower heart rate variability is associated with the development of coronary heart disease in individuals with diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Diabetes 51: 3524–3531, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.12.3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucini D, Bertocchi F, Malliani A, Pagani M. Autonomic effects of nicotine patch administration in habitual cigarette smokers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study using spectral analysis of RR interval and systolic arterial pressure variabilities. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 31: 714–720, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199805000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malik M, Bigger JT, Camm AJ, Kleiger RE, Malliani A, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ; Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology . Heart rate variability. standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J 17: 354–381, 1996. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina de Chazal H, Del Buono MG, Keyser-Marcus L, Ma L, Moeller FG, Berrocal D, Abbate A. Stress cardiomyopathy diagnosis and treatment: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 1955–1971, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng L, Shivkumar K, Ajijola O. Autonomic regulation and ventricular arrhythmias. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 20: 38, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11936-018-0633-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Middlekauff HR, Park J, Moheimani RS. Adverse effects of cigarette and noncigarette smoke exposure on the autonomic nervous system: mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 1740–1750, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moheimani RS, Bhetraratana M, Peters KM, Yang BK, Yin F, Gornbein J, Araujo JA, Middlekauff HR. Sympathomimetic effects of acute e-cigarette use: role of nicotine and non-nicotine constituents. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e006579, 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moheimani RS, Bhetraratana M, Yin F, Peters KM, Gornbein J, Araujo JA, Middlekauff HR. Increased cardiac sympathetic activity and oxidative stress in habitual electronic cigarette users: implications for cardiovascular risk. JAMA Cardiol 2: 278–284, 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, Myers MG, Ogedegbe G, Schwartz JE, Townsend RR, Urbina EM, Viera AJ, White WB, Wright JT Jr. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension 73: e35–e66, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayanan K, Bougouin W, Sharifzadehgan A, Waldmann V, Karam N, Marijon E, Jouven X. Sudden cardiac death during sports activities in the general population. Card Electrophysiol Clin 9: 559–567, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Hausberg M, Cooley RL, Winniford MD, Davison DE, Somers VK. Cigarette smoking increases sympathetic outflow in humans. Circulation 98: 528–534, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.6.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins KA. Chronic tolerance to nicotine in humans and its relationship to tobacco dependence. Nicotine Tob Res 4: 405–422, 2002. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000018425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quick MW, Lester RA. Desensitization of neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Neurobiol 53: 457–478, 2002. doi: 10.1002/neu.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabinstein AA. Sudden cardiac death. Handb Clin Neurol 119: 19–24, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren A, Wu H, Liu L, Guo Z, Cao Q, Dai Q. Nicotine promotes atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice through α1-nAChR. J Cell Physiol, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose JE, Jarvik ME, Ananda S. Nicotine preference increases after cigarette deprivation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 20: 55–58, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahab L, Goniewicz ML, Blount BC, Brown J, McNeill A, Alwis KU, Feng J, Wang L, West R. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term e-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 166: 390–400, 2017. doi: 10.7326/M16-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sjoberg N, Saint DA. A single 4 mg dose of nicotine decreases heart rate variability in healthy nonsmokers: implications for smoking cessation programs. Nicotine Tob Res 13: 369–372, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein PK, Rottman JN, Kleiger RE. Effect of 21 mg transdermal nicotine patches and smoking cessation on heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol 77: 701–705, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuji H, Larson MG, Venditti FJ Jr, Manders ES, Evans JC, Feldman CL, Levy D. Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 94: 2850–2855, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vlachopoulos C, Kosmopoulou F, Panagiotakos D, Ioakeimidis N, Alexopoulos N, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Smoking and caffeine have a synergistic detrimental effect on aortic stiffness and wave reflections. J Am Coll Cardiol 44: 1911–1917, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, Cullen KA, Holder-Hayes E, Reyes-Guzman C, Jamal A, Neff L, King BA. Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 1225–1232, 2018. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]