Abstract

Researches on detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) high-risk samples were carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) coupled with microchip electrophoresis (MCE). Herein, we introduced a simple, rapid, automated method for detecting high-risk samples HPV16 and HPV18. In this research, general primers were initially selected to obtain sufficient detectable yield by PCR to verify feasibility of MCM method for HPV detection, then type-specific primers were further used to evaluate the specificity of MCE method. The results indicated MCE method was capable of specifically detecting high-risk HPV16 and HPV18, and also enabled simultaneous detection of multiplex samples. This MCE method described here has been successfully applied to HPV detection and displayed excellent reliability demonstrating by sequencing results. The inherent capability of MCE facilitated HPV detection conducted in a small chip with automated, high throughput, massive parallelized analysis. We envision that MCE method will definitely pave a way for clinical diagnosis, and even on-site screening of cervical cancer.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, DNA analysis, Polymerase chain reaction, Microchip electrophoresis, Detection

Graphical abstract

This work described a rapid, automatic assay based on MCE for detecting high risk samples of HPV16 and HPV18.

Highlights

-

•

A rapid, automatic assay was established for HPV detection.

-

•

The described method exhibited the advantages of facile operation mode.

-

•

The proposed method is of high sensitivity, specificity and reproducibility.

1. Introduction

Epidemiological studies have revealed persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is the leading etiological cause of cervical cancer. Typically HPV16 and HPV18 are the subtypes with the highest infection rate worldwide and classified as “high-risk” type. It is well known that cytological examination is the gold standard for diagnosing HPV infection and is routinely used in hospitals. However, traditional cytological examination is difficult to distinguish viral infection at an early stage, as a result of high possibilities of false negative. Moreover, the observation scope of Papanicolaou staining is limited, consequently hiting the roof of the sensitivity [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. Therefore, there has been a sustained effort to develop new strategies for HPV detection.

DNA investigation plays a prominent role in cervical cancer screening, because direct molecular analysis can achieve higher sensitivity and accuracy to some extent. Highly sensitive HPV DNA investigation strategies have been expeditiously developed that rely on molecular biology techniques such as PCR, sequence, and Southern Blot [7]. In general, a series of PCR based methods require instruments equipped with corresponding analytical apparatus; their products are usually analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis or capillary electrophoresis, which is time-consuming and requires numerous manual operations [8]. Sequence is of importance in DNA profiling, but it is quite expensive and requires a high degree of proficiency or professionalism of the operators [9]. Given these limitations, microchip electrophoresis (MCE) has attracted great interest due to its advantages of automation, miniaturization, and high-throughput [10]. Similar to conventional electrophoresis, microchip electrophoresis employs high voltage direct current electric field (HVDC) as the driving force for sample injection, separation and detection. Miniaturizing the amplification reaction and combining it with sample detection on one chip significantly reduce consumption of expensive reagents and avoid cross contamination [[11], [12], [13]]. Benefiting from microfluidic approach, electrophoresis has become more compact, integrated, and automated, which becomes a promising candidate to address the existing problems by providing limited scalability associated with temporal and spatial controlling. Additionally, MCE system is a fully automated analyzer that can be applied for rapid DNA or RNA analysis, enabling automatedly processing samples including pretreatment, separation, detection and data analysis. In view of the unique characteristics of MCE system, we believe that MCE is expected to be an excellent candidate for screening, diagnosis, or prognosis of HPV.

Herein, we report an integrated PCR-MCE method for detecting high-risk samples of HPV16 and HPV18 (Fig. 1). Briefly, HPV DNA was amplified using general primers and type-specific primers to achieve detectable levels and the PCR amplification products detection was performed on a microchip electrophoresis system. The reliability of the MCE system in DNA and RNA analysis has been verified in previous studies of Lin group [[14], [15], [16], [17]].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of PCR combined with MCE for HPV detection. S, SW, B and BW indicate sample, sample waste, buffer and buffer waste, respectively.

2. Experimental

2.1. Cell culture and DNA extraction

Two cervical cancer cell lines, CaSki cells and Hela cells, were supplied from Cancer Institute and Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Science (Beijing, China). CaSki cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (V/V) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% (V/V) penicillin-streptomycin, while Hela cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% (V/V) FBS and 0.1% (V/V) penicillin-streptomycin. DMEM, RPMI 1640, FBS, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Corning Corporation (Grand Island, U.S.). All cells were cultured in an incubator with a humid air atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were counted by ScepterTM 2.0 cell counter (Millipore, U.S.), and then centrifuged by Eppendorf Microfuge 5417C (Hamburg, Germany) for DNA extraction. HPV16 DNA and HPV18 DNA were extracted from CaSki cells and Hela cells respectively by using TIANamp Micro DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of extracted DNA was estimated from A260/A280 absorption ratio using U-3900s spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Japan). The extracted DNA was diluted with TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) buffer (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) before quality determination. All extracted DNA were stored at −20 °C until required for further use.

2.2. PCR primers

HPV general PCR primers were obtained according to L1 open reading frame (ORF). The general primer sequence is detailed in Table S1. HPV type-specific PCR primers were designed by the DNAMAN software (Lynnon Biosoft, USA) according to E7 ORF. The primer sequence is detailed in Table S2. The L1 and E7 information of HPV16 and HPV18 was obtained through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and was aligned by the DNAMAN software. All primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.3. PCR assay

Briefly, 20 μL general primer PCR system contained 10 ng DNA, 10 × PCR buffer (Promega, Shanghai, China), 3 mM MgCl2 (Promega, Shanghai, China), 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) solution (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), 1.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Shanghai, China), 10 pM each of primer, and double distilled water (ddH2O) was used to make up a deficiency. 20 μL type-specific primer PCR system is similar to general primer system, except the concentration of MgCl2 is 2.5 mM. PCR reactions were performed in Eppendorf Master cycler Gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The optimal cycling program was as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 9 min, followed by 39 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were detected by microchip electrophoresis system (MCE 202MultiNA, Shimadzu, Japan).

2.4. Microchip electrophoresis

The extracted HPV DNA was labeled online with SYBR Gold SYBR Gold (Invitrogen, Germany). The DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Germany) consisting of 19 DNA fragments was used as internal standard to identify the size of DNA fragments with the smallest fragment being 25 bp and the largest fragment being 500 bp; the size interval between the two fragments was 25 bp (excluding 475 bp), and diluted with 1×TE buffer when using. The DNA 500 Marker (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) included a low maker (LM) and an upper marker (UM). MCE can only detect DNA fragments between LM and UM. A blue light emitting diode (LED) at 470 nm and the fluorescence detection at 525 nm was equipped in MCE.

In order to obtain reliable electrophoresis results, appropriate pre-treatment of the microchip was necessary. Before analysis, the chip channel was cleaned with ultrapure water to ensure the smoothness, followed by drying with air. Afterwards, the separation buffer, the DNA ladder, the marker, and the sample were placed on the corresponding positions of microchip, and the on-chip online mixing mode was selected to set the corresponding parameters. Sample analysis can start after confirming steps stated above. For HPV detection, the parameters are as follows, sample loading: VS = 280 V, VSW = 510 V, VB = 320 V, and VBW = 0 V; sample analysis: VS = 250 V, VSW = 250 V, VB = 0 V, and VBW = 1000 V. HPV analysis based on MCE can easily achieve sample consumption of 2 μL and analysis time less than 3 min.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Quality of extracted DNA

The quality of extracted DNA from CaSki cells and Hela cells was investigated, indicating the DNA extraction was highly purified (Fig. S1). PCR reaction was performed using the extracted HPV DNA as templates to enrich target content. The PCR reaction condition was constructed to 39 identical PCR cycles. The procedure for each cycle typically consisted of (1) denaturing, (2) annealing, and (3) extension.

3.2. HPV detection by general primer PCR-MCE

The HPV general primers reported in earlier studies were IU/IWDO, and MY09/11 [18,19] GP5/6 [20], and then the improved version PGMY [21] and GP5+/6+ [22,23] were reported. GP5+/6+, MY09/11 belongs to degenerate primers, and the bases at certain positions are variable, which will have a certain degree of effect on the synthesis of primers and subsequent analysis. Considering the length of the transformed PCR products and the effect of degenerate primers, the primer set PGMY09/11 was conservatively selected in order to expand the PCR products gradually and accurately. PGMY09/11 primers were initially utilized to obtain detectable yields to assess the feasibility of MCE method for HPV detection. The detection assays were performed by amplification of HPV positive cells (CaSki cells and HeLa cells) with general primer, followed by MCE analysis. Part of collected PCR products were sequenced by Sangon Biotech. The results (Fig. 2) indicated HPV16 and HPV18 were successfully amplified using the primer set PGMY09/11. Additionally, the PGMY09/11 primer set was optimized pairwise to screen optimal primers of HPV16 and HPV18 for subsequent DNA sequencing, PGMY09-F/11-C and PGMY09-N/11-A were optimized primers for HPV16 and HPV18 respectively. Under the same conditions, the target signal significantly increased when using optimized primers. The sequencing results are shown in Table S3. The length of HPV16 general PCR products amplified from CaSki cell DNA was 451 bp, while the length of HPV18 general PCR products amplified from Hela cell DNA was 453 bp. As expected, the sequencing results were consistent with existing sequences in GeneBank, indicating the feasibility of MCE method applied to HPV detection.

Fig. 2.

The microchip electrophoretograms of HPV16 and HPV18 detection. (A) The electrophoretogram of HPV16 detection by general primer PCR and optimized primer PCR. 1: DNA ladder; 2: general primer PGMY09/11 PCR product; 3: PGMY09-F/11-C PCR product. (B) The electrophoretogram of HPV18 detection by general primer PCR and optimized primer PCR. 1: DNA ladder; 2: general primer PGMY09/11 PCR product; 3: PGMY09-N/11-A PCR product.

Overall, the above results demonstrated the feasibility of MCE method for HPV detection. The general primer set PGMY09/11 enabled simultaneous amplification of multiple HPV subtypes, the optimized primers significantly increased the signal intensity of the HPV amplification product. However, due to the PCR amplification product fragments of various HPV subtypes are close in size, it is impossible to distinguish subtypes from the electropherogram; therefore, the positive results can only indicate the presence of HPV infection, but it is hard to distinguish subtypes.

3.3. HPV detection by type-specific primer PCR-MCE

Type-specific detection of HPV16 and HPV 18 were performed using type-specific primers corresponding to genotype to amplify HPV DNA, and then analyzed by MCE. Type-specific primers for HPV16 and HPV18 were designed according to the HPV E7 conserved region to further assess the specificity of HPV detection by MCE method [24,25]. Part of PCR amplified products were send to sequence. The detection results are shown in Fig. 3. The signals corresponding to HPV16 and HPV18 were clearly visible, indicating the type-specific primers were effective and highly specific. To comprehensively evaluate the specificity of HPV detection by MCE method, HPV16 and HPV18 type-specific primers were utilized to amplify HPV18 DNA and HPV16 DNA, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, the target signal intensity was stronger when using corresponding type-specific primers, indicating the type-specific primers designed in this study had good specificity and there was no cross-amplification between two subtypes. The sequencing results are shown in Table S4, which suggested that the length of the amplified product fragment of HPV16 is 203 bp, and the length of the amplified product fragment of HPV18 is 244 bp. After comparison, it was consistent with the existing sequences in GeneBank, which further demonstrated the reliability of MCE method.

Fig. 3.

The electrophoretograms of HPV detection by type-specific primer PCR-MCE. 1: DNA ladder; 2: HPV16 DNA + HPV16 type-specific primer; 3: HPV18 DNA + HPV18 type-specific primer; 4: HPV16 DNA + HPV18 type-specific primer; 5: HPV18 DNA + HPV16 type-specific primer.

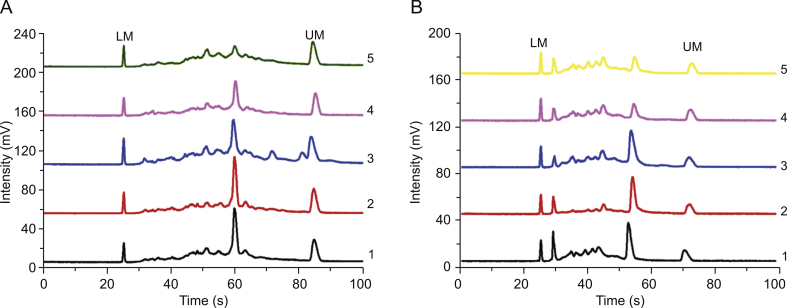

Furthermore, the sensitivity of HPV detection by MCE method was evaluated, and different HPV DNA concentrations were obtained by controlling the cell density of the extracted DNA. To study the detection limitation, the density of CaSki cells and Hela cells used for HPV16 and HPV18 extraction was controlled to a series of 10 fold dilutions (from 106 cells/mL to 102 cells/mL). Corresponding experiments were conducted for various cell densities. The detection results of various cell densities after MCE analysis are shown in Fig. 4. It can be seen from the results that the intensity of target signal was increased along with the increase of cell density. For HPV16 analysis, the MCE system could detect CaSki cell density as low as 102 cells/mL. And for HPV18 analysis, Hela cell density down to 102 cells/mL could be well detected and analyzed by MCE method. Therefore, it can be concluded that the sensitivity of both HPV16 and HPV18 detection is 102 cells/mL.

Fig. 4.

The sensitivity of HPV detection. (A) The sensitivity of HPV16 detection by a serial 10 fold dilutions CaSki cell density (from 106 to 102 CaSki cells/mL). 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 represent CaSki cell density, from 106 to 102 cells/mL. (B) The sensitivity of HPV18 detection by a serial 10 fold dilutions Hela cell density (from 106 to 102 Hela cells/mL). 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 represent Hela cell density, from 106 to 102 cells/mL.

In addition, it is well accepted that cervical cancer may be caused by simultaneous infection with certain kinds of HPV such as HPV16 and HPV18. Therefore, the MCE method was further evaluated by simultaneous detection of HPV16 and HPV 18. We added HPV16 type-specific primers, HPV18 type-specific primers, HPV16 DNA and HPV18 DNA for multiplex PCR in the same reaction and finally successfully achieved the simultaneous detection of two subtypes. As shown in Fig. 5, the results indicated the MCE method was target specific for HPV analysis. Although the amplification signal of HPV18 is obviously stronger while that of HPV16 is a little weaker, this may be due to a competition existing between the two amplifications in the same system, resulting in an obvious target peak of one amplification and a weaker amplification of the other. Overall, the results suggested that the MCE method described here enabled simultaneous detection of HPV16 and HPV18, as well as distinguishing two high-risk HPV subtypes.

Fig. 5.

Simultaneous detection of HPV16 and HPV18. (A) The simultaneous detection results of HPV16 and HPV18. (B) An enlargement of the gray part of figure A.

4. Conclusion

In summary, a rapid and sensitive method for high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 detection was established, and sequencing results confirmed the reliability of this method. This method for HPV detection exhibited several superiorities to other methods. First of all, the inherent factor of integration feasibility rendered HPV analysis more practical, which is previously difficult for conventional methods, the integrated microchip detection improves the efficiency of separating DNA fragments and reduces cross contamination. Secondly, automated analysis significantly overcame multistep sample manipulation and reduced execution time. Finally, this method remarkably reduced reagent consumption and enabled high-throughput analysis with high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. The method proposed here may not be as versatile as a dreamful “golden method” that is expected to solve all the chemical and biological problems we meet, but we hold the promise that the establishment of this assay is conductive to the screening of cervical cancer, and has good development prospects in life science, clinical testing and on-site cancer monitoring.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21727814, 81872829, 21621003, 21890740).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2020.04.003.

Contributor Information

Xueji Zhang, Email: zhangxueji@szu.edu.cn.

Jin-Ming Lin, Email: jmlin@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Eklund C., Forslund O., Wallin K.L. The 2010 global proficiency study of human papillomavirus genotyping in vaccinology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:2289–2298. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00840-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodman C.B.J., Collins S.I., Young L.S. The natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issues. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2007;7:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers J.M., Jacobs M.V., Manos M.M. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roden R., Wu T.C. How will HPV vaccines affect cervical cancer. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2006;6:753–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2002;2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronco G., Joakim D. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524–532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle P.E., Stoler M.H., Wright T.J. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:880–890. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young L.S., Bevan I.S., Johnson M.A. The polymerase chain reaction: a new epidemiological tool for investigating cervical human papillomavirus infection. BMJ. 1989;298:14–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asiello P.J., Baeumner A.J. Miniaturized isothermal nucleic acid amplification, a review. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1420–1430. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00666a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manz A., Graber N., Widmer H.M. Miniaturized total chemical analysis systems: a novel concept for chemical sensing. Sens. Actuators, B. 1990;1:244–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naora H., Montell D.J. Ovarian cancer metastasis: integrating insights from disparate model organisms. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2005;5:355–366. doi: 10.1038/nrc1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raynie D.E. Modern extraction techniques. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:3997–4004. doi: 10.1021/ac060641y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mora M.F., Greer F., Stockton A.M. Toward total automation of microfluidics for extraterrestrial in situ analysis. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:8636–8641. doi: 10.1021/ac202095k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng Y., Yi L., Lin X. A non-invasive genomic diagnostic method for bladder cancer using size-based filtration and microchip electrophoresis. Talanta. 2015;144:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X., Wu J., Liu W. Detection of BCR-ABL using one step reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and microchip electrophoresis. Methods. 2013;64:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yi L., Xu X., Lin X. High-throughput and automatic typing via human papillomavirus identification map for cervical cancer screening and prognosis. Analyst. 2014;139:3330–3335. doi: 10.1039/c4an00329b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Q., Lin X., Lin L. A comparative study of three different nucleic acid amplification techniques combined with microchip electrophoresis for HPV16 E6/E7 mRNA detection. Analyst. 2015;140:6736–6741. doi: 10.1039/c5an00944h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soderlund Strand A., Carlson J., Dillner J. Modified general primer PCR system for sensitive detection of multiple types of oncogenic human papillomavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:541–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02007-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrons C., Kleter B., Jelley R. Detection and genotyping of human papillomavirus DNA by SPF10 and MY09/11 primers in cervical cells taken from women attending a colposcopy clinic. J. Med. Virol. 2002;67:246–252. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Roda Husman A.M., Walboomers J.M., van den Brule A.J. The use of general primers GP5 and GP6 elongated at their 3’ ends with adjacent highly conserved sequences improves HPV detection by PCR. J. Gen. Virol. 1995;76:1057–1062. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong S.P., Shin S.K., Lee E.H. High-resolution human papillomavirus genotyping by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1476–1484. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hesselink A.T., Heideman D.A.M., Berkhof J. Comparison of the clinical performance of papillo check human papillomavirus detection with that of the GP5+/6+-PCR-enzyme immunoassay in population-based cervical screening. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:797–801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01743-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Brule A.J., Pol R., Fransen-Daalmeijer N. GP5+/6+ PCR followed by reverse line blot analysis enables rapid and high-throughput identification of human papillomavirus genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:779–787. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.779-787.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan M.J., Castle P.E., Lorincz A.T. The elevated 10-year risk of cervical precancer and cancer in women with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 or 18 and the possible utility of type-specific HPV testing in clinical practice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. (Bethesda) 2005;97:1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens M.P., Garland S.M., Rudland E. Comparison of the digene hybrid capture 2 assay and Roche AMPLICOR and LINEAR ARRAY human papillomavirus (HPV) tests in detecting high-risk HPV genotypes in specimens from women with previous abnormal pap smear results. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2130–2137. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02438-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.