Nitrogen assimilation in developing maize seeds is regulated by the SnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 signaling axis, which is responsive to diurnal sucrose concentrations.

Abstract

Zeins are the predominant storage proteins in maize (Zea mays) seeds, while Opaque2 (O2) is a master transcription factor for zein-encoding genes. How the activity of O2 is regulated and responds to external signals is yet largely unknown. Here, we show that the E3 ubiquitin ligase ZmRFWD3 interacts with O2 and positively regulates its activity by enhancing its nuclear localization. Ubiquitination of O2 enhances its interaction with maize importin1, the α-subunit of Importin-1 in maize, thus enhancing its nuclear localization ability. We further show that ZmRFWD3 can be phosphorylated by a Suc-responsive protein kinase, ZmSnRK1, which leads to its degradation. We demonstrated that the activity of O2 responds to Suc levels through the ZmSnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 signaling axis. Intriguingly, we found that Suc levels, as well as ZmRFWD3 levels and the cytonuclear distribution of O2, exhibit diurnal patterns in developing endosperm, leading to the diurnal transcription of O2-regulated zein genes. Loss of function in ZmRFWD3 disrupts the diurnal patterns of O2 cytonuclear distribution and zein biosynthesis, and consequently changes the C/N ratio in mature seeds. We therefore identify a SnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 signaling axis that transduces source-to-sink signals and coordinates C and N assimilation in developing maize seeds.

INTRODUCTION

Seed development in crops depends on the availability of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), supplied by the mother plant, and on the capacity of sink tissues to assimilate them. In developing maize (Zea mays) seeds, starch, protein, and oil accumulate approximately synchronously (Ingle et al., 1965), primarily in the endosperm for starch and storage proteins and in the embryo for oil (Earle et al., 1946; Tsai, 1983). Suc is the primary C source for starch biosynthesis in the developing maize endosperm: indeed, ∼90% of C arriving in developing seeds is in the form of Suc (Moutot et al., 1986).

C and N assimilation processes are interrelated in seed development, as indicated by the reduction in growth that occurs when either element is lacking (Faleiros et al., 1996). The starch in maize seeds represents ∼70% of the total C reserves. Zein proteins comprise the largest storage reserves of N in the maize endosperm, storing 50 to 70% of total N (Mertz et al., 1964; Thompson and Larkins, 1994; Holding and Larkins, 2009; Holding and Messing, 2013). Thus, the balance of C and N in maize endosperm largely depends on the coordination of starch and zein metabolism, and C and N accumulation in developing maize endosperm is well coordinated. Pyruvate phosphate dikinases contribute to the metabolic regulation of starch and protein accumulation by converting pyruvate to phosphoenolpyruvate in the glycolytic pathway (Méchin et al., 2007; Lappe et al., 2018). At the transcriptional level, the endosperm-specific transcription factor (TF) Opaque2 (O2) activates genetic programs that link C and N accumulation during endosperm development (Schmidt et al., 1987, 1990; Zhang et al., 2016). Specifically, O2 directly regulates the transcription of both zein-coding genes and genes related to starch biosynthesis, including those encoding pyruvate phosphate dikinases and starch synthase III (Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhan et al., 2018).

SNF1-related kinase1 (SnRK1), whose kinase activity is induced by low Suc concentrations, is a well-known metabolic regulator (Margalha et al., 2016). In addition to modulating the activity of metabolic enzymes, such as Suc synthase and ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase (Purcell et al., 1998; Tiessen et al., 2003), SnRK1 regulates transcription by phosphorylating TFs such as Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) basic LEUCINE ZIPPER (bZIP63; Mair et al., 2015). Recent studies have confirmed that Arabidopsis SnRK1 regulates the transcriptional activity of bZIP63 and established that bZIP63 regulates the circadian period (Frank et al., 2018), a process known to be required for Suc-induced circadian phase changes in leaves (Haydon et al., 2013). Circadian rhythms allow plants to adapt to the daylight cycles caused by the rotation of the Earth. Sugar signals, and especially Suc signaling, can entrain circadian rhythms by regulating the expression of genes encoding circadian clock components early in the light part of the diurnal cycle (reviewed by Webb et al., 2019). Whether and how C and N accumulation in non-photosynthetic sink organs, such as developing crop seeds, contributes to any rhythmic regulation is unknown.

Here, we showed that the E3 ubiquitin ligase ZmRFWD3 ubiquitinates O2 to positively regulate its activity by enhancing its nuclear localization. We also established that ZmRFWD3 is regulated by ZmSnRK1, a Suc-responsive protein kinase, in a diurnal rhythmic fashion. We further discovered that the cytonuclear distribution of O2 follows a diurnal rhythm, as do the transcription rates of zein-coding genes strictly regulated by O2. Loss of function of ZmRFWD3 significantly disrupted the diurnal rhythm of zein gene transcription, and, consequently, slightly changed the C/N ratio in mature seeds. Thus, our study established a SnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 signaling axis that transduces source-to-sink signals and coordinates C and N assimilation in developing seeds, suggesting the possibility of optimizing the C/N ratio by manipulating this signaling axis.

RESULTS

The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase ZmRFWD3 Interacts with O2

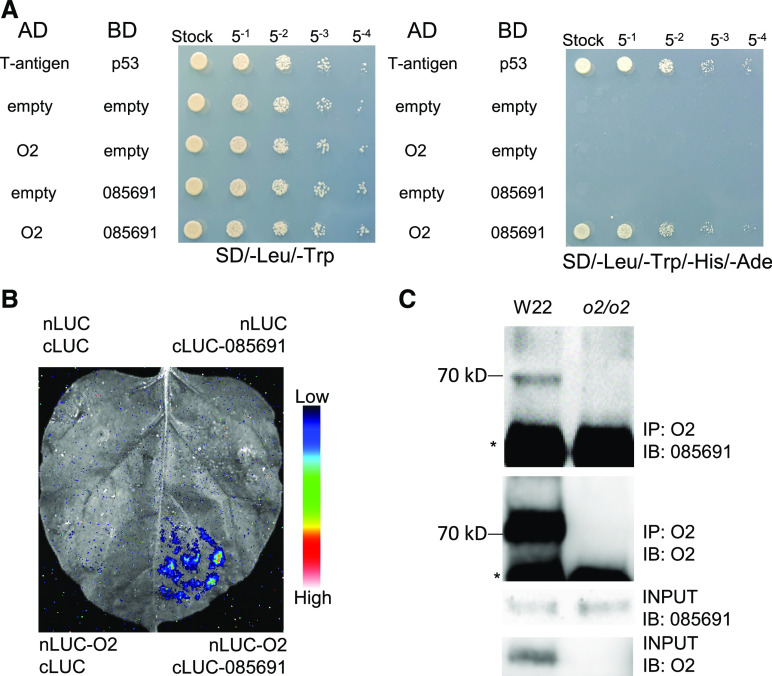

We previously screened for O2 interaction partners (Zhang et al., 2012); given the established ability of post-translational modifications (PTMs) to regulate the function of proteins, we were particularly interested in O2 interaction partners known to be functionally associated with PTMs. We reassessed the yeast-2-hybrid (Y2H) screen data and focused here on a potential O2-interacting protein, encoded by the maize gene GRMZM2G085691 (Figure 1A). We functionally confirmed the interaction of the GRMZM2G085691 gene product and O2 in vivo using both luciferase (LUC) complementation imaging (LCI) and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays (Figures 1B and 1C). The encoded protein possesses a C3HC4 zinc finger RING-type domain and a WD40/YVTN repeat domain: we thus named this protein Z. mays RING Finger and WD40 repeat 3 (ZmRFWD3), based on its homology to human (Homo sapiens) RFWD3 (Figures 2A and 2B; Supplemental Figure 1; Supplemental Files 1 and 2; Fu et al., 2010). Moreover, Y2H assays indicated that the WD40 repeat domain of ZmRFWD3 mediates the interaction of the protein with O2 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The GRMZM2G085691 Gene Product Interacts with O2.

(A) Y2H analysis of the interaction between the GRMZM2G085691-encoded protein and O2. AD, GAL4 activation domain; BD, GAL4 DNA binding domain. For the interaction of the GRMZM2G085691 gene product with O2, we added 10 mM of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) to the SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade plate to prevent auto-activation. 085691: GRMZM2G085691.

(B) LCI assay showing the interaction of O2 and the GRMZM2G085691 gene product in N. benthamiana leaves. The lower-right section shows the interaction signal; the three other sections show the signals from the negative controls. The specific combinations are labeled next to each section. The signal intensity represents interaction activity. 085691: GRMZM2G085691.

(C) Co-IP assay to confirm the O2-GRMZM2G085691 interaction. Immature kernel extracts were incubated with anti-O2 antibody and precipitated with Protein A Sepharose Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total protein and protein immunoprecipitated by anti-O2 antibody were immunoblotted with anti-GRMZM2G085691 and anti-O2 antibodies. 085691: GRMZM2G085691.

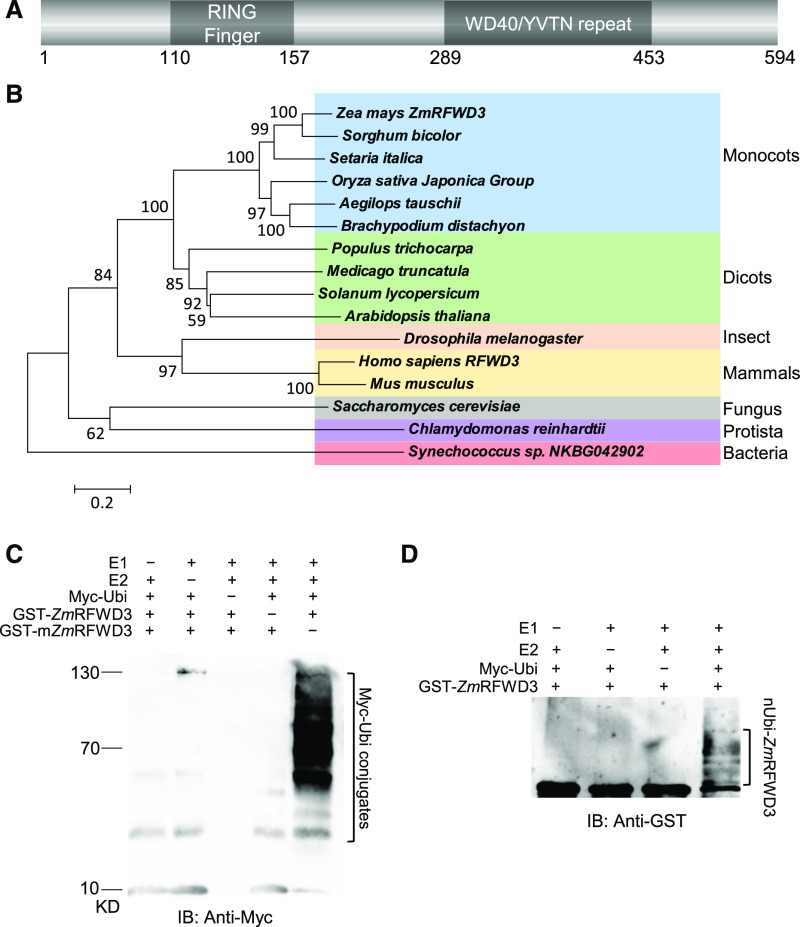

Figure 2.

ZmRFWD3 Is a RING-Containing E3 Ubiquitin Ligase.

(A) Domain annotation of ZmRFWD3.

(B) Phylogenetic relationships of ZmRFWD3 and its homologues in other species. Distances were estimated using the neighbor-joining algorithm. The numbers at the nodes represent their confidence level, shown as a percentage from 1,000 bootstraps. The scale bar indicates the average number of amino acid substitutions per site. The Synechococcus homologue was used as an outgroup.

(C) In vitro E3 ligase assay showing the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of ZmRFWD3. ZmRFWD3 E3 activity was assayed in the presence or absence of E1, UbcH5b (E2), Myc-Ubi, GST-ZmRFWD3, and/or GST-mZmRFWD3. The ubiquitination complex was detected with anti-Myc antibody.

(D) In vitro self-ubiquitination of ZmRFWD3. Ubiquitination of ZmRFWD3 was assayed in the presence or absence of E1, E2, Myc-Ubi, and/or GST-ZmRFWD3.

We suspected that, as a RING-domain-containing protein, ZmRFWD3 might have E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (Deshaies and Joazeiro, 2009). We therefore performed ubiquitination assays with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged ZmRFWD3 and GST-ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A, a mutated version of ZmRFWD3 that is expected to lack Zn2+-chelating ability (Supplemental Figure 1). We observed E3 ubiquitin ligase activity with wild-type ZmRFWD3, but not with the ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A mutant, indicating that the RING domain mediates the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of ZmRFWD3 (Figure 2C). We further confirmed that ZmRFWD3 self-ubiquitinated the activity through a ubiquitination assay (Figure 2D).

ZmRFWD3 Ubiquitinates O2 at Lys-235

We next used gene editing by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-Cas9 (Qi et al., 2016b) to generate maize lines bearing mutations affecting ZmRFWD3 function, including zmrfwd3-mu1 and zmrfwd3-mu2 (Supplemental Figure 3A): zmrfwd3-mu1 has a single-nt A deletion after 424 bp of the ZmRFWD3 open reading frame (ORF), and zmrfwd3-mu2 has a two-nt CC deletion at bp 417 and 418 of the ZmRFWD3 ORF, each resulting in ZmRFWD3 loss of function due to a frameshift and premature translation termination. We crossed each mutant into the W22 genetic background and then examined the accumulation of ZmRFWD3 in immature seeds of the mutants at 15 d after pollination (DAP) in F2 segregating ears via immunoblotting with an anti-ZmRFWD3 antibody. We detected no ZmRFWD3 protein in the mutants (Supplemental Figure 3B).

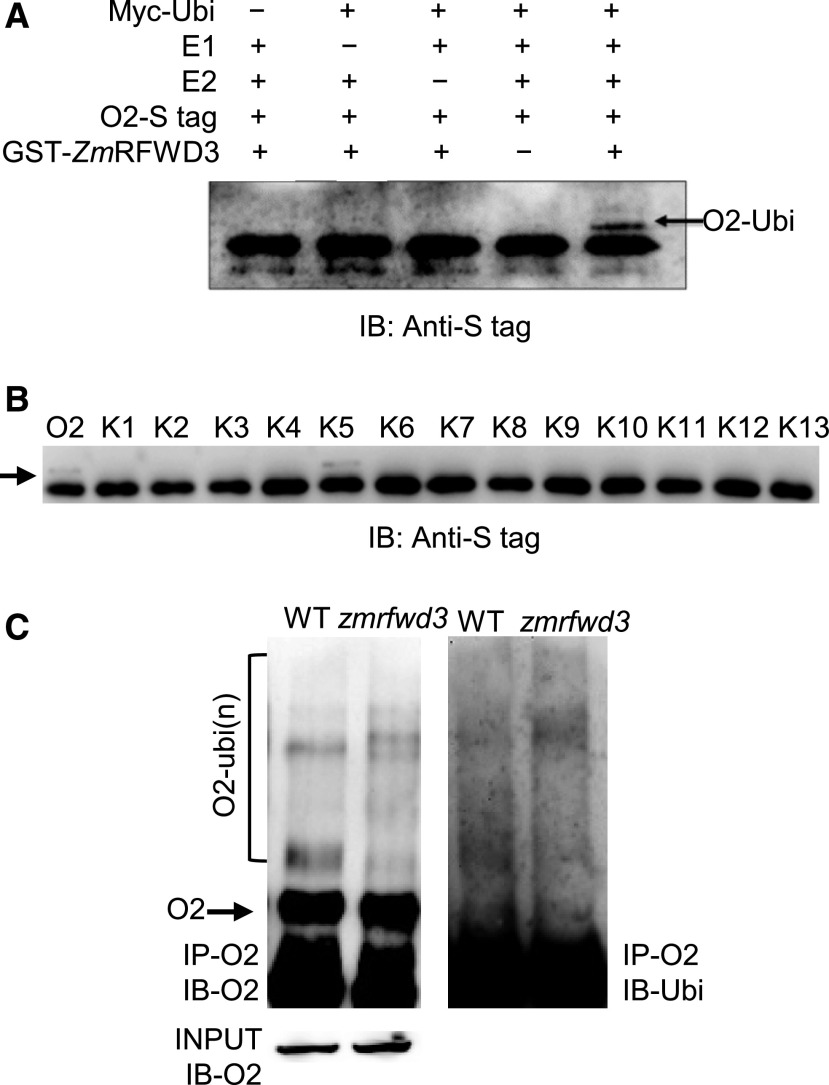

Because O2 interacts with ZmRFWD3, we suspected that O2 might be a substrate of ZmRFWD3 for ubiquitination. Indeed, we observed that O2, an interaction partner of ZmRFWD3 in vivo, was ubiquitinated by ZmRFWD3 in vitro (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

ZmRFWD3 Ubiquitinates O2 at Lys-235.

(A) In vitro ubiquitination of O2. Ubiquitination of O2 was assayed in the presence or absence of Myc-Ubi, E1, E2, O2-S tag, and/or GST-ZmRFWD3. Ubiquitination of S-tagged O2 was detected with anti-S tag antibody.

(B) Screening for the O2 ubiquitination site by in vitro ubiquitination assay. All 13 Lys (K) sites in O2 were mutated to Arg (R), and then the mutated sites were individually restored from R to K and used as substrates for a ZmRFWD3-mediated in vitro E3 ligase assay. The numbers (1 to 13) above the blot indicate the Lys sites restored: K134, K143, K178, K226, K235, K237, K251, K256, K266, K282, K303, K305, and K312.

(C) O2 ubiquitination in wild-type (WT) and zmrfwd3 developing seeds. Seeds (15 DAP) from the wild type and the zmrfwd3 mutant were harvested for immunoprecipitation with anti-O2 antibody. Anti-O2 and anti-ubiquitin antibodies were used to detect O2 and ubiquitinated O2, respectively. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

Because proteins are typically ubiquitinated at Lys residues, we conducted Lys mutation scanning of 13 residues in O2 and identified Lys-235 as a likely ubiquitination site (Figure 3B; Supplemental Figure 4). Consistent with these biochemical results, analysis of extracts from wild-type and zmrfwd3-mu1 plants revealed that oligo-ubiquitination of O2 requires functional ZmRFWD3 (Figure 3C).

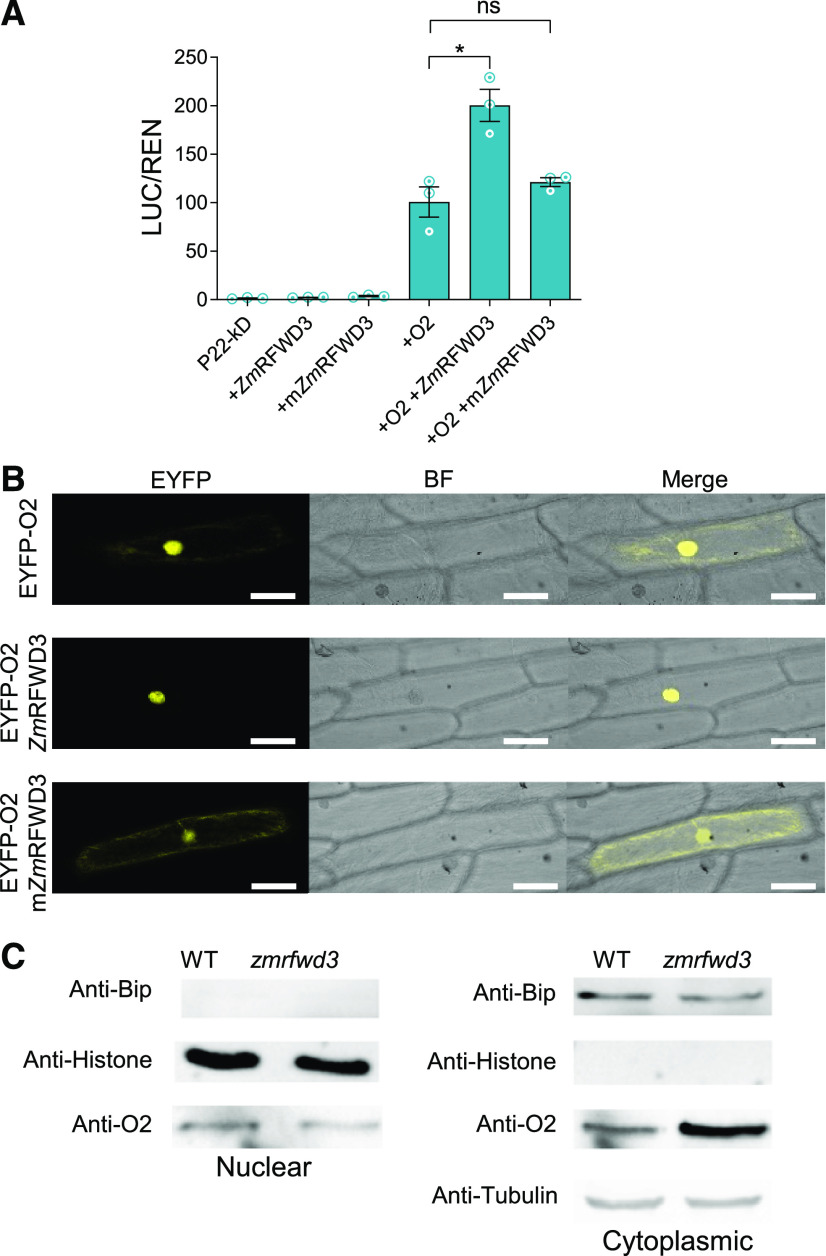

Ubiquitination by ZmRFWD3 Enhances O2 Nuclear Localization

We next conducted dual-LUC transient transcriptional activity assays in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, using a firefly LUC reporter driven by the 22-kD α-zein promoter, to test whether ZmRFWD3-mediated ubiquitination affects O2-mediated transcription of target genes (Schmidt et al., 1992). The results showed that wild-type ZmRFWD3, but not ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A, enhanced O2-mediated reporter expression (Figure 4A). Moreover, given that the C111A and C114A mutations in ZmRFWD3 did not alter its interaction with O2 (Supplemental Figures 5A and 5B), these results support the possibility that ZmRFWD3 enhances O2 transactivation by catalyzing its ubiquitination.

Figure 4.

ZmRFWD3-Mediated Ubiquitination Regulates the Cytonuclear Distribution of O2.

(A) Dual-LUC transcription activation assay showing the activation of the promoter of the 22-kD α-zein by ZmRFWD3 (or mZmRFWD3), O2, and both together. The expression level of REN was used as an internal control. The LUC/REN ratio represents the relative activity of 22-kD α-zein promoter. mZmRFWD3, ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A. Data are values from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate ±sd (n = 3). Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; *P < 0.05; ns, non-significant.

(B) Fluorescence signal resulting from the expression of O2-eYFP alone or together with ZmRFWD3 or mZmRFWD3 in onion epidermal cells. mZmRFWD3, ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A. (Left to right representations) Signal from eYFP and bright-field (BF) microscopy and the merged image. Similar results were observed in at least 10 cells from three independent experiments. Scale bars = 50 μm.

(C) Immunoblot analysis using anti-O2 antibody shows O2 levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of 15-DAP wild-type (WT) and zmrfwd3 maize seeds. The purity of the nuclear or cytosolic fraction was examined by immunoblot analysis using anti-histone H3 or binding immunoglobulin protein (anti-BIP) antibody, respectively. This experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results.

A previous study (Zhang et al., 2012) showed that O2 localizes to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The enhancement of O2 transcriptional activity by ZmRFWD3 may be caused by cytonuclear shuttling. To determine whether ZmRFWD3 is involved in cytonuclear shuttling of the O2 protein, we transiently expressed a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-O2 fusion and ZmRFWD3 individually or in combination in onion epidermal cells. O2 localized to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm when expressed alone but became concentrated in the nucleus when co-expressed with ZmRFWD3 (Figure 4B). To confirm this result in vivo, we determined the subcellular distribution of the O2 protein at 15 DAP (sampled at noon) in zmrfwd3-mu1 and wild-type seeds. O2 preferentially localized to the nucleus in the wild-type seeds but preferentially accumulated in the cytosol of zmrfwd3-mu1 seeds (Figure 4C; Supplemental Figure 6). These results suggest that ZmRFWD3-mediated ubiquitination of O2 can promote its cytonuclear shuttling.

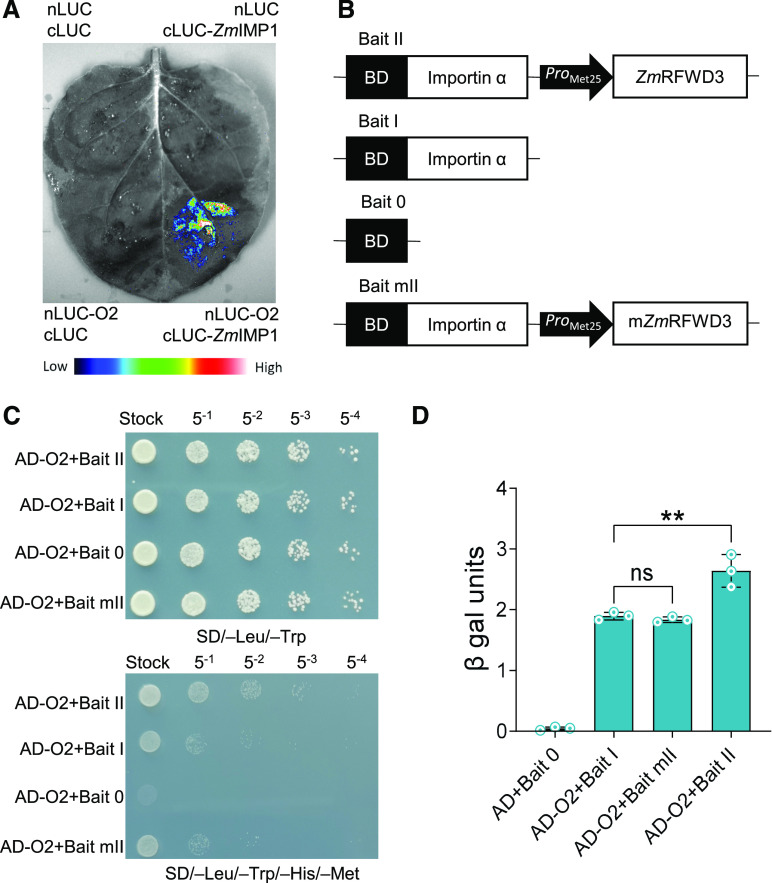

The translocation of a TF from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is often mediated by importin proteins (Görlich et al., 1994). According to our aforementioned previous Y2H-based screen (Zhang et al., 2012), O2 also interacts with maize importin1 (ZmIMP1), which is the α-subunit of an importin known to bind to the nuclear localization signal of proteins (Moroianu et al., 1995). Notably, the Lys residue K-235 of O2 is located within a nuclear localization signal sequence (Varagona et al., 1992), and we confirmed the interaction of O2 with ZmIMP1 by LCI assay (Figure 5A). Yeast three-hybrid (Y3H) assays confirmed that the ubiquitination of O2 at K-235 did indeed enhance its interaction with ZmIMP1 (Figures 5B and 5C). Quantitative β-galactosidase assays showed that the O2–ZmIMP1 interaction increased upon expression of wild-type ZmRFWD3 but not ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A (Figure 5D), further confirming this interaction-promoting role of ubiquitination.

Figure 5.

O2-ZmIMP1 Interaction Is Enhanced by ZmRFWD3-Mediated O2-Ubiquitination.

(A) LCI assay confirming the interaction of O2 and ZmIMP1 in N. benthamiana leaves. The lower-right section shows the interaction signal; the other three sections show the signals from the negative controls. The specific combinations are labeled next to each section. The fluorescent signal intensity represents interaction activity.

(B) Schematics of baits and prey constructs used for Y3H assays.

(C) Y3H assays showing that the O2-ZmIMP1 interaction was enhanced in the presence of full-length ZmRFWD3.

(D) Relative interaction activities of Y3H were evaluated using β-galactosidase assays. Data are means (±sd). Three replicates were performed, each with five technical replicates. Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; **P < 0.01; ns, non-significant.

ZmSnRK1α2 Phosphorylates ZmRFWD3 at S-479 and Lowers its Stability

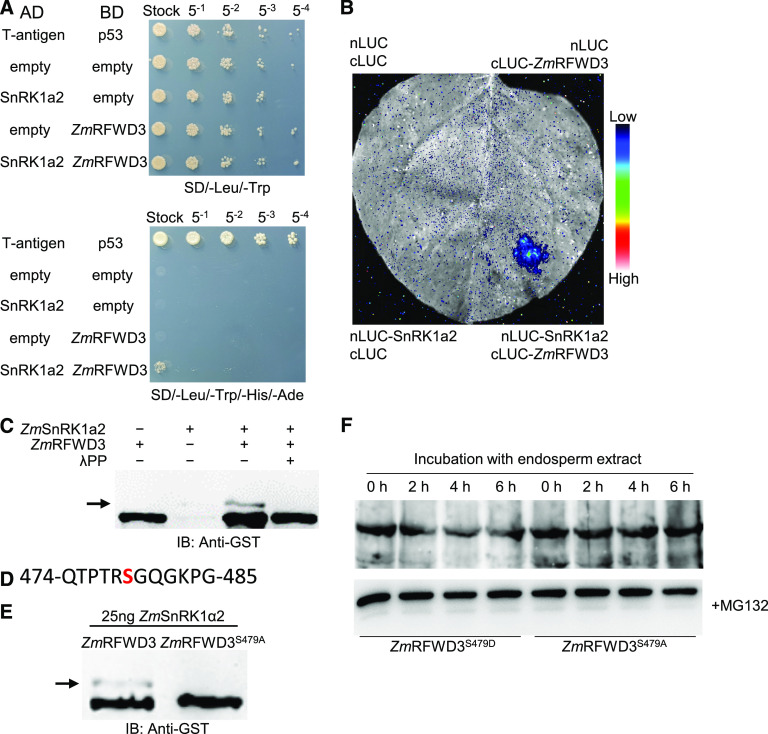

To further explore the idea of PTM-mediated regulation of ZmRFWD3, we used full-length ZmRFWD3 as bait in a Y2H screen to identify its potential PTM enzymes. Through this approach, we identified Z. mays SnRK1 α1-like 2 (ZmSnRK1α2) as an interacting protein of ZmRFWD3. We validated the interaction between ZmSnRK1α2 and ZmRFWD3 by LCI assays (Figures 6A and 6B). In addition, in vitro kinase assays showed that ZmSnRK1α2 can phosphorylate ZmRFWD3 (Figure 6C), and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis indicated that ZmRFWD3 S-479 is a site of ZmSnRK1α2-mediated phosphorylation (Figure 6D; Supplemental Figure 7). We subsequently mutated S-479 to Ala and performed in vitro kinase assays, which confirmed that ZmSnRK1α2 did phosphorylate ZmRFWD3 at this residue (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

ZmSnRK1a2 Phosphorylates ZmRFWD3 at Ser-479 To Regulate Its Stability.

(A) Y2H analysis of the interaction between ZmRFWD3 and ZmSnRK1α2. AD, GAL4 activation domain; BD, GAL4 DNA binding domain. To repress auto-activation, 10 mM of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) was added to the SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade plate.

(B) LCI assay showing the interaction between ZmRFWD3 and ZmSnRK1α2 in N. benthamiana leaves. The lower-right section shows the interaction signal; the three other sections show the signals of the negative controls. The specific combinations are labeled next to each section. The fluorescent signal intensity represents interaction activity.

(C) In vitro kinase assay showing GST-ZmRFWD3 can be phosphorylated by ZmSnRK1α2. ZmRFWD3′s phosphorylation was assayed in the presence or absence of His-tagged ZmSnRK1α2. The phosphorylated ZmRFWD3 was separated by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE and detected with anti-GST antibody. The dephosphorylation of ZmRFWD3 was determined by the addition of λ-protein phosphatase. The arrow indicates phosphorylated ZmRFWD3.

(D) The phosphorylated peptide detected by LC/MS. The “S” in red indicates the Ser residue shown to be phosphorylated.

(E) In vitro kinase assay validating the phosphorylation site of ZmRFWD3 by ZmSnRK1α2 determined by LC/MS. The Ser-479 site of GST-ZmRFWD3 was mutated to Ala and used as substrate. Phosphorylation was visualized by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. The arrow indicates phosphorylated ZmRFWD3.

(F) Extracts from 15-DAP wild-type seed endosperm were incubated at room temperature with GST-ZmRFWD3-S479D or GST-ZmRFWD3-S479A in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. GST-ZmRFWD3 protein levels were quantified by immunoblot analysis with anti-GST antibody.

Phosphorylation of a protein may result in its instability (Zhai et al., 2017). Next, we conducted semi-in vivo degradation assays using two purified recombinant forms of ZmRFWD3: the phospho-mimic ZmRFWD3S479D and the non-phosphorylatable ZmRFWD3S479A. Specifically, we incubated these two ZmRFWD3 variants separately with total protein extracts from 18-DAP seeds. ZmRFWD3S479D degraded faster than ZmRFWD3S479A, and the 26S proteasome inhibitor MG132 inhibited this degradation (Figure 6F; Supplemental Figure 8). These results indicate that phosphorylation of ZmRFWD3 leads to its degradation by the 26S proteasome.

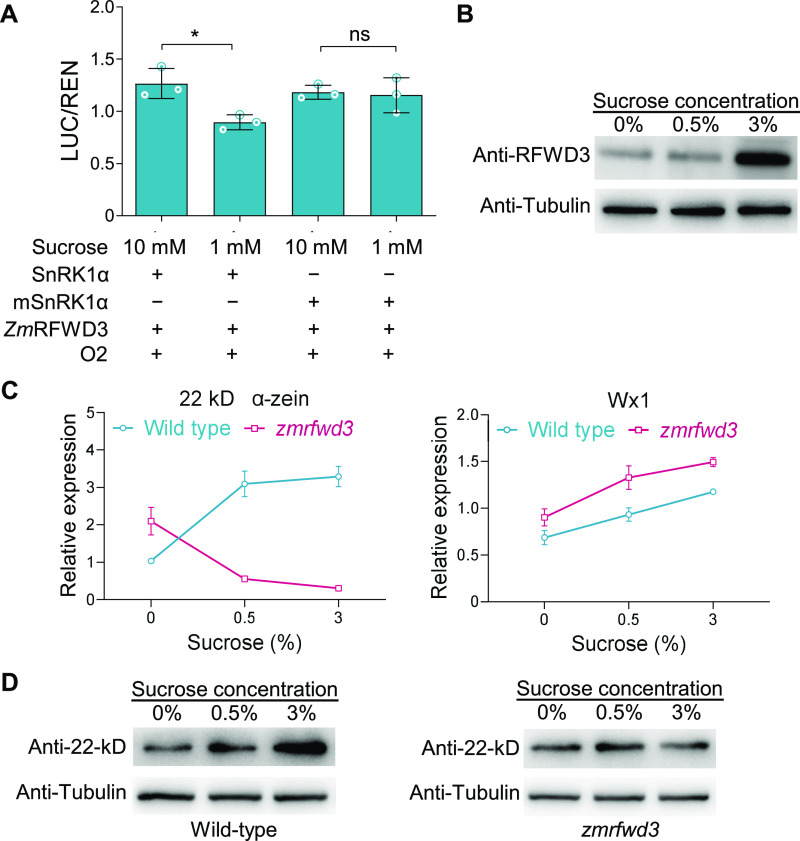

O2 Activity Responds to Suc Levels Through a SnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 Signaling Axis

Considering the known physiology of Suc accumulation and the strongly Suc-responding-based regulation of SnRK1 (Baena-González et al., 2007; Radchuk et al., 2010; Margalha et al., 2016), we next investigated whether ZmSnRK1 might regulate ZmRFWD3 and/or O2, as well as whether this regulation is dependent on Suc signaling. We performed dual-LUC activation assays in maize leaf protoplasts with a LUC reporter gene driven by the 22-kD α-zein promoter. ZmSnRK1α2 and ZmRFWD3 expression in these protoplasts were driven by the 35S cauliflower Mosaic Virus promoter, and we mutated the ZmSnRK1α2 active site to Ala (ZmSnRK1α2T176A) to block its kinase activity (Crozet et al., 2014). We treated the transformed protoplasts with 1- or 10-mM Suc to manipulate SnRK1 activity. The low Suc concentration strongly inhibited the activity of the reporter. This inhibition did not occur with the kinase-dead mutant ZmSnRK1α2T176A, indicating that low Suc concentration regulates O2 activity via SnRK1 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Suc Level Affects O2 Activity through ZmSnRK1α and ZmRFWD3.

(A) Dual-LUC transcription activation assay showing the activation of ZmSnRK1, ZmRFWD3, and O2 on the 22-KD zein promoter after high- and low-Suc treatments. The proteins and reporter construct were transiently expressed in maize leaf protoplasts by polyethylene-glycol–mediated transformation. Data are means (±sd). Three replicates were performed, each with five technical replicates. Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; **P < 0.01; ns, non-significant.

(B) ZmRFWD3 accumulation in endosperm cultured on medium containing various concentrations of Suc. Relative accumulation was determined by immunoblot analysis. Tubulin was used as an internal control with an anti-tubulin antibody.

(C) Relative expression of 22-kD α-zein (representing N accumulation) and Wx1 (representing C accumulation) in endosperm of wild-type and zmrfwd3 cultured in vitro on medium with various Suc concentrations, as determined by qPCR. The maize ubiquitin gene was used as an internal control.

(D) Accumulation of the 22-kD α-zein in seeds of wild-type and zmrfwd3 cultured on medium containing various concentrations of Suc. Relative accumulation was determined by immunoblot analysis. Anti-tubulin antibody was used as an internal control.

We next performed seed explant assays to determine whether Suc can affect O2 activity and N assimilation in seeds via a mechanism mediated by ZmRFWD3. We cultured wild-type seeds and zmrfwd3 seeds at 12 DAP in medium containing different concentrations of Suc. We observed that in wild type, ZmRFWD3 protein levels increase with higher Suc concentrations (Figure 7B). We further examined O2 activity in explants by measuring transcript levels of the 22-kD α-zein gene, using the starch synthesis gene Waxy-1 (Wx1) as control. In explants from wild-type seeds, the transcripts of the 22-kD α-zein gene (indicative of N status) and Wx1 (indicative of C status) both reached higher levels when the seeds were exposed to more Suc (Figure 7C). By contrast, in zmrfwd3 explants, the transcript levels of the 22-kD α-zein gene strongly decreased when seeds were treated with higher levels of Suc, whereas the transcription pattern of Wx1 was similar to that of the wild type (that is, transcription was higher at the higher Suc level; Figure 7C). Immunoblot analysis of the accumulation of 22-kD α-zein using an anti-22-kD α-zein antibody confirmed the trends observed in the quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis (Figure 7D). The results indicated that O2 activity is in response to Suc level changes, which is dependent on ZmRFWD3.

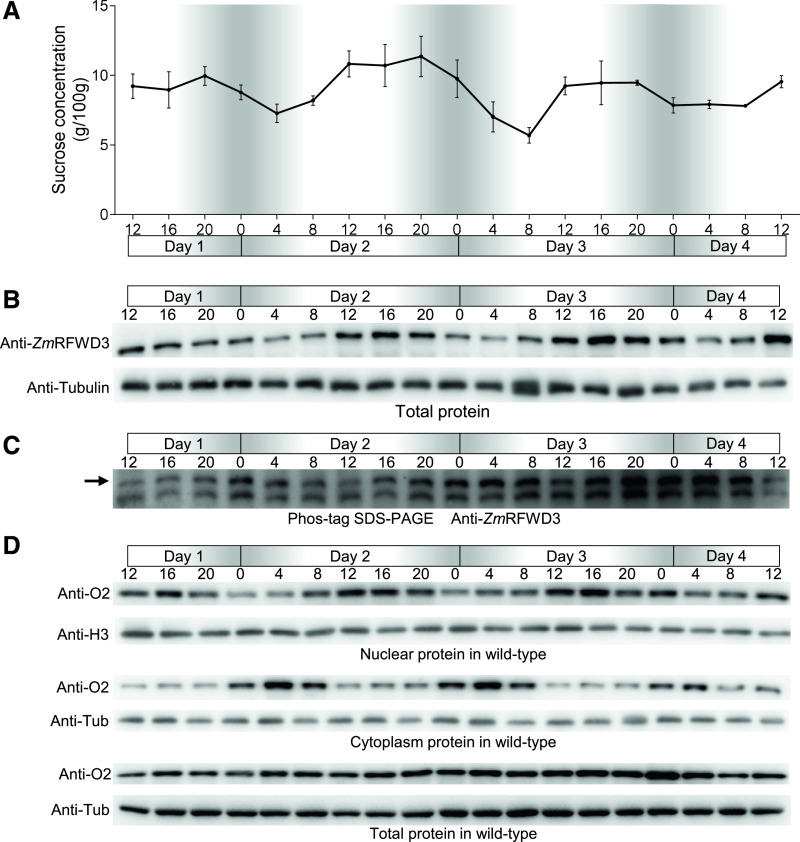

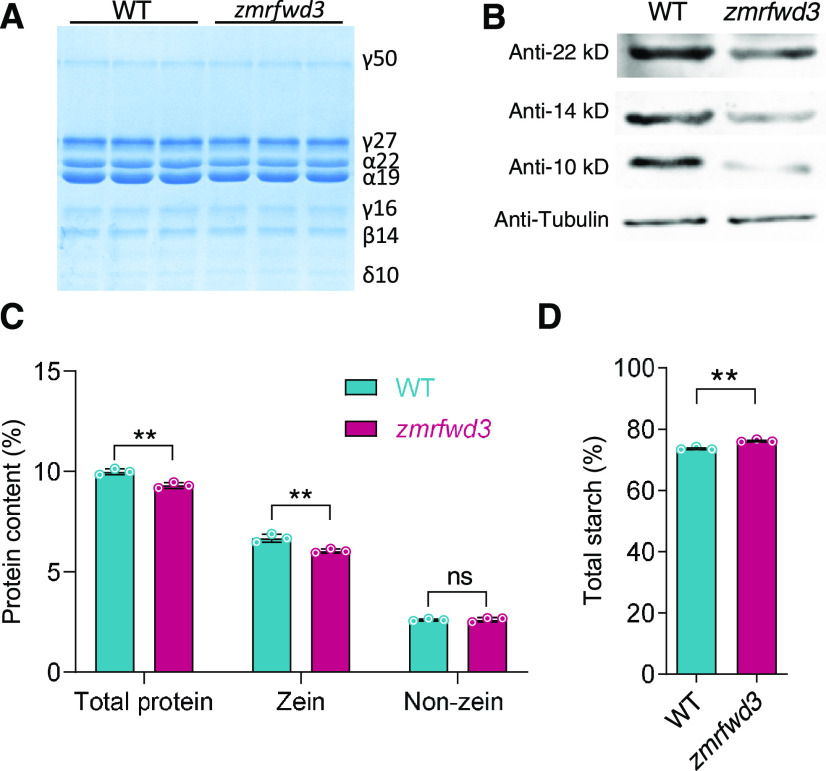

Suc, ZmRFWD3, and O2 Show Diurnal Rhythms during Endosperm Development

During maize endosperm development, Suc is the dominant C source for starch synthesis (Moutot et al., 1986), and previous studies in rice (Oryza sativa) have shown that the Suc concentration in the endosperm exhibits a diurnal rhythm, with a higher concentration during daylight and a lower concentration at night (Yu et al., 2012). We used ion chromatography (IC) to monitor the Suc concentrations of developing maize seeds every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP (from noon to noon) and also detected a diurnal rhythm in Suc concentrations, with higher concentrations during the day (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Suc, ZmRFWD2, and the Distribution of O2 Display Diurnal Rhythm in Endosperm.

(A) Suc concentration pattern in the endosperm of wild-type maize seeds extracted every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP. Black solid line indicates the diurnal rhythm of Suc concentration. The Suc concentration was normalized to dry weight. The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray. Error bars indicate means ± sd (n = 3).

(B) Protein accumulation pattern of ZmRFWD3 in the endosperm of wild-type maize seeds extracted every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP. Protein samples were normalized to tubulin levels with an anti-tubulin antibody. The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray.

(C) In vivo phosphorylation rate of ZmRFWD3, detected by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. Total protein was extracted every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP in the presence of phosphatase inhibitor and the proteasome inhibitor MG132. The arrow indicates phosphorylated ZmRFWD3. The phosphorylation rate was calculated as the ratio of signal of phos-ZmRFWD3 to ZmRFWD3. Three biological replicates were performed with similar results. The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray.

(D) Protein accumulation pattern (cytonuclear distribution) of O2 every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP in wild-type endosperm. The nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total proteins of wild-type endosperm were extracted. Tubulin was used to ensure equal loading (protein levels) in the total and cytoplasmic protein samples (with an anti-tubulin antibody); histone H3 was used to ensure equal loading in the nuclear samples (with an anti-H3 antibody). The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray.

Next, we sought to determine whether ZmSnRK1-ZmRFWD3 affects the diurnal rhythmic cytonuclear distribution of the O2 protein. We first tested the diurnal accumulation of ZmRFWD3 by immunoblotting analysis of total protein extracts from seeds harvested every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP (from noon to noon). ZmRFWD3 protein levels were higher during the day than at night (Figure 8B; Supplemental Figure 9). Furthermore, a Phos-tag immunoblotting assay clearly indicated that ZmRFWD3 was much more strongly phosphorylated at night than during the day (Figure 8C; Supplemental Figure 9).

We therefore used immunoblotting to measure O2 protein levels and cytosolic versus nuclear localization in developing seeds at 4-h intervals from 15 to 18 DAP. Strikingly, although O2 showed no obvious rhythm at the level of total protein content, it tended to accumulate in the nucleus during the day (8 am to 4 pm) but in the cytoplasm at night (Figure 8D). These results indicate that Suc concentration, the protein level of ZmRFWD3, and the cytonuclear distribution of O2, all follow distinct diurnal rhythms and these rhythms are in correspondence with the signaling process described in vitro.

Zein Displays Different Diurnal Patterns at the Transcriptional and Translational Levels

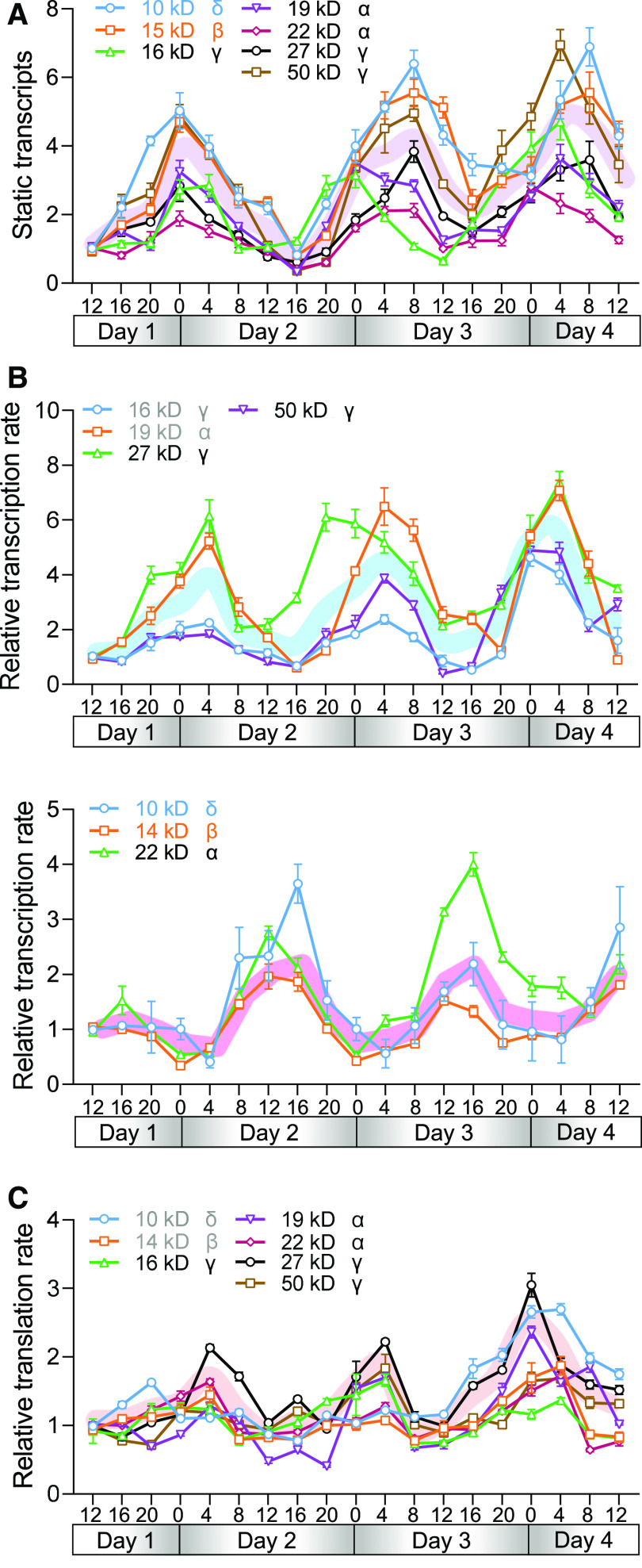

Considering that O2 shows a diurnal pattern in its nuclear localization, and that O2 is a master regulator of zein transcription, we used qPCR to assess each of the seven major classes of zein genes present in maize in developing endosperm, with the aim of assessing any diurnal patterns in their expression. Specifically, we harvested seeds from the same maize cob every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP (noon-to-noon). The expression of all of the tested genes followed an apparently diurnal rhythm, with significantly higher transcript levels at night (10 pm to 8 am) than during the day (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Zein Gene Expression Displays Different Diurnal Rhythm Patterns at the Transcriptional and Translational Levels.

(A) to (C) qPCR showing the numbers of static transcripts (A), nascent transcripts (B), and transcripts undergoing translation (C) of zein-coding genes every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP. Numbers of static transcripts were calculated using total RNA, numbers of nascent transcripts were calculated using run-on RNA analysis, and numbers of transcripts under translation were calculated using polysome RNA. Bold lines indicate the mean y-axis values of the genes tested that had the same diurnal rhythm. The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray. Error bars indicate means ± sd (n = 3).

Next, seeking to determine whether these changes in zein mRNA accumulation resulted from increased transcription or from some other aspect of RNA metabolism (e.g., altered RNA degradation dynamics), we used RNA run-on assays (Yu et al., 2019) to quantify the transcriptional rate of nascent transcripts from these zein-coding genes. We validated the RNA isolated by the run-on method by the detection of the positive control genes maize Dark-induced gene6 (Baena-González et al., 2007) and Wx1 (Harmer et al., 2000; Supplemental Figures 10A and 10B). The transcription rates of all zein genes followed a diurnal rhythm. However, there were two distinct patterns of transcriptional regulation: the 22-kD δ-, 14-kD β-, and 10-kD α-zein genes, which are strictly regulated by O2 (Li et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2018), showed higher transcription rates during the day, whereas the other zein-coding genes were transcribed at a higher rate at night (Figure 9B). For example, the 22-kD α-zein gene was transcribed at a rate ∼2 times higher at 4 pm than at 4 am, whereas the 19-KD α-zein gene was transcribed at a rate ∼4 times higher at 4 am than at 4 pm (Supplemental Figure 11).

We also isolated polysome-occupied RNAs from the same samples, which facilitated the profiling of the transcripts being actively translated. The translation of all seven zein classes showed a weak diurnal trend, with a higher translation rate at night (Figure 9C).

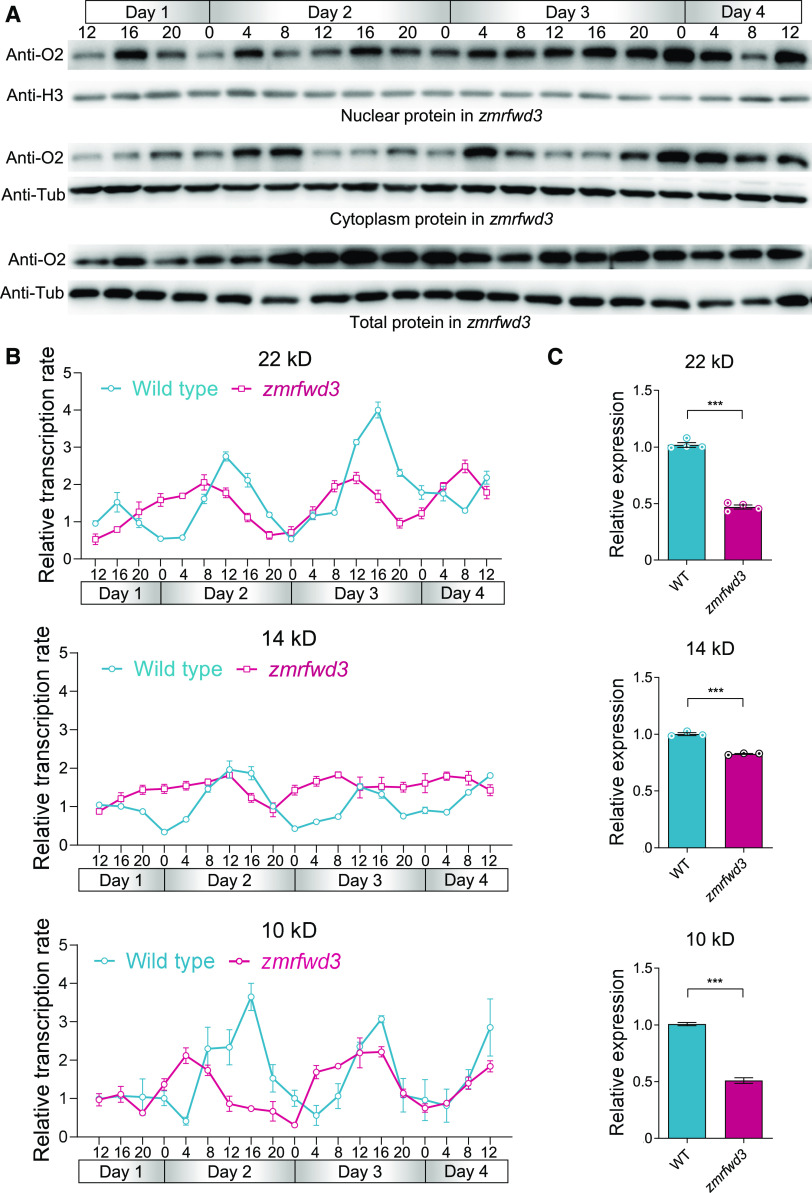

ZmRFWD3 Loss of Function Disrupts Zein Transcription and Seed Nutrient Reservoirs

We next determined the diurnal rhythm of O2 distribution in zmrfwd3 seeds every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP. Despite the absence of ZmRFWD3, the O2 distribution in the cytoplasm showed a weak diurnal rhythm. However, we noted that O2 diurnal accumulation in nuclei was disordered in zmrfwd3 compared with wild-type seeds (Figures 10A and 8C; Supplemental Figure 12). Prompted by our observation that ZmRFWD3 enhances O2 transcriptional activation, we used RNA run-on assays to quantify the transcription of the 22-, 14-, and 10-kD zein-coding genes in zmrfwd3 mutant seeds, as they are strictly regulated by O2. The transcription of these genes exhibited a weaker diurnal trend in the mutant relative to the wild type (Figure 10B). At static transcript levels, all three genes show lower expression in the zmrfwd3 mutant (Figure 10C).

Figure 10.

Loss of Function of ZmRFWD3 Alters the Diurnal Rhythm of O2 Cytonuclear Distribution and Zein Biosynthesis.

(A) Protein accumulation pattern and cytonuclear distribution of O2 at 15 to 18 DAP in zmrfwd3 endosperm. The nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total proteins of endosperm from wild-type plants were extracted every 4 h. Total protein samples were normalized to tubulin, and nuclear and cytoplasmic protein samples to histone H3 and tubulin, respectively. The sampling times are indicated for each day, in 4-h intervals. Day 1, 15 DAP; Day 4, 18 DAP. Midnight = “0”; the night periods are indicated in gray.

(B) qPCR results showing the transcription rates of positive control O2 target genes and 10-kD, 14-kD, and 22-kD zein genes every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP. Transcription rates were calculated by run-on RNA analysis.

(C) Static transcripts of 22-kD, 14-kD, and 10-kD zein genes are lower in the zmrfwd3 mutant. The seeds used were sampled at noon, 18 DAP. Data are values from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate means ± sd (n = 9). Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; ***P < 0.001; ns, non-significant.

We verified the reduction of zein protein content in the mature mutant by SDS-PAGE (Figure 11A): an immunoblot analysis indicated that the most pronounced reductions occurred for the 10-, 14-, and 22-kD zeins (Figure 11B). We observed no apparent or visible phenotypic differences between zmrfwd3 and wild-type seeds. Characterization of the protein and starch accumulation patterns in mature zmrfwd3 endosperm indicated that the total protein content and zein protein content were both slightly lower in the mutant, whereas the starch content was slightly higher (Figures 11C and 11D). These results indicated that the loss of function of ZmRFWD3 decreases the biosynthesis of storage protein (N) and thus elevated the proportion of C in the seed nutrient pool, resulting in an altered C/N ratio.

Figure 11.

Loss of Function of ZmRFWD3 Alters Nutrient Accumulation in Maize Seeds.

(A) SDS-PAGE detection of zein accumulation in mature zmrfwd3 maize seeds. WT, wild type.

(B) Immunoblot detection of zein accumulation in mature kernels of zmrfwd3.

(C) Comparison of total, zein, and non-zein proteins from endosperm of wild-type and zmrfwd3 kernels. The measurements are based on w/w % of dried endosperm. Error bars indicate means ± se (n = 3). Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; **P < 0.01; ns, non-significant.

(D) Comparison of total starch content in wild-type and zmrfwd3 mature endosperm. Endosperm from 20 mature kernels each of the wild type and zmrfwd3 from the same segregating ear were pooled as one replicate. Three biological replicates were performed using three different segregating ears. The measurements were w/w % of dried endosperm. Error bars indicate means ± se (n = 3). Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test; **P < 0.01; ns, non-significant.

DISCUSSION

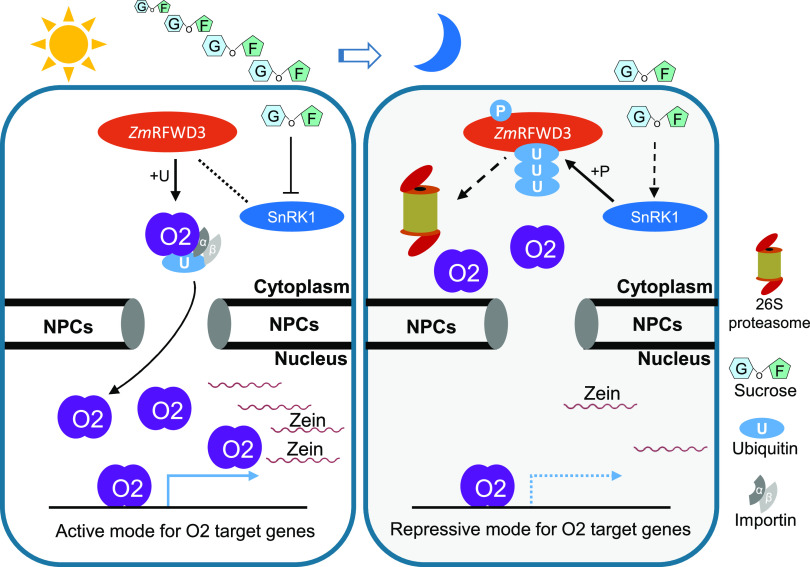

Our findings provide insight into the diurnal rhythm of nutrient accumulation in developing crop seeds. Suc levels showed a distinct diurnal rhythm in developing maize endosperm. Moreover, ZmSnRK1, which responds to Suc (Baena-González et al., 2007; Radchuk et al., 2010; Margalha et al., 2016), functions in a diurnal rhythmic fashion, negatively regulating the E3 ubiquitin ligase ZmRFWD3, resulting in a diurnal rhythm in ZmRFWD3 stability. When present in cells, ZmRFWD3 promotes the translocation of O2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in a mechanism similar to the mono-ubiquitination–mediated cytonuclear translocation of the human Phosphatase and tensin homolog PTEN (Trotman et al., 2007), thus enhancing O2 transcriptional activity. O2 is a known coordinator of C and N assimilation (Schmidt et al., 1987, 1990; Zhang et al., 2016). Our study thus establishes that Suc is a signal mediating the diurnal rhythm of nutrient accumulation in maize endosperm and shows that decreased Suc levels trigger a SnRK1-ZmRFWD3-O2 signaling axis that ultimately downregulates the transcription of genes functioning in zein biosynthesis (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Working Model for O2’s Cytonuclear Translocation Mediated by the SnRK1-ZmRFWD3 Pathway.

During the daytime, the high Suc concentration inhibits SnRK1 activity. O2 nuclear localization is enhanced by ZmRFWD3-mediated ubiquitination. At night, the low Suc concentration activates SnRK1. SnRK1 triggers ZmRFWD3 degradation via phosphorylation. O2 nuclear localization is inhibited. NPCs, nuclear pore complexes; U, ubiquitin; P, phosphate.

O2 is a TF with pleiotropic effects on endosperm development (Li et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2018). Studies on the regulation of O2 activity have been scarce because the early observation that O2 was modified via phosphorylation (Ciceri et al., 1997). Phosphorylation of O2 changes diurnally with a high phosphorylation ratio and low DNA binding activity at night, in contrast to its low phosphorylation ratio and high DNA binding activity during the day (Ciceri et al., 1997). O2 RNA abundance shows a diurnal rhythm (low at night, high during the day; Ciceri et al., 1999). In this study, we found that O2 cytonuclear distribution also shows a significant diurnal rhythm. The diurnal rhythms observed in O2 RNA abundance, the cytonuclear distribution of the O2 protein, and its DNA binding activity (phosphorylation levels) are consistent, and they all lead to the suppression of O2 function at night and its enhancement during the day, indicating that these modifications of O2 coordinate the diurnal rhythm in O2 activity, thereby securing the high efficiency of nutrient accumulation.

We further characterized a signaling axis, involving ubiquitination of O2, contributing to its cytonuclear shuttling. Mutation of ZmRFWD3 weakened the diurnal rhythm in O2 cytonuclear distribution, thus confirming the signaling axis in vivo. However, the effects observed in zmrfwd3 mutants are relatively subtle, suggesting that other pathways may operate in parallel to regulate O2 activity. O2 PTMs suggest that its regulatory patterns are of great complexity, which probably contributes to its pleiotropic roles in maize endosperm development. The molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of O2 phosphorylation is still largely unclear. Further studies may focus on O2 modifications by phosphorylation, as well as O2 poly-ubiquitination.

In Arabidopsis leaves, SnRK1 is required for Suc-induced changes in circadian phase (Mair et al., 2015; Frank et al., 2018). Here, we found that Suc levels in developing seeds follow a diurnal rhythm, with higher concentrations during the day than at night, consistent with a study in rice (Yu et al., 2012). Our study reveals that Suc-mediated diurnal regulation not only occurs in photosynthetic organs, but also in non-photosynthetic plant organs such as maize seeds. The diurnal rhythm of genes involved in other biological processes may also be regulated through changes in Suc concentration levels, SnRK1, or ZmRFWD3.

ZmRFWD3 interacts with its target O2 via its WD40 repeat domain, which is consistent with the case of CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 in Arabidopsis (Lau and Deng, 2012). We found that loss of function of ZmRFWD3 resulted in the absence of oligo-ubiquitinated O2, without eliminating its poly-ubiquitination, indicating that O2 is under ubiquitination-regulated control in vivo and that ZmRFWD3 specifically mediates the oligo-ubiquitination of O2. ZmRFWD3 is homologous to the human protein RFWD3. In normal human cells, the RFWD3 target p53 is polyubiquitinated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mouse double minute2 (MDM2), which maintains its protein abundance low. In response to DNA damage, RFWD3 is activated by the checkpoint kinases ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and ataxia-telangiectasia mutated–related through phosphorylation and forms a complex with MDM2 and p53 that synergizes with MDM2 to induce the mono-ubiquitination of p53. This process stabilizes and enhances p53 levels in response to DNA damage (Haupt et al., 1997; Fu et al., 2010). In maize, ZmRFWD3 retained oligo-ubiquitination activity toward its target O2. This ubiquitination can enhance O2 transactivation activity by promoting its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. It is not known whether ZmRFWD3 cooperates with some other E3 ubiquitin ligases that mediate O2 poly-ubiquitination, as is the case for RFWD3 and MDM2 in the case of p53 ubiquitination in humans, nor is it known whether ZmRFWD3 participates in DNA-damage responses in maize.

O2 is a dominant regulator of the 10-kD δ-zein, 14-kD β-zein, and 22-kD α-zein genes but only a co-regulator of the 19-kD α-zein, and 27- and 50-kD γ-zein genes (Li et al., 2015). The transcription rates of 10-kD δ-zein, 14-kD β-zein, and 22-kD α-zein showed a diurnal rhythm, with high transcription rates during the day and low transcription at night. This is consistent with the diurnal rhythm of O2 activity. However, other zein encoding genes, which are regulated by TFs other than O2, showed inverse patterns relative to the 10-kD δ-zein, 14-kD β-zein, and 22-kD α-zein genes. These inverse patterns, determined by run-on analysis, may be caused by rhythmic signaling axes other than the one involving O2. The total abundance of the mature RNAs of all of these zein-coding genes is higher at night and lower during the day; further study will thus be required to decipher the post-transcriptional regulation of zein RNAs. Pelechano et al. (2015) showed that most mRNAs are co-translationally degraded. Our characterization of polysome-occupied mRNA transcripts from zein genes showed that these shared similar diurnal patterns with total RNA, suggesting that zein RNAs may be subject to decay when polysome occupation level is low during the daytime.

At the early stage of seed filling (16 to 18 DAP), loss of function of ZmRFWD3 disrupted the diurnal rhythm of the transcription of the 10-kD δ-zein, 14-kD β-zein, and 22-kD α-zein genes, and significantly reduced their RNA abundance. However, the reduction of zein protein accumulation in the mature seed is less than expected. Perhaps diurnal regulation of O2 is most important during the early stages of seed filling, but less so later. Even though O2 plays a fundamental role in N assimilation in the sink organ that is the seed, its role in C assimilation may be limited. In our explant assays, transcript levels for Wx1, the gene encoding a starch-synthesis–related enzyme, were not affected in zmrfwd3 seeds, suggesting that there may be other pathways regulating C assimilation in developing endosperm in addition to the pathway involving O2.

The starch and protein contents in common maize varieties are stable, at ∼72% and ∼10% of total seed weight, respectively (Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1992), suggesting that there are complex internal balancing mechanisms for C and N. The use of efficient N fertilizers has contributed considerably to the significant increase in maize yield in recent decades (Ciampitti and Vyn, 2013), suggesting that N affects C assimilation. On the other hand, many seed mutants related to sugar utilization, such as brittle-2 and shrunken-2, both of which result in low starch content, also decrease zein synthesis (Tsai, 1983), suggesting that C can likewise affect N assimilation. Zeins, however, contain more C by mass than N. The fraction of C sourced from imported Suc itself may also be the basis of zein biosynthesis. The signaling axis in this study links high-level zein biosynthesis to Suc availability, which may be important to ensure that zein biosynthesis does not become a metabolic drain on endosperm cells. Suc, which is a major substrate for starch biosynthesis, can enhance zein production, also providing a mechanism for how C affects N assimilation. In the effort to breed special maize hybrids, such as those with an extremely high level of protein or starch, manipulating the signaling axis identified in this study may be a feasible approach. If the balance of starch and protein in maize seed can be manipulated, this may be used to further improve crop yield without the need for added N fertilizer.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The maize (Zea mays) inbred line W22 and the HiII maize transformation parental lines, Parent A and Parent B, used for the generation of maize transgenic lines, were obtained from the Maize Genetics Cooperation Stock Center (http://maizecoop.cropsci.uiuc.edu/) and maintained in our laboratory.

Maize plants were grown in the field at the Shanghai University campus (backcrossing; April 2012 to 2017) or in uniformly-mixed Pindstrup substrate (www.pindstrup.com) in a glass greenhouse (diurnal pattern; 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod with 150 μmol/m2/s of supplemental light; heat: 28°C day/20°C night; October 2018) at the China Agricultural University campus. Wild-type Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in soil (1:1 of black soil/vermiculite) in a growth chamber at 22°C and 70% relative humidity under a 16-h light (white fluorescent lamp, 20,000 LUX)/8-h dark photoperiod for ∼4 to 5 weeks before infiltration. After infiltration, plants were returned to the same growth conditions.

Maize seeds were harvested at different time points between 15 and 18 DAP, immediately frozen in liquid N, and stored at −80°C for later RNA and protein extraction (Feng et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012). Tissue samples were collected from at least three individual plants for each development stage.

zmrfwd3 CRISPR-Cas9 transgenic lines were generated according to a previously published method using the simplex strategy (Qi et al., 2016a). The 20-bp target editing sequence is within the first exon of ZmRFWD3 (the 20-bp target sequence being GGAGATCTTGCCTAGAGAAG). Maize transformation by Agrobacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) followed the same procedure as for the simplex strategy. zmrfwd3-mu1 and zmrfdw3-mu2 were backcrossed to the W22 genetic background for at least three generations. Segregating F2 ears were used in this study.

Genotyping of zmrfwd3 Mutant Seeds Generated by CRISPR-Cas9

Genotyping was performed as previously described by Li et al. (2018). The CRISPR-Cas9-targeted site was amplified from genomic DNA with specific primers (Supplemental File 3), and the PCR product was analyzed by Sanger sequencing for genotyping.

RNA Extraction and qPCR

We extracted total RNA from developing seeds using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit, which is optimized for polysaccharides and polyphenolics-rich samples (cat. no. DP441; Tiangen). Total RNA of other tissues was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (cat. no. DP432; Tiangen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (cat. no. FSQ-201; Toyobo). Primer pairs for qPCR were all designed using the software Quantiprime (http://www.quantprime.de), with the maize UBIQUITIN gene (GenBank Accession Number: BT018032) as internal control.

For qPCR, the reaction mixture was composed of first-strand cDNA templates (equivalent starting total RNA: 5 ng per reaction), primer mix, and SYBR Green Mix (cat. no. QPK-201; Toyobo) in a final volume of 20 μL. The reactions were run on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Three biological replicates were performed using seeds from three F2 ears. The data were analyzed by the ∆∆Ct method, as previously described by Zhang et al. (2012).

Nuclear Run-on Assay

Nuclear run-on assays were performed as previously described by Meng and Lemaux (2003), Ding et al. (2012), and Yu et al. (2019). Briefly, we used 0.25 mM of biotin-16-UTP and 0.75 mM of ATP, CTP, and GTP (cat. no. 11685597910; Sigma-Aldrich) in the transcription reaction. The purified RNA was then bound to streptavidin magnetic beads (cat. no. 11205D; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative transcription rate of specific genes was determined on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) and quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt calculation. The maize UBIQUITIN gene was used as internal control. Primers used are shown in Supplemental File 3.

Polysomal RNA Isolation

We isolated polysomal RNA as previously described by Qi et al. (2016b). Briefly, ∼2 mL of pulverized tissue powder (∼20 kernels at 15 DAP) was hydrated in 2 vol of polysome extraction buffer (200 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 9.0, 200 mM of KCl, 25 mM of EGTA, 35 mM of MgCl2, 1% [w/v] Brij-35, 1% [v/v] Triton X-100, 1% [v/v] Tween 20, 1% [v/v] Igepal CA-630, 1% [w/v] deoxycholic acid, 1% [v/v] polyethylene-10-tridecylether, 1 mM of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.5 mg mL−1 of heparin, 5 mM of DTT, 50 μg mL−1 of cycloheximide, and 50 μg mL−1 of chloramphenicol), homogenized, filtered through two layers of sterile Miracloth (Calbiochem), and cleared by centrifugation (16,000g, 4°C for 15 min). The supernatant was then layered over a 1.75-M Suc cushion (400 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 9.0, 200 mM of KCl, 30 mM of MgCl2, 1.75 M of Suc, 5 mM of DTT, 50 μg mL−1 of chloramphenicol, and 50 μg mL−1 of cycloheximide) and centrifuged at 170,000g at 4°C for 3 h. The polysome pellet was washed with sterile water and resuspended in 700 μL of polysome extraction buffer without heparin or detergents. Total or polysome-bound RNA was precipitated from total supernatant or from the ribosome fraction of the same amount of sample powder by the addition of 2.5 vol of 8 M of guanidine chloride and 3.5 vol of 99% (v/v) ethanol and extracted using an Plant RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Protein Extraction

Preparation of total protein for immunoblotting from developing seeds and other tissues was previously described by Bernard et al. (1994). Briefly, the tissues were homogenized in liquid N and then resuspended in equal volume of lysis buffer in 2-mL tubes (60 mM of Tris-Cl at pH 6.8, 1.5% [w/v] SDS, 4% [v/v] 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% [w/v] Suc, 1 mM of PMSF, and 1% plant cocktail [v/v]; Sigma-Aldrich). After 20 min of incubation on ice, the tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to new tubes for SDS-PAGE analysis. Zeins and non-zeins were prepared from mature maize seeds as previously described by Wallace et al. (1990).

Polyclonal Antibody Preparation and Immunoblotting

To generate GST-tagged ZmRFWD3 protein, we PCR-amplified the full-length ZmRFWD3 ORF and cloned the PCR product at the EcoRI and SalI sites of pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare). The final construct was introduced into an Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) strain. Cells were grown at 37°C and protein production induced by the addition of isopropylthio-β-galactoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6. The recombinant GST-tagged ZmRFWD3 fusion protein was purified with the ÄKTA purification system (Cytiva) using a 1-mL GST crude column (GE Healthcare). The antibody was generated in rabbits by Abclonal (China) according to their standard protocol.

Immunoblot analysis was performed according to a method described by Wang et al. (2014). The anti-ZmRFWD3 antibody was used at a dilution of 1:800. The anti-O2 (Zhang et al., 2012) and anti-ubiquitin (cat. no. AS08-307; Agrisera) antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:2,500. Antibodies recognizing GST tag (cat. no. ab19256; Abcam), Myc tag (cat. no. M20002; Abmart), S tag (cat. no. ab183674; Abcam), α-tubulin (cat. no. AC025; Abclonal), H3 (cat. no. H0164-200UL; Sigma-Aldrich), Bip (cat. no. sc-33757; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and zeins (Yao et al., 2016) were used at a dilution of 1:5,000. The anti-ZmRFWD3, -O2, -ubiquitin, -GST tag, -S tag, -H3, -BiP, -tubulin, and -zeins antibodies were detected using a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. 12-348; Sigma-Aldrich). The anti-Myc tag antibody was detected using a goat anti-mouse IgG-conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. A3682-1ML; Sigma-Aldrich).

Domain Annotation and Phylogenetic Analysis

For domain annotation, the ZmRFWD3 protein sequence was characterized using the tool CDD/SPARCLE (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) with default parameters (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2017). The sequences for ZmRFWD3 homologues in other species were identified in the National Center for Biotechnology Information non-redundant protein database by performing a Basic Local Alignment Tool for Protein (BLAST; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) search with the ZmRFWD3 protein sequence as a query. Protein sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE method in the software MEGA5.2 (https://www.megasoftware.net/older_versions). Evolutionary distances were computed using a Poisson correction analysis. In the phylogenetic analysis, 1,000 bootstrap replicates were performed.

Y2H System

Y2H assays were performed as previously described by Zhang et al. (2012). The full-length O2 and ZmSnRK1α2 ORFs were cloned at the EcoRI and XhoI sites of the pGAD-T7 vector (Clontech) using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). The full-length ZmRFWD3, ZmRFWD3-RING, or ZmRFWD3-WD40 ORFs were cloned at the EcoRI and SalI sites of the pGBK-T7 vector (Clontech) using the same kit. The pGAD-T7-O2 and pGAD-T7-ZmSnRK1α2 vectors were co-transformed with pGBK-T7-ZmRFWD3 (RING/WD40) separately as prey and bait vectors into the yeast reporter strain AH109. Yeast colonies were grown in liquid medium until the OD600 reached 0.5. The construct combinations AD+BD, AD+ZmRFWD3, and O2 (or ZmSnRK1α2) + BD were used as negative controls. The different yeast strains were grown on synthetic double drop-out (SD/-Leu/-Trp) and synthetic quadruple drop-out (SD/-Leu/-Trp/-Ade/-His) solid medium.

LCI Assay

The wild-type ZmRFWD3 and mutant mZmRFWD3 (ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A) ORF were cloned into JW771 (NLUC), while the O2 and ZmSnRK1α2 ORFs were cloned into JW772 (CLUC), yielding ZmRFWD3-CLUC/mZmRFWD3-CLUC and O2/ZmSnRK1α2-NLUC constructs for the LCI assay, following a protocol previously described by Chen et al. (2008).

Briefly, all constructs were introduced in Agrobacterium strain GV3101. The resulting colonies were grown in Luria-Bertani medium overnight at 28°C. The next day, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM of MES at pH 5.7, 10 mM of MgCl2, and 150 μM of acetosyringone) to a final cell density corresponding to OD600 of 1.0 before infiltration into the leaves of 5-week–old N. benthamiana plants. After growth for 48 h under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod, the leaves were injected with 1 mM of luciferin, and the resulting LUC signal was captured using a model no. 5200 Imaging System (Tanon). These experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Protein and Starch Measurement

Proteins were quantified as previously described by Smith et al. (1985) and Wallace et al. (1990). Total starch was measured using an Amyloglucosidase/α-Amylase Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and adapted as previously described by Feng et al. (2018).

To measure zein, non-zein, and total starch content, we pooled the endosperm of 20 mature seeds each, from the wild-type and zmrfwd3 genotypes, from the same segregating ear as one replicate. Three biological replicates were analyzed on seeds from three different segregating ears.

Co-IP

Total seed proteins were extracted by grinding in liquid N and resuspending the powder in extraction buffer (50 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 2.5 mM of EDTA, 150 mM of NaCl, 0.2% [w/v] NP-40, 20% [v/v] glycerol, 1 mM of PMSF, and 1% plant cocktail [v/v]; Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 20 min. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was centrifuged one more time at 12,000g for 5 min at 4°C. For co-IP, the protein lysate was incubated with 5 μL of rabbit anti-O2 antibody for 2 h. Next, the protein-antibody complex was incubated with 100 μL of Protein A Sepharose CL-4B (GE Healthcare) for 1 h. After four washes with extraction buffer, the complexes were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-O2 (1:2,500 dilution) and anti-ZmRFWD3 (1:800 dilution) antibodies. The anti-O2 and anti-ZmRFWD3 antibodies were detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. 12-348; Sigma-Aldrich).

Ubiquitination Assay

GST-ZmRFWD3, S-tag-O2, and mutations of O2 at Lys residues were overexpressed and purified from E. coli (DE3) Rosetta cultures using standard protocols. For in vitro ubiquitination assays, reaction mixtures (20 μL) contained 0.25 mg of human E1 enzyme (cat. no. UB101; LifeSensors), 0.2 mg of purified human E2 enzyme UBCH5C (cat. no. UB201; LifeSensors), 0.5 mg of purified GST-tagged ZmRFWD3 protein as the E3 ubiquitin ligase, 0.2 mg of purified S-tag-O2 as substrate, and 1 mg of ubiquitin (Sigma-Aldrich) in 25 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1 mM of MgCl2, 1 mM of ATP, and 0.5 mM of DTT. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 3 h and stopped by adding Laemmli buffer and boiling for 10 min. Ubiquitination was detected by anti-S-tag antibody at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. ab183674; Abcam). A self-ubiquitination assay was performed using the same protocol without S-tag-O2, and GST-ZmRFWD3′s self-ubiquitination was detected with anti-GST antibody at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. ab19256; Abcam). The anti-S-tag and anti-GST tag antibodies were detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a dilution of 1:5,000 (cat. no. 12-348; Sigma-Aldrich).

Dual-LUC Transient Transcriptional Activity Assay

To generate a p22 kD:LUC reporter for dual-LUC assays, a 500-bp promoter fragment upstream of the transcription start site of the 22-KD α-ZEIN gene was inserted at the HindIII and BamHI sites of pGreenII-0800 using a ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech). 35S:O2, 35S:ZmRFWD3, and 35S:ZmSnRK1α2 effectors were created by cloning their coding sequences at the HindIII and XbaI sites of the pHB vector using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit. The empty vector was used as a negative control. We performed transient dual-LUC assays in the leaves of 5-week–old N. benthamiana plants and measured LUC activity with dual-LUC assay reagents (cat. no. E1960; Promega). We calculated the ratio between LUC and Renilla luciferase (REN) activities with at least three biological replicates from three leaves.

Subcellular Localization

The full-length O2 ORF was cloned into the transient expression vector pSAT6-EYFP-N1 at the EcoRI and SalI sites. Living onion (Allium cepa) epidermal cells were peeled and incubated on Murashige and Skoog medium in the dark for 8 h. One microgram of plasmid with each construct was used to coat 0.3 mg of 1.0-μm–diameter tungsten particles and was bombarded into onion cells with a Biolistic PDS-1000/He system (Bio-Rad). The bombarded samples were incubated in the dark for 12 h before observation using a confocal laser microscope (model no. LSM710; Zeiss).

Fractionation of Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Proteins

Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were fractionated as previously described by Qi et al. (2016b). Pulverized tissue was hydrated in cold harvest buffer (10 mM of HEPES at pH 7.9, 50 mM of NaCl, 0.5 mM of Suc, 0.1 mM of EDTA, 0.5% [v/v] Triton X-100, 1 mM of DTT, 10 mM of tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 100 mM of NaF, 17.5 mM of β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM of PMSF, 4 μg mL−1 pf aprotinin, and 2 μg mL−1 of pepstatin A) and incubated on ice for 5 min, after which the nuclei were pelleted (1000g, 4°C for 10 min). After the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube for extraction of cytoplasmic proteins, the nuclei pellet was washed and resuspended in buffer A (10 mM of HEPES at pH 7.9, 10 of mM KCl, 0.1 mM of EDTA, 0.1 mM of EGTA, 1 mM of DTT, 1 mM of PMSF, 4 μg mL−1 of aprotinin, and 2 μg mL−1 of pepstatin A) and pelleted again (1000g for 10 min). Nuclei were then washed and resuspended in buffer C (10 mM of HEPES at pH 7.9, 500 mM of NaCl, 0.1 mM of EDTA, 0.1 mM of EGTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40 [v/v], 1 mM of DTT, 1 mm of PMSF, 4 μg mL−1 of aprotinin, and 2 μg mL−1 of pepstatin A), vortexed (4°C for 15 min), pelleted again (14,000g, 4°C for 10 min), and transferred to a new tube for extracting nuclear proteins.

Y3H and o-Nitrophenyl-β-d-Galactoside Assays

To construct the Y3H plasmids, we PCR-amplified and recombined full-length ZmIMP1 coding sequence into the MCS I location of the pBridge vector at the EcoRI-BamHI sites, resulting in Bait I. To construct Bait II and Bait mII, ZmRFWD3 and mZmRFWD3 (ZmRFWD3C111A,C114A) were PCR-amplified and recombined into the MCS II location of Bait I at the NotI-BglII sites. O2-pGADT7 was used as prey. Bait and prey vectors were co-introduced into yeast strain AH109 and incubated at 30°C for 3 to 5 d, when yeast cells of equal optical density were plated out on selective medium. A qualitative evaluation was performed of the interaction activity between bait and prey.

o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside assays were conducted as described in Kippert (1995) with minor modifications. Yeast cells were collected and resuspended in 800 μL of Z-buffer (60 mM of Na2HPO4, 40 mM of NaH2PO4, 10 mM of KCl, 1 mM of MgSO4, and 50 mM of β-mercaptoethanol at pH 7.0) and placed on ice. β-Galactosidase assays were conducted after equilibration at 30°C for 15 min; 160 μL of 4 mg mL–1 o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside was added and the mixture was thoroughly vortexed before being incubated at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 400 μL of 1 M of Na2CO3, and the OD420 values after various incubation periods were determined. Three biological replicates were performed, each with four technical replicates.

In Vitro Kinase Assay and Phos-Tag Immunoblot Analysis

The ZmSnRK1α2 ORF was cloned into the pCold-tf vector. His-tagged ZmSnRK1α2 was overexpressed and purified from E. coli (DE3) Rosetta cell cultures carrying pCold-tf-ZmSnRK1α2, using standard protocols. For ZmSnRK1α2 in vitro kinase assays, 20-μL reaction conditions were set as follows: 1× SnRK1 kinase buffer (50 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 10 mM of MgCl2, and 1 mM of DTT), 10 μM of ATP, 250 ng of His-tagged ZmSnRK1α2, and 250 ng of GST-tagged ZmRFWD3, and the reactions were incubated for 35 min. After incubation, phosphorylated ZmRFWD3 was separated by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE (40 μM of Phos-tag; Wako Chemicals) and immunoblotted with anti-GST antibody.

For Phos-tag immunoblotting of maize seed protein, total proteins were extracted with the same extraction buffer used for co-IP with PhosSTOP (inhibitor tablets for phosphatase; Roche). Proteins were then separated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel with 40 mM of Phos-tag (Wako Chemicals USA) and 25 mM of MnCl2 at a current of 15 mA. Immunoblot analysis was performed according to the instructions provided by Wako Chemicals.

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) was performed by the Mass Spectrum Laboratory of China Agricultural University. After an in vitro kinase assay, the samples were dialyzed with 8 M of urea, reductively alkylated with 40 mM of iodoacetamide, and digested with Trypsin at 37°C overnight. After desalting with Sep-Pak cartridges (Waters), phosphopeptides were enriched with TiO2 and analyzed with a Q Exactive LC-MS/MS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS/MS spectra were analyzed with the software ProteomeDiscoverer v.2.1 (https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/OPTON-30959?SID=srch-srp-OPTON-30959).

Semi-In Vivo Protein Degradation Analysis

For semi-in vivo protein degradation assays, GST-tagged ZmRFWD3, ZmRFWD3S479D, and ZmRFWD3S479A were purified from Escherichia coli as described above. The three groups of samples were incubated with total protein extracted from 15-DAP endosperm with extraction buffer at room temperature (25°C) under agitation in an Thermomixer (Eppendorf), with or without the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (final concentration = 100 μM). Samples were collected at different time points, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 to 10 min before immunoblot analysis.

Transient Expression in Protoplasts

Maize protoplasts were prepared from leaves of 15-d–old maize seedlings and transformed as previously described by Yu et al. (2016). The isolated protoplasts were incubated in W5 solution (154 mM of NaCl, 125 mM of CaCl2, 5 mM of KCl, and 2 mM of MES at pH 5.7) supplemented with 1- or 10-mM Suc (Boudsocq et al., 2004). The protoplasts were then collected by centrifugation at 100g for 3 min at room temperature and subjected to dual-LUC assays (cat. no. E1960; Promega).

Quantification of Suc by IC

To prepare the Suc samples for IC analysis, we used the following method, adapted from Teixeira et al. (2012). Five maize seeds from each sample were ground in an analytical grinder and then freeze-dried for 10 h in a lyophilizer. Approximately 20 mg of powder was weighed in triplicate into 2-mL propylene microcentrifuge tubes with screw lids. Lipids were then extracted by adding 1 mL of petroleum ether; the tubes were then heated in a water bath at 42°C for 5 min under constant agitation. The samples were homogenized in a vortex and centrifuged at 16,100g for 10 min at room temperature. The petroleum ether phase was discarded. This procedure was repeated five times. After extracting lipids, we extracted soluble sugars by adding 1 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol to each tube and heating the samples in a boiling water bath for 5 min under agitation. Next, the samples were allowed to cool down to room temperature, then homogenized and centrifuged at 16,100g for 5 min at room temperature. The alcohol solution was collected in a 10-mL beaker. This procedure was repeated three times. After extraction of sugars, the beaker was placed in a chamber at 48°C until all the solvent had evaporated, and sugars were resuspended in 1 mL of distilled water and used for IC analysis.

Suc concentration was determined with a Dionex ICS-5000+ Chromatography System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The samples were diluted 1:40 with water, filtered through a 0.1-μm syringe filter, and separated on a Dionex CarboPac PA10 BioLC (4 × 250 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) column preceded by its guard column (4 × 50 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 1 mM of potassium hydroxide. The flow rate was 1 mL/min and the column temperature was 35°C.

Explant Assays

Ears at 12 DAP were sterilized with 95% (v/v) ethanol and then immersed for 5 min in 5% bleach (v/v) in a laminar-flow hood. A scalpel was used to cut out a triangular section with six kernels attached. Blocks with six attached kernels were placed in plastic Petri dishes, three blocks per plate, containing medium supplemented with various Suc concentrations. The plates were incubated in a dark growth chamber at 28°C. Medium was prepared essentially as previously described by Cheng and Chourey (1999) and supplemented with 1 mg/L of 2,4-D. All medium was adjusted to pH 5.8 before the addition of agar (2.5 g/L) and Phytagel (2 g/L). After autoclaving, streptomycin sulfate (10 mg/L) was filter-sterilized into the medium. After 5 d, kernels from the same treatment were pooled together, and RNA and protein were extracted from these samples as described above. Statistical analysistables for all Student’s t tests are shown in Supplemental File 4.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: ZmRFWD3 (DAA42852, GRMZM2G085691); O2 (NM_001111884, GRMZM2G015534); ZmIMP1 (AFW81448, GRMZM2G088088); ZmSnRK1a2 (DAA39374, GRMZM2G180704); Ubiquitin (BT018032); 10-kDa δ-zein (AF371266); 14-kDa β-zein (M12147, GRMZM2G086294); 16-kDa γ-zein (AF371262, GRMZM2G060429); 19-kDa α-zein (M12146, AF546188.1); 22-kDa α-zein (NM_001112529, GRMZM2G044625); 27-kDa γ-zein (AF371261, GRMZM2G138727); and 50-kDa γ-zein (BT062750, GRMZM2G138689).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. RING domain conservation in the GRMZM2G085691 gene product.

Supplemental Figure 2. The WD40 domain, but not the RING domain of ZmRFWD3, interacts with O2.

Supplemental Figure 3. CRISPR-Cas9–based gene editing of ZmRFWD3.

Supplemental Figure 4. Screening for the O2 ubiquitination site through an in vitro ubiquitination assay.

Supplemental Figure 5. O2 still interacts with mutated ZmRFWD3 through the RING domain.

Supplemental Figure 6. Quantitative analysis of the luminescence intensities shown in Figure 4C.

Supplemental Figure 7. LC-MS/MS analysis showing that ZmRFWD3 Ser-479 is phosphorylated.

Supplemental Figure 8. Protein degradation patterns of GST-ZmRFWD3S479D or GST-ZmRFWD3S479A incubated with extracts from 15-DAP wild-type endosperm in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132.

Supplemental Figure 9. Patterns of protein accumulation and phosphorylation ratio of ZmRFWD3 in the endosperm of wild-type maize seeds extracted every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP.

Supplemental Figure 10. Diurnal rhythm of levels of nascent transcripts of control genes with diurnal rhythm and ZEIN genes with two different diurnal patterns.

Supplemental Figure 11. Transcription rates of the 19- and 22-kD α-zein genes at 4 pm and 4 am (total of d1 to d4).

Supplemental Figure 12. Patterns of protein accumulation of nuclear O2 in the endosperm of wild-type and zmrfwd3 maize seeds extracted every 4 h from 15 to 18 DAP.

Supplemental File 1. Alignment file used for the phylogenetic analysis shown in Figure 2B.

Supplemental File 2. Newick format of the phylogenetic tree.

Supplemental File 3. Primers used in this study..

Supplemental File 4. Student’s t test tables.

DIVE Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

We thank Yingying Xing, Huiling Ling, and Ding Lu (Shanghai University) for their technical support in generating transgenic maize plants. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31730065, 91935305, and 31425019 to R.S.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2016YFD0101003 to R.S.), and the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (grant BX201700283 to C.L.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.L. and R.S. designed the research; C.L., Z.L., and X.Y. performed the research; C.L., R.S., W.Q., and Z.M. analyzed the data; C.L. and R.S. wrote the article; all authors read and approved the final article.

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Baena-González E., Rolland F., Thevelein J.M., Sheen J.(2007). A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448: 938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard L., Ciceri P., Viotti A.(1994). Molecular analysis of wild-type and mutant alleles at the opaque-2 regulatory locus of maize reveals different mutations and types of O2 products. Plant Mol. Biol. 24: 949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M., Barbier-Brygoo H., Laurière C.(2004). Identification of nine sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases 2 activated by hyperosmotic and saline stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 41758–41766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zou Y., Shang Y., Lin H., Wang Y., Cai R., Tang X., Zhou J.-M.(2008). Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 146: 368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W.H., Chourey P.S.(1999). Genetic evidence that invertase-mediated release of hexoses is critical for appropriate carbon partitioning and normal seed development in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 98: 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampitti I.A., Vyn T.J.(2013). Grain nitrogen source changes over time in maize: A review. Crop Sci. 53: 366–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri P., Gianazza E., Lazzari B., Lippoli G., Genga A., Hoscheck G., Schmidt R.J., Viotti A.(1997). Phosphorylation of opaque2 changes diurnally and impacts its DNA binding activity. Plant Cell 9: 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri P., Locatelli F., Genga A., Viotti A., Schmidt R.J.(1999). The activity of the maize Opaque2 transcriptional activator is regulated diurnally. Plant Physiol. 121: 1321–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozet P., Margalha L., Confraria A., Rodrigues A., Martinho C., Adamo M., Elias C.A., Baena-González E.(2014). Mechanisms of regulation of SNF1/AMPK/SnRK1 protein kinases. Front Plant Sci 5: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies R.J., Joazeiro C.A.P.(2009). RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78: 399–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Fromm M., Avramova Z.(2012). Multiple exposures to drought ‘train’ transcriptional responses in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 3: 740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle F.R., Curtis J.J., Hubbard J.E.(1946). Composition of the component parts of the corn kernel. Cereal Chem. 23: 504–511. [Google Scholar]

- Faleiros R.R.S., Seebauer J.R., Below F.E.(1996). Nutritionally induced changes in endosperm of shrunken-1 and brittle-2 maize kernels grown in vitro. Crop Sci. 36: 947–954. [Google Scholar]

- Feng F., Qi W., Lv Y., Yan S., Xu L., Yang W., Yuan Y., Chen Y., Zhao H., Song R.(2018). OPAQUE11 is a central hub of the regulatory network for maize endosperm development and nutrient metabolism. Plant Cell 30: 375–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Zhu J., Wang G., Tang Y., Chen H., Jin W., Wang F., Mei B., Xu Z., Song R.(2009). Expressional profiling study revealed unique expressional patterns and dramatic expressional divergence of maize alpha-zein super gene family. Plant Mol. Biol. 69: 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1992). Chapter 2: Chemical composition and nutritional value of maize. In Maize in Human Nutrition. (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; ). [Google Scholar]

- Frank A., Matiolli C.C., Viana A.J.C., Hearn T.J., Kusakina J., Belbin F.E., Wells Newman D., Yochikawa A., Cano-Ramirez D.L., Chembath A., et al. (2018). Circadian entrainment in Arabidopsis by the sugar-responsive transcription factor bZIP63. Curr. Biol. 28: 2597–2606.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Yucer N., Liu S., Li M., Yi P., Mu J.J., Yang T., Chu J., Jung S.Y., O’Malley B.W., et al. (2010). RFWD3-Mdm2 ubiquitin ligase complex positively regulates p53 stability in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 4579–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich D., Prehn S., Laskey R.A., Hartmann E.(1994). Isolation of a protein that is essential for the first step of nuclear protein import. Cell 79: 767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer S.L., Hogenesch J.B., Straume M., Chang H.S., Han B., Zhu T., Wang X., Kreps J.A., Kay S.A.(2000). Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science 290: 2110–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt Y., Maya R., Kazaz A., Oren M.(1997). Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 387: 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon M.J., Mielczarek O., Robertson F.C., Hubbard K.E., Webb A.A.R.(2013). Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature 502: 689–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding D.R., Larkins B.A.(2009). Zein storage proteins In Molecular Genetic Approaches to Maize Improvement. (New York, NY: Springer; ), pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Holding D.R., Messing J.(2013). Chapter 8: Evolution, Structure, and Function of Prolamin Storage Proteins In Seed Genomics, Becraft P.W., ed (New York, NY: Wiley Online; ), pp. 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ingle J., Beitz D., Hageman R.H.(1965). Changes in composition during development and maturation of maize seeds. Plant Physiol. 40: 835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippert F.(1995). A rapid permeabilization procedure for accurate quantitative determination of β-galactosidase activity in yeast cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 128: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappe R.R., Baier J.W., Boehlein S.K., Huffman R., Lin Q., Wattebled F., Settles A.M., Hannah L.C., Borisjuk L., Rolletschek H., et al. (2018). Functions of maize genes encoding pyruvate phosphate dikinase in developing endosperm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115: E24–E33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau O.S., Deng X.W.(2012). The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 17: 584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Qiao Z., Qi W., Wang Q., Yuan Y., Yang X., Tang Y., Mei B., Lv Y., Zhao H., Xiao H., Song R.(2015). Genome-wide characterization of cis-acting DNA targets reveals the transcriptional regulatory framework of opaque2 in maize. Plant Cell 27: 532–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Yue Y., Chen H., Qi W., Song R.(2018). The ZmbZIP22 transcription factor regulates 27-kD γ-zein gene transcription during maize endosperm development. Plant Cell 30: 2402–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair A., Pedrotti L., Wurzinger B., Anrather D., Simeunovic A., Weiste C., Valerio C., Dietrich K., Kirchler T., Nägele T., et al. (2015). SnRK1-triggered switch of bZIP63 dimerization mediates the low-energy response in plants. eLife 4: e05828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Bo Y., Han L., He J., Lanczycki C.J., Lu S., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R., et al. (2017). CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (D1): D200–D203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalha L., Valerio C., Baena-González E.(2016). Plant SnRK1 kinases: Structure, regulation, and function. Exp Suppl 107: 403–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méchin V., Thévenot C., Le Guilloux M., Prioul J.L., Damerval C.(2007). Developmental analysis of maize endosperm proteome suggests a pivotal role for pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase. Plant Physiol. 143: 1203–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Lemaux P.G.(2003). A simple and rapid method for nuclear run-on transcription assays in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 21: 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mertz E.T., Bates L.S., Nelson O.E.(1964). Mutant gene that changes protein composition and increases lysine content of maize endosperm. Science 145: 279–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroianu J., Blobel G., Radu A.(1995). Previously identified protein of uncertain function is karyopherin alpha and together with karyopherin beta docks import substrate at nuclear pore complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 2008–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]