Abstract

Introduction

The gold-standard treatment for symptomatic anterior skull base meningiomas is surgical resection. The endoscope-assisted supraorbital “keyhole” approach (eSKA) is a promising technique for surgical resection of olfactory groove (OGM) and tuberculum sellae meningioma (TSM) but has yet to be compared with the microscopic transcranial (mTCA) and the expanded endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) in the context of existing literature.

Methods

An updated study-level meta-analysis on surgical outcomes and complications of OGM and TSM operated with the eSKA, mTCA, and EEA was conducted using random-effect models.

Results

A total of 2285 articles were screened, yielding 96 studies (2191 TSM and 1510 OGM patients). In terms of effectiveness, gross total resection incidence was highest in mTCA (89.6% TSM, 91.1% OGM), followed by eSKA (85.2% TSM, 84.9% OGM) and EEA (83.9% TSM, 82.8% OGM). Additionally, the EEA group had the highest incidence of visual improvement (81.9% TSM, 54.6% OGM), followed by eSKA (65.9% TSM, 52.9% OGM) and mTCA (63.9% TSM, 45.7% OGM). However, in terms of safety, the EEA possessed the highest cerebrospinal fluid leak incidence (9.2% TSM, 14.5% OGM), compared with eSKA (2.1% TSM, 1.6% OGM) and mTCA (1.6% TSM, 6.5% OGM). Finally, mortality and intraoperative arterial injury were 1% or lower across all subgroups.

Conclusions

In the context of diverse study populations, the eSKA appeared not to be associated with increased adverse outcomes when compared with mTCA and EEA and offered comparable effectiveness. Case-selection is paramount in establishing a role for the eSKA in anterior skull base tumours.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00701-020-04544-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery, Microscopic transcranial surgery, Supraorbital keyhole, Skull base surgery, Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma, Olfactory groove meningioma

Introduction

The gold standard treatment for symptomatic anterior skull base meningiomas is complete surgical resection—if possible to do so without causing significant morbidity. Although the traditional microscopic transcranial approach (mTCA) has proven to be effective at removing such tumours [84, 86], minimally invasive surgical approaches may offer the possibility of reducing brain exposure and manipulation, and therefore increasing safety [105]. However, these less invasive techniques are often technically challenging with steep learning curves [105]. Factors influencing case-by-case surgical decision-making include the preservation of olfaction and vision, tumour size and location, the involvement of neurovascular structures, surgical experience, and patient choice [24, 86].

A previous comprehensive meta-analysis comparing the traditional mTCA and the expanded endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) found similar gross total resection (GTR) and mortality rates, with more favourable visual outcomes but higher cerebrospinal (CSF) leak incidence with EEA [84]. This generally corroborates with findings from other systematic reviews in the field [24, 59, 110]. However, a third approach—the endoscope-assisted supraorbital “keyhole” approach (eSKA)—has yet to be compared with mTCA and EEA in the context of existing literature. This approach includes multiple variations (such as the medial supraorbital, basal supraorbital, and lateral supraorbital approaches) that are unified by the principle of achieving surgical control of a deep-seated lesion whilst minimizing iatrogenic injury to the brain (via exposure, retraction, and manipulation) [102, 107]. This is achieved through using smaller craniotomies with smaller dural openings and may theoretically reduce post-operative complications and length of stay, whilst improving cosmesis, patient satisfaction and carrying lower CSF leak rates than the EEA [102, 104, 105, 107]. However, important limitations of the eSKA include (a) difficult visualization and orientation of deep structures, (b) difficult (almost co-axial) instrument control owing to instrument size and the fulcrum effect (requiring specialized instruments), and (c) limited and predefined surgical corridors which require extensive pre-operative planning [102, 107]. Endoscope assistance provides a high light intensity with wider viewing angles distal to the craniotomy, allowing high-resolution visualization of deeper tissues. Indeed, combined with image-guidance systems and intra-operative adjuncts (e.g. ultrasound, MRI), endoscopes facilitate surgical orientation and resection during keyhole approaches [102, 107].

Therefore, we updated a previous systematic review and meta-analysis comparing mTCA with EEA and extended this review with the eSKA for the management of olfactory groove (OGM) and tuberculum sellae meningiomas (TSM).

Methods

In order to identify studies reporting on outcomes of surgically treated TSMs and OGMs, we adapted our previous methodology [84], expanding our search to include eSKA and updating our search to include mTCA and EEA articles published after our last search.

Search strategy

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [81]. A search strategy was created using the keywords “Meningioma,” “Tuberculum Sellae,” “Olfactory Groove,” and synonyms (Appendix A). Studies were included if they reported on (1) patients with olfactory groove (OGM) or tuberculum sellae (TSM) meningiomas; (2) patients undergoing surgery using the mTCA, EEA or eSKA approaches; and (3) surgical outcomes and complications. Exclusion criteria included case reports, commentaries, congress abstracts, reviews, animal studies, studies describing a combined surgical approach (for example EEA + mTCA), studies in paediatric patients (< 18 years old), re-operations, and cadaveric studies. A date filter was applied, with articles from 2004 to 2020 being included—reflecting a period of the contemporary adaptation of endoscopic and keyhole approaches and the continuous improvement of traditional microsurgical approaches for the relevant pathologies [11, 15, 32, 106].

Both PubMed and Embase databases were searched on 19 April 2020. Duplicates were removed using Endnote X9. Independent title and abstract screening of updated results was performed in duplicate by two authors (DZK, HJM). Review of full-text articles ensued according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies in selection were settled out by discussion and mutual agreement.

Data extraction

Data points extracted from the included articles comprised of patient characteristics (age, sex distribution), tumour characteristics (surgical approach used, sum of sample, tumour grade, tumour diameter or volume, follow-up length), outcomes (GTR, visual improvement), and complications (CSF leak, 30-day mortality, intra-operative arterial injury). World Health Organization (WHO) grading included recording the proportion of WHO Grade 1 tumours [72]. Of note, the grading system was revised in 2016 to include brain invasion as a criterion to upgrade Grade 1 tumours to Grade 2 [72]. Therefore, if any studies pre-2016 reported brain invasion amongst Grade 1 tumours, the respective tumours were upgraded accordingly [72]. Gross total resection (GTR) referred to Simpson Grades 1 and 2 as per our original methodology [84, 116]. Visual improvement was in the context of those with preoperative visual problems only. Mortality (within 30 days after resection) was recorded on an all-cause basis.

Owing to the not uncommon reporting of follow-up time as a median number of months (as opposed to mean), the estimated mean number of months was calculated as per recommendations of Hozo et al. [53]. Of note, in sample sizes greater than 25, the sample’s median follow-up is presented as the best estimate of the mean [53].

Importantly, studies that did not report specific outcomes for OGM/TSM and approach combination were excluded from the final meta-analysis. These studies were considered for qualitative analysis if the relevant the tumour (TSM or OGM) and approach (mTCA, EEA, or eSKA) combination of interest was > 50% of the study population [9, 48, 98, 105, 111]. Similarly, articles that grouped TSM cases with planum sphenoidale meningiomas [3, 92] were considered for qualitative review only (owing to the similarity of these tumour groups) but not included in the final meta-analysis.

Risk of bias assessment

Study quality was assessed with a modified New-Castle Ottawa Scale (mNOS), which assesses two domains: sample selection and outcome reporting. The modification made to the original NOS was the exclusion of the “comparability” domain as this is not applicable to case series [126]. The scale is scored out of 6 (3 for selection domain, 3 for outcome domain). Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s tests [8] and by generating funnel plots with and without trim-and-fill method [34].

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted using R 3.6.1 (The R Foundation, Austria) applying the “meta” package. Pooled incidence (using the random-effect model method of DerSimonian and Laird [33]) was calculated for each approach (eSKA, mTCA, EEA), tumour (TSM, OGM), and outcome (GTR, arterial injury, visual improvement, CSF leakage, and mortality) combination. Study heterogeneity was assessed by calculating I-squared values [52] (I2 > 50% considered significant) and Cochran’s Q test (p < 0.10) [36, 52]. Sensitivity analysis was performed by running the above analyses on a low risk of bias sub-group (mNOS score greater than or equal to 4).

Additionally, a univariate meta-regression was performed to explore the effect of mean age (continuous variable) and male percentage (continuous variable) on each approach, tumour, and outcome combination. Meta-regression was only performed if 8 or more studies were available for the outcome/approach/tumour combination being explored. This threshold was chosen (a deviation from the standard threshold of 10) on a pragmatic basis, to reflect the relative paucity of literature from the newer eSKA approach [51]. This threshold was also applied to the performance of Begg’s test, trim-and-fill analysis, and the generation of funnel plots.

Results

Search results

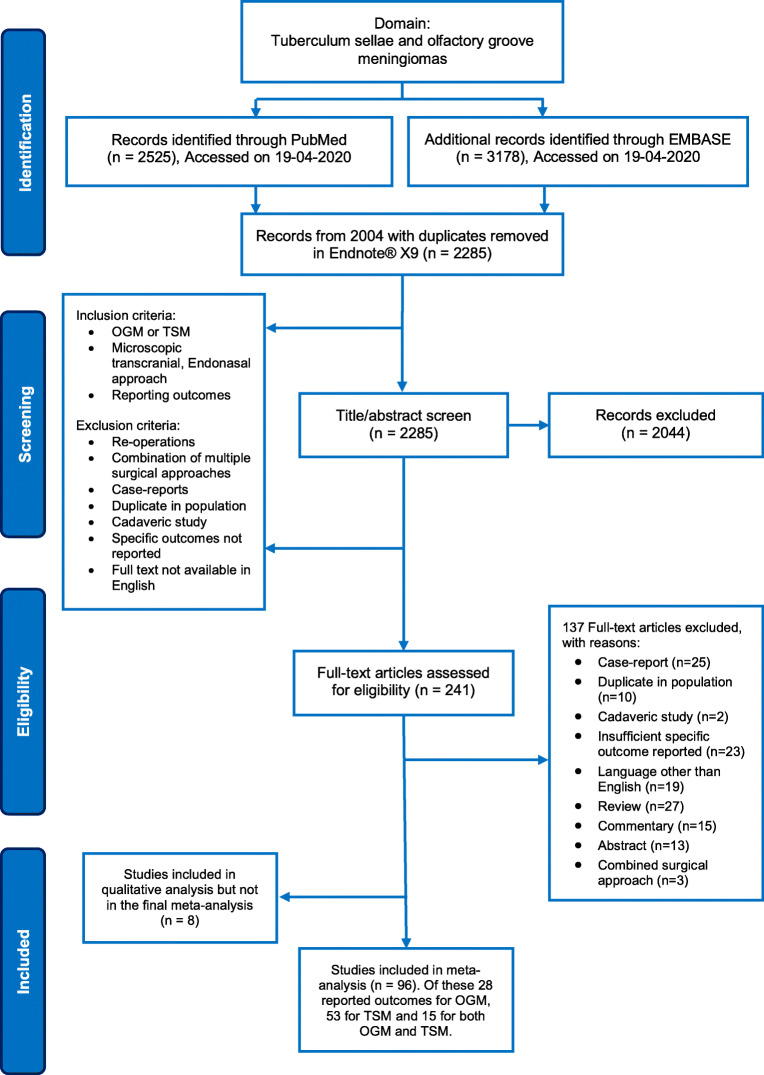

In all, after removing duplicates, 2285 articles were identified (Fig. 1). After screening for titles and abstracts, 2044 articles were excluded and 241 full texts were reviewed to yield 96 included studies. Fifty-three TSM-only case series were included in the meta-analysis of which 21 involved the EEA [3, 12, 13, 17, 19, 22, 37, 41, 49, 60, 61, 63, 67, 74, 91, 92, 120, 125, 131], 37 the mTCA [1, 3, 6, 13, 20, 21, 26, 29, 38, 43, 45, 55, 60, 63, 64, 66, 68, 74–76, 78, 79, 82, 85, 88, 92, 95, 97, 98, 108, 112, 114, 120, 124, 127, 130], and 5 the eSKA [16, 35, 41, 67, 78] with 10 of these papers covering multiple approaches [3, 14, 41, 60, 63, 67, 74, 78, 92, 120]. Twenty-eight OGM-only case series were included in the meta-analysis of which 5 involved EEA [4, 28, 62, 70, 92], 24 in mTCA [5, 7, 10, 23, 25, 27, 28, 40, 42, 44, 47, 56, 57, 70, 83, 87, 89, 96, 99, 101, 109, 117, 121, 123], 3 in eSKA [4, 39, 92], and with 4 of these studies detailing multiple approaches [4, 28, 70, 92]. Additionally, 15 studies explored both OGM and TSM [9, 30, 31, 50, 54, 58, 65, 93, 94, 103, 105, 113, 122, 128, 129]. Resultantly, the TSM group totalled 2191 patients and OSM group totalled 1519 patients (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart detailing search strategy and systematic article selection

Table 1.

Summary study characteristics for tuberculum sellae meningioma papers. WHO: World Health Organisation, mNOS: modified Newcastle Ottawa Score

| Endoscopic endonasal approach | Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | Microscopic transcranial approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Data unavailable | Amount | Data unavailable | Amount | Data unavailable | |

| Aggregate number of studies | 26 | - | 11 | - | 42 | - |

| Total number of patients | 540 | - | 128 | - | 1523 | - |

| Median mean age (years) | 54.4 | 4 studies | 57 | 1 study | 53.8 | 8 studies |

| Median male % | 25% | 4 studies | 16.7% | 2 studies | 23.4% | 5 studies |

| Median number of WHO grade 1 | 20 | 15 studies | 11.5 | 5 studies | 26.5 | 26 studies |

| Median mean tumour diameter (cm) | 2.5 (7 studies) | 9 studies | 2.9 (2 studies) | 2 studies | 2.5 (17 studies) | 17 studies |

| Median mean tumour volume (cm3) | 6.1 (10 studies) | 12.4 (7 studies) | 8.2 (8 studies) | |||

| Median mean follow-up (months) | 27 | 6 studies | 39.8 | 1 study | 39.5 | 5 studies |

| Median mNOS score | 4 | - | 5 | - | 4 | - |

Table 2.

Summary study characteristics for olfactory groove meningioma papers. WHO: World Health Organisation, mNOS: modified Newcastle Ottawa Score

| Endoscopic endonasal approach | Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | Microscopic transcranial approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Data unavailable | Amount | Data unavailable | Amount | Data unavailable | |

| Aggregate number of studies | 10 | - | 9 | - | 29 | - |

| Total number of patients | 115 | - | 96 | - | 1308 | - |

| Median mean age (years) | 53.1 | 1 studies | 59.2 | 1 studies | 54 | 4 studies |

| Median male % | 22.5% | 2 studies | 57.1% | 2 studies | 32.4% | 3 studies |

| Median number of WHO grade 1 | 9 | 5 studies | 8.5 | 7 studies | 48 | 13 studies |

| Median mean tumour diameter (cm) | 4 (1 study) | 4 studies | NA | 3 studies | 4.6 (15 studies) | 10 studies |

| Median mean tumour volume (cm3) | 33.3 (5 studies) | 24.8 (6 studies) | 42.5 (4 studies) | |||

| Median mean follow-up (months) | 35.3 | 2 studies | 5 | 1 studies | 54 | 1 studies |

| Median mNOS score | 4.5 | - | 45.1 | - | 4 | - |

General characteristics

The median number of patients per study was 20 (range: 3–95) for TSM and 19.5 (range: 2–129) for OGM. The average percentage of male patients was 24% for TSM and 31% for OGM. The median mean of age was 54.2 years for TSM and 54.75 years for OGM. The median mean of follow-up time for TSM was 32 months (reported in 55/67 studies) for and 44.5 months for OGM studies (reported in 39/43 studies). The modified NOS score varied between 2/6 and 6/6 amongst the TSM and OGM case series, with predominant factors affecting this variance being a description of follow-up and outcome reporting. Summary characteristics by approach (eSKA, EEA, or mTCA) are highlighted in Tables 1 and 2. Individual study characteristics are displayed in Tables 5 and 6 (Appendix B).

Gross total resection

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

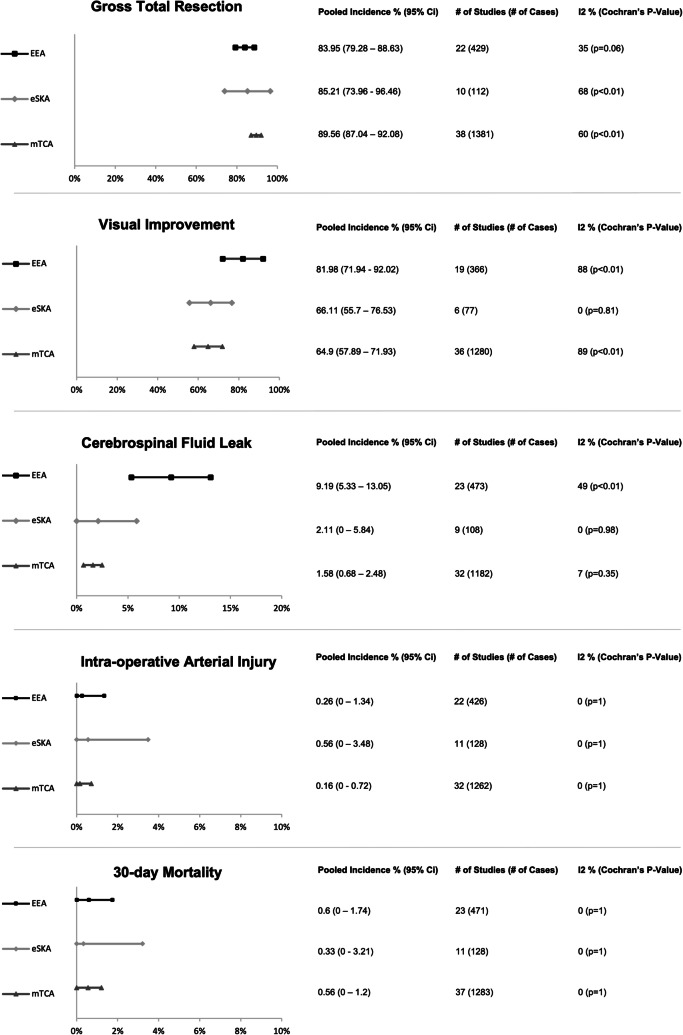

GTR was reported in 10 eSKA (112 patients), 22 EEA (429 patients), and 38 mTCA (1381 patients) studies. Pooled incidence of GTR (Fig. 2; Appendix C) was highest in the mTCA group at 89.56% (95% CI 87.04–92.08) followed by eSKA at 85.21% (95% CI 73.96–96.46) and EEA at 83.95% (95% CI 79.28–88.63). Study heterogeneity was significant within the eSKA (I2 = 68%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) and mTCA (I2 = 60%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) groups, with Begg’s test for publication bias also significant in this mTCA group (p < 0.01) (Table 3). This impacted funnel plot asymmetry, which was most marked in the mTCA group, without any major change in summary effect using trim and fill across subgroups (Appendix D). Meta-regression suggests male sex was significantly associated with lower GTR incidence in EEA (slope − 0.05 (95% CI − 0.96–0.04)) and mTCA (slope − 0.27 (95% CI − 0.53 to − 0.01)) subgroups (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Graphical display of pooled random effects per outcome metric for Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma. EEA: Expanded endonasal approach, eSKA: Endoscope assisted supra-orbital keyhole approach, mTCA: Microscopic transcranial approach, CI: Confidence Interval

Table 3.

Outcomes of the tuberculum sellae meningioma (TSM)—meta-regression based on age and male percentage. CI – confidence interval, NA – not available

| Outcomes in TSM | Begg’s test (p-value) | Meta-regression on age slope (95% CI) | Meta-regression on age (p-value) | Meta-regression on sex slope (95% CI) | Meta-regression on sex (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross total resection (Simpson Grade 1 Or 2) | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.32 | 0.003 (− 0.006–0.01) | 0.51 | − 0.5 (− 0.96–0.04) | 0.33 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | 0.32 | 0.03 (− 0.01–0.06) | 0.06 | − 0.75 (− 1.75–0.26) | 0.14 |

| Microscopic transcranial approach | < 0.01 | 0.001 (− 0.005–0.007) | 0.75 | − 0.27 (− 0.53 - − 0.01) | 0.04 |

| Visual improvement | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.67 | − 0.005 (− 0.01–0.005) | 0.36 | − 0.38 (− 0.82–0.06) | 0.09 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.35 | − 0.005 (− 0.02–0.01) | 0.57 | 0.11 (− 0.68–0.91) | 0.78 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.03 | − 0.001 (− 0.008–0.008) | 0.95 | − 0.04 (− 0.47–0.39) | 0.86 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | 0.21 | − 0.001 (− 0.01–0.01) | 0.83 | − 0.08 (− 0.47–0.31) | 0.7 |

| Microscopic transcranial approach | < 0.01 | 0.001 (− 0.003–0.004) | 0.75 | 0.07 (− 0.04–0.18) | 0.23 |

| Intra-operative arterial injury | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | < 0.01 | 0.001 (− 0.004 to − 0.004) | 0.88 | − 0.02 (− 0.21–0.17) | 0.84 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | 0.01 | − 0.001 (− 0.008–0.008) | 0.95 | 0.01 (− 0.33–0.35) | 0.95 |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | < 0.01 | − 9.53 (− 0.002–0.002) | 0.91 | − 0.006 (− 0.07–0.06) | 0.87 |

| 30-day mortality | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | < 0.01 | 0.002 (− 0.003–0.006) | 0.48 | 0.04 (− 0.18–0.26) | 0.74 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | < 0.01 | 0.001 (− 0.007–0.009) | 0.87 | − 0.02 (− 0.36–0.3) | 0.87 |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | < 0.01 | 0.001 (− 0.001–0.002) | 0.57 | − 0.001 (− 0.07–0.07) | 0.99 |

Olfactory groove meningioma

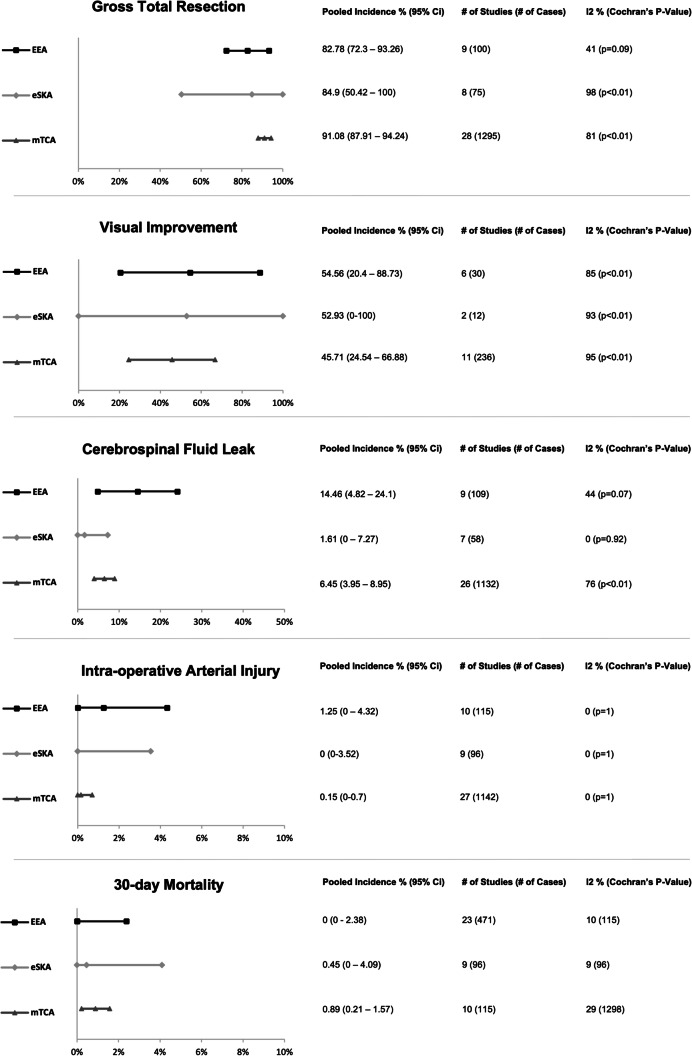

GTR incidence was reported in 8 eSKA (75 patients), 9 mTCA (100 patients), and 28 mTCA (1295 patients) studies. The pooled incidence of GTR (Fig. 3; Appendix C) was highest in the mTCA group with 91.08% (95% CI 87.91–94.24), followed by eSKA with 84.9% (95% CI 50.42–100) and EEA at 82.78% (95% CI 72.3–93.26). In terms of study heterogeneity, this was significant within the eSKA (I2 = 98%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) and mTCA (I2 = 81%, Cochran’s p <0.01) groups, with Begg’s test for publication bias also significant in this mTCA group (p < 0.01) (Table 4). These findings are similar to those of the TSM group. Funnel plot asymmetry was most marked in mTCA (reflective of heterogeneity and publication bias) and eSKA (likely reflective of heterogeneity groups). There was no major change in summary effect using trim-and fill-method across subgroups (Appendix D). In the eSKA subgroup, older age was associated with increased GTR on meta-regression (slope 0.05 (95% CI 0.02–0.08)) (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Graphical display of pooled random effects per outcome metric for Olfactory Groove Meningioma. EEA: Expanded endonasal approach, eSKA: Endoscope assisted supra-orbital keyhole approach, mTCA: Microscopic transcranial approach, CI: Confidence Interval

Table 4.

Outcomes of the olfactory groove meningioma (OGM): Meta-regression based on age and male percentage. CI - confidence interval, NA – Not available

| Outcomes in OGM | Begg’s test (p-value) | Meta-regression on age slope (95% CI) | Meta-regression on age (p-value) | Meta-regression on sex slope (95% CI) | Meta-regression on sex (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross total resection (Simpson Grade 1 Or 2) | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 1 | − 0.01 (− 0.02–0.01) | 0.45 | − 0.3 (− 1.34–0.74) | 0.58 |

| endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | 0.51 | 0.05 (0.02–0.08) | < 0.01 | − 0.28 (− 2.29–1.71) | 0.78 |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.01 | 0.01 (− 0.01–0.01) | 0.49 | − 0.01 (− 0.29–0.28) | 0.96 |

| Visual improvement | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.04 | − 5.07 (− 0.04–0.04) | 0.99 | 0.3 (− 3.3–3.9) | 0.87 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.48 | 0.03 (− 0.06–0.12) | 0.55 | − 0.47 (− 3.25–2.3) | 0.74 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.64 | − 0.002 (− 0.02–0.01) | 0.85 | 0.79 (0.2–1.38) | 0.01 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.01 | − 0.002 (− 0.009–0.005) | 0.51 | 0.001 (− 0.23–0.23) | 0.99 |

| Intra-operative arterial injury | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.02 | 0.001 (− 0.001–0.01) | 0.86 | 0.08 (− 0.29–0.44) | 0.68 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | NA | 0 (− 0.008–0.008) | 1 | 0 (− 0.24–0.24) | 1 |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.01 | − 4.56 (− 0.002–0.001) | 0.95 | − 0.01 (− 0.08–0.05) | 0.68 |

| 30-day mortality | |||||

| Expanded endonasal approach | 0.01 | 0 (− 0.01–0.01) | 1 | 0 (− 0.35–0.35) | 1 |

| Endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach | 0.01 | − 0.001 (− 0.008–0.007) | 0.97 | − 0.06 (− 0.33–0.21) | 0.66 |

| Microsopic transcranial approach | 0.01 | − 0.001 (-0.003–0.001) | 0.07 | − 0.09 (− 0.16–0.02) | 0.01 |

Visual improvement

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

Pre-operative visual impairment was reported in 6 eSKA (77 patients), 19 EEA (366 patients), and 36 mTCA (1280 patients) studies. The pooled incidence of visual improvement (Fig. 2; Appendix C) in the EEA group was 81.98% (95% CI 71.94–92.02) and was higher than the eSKA at 65.98% (95% CI 54.4–77.56) and mTCA at 63.9% (95% CI 57.15–70.65). However, study heterogeneity was significant within the EEA (I2 = 88%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) and mTCA (I2 = 89%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) groups. Publication bias was not evident on Begg’s testing, with mild funnel plot asymmetry in mTCA and EEA groups likely due to heterogeneity. This is supported by the lack of its major change in summary effect using trim-and-fill across subgroups (Appendix D). Meta-regression on age and sex did not reach statistical significance across mTCA, EEA, and eSKA groups (Table 3).

Olfactory groove meningioma

Pre-operative visual impairment was reported in 2 eSKA (12 patients), 6 EEA (30 patients), and 11 mTCA (236 patients) studies. The pooled incidence of visual improvement (Fig. 3; Appendix C) in descending order were as follows: EEA at 54.56% (95% CI 20.4–88.73), eSKA at 52.93% (95% CI 0–100) and mTCA with 45.71% (95% CI 24.54–66.88)—a similar pattern to the TSM group. Study heterogeneity was significant across all subgroups: EEA (I2 = 85%, Cochran’s p < 0.01), eSKA (I2 = 93%, Cochran’s p < 0.01), and mTCA (I2 = 95%, Cochrans p < 0.01). Publication bias was evident in the EEA cohort (Begg test, p = 0.04), with both this and the above heterogeneity contributing to the marked funnel plot asymmetry (Appendix D). Using the trim and fill method does not display a marked difference in summary effects (Appendix D). Meta-regression on age and sex did not reach statistical significance across subgroups (Table 4).

Cerebrospinal fluid leakage

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

Incidence of postoperative CSF leakage was reported in 9 eSKA (108 patients), 23 EEA (473 patients), and 32 mTCA (1182 patients) studies. The pooled incidence of CSF leak (Fig. 2; Appendix C) in the EEA group was 9.19% (95% CI 5.33–13.05), which was higher than the incidence observed among the eSKA treated group at 2.11% (95% CI 0–5.84) and mTCA treated group at 1.58% (95% CI 0.68–2.48). However, study heterogeneity (I2 = 49%, Cochran’s p < 0.01) and publication bias (Begg’s p=0.03) were significant in the EEA group. Publication bias was also evident in the mTCA group (Begg’s p ≤ 0.01). The asymmetry of mTCA and EEA funnel plots is explained by the above (Appendix D), but no major change in summary effect using the trim-and-fill method is appreciable in these groups. Meta-regression on age and sex did not reach statistical significance across any group (Table 3).

Olfactory groove meningioma

Incidence of post-op CSF leakage was reported in 7 eSKA (58 patients), 9 EEA (109 patients), and 26 mTCA (1132 patients) studies. Pooled incidence of CSF leak (Fig. 3; Appendix C) in the EEA group was 14.46% (95% CI 4.82–24.1), 6.45% in the mTCA group (95% CI 3.95–8.95), and 1.61% (95% CI 0–7.27) in the eSKA group. Study heterogeneity was evident in the mTCA group (I2 = 76%, Cochran’s p < 0.01), whilst publication bias was suggested in the mTCA (Begg’s p ≤ 0.01) and eSKA (Begg’s p = 0.03). Indeed, mTCA and eSKA funnel plots reflect this in their asymmetry (Appendix D). Meta-regression suggested male sex was associated with increased CSF leak in the EEA approach (slope 0.79 (95% CI 0.2–1.38)) (Table 4).

Intraoperative arterial injury

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

Incidence of intraoperative arterial injury was reported in 11 eSKA (128 patients), 22 EEA (426 patients), and 32 mTCA (1262 patients) studies. Pooled incidence (Fig. 2; Appendix C) in descending order were as follows: eSKA − 0.56% (95% CI 0–3.48), EEA − 0.26% (95% CI 0–1.34), and mTCA − 0.16% (95% CI 0–0.72). Across all 3 groups, study heterogeneity was not apparent; however, publication bias using Begg’s test reached statistical significance in eSKA (p = 0.01), EEA (p < 0.01), and mTCA (p < 0.01) groups—explaining funnel plot asymmetry across groups. Trim and fill adjustment, however, made almost no difference in overall summary effects (Appendix D). Meta-regression did not reveal significant associations for age and sex across all treatment groups (Table 3).

Olfactory groove meningioma

Incidence of intraoperative arterial injury was reported in 9 eSKA (96 patients), 10 EEA (115 patients), and 27 mTCA (1142 patients) studies. Pooled incidence (Fig. 3; Appendix C) was highest in the EEA group at 1.25% (95% CI 0–4.32), followed by the mTCA at 0.15% (95% CI 0–0.7) and eSKA with 0% (95% CI 0–3.52). Indeed, these results do not align with the TSM group. Across all 3 groups, study heterogeneity was not apparent; however, publication bias using Begg’s test reached statistical significance in EEA (p = 0.02) and mTCA (p < 0.01) groups, mapping to funnel plot asymmetry in EEA and mTCA groups. However, trim and fill adjustment made only minor differences to the estimated summary effect (Appendix D). Again, meta-regression did not show a significant effect of age and sex on arterial injury (Table 4).

30-day mortality

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

Incidence of mortality was reported in 11 eSKA (128 patients), 23 EEA (471 patients), and 37 mTCA (1283 patients) studies. Pooled incidence of 30-day mortality (Fig. 2; Appendix C) was 0.6% (95% CI 0–1.74) in the EEA group, followed by 0.56% (95% CI 0–1.2) in mTCA and 0.33% (95% CI 0–3.21) in eSKA in descending order. Across all 3 groups, study heterogeneity was not apparent; however, publication bias using Begg’s test reached statistical significance in all three groups (p < 0.01). Resultantly, the mTCA and eSKA funnel plots are asymmetrical but are not appreciably impacted in terms of summary effect by the implementation of trim and fill (Appendix D). Meta-regression did not show a significant effect of age and sex on mortality across subgroups (Table 3).

Olfactory groove meningioma

Incidence of mortality was reported in 9 eSKA (96 patients), 10 EEA (115 patients), and 23 mTCA (471 patients) studies. Unlike, the TSM population, pooled incidence of 30-day mortality (Fig. 3; Appendix C) was greatest in the mTCA group at 0.89% (95% CI 0.21–1.57), followed by the eSKA at 0.45% (95% CI 0–4.09) and EEA with 0% (95% CI 0–2.38). Across all 3 groups, study heterogeneity was not apparent; however, publication bias using Begg’s test reached statistical significance in all groups (p < 0.1), mapping to funnel plot asymmetry in EEA and mTCA groups (Appendix D). Trim and fill implementation did not result in any major adjustment to the estimated summary effect. Male sex appeared to be associated with higher 30-day mortality in the mTCA (slope − 0.09 (95% CI − 0.016–0.02)) (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis with low risk of bias studies

The pooled incidence of surgical outcomes of a subgroup of low-risk studies (defined as mNOS score greater than or equal to 4) is presented in Appendix E. This analysis, when compared with the total group analysis, yielded overall similar results for GTR, mortality, and intraoperative arterial injury. CSF leak incidence after EEA was apparently lower (in both OGM and TSM), and visual improvements after EEA (in the TSM group) were more marked in the lower risk of bias studies.

Discussion

Principle findings

In the context of heterogeneous study populations and outcome reporting, the endoscope-assisted supraorbital “keyhole” approach appeared to be associated with similar effectiveness (GTR, visual improvement) and safety (CSF leak, 30-day mortality) compared with the mTCA and EEA alternatives based on our findings. Case selection and an understanding of relative indications are important in selecting the most appropriate approach for anterior skull base meningioma resection.

As previously found, the EEA was associated with the highest rates of visual improvement across OGM and TSM groups. However, this advantage of EEA may be offset when considering the safety profile of the three approaches, with the EEA having the highest incidence of post-op CSF leak (statistically significant in the TSM sub-group). In contrast, the mTCA had a slightly higher incidence of GTR than eSKA and EEA (eSKA > EEA) across TSM and OGM groups. Interestingly, the eSKA displays intermediate results in terms of efficacy (GTR and visual improvement) and complications (CSF leak). Results for intra-operative arterial injury and 30-day mortality incidences are similar and overlapping across the 3 approaches. Indeed, the eSKA, as a relatively new technique, is less well explored. When compared with the mTCA, the eSKA—as a minimally invasive technique—offers a smaller craniotomy scar, less brain exposure, and less brain/nerve retraction [105]. Thus, theoretically, it shares similar limitations to the minimally invasive EEA [92]—potentially making total resection of larger tumours or tumours with significant local invasion difficult [24, 92, 105]. However, when performed with the benefit of neuronavigation, neuroendoscopy (12/13 of eSKA studies in our meta-analysis), and appropriate surgical training, the eSKA has been used to resect relatively large tumours of the anterior skull base [4, 41, 67, 105].

All 3 approaches likely have their own role in the management of anterior skull base meningiomas, with their varying safety and efficacy profiles as evidenced above. Case selection will be paramount in establishing a role for each technique/combination of techniques [4, 92, 105]. Indeed, case selection of eSKA is currently considerably variable, owing to its novelty and ongoing refinement [70, 92]. The selection of the preferred approach for each case must be taken in the context: (a) patient-related factors (demographic, presentation, preferences), (b) tumour-related factors (size, consistency, extension, location—such as relation to optic foramen or cribriform plate), and (c) surgeon experience, surgeon preference, and surgical goals (such as GTR or STR, visual or olfactory preservation) [2, 77, 92, 105, 118]. Ottenhausen et al. presents a concise decision-making algorithm (based on tumour anatomy and resulting functional deficits), which incorporates the specific characteristics of eSKA, EEA, and mTCA approaches [92]. In this algorithm, the eSKA is suitable for TSMs with lateral extension up to the internal carotid arteries (ICA) and anterior clinoid processes (ACP), or lateral extension beyond the lamina papyracea (LP). Additionally, the eSKA is suggested for OGMs with (1) preserved olfaction and (2) disrupted olfaction without cribriform plate invasion but with significant anterior (up to the frontal sinus) or lateral extension. In contrast, the EEA is proposed for TSM without significant lateral extension (ICA/ACP/LP as above) and OGMs without significant lateral extension (where olfaction is disrupted). Finally, an mTCA or a combined EEA + eSKA approach is suggested for OGMs and TSMs with a significant anterior or lateral extension (unless there is no cribriform plate invasion, in which case, eSKA alone may be possible) [92]. Of note, other algorithms cite > 5mm sellar extension and optic canal involvement as factors favouring EEA in TSM [60]. During EEA for TSM, decompression of the optic canal from below avoids excessive vascular manipulation, can be achieved before or after tumour resection, and is well suited to tumours with extension into the inferomedial aspect of the optic canal [2, 69]. Decompression of the involved optic canal is described in mTCA approaches with early decompression (before tumour resection) favoured [20, 80, 90]. In eSKA, studies describe both early and late bilateral canal decompression with optimum timing being less clear [16, 67]. More generally, within the literature, consensus for the ideal surgical approach in various contexts is not clear [41, 60, 67, 74, 92, 99]. Indeed, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic—which elucidated to the risk endonasal surgery may pose (exposing theatre staff to high viral loads and potentially serious infection)—this case selection process is likely to be a dynamic field in the near future [71, 100, 119].

Findings in the context of other syntheses

Previous meta-analyses have compared the EEA and mTCA (not eSKA) with varying results.

In terms of GTR, Muskens et al. (co-author) previously found higher GTR incidence with mTCA in OGM at 88.5% (CI 85.9–90.7%) versus EEA 70.9% (CI 60.3–79.9%) [84]—in line with our findings. This corroborates with other meta-analyses. Ruggeri et al. explored OGM and TSM, finding a higher GTR rate (p < 0.01) in mTCA (88.13%) than EEA (78,42%) [110]. Similarly, Komotor et al. highlighted a 92.8% GTR rate in mTCA, compared with 63.2% in EEA (0.001) in the context of TSM and OGM [59], whilst Shetty et al. explored GTR in OGM, finding a significantly (p < 0.01) higher rate in mTCA (90.9%) than in EEA (70.2%) [115].

Regarding visual outcomes, a recent comparative meta-analysis by Lu et al. suggests improved visual outcome in OGM resection using the EEA (vs. mTCA) (OR, 0.318; p = 0.04) but not statistically significant in TSM [73]. This is slightly different from our updated findings and previous findings of Muskens et al. [84], in which the visual outcome advantage of EEA was most prominent in the TSM group. In other analyses, an early (2013) study by Clark et al. displayed higher (p < 0.01) visual improvement incidence in TSM with EEA (50–100 % in included studies) compared with mTCA studies (25–78 %) [24]. Shetty et al. explored OGM alone and found 80.7% visual improvement in the EEA studies group versus 12.83% in the mTCA group (p < 0.01) [115]. Ruggeri et al. replicated these findings when taking OGM and TSM as a collective group, with EEA displaying an 80.1% incidence visual improvement, significantly (p < 0.01) higher than mTCA (62.2%) [110].

In terms of CSF leak rate, Muskens et al. highlighted this as a disadvantage to the EEA in both TSM (EEA: 19.3% (95% CI 14.1–25.8%), mTCA 5.8% (95% CI 4.3– 7.8%)) and OGM (EEA: 25.1% (95% CI 17.5–34.8%), mTCA 10.5% (95% CI 8.2–13.4%)) [84]. This finding is echoed throughout relevant secondary literature, with Lu et al. highlighting a higher CSF leak incidence in EEA (vs mTCA) in TSM (OR 3.854; p = 0.013) and Shetty et al. showcasing a 25.7% CSF leak occurrence in EEA versus 6.3% in mTCA (p < 0.01) [73, 115]. In taking TSM and OGM, together, Komotor et al. demonstrated a higher CSF leak incidence of 21.3% in EEA, compared with 4.3% in mTCA (p < 0.01), whilst Ruggeri et al. illustrated 18.84% CSF leak occurrence in EEA versus 5.95% in mTCA (p < 0.01) [110, 115].

Finally, when considering 30-day mortality, significant associations have been difficult to establish both in our study and the literature. Ruggeri et al. found mortality rates of 2.3% in mTCA and 1.03% in EEA in TSM and OGM, but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.154) [110]. Similarly, differences in mortality explored by Muskens et al. were inconclusive in TSM (EEA: 5.2% (95% CI 3.4–10.8%), mTCA 2.7% (95% CI 1.8–4%)) and OGM (EEA: 4.3% (95% CI 1.5–11.6%), mTCA 3.9% (95% CI 2.7–5.8%)) [84]. A similar situation is found with intra-op arterial injury incidence with most syntheses not highlighting significant differences, echoed by our updated analysis [24, 59, 110, 115].

Limitations and strengths

The principal limitations of this study are the likely prevalent publication bias and heterogeneity of the primary literature synthesized, more specifically heterogeneity in the reporting of baseline characteristics and outcomes. This is reflected in the I2 and Cochran Q tests highlight in Figs. 2 and 3, corroborating with respective funnel charts (Appendix B). Development of core data set, through a multi-stakeholder consensus process for example, would be useful for future pooled analysis in the field. Secondly, it is likely the study populations examined are considerably variable owing to the surgical decision-making process that informs the choice of approach. Larger, more extensive tumours may be more likely to undergo traditional open approaches (of which there are many variants) in order to achieve acceptable tumour resection [84]. This is reflected in Tables 1 and 2 where larger (diameter and/or volume) tumours are included in the mTCA group compared with the EEA group. Unfortunately, we were not able to perform meta-regression based on tumour size or grade owing to heterogeneous data reporting, potentially adding to confounding factors [18, 46]. Additionally, the overwhelming majority of studies included were case series, and thus, our interpretation of our results should be tempered to reflect this. Finally, owing to the novelty of the approach, there is a relative paucity in the amount of included eSKA studies. Although overall, the results of the main analysis are similar to that of the sensitivity analysis subgroup, the number of low risk of bias studies analyzed is also limited. Future studies in the field must improve on methodological design, with an emphasis on comparative studies, in order to facilitate more robust data synthesis.

Conclusions

In the context of diverse study populations and heterogeneous case selection criteria, the endoscope-assisted supraorbital keyhole approach appeared not to be associated with increased adverse outcomes when compared with expanded endonasal and traditional transcranial approaches and offered comparable effectiveness. Case selection is paramount in establishing a role for the supraorbital keyhole approach in anterior skull base tumours. Development of standardized research databases and well-designed comparative studies that control for selection and confounding biases are needed to further delineate these selection criteria.

Electronic supplementary material

Search strategy (DOCX 13 kb)

Summary tables of study characteristics for Tuberculum Sellae meningioma and Olfactory Groove meningioma papers included in the meta-analysis (DOCX 54 kb)

Forrest plots for each tumour/approach/outcome combination (DOCX 1780 kb)

Funnel plots for each tumour/approach/outcome combination (DOCX 1428 kb)

Analysis of low of risk bias studies, compared with overall analysis (DOCX 23 kb)

Abbreviations

- TSM

Tuberculum sellae meningioma

- OGM

Olfactory groove meningioma

- eSKA

Endoscope-assisted supraorbital “keyhole” approach

- EEA

Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach

- mTCA

Microscopic transcranial approach

- GTR

Gross total resection

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- WHO

World Health Organization

- mNOS

Modified New-Castle Ottawa Scale

- ICA

Internal carotid arteries

- ACP

Anterior clinoid processes

- LP

Lamina papyracea

- CI

Confidence Interval

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by DZK, ISM, RAM, AHZ, and HJM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DZK, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this research. HJM is funded by the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Interventional and Surgical Sciences (WEISS) and the National Institute of Health Research University College London Biomedical Research Centre. AEH is supported by the Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was unnecessary due to the nature of the study (study-level meta-analysis).

Informed consent

Not applicable due to the nature of the study (study-level meta-analysis).

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Tumor - Meningioma

Comments

The authors have updated their previous meta-analysis on anterior fossa meningiomas, recognizing that the transcranial group comprises a huge variety of traditional approaches and newer minimally invasive techniques. It is important to compare modern microsurgical approaches against long established skull base methods, so it is no longer just about “above or below.”

Caroline Hayhurst

Wales, UK

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ali MZE-MS, Al-Azzazi A (2010) Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: surgical results and outcome in 30 cases. Egyptian J Neurol:549–554

- 2.Attia M, Kandasamy J, Jakimovski D, Bedrosian J, Alimi M, Lee DLY, Anand VK, Schwartz TH (2012) The importance and timing of optic canal exploration and decompression during endoscopic endonasal resection of tuberculum sella and planum sphenoidale meningiomas. Operative Neurosurgery 71:ons58-ons67 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bander ED, Singh H, Ogilvie CB, Cusic RC, Pisapia DJ, Tsiouris AJ, Anand VK, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic endonasal versus transcranial approach to tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale meningiomas in a similar cohort of patients. J Neurosurg. 2017;128:40–48. doi: 10.3171/2016.9.JNS16823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banu MA, Mehta A, Ottenhausen M, Fraser JF, Patel KS, Szentirmai O, Anand VK, Tsiouris AJ, Schwartz TH. Endoscope-assisted endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole resection of olfactory groove meningiomas: comparison and combination of 2 minimally invasive approaches. J Neurosurg. 2016;124:605–620. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.JNS141884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barzaghi LR, Spina A, Gagliardi F, Boari N, Mortini P. Transfrontal-sinus-subcranial approach to olfactory groove meningiomas: surgical results and clinical and functional outcome in a consecutive series of 21 patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassiouni H, Asgari S, Stolke D. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: functional outcome in a consecutive series treated microsurgically. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassiouni H, Asgari S, Stolke D. Olfactory groove meningiomas: functional outcome in a series treated microsurgically. Acta Neurochir. 2007;149:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-1075-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics:1088–1101 [PubMed]

- 9.Bernat A-L, Priola SM, Elsawy A, Farrash F, Pasarikovski CR, Almeida JP, Lenck S, De Almeida J, Vescan A, Monteiro E. Recurrence of anterior skull base meningiomas after endoscopic endonasal resection: 10 years’ experience in a series of 52 endoscopic and transcranial cases. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:e107–e113. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitter AD, Stavrinou LC, Ntoulias G, Petridis AK, Dukagjin M, Scholz M, Hassler W. The role of the pterional approach in the surgical treatment of olfactory groove meningiomas: a 20-year experience. J Neurol Surg Part B-Skull Base. 2013;74:97–102. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohman L-E, Stein SC, Newman JG, Palmer JN, Adappa ND, Khan A, Sitterley TT, Chang D, Lee JYK. Endoscopic versus open resection of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a decision analysis. ORL. 2012;74:255–263. doi: 10.1159/000343794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohman L-E, Stein SC, Newman JG, Palmer JN, Adappa ND, Khan A, Sitterley TT, Chang D, Lee JYK. Endoscopic versus open resection of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a decision analysis. Orl J Oto-Rhino-Laryngology Head Neck Surg. 2012;74:255–263. doi: 10.1159/000343794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowers CA, Altay T, Couldwell WT (2011) Surgical decision-making strategies in tuberculum sellae meningioma resection. Neurosurg Focus 30. 10.3171/2011.2.Focus1115 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bowers CA, Altay T, Couldwell WT. Surgical decision-making strategies in tuberculum sellae meningioma resection. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30:E1. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.FOCUS1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodbelt AR, Barclay ME, Greenberg D, Williams M, Jenkinson MD, Karabatsou K. The outcome of patients with surgically treated meningioma in England: 1999–2013. A cancer registry data analysis. Br J Neurosurg. 2019;33:641–647. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2019.1661965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai M, Hou B, Luo L, Zhang B, Guo Y. Trans-eyebrow supraorbital keyhole approach to tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a series of 30 cases with long-term visual outcomes and recurrence rates. J Neuro-Oncol. 2019;142:545–555. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catapano G, de Notaris M, Di Maria D, Fernandez LA, Di Nuzzo G, Seneca V, Iorio G, Dallan I. The use of a three-dimensional endoscope for different skull base tumors: results of a preliminary extended endonasal surgical series. Acta Neurochir. 2016;158:1605–1616. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-2847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavenee WK, Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceylan S, Anik I, Koc K, Cabuk B. Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach infrachiasmatic corridor. Neurosurg Rev. 2015;38:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s10143-014-0576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L-H, Chen L, Liu L-X. Microsurgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas by the frontolateral approach: surgical technique and visual outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chokyu I, Goto T, Ishibashi K, Nagata T, Ohata K. Bilateral subfrontal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas in long-term postoperative visual outcome Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:802–810. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.Jns101812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowdhury FH, Haque MR, Goel AH, Kawsar KA. Endoscopic endonasal extended transsphenoidal removal of tuberculum sellae meningioma (TSM): an experience of six cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:692–699. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.673648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciurea AV, Iencean SM, Rizea RE, Brehar FM. Olfactory groove meningiomas: a retrospective study on 59 surgical cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark AJ, Jahangiri A, Garcia RM, George JR, Sughrue ME, McDermott MW, El-Sayed IH, Aghi MK. Endoscopic surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2013;36:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s10143-013-0458-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colli BO, Carlotti Junior CG, Assirati Junior JA, Marques dos Santos MB, Neder L, dos Santos AC, Batagini NC (2007) Olfactory groove meningiomas—surgical technique and follow-up review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 65:795-799. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2007000500012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Curey S, Derrey S, Hannequin P, Hannequin D, Freger P, Muraine M, Castel H, Proust F. Validation of the superior interhemispheric approach for tuberculum sellae meningioma Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:1013–1021. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.Jns12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Aguiar PHP, Tahara A, Almeida AN, Simm R, da Silva AN, Maldaun MVC, Panagopoulos AT, Zicarelli CA, Silva PG. Olfactory groove meningiomas: approaches and complications. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Almeida JR, Carvalho F, Guimaraes Filho FV, Kiehl T-R, Koutourousiou M, Su S, Vescan AD, Witterick IJ, Zadeh G, Wang EW, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Gardner PA, Gentili F, Snyderman CH. Comparison of endoscopic endonasal and bifrontal craniotomy approaches for olfactory groove meningiomas: A matched pair analysis of outcomes and frontal lobe changes on MRI. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1733–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Divitiis E, Esposito F, Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, de Divitiis O. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: High route or low route? A series of 51 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:556–562. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000317303.93460.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Divitiis E, Esposito F, Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, de Divitiis O, Esposito I (2008) Endoscopic transnasal resection of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus 25. 10.3171/foc.2008.25.12.E8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Della Puppa A, d'Avella E, Rossetto M, Volpin F, Rustemi O, Gioffre G, Lombardi G, Rolma G, Scienza R (2015) Open transcranial resection of small (< 35 mm) meningiomas of the anterior midline skull base in current microsurgical practice. World Neurosurg 84. 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.DeMonte F, McDermott MW, Al-Mefty O (2011) Al-Mefty's meningiomas. Thieme

- 33.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dzhindzhikhadze RS, Dreval ON, Lazarev VA, Polyakov AV, Kambiev RL, Salyamova EI. Transpalpebral approach for microsurgical removal of tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020;15:98. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_186_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D (2008) Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. John Wiley & Sons

- 37.Elshazly K, Kshettry VR, Farrell CJ, Nyquist G, Rosen M, Evans JJ. Clinical outcome after endoscopic endonasal resection of tuberculum sella meningiomas. Oper Neurosurg. 2017;14:494–502. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelhardt J, Namaki H, Mollier O, Monteil P, Penchet G, Cuny E, Loiseau H. Contralateral transcranial approach to tuberculum sellae meningiomas: long-term visual outcomes and recurrence rates. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:e1066–e1074. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eroglu U, Shah K, Bozkurt M, Kahilogullari G, Yakar F, Dogan İ, Ozgural O, Attar A, Unlu A, Caglar S. Supraorbital keyhole approach: lessons learned from 106 operative cases. World Neurosurg. 2019;124:e667–e674. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farooq G, Rehman L, Bokhari I, Rizvi SRH. Modern microsurgical resection of olfactory groove meningiomas by classical bicoronal subfrontal approach without orbital osteotomies. Asian J Neurosurg. 2018;13:258. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_66_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fatemi N, Dusick JR, de Paiva Neto MA, Malkasian D, Kelly DF. Endonasal versus supraorbital keyhole removal of craniopharyngiomas and tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Operative. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:ons269–ons287. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000327857.22221.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fountas KN, Hadjigeorgiou GF, Kapsalaki EZ, Paschalis T, Rizea R, Ciurea AV. Surgical and functional outcome of olfactory groove meningiomas: lessons from the past experience and strategy development. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;171:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganna A, Dehdashti AR, Karabatsou K, Gentili F. Fronto-basal interhemispheric approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas; long-term visual outcome. Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23:422–430. doi: 10.1080/02688690902968836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goel A, Bhaganagare A, Shah A, Kaswa A, Rai S, Dharurkar P, Gore S. Olfactory groove meningiomas: An analysis based on surgical experience with 129 cases. Neurol India. 2018;66:1081. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.236989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goel A, Muzumdar D. Surgical strategy for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg Q. 2005;15:25–32. doi: 10.1097/01.wnq.0000152404.94129.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gousias K, Schramm J, Simon M. The Simpson grading revisited: aggressive surgery and its place in modern meningioma management. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:551–560. doi: 10.3171/2015.9.JNS15754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guduk M, Yener U, Sun HI, Hacihanefioglu M, Ozduman K, Pamir MN. Pterional and unifrontal approaches for the microsurgical resection of olfactory groove meningiomas: experience with 61 consecutive patients. Turk Neurosurg. 2017;27:707–715. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.17154-16.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo S, Gerganov V, Giordano M, Samii A, Samii M. Elderly patients with frontobasal and suprasellar meningiomas: safety and efficacy of tumor removal via frontolateral approach. World Neurosurg. 2020;135:e452–e458. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi Y, Kita D, Fukui I, Sasagawa Y, Oishi M, Tachibana O, Ueda F, Nakada M. Preoperative evaluation of the interface between tuberculum sellae meningioma and the optic nerves on fast imaging with steady-state acquisition for extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. World Neurosurg. 2017;103:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.03.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayhurst C, Sughrue ME, Gore PA, Bonney PA, Burks JD, Teo C. Results with expanded endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas technical nuances and approach selection based on an early experience. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:662–670. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.16105-15.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, vol 4. John Wiley & Sons

- 52.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Igressa A, Pechlivanis I, Weber F, Mahvash M, Ayyad A, Boutarbouch M, Charalampaki P. Endoscope-assisted keyhole surgery via an eyebrow incision for removal of large meningiomas of the anterior and middle cranial fossa. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;129:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang W-Y, Jung S, Jung T-Y, Moon K-S, Kim I-Y. The contralateral subfrontal approach can simplify surgery and provide favorable visual outcome in tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:601–607. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jang W-Y, Jung S, Jung T-Y, Moon K-S, Kim I-Y. Preservation of olfaction in surgery of olfactory groove meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1288–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karsy M, Raheja A, Eli I, Guan J, Couldwell WT. Clinical outcomes with transcranial resection of the tuberculum sellae meningioma. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan OH, Anand VK, Schwartz TH (2014) Endoscopic endonasal resection of skull base meningiomas: the significance of a “cortical cuff” and brain edema compared with careful case selection and surgical experience in predicting morbidity and extent of resection. Neurosurg Focus 37. 10.3171/2014.7.Focus14321 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Raper DMS, Anand VK, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic endonasal versus open transcranial resection of anterior midline skull base meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2012;77:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kong D-S, Hong C-K, Hong SD, Nam D-H, Lee J-I, Seol HJ, Oh J, Kim DG, Kim YH. Selection of endoscopic or transcranial surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas according to specific anatomical features: a retrospective multicenter analysis (KOSEN-002) J Neurosurg. 2018;130:838–847. doi: 10.3171/2017.11.JNS171337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koutourousiou M, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Stefko ST, Wang EW, Snyderman CH, Gardner PA. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for suprasellar meningiomas: experience with 75 patients Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:1326–1339. doi: 10.3171/2014.2.Jns13767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koutourousiou M, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Wang EW, Snyderman CH, Gardner PA (2014) Endoscopic endonasal surgery for olfactory groove meningiomas: outcomes and limitations in 50 patients. Neurosurg Focus 37. 10.3171/2014.7.Focus14330 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Kuga D, Toda M, Yoshida K. Treatment strategy for tuberculum sellae meningiomas based on a preoperative radiological assessment. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:e1279–e1288. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Landeiro JA, Goncalves MB, Guimaraes RD, Klescoski J, Amorim Correa JL, Lapenta MA, Maia O. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: surgical considerations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68:424–429. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2010000300019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leveque S, Derrey S, Martinaud O, Gerardin E, Langlois O, Freger P, Hannequin D, Castel H, Proust F. Superior interhemispheric approach for midline meningioma from the anterior cranial base. Neurochirurgie. 2011;57:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Liu M, Liu Y, Zhu S. Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:1150–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linsler S, Fischer G, Skliarenko V, Stadie A, Oertel J. Endoscopic assisted supraorbital keyhole approach or endoscopic endonasal approach in cases of tuberculum sellae meningioma: which surgical route should be favored? World Neurosurg. 2017;104:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu H-C, Qiu E, Zhang J-L, Kang J, Li Y, Li Y, Jiang L-B, Fu J-D. Surgical indications of exploring optic canal and visual prognostic factors in neurosurgical treatment of tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Chin Med J. 2015;128:2307–2311. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.163391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu JK, Christiano LD, Patel SK, Tubbs RS, Eloy JA. Surgical nuances for removal of tuberculum sellae meningiomas with optic canal involvement using the endoscopic endonasal extended transsphenoidal transplanum transtuberculum approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30:E2. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.FOCUS115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu JK, Silva NA, Sevak IA, Eloy JA. Transbasal versus endoscopic endonasal versus combined approaches for olfactory groove meningiomas: importance of approach selection. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E8. doi: 10.3171/2018.1.FOCUS17722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Yan L-M, Wan L, Xiang T-X, Le A, Liu J-M, Peiris M, Poon LLM, Zhang W (2020) Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu VM, Goyal A, Rovin RA (2018) Olfactory groove and tuberculum sellae meningioma resection by endoscopic endonasal approach versus transcranial approach: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Magill ST, Morshed RA, Lucas C-HG, Aghi MK, Theodosopoulos PV, Berger MS, de Divitiis O, Solari D, Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: grading scale to assess surgical outcomes using the transcranial versus transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E9. doi: 10.3171/2018.1.FOCUS17753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mahmoud M, Nader R, Al-Mefty O. Optic canal involvement in tuberculum sellae meningiomas: influence on approach, recurrence, and visual recovery. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:108–118. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000383153.75695.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Margalit N, Shahar T, Barkay G, Gonen L, Nossek E, Rozovski U, Kesler A. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: surgical technique, visual outcome, and prognostic factors in 51 cases. J Neurol Surg Part B-Skull Base. 2013;74:247–257. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1342920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mariniello G, de Divitiis O, Bonavolonta G, Maiuri F. Surgical unroofing of the optic canal and visual outcome in basal meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marx S, Clemens S, Schroeder HWS. The value of endoscope assistance during transcranial surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2017;128:32–39. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.JNS16713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mathiesen T, Kihlstrom L. Visual outcome of tuberculum sellae meningiomas after extradural optic nerve decompression. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:570–575. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000228683.79123.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mathiesen T, Kihlström L. Visual outcome of tuberculum sellae meningiomas after extradural optic nerve decompression. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:570–576. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000228683.79123.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mortazavi MM, da Silva HB, Ferreira M, Jr, Barber JK, Pridgeon JS, Sekhar LN. Planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae meningiomas: operative nuances of a modern surgical technique with outcome and proposal of a new classification system. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mukherjee S, Thakur B, Corns R, Connor S, Bhangoo R, Ashkan K, Gullan R. Resection of olfactory groove meningioma - a review of complications and prognostic factors. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:685–692. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1054348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Muskens IS, Briceno V, Ouwehand TL, Castlen JP, Gormley WB, Aglio LS, Najafabadi AHZ, van Furth WR, Smith TR, Mekary RA. The endoscopic endonasal approach is not superior to the microscopic transcranial approach for anterior skull base meningiomas—a meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir. 2018;160:59–75. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3390-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakamura M, Roser F, Struck M, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: clinical outcome considering different surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1019–1028. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000245600.92322.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakamura M, Struck M, Roser F, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Olfactory groove meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rates after tumor removal through the frontolateral and bifrontal approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:844–852. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255453.20602.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakamura M, Struck M, Roser F, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Olfactory groove meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rates after tumor removal through the frontolateral and bifrontal approach. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1224–1231. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000255453.20602.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nanda A, Ambekar S, Javalkar V, Sharma M (2013) Technical nuances in the management of tuberculum sellae and diaphragma sellae meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus 35. 10.3171/2013.10.Focus13350 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Nanda A, Maiti TK, Bir SC, Konar SK, Guthikonda B. Olfactory groove meningiomas: comparison of extent of frontal lobe changes after lateral and bifrontal approaches. World Neurosurg. 2016;94:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nozaki K, K-i K, Takagi Y, Mineharu Y, Takahashi JA, Hashimoto N. Effect of early optic canal unroofing on the outcome of visual functions in surgery for meningiomas of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:839–846. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000318169.75095.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ogawa Y, Tominaga T. Extended transsphenoidal approach for tuberculum sellae meningioma—what are the optimum and critical indications? Acta Neurochir. 2012;154:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ottenhausen M, Rumalla K, Alalade AF, Nair P, La Corte E, Younus I, Forbes JA, Nsir AB, Banu MA, Tsiouris AJ. Decision-making algorithm for minimally invasive approaches to anterior skull base meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44:E7. doi: 10.3171/2018.1.FOCUS17734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Padhye V, Naidoo Y, Alexander H, Floreani S, Robinson S, Santoreneos S, Wickremesekera A, Brophy B, Harding M, Vrodos N, Wormald P-J. Endoscopic endonasal resection of anterior skull base meningiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:575–582. doi: 10.1177/0194599812446565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paiva-Neto MAd, Tella-Jr OId (2010) Supra-orbital keyhole removal of anterior fossa and parasellar meningiomas. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 68:418-423 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.Palani A, Panigrahi MK, Purohit AK. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: a series of 41 cases; surgical and ophthalmological outcomes with proposal of a new prognostic scoring system. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:286–293. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pallini R, Fernandez E, Lauretti L, Doglietto F, D'Alessandris QG, Montano N, Capo G, Meglio M, Maira G. Olfactory groove meningioma: report of 99 cases surgically treated at the Catholic University School of Medicine, Rome. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:219. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pamir MN, Ozduman K, Belirgen M, Kilic T, Ozek MM. Outcome determinants of pterional surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:1121–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park C-K, Jung H-W, Yang S-Y, Seol HJ, Paek SH, Kim DG. Surgically treated tuberculum sellae and diaphragm sellae meningiomas: the importance of short-term visual outcome. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:238–243. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000223341.08402.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patel K, Kolias AG, Santarius T, Mannion RJ, Kirollos RW. Results of transcranial resection of olfactory groove meningiomas in relation to imaging-based case selection criteria for the endoscopic approach. Oper Neurosurg. 2018;16:539–548. doi: 10.1093/ons/opy191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Patel ZM, Fernandez-Miranda J, Hwang PH, Nayak JV, Dodd R, Sajjadi H, Jackler RK (2020) Precautions for endoscopic transnasal skull base surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Pepper J-P, Hecht SL, Gebarski SS, Lin EM, Sullivan SE, Marentette LJ. Olfactory groove meningioma: discussion of clinical presentation and surgical outcomes following excision via the subcranial approach. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2282–2289. doi: 10.1002/lary.22174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Perneczky A, Reisch R. Keyhole approaches in neurosurgery: volume 1: concept and surgical technique. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Refaat MI, Eissa EM, Ali MH. Surgical management of midline anterior skull base meningiomas: experience of 30 cases. Turk Neurosurg. 2015;25:432–437. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.Jtn.11632-14.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Reisch R, Marcus HJ, Hugelshofer M, Koechlin NO, Stadie A, Kockro RA. Patients' cosmetic satisfaction, pain, and functional outcomes after supraorbital craniotomy through an eyebrow incision. J Neurosurg. 2014;121:730–734. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.JNS13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reisch R, Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Operative. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:ONS–242. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000178353.42777.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reisch R, Perneczky A, Filippi R. Surgical technique of the supraorbital key-hole craniotomy. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)01037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reisch R, Stadie A, Kockro RA, Hopf N. The keyhole concept in neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:S17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Romani R, Laakso A, Kangasniemi M, Niemelä M, Hernesniemi J. Lateral supraorbital approach applied to tuberculum sellae meningiomas: experience with 52 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:1504–1519. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31824a36e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Romani R, Lehecka M, Gaal E, Toninelli S, Çelik Ö, Niemelä M, Porras M, Jääskeläinen J, Hernesniemi J. Lateral supraorbital approach applied to olfactory groove meningiomas: experience with 66 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:39–53. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000346266.69493.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ruggeri AG, Cappelletti M, Fazzolari B, Marotta N, Delfini R. Frontobasal midline meningiomas: is it right to shed doubt on the transcranial approaches? Updates and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2016;88:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Salek MAA, Faisal MH, Manik MAH, Choudhury A-U-M, Chowdhury RU, Islam MA. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for resection of tuberculum sella and planum sphenoidale meningiomas: a snapshot of our institutional experience. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020;15:22. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_85_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schick U, Hassler W. Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: involvement of the optic canal and visual outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:977–983. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.039974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schroeder HWS, Hickmann A-K, Baldauf J. Endoscope-assisted microsurgical resection of skull base meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2011;34:441–455. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seol HJ, Park H-Y, Nam D-H, Kong D-S, Lee J-I, Kim JH, Park K. Clinical outcomes of tuberculum sellae meningiomas focusing on reversibility of postoperative visual function. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shetty SR, Ruiz-Treviño AS, Omay SB, Almeida JP, Liang B, Chen Y-N, Singh H, Schwartz TH. Limitations of the endonasal endoscopic approach in treating olfactory groove meningiomas. A systematic review. Acta Neurochir. 2017;159:1875–1885. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Slavik E, Radulovic D, Tasic G. Olfactory groove meningiomas. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2007;54:59–62. doi: 10.2298/aci0702059s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Smith KA, Leever JD, Chamoun RB. Predicting consistency of meningioma by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2015;76:225–229. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1543965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Society of British Neurological Surgeons (SBNS) (2020) Transmission Of Covid-19 During neurosurgical procedures. https://www.sbns.org.uk/index.php/download_file/view/1658/416/. Accessed 01/06/2020 2020

- 120.Song SW, Kim YH, Kim JW, Park C-K, Kim JE, Kim DG, Koh Y-C, H-w J. Outcomes after transcranial and endoscopic endonasal approach for tuberculum meningiomas—a retrospective comparison. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e434–e445. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Spektor S, Valarezo J, Fliss DM, Gil Z, Cohen J, Goldman J, Umansky F. Olfactory groove meningiomas from neurosurgical and ear, nose, and throat perspectives: approaches, techniques, and outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:268–279. doi: 10.1227/01.Neu.0000176409.70668.Eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Telera S, Carapella CM, Caroli F, Crispo F, Cristalli G, Raus L, Sperduti I, Pompili A. Supraorbital keyhole approach for removal of midline anterior cranial fossa meningiomas: a series of 20 consecutive cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2012;35:67–83. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tuna H, Bozkurt M, Ayten M, Erdogan A, Deda H. Olfactory groove meningiomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:664–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Voznyak O, Lytvynenko A, Maydannyk O, Ilyuk R, Zinkevych Y, Hryniv N (2020) Tuberculum sellae meningioma surgery: visual outcomes and surgical aspects of contralateral approach. Neurosurg Rev:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.Wang Q, Lu X-J, Ji W-Y, Yan Z-C, Xu J, Ding Y-S, Zhang J. Visual outcome after extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for tuberculum sellae meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wells GA, Tugwell P, O’Connell D, Welch V, Peterson J, Shea B, Losos M (2015) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 01/06/20 2020

- 127.Wilk A, Zielinski G, Witek P, Koziarski A. Outcome assessment after surgical treatment of tuberculum sellae meningiomas—a preliminary report. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:824–832. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.Jtn.14160-15.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xiao J, Wang W, Wang X, Mao Z, Qi H, Cheng H, Yu Y. Supraorbital keyhole approach to the sella and anterior skull base via a forehead wrinkle incision. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e343–e351. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Xu M, Xu J, Huang X, Chen D, Chen M, Zhong P. Small extended bifrontal approach for midline anterior skull base meningiomas: our experience with 54 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2019;125:e35–e43. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhou H, Wu Z, Wang L, Zhang J. Microsurgical treatment of tuberculum sellae meningiomas with visual impairments: a chinese experience of 56 cases. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26:48–53. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.Jtn.11476-14.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zoli M, Guaraldi F, Pasquini E, Frank G, Mazzatenta D. The endoscopic endonasal management of anterior skull base meningiomas. J Neurol Surg Part B: Skull Base. 2018;79:S300–S310. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1669463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy (DOCX 13 kb)

Summary tables of study characteristics for Tuberculum Sellae meningioma and Olfactory Groove meningioma papers included in the meta-analysis (DOCX 54 kb)

Forrest plots for each tumour/approach/outcome combination (DOCX 1780 kb)

Funnel plots for each tumour/approach/outcome combination (DOCX 1428 kb)

Analysis of low of risk bias studies, compared with overall analysis (DOCX 23 kb)