Abstract

Intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) is thought to be a viable treatment for numerous disorders. Although the intrinsic immunosuppressive ability of MSCs has been credited for this therapeutic effect, their exact impact on endogenous tissue-resident cells following delivery has not been clearly characterized. Moreover, multiple studies have reported pulmonary sequestration of MSCs upon intravenous delivery. Despite substantial efforts to improve MSC homing, it remains unclear whether MSC migration to the site of injury is necessary to achieve a therapeutic effect. Using a murine excisional wound healing model, we offer an explanation of how sequestered MSCs improve healing through their systemic impact on macrophage subpopulations. We demonstrate that infusion of MSCs leads to pulmonary entrapment followed by rapid clearance, but also significantly accelerates wound closure. Using single-cell RNA sequencing of the wound, we show that following MSC delivery, innate immune cells, particularly macrophages, exhibit distinctive transcriptional changes. We identify the appearance of a pro-angiogenic CD9+ macrophage subpopulation, whose induction is mediated by several proteins secreted by MSCs, including COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3. Our findings suggest that MSCs do not need to act locally to induce broad changes in the immune system and ultimately treat disease.

Keywords: wound healing, macrophages, mesenchymal stromal cells

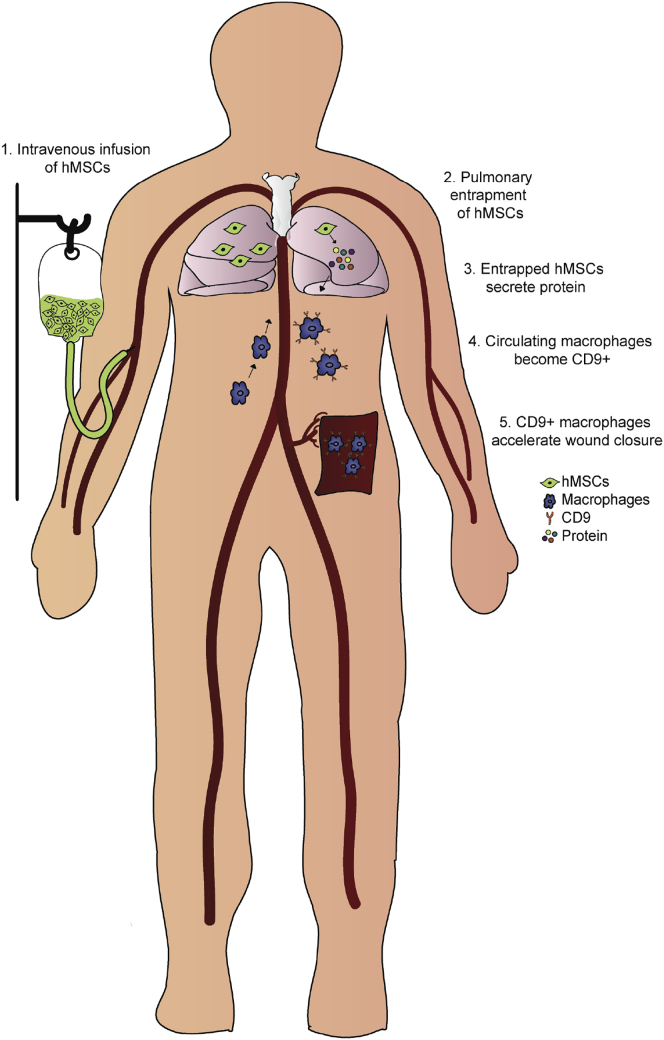

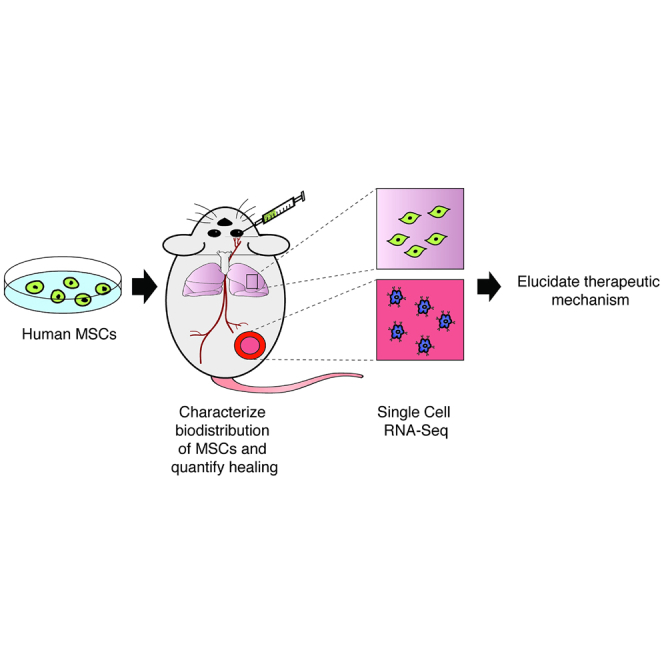

Graphical Abstract

Cell therapeutics are emerging as a viable and effective option in the field of wound care. In this study, using a murine model, the authors show that the systemic infusion of MSCs drives differentiation of migratory macrophages into a regenerative phenotype that accelerates wound healing.

Introduction

Intravenous (i.v.) infusion of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) has been shown to potentiate lasting therapeutic effects in a variety of disorders.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Such infusion allows for systemic MSC delivery in instances where afflicted tissue is not readily accessible, such as after heart and brain injury,6,7 and may be beneficial for the treatment of systemic inflammatory or immune-mediated disorders.1,8 Upon administration, MSCs display low levels of long-term incorporation into tissue and do not exhibit significant immunogenicity, allowing for allogeneic transplantation in the absence of immunosuppressive drugs.9,10 However, the presence of MSCs following i.v. infusion compared to other methods of delivery is especially short-lived in the recipient.11 Numerous studies have shown that the majority of infused cells are entrapped in pulmonary capillaries immediately after delivery and are eliminated within 24–48 h after infusion, demonstrating limited migration beyond the lung and to the target site.11, 12, 13 It is intriguing that the transient presence of MSCs in patients following i.v. delivery has clinically significant effects. The lack of long-term detection of infused MSCs suggests that they may promote healing through the release of paracrine factors into the circulation that modulate the activity of endogenous cells.

One of the main mechanisms thought to contribute to the overall therapeutic potential of MSCs is their immunosuppressive ability. MSCs have been shown to modulate the activity of several types of immune cells, including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells, by suppressing their proliferation, activation, and migration via paracrine factors, including TSG-6, nitric oxide, transforming growth factor β (TGFB), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).14 Until recently, little was known about the interactions of MSCs with monocytes and macrophages, but accumulating evidence has suggested that MSCs play a key role in regulating macrophage activity during initial inflammation and subsequent tissue regeneration.4,15 Upon injury, local inflammatory responses activate resident macrophages and recruit macrophages from the circulation.16 Several phenotypic states of macrophages have been well described and play distinct functions in different stages of repair.17 Macrophages that infiltrate the wound in the earliest stages of healing enhance the immune response by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18, and are called M1 or classically activated macrophages.18 M2 or alternatively activated macrophages secrete high levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and are present in the wound in latter stages of healing, where they are thought to be involved in resolving inflammation and promoting tissue repair and remodeling.19,20

Several studies have suggested that MSCs promote M1-to-M2 macrophage polarization.4,5,21 Multiple mechanisms underlying this process have been proposed but remain incompletely understood. It has been suggested that macrophage activation occurs either as a result of phagocytosis of infused MSCs21,22 or in response to proteins secreted by MSCs.3,4 A major limitation to these studies is the use of a single marker to distinguish between M1 and M2 macrophages, with most studies relying on evaluation of CD206 as a measure of M2 macrophage activation. Evidence that macrophage subpopulations can be segmented beyond M1 and M2 phenotypes further complicates interpretation of existing results. In the present study, we apply single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) as an unbiased profiling strategy to investigate the effect of MSC infusion on wound cell populations. We demonstrate that i.v. infusion of human bone marrow-derived MSCs (hMSCs) into mice accelerates wound healing and identify a pro-angiogenic subpopulation of macrophages that is increased following MSC treatment. Finally, we identify several proteins secreted by MSCs through which this process is mediated.

Results

Single Retro-Orbital Infusion of hMSCs Accelerates Mouse Excisional Wound Healing

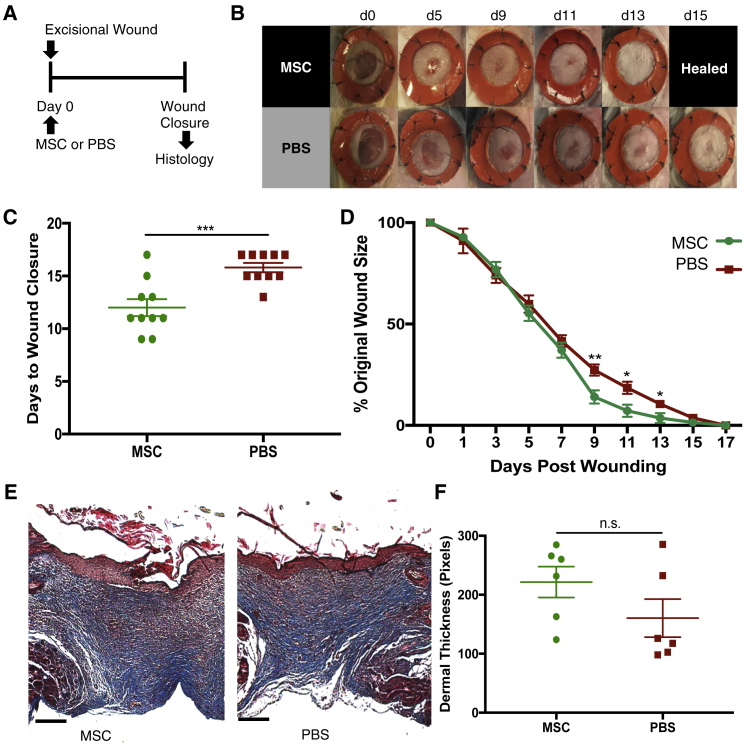

The efficacy of a single dose of i.v. administered hMSCs on wound healing was evaluated in a mouse excisional wound healing model as previously described (Figure 1A).23 Wounds were splinted to mimic human wound healing through deposition of new granulation tissue and re-epithelialization rather than contracture. Immediately after wounding, 1.0 × 106 hMSCs resuspended in PBS or an equal volume of PBS were injected retro-orbitally, and the rate of wound healing was evaluated every other day. Intravenous infusion of MSCs via retro-orbital injection rather than tail vein injection was chosen because it was less technically challenging and allowed us to administer cells more reliably. Single infusion of hMSCs significantly accelerated the rate of wound healing as compared with PBS. The mean time for complete wound healing was 12.0 ± 0.80 days in the MSC-treated group compared to 15.8 ± 0.44 days in the PBS-treated group (p < 0.001, Figures 1B and 1C). In a separate experiment, we directly compared local delivery and i.v. infusion of MSCs (Figure S1). Notably, there was no significant advantage in healing time following direct injection of MSCs (12.2 ± 0.6 days) compared to i.v. infusion (13.5 ± 0.5 days, p = 0.6). Masson’s trichrome staining revealed no discernible differences in the quality of healed wounds between the groups, despite significant differences in time to closure (Figures 1E and 1F).

Figure 1.

Single Retro-Orbital Infusion of hMSCs Accelerates Mouse Excisional Wound Healing

(A) Experimental scheme for excisional wounding and treatment. 1 h after excisional wounding, either hMSCs (1 × 106 cells in 100 μL of PBS) or the same volume of PBS was injected retro-orbitally. Wounds were harvested upon closure. (B) Representative photographs of wounds (n = 10/group) during healing with infused hMSCs (top row) or with PBS vehicle control (bottom row). (C) Bar graph showing difference in time to complete wound closure between mice treated with hMSCs or PBS (hMSCs, 12.0 ± 0.80 days; PBS, 15.8 ± 0.44 days) (n = 10). (D) Wound-healing curve showing wound size as a percentage of original wound over time (n = 10). (E) Masson’s trichrome stain of healed wounds from mice treated with hMSCs (left) or PBS (right). (F) Bar graph depicting mean length of dermal thickness measured in center of healed wounds from mice treated with hMSCs or PBS. Scale bars, 100 μm. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

MSCs Entrap in the Lung and Are Cleared Rapidly during the First 3 Days following Retro-Orbital Infusion

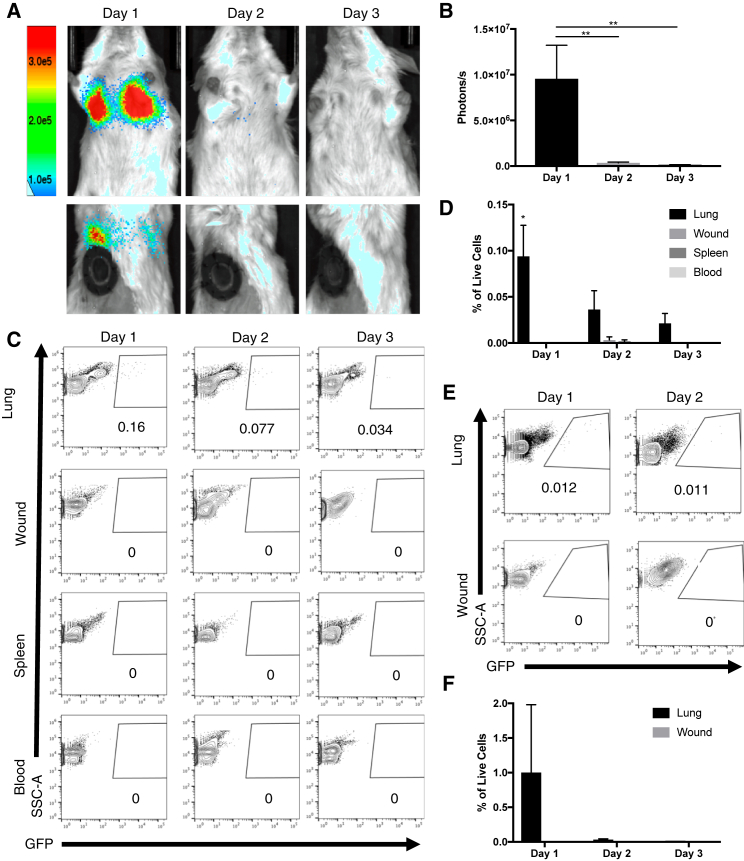

We examined the biodistribution of hMSCs following retro-orbital infusion to determine whether cells act systemically or home to the site of injury to act locally. To enable in vivo cell tracking, we constructed a GFP-firefly luciferase (fLuc) hMSC line using CRISPR-Cas9-adeno-associated virus 6 (AAV6)-mediated targeted gene insertion. Single excisional wounds were created to produce an ischemic stimulus to encourage MSC homing toward the site of injury. 1.0 × 106 GFP-fLuc hMSCs were injected retro-orbitally immediately after wounding. The biodistribution of the cells was evaluated every 24 h for 3 days using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS). Bioluminescence (BLI) images revealed localization of cells to the lung 24 h after injection. Significant clearance of the cells from the lung occurred 48 h after injection, and signal disappeared almost entirely 3 days after infusion (Figures 2A and 2B). Notably, bioluminescent signal was not detectable at any other location in any mouse at any time point. Biodistribution of MSCs following tail vein injection was also evaluated to confirm our findings, but similar levels of lung entrapment and a lack of administered cells homing to the site of injury were observed (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

MSCs Entrap in the Lung and Are Cleared Rapidly during the First 3 Days following Retro-Orbital Infusion.

(A) Images show ventral (top row) and dorsal (bottom row) views of BLI from hMSCs expressing GFP and fLuc during 3 days in one representative animal following retro-orbital infusion. BLI is detected in the lungs of mice 1 day after retro-orbital infusion and disappears entirely within 3 days. (B) Bar graph depicting BLI in lungs measured in photons/s (n = 3). (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of lung, wound, spleen, and blood harvested from mice 1, 2, and 3 days after excisional wounding and retro-orbital infusion of GFP-hMSCs. GFP+ cells are only detectable in the lung at all three time points. (D) Bar graph depicting distribution of GFP+ cells as percentage of all live cells in lung, wound, spleen, and blood harvested from mice on days 1, 2, and 3 following administration of GFP-hMSCs. (n = 3) (E) Representative flow cytometry plots of lung and wound harvested from mice on days 1, 2, and 3 following administration of GFP-mMSCs. GFP+ cells are only detectable in the lung at all three time points. (F) Bar graph depicting distribution of GFP+ cells as percentage of all live cells in lung and wound harvested from mice on days 1, 2, and 3 following administration of GFP-mMSCs (n = 3). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, by one-way ANOVA. BLI, bioluminescence; hMSC, human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell; fLuc: firefly luciferase, mMSC, mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell.

Flow cytometry was used to ensure that our lack of detection of hMSCs was not due to the low sensitivity of IVIS imaging. Lung, wound, spleen, and blood were harvested and digested 1, 2, and 3 days after wounding and treatment. Consistent with our BLI imaging studies, we detected GFP+ hMSCs in the lung 1 day following injection, with rapid clearance of the cells from the lung on day 2 and day 3 after injection. Also consistent with our BLI imaging studies, GFP+ hMSCs were not detected in the blood, spleen, or wound at any time point (Figures 2C and 2D).

To investigate whether the failure of hMSCs to home to sites of ischemia in mice might be due to a xenogeneic effect, we administered 3.5 × 105 syngeneic GFP+ mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs (mMSCs) retro-orbitally to mice immediately after excisional wounding and harvested the lung and wound 1 and 2 days after injection. Flow cytometry analysis showed that similar to our results using hMSCs, GFP+ cells were detected only in the lung (Figures 2E and 2F). We examined the biodistribution of cells following i.v. delivery in two additional models of ischemia, ischemic flap and hindlimb ischemia, to ensure that the lack of MSC homing was not due to insufficient ischemic stimulus. We detected GFP+ cells in the lung but not at either site of injury (Figure S3). Collectively, these data show that MSCs do not migrate beyond the lung in three models of ischemic injury, suggesting that the therapeutic effect of i.v. infused MSCs is systemic rather than local.

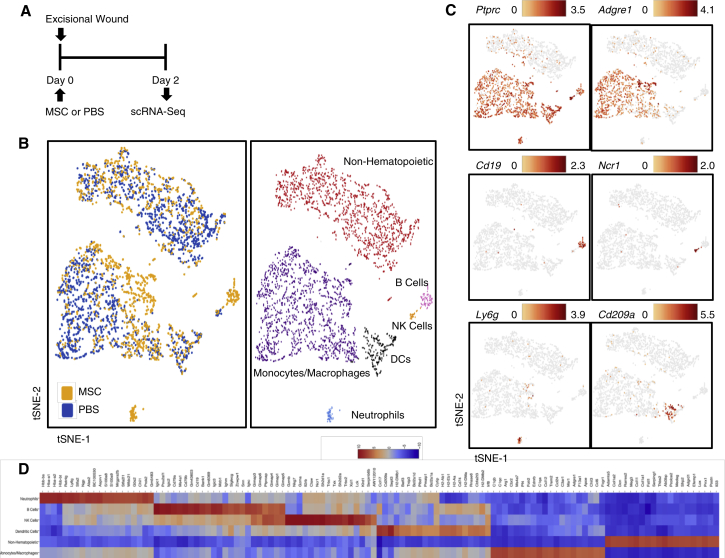

scRNA-Seq Reveals Shift in Cell Population Dynamics in Wounds following hMSC Treatment

Having determined that the therapeutic effect of MSCs is not local, we aimed to demonstrate their systemic effect by examining treatment-associated changes in the composition of endogenous cells in the wound, where we observed accelerated healing in response to i.v. administered MSCs. We digested wounds harvested 2 days after excisional wounding and MSC or PBS injection, representing an early inflammatory stage of healing during which infused MSCs are being cleared from the lungs (Figure 3A). 1,873 cells from five pooled PBS control wounds and 1,416 cells from five pooled MSC-treated wounds were included in the scRNA-seq analysis. Gene expression data from cells extracted from both groups were aligned and projected in a two-dimensional space through t-Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to allow identification of overlapping and treatment-associated immune cell populations (Figure 3B). Gene expression patterns of established canonical markers of cell populations allowed us to assign putative biological identities and evaluate the contribution of each cell subpopulation (Figures 3B–3D).

Figure 3.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Shift in Cell Population Dynamics in Wounds following hMSC Treatment

(A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of the wound. Mice were given excisional wounds and injected retro-orbitally with hMSCs or PBS on the same day. Wounds from five animals per group were harvested, pooled, and subjected to scRNA-seq 2 days later. (B) t-Stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) representation of aligned gene expression data in single cells extracted from PBS (n = 1,873) and MSC-treated (n = 1,416) wounds of mice showing distribution by treatment group (left) and partitioned into distinct cell populations based on expression of canonical markers (right). (C) Gene expression patterns of established canonical markers of cell populations projected onto t-SNE plots (expressed as log2). (D) Heatmap depicting the 20 most upregulated genes in each cell population defined in (B).

Wounds were comprised of both non-hematopoietic (negative for Ptprc, encoding for the CD45 antigen) and hematopoietic (Ptprc+) cells. Hematopoietic cells could further be distinguished into monocytes and macrophages (enriched genes: Adgre1, encoding for the F4/80 antigen, Fcgr1, Cd68), B cells (Cd79a, Cd79b, Cd19), natural killer cells (Gzma, Nkg7, Il2rb, Ncr1), neutrophils (Ly6g), and dendritic cells (Cd209a, Cd74). Strikingly, transcriptional profiles of macrophages from the two treatment groups appeared to be differently distributed (Figure 3B), although treatment did not affect the overall number of macrophages in the lung, wound, or blood (Figure S4).

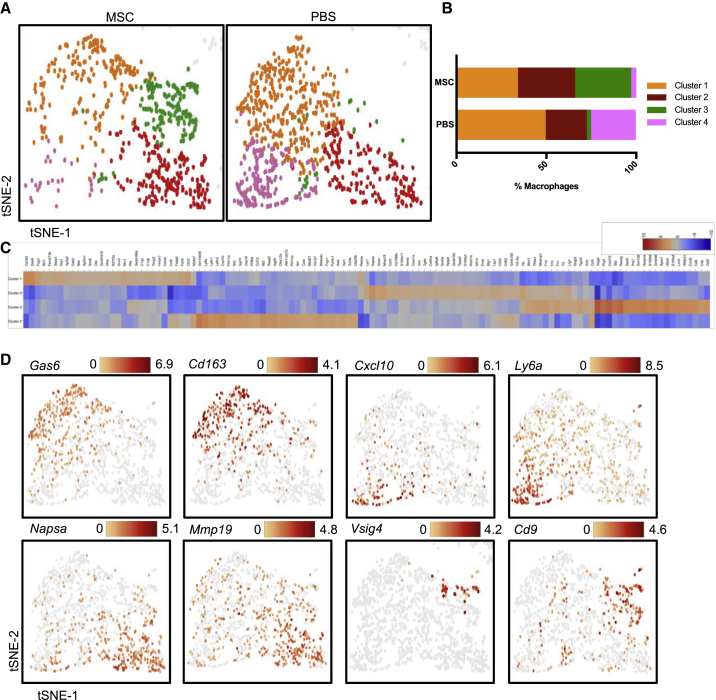

hMSC Infusion Is Associated with Differently Distributed Macrophage Subpopulations in the Wound

Because macrophages seemed to cluster separately by treatment group in our analysis of the global wound dataset, we analyzed the specific gene expression patterns differentiating macrophage subpopulations from one another. Using Loupe Cell Browser to examine the sequencing data, we applied graph-based clustering to all Adgre1+ macrophages and identified four transcriptionally distinct macrophage subpopulations, with the distribution of clusters varying by treatment group. Cluster 1 and cluster 2 were distributed similarly in both treatment groups (cluster 1, 49.6% PBS versus 34.2% MSC; cluster 2, 22.8% PBS versus 31.8% MSC). Interestingly, cluster 3 was present predominantly in the MSC group (31.2% MSC versus 2.4% PBS), while cluster 4 was present almost exclusively in the PBS group (4.6% MSC versus 24.9% PBS) (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

hMSC Infusion Is Associated with Differently Distributed Macrophage Subpopulations in the Wound

(A) Graph-based clustering of Adgre1+ macrophages by treatment group reveals four transcriptionally distinct macrophage subpopulations. (B) Contribution of each macrophage cluster defined in (A) to each treatment group. (C) Heatmap showing the 20 most upregulated genes in each macrophage cluster defined in (A). (D) Gene expression patterns of selected enriched genes in individual clusters (expressed as log2).

To gain insight into the functions of each macrophage cluster, we used the “locally distinguishing genes” feature in Loupe Cell Browser to identify significantly enriched genes in each subpopulation relative to the others (Figure 4C and 4D; Tables S1–S4). Cluster 1 enriched genes included Gas6, Cd163, and Mrc1, known markers of M2 macrophages, representing an anti-inflammatory phenotype involved in resolving inflammation and promoting tissue repair and remodeling.24 Cluster 2 enriched genes included few genes with known macrophage functions in the literature, except for Mmp19, a matrix metalloproteinase whose role in wound healing remains unknown. Cluster 3, the subpopulation present principally in the MSC group, exhibited high expression levels of Prg4, Arg1, Slpi, Vsig4, and Cd9, which have been shown to have anti-inflammatory functions. Interestingly, S100a8, S100a9, and Serpinb2 were also highly upregulated. These genes are decreased in chronic non-healing wounds in humans25 and induce other genes involved in the activation of complement factors that promote phagocytosis by macrophages, resolving inflammation and promoting angiogenesis.26 Recently, pre-treatment of MSCs with S100A8/A9 has been shown to enhance their ability to promote wound healing.27 Finally, cluster 4, present predominantly in the PBS group and depleted following MSC treatment, exhibited enrichment for the pro-inflammatory cytokine Cxcl10,28 as well as Ly6c1 and Ly6c2, which form the Ly6c complex that is highly expressed in inflammatory monocytes and macrophages.29

Enrichment Analyses of Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal Distinct Cellular Processes Associated with Each Macrophage Subpopulation

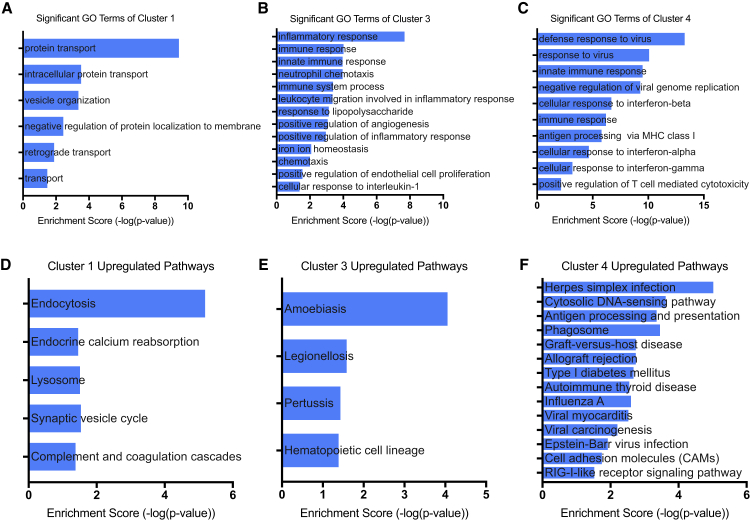

Using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery) bioinformatics software,30,31 we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analyses to identify upregulated biological processes and pathways within each macrophage subpopulation. Differentially expressed genes were classified into different functional categories based on the biological processes of the GO classification. The number of significantly enriched GO terms identified based on upregulated genes were 7 in cluster 1, 13 in cluster 3, and 12 in cluster 4 (filtered by p value <0.05). No enriched biological processes were detected in cluster 2. GO analysis showed that compared with the other clusters, cluster 1 had unique upregulated biological processes pertaining to endocytosis, suggesting that this is a phagocytic population (Figure 5A). No GO terms pertaining to endocytosis or phagocytosis were significantly upregulated in the other clusters. Clusters 3 and 4 both exhibited enrichment for “immune response” and “innate immune response” (Figures 5B and 5C). Notably, cluster 3 uniquely expressed “positive regulation of angiogenesis” and “positive regulation of endothelial cell proliferation,” supporting a pro-angiogenic role (Figure 5B). Cluster 4 exhibited enrichment for several GO terms pertaining to cellular defense against viral infection (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Enrichment Analyses of Differentially Expressed Genes Reveal Distinct Cellular Processes Associated with Each Macrophage Subpopulation

(A–C) Significant GO terms for upregulated genes in each macrophage subpopulation. (D–F) Significant pathways for upregulated genes in each macrophage subpopulation identified by KEGG pathway analysis. (A and D) cluster 1, (B and E) cluster 3, (C and F) cluster 4.

KEGG pathway analysis was used to examine involved biological pathways of the differentially expressed genes in each cluster. Cluster 1 exhibited 5 enriched pathway terms, cluster 3 exhibited 4 enriched pathway terms, and cluster 4 exhibited 14 enriched pathway terms. There was no overlap in enriched pathways between the clusters. Cluster 1 enrichment for “lysosome” and “endocytosis” further supports a phagocytic role of this subpopulation (Figure 5D). Cluster 3 was highly enriched for pathways related to bacterial infection as well as “hematopoietic cell lineage” (Figure 5E). Cluster 4 exhibited a strikingly higher number of enriched pathways, with most pathways corresponding to highly inflammatory states, including herpes simplex infection, graft-versus-host disease, allograft rejection, and “type I diabetes” (Figure 5E).

Taken together, these results suggest that the majority of macrophages, characterized as cluster 1 and cluster 2, remain unchanged between the MSC and PBS group. However, MSC treatment was associated with a near elimination of pro-inflammatory macrophages (cluster 4) and emergence of pro-angiogenic Cd9+ macrophages (cluster 3) that are transcriptionally distinct from traditionally described “activated macrophages” defined by Cd163 and Mrc1 expression.

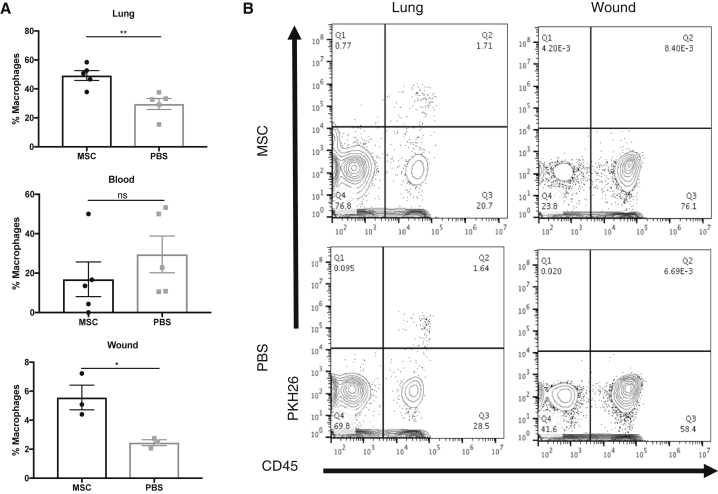

CD9+ Macrophages in the Wound Do Not Originate from the Lung

We next investigated the origin of Cd9+ wound macrophages and the biology by which their induction is mediated. Using flow cytometry, we confirmed that the number of Cd9+ macrophages as a percentage of total macrophages is increased in both the lung (p < 0.01) and wound (p < 0.05) 2 days following MSC infusion (Figure 6A). The percentage of Cd9+ macrophages in the blood was not significantly different between treatment groups. Since Cd9+ macrophages were much more abundant in the lung compared to the wound, we hypothesized that the Cd9+ macrophages appearing in the wound were alveolar macrophages mobilized by the presence of hMSCs entrapped in the lung. To test our hypothesis, the fluorescent dye PKH26 was delivered intranasally to mice to selectively label phagocytic cells in the lung. Two days after administration, nearly all F4/80+ macrophages in the lung were PKH26+, while no PKH26 signal was detectable in the bone marrow and blood (Figure S5), confirming that only alveolar macrophages were labeled using intranasal delivery of PKH26. To test whether any of the PKH26+ lung macrophages mobilize to the wound following treatment, mice were given excisional wounds 2 days following intranasal delivery of PKH26 and treated with hMSCs or PBS. PKH26+ cells were not detected in wounds 2 days following treatment in either treatment group, confirming that the increased presence of CD9+ macrophages in the wound is not due to mobilization of resident lung macrophages (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

CD9+ Wound Macrophages Do Not Originate from the Lung

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of Cd9 expression on macrophages in vivo. Bar graphs depict number of Cd9+ macrophages as percentage of total macrophages in the lung, wound, and blood harvested from mice 2 days following excisional wounding and administration of hMSCs or PBS. The percentage of Cd9+ macrophages is significantly increased in the lungs and wounds of mice treated with hMSCs compared to PBS (n = 3). Data are representative of three separate experiments. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of lung and wound from mice 2 days following excisional wounding and administration of hMSCs or PBS. Phagocytic cells in the lung were labeled via intranasal administration of PKH26 2 days prior to wounding and treatment. PKH26-labeled Cd45+ hematopoietic cells are detectable in lungs from both MSC and PBS treatment groups, but not in the wounds harvested from either treatment group. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

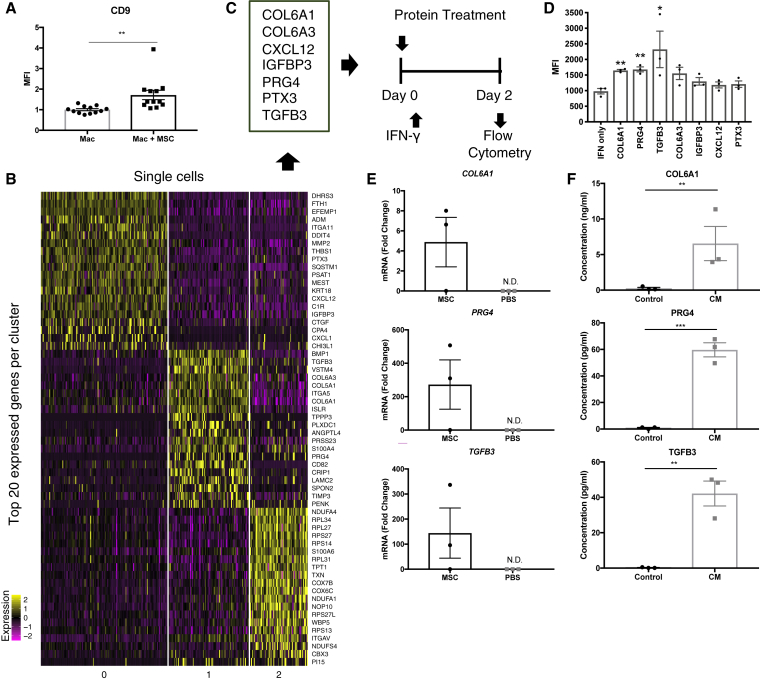

hMSCs Induce CD9 Expression in Macrophages via Secretion of Multiple Proteins

Given that Cd9+ macrophages in the wound are not resident lung macrophages, we hypothesized that hMSCs induce Cd9 expression in circulating macrophages as they pass through the lung. To determine whether Cd9 expression is induced by soluble proteins secreted by hMSCs, we co-cultured RAW264.7 macrophages with hMSCs using a transwell system. Because RAW264.7 macrophages highly express Cd9 when cultured in vitro,32,33 we stimulated the cells with interferon (IFN)-γ for 48 h to reduce Cd9 expression prior to co-culture with hMSCs (Figure S6). After 2 days of co-culture, Cd9 expression was evaluated using flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Cd9 was significantly increased in macrophages co-cultured with hMSCs in a transwell compared to macrophages cultured alone (p < 0.01), confirming that factors secreted by hMSCs, and not direct contact or phagocytosis of hMSCs, is sufficient for induction of Cd9 expression (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

hMSCs Induce Cd9 Expression in Macrophages via Secretion of Multiple Proteins

(A) Cd9 expression on human macrophages cultured alone (Mac) and co-cultured with hMSCs within a transwell system (Mac + MSC). Bar graph depicts normalized MFI of Cd9 expression from four pooled experiments (n = 12). (B) Heatmap of single-cell RNA-seq of hMSCs isolated from lung 1 day following retro-orbital infusion. Heatmap depicts the 20 most upregulated genes in three transcriptionally distinct hMSC subpopulations. (C) Schematic diagram of the experimental design to screen for proteins that induce Cd9 expression in human macrophages. Seven candidate proteins were identified based on RNA-seq data. Raw264.7 macrophages were co-treated with IFN-y and human recombinant protein for 2 days before being subjected to flow cytometry to evaluate Cd9 expression. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of CD9 expression on Raw264.7 macrophages following 2-day treatment with human recombinant proteins. Bar graph represents MFI of Cd9 expression in each treatment group. n = 3. ∗p < 0.05, by ANOVA. (E) RT-PCR assays for human-specific mRNAs in lung 2 days after retro-orbital infusion of hMSCs. Values are fold increase over values for cultured hMSCs, normalized by ΔΔCt for GAPDH. n = 3. (F) Levels of soluble COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3 are detectable in hMSC conditioned media as determined by ELISA. n = 3. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

To identify proteins that could be responsible for Cd9 macrophage activation, we performed scRNA-seq of MSCs entrapped in the lung to examine their transcriptional activity (Figure 7B). GFP-hMSCs were administered retro-orbitally to mice 1 h after excisional wounding, and lungs were harvested and digested 24 h later. Single GFP-hMSCs were sorted into 96-well plates for scRNA-seq analysis. After application of quality control filters, 284 cells from five pooled lungs were included in the scRNA-seq analysis. The cells expressed expected positive hMSC markers THY1, NT5E, and ENG (Figure S7A). Expression of negative hMSC markers CD45, CD34, and CD14 was not detected (data not shown).

We applied unsupervised Seurat-based clustering to identify transcriptionally distinct MSC subpopulations and identified three cell clusters (Figure S7B). A heatmap was generated to identify the 20 most upregulated genes in each cluster to gain insight into their biological functions. To identify protein candidates that might mediate Cd9 expression in macrophages, we performed a literature search of all highly expressed genes in the heatmap and identified seven genes encoding for secreted proteins that have previously been implicated in macrophage polarization (i.e., Col6a1, Col6a3, Cxcl12, Igfbp3, Prg4, Ptx3, and Tgfb3) (Figure 7C). We evaluated the ability of the corresponding human recombinant proteins to induce Cd9 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages in vitro. Macrophages were co-treated with IFN-γ and each human recombinant protein for 48 h and subjected to flow cytometry to evaluate Cd9 expression. Three of the candidate proteins tested (COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3) significantly increased the MFI of Cd9 expression in macrophages compared to the IFN-γ-only control group (IFN-γ only, 981.3 ± 87.17 arbitrary units [a.u.]; COL6A1, 1,646 ± 31.07 a.u.; PRG4, 1,680 ± 79.39 a.u.; TGFB3, 2,322 ± 585.2 a.u.; n = 3, p < 0.05) (Figure 7D). COL6A1, or collagen VI, has been shown in vitro to promote macrophage migration and polarization via the AKT and protein kinase A (PKA) pathways. Col6a1−/− macrophages exhibit impaired migration and reduced M2 polarization, and in vivo, macrophage recruitment and M2 polarization are also impaired in knockout mice after nerve injury, leading to delayed nerve regeneration.34 PRG4 has been demonstrated to play an anti-inflammatory role in macrophages both in vitro and in vivo. Treatment with recombinant human (rh)PRG4 reduced production of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, and MCP-1 by macrophages in conditions of inflammatory arthritis,35 and it has been suggested that PRG4 mediates inflammatory process through interactions with CD44,36 Toll-like receptors.37 The TGF superfamily has also been implicated in M2 polarization. Macrophages in mice lacking the TGF superfamily receptor TβRIII exhibited reduced expression of genes known to play a role in M2 polarization, suggesting that TGF-β signaling is essential for this process.38 Taken together, the literature supports that high expression of these genes by hMSCs while entrapped in the lung can mediate macrophage phenotypes toward an anti-inflammatory state.

To confirm our hMSC scRNA-seq data and verify that gene expression by hMSCs was limited to lung tissue, we evaluated whether human mRNA encoding each of these proteins was detectable in the wound and lung 1 day after wounding and treatment using qRT-PCR. Human ACTB was expressed only in lungs harvested from hMSC-treated mice, further supporting that hMSCs are entrapped in the lung and do not migrate to the wound during the first 24 h following injection. Expression of human COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3 in the treated lung (Figure 7E) but not the wound (data not shown) was detected, confirming the hMSC scRNA-seq data. The presence of secreted COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3 in hMSC-conditioned media was detected by ELISA, demonstrating that expression of genes led to translation of secreted protein (Figure 7F), and suggesting that MSCs secrete these factors intrinsically, not requiring stimulation by inflammatory signals from the wound. The intrinsic therapeutic nature of MSCs is further supported by scRNA-seq data comparing the transcriptional profiles of MSCs harvested directly from in vitro culture and 24 h following entrapment in the lung. Our analysis revealed no significant differences in gene expression between MSC groups (Figure S7C).

In conclusion, scRNA-seq analysis of hMSCs entrapped in the lung for 24 h after infusion revealed several highly expressed genes encoding for soluble proteins that are implicated in macrophage polarization. We demonstrate that treatment with multiple proteins (COL6A1, PRG4, and TGFB3) significantly induces Cd9 expression in macrophages and confirms their presence in hMSC conditioned media. The validation of these proteins suggests that the induction of Cd9+ macrophages is not limited to a single factor and highlights the complexity of MSC therapeutic mechanisms (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed Model of Mechanism for MSC-Induced Macrophage Activation and Acceleration of Wound Healing

Intravenous infusion of culture-expanded hMSCs (green cells) leads to pulmonary entrapment of cells. Cd9+ macrophages are activated via the secretome of infused hMSCs (e.g., PRG4, TGFB3, and COL6A1). Pro-angiogenic CD9+ macrophages appear in the wound and accelerate tissue repair.

Discussion

Multiple studies have indicated that MSC accumulation to sites of inflammation following delivery correlates with improved therapeutic outcomes,39,40 but it is becoming increasingly evident that i.v. infusion of MSCs leads to pulmonary entrapment and rapid clearance from the body without long-term incorporation.11 There have been many efforts to improve MSC homing under the assumption that it will improve outcomes.41,42 Despite their transient presence, i.v. infusion of MSCs has demonstrated significant therapeutic potential in multiple preclinical models and clinical trials,1, 2, 3 but the mechanism by which this occurs remains elusive.

In the present study, we demonstrate that similar to other studies, MSCs are sequestered in the lung and cleared rapidly from recipient mice.11,43 Unlike other studies, we did not observe redistribution of live cells to other tissue in three models of ischemia using two separate modalities. This may be because IVIS imaging is insufficiently sensitive to detect small numbers of cells localizing to tissue, and our flow cytometry analysis was limited to lung, wound, and spleen tissue. However, even if a small number of MSCs was present in other organs, it is unlikely that their magnitude is sufficient to have a therapeutic effect. Similar to other studies, we demonstrated that the effect of MSC infusion on tissue repair is significant, observing acceleration of time to closure using an excisional wound model, and we show that the therapeutic effect of i.v. infusion is comparable to direct injection of hMSCs in the context of excisional wound healing.

Recently, much attention has been placed on the ability of MSCs to induce macrophage polarization.4,5,44 For example, Ko et al.4 showed that following MSC infusion, lung monocytes and macrophages were preconditioned toward an immunoregulatory phenotype in a Tsg-6-dependent manner, protecting mice against immune challenges in models of ocular inflammation. A subsequent study showed that monocytes engulf MSCs entrapped in the lung and migrate to other sites in the body, distributing the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs.44 However, MSC-mediated macrophage polarization studies are typically limited by investigation of a single macrophage marker, particularly upregulation of the M2 marker Cd209. There is increasing evidence that M1 and M2 phenotypes are insufficient to characterize macrophage heterogeneity and account for phenotypes specific to different tissues of origin and inflammatory states.45

To comprehensively understand the effects of MSC infusion without introducing bias with study of a single surface marker, we utilized scRNA-seq to characterize immune cell populations in the wound shortly after MSC infusion. The identification of four transcriptionally distinct macrophage subpopulations in our study challenges the M1/M2 macrophage paradigm and highlights the limitations of using single markers to infer potential functional properties of macrophage subpopulations. It could be argued that MSC group-enriched cluster 3 and PBS group-enriched cluster 4 resemble pro-regenerative M2 and pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, respectively, but we observe substantial overlap in the expression of markers commonly used to define M1 and M2 subsets among all four clusters, with high expression of Gas6 and Cd163 in cluster 1 being particularly confounding.

Our transcriptional analysis revealed a novel subset of macrophages that appear in the wound following MSC infusion, defined by Cd9 expression. GO term analysis suggests that this population may be involved in vasculature development, and its increased presence may in part explain increased formation of blood vessels observed in MSC-treated wounds. An equally important finding from our transcriptional data was that in addition to identifying a subpopulation of macrophages that appears in the wound following MSC infusion, we observed a depletion of inflammatory Ly6c+ macrophages in wounds following MSC infusion. High expression of Ly6c is a known marker of inflammatory monocytes and macrophages, and it has previously been demonstrated that in diabetic wounds, Ly6Chi cells fail to transition to a Ly6Clo phenotype, contributing to delayed healing.46 This suggests that in addition to promoting latter regenerative phases of tissue repair, MSC treatment may help resolve chronic inflammation, a state associated with non-closing wounds typically seen in diabetic and aging patients,17 by inducing a phenotypic switch toward a Ly6Clo phenotype. Future studies should investigate the components of the MSC secretome that regulate this phenotypic switch.

The process by which MSCs regulate macrophage subpopulation dynamics to accelerate tissue repair still remains unclear. Given that MSCs are entrapped in the lung, we expected macrophages to transition into the Cd9+ phenotype locally in the lung. Our flow cytometry results confirmed that the number of Cd9+ macrophages was significantly increased in both the lung and wound, supporting our hypothesis. However, we did not observe a significant difference in the percentage of Cd9+ macrophages in the blood between treatment groups, but this may be because the collected blood samples contain all circulating macrophages, including those that would not yet have passed through regions where they might come into contact with the MSC secretome. We additionally eliminated the possibility that resident alveolar macrophages are induced into Cd9+ macrophages and mobilized to the wound, suggesting that it is circulating macrophages that are undergoing the phenotypic switch to a Cd9+ state.

Our protein screen identified three proteins (COL6a1, PRG4, and TGFB3) secreted by MSCs that upregulate CD9 expression in macrophages in vitro. All three of these proteins have previously been implicated in wound healing. Col6a1−/− mice exhibit decreased tensile strength of the skin and delayed hair cycling and growth under physiological conditions, whereas addition of purified collagen VI rescues the abnormal wound-induced hair regrowth through activation of the Wnt/b-catenin signaling pathway.47,48 In mice, expression of Prg4 was necessary to stimulate regeneration of skeletal elements in mouse digit amputation wounds using Bmp2 and Bmp9.49 Prg4 is also upregulated following treatment with sodium hyaluronate, which has been shown to improve digit mobility when administered around repaired tendons.50 Finally, there is evidence that Tgfb3 is essential for wound healing, and treatment with exogenous Tgfb3 improves wound healing and reduces scar tissue formation. Tgfb3 is necessary for wound closure, as wounds injected with neutralizing antibody against Tgfb3 show increased epidermal volume and proliferation in conjunction with a delay in keratinocyte migration.51 Excisional wounds treated with MSCs that were genetically modified to overexpress Tgfb3 in a rabbit model demonstrated reduced scar depth and density.52

While we attribute the induction of Cd9+ macrophages to at least these three proteins, this is not an exhaustive list. Our study represents a single snapshot of wound healing, and it is possible that MSC infusion significantly affects resident cells at other time points that were not captured in this study. Our day 2 time point was selected to capture MSC activity while infused cells were still present in the lung. Day 2 corresponds with the initial inflammatory phase, in which chronic wounds are typically stalled due to an inability to clear neutrophils from the wound site. Future studies should characterize how MSC delivery at later time points stages of wound healing (angiogenesis and remodeling) affects resident cell populations and outcomes. Moreover, our inferences on Cd9+ macrophage function are limited to conclusions drawn from gene expression analyses, as the population is too rare to allow for isolation and in vitro characterization. Further exploration of the genes and proteins identified in this study may allow for better characterization of macrophage subpopulations and their functions in multiple contexts of tissue disorders.

The dosing in this study was determined using dose escalation studies to determine the maximum number of cells that could be safely administered to observe a therapeutic effect. Several other studies have used the same or higher dosing to investigate therapeutic effects of MSCs in mouse models,4,53,54 but it would be necessary to repeat these experiments at a clinically relevant dose, given that current clinical trials typically deliver human doses ranging from 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 MSCs/kg of body weight. In addition, future studies should optimize timing of delivery. In this study, cells were administered 1 h after wounding, which may not be clinically feasible. Given that MSC infusion induced a phenotypic change in macrophages, it is possible that MSC therapy may be used to precondition a healing response prior to wounds developing, specifically in patients who suffer from chronic wounds. Additional experiments to evaluate the efficacy of treatment administered at different phases of healing would be beneficial.

The multitude of research papers proposing MSC mechanisms of action highlights that the activity of MSCs is complex and that their clinical benefit cannot be attributed to a single protein or pathway. Despite their complexity, identifying facets of their therapeutic benefit will help guide timing and modalities for delivery, appropriate treatment indications, and improve genetic engineering efforts to optimize their intrinsic therapeutic ability.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6- to 8-week-old female BALB/cJ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (catalog no. 651, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animal care was provided in accordance with the Stanford University School of Medicine guidelines and policies for the use of laboratory animals.

MSC Culture

hMSCs were obtained from Genlantis (catalog no. SH49205, San Diego, CA, USA). GFP-expressing MSCs derived from BALB/c mice (GFP-mMSCs) were obtained from Cyagen Biosciences (catalog no. MUCMX-01101, Guangzhou, China). Cells were cultured in standard minimal essential medium-alpha (MEM-α) (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 16.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Culture medium was replaced twice weekly. After reaching 70%–80% confluency, plastic adherent cells were harvested with 2.5 mg/mL trypsin/1 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) for 5 min at room temperature. For expansion, cells were seeded in 175-cm2 cell culture flasks (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a density of 10,000 cells/cm2. Cells were used for experiments between passage 4 and 6. For i.v. infusion, cells were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/mL.

Macrophage Cell Culture

The mouse macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 (TIB-71) was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days. Upon reaching 60%–75% confluency, cells were harvested using a cell scraper and seeded in 15-mm cell culture dishes with a dilution of 1:10. For in vitro experiments, macrophages were seeded either at a density of 1 × 105 per well in six-well plates or 2.5 × 104 per well in 24-well plates. After overnight recovery, macrophages were activated with 500 U/mL recombinant mouse IFN-γ (ab9922, Abcam) for 48 h prior to MSC co-culture or co-treated with human recombinant proteins PTX3 (catalog no. 1826-TS, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), CXCL12 (catalog no. 350-NS-010, R&D Systems), IGFBP3 (catalog no. ab49831, Abcam), CXCL1 (catalog no. 275-GR, R&D Systems), TGFB3 (catalog no. 8420-B3, R&D Systems), COL6A1 (catalog no. LS-G14813, R&D Systems), COL6A3 (catalog no. PKSH030495, Elabscience, Wuhan, China), ANGPTL4 (catalog no. 4487-AN, R&D Systems), PRG4 (catalog no. ab153060, Abcam), and TIMP3 (catalog no. 973-TM, R&D Systems).

Generation of fLuc+GFP+ hMSCs

Gene integration was performed on hMSCs cultured to 80%–90% confluency. Mixtures of trypsinized hMSCs (5,000 cells/μL in Opti-MEM I) with single guide RNA (sgRNA) and Cas9 5′ MeC, ψ-mRNA (0.1 μg/μL 2′-O-methyl-3′-phosphorothioate (MS)-modified sgRNA with 0.15 μg/μL Cas9 mRNA) were electroporated with pulse code CM-119 on the Lonza 4D Nucleofector (as 20-μL or 100-μL reactions) and immediately diluted with 2× vol of Opti-MEM I. Immediately, 1.0 × 105 vector genomes/cell of fLuc rAAV6 template were added to the mixture and cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Then, MSC-AAV6 mixtures were seeded at ∼220 cells/cm2 in complete culture medium. AAV6-containing medium was replaced 48 h later with complete culture medium. Expanded GFP+ hMSCs were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and subjected to luciferase assay to confirm chemiluminescence in vitro.

Excisional Wound Model

8-week-old BALB/cJ female mice were depilated and one or two 6-mm full-thickness wounds extending through the panniculus carnosus were made at the same level on the dorsum of the mice on either side of the midline as previously described.23 A donut-shaped silicone splint with a 10-mm diameter was centered around the wound and affixed to the skin using adhesive (Krazy Glue) and interrupted 6-0 nylon sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). For the wound-healing kinetics study, mice were randomized to two treatment groups: PBS (vehicle control) or hMSCs (n = 5 animals per group, 10 wounds per group). Mice treated retro-orbitally with MSCs received 1 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μL of PBS, while those treated locally with MSCs received 2.5 × 105 cells suspended in 80 μL of PBS at four points equidistant along the edge the wound. Both groups were treated 1 h after wounding. Mice in the PBS vehicle control group received 100 μL of PBS retro-orbitally at the same time. Wounds were covered with Tegaderm (3M, Maplewood, MN, USA), which was changed every other day, at which times digital images were taken until wound closure, defined as the time at which the wound was fully re-epithelialized. Wound area was quantified using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) and expressed as a percentage of the original wound area.

Ischemic Flap

A quantitative and reproducible model of graded ischemia was created on the dorsal surface of the mouse, as previously described.55 Briefly, a full-thickness three-sided peninsular flap (1.25 cm long × 2.5 cm wide) that includes the epidermis, dermis, and underlying adipose tissue was created. The skin tissue was raised from the underlying muscular bed, and a 0.13-mm-thick silicone sheet (Invotec International, Jacksonville, FL, USA) was inserted under the flap to separate the skin from the vasculature in the underlying tissue. The flap was closed using interrupted 6-0 nylon suture (Ethicon). Mice were randomized to two treatment groups: PBS (vehicle control) or GFP-hMSCs (n = 3). Mice treated with GFP-hMSCs received 1 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μL of PBS injected retro-orbitally 1 h after wounding. Mice in the PBS vehicle control group received 100 μL of PBS retro-orbitally at the same time. The flap and lung were harvested 1, 2, or 3 days after injection and subjected to flow cytometry.

Hindlimb Ischemia

A murine model of hindlimb ischemia (HLI) was made on 8-week-old female BALB/cJ mice, as previously described.56 Animals were anesthetized and unilateral HLI was induced by two separate ligations of the femoral artery, one distal and one proximal to the origin of the deep femoral branch with 10-0 nylon suture (Ethicon). The overlying skin was closed with 6-0 nylon suture (Ethicon) and MSCs or PBS was administered retro-orbitally 1 h after wounding. The femoral artery and surrounding adipose tissue and vasculature were harvested 1, 2, or 3 days after injection and subjected to flow cytometry.

Histology and Immunostaining

Wounds from the excisional model were harvested upon closure and immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated with sequential ethanol concentrations (30%, 50%, 70%, and 95%), xylene, and paraffin washes, and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. To evaluate dermal integrity, wound sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome and visualized using light microscopy. Stained pixels per high magnification field were quantified using ImageJ.

In Vivo BLI Imaging

BLI imaging was used to assess the distribution of luciferase+ cells in mice. Mice were anesthetized and injected intraperitoneally with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (Biosynth International, Itasca, IL, USA) in PBS. Images were obtained after 10 min with a cooled CCD camera using the Xenogen IVIS 200 system (Caliper Life Sciences, Mountain View, CA, USA). Bioluminescent signal was quantified using Living Image software v4.5.2 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Flow Cytometry

Tissue was minced and digested using collagenase A (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 25 min at 37°C. The digestion was quenched with FACS buffer (Hanks’ balanced salt solution [Gibco] supplemented with 5% FBS [Gibco]) and strained through a 100-μm cell strainer. The cells were centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 8 min at 4°C and the resulting pellets were stained with anti-mouse CD45 (catalog no. 368539, BioLegend), F4/80 (catalog no. 123116, BioLegend), and CD9 (catalog no. 124808, BioLegend). After incubation, cells were washed with FACS buffer and analyzed using CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo v10.4.

scRNA-Seq

For 10x scRNA-seq of the wound, a single-cell suspension was prepared from five pooled mouse excisional wounds per group that were harvested and digested with collagenase A (Roche) 2 days after wounding as described above. Single cells were encapsulated in droplets using 10x Genomics GemCode Technology and processed following the manufacturer’s specifications. Briefly, every cell and every transcript were uniquely barcoded using a unique molecular identifier (UMI). cDNA ready for sequencing on Illumina platforms was generated using a single cell 3′ reagent kit v2 (10x Genomics). Libraries were sequenced on NextSeq 500. For MSC scRNA-seq, GFP+ cells were sorted into 96-well plates with 4 μL of per well of lysis buffer consisting of 1 U/μL recombinant RNase inhibitor (RRI) (catalog no. 2313B, Takara Bio, Mountain View, CA, USA), 0.1% Triton X-100 (catalog no. 85111, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2.5 mM dNTP (2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate) (catalog no. 10297018, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 2.5 μM oligodT30VN (5′-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACT30VN-3′, Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). Once sorted, cells were immediately spun down and frozen at −80°C. scRNA-seq was performed as previously described57 using SMARTscribe (catalog no. 639538, Takara Bio) for reverse transcription; 25 cycles of amplification were performed using Hifi HotStart ReadyMix (2×) (catalog no. KK2602, Roche). Amplified cDNAs were purified by bead cleanup using a Biomek FX automated platform, and aliquots were run on a Fragment Analyzer for quantitation. Barcoded sequencing libraries were made using the miniaturized Nextera XT as previously described58 in a total volume of 4 μL. Pooled libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 high-output kit.

scRNA-Seq Data Analysis

Initial data processing for 10x data was performed using the Cell Ranger version 2.0 pipeline (10x Genomics). Loupe Browser files for MSC- and PBS-treated datasets were aggregated using the aggregate function in the Cell Ranger pipeline. Clustering and gene expression were visualized with 10x Genomics Loupe Cell Browser v.2.0.0. Gene ontologies of macrophage clusters were assessed using the panther overrepresentation test (Gene Ontology Consortium, http://geneontology.org/), with the reported p values corrected by the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

The R package Seurat v2.3.059 was used for quality control (QC), analysis, and exploration of MSC scRNA-seq data using R v3.4.4. Gene counts were tabulated from STAR v2.5.4b60 mapping against human hg38 reference and used as input to Seurat. The counts coincide with those produced by htseq-count with default parameters. Genes expressed in at least 20 cells and cells with at least 500 expressed genes were retained for further analysis. Gene expression measurements for each cell were normalized by their total expression, scaled by 10,000, and log transformed. Following normalization, genes that varied between single cells were identified. Principal-component analysis (PCA) was performed on genes to output a set of genes that most strongly defined a set of principal components. The standard deviations of the principal components were plotted to decide on how many principal components to use, with a cutoff drawn where there was a clear elbow in the graph. Seurat’s graph-based clustering approach was used to cluster the cells. Seurat was further used to perform t-SNE clustering, which placed cells with similar local neighborhoods in high-dimensional space together in low-dimensional space. Positive and negative markers in each cluster were identified by comparing genes in cells of one cluster against genes in all other cells. Only genes that were detected in at least 25% of cells in either of the two populations were tested. Feature plots of gene expression of ENG, NT5E, and THY1 gene markers were visualized on a t-SNE dimensional reduction plot by coloring single cells by choosing expression of these gene markers as the feature. Finally, a heatmap of the top 20 marker genes across all cells in the three clusters was plotted.

In Vivo Labeling of Alveolar Macrophages

BALB/cJ mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane. The fluorescent dye PKH26-PCL (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was diluted under sterile conditions with diluent B to a final concentration of 10 μM. A total volume of 100 μL of the diluted solution was administered intranasally, allowing for selective labeling of phagocytic cells in the lung.61

GO and KEGG Pathway Analysis

Gene lists were uploaded into DAVID v6.8.30,31 The Functional Annotation tool was used to identify significantly enriched GO terms related to biological processes. KEGG pathway analysis was used to identify pathways correlated with cluster-specific genes. p values were generated following Benjamini-Hochberg correction, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

qRT-PCR Analysis of Mouse Tissue

Total RNA was obtained from mouse tissue using an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). RNA expression of selected genes was measured using qRT-PCR. Briefly, 150 ng of purified RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each cDNA sample was combined with PrimeTime predesigned qPCR probe assays (Hs.PT.58.1756331, Hs.PT.58.25629124, Hs.PT.25591139, Hs.PT.58.25480012, Hs.PT.58.25699746, Hs.PT.58.39039397, Hs.PT.39a.22214847, Mm.PT.39a.22214843.g) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA), PrimeTime qPCR gene expression master mix (Integrated DNA Technologies), and RNase-free water in a 384-well plate. Gene expression was determined using the QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cycling conditions were 3 min at 95°C for 1 cycle, then 15 s at 95°C, followed by 1 min at 60°C for 40 cycles. The gene expression was quantified using the ΔΔCt method, and fold change values were reported as 2−ΔΔCt. The relative amount of each target gene was normalized to GAPDH and reported as fold increase over values for cultured hMSCs. All reactions were carried out in triplicate.

Conditioned Media Collection and Protein Analysis by ELISA

1.5 × 106 hMSCs were cultured in 10 mL of serum-free MEM-α (Gibco) for 5 days. Media were collected into a 15-mL tube and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm in a centrifuge at 4°C for 15 min. Supernatant was transferred into 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C until analysis. ELISAs for COL6A1 (NBP2-75878, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA), PRG4 (KTE61165, Abbkine, Wuhan, China), and TGFB3 (OKEH02925, Aviva Systems Bio, San Diego, CA, USA) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were generated by plotting a four-parameter logistic curve fit. Concentrations of samples were determined from the standard curves.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism 7. Sample sizes (n), p values, and applied tests are indicated in the figure legends. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Two-tailed tests were applied.

Study Approval

All protocols were approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Author Contributions

N.K. and G.C.G. designed experiments. N.K., W.S., C.A.B., H.K., K.C., B.A.K., Z.N.M., and C.N. conducted experiments data. N.K. analyzed data. M.H.P. provided reagents. M.H.P., M.T.L., and G.C.G. provided supervision. N.K. and G.C.G. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

scRNA-seq was completed by Dhananjay Wagh and Sopheak Kim at the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility. Analysis of the MSC scRNA-seq data was performed by Ramesh Nair at BaaS at the Stanford Genetics Bioinformatics Service Center and supported by NIH grant P30DK116074. Flow cytometric analysis was completed at the FACS Core at the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine. We thank Yujin Park for assistance with histology. Funding was provided by the Hagey Family Endowed Fund in Stem Cell Research and the NIH (R01-DK074095).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.05.022.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Le Blanc K., Rasmusson I., Sundberg B., Götherström C., Hassan M., Uzunel M., Ringdén O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honma T., Honmou O., Iihoshi S., Harada K., Houkin K., Hamada H., Kocsis J.D. Intravenous infusion of immortalized human mesenchymal stem cells protects against injury in a cerebral ischemia model in adult rat. Exp. Neurol. 2006;199:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee R.H., Pulin A.A., Seo M.J., Kota D.J., Ylostalo J., Larson B.L., Semprun-Prieto L., Delafontaine P., Prockop D.J. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko J.H., Lee H.J., Jeong H.J., Kim M.K., Wee W.R., Yoon S.O., Choi H., Prockop D.J., Oh J.Y. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells precondition lung monocytes/macrophages to produce tolerance against allo- and autoimmunity in the eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:158–163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522905113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q.Z., Su W.R., Shi S.H., Wilder-Smith P., Xiang A.P., Wong A., Nguyen A.L., Kwon C.W., Le A.D. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells elicit polarization of M2 macrophages and enhance cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1856–1868. doi: 10.1002/stem.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bantubungi K., Blum D., Cuvelier L., Wislet-Gendebien S., Rogister B., Brouillet E., Schiffmann S.N. Stem cell factor and mesenchymal and neural stem cell transplantation in a rat model of Huntington’s disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2008;37:454–470. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathiasen A.B., Jørgensen E., Qayyum A.A., Haack-Sørensen M., Ekblond A., Kastrup J. Rationale and design of the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intramyocardial injection of autologous bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stromal cells in chronic ischemic heart failure (MSC-HF Trial) Am. Heart J. 2012;164:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hare J.M., Traverse J.H., Henry T.D., Dib N., Strumpf R.K., Schulman S.P., Gerstenblith G., DeMaria A.N., Denktas A.E., Gammon R.S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim I., Bang S.I., Lee S.K., Park S.Y., Kim M., Ha H. Clinical implication of allogenic implantation of adipogenic differentiated adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014;3:1312–1321. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caplan A.I., Sorrell J.M. The MSC curtain that stops the immune system. Immunol. Lett. 2015;168:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggenhofer E., Benseler V., Kroemer A., Popp F.C., Geissler E.K., Schlitt H.J., Baan C.C., Dahlke M.H., Hoogduijn M.J. Mesenchymal stem cells are short-lived and do not migrate beyond the lungs after intravenous infusion. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:297. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S., Guo L., Ge J., Yu L., Cai T., Tian R., Jiang Y., Zhao R.Ch., Wu Y. Excess integrins cause lung entrapment of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:3315–3326. doi: 10.1002/stem.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer U.M., Harting M.T., Jimenez F., Monzon-Posadas W.O., Xue H., Savitz S.I., Laine G.A., Cox C.S., Jr. Pulmonary passage is a major obstacle for intravenous stem cell delivery: the pulmonary first-pass effect. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:683–692. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao F., Chiu S.M., Motan D.A., Zhang Z., Chen L., Ji H.L., Tse H.F., Fu Q.L., Lian Q. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2062. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prockop D.J. Concise review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2042–2046. doi: 10.1002/stem.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh T.J., DiPietro L.A. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2011;13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigues M., Kosaric N., Bonham C.A., Gurtner G.C. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99:665–706. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantovani A., Biswas S.K., Galdiero M.R., Sica A., Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J. Pathol. 2013;229:176–185. doi: 10.1002/path.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovani A., Sica A., Locati M. Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity. 2005;23:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez F.O., Helming L., Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu W., Fu C., Song L., Yao Y., Zhang X., Chen Z., Li Y., Ma G., Shen C. Exposure to supernatants of macrophages that phagocytized dead mesenchymal stem cells improves hypoxic cardiomyocytes survival. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013;165:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luk F., de Witte S.F.H., Korevaar S.S., Roemeling-van Rhijn M., Franquesa M., Strini T., van den Engel S., Gargesha M., Roy D., Dor F.J. Inactivated mesenchymal stem cells maintain immunomodulatory capacity. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25:1342–1354. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galiano R.D., Michaels J., 5th, Dobryansky M., Levine J.P., Gurtner G.C. Quantitative and reproducible murine model of excisional wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray P.J., Allen J.E., Biswas S.K., Fisher E.A., Gilroy D.W., Goerdt S., Gordon S., Hamilton J.A., Ivashkiv L.B., Lawrence T. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cal S., Quesada V., Llamazares M., Díaz-Perales A., Garabaya C., López-Otín C. Human polyserase-2, a novel enzyme with three tandem serine protease domains in a single polypeptide chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1953–1961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang M., Kurkinen M. Cloning and characterization of a novel matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), CMMP, from chicken embryo fibroblasts. CMMP, Xenopus XMMP, and human MMP19 have a conserved unique cysteine in the catalytic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17893–17900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basu A., Munir S., Mulaw M.A., Singh K., Crisan D., Sindrilaru A., Treiber N., Wlaschek M., Huber-Lang M., Gebhard F., Scharffetter-Kochanek K. A novel S100A8/A9 induced fingerprint of mesenchymal stem cells associated with enhanced wound healing. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6205. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24425-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee E.Y., Lee Z.H., Song Y.W. CXCL10 and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2009;8:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J., Zhang L., Yu C., Yang X.F., Wang H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark. Res. 2014;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2050-7771-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugholm L.H., Bæk R., Søndergaard E.K., Revenfeld A.L., Jørgensen M.M., Varming K. Phenotyping of leukocytes and leukocyte-derived extracellular vesicles. J. Immunol. Res. 2016;2016:6391264. doi: 10.1155/2016/6391264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tohami T., Drucker L., Radnay J., Shapira H., Lishner M. Expression of tetraspanins in peripheral blood leukocytes: a comparison between normal and infectious conditions. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:235–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen P., Cescon M., Zuccolotto G., Nobbio L., Colombelli C., Filaferro M., Vitale G., Feltri M.L., Bonaldo P. Collagen VI regulates peripheral nerve regeneration by modulating macrophage recruitment and polarization. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:97–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qadri M., Jay G.D., Zhang L.X., Wong W., Reginato A.M., Sun C., Schmidt T.A., Elsaid K.A. Recombinant human proteoglycan-4 reduces phagocytosis of urate crystals and downstream nuclear factor kappa B and inflammasome activation and production of cytokines and chemokines in human and murine macrophages. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018;20:192. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1693-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Sharif A., Jamal M., Zhang L.X., Larson K., Schmidt T.A., Jay G.D., Elsaid K.A. Lubricin/proteoglycan 4 binding to CD44 receptor: a mechanism of the suppression of proinflammatory cytokine-induced synoviocyte proliferation by lubricin. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1503–1513. doi: 10.1002/art.39087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alquraini A., Garguilo S., D’Souza G., Zhang L.X., Schmidt T.A., Jay G.D., Elsaid K.A. The interaction of lubricin/proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) with Toll-like receptors 2 and 4: an anti-inflammatory role of PRG4 in synovial fluid. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015;17:353. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0877-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong D., Shi W., Yi S.J., Chen H., Groffen J., Heisterkamp N. TGFβ signaling plays a critical role in promoting alternative macrophage activation. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song H., Cha M.J., Song B.W., Kim I.K., Chang W., Lim S., Choi E.J., Ham O., Lee S.Y., Chung N. Reactive oxygen species inhibit adhesion of mesenchymal stem cells implanted into ischemic myocardium via interference of focal adhesion complex. Stem Cells. 2010;28:555–563. doi: 10.1002/stem.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J., Wang D., Liu D., Fan Z., Zhang H., Liu O., Ding G., Gao R., Zhang C., Ding Y. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell treatment alleviates experimental and clinical Sjögren syndrome. Blood. 2012;120:3142–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corradetti B., Taraballi F., Martinez J.O., Minardi S., Basu N., Bauza G., Evangelopoulos M., Powell S., Corbo C., Tasciotti E. Hyaluronic acid coatings as a simple and efficient approach to improve MSC homing toward the site of inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08687-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou K.J., Lee P.T., Chen C.L., Hsu C.Y., Huang W.C., Huang C.W., Fang H.C. CD44 fucosylation on mesenchymal stem cell enhances homing and macrophage polarization in ischemic kidney injury. Exp. Cell Res. 2017;350:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraitchman D.L., Tatsumi M., Gilson W.D., Ishimori T., Kedziorek D., Walczak P., Segars W.P., Chen H.H., Fritzges D., Izbudak I. Dynamic imaging of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells trafficking to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:1451–1461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Witte S.F.H., Luk F., Sierra Parraga J.M., Gargesha M., Merino A., Korevaar S.S., Shankar A.S., O’Flynn L., Elliman S.J., Roy D. Immunomodulation by therapeutic mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) is triggered through phagocytosis of MSC by monocytic cells. Stem Cells. 2018;36:602–615. doi: 10.1002/stem.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon S., Plüddemann A., Martinez Estrada F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol. Rev. 2014;262:36–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimball A., Schaller M., Joshi A., Davis F.M., denDekker A., Boniakowski A., Bermick J., Obi A., Moore B., Henke P.K. Ly6CHi blood monocyte/macrophage drive chronic inflammation and impair wound healing in diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:1102–1114. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.310703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lettmann S., Bloch W., Maaß T., Niehoff A., Schulz J.N., Eckes B., Eming S.A., Bonaldo P., Paulsson M., Wagener R. Col6a1 null mice as a model to study skin phenotypes in patients with collagen VI related myopathies: expression of classical and novel collagen VI variants during wound healing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen P., Cescon M., Bonaldo P. Lack of collagen VI promotes wound-induced hair growth. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015;135:2358–2367. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu L., Dawson L.A., Yan M., Zimmel K., Lin Y.L., Dolan C.P., Han M., Muneoka K. BMP9 stimulates joint regeneration at digit amputation wounds in mice. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:424. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08278-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edsfeldt S., Holm B., Mahlapuu M., Reno C., Hart D.A., Wiig M. PXL01 in sodium hyaluronate results in increased PRG4 expression: a potential mechanism for anti-adhesion. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2017;122:28–34. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2016.1230157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le M., Naridze R., Morrison J., Biggs L.C., Rhea L., Schutte B.C., Kaartinen V., Dunnwald M. Transforming growth factor beta 3 is required for excisional wound repair in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li M., Qiu L., Hu W., Deng X., Xu H., Cao Y., Xiao Z., Peng L., Johnson S., Alexey L. Genetically-modified bone mesenchymal stem cells with TGF-β3 improve wound healing and reduce scar tissue formation in a rabbit model. Exp. Cell Res. 2018;367:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shigemoto-Kuroda T., Oh J.Y., Kim D.K., Jeong H.J., Park S.Y., Lee H.J., Park J.W., Kim T.W., An S.Y., Prockop D.J., Lee R.H. MSC-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate immune responses in two autoimmune murine models: type 1 diabetes and uveoretinitis. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:1214–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lim M., Wang W., Liang L., Han Z.B., Li Z., Geng J., Zhao M., Jia H., Feng J., Wei Z. Intravenous injection of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells reduces the infarct area and ameliorates cardiac function in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9:129. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0888-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen J.S., Longaker M.T., Gurtner G.C. Murine models of human wound healing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1037:265–274. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niiyama H., Huang N.F., Rollins M.D., Cooke J.P. Murine model of hindlimb ischemia. J. Vis. Exp. 2009;(23):1035. doi: 10.3791/1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Picelli S., Faridani O.R., Björklund A.K., Winberg G., Sagasser S., Sandberg R. Full-length RNA-seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mora-Castilla S., To C., Vaezeslami S., Morey R., Srinivasan S., Dumdie J.N., Cook-Andersen H., Jenkins J., Laurent L.C. Miniaturization technologies for efficient single-cell library preparation for next-generation sequencing. J. Lab. Autom. 2016;21:557–567. doi: 10.1177/2211068216630741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E., Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maus U., Herold S., Muth H., Maus R., Ermert L., Ermert M., Weissmann N., Rosseau S., Seeger W., Grimminger F., Lohmeyer J. Monocytes recruited into the alveolar air space of mice show a monocytic phenotype but upregulate CD14. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001;280:L58–L68. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.