Abstract

Aging happens to everyone everywhere. At present, however, little is known about whether lifespan adult development—and particularly development in late adulthood—is pan-cultural or culture-bound. Here, we propose that in Western cultural contexts, individuals are encouraged to maintain the active, positive, and independent self. This cultural expectation continues even in late adulthood, thus leading to a mismatch between aspirations to live up to the cultural expectation and the reality of aging. This mismatch is potentially alienating. In contrast, in Asian cultural contexts, a critical task throughout life is to achieve attunement with age-graded social roles. This ideal may be more attainable even in late adulthood. Our review of existent evidence lends support to this analysis. Specifically, in late adulthood, Americans showed a robust psychological bias toward high-arousal positive (vs. negative) emotions. This positivity, however, concealed a somber aspect of aging that manifested itself in more demanding realms of life. Thus, Americans in late adulthood also showed marked declines in certain desirable personality traits (e.g., extraversion and conscientiousness) and some aspects of the meaning in life (e.g., personal growth and purpose in life). None of these effects was apparent among East Asians. The current work underscores a need to extend research on lifespan development beyond Western populations.

Keywords: Adult development, culture, aging, meaning in life

Introduction

Around 1970, Bob Dylan composed a song called, “Forever Young.” He did so as a lullaby for one of his sons. In this beautiful tune, Dylan prays for his son’s happiness, success, and, most importantly, for him to stay forever young. In writing this song, Dylan also underscores a central tenet of American culture. America is a country for those who are independent, active, and positive. These features would require youthful energy and enthusiasm – thus, a cultural imperative of staying “forever young.”

Ever since Dylan sang this song, the demographics of the U.S. have changed. Every newborn is now expected to live up to 80 years of age. With the rapidly declining birthrate, the median age for Americans, which was 30.2 in 1955, has steadily gone up, reaching 37.5 in 2015. The average American is no longer “young,” and the number of older adults is expected to double in the next 30 years (United Nations, 2017). How will Americans handle the cultural imperative and expectation of staying positively enthusiastic and energetic, or metaphorically, “forever young,” when they are not in fact young anymore? Might this task be unattainable for many of them, which could lead to some degree of alienation and disengagement?

Other countries are graying even more quickly. For example, the median age of Japan was 23.6 and 46.7 in 1955 and 2015, respectively (United Nations, 2017). By looking into the lifespan trajectory of wellbeing and health in such countries, aging Americans might be able to learn some lessons as they age themselves. Aside from such practical benefits, the effort of examining health and wellbeing in other countries will inform theories of psychology more broadly. The field must start examining aging and lifespan development with a broader lens.

The current paper builds on an early analysis of culture and cognitive aging (Kitayama, 2000), and proposes that the American ideal of preserving youth can extend to late adulthood, which gives rise to an important mismatch between personal aspirations to stay enthusiastic, energetic, or “youthful” and the reality of aging. We submit that this mismatch might engender certain difficulties to stay engaged in society and culture. In contrast, in East Asian cultures, there is a strong emphasis on adjustment to age-graded roles and tasks, which might protect Asian older adults against the difficulties faced by their European American counterparts.

Culture and Psychological Processes

Independent Model of the Self

Our analysis is based on a view that culture’s meanings and practices are organized by the norms and values that constitute cross-culturally divergent models of the self. In Western societies today in general, but in North American middle-class culture in particular, there is a strong value placed on the independence of the self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). The self is seen as separated from other such selves. In this model, social relations are typically seen as personally chosen and, thus, as derived from the independence of the self and the personal autonomy it entails. Thus, dominant moral frameworks place a strong emphasis on each individual’s rights, which are often seen as “God-given.” Correspondingly, social duties and obligations are seen as a matter of individual choice.

This moral landscape that surrounds the independent self is reinforced by a number of life tasks made available in Western societies today (Kitayama, Park, Sevincer, Karasawa, & Uskul, 2009). Independent cultures provide various goal states, such as uniqueness, control, influence, and self-reliance. In each case, there exists a clearly defined set of behaviors that are needed to accomplish such goals. For example, to influence others requires a strong sense of agency, paired with enthusiasm about the value of one’s opinions and judgments (Tsai et al., 2007). These tasks require the very qualities—agency, enthusiasm, and positivity—that metaphorically define “youthfulness.”

Interdependent Model of the Self

In non-Western societies today in general, but in East Asian culture in particular, there is a contrasting view of the self as interdependent with others in significant social units (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). The self is conceptualized as inherently connected with the others. In this model, social relations are the primary context in which the self is defined. Thus, for example, interests, goals, and attitudes that are based only on personal considerations are seen as secondary at best. The focus on these efforts may be perceived as immature and, thus, childish. Instead, the self is defined by social roles and the duties and obligations defined therein.

The model of the self as interdependent is reinforced by a number of life tasks available in Eastern societies today (Kitayama et al., 2009). Culture provides various goal states such as similarity with others, fitting-in, adjustment, mutual reliance, and sympathy. These tasks require an agent (or the self) that actively adjusts to significant others while exercising due moderation on emotions and motivations. This orientation results, for example, in a broad cognitive scope and the value placed on low-arousal emotions. Moreover, within this view, life stages are defined by social roles, which are typically age-graded (Arnett, 2016; Kitayama, 2000). Throughout, the self is expected to adjust peacefully, and perhaps calmly, to fulfill the roles prototypical of each life stage.

Cultural Variation in Psychological Processes

Evidence is growing that the divergent cultural systems discussed above are reflected in the habitual mode of psychological operation (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). For example, independent people (e.g., European Americans) are more focused on personal goals and thus “know” what and where to look at, resulting in focused attention. In contrast, interdependent people (e.g., East Asians) are more attuned to social expectations and norms, leading to holistic attention (Nisbett et al., 2001). Further, sources of happiness vary accordingly. Happiness is unequivocally positive and personal for Americans. Japanese, however, recognize, more clearly, the significance of social relations for happiness (Kitayama et al., 2009). Most importantly, the motivations of influencing and adjusting (Morling et al., 2002), called primary and secondary control, respectively (Heckhausen et al., 2010), are present in all cultures. However, cultures vary in the relative weight given to one or the other (Weisz et al., 1984). East Asians are more accommodating to social expectations and norms, whereas European Americans may be more insistent on their personal goals and values.

Lifespan Development in Japan and the U.S.

At the outset, it should be made clear that aging is often painful and typically seen very negatively in all known societies (North & Fiske, 2015). Indeed, a subtle reminder of aging can cause stereotype threat among European American and Asian older adults alike (Barber et al., 2019; Tan & Barber, 2018). Nevertheless, negative stereotypes of older adults could motivate people to offer help and other positive responses to them (Luong et al., 2011). Moreover, especially in Asian societies, older adults may be protected from the negative stereotypes of aging in another way. Society may have relatively more benign views of aging (Ackerman & Chopik, under review; Löckenhoff et al., 2009) in part because of traditional views of aging in, for example, Confucianism and Buddhism, which promote active adjustment of expectations and aspirations in age-graded fashion (Bedford & Yeh, 2019). Thus, the vigor and enthusiasm emphasized during early adulthood, may no longer be positively sanctioned during late adulthood. Such age-graded views of developmental stages are still dominant in East Asian cultures (Tan & Barber, 2018).

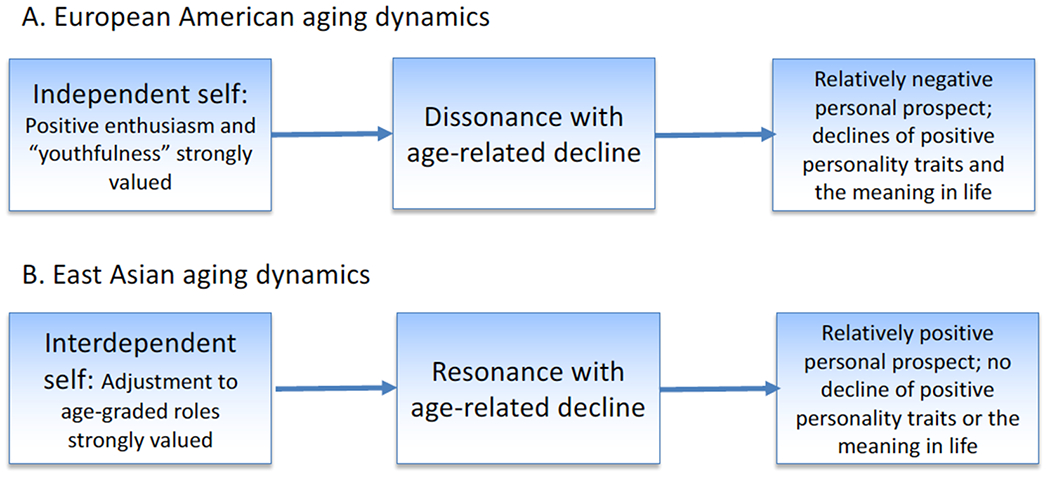

With this backdrop, we can now articulate our hypothesis. In European American contexts (Figure 1-A), there is a strong emphasis on independent self. The notion of independence in these contexts has been historically elaborated to promote personal initiatives, an effort to influence others as well as the surrounding situations, and positive, enthusiastic, future-oriented pursuit of one’s own goals and personal agenda. All of these tasks would require positivity, energy, and other high-arousal psychological states (Tsai et al., 2007). Moreover, the American mainstream culture has never articulated age-graded social roles and tasks for older adults in ways other cultural traditions such as Buddhism and Confucianism have (Arnett, 2016; Kitayama, 2000). Hence, the emphasis on positive energy and vigor may extend over to late adulthood.1 We argue that there will arise substantial discordance or dissonance between the aspiration to be independent in culturally prescribed (i.e., vigorous and energetic) fashion and the inevitable age-related decline. Accordingly, the U.S. cultural imperative of staying positively enthusiastic or vigorous may present a great challenge for many older adults. Moreover, the cultural practices are tailored to require such vigor and energy, and as a consequence, it may also become challenging to sustain new prospects in life in culturally prescribed terms during late adulthood. Due to this challenge, it may also be hard to maintain some desirable styles of personally engaging in society, such as conscientiousness and extraversion. All this may lead eventually to passivity, alienation, and disengagement from social life.

Figure 1.

Schematic models of aging in two cultural contexts: A. In European American contexts, there is a strong push toward positivity and enthusiasm, which results in conflicts and frustration over age-related decline, which in turn leads eventually to alienation and disengagement. B. In East Asian contexts, there is a strong push toward adjustment to age-graded roles and tasks, which results in relatively few conflicts with age-related decline, which in turn leads eventually to new meanings and engagement.

While sharing negative stereotypes of older adults, East Asian contexts seem to present a distinctly different outlook for older adults (Figure 1-B). The interdependent view of the self, positively sanctioned in these contexts, has historically been elaborated in family-based terms (Bedford & Yeh, 2019). In particular, there is an emphasis on filial piety that involves deference toward older adults in their families or communities. On their part, older adults may be motivated to actively adjust to age-graded social roles that are offered by culture, for example, by the Confucian model that specifies different ideal states for different stages of life (Arnett, 2016; Bedford & Yeh, 2019; Kitayama, 2000). There will result a greater resonance between age-graded social roles and the inevitable mental and physical decline. Hence, East Asian older adults may be better able to adjust what they want to think and feel to the societal expectations and norms of aging. Their thought, desire, and action may be more closely attuned to the socially prescribed aging roles. It may therefore be more realistic to craft some new goals, pleasures, and most of all, meanings in life during older adulthood in East Asian societies than in European American societies.

To examine this broad possibility, we will address five topics, (i) emotional norms, (ii) positivity in emotional experience, (iii) personal prospects of aging, (iv) personality traits, and (v) meaning in life.

Norms/Desire for Highly Arousing Positive Emotions

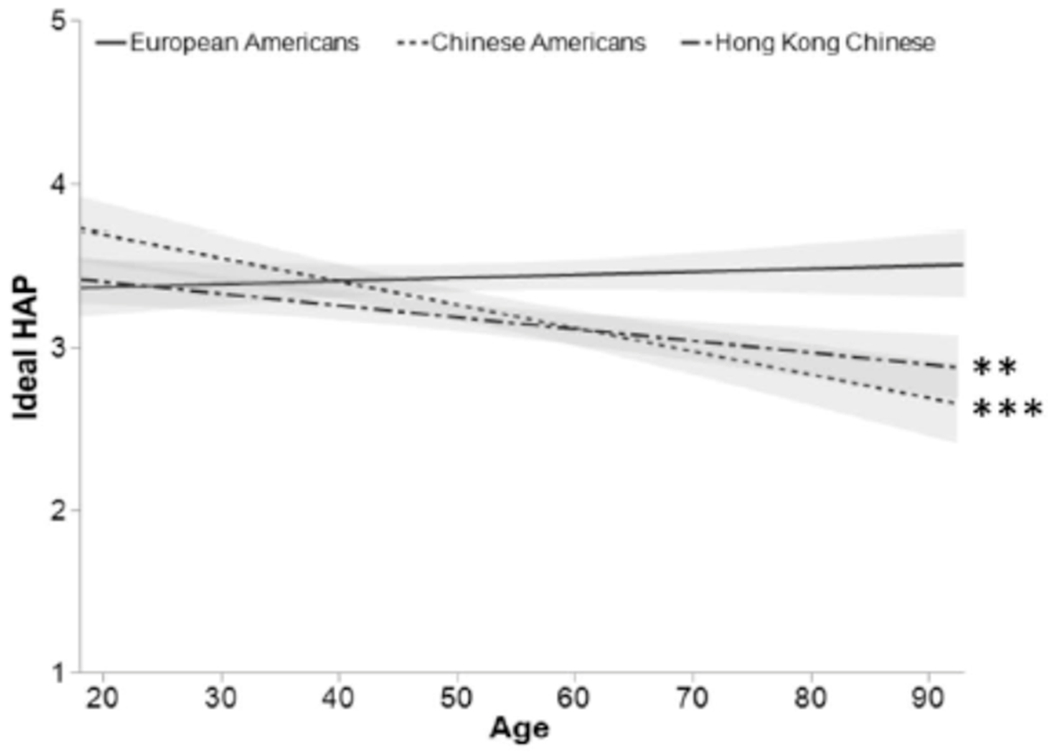

One central premise of our theoretical model (Figure 1) is that the social norms and personal desire for highly arousing positive emotions such as enthusiasm and excitement may remain quite strong even in late adulthood among European Americans. This age-related trajectory is unlikely in cultures where adjustment to age-related tasks and roles is strongly valued.

In recent work, Tsai and colleagues (2018) examined the degree to which people want to feel high- (vs. low-) arousal positive emotions, such as excitement, enthusiasm, and joy. They thus tested the subjective norms and desires for these emotions. Importantly, they tested adults of a wide age range. As illustrated in Figure 2, for European Americans, the norms/desire for high-arousal positive emotions are quite strong throughout the life course, including late adulthood. In contrast, both Chinese Americans and Chinese in Hong Kong showed an age-graded adjustment. That is, the norms for high-arousal positive emotions were quite strong at relatively young adulthood (up to approximately 40 years old), but toward late adulthood, it declined precipitously.

Figure 2.

Norms/desire for highly arousing positive emotions (e.g., enthusiasm, excitement, joy) over life course for European Americans, Chinese Americans, and Hong Kong Chinese. Adopted from Tsai et al. (2018), Psychology and Aging.

Positivity Bias in Emotional Experience

The Tsai et al. evidence suggests that the norms/desire for intense emotional positivity remain strong in late adulthood among European Americans. Among East Asians, however, the norms/desire for intense positivity decrease in late adulthood. Might this cultural difference be reflected in the actual emotional experience?

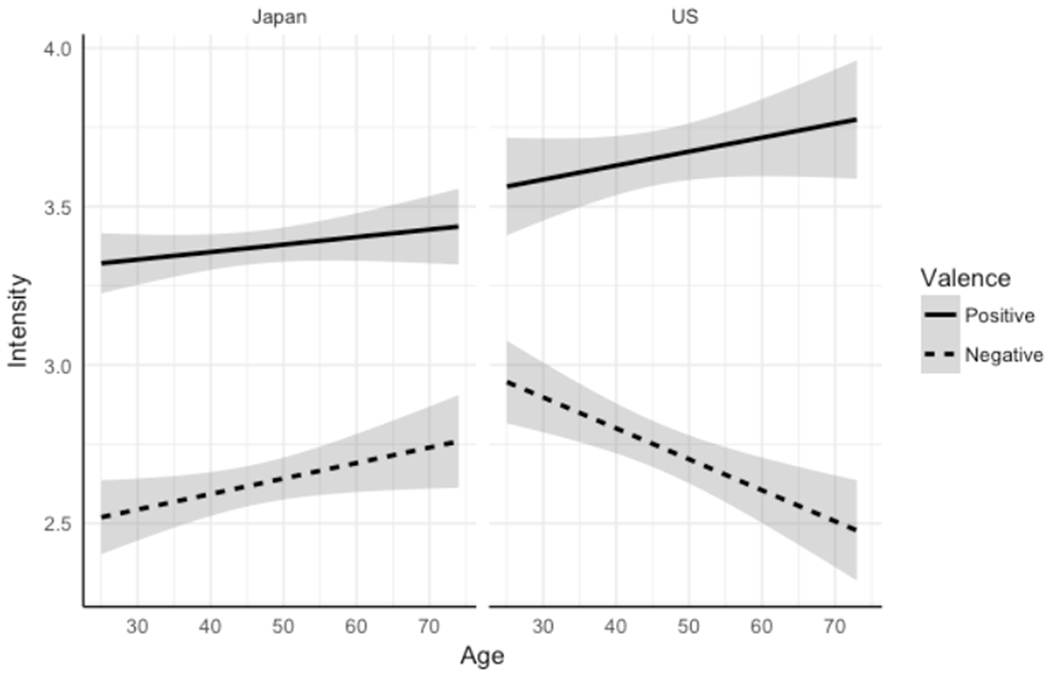

In a recent study, both Americans and Japanese who varied in age reported on how strongly they experienced various emotions in 10 different emotionally ambiguous situations (Grossmann et al., 2014). Figure 3 plots the reported intensity of positive and negative emotions as a function of age. Across cultures, positive emotions are reportedly experienced more strongly than negative emotions. This valence effect could be due to the situations used in the study being relatively more pleasant or positive. Importantly, however, the intensity of positive (in comparison to negative) emotions increased steadily as a function of age among Americans, but no such trend was evident among Japanese. Similar cross-cultural variation in the positivity in late adulthood has been observed with measures of subjective wellbeing (Nakagawa et al., 2018; Pethtel & Chen, 2010). Moreover, using attention to emotional stimuli as the dependent variable, similar cross-cultural variations in the psychological bias toward positive (vs. negative) emotions have been obtained (Fung et al., 2008, 2010).

Figure 3.

Lifespan trajectory in the psychological bias favoring positive (vs. negative) emotional experience. Adopted from Grossmann, Karasawa, Kan, & Kitayama (2014). Emotion, 14, 679-692.

Why might Americans become relatively more positive as a function of age? The personal quest for emotional positivity may exist throughout the life course in American culture. However, as proposed by socioemotional sensitivity theory (Carstensen et al., 1999), this quest for positivity is much constrained by many competing life demands when one works, raises children, or advances in his or her career. By late adulthood, however, these life demands often dissipate, leaving individuals unfettered to maximize their personal wellbeing—in other words, to chase the American norm of positivity and enthusiasm. This active effort to live up to the cultural imperative may contain a contradiction in itself, insofar as both physical vigor and the level of mental energy may decrease for many (if not all) older adults. In contrast, in East Asian cultures, there may be a strong cultural imperative of adjusting to age-related roles. They may therefore find ways to fit-in to such new roles and new places in life. Their emotional positivity may therefore not increase.

Challenges of Being “Enthusiastic” in Late Adulthood

At first glance, the outlook of the American older age would seem quite positive (Hong et al., 2019; Nakagawa et al., 2018; Pethtel & Chen, 2010). This observation is consistent with the socioemotional selectivity theory, which proposes that older adults prioritize the goal of emotional positivity. Thus, older Americans may sometimes actively select social networks to connect so as to maximize the chances of achieving this goal (Luong et al., 2011). At the same time, however, emotional positivity is also relatively easy to attain by reappraising situations in rose-colored terms or merely ignoring inconvenient sides of their experience. Indeed, the Grossmann et al. (2014) study did not involve any active selection of social networks. It merely tapped psychological reactions to emotional scenarios. Hence, the emotional positivity among American older adults may reflect the effort of feeling positive by some psychological means. It therefore may be easily attainable even while the mental and physical vigor becomes more challenging to sustain. Accordingly, we might wonder if the hedonism apparent in late adulthood among European Americans might conceal aging-linked difficulties, which could show up in more demanding tasks of living life in certain styles to remain, say, “extraverted” or “purposeful.”

Imagine someone was extraverted. The person may have frequented parties and enjoyed conversations. The ambient noise did not bother him. In late adulthood, however, he may well find it increasingly difficult to do the same. Doing so requires energy, vigor, and health of the youth, to say nothing about the acuity in hearing. And the problem will not end at the party. It will go on at work as well as at home. Gradually then, many European American older adults may show less positive energy (extraversion). For similar reasons, they may lose a habit of hard work (conscientiousness) or curiosity (openness). Furthermore, this process might also make it hard to sustain some aspects of meaning in life. Imagine another older adult who always tried everything to “personally grow” when she was young. She regularly attended yoga lessons. She jogged. She may also have made it a priority to read numerous books across a variety of genres. She had a “purpose in life.” As she ages, however, it will become increasingly challenging to stick hold to the old regimens. Inevitably, the meaning in life (personal growth or purpose in this case) may suffer.

The difficulty the older adults face in the examples above may result because European American culture neither elaborates nor positively sanctions tasks or norms that are specially tailored for older adults (Arnett, 2016; Kitayama, 2000; Tsai et al., 2018). Hence, many older adults may end up trying to do what they used to be doing at work, at leisure, or in their relationship with friends and family members. They may therefore find it increasingly hard to maintain the behavioral routines they have taken for granted. In this regard, Asian older adults may be different. Asian societies provide people with age-graded tasks and roles (Arnett, 2016; Kitayama, 2000). For example, there may be culturally sanctioned ways of being, say, extraverted or conscientious, in an age-dependent fashion. For example, achievement at work or vigorous exercise may no longer be encouraged or appreciated. These activities, seen as appropriate and praise-worthy while one is relatively young, may no longer be regarded as such in late adulthood. They must be replaced, for example, with the care-taking of grandchildren, much lighter physical therapy sessions, and the like. Asian cultures may delineate such age-adjusted regiments for positive engagement. Likewise, there may be greater culture-level understanding that the ways to grow or to be in charge of work or family matters could differ, depending on life stages. The culture may then provide people with age-appropriate ways for, say, personal growth or being purposeful. Recall many Asians willingly adjust to the age-graded roles. To the extent that they do, they may find new ways of engagement in late adulthood, which may give rise to new reasons to live.

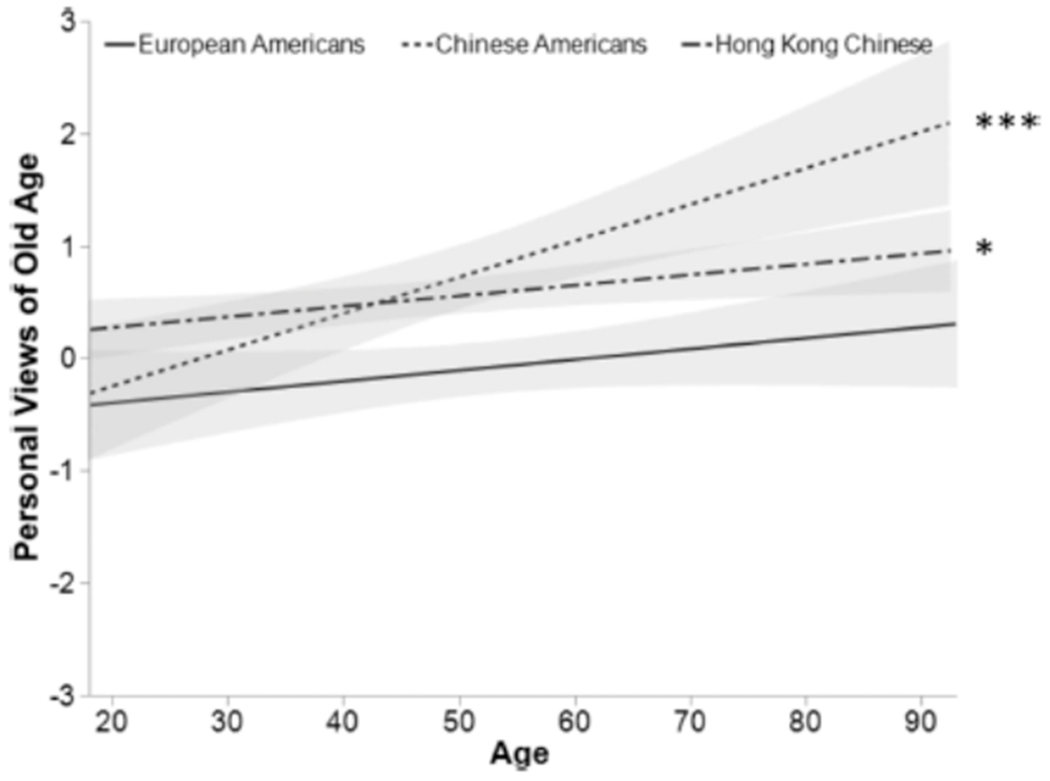

Personal views of aging.

The Tsai et al. (2018) study that tested the norms/desire for high-arousal positive emotions (Figure 2) also probed personal views of old age. The participants were asked to list things they “are looking forward to about being 75 or older,” and those they “are dreading about being 75 or older.” As shown in Figure 4, European Americans show no change across the life span. On average, they were as likely to list positive views as negative views. However, both Chinese Americans and Hong Kong Chinese were different. They were increasingly more likely to list positive (vs. negative) views of aging as they got older. Thus, older Chinese and Chinese Americans seem to cultivate more positive prospects for themselves, but this effect is missing in older Americans.

Figure 4.

Personal views of aging over life course for European Americans, Chinese Americans, and Hong Kong Chinese. Adopted from Tsai et al. (2018), Psychology and Aging.

The authors interpreted this finding by referring to adjustment to age-graded norms for emotion among East Asians. East Asians adjust their expectations as they get older. They thus no longer want to experience excitement, enthusiasm, and the like as much as they used to while they were young. Because of this age-graded adjustment, they tend to find new things to do, new plans to try, and new meanings to create in late adulthood. Conversely, European American older adults tend to endorse the norms of staying enthusiastic, excited, and thus youthful. This commitment to the norms and values of youthful independence will make it difficult to adjust their aspirations and motivations to the reality of physical and mental decline. In support of this analysis, the age-linked increase of positive personal views of aging, more evident among Chinese and Chinese Americans (Figure 4), was mediated by the age-graded adjustment of the norm/desire for highly arousing positive emotions (Figure 2).

Personality traits.

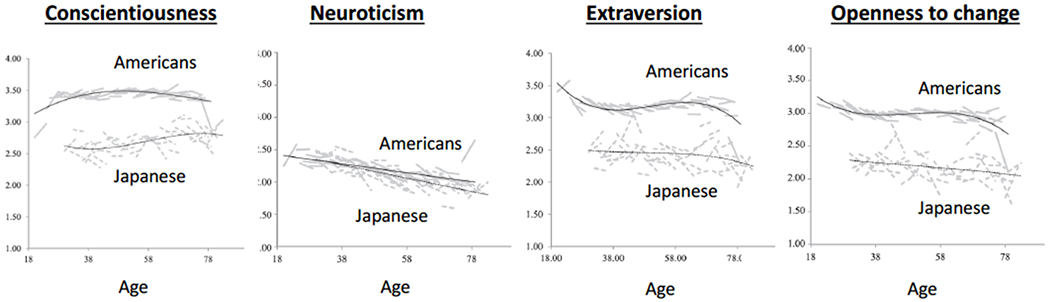

Some traits, such as conscientiousness and openness, carry positive connotations across many (if not all) contexts. Will people find it hard to maintain the level of such positively-valenced personality traits in late adulthood, and if so, will this difficulty be more apparent in European Americans than in East Asians? Chopik and Kitayama (2018) relied on the longitudinal portion of the MIDUS/MIDJA dataset to investigate changes in personality over the lifespan (Chopik & Kitayama, 2018). The Big Five global traits (i.e., agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to change) were assessed twice, with intervals of approximately 5 years in Japan and 10 years in the U.S. The researchers used information about longitudinal changes of each trait for each participant and fitted linear, curvilinear, and/or quadratic functions to the change data to estimate the best-fitting trajectory of lifespan change for the trait. In Figure 5, it is evident that American means are consistently higher than Japanese means regardless of trait or age. It is possible that U.S. culture promotes stronger personalities than Japanese culture, consistent with a view that the ethos of independence fosters more clear-cut, disambiguated self-concepts (Campbell et al., 1996). Another possibility is a response bias toward positivity known to be far stronger in the U.S. than in East Asia (Heine et al., 1999). With this massive cultural difference set aside, it is also clear that the life-course trajectories were remarkably different between the two cultural groups for four of the five traits.

Figure 5.

Lifespan trajectory in three global personality traits: Conscientiousness, neuroticism, and extraversion. Adopted from Chopik & Kitayama (2017). Journal of Personality.

First, conscientiousness showed statistically significant curvilinear trajectories in both cultures. But the exact shape of the function was markedly different, resulting in a significant interaction between the curvilinear term and culture. Japanese showed a drop of conscientiousness in midlife. The trait, however, gradually increased toward late adulthood. In contrast, the curvilinear function of Americans was equally highly significant, but the shape of the function was very different. The level of conscientiousness peaked in middle adulthood, after which it steadily decreased toward late adulthood. Thus, a “decline” of conscientiousness is evident. Second, neuroticism showed a significant linear effect in both cultures, showing a steady decrease over the life course. However, this decrease was significantly less pronounced among Americans than among Japanese. Third, extraversion (a positive trait) showed a strong quadratic function among Americans, with a sharp drop apparent in late adulthood. This pattern was absent among Japanese. Fourth, a similar pattern was evident in openness to change. Americans showed a statistically significant quadratic effect, with a sharp drop in late adulthood. However, Japanese did not show this drop, although, in this case, caution is warranted since the quadratic term x culture interaction did not reach statistical significance.

The findings in Figure 5 are consistent with our theoretical model in Figure 1. The aspiration to stay positive, energetic, and young is very strong in Americans because of cultural expectations of independence and primary control. In fact, American older adults seem to live up to the cultural standard as long as doing so is less demanding and thus easy even in the face of declining vigor and health, as may be the case in the positivity in emotional experience (Figure 3). Moreover, when it is hard to do so, they may well accommodate to the reality of aging to some degree (Heckhausen et al., 2010). However, the cultural pull of primary control is still strong (Weisz et al., 1984). Moreover, American culture does not seem to place an emphasis on age-graded life roles as much as East Asian traditions, such as Confucianism (e.g., “filial piety”) and Buddhism (e.g., “life cycle”), patently do (Arnett, 2016; Bedford & Yeh, 2019; Kitayama, 2000). As a consequence, many Americans may still have strong aspirations to remain enthusiastic, excited, positive, and “young” even in late adulthood. Gradually then, due to insufficient adjustment to the reality of aging, they may lose a habit of hard work (conscientiousness) while showing less positive energy (extraversion) and curiosity (openness). This change may happen even while the older adults show positivity in domains that are less taxing or demanding (e.g., emotional experience, Figure 3). Data from Germany are consistent (Wagner et al., 2016). Japanese, in contrast, supposedly adjust their behaviors and habits of thought to newly prescribed age-graded norms and roles, which could enable them to find new age-proper ways of being conscientious, extraverted, or perhaps curious and open.

Meaning in life.

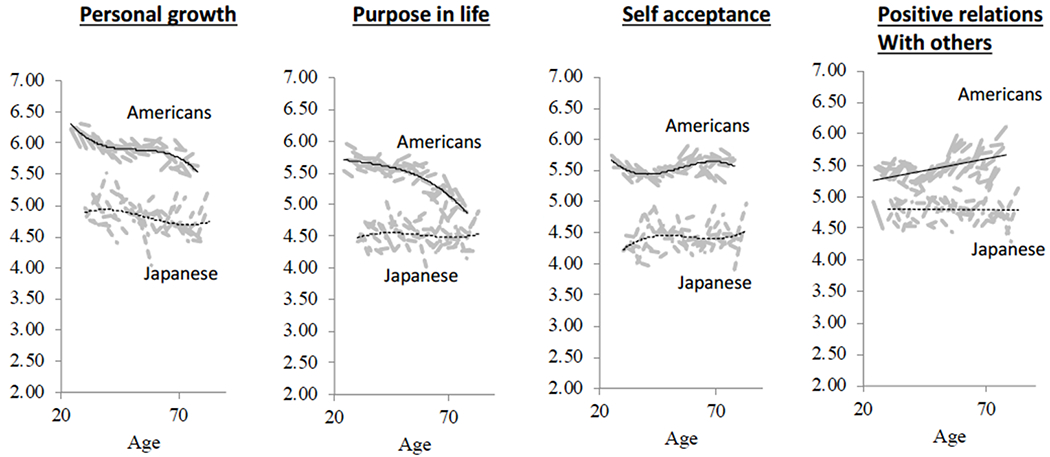

If the imperative of staying vigorous and positively enthusiastic alienates Americans in their old age, it may also result in a loss of the meaning in life. Ryff and colleagues have developed a well-validated scale that assesses several facets of the meaning in life (Ryff & Keyes, 1995).2 These facets include autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. In combination, they are referred to as “psychological wellbeing.” In a recent analysis of the MIDUS/MIDJA longitudinal data (Chopik, Berg, & Kitayama, 2019), we again used the longitudinal change data from each participant and modeled these data to identify the best-fitting age functions for each facet of the meaning in life.3

The results are summarized in Figure 6. As was the case in the analysis of personality, American means were consistently higher than Japanese means. It is possible that U.S. culture is affording more meanings than Japanese culture across the board, although a clear alternative come from a positivity bias Americans (but not East Asians) are known to exhibit (Heine et al., 1999). Of note, above and beyond the cultural variation in positivity, there was a marked decline in personal growth and purpose in life in late adulthood among Americans, consistent with earlier findings (Hill & Weston, 2011). This age-linked decline of the two meaning dimensions was not apparent among Japanese. Further, in self-acceptance, we can note a clear sign of decline toward very late adulthood among Americans. However, Japanese showed increases around the same age range. Last, but not least, there was one trend in late adulthood that appeared more positive among Americans than among Japanese. Positive relations with others increased throughout life among Americans – an effect that was not apparent in Japanese. We suspect that this American effect is caused by an effort to select pleasant people in their social circles (Carstensen et al., 1999). Given high relational mobility of American society (Thomson et al., 2018), this goal may be easily attainable even in late adulthood. Thus, the effect evident in the positive relations might be more analogous to a hedonic effect we saw earlier in our discussion of the age-related increase of emotional positivity among Americans (Figure 3).

Figure 6.

Lifespan trajectory in the meaning of life in three domains: Personal growth, purpose in life, self acceptance, and positive relations with others.

Regardless of the validity of this interpretation, the overall weight of evidence suggests that in late adulthood, Americans hold less positive personal views of aging (Figure 4) and show declines of both positively-valenced personality traits (Figure 5) and some dimensions of meaning in life (Figure 6). In contrast, East Asian older adults appear to develop more positive prospects for their life, maintain the level of desirable personality traits, and to keep engaging meanings in life.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of the current work must be noted. First, we proposed that the cultural ethos of independence is linked to an emphasis on positive, future-oriented vigor and enthusiasm. We also suggested that the ethos of interdependence is tied to contrastingly “calm” adjustment to age-graded roles. These links, however, could be particular instantiations of independence or interdependence (Kitayama et al., 2019; San Martin et al., 2018). They may be contingent on local social ecologies, demographics, and the like (Kitayama & Uskul, 2011). This complex contingency has yet to be fully unpacked. Moreover, other factors, unrelated to independence or interdependence, could also be operative.

Second, the thesis advanced here received support from some measures of positive emotions (Figure 3) and those of personality or meanings (Figures 5 and 6). One major shortcoming comes from the fact that all these measures are based exclusively on self-report. For example, can the emotional positivity, posited for American older adults, be observed in the activity of a reward processing network of the brain? Alternatively, might the putative decline of meaning in life Americans be revealed in, say, defensive responses to threats? Future work must utilize diverse methodologies, including both behavioral and neural measures, to seek further support for our thesis (Kitayama et al., 2018). In the process, the current framework may well have to be modified and refined.

Third, we portrayed a positive side of aging for Asians, which might have inadvertently highlighted somewhat negative sides of aging for Americans. However, the American norm that emphasizes “youthful” energy may sometimes lead to positive outcomes, especially for older adults who are physically and mentally fit. Conversely, the Asian age-graded social norms can prematurely encourage healthy older adults to quit jobs or stop active involvement in social circles and activities. Clearly, successful aging is a multifaceted process (Rowe & Kahn, 1997), and we hope that our review can serve a beginning of the effort to fully explicate the bio-cultural dynamic that plays out over the life course.

In closing, we wish to note that a critical mission of scientific research is to offer well-informed prescriptions for the public good, including healthy aging. This mission may also be well served by a self-conscious effort to learn from other cultures and the wisdom they have accumulated over generations. For example, we may learn from Asian older adults that active adjustment to age-graded roles and tasks is not an act of despair or passivity. On the contrary, this may be a way to be both respected and accepted by their community at large. It may enable one to cultivate new age-adjusted ways of contributing to the community and eventually to society at large. This view was traditionally upheld in many Asian societies (as revealed, for example, in Confucianism and Buddhism). It is age-old. And this culturally cultivated idea of aging may have to be reevaluated and perhaps reappreciated in both Asia and the West alike. It can even be a basis for intervention programs to encourage older adults to actively engage in society, thereby to foster new selves, and weave new personal narratives, aspirations, and the meaning in the last decade of their lives.

The public significance.

Wellbeing in the last decade of life is increasingly important as the aging population grows. Our work illuminates the critical role of culture in affording opportunities for healthy aging.

Footnotes

Given this, the positive energy may be linked to “youth,” and it might be of interest to ask the question of whether the link between the positive energy and youth is culturally acknowledged or elaborated. For the current purposes, however, this question is beside the point. We argue that in U.S. culture, culture’s resources (e.g., beliefs and practices) are set up in such a way that they require positive energy and enthusiasm. This feature of the cultural resources poses challenges to those who are not fully capable of maintaining this psychological state, as is likely to be true for many (if not all) older adults.

The meaning in life is sometimes equated with purpose in life (Frankl et al., 2006). Here, however, we follow Charles Taylor, the Canadian philosopher (Taylor, 1989), and take a broader view that the meaning in life can result from the symbolic means of orienting the self in the world. Purpose is one of such means. But there may be others, including some of the dimensions of eudaimonic wellbeing proposed by Ryff and Keyes (1995).

There is an earlier analysis that focused exclusively on cross-sectional data from the first survey alone (Karasawa et al., 2011). The current analysis explicitly takes longitudinal change information into account and thus is likely to reveal the age trajectory more accurately.

References

- Ackerman L, & Chopik WJ (under review) Cross-cultural comparisons in implicit and explicit bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2016). Life stage concepts across history and cultures: Proposal for a new field on indigenous life stages. Human Development, 59(5), 290–316. 10.1159/000453627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman L, & Chopik WJ (invited resubmission) Cross-cultural comparisons in implicit and explicit bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Seliger J, Yeh N, & Tan SC (2019). Stereotype threat reduces the positivity of older adults’ recall. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(4), 585–594. 10.1093/geronb/gby026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford O, & Yeh K-H (2019). The History and the Future of the Psychology of Filial Piety: Chinese Norms to Contextualized Personality Construct. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 100 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, & Lehman DR (1996). “Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries”: Correction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1114–1114. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, & Charles ST (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopik WJ, Berg M, & Kitayama S (2019). The meaning in life across lifespan: A US and Japan comparison.

- Chopik WJ, & Kitayama S (2018). Personality change across the life span: Insights from a cross-cultural, longitudinal study. Journal of Personality, 86(3), 508–521. 10.1111/jopy.12332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE, Kushner HS, & Winslade WJ (2006). Man’s Search for Meaning (1 edition). Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Isaacowitz DM, Lu AY, & Li T (2010). Interdependent self-construal moderates the age-related negativity reduction effect in memory and visual attention. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 321–329. 10.1037/a0019079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Lu AY, Goren D, Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, & Wilson HR (2008). Age-related positivity enhancement is not universal: Older Chinese look away from positive stimuli. Psychology and Aging, 23(2), 440–446. 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, Karasawa M, Kan C, & Kitayama S (2014). A cultural perspective on emotional experiences across the life span. Emotion, 14(4), 679–692. 10.1037/a0036041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, & Schulz R (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117(1), 32 10.1037/a0017668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106(4), 766–794. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Charles ST, Lee S, & Lachman ME (2019). Perceived changes in life satisfaction from the past, present and to the future: A comparison of U.S. and Japan. Psychology and Aging, 34(3), 317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasawa M, Curhan KB, Markus HR, Kitayama SS, Love GD, Radler BT, & Ryff CD (2011). Cultural Perspectives on Aging and Well-Being: A Comparison of Japan and the United States. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 73(1), 73–98. 10.2190/AG.73.1.d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S (2000). Cultural variations in cognition: Implications for aging research In Stern PC & Carstensen LL (Eds.), The aging mind: Opportunities in cognitive research (pp. 218–237). National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park H, Sevincer AT, Karasawa M, & Uskul AK (2009). A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(2), 236–255. 10.1037/a0015999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, San Martin A, & Savani K (2019). Varieties of interdependence and the emergence of the modern West: Toward the globalizing of psychology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kitayama S, & Uskul AK (2011). Culture, mind, and the brain: Current evidence and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 419–449. 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Varnum MWE, & Salvador CE (2018). Cultural neuroscience In Cohen D & Kitayama S (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (Second Edition, pp. 79–118). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE et al. (2009). Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture-level associates. Psychology and Aging, 24(4), 941–954. 10.1037/a0016901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong G, Charles ST, & Fingerman KL (2011). Better with age: Social relationships across adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(1), 9–23. 10.1177/0265407510391362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Morling B, Kitayama S, & Miyamoto Y (2002). Cultural Practices Emphasize Influence in the United States and Adjustment in Japan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 311–323. 10.1177/0146167202286003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Cho J, Gondo Y, Martin P, Johnson MA, Poon LW, & Hirose N (2018). Subjective well-being in centenarians: A comparison of Japan and the United States. Aging & Mental Health, 22(10), 1313–1320. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1348477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, & Norenzayan A (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310. 10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North MS, & Fiske ST (2015). Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 993–1021. 10.1037/a0039469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethtel O, & Chen Y (2010). Cross-cultural aging in cognitive and affective components of subjective well-being. Psychology and Aging, 25(3), 725–729. 10.1037/a0018511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Keyes CLM (1995). The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin A, Sinaceur M, Madi A, Tompson S, Maddux WW, & Kitayama S (2018). Self-assertive interdependence in Arab culture. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(11), 830–837. 10.1038/s41562-018-0435-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SC, & Barber SJ (2018). Confucian Values as a Buffer Against Age-Based Stereotype Threat for Chinese Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 10.1093/geronb/gby049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson R et al. (2018). Relational mobility predicts social behaviors in 39 countries and is tied to historical farming and threat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(29), 7521–7526. 10.1073/pnas.1713191115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Miao FF, Seppala E, Fung HH, & Yeung DY (2007). Influence and adjustment goals: Sources of cultural differences in ideal affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1102–1117. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Sims T, Qu Y, Thomas E, Jiang D, & Fung HH (2018). Valuing excitement makes people look forward to old age less and dread it more. Psychology and Aging, 33(7), 975–992. 10.1037/pag0000295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Volume II: Demographic Profiles. ST/ESA/SER.A/400.

- Wagner J, Ram N, Smith J, & Gerstorf D (2016). Personality trait development at the end of life: Antecedents and correlates of mean-level trajectories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 411–429. 10.1037/pspp0000071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Rothbaum FM, & Blackburn TC (1984). Standing Out and Standing In. American Psychologist, 15. [Google Scholar]