Abstract

Phosphorylation of the 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E by MAPK-interacting kinases (MNK1/2) is important for nociceptor sensitization and the development of chronic pain. IL-6-induced dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptor excitability is attenuated in mice lacking eIF4E phosphorylation, in MNK1/2−/− mice, and by the nonselective MNK1/2 inhibitor cercosporamide. Here, we sought to better understand the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying how IL-6 causes nociceptor excitability via MNK-eIF4E signaling using the highly selective MNK inhibitor eFT508. DRG neurons were cultured from male and female ICR mice, 4–7 wk old. DRG cultures were treated with vehicle, IL-6, eFT508 (pretreat) followed by IL-6, or eFT508 alone. Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were done on small-diameter neurons (20–30 pF) to measure membrane excitability in response to ramp depolarization. IL-6 treatment (1 h) resulted in increased action potential firing compared with vehicle at all ramp intensities, an effect that was blocked by pretreatment with eFT508. Basic membrane properties, including resting membrane potential, input resistance, and rheobase, were similar across groups. Latency to the first action potential in the ramp protocol was lower in the IL-6 group and rescued by eFT508 pretreatment. We also found that the amplitudes of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) were increased in the DRG following IL-6 treatment, but not in the eFT508 cotreatment group. Our findings are consistent with a model wherein MNK-eIF4E signaling controls the translation of signaling factors that regulate T-type VGCCs in response to IL-6 treatment. Inhibition of MNK with eFT508 disrupts these events, thereby preventing nociceptor hyperexcitability.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY In this study, we show that the MNK inhibitor and anti-tumor agent eFT508 (tomivosertib) is effective in attenuating IL-6 induced sensitization of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptors. Pretreatment with eFT508 in DRG cultures from mice helps mitigate the development of hyperexcitability in response to IL-6. Furthermore, our data reveal that the upregulation of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels following IL-6 application can be blocked by eFT508, implicating the MNK-eIF4E signaling pathway in membrane trafficking of ion channels.

Keywords: Cav3.2, DRG excitability, eFT508, interleukin-6, MNK

INTRODUCTION

Translational regulation of gene expression is an important step involved in neuronal plasticity, and plays a critical role in mechanisms of pathological pain (Khoutorsky and Price 2018; Sonenberg and Hinnebusch 2009; Uttam et al. 2018). The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) belongs to a family of intracellular signaling molecules, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), that are known to promote nociceptor hyperexcitability (Ji et al. 1999). MAPKs stimulate phosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E at serine 209 through MAPK interacting kinases (MNK1/2), and changes in ERK activity modulate translation through MNK signaling (Waskiewicz et al. 1999). The cytokine and inflammatory mediator interleukin-6 (IL-6) controls nociceptive plasticity via translation-dependent mechanisms and initiates signaling cascades that converge on the eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4F complex to increase protein synthesis in sensory neurons (Melemedjian et al. 2010). A critical step in this signaling cascade is MNK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF4E, which is necessary for IL-6-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and nociceptor hyperexcitability (Black et al. 2018; Megat et al. 2019; Moy et al. 2017). A current gap in knowledge is how MNK-eIF4E signaling regulates the excitability of nociceptors when they are exposed to IL-6.

IL-6 has pleiotropic effects on the nervous system including neuroprotection, nerve regeneration, and enhancement of nociception (De Jongh et al. 2003). Elevated levels of IL-6 mRNA are seen in axotomized sensory neurons and in the spinal cord following spinal nerve injury (Arruda et al. 1998; Murphy et al. 1995), and its role has been well studied in behavioral responses in inflammation, nerve injury, and burn injury and in migraine models (De Leo et al. 1996; Summer et al. 2008; Xu et al. 1997; Yan et al. 2012). We have demonstrated that eIF4E phosphorylation is a central regulator of nociceptive plasticity (Black et al. 2018; Megat et al. 2019; Moy et al. 2017). DRG nociceptors from mice lacking the phosphorylation site for MNK1/2 on eIF4E (eIF4ES209A) do not show sensitization to IL-6, and this effect is recapitulated by a MNK1/2 inhibitor, cercosporamide (Black et al. 2018; Moy et al. 2017). However, cercosporamide has effects on other kinases in addition to MNK (Diab et al. 2014; Konicek et al. 2011). On the other hand, eFT508 (Reich et al. 2018) is a potent and selective MNK1/2 inhibitor that reverses both paclitaxel-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and spontaneous activity of DRG nociceptors (Megat et al. 2019). We have also recently demonstrated the efficacy of eFT508 in preventing peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain and its efficacy in preventing IL-6 induced spontaneous firing in cultured DRG neurons (Shiers et al. 2020). Furthermore, inhibitors of phosphorylation are currently in clinical testing phase for their antitumor activity, and therefore investigations into the mechanisms of MNK inhibition in the context of nociception take on added significance (Reich et al. 2018; Teneggi et al. 2020). Herein, we sought to better understand the mechanisms through which eFT508 inhibits the excitability of DRG nociceptors.

Among the many factors controlling the excitability of DRG neurons, T-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) play a crucial role. These channels are low voltage activated and encoded by the Cav3 family of genes: Cav3.1, Cav3.2, and Cav3.3 (Perez-Reyes 2003). T-type currents help control the threshold to initiate action potentials (Nelson et al. 2005), are expressed in small-diameter DRG nociceptors (Rose et al. 2013), and are involved in mediating inflammatory and neuropathic pain behaviors (Chen et al. 2018; Choe et al. 2011; Dogrul et al. 2003). Furthermore, T-type channel blockers are effective in reversing the behavioral manifestations of neuropathic pain including excess spike discharges in DRG neurons (Dogrul et al. 2003; Matthews and Dickenson 2001). Inflammatory mediators including IL-6 are known to promote trafficking of T-type VGCCs to the membrane resulting in the upregulation of these channels (Buckley et al. 2014; Dey et al. 2011; Stemkowski et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019). Therefore, it would be pertinent to investigate the potential role of MNK-eIF4E signaling in linking T-type channels to IL-6-mediated hyperexcitability in DRG neurons. In this study, using the whole cell patch-clamp technique on DRG neurons cultured from mice, we provide evidence to support the conclusion that IL-6 causes MNK-eIF4E-mediated translation of factors that regulate T-type channels, resulting in increased excitability of nociceptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Experiments were performed using male and female Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) CD-1 mice of age 4–7 wk, bred at the University of Texas at Dallas and maintained in a climate-controlled room on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at The University of Texas at Dallas and were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Cell culture.

Cell cultures for patch-clamp electrophysiology were prepared as previously described (Moy et al. 2017). Animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation. DRGs were dissected, placed in ice-cold Hanks’ balanced-salt solution (divalent free), and incubated at 37°C for 15 min in 20 U/mL papain (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) followed by 15 min in 3 mg/mL collagenase type II (Worthington). After trituration through fire-polished Pasteur pipettes of progressively smaller opening sizes, cells were plated on poly-d-lysine- and laminin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)-coated plates. Cells were allowed to adhere for several hours at room temperature in a humidified chamber and then nourished with Liebovitz L-15 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM glucose, 10 mM phosphate buffer, and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology.

Whole cell patch-clamp experiments were performed on isolated mouse DRG neurons within 24 h of dissociation using a MultiClamp 700B (Molecular Devices) patch-clamp amplifier and PClamp 9 acquisition software (Molecular Devices) at room temperature. Recordings were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz (Digidata 1550B, Molecular Devices). Pipettes (outer diameter, 1.5 mm; inner diameter, 1.1 mm; BF150-110-10, Sutter Instruments) were pulled using a PC-100 puller (Narishige) and heat polished to resistance of 3–5 MΩ using a microforge (MF-83, Narishige). Series resistance was typically 7 MΩ and was compensated up to 60%. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices). All neurons included in the analysis had a resting membrane potential (RMP) more negative than −40 mV. The RMP was recorded 1–3 min after whole cell configuration was achieved.

In current-clamp mode, cells were held at −60 mV and action potentials (AP) were elicited by injecting slow ramp currents from 100 to 700 pA with a change (Δ) of 200 pA over 1 s to mimic slow depolarization. Basic membrane properties of AP threshold, AP amplitude, half-width, and rheobase were measured using a standard step protocol of 5-ms duration, depolarizing the cell in 10-pA increments until a single action potential was fired. A series of small hyperpolarizing steps of 500-ms duration were applied to the cell in current-clamp mode, and a regression fit on the resultant current-voltage (I-V) relationship was used to determine the input resistance. The pipette solution contained the following (in mM): 120 K-gluconate, 6 KCl, 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Na, 0.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 10 phosphocreatine, pH 7.3 (adjusted with N-methylglucamine), and osmolarity was ~290 mosM. The external solution contained the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (adjusted with N-methylglucamine), and osmolarity was adjusted to ~315 mosM with sucrose.

Voltage-clamp measurements of calcium currents were performed as described previously (Choe et al. 2011). To achieve rundown of high-voltage-activated (HVA) calcium channels and isolate low-voltage-activated (LVA) T-type channels, a hydrofluoric acid (HF)-based patch pipette solution was used in these experiments composed of (in mM) 135 tetramethylammonium hydroxide, 10 EGTA, 40 HEPES, and 2 MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with hydrofluoric acid, ~310 mosM. The external solution contained (in mM) 152 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 10 mM HEPES, and 2 mM CaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.4 with TEA-OH, ~320 mosM. Leak subtraction was performed online using a P/4 subtraction protocol.

Drugs and treatment.

eFT508 was provided by eFFECTOR under a material transfer agreement with University of Texas at Dallas. The drug was dissolved to a stock concentration of 10 mM in DMSO and diluted further to a working concentration of 25 nM before use in experiments. In culture groups requiring eFT508 treatment, the cells were exposed to the drug overnight for 15–16 h by diluting the drug in the complete L-15 medium. During patch experiments, eFT508 was diluted in the external recording solution. Recombinant mouse IL-6 protein was purchased from R&D Systems and diluted in 0.1% BSA in PBS. IL-6 was used at a final concentration of 50 ng/mL with total treatment time of ~1.5 h. IL-6 was diluted in the complete L-15 medium to expose the cells to it and later in the recording external solution while patch experiments were conducted. BSA (0.1%) in PBS was used across all experiments as the vehicle treatment. The specific T-type calcium channel blocker TTA-P2 was purchased from Alomone Laboratories, diluted to a stock concentration of 25 mM in DMSO, and dissolved in external solution to a working concentration of 2 µM. In experiments testing the effect of TTA-P2, the drug was directly applied to the patched cell for 2–4 min after baseline recordings were obtained. The appropriate recording protocol was then run, and TTA-P2 was continuously applied until the end of the experiment.

Drug screening.

eFT508 was submitted to the Psychoactive Drug Screening Platform at University of North Carolina for radioligand binding analysis, as described previously (Besnard et al. 2012). eFT508 was screened at 10 μM in all binding assays.

Data analysis.

Analysis of electrophysiology traces were performed using either Clampfit 10 or Axograph software. Comparison between groups was done using one-way or two-way ANOVA as appropriate, followed by Dunnett’s test to assess changes in all experimental groups relative to the vehicle group. In experiments measuring ramp-induced excitability changes before and after the application of TTA-P2, a repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction was employed. Paired t test was used to compare changes in membrane properties after TTA-P2. Data are represented in the results and figures as means ± SE. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the comparisons between vehicle and IL-6 groups, or within the IL-6 group before and after TTA-P2, that showed statistical significance, we also reported the mean difference and the 95% confidence intervals in appropriate figure legends. All data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software, and figures were composed in Inkscape (https://www.inkscape.org/).

RESULTS

MNK1/2 inhibition by eFT508 prevents IL-6 induced hyperexcitability in DRG nociceptors.

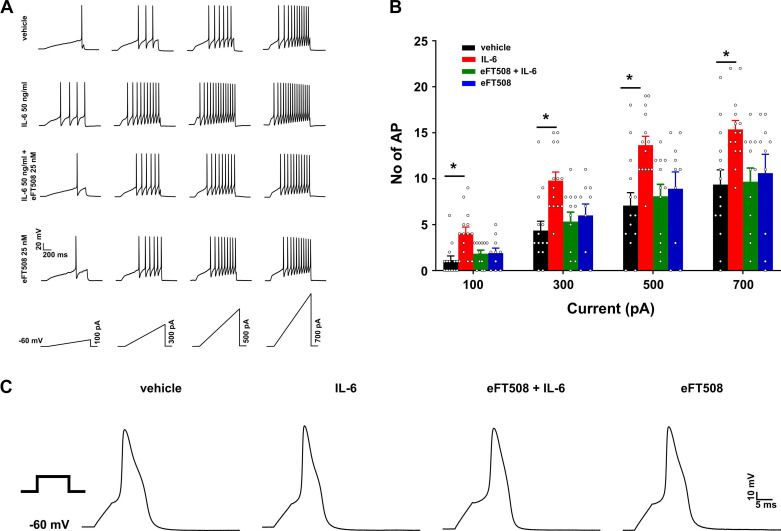

A hallmark sign of sensitization of primary afferent nociceptors is prolonged firing to suprathreshold stimuli and a reduced threshold for action potential generation (Levine et al. 1993). We tested the response of cultured DRG nociceptors to 1 h of IL-6 exposure to assess modulation of their excitability and the effects of MNK inhibition on these responses. The four treatment groups were vehicle for 1 h (5 µL/mL; n = 14 cells), IL-6 for 1 h (50 ng/mL, n = 14 cells), eFT508 (25 nM) pretreatment for ~15 h followed by addition of IL-6 for 1 h (IL-6+eFT508; n = 11 cells), and eFT508 only for ~15 h (n = 10 cells). The mean diameter of cells sampled in each group were similar (in µm; vehicle, 27.59 ± 0.86; IL-6, 26.51 ± 0.7; IL-6+eFT508, 27.39 ± 0.9; eFT508, 28.25 ± 1.5; one-way ANOVA: F3,45 = 0.53, P = 0.666). Ramp currents were injected into the cells to elicit action potential firing (Fig. 1A). If a cell was nonresponsive to each of the four ramps, then a 1,000-pA, 1-s ramp was injected; only cells that fired a minimum of one action potential to this 1,000-pA ramp were included for further analysis. Such cells were assigned action potential counts of 0 for each of the ramps. IL-6 treatment significantly increased the number of action potentials elicited by the ramp protocol at all four intensities tested. Pretreatment with eFT508 prevented IL-6 induced changes in nociceptor excitability. However, eFT508 treatment alone did not cause any changes to the excitability of the tested cells (Fig. 1B). A two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of treatment (F3,46 = 5.35, P = 0.003), and post hoc comparison using Dunnett’s test showed that there was a significant difference between the vehicle and IL-6 groups only (vehicle vs. IL-6 at 100 pA: P = 0.003, 300 pA: P = 0.001, 500 pA: P = 0.002, 700 pA: P = 0.012). Comparing the effects of IL-6 and eFT508 between cells obtained from male (M) and female (F) animals, we found that neither of the treatments had a sex-specific effect (no. of cells: IL-6, n = 10 M, 4 F; F1,12 = 0.58, P = 0.461; eFT508, n = 6 M, 4 F; F1,8 = 0.25, P = 0.626). Therefore, for all data in this article, the data obtained from male and female animals were pooled together.

Fig. 1.

MAPK-interacting kinases (MNK1/2) inhibition by eFT508 prevents IL-6-induced hyperexcitability in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptors. A: representative traces of ramp current-induced action potential firing, with ramp stimuli shown at bottom. B: for each ramp intensity tested, the IL-6 group had the highest number of action potentials (AP). The increase in spike firing was prevented by pretreatment with eFT508. No differences were seen in eFT508-treated group alone. *P < 0.05, post hoc Dunnett’s test following 2-way ANOVA. Vehicle vs. IL-6 at 100 pA: mean difference −2.93 [95% confidence interval (95CI) −4.93, −0.92]; at 300 pA: −5.43 [95CI −8.87, −1.99]; at 500 pA: −6.57 [95CI −10.87, −2.27]; at 700 pA: −6 [95 CI −10.75, −1.25]. In the vehicle vs. eFT508+IL-6 and vehicle vs. eFT508, P > 0.05. C: representative traces of single action potentials in all groups evoked at rheobase current using a step protocol. Number of cells: vehicle, 14 from 8 mice; IL-6, 14 from 9 mice; eFT508+IL-6, 12 from 4 mice; eFT508, 10 from 6 mice.

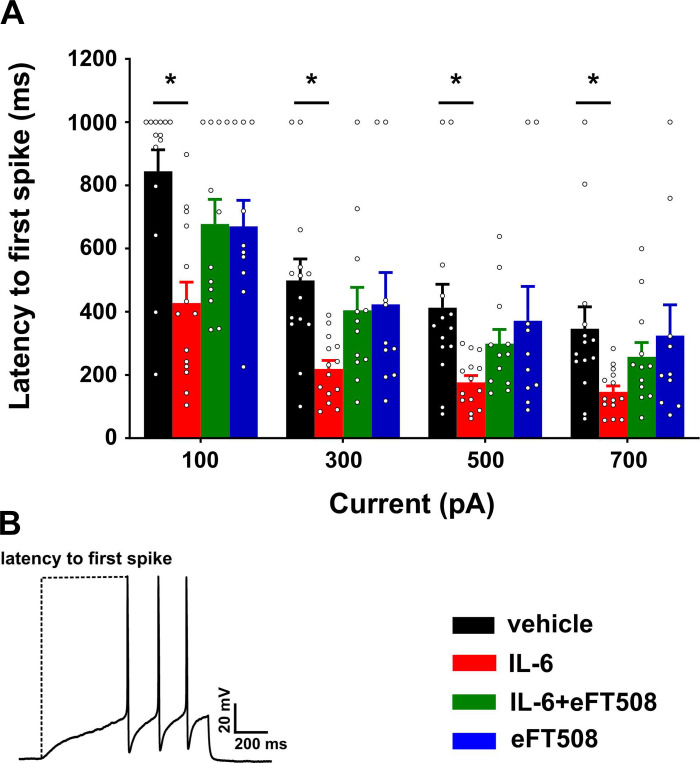

Basic membrane properties were measured using a step protocol of 5-ms duration, typically starting at 100 pA and depolarizing the neuron in 10-pA increments. Membrane properties were similar between the four treatment groups (Table 1). Representative traces of single action potentials evoked at rheobase for each of the groups are shown in Fig. 1C. Latency to first spike was measured from the ramp traces, taken as the time from initiation of the ramp until the peak of the first action potential. These data showed that the latency to the first spike was shortened in the IL-6 group at all ramp intensities, but the effect was prevented by pretreatment with eFT508 (Fig. 2A; main effect of treatment: F3,46 = 4.23, P = 0.01), and post hoc Dunnett’s test showed differences between the vehicle and IL-6 groups only (vehicle vs. IL-6 at 100 pA: P = 0.001, 300 pA: P = 0.004, 500 pA: P = 0.021, 700 pA: P = 0.035). In summary, these data confirm that 1 h of IL-6 treatment causes hyperexcitability of nociceptors in DRG cultures, and blockade of MNK signaling by eFT508 prevents the sensitization.

Table 1.

Basic membrane properties of DRG neurons

| Vehicle | IL-6 | eFT508+IL-6 | eFT508 | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cells | 14 | 14 | 11 | 10 | |

| Capacitance, pF | 29.2 ± 2.62 | 26.93 ± 1.79 | 30 ± 2.24 | 30.6 ± 2.89 | F3,45 = 0.45, P = 0.718 |

| RMP, mV | −49.89 ± 1.47 | −50.45 ± 2.31 | −51.18 ± 2 | −53.6 ± 1.58 | F3,45 = 0.65, P = 0.589 |

| AP threshold, mV | −21.86 ± 2.13 | −23.96 ± 1.7 | −22.98 ± 1.64 | −25.35 ± 1.87 | F3,45 = 0.57, P = 0.635 |

| AP amplitude, mV | 76.14 ± 2.23 | 75.77 ± 3.01 | 79.96 ± 1.12 | 80.53 ± 1.95 | F3,45 = 1.07, P = 0.372 |

| AP half-width, ms | 3.49 ± 0.21 | 3.4 ± 0.28 | 3.65 ± 0.3 | 3.72 ± 0.42 | F3,45 = 0.23, P = 0.874 |

| IR, MΩ | 716.2 ± 125.8 | 677.93 ± 79.5 | 743.59 ± 111.28 | 637.99 ± 105.38 | F3,45 = 0.16, P = 0.925 |

| Rheobase, pA | 278.57 ± 18.03 | 233.57 ± 16.49 | 269.09 ± 12.09 | 281 ± 28.58 | F3,45 = 1.42, P = 0.251 |

| AP latency, ms | 8.95 ± 0.73 | 8.39 ± 1.06 | 8.16 ± 0.79 | 7.76 ± 1.05 | F3,45) = 0.28, P = 0.843 |

AP, action potential; IR, input resistance; RMP, resting membrane potential.

Fig. 2.

MAPK-interacting kinases (MNK1/2) inhibition by eFT508 prevents IL-6-induced shift in latency to the action potential (AP) peak in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptors. A: latency to the first spike measured from the initiation of ramp until the peak of the first action potential was lowered in the IL-6 group. Pretreatment with eFT508 prevented this reduction in latency. No change was observed in the eFT508 treatment group. B: a representative trace indicating the measurement of latency. *P < 0.05, post hoc Dunnett’s test following 2-way ANOVA. Vehicle vs. IL-6 at 100 pA: mean difference 416.9 [95% confidence interval (95CI) 179, 654.8]; at 300 pA: 279.8 [95CI 90.18, 469.5]; at 500 pA: 236.1 [95CI 33.99, 438.2]; at 700 pA: 200 [95CI 12.53, 387.4]. Number of cells: vehicle, 14 from 8 mice; IL-6, 14 from 9 mice; eFT508+IL-6, 12 from 4 mice; eFT508, 10 from 6 mice.

Ongoing activity refers to the continual discharge of action potentials driven by intrinsic or extrinsic sources of excitation, and it has been shown that inflammatory agents such as 5-HT can potentiate ongoing activity in nociceptors (Odem et al. 2018). Therefore, before the ramp protocol was run, cells were held at resting membrane potential for a duration of 100 s to determine whether action potential discharge was modified by IL-6 treatment. The percentage of cells that fired an action potential during this time period did not differ between groups (vehicle = 35%, IL-6 = 50%, IL-6+eFT508 = 33%, eFT508 = 20%; F3,46 = 0.75, P = 0.53). The frequency of action potential discharge was not modified by IL-6 or eFT508 treatment either (in Hz; vehicle = 0.01, IL-6 = 0.08 ± 0.03, IL-6+eFT508 = 0.04 ± 0.02, eFT508 = 0.03 ± 0.02; F3,46 =1.58, P = 0.21). We note that the action potential frequency was much less than 1 Hz, indicating that the neurons likely did not develop spontaneous activity over this time course, at least under the room temperature conditions used here.

IL-6 treatment increases T-type calcium currents, and eFT508 pretreatment prevents this upregulation.

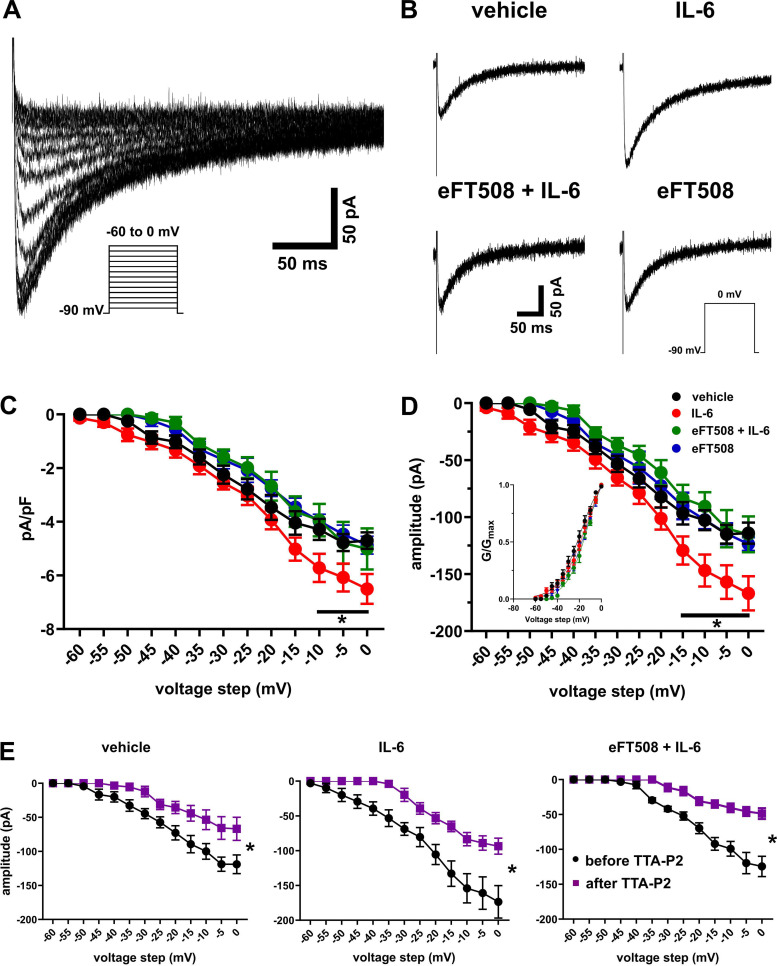

Cytokines are known to upregulate T-type channels in sensory neurons (Buckley et al. 2014; Dey et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2019; Stemkowski et al. 2017). T-type calcium channels have a key physiological role in the generation and timing of action potentials and are highly expressed in small- and medium-diameter cells in the DRG (Choe et al. 2011; Jagodic et al. 2007; Nelson et al. 2005; Watanabe et al. 2015). Therefore, we tested whether T-type calcium currents were modified by IL-6 treatment and if MNK signaling plays a role in this mechanism. T-type calcium currents were recorded in voltage-clamp mode using an HF-based patch pipette solution to facilitate rundown of slow HVA currents. Rundown of slowly inactivating HVA currents was achieved ~15 min after whole cell configuration was reached. Prior to measuring LVA currents, in a subset of the cells we tested whether HVA currents were rundown at 15 min by holding the cell at −50 mV and applying step voltages from −40 mV to 0 mV (Herrington and Lingle 1992). At a holding potential of −50 mV, no LVA currents are activated, and therefore all currents are taken to be HVA. As a precaution to prevent contamination with residual HVA currents that remained in some cells, analyses of all current amplitudes obtained for measuring T-type currents were performed from the peak of amplitude to the end of the depolarizing test potential as described by others (Li et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2019; Todorovic and Lingle 1998). Using the HF-based patch solution, we observed inward currents of small amplitudes, i.e., exclusive of “T-rich” cells (Jevtovic-Todorovic and Todorovic 2006; Joksimovic et al. 2018; Nelson et al. 2005). Figure 3A shows a typical trace from a holding voltage of −90 mV and with voltage stepping from −60 mV to 0 mV in 5-mV increments. Example traces of the amplitudes of T-type currents obtained from a holding potential of −90 mV and step to 0 mV for all four groups are shown in Fig. 3B. Inward currents were seen in all cells tested. The density (amplitude normalized to capacitance of the cells) of the currents measured showed that T-type channel currents were increased after IL-6 treatment, and this effect was prevented by the pretreatment with eFT508 (Fig. 3C; main effect of treatment: F3,416 = 24.41, P < 0.001; no. of cells: vehicle, n = 10; IL-6, n = 11; eFT508+IL-6, n = 8; eFT508, n = 7). Similarly, the amplitudes of the currents showed the largest difference between the vehicle- and IL-6-treated groups (Fig. 3D; main effect of treatment: F3,416 = 33.69, P < 0.001). Significant differences between the vehicle and IL-6 groups were observed for both measures from test potentials above −15 mV with the peak at 0 mV (Fig. 3, C and D). Using the amplitudes in Fig. 3D, we plotted the activation curve (Fig. 3D, inset) to determine if the gating properties of the channel were modified by IL-6 treatment. No differences were observed between the four groups (F3,48 = 0.13, P = 0.942). The half-maximal activation (V50) values were not different between the treatment groups (in mV; vehicle = −22.88 ± 1.67, IL-6 = −20.62 ± 1.62, eFT508+IL-6 = −17.75 ± 1.19, eFT508 = −19.07 ± 1.92; F3,32 = 1.770, P = 0.173), indicating that the gating properties of the channels had not been altered by IL-6 treatment. Furthermore, we applied the T-type channel antagonist TTA-P2 at the end of the experiment in some cells in the vehicle, IL-6, and eFT508+IL-6 groups. TTA-P2 reduced the amplitudes of currents at all voltage steps tested [Fig. 3E; before and after TTA-P2: vehicle (n = 6 cells), F1,65 = 295.4, P < 0.001; IL-6 (n = 7), F1,78 = 210.7, P < 0.001; eFT508 + IL-6 (n = 7), F1,78 = 498.7, P < 0.001). The capacitance (in pF; vehicle, 23.9 ± 1.27; IL-6, 25.7 ± 1.17; eFT508 + IL-6, 24.1 ± 1.6; eFT508, 25.8 ± 1.6; F3,34 = 0.54, P = 0.65) of the cells in the four groups were similar. Taken together, these data suggest that IL-6 treatment increases the amplitude of T-type currents, and MNK inhibition with eFT508 prevents this change.

Fig. 3.

IL-6 treatment increases T-type calcium currents, and eFT508 pretreatment prevents this upregulation. A: representative traces of inward T-type calcium currents evoked from a holding potential of −90 mV and stepping from −60 mV to 0 mV in 5-mV increments. B: representative traces from all treatment groups, from a holding potential of −90 mV and test potential of 0 mV, showing that IL-6 treatment increases the amplitude of T-type currents. C: current-voltage (I-V) curves of the calcium current density (pA/pF). *P < 0.05, post hoc Dunnett’s test following 2-way ANOVA. Vehicle vs. IL-6 at −10 mV: mean difference 1.434 [95% confidence interval (95CI) 0.33, 2.54]; at −5 mV: 1.3 [95CI 0.19, 2.41]; at 0 mV: 1.8 [95CI 0.68, 2.91]. D: I-V curves of the current amplitudes used to obtain the density in C. *P < 0.05, post hoc Dunnett’s test following 2-way ANOVA. Vehicle vs. IL-6 at −15 mV: mean difference 32.59 [95% confidence interval (95CI) 5.06, 60.12]; at −10 mV: 44.17 [95CI 16.64, 71.7]; at −5 mV: 41.96 [95CI 14.44, 69.49]; at 0 mV: 52.81 [25.28, 80.34]. Inset shows the activation curve G/Gmax. The curve was obtained by fitting the conductances (G) of the amplitudes from D and estimated reversal potential (Erev) of 60 mV to the equation G/Gmax = 1/{1 + exp[(V50 − V)/slope]}, where V50 is the voltage at which current is half-maximal and V is the step voltage. E: average amplitudes of a subset of cells from D showing the effect of application of TTA-P2 on T-type calcium currents. TTA-P2 application depresses the amplitude of T-type currents. Data are shown for the vehicle, IL-6, and eFT508+IL-6 groups. *P < 0.05, main effect of treatment, repeated measures ANOVA. Number of cells: vehicle, 10 from 5 mice; IL-6, 11 from 6 mice; eFT508+IL-6, 8 from 2 mice; eFT508, 7 from 3 mice.

The T-type calcium channel antagonist TTA-P2 modifies IL-6 induced changes in membrane properties of DRG neurons.

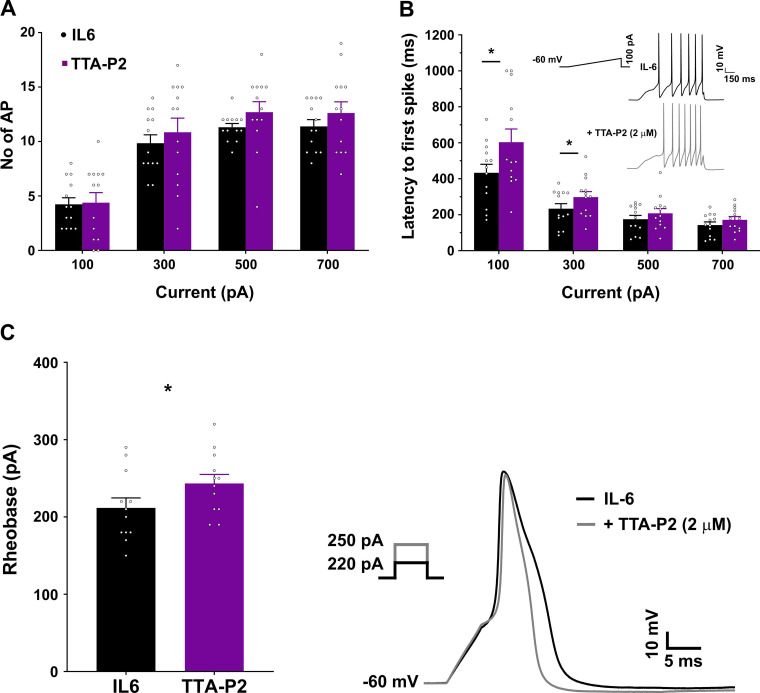

Antagonism of T-type channels in hyperexcitable DRG neurons in a rodent model of surgical pain was effective in dampening the increased firing rates (Joksimovic et al. 2018). To examine whether T-type channels contribute to the increased excitability of DRG neurons following IL-6 treatment, we tested the effect of the T-type channel antagonist TTA-P2 (2 µM) on excitability of neurons exposed to 1 h of IL-6 (capacitance 24.69 ± 0.9 pF). Action potentials were elicited using the ramp protocol described previously and then using the step protocol to determine rheobase current. Following these initial recordings, TTA-P2 was applied to the patched neuron and the ramp and rheobase protocol were repeated. A total of 13 cells were tested. TTA-P2 did not alter the resting membrane potential of the cells (in mV; IL-6, −55.54 ± 1.5; +TTA-P2, −54.23 ± 1.97; P = 0.338). In response to the ramp protocol, TTA-P2 did not induce a change in the number of action potentials (Fig. 4A; F1,12 = 2.74, P = 0.124). However, we did observe a trend toward an increase in the number of action potentials, particularly at the higher ramp intensities of 500 and 700 pA. TTA-P2 caused a reduction in the half-width of the action potentials (in ms; IL-6, 4 ± 0.15, +TTA-P2, 2.75 ± 0.11; paired t test, P < 0.001), which may in turn contribute to the higher number of spikes generated after application of the antagonist. TTA-P2 application reversed some of the changes in the latency caused by IL-6 treatment, particularly at the lower 100-pA and 300-pA ramp intensities (Fig. 4B; F1,12 = 10.82, P = 0.007; 100 pA: P < 0.0001, 300 pA: P = 0.016). The step protocol used to assess rheobase showed that after TTA-P2 application, more current was required to elicit an action potential (Fig. 4C; IL-6, 211 ± 12.3; +TTA-P2, 243.33 ± 11.18; P < 0.001). It appears that in our experiments the action of TTA-P2 may be more effective at smaller depolarizations, as the largest effects were observed with rheobase current and at 100- and 300-pA ramps. With stronger depolarizations, the antagonism of T-type channels may no longer have an effect on spike firing. Indeed, in response to suppressing tonic firing, TTA-P2 appears to be more effective at smaller depolarizations only (Joksimovic et al. 2018; Stamenic et al. 2019).

Fig. 4.

T-type calcium channel antagonist TTA-P2 modifies IL-6-induced changes in membrane properties of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. A: TTA-P2 does not alter the number of action potentials (AP) in IL-6-treated cells in response to ramp currents. B: following 1 h of IL-6 treatment, the latency to the first spike is decreased, and this is reversed following the application of TTA-P2 at 100-pA and 300-pA ramp intensities. Inset shows representative traces from the same cell before and after TTA-P2 application indicating increased latency at 100 pA. *P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni correction following 2-way ANOVA. Mean difference at 100 pA: −170.3 [95% confidence interval (95CI) −224.9, −115.6]; at 300 pA: −64.07 [95CI −118.7, −9.41]. C, left: the rheobase to evoke an action potential is increased following TTA-P2 application. Right, representative traces from the same IL-6-treated cell before and after TTA-P2 application in response to a 5-s step protocol. The current required to evoke an action potential increases from 220 pA to 250 pA after TTA-P2 application. *P < 0.05, paired t test. Mean difference: 31.67 [95CI 17.63, 45.7]. Number of cells: 13 from 3 mice.

Specificity of eFT508.

eFT508 is a very specific inhibitor of MNK versus other kinases (Reich et al. 2018) but no reports exist of its specificity versus common neuronal targets. To address this directly, eFT508 (10 μM) was screened in binding assays against a list of targets shown in Table 2 (Besnard et al. 2012). eFT508 did not show appreciable activity at most targets, except the brain benzodiazepine receptor and the 5-HT2B receptor. For the 5-HT2B receptor, the Ki was measured at 2.5 μM, suggesting that 25 nM eFT508 likely has negligible effect at this receptor. We conclude that off-target effects of eFT508 are unlikely to explain observations in our electrophysiology experiments.

Table 2.

Off-target screen for eFT508 done at 10 μM in binding assays against listed human receptors

| Receptor | Mean Binding Displacement, % | Ki, μM |

|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | ||

| 5-HT1A | N/A | |

| 5-HT1B | N/A | |

| 5-HT1D | 27.66 | |

| 5-HT1E | N/A | |

| 5-HT2A | N/A | |

| 5-HT2B | 62.01 | 2.5 |

| 5-HT2C | N/A | |

| 5-HT3 | N/A | |

| 5-HT5A | N/A | |

| 5-HT6 | N/A | |

| 5-HT7A | 23.51 | |

| Adrenergic | ||

| α1A | 25.97 | |

| α1B | 27.44 | |

| α1D | 32.14 | |

| α2A | N/A | |

| α2B | N/A | |

| α2C | N/A | |

| β1 | N/A | |

| β2 | N/A | |

| β3 | N/A | |

| BZP rat brain site | 88.17 | |

| Dopamine | ||

| D1 | N/A | |

| D2 | N/A | |

| D3 | N/A | |

| D4 | N/A | |

| D5 | N/A | |

| DAT | 36.49 | |

| DOR | N/A | |

| GABAA | N/A | |

| Histamine | N/A | |

| H1 | ||

| H2 | N/A | |

| H3 | N/A | |

| H4 | N/A | |

| KOR | 41.05 | |

| Muscarinic | ||

| M1 | N/A | |

| M2 | N/A | |

| M3 | N/A | |

| M4 | N/A | |

| M5 | N/A | |

| MOR | N/A | |

| NET | N/A | |

| PBR | 22.15 | |

| SERT | N/A | |

| σ1 | N/A | |

| σ2 | N/A | |

| HERG | N/A |

Off-target screening for eFT508 was done at 10 μM in binding assays against the listed human receptors. BZP, benzylpiperazine; DAT, dopamine transporter; DOR, δ-opioid receptor; HERG, human ether-a-go-go-related gene; KOR, κ-opioid receptor; MOR, μ-opioid receptor; NET, norepinephrine transporter; PBR, peripheral benzodiazepine receptor; SERT, serotonin transporter. An effect <20% is shown as N/A. Ki was only measured for 5-HT2B.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we replicated our prior work showing that treatment of cultured sensory neurons with IL-6 causes hyperexcitability in response to ramp current injection and reduces the latency to the first action potential (Moy et al. 2017; Yan et al. 2012). These changes were prevented when the cultures were pretreated with the MNK1/2 inhibitor eFT508, further confirming our previous work showing that the generation of nociceptor excitability, accompanied by the upregulation of voltage-gated sodium channels (VGNaCs), in response to an inflammatory mediator is dependent on eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK1/2 (Moy et al. 2017). The Nav1.7 sodium channel has been implicated in alterations in excitability measures in nociceptors (Stamboulian et al. 2010). Phosphorylation of Nav1.7 by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) resulted in an increase in the number of action potentials and the reduction of the latency to the first spike, and inhibition of pERK1/2 by U0126 resulted in a reversal of both measures (Stamboulian et al. 2010). In addition to the effects on VGNaCs shown previously, we now show that IL-6 can influence other types of voltage-gated channels that control action potential properties, as well. Here we investigated the role of T-type calcium channels in IL-6-induced neuronal excitability. We found that following IL-6 treatment, the amplitude of T-type currents was increased in DRG neurons, and MNK inhibition by pretreatment with eFT508 prevented the alteration in T-type currents. Application of the T-type channel antagonist TTA-P2 resulted in reduction of peak amplitudes of currents by ~50–60% in the cells tested. T-type channel antagonists such as TTA-P2 or TTA-A2 have been shown to have state-dependent effects in the rodent DRG with larger fractional block of T-type channels at depolarized potentials (Choe et al. 2011; Francois et al. 2013). TTA-P2 may have a higher preference for the channels in their inactive state, thus being more effective at blocking the T-type currents at depolarized membrane potentials (Choe et al. 2011). In current-clamp experiments, in cultures treated with IL-6, we found that application of TTA-P2 increased the current threshold (rheobase) required to elicit action potential firing and increased the latency to the first spike. These effects are consistent with the role of T-type currents in modulating action potential firing properties. The effect on latency may be either complementary to the increase in the rheobase current or a consequence of the absence of the preamplifier effect provided by the T-type current to sodium channels. The reduction in the half-width of the action potential after TTA-P2 application in the IL-6 treated cells is unclear. Blair and Bean (2002) reported on the presence of a mibefradil-sensitive current in the repolarizing phase of the action potential in DRG neurons. In our data, a block of this LVA component may have contributed to the shortened half-width, an effect that can lead to reduced neurotransmitter release efficiency (Blair and Bean 2002; Davidson et al. 2014).

T-type channels control neuronal excitability, possibly serving as a “preamplifier” favoring sodium spike generation, and control both tonic and rebound firing (Bourinet et al. 2016; Stamenic and Todorovic 2018). The role of T-type calcium channels have been extensively studied in pain processing (Choi et al. 2007; Bourinet et al. 2016). Behavioral studies provide evidence that T-type channel antagonism induces mechanical and thermal antinociception (Todorovic et al. 2002). Silencing of the Cav3.2 isoform using antisense oligonucleotides has antihyperalgesic effects in diabetic rats (Messinger et al. 2009). Moreover, intraperitoneal (IP) injections of the selective Cav3.2 antagonist TTA-P2 produce antinociceptive effects in the formalin pain model, and reversal of neuropathic hyperalgesia demonstrated by normalization of thermal paw withdrawal latency in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats (Choe et al. 2011). Following skin incision surgery in rats, Joksimovic et al. (2018) demonstrated that the membrane fraction of Cav3.2 channels was increased in the DRG, although not accompanied by change in protein or mRNA levels. In the Joksimovic et al. study, TTA-P2 was effective in relieving thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity following incision and in lowering the hyperexcitability of DRG neurons.

A causative link between cytokines/inflammatory mediators and upregulation of Cav3.2 T-type channels has been reported previously (Buckley et al. 2014; Dey et al. 2011; Stemkowski et al. 2017). Following spinal nerve ligation (SNL), both IL-6 and gp130 expression are elevated compared with their expression in sham-operated rats (Liu et al. 2019). Furthermore, FIL-6 (a mixture of IL-6 and the soluble IL-6 receptor, sIL-6) increases expression in Cav3.2 expression in DRG cultures, an effect reversed by pretreatment with an IL-6 sequestering strategy or ruxolintib (Liu et al. 2019). The mechanism underlying cytokines’ effects on voltage-gated channels may be their ability to traffic channels to the membrane. Indeed, disruption of actin cytoskeleton can block cytokine-induced upregulation via membrane insertion of T-type currents (Dey et al. 2011). And a similar mechanism has also been demonstrated in colonic nociceptors in a model of irritable bowel syndrome (Marger et al. 2011). We can therefore speculate that in our work, the IL-6-induced upregulation of voltage-gated channels may occur via a mechanism where they are increasingly trafficked to the membrane. Under this pathological condition, MNK inhibition may prevent the trafficking and thereby have a normalizing effect on neuronal hyperexcitability. In support of our hypothesis, ERK/MAP kinase-dependent signaling has been implicated in trafficking of ion channels. For example, trafficking of Cav3.2 voltage-gated channels to the membrane in herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1-infected cells by IL-6 has been shown to occur via an ERK1/2-dependent signaling mechanism (Zhang et al. 2019). In summary, these studies support our conclusion that IL-6-induced nociceptor excitability may arise from ERK/MNK/eIF4E-mediated trafficking of ion channels, potentially via selective translation of the mRNA of a scaffolding or trafficking protein.

The work presented here showing that IL-6 induces hyperexcitability accompanied by increased T-type current amplitudes in DRG neurons complements our prior findings on IL-6-induced upregulation of voltage-gated sodium currents (Moy et al. 2017). Both of these effects implicate the ERK/MNK/eIF4E pathway. In the case of the VGNaCs, either the pharmacological inhibition of MNK or the lack of the phosphorylation site for MNK on eIF4E prevents their IL-6-induced upregulation. Similarly, here we have shown that the action potential properties as well as T-type current amplitudes modified by IL-6 are normalized by the MNK inhibitor eFT508. Taken together, our data add to the understanding of the cytokine-induced sensitization of neurons mediated via membrane trafficking of voltage-gated channels. Our hypothesis is supported by prior evidence that the Ras mutant V12S35Ras, which activates Raf-1 (an upstream activator of MNK), can potentiate voltage-gated calcium currents via modulation of existing channels rather than increased synthesis of new ones via Ras-mediated gene expression (Fitzgerald 2000). Upregulation of voltage-gated channels resulting in increased excitability of nociceptors underlies the pathophysiology of many pain states (Dib-Hajj et al. 2009; Duzhyy et al. 2015; Joksimovic et al. 2018). eFT508 is highly specific to MNK without known off-target effects, and when applied to DRG neurons by itself, it does not induce any changes to action potential properties. Therefore, our work offers a clear opportunity for therapeutic intervention that decreases nociceptor excitability via MNK inhibition using eFT508.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS065926.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.J., T.P., and G.D. conceived and designed research; V.J. performed experiments; V.J., A.K.A.S., F.M., and C.M.S. analyzed data; V.J., T.P., and G.D. interpreted results of experiments; V.J. prepared figures; V.J. drafted manuscript; V.J., T.P., and G.D. edited and revised manuscript; V.J., A.K.A.S., F.M., C.M.S., T.P., and G.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Arruda JL, Colburn RW, Rickman AJ, Rutkowski MD, DeLeo JA. Increase of interleukin-6 mRNA in the spinal cord following peripheral nerve injury in the rat: potential role of IL-6 in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 62: 228–235, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard J, Ruda GF, Setola V, Abecassis K, Rodriguiz RM, Huang XP, Norval S, Sassano MF, Shin AI, Webster LA, Simeons FRC, Stojanovski L, Prat A, Seidah NG, Constam DB, Bickerton GR, Read KD, Wetsel WC, Gilbert IH, Roth BL, Hopkins AL. Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature 492: 215–220, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BJ, Atmaramani R, Kumaraju R, Plagens S, Romero-Ortega M, Dussor G, Price TJ, Campbell ZT, Pancrazio JJ. Adult mouse sensory neurons on microelectrode arrays exhibit increased spontaneous and stimulus-evoked activity in the presence of interleukin-6. J Neurophysiol 120: 1374–1385, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00158.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ current, TTX-resistant Na+ current, and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci 22: 10277–10290, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10277.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Francois A, Laffray S. T-type calcium channels in neuropathic pain. Pain 157, Suppl 1: S15–S22, 2016. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MM, O’Halloran KD, Rae MG, Dinan TG, O’Malley D. Modulation of enteric neurons by interleukin-6 and corticotropin-releasing factor contributes to visceral hypersensitivity and altered colonic motility in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Physiol 592: 5235–5250, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chi YN, Kang XJ, Liu QY, Zhang HL, Li ZH, Zhao ZF, Yang Y, Su L, Cai J, Liao FF, Yi M, Wan Y, Liu FY. Accumulation of Ca(v) 3.2 T-type calcium channels in the uninjured sural nerve contributes to neuropathic pain in rats with spared nerve injury. Front Mol Neurosci 11: 24, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe W, Messinger RB, Leach E, Eckle VS, Obradovic A, Salajegheh R, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. TTA-P2 is a potent and selective blocker of T-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons and a novel antinociceptive agent. Mol Pharmacol 80: 900–910, 2011. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Na HS, Kim J, Lee J, Lee S, Kim D, Park J, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Shin HS. Attenuated pain responses in mice lacking CaV3.2 T-type channels. Genes Brain Behav 6: 425–431, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Copits BA, Zhang J, Page G, Ghetti A, Gereau RW 4th. Human sensory neurons: membrane properties and sensitization by inflammatory mediators. Pain 155: 1861–1870, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jongh RF, Vissers KC, Meert TF, Booij LH, De Deyne CS, Heylen RJ. The role of interleukin-6 in nociception and pain. Anesth Analg 96: 1096–1103, 2003. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055362.56604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeo JA, Colburn RW, Nichols M, Malhotra A. Interleukin-6-mediated hyperalgesia/allodynia and increased spinal IL-6 expression in a rat mononeuropathy model. J Interferon Cytokine Res 16: 695–700, 1996. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey D, Shepherd A, Pachuau J, Martin-Caraballo M. Leukemia inhibitory factor regulates trafficking of T-type Ca2+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C576–C587, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00115.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab S, Kumarasiri M, Yu M, Teo T, Proud C, Milne R, Wang S. MAP kinase-interacting kinases–emerging targets against cancer. Chem Biol 21: 441–452, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib-Hajj SD, Binshtok AM, Cummins TR, Jarvis MF, Samad T, Zimmermann K. Voltage-gated sodium channels in pain states: role in pathophysiology and targets for treatment. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 60: 65–83, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Tulunay FC, Lai J, Porreca F. Reversal of experimental neuropathic pain by T-type calcium channel blockers. Pain 105: 159–168, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzhyy DE, Viatchenko-Karpinski VY, Khomula EV, Voitenko NV, Belan PV. Upregulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in long-term diabetes determines increased excitability of a specific type of capsaicin-insensitive DRG neurons. Mol Pain 11: 29, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald EM. Regulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels in rat sensory neurones involves a Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Physiol 527: 433–444, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois A, Kerckhove N, Meleine M, Alloui A, Barrere C, Gelot A, Uebele VN, Renger JJ, Eschalier A, Ardid D, Bourinet E. State-dependent properties of a new T-type calcium channel blocker enhance CaV3.2 selectivity and support analgesic effects. Pain 154: 283–293, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington J, Lingle CJ. Kinetic and pharmacological properties of low voltage-activated Ca2+ current in rat clonal (GH3) pituitary cells. J Neurophysiol 68: 213–232, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Nelson MT, Mancuso S, Joksovic PM, Rosenberg ER, Bayliss DA, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Cell-specific alterations of T-type calcium current in painful diabetic neuropathy enhance excitability of sensory neurons. J Neurosci 27: 3305–3316, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4866-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. The role of peripheral T-type calcium channels in pain transmission. Cell Calcium 40: 197–203, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Baba H, Brenner GJ, Woolf CJ. Nociceptive-specific activation of ERK in spinal neurons contributes to pain hypersensitivity. Nat Neurosci 2: 1114–1119, 1999. doi: 10.1038/16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksimovic SL, Joksimovic SM, Tesic V, García-Caballero A, Feseha S, Zamponi GW, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Selective inhibition of CaV3.2 channels reverses hyperexcitability of peripheral nociceptors and alleviates postsurgical pain. Sci Signal 11: eaao4425, 2018. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aao4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoutorsky A, Price TJ. Translational control mechanisms in persistent pain. Trends Neurosci 41: 100–114, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konicek BW, Stephens JR, McNulty AM, Robichaud N, Peery RB, Dumstorf CA, Dowless MS, Iversen PW, Parsons S, Ellis KE, McCann DJ, Pelletier J, Furic L, Yingling JM, Stancato LF, Sonenberg N, Graff JR. Therapeutic inhibition of MAP kinase interacting kinase blocks eukaryotic initiation factor 4E phosphorylation and suppresses outgrowth of experimental lung metastases. Cancer Res 71: 1849–1857, 2011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Peptides and the primary afferent nociceptor. J Neurosci 13: 2273–2286, 1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tatsui CE, Rhines LD, North RY, Harrison DS, Cassidy RM, Johansson CA, Kosturakis AK, Edwards DD, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Dorsal root ganglion neurons become hyperexcitable and increase expression of voltage-gated T-type calcium channels (Cav3.2) in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain 158: 417–429, 2017. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Chen W, Fan X, Wang J, Fu S, Cui S, Liao F, Cai J, Wang X, Huang Y, Su L, Zhong L, Yi M, Liu F, Wan Y. Upregulation of interleukin-6 on Cav3.2 T-type calcium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons contributes to neuropathic pain in rats with spinal nerve ligation. Exp Neurol 317: 226–243, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marger F, Gelot A, Alloui A, Matricon J, Ferrer JF, Barrère C, Pizzoccaro A, Muller E, Nargeot J, Snutch TP, Eschalier A, Bourinet E, Ardid D. T-type calcium channels contribute to colonic hypersensitivity in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 11268–11273, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100869108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews EA, Dickenson AH. Effects of ethosuximide, a T-type Ca(2+) channel blocker, on dorsal horn neuronal responses in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 415: 141–149, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)00812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megat S, Ray PR, Moy JK, Lou TF, Barragán-Iglesias P, Li Y, Pradhan G, Wanghzou A, Ahmad A, Burton MD, North RY, Dougherty PM, Khoutorsky A, Sonenberg N, Webster KR, Dussor G, Campbell ZT, Price TJ. Nociceptor translational profiling reveals the Ragulator-Rag GTPase complex as a critical generator of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 39: 393–411, 2019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2661-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melemedjian OK, Asiedu MN, Tillu DV, Peebles KA, Yan J, Ertz N, Dussor GO, Price TJ. IL-6- and NGF-induced rapid control of protein synthesis and nociceptive plasticity via convergent signaling to the eIF4F complex. J Neurosci 30: 15113–15123, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3947-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger RB, Naik AK, Jagodic MM, Nelson MT, Lee WY, Choe WJ, Orestes P, Latham JR, Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. In vivo silencing of the CaV3.2 T-type calcium channels in sensory neurons alleviates hyperalgesia in rats with streptozocin-induced diabetic neuropathy. Pain 145: 184–195, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy JK, Khoutorsky A, Asiedu MN, Black BJ, Kuhn JL, Barragán-Iglesias P, Megat S, Burton MD, Burgos-Vega CC, Melemedjian OK, Boitano S, Vagner J, Gkogkas CG, Pancrazio JJ, Mogil JS, Dussor G, Sonenberg N, Price TJ. The MNK-eIF4E signaling axis contributes to injury-induced nociceptive plasticity and the development of chronic pain. J Neurosci 37: 7481–7499, 2017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0220-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PG, Grondin J, Altares M, Richardson PM. Induction of interleukin-6 in axotomized sensory neurons. J Neurosci 15: 5130–5138, 1995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM. The endogenous redox agent l-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. J Neurosci 25: 8766–8775, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odem MA, Bavencoffe AG, Cassidy RM, Lopez ER, Tian J, Dessauer CW, Walters ET. Isolated nociceptors reveal multiple specializations for generating irregular ongoing activity associated with ongoing pain. Pain 159: 2347–2362, 2018. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83: 117–161, 2003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich SH, Sprengeler PA, Chiang GG, Appleman JR, Chen J, Clarine J, Eam B, Ernst JT, Han Q, Goel VK, Han EZ, Huang V, Hung IN, Jemison A, Jessen KA, Molter J, Murphy D, Neal M, Parker GS, Shaghafi M, Sperry S, Staunton J, Stumpf CR, Thompson PA, Tran C, Webber SE, Wegerski CJ, Zheng H, Webster KR. Structure-based design of pyridone-aminal eFT508 targeting dysregulated translation by selective mitogen-activated protein kinase interacting kinases 1 and 2 (MNK1/2) inhibition. J Med Chem 61: 3516–3540, 2018. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KE, Lunardi N, Boscolo A, Dong X, Erisir A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Immunohistological demonstration of CaV3.2 T-type voltage-gated calcium channel expression in soma of dorsal root ganglion neurons and peripheral axons of rat and mouse. Neuroscience 250: 263–274, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiers S, Mwirigi J, Pradhan G, Kume M, Black B, Barragan-Iglesias P, Moy JK, Dussor G, Pancrazio JJ, Kroener S, Price TJ. Reversal of peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain and cognitive dysfunction via genetic and tomivosertib targeting of MNK. Neuropsychopharmacology 45: 524–533, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0537-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136: 731–745, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamboulian S, Choi JS, Ahn HS, Chang YW, Tyrrell L, Black JA, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD. ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates sodium channel Na(v)1.7 and alters its gating properties. J Neurosci 30: 1637–1647, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamenic TT, Feseha S, Valdez R, Zhao W, Klawitter J, Todorovic SM. Alterations in oscillatory behavior of central medial thalamic neurons demonstrate a key role of CaV3.1 isoform of T-channels during isoflurane-induced anesthesia. Cereb Cortex 29: 4679–4696, 2019. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamenic TT, Todorovic SM. Cytosolic ATP relieves voltage-dependent inactivation of T-type calcium channels and facilitates excitability of neurons in the rat central medial thalamus. eNeuro 5: ENEURO.0016-18.2018, 2018. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0016-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemkowski PL, Garcia-Caballero A, Gadotti VM, M’Dahoma S, Chen L, Souza IA, Zamponi GW. Identification of interleukin-1 beta as a key mediator in the upregulation of Cav3.2-USP5 interactions in the pain pathway. Mol Pain 13: 1744806917724698, 2017. doi: 10.1177/1744806917724698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summer GJ, Romero-Sandoval EA, Bogen O, Dina OA, Khasar SG, Levine JD. Proinflammatory cytokines mediating burn-injury pain. Pain 135: 98–107, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teneggi V, Novotny-Diermayr V, Lee LH, Yasin M, Yeo P, Ethirajulu K, Gan SB, Blanchard SE, Nellore R, Umrani DN, Gomeni R, Teck DL, Li G, Lu QS, Cao Y, Matter A. First-in-human, healthy volunteers integrated protocol of ETC-206, an oral Mnk 1/2 kinase inhibitor oncology drug. Clin Transl Sci 13: 57–66, 2020. doi: 10.1111/cts.12678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Lingle CJ. Pharmacological properties of T-type Ca2+ current in adult rat sensory neurons: effects of anticonvulsant and anesthetic agents. J Neurophysiol 79: 240–252, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Meyenburg A, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Mechanical and thermal antinociception in rats following systemic administration of mibefradil, a T-type calcium channel blocker. Brain Res 951: 336–340, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttam S, Wong C, Price TJ, Khoutorsky A. eIF4E-dependent translational control: a central mechanism for regulation of pain plasticity. Front Genet 9: 470, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waskiewicz AJ, Johnson JC, Penn B, Mahalingam M, Kimball SR, Cooper JA. Phosphorylation of the cap-binding protein eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E by protein kinase Mnk1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 19: 1871–1880, 1999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.3.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Ueda T, Shibata Y, Kumamoto N, Shimada S, Ugawa S. Expression and regulation of Cav3.2 T-Type calcium channels during inflammatory hyperalgesia in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. PLoS One 10: e0127572, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XJ, Hao JX, Andell-Jonsson S, Poli V, Bartfai T, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Nociceptive responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice to peripheral inflammation and peripheral nerve section. Cytokine 9: 1028–1033, 1997. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Melemedjian OK, Price TJ, Dussor G. Sensitization of dural afferents underlies migraine-related behavior following meningeal application of interleukin-6 (IL-6). Mol Pain 8: 6, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Hsia SC, Martin-Caraballo M. Regulation of T-type Ca2+ channel expression by interleukin-6 in sensory-like ND7/23 cells post-herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infection. J Neurochem 151: 238–254, 2019. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]