Abstract

Background

In the UK, general practitioners (GPs) are the most commonly used providers of care for emotional concerns.

Objective

To update and synthesize literature on barriers and facilitators to GP–patient communication about emotional concerns in UK primary care.

Design

Systematic review and qualitative synthesis.

Method

We conducted a systematic search on MEDLINE (OvidSP), PsycInfo and EMBASE, supplemented by citation chasing. Eligible papers focused on how GPs and adult patients in the UK communicated about emotional concerns. Results were synthesized using thematic analysis.

Results

Across 30 studies involving 342 GPs and 720 patients, four themes relating to barriers were: (i) emotional concerns are difficult to disclose; (ii) tension between understanding emotional concerns as a medical condition or arising from social stressors; (iii) unspoken assumptions about agency resulting in too little or too much involvement in decisions and (iv) providing limited care driven by little time. Three facilitative themes were: (v) a human connection improves identification of emotional concerns and is therapeutic; (vi) exploring, explaining and negotiating a shared understanding or guiding patients towards new understandings and (vii) upfront information provision and involvement manages expectations about recovery and improves engagement in treatment.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that treatment guidelines should acknowledge: the therapeutic value of a positive GP–patient relationship; that diagnosis is a two-way negotiated process rather than an activity strictly in the doctor’s domain of expertise; and the value of exploring and shaping new understandings about patients’ emotional concerns and their management.

Keywords: Communication, emotions, mental health, primary care, professional–patient relations, qualitative research

Key Messages.

This systematic review provides an update since Cape et al.’s (2000) review.

A human connection is therapeutic.

Exploring, explaining and negotiating a shared understanding is valued.

Information provision and involvement improve engagement in treatment.

Introduction

Mental health concerns are one of the main causes of disease burden worldwide (1), with one in four people experiencing a mental illness each year (2). In the UK, primary care is the first point of contact for patients in the National Health Service (NHS), and 90% of patients with emotional concerns will be managed solely by their general practitioner (GP) (3). The mental health problems faced in primary care are often heterogeneous, not formally diagnosed and present on a continuum with symptoms of different diagnoses often inextricably linked (4). Hence, this study adopts the wider term ‘emotional concerns’ to capture the broad range of mental health problems most commonly faced in primary care.

As there are no objective biomedical tests for the diagnosis of emotional concerns, the identification and management of these concerns rely on GP–patient communication. Good GP–patient communication improves patient care (5), but communication skills are tacit and poorly defined, making them hard to operationalize in training and practice.

A previous review by Cape et al. (6) explored the frequency and effectiveness of GP ‘psychological management’ of common emotional problems, which they defined as ‘the variety of ways GPs may interact psychologically with a patient presenting emotional problems, which may include listening, showing empathy, supporting, reassuring, advising, or influencing the patient to change’ [(6); p. 313]. They found that studies generally lacked details on the nature of psychological management, but that there was positive evidence for its effectiveness with patients with emotional concerns. Given the increasing role of primary care in managing mental health problems, this review provides an update since 2000 and takes a wider approach by focusing on barriers and facilitators of GP–patient communication, thereby specifying the communication processes further and also focusing on both GP and patient perspectives.

Methods

Definition of ‘emotional concerns’

In GP consultations, patients’ mental health problems may be understood by GPs and/or patients in a number of ways. In this study, we use the term ‘emotional concerns’ to represent this diversity of experiences and understandings. We have defined the term ‘emotional concerns’ to include patients with (i) common mental health problems most often managed in primary care, specifically anxiety and depression, (ii) undifferentiated low mood, stress and/or anxiety that is subclinical or not given a diagnostic label and (iii) low mood, stress and/or anxiety that is attributed to difficult life circumstances.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies: included studies collected empirical data on how GPs and patients communicate about emotional concerns in UK primary care. Study designs consisted of qualitative and quantitative designs.

Defining ‘GP–patient’ communication: for the purpose of this review, we used Cape et al.’s definition of psychological management to include studies that involved (i) how GPs communicated with patients about their emotional concerns and/or (ii) how patients communicated with GPs about their emotional concerns. We have defined this throughout as ‘GP–patient communication’.

Types of participants: studies that involved GPs and patients. Other general practice staff, such as nurses, were excluded. Studies needed to involve adult patients who were seeking or receiving help for emotional concerns from their GP. Studies focusing on patients with serious mental illness, such as psychosis, were excluded.

Setting: routine UK general practice.

Date and location: studies analysing data collected in the UK were included because of different health care systems and organization of primary care in other countries. Other countries, such as the USA, the Netherlands and India, have private health insurance systems that may impact on how GPs decide to diagnose (or not) patients’ emotional concerns, which would impact on the identification of relevant literature and the findings. In addition, this study forms part of a wider project that aims to develop an intervention for UK-based GPs. As such, focus facilitated a nuanced and richer analysis of the UK context and how this relates to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the management of emotional concerns (7). We decided to limit articles to those published after 1990 because we felt that these articles would be most relevant to current UK primary care. For example, the 1990 care act shifted the care and support of people with mental health problems into community settings (8), and the first NICE guidelines for the management of mental health problems were published in the early 2000s (7).

Information sources and search strategy

Electronic searches: the following databases were searched from 1990 to February 2017 and updated in November 2018, with the search syntax being modified appropriately for each database: MEDLINE, PsycInfo and EMBASE. These databases were selected for broad consideration of health services research.

Search strategy: we developed a comprehensive search strategy through consultation with the University of Exeter’s evidence synthesis team. We also scoped relevant literature to identify search terminology. The search strategy used a combination of free-text terms, organized into three categories: communication, primary care and emotional concerns in order to address the key aims of the research question. Database specific controlled vocabulary (medical subject headings, MeSH) was used to ensure as many sources as possible were identified. The search strategy can be found in Supplementary Material 1.

Additional sources: the database search was supplemented by backwards and forwards citation chasing of included studies.

Study selection

Data management: all references were managed in Mendeley V1.18. Titles and abstracts identified in the database search were imported into Mendeley and duplicates removed.

Screening: titles and abstracts were screened independently against the inclusion criteria by DP. Full texts of selected papers were retained for inspection by DP. The first 1000 titles and abstracts were checked by two researchers independently (DP and DK) to identity and resolve any idiosyncrasies in the operationalization of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. An inter-rater agreement rate of 93% was achieved and disagreements were resolved via email.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by DP. Two bespoke data extraction sheets were developed in Microsoft Excel and piloted with three papers. The first was used to extract an overview of each study and extracted data on study design, participants, results and conclusions. The second was used for extracting detailed information from the results section of each paper. Both sheets can be found in Supplementary Materials 2 and 3.

Quality assessment

All studies were assessed for quality and rigour using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) research appraisal tool (9). This resource was selected as it is flexible enough to assess a range of study designs, both qualitative and quantitative, and was, therefore, suitable for the breadth of designs included in this review. Quality assessment of included studies was conducted by DP.

Data synthesis

Synthesis of included papers followed a thematic analysis approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (10). Included papers were read and re-read for familiarization. The findings/results of each of the papers were examined and findings relevant to the research question were coded. This enabled the development of an initial bank of codes. These codes were grouped by DP and RM based on similarities across codes into categories. The categories were discussed in a series of meetings between RM and DP to develop consensus. Finally, categories were examined iteratively using a constant comparative process to move from descriptive categories to conceptual themes. Maps and diagrams were used to interrogate relationships between themes. Development of themes was discussed between DP, RM and RB throughout to ensure reliability and validity of the analysis.

Results

Studies

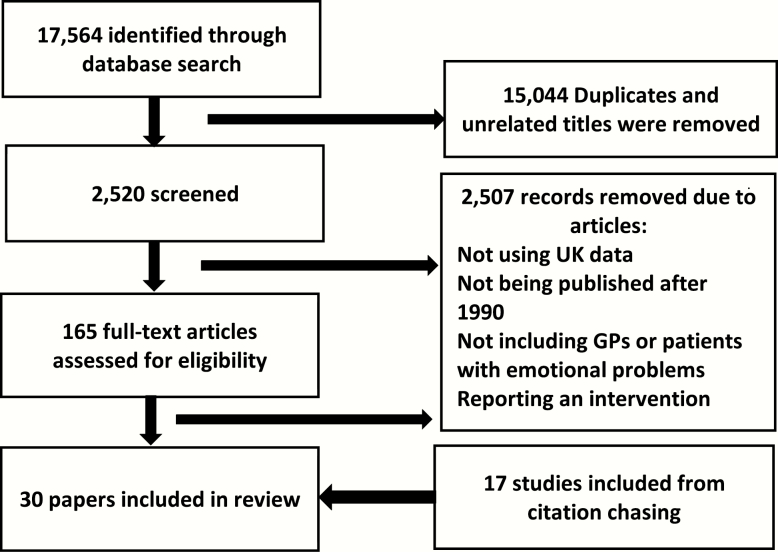

A total of 17 564 studies were retrieved and, of these, 30 papers were included for review. A full report of the study selection process can be found in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the selection process of studies for qualitative synthesis.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows a summary of the 30 included studies in the qualitative synthesis. The majority (n = 19) of included papers involved qualitative interview or focus group studies. Five papers presented qualitative analyses of consultation recordings. Four papers used quantitative methods to analyse interviews and consultation recordings. Two papers were reviews.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 30 studies published between 1990 and 2018 included in qualitative synthesis

| Paper | Sample size | Method | Objective | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews | ||||

| Thompson and McCabe (37) | 20 papers | Systematic review | To identify whether an association exists between clinician–patient alliance or communication and treatment adherence in mental health care | Clinician–patient alliance is associated with improved adherence. |

| Ford et al. (19) | 323 GPs | Metasynthesis | To synthesize the available information from qualitative studies on GPs’ attitudes, recognition and management of perinatal anxiety and depression | GPs use strategies to mitigate the lack of timely access to psychological therapy. GPs are reluctant to medicalize distress and rely on clinical judgement more than guidelines. |

| Qualitative interviews/focus groups | ||||

| Pollock (16) | 32 patients | Qualitative interviews | To discuss patient accounts of maintaining face and the effort to conceal depression | Face work used to maintain successful social interaction bleeds into the medical domain and can make it challenging for patients to disclose distress. |

| Buszewicz et al. (34) | 12 GPs, 20 patients | Interviews with tape-assisted recall | To identify which aspects of GP consultations patients presenting with psychological problems experience as helpful or unhelpful | GP consultations can be beneficial for patients with psychological problems, particularly, as GPs providing a safe space where patients feel listened to and understood. |

| Cape et al. (38) | 11 GPs, 14 patients | GP and patient interviews with tape-assisted recall | To explore how patients’ understanding of common mental health problems is developed in GP consultations | GPs can help patients develop an understanding of the problem by focusing and shaping patients’ own understandings. |

| Tavabie and Tavabie (11) | 20 GPs | Analysis of interviews and focus groups | To identify effects of using mental health questionnaires on views of GPs managing depression and how this might influence patient care | Using mental health questionnaires could improve GPs’ confidence; questionnaires were a way to involve patients. |

| Garfield et al. (31) | 51 patients | Qualitative interviews | To identify information needs and the level of involvement in decision-making desired by patients beginning courses of antidepressant medication | Patients want information about adverse drug reactions, process of recovery, dosage and length of treatment but this is often unmet. Patient preferences for involvement in decision-making vary. |

| Gask et al. (12) | 27 patients | Qualitative interviews | To explore depressed patients’ perceptions of the quality of care received from GPs | The depressed person may feel that they do not deserve to take up the doctor’s time or that it is not possible for doctors to listen to them and understand how they feel. |

| Johnston et al. (24) | 61 patients, 32 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To identify issues of importance to GPs, patients and patients’ supporters regarding depression management | GPs and patients find it hard to separate depression from life circumstances, but GPs may encourage a biological approach to relieve stigma. Patient’s goals were varied and influenced by perceptions of cause, controllability and duration. GPs give patients time to talk and emphasize an individual approach and listening. |

| Malpass et al. (30) | 9 GPs and 10 patients | Qualitative interviews | To explore what important issues remain unsaid during a primary care consultation for depression, patients’ reasons for non-disclosure and the nature of the GP–patient relationship in which unvoiced agendas occur | Unvoiced agendas may be patients’ attempts to protect their GP. Patients may withhold treatment preferences if they perceived lack of patient-centred communication. Patients would drop clues about their preferences. |

| Chew-Graham et al. (22) | 19 GPs, 14 health visitors | Qualitative interviews | To explore the views of GPs and health visitors on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression | Ongoing organizational changes within primary care, such as the implementation of corporate working by health visitors, affect care provided to women after birth, which, in turn, has an impact on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression. |

| Chew-Graham et al. (18) | 19 GPs, 14 health visitors, 28 women | Qualitative interviews | To explore GPs’, health visitors’ and women’s views on the disclosure of symptoms which may indicate postnatal depression in primary care | Both women and heath care professionals (HCPs) describe depression in psychosocial terms, women make a conscious decision about disclosure and HCPs hinder disclosure and are reluctant to make a diagnosis due to lack of personal resources and services. |

| Chew-Graham et al. (26) | 35 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To explore GP attitudes to the management of patients with depression and compare the attitudes of patients in more and less socio-economically deprived areas | GPs feel the need to separate normal reactions to life stressors and true illness. For patients living in deprived areas, these problems may seem insoluble. |

| Pollock and Grime (35) | 32 patients | Qualitative interviews | To investigate patients’ perceptions of entitlement to time in general practice consultations for depression | Patients feel intense time pressure and use self-rationing, which affects patient’s ability to open up. Patients value time to talk. There is a mismatch between patients’ own sense of time entitlement and the doctors’ capacity to respond flexibly. |

| Pollock and Grime (32) | 19 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To investigate GP perspectives on consultation time and the management of depression in general practice | GPs generally did not experience time to be a limiting factor in providing care for patients with depression. This is in contrast to the more acute sense of time pressure commonly reported by patients, which they felt undermined their capacity to benefit from the consultation. |

| Rogers et al. (14) | 27 Patients, 10 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To explore the ways that doctors and patients conceptualize and respond to depression as a problem in the specific organizational context of primary care. | The perceived nature of primary care provision and the legitimacy of their problem influenced patient expectations. Dealing with depression constitutes work that is shaped and constrained by both individual preference and wider medical knowledge, resources and professional interactions. |

| Kadam et al. (13) | 27 Patients | Qualitative interviews and focus groups | To explore patient perspectives in relation to their health care needs in anxiety and depression | Patients describe personal and professional barriers to seeking help and have particular views on the treatment options. This perspective contrasts with the current professional emphasis on detection and medication use. |

| Maxwell (25) | 37 Women, 20 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To explore women’s and GPs’ experiences of recognizing depression and their experiences of the management of depression | The acceptance of antidepressants created a moral dilemma for the women. For GPs, the diagnosis and management of depression led to contemplating the boundaries of their professional role, and social and moral reasoning was also evident in their decision-making processes. |

| McPherson and Armstrong (27) | 20 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To examine how GPs would construct ‘depression’ when asked to talk about those anomalous patients for whom the medical frontline treatment did not appear to be effective | GPs responded in non-medical ways, including feeling unsympathetic, breaking confidentiality and prescribing social interventions. |

| Murray et al. (20) | 18 GPs, 7 practice nurses, 5 practice counsellors | Qualitative interviews | To understand the attitudes that underlie interaction between clinicians and older patients with depression | Older people rarely report psychological difficulties, especially men; GPs worried about medicalizing normal ageing; stigma is a barrier to seeking help. |

| Railton et al. (17) | 15 GPs | Qualitative interviews | To explore the experience of GPs about how they approached the care of patients with depression in relation to their skills, knowledge and attitudes | GPs experience a lack of time, valued continuity of care and resisted the categorization imposed by guidelines; some GPs use talking therapy; caring for depressed patients is emotionally draining for GPs; GPs rely on intuition; GPs acknowledge the critical role of stigma. |

| Qualitative analysis of consultation recordings | ||||

| McPherson et al. (29) | 12 consultations | Analysis of audio-recorded consultations | To investigate ways in which difficult interactions may arise from the medical context, which imposes constraints on the number and nature of problems a patient may present in a single consultation | The context (structure and format) of the GP consultation restricts GPs when supporting these patients. Working with patients to construct biopsychosocial model and circumvent the traditional consultation structure. |

| Miller (39) | 3 GP consultations | Conversation analysis of recorded consultations | To investigate GP’s communication when asking about suicidal ideation pre-diagnosis of depression | It is important to fit questions about suicidality into the interactional sequence. This can be done by prefacing the question with a summary of the patients’ concern. |

| Karasz et al. (23) | 30 transcripts | Secondary analysis of consultation data | To explore how interaction patterns common to most doctor–patient conversations shaped physician decision outcomes in the management of distress | Patients’ preferences and conceptual models affect what treatment GPs recommend. |

| Millar and Goldberg (21) | 19 general practice vocational trainees | Analysis of taped consultations | To investigate possible relationships between the ability to detect emotional disorder and the ability to give information, advice and management to the patient | Able identifiers of mental illness were more likely to offer patients information and advice about their treatment, possibly reflecting greater confidence and superior patient-centred communication style. |

| McPherson and Armstrong (27) | 12 patients, 12 GPs | Analysis of audio-recorded consultations | To explore how patients with treatment-resistant depression and GPs co-construct difficult consultations | Presentation of multiple problems in multiple domains clash with the consultation format. The question and answer format restricts multifaceted discussions of social and emotional problems. |

| Quantitative | ||||

| Cape (63) | 57 Patients | Statistical analysis of coded interview and questionnaire data | To explore the association between therapeutic relationship and clinical outcome in GP treatment of emotional problems | Results indicate a correlation between patients’ perceived quality of relationship with their GP and reduction in symptom severity 3 months later. |

| Cape (28) | 88 patients, 9 GPs | Statistical analysis of coded consultation, interview and questionnaire data | To investigate the extent to which psychological treatment of emotional problems is undertaken by interested doctors in routine general practice and to explore what aspects of GPs’ psychological treatment might be therapeutic | Less than half the average consultation was found to comprise psychological treatment. Although psychological treatment generally was associated with positive patient experiences, the strongest effects found were for listening interactions and for rated doctor empathy |

| Cape and McCulloch (15) | 64 patients 9 GPs | Statistical analysis of coded interview, consultation, and questionnaire data | To investigate patients’ (with high General Health Questionnaire scores) self-reported reasons for not disclosing psychological problems in consultations with GPs | Most common reason for non-disclosure is the perception that GP doesn’t have enough time and that there is nothing the doctor can do. |

| Cape and Stiles (36) | 88 patients, 9 GPs | Statistical analysis of coded consultation, interview and questionnaire data | To examine the interrelations of speech act, content and evaluative measures | Patient-centred exchanges called Social Exposition and Emotional Exposition, which may serve psychotherapeutic purposes, were relatively prominent in those consultations rated relatively positively by patients and by external raters. |

Study participants: a total of 342 GPs and 720 patients participated in the included studies. Patients in the studies included patients experiencing depression, anxiety, postnatal depression, perinatal depression and anxiety, as well as, more generally, ‘psychiatric disorders’, ‘psychological problems’, ‘psychological distress’, ‘emotional problems’ and ‘mental health problems’.

Settings: all studies focused on UK primary care.

Quality assessment: out of a maximum score of 10, 1 paper scored 6, 8 scored 7, 15 scored 8 and 6 scored nine. No studies were excluded on quality grounds. All but one of the studies had clear research questions (4) and reported appropriate recruitment (11). All collected data in a way that addressed the research question. However, in most of the studies, it was unclear whether the relationship between researcher and participant had been adequately considered, and ethical issues were often underreported. Further details of the critical appraisal can be found in Supplementary material 4.

Findings

Details of the themes can be found in Table 2. Further details on how the themes relate to the findings from each study can be found in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Themes identified from qualitative synthesis of 30 studies published between 1990 and 2018

| Research question | Themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Barriers | Emotional problems resist disclosure |

| Tension between medical and social explanatory models | |

| Unspoken assumptions about agency | |

| Stretched resources vs. optimum care | |

| 2. Facilitators | Human connection is healing |

| Exploring, explaining and negotiating understanding | |

| Information provision facilitating involvement |

Table 3.

Themes pertaining to barriers drawn from studies published between 1990 and 2018

| Ford et al. (19) | Cape and McCulloch (15) | Pollock (16) | Tavabie and Tavabie (11) | Garfield et al. (31) | Gask et al. (12) | Johnston et al. (24) | Malpass et al. (30) | Chew-Graham et al. (22) | Chew-Graham et al. (26) | Pollock and Grime (32) | Rogers et al. (14) | Kadam et al. (13) | Maxwell (25) | McPherson and Armstrong (27) | Murray et al. (20) | Railton et al. (17) | McPherson et al. (29) | Karasz et al. (23) | Cape (63) | Cape (28) | Chew-Graham et al. (18) | Goldberg et al. (33) | Number of sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Emotional problems resist disclosure | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 | |||||||||||

| Medical and social explanatory models | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 16 | ||||||||

| Stretched resources vs. optimum care | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Unvoiced assumptions | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

Table 4.

Themes pertaining to facilitators drawn from studies published between 1990 and 2018

| Thompson and McCabe (37) | Ford et al. (19) | Cape and McCulloch (15) | Buszewicz et al. (34) | Cape et al. (38) | Tavabie and Tavabie (11) | Garfield et al. (31) | Gask et al. (12) | Johnston et al. (24) | Pollock and Grime (35) | Rogers et al. (14) | Kadam et al. (13) | Maxwell (25) | McPherson abd Armstrong (27) | Railton et al. (17) | Miller (39) | Karasz et al. (23) | Millar and Golberg (21) | Cape and Stiles (36) | Cape (63) | Cape (28) | Chew-Graham et al. (18) | Goldberg et al. (33) | Number of sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Human connection | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 | ||

| Exploring, explaining and negotiating understanding | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 | |||||||||||||

| Information provision facilitating involvement | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

BarriersEmotional concerns are difficult to disclose

Patients experienced a number of barriers to disclosing their concerns in primary care consultations. Symptoms such as low self-worth, pessimism about the future and guilt about wasting the GP’s time caused patients to minimize their concerns (12,13). Patients often did not understand what they were experiencing and, thus, were worried about their ability to be understood by their GP (14–16).

Both GPs and patients experienced the effect that stigma had on hindering disclosure and identification of emotional concerns. Patients experienced shame about not feeling able to cope, and this prevented disclosure (14,15). GPs also reported patient’s feelings of stigma as preventing the detection of emotional concerns (17) as they believed that the patient would resist diagnosis (18–20). GP confidence also prevented diagnosis. Less confident or experienced GPs may be less able to detect, or actively avoid eliciting, emotional concerns (11,21).

Tension between medical and social explanatory models

Both GPs and patients reported tensions between understanding emotional concerns as a medical condition or resulting from social stressors. GPs were reluctant to ‘medicalize’ patients’ concerns, differentiating between ‘real depression’ and normal sadness caused by an understandable response to difficult life circumstances (14,18–20,22–27). GPs also resisted the categorization imposed by guidelines (17), and more experienced GPs preferred to use clinical intuition over intrusive screening questions (11,17–19,22).

Patients also reported concerns about the legitimacy of emotional concerns as a medical issue (14,15), often presenting with both physical and emotional concerns (28). Patients understood their emotional concerns as individual and multifactorial, with life, self and illness inextricably linked (14,18,22,24). Varying explanatory models influenced patients’ treatment preferences. Patients who considered their concerns to be linked to difficult life circumstances emphasized self-management (14), whereas patients who considered their emotional concerns as something to be ‘cured’ preferred a diagnostic approach (24). This tension between medical and social explanatory models also affected how much patients believed their GP could help them. Many patients were pessimistic about the utility of seeking help from their GP and believed that GPs do not have sufficient knowledge or skill (14–16) and that GPs would only provide antidepressants (13).

Unspoken assumptions about agency

There was a lack of open discussion between GPs and patients about patients’ preferences for control over their care, and this lead to a mismatch in understandings, priorities or agendas (29). In particular, GPs often assumed that patients sought more control over their care than the patient actually wanted or was able to have (30). Patients reported feeling unable to make treatment suggestions because they saw their GP as the expert, which prevented shared decision-making (30). Indecision associated with experiencing emotional concerns also made it difficult for patients to share treatment preferences (11,12,30). Patients’ preferences for involvement were dynamic and evolved throughout the course of treatment, with patients often becoming more involved as their symptoms improved (31). GPs also reported frustration with patients, in particular, patients who seem to resist or otherwise not act how GPs believe patients should, for example, by taking more authority in the consultation (24,26,29).

Stretched resources vs. optimal care

GPs described feeling that they needed to balance timekeeping with giving patients effective support (17,26). Lack of time was described as a barrier to identification, disclosure and listening to patients (14,15,17,19,24,32). Having more time to listen to patients would reduce the need for GPs to prescribe antidepressants (32). However, Pollock (32) found that GPs believed that it was possible to give patients effective support in the time afforded in general practice, in particular, in cases of mild depression where GPs main role was to support patients with better coping skills (32).

Another challenge for GPs was the lack of psychological services available. GPs often preferred counselling as a treatment option; however, this was often unavailable. This made GPs reluctant to diagnose emotional concerns (18) or forced them to prescribe antidepressants (14,26). Antidepressants had the benefit of being readily available to GPs (32) but GPs asserted that they might manage emotional concerns differently if they were not under such constraints (14). Exacerbated by these pressures, providing care for patients with emotional concerns is often emotionally draining for GPs (26).

FacilitatorsA human connection is healing

Patients reported valuing a human connection with their GP. Empathy and a warm approach was particularly important (12,24), being positively associated with the identification of distress and patients communicating more psychological clues (33). This ‘human touch’ helped patients to talk about their concerns (34) and was intrinsically therapeutic, being related to a reduction in patients’ symptoms 3 months later (4).

Having time to talk and being listened to was very important (12,34). Being able to get things off their mind was a release for patients and was intrinsically therapeutic (13,14,24,31,35). Consultations with more listening were rated positively (28), helped patients to open up (34), were associated with more GP warmth and empathy (17,24,36) and served a normalizing and reassuring function (17,24). GPs also believed that listening supported the doctor–patient relationship, built trust and was sometimes the only thing the GP could do (17,24,25,27).

Non-verbal displays of attentiveness, such as eye contact, an attentive posture, faciliatory noises and not interrupting, were all associated with increased identification of emotional concerns (33). This attentive listening helped patients to open up and helped GPs to pick up on patient’s clues about emotional concerns (34). If patients perceived their GP to not be interested, then they were less likely to disclose emotional concerns (15)

An ongoing, continuous relationship with a GP facilitated patient disclosure (18) and GP identification (11,17) of emotional concerns, generated trust (11) and improved adherence to treatment recommendations (37). GPs could support this continuous relationship and create a helpful safe space for patients to return to (34) by asking patients to come back to them (18,19). GPs could also support patient’s actions that they have already taken or progress they are making, which made patients feel validated and encouraged (34).

Exploring, explaining and negotiating understanding

There was considerable emphasis in the included studies on negotiating the nature of the concern to reach a shared understanding. This was different to the more conventional ‘diagnostic moment’ in biomedical consultations where the diagnosis is delivered by the GP. Shared understanding was supported by open psychological questioning (24,28). GPs could support patients to develop their own understanding, and this joint process was valued by patients (34). Simply allowing patients to talk and asking questions, such as ‘how does it affect you’, helped patients to reflect on and clarify their experiences (24,38). However, encouraging patient reflection was not sufficient for all patients (38). In these cases, GPs could take a more active approach by focusing, shaping and refining patients’ accounts, in particular, by highlighting and reflecting back parts of the patient’s accounts that the GP believed were useful to highlight, which developed patients’ understanding of their emotional concerns (38).

Once GPs had explored patients’ understandings, it was useful for GPs to create an understanding based on joint GP–patient expertise by providing explanations (38). Explaining the mechanisms of emotional concerns had a normalizing function, helping patients feel like they were not ‘going mad’ (34). In addition, biological explanations attenuated the effects of stigma, separating the illness from the patient and giving the patient ‘something to sort out’ (17,18,34). However, it was important that the explanations GPs provided fit patients’ own explanatory models (34,38).

Shared understanding could be supported by using questionnaires, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Questionnaires could help less experienced GPs distinguish stress from depression, define severity and take an objective view of patients’ symptoms (11). GPs also needed to determine the severity of risk, in particular, assessing suicidal ideation. Effective questioning about suicidal ideation demonstrated the sensitivity of the topic and provided space for patients to admit suicidality. This could be done by asking the question in such a way that expects a ‘yes’ response (39).

Understanding patients’ explanatory models of their concerns was a prerequisite for designing the treatment recommendation in a way that was more likely to be endorsed by patients. If patients did not feel understood, the advice was more likely to be rejected (34). GPs believed that taking time to establish this understanding is associated with a more effective response to treatment (32).

Information provision facilitating involvement

Involving patients in treatment decisions was empowering for patients, improved adherence (19) and ameliorated symptoms (4). However, it may have been that patients with less severe symptoms were more able to be involved in their care (31). As patients’ preferences for involvement were variable, identifying preferences and tailoring involvement accordingly was recommended (19).

Providing information about treatment allowed patients to be involved in treatment decisions. In particular, patients wanted realistic information regarding the side effects of medication, the course of recovery, the dosage prescribed and treatment length (27,31). Patients reported that they would feel more prepared for the slow improvement and fluctuating symptoms experienced during treatment if this was discussed with them at the outset (27,31). Patients also reported fears about addiction to antidepressants, which GPs could alleviate by drawing up a withdrawal strategy with the patient. This made the patient more willing to take antidepressants (25,31). Offers of medication were also more likely to be accepted when made directly (as opposed to in vague terms) (23,28), and attempting to persuade the patient was always unsuccessful (23).

Discussion

Summary

Identifying emotional concerns, stigma and the curative role of the therapeutic relationship remain relevant. Symptoms, tensions between GP–patient understandings of medical concerns and social stressors and lack of time and resources impede effective communication. GPs and patients consider emotional concerns within the context of patients’ lives and, therefore, exploration and negotiation of a shared understanding is valued. Unspoken assumptions about patients’ preferences for involvement in decision-making can lead to a mismatch between the level of control the GP expects the patient to take and what patient feels able to take.

Strengths and limitations

The search strategy was comprehensive and developed alongside evidence synthesis experts from the University of Exeter’s evidence synthesis team to ensure the search was systematic and wide. Searches were supplemented by backwards and forwards citation chasing to identify any additional relevant material. Sources were screened by one reviewer, and a sample of 1000 titles and abstracts were reviewed by a second reviewer, achieving a high inter-rater agreement of 93%, demonstrating the reliability of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Included studies were discussed throughout by DP, DK and RM to resolve discrepancies in agreement regarding inclusion. While it is always a concern that relevant studies will have been missed when conducting a systematic search, there was a large degree of overlap when synthesizing the results of included studies suggesting that the inclusion of additional studies would have been unlikely to change the results.

Studies were synthesized following robust and commonly used steps for thematic analysis (10). This review has been reported in accordance with the criteria in the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews (40) (Supplementary Material 5) and all included studies were of high-to-moderate quality. This review was original in its aim to synthesize the available evidence on how GPs and patients communicate about emotional concerns. While there is a significant amount of literature in this area, GP–patient communication about emotional concerns remains a challenge and, therefore, synthesizing the available evidence in this area is a step towards understanding the barriers faced by GPs.

A limitation of this review is that the original data across the mostly qualitative studies was not analysed as this was not feasible in a systematic review. Hence, this study relies on the quality of analysis of the original studies. This also means that some of the detail of the primary data is inevitably lost. However, all of the included studies scored highly on analytical rigour, and this review follows a transparent approach to analysis, which allows for more confident interpretation of the data.

Comparison with existing literature

The findings from this review are reflected by studies from outside the UK. First, patients in New Zealand and India are reluctant to disclose emotional concerns, often presenting with physical concerns, leaving little time to explore emotional concerns (41,42). Stigma is also a barrier; self-stigma and perceived stigma prevent patients from seeking help from their GP in Australian primary care (43). The challenges of these consultations are felt by GPs outside the UK, with rates of emotional exhaustion being high in GPs from Scandinavia to Kuwait (44–46).

The role of the GP–patient relationship in supporting care for emotional concerns was a common finding in the papers in this review. This reflects the large amount of literature that highlights the importance of the therapeutic relationship in care for patients with other medical conditions (47) and in secondary care (48). Additionally, GPs in this study reported providing explanations to patients and highlighted that biological explanations may reduce the patient’s self-stigma. Practitioners in primary care in the USA may also provide patients with a biological explanation for their emotional concerns to attenuate the effects of stigma (49).

Implications for research and practice

This review highlights a number of implications for improving GP practice. While negative public perceptions regarding mental illness are abating (50), in part, due to recent campaigns in the UK such as ‘Time to Talk’, 9 out of 10 individuals with a mental illness report experiencing stigma or discrimination (51). The ongoing culture of stigma, and the lack of parity of esteem of psychosocial issues compared with biomedical issues, makes it difficult for patients to openly discuss emotional concerns with their GP. Therefore, patients often attempt to disclose using clues and hints, such as expressions of frustration (52). GPs can explore patients’ clues to create an environment where the discussion of emotional concerns is legitimized, supporting the identification and subsequent support of emotional concerns (52). Exploring patients’ emotional clues by using prompts and exploratory questions, such as ‘how does that make you feel?’ (53), supports the development of a shared understanding, which is associated with improved clinician–patient alliance and adherence (54).

Adherence can also be improved by providing information about treatment. Specifically, when GPs tell patients how long they will have to take antidepressant medication, discussing side effects and how to manage them and addressing patients’ concerns, patients are three times more likely to adhere to medication after 3 months (55–58). Providing information is one way to improve patient involvement in their care, which is associated with significant symptom improvement at 6 months (59).

This review also has implications for future research. In particular, this review highlights issues regarding unspoken assumptions about agency. A lack of open communication regarding preferences for involvement in care can lead to a mutual misunderstanding and a breakdown in decision-making (12,30). This finding is relatively underrepresented in the literature, yet has implications for research regarding unmet concerns (30), as well as current models of patient-centred care, which may encourage patients to be given more agency than they desire. Future research should consider this mismatch further to develop understanding of how it is maintained and strategies for facilitating more open communication.

Another implication for research is developing further understanding of how the GP–patient relationship can be operationalized in practice. There is considerable evidence indicating the importance of this relationship; however, it is less clear what comprises this in practice. Possible components include conveying hope, optimism and empathy, which are associated with improved patient outcomes (60–62). Future research could consider how GP–patient communication can be optimized to develop a therapeutic relationship.

Conclusion

Previous research has found that psychological management by GPs is effective but poorly defined (6). This review built on this by synthesizing evidence on barriers to and facilitators to effective GP–patient communication from GP and patient perspectives within UK primary care. The findings suggest that treatment guidelines should acknowledge: the therapeutic value of a positive GP–patient relationship; that diagnosis is a two-way negotiated process rather than an activity strictly in the doctor’s domain of expertise; and the value of exploring and shaping new understandings about patients’ emotional concerns and their management.

Declarations

Funding: the Judi Meadows Memorial Fund, a protected fund of the McPin Foundation, and the University of Exeter Medical School jointly funded this study. RB is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula (NIHR CLAHRC South West Peninsula). The view expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Judi Meadows Memorial Foundation, the McPin Foundation, the University of Exeter Medical School, the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval: ethical approval was not required for this study.

Conflict of interest: there are no competing interests to report.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Judi Meadows Memorial Foundation, the McPin Foundation, and University of Exeter Medical School for funding this research. Thank you to the Data Bee for their support with the qualitative analysis. Thank you to the University of Exeter Evidence Synthesis Team for their ongoing advice and support throughout this review.

References

- 1. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T.. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldberg DP, Huxley P.. Common Mental Disorders: A Bio-Social Model. New York, NY: Tavistock/Routledge, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cape J, Barker C, Buszewicz M, Pistrang N. General practitioner psychological management of common emotional problems (II): a research agenda for the development of evidence-based practice. Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50: 396–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2009; 47: 826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cape J, Barker C, Buszewicz M, Pistrang N. General practitioner psychological management of common emotional problems (I): definitions and literature review. Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50: 313–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Mental health and the NHS What’s changed and what’s to come? http://indepth.nice.org.uk/mental-health-and-the-nhs/index.html. Published 2018 (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- 8. Department of Health. National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990 (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- 9. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme UK. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. CASP Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense of Evidence. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 11 August 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tavabie JA, Tavabie OD. Improving care in depression: qualitative study investigating the effects of using a mental health questionnaire. Qual Prim Care 2009; 17: 251–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gask L, Rogers A, Oliver D, May C, Roland M. Qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of the quality of care for depression in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53: 278–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadam UT, Croft P, McLeod J, Hutchinson M. A qualitative study of patients’ views on anxiety and depression. Br J Gen Pract 2001; 51: 375–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rogers A, May C, Oliver D. Experiencing depression, experiencing the depressed: the separate worlds of patients and doctors. J Ment Health 2001; 10(3):317–33. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cape J, McCulloch Y. Patients’ reasons for not presenting emotional problems in general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract 1999; 49: 875–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pollock K. Maintaining face in the presentation of depression: constraining the therapeutic potential of the consultation. Health (London) 2007; 11: 163–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Railton S, Mowat H, Bain J. Optimizing the care of patients with depression in primary care: the views of general practitioners. Health Soc Care Community 2000; 8: 119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chew-Graham CA, Sharp D, Chamberlain E, Folkes L, Turner KM. Disclosure of symptoms of postnatal depression, the perspectives of health professionals and women: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2009; 10: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ford E, Lee S, Shakespeare J, Ayers S. Diagnosis and management of perinatal depression and anxiety in general practice: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract 2017; 67: e538–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murray J, Banerjee S, Byng R et al. Primary care professionals’ perceptions of depression in older people: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Millar T, Goldberg DP. Link between the ability to detect and manage emotional disorders: a study of general practitioner trainees. Br J Gen Pract 1991; 41: 357–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chew-Graham C, Chamberlain E, Turner K et al. GPs’ and health visitors’ views on the diagnosis and management of postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58: 169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karasz A, Dowrick C, Byng R et al. What we talk about when we talk about depression: doctor-patient conversations and treatment decision outcomes. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62: e55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnston O, Kumar S, Kendall K et al. Qualitative study of depression management in primary care: GP and patient goals, and the value of listening. Br J Gen Pract 2007; 57: 872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maxwell M. Women’s and doctors’ accounts of their experiences of depression in primary care: the influence of social and moral reasoning on patients’ and doctors’ decisions. Chronic Illn 2005; 1: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chew-Graham CA, Mullin S, May CR, Hedley S, Cole H. Managing depression in primary care: another example of the inverse care law? Fam Pract 2002; 19: 632–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McPherson S, Armstrong D. Negotiating ‘depression’ in primary care: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2009; 69: 1137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cape JD. Psychological treatment of emotional problems by general practitioners. Br J Med Psychol 1996; 69(Pt 2):85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McPherson S, Byng R, Oxley D. Treatment resistant depression in primary care: co-constructing difficult encounters. Health (London) 2014; 18: 261–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malpass A, Kessler D, Sharp D, Shaw A. ‘I didn’t want her to panic’: unvoiced patient agendas in primary care consultations when consulting about antidepressants. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garfield S, Francis SA, Smith FJ. Building concordant relationships with patients starting antidepressant medication. Patient Educ Couns 2004; 55: 241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pollock K, Grime J. GPs’ perspectives on managing time in consultations with patients suffering from depression: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2003; 20: 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldberg DP, Jenkins L, Millar T, Faragher EB. The ability of trainee general practitioners to identify psychological distress among their patients. Psychol Med 1993; 23: 185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buszewicz M, Pistrang N, Barker C, Cape J, Martin J. Patients’ experiences of GP consultations for psychological problems: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2006; 56: 496–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pollock K, Grime J. Patients’ perceptions of entitlement to time in general practice consultations for depression: qualitative study. BMJ 2002; 325: 687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cape JD, Stiles WB. Verbal exchange structure of general practice consultations with patients presenting psychological problems. J Health Psychol 1998; 3: 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cape J, Geyer C, Barker C et al. Facilitating understanding of mental health problems in GP consultations: a qualitative study using taped-assisted recall. Br J Gen Pract 2010; 60: 837–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller PK. Depression, sense and sensitivity: on pre-diagnostic questioning about self-harm and suicidal inclination in the primary care consultation. Commun Med 2013; 10: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dew K, Dowell A, McLeod D, Collings S, Bushnell J. ‘This glorious twilight zone of uncertainty’: mental health consultations in general practice in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 1189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Andrew G, Cohen A, Salgaonkar S, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression and anxiety in primary care: a qualitative study from India. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006; 40: 51–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torppa MA, Kuikka L, Nevalainen M, Pitkälä KH. Emotionally exhausting factors in general practitioners’ work. Scand J Prim Health Care 2015; 33: 178–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Osborne D, Croucher R. Levels of burnout in general dental practitioners in the south-east of England. Br Dent J 1994; 177: 372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Al-Shoraian GMJ, Hussain N, Alajmi MF, Kamel MI, El-Shazly MK. Burnout among family and general practitioners. Alexandria J Med 2011; 47(4):359–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2011.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2014; 9: e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Priebe S, Mccabe R. Therapeutic relationships in psychiatry: the basis of therapy or therapy in itself? Int Rev Psychiatry 2008; 20: 521–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Apesoa-Varano EC, Hinton L, Barker JC, Unützer J. Clinician approaches and strategies for engaging older men in depression care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18: 586–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Time to Change. Attitudes to Mental Illness 2014 Research Report. London, UK: TNS BMRB, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Time to Change. Stigma Shout: Service User and Carer Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination. London, UK: Time to Change, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tarber C, Frostholm L. Disclosure of mental health problems in general practice: the gradual emergence of latent topics and resources for achieving their consideration. Commun Med 2014; 11: 189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA 1997; 277: 678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thompson L, Howes C, McCabe R. Effect of questions used by psychiatrists on therapeutic alliance and adherence. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 209: 40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM et al. How can you improve antidepressant adherence? J Fam Pract 2007; 56: 356–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW et al. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med 2004; 2: 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM et al. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA 2002; 288: 1403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care 1995; 33: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV et al. Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care 2006; 44: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Malt UF, Robak OH, Madsbu HP, Bakke O, Loeb M. The Norwegian naturalistic treatment study of depression in general practice (NORDEP)-I: randomised double blind study. BMJ 1999; 318: 1180–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2013; 63: e76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kaplan JE, Keeley RD, Engel M, Emsermann C, Brody D. Aspects of patient and clinician language predict adherence to antidepressant medication. J Am Board Fam Med 2013; 26: 409–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cape J. Patient-rated therapeutic relationship and outcome in general practitioner treatment of psychological problems. Br J Clin Psychol 2000; 39: 383–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.